The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has placed substantial stress on the health care delivery system and exposed strengths and weaknesses that may have been previously underappreciated. A serious issue that emerged was the vulnerability of our medication supply chain, and potential ways to boost or preserve the supply of important medications have been reported.1 The existing health system infrastructure is critical to these efforts and can be used to help steward these vital resources and manage increasing demands. In this commentary, we highlight how antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) and formulary/pharmacy and therapeutics (F/P&T) committees can help manage the COVID-19 pandemic.

Use of ASPS to Optimize Medication Use

Antimicrobial stewardship programs are charged with improving medical outcomes by providing patients with optimal antimicrobial therapy, emphasizing the five rights of medication administration: right patient, right drug, right time, right dose, and right duration. Successful ASP strategies include antimicrobial use policies and procedures, enforceable medication-use restrictions developed by key clinical experts, prospective antimicrobial audit with feedback to prescribers, engagement and partnership with microbiology laboratories, antimicrobial tracking and reporting, electronic ordering tools, and staff education. Furthermore, engagement of multidisciplinary stakeholders across the institution is a critical component of any successful ASP.

Because antimicrobial stewardship structure and strategies are already in place at most hospitals, they are well suited to be rapidly deployed to assist with the COVID-19 pandemic, and antimicrobial stewardship personnel have been heavily involved in the response. However, the pandemic has required a rapid readjustment of the role and tools of antimicrobial stewardship. In many circumstances, this has translated to a temporary diversion of effort and resources from some of the existing ASP activities to focus on pressing and time-sensitive COVID-19 activities. At the same time, the pandemic has led to increased support for activities related to COVID-19 and to infrastructure, some of which can be used to improve overall medication stewardship.

Antimicrobial stewardship program tools such as rule-based flags in the electronic health records, which are used to identify inappropriate antimicrobial prescribing, can also be used to identify medication overuse that may be directly related to COVID-19 medical care. An example is the rapid development and implementation of a flag to identify patients with negative COVID-19 testing and an active order for a medication, such as hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine, or tocilizumab.2 This new flag in the electronic health record serves multiple different functions. First, it can directly preserve medications being inappropriately prescribed. Second, it can allow for engagement between the antimicrobial stewardship, infectious diseases, and prescribing teams to provide real-time education through academic detailing. This approach has been shown to be effective both for patients, who will not be prescribed drugs they do not need, and for physicians, who will learn to avoid inappropriate prescribing.3 In addition, a rule-based flag system to identify patients who are COVID-19–positive and receiving prescribed medications off-label may help identify patients who may be candidates for clinical trials, which could be the most appropriate and scientifically sound approach to determining the utility of these drugs for COVID-19. This approach may help further the science needed to end the global pandemic.

Role OF F/P&T Committees in the Use of COVID-19 Medications

Although an ASP framework can be adapted to address medication use issues, adaptation must be coordinated with F/P&T committees. These committees are critical for identifying impending medication shortages to maintain adequate medication supplies, guide safe medication use practices, and develop appropriate medication-related policies and mitigation strategies. The F/P&T committees can also work with pharmacies that are part of their health system to encourage appropriate prescribing behaviors, such as limiting dispensing of essential medications to recognized appropriate indications or for shorter durations and introducing limits on refill quantities to counteract drug-hoarding behavior.

The rapid pace of the pandemic has also led to substantial challenges in developing evidence-based criteria for medication use. At this time, a sufficient evidence base is lacking to make critical decisions regarding off-label use of approved medications for COVID-19 and to ensure medications remain available for approved indications where there is clear benefit. For example, patients with systemic lupus erythematosus who depend on hydroxychloroquine will likely be harmed if the medication is not available.4 Across all Mayo Clinic sites, there was an 85% increase in outpatient prescriptions for hydroxychloroquine in March 2020 compared with March 2019, which was more pronounced among non-rheumatology services where the prescription rate increased more than 130%. Anticipating this issue, the F/P&T committees developed prescribing and pharmacy dispensing restrictions for hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19 use and also implemented prescription refill limits for pharmacies that are part of Mayo Clinic. By April 2020, the number of prescriptions of hydroxychloroquine had returned to near before COVID-19 levels. Despite this improvement, loopholes in prescribing guidelines and dispensing restrictions make additional mechanisms to optimize medication use necessary.

Integrating the F/P&T Committees and ASP Framework to Sustain Health Care Through the COVID-19 Crisis

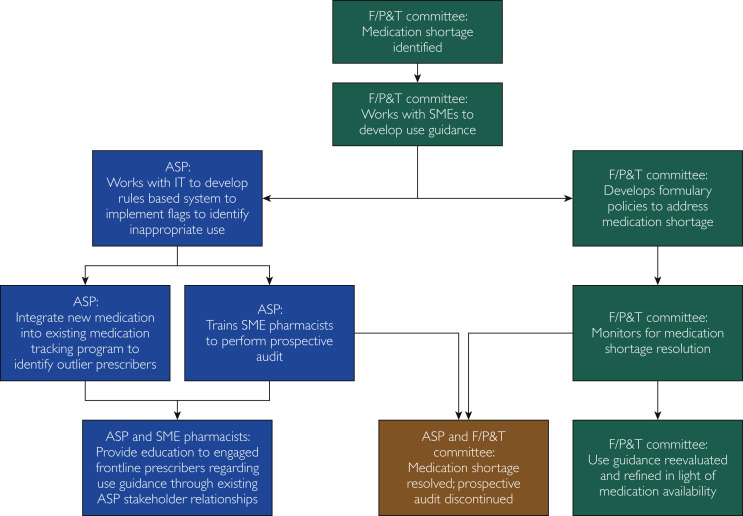

As we enter the plateau phase of this pandemic, we should anticipate a prolonged period of potential disruption of normal medical practice. Accordingly, long-term strategies are necessary to identify and address shortages of medications needed for the care of patients with and without COVID-19. A combined approach is a possibility, using the strength of both the F/P&T committees and the ASP (Figure ) to protect and preserve medications that are already in short supply or have impending supply issues. For example, if an impending hospital shortage of fentanyl were identified by the F/P&T committees, guidelines and potential prescribing restrictions for fentanyl or for alternative medications for critically ill patients could be developed in conjunction with critical care and anesthesia specialists. By using the existing ASP structure and information technology resources, rules could be developed to identify patients for whom fentanyl use is outside of evidence-based guidelines. The care plans for such patients could be reviewed by a medication stewardship pharmacy team, which would ideally include individuals with critical care expertise who could intervene with the primary provider teams to provide recommendations for therapeutic alternatives and education regarding the restriction. Simultaneously, existing programs could be used to monitor drug usage and to identify providers considered prescribing outliers, who could then receive targeted education about the medication identified. Finally, when the F/P&T committees have determined that supply chain interruption has been resolved for a medication, prospective audits and feedback could be discontinued while best practice guidance is updated or maintained as appropriate. Using the existing ASP and F/P&T framework, further rules could be developed to guide appropriate prescribing of other medications in shortage or at risk of shortage, such as dexmedetomidine, propofol, and others currently on the US Food and Drug Administration shortage list.5

Figure.

Flow diagram showing the approach for combining the F/P&T committees and the ASP to protect and preserve medication usage. ASP = antimicrobial stewardship program; F/P&T = formulary/pharmacy and therapeutics committee; IT = information technology; SME = subject matter expert.

Conclusion

Identification and mitigation of medication shortages will be critical to providing high-quality health care to patients, both with and without COVID-19, throughout the pandemic. Whereas national and international strategies to improve drug supply are necessary, local management strategies to identify and steward medications will have a vital role moving forward. Optimal use of existing medication stewardship infrastructure will facilitate timely adaptations in a rapidly evolving health care environment.

Acknowledgment

Editing, proofreading, and reference verification were provided by Scientific Publications, Mayo Clinic.

Footnotes

This supplement is sponsored by Mayo Clinic Foundation for Medical Education and Research and is authored by experts from multiple Departments and Divisions at Mayo Clinic.

Potential Competing Interests: The authors report no potential competing interests.

References

- 1.Choo E.K., Rajkumar S.V. Medication shortages during the COVID-19 crisis: what we must do. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(6):1112–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.04.001. [Epub ahead of print.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stevens R.W., Estes L., Rivera C. Practical implementation of COVID-19 patient flags into an antimicrobial stewardship program's prospective review. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020:1–2. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Solomon D.H., Van Houten L., Glynn R.J. Academic detailing to improve use of broad-spectrum antibiotics at an academic medical center. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(15):1897–1902. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.15.1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canadian Hydroxychloroquine Study Group A randomized study of the effect of withdrawing hydroxychloroquine sulfate in systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(3):150–154. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199101173240303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Food & Drug Administration FDA Drug Shortages. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/drugshortages/