Abstract

DNA repeats capable of adopting stable secondary structures are hotspots for double-strand break (DSB) formation and, hence, for homologous recombination and gross chromosomal rearrangements (GCR) in many prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms, including humans. Here, we provide protocols for studying chromosomal instability triggered by hairpin- and cruciform-forming palindromic sequences in the budding yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. First, we describe two sensitive genetic assays aimed to determine the recombinogenic potential of inverted repeats and their ability to induce GCRs. Then, we detail an approach to monitor chromosomal DSBs by Southern blot hybridization. Finally, we describe how to define the molecular structure of DSBs. We provide, as an example, the analysis of chromosomal fragility at a reporter system containing unstable Alu-inverted repeats. By using these approaches, any DNA sequence motif can be assessed for its breakage potential and ability to drive genome instability.

Keywords: Inverted repeats, Secondary structures, Genome instability, DSB detection, Gross chromosomal rearrangements

1. Introduction

DSBs are harmful DNA lesions that cells experience during each cell cycle. Their detrimental outcomes include a variety of chromosomal rearrangements, mutagenesis, and even cell lethality. DNA can acquire DSBs upon exposure of cells to extracellular damaging agents, during replication fork collapse, and due to activation of programmable, site-specific DNA endonucleases [1]. Importantly, chromosomes, especially in eukaryotes, often carry an intrinsic potential for breakage due to the presence of repeats with an internal symmetry that allows DNA to fold into non-B-form secondary structures or accumulate noncanonical intermediates. Stable hairpins and cruciforms, G4 quadruplexes, triplexes, and R-loops can trigger DSBs and rearrangements because (1) they are targets for structure-specific nucleases and (2) they represent strong barriers for DNA replication [2]. Bioinformatic algorithms designed to identify secondary structure–forming motifs are not always accurate and are only suggestive. Hence, analysis of the potential of particular regions of DNA to be fragile often requires experimental evaluation. Here, we present methods to study the ability of these sequence motifs to induce genetic instability in the chromosomal context by sensitive genetic assays and by direct detection and assessment of the molecular structure of mitotic DSBs. Overall, these methods allow two main questions to be addressed. First, does a particular DNA sequence motif induce recombination and GCRs and to what degree? Second, what is the mechanism of DSB formation? The latter question requires identification of proteins that maintain the stability of the repeats or trigger their fragility. Below, we describe methods to analyze fragility promoted by inverted repeats. We have applied similar approaches to study the instability of GAA/TTC triplet repeats [3, 4]. We believe that any sequence motif suspected to induce breakage and rearrangements can be studied using these methods.

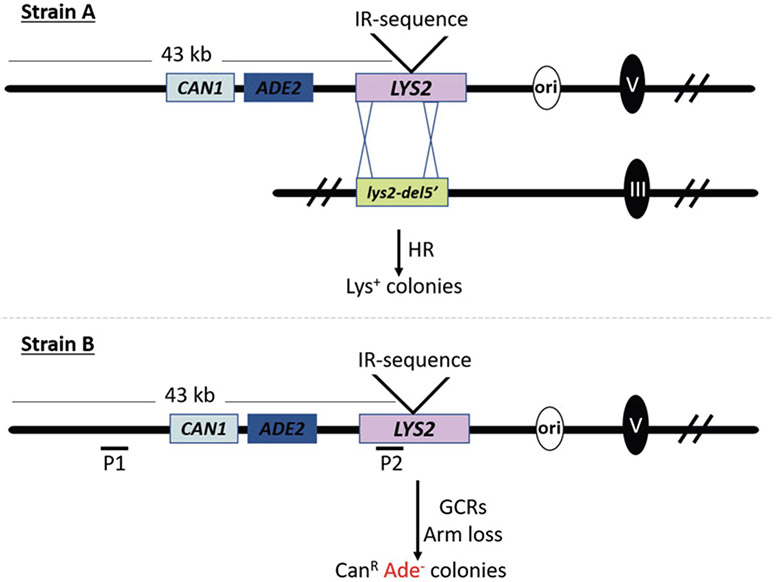

As a rule of thumb, we insert inverted repeats into the counter-selectable marker LΥS2 located on URA3- or TRP1-containing integrative vectors [5]. These vectors allow replacement of chromosomal LΥS2 at the endogenous locus on chromosome II (ChrII) or at LΥS2 relocated to the left arm of chromosome V (ChrV) next to the CAN1 gene (in the GCR assay, Fig. 1) with a lys2∷Alu-IRs allele using the “pop-in, pop-out” technique, selecting Lys−Ura− or Lys−Trp− isolates with a replacement on alpha-aminoadipate-containing medium. In the recombination assay, we integrate a second mutant lys2 allele (e.g., lys2-8 or lys2-del5’) into the LEU2 locus on chromosome III (ChrIII) (Fig. 1, strain A) [3, 6]. The spontaneous rate of interchromosomal ectopic recombination between lys2 alleles that do not contain fragile motifs is ~2 × 10−7 cells/division. Insertion of a 320 bp long Alu quasi-palindrome (Alu-IRs with a 12 bp asymmetrical spacer), Alu-QP, into the LΥS2 gene leads to a nearly 1,000-fold increase in the recombination rate. These inverted repeats were found to induce chromosomal DSBs with a frequency of ~2%. This system was instrumental in identifying hyporecombination mutants deficient in the endonuclease activity of the Mre11/Rad50/Xrs2 (MRX) complex that is required to open and process hairpin-capped breaks formed at the location of Alu-QP [6]. The simplicity of the assay makes it attractive to assess the fragility potential of any analyzed sequence motif. However, it has several disadvantages. First, the frequency of spontaneous interchromosomal ectopic recombination is relatively high. Therefore, only repeats that induce breaks leading to recombination with frequencies higher than the background level can be assessed. Second, the Alu-QP-induced recombination frequency is very high. A print from replica-plated colonies on media lacking lysine is completely covered with Lys+ papillae making a screen for hyperfragility mutants that predispose Alu repeats for breakage problematic. Third, a screen for mutants deficient in the DSB formation and that are expected to have the hyporecombination phenotype is also difficult because a similar phenotype is exhibited by mutants that affect general DSB repair and recombination (such as rad52, rad51, rad54, etc.).

Fig. 1.

Experimental systems to study chromosomal instability induced by secondary-structure forming sequences. Breaks occurring at fragile motifs can lead to ectopic recombination. These events can be scored using strain A in which, in addition to the fragile motif inserted into the LYS2 gene, a truncated version of LYS2 (lys2-del5′) is inserted into ChrIII. Interchromosomal recombination between the two nonfunctional lys2 genes restores a wild type LYS2, allowing cells to grow on a medium lacking lysine. Strain B contains only the GCR cassette inserted into the nonessential, telomere-proximal part of ChrV. This strain is used in the GCR assay and for DSB detection. A break occurring at the fragile motif leads to formation of a 43 kb fragment, loss of which results in canavanine-resistant and adenine auxotroph (CanR Ade−) red colonies. Chromosome breaks can be directly detected by separating chromosomes on CHEF gels and using probe P1. Breaks detected after restriction digestion of the DNA are detected using probe P2

In the GCR assay (Fig. 1, strain B), lys2-carrying inverted repeats is located next to the counter-selectable CAN1 marker and ADE2 on the left arm of ChrV [4, 7]. The ~43 kb region between the left telomere and the lys2 gene does not contain essential genes and can be lost. These events can be scored by isolating canavanine-resistant, red ade2 auxotrophs. A detailed description of the assay and selective media used are presented in Fig. 1 and “Methods” below. The spontaneous rate of ChrV arm loss is extremely low: ~2 × 10 −9 cells/division. Therefore, it makes this assay very sensitive in identifying repeats even with a minor potential for instability. Insertion of Alu-QP leads to a ~10,000-fold increase in the GCR rate. The deduced mechanism for the GCRs is the formation of hairpin-capped breaks due to cruciform resolution, formation of a dicentric chromosome, breakage during anaphase, resection, and repair of broken forks via break-induced replication involving Ty or delta elements that leads to acquisition of a telomere from a nonhomologous chromosome [4]. This assay was instrumental in identifying 17 proteins involved in the maintenance of repeat stability [7, 8]. However, similar to the limitations of previously described recombination assay, caution should be taken when interpreting results leading to identification of mutants with low frequency of GCRs. For example, deficiency in one of the steps during repair of the broken chromosomes (e.g., the removal of the non-homologous tails and break-induced recombination) would be manifested as a decrease in GCR levels. However, these hypo-GCR mutants are proficient in break formation. Overall, the genetic assays described above are powerful in providing insights into mechanisms promoting, preventing, and repairing DSBs occurring at fragile motifs and can be used for genetic screens. Their sensitivity and ease of use make them a good primary approach to study inverted repeats and fragile motifs in general. Nevertheless, these genetic assays, if possible, should be accompanied by molecular techniques allowing one to physically determine the frequency of the DSB formation at a molecular level and validate the effects of the mutations.

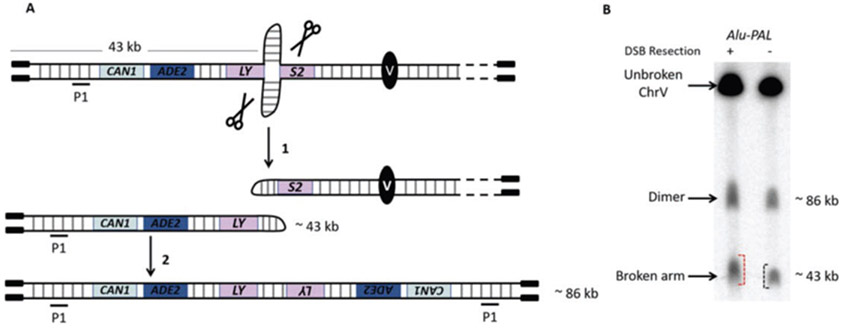

We present here a straightforward method for detection of DSBs occurring at the location of inverted repeats by Southern blot hybridization with probes designed for detection of the broken chromosome arm. We found that the minimum level of mitotic DSBs reliably detected by this method is ~1% ([7] and data not shown). One challenging issue when using this technique is to avoid breaking chromosomal DNA during the purification step. DNA purification protocols that rely on the precipitation of DNA following enzymatic or mechanical treatments inevitably yield mechanically sheared DNA and generate a high background of nonspecific bands of intensity comparable to the expected DSB bands. To overcome this problem, we embed cells directly into agarose plugs and all of the following treatments of the cells take place “in-plug” in order to preserve DNA integrity. Genomic DNA in-plug can be analyzed directly by CHEF (contour-clamped homogenous electric field) gel electrophoresis to separate broken arms (43 kb in the example we give) from intact chromosomes (585 kb). If broken fragments are long (>40 kb), they can be visualized even in resection-proficient cells. We used this approach to quantify DSB formation in wild type and sae2 mutants carrying a perfect Alu-palindrome (Fig. 2). Whereas this technique is versatile for the direct quantification of DSBs occurring at fragile motifs, it does not allow the molecular structure of the break to be deduced. Another limit of the technique is that replicating chromosomes are resistant to entering the gel due to the presence of the DNA branched structures and, therefore, only DSBs occurring outside of S phase can be detected.

Fig. 2.

Example of DSB detection by CHEF. (a) Schematic depiction of break formation at a secondary structure. Cruciform formation at inverted repeats can be targeted by nucleases leading to hairpin-capped broken ends (1). Replication of hairpin-capped chromosomal fragments leads to dimer formation, i.e., dicentric and acentric chromosomes (2). Of note, only replication of the 43 kb fragment is shown. Acentric dimers and broken arms are detected using probe P1 (the probe is specific to the HPA3 gene). (b) Example of DSB formation at an Alu-palindrome. In this example, chromosomes were separated on a 1% pulsed field agarose gel for 26 h at 6 V/cm using a two-state mode with a 120° included angle and the following electrical parameters: initial switch time = 3.14 s, final switch time = 7.68 s, ramping factor a = linear. An HPA3-specific probe was used to reveal a 585 kb band corresponding to unbroken ChrV, an 86 kb band corresponding to the acentric dimer, and a 43 kb band corresponding to the broken arm. The broken arm fragment has different migration properties depending on its resection state: in wild-type strains, opening of hairpin-capped broken ends by the MRX complex leads to resection. The resulting ssDNA-containing molecules run with delay [10] and present a more smeared profile compared to nonresected fragments observed in sae2Δ strains where MRX attack is prevented

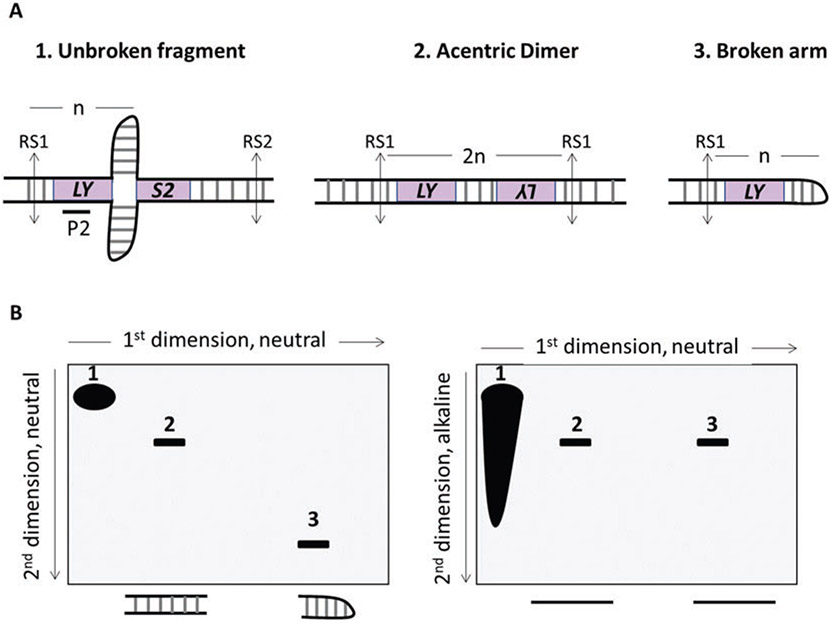

A modification of this technique is to digest agarose-embedded DNA by appropriate restriction enzymes, which allows mapping of rare DSBs in mitotic cells accurately. It is important to keep in mind that, depending on the resection range at DSBs, the result can be biased since ssDNA is refractory to restriction digestion. This makes the technique unsuitable for quantitative analysis in resection-proficient strains but rather powerful for revealing the molecular structure of the breaks. In the case of inverted repeats, deficiencies in the MRX complex or Sae2 almost completely block resection of the DSBs because termini of the broken molecules are covalently closed hairpins that require the nuclease activity of Mre11 for processing. Therefore, fine mapping of the hairpin-capped breaks using restriction digestion is greatly facilitated in mrx and sae2 mutants [6, 7]. Separation of digested, unresected DNA by alkaline two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2DGE) in the protocol described below allows one to gain insight into the molecular structure of a DSB (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Analysis of the structure of DSB formed at inverted repeats. (a) Representation of restriction digestion (vertical grey arrows) of unbroken chromosome, acentric dimer, and broken arm. “n” represents the distance between the fragile motif and the telomere-proximal restriction site (RS1). In this example, the distance between the fragile motif and the centromere-proximal restriction site (RS2) is larger than n. Therefore, the unbroken fragment runs slower than the dimer and DSB fragments (unbroken fragment > 2n, acentric dimer = 2n, broken arm = n). (b) Schematic illustration of the analysis of hairpin-capped breaks by 2DGE and migration profile of DNA molecules in (a) In neutral-neutral 2DGE, DNA molecules are separated according to their native sizes during the first and second dimension (left panel). In neutral-alkaline 2DGE, DNA molecules are separated according to their native sizes only during the first dimension. Then, DNA is denatured and the second dimension is run in alkaline conditions. Denaturation of the hairpin-capped molecules generates a linearized fragment of 2n size similar to the denatured acentric dimer. Thus, in alkaline 2DGE, the n-sized hairpin-capped break should be detected at the same position as a 2n fragment after running DNA in the second dimension

2. Materials

2.1. Recombination Assay

Strains containing a secondary-forming motif (e.g., Alu-IR) inserted into the LΥS2 gene (on ChrII or V) and a truncated version of LΥS2 (lys2-del5′allele cloned into pRS305 vector, p305L3) integrated into leu2 on ChrIII: MATα, ade5-1, his7-2, leu2-3112∷p305L3 (LEU2), trp1-289, ura3-Δ, lys2∷Alu-IR. Control strain containing a sequence without any potential to form non-B-DNA (e.g., Alu direct repeats) inserted into LΥS2.

Sterile, 96-well plates to dilute cells.

YPD plates: 10 g yeast extract (BD), 20 g peptone (BD), 20 g glucose (BD), 17 g agar (Sigma).

Synthetic medium plates without lysine: 1.4 g/l -Lys dropout (20 mg Adenine sulfate, 20 mg l-Arginine HCl, 100 mg l-Aspartic acid, 20 mg l-Histidine HCl,100 mg l-Glutamic acid, 30 mg l-Isoleucine, 100 mg l-Leucine, 20 mg l-Methionine, 400 mg l-Serine, 50 mg l-Phenylalanine, 200 mg l-Threonine, 20 mg l-Tryptophan, 30 mg l-Tyrosine, 20 mg Uracil, 150 mg l-Valine), 20 g/l glucose, 1.7 g/l Difco yeast nitrogen base without amino acids and bases, 5 g/l ammonium sulfate, 17 g/l agar.

Colony counter.

2.2. GCRs Assay

Strains containing the GCR cassette: MATa, bar1Δ, trp1Δ, his3Δ, ura3Δ, leu2Δ, ade2Δ, lys2Δ, V34205∷ADE2, lys2∷Alu-IRs.

Sterile, 96-well plates to dilute cells.

YPD plates.

Synthetic medium plates containing canavanine and low concentration of adenine: 1.4 g/l -Arg dropout (5 mg Adenine sulfate, 20 mg l-Arginine HCl, 100 mg l-Aspartic acid, 20 mg l-Histidine HCl, 100 mg l-Glutamic acid, 30 mg l-Isoleucine, 100 mg l-Leucine, 30 mg L-Lysine HCL, 20 mg l-Methionine, 400 mg l-Serine, 50 mg l-Phenylalanine, 200 mg l-Threonine, 20 mg l-Tryptophan, 30 mg l-Tyrosine, 20 mg Uracil, 150 mg l-Valine.), 20 g/l glucose, 1.7 g/l Difco yeast nitrogen base without amino acids and bases, 5 g/l ammonium sulfate, 17 g/l agar, 60 mg/l of canavanine (20 mg/ml canavanine stock solution in water).

Colony counter.

2.3. Agarose Plugs

YPD liquid media.

0.5 M EDTA pH 7.5.

Plug solution: 0.5 M EDTA pH 7.5, 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5. Autoclave and store at room temperature.

SCE solution: 1 M sorbitol, 0.1 M sodium citrate, 0.05 M EDTA, pH 7.5.

Zymolyase solution: 50 mg/ml Zymolyase 20T, 10% beta mercaptoethanol in SCE (store at −20 °C).

Low-melt (LM) agarose (Lonza) to make plugs.

Plug mold (see Note 1).

Proteinase K solution: 5 mg/ml proteinase K, 5% laurylsarcosine in 0.5 M EDTA (store at −20 °C).

2.4. CHEF

MidRange PFG ladder (NEB).

Pulsed-field certified agarose (Bio-Rad) to separate chromosomes.

0.5× TBE: 45 mM Tris-base, 45 mM boric acid, 1 mM EDTA.

Bio-Rad CHEF mapper XA apparatus.

10 mg/ml ethidium bromide.

Genescreen nylon membrane (Perkin Elmer).

Whatman filter paper.

Apparatus for electric transfer (Idea Scientific).

0.4 N NaOH.

2× SSC.

PerfecHyb Plus Hybridization Buffer (Sigma).

BcaBEST Labeling Kit (Takara) for probe labeling (see Note 2).

α-32P dCTP (Perkin Elmer).

G-50 Microspin columns (GE Healthcare).

Salmon sperm DNA.

Wash solution: 0.1× SSC, 0.1% SDS.

Phosphor screen and a suitable cassette.

2.5. Neutral-Neutral and Neutral-Alkaline 2D Gels

1× TE: 10 mM Tris–HCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.5.

Prepare freshly made 1× TE containing 1 mM PMSF (from 100 mM PMSF stock solution in isopropanol).

Restriction enzyme and its appropriate restriction buffer.

1 kb DNA ladder.

1× TBE: 89 mM Tris-base, 89 mM boric acid, 2 mM EDTA.

UltraPure Agarose to run DNA in first and second dimension.

10 mg/ml ethidium bromide.

Ruler and razor.

Horizontal electrophoresis tanks: Thermo Owl A1 large gel electrophoresis system for first dimension and Thermo Owl A5 with Built-In Recirculation for second dimension.

Alkaline buffer I: 250 mM NaOH, 5 mM EDTA pH 8.

Alkaline buffer II: 50 mM NaOH, 1 mM EDTA pH 8.

Genescreen nylon membrane.

Whatman filter paper.

Depurination solution: 0.25 N HCl.

Denaturation solution: 0.5 N NaOH, 1.5 M NaCl.

Neutralization solution: 1.5 M NaCl, 1 M Tris–HCl, pH adjusted to 7.4.

PerfecHyb Plus hybridization buffer.

10× SSC.

BcaBEST Labeling Kit for probe labeling.

α-32P dCTP.

G-50 Microspin columns.

Salmon sperm DNA.

Wash solution: 0.1× SSC, 0.1% SDS.

Stratagene’s PosiBlot 30–30 pressure blotter and pressure control station (or custom-made posiblotter).

Phosphor screen and a suitable cassette.

3. Methods

3.1. Fluctuation Test to Score for Homologous Recombination Events (See Note 3)

Streak out the strains to be tested on YPD plates and culture at 30 °C for 3 days to obtain single colonies.

Select 14 colonies per strain and resuspend each colony in 200 μl of water in a 96-well plate.

Perform a five-step 1:10 serial dilution of all suspensions.

Depending on the colony size, plate either the 1/10000 or 1/100000 dilution on YPD plates (2 × 100 μl). This will allow cell viability/plating efficiency to be defined.

Plate the 0 dilution for the control and 1/100 dilution for the strains with Alu-QP on -Lys plates (2 × 90 μl).

Incubate at 30 °C until the colonies can be counted.

Determine the rate and confidence interval of recombination between lys2 alleles using the number of colonies on YPD and corresponding selective media plates.

3.2. Fluctuation Test to Score for GCR Events (See Notes 3 and 4)

Streak out the strains to be tested on YPD plates and culture at 30 °C for 3 days to obtain single colonies.

Select 14 colonies per strain and resuspend each colony in 200 μl of water on a 96-well plate.

Perform a five-step 1:10 serial dilution.

Depending on the colony size, plate either the 1/10000 or 1/100000 dilution on YPD plates (2 × 100 μl). This will allow cell viability/plating efficiency to be defined.

Plate the 1/100 or 1/1000 dilution on canavanine-containing plates (2 × 90 μl).

Incubate the plates at 30 °C until the colonies grow and can be counted (see Note 5).

Determine the rate and confidence interval of GCRs using the number of colonies on YPD plates and the number of red colonies on corresponding selective media plates.

3.3. Cell Embedding in Agarose Plugs

A challenge in DSB detection is to yield intact purified DNA. Therefore, this protocol has been optimized to avoid mechanical shearing of DNA molecules as much as possible. By embedding cells into agarose plugs, spheroplasting cells in plugs, and keeping plugs at temperatures below 30 °C, DNA integrity is maintained.

Select a single colony and grow cells overnight in 10 ml of YPD (see Note 6) until saturation is reached.

Determine cell density by counting the cells using a hemocytometer.

Pellet the cells and resuspend in 1 ml of water.

Transfer between 4 and 8 × 108 cells per plug to a 2 ml microcentrifuge tube, pellet, and remove supernatant.

Prepare 1.5% LM agarose in 0.1 M EDTA pH 7.5 and keep solution at 50 °C (see Note 7).

Add plug solution to the pellet to reach a total volume of 70 μl. Vortex briefly.

Add 10 μl of zymolyase solution. Vortex briefly.

Warm the cells in 50 °C water bath and add 80 μl of preheated, 1.5% LM agarose. Keep the cells at 50 °C for the minimum time required to mix the cells with the LM agarose.

Load the suspension into the plug mold immediately using a 200 μl micropipette.

Repeat steps 6–9 for each sample.

Allow the plugs to solidify 5–10 min at 4 °C.

Push the plugs into microcentrifuge tubes containing 800 μl of plug solution and 10 μl of zymolyase solution (see Note 8).

Incubate 2 h to overnight at 30 °C.

Add 200 μl of proteinase K solution and incubate several hours to overnight at 30 °C.

Replace the proteinase K solution with 1 ml of fresh plug solution.

Store plugs at 4 °C.

3.4. CHEF Analysis

Prepare 3 l of 0.5× TBE.

Slice the plugs to the desired length.

Equilibrate each sliced plug in running buffer (0.5× TBE) for 30 min.

Prepare 1% pulsed field certified agarose gel in running buffer and cool to 50–55 °C (see Note 9).

Align each plug and a very thin slice of PFG marker along the top of the gel tray.

Immobilize the plugs by applying melted agarose with a 1 ml micropipette and allowing the agarose to partially solidify.

Pour the remaining gel and allow to solidify.

Add the remaining prepared 0.5× TBE to the CHEF mapper tank and chill to 14 °C.

Run the gel using the appropriate parameters (see example in Fig. 2b).

Stain the gel with 0.5 μg/ml ethidium bromide in 0.5× TBE and cut the region to be transferred.

Transfer DNA in 0.5× TBE at 12 V for 2–4 h (see Note 10).

Crosslink DNA to the membrane by exposing it to 120 mJ of UV-C.

Soak the membrane in 0.4 N NaOH for 10 min to denature DNA.

Wash the membrane in 2× SSC for 10 min.

Proceed to hybridization as described in Subheading 3.6 (see Note 11).

3.5. Neutral-Neutral and Neutral-Alkaline 2DGE

3.5.1. In-Plug Digestion of Agarose-Embedded DNA

Slice the plugs to the desired length and transfer them to a 24-well plate. Prepare two slices per strain (see Note 12).

Wash the plugs twice in 1× TE for 30 min.

Wash in 1× TE containing 1 mM PMSF for 1 h.

Wash in H2O for 30 min.

Transfer the plugs to 2 ml microcentrifuge tubes.

Incubate in 200 μl of 2× restriction enzyme buffer for 1 h.

Incubate in 200 μl of 1× restriction enzyme buffer for 1 h.

Add 50 units of restriction enzyme.

Incubate at 37 °C overnight.

Add 25 units of restriction enzyme and incubate for 3 additional hours.

Remove digestion solution and equilibrate the plugs in 200 μl of 1× TBE.

3.5.2. Running DNA in the First Dimension

Prepare a plug containing a 1 kb ladder by mixing 15 μl of 1 kb ladder with 15 μl of LM agarose.

Align the plugs and the 1 kb ladder plug along the top of the gel tray. Leave ~0.5–1 cm or more between each plug.

Prepare 250 ml of 0.7–1% agarose gel in 1× TBE. Cool to 50–55 °C.

Immobilize the plugs by applying melted agarose with a 1 ml micropipette.

Pour the remaining gel and allow it to solidify.

Add 1.5 l of 1× TBE to an Owl A1 electrophoresis tank.

Carefully place the gel tray in the tank ensuring it is not floating and it is submerged in running buffer.

Run at slow voltage (<50 V). Running time depends on the size of the fragments of interest.

Stain the gel with 1× TBE containing 0.5 μg/ml of ethidium bromide for 20–30 min.

Using a UV transilluminator (see Note 13), cut the gel horizontally 1 cm below the smallest fragment of interest. Make another horizontal cut to include unbroken and DSB fragments. Then, cut vertically by positioning the ruler 1 mm away from the DNA lane to obtain slices about 1.5 cm wide. Each slice contains the DNA of one sample located close to the edge of the slice.

3.5.3. Running DNA in the Second Dimension

In the case of neutral/alkaline 2DGE, incubate the gel slices in 10 mM EDTA and then in 5 mM EDTA for 30 min each.

Place and align the gel slices, rotated by 90° on the top part of the second-dimension gel tray. The DNA-containing part of the gel slice should be in contact with the gel to be poured.

Prepare a plug containing a 1 kb ladder by mixing 15 μl of 1 kb ladder with 15 μl of LM agarose. Place it in between the two gel slices.

Prepare 350 ml of 1% agarose gel in 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA for the alkaline condition, and in 1× TBE for the neutral condition. Cool the melted agarose quickly on ice until it reaches 50–55 °C and add 17.5 μl of ethidium bromide.

Pour the agarose gel and allow it to solidify at room temperature.

For neutral conditions, proceed directly to step 9.

For alkaline conditions, soak the solidified gel in alkaline buffer I for 30 min (see Note 14).

Incubate the gel in alkaline buffer II for 30 min (see Note 14).

In a cold room, pour 2 l of prechilled alkaline buffer II in the Owl A5 electrophoresis tank and 2 l of prechilled 1× TBE in a second tank.

Place the trays containing the gels carefully in the corresponding tank and ensure the gels are not floating.

Run the gels at 0.7 V/cm based on the size of the fragments to be separated (see Note 15).

Cut the top part of the gel to remove the 0.7% agarose slice.

Transfer DNA to a positively charged nylon membrane according to Subheading 3.5.4.

3.5.4. DNA Transfer

Soak the neutral-neutral gel in depurination solution for 15–20 min (see Notes 16 and 17).

Soak the neutral-neutral gel in denaturation solution for 20–30 min (see Note 17).

Soak the neutral-neutral and neutral-alkaline gels in neutralization solution for 30 min or more.

While treating the gel, cut a membrane to be slightly larger than the gel and soak in 10× SSC.

To set up the transfer, place a piece of Whatman paper on the blotting tank, wet it with 10× SSC and remove bubbles.

Place the presoaked nylon membrane on top of the Whatman paper.

Place the plastic mask and adjust the position of the membrane such that the edges are covered by the mask and remove bubbles.

Place the gel on the membrane. The gel should slightly overlap the mask. Ensure that no bubbles are trapped between the membrane and the gel.

Place a sponge soaked with 400 ml of 10× SSC on the gel. Do not squeeze out buffer from the sponge.

Close the lid on the blotting tank tightly.

Transfer for 2–4 h at 70 mmHg.

Crosslink DNA to the membrane by exposing it to 120 mJ of UV-C.

Proceed to hybridization as described in Subheading 3.6.

3.6. Hybridization

3.6.1. Prehybridization

Prewarm hybridization buffer to 68 °C.

Roll the membrane and place it in a roller tube.

Add 7.5–10 ml of prewarmed hybridization buffer.

Incubate at 68 °C in a hybridization oven for at least 5 min. Meanwhile, label the probe using BcaBEST™ Labeling Kit according to Subheading 3.6.2.

3.6.2. Probe Labeling

In a microcentrifuge tube with a tight closure, mix 10 ng to 1 μg of template DNA with 2 μl of random primers. Add H2O to reach a final volume of 16.5 μl.

Heat the mix at 95 °C for 3 min and cool on ice for 5 min.

Add 2.5 μl of 10× buffer, 2.5 μl of dNTP mixture, and 2.5 μl of radiolabeled dCTP (1.8 MBq, 50 μCi).

Add 1 μl of DNA polymerase and incubate at 53 °C for at least 30 min.

Prepare a G-50 spin column by centrifuging for 1 min at 750 × g to remove storage buffer.

Place the ready to use column in a fresh microcentrifuge tube.

Apply the probe to the center of column without touching the resin.

Centrifuge for 1 min at 735 × g.

Add 100 μl of salmon sperm DNA to the purified probe.

Heat at 95 °C for 3 min and cool on ice for 5 min.

Transfer the denatured probe to 7.5–10 ml of preheated hybridization buffer.

Remove the prehybridization buffer and add the new buffer containing the labeled probe.

Incubate in a hybridization oven at 68 °C overnight.

Transfer the membrane to a plexiglass wash box.

Preheat the wash solution to 70 °C.

Pour 400 ml of the preheated wash solution on the membrane and incubate for 15 min with shaking.

Remove the wash solution and repeat steps 15 and 16.

Dry the membrane and wrap it in sealed and impervious plastic (see Note 17).

Place the membrane on a blanked phosphor screen and expose from overnight to several days (see Note 18).

Scan the screen (see Note 19).

Footnotes

The wells of the mold can be of different sizes. Disposable plug molds with wells holding 85 μl of volume can be purchased from BioRad. We use custom-made Teflon-based plug molds with 170 μl rectangular wells.

This kit provides buffer, dNTPs (dATP, dGTP, and dTTP), and polymerase.

The formula μ = f/ln(Nμ) was used to calculate the rates of recombination and GCRs [9].

The structure of rearranged ChrV in GCR clones can be analyzed by CHEF according to Subheadings 3.3 and 3.4.

Cells grow more slowly on canavanine-containing low-adenine medium than on YPD.

Other media may be used if selection must be maintained.

1.5% or 3% LM agarose can be prepared, aliquoted in microfuge tubes, and stored at room temperature. Before using, heat the agarose at 70 °C to melt and then keep the solution at 50 °C.

If more than one plug is made per strain, use 2 ml microfuge tubes and place 3 plugs/tube.

The gel concentration depends on the DNA fragments to be separated. To obtain crisp DNA bands and avoid diffusion, the concentration of the gel should be higher than the final concentration of the LM agarose contained in the plugs.

Electric transfer of DNA is rapid and efficient. Alkaline transfer and capillary transfer work as efficiently, though. The method described in Subheading 3.5.4 can be used as well.

The region of the chromosome to label with dCTP 32P should be chosen carefully to avoid nonspecific signals and appearance of additional bands.

One slice is for neutral-neutral conditions, and the second is for neutral-alkaline conditions.

Use a long-wavelength UV transilluminator (365 nm) to visualize DNA and cut the first dimension gel. Minimize as much as possible exposure of the gel to UV light as it favors DNA breakage.

Keep the gel on its tray during incubation and handle it carefully as incubation in alkaline solution makes the gel buoyant and slippery.

Ethidium bromide–stained DNA migrating in neutral condition can be followed using a UV lamp. In the alkaline condition, DNA cannot be highlighted as it is denatured.

1–2 μl of 10x loading dye can be included in a corner of the gel. Depurination can be stopped when the color turns bright yellow/green.

In the case of neutral-alkaline conditions, steps 1 and 2 are omitted.

Saran wrap or plastic sheet protectors can be used.

Alternatively, membranes can be exposed to Kodak BioMax film.

References

- 1.Mehta A, Haber JE (2014) Sources of DNA double-strand breaks and models of recombinational DNA repair. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 6(9):a016428 10.1101/cshperspect.a016428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaushal S, Freudenreich CH (2019) The role of fork stalling and DNA structures in causing chromosome fragility. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 58(5):270–283. 10.1002/gcc.22721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim HM, Narayanan V, Mieczkowski PA, Petes TD, Krasilnikova MM, Mirkin SM, Lobachev KS (2008) Chromosome fragility at GAA tracts in yeast depends on repeat orientation and requires mismatch repair. EMBO J 27 (21):2896–2906. 10.1038/emboj.2008.205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Narayanan V, Mieczkowski PA, Kim HM, Petes TD, Lobachev KS (2006) The pattern of gene amplification is determined by the chromosomal location of hairpin-capped breaks. Cell 125(7):1283–1296. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lobachev KS, Stenger JE, Kozyreva OG, Jurka J, Gordenin DA, Resnick MA (2000) Inverted Alu repeats unstable in yeast are excluded from the human genome. EMBO J 19(14):3822–3830. 10.1093/emboj/19.14.3822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lobachev KS, Gordenin DA, Resnick MA (2002) The Mre11 complex is required for repair of hairpin-capped double-strand breaks and prevention of chromosome rearrangements. Cell 108(2):183–193. 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00614-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y, Saini N, Sheng Z, Lobachev KS (2013) Genome-wide screen reveals replication pathway for quasi-palindrome fragility dependent on homologous recombination. PLoS Genet 9(12):e1003979 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y, Shishkin AA, Nishida Y, Marcinkowski-Desmond D, Saini N, Volkov KV, Mirkin SM, Lobachev KS (2012) Genome-wide screen identifies pathways that govern GAA/TTC repeat fragility and expansions in dividing and nondividing yeast cells. Mol Cell 48(2):254–265. 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drake JW (1991) A constant rate of spontaneous mutation in DNA-based microbes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 88(16):7160–7164. 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Westmoreland J, Ma W, Yan Y, Van Hulle K, Malkova A, Resnick MA (2009) RAD50 is required for efficient initiation of resection and recombinational repair at random, gamma-induced double-strand break ends. PLoS Genet 5(9):e1000656 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]