Abstract

Objectives

1. To assess the performance of an extended questionnaire in identifying cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection among obstetric patients. 2. To evaluate the rate of infection among healthcare workers involved in women’s care.

Study design

A prospective cohort study of obstetric patients admitted to MBBM Foundation and Buzzi Hospital (Lombardy, Northern Italy) from March 16th to May 22nd, 2020. Women were screened on admission by a questionnaire investigating major and minor symptoms of infection and high-risk contacts in the last 14 days. SARS-CoV-2 assessment was performed by RT-PCR on nasopharyngeal swabs. Till April 7th, a targeted SARS-CoV-2 testing triggered by a positive questionnaire was used; from April 8th, a universal testing approach was implemented.

Results

There were 1,177 women screened by the questionnaire, which yielded a positive result in 130 (11.0%) cases. SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR was performed in 865 (73.5%) patients, identifying 51 (5.9%) infections. During the first period, there were 29 infected mothers, 4 (13.8%) of whom had a negative questionnaire. After universal testing implementation, there were 22 (3%, 95% CI 1.94% - 4.04%) infected mothers, 13 (59.1%) of whom had a negative questionnaire; rate of infection among asymptomatic women was 1.9%. Six of the 17 SARS-CoV-2-positive women with a negative questionnaire reported symptoms more than 14 but within 30 days before admission. Isolated olfactory or taste disorders were identified in 15.7% of infected patients. Rate of infection among healthcare workers was 5.8%.

Conclusions

An exhaustive triage questionnaire can effectively discriminate women at low risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the context of a targeted and a universal viral testing approach. In 15.7% of infected women, correct classification as a suspected case of infection was due to investigation of olfactory and taste disorders. Extension of the assessed time-frame to 30 days may be worth considering to increase the questionnaire’s performance.

Introduction

The novel Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has caused a new, unexpected public health emergency. Italy has been particularly affected, with Lombardy being the country epicenter of the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak [1, 2].

Obstetric patients and their caring physicians face unique challenges for their need of in-person visits and hospital admission for delivery.

Identification of suspected cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection at admission is essential for correctly applying isolation measures and use of personal protective equipment (PPE), thus protecting the women, their newborns, and the healthcare workers (HCWs).

Universal screening by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) of nasopharyngeal swabs has been proposed as the optimal approach [3–6]. However, limited testing supplies and laboratory workforce may prevent its application in some clinical settings [7]. In addition, although a rapid laboratory testing has been developed [6], most hospitals rely on standard tests with a 5 to 24 hour-turn-around time [8, 9]. This may be a problem when caring for a laboring woman in whom delivery can occur before the RT-PCR result is available.

A targeted screening guided by a structured questionnaire may represent a feasible and valid alternative [5, 10, 11]. Yet, this approach has been questioned due to evidence of high rates of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection in the obstetric population [4, 6, 12, 13]. However, only major respiratory symptoms were assessed in these studies. Since minor symptoms, such as loss of smell or taste, have been described at earlier stages of infection and also as isolated symptoms in milder forms of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) [14–20], the possibility of some women being erroneously classified as asymptomatic in these reports has to be considered.

Here we report our data on the use of a comprehensive admission questionnaire for obstetric patients, including both major and minor symptoms of infection as well as high-risk contacts and living environment. Accuracy of the questionnaire in the context of both a targeted and a universal SARS-CoV-2 screening by RT-PCR on nasopharyngeal swabs in two consecutive periods of the outbreak is assessed and discussed herein.

Secondary objective of the study was the assessment of the SARS-CoV-2 infection rate among the HCWs involved in patients’ management.

Material and methods

This was a prospective cohort study of all women admitted to the Obstetric Unit of MBBM Foundation at San Gerardo Hospital and Vittore Buzzi Hospital during pregnancy or the postpartum period from March 16th to May 22nd, 2020.

These hospitals are located in the Milan area, Lombardy region, Northern Italy, and perform approximately 5,600 deliveries per year. Since the beginning of March, strict lockdown measures were in place in this geographic area, which entered a deceleration phase of the outbreak in mid-April [1].

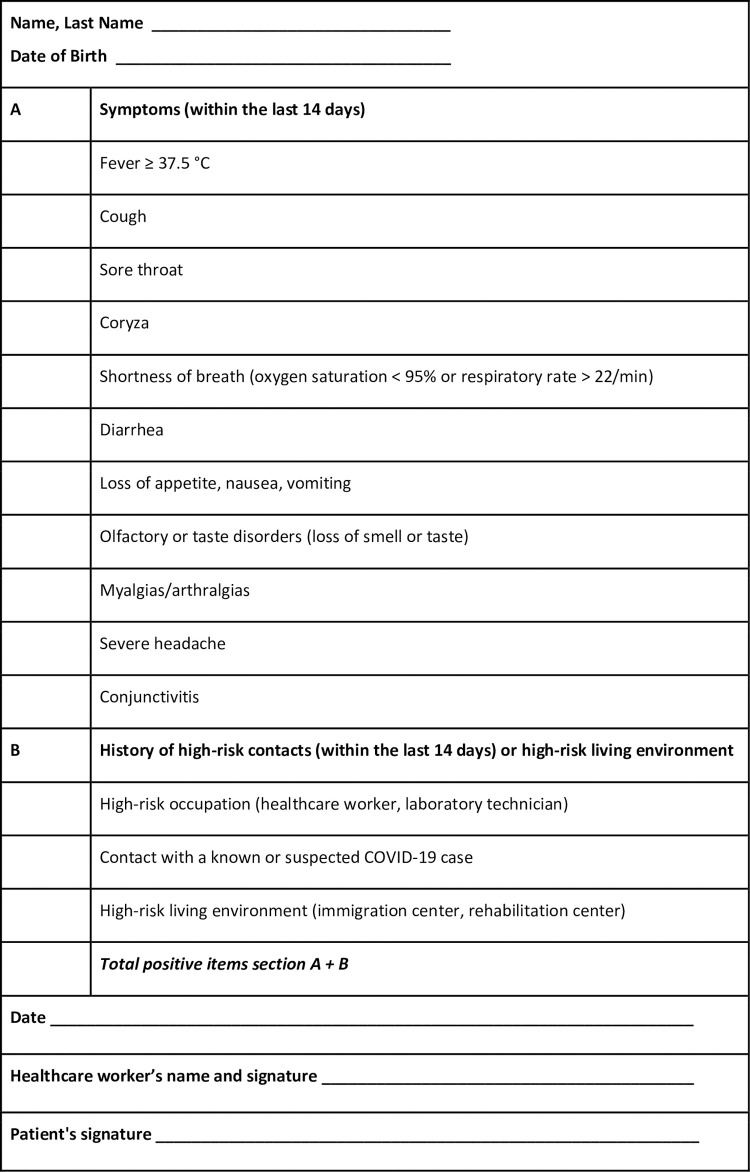

Starting on March 16th, a comprehensive questionnaire including both major and minor symptoms of infection and high-risk contacts in the last 14 days as well as a high-risk living environment (i.e., immigration centers, drug rehabilitation centers) was administered to all women at hospital admission (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Admission questionnaire.

Adapted from Poon et al. [11].

The questionnaire was deemed positive when at least one positive answer was present. Support persons (one for each woman) were also screened by means of the questionnaire, and refused hospital access in case of a positive result. Both patients and their support persons were given surgical masks and asked to wear them during their hospital stay; they were also instructed to practice frequent hand sanitization. In addition, all HCWs involved in women’s care underwent questionnaire assessment (section A) at the beginning of every shift and wore a surgical mask for the entire shift duration, unless different PPE were required, as means of source control [21, 22].

Initially, a targeted SARS-CoV-2 screening approach triggered by a positive questionnaire and based on RT-PCR testing of nasopharyngeal swabs was used in women with hospital admission after accessing the Emergency Department. In turn, a universal screening was applied to all patients with scheduled admission (i.e., elective pre-labor cesarean section). On April 8th, we changed our policy and started testing all women for SARS-CoV-2 infection independent of the type of hospital admission and the questionnaire result, in agreement with a disposition of the Lombardy Region Health Care Authority.

Cases with scheduled admission underwent RT-PCR testing 24–48 hours in advance in a designated drive-through testing center so results would be available at the time of hospital access to guide isolation measures and use of PPE. Instead, questionnaire results were used for this purpose in cases of unscheduled admission: women with a positive questionnaire were classified as persons under investigation (PUI) and managed accordingly while nucleic acid test results were pending, whereas women with a negative questionnaire were considered not at risk until the result of the RT-PCR test was available.

Nasopharyngeal sampling was performed by a trained resident physician or midwife in appropriate PPE using dedicated swabs. Samples were transferred to the laboratory and processed by RT-PCR testing SARS-CoV-2 with the automated ELITe InGenius system and the GeneFinder COVID-19 Plus RealAmp Kit assay, according to manufacturer’s instructions. This assay targets three genes, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, nucleocapsid protein, and envelope membrane protein, with high specificity. Test results were available in 5 to 24 hours and scored as “positive” or “negative” in both hospitals [9].

Viral testing was also performed in all HCWs involved in patients’ management.

The accuracy of the questionnaire to predict SARS-CoV-2 infection in both study periods (March 16th to April 7th and April 8th to May 22nd) was tested by constructing a 2x2 table and calculating sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, positive likelihood ratio (sensitivity/1-specificity), and negative likelihood ratio (1-sensitivity/specificity).

The study was approved by the IRB of the University of Milan-Bicocca and the University of Milan (#15408/2020). A written informed consent was obtained for all women involved in the study.

Results

A total of 1,177 women were assessed at hospital admission by the questionnaire during the study period (n = 447 at MBBM Foundation at San Gerardo Hospital and n = 730 at Vittore Buzzi Hospital). Nine-hundred and forty-five (80.3%) women were admitted to the L&D unit, whereas 196 (16.7%) and 36 (3.0%) women to the antepartum and postpartum unit, respectively.

Of the 1,177 patients assessed, 865 (73.5%) were tested for SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR on nasopharyngeal swab and 51 (5.9%) were positive.

Between March 16th and April 7th, RT-PCR testing was performed in 129 out of 441 patients. Questionnaire was positive on admission in 63 (14.3%) women. Among the 319 patients with unscheduled admission and a negative questionnaire, 7 (2.2%) were tested for SARS-CoV-2 during hospitalization because of onset of fever. All of them were negative.

SARS-CoV-2 infection was diagnosed in 29 mothers, 4 (13.8%) of whom had a negative questionnaire. One of these 4 patients failed to report high-risk contacts (i.e., fever and cough in close family members a few days before admission). An additional 2 women revealed symptoms suggestive of SARS-CoV-2 infection occurring more than 2 weeks but within one month before admission. None of the 4 patients developed symptoms during hospitalization.

After implementing universal viral screening, we identified 67/736 positive questionnaires. Nasopharyngeal swab analysis by RT-PCR recognized 22 (3%, 95% CI 1.94% - 4.04%) cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Questionnaire was negative in 13 (59.1%) of them, for a rate of infection among asymptomatic women of 1.9%. Four out of these 13 women reported loss of taste or smell more than 14 days but within one month before admission. None of the 13 patients developed symptoms during hospitalization.

Accuracy of the questionnaire to predict SARS-CoV-2 infection in both study periods is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Accuracy of the admission questionnaire in the two study periods.

| First study period (March 16th–April 7th, 2020) | |||

| - Targeted SARS-CoV-2 screening - | |||

| Positive RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2 | Negative RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2 | Total | |

| Positive questionnaire | 25 | 38 | 63 |

| Negative questionnaire | 4 * | 55 | 59 |

| Total | 29 | 93 | 122 |

| • Sensitivity = 25/29, 86.2%; specificity = 55/93, 59.1% | |||

| • Positive predictive value = 25/63, 39.7%; negative predictive value = 55/59, 93.2% | |||

| • Positive likelihood ratio = 2.11; negative likelihood ratio = 0.23 | |||

| Second study period (April 8th–May 22nd, 2020) | |||

| - Universal SARS-CoV-2 screening - | |||

| Positive RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2 | Negative RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2 | Total | |

| Positive questionnaire | 9 | 58 | 67 |

| Negative questionnaire | 13 # | 656 | 669 |

| Total | 22 | 714 | 736 |

| • Sensitivity = 9/22, 40.9%; specificity = 656/714, 91.9% | |||

| • Positive predictive value = 9/67, 13.4%; negative predictive value = 656/669, 98.1% | |||

| • Positive likelihood ratio = 5.13; negative likelihood ratio = 0.64 | |||

* One patient failed to report exposure to high-risk contacts a few days before admission, and two patients reported fever and dry cough (n = 1) and loss of smell and taste (n = 1) more than 14 days but within 30 days before admission.

# Four patients reported loss of smell or taste more than 14 days but within 30 days before admission.

Detailed assessment of positive questionnaires showed that fever ≥ 37.5°C was the most common positive item (42.3%), followed by high-risk contacts/living environment (30.8%), cough (25.4%), gastrointestinal symptoms (13.8%), and loss of smell or taste (11.5%) (Fig 2A).

Fig 2.

Distribution of positive questionnaire items among women with a positive questionnaire on admission (A) and with a positive SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR testing (B) during the study period. Fever was considered for values ≥37.5°C; shortness of breath was defined as oxygen saturation <95% or respiratory rate >22/min; GI (gastrointestinal) symptoms included loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea; high-risk contacts refer to high-risk occupation, contact with a known or suspected COVID-19 case and high-risk living environment. Period I: from March 16th to April 7th, 2020; Period II: from April 8th to May 22nd, 2020.

Fever and cough were more commonly identified during the first study period compared to the second one (57.1% versus 23.4% and 30.2% versus 20.9%, respectively), whereas gastrointestinal symptoms displayed an opposite trend (7.9% versus 19.4%). Rate of olfactory and taste disorders, as well as of high-risk contacts/living environment, remained stable over time.

Of the fifteen women who reported loss of smell or taste within 14 days before admission, this was the only positive questionnaire item in three. Also, when the time-frame of investigation was extended to the last 30 days before admission, an additional five mothers were identified with isolated olfactory or taste disorders. All these eight patients tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.

Frequency and time-trend of positive questionnaire items among SARS-CoV-2 infected women is shown in Fig 2B.

There were 307 HCWs involved in patients’ management in both hospitals during the overall study period. Eighteen of them (5.8%) tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. There were no cases of moderate or severe COVID-19.

Discussion

Our study investigated the accuracy of a comprehensive questionnaire thoroughly assessing obstetric patients upon hospital admission to identify cases suspected for SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Differently from previous reports [4, 6–8, 13], our questionnaire evaluated the presence of not only major respiratory symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection, including fever, cough, and shortness of breath, but also minor symptoms, such as loss of smell or taste, as well as high-risk contacts during the last two weeks preceding admission.

We observed a negative predictive value for SARS-CoV-2 infection of 93.2% and 98.1% in the context of a targeted and a universal viral screening, respectively, in two consecutive periods of the outbreak. In addition, we identified a low rate of viral infection among the HCWs involved in women’s care [23–25].

The ability of accurately discriminating women at low risk for infection is pivotal in case of both a targeted and a universal SARS-CoV-2 screening. In clinical settings with no ability to perform a universal testing, a well-performing admission questionnaire can adequately guide a targeted screening approach and still allow protection of the patients and the HCWs. On the other hand, when a universal screening approach is feasible, the questionnaire allows appropriate patients’ cohorting and application of isolation measures and contact precautions while RT-PCR results are pending. This is particularly important to prevent potential viral spread to other patients and HCWs and mother-to-child transmission when caring for laboring women, in whom delivery can occur before nucleic acid test results are available. In fact, turn-around time of RT-PCR testing is usually >5 hours in most facilities [8, 9] and availability of rapid testing is limited [6].

Much of the push for implementation of a universal screening with SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR hinges on avoiding unintended exposures to HCWs when caring for an asymptomatic patient, especially in geographic areas with a high community prevalence of COVID-19 [26, 27]. Our hospitals are located in the epicenter of SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in Italy [1, 2]. Nonetheless, we had only 1.9% asymptomatic, SARS-CoV-2 positive women during the universal screening period. This rate is 7 times lower than that reported by other centers in similarly hardly hit areas, such as New York City [4, 6]. A different phase of the outbreak during the study period may have contributed to this difference [1, 28]. However, our detailed investigation of minor symptoms, such as loss of smell or taste, may also have played an important role [3, 29]. Olfactory and taste disorders have been reported as the only symptoms of infection in up to 17% of SARS-CoV-2 positive individuals, and to display a higher predictive ability of having the virus than fever or persistent cough [16, 18, 19]. Isolated loss of smell or taste was identified in 15.7% of our virally infected patients. In addition, frequency of olfactory and taste disorders did not differ between the two study periods, whereas that of fever and cough displayed a substantial reduction (Fig 2A and 2B). These data suggest that patients’ assessment upon admission during an outbreak by a novel air-tract pathogen should include not only major respiratory but also minor symptoms, especially in the more advanced phases of the outbreak.

Prolonged SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR positivity at more than 2 weeks from symptom onset has been reported in infected individuals [30, 31]. Overall, we identified 51 women with SARS-CoV-2 infection, and in 17 (33.3%) questionnaire upon admission was deemed negative. However, 6 (35.3%) of these patients reported symptoms suggestive of infection more than 14 but within 30 days before hospital admission. Had the questionnaire investigated a one-month time-frame, negative predictive values would have increased to 98.2% and 98.6% in the targeted and the universal viral screening period, respectively. Of note, whether such patients would have been infectious and thus able to spread the virus at the time of admission is still a matter of debate [32–36]. Similarly, the infectiousness of fully asymptomatic women with positive SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR results is unclear [31, 33, 36–38]. Unfortunately, we could not address this issue in our patients since we did not perform viral culture experiments [33, 34]. Nonetheless, independent of the infectiousness potential of these women, widespread use of face masks and frequent hand sanitization have likely contributed to successful viral spread control in our units [21, 22].

Strengths of our study are the following. First, it was conducted in two large teaching hospitals in the Italian epicenter of the outbreak, thus providing useful data for equally affected areas. Second, it investigated the questionnaire’s performance in the context of both a targeted and a universal viral screening approach in two consecutive periods of the outbreak. Third, it assessed the universal screening approach over a 6-week time period, which may have allowed to better capture the real trend of infection over time among obstetric patients than much shorter study periods [4, 6, 8].

Admission questionnaires may have limitations since they rely on honest answering. The possibility of patients being not completely sincere due to fear of isolation measures, especially in laboring women, has to be considered. This event occurred in at least one woman in our cohort. Addition of objective, point-of-care parameters, such as lymphocyte count and lung ultrasound, to the admission screening procedure to increase its accuracy may be worth exploring [7, 10, 27, 31, 39–41].

Another limitation of our study is that SARS-CoV-2 testing by RT-PCR on nasopharyngeal swabs was performed in a targeted manner during the first study period, thus leading to 312 untested women. This also prevented a meaningful comparison of infection rates between the two study periods with a targeted and a universal SARS-CoV-2 testing approach, respectively.

Conclusions

With recognition that a “one-size-fits-all” approach is unlikely to be justifiable [26], decisions regarding universal viral testing should be made in the context of regional prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection as well as financial and human resources and PPE availability in each obstetric unit.

Our data show that thorough assessment of obstetric patients upon hospital admission by means of an exhaustive questionnaire is feasible and effective in discriminating women at low risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the context of both a targeted and a universal screening approach. Extension of the investigated time-frame from 14 to 30 days may be worth considering to increase the questionnaire’s performance, especially in this high-risk population. The question remains whether this group of women, as well as of those SARS-CoV-2 positive but fully asymptomatic, represents an actual source of viral spread.

Abbreviations

- SARS-CoV-2

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2

- PPE

personal protective equipment

- HCWs

healthcare workers

- RT-PCR

reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

- COVID-19

coronavirus disease

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Dipartimento della Protezione Civile. COVID-19 Italia—Monitoraggio della situazione. 2020.

- 2.Grasselli G, Pesenti A, Cecconi M. Critical Care Utilization for the COVID-19 Outbreak in Lombardy, Italy: Early Experience and Forecast During an Emergency Response. Jama. 2020. Epub 2020/03/14. 10.1001/jama.2020.4031 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller ES, Grobman WA, Sakowicz A, Rosati J, Peaceman AM. Clinical Implications of Universal Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Testing in Pregnancy. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2020. Epub 2020/05/21. 10.1097/aog.0000000000003983 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sutton D, Fuchs K, D'Alton M, Goffman D. Universal Screening for SARS-CoV-2 in Women Admitted for Delivery. The New England journal of medicine. 2020;382(22):2163–4. Epub 2020/04/14. 10.1056/NEJMc2009316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tassis B, Lunghi G, Frattaruolo MP, Ruggiero M, Somigliana E, Ferrazzi E. Effectiveness of a COVID-19 screening questionnaire for pregnant women at admission to an obstetric unit in Milan. International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics: the official organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2020;150(1):124–6. Epub 2020/05/06. 10.1002/ijgo.13191 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vintzileos WS, Muscat J, Hoffmann E, John NS, Vertichio R, Vintzileos AM, et al. Screening all pregnant women admitted to labor and delivery for the virus responsible for coronavirus disease 2019. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2020. Epub 2020/04/30. 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.04.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duffy CR, Hart JM, Modest AM, Hacker MR, Golen T, Li Y, et al. Lymphopenia and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Infection Among Hospitalized Obstetric Patients. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2020. Epub 2020/05/21. 10.1097/aog.0000000000003984 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naqvi M, Burwick RM, Ozimek JA, Greene NH, Kilpatrick SJ, Wong MS. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Universal Testing Experience on a Los Angeles Labor and Delivery Unit. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2020. Epub 2020/05/21. 10.1097/aog.0000000000003987 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Savasi VM, Parisi F, Patanè L, Ferrazzi E, Frigerio L, Pellegrino A, et al. Clinical Findings and Disease Severity in Hospitalized Pregnant Women With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Obstetrics and gynecology. 2020. Epub 2020/05/21. 10.1097/aog.0000000000003979 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oza S, Sesay AA, Russell NJ, Wing K, Boufkhed S, Vandi L, et al. Symptom- and Laboratory-Based Ebola Risk Scores to Differentiate Likely Ebola Infections. Emerging infectious diseases. 2017;23(11):1792–9. Epub 2017/10/20. 10.3201/eid2311.170171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poon LC, Yang H, Lee JCS, Copel JA, Leung TY, Zhang Y, et al. ISUOG Interim Guidance on 2019 novel coronavirus infection during pregnancy and puerperium: information for healthcare professionals. Ultrasound in obstetrics & gynecology: the official journal of the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2020;55(5):700–8. Epub 2020/03/12. 10.1002/uog.22013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Breslin N, Baptiste C, Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Miller R, Martinez R, Bernstein K, et al. COVID-19 infection among asymptomatic and symptomatic pregnant women: Two weeks of confirmed presentations to an affiliated pair of New York City hospitals. American journal of obstetrics & gynecology MFM. 2020:100118 Epub 2020/04/16. 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khalil A, Hill R, Ladhani S, Pattisson K, O'Brien P. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in pregnancy: symptomatic pregnant women are only the tip of the iceberg. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2020. Epub 2020/05/11. 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gautier JF, Ravussin Y. A New Symptom of COVID-19: Loss of Taste and Smell. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md). 2020;28(5):848 Epub 2020/04/03. 10.1002/oby.22809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giacomelli A, Pezzati L, Conti F, Bernacchia D, Siano M, Oreni L, et al. Self-reported olfactory and taste disorders in SARS-CoV-2 patients: a cross-sectional study. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2020. Epub 2020/03/28. 10.1093/cid/ciaa330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hopkins C, Surda P, Kumar N. Presentation of new onset anosmia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Rhinology. 2020;58(3):295–8. Epub 2020/04/12. 10.4193/Rhin20.116 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ralli M, Di Stadio A, Greco A, de Vincentiis M, Polimeni A. Defining the burden of olfactory dysfunction in COVID-19 patients. European review for medical and pharmacological sciences. 2020;24(7):3440–1. Epub 2020/04/25. 10.26355/eurrev_202004_20797 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vaira LA, Salzano G, De Riu G. The importance of olfactory and gustatory disorders as early symptoms of coronavirus disease (COVID-19). The British journal of oral & maxillofacial surgery. 2020;58(5):615–6. Epub 2020/05/05. 10.1016/j.bjoms.2020.04.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Menni C, Sudre CH, Steves CJ, Ourselin S, Spector TD. Quantifying additional COVID-19 symptoms will save lives. Lancet (London, England). 2020. Epub 2020/06/09. 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)31281-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Menni C, Valdes AM, Freidin MB, Sudre CH, Nguyen LH, Drew DA, et al. Real-time tracking of self-reported symptoms to predict potential COVID-19. Nature medicine. 2020. Epub 2020/05/13. 10.1038/s41591-020-0916-2 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flaxman S, Mishra S, Gandy A, Unwin HJT, Mellan TA, Coupland H, et al. Estimating the effects of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in Europe. Nature. 2020. Epub 2020/06/09. 10.1038/s41586-020-2405-7 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jefferson T, Del Mar CB, Dooley L, Ferroni E, Al-Ansary LA, Bawazeer GA, et al. Physical interventions to interrupt or reduce the spread of respiratory viruses. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2011;2011(7):Cd006207 Epub 2011/07/08. 10.1002/14651858.CD006207.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arons MM, Hatfield KM, Reddy SC, Kimball A, James A, Jacobs JR, et al. Presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infections and Transmission in a Skilled Nursing Facility. The New England journal of medicine. 2020;382(22):2081–90. Epub 2020/04/25. 10.1056/NEJMoa2008457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hunter E, Price DA, Murphy E, van der Loeff IS, Baker KF, Lendrem D, et al. First experience of COVID-19 screening of health-care workers in England. Lancet (London, England). 2020;395(10234):e77–e8. Epub 2020/04/26. 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30970-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khalil A, Hill R, Ladhani S, Pattisson K, O'Brien P. COVID-19 screening of health-care workers in a London maternity hospital. The Lancet Infectious diseases. 2020. Epub 2020/05/22. 10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30403-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Metz TD. Is Universal Testing for Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Needed on All Labor and Delivery Units? Obstetrics and gynecology. 2020. Epub 2020/05/21. 10.1097/aog.0000000000003972 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poon LC, Yang H, Dumont S, Lee JCS, Copel JA, Danneels L, et al. ISUOG Interim Guidance on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) during pregnancy and puerperium: information for healthcare professionals—an update. Ultrasound in obstetrics & gynecology: the official journal of the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2020;55(6):848–62. Epub 2020/05/02. 10.1002/uog.22061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.New York City Department of Public Health. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) daily data summary. 2020.

- 29.Bahado-Singh R. Triage, L&D, Postpartum Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Medscape. 2020.

- 30.Control KCfD. Findings from investigation and analysis of re-positive cases. 2020.

- 31.Yang R, Gui X, Xiong Y. Comparison of Clinical Characteristics of Patients with Asymptomatic vs Symptomatic Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA network open. 2020;3(5):e2010182 Epub 2020/05/28. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.10182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chan KH, Poon LL, Cheng VC, Guan Y, Hung IF, Kong J, et al. Detection of SARS coronavirus in patients with suspected SARS. Emerging infectious diseases. 2004;10(2):294–9. Epub 2004/03/20. 10.3201/eid1002.030610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heatlh Emergencies Preparedness and Response WHO Global. Advice on the use of masks in the context of COVID-19. 2020:16. Epub June 5, 2020.

- 34.Joynt GM, Wu WK. Understanding COVID-19: what does viral RNA load really mean? The Lancet Infectious diseases. 2020;20(6):635–6. Epub 2020/04/01. 10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30237-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kucirka LM, Lauer SA, Laeyendecker O, Boon D, Lessler J. Variation in False-Negative Rate of Reverse Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction-Based SARS-CoV-2 Tests by Time Since Exposure. Annals of internal medicine. 2020. Epub 2020/05/19. 10.7326/m20-1495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wölfel R, Corman VM, Guggemos W, Seilmaier M, Zange S, Müller MA, et al. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature. 2020;581(7809):465–9. Epub 2020/04/03. 10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Joseph A. ‘We don’t actually have that answer yet’: WHO clarifies comments on asymptomatic spread of Covid-19. 2020.

- 38.La Scola B, Le Bideau M, Andreani J, Hoang VT, Grimaldier C, Colson P, et al. Viral RNA load as determined by cell culture as a management tool for discharge of SARS-CoV-2 patients from infectious disease wards. European journal of clinical microbiology & infectious diseases: official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology. 2020;39(6):1059–61. Epub 2020/04/29. 10.1007/s10096-020-03913-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kalafat E, Yaprak E, Cinar G, Varli B, Ozisik S, Uzun C, et al. Lung ultrasound and computed tomographic findings in pregnant woman with COVID-19. Ultrasound in obstetrics & gynecology: the official journal of the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2020;55(6):835–7. Epub 2020/04/07. 10.1002/uog.22034 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moro F, Buonsenso D, Moruzzi MC, Inchingolo R, Smargiassi A, Demi L, et al. How to perform lung ultrasound in pregnant women with suspected COVID-19. Ultrasound in obstetrics & gynecology: the official journal of the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2020;55(5):593–8. Epub 2020/03/25. 10.1002/uog.22028 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buonsenso D, Pata D, Chiaretti A. COVID-19 outbreak: less stethoscope, more ultrasound. The Lancet Respiratory medicine. 2020;8(5):e27 Epub 2020/03/24. 10.1016/s2213-2600(20)30120-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]