Abstract

Background:

Delirium is a highly prevalent and preventable neuropsychiatric condition with major health consequences. Thiamine deficiency is a well-established cause of delirium in those with chronic, severe alcoholism, but there remains an underappreciation of its significance in non-alcoholic populations, including patients with cancer. Treatment of suspected thiamine-related mental status changes with high dose intravenous (IV) thiamine has preliminary evidence for improving a variety of cognitive symptoms in oncology inpatient settings but has never been studied for the prevention of delirium in any population.

Objectives:

The primary objective of this clinical trial is to determine if high dose IV thiamine can prevent delirium in patients receiving allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) for treatment of cancer. Secondary objectives are to determine if thiamine status is predictive of delirium onset and if high dose IV thiamine can attenuate the deleterious impact of delirium on health-related quality of life (HRQOL), functional status, and long-term neuropsychiatric outcomes.

Methods:

In this phase II study, we are recruiting 60 patients undergoing allogeneic HSCT, randomizing them to treatment with high dose IV thiamine (n = 30) versus placebo (n = 30), and systematically evaluating all participants for delirium and related comorbidities. We use the Delirium Rating Scale to measure the severity and duration of delirium during hospitalization for HSCT. We obtain thiamine levels weekly during the transplantation hospitalization. We assess HRQOL, functional status, depression, post-traumatic stress symptoms, and cognitive function prior to and at one, three, and six months after transplantation.

Keywords: Wernicke’s encephalopathy, Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome, Delirium, Thiamine, Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, Cognitive impairment

1. Introduction

Delirium is a highly prevalent neuropsychiatric condition with major health consequences in the medically ill [1,2]. Patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) are at high risk for delirium because they often present with advanced disease and have completed one or more courses of chemotherapy. Patients receiving allogeneic transplantation may be at even higher risk due to the greater toxicity of their treatment, longer hospitalization, and higher complication rate compared to patients receiving autologous transplantation [3]. Given these multiple risk factors, delirium has been identified in as many as 73% of patients receiving HSCT [4,5]. Delirium in HSCT patients confers worse HRQOL, more severe distress, poor cognitive outcomes, and increased mortality [5,6].

Thiamine deficiency is a well-established cause of altered mental status, but this relationship has previously only been appreciated as a feature of Wernicke’s encephalopathy (WE). WE is a condition, classically described in chronic alcoholism, in which thiamine deficiency leads to a triad of clinical signs, including ophthalmoplegia, ataxia, and mental status changes. However, all three signs are identified in fewer than 20% of affected patients [7–9]. In the past 20 years, awareness of the potential for thiamine deficiency to lead to delirium without the other physical signs of WE has increased [10,11].

HSCT patients are vulnerable to thiamine deficiency through multiple cancer and treatment-mediated mechanisms [12]. For example, disease or treatment-related anorexia and vomiting limits absorption of thiamine from dietary sources [13]. Further, patients with hematologic malignancies and those who develop graft versus host disease (GVHD) after HSCT experience rapid cell turnover leading to increased thiamine metabolism. Finally, chemotherapies and calcineurin inhibitors typically administered during hospitalization for HSCT impair thiamine conversion to its biologically active form [13,14].

Treatment of suspected thiamine-related delirium with high dose IV thiamine, defined as at least 200 mg three times daily, demonstrates preliminary evidence for improving a variety of cognitive symptoms across oncologic and other medically ill populations [15–18]. Despite its widespread availability, low cost, and compelling rationale for treatment, high dose IV thiamine has never been studied for the prevention of delirium in any condition. Patients receiving HSCT have scheduled hospitalizations, are invariably exposed to neurotoxic agents (e.g. conditioning chemotherapy, immunosuppressants, opioids, benzodiazepines), commonly develop both delirium and thiamine deficiency over a multiple week hospitalization, and are closely monitored for several months after discharge. For these reasons, the HSCT population is ideal to conduct a clinical trial to investigate the efficacy of thiamine for delirium prevention and its long-term impact.

This randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial tests the efficacy of high dose IV thiamine for delirium prevention in patients receiving allogeneic HSCT. We hypothesize that the incidence of delirium in recipients of high dose IV thiamine will be lower than those who receive placebo. We further hypothesize that thiamine status will be predictive of subsequent delirium onset during HSCT hospitalization and that receipt of high dose IV thiamine will mitigate potential consequences of delirium, including depression, post-traumatic stress symptoms, impaired cognitive function, poor physical function, and adverse HRQOL [6,19–21].

2. Methods

2.1. Overview of study design

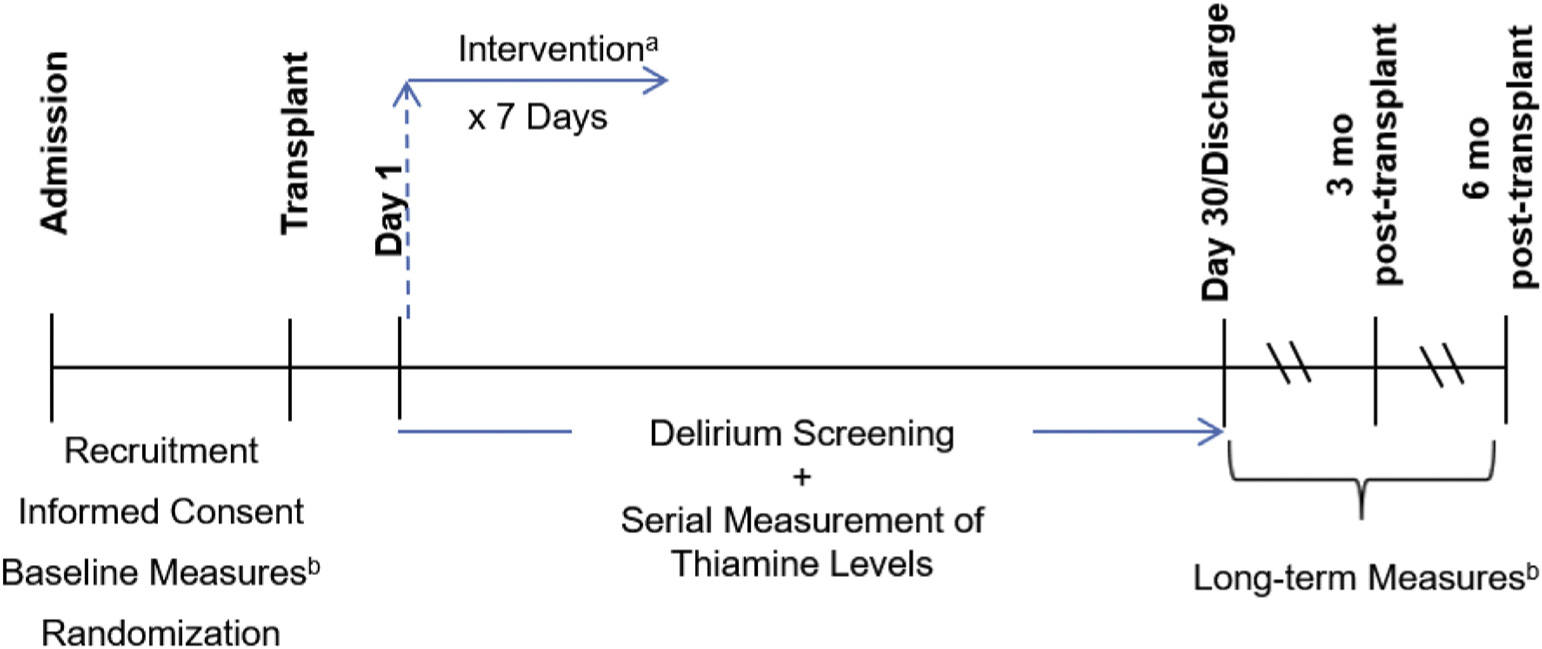

In this phase II, randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial we are recruiting 60 patients scheduled for allogeneic HSCT, randomizing them to treatment with high dose IV thiamine (n = 30) versus placebo (n = 30), and systematically evaluating all participants for delirium and related comorbidities (Fig. 1). We use the Delirium Rating Scale (DRS) to serially screen for delirium, defined as at least one DRS score > 12, from post-transplantation day 1 to post-transplantation day 30 or discharge, whichever comes first. When delirium occurs, we also use the DRS to measure the severity and duration of delirium. We obtain thiamine levels and other laboratory parameters associated with delirium at time of transplantation and continue to monitor thiamine levels weekly thereafter. We also monitor HRQOL, functional status, depression, post-traumatic stress symptoms, and cognitive function prior to transplantation and at one, three, and six months after transplantation to evaluate potential adverse outcomes after delirium and the potential for high dose IV thiamine to mitigate them.

Fig. 1.

Study Schematic. a. High dose IV thiamine (N = 30) vs. placebo (N = 30). b. Cognitive Function (Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA), HRQOL (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Bone Marrow Transplant, FACT-BMT), Depression (Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Depression, PROMIS-D), Post-traumatic Stress Symptoms (Post-Traumatic Stress Syndrome-14, PTSS-14), Functional Status (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status, ECOG).

2.2. Study aims and hypotheses

Aim 1. To compare delirium incidence, severity, and duration between recipients of high dose IV thiamine and placebo. We hypothesize that: (a) the incidence of delirium will be at least 40% in the control group and (b) the incidence of delirium will be lower in those participants who receive high dose IV thiamine compared to those who receive placebo.

Aim 2. To determine if thiamine status is predictive of subsequent delirium onset. We hypothesize that the severity of thiamine deficiency at one week after transplantation will be predictive of delirium during post-transplantation hospitalization.

Aim 3. To investigate the effects of high dose IV thiamine on long-term HRQOL, functional status, depression, post-traumatic stress symptoms, and cognitive function in patients who undergo HSCT. We hypothesize that patients who receive high dose IV thiamine will demonstrate (a) better HRQOL, (b) less depression, (c) fewer post-traumatic stress symptoms, (d) better cognitive function, and (e) better functional status compared to those who receive placebo at one, three, and six months after transplantation.

2.3. Study setting

This study is conducted at the University of North Carolina (UNC) Hospital, Chapel Hill, NC. Recruitment, baseline assessments, and delirium screening are performed on the UNC Bone Marrow Transplant (BMT) and Cellular Therapies inpatient unit. Longitudinal neuropsychiatric assessments are initiated in the inpatient setting and repeated after discharge during defined follow up timepoints in the UNC Cancer Hospital clinics.

2.4. Participant eligibility

Participants must meet all of the following inclusion criteria: 1.) admission to the UNC Hospital Bone Marrow Transplant Unit for allogeneic HSCT; 2.) at least 18 years of age; 3.) able to speak English; and 4.) able to provide informed consent. Exclusion criteria are: 1.) a history of an adverse reaction to IV thiamine; or 2.) pregnancy, confirmed by a negative pregnancy test within 30 days of study enrollment.

2.5. Randomization and intervention

Participants are randomized in a 1:1 ratio to the intervention or control arm. The statistician of record has designed a block randomization scheme, stratified by age (< 65 or ≥ 65) and baseline cognitive function (Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA, score > 25 or ≤ 25), both well-known risk factors for delirium. The UNC Investigational Drug Service assigns participants to each arm using the randomization list designed by the statistician. Participants in the intervention group receive thiamine 200 mg IV three times daily (TID) for seven days beginning on the day after transplantation (Table 1). Thiamine is procured by the UNC Investigational Drug Service from Fresenius Kabi USA, LLC. Participants in the control group receive 100 mL (equivalent volume to intervention) normal saline IV TID for seven days beginning on the day after transplantation. At any time, the Co-Principal Investigators (Co-PIs), primary medical providers, or other emergency personnel may request unblinding of a participant’s randomized treatment from the Investigational Drug Service. All participants in both study arms receive usual care for treatment and prevention of delirium. The proposed standardized management of delirium is detailed in the attached clinical protocol (Appendix A), which is provided to HSCT clinicians and psychiatric consultants to provide a framework to minimize variability in the management of delirium among study participants.

Table 1.

Regimen description

| Group | Agent | Dose | Route | Schedule |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Thiamine | 200 mg Thiamine HCL solution in 100 mL infusion bag of 0.9% sodium chloride | IV over 30 min (200 mL/h) | Post-transplantation days 1–7 three times daily |

| Control | Normal Saline | 100 mL of 0.9% | IV over 30 min (200 mL/h) | Post-transplantation days 1–7 three times daily |

Abbreviations: HCL – hydrochloride, IV – intravenous.

Any participant who receives either thiamine or placebo on this protocol are evaluated for toxicity according to the Time and Events Table (Table 2). Toxicity is assessed according to the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), version 4.0. All severe adverse effects (i.e. grades 3 or 4) are evaluated immediately by the Co-PIs and a decision is made about stopping the study medication.

Table 2.

Time and events table.

| Baseline (Pre-Transplantation) | Post-Transplantation Day 1 | Post-Transplantation Days 2–30 | F1 | F2 | F3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informed Consent | • | |||||

| Group Assignment | • | |||||

| Demographic Data Form | • | |||||

| Cancer History Form | • | |||||

| Delirium Risk Factor Form | • | • | • | |||

| Concurrent CNS Active Medication Tracking Form | • | • | • | |||

| Baseline Labsa | • | |||||

| Thiamine Levelsb | • | • | ||||

| DRSc | • | • | • | |||

| MoCAd | • | • | • | • | ||

| ECOGd | • | • | • | • | ||

| FACT-BMTd | • | • | • | • | ||

| PROMIS-Dd | • | • | • | • | ||

| PTSS-14d | • | • | • | • | ||

| Adverse Events Form | • | • |

Abbreviations: CNS – central nervous system, DRS – Delirium Rating Scale, MoCA – Montreal Cognitive Assessment, ECOG – Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, FACT-BMT – Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Bone Marrow Transplant, PROMIS – Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System, PTSS-14 – Post-traumatic Stress Syndrome-14.

Complete Blood Count (CBC), Comprehensive Metabolic Panel (CMP), Magnesium (Mg), Phosphorus (Phos).

Thiamine levels are drawn on post-transplant days 1, 8, 15, 22, and 29.

DRS is performed at baseline, on post-transplant day 1, and three times weekly thereafter.

FACT-BMT, PROMIS-D, PTSS-14, MoCA, and ECOG are performed at baseline (pre-transplant) and at one (F1), three (F2), and six months (F3) after transplant.

2.6. Measures

2.6.1. Delirium Rating Scale (DRS)

The DRS is a 10-item, clinician administered scale that rates the severity of delirium symptoms over a 24-hour period using all available information from the patient interview, mental status examination, medical history and tests, nursing observations, and family reports. To complete the DRS, a standardized interview is used (Appendix B). This standardized interview was originally developed by researchers at the University of Washington Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center [J.R. Fann, personal communication], trialed in patients with potential delirium seen on our Psychiatry Consultation-Liaison Service, and slight language modifications were made based on our clinical practice and to facilitate training and use by both experienced clinicians and clinical research assistants (CRAs). The maximum possible score is 32. A score of > 12 has been suggested to distinguish patients with delirium from patients with other neuropsychiatric disorders and is used as the cut-off for this study [22]. The CRAs or investigators assess for delirium three times weekly, beginning on the day after transplantation. If a participant is determined to have delirium, the frequency of delirium assessments increases to daily, Monday through Friday, until delirium resolves. The frequency of delirium screening employed in our study mirrors that in previous studies [4,5]. Because the DRS utilizes information from a 24-hour window, screening every other day is unlikely to miss incident delirium. The DRS assessment is not be performed if a patient becomes unevaluable due to an acute medical concern that precludes participation in the standardized interview (e.g. intubation, sedation, etc.). For participants who develop delirium during the inpatient phase, the DRS is repeated at one, three, and six months after transplantation. Details regarding the timing of the DRS, other clinician-administered and participant-reported assessments, toxicity monitoring, abstraction of data from the electronic medical record, and laboratory tests are outlined in the Time and Events table (Table 2).

2.6.2. Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)

The MoCA is a clinician-administered tool which has been wellvalidated in the literature, studied in a wide variety of patient populations, and permits assessment of cognitive impairment [23]. It is measured on a 30-point scale with lower scores indicating greater impairment. Scores ≤ 25 are considered clinically significant for cognitive impairment. For this study, we will utilize version 7.1. The MoCA and other longitudinal measures are performed at one, three, and six months after transplantation (timepoints coincident with regular clinical care follow-up) to assess long-term effects of delirium and our intervention.

2.6.3. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status

The ECOG performance scale is one of the most widely used measures of functional status [24]. It has high reliability and validity and is frequently used to estimate prognosis and treatment eligibility in oncology clinical trials [25]. ECOG performance status is scored on a 6 point scale with higher scores representing greater physical restriction due to illness.

2.6.4. Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Bone Marrow Transplant (FACT-BMT)

The FACT-BMT is a 47-item self-administered assessment which has been well validated in the literature and permits the measurement of HRQOL in patients receiving HSCT [26]. It asks individuals to rate questions related to physical, social/family, emotional, and functional well-being on a 5-point Likert Scale (0, not at all to 4, very much).

2.6.5. Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System – Depression

The National Institute of Health’s Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) contains a depression bank [27]. We will use the PROMIS Depression 8a short form. Scores for all PROMIS measures are reported on the T-score metric in which the mean = 50 and standard deviation (SD) = 10 are centered on the general population means. Higher scores represent greater degrees of mood symptoms.

2.6.6. Post-Traumatic Stress Syndrome 14 (PTSS-14)

The PTSS-14 is a 14-item self-administered assessment which has been well validated in the literature and permits the measurement of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms [28]. It has been used in a variety of populations, including assessment following a period of delirium, but originally developed to inquire about PTSD symptoms following time in intensive care units [20]. The language has been modified slightly for the purpose of our study to inquire about symptoms related to time spent in the BMT unit. Questions are on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1, never to 7, always) resulting in a total score between 14 and 98. Higher scores represent greater post-traumatic stress symptoms.

2.7. Thiamine levels

Thiamine levels are obtained weekly beginning on the day after transplantation (Table 2). Weekly thiamine level measurement both facilitates comparison to a prior study of serial measurements of vitamin and mineral levels in HSCT [12] and reflects the highest frequency that would be used clinically. Specifically, most hospitals do not have laboratories equipped to perform thiamine assays. Therefore, samples must be sent to referral facilities and results are not received for 4 to 6 days after samples are drawn. At the study defined timepoints, BMT nursing staff collect 10 mL whole blood at times coincident with lab draws for participants’ clinical care. Samples are sent to Mayo Medical Laboratories for liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry analysis of thiamine diphosphate levels. Results are returned to a pre-specified investigator not involved in the clinical assessments to preserve the integrity of the blind. All other study investigators and staff will only have access to these results after the study inpatient phase has completed.

2.8. Demographics, disease characteristics, medications, and other delirium risk factors

Age, gender, and race are obtained from the medical record. Years of education are provided by the participant. The following disease and transplantation characteristics are abstracted from the medical record: primary diagnosis, donor type (matched related donor, unrelated matched donor, haplotype), stem cell source (peripheral blood, cord blood, bone marrow), conditioning regimen (myeloablative vs. reduced intensity), exposure to total body irradiation. The Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research Disease Risk Index score (low, intermediate, high) and Hematopoietic Cell Transplant-Co-morbidity Index score are recorded to characterize disease severity and overall medical comorbidity, respectively, and to examine as potential delirium risk factors. Potentially deliriogenic medications, which act on the central nervous system (CNS), including antidepressants, anxiolytics, antipsychotics, antiepileptics, and antihistamines, are monitored throughout the transplantation hospitalization. Other relevant risk factors for delirium, including previous history of delirium, alcohol and substance use disorders, and conditions/findings concerning for structural brain abnormalities, including stroke, traumatic brain injury, seizures, and abnormal brain imaging, [29–32] are abstracted from medical records at baseline.

2.9. Data management

The study uses REDCap, a secure, password protected, and HIPAA compliant web-based data platform hosted by UNC for data capture and storage. This protected database is accessed and maintained by study personnel only. A complete time-stamped audit of all REDCap activity is maintained, adding to the security and fidelity of the data.

2.10. Data safety and monitoring

The study Co-PIs are responsible for continuous monitoring of patient safety during the trial. For non-serious adverse events, documentation begins from the first day of study treatment and continues through the 30-day follow-up period after treatment is discontinued. A description of the event, its severity or toxicity grade, onset and resolved dates, and the relationship to the study drug are documented in Case Report Forms. If the event meets the definition of being both serious and unexpected, it is also recorded on the MedWatch Form 3500A, as per 21 CFR 312.32, and forwarded to the FDA in accordance with 21 CFR 314.80 (for marketed drugs). The UNC Investigational Review Board (IRB) is notified of all unanticipated problems (serious, unexpected, and related). In accordance with these policies, an aggregated list of all serious adverse events is submitted to the UNC IRB annually at the time of study renewal.

Periodic review, at an interval of every six months to annually, by the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center (LCCC) Data Safety Monitoring Committee (DSMC), LCCC Protocol Review Committee (PRC), and Office of Human Research Ethics (OHRE) Biomedical IRB provides oversight of the Co-PIs’ continuous monitoring. For each DSMC review, summary information regarding toxicity and accrual pattern are prepared and submitted by the Co-PIs.

Though there are no formal a priori stopping rules for the study, in the event of a serious or unexpected adverse event or frequent occurrence of less serious unexpected or expected adverse events we would consult with the OHRE and DSMC as to whether the trial should continue.

2.11. Trial status

The trial was first posted to ClinicalTrials.gov on 8/24/2017 under identifier NCT03263442. The UNC LCCC PRC approved the study protocol on 7/5/2017. The UNC IRB approved the study protocol on 8/18/2017. Recruitment started in October 2017. The inpatient treatment phase was completed on 3/2/2020, and the follow-up assessment phase is anticipated to be complete by 9/1/2020.

2.12. Data analytic plan

2.12.1. Power and sample size

For the primary objective of comparing delirium incidence between groups, a two group chi-squared test with a 0.050 one-sided significance level has 80% power to detect the difference between a usual care proportion of 0.445 and an intervention proportion of 0.155 (odds ratio of 0.229) when the evaluable sample size in each group is 30. The anticipated incidence of delirium in the control group is based on 43–73% incidence of delirium during hospitalization for HSCT reported in the literature [4,5]. As this is the first study to evaluate the efficacy of thiamine as a prevention strategy for delirium, no data are available to generate an estimate of delirium incidence in the intervention group. Though there have been relatively few successful pharmacological delirium prevention trials, the odds ratio hypothesized for this study is in line with those that have demonstrated benefit [33–38].

Aim 1: To compare delirium incidence, severity, and duration between recipients of high dose IV thiamine and placebo during hospitalization for HSCT. The primary outcome measure is delirium incidence, defined as: DRS > 12. Secondary outcomes are differences in delirium duration (in days) and delirium severity, in which higher DRS scores suggest more severe delirium. A two group chi-squared test will be used to compare incidence of delirium in the intervention and control group. Maximum severity scores will be analyzed using two group t-tests, and time to delirium will be compared between groups using the Kaplan-Meier method. For those with delirium, two group t-tests will compare the duration of delirium between intervention and control groups; Kaplan-Meier methods may also be considered for time to delirium resolution. In order to be considered for the primary analysis, participants must: 1.) receive all seven days of the treatment; 2.) receive at least 17/21 (80%) scheduled study drug doses; and 3.) have delirium assessed at least weekly until the participant is found to be delirious, reaches 30 days post-transplant, or is discharged. Given the paucity of either RCTs involving parenteral IV thiamine or delirium intervention trials in HSCT to inform expected attrition, we will continue enrollment until 60 participants meet criteria for the primary efficacy analysis. Intention-to-treat analysis will also be performed and compared to the results of the per protocol analysis.

Aim 2: To determine if thiamine status is predictive of future delirium onset. We will examine the relationship between thiamine levels at the end of the seven day administration of thiamine and the development of delirium at any point during the 30 days post-transplantation or the post-transplantation hospitalization, whichever comes first. Analysis of thiamine levels at the end of the seven day administration of thiamine will provide information about a critical mediator of the relationship between our intervention and delirium (i.e. systemic thiamine deficiency). Further, given that delirium following HSCT most commonly occurs within the first two weeks after transplantation [4,5], we anticipate that the post-transplantation day 7 timepoint will be the most proximate measure of systemic thiamine levels prior to development of delirium. Participants who develop delirium prior to the end of the thiamine treatment will not be included in this analysis. We will examine the sensitivity and specificity of this relationship with receiver operating curves and attempt to find a cutoff for thiamine levels that is associated with the development of delirium.

Aim 3: To investigate the effects of high dose IV thiamine on long-term HRQOL, functional status, depression, post-traumatic stress symptoms, and cognitive function. Scores on FACT-BMT, PROMIS-D, PTSS-14, ECOG and MoCA will be compared between intervention and control groups. We will summarize scores on the FACT-BMT, PROMIS-D, PTSS-14, ECOG, and MoCA between the intervention and control groups at one, three, and six months post-transplantation. Longitudinal modeling will be performed to examine differences/changes over time.

Safety analyses. We will tabulate adverse events and serious adverse events by treatment and placebo within strata. We will include all adverse events which occurred at a rate of > 5% in any treatment. Any patient who receives at least one dose of study therapy on this protocol will be evaluable for toxicity.

3. Discussion

This is the first randomized controlled trial investigating the use of high dose IV thiamine for prevention of delirium in any population. In our study of patients undergoing allogeneic HSCT, we hypothesize that the incidence of delirium in participants who receive high dose IV thiamine will be lower than that in those who receive placebo. Additionally, we anticipate that the severity of thiamine deficiency one week after transplantation (at the end of the study drug delivery period) will predict the development of delirium during the post-transplantation hospitalization. Finally, we hypothesize that patients who receive high dose IV thiamine will have better long-term mood, cognition, functional status, and overall HRQOL.

Importantly, our study will expand the limited pharmacological strategies available to address delirium. Despite the substantial morbidity and mortality of delirium among hospitalized patients, there is no pharmacologic intervention approved for delirium prophylaxis. We have focused this study in patients receiving allogeneic HSCT, given the extraordinarily high risk for both thiamine deficiency and delirium in the post-transplantation period, but we anticipate that our results will prompt further investigation in other patient populations at risk for thiamine deficiency and delirium.

A wide spectrum of agents have been investigated for delirium, including alpha-2 agonists, acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, melatonin/melatonin-agonists, and dopamine antagonist antipsychotic agents [39]. Antipsychotics are the most well-studied and have shown beneficial effect in several studies [37,38,40–42]. However, a large and more recent randomized trial called the efficacy of antipsychotics under question [43]. Further, antipsychotics carry potential risks of QT prolongation and increased mortality in certain populations [44]. More compelling evidence exists for multi-component behavioral interventions [45–47]. This highlights the need for additional studies, such as the current one, which employ interventions with compelling scientific rationale, few potential adverse effects, and which could be incorporated into a multi-component delirium preventative intervention.

The findings of our study will also be highly relevant to investigators interested in nutritional care of medically ill populations. Patients undergoing HSCT experience a wide array of gastrointestinal complications stemming from their conditioning chemotherapy regimen, total body irradiation, and from acute and chronic GVHD. These complications increase risk for malnutrition, which may lead to adverse outcomes [48]. While parenteral and enteral nutrition is utilized in certain cases, very little is known about the specific nutritional needs of HSCT patients. The first study to evaluate vitamin and trace element levels during the acute phase of HSCT found not only universal deficiency of thiamine, but also deficiencies in folate, zinc, and vitamin C [12]. Vitamin C may be important in immune recovery in patients with hematologic malignancies receiving HSCT or other intensive chemotherapies [49] and has been shown in critically ill populations, including sepsis, trauma, and major burns, to mitigate inflammatory response, organ injury, and endothelial dysfunction [50]. As is the case with thiamine, very little is known about the potential benefits of high dose parenteral vitamin C supplementation. Our study will establish a protocol that can be adapted for identification and treatment of other vitamin and mineral deficiencies, and in doing so, begin to clarify the specific nutritional needs of various seriously ill populations.

There is currently inadequate evidence to guide specific dosing recommendations of parenteral thiamine. The longstanding recommendation for treatment of WE in the United States is 100 mg IV daily based on expert estimates, developed over 50 years ago, of what might constitute high doses [51]. There have been no clinical studies validating the efficacy of this dosing strategy, and the only randomized controlled trial investigating the dose response of thiamine on cognitive function revealed that subjects treated with the highest dose, 200 mg IM, performed better on a working memory task than subjects who received lower doses [15,16,51,52]. The most recent Cochrane review on the subject concluded that there was insufficient evidence to support a specific dose, frequency, route, or duration of thiamine for treatment or prophylaxis of WE and related syndromes [53]. The dosing employed in our study is informed by guidelines from the European Federation of Neurological Societies and Royal College of Physicians, each recommending at least 200 mg IV TID [54,55]. This has demonstrated efficacy in several case reports, including in oncology populations [15–18]. There are even fewer data to support a specific duration of high dose thiamine replacement. We use a seven day administration as a conservative estimate of how long treatment is needed to replete thiamine levels in deficient patients and/or improve mental status in those with WE [15,17,56–59]. Though we anticipate our study will be essential in validating the 200 mg IV TID regimen, future research will be needed to clarify the optimal strength and duration of IV thiamine for thiamine deficiency related mental status changes.

A related area requiring further investigation is optimal thiamine measurement. In our study, we send whole blood samples to Mayo Medical Laboratories for quantification of thiamine diphosphate, the biologically active form of thiamine, using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. This is the most widely accepted method of thiamine measurement, but has several limitations for widespread clinical utility and use in clinical trials. First, the assay requires highly specialized equipment and expertise only available at select facilities. Consequently, it can take close to one week from when samples are drawn until results are available for interpretation by the ordering provider, potentially after irreversible brain changes have occurred. Second, because thiamine levels are extracted from lysed red blood cells, it is not clear how measured levels represent thiamine concentration in the CNS. Though thiamine has been measured from cerebrospinal fluid, reference ranges have not been established nor have these levels demonstrated stronger association with clinical symptoms [60,61]. To that end, there remain substantial sensitivity and specificity issues in measuring thiamine from more complex biological matrices [62]. Availability of high-performance assays that can be used in real world samples, employing simpler detection methods, such as periplasmic binding approaches, are needed [62].

There are a few important limitations of our study to acknowledge. Although our eligibility criteria are broad as they relate to demographics and disease characteristics, we have restricted our sample to those receiving allogeneic HSCT. Therefore, while thiamine deficiency is common in many hospitalized cancer patients [11], our findings may not be generalizable to participants receiving autologous HSCT or to other oncology populations. Second, in patients with severe medical illness, such as those in our study population, delirium is often due to multiple determinants. We carefully collect data regarding many potential predisposing factors. However, these patients are at risk for delirium secondary to a multitude of additional factors, including those relatively unique during the post-HSCT period, such as Human Herpes Virus 6 encephalopathy and posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome [3]. The potential complexity of delirium in these patients informed our decision to deliver our intervention as prophylaxis and to evaluate its impact on attenuating the severity and duration of delirium, not just in decreasing incidence. Finally, due to the dearth of information regarding the efficacy of high dose IV thiamine for delirium prevention (or of any alternative pharmacotherapy for delirium prevention), it is possible that the sample size estimated for this study may not be adequate to detect differences between treatment groups. To estimate the maximal potential treatment effect and inform the appropriateness of high dose IV thiamine for a larger, multi-site delirium prevention trial, we have planned to evaluate our primary outcome using a per protocol analysis. It is important to acknowledge that compared to intention-to-treat analysis, which we will also perform, this provides a less accurate a reflection of the effect in real clinical practice.

3.1. Conclusion and future directions

Delirium and thiamine deficiency are extraordinarily common during hospitalization for HSCT, and there is emerging evidence to suggest that thiamine deficiency is an important cause of delirium in medically ill patients. In this double-blind, randomized controlled trial, we will examine the use of high dose IV thiamine to prevent delirium in participants receiving allogeneic HSCT. If our intervention is successful, the current study will inform a randomized trial of high dose IV thiamine for delirium prevention in other hospitalized populations and a multi-site trial in HSCT. In addition to evaluating the efficacy of our intervention for delirium, results from our study will provide important observational data about delirium and nutritional deficiency in HSCT that are currently lacking or outdated in the literature, including the current prevalence of delirium in HSCT, HSCT-specific delirium risk factors, and the temporal relationship between thiamine deficiency and delirium in this population. Our study will also clarify the prevalence of post-transplantation thiamine deficiency, illuminate the natural trajectory of thiamine levels over the transplantation hospitalization, and answer a fundamental, but not yet definitively addressed, question in any medically ill population: is thiamine deficiency corrected by high dose IV thiamine? Finally, we will examine longitudinal trajectories of several other important and understudied clinical outcomes. For example, very little is understood about post-traumatic stress symptoms secondary to cancer and its treatments, and even less is known in those undergoing HSCT. Similarly, though there have been a few studies investigating the longitudinal trajectory of cognitive function in HSCT patients [63–67], to our knowledge, only one has examined the impact of delirium on long-term cognition, and this study was limited to 30 patients with only one post-transplant assessment [66]. In summary, our study will generate novel data across numerous neuropsychiatric, psychosocial, and nutritional outcomes relevant to clinical trials addressing supportive care needs in oncology and other hospitalized patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the UNC Bone Marrow Transplant providers, nurses, and staff, as well as the UNC Investigational Drug Service and McLendon Laboratory, for their contributions to this study. The authors also thank Bradley Gaynes, MD, MPH (University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC, USA) for his critical comments during manuscript preparation and Michelle Manning, MPH (University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC, USA) for her invaluable study management support.

Funding

This work was supported by the Rising Tide Foundation for Clinical Cancer Research-Switzerland [grant number CCR-17-300], the National Institutes of Health- United States [grant numbers 5K07CA218167-03 and 5K12HD001441], and the University of North Carolina Cancer Research Fund - United States. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the NIH. The funders were not involved in the drafting of this manuscript.

Appendix A. Suggested management of delirium

-

Obtain further laboratory work-up

In all patients with delirium the following should be considered:

Blood chemistries: electrolytes, glucose, calcium, albumin, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, AST, ALT, bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, magnesium, phosphorus

Complete blood count (CBC)

Electrocardiogram

Chest X-ray

Measurement of arterial blood gases or oxygen saturation

Urinalysis

In patients with delirium the following should be considered if felt to be clinically indicated:

Urine culture and sensitivity

Urine drug screen

Blood cultures

Measurement of serum levels of medications (e.g., tacrolimus, cyclosporine, etc.)

Lumbar puncture

Brain computerized tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Electroencephalogram (EEG)

Folate, B12

Treat any reversible abnormalities identified in work-up

- Initiate environmental and supportive interventions

- Staff to open blinds every morning.

- Glasses, hearing aide, and patient’s own shoes to bedside. Make available to patients when possible and encourage use.

- Encourage po fluids when appropriate, keep fluids within reach.

- Out of bed to chair with meals.

- Staff to assess orientation to person, time and place every morning and as needed throughout the day.

- Recommend extended visitation hours with familiar family/friends as feasible.

- Staff to minimize disturbances at night. Turn off television when patient asleep or when not in use.

Consult Psychiatry for a.) behavioral disturbance and/or b.) Delirium Rating Score > 12

Appendix B. Delirium Interview

Ask Patient: (remember, time frame is past 24 h)

How have you been feeling the last 24 h?

Have you had any pain in the last 24 h? Rate your pain on a scale from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst).

-

Have you noticed changes in your feelings or mood since this time yesterday?

If yes, ask what type of changes they have noticed?

-

Have you noticed any changes in your energy since this time yesterday?

If yes, ask them to describe what they have noticed?

Do you feel like you are moving or talking slower or faster than you normally do?

Have you noticed any changes in your memory since this time yesterday?

-

Have you been feeling confused recently?

If confused, when did they feeling confused?

- I have a few questions to ask you about our current location and time:

-

What’s today’s date?If not relayed in entirety, prompt for year, month, and date in that order. If they get year wrong, don’t proceed to month or date. If month wrong, don’t proceed to date.

- What season is it?

-

What’s the day of the week?If needed, you can clarify name of day from Sunday to Monday

-

Where are we located right now?You want to know the name of the hospital and floor/unit. If they reply “hospital”, you can ask which one and prompt specifically for unit.

-

What city are we in? What state? What country?Ask in the listed order, proceed to next question regardless of accuracy of provided response

-

-

I’m going to read you three words, I want you to try and remember them. When I’m done reading them, I want you to repeat them back to me. I will ask you them again at the end of our conversation.

You can repeat once if requested.

Alternate: Monday: apple, table, car // Wednesday: carrot, glove, sparrow // Friday: chair, kite, green _____ number of words repeated correctly.

Only exact answers accepted. No hints, multiple choice, etc.

-

Now I’m going to read you some numbers, and I want you to repeat them back to me, just exactly as I say them to you.

Continue to the next step only if subject passes previous step. 582/_____, 6439/______, 42731/_______

-

Now I’m going to read you some more numbers, this time I want you to repeat them exactly BACKWARDS. For example, if I said “2–7” you would say “7–2”.

Continue to the next step only if subject passes previous step. 415/_____, 3279/______

-

How has your sleep been?

If patient mentions waking up in the middle of the night, ask if takes > 30 min to fall back asleep.

How many hours did you sleep last night?

Have you been having trouble staying awake during the day? How many hours did you sleep/nap during the day yesterday?________ Today________

When falling asleep or waking up, have you had difficulty knowing what is real or what is part of your dream?

-

Have seen or heard things that seem strange or that others might not see or hear?

Do you ever smell, feel or taste things that seem unusual or strange? Have you had trouble recognizing faces or objects?

-

Have you felt as if things aren’t real?

Have you felt like you’re outside of your body?

-

How has the staff been treating you?

Do you have any concerns about the treatment you’ve received?

Have you felt like people were trying to hurt you or are out to get you?

If yes, ask them to elaborate.

-

What were those three words that I asked you to remember? ________, ________, ________

Ask nurse: Make sure this is in private (i.e. not in front of patient or patient’s family). Explain that everything you are asking is over the last 24 h.

How’s the patient’s mood?

-

Have you noticed that the patient is confused?

If confused, when did the symptoms start?

-

Does the patient seem oriented?

Have you noticed the patient having difficulty recognizing people?

-

Any hallucinations or changes in patient’s ability to tell what is real and what is not real?

Does this happen other than when they’re waking up or falling asleep?

Do the patient’s symptoms change depending on the time of day?

Does the patient move or talk slower than usual?

-

How is the patient sleeping/napping?

Ask specific questions in #12 of patient interview if unable to get from patient.

Ask family:

Any changes in your (loved one)’s behavior? Have you noticed any unusual behavior?

How’s his/her mood?

-

Have you noticed that the he/she is confused?

If confused, when did this start?

-

Does he/she seem to know where he/she is and what the day/date/time is?

Have you noticed him/her having difficulty recognizing people?

-

Any hallucinations or changes in ability to tell what is real and what is not real?

Does this happen other than when he/she waking up or falling asleep?

Does he/she move or talk slower than usual?

Do any of the things we’ve talked about change depending on the time of day?

-

How is he/she sleeping/napping?

Ask specific questions from #12 of patient interview above if unable to get from patient.

Observe and make note of:

Level of awareness of environment

Delusions

Decreased or Increased Psychomotor Activity

4. Mood Lability

References

- [1].Siddiqi N, House AO, Holmes JD, Occurrence and outcome of delirium in medical in-patients: a systematic literature review, Age Ageing 35 (2006) 350–364. https://doi.org/afl005 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ely EW, Shintani A, Truman B, Speroff T, Gordon SM, Harrell FE Jr, Inouye SK, Bernard GR, Dittus RS, Delirium as a predictor of mortality in mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit, Jama 291 (2004) 1753–1762 10.1001/jama.291.14.1753 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Nakamura ZM, Nash RP, Quillen LJ, Richardson DR, McCall RC, Park EM, Psychiatric care in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, Psychosomatics (2019), 10.1016/j.psym.2019.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Fann JR, Roth-Roemer S, Burington BE, Katon WJ, Syrjala KL, Delirium in patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, Cancer 95 (2002) 1971–1981, 10.1002/cncr.10889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Beglinger LJ, Duff K, Van Der Heiden S, Parrott K, Langbehn D, Gingrich R, Incidence of delirium and associated mortality in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation patients, Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant 12 (9) (2006) 928–935, 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.05.009. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1083879106003776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Basinski JR, Alfano CM, Katon WJ, Syrjala KL, Fann JR, Impact of delirium on distress, health-related quality of life, and cognition 6 months and 1 year after hematopoietic cell transplant, Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant 16 (2010) 824–831, 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Harper C, The incidence of Wernicke’s encephalopathy in Australia–a neuropathological study of 131 cases, J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 46 (1983) 593–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Harper C, Wernicke’s encephalopathy: a more common disease than realised. A neuropathological study of 51 cases, J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 42 (1979) 226–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Lindboe CF, Løberg EM, Wernicke’s encephalopathy in non-alcoholics: an autopsy study, J. Neurol. Sci 90 (1989) 125–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Caine D, Halliday GM, Kril JJ, Harper CG, Operational criteria for the classification of chronic alcoholics: identification of Wernicke’s encephalopathy, J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 62 (1997) 51–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Isenberg-Grzeda E, Shen MJ, Alici Y, Wills J, Nelson C, Breitbart W, High rate of thiamine deficiency among inpatients with cancer referred for psychiatric consultation: results of a single site prevalence study, Psychooncology (2016), 10.1002/pon.4155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Nannya Y, Shinohara A, Ichikawa M, Kurokawa M, Serial profile of vitamins and trace elements during the acute phase of allogeneic stem cell transplantation, Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant 20 (2014) 430–434, 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.12.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Isenberg-Grzeda E, Kutner HE, Nicolson SE, Wernicke-Korsakoff-syndrome: under-recognized and under-treated, Psychosomatics 53 (2012) 507–516, 10.1016/j.psym.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Steinberg A, Gorman E, Tannenbaum J, Thiamine deficiency in stem cell transplant patients: a case series with an accompanying review of the literature, Clin. Lymphoma. Myeloma Leuk 14 (Suppl) (2014) S111–S113, 10.1016/j.clml.2014.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Isenberg-Grzeda E, Hsu AJ, Hatzoglou V, Nelso C, Breitbart W, Palliative treatment of thiamine-related encephalopathy (Wernicke’s encephalopathy) in cancer: A case series and review of the literature, Palliat. Support. Care 13 (2015) 1241–1249, 10.1017/S1478951514001163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Isenberg-Grzeda E, Alici Y, Hatzoglou V, Nelson C, Breitbart W, Nonalcoholic thiamine-related encephalopathy (Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome) among in patients with cancer: a series of 18 cases, Psychosomatics 57 (2016) 71–81, 10.1016/j.psym.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Davies SB, Joshua FF, Zagami AS, Wernicke’s encephalopathy in a non-alcoholic patient with a normal blood thiamine level, Med. J. Aust 194 (2011) 483–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Nishimoto A, Usery J, Winton JC, Twilla J, High-dose parenteral thiamine in treatment of Wernicke’s encephalopathy: case series and review of the literature, In Vivo 31 (2017) 121–124. https://doi.org/31/1/121 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Davydow DS, Symptoms of depression and anxiety after delirium, Psychosomatics 50 (2009) 309–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Drews T, Franck M, Radtke FM, Weiss B, Krampe H, Brockhaus WR, Winterer G, Spies CD, Postoperative delirium is an independent risk factor for posttraumatic stress disorder in the elderly patient: a prospective observational study, Eur. J. Anaesthesiol 32 (2015) 147–151, 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Inouye SK, Viscoli CM, Horwitz RI, Hurst LD, Tinetti ME, A predictive model for delirium in hospitalized elderly medical patients based on admission characteristics, Ann. Intern. Med 119 (1993) 474–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Trzepacz PT, Baker RW, Greenhouse J, A symptom rating scale for delirium, Psychiatry Res. 23 (1) (1988) 89–97, 10.1016/0165-1781(88)90037-6. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/0165178188900376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, Cummings JL, Chertkow H, The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment, J. Am. Geriatr. Soc 53 (2005) 695–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J, Davis TE, McFadden ET, Carbone PP, Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, Am. J. Clin. Oncol 5 (1982) 649–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Glare P, Sinclair C, Downing M, Stone P, Maltoni M, Vigano A, Predicting survival in patients with advanced disease, Eur. J. Cancer 44 (2008) 1146–1156 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].McQuellon RP, Russell GB, Cella DF, Craven BL, Brady M, Bonomi A, Hurd DD, Quality of life measurement in bone marrow transplantation: development of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Bone Marrow Transplant (FACT-BMT) scale, Bone Marrow Transplant. 19 (1997) 357–368 10.1038/sj.bmt.1700672 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Pilkonis PA, Choi SW, Reise SP, Stover AM, Riley WT, Cella D, Group PC, Item banks for measuring emotional distress from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS(R)): depression, anxiety, and anger, Assessment 18 (2011) 263–283. 10.1177/1073191111411667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Twigg E, Humphris G, Jones C, Bramwell R, Griffiths RD, Use of a screening questionnaire for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) on a sample of UK ICU patients, Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand 52 (2008) 202–208. https://doi.org/AAS1531 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Burns A, Gallagley A, Byrne J, Delirium J Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry (2004), 10.1136/jnnp.2003.023366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Edlund A, Lundström M, Brännström B, Bucht G, Gustafson Y, Delirium before and after operation for femoral neck fracture, J. Am. Geriatr. Soc (2001), 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Litaker D, Locala J, Franco K, Bronson DL, Tannous Z, Preoperative risk factors for postoperative delirium, Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry (2001), 10.1016/S0163-8343(01)00117-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Ouimet S, Kavanagh BP, Gottfried SB, Skrobik Y, Incidence, risk factors and consequences of ICU delirium, Intensive Care Med. (2007), 10.1007/s00134-006-0399-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Al-Aama T, Brymer C, Gutmanis I, Woolmore-Goodwin SM, Esbaugh J, Dasgupta M, Melatonin decreases delirium in elderly patients: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial, Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry (2011), 10.1002/gps.2582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Hatta K, Kishi Y, Wada K, Takeuchi T, Odawara T, Usui C, Nakamura H, Preventive effects of ramelteon on delirium: A randomized placebo-controlled trial, JAMA Psychiatry. (2014), 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.3320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Larsen KA, Kelly SE, Stern TA, Bode RH, Price LL, Hunter DJ, Gulczynski D, Bierbaum BE, Sweeney GA, Hoikala KA, Administration of olanzapine to prevent postoperative delirium in elderly joint-replacement patients: a randomized, controlled trial, Psychosomatics 51 (2010) 409–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Su X, Meng ZT, Wu XH, Cui F, Li HL, Wang DX, Zhu X, Zhu SN, Maze M, Ma D, Dexmedetomidine for prevention of delirium in elderly patients after noncardiac surgery: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, Lancet (2016), 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30580-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Wang W, Li HL, Wang DX, Zhu X, Li SL, Yao GQ, Chen KS, Gu XE, Zhu SN, Haloperidol prophylaxis decreases delirium incidence in elderly patients after noncardiac surgery: a randomized controlled trial, Crit. Care Med (2012), 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182376e4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Prakanrattana U, Prapaitrakool S, Efficacy of risperidone for prevention of postoperative delirium in cardiac surgery, Anaesth. Intensive Care (2007), . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Maldonado JR, Acute brain failure: pathophysiology, diagnosis, management, and sequelae of delirium, Crit. Care Clin (2017), 10.1016/j.ccc.2017.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kaneko T, Cai J, Ishikura T, Kobayashi M, Naka T, Kaibara N, Prophylactic consecutive administration of haloperidol can reduce the occurrence of postoperative delirium in gastrointestinal surgery, Yonago Acta Med. (1999). [Google Scholar]

- [41].Hakim SM, Othman AI, Naoum DO, Early treatment with risperidone for subsyndromal delirium after on-pump cardiac surgery in the elderly: a randomized trial, Anesthesiology (2012), 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31825153cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Larsen KA, Kelly SE, Stern TA, Bode RH, Price LL, Hunter DJ, Gulczynski D, Bierbaum BE, Sweeney GA, Hoikala KA, Cotter JJ, Potter AW, Administration of olanzapine to prevent postoperative delirium in elderly joint-replacement patients: a randomized, controlled trial, Psychosomatics (2010), 10.1176/appi.psy.51.5.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Girard TD, Exline MC, Carson SS, Hough CL, Rock P, Gong MN, Douglas IS, Malhotra A, Owens RL, Feinstein DJ, Khan B, Pisani MA, Hyzy RC, Schmidt GA, Schweickert WD, Hite RD, Bowton DL, Masica AL, Thompson JL, Chandrasekhar R, Pun BT, Strength C, Boehm LM, Jackson JC, Pandharipande PP, Brummel NE, Hughes CG, Patel MB, Stollings JL, Bernard GR, Dittus RS, Ely EW, Haloperidol and ziprasidone for treatment of delirium in critical illness, N. Engl. J. Med (2018), 10.1056/NEJMoa1808217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Ralph SJ, Espinet AJ, Increased all-cause mortality by antipsychotic drugs: updated review and meta-analysis in dementia and general mental health care, J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Reports (2018), 10.3233/adr-170042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Inouye SK, Bogardus ST, Charpentier PA, Leo-Summers L, Acampora D, Holford TR, Cooney LM, A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients, N. Engl. J. Med (1999), 10.1056/NEJM199903043400901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Martinez FT, Tobar C, Beddings CI, Vallejo G, Fuentes P, Preventing delirium in an acute hospital using a non-pharmacological intervention, Age Ageing 41 (2012) 629–634, 10.1093/ageing/afs060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Hshieh TT, Yue J, Oh E, Puelle M, Dowal S, Travison T, Inouye SK, Effectiveness of multicomponent nonpharmacological delirium interventions: a meta-analysis, JAMA Intern. Med (2015), 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Fuji S, Einsele H, Savani BN, Kapp M, Systematic nutritional support in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients, Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant 21 (2015) 1707–1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Huijskens MJAJ, Wodzig WKWH, Walczak M, Germeraad WTV, Bos GMJ, Ascorbic acid serum levels are reduced in patients with hematological malignancies, Results Immunol. 6 (2016) 8–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].BergerH.M. MM, Oudemans-van Straaten, Vitamin C supplementation in the critically ill patient, Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 18 (2015) 193–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Donnino MW, Vega J, Miller J, Walsh M, Myths and misconceptions of Wernicke’s encephalopathy: what every emergency physician should know, Ann. Emerg. Med 50 715–721 (2007) https://doi.org/S0196-0644(07)00207-7 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Ambrose ML, Bowden SC, Whelan G, Thiamin treatment and working memory function of alcohol-dependent people: preliminary findings, Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res 25 (2001) 112–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Day E, Bentham PW, Callaghan R, Kuruvilla T, George S, Thiamine for prevention and treatment of Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome in people who abuse alcohol, Cochrane Database Syst. Rev (7):CD0040 (2013) CD004033 10.1002/14651858.CD004033.pub3 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Thomson AD, Cook CC, Touquet R, Henry JA, Royal L, College of Physicians, The Royal College of Physicians report on alcohol: guidelines for managing Wernicke’s encephalopathy in the accident and Emergency Department, Alcohol Alcohol 37 (2002) 513–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Galvin R, Brathen G, Ivashynka A, Hillbom M, Tanasescu R, Leone MA, EFNS EFNS guidelines for diagnosis, therapy and prevention of Wernicke encephalopathy, Eur. J. Neurol 17 (2010) 1408–1418, 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Schoenenberger AW, Schoenenberger-Berzins R, der Maur CA, Suter PM, Vergopoulos A, Erne P, Thiamine supplementation in symptomatic chronic heart failure: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over pilot study, Clin. Res. Cardiol 101 (2012) 159–164, 10.1007/s00392-011-0376-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Donnino MW, Andersen LW, Chase M, Berg KM, Tidswell M, Giberson T, Wolfe R, Moskowitz A, Smithline H, Ngo L, Cocchi MN, Randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial of thiamine as a metabolic resuscitator in septic shock: a pilot study, Crit. Care Med (2016), 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Cefalo MG, De Ioris MA, Cacchione A, Longo D, Staccioli S, Arcioni F, Bernardi B, Mastronuzzi A, Wernicke encephalopathy in pediatric neuro-oncology: presentation of 2 cases and review of literature, J. Child Neurol (2014), 10.1177/0883073813510355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Lin S, Leppla IE, Yan H, Probert JM, Randhawa PA, Leoutsakos JMS, Probasco JC, Neufeld KJ, Prevalence and improvement of caine-positive Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome in psychiatric inpatient admissions, Psychosomatics (2019), 10.1016/j.psym.2019.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Molina JA, Jiménez-Jiménez FJ, Hernánz A, Fernández-Vivancos E, Medina S, De Bustos F, Gómez-Escalonilla C, Sayed Y, Cerebrospinal fluid levels of thiamine in patients with Alzheimer’s disease, J. Neural. Transm (2002), 10.1007/s007020200087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Ortigoza-Escobar JD, Molero-Luis M, Arias A, Oyarzabal A, Darín N, Serrano M, Garcia-Cazorla A, Tondo M, Hernandez M, Garcia-Villoria J, Casado M, Gort L, Mayr JA, Rodríguez-Pombo P, Ribes A, Artuch R, Pérez-Dueñas B, Free-thiamine is a potential biomarker of Thiamine transporter-2 deficiency: a treatable cause of Leigh syndrome, Brain. (2016), 10.1093/brain/awv342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Edwards KA, Tu-Maung N, Cheng K, Wang B, Baeumner AJ, Kraft CE, Thiamine assays—advances, challenges, and caveats, ChemistryOpen (2017), 10.1002/open.201600160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Friedman MA, Fernandez M, Wefel JS, Myszka KA, Champlin RE, Meyers CA, Course of cognitive decline in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a withinsubjects design, Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol (2009), 10.1093/arclin/acp060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Syrjala KL, Artherholt SB, Kurland BF, Langer SL, Roth-Roemer S, Elrod JB, Dikmen S, Prospective neurocognitive function over 5 years after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for cancer survivors compared with matched controls at 5 years, J. Clin. Oncol 29 (2011) 2397–2404, 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.9119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Hoogland AI, Nelson AM, Small BJ, Hyland KA, Gonzalez BD, Booth-Jones M, Anasetti C, Jacobsen PB, Jim HSL, The role of age in neurocognitive functioning among adult allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant recipients, Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant (2017), 10.1016/j.bbmt.2017.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Beglinger LJ, Duff K, van der Heiden S, Moser DJ, Bayless JD, Paulsen JS, Gingrich R, Neuropsychological and psychiatric functioning pre- and post- hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in adult cancer patients: a preliminary study, J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc 13 (2007) 172–177, 10.1017/S1355617707070208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Jim HSL, Syrjala KL, Rizzo D, Supportive care of hematopoietic cell transplant patients, Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant 18 (2012) S12–S16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]