Abstract

The prevalence of stress and distress has been increasing and being important public health issues; nevertheless, few studies have assessed the factors associated at the population level. This study identified factors associated and how they differentially influence stress and distress. A total of 35,105 individuals aged 19 years and older using nationally representative data from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2007–2012) were included in the study. Subjects were differentiated by gender and psychological state (no symptoms, stress, distress). The associations of socio-demographics, psychosocial factors, health behaviours, and chronic illness with psychological states were analysed by gender. Socio-demographics and psychosocial factors such as lower household income, lower education level, living alone or negative outcome of marriage, and unemployment were associated with distress in both genders. Male and female educated higher and with short sleep duration, male living alone and with higher household income, and female married and with a lower household income was associated with stress. A perceived body image of slim or fat was associated with distress and stress in both genders. Behavioural factors, such as smoking, higher alcohol consumption, and abnormal calorie intake, were associated with stress and distress in both genders, with the exception of alcohol consumption in distress and abnormal calorie intake in stress of male. Socio-economic deprivation and negative psychosocial and behavioural factors were differently associated with psychological distress or stress by gender. Intervention strategies for distress and stress should be specifically tailored regarding these differences.

Subject terms: Health care, Risk factors

Introduction

Psychological health is unquestionably an important issue, given that people with psychological symptoms accounts large proportion of the population worldwide. 75 percent of Americans report experiencing at least one symptom of stress in the past month and around one-fourth American said stress has a strong impact on their physical or mental health1. Four out of 10 UK adults feel stressed most days, and one-third Australians experienced depressive symptoms2. Koreans who feel their life is substantially or extremely stressful accounted for 27.9% and the prevalence of depression was 5.6% in the same population3. Consistent with these trends, the terms ‘psychological stress’ and ‘psychological distress’, which are defined as having perceived pressure from daily life but coping with it and stress exceeding persons’ ability to manage it, respectively, are increasingly used in social, academic, and employment settings4,5.

Several factors have been investigated with respect to their role in psychological stress and distress: socio-demographics, health behaviours, and the psychosocial environment. Possible health behaviours associated with psychological stress and distress include tobacco use, alcohol consumption, physical inactivity, dietary intake, and weight change6–8. Psychosocial environmental factors that have been investigated include marital status, living alone, employment status, shift work, working hours, weight change, body mass index (BMI), perceived body image (PBI), and skipping meals7,9–16. Gender, age, household income, education, and occupation are sociodemographic factors that have been investigated6,7. Clinical illness such as pulmonary disease, asthma, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dementia, mental disability, cancer, and degenerative diseases, has been also studied as a strong predictors of psychological stress and distress in some of previous studies focusing on the association of a specific chronic illness17.

However, the associations found between the aforementioned factors and psychological stress and distress have been inconsistent due to differences in study design, target population, and other potential factors included in analyses, and there are lack of studies to include potential factors associated with psychological stress and distress, comprehensively.

Therefore, an exploratory study, which comprehensively investigate sociodemographic, behavioural, psychosocial, and chronic illness factors associated with psychological stress and distress, and examine how those factors may differentially influence stress and distress, has been done using nationally representative population-based data from Korea.

Data and methods

Study design and participants

The study design was cross-sectional, using data from Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES), which is a national survey designed and conducted by the Ministry of Health and Welfare and the Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (https://knhanes.cdc.go.kr/knhanes/index.do) with the national representative sample through the multi-stage probability sampling method and structured and validated questionnaire. Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Institutional Review Board approved the protocols of the KNHANES. In this study, we used a dataset of the KNHANES that is open to the public. The Fourth (2007–2009) and Fifth (2010–2012) KNHANES included 50,405 participants. For the current study, subjects were excluded who were under 19 years of age, or who had incomplete information on psychological state. The final study population comprised 35,105 subjects—14,879 males and 20,226 females.

Data and measurements

Psychological state was defined by the answers to three questions: Q1, ‘How much do you feel stress in your daily life?’ (response to the question is ‘minimally stressful’ or ‘moderately stressful’ or ‘substantially stressful’ or ‘extremely stressful’); Q2, ‘Have you ever experienced suicidal ideation within the last year?’ (response to the question is ‘yes’ or ‘no’); and Q3, ‘Have you ever suffered from feeling down, depressed, or hopeless for two consecutive weeks or longer during the last year?’ (response to the question is ‘yes’ or ‘no’).

Subjects who responded to question 1 that their lives were ‘substantially stressful’ or ‘extremely stressful’ but responded ‘no’ to both question 2 and 3 were categorized as experiencing psychological stress alone, which means having more than substantial level of pressure from daily life but coping with it. Without regard to if they have psychological stress or not, subjects who concurred with questions 2 or 3 were categorized as experiencing psychological distress, which could be defined as having stress exceeding persons’ ability to manage it. Subjects who did not report any daily stress, melancholy, or suicidal ideation were categorized as the no symptom group.

Data obtained from the survey questionnaire, which has been validated by Korean CDC for National Survey, and anthropometric measurements included the following: sociodemographic factors such as gender (male, female), age (19–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50 years or older), residence area (country, city, metropolitan city), education level (middle school or less, high school, college or more), and household income (lowest quartile, second quartile, third quartile, highest quartile); psychosocial factors such as marital status (single; married; bereaved, divorced, or separated), living alone without family member (yes, no), employment status (employed, employed, retired, students, and subjects who do not need an employment; unemployed, unemployed, between jobs, taking leave of absence), PBI (slim, normal, fat), BMI (low weight, < 18.5 kg/m2; normal, ≥ 18.5 kg/m2 and < 25 kg/m2; obese: ≥ 25 kg/m2)18, and sleep duration (short, less than 6 h per day; optimal, 6–8 h per day; long, more than 8 h per day); behavioural factors such as smoking status (never a smoker, former smoker, current smoker), amount of alcohol consumption per occasion (0 g, 0–24 g, 24–72 g, over 72 g of absolute alcohol concentration), physical activity (active, engaging in moderate or vigorous physical activity; inactive), and calorie intake (low, consuming lower than their basal metabolic rate (BMR); normal, consuming over their BMR and lower than 1.2 times their BMR; excessive, consuming more than 1.2 times their BMR)19,20; and physiological condition such as menstruation (yes, no) and clinical illness (yes, having illness or diseases such as (hypertension, dyslipidemia, stroke, myocardial infarction/angina pectoris, degenerative arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, tuberculosis, asthma, diabetes mellitus, thyroid disease, atopic dermatitis, renal failure, hepatitis B and C, liver cirrhosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancer, and degenerative diseases; no).

The following variables were considered in the initial analysis to regard predictors of psychological stress and distress, comprehensively, based on previous knowledge, but later excluded due to no significant association in the univariate analysis or a significant correlation with other variables included in the final analysis: occupation, frequency of alcohol consumption, diagnosis of depression, EQ-5D index (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression), distorted body image, trial to manage weight, weight change within a year, number of meals with their family in a day, frequency of dining out, skipping meals for last 2 days, working hours, and shift work.

Statistical analysis

Chi-square tests were used to analyse frequencies of the distribution of baseline characteristics of the study participants and the effect size on the difference of the frequency distribution in each variable is measured. Prevalence ratio and associations between factors and psychological states including stress and distress were evaluated using multivariate logistic regression analysis adjusted with age only and all variables as appropriate21. p-for trend test has been done to identify the dose response relationship. All statistical tests were two-tailed with a 5% level of significance, and obtained using SAS version 9.3.

Declaration of Helsinki

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Ethics approval

All KNHANES surveys were conducted with informed consent of participants by Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) and the Institutional Review Board of KCDC approved the protocols of the KNHANES. In this study, we used a dataset of the KNHANES that is open to the public for retrospective analysis did not include personally identifiable information.

Results

Frequency distribution of potential factors by psychological status

Compared with the no symptom and psychological stress alone groups, both male and female subjects with psychological distress were more likely to be older, live in country, have lower education level, have lower household income, have negative marriage outcome (bereaved, divorced, or separated), live alone without family members, be unemployed, have a slim PBI, have shorter or longer sleep duration, have ever been smokers, be non-drinkers, have a low calorie intake, and have chronic illness. The distribution of these factors was inversed among subjects with psychological stress alone when they were compared with the no symptom group. Male subjects with psychological distress also tended to have low BMI, while female subjects with psychological distress tended to have high BMI, to be physically active, and to be undergoing menopause (Table 1).

Table 1.

Difference on distribution of sociodemographic, psychosocial, and behavioral factors in study subjects by gender and psychological status.

| Variables | Male | Female | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | No symptom | Psychological stress | P-valuea | Psychological distress | P-valueb | Total | No symptom | Psychological stress | P-valuea | Psychological distress | P-valueb | |||||||||

| n = 14,879 | % | n = 10,089 | % | n = 2,379 | % | n = 2,411 | % | n = 20,226 | % | n = 11,628 | % | n = 2,880 | % | n = 5,718 | % | |||||

| Age (years) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||||||||||||

| 19–29 | 1,840 | 12.9 | 1,264 | 12.5 | 346 | 14.5 | 230 | 9.5 | 2,526 | 11.4 | 1,312 | 11.3 | 548 | 19.0 | 666 | 11.6 | ||||

| 30–39 | 2,800 | 19.6 | 1,709 | 16.9 | 730 | 30.7 | 361 | 15.0 | 3,984 | 18.8 | 2,409 | 20.7 | 731 | 25.4 | 844 | 14.8 | ||||

| 40–49 | 2,852 | 19.7 | 1,849 | 18.3 | 608 | 25.6 | 395 | 16.4 | 3,708 | 18.3 | 2,305 | 19.8 | 526 | 18.3 | 877 | 15.3 | ||||

| ≥ 50 | 7,387 | 47.8 | 5,267 | 52.2 | 695 | 29.2 | 1,425 | 59.1 | 10,008 | 51.5 | 5,602 | 48.2 | 1,075 | 37.3 | 3,331 | 58.3 | ||||

| Region | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | 0.1303 | < 0.0001 | ||||||||||||||||

| Metropolitan city | 6,585 | 45.0 | 4,478 | 44.4 | 1,133 | 47.6 | 974 | 40.4 | 9,091 | 44.8 | 5,320 | 45.8 | 1,316 | 45.7 | 2,455 | 42.9 | ||||

| Urban | 5,017 | 33.8 | 3,346 | 33.2 | 870 | 36.6 | 801 | 33.2 | 6,839 | 33.6 | 3,924 | 33.7 | 1,016 | 35.3 | 1,899 | 33.2 | ||||

| Rural | 3,277 | 21.2 | 2,265 | 22.5 | 376 | 15.8 | 636 | 26.4 | 4,296 | 21.6 | 2,384 | 20.5 | 548 | 19.0 | 1,364 | 23.9 | ||||

| Education level | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||||||||||||

| Middle school or less | 4,619 | 28.5 | 3,128 | 31.1 | 416 | 17.5 | 1,075 | 44.8 | 8,836 | 45.6 | 4,728 | 40.7 | 938 | 32.6 | 3,170 | 55.6 | ||||

| High school | 5,376 | 37.0 | 3,730 | 37.1 | 873 | 36.8 | 773 | 32.2 | 6,466 | 31.7 | 3,943 | 34.0 | 975 | 33.9 | 1,548 | 27.1 | ||||

| College or more | 4,843 | 34.5 | 3,208 | 31.9 | 1,085 | 45.7 | 550 | 22.9 | 4,885 | 22.7 | 2,939 | 25.3 | 961 | 33.4 | 985 | 17.3 | ||||

| Household income (Quartile) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | 0.1544 | < 0.0001 | ||||||||||||||||

| Lowest | 2,721 | 16.6 | 1,782 | 18.0 | 252 | 10.8 | 687 | 29.1 | 4,330 | 22.4 | 2,078 | 18.2 | 512 | 18.1 | 1,740 | 31.1 | ||||

| Second | 3,716 | 25.0 | 2,523 | 25.4 | 548 | 23.4 | 645 | 27.3 | 5,035 | 25.2 | 2,833 | 24.8 | 748 | 26.5 | 1,454 | 26.0 | ||||

| Third | 4,063 | 28.8 | 2,805 | 28.2 | 731 | 31.2 | 527 | 22.3 | 5,228 | 26.4 | 3,191 | 27.9 | 738 | 26.1 | 1,299 | 23.2 | ||||

| Highest | 4,129 | 29.6 | 2,816 | 28.4 | 813 | 34.7 | 500 | 21.2 | 5,260 | 26.0 | 3,332 | 29.1 | 828 | 29.3 | 1,100 | 19.7 | ||||

| Marital status | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < .0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||||||||||||

| Single | 2,411 | 15.9 | 1,600 | 15.9 | 423 | 17.9 | 388 | 16.1 | 2,369 | 10.8 | 1,235 | 10.6 | 498 | 17.3 | 636 | 11.2 | ||||

| Married | 11,640 | 79.4 | 7,984 | 79.4 | 1,878 | 79.3 | 1,778 | 74.0 | 13,820 | 68.3 | 8,324 | 71.8 | 2,012 | 70.0 | 3,484 | 61.1 | ||||

| Bereaved/divorced/separated | 774 | 4.7 | 468 | 4.7 | 68 | 2.9 | 238 | 9.9 | 3,985 | 20.9 | 2,038 | 17.6 | 366 | 12.7 | 1,581 | 27.7 | ||||

| Living alone without family members | 0.0031 | < 0.0001 | 0.0014 | < 0.0001 | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 633 | 3.6 | 390 | 3.9 | 62 | 2.6 | 181 | 7.5 | 1795 | 9.4 | 897 | 7.7 | 172 | 6.0 | 726 | 12.7 | ||||

| No | 14,241 | 96.4 | 9,697 | 96.1 | 2,316 | 97.4 | 2,228 | 92.5 | 18,431 | 90.6 | 10,731 | 92.3 | 2,708 | 94.0 | 4,992 | 87.3 | ||||

| Employment status | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | 0.105 | < 0.0001 | ||||||||||||||||

| Employed | 12,834 | 88.8 | 8,829 | 87.9 | 2,189 | 92.4 | 1,816 | 76.0 | 12,723 | 62.7 | 7,588 | 65.7 | 1,925 | 67.3 | 3,210 | 56.7 | ||||

| Unemployed | 1967 | 11.2 | 1,214 | 12.1 | 181 | 7.6 | 572 | 24.0 | 7,361 | 37.3 | 3,969 | 34.3 | 937 | 32.7 | 2,455 | 43.3 | ||||

| PBI | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | |||||||||||||||||

| Slim | 3,265 | 20.9 | 2,100 | 20.8 | 503 | 21.2 | 662 | 27.5 | 2,984 | 14.7 | 1,504 | 12.9 | 428 | 14.9 | < .0001 | 1,052 | 18.4 | |||

| Normal | 6,160 | 41.9 | 4,413 | 43.7 | 810 | 34.1 | 937 | 38.9 | 8,148 | 40.8 | 4,956 | 42.6 | 1,077 | 37.4 | 2,115 | 37.0 | ||||

| Fat | 5,450 | 37.2 | 3,574 | 35.4 | 1,065 | 44.8 | 811 | 33.7 | 9,093 | 44.5 | 5,167 | 44.4 | 1,375 | 47.7 | 2,551 | 44.6 | ||||

| BMI | 0.0001 | 0.0002 | < .0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||||||||||||

| Low weight | 487 | 3.0 | 317 | 3.2 | 59 | 2.5 | 111 | 4.6 | 1,109 | 5.3 | 581 | 5.1 | 211 | 7.4 | 317 | 5.6 | ||||

| Normal | 9,136 | 61.5 | 6,238 | 62.2 | 1,381 | 58.4 | 1,517 | 63.4 | 12,955 | 64.9 | 7,548 | 66.0 | 1,862 | 65.4 | 3,545 | 62.7 | ||||

| Obesity | 5,166 | 35.5 | 3,476 | 34.6 | 926 | 39.1 | 764 | 31.9 | 5,878 | 29.8 | 3,307 | 28.9 | 776 | 27.2 | 1,795 | 31.7 | ||||

| Sleep duration | 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < .0001 | |||||||||||||||||

| Short | 2,019 | 12.3 | 1,214 | 12.0 | 325 | 13.7 | 480 | 19.9 | 3,601 | 17.6 | 1,679 | 14.4 | 551 | 19.1 | 1,371 | 24.0 | < 0.0001 | |||

| Optimal | 11,747 | 80.7 | 8,131 | 80.6 | 1,931 | 81.2 | 1,685 | 69.9 | 14,895 | 73.7 | 8,982 | 77.2 | 2,117 | 73.5 | 3,796 | 66.4 | ||||

| Long | 1,113 | 7.0 | 744 | 7.4 | 123 | 5.2 | 246 | 10.2 | 1,730 | 8.8 | 967 | 8.3 | 212 | 7.4 | 551 | 9.6 | ||||

| Smoking status | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||||||||||||

| Never | 3,217 | 22.2 | 2,295 | 22.8 | 476 | 20.0 | 446 | 18.5 | 18,303 | 90.7 | 10,807 | 93.0 | 2,571 | 89.3 | 4,925 | 86.2 | ||||

| Former | 5,393 | 36.6 | 3,872 | 38.4 | 689 | 29.0 | 832 | 34.5 | 799 | 3.9 | 373 | 3.2 | 130 | 4.5 | 296 | 5.2 | ||||

| Current | 6,262 | 41.2 | 3,918 | 38.8 | 1,212 | 51.0 | 1,132 | 47.0 | 1,114 | 5.4 | 444 | 3.8 | 177 | 6.2 | 493 | 8.6 | ||||

| Alcohol consumption | < 0.0001 | 0.0126 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 g | 2,523 | 16.4 | 1,796 | 17.8 | 243 | 10.2 | 484 | 20.1 | 7,760 | 39.5 | 4,450 | 38.3 | 917 | 31.8 | 2,393 | 41.9 | ||||

| 0–24 g | 2,277 | 15.3 | 1,616 | 16.0 | 288 | 12.1 | 373 | 15.5 | 6,868 | 33.9 | 4,168 | 35.8 | 998 | 34.7 | 1,702 | 29.8 | ||||

| 24–72 g | 4,915 | 33.5 | 3,389 | 33.6 | 782 | 32.9 | 744 | 30.9 | 4,354 | 20.9 | 2,459 | 21.2 | 724 | 25.1 | 1,171 | 20.5 | ||||

| > 72 g | 5,155 | 34.9 | 3,283 | 32.6 | 1,064 | 44.8 | 808 | 33.5 | 1,237 | 5.7 | 546 | 4.7 | 241 | 8.4 | 450 | 7.9 | ||||

| Physical activity | 0.2722 | 0.0022 | 0.0015 | |||||||||||||||||

| Inactive | 11,208 | 74.9 | 7,533 | 74.7 | 1,802 | 75.8 | 1,873 | 77.7 | 16,217 | 80.3 | 9,412 | 81.0 | 2,295 | 79.7 | 0.1350 | 4,510 | 78.9 | |||

| Active | 3,660 | 25.1 | 2,548 | 25.3 | 575 | 24.2 | 537 | 22.3 | 3,999 | 19.7 | 2,212 | 19.0 | 583 | 20.3 | 1,204 | 21.1 | ||||

| Calorie intake | 0.3373 | 0.0152 | 0.0024 | < 0.0001 | ||||||||||||||||

| Low | 2,065 | 16.3 | 1,381 | 16.2 | 309 | 16.9 | 375 | 18.8 | 4,918 | 26.4 | 2,618 | 24.3 | 710 | 27.3 | 1,590 | 30.6 | ||||

| Normal | 1,896 | 15.5 | 1,342 | 15.7 | 264 | 14.4 | 290 | 14.5 | 3,338 | 18.2 | 2,002 | 18.6 | 435 | 16.8 | 901 | 17.3 | ||||

| Excess | 8,385 | 68.1 | 5,798 | 68.0 | 1,254 | 68.6 | 1,333 | 66.7 | 10,301 | 55.4 | 6,142 | 57.1 | 1,452 | 55.9 | 2,707 | 52.1 | ||||

| Menstruation | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Yes | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 9,256 | 46.0 | 5,485 | 49.1 | 1,631 | 59.8 | 2,140 | 39.5 | ||

| No | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 10,048 | 54.0 | 5,675 | 50.9 | 1,098 | 40.2 | 3,275 | 60.5 | ||||

| Chronic illness | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | 0.0003 | < 0.0001 | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 6,509 | 42.1 | 4,402 | 43.6 | 845 | 35.5 | 1,262 | 52.3 | 9,627 | 48.7 | 5,212 | 44.8 | 1,184 | 41.1 | 3,231 | 56.5 | ||||

| No | 8,370 | 57.9 | 5,687 | 56.4 | 1,534 | 64.5 | 1,149 | 47.7 | 10,599 | 51.3 | 6,416 | 55.2 | 1,696 | 58.9 | 2,487 | 43.5 | ||||

aChi-square test for no symptom vs. psychological stress alone.

bChi-square test for no symptom vs. psychological distress.

The association of sociodemographic, psychological, and behavioural factors with psychological stress alone and distress

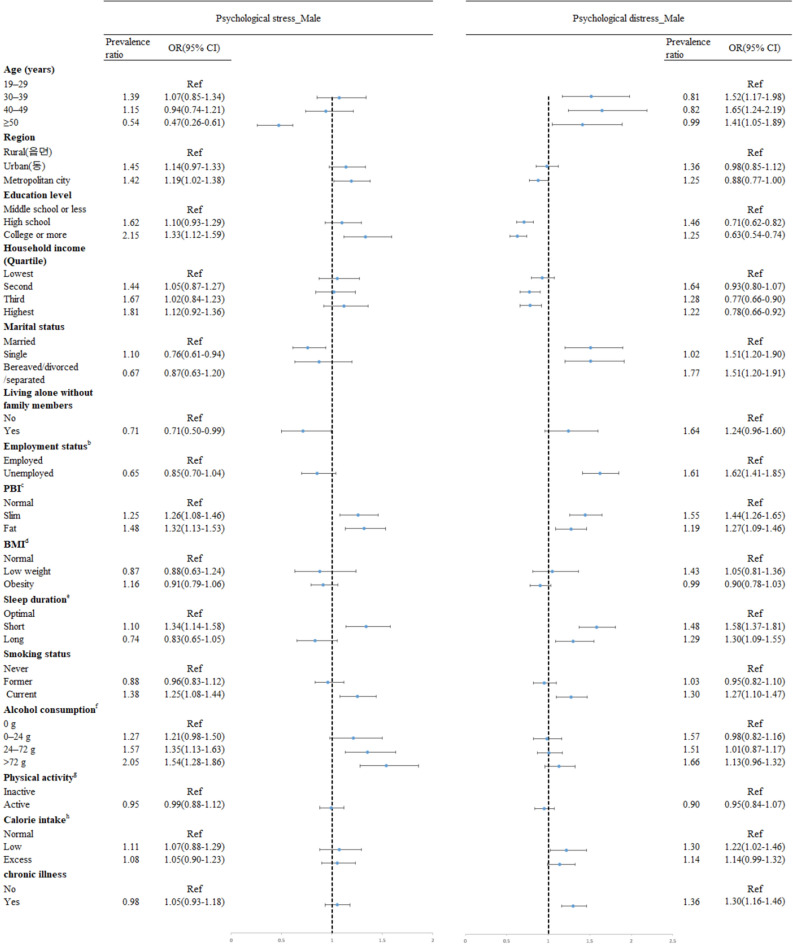

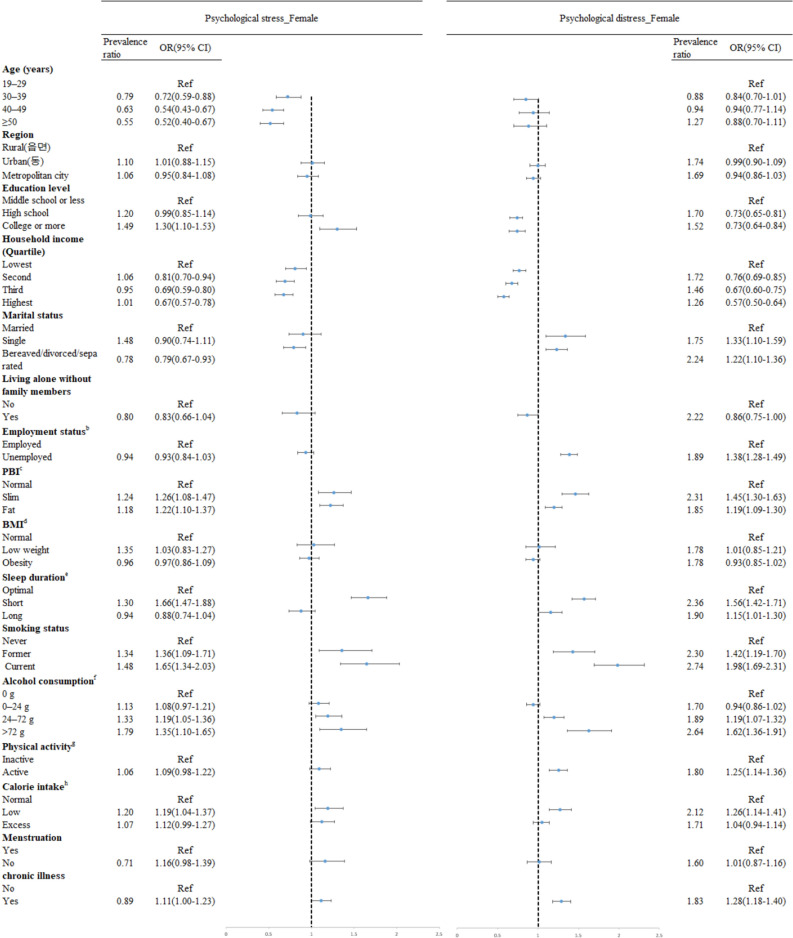

The current findings show the associations between various factors and psychological stress and psychological distress (Figs. 1, 2). After adjustment for all variable as appropriates, increased prevalence of psychological stress was shown in both gender being younger, more educated (odds ratio, OR 1.33, 95% confidence interval, CI 1.12–1.59 in male educated college or more; OR 1.30; 95% CI 1.10–1.53 female educated college or more), having slim or fat PBI (OR 1.32; 95% CI 1.13–1.53 in male with fat PBI; OR 1.22; 95% CI 1.10–1.37 in female with fat PBI), having short sleep duration (OR 1.34; 95% CI 1.14–1.58 in male, OR 1.66; 95% CI 1.47–1.88 in female), being current smokers (OR 1.25; 95% CI 1.08–1.44 in male, OR 1.65; 95% CI 1.34–2.03 in female), drinking higher amount of alcohol (OR 1.54; 95% CI 1.28–1.86 in male drinking more than 72 g/day; OR 1.35; 95% CI 1.10–1.65 in female drinking more than 72 g/day) Living in metropolitan city and living with family members were factors associated with increased prevalence of psychological stress in male only, while married, having a low calorie intake, and having chronic illness were in female only. Having higher household income decreased the odds of psychological stress among female.

Figure 1.

Forest plot showing odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for psychological stress and distress among male.

Figure 2.

Forest plot showing odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for psychological stress and distress among female.

Being different from the results in factors associated with psychological stress, for both males and females, relatively higher level of education (OR 0.63; 95% CI 0.54–0.74 in male educated college or more, OR 0.73; 95% CI 0.64–0.84 in female educated college or more) and household income (OR 0.78; 95% CI 0.66–0.92 in male at the highest income group, OR 0.57; 95% CI 0.50–0.64 in female at the highest income group) decreased the odds of psychological distress. Negative marriage outcome such as bereaved, divorced, and separated (OR 1.51; 95% CI 1.20–1.91 in male; OR 1.22; 95% CI 1.10–1.36 in female) and being single (OR 1.51; 95% CI 1.20–1.90 in male; OR 1.33; 95% CI 1.10–1.59 in female), unemployed (OR 1.62; 95% CI 1.41–1.85 in male; OR 1.38; 95% CI 1.28–1.49 in female), and having chronic illness (OR 1.30; 95% CI 1.16–1.46 in male; OR 1.28; 95% CI 1.18–1.40 in female) were associated with having psychological distress, even though these were not significantly associated with psychological stress. Having either slim or fat PBI, having either short or long sleep duration, being current smokers, having a low calorie intake were associated with increased prevalence of psychological distress, too, for both male and female. Having more amounts of alcohol consumption and being physically active increased the odds of psychological distress in female only.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the associations between various sociodemographic, psychosocial environment, and health behaviour factors and psychological stress and distress using nationally representative survey data (KNHANES). Different degrees and trends of associations were found between the different factors and psychological stress alone and distress. Additionally, these associations differed by gender.

More than substantial level of psychological stress coped with daily life was more prevalent among male or subjects aged in younger, while psychological distress which is severe mental problem such as feeling depressed or hopeless and suicidal ideation was more prevalent in female or subjects aged in older. The results correspond to previous studies reported that female are more psychologically and physiologically fragile for exposure to stressors and appeal more their negative emotion and mental symptom than male22,23.

Regarding the association of socio-demographic and psychosocial factors with the psychological distress among both male and female, a plausible explanation for these results is that most distress is caused by a loss of social support or relationships and worsening economic situations such as those caused by aging, living without a spouse, and being unemployed. The effects of those factors would be increased among those male aged in older, for whom retirement and bereavement are more frequent than among aged in younger. While, psychological stress might be initiated by conflict with people in their surroundings, when they live with other family members including their spouse or struggle to get better conditions such as higher income or promotion in position, and the effect has been furthered among subjects aged in younger and higher education level. Psychological stress was increased in higher household income among male, but it was inversed in female. Male are usually responsible for earning and could be in more stressful when they try to get more money, while female are usually responsible for spending and could be more stressful when they are in lack of money.

That the highest odds of distress were found for those with the lowest household income level is consistent with previous findings that financial difficulty increases psychological distress14,24. Correspondingly, a study showed that loss of employment is linked to increased distress (study was done in Norway among general population)13, as it may lead to financial strain16,25. Since males often have greater actual or perceived financial responsibility than females, this may lead to greater psychological impacts in men after retirement or loss of job26. Regarding the previous studies on educational differences in mental health problems, low education may be more consistently associated with severe mental health problems than minor psychiatric morbidity23,27–30, and it correspond with findings from current studies. Positive associations between being unmarried, bereaved, or divorced and psychological distress have been reported in previous studies, but there have been no such associations reported with psychological stress16,24,25. As shown in longitudinal studies including a study done for working-age population in Finland7,14, there was significant association between living alone and psychological distress in the current study.

Both slim and fat PBI showed significant associations with stress and distress among both males and females, while there was no significant association with BMI and either psychological state in either gender. This could indicate that perceived body image is a more important predictor of stress and distress than objectively measured bodyweight, even though many previous studies have suggested that unhealthy bodyweight, rather than perceived body image, predicts a higher prevalence of stress, depressive mood, and suicide attempts10,11,15,31,32. Interestingly, in the present study, slim PBI was also linked with higher odds of stress and distress than normal PBI in female. Furthermore, the odds of a slim PBI were relatively higher in the distressed group. As a study on the effect of distorted body weight perception on suicidal ideation among female in Korea suggested33, people who perceived their own bodies as abnormally slim usually had low body weight, but a large proportion of people who perceived their own bodies as abnormally fat were not objectively overweight. It is possible that slim PBI combined with low body weight is associated with distress or other specific environmental factors and unhealthy conditions that cause low body weight, thereby explaining the increased distress. Fat PBI without abnormally higher body weight could be linked more to stress than to distress.

We found that both short and long sleep duration was associated with increased distress in both gender, but only short sleep duration was associated with increased stress. Different study designs, target populations, and definitions of short and long sleep duration could cause inconsistent associations between sleep duration and psychological stress and distress34–39. Such U-shaped associations have also been found in a US study on postmenopausal women40, as well as some of previous studies that found associations of both insomnia and oversleeping with psychosocial stress and distress35,36,38,39.

Health behavioural factors such as current smoking, higher amount of alcohol drinking, and excessive calorie intake were associated with either psychological distress or stress among male. Among females, most health behaviours showed significant associations with both distress and stress (with the exception of physical activity and psychological stress), such as having ever been a smoker, being physically active, and either a lack of or excessive calorie intake. As suggested in previous studies, stress may increase (or decrease) appetite leading to greater (or lesser) calorie intake; additionally, changing body weight may be a cause of stress and distress41,42. Smoking and alcohol drinking are well-known stress behaviours and stress has been identified as a barrier to the uptake of behaviour change, although some studies suggest it may need to reach before impacting on behaviours6, 7,43,44. We found significant associations with stress and distress among females for both smoking and alcohol drinking, although only alcohol drinking was associated with stress among males. In Korea, as approximately 40% of males are current smokers and drinking alcohol is also more prevalent among males than in females3, it is difficult to identify differences among males regarding those behaviours.

Having chronic illness was associated with distress and stress in female, while the association was found in distress for men. Although some recent studies suggest psychological stress may increase the onset of chronic diseases, there are lots of room to be explained to confirm the findings because the role of psychological stress on disease developments and its’ interaction with disease-prone behaviours have not been distinguished, yet17.

These findings support the transactional model which emphasise environmental stimuli as stressors and social, psychological, and biological factors that affect both the occurrence of, and responses to, potential stressors5,45. Socio-demographic factors and psychosocial factors of the current study might be considered environmental stressors, and health behaviours and chronic illness could be explained as factors associated with occurrence of stress or results of response to stress. Furthermore, the current study added evidence on the association of various potential factors on psychological stress and distress with the representative sample of general population, which are in lack and need further study more.

Although the current study provided an overview of the factors associated with stress and distress among the general population in Korea using data from a nationwide population-based survey, it nonetheless had several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design means that temporality cannot be evaluated. Second, although self-reported data are commonly used in observational studies, such data are prone to recall bias and misclassification. Third, measures of the psychological state were obtained using only three questions, potentially resulting in imprecise data and misclassification of psychological states. However, these questions have been used in the KNHANES since 1998 as health indicators representing mental health with expert consensus, and previous study results obtained from these questions have concurred with results from other data sources. Fourth, stressful life events were not comprehensively assessed, although some such events were considered, such as living alone, negative outcomes of marriage, unemployment, overworking, and shift work.

Consequently, the current study found that sociodemographic factors, psychosocial factors, and health behaviours have different associations with psychological states with regard to their direction of association, type of stress (defined as stress and distress), and gender. However, psychosocial factors were suggested as important with respect to distress in both males and females, as well as stress among females in Korea. Therefore, specific approaches tailored to both the target population and psychological state are required to prevent and control psychological stress alone and distress. In addition, based on these results, further studies are warranted to help gain a better understanding of factors associated with psychological states.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the implementation of the study and the feedback of the manuscript. Y.C. and J.P. extracted the data, conducted the analysis and drafted the initial manuscript. M.K.L. conceptualized the study, interpreted results, and drafted the manuscript. E.Y.P., E.H.Y. and J.K.O. gave critical inputs on the interpretation of the results. B.Y.J. validated the data and conducted the analysis. All authors gave final approval for submission.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Yejin Cheon and Jinju Park.

References

- 1.Stress in America: Paying with Our Health. (American Psychological Association, Worcester, 2015).

- 2.Casey L. Stress and Wellbeing in Australia in 2011: A State of the Nation Survey. Melbourne: Australian Psychological Society; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Korea Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. http://knhanes.cdc.go.kr/knhanes/main.do (2016).

- 4.Kottler J, Chen D. Stress Management and Prevention: Applications to Daily Life. Boston: Cengage Learning; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paradies Y. A theoretical review of psychosocial stress and health. Int. J. Psychol. Res. 2010;5:205–222. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tavolacci MP, et al. Prevalence and association of perceived stress, substance use and behavioral addictions: A cross-sectional study among university students in France, 2009–2011. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:724. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feizi A, Aliyari R, Roohafza H. Association of perceived stress with stressful life events, lifestyle and sociodemographic factors: A large-scale community-based study using logistic quantile regression. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2012;2012:151865. doi: 10.1155/2012/151865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackson SE, Steptoe A, Beeken RJ, Kivimaki M, Wardle J. Psychological changes following weight loss in overweight and obese adults: A prospective cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e104552. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyce JA, Kuijer RG. Perceived stress and freshman weight change: The moderating role of baseline body mass index. Physiol. Behav. 2015;139:491–496. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cho Seon-Jin KC-K. The effect of female students' obese level and weight control behavior and attitudes on stress. Korean J. Health Educ. Promot. 1997;14:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim JY, Oh Dj Fau-Yoon T-Y, Yoon Ty Fau-Choi J-M, Choi Jm Fau-Choe B-K, Choe BK. The impacts of obesity on psychological well-being: A cross-sectional study about depressive mood and quality of life. J. Prev. Med. Public Health. 2007;40:191–195. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.2007.40.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma CC, et al. Shift work and occupational stress in police officers. Saf. Health Work. 2015;6:25–29. doi: 10.1016/j.shaw.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marum G, Clench-Aas J Fau-Nes RB, Nes Rb Fau-Raanaas RK, Raanaas RK. The relationship between negative life events, psychological distress and life satisfaction: A population-based study. Qual. Life Res. 2014;23:601–611. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0512-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pulkki-Råback L, et al. Living alone and antidepressant medication use: A prospective study in a working-age population. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:236. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Son, Y.-J. & Kim, G. The Relationship between Obesity, Self-esteem and Depressive Symptoms of Adult Women in Korea. Vol. 21 (Korean Society for the Study of Obesity, 2012).

- 16.Utz RL, Caserta M Fau-Lund D, Lund D. Grief, depressive symptoms, and physical health among recently bereaved spouses. Gerontologist. 2012;52:460–471. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hurst MW, Jenkins CD, Rose RM. The relation of psychological stress to onset of medical illness. Annu. Rev. Med. 1976;27:301–312. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.27.020176.001505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Western Pacific. The Asia-Pacific perspective: Redefining obesity and its treatment. Sydney: Health Communications Australia (2000).

- 19.Doinea M. Distributed application for calories optimization. Body Build. Sci. J. 2009;1:72–83. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roza Am Fau-Shizgal HM, Shizgal HM. The Harris Benedict equation reevaluated: Resting energy requirements and the body cell mass. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1984;40:168–182. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/40.1.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barros AJ, Hirakata VN. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: An empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2003;3:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-3-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matud MP, Bethencourt JM, Ibáñez I. Gender differences in psychological distress in Spain. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 2015;61:560–568. doi: 10.1177/0020764014564801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Molarius A, Granström F. Educational differences in psychological distress? Results from a population-based sample of men and women in Sweden in 2012. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e021007. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-021007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wada K, Eguchi H, Yoneoka D, Okahisa J, Smith DR. Associations between psychological distress and the most concerning present personal problems among working-age men in Japan. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:305. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1676-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Breslin FC, Mustard C. Factors influencing the impact of unemployment on mental health among young and older adults in a longitudinal, population-based survey. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health. 2003;29:5–14. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park JY, Moon KT, Chae YM, Jung SH. Effect of sociodemographic factors, cancer, psychiatric disorder on suicide: Gender and age-specific patterns. J. Prev. Med. Public Health. 2008;41:51–60. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.2008.41.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lahelma E, Laaksonen M, Martikainen P, Rahkonen O, Sarlio-Lähteenkorva S. Multiple measures of socioeconomic circumstances and common mental disorders. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006;63:1383–1399. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Molarius A, et al. Mental health symptoms in relation to socio-economic conditions and lifestyle factors—A population-based study in Sweden. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:302. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahnquist J, Wamala SP. Economic hardships in adulthood and mental health in Sweden. The Swedish National Public Health Survey 2009. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:788. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kosidou K, et al. Socioeconomic status and risk of psychological distress and depression in the Stockholm Public Health Cohort: A population-based study. J. Affect Disord. 2011;134:160–167. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sörberg A, et al. Body mass index in young adulthood and suicidal behavior up to age 59 in a cohort of Swedish men. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e101213. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Velten J, et al. Lifestyle choices and mental health: A representative population survey. BMC Psychol. 2014;2:58. doi: 10.1186/s40359-014-0055-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shin J, et al. The combined effect of subjective body image and body mass index (distorted body weight perception) on suicidal ideation. J. Prev. Med. Public Health Yebang Uihakhoe chi. 2015;48:94–104. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.14.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Charles LE, et al. Association of perceived stress with sleep duration and sleep quality in police officers. Int. J. Emerg. Ment. Health. 2011;13:229–241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang JJ, et al. The association of sleep duration and depressive symptoms in rural communities of Missouri, Tennessee, and Arkansas. J. Rural Health. 2012;28:268–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2011.00398.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chakravorty S, et al. Suicidal ideation in veterans misusing alcohol: Relationships with insomnia symptoms and sleep duration. Addict. Behav. 2014;39:399–405. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maglione JE, et al. Subjective and objective sleep disturbance and longitudinal risk of depression in a cohort of older women. Sleep. 2014;37:1–9. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alcántara C, et al. Sleep disturbances and depression in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Sleep. 2016;39:915–925. doi: 10.5665/sleep.5654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vares EA, Salum GA, Spanemberg L, Caldieraro MA, Fleck MP. Depression dimensions: Integrating clinical signs and symptoms from the perspectives of clinicians and patients. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0136037–e0136037. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kripke DF, et al. Sleep complaints of postmenopausal women. Clin. J. Women's Health. 2001;1:244–252. doi: 10.1053/cjwh.2001.30491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Isasi CR, et al. Psychosocial stress is associated with obesity and diet quality in Hispanic/Latino adults. Ann. Epidemiol. 2015;25:84–89. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosenberger PH, Dorflinger L. Psychosocial factors associated with binge eating among overweight and obese male veterans. Eat. Behav. 2013;14:401–404. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McKenzie SH, Harris MF. Understanding the relationship between stress, distress and healthy lifestyle behaviour: A qualitative study of patients and general practitioners. BMC Fam. Pract. 2013;14:166. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-14-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murray J, Honey S, Hill K, Craigs C, House A. Individual influences on lifestyle change to reduce vascular risk: A qualitative literature review. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2012;62:e403–410. doi: 10.3399/bjgp12X649089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Monroe SM. Modern approaches to conceptualizing and measuring human life stress. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2008;4:33–52. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]