Abstract

Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (PAH) is a rare and fatal disease where knowledge about its genetic basis continues to increase. In this study, we used targeted panel sequencing in a cohort of 624 adult and pediatric patients from the Spanish PAH registry. We identified 11 rare variants in the ATP-binding Cassette subfamily C member 8 (ABCC8) gene, most of them with splicing alteration predictions. One patient also carried another variant in SMAD1 gene (c.27delinsGTAAAG). We performed an ABCC8 in vitro biochemical analyses using hybrid minigenes to confirm the correct mRNA processing of 3 missense variants (c.211C > T p.His71Tyr, c.298G > A p.Glu100Lys and c.1429G > A p.Val477Met) and the skipping of exon 27 in the novel splicing variant c.3394G > A. Finally, we used structural protein information to further assess the pathogenicity of the variants. The results showed 11 novel changes in ABCC8 and 1 in SMAD1 present in PAH patients. After in silico and in vitro biochemical analyses, we classified 2 as pathogenic (c.3288_3289del and c.3394G > A), 6 as likely pathogenic (c.211C > T, c.1429G > A, c.1643C > T, c.2422C > A, c.2694 + 1G > A, c.3976G > A and SMAD1 c.27delinsGTAAAG) and 3 as Variants of Uncertain Significance (c.298G > A, c.2176G > A and c.3238G > A). In all, we show that coupling in silico tools with in vitro biochemical studies can improve the classification of genetic variants.

Subject terms: Mutation, Cardiovascular biology, Gene regulation

Introduction

Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (PAH) is a rare form of Pulmonary Hypertension (PH, WHO group 1) characterized by the remodeling of the precapillary pulmonary arteries, producing an increase in blood flow resistance that eventually leads to right heart failure and death1. PAH is a rare disease (ORPHA #182090) that in Spain affects over 16 adults/million inhabitants, with an incidence of 3.7 cases/million inhabitants per year as shown by the Spanish PAH registry for patients over 18 years (REHAP)2.

PAH comprises a wide variety of clinical representations with different etiopathogenesis that share clinical and anatomopathological characteristics. PAH can be subdivided in different subtypes: idiopathic (IPAH), heritable (HPAH), induced by toxins or drugs, associated with other diseases (APAH) such as connective tissue disease, HIV infection and congenital heart disease among many others. PAH long term responders to calcium channel blockers, PAH with overt features of venous/capillaries (PVOD/PCH, often misdiagnosed as IPAH) involvement, and persistent PH of the newborn3.

The genetic basis of PAH has been slowly uncovered since the 2000s when mutations in the Bone Morphogenetic Protein Receptor of type 2 (BMPR2) where described4,5. Mutations in BMPR2 are the most common cause of PAH, being present in up to a 70–80% of HPAH cases and 10–20% of IPAH6. More than 17 genes have been linked to the disease with different levels of evidence; with higher evidence: BMPR2, EIF2AK4, TBX4, ATP13A3, GDF2; SOX17, AQP1, ACVRL1, SMAD9, ENG, KCNK3, CAV1; with lesser: SMAD4, SMAD1, KLF2, BMPR1B, KCNA57,8; and the newest addition ABCC89. Mainly, PAH shows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern with sex dependent incomplete penetrance, 14% in males and 42% in females10, this helps to understand why 60–80% of the patients in most of the registries are female11,12. Thus, additional factors influencing the development of the disease, as environmental, epigenetic and genetic background roles have not been clearly elucidated yet.

The identification of mutations in the ion channel coding genes KCNK3 (TASK1) and KCNA5 (Kv1.5) first labeled PAH as a channelopathy13,14. Since their description, plenty of causal mutations have been described and tested in these genes15–17, and novel treatments for PAH have been proposed18. Alterations in genes coding for ATP related channels have also been described, such as ATP1A2 (encoding for α2-subunit of the Na+/K+-ATPase)19, ATP13A37, which codes for a member of the P-type ATPase family of proteins including ABCC89.

ABCC8 (ATP-binding Cassette subfamily C member 8) codifies for SUR1, a subunit of the hetero-octameric membrane KATP protein complexes. KATP channels are composed by four ABCC family members’ sulfonylurea receptors (SUR, SUR1, SUR2A or SUR2B) and four pore forming subunits from the inward-rectifier potassium channel 6 (Kir6)20–22, either the Kir6.1 codified by KCNJ8 or the Kir6.2 codified by KCNJ11. The subunits forming the KATP channels are dependent of the cellular type, and SUR1 is mostly present in the β pancreatic cells20. This explains why mutations in ABCC8 have been widely related to type II diabetes mellitus and congenital hyperinsulinism23–25. However, how ABCC8 can cause PAH remains unclear.

In this study, we analyzed a sub-cohort of the Spanish PAH Registry (REHAP) with variants in the ABCC8 gene. We aimed to characterize the variants with both in silico and in vitro analyses.

Results

Description of the cohort

In this study, a total of 744 individuals were analyzed, including 624 patients (579 adults and 45 pediatric) and 120 first degree relatives (from trios and cosegregration studies of positive cases). Baseline characteristics of this cohort are provided in Supplementary Table 1. ABCC8 variants were identified in 11 patients (1.76% of the patients analyzed). The mean age at diagnosis of these 11 patients was 34 ± 10 years whereas 6 of them were female (54%). Patients 3, 4, 6, 8 and 11 were diagnosed with Idiopathic Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension and patient 4 had a familial form. Patient 7 had PAH associated to Systemic Sclerosis. Patient 10 had a ventricular septal defect, which was repaired at 40 years of age. Patient 2 was clinically diagnosed with possible PVOD associated with systemic sclerosis and HIV infection; PH was diagnosed at 57 years of age. The patient fulfilled all clinical and radiological criteria, so the patient was initially diagnosed with PVOD. DLCO at diagnosis was 22% of predicted value. CT scan showed the typical triad of PVOD: ground glass opacities, interlobular septal thickening and mediastinal lymphadenopathies. The patient also had respiratory insufficiency at rest and significant drop of oxygen desaturation during exercise. Patient 11 was diagnosed at 24 years of age. In the initial diagnosis work-up, restrictive ventricular septal defect was observed. Suprasystemic PAH and right to left shunt were confirmed in the RHC. Considering these findings, ventricular septal defect closure was contraindicated and the patient is currently receiving systemic prostanoids.

Most of the patients showed a Functional Class III (64%) at diagnosis and the mean distance in 6 min’ walk test was 400 ± 120 m. At the moment RHC was performed; Cardiac Index was 2.7 ± 0.7 l/min/m2, mean Pulmonary Artery Pressure 58.8 ± 21.8 mmHg, Right Atrium Pressure 7 ± 3 mmHg and Pulmonary Vascular Resistance 10.8 ± 4.7. All the clinical variables are disclosed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the patients carrying ABCC8 variants.

| Variant | c.211C > T p.(His71Tyr) | c.298G > A p.(Glu100Lys) | c.1429G > A p.(Val477Met) | c.1643C > T p.(Thr548Met) | c.2176G > A p.(Ala726Thr) | c.2422C > A p.(Gln808Lys) | c.2694 + 1G > A | c.3238G > A p.(Val1080Ile) | c.3288_3289del p.(His1097ProfsTer16) | c.3394G > A p.(Asp1132Asn) | c.3976G > A p.(Glu1326Lys) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gnomAD frequency | 0 | 0.00007162 | 0.000007957 | 0.00006322 | 0.0004671 | 0.00005303 | 0.000003979 | 0.00003536 | 0 | 0.00003185 | 0.0001452 |

| PAH type | CHD associated | PVOD | IPAH | IPAH | HPAH | IPAH | CTD associated | IPAH | IPAH | CHD associated | IPAH |

| Sex | Male | Male | Male | Female | Male | Female | Female | Female | Female | Female | Male |

| Age of diagnoses, y | 24 | 58 | 32 | 27 | 36 | 34 | 26 | 43 | 29 | NA | 31 |

| FC | II | III | III | III | III | III | III | III | II | II | NA |

| PAP mmHg | 150/70/90 | 47 | 62/27/39 | 96/36/58 | 136/55/91 | 45/18/29 | 125/48/78 | 114/26/55 | 69/33/45 | 57/26/38 | 100/66/77 |

| RAP mmHg | 12 | 2 | 12 | 9 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 9 | 6 | 10 | 6 |

| CI l/min | 4.1 | 5.9 | 4.8 | 4.08 | 4 | 5.4 | 5.75 | 4.6 | 5.6 | 2.9 | 4.8 |

| IC | 2.5 | 3.5 | 2 | 2.55 | 2.15 | 2.9 | 3.57 | 2.7 | 3.94 | 1.65 | 2.3 |

| PVR, WU | 18.5 | 6.7 | 12 | 10 | 19.25 | 4 | 12.9 | 13.2 | 6.6 | 8.27 | 13.2 |

| PRVi, uxm2 | 47.5 | 11.4 | 28.68 | 18.8 | 35.8 | 5.9 | 20.7 | 17.8 | 9.3 | 14.5 | 29.6 |

| O2 Sat % PA | 67 | 68 | NA | 76 | 59 | 98 | 98 | 96 | NA | 74 | NA |

| O2 Sat % AO | 78 | 89 | 93 | 95 | 93 | NA | 68 | NA | NA | 96 | 95 |

| NT-pro-BNP | NA | 2,180 | NA | 402 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 83 | 327 | NA |

| T6MW m (no O2) | 484 | 180 | 276 | 525 | 525 | 420 | 463 | 336 | 562 | 366 | 266 |

| ECO RA cm2 | 28 | NA | 15 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 11.9 | 15 | NA |

| Eco RV mm | 64 | 65 | 52 | 39 | 51 | NA | NA | NA | 29 | 51 | NA |

| DLCO, % | NA | 22.5 | 92 | 63 | 100 | 72 | 74 | 73 | 92 | NA | 74 |

| Treatment | PDEi-5, ERAs, systemic prostanoids | PDEi-5, ERAs, inhaled prostanoids | PDEi-5, systemic prostanoids | PDEi-5, ERAs, systemic prostanoids | PDEi-5, ERAs, systemic prostanoids | PDEi-5, ERAs | PDEi-5, ERAs, systemic prostanoids | Systemic Prostanoids | PDEi-5, ERAs | ERAs | PDEi-5, ERAs, selexipag |

| Survival Time; y | 4 | 4.5 | 22.5 | 8 | 7 | 12 | 18 | 18 | 9 | 4 | 18 |

| Final status | Alive | Exitus | Alive | Alive | Transplant | Alive | Alive | Alive | Alive | Alive | Alive |

| Variants in PAH genes | SMAD1 c.27delinsGTAAAG p.(Phe9LeufsTer2) | None | None | None | None | None | None | None | None | None | None |

| Comorbidities | None | None | None | None | None | None | None | None | None | None | None |

| Other Commentaries | Restrictive interventricular septal defect and suprasystemic pulmonary hypertension | Clinical diagnosis of PVOD | None | None | None | None | None | None | None | PAH diagnosed after ostium secundum surgery | None |

ExAC Exome Aggregation Consortium, PVOD pulmonary venooclusive disease, CTD connective tissue disease, CHD congenital heart disease, y years, FC functional class, PAP pulmonary arterial pressure, RAP right atrial pressure, CI cardiac index, PVR pulmonary vascular resistance, PVRi PVR index, O2 sat O2 saturation, NT-pro-BNP B type natriuretic peptide, T6MW 6-min walk test, ECO RA right atrium echocardiography, ECO RV right ventricle echocardiography, DLCO diffusing capacity, PDEi-5 phophodiesterase inhibitors, ERAs endothelin receptor antagonists, NA not available.

Mutational screening

After filtering for rare variants, 11 heterozygous changes were detected in the ABCC8 gene, nine of them were missense variants: c.211C > Tp.(His71Tyr), c.298G > A p.(Glu100Lys), c.1429G > A p.(Val477Met), c.1643C > T p.(Thr548Met), c.2176G > A p.(Ala726Thr), c.2422C > A p.(Gln808Lys), c.3238G > A p.(Val1080Ile), c.3394G > A p.(Asp1132Asn) and c.3976G > A p.(Glu1326Lys). An intronic variant: c.2694 + 1G > A; and a frameshift: c.3288_3289del p.(His1097ProfsTer16) were also detected. The patient carrying the ABCC8 variant c.211C > Tp.(His71Tyr) also carried in heterozygosis a variant in SMAD1 gene (c.27delinsGTAAAG p.Phe9LeufsTer2). We did not find any Copy Number Variation (CNV) encompassing the genes in the panel (ACVRL1; GDF2; BMPR1B; BMPR2; CAV1; EIF2AK4; ENG; KCNA5; KCNK3; NOTCH3; SMAD1; SMAD4; SMAD5; SMAD9; TBX4; TOPBP1; SARS2; CPS1; ABCC8; CBLN2; MMACHC) in this set of patients.

Several of these variants have been described in other pathologies. The variant c.298G > A p.(Glu100Lys) was described in Maturity Onset Diabetes of the Young25. Variants c.2176G > A p.(Ala726Thr), c.3976G > A p.(Glu1326Lys) and c.2694 + 1G > A were found in congenital hyperinsulinism patients26–28. Lastly, c.2422C > A p.(Gln808Lys) has been described in a diabetes mellitus type 1 patient27. For the rest of the variants no relation with any disease has been found, c.211C > Tp.(His71Tyr) and c.3288_3289del p.(His1097ProfsTer16) are described here for the first time. The rs identification of all the variants can be found in Supplementary Table 2.

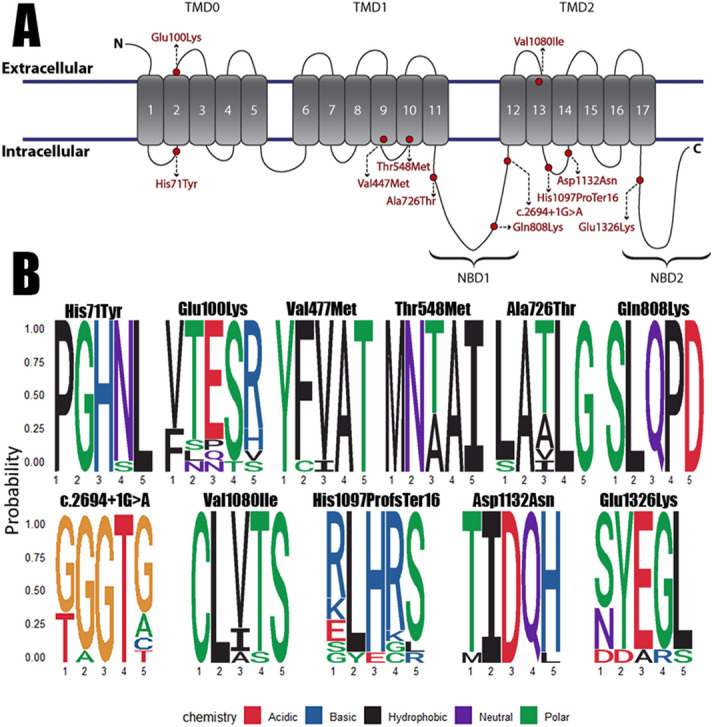

Most of the variants are located in cytoplasmic domains: c.211C > T p.(His71Tyr), c.2176G > A p.(Ala726Thr), c.2422C > A p.(Gln808Lys), c.3288_3289del p.(His1097ProfsTer16), c.3394G > A p.(Asp1132Asn) and c.3976G > A p.(Glu1326Lys). Three are located in transmembrane domains: c.1429G > A p.(Val477Met), c.1643C > T p.(Thr548Met) and c.3238G > A p.(Val1080Ile). Only one is located in an extracellular domain (Fig. 1); c.298G > A p.(Glu100Lys).

Figure 1.

Location of the variants and conservation of the amino acid or nucleotide positions in SUR1. (A) Visual scheme of the localization of the variants detected in ABCC8 after translation to SUR1 in our cohort (red). Five variants are located in the cytoplasmic domain, three in the transmembrane domain and one in the extracellular domain. The variants are marked as a yellow circle; the positions have been estimated from Uniprot SUR1 entry (#Q09428). (B) Sequence logos from the comparison of 14 ABCC8 reference sequences from different animals to evaluate the conservation of the mutated positions. The variants are located in the 3rd position of the logo. The nature of the amino acid nature is also stated in a legend with the exception of c.2694 + 1G > A.

Interestingly, six of these variants are present in functional SUR1 positions. Two variants; c.211C > T p.(His71Tyr) and c.298G > A p.(Glu100Lys); are located at the first transmembrane domain (TMD0), a region that interacts closely with Kir6.2. While the resulting four variants are located within Nucleotide-Binding Domains (NBD) where ATP binds, concretely, c.2176G > A p.(Ala726Thr), c.2422C > A p.(Gln808Lys) and c.2694 + 1G > A (after exon 22) at NBD1; and c.3976G > A p.(Glu1326Lys) at NBD2.

Only two families decided to undertake cascade testing. Patient 4 (carrying p.Thr548Met) inherited the variant from his mother (unaffected carrier), his father was WT. In the case of patient 7 (carrying c.2694 + 1G > A), her mother was WT and her father was deceased years before the enrollment in the registry, so the variant was either de novo or inherited from her father.

Variant in silico analysis and classification

The ACMG prediction score was used to determine the grade of evidence to support the pathogenicity (PP3) and benignity (BP4) of the variants: BP4 (0–2), Variant of Uncertain Significance (VUS) (2–4) and PP3 (4–7). In the case of frameshift or exon skipping mutations (PVS1) was stated. A summary of all the predictions is detailed in Tables 2 and 3. Variants c.298G > A p.(Glu100Lys), c.2176G > A p.(Ala726Thr) and c.3238G > A p.(Val1080Ile) were classified as VUS. c.211C > Tp.(His71Tyr), c.1429G > A p.(Val477Met), c.1643C > T p.(Thr548Met), c.2422C > A p.(Gln808Lys), c.2694 + 1G > A, c.3976G > A p.(Glu1326Lys) and the SMAD1 variant c.27delinsGTAAAG p.(Phe9LeufsTer2) were classified as likely pathogenic. Lastly, c.3288_3289del p.(His1097ProfsTer16) and c.3394G > A p.(Asp1132Asn) were classified as pathogenic.

Table 2.

In silico analysis to predict the effect of the variants identified in the ABCC8 gene.

| cDNA and protein position | Annovar impact | CADD | Sift | Polyphen2 | MutAssesor | Fathmm | VEST | Score | ACMG Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c.211C > T p.(His71Tyr): | – | Damaging | Damaging | Probably damaging | Damaging | Damaging | Damaging | 5.5/7 | Likely pathogenic |

| c.298G > A p.(Glu100Lys) | MODERATE | Possibly damaging | Benign | Benign | Benign | Damaging | Possibly damaging | 2.5/7 | VUS |

| c.1429G > A p.(Val477Met) | MODERATE | Damaging | Damaging | Damaging | Possibly damaging | Damaging | Damaging | 6/7 | Likely pathogenic |

| c.1643C > T p.(Thr548Met) | MODERATE | Damaging | Damaging | Damaging | Possibly damaging | Damaging | Possibly damaging | 5.5/7 | Likely pathogenic |

| c.2176G > A p.(Ala726Thr) | MODERATE | Damaging | Benign | Benign | Benign | Damaging | Benign | 2.5/7 | VUS |

| c.2422C > A p.(Gln808Lys) | MODERATE | Damaging | Possibly damaging | Probably damaging | Benign | Damaging | Damaging | 4.5/7 | Likely pathogenic |

| c.2694 + 1G > A | – | Damaging | – | – | – | – | – | 1/7 | Likely pathogenic |

| c.3238G > A p.(Val1080Ile) | MODERATE | Damaging | Benign | Benign | Benign | Damaging | Benign | 2.5/7 | VUS |

| c.3288_3289del p.(His1097ProfsTer16) | HIGH | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1/7 | Pathogenic |

| c.3394G > A p.(Asp1132Asn) | MODERATE | Damaging | Damaging | Damaging | Damaging | Damaging | Possibly damaging | 6/7 | Pathogenic |

| c.3976G > A p.(Glu1326Lys) | MODERATE | Damaging | Possibly damaging | Benign | Benign | Damaging | Damaging | 4/7 | Likely pathogenic |

| SMAD1 c.27delinsGTAAAG p.(Phe9LeufsTer2) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Likely pathogenic |

CADD ranges: s > 14 damaging, s in [11,14) possibly damaging, SIFT ranges: benign s > 0.23, possibly damaging s in (0.06, 0.23), damaging s ≤ 0.06. Polyphen2 ranges: benign s < 0.03, possibly damaging s in (0.03, 0.3), damaging s > 0.3. MutAssesor ranges: benign s < 1.12, possibly damaging s in [1.12, 1.8), damaging s > 1.8. Vest ranges: Benign s < 0.17, possibly damaging s in [0.17, 0.65), damaging s ≥ 0.65.

Table 3.

Splicing in silico analysis of the variants detected in the ABCC8 gene.

| cDNA and protein position | ada.Pred | rf.Pred | NetGene2 | NNSPLICE | HSF | Minigene assay |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c.211C > T p.(His71Tyr) | – | – | Neutral | Neutral | Activation of an exonic cryptic donor site. Alteration of an exonic ESE site. Potential alteration of splicing | Neutral |

| c.298G > A p.(Glu100Lys) | – | – | Neutral | Neutral | Alteration of an exonic ESE site. Potential alteration of splicing | Neutral |

| c.1429G > A p.(Val477Met) | – | – | Neutral | Splice site score reduced | Creation of an exonic ESS site. Alteration of an exonic ESE site. Potential alteration of splicing | Neutral |

| c.1643C > T p.(Thr548Met) | – | – | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral | N.A |

| c.2176G > A p.(Ala726Thr) | – | – | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral | – |

| c.2422C > A p.(Gln808Lys) | – | – | Creation of a novel splicing acceptor site | Creation of a novel splice site | Creation of an exonic ESS site. Alteration of an exonic ESE site. Potential alteration of splicing | N.A |

| c.2694 + 1G > A | Possibly damaging splicing site | s > 0.612 | Possibly damaging splicing site | s > 0.598 | Donor site affected (0.0 confidence) | Neutral | Creation of an exonic ESS site. Potential alteration of splicing | N.A |

| c.3238G > A p.(Val1080Ile) | – | – | Acceptor splice sites scores increase | Neutral | Neutral | – |

| c.3288_3289del p.(His1097ProfsTer16) | – | – | Creation of a novel splicing acceptor site. Splice acceptor site score increases | Neutral | Creation of an exonic ESS site. Alteration of an exonic ESE site. Potential alteration of splicing | N.A |

| c.3394G > A p.(Asp1132Asn) | – | – | Neutral | Splice site score reduced | Alteration of an exonic ESE site. Potential alteration of splicing | Exon skipping |

| c.3976G > A p.(Glu1326Lys) | – | – | Creation of a novel splicing acceptor site | Neutral | Creation of an exonic ESS site. Potential alteration of splicing | N.A |

The splicing effect predictions were taken into account to decide whether or not experimental confirmations needs to be performed, scores are detailed in Table 3. The variants where 2 predictors showed alterations were automatically considered candidates. Exceptions were made for c.298G > A p.(Glu100Lys) due to its location within an intron–exon junction, c.211C > T p.(His71Tyr) because of the possible partial loss of the exon, and c.1643C > T p.(Thr548Met) that was chosen to assess a missense “control” variant in the assay.

Overall, most of the variants were conserved among the evolution, c.211C > T p.(His71Tyr), c.2422C > A p.(Gln808Lys), c.2694 + 1G > A and c.3394G > A p.(Asp1132Asn were highly conserved. Whereas c.1429G > A p.(Val477Met), c.2422C > A p.(Gln808Lys) and c.3976G > A p.(Glu1326Lys) were conserved mostly in vertebrates so there is some variability when moving farther from humans. Lastly, c.298G > A p.(Glu100Lys), c.1643C > T p.(Thr548Met), c.2176G > A p.(Ala726Thr) and c.3238G > A p.(Val1080Ile) were not conserved (Fig. 1B).

Minigene assay

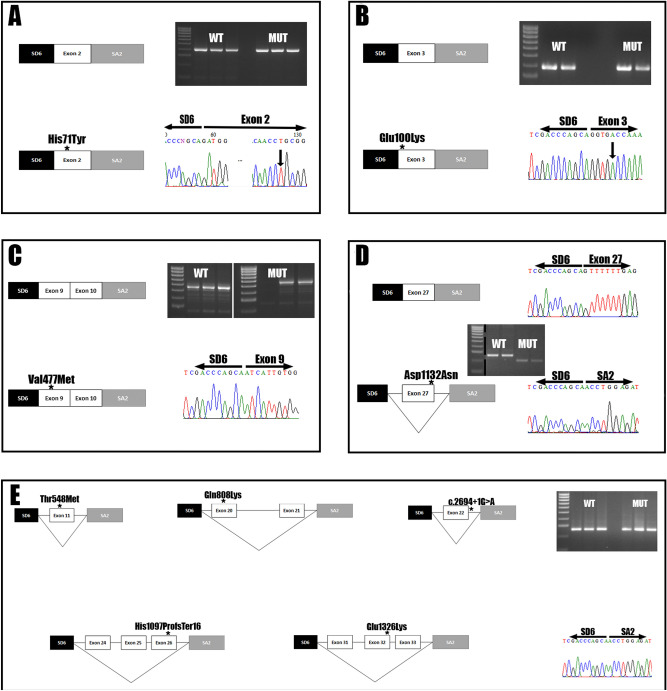

Based on the in silico analysis we selected 9 out of 11 variants for the minigene assay: c.211C > T p.(His71Tyr), c.298G > A p.(Glu100Lys), c.1429G > A p.(Val477Met), c.1643C > T p.(Thr548Met), c.2422C > A p.(Gln808Lys), c.2694 + 1G > A, c.3288_3289del p.(His1097ProfsTer16), c.3394G > A p.(Asp1132Asn), c.3976G > A p.(Glu1326Lys). Only four out of nine constructs worked as expected (c.211C > T p.(His71Tyr), c.298G > A(p.Glu100Lys), c.1429G > A p.(Val477Met) and c.3394G > A p.(Asp1132Asn); Fig. 2A–D) while the constructs encoding the variants located in/or near the exons 20, 21, 22, 24, 25, 26, 31, 32 and 33 did not transcribe any of the ABCC8 exons present in the construction (Fig. 2E). The variants c.211C > T p.(His71Tyr), c.298G > A p.(Glu100Lys) and c.1429G > A p.(Val477Met) did not alter the correct splicing of the exons 2, 3, 9 and 10, as they were detectable in both the wild type and the mutated construct (Fig. 2A–C). However, c.3394G > A p.(Asp1132Asn) induced the complete skipping of the exon 27 due to the alteration of an exonic splicing enhancer site (Fig. 2D), this change causes a frameshift leading to the creation of a stop codon in the former exon 28, producing a truncated protein of 1,118 amino acids. All the constructs with coding exons that were not detected in the assay (neither in the mutated nor wild type) were sequenced to confirm the integrity of the inserts.

Figure 2.

Minigene assay highlight the pathogenicity of c.3976G > A and a complex regulation in ABCC8 transcription. Every subset of images includes a box scheme of the mRNA analysis results, its representing gel electrophoresis and Sanger sequencing results from the exon junction found. (A) The p.His71Tyr variant located in exon 2 does not alter splicing. (B) The p.Glu100Lys variant located in the exon 3 does not alter splicing. (C) The p.Val477Met variant located in exon 9 does not impair splicing; both exon 9 and exon 10 are detectable. (D) The p.Asp1132Asn variant located in exon 27 induces an exon skipping event. The gel electrophoresis image is cut because two different constructs were tested in the same gel. (E) Exons 11, 20, 21, 22, 24, 25, 26, 31, 32 and 33 were not transcribed in both wild type and variant constructs making it impossible to correctly test the splicing effects of the described variants. Unedited images for all the gels are provided as supplementary material.

ABCC8 regulation analysis

The ABCC8 gene introns have a high amount of regulatory regions, enhancing positions, LINEs and SINEs (Supplementary Fig. 1). Also, there are four enhancer regions identified in the GENEHANCER study29 that are located in regions surrounding the exons that did not transcribe in our minigene constructs: GHJ017432 surrounding exon 11; GH11J017412 including exons 18, 19 and 20; GH11J017411 before exon 22; GH11J017404 comprehending exons 26, 27 and 28; lastly, GH11J017401 upwards of exon 30. These enhancing regions are used by a wide variety of transcription factors detailed in Supplementary Table 3. We also used the MaxEntScan tool from Human Splicing Finder to measure the strength of the splice sites encoding the exons used in the minigenes. We did not find a correlation between the predicted strength of the site and the expression of the minigene construct (Supplementary Table 4).

Protein modeling

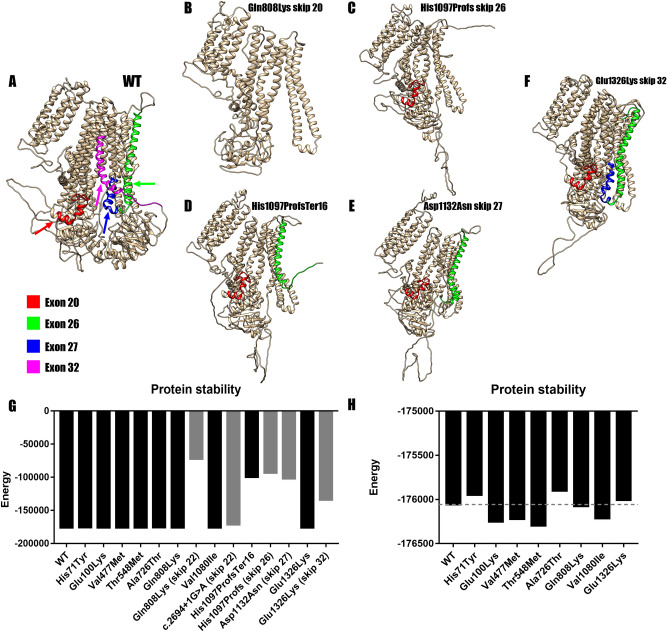

All variants that were not experimentally validated, c.1429G > A p.(Val477Met), c.2176G > A p.(Ala726Thr), c.2422C > A p.(Gln808Lys), c.3238G > A p.(Val1080Ile), c.3976G > A p.(Glu1326Lys) did not alter the protein structure nor its stability (Fig. 3G,H) based on an in silico analysis when compared with the wild type (Fig. 3A). The simulated skipping of exon 20 in c.2422C > A p.(Gln808Lys) was predicted to be the most destabilizing both at structure (Fig. 3B) and stability level (Fig. 3G), producing a protein of 836 amino acids. However, the skipping of exon 22 in c.2694 + 1G > A barely affected its stability (Fig. 3H), probably due to the predicted in frame loss of only 46 amino acids. For c.3288_3289del p.(His1097ProfsTer16), both the frameshift and the simulated skipping of exon 26 yielded a truncated protein of 1,111 and 1,056 amino acids respectively, that showed altered structure (Fig. 3C,D) and protein stability (Fig. 3G), so this variant can be considered equally pathogenic whether it affects splicing or not. The simulated skipping of exon 32 in c.3976G > A p.(Glu1326Lys) produces a protein of 1,292 amino acids that alters slightly its structure (Fig. 3F) and protein stability (Fig. 3H). Regarding the minigene validated variants, only the c.3394G > A p.(Asn1132Asp) caused major alterations in protein structure (Fig. 3E) and its stability (Fig. 3G). All the missense variants, both confirmed and unconfirmed, were compared in detail (Fig. 3H). Concerning the stability, the variations accounted were of less than ± 500 between them and the wild type. We then analyzed all the missense variants with Missense3D, which showed no structural alterations caused by the amino acid substitutions.

Figure 3.

Protein modeling of the most unstable variants. (A) Wild type SUR1 marked for the target exon. Red marks exon 20, green for exon 26, blue for the exon 27 and magenta for exon 32. (B) Structure for Gln808Lys in the case of an exon skipping event. The resulting protein loses 747 amino acids and so its structure is altered. (C) Structure of His1097ProfsTer16 skipping exon 26. The protein loses 527 amino acids altering its structure. (D) Structure of the resulting protein of His1097ProfsTer16. The protein loses a total of 471 amino acids and its structure is altered. (E) Structure after the mRNA confirmed skipping of exon 27 due to p.(Asp1132Asn). The skipping of exon 27 truncates the protein making it lose 463 amino acids and altering its structure. (F) Structure for Glu1326Lys after the skipping of exon 32. The protein loses 290 amino acids; the structure is altered but not as much as in earlier skips. (G) Comparison of DOPE energies between the models of the wild type (WT) SUR1 and the mutated proteins (Black for missense models and gray for exon skippings). All the amino acid substitutions showed similar stability when compared to the wild type. However, Gln808Lys (exon 22), His1097ProfsTer16, His1097ProfsTer16 (skip 26), Asp1132Asn (skip 27) and Glu1326Lys (skip 32) showed a much lower stability which would mean more unstable proteins. (H) Detailed graphic comparing all the missense variants and the WT template. None of the variants showed high DOPE energy variation when compared with the WT.

All the homology models generated by Phyre2 showed less stability than the template used for its modeling (Supplementary Fig. 2), as expected when comparing an experimentally obtained template and simulated (modeled) data.

Discussion

PAH is a devastating disease if it is not treated. During the last decade the application of high throughput sequencing has increased the knowledge on the genetic basis of PAH, becoming a strong tool with high potential to find out novel treatments30.

In this study we identified by a custom NGS targeted sequencing panel of 21 genes (HAP v1.2), eleven variants in ABCC8 gene after screening 624 patients from the Spanish PAH Registry (REHAP).

This set of patients with ABCC8 variants compose a 1.76% of our cohort and show a younger age of diagnosis when compared with other recent studies9,31. Also, they seem to show more severe forms of the disease with higher PAP values and FC, but this may be due to the small number of patients in our cohort referring variants in this gene. Regarding the etiologies, this set is composed mostly by IPAH patients, with two patients of CHD-APAH and single patients of HPAH, CTD-APAH and, for the first time, an associated form of PVOD.

None of them show any clinical feature related to congenital hyperinsulism as mutations in the ABCC8 gene have been described in this disorder23–25.

Most of the detected ABCC8 variants were located in regions within or near exon–intron boundaries so the possible effects in the splicing had to be taken into account. After using pathogenicity and splicing predictors, we tested nine variants through minigene assay to determine the effect in splicing at mRNA level. Only four of the constructs worked as expected, confirming the correct processing of c.211C > T p. (His71Tyr), c.298G > A p.(Glu100Lys) and c.1643C > T p.(Thr548Met) located in exons 2, 3 and 9, respectively. The variant c.3394G > A p.(Asp1132Asn) causes an exon skipping of exon 27 of ABCC8, so we propose to change its nomenclature at RNA level from r.3394G > A to r.del3330_3399 and at protein level from p.(Asp1132Asn) to p.?. Unfortunately, constructs did not work in the five remaining variants; therefore, the possible splicing effect for these variants remains unknown. This may be due to neither the wild type nor the mutated exons were transcribed in our constructs. As a first approach, we tried to perform the minigene assay using standard length minigene constructs. With a fragment containing the exon of interest and, at least, 100–200 bp around 3′ and 5′, this approach allowed us to detect the exon 27 skipping, but none of the other constructs transcribed the exons, so we decided to use longer constructs with 800–1,500 bp around including multiple exons. With this approach we were able to confirm that c.211C > T p.(His71Tyr), c.298G > A p.(Glu100Lys) and c.1643C > T p.(Thr548Met) do not alter the splicing. Thus, we hypothesize that this inability to transcribe those exons may have been mediated by the absence of regulatory elements for these exons. HeLa cells express ABCC8 (Protein Atlas) and should have all the cellular machinery needed to do it, so we discarded a tissue specificity problem. The UCSC genome browser analysis of ABCC8 revealed regulatory regions before or within the exons 11, 18, 19 20, 26, 27, 28, 29 and 30 (Supplementary Fig. 1). One of them has binding sites for up to 40 transcription factors. Length of this regions are variable, ranging from less than 200 up to 2,000 bp, and strikingly, the constructs that worked (exons 2, 3, 9 and 10) did not have any regulatory element nearby, but exon 27 was right in the middle of one, and apparently 351 bp of it (including the exon) were enough to allow it to be transcribed.

Furthermore, in the non-working constructs we had most of the regulatory region within exon 11 (GH11J017432); in the case of exon 20 and 21, the 1,200 bp insert included 800 bp of the regulatory region encoding exon 20 (GH11J017412); for exon 22, we missed the region GH11J017411 by 250 bp, this region is only 151 bp long; in the case of the construct 24–25–26 we had 500 bp of the GH11J017404 which encodes the end exon 25 and the whole exon 26; and lastly, the construct with exons 31–32–33 had its closest regulatory region 3,000 bp upstream of exon 31. The regulation by upstream regions and the need to use clusters of exons is not something new32, but it arises the limitations of testing splicing variants in vitro using minigenes instead of specific tissues, the larger the gene the more complicated its regulation will be as we can see in ABCC8. Thus, we would need to access specific tissue in order to properly test the pathogenicity of the resulting splicing variants.

In order to facilitate the in silico analysis, due to the unavailability of patient’s specific tissue, we chose a bioinformatics approach using protein homology modeling and protein stability analyses. We modeled the effect of the missense changes and the confirmed skipping variants. These results highlight how exon skipping events in most of the situations would yield an unstable protein that may be degraded, unable to fold correctly and probably non-functional.

All the amino acid changes simulated did not affect the overall structure and stability of the protein, but some of them are located in functional positions. p.(His71Tyr) and p.(Glu100Lys) are located in the region that interacts closely with the gating of the Kir6.2 pore domain33. It is likely that additional changes affecting NBD1 (p.Ala725Thr, p.Gln808Lys) and NBD2 (p.Glu1326Lys) alter the catalytic activity of SUR1, and therefore, its role to provide stability and regulate Kir6.2 gating. The variants located at the transmembrane domains could not have a high functional effect, but electrophysiology studies are needed.

It is noteworthy that the patient with the p.(His71Tyr) variant was also carrying in heterezygosity an indel in the SMAD1 gene (c.27delinsGTAAAG), producing an early frameshift in SMAD1 p.(Phe9LeufsTer2) that yields the complete loss of the allele. Mutations in SMAD1 have been related to PAH, and functional studies have confirmed the decrease in signaling due to missense variants34, but the exact molecular mechanism that leads to PAH remains unknown35. Thus, we propose that PAH in this patient may be caused by the combination of both variants, where one of them could act as a 2nd hit needed to start PAH pathogenesis.

Bohnen et al.9 have already shown that amino acid substitutions affect the correct electrophysiological function of the SUR1-Kir6.2 complex. Their study is performed using cDNA constructs encoding the variants to test. This means that all the variants analyzed will be treated as missense, and one would be losing all the effects from the possible alterations of the splicing process. Also, mRNA processing can play a vital role in the amount of mutant protein that is traduced; the mutated alleles can be degraded reducing the theoretical 50–50%.

Furthermore, the assembly of the SUR1-Kir6.2 complex should be random, yielding channels with 1, 2, 3 or 4 SUR1 wild type or mutated proteins (if not degraded) making almost compulsory to carry out several measurements of activity by single channel patch clamp to be able to appreciate the real effect. Using cell culture to validate novel PAH related genes is useful, but animal models are still needed to fully associate loss of function in ABCC8 to PAH. Until now, none of the mice models referring ABCC8 mutations or its complete gene knockout have been described to develop PAH according to Mouse Genetic Information data, weakening the link between the gene and the disease. ABCC8 expression pattern does not exactly fit with PAH known pathogenesis, as we would expect SUR1 to be highly expressed in cardiac and smooth muscle cells, but this is not the case, those tissues express much more the closely related SUR2 in combination with both Kir6.1 and Kir6.236. SUR1 is mainly expressed in pancreas, where its link to congenital hyperinsulinism37 and neonatal diabetes38 has been proven many years ago.

However, SUR1 is detectable in lung, proximal pulmonary arteries9 and heart atrium39. Therefore, the only way to link the loss of function in ABCC8 with PAH is if it induces a vasoconstrictor effect similar to hypoxia. In hypoxia, KATP channels are inhibited in the pulmonary smooth muscle cells, inducing Ca2+ uptake and thus, an increase in contraction and proliferation that could start PH18. This would end up increasing shear stress, inducing endothelial cells to proliferate40,41.

In conclusion, we report eleven novel changes in ABCC8 gene found in PAH patients. Thanks to in vitro biochemical analyses and in silico tools we were able to classify them according to ACMG: two as pathogenic, six as likely pathogenic and three as VUS (Table 4).

Table 4.

Summary table with the conclusions for each ABCC8 variant.

| cDNA and protein position | Conclusion |

|---|---|

| c.211C > T p.(His71Tyr): | Likely pathogenic, located in a gating regulatory region, confirmed missense, predictors agree |

| c.298G > A p.(Glu100Lys) | VUS, located in a gating regulatory region, confirmed missense, predictors do not agree |

| c.1429G > A p.(Val477Met) | Likely pathogenic, confirmed missense, all the predictors agree |

| c.1643C > T p.(Thr548Met) | Likely pathogenic, all the predictors agree, inconclusive minigenes, predicted non splicing altering |

| c.2176G > A p.(Ala726Thr) | VUS, located in NBD1, predictors do not agree, predicted non splicing altering |

| c.2422C > A p.(Gln808Lys) | Likely pathogenic, located in NBD1, inconclusive minigenes, possibly splicing altering |

| c.2694 + 1G > A | Likely pathogenic, located in NBD1, inconclusive minigenes, possibly splicing altering |

| c.3238G > A p.(Val1080Ile) | VUS, unconfirmed missense, predictors do not agree, predicted non splicing altering |

| c.3288_3289del p.(His1097ProfsTer16) | Pathogenic, clearly dysfunctional protein |

| c.3394G > A p.(Asp1132Asn) | Pathogenic, minigenes confirmed exon skipping, induces a frameshift |

| c.3976G > A p.(Glu1326Lys) | Likely pathogenic, located in NBD2, inconclusive minigenes, possibly splicing altering |

Materials and methods

Description of the cohort

Since November 2011, genetic studies have been offered to all patients included in the Spanish Registry of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (REHAP) with idiopathic and hereditable forms of PAH, and PVOD2,30. All the methods were performed in accordance with the ethical principles of the European Board of Medical Genetics and the 2015 ERS/ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension to provide accurate information on the range of options available to make informed decisions and allow equal access to genetic counseling and testing1. Pre and post-test genetic counseling was provided. All patients or legal tutors included in the analysis gave their informed consent. The project was approved by the ethical committee for scientific research of the Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre (Comité Ético de Investigación Clínica—Hospital 12 de Octubre).

First degree relatives to affected probands were clinically screened when available. Cascade or cosegregration genetic tests were also offered. When an unaffected carrier was identified, a complete diagnostic work-up was performed, including electrocardiogram, echocardiogram, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and 6 min’ Walk Test. Due to the typical phenotype, DLCO was also determined in healthy carriers. This evaluation is periodically repeated. When a sustained suspicion of early stage PAH was observed, right heart catheterization (RHC) was performed to rule out the condition.

Targeted panel sequencing

We analyzed all the patients (744) using a custom panel (HAP v1.2) designed with NimbleDesign (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), which includes a total of 21 genes (disease associated and research genes): ACVRL1; GDF2; BMPR1B; BMPR2; CAV1; EIF2AK4; ENG; KCNA5; KCNK3; NOTCH3; SMAD1; SMAD4; SMAD5; SMAD9; TBX4; TOPBP1; SARS2; CPS1; ABCC8; CBLN2; MMACHC. Next, fragmentation and capture of the target regions were performed with SeqCap EZ Choice Enrichment Kit (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and sequencing was carried out in Illumina MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, USA). We developed an in-house bioinformatics pipeline to analyze the raw data. After the filtering of the relevant variants, we validated the candidate variants through traditional Sanger Sequencing. Finally, we performed the review, classification and interpretation of the variants according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) guidelines42. We performed a CNV analysis applying the custom framework LACONv (https://github.com/kibanez/LACONv), which have been developed in-house. It detects gains and losses in genes included in the HAP v1.2 panel. The minimal depth by sample to be considered was 20×. The minimal depth in genomic intervals to be considered was 15×. The doses rate threshold for deletions is 0.60. The doses rate threshold for duplications was 1.20. The Z score threshold to establish CNVs (deletions) was − 2.000.

Sanger sequencing

A standard PCR was carried out using GoTaq Green master mix (Promega, Madison, USA) with annealing temperatures ranging between 58–65 °C depending on the construct (Supplementary Teble 2). PCR products were purified using the ExoSAP-IT kit (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, USA). When we had to purify bands from gel electrophoresis, the PCR cleanup gel extraction kit (Macherey–Nagel, Düren, Germany) was used. The sequencing was performed using the BigDye terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing kit (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, USA). We then precipitated the sequencing products and analyzed them in an ABI PRISM 3100 genetic analyzer (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, USA). Finally, sequences were aligned to the corresponding reference sequence from ENSEMBL (ENST00000389817.7).

Variant in silico analyses

The ABCC8 variants were analyzed to predict mutational effect with the following software: dbNSFP43, Annovar44, CADD45, Sift46, Polyphen247, MutAssesor48,49, Fathmm50 and VEST51. Regarding of the effect assessed by the predictors, we assigned each variant a prediction score with a maximum of 7 points following this criteria: 1 = “Damaging/High”, 0.5 = “Possibly damaging/Moderate” and 0 = “Benign”, the score was used to sum up the level of evidence from the predictors in order to classify the variants following the ACMG guidelines. Because most of the variants were located near or within exon–intron junctions, the following splice effect predictors were also used: Alamut Interactive Software (Interactive Biosoftware, Rouen, France), NetGene252, NNSplice53 and Human Splicing Finder54. We then compared splicing prediction data with our minigene assay results in the cases we could. The conservation of amino acids or nucleotides was represented as sequence logos using data from the ABCC8 Ensembl reference sequences of 14 different species (human, chimp, mouse, rat, cat, dolphin, cow, elephant, alpaca, platypus, chicken, zebrafish, coelacanth and lamprey) with the R package ggseqlogos55.

Minigene design

For the minigene assay we followed two different approaches. First, we amplified fragments containing the exon of interest and at least 80 bp of each flanking intronic regions. Due to the inconclusive results yielded by the standard constructs (lack of ABCC8 exons transcription in both wild type and mutated states), we increased the length of the fragments to a range between 1–1.5 kb, including multiple exons in the same construct. All the primers used for the PCR amplification are available in Supplementary Table 2. The PCR was carried out using Phusion Hot Start high fidelity polymerase (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, USA), and the cycling conditions are as follows: 98 °C for 3 min, 35 cycles of 98 °C for 10 s, each primer pair melting temperature for 45 s, 72 °C for 30 s and a last annealing step at 72 °C for 5 min. After checking the amplification with an agarose gel electrophoresis, we digested the PCR products using either XhoI/EcoRI/BamHI and NheI (NZYtech, Caparica, Portugal), so they could be subcloned into the pSPL3 vector with a T4 DNA ligase (Canvax, Córdoba, Spain) at 22 °C for 15 min using a 3:1 insert:vector ratio. Finally, we transformed NZYStar competent cells (NZYtech, Caparica, Portugal) and confirmed the cloning by PCR using each insert specific primers.

Site directed mutagenesis

The mutated constructs for each of the variants were generated using the NZYmut site directed mutagenesis kit (NZYtech, Caparica, Portugal). We carried out the reaction using 100 ng of the wild type plasmid following manufacturer’s protocol. All the primer sequences used for the reactions are indicated in Supplementary Table 2. For the fragments encoding c.1643C > T p.(Thr548Met), c.2694 + 1G > A and c.3394G > A p.(Asp1132Asn) the mutated inserts were synthesized by IDT (Coralville, Iowa, USA).

Cell culture and transfection

HeLa cells (ATCC, Manassas, USA) were cultured in DMEM (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, USA) supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, USA), 1% l-glutamine/streptomycin/penicillin (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland), at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and a humidified atmosphere. We seeded approximately 300,000 cells per well into a 6 well plate, when 80–90% confluence was achieved, we carried out the transfection using 2.5 µg of plasmid DNA and Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, USA) in a 1:3 reagent: DNA ratio per well following manufaturer’s recommendation. The wild type and mutated constructs were transfected by triplicate.

Minigene assay

We harvested the cells 36 h post-transfection, RNA was extracted using the Nucleospin RNA (Macherey–Nagel, Düren, Germany) following manufacturer’s protocol and a RT-PCR was carried out using 1 µg of RNA with the First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Canvax, Córdoba, Spain). Then, we used 2 µL of cDNA as template for a PCR using the Phusion Green Hot Start II High Fidelity polymerase (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, USA) with the SD6 5′-TCTGAGTCACCTGGACAACC-3′and SA2 5′-ATCTCAGTGGTATTTGTGAGC-3′ primers that anneal in the pSPL3 vector exons. The amplification was performed as follows: 98 °C for 3 min, 35 cycles of 98 °C for 10 s, 58 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 30 s, finally, 72 °C for 7 min. PCR products were separated by electrophoresis in a 2% agarose gel to analyze changes in pSPL3 transcript pattern, to confirm splicing alterations, we sequenced the bands using BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, USA). All the working constructs have been deposited in Addgene (Watertown, USA) pSPL3-ABCC8-2 (#135916), pSPL3-ABCC8-3 (#135917), pSPL3-ABCC8-9-10 (#135918) and pSPL3-ABCC8-27 (#135919).

ABCC8 regulation analysis

We evaluated the gene regulation network and binding motifs sequences using the UCSC genome browser56.

Protein modeling and protein stability analyses

We generated homology models for the different SUR1 variants with Phyre257. The models were then superposed with the wild type SUR1 in Chimera58. For the protein stability analysis, the models were built considering the protein structure C63O downloaded from the Protein Data Bank22 as a template (indicated by Phyre2). Next, we obtained the discrete optimized protein energy (DOPE), which provides a measure of protein folding stability59 and that is implemented in MODELLER60. When the predictors could not rule out possible splicing alterations, we simulated the effect of a whole exon skipping in the sequence (and the amino acid substitution or frameshift in the protein structure). The effects in the protein sequence were predicted by editing the reference sequence in Snapgene viewer (GSL Biotech, Chicago, USA).

For the missense variants, we used the Missense3D server61 to evaluate changes in protein conformation caused by amino acid substitution events.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank María Jesús del Cerro for the clinical data of one of the patients. We thank all the patients, nurses, clinicians and hospital workers that helped to establish REHAP. We also thank Vero and Basti from the Genomics service from the Centro de Apoio Científico-Técnico á Investigación (CACTI) of the University of Vigo.

Author contributions

M.L.D., G.P. & D.V. designed the study. M.L.D., J.T. & M.A. performed the experiments. J.A., I.G.H., C.P.O., P.E.S., A.B. & P.L. collected clinical and genetic data. M.L.D., J.A., I.G.H., M.A. & D.V. wrote the manuscript. All authors have read the draft and provided approval for publication.

Funding

This work was funded by the Cardiovascular Research Network of Instituto de Salud Carlos III de Madrid (RD06/0003/0012) FIS project PI18/01233, Actelion Pharmaceuticals, Xunta de Galicia (Centro Singular de Investigación de Galicia acreditation 2019-2022) Ref. ED431G-2019/06, Consolidación e estruturación de unidades de investigación competitivas e outras accións de fomento (ED431C 2018/54) and the European Union (European Regional Development Fund—ERDF). MLD is supported by a Xunta de Galicia predoctoral fellowship (ED481A-2018/304). MA is supported by a grant “Ramón y Cajal” (RYC-2015-18241) from the Spanish Government.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data is not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-72089-1.

References

- 1.Galiè N, et al. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2015;46:903–975. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01032-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Escribano-Subias P, et al. Survival in pulmonary hypertension in Spain: Insights from the Spanish registry. Eur. Respir. J. 2012;40:596–603. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00101211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simonneau G, et al. Hemodynamic definitions and updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2018 doi: 10.1183/13993003.01913-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lane KB, et al. Heterozygous germline mutations in BMPR2, encoding a TGF-beta receptor, cause familial primary pulmonary hypertension. Nat. Genet. 2000;26:81–84. doi: 10.1038/79226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deng Z, et al. Familial primary pulmonary hypertension (Gene PPH1) is caused by mutations in the bone morphogenetic protein receptor-II gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2000;67:737–744. doi: 10.1086/303059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans JDW, et al. BMPR2 mutations and survival in pulmonary arterial hypertension: An individual participant data meta-analysis. Lancet. Respir. Med. 2016;4:129–137. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00544-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gräf S, et al. Identification of rare sequence variation underlying heritable pulmonary arterial hypertension. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:1416. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03672-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrell NW, et al. Genetics and genomics of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2018 doi: 10.1183/13993003.01899-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bohnen MS, et al. Loss-of-function ABCC8 mutations in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ. Genom. Precis. Med. 2018;11:e002087. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGEN.118.002087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larkin EK, et al. Longitudinal analysis casts doubt on the presence of genetic anticipation in heritable pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2012;186:892–896. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201205-0886OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoeper MM, Gibbs JSR. The changing landscape of pulmonary arterial hypertension and implications for patient care. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2014;23:450–457. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00007814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quezada Loaiza CA, et al. Trends in pulmonary hypertension over a period of 30 years: Experience from a single referral centre. Rev. Española Cardiol. (English Ed.) 2017;70:901–904. doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2016.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma L, et al. A novel channelopathy in pulmonary arterial hypertension. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369:351–361. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wipff J, et al. Association of a KCNA5 gene polymorphism with systemic sclerosis-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension in the European Caucasian population. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:3093–3100. doi: 10.1002/art.27607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Navas Tejedor P, et al. An homozygous mutation in KCNK3 is associated with an aggressive form of hereditary pulmonary arterial hypertension. Clin. Genet. 2017;91:453–457. doi: 10.1111/cge.12869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pousada G, Baloira A, Vilariño C, Cifrian JM, Valverde D. Novel mutations in BMPR2, ACVRL1 and KCNA5 genes and hemodynamic parameters in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e100261. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cunningham K, et al. Characterisation and regulation of wild type and mutant TASK-1 two pore domain potassium channels indicated in pulmonary arterial hypertension. J. Physiol. 2018 doi: 10.1113/JP277275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lambert M, et al. Ion channels in pulmonary hypertension: A therapeutic interest? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:3162. doi: 10.3390/ijms19103162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Montani D, et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in familial hemiplegic migraine with ATP1A2 channelopathy. Eur. Respir. J. 2014;43:641–643. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00147013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li N, et al. Structure of a pancreatic ATP-sensitive potassium channel. Cell. 2017;168:101–110.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin GM, et al. Cryo-EM structure of the ATP-sensitive potassium channel illuminates mechanisms of assembly and gating. Elife. 2017;6:e24149. doi: 10.7554/eLife.24149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee KPK, Chen J, Mackinnon R. Molecular structure of human katp in complex with ATP and ADP. Elife. 2017;6:e32481. doi: 10.7554/eLife.32481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bellanné-Chantelot C, et al. ABCC8 and KCNJ11 molecular spectrum of 109 patients with diazoxide-unresponsive congenital hyperinsulinism. J. Med. Genet. 2010;47:752–759. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.075416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flanagan SE, et al. Update of mutations in the genes encoding the pancreatic beta-cell KATP channel subunits Kir6.2 (KCNJ11) and sulfonylurea receptor 1 (ABCC8) in diabetes mellitus and hyperinsulinism. Hum. Mutat. 2009;30:170–180. doi: 10.1002/humu.20838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bowman P, et al. Heterozygous ABCC8 mutations are a cause of MODY. Diabetologia. 2012;55:123–127. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2319-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Banerjee I, et al. The contribution of rapid KATP channel gene mutation analysis to the clinical management of children with congenital hyperinsulinism. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2011;164:733–740. doi: 10.1530/EJE-10-1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bennett JT, et al. Molecular genetic testing of patients with monogenic diabetes and hyperinsulinism. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2015;114:451–458. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2014.12.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Snider KE, et al. Genotype and phenotype correlations in 417 children with congenital hyperinsulinism. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013;98:E355–E363. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fishilevich, S. et al. GeneHancer: Genome-wide integration of enhancers and target genes in GeneCards. Database (Oxford).2017, bax028 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Hernandez-Gonzalez I, et al. Clinical heterogeneity of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension associated with variants in TBX4. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0232216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu N, et al. Novel risk genes and mechanisms implicated by exome sequencing of 2,572 individuals with pulmonary arterial hypertension. bioRxiv. 2019 doi: 10.1101/550327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baralle M, et al. NF1 mRNA biogenesis: Effect of the genomic milieu in splicing regulation of the NF1 exon 37 region. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:4449–4456. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Craig TJ, et al. An in-frame deletion in Kir6.2 (KCNJ11) causing neonatal diabetes reveals a site of interaction between Kir6.2 and SUR1. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009;94:2551–2557. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nasim MT, et al. Molecular genetic characterization of SMAD signaling molecules in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Hum. Mutat. 2011;32:1385–1389. doi: 10.1002/humu.21605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Southgate L, Machado RD, Gräf S, Morrell NW. Molecular genetic framework underlying pulmonary arterial hypertension. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2019 doi: 10.1038/s41569-019-0242-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Foster MN, Coetzee WA. K ATP channels in the cardiovascular system. Physiol. Rev. 2016;96:177–252. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00003.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miki T, et al. Defective insulin secretion and enhanced insulin action in KATP channel-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1998;95:10402–10406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koster JC, Marshall BA, Ensor N, Corbett JA, Nichols CG. Targeted overactivity of β cell K(ATP) channels induces profound neonatal diabetes. Cell. 2000;100:645–654. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80701-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flagg TP, et al. Differential structure of atrial and ventricular KATP: Atrial KATP channels require SUR1. Circ. Res. 2008;103:1458–1465. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.178186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ranchoux B, et al. Endothelial dysfunction in pulmonary arterial hypertension: An evolving landscape (2017 Grover Conference Series) Pulm. Circ. 2018;8:2045893217752912. doi: 10.1177/2045893217752912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McClenaghan C, Woo KV, Nichols CG. Pulmonary hypertension and ATP-sensitive potassium channels: Paradigms and paradoxes. Hypertension. 2019;74:14–22. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.12992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Richards S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015;17:405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu X, Wu C, Li C, Boerwinkle E. dbNSFP v3.0: A one-stop database of functional predictions and annotations for human nonsynonymous and splice-site SNVs. Hum. Mutat. 2016;37:235–241. doi: 10.1002/humu.22932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: Functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rentzsch P, Witten D, Cooper GM, Shendure J, Kircher M. CADD: Predicting the deleteriousness of variants throughout the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018 doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sim NL, et al. SIFT web server: Predicting effects of amino acid substitutions on proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:W452–W457. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Adzhubei, I., Jordan, D. M. & Sunyaev, S. R. Predicting functional effect of human missense mutations using PolyPhen-2. Curr. Protoc. Hum. Genet.Chapter 7, Unit7.20 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Inman GJ, Allday MJ. Resistance to TGF-beta1 correlates with a reduction of TGF-beta type II receptor expression in Burkitt’s lymphoma and Epstein-Barr virus-transformed B lymphoblastoid cell lines. J. Gen. Virol. 2000;81:1567–1578. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-6-1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reva B, Antipin Y, Sander C. Predicting the functional impact of protein mutations: Application to cancer genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:e118–e118. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shihab HA, et al. Predicting the functional, molecular, and phenotypic consequences of amino acid substitutions using hidden Markov models. Hum. Mutat. 2013;34:57–65. doi: 10.1002/humu.22225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Douville C, et al. Assessing the pathogenicity of insertion and deletion variants with the variant effect scoring tool (VEST-Indel) Hum. Mutat. 2016;37:28–35. doi: 10.1002/humu.22911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brunak S, Engelbrecht J, Knudsen S. Prediction of human mRNA donor and acceptor sites from the DNA sequence. J. Mol. Biol. 1991;220:49–65. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90380-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reese, M. G., Eeckman, F. H., Kulp, D. & Haussler, D. Improved splice site detection in Genie. In Proceedings of the First Annual International Conference on Computational Molecular Biology—RECOMB ’974, 232–240 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Desmet FO, et al. Human Splicing Finder: An online bioinformatics tool to predict splicing signals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:e67–e67. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wagih O. Ggseqlogo: A versatile R package for drawing sequence logos. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:3645–3647. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kent WJ, et al. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 2002;12:996–1006. doi: 10.1101/gr.229102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kelley LA, Mezulis S, Yates CM, Wass MN, Sternberg MJE. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2015;10:845–858. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pettersen EF, et al. UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shen M, Sali A. Statistical potential for assessment and prediction of protein structures. Protein Sci. 2006;15:2507–2524. doi: 10.1110/ps.062416606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Webb B, Sali A. Comparative protein structure modeling using MODELLER. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2016;2016:5.6.1–5.6.37. doi: 10.1002/cpbi.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ittisoponpisan S, et al. Can predicted protein 3D structures provide reliable insights into whether missense variants are disease associated? J. Mol. Biol. 2019;431:2197–2212. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2019.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data is not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.