Abstract

Previous research has analyzed the effect of migration on fertility, and a number of hypotheses have been developed: namely adaptation, socialization, selection, disruption and interrelation of events. Comparison among stayers in the origin countries, migrants and non-migrants in the destination country is essential to gain better understanding of the effects of migration on fertility. However, this joint comparison has been rarely conducted. We sought to fill this gap and analyze migrants’ fertility in Italy. By merging different data sources for the first time, we were able to compare our target group of migrant women, respectively, born in Albania, Morocco and Ukraine with both Italian non-migrants and stayers in the country of origin. Considering the first three orders of births, multi-process hazard models were estimated in order to provide a more exhaustive and diversified scenario and to test the existing hypotheses. The results show that there is no single model of fertility for migrants in Italy. In addition, some hypotheses provide a better explanation of the fertility behavior than others do. Among women from Morocco, the socialization hypothesis tends to prevail, whereas Albanians’ fertility is mostly explained in terms of adaptation. Disruption emerged as the main mechanism able to explain the fertility of migrants from Ukraine, and a clear interrelation between fertility and migration is apparent for women from Albania and Morocco, but only for the first birth.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10680-019-09553-w) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Migration, Fertility, Longitudinal data, Hazard regression, Birth order, Italy, Country of origin

Introduction

In the first decade of the twenty-first century, migration to Italy reached unexpected and exceptional levels, and at the beginning of 2015, the foreign residents in the country exceeded 6 million, including regular and irregular ones (Blangiardo 2016). Italy attracted a large number of economic migrants from abroad in the first decade of the twenty-first century: the factors were the economic growth of the country and a demand for labor in family-care services, in the north-central factories, and in the southern agriculture sector (Istat 2016). In recent years, the increase in foreign presence has also been linked to the rising number of births from immigrant parents (Istat 2016). Some studies have described the feminization of flows and the presence of different kinds of household (Ambrosini 2008; Bonizzoni 2007; Istat 2011; Maffioli et al. 2012; Simoni and Zucca 2007). Moreover, research has highlighted the wide variety of origins of migrants, which is often related to different migration patterns and associated with distinct reproductive behaviors (Bonifazi 2007; Mussino and Strozza 2012; Mussino et al. 2015; Ortensi 2015).

Many scholars have considered the relationship between fertility and migration also by focusing on the heterogeneity among migrants (Choi 2014; Gabrielli et al. 2007; Lübke 2015; Sobotka 2008). However, fertility patterns of migrants are compared either to the non-migrant population of the destination countries (de Valk and Milewski 2011; Glick 2010; Kulu and González-Ferrer 2014) or to stayers living in the country of origin (Baykara-Krumme and Milewski 2017). The need for a joint comparison among migrant and non-migrant women in both destination and origin countries has been widely stressed in the literature but rarely satisfied, particularly in the European context. Such comparison is essential to gain better understanding of the effects of migration on fertility. In what follows, we seek to fill this gap by focusing on the Italian case.

Due to the availability of data, we focus on Albania, Morocco and Ukraine, which have been the largest non-EU countries of origin (‘third countries’) of migrant women in recent years: the most recent register data (December 31, 2018) show that they represent, respectively, 12.1%, 11.1% and 10.4% of the total amount of resident non-EU women. By merging different data sources for the first time, we were able to compare our target group of migrant women with both Italian non-migrants and stayers in the origin country.

We adopted an ex-post merging approach consisting in assembling single datasets composed of microdata collected separately in different countries. In detail, we merged data on migrants in Italy, collected by the “Social Condition and Integration of Foreigners” survey (SCIF), with data on Italian non-migrants gathered in the multipurpose survey on “Families and Social Subjects” (FSS), and three national surveys from “Demographic and Health Surveys” (DHS) related to the behavior of stayers in the three countries of origin.

This approach can be considered one of the best strategies for a multi-site perspective (Beauchemin 2014) that seeks to go beyond “methodological nationalism” (Wimmer and Glick-Schiller 2003), i.e., the tendency to view the nation-state as the unit of analysis in mainstream social sciences. Indeed, despite the fact that migration involves by definition (at least) places of origin and destination, research has long been dominated by studies on destination countries (Beauchemin 2014).

Considering the first three birth orders, we developed multi-process hazard models in order to provide a more exhaustive and diversified scenario. We thus contribute to the international debate on the fertility of migrant women, evaluating if some of hypotheses developed in the international literature (adaptation, disruption, socialization and interrelation of events) fit the Italian case. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that light is shed on such hypotheses for the Italian case by considering different patterns of migrants’ fertility from a dynamic perspective and conducting multi-process analysis of parities.

The article is structured as follows: the next section sets out the theoretical framework and research hypotheses; the third section describes the survey data and the method of analysis; the fourth section shows macro- and micro-outcomes, whereas section five considers the results of the multi-processes analyses. Finally, sections six and seven contain, respectively, a discussion and conclusions.

Theoretical Background and Research Hypotheses

Migration Strategies and Origin Background

Among the migrants’ characteristics influencing fertility, the literature has given emphasis to the country of origin as a proxy for cultural/religious heritage and values that may be maintained after migration (Coleman 1994; Gabrielli et al. 2007; Adserà and Ferrer 2014). Persons from different geographical origins may show differences in reproductive behavior in the same country of destination (Andersson and Scott 2007; Bijwaard 2010). Distinguishing by area/country of origin makes it possible “to take the different cultural and background characteristics” (González-Ferrer et al. 2016: 3) into account as they often reveal heterogeneity in demographic characteristics and behaviors, as well as in migrant strategies.

In particular, the literature has shown how gender roles and norms in the origin country determine women’s participation in international migration, producing also different outcomes in the country of destination (Carling 2005; Hiller and McCaig 2007). Scholars have also underlined how migration among women changes dramatically between forerunners and tied migrants (Nedoluzhko and Andersson 2007; Ortensi 2015). On the one hand, first migrant women migrate with a project related to work, and childbearing can be considered only a secondary goal. On the other hand, women who migrate in order to rejoin the partner are, conversely, less (or not) subject to the trade-off between work and family. Thus, international research on migrants’ fertility has focused on the interplay between migration and the family dynamics of migrants (Landale 1997; Cooke 2008).

The importance of accounting for some measures of cultural origin to distinguish the complex path that each migrant group follows has been underscored (Adserà and Ferrer 2014), such as religion, which is often used as a proxy for the cultural background of migrants (Mayer and Riphahn 2000; Milewski 2007), and their effects on family formation patterns (Clark et al. 2009). Following a multidimensional approach, Therborn (2004, 2006) considered gender roles, national/ethnic behaviors and religious/cultural/traditional characteristics in a comprehensive interpretative paradigm. He conceptualized and described different patterns in performing family roles and responsibilities by culturally prescribed ways. This geo-cultural approach can be considered a useful interpretative key also in regard to the demographic behaviors of immigrants in their destination areas.

Migration and Fertility: Theoretical Underpinnings

By comparing the fertility of migrants and non-migrants in the areas of origin and/or in the area of destination, scholars have stressed several research hypotheses concerning the interrelationships between migration and fertility (for a review, see Milewski 2007; Kulu and González-Ferrer 2014).

The adaptation (or convergence) hypothesis suggests that the reproductive behavior of migrants may converge with that of the receiving population because of the social, political, cultural and labor market conditions in the host society (Gordon 1964; Ford 1990; Alba and Nee 1997; Carter 2000). It suggests that costs and opportunities encountered by migrants in their new environment reduce the value of high fertility for parents, and that they increase the real and opportunity costs of each additional child. The duration in the place of destination is considered a measure of exposure to the destination environment (Gordon 1964; Ford 1990; Alba and Nee 1997; Carter 2000; Ford 1990; Carter 2000), and convergence with the native population may be achieved mainly with prolongation of the stay. However, convergence does not necessarily imply a process of acculturation; it can result from adjustment strategies intended to cope with the circumstances in the new country (González-Ferrer et al. 2017; Kulu 2005; Kulu and Milewski 2007).

The socialization hypothesis relies on the assumption that the values, norms and family behaviors of migrants reflect those dominant in their childhood. It assumes that these effects continue throughout the life of a migrant, neglecting consideration of any aspect of life in the new setting (Milewski 2007; Sobotka 2008). This approach is often used to explain the relatively high levels of fertility among migrants of certain nationalities, demonstrating that they exhibit fertility patterns more similar to those of stayers in the country of origin than to those of the natives in the country of destination. Moreover, it implies that persons from different geographical origins may show differences in family behaviors in the same country of destination (Alders 2000; Kahn 1988).

The disruption hypothesis suggests that the migration itself is stressful for a person because of a drastic change in everyday life conditions and an interruption of social networks. Moreover, migration may separate spouses at least temporarily. Therefore, migrants tend to have particularly low levels of fertility immediately prior to the move and/or immediately after migration, due to the disruptive factors and difficulties related to the migration itself or to the new environment (Toulemon 2004). The recovery of fertility frequently observed shortly after migration is a process of catching up on childbearing, which was postponed or interrupted in the phase around migration (Carlson 1985; Kulu 2005; Kulu and Milewski 2007; Stephen and Bean 1992).

Conversely, other analyses have hypothesized that high fertility after migration occurs because several events take place at the same time (Mulder and Wagner 1993). This explanation is generally referred to as the interrelation of events and argues that high fertility shortly after migration is linked to family reunification or couple formation (Toulemon 2004). This approach assumes, in a life course perspective, that there is interdependence among migration, union formation and fertility (Courgeau 1989; Milewski 2007; Mulder and Wagner 1993). In particular, fertility and migration events in the life course are considered as “parallel careers.” This approach supposes that women often concentrate their reproductive period and have a higher likelihood of bearing children during the first years after migration (Andersson 2004; Lindstrom and Giorguli Saucedo 2007; Nedoluzhko and Andersson 2007; Mussino and Strozza 2012; Singley and Landale 1998).

Finally, the selection hypothesis considers the observed fertility of migrants in destination areas as a function of characteristics that migrants possess prior to migration (Borjas 1987, 1991). Migrants are not a random sample of the population in the origin areas since they constitute a selected group in terms of observed characteristics, such as educational attainment, marital status, socioeconomic resources, age, health (Feliciano 2005; Adserà and Ferrer 2015) and unobserved characteristics, like social mobility ambitions, fertility preferences and family proneness (Abbasi-Shavazi and McDonald 2000; Kulu 2005). Selectivity suggests that these observed and unobserved factors may be associated with different fertility behaviors (Hill and Johnson 2004).

Although these hypotheses have been often presented as distinct from each other, they prove to be partially complementary given that contradictory views may be supported simultaneously (Kulu 2006). For example, both the socialization and selection hypotheses emphasize the role of preferences acquired during childhood and that remain mostly unaltered despite the context. The adaptation and, to some extent, the disruption hypotheses, in contrast, predict that fertility preferences may change over the life course in response to a changing social context. Hence, these hypotheses should be considered as not mutually exclusive, given that a combination of them may help to explain the relation between migration and fertility (Goldstein and Goldstein 1984).

Research Hypotheses

Following the existing literature and according to the available data, we can formulate four general hypotheses by comparing migrant women in Italy with both stayers in the origin countries and Italian natives. In particular, we assume that:

H1 (socialization hypothesis)

This applies if the reproductive behavior of migrants and stayers in the country of origin is similar. In other words, despite the length of stay in the destination country, the likelihood of having the jth child is more similar to that of stayers in the country of origin than it is to that of Italian natives.

H2 (adaptation hypothesis)

This applies if the risk differences between migrant women and non-migrants in Italy having the jth child tend to reduce as the length of stay in the destination country increases. We expect to observe it in the long run, i.e., over several years after migration.

H3 (disruption hypothesis)

This applies if a temporary drop (i.e., in the short run) occurs in the likelihood of childbearing just a few years before and/or immediately after the migration event. Moreover, a (nonlinear) effect of time since the migration event is observed if a process of catching up on childbearing occurs in the subsequent years.

H4 (interrelation of events)

This applies if an increasing likelihood of childbearing is observed close to the event of migration, i.e., the hazard of having a child peaks only around the migration event (in particular, just after the event) and then decreases.

We considered the above-mentioned hypotheses in order to evaluate whether or not they fitted the Moroccan, Albanian and Ukrainian migrant women in Italy. Given their specific cultural/religious heritage, values and migratory strategies, we expected that the three selected groups of migrants would exhibit differences in reproductive behavior.

National data (Figure A1 in the appendix) reveal differences in the average number of children per woman (TFR), although only Moroccans continue today to have values above the replacement level and which have remained stable since the last decade (2.51 in 2014). Albanians have fallen below it (1.64 in 2014), and Ukrainians show a pattern similar to that of Italians (respectively, 1.39 and 1.50 in 2014). Childbearing has been progressively postponed in Italy. The mean age at childbearing reached 31.4 years in the period 2010–2015. Ukraine has been characterized by growing values, converging on those of Albania (respectively, 27.1 and 27.4 in 2010–2015), while Morocco records persistently high mean ages at childbearing (30.4 year). In Italy, the peak of the age-specific fertility rates is between 30 and 34 years, whereas it is clearly anticipated in the other countries, which show a similar fertility pattern up to 25 years (Figure A2 in appendix). Subsequently, Ukraine’s age-specific fertility rates remain stable at age 25–29 and declines thereafter; Albania’s rates reache the peak at age 25–29 but rapidly decreases in the next ages; Morocco’s rates continue be higher than that of the other countries from ages 30–34 to ages 45–50.

According to the Therborn (2004, 2006) scheme, the North African model is still characterized by strong patriarchal traditions, despite modernization, while the East-European model, which is very similar to the Western one, is based on gender equality within the couple and women’s economic participation in the family’s management. Thus, we expected a higher likelihood of adaptation (H2) for migrant women from Albania and Ukraine. Conversely, socialization (H1) would prevail among migrants from Morocco. In adding, different migratory strategies would determine specific fertility patterns after migration. According to previous analyses (Toulemon 2004, Gabrielli et al. 2019), Moroccan and Albanian women more often migrate for family reunification or couple formation. Consequently, they tend to have a transition to childbirth after migration (H4) more rapid than that of migrants from Ukraine, who migrate more often for work reasons and thus are at higher risk of disruption (H3).

Unfortunately, we were not able to test the selection hypothesis explicitly. We are aware that migrants may be a selected group compared to the population of origin, but there are very few tools with which to disentangle selectivity from other possible mechanisms. As we will see in the next section, the harmonized data at our disposal furnished a limited set of variables and many others factors (potentially associated with the selection, such as religion and family background) are not available. In any case, further characteristics remained unobserved (e.g., fertility preferences). Furthermore, given that we referred to retrospective data, a second source of selection was the fact that we could observe only those migrants who had decided to remain in Italy, a subgroup that could be selected twice in terms of specific patterns of integration and family formation.

Data and Methods

Our analytical strategy was based on the exploitation of three different data sources, considering women aged 15–49 at the time of the interview. Data on migrants in Italy were drawn from the Social Condition and Integration of Foreigners survey (SCIF). The SCIF survey, carried out for the first time in 2011–2012 by the Italian National Institute of Statistics (Istat), aims at providing an overview on the behaviors, characteristics, attitudes and opinions of migrants in Italy. In particular, we considered 705 women born in Albania, 530 born in Morocco, and 399 in Ukraine. Data on non-migrants in Italy were taken from the multipurpose survey on “Families and Social Subjects” (FSS) conducted by Istat in 2009, a survey which furnishes broad retrospective information on life-course trajectories, including data on family formation and fertility for a large sample of the resident population (8867 women). The behavior of individuals in the origin countries (stayers) was included through the exploitation of the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) containing data on fertility, family planning, maternal and child health for several developing countries. We considered the DHS datasets for the three observed countries. In particular, the Albanian DHS survey was conducted in 2008–2009 (and involved 7584 women), the Morocco DHS survey in 2003–2004 (16,798 women), and the Ukraine DHS survey in 2007 (6841 women). Considering the largest migrant groups in Italy, we used the data most updated at the time of performing our analyses. We selected and harmonized all the common variables deriving from the three different sources and then built a single dataset containing information on stayers in the country of origin, migrants in Italy and non-migrant in Italy. Table 1 provides a description of the sample according to the various subgroups.

Table 1.

Sample description.

Source: Our elaboration on FSS (for non-migrants in Italy), SCIF (for migrants) and DHS (for stayers in the country of departure) data

| Source | Cases | Cohorts | Occurrences (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First child | Second child | Third child | ||||

| Non-migrants Italians (FSS) | FSS 2009 | 9981 | 1960–1994 | 5177 (51.9%) | 3284 (63.4%) | 780 (23.7%) |

| Albanians in Italy (SCIF) | SCIF 2011–12 | 867 | 1961–1997 | 587 (67.7%) | 388 (66.1%) | 88 (22.7%) |

| Moroccans in Italy (SCIF) | SCIF 2011–12 | 620 | 1961–1997 | 404 (65.2%) | 299 (7.0%) | 131 (43.8%) |

| Ukrainians in Italy (SCIF) | SCIF 2011–12 | 431 | 1961–1997 | 248 (57.5%) | 103 (41.5%) | 18 (17.5%) |

| Albanians (DHS) | DHS 2008–09 | 7584 | 1958–1994 | 4817 (63.5%) | 4155 (86.3%) | 2248 (54.1%) |

| Moroccans (DHS) | DHS 2003–04 | 16,798 | 1953–1988 | 8660 (51.5%) | 7090 (81.9%) | 5369 (75.7%) |

| Ukrainians (DHS) | DHS 2007 | 6841 | 1957–1992 | 4811 (70.3%) | 2500 (52%) | 494 (19.8%) |

| Total | 43,122 | 24,704 (57.3%) | 17,819 (72.1%) | 9128 (51.2%) | ||

As a preliminary descriptive analysis, we estimated the percentages of migrant women who had a child before migration, stratified by countries of origin and parities, and the Kaplan–Meier survivor functions to the transition to the jth birth by national group and migratory status.

The multivariate analysis consisted of three steps. Firstly, we applied hazard models on the pooled dataset in order to evaluate the propensity to have a jth order child among migrants in Italy and stayers in the country of origin compared with non-migrants in Italy. Hazard models make it possible to consider not only women with a complete fertility history, but also those interviewed before the end of their reproductive age (i.e., right censored). For the transition to the first child, we considered the duration from the twelfth birthday to first birth (if any) or to the interview (right censored), and the baseline was a function of the woman’s current age. For the transition to the second (third) child, we focused on the duration between the birth of the first (second) child and the birth of the second (third) child or the interview (right-censored). In this case, the baseline was a function of the duration since the previous birth.1 It should be stressed that we look at fertility irrespective of the place of birth of the children.

Three hazard models for the first three birth orders were developed simultaneously. In other words, we applied a multi-process model with unobserved heterogeneity components at the individual level. In this way, we could control for potential bias linked to the different timing at the first birth, which may affect the second and higher birth orders (Kravdal 2001, 2002, 2007). We now explain this mechanism following Kravdal’s (2007) suggestions. Assume that non-migrant women (from a specific country) tend to have their first child at older ages compared to migrants (say, respectively, at 30 and 25 years). When we consider the hazard of second birth among mothers, we can evaluate the impact of being a migrant taking as constant (among other things) the duration since the first birth and the mother’s age at first birth. At a specific duration (say, t = 2 years), we thus compare the subgroup of non-migrants (who, having had their first child at 30 years of age, fall perfectly within the average age at first birth) with the subgroup of migrant women (who are “deviant” in the sense that their age at first birth is later than the average of the corresponding subgroup). We suppose that there is a woman-specific unobserved factor (say, ε) that is constant throughout reproductive life and that this is capable of influencing the path of first order births. Among migrants, the deviant behavior “hides” a low ε value. Therefore, if ε is not taken into account, the propensity to bear a second child at 32 years of age among non-migrants would be overestimated. A possible interpretation of this unobserved factor lying behind fertility choices may reside in the idea of “preference” for a greater or lesser number of children (Hakim 2000, 2003; Vitali et al. 2009). According to Hakim (2000), this preference develops during infancy and adolescence and varies little over the course of a woman’s reproductive life. This interpretation does not conflict with the results of other studies that—following a different perspective—assume an influence of genetic factors—that do not change over the life span—on the propensity for low or high fertility (Kohler et al. 1999; Kohler and Rodgers 2003).

This research strategy has been widely used in the literature focusing on the interrelationships between fertility and other phenomena (Kulu 2005, 2006; Kulu and Vikat 2007; Kulu and Steele 2013; Lillard 1993; Upchurch et al. 2002; Steele et al. 2005; Impicciatore and Dalla Zuanna 2017).

Formally, the models were estimated according to the three following equations:

| 1 |

where t is the duration of the episode, is the logarithm of the hazard of having the jth child at time t, and is a constant, In the first equation, A is a piecewise linear spline transformation2 of age, with nodes when the woman reached 20, 25, 30 and 35 years of age, respectively, and is the corresponding row vector of associations. In the second and third equation, D is a piecewise-linear duration spline with two nodes at 4 and 8 years after the birth of previous child. is the vector of (potentially time-varying) covariates for the jth equation, and is the corresponding vector of parameters. The unobserved heterogeneity term is assumed to be normally distributed.3 Estimation of the parameters of the model via maximum likelihood can be obtained using the aML package (Lillard and Panis 2003).

As control variables we considered: birth cohort (–1964, 1965–1969, 1970–1974, 1975–79, 1980–84, 1985–); level of education at the time of the interview (years of education standardized according to the origin country4); current enrollment in education (a dummy for being a student at the time of the interview, based on the age of leaving school); and age at previous childbirth (for the analyses on second and third childbirth), a variable that can capture the potential catch-up effect for women with postponed fertility. All these characteristics are widely considered in the literature as being among the most important determinants of fertility (Billari and Philipov 2004; Blossfeld and Huinink 1991; Goldscheider and Waite 1986; Hoem 1986; Kravdal 2007).

In the second step, we extended our multi-process hazard models to include the (nonlinear) time-varying effect of the time since migration in Italy (the categories considered were: years pre-migration, 0–3 years, 4–7 years and 8+ years after migration) on the log-hazard of having a jth child. The propensity to have a child according to the time of arrival in Italy was evaluated separately for women from Albania, Morocco and Ukraine using the (time-constant) hazard of the Italian women as a benchmark.

In the third step, we applied the multi-process model only to the subsample of migrant women (SCIF sample). Again, we included in the models the time-varying variable relating to the time since migration, but here we sought to shed light on what happens more closely to the arrival in Italy. Thus, (current) time since migration was evaluated (for the first childbirth) considering the following intervals: up to 24 months before migration, between 24 and 12, and 0–12 months before migration; 0–12, 12–24, 24–48 and 48+ months after migration. Because of a reduced number of events when analyzing the second childbirth transition, intervals were collapsed into four categories (up to 24 months before migration, 0–24 months before migration, 0–24 and 24+ months after migration) and the third childbirth was not considered.

The focus on migrants enabled us to include other relevant individual characteristics by definition available only for migrants: place of residence before migration (rural/urban), age at migration (before 20 years old, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35+ years old), reason for migration5 (employment/living conditions, family, other). We also considered the interaction between the time at migration and the reason for migration.

According to the previous research (Hoem 2014; Hoem and Nedoluzhko 2016; Hoem and Kreyenfeld 2006), estimation bias may appear in comparisons between childbearing before and after migration. In particular, the analysis of first childbearing shortly before an observed case of migration may underestimate the fertility of childless migrants in the sending country if the presence of a child hampers out-migration. By contrast, an assessment of the corresponding rate after migration correctly estimates the fertility of in-migrants in the receiving population. The main problem here is that computation of “negative durations” involves conditioning on the future, i.e., it is based on an anticipatory research strategy (Hoem and Kreyenfeld 2006). The conditional pre- and post-event approach does not let the user distinguish between, on the one hand, the bias produced by anticipatory analysis, and on the other hand, the effects of intentional behavior (Hoem 2014). In order to test the robustness of our results, we also followed a non-anticipatory procedure suggested by Hoem (2014) and Hoem and Nedoluzhko (2016). Limiting our focus to the first birth alone, we considered a state space with four possible states (childlessness, no migration; childbirth, no migration; migrated, no childbirth; both childbirth and migration) and four transitions:

to first childbirth at age x for a woman before her arrival in Italy (since her twelfth birthday);

to migration to Italy at age x instead of having a child, i.e., considered as competing risk of (a);

to migration to Italy by women who had their first childbirth at age x (since the first birth);

to first childbirth among women who migrated to Italy at age x (since the migration).

Moreover, we can also consider the transition to first childbirth at age x among women who never left their native country (on the basis, in our case, of DHS data). The intensities are assumed piecewise constant over the same time intervals of age x (in intervals: –19; 20–24; 25–29; 30+ years) and time t after migration (0–12, 12–24, 24–48 and 48+ months after migration).

Descriptive Results

In Table 2, we considered the percentages of migrant women, stratified by parities, who had children before migration. The main finding is the very high quota of migrants from Ukraine who had both the first and the second child in the country of origin (respectively, 77.3% and 70.9%). Conversely, women from Moroccans record low values in having the second and the third child (respectively, 28.0% and 26.9%). Those from Albania assume intermediate levels in all the three parities. This result is, to some extent, connected to the different age distribution of subgroups of interest. Indeed, women from Ukraine have a median age of 39 years, compared to 33 and 31 for migrants born, respectively, in Morocco and Albania.

Table 2.

Percentage migrant women in Italy who had children before migration, by parity and country origin.

Source: Our elaboration on SCIF data

| 1st birth | 2nd birth | 3rd birth | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Albania | 45.4 | 39.6 | 42.5 |

| Morocco | 41.7 | 28.0 | 26.9 |

| Ukraine | 77.3 | 70.9 | 44.4 |

| Total | 50.8 | 39.4 | 34.0 |

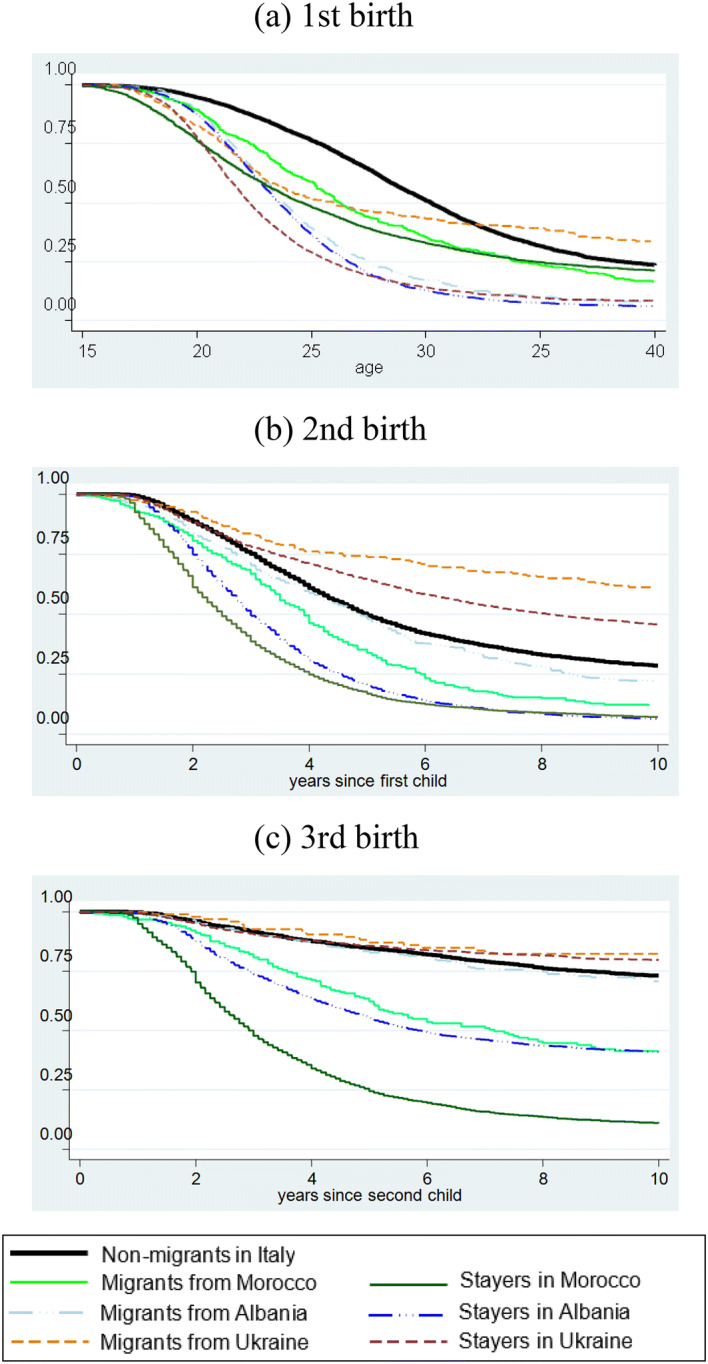

Figure 1 sets out Kaplan–Meier survivor functions to the transition to the jth birth by national group and migratory status, irrespective of the child’s country of birth.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier survivor functions to first (a), second (b) and third (c) birth by countries and migrant background.

Source: Our elaboration on FSS (for non-migrants in Italy), SCIF (for migrants) and DHS (for stayers in the country of departure) data

In the transition to the first child (Fig. 1a), migrants from Ukraine are similar to stayers in the same country at early ages, but they drastically reduce their propensity for childbearing after age 20. No significant differences in survivor functions occur between migrants and the stayers from Albania. Migrants from Morocco recover the gap with stayers after age 30. This transition to the first child for the non-migrants in Italy is clearly delayed compared to the other groups.

When focusing on the median ages at first childbirth (data not shown), no significant differences emerged between migrants from Albania and the stayers (+ 0.3 yrs. old), while the largest disparity is between migrants originating from Ukraine and the stayers (+ 3.7 yrs. old).

The transition to the second child (Fig. 1b) reveals the delaying effect of migration on fertility: the Kaplan–Meier functions of migrants are higher than those of stayers in the three countries. In particular, the pattern of migrants from Albania overlaps with that of the non-migrants in Italy. The survivor curve of migrants from Morocco reduces the gap with the function of stayers in the same country over time. Both migrants and stayers from Ukraine have the highest curves, suggesting a delayed transition and a lower intensity (also later and lower than the Italians’ one).

Looking at the transition to third child (Fig. 1c), four curves resemble each other in having the lowest percentages of women that experience this event: non-migrants in Italy, migrants and stayers from Ukraine, and migrants born in Albania. Stayers in Albania significantly anticipate the transition to the third child with respect to the migrants. Women from Morocco, particularly the stayers, have the highest hazard of experiencing the transition to the third birth.

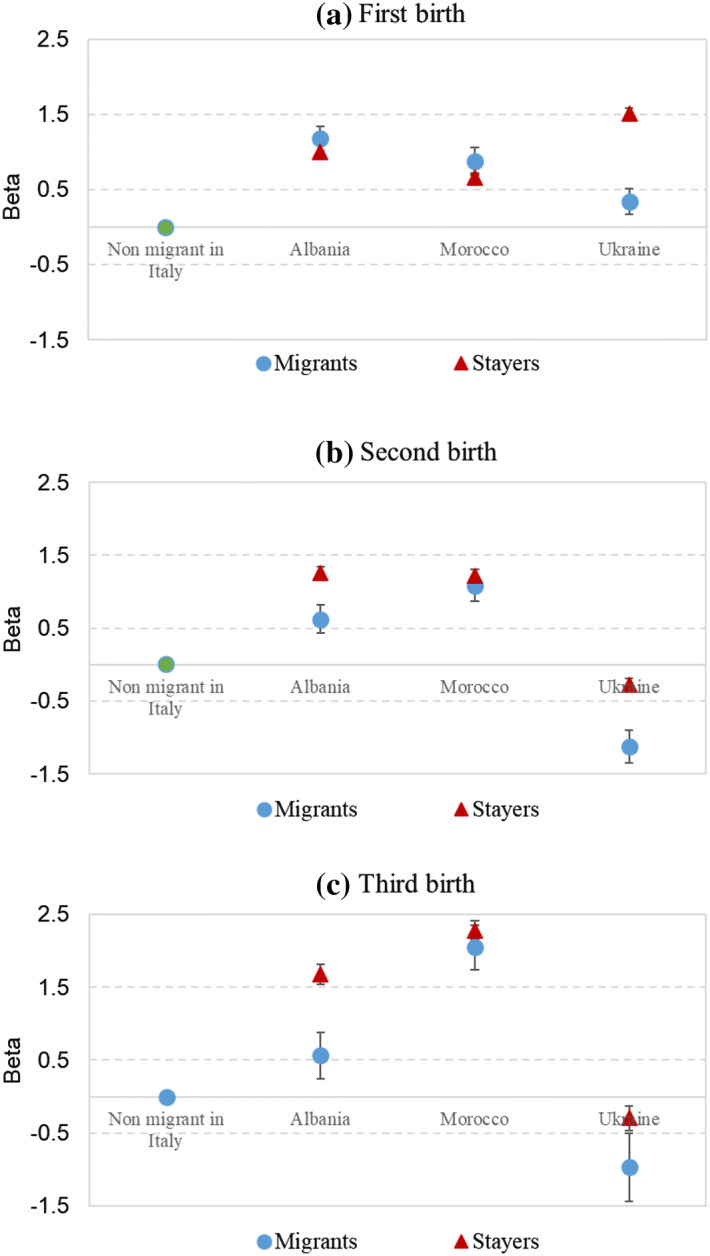

Multi-process Hazard Models

We applied simultaneous estimation of hazard models relating to the transition to the jth childbirth. Figure 2 shows the log-hazards by migration background, together with their confidence intervals (99%). Comparing the values for the transition to the first birth (Fig. 2a), women born in Morocco and Albania show a similar level regardless of whether or not they are migrants. Conversely, among those originating from Ukraine, there is a gap, with stayers clearly showing a higher propensity to have the first child compared to migrants, who are more similar to the non-migrants in Italy.

Fig. 2.

Log-hazard of having a first (a), second (b) and third birth (c) according to the country of origin and migration background. Multi-process piecewise-linear exponential models. Women aged 15–49 at the interview (complete pooled sample). Note: The reference category is “non-migrant in Italy”. 99% confidence intervals. Control factors included in the model: birth cohort; level of education at the interview; currently enrolled in education; age at previous birth (for second and third childbirth). For the complete set of estimates, see Table A1 in the appendix.

Source: Our elaboration on FSS (for non-migrants in Italy), SCIF (for migrants) and DHS (for stayers in the country of departure) data

The figures showing the transition to the second (Fig. 2b) and the third child (Fig. 2c) are similar, and both of them vary from Fig. 2a. Women from Albania are divergent according to the migration background: migrants show a lower propensity to have a second and a third child compared to stayers, approaching the non-migrant Italian pattern. The stayers and (above all) the migrants from Ukraine have a lower propensity to experience the second and the third parity events compared to the reference group. The dissimilarity between Ukrainian migrants and stayers is more significant for the first and the second child than it is for the third one, which is not surprising given the reduced size of this subgroup (see Table 1). Women from Morocco show a log-hazard that is particularly high for the third childbirth; but no clear distinction emerges between migrants and stayers: a result that is different from the KM estimates, at least for the third childbirth. This is mainly due to the diverse composition in terms of educational attainment and age at second birth. In particular, migrant women from Morocco in Italy are more educated and have the second birth later than stayers in the country of origin. Given the strong negative effect of education and mother’s age at second birth on the hazard of having the third childbirth, differences reduce substantially after having controlled for these two variables.

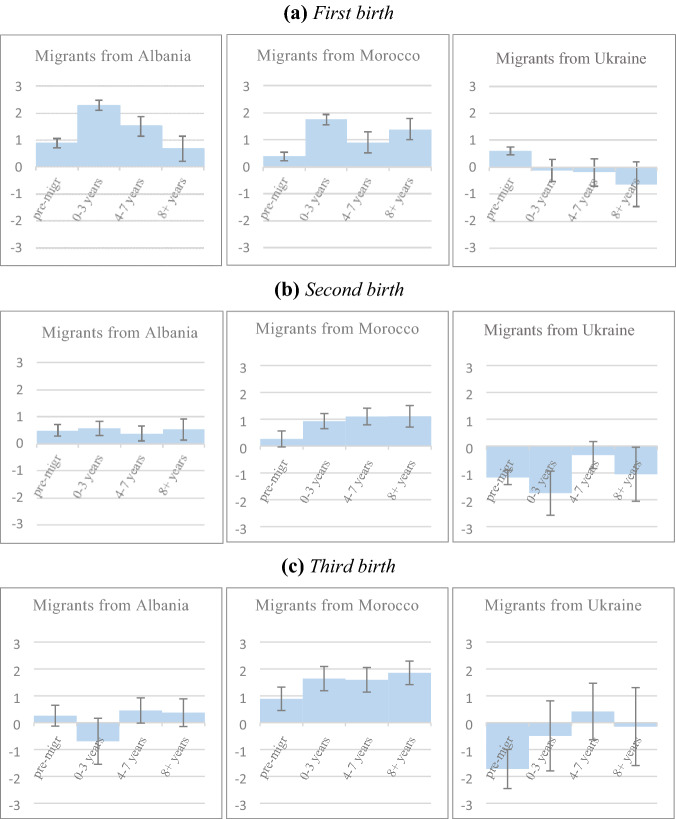

As a second step of our analysis, we considered the (time-varying) effect of the time since the arrival in Italy on the propensity to have a child according to the country of origin together with its confidence intervals (95%). We used as reference the group of Italian women whose hazard is obviously constant over time since they had not experienced any migration. The propensity to have the first child (Fig. 3a) peaks for migrants from both Albania and Morocco during the first 3 years after the arrival in Italy. However, the two groups differ in the subsequent period, since among the former this propensity declines, while among the latter it tends to recover in the long run, i.e., 8 years or more after the arrival. The hazard profile for women from Ukraine shows a decline after the arrival.

Fig. 3.

Log-hazard of having a first (a), second (b) and third birth (c) according to the country of origin and the time since the arrival in Italy (in the long run). Multi-process piecewise-linear exponential models. Migrant and non-migrant women in Italy. Note: The reference category is “non-migrant in Italy”. 95% confidence intervals. Control factors included in the model: birth cohort; level of education at the interview; currently enrolled in education; age at previous birth (for second and third childbirth). For the complete set of estimates, see Table A2 in the appendix.

Source: Our elaboration on FSS (for non-migrants in Italy) and SCIF (for migrants) data

The propensity to have a second and a third child increases after the migration among women born in Morocco, whereas it remains roughly constant for those from Albania. The small sample size prevents the drawing of specific conclusions for the Ukrainian group. However, the significant and negative difference with respect to the non-migrants in Italy tends to disappear over time.

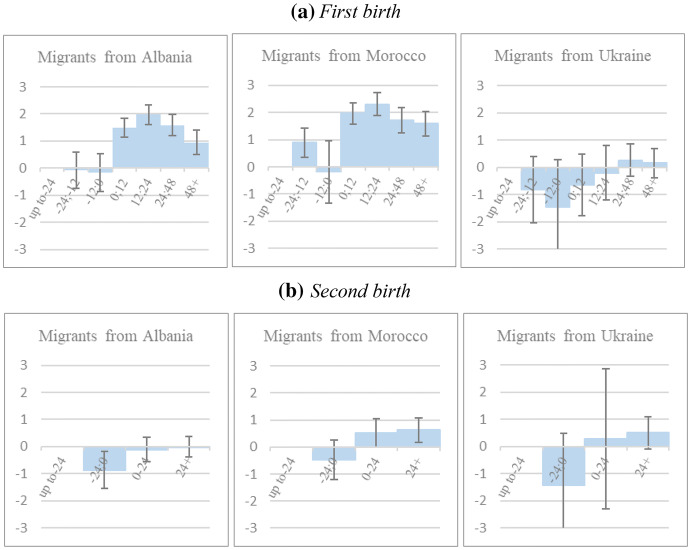

In the following step, we estimated how the propensity to have a child changes more closely to the migration event (step 3). To do so, we used a more refined definition of the time-varying variable, observing the current time since the arrival in Italy, and we considered as the reference category the interval “up to 24 months before the arrival” (Fig. 4). The hazard rate for the first birth (Fig. 4a) significantly increases among women from Morocco and Albania during the first months after the arrival, with persisting high values in the following years, in particular among those born in Morocco. Interestingly, for the Ukrainian group, an opposite pattern emerges, with a decrease in the hazard of the first childbirth just before the migration. However, in this case, the uncertainty of the estimates is very high.

Fig. 4.

Log-hazard of having a first (a) and second (b) birth according to the country of origin and the time since the arrival in Italy (in the short run). Multi-process piecewise-linear exponential models. Migrant women in Italy. Note: The reference category is “up to 24 months before the migration”. 95% confidence intervals. Control factors included in the model: birth cohort; level of education at the interview; place of living before migration (rural/urban); age at migration; currently enrolled in education; age at previous birth (for second and third child birth); migrated for family reason.

Source: Our elaboration on SCIF data

The “time-to-migration” has a less clear effect in the transition to second childbirth (Fig. 4b). We can only underline a negative risk just before the migration among migrants from Albania and a higher risk after migration for Moroccans. The small sample size precludes any significant description of patterns over time for women from Ukraine.

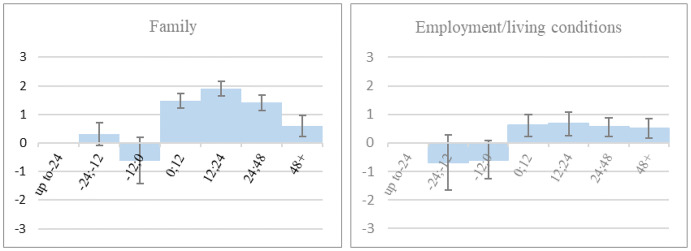

Figure 5 shows the effect of the reason for migration on the propensity to have the first child.6 If migration occurs for family reasons, the risk of having a child remains roughly stable before migration, and it increases significantly during the first and, above all, the second year after the arrival in Italy. In general, women who have migrated for employment reasons have a general lower propensity to bear children compared with family-related migrants in the 4 years after migration. These results confirm that the reasons for migration affect migrants’ childbearing in the destination country (Nedoluzhko and Andersson 2007; Ortensi 2015).

Fig. 5.

Log-hazard of having a first child according to reason for migration and time of arrival in Italy. Piecewise-linear exponential models. Migrant women in Italy. Note: The reference category is “up to 24 months before the interview”. 95% confidence intervals. Control factors included in the model: birth cohort; level of education at the interview; place of living before migration (rural/urban); age at migration; currently enrolled in education; country of origin.

Source: Our elaboration on SCIF data

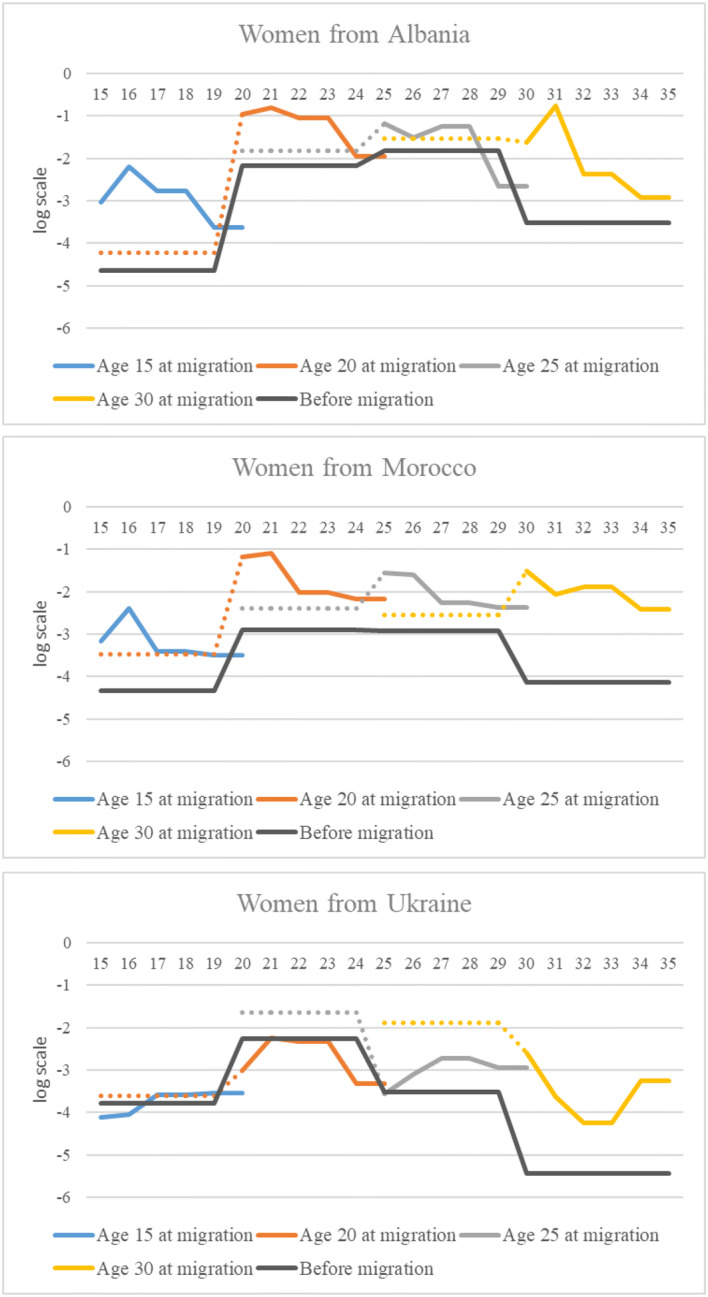

Aiming at evaluating whether the anticipatory research strategy implicitly considered in the implementation of a “negative duration,” may have caused a bias in our results, we also adopted an alternative procedure as suggested by Hoem (2014) and Hoem and Nedoluzhko (2016). The intention was to conduct estimations for different transitions separately by considering an explicit distinction between pre-migration and post-migration fertility. Figure 6 plots the hazard (measured on a log-scale) of having a first child for women before their migration to Italy and after the arrival at ages 20, 25 and 30. It also shows “negative durations” related to the fertility behavior of migrant women observed in their country of origin (dotted part of the curves). The results are fully consistent with the previous ones. There are no signs of disruption for women coming from Albania and Morocco. Instead, these two groups of migrants clearly have a higher risk at migration and in the following years, although with a decreasing trend over time, in particular among women from Albania. Interestingly, at each selected migration age x, first birth fertility is higher at and immediately after migration than it is before migration. The finding is different for women from Ukraine, who show a decreasing hazard of first childbearing at migration when they moved at the age of 25 or older. Among those who moved at 30 years of age (or later), the hazard remains lower even in the first years after migration, suggesting a disruption effect (though some caution is required in interpreting this result due to the small number of cases). Finally, no significant differences emerge among migrants (observed before and after the move) and stayers from Ukraine at younger ages.

Fig. 6.

Baseline log-hazard of having a first child after migration in Italy, for selected ages x at migration and for years t since migration, plotted by age x + t attained and extended to negative t (dotted line related to stayers women in the country of origin) compared with first childbirth hazard for migrants women before their arrival in Italy, by country of origin.

Source: SCIF (for migrants) and DHS (for stayers in the country of departure) data

Discussion

The outcomes achieved enabled us to test our research hypotheses on migrants’ fertility in Italy. The selected groups of women exhibit interesting differences in their reproductive patterns according to the country of origin, the migrant condition (being a stayer vs. being a migrant), and among migrants, the time since migration. These results validate our strategy to observe them separately in our analyses.

The fertility of migrants in Italy exhibits marked heterogeneity. Most of the Ukrainians surveyed (77.6%) experienced motherhood before their migration, while only 42.3% of the Moroccans and 46.1% of the Albanians had at least one child. Moreover, the Ukrainians have the lowest risk of parity transitions among the three migrant groups in Italy; the Albanians have the highest risk of having a first child, while Moroccans have the highest risk of experiencing the transitions to parity two and, above all, to parity three.

The migrants from the three origin countries considered are the expression of at least two different migratory models (Rossi and Strozza 2007; Bonifazi 2013; Olivito 2016). In the first classic migratory model (observed mostly among migrants from southern and eastern Mediterranean countries), men assume the role of protagonists in the process of settlement in the destination country. Within this model, the Moroccans have a large percentage of single men (more than single women) arrived for work reasons at relatively young ages, and a large percentage of Albanians are in a union at migration. Completely different is the migratory model of the female breadwinner, where the woman is the main actor of migration (observed mostly among migrants from East Europe and Latin America). Within this model, the Ukrainians have a large percentage of single women migrating for work reasons. More specifically, these women are often highly educated and have older ages at arrival in Italy and previous family histories (many of them are widowed or divorced). The results clearly confirm that migratory strategy strongly influences fertility patterns after migration.

In regard to our research hypotheses, we confirm that they differently fit the three national groups of migrants observed.

H1 (socialization hypothesis)

Moroccan migrants have patterns of childbearing similar to those in the origin country, for any birth order (net of other characteristics): the transitions to the three parities do not assume significant differences on comparing migrants and stayers. Migration has an overall delayed effect, but women from Morocco reduce the gap with the level of stayers in the native country over time. This confirms the previous research (Mussino and Strozza 2012) showing that their fertility transitions remain significantly higher than those of Italian natives; and that the risk of having a further birth does not decline over time. This pattern is well explained by the North African model, which despite the process of modernization, is characterized by strong patriarchal traditions where women are considered to be tied migrants and are less (or not) subject to the trade-off between work and family.

Also among women from Albania, we found hazard levels for the first birth that are similar between migrants and stayers in the country of origin, thus suggesting the persistence of preferences acquired in the context of departure. However, this similarity is not confirmed for the second and third childbirth, whereas, conversely, migrants exhibit a behavior that is closer to that experienced by Italian natives.

H2 (adaptation hypothesis)

Considering the effect of the time spent in the destination country in the “long run,” the risk of first childbirth among Albanian migrants clearly decreases as their length of stay in Italy increases, and it converges on the level of Italian non-migrants 4 years after arrival in Italy. This is a specific pattern not observed for the other groups of migrants. Thus, only women from Albania exhibit an adaptive pattern. They probably do so because they have a more gender egalitarian behavior within the couple, with the active participation of women in the family’s management. Conversely, women from Ukraine, even if they are generally characterized by the East-European model (Therborn 2004, 2006), achieve different outcomes mostly because of their older age at migration, their role of forerunners, and their migratory strategy (Nedoluzhko and Andersson 2007; Ortensi 2015).

H3 (disruption hypothesis)

The period of time just before the migration tends to be characterized by a depressive effect on fertility. However, only among Ukrainians, do we find a significant reduction in the hazard compared to the previous period (up to 2 years before the migration). Interestingly, this emerges more clearly among women arrived in Italy later in life, i.e., after 30 years of age. For this migrant group, the arrival in Italy is often a new opportunity for affective relationships and family life. However, it takes time to stabilize, resulting in a lower propensity to have an (additional) child.

H4 (interrelation of events)

The analysis of the “short” period around migration provides support also for the interrelation hypothesis among women from Albania and Morocco mostly in the transition to first birth. Indeed, these two migrant groups have a nonlinear hazard of first childbirth before and after migration with a peak in the second year after migration. This is line with the findings of previous studies (Mussino et al. 2015). The same does not apply to women from Ukraine. The interrelation hypothesis is less evident in the transitions to second birth (also because of the small sample size).

Finally, in accordance with our expectations, significant differences in fertility between migrants and stayers in the country of origin persist, also when controlling for a selected number of characteristics. For example, Ukrainian migrants show lower and delayed hazards compared to the stayers for any parities. Similarly, risks for migrants from Albania in having second and third child are significantly lower than for stayers in that country, but only for the second and the third child. These results may suggest that Ukrainian and Albanian migrants are somehow selected and characterized by a lower fertility preference or family proneness. Nevertheless, this may also be due to a progressive adoption of fertility behavior by the majority population. In light of previous results, this is likely to the case of Albanians, whereas we can speculate that women from Ukraine are more selected. However, our empirical evidence does not allow confirmation of this hypothesis for the reasons explained in Sect. 2.3.

Conclusions

In this paper, we compared our target group of migrant women, respectively, born in Albania, Morocco and Ukraine with both Italian non-migrants and stayers in the country of origin. The results show, for the first time in a wide and comprehensive picture, that migratory strategies and origin backgrounds as well as other individual characteristics affect fertility, and that there is no single model of fertility for migrants in Italy.

Moreover, as regards the three groups of migrants, the results can be used to test various hypotheses that provide a better explanation of the different fertility behaviors. Generally speaking, it is apparent that different mechanisms participate in definition of the overall reproductive behavior of migrants. Among women from Morocco, the socialization hypothesis tends to prevail, whereas Albanians’ fertility is mostly explained in terms of adaptation. Disruption emerged as the main mechanism able to explain the fertility of migrants from Ukraine. Moreover, a clear interrelation between fertility and migration emerged for women from Albania and Morocco, but only for the first birth.

Our analyses still have limitations. Firstly, our results do not shed light on the effects of the recent economic crisis, which has rapidly changed the patterns of migration in Italy. At individual level, the financial uncertainty has deeply influenced demographic behaviors, delaying childbearing in early adulthood. Updated data will enable inclusion of these changing patterns in future analyses. Secondly, the small number of events affects our analyses of parity three. Thirdly, the ex-post data harmonization among different data sources reduced the number of available variables that could be used as control factors in our multivariate models. This increased the probability that selection biases might emerge due to unobserved factors. Furthermore, the different retrospective surveys considered (FSS, SCIF and DHS) were not conducted in the same year, thus causing a non-perfect alignment of birth cohorts among subgroups of interest (see Table 1). Fourthly, we observed only migrants still living in Italy at the time of the interview. This group may artificially increase adaptive behavior, i.e., those who did not adopt such behavior may have been more prone to go elsewhere or return to the country of origin, thus inflating selectivity. More in general, we were not able to disentangle the effect of selectivity from the other possible mechanisms able to explain fertility behavior.

Despite these shortcomings, our analysis makes three main contributions to the existing literature. First, it yields empirical evidence on different hypotheses in Italy by merging different data sources. Second, it makes it possible to go beyond the methodological nationalism that is typical in quantitative analyses of migrants’ behaviors. Third, it provides a dynamic perspective through the application of event history techniques and multi-process analysis of parities.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Italian National Institute of Statistics (Istat) and the Demographic and Health Surveys Program (DHS) for having granted access to the microdata used in the making of this paper. The results and any errors are entirely the responsibility of the authors alone.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

All the dates were computed on a monthly scale in century month code (CMC), i.e. number of months since January 1900. In the SCIF dataset, the dates at birth of women and their children are not available and they were estimated using the information on the woman’s age at interview, the woman’s age at childbirth, and the date of the interview. This caused an inaccuracy in the episode duration. In other words, there is no single moment, but a “window” within which the event occurred. In our analysis, the uncertainty in the event date is accounted for by the two duration variables: the lower and the upper bounds of event windows (see, Lillard and Panis 2003).

Through a piecewise linear spline specification, the parameter estimates for the baseline log-hazard are slopes for linear splines over user-defined periods. With sufficient nodes (bend points), piecewise linear-specification can efficiently capture any pattern in the data (Lillard and Panis 2003).

As an additional robustness check, we relaxed the normality assumption in favor of a finite mixture distribution. The results (available on request) largely confirmed those reported in this article.

Education was considered as the number of years of attendance to achieve the highest level of education at the time of the interview. Given the marked heterogeneity among countries, we considered the years of education standardized according to the country of origin. Thus, considering four main groups, i.e. non-migrants in Italy, women born in Albania (living both in Italy and Albania), women born in Morocco, and women born in Ukraine, the standardized level of education was computed as follows: (number of years of schooling—mean of the group)/standard deviation of the same groups. In order to relax the assumption of a linear relationship between education and the likelihood of having a j-th childbirth, a quadratic term was also included in the models. By introducing this variable in the models, we assumed that those who achieve higher levels of education are, from a very early age, oriented toward accomplishing them (see e.g. Bratti and Tatsiramos 2011; Kravdal 2000). However, in this case the estimates may have been confounded by reverse causality, given that childbearing may have affected a woman’s interest in, and opportunities for, further education, thus entailing underestimation of the true causal effect (Kravdal 2004, 2007; Hoem and Kreyenfeld 2006). For example, the original education goals may be hindered by an unplanned childbirth and revised upwards in the case of unexpected childlessness (Kravdal 2001). Taking cognizance of this factor, we successfully checked the robustness of our results even when this variable was dropped from the models. However, we preferred to include in our models the education at the interview being one of the few variables at our disposal in order to (partially) take into account selection bias among migrants.

The questionnaire included the following question “What were the main reasons that led you to leave your origin country?” Among all the possible answers, we selected those related to family reasons (migrated for marriage/cohabitation/family reunification) and those related to employment and living conditions (lack of/difficulty in finding a job in the origin country; to earn higher wages; improve the quality of life). All the other possible answers (study, persecutions, war/conflicts, seeking new experiences, other reasons) were recoded as “Other.” The three, not mutually exclusive, resulting categories (work, family, other) were treated as three separate dummy variables.

The hazard was computed for all the three migrant groups without distinguishing by the country of origin. However, estimations not shown here demonstrated that the effect of the reason for migration is similar within each group.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Roberto Impicciatore, Email: roberto.impicciatore@unibo.it.

Giuseppe Gabrielli, Email: giuseppe.gabrielli@unina.it.

Anna Paterno, Email: anna.paterno@uniba.it.

References

- Abbasi-Shavazi MJ, McDonald P. Fertility and multiculturalism: Immigrant fertility in Australia, 1977–1991. International Journal of Migration. 2000;34(1):215–242. [Google Scholar]

- Adserà A, Ferrer A. Immigrants and demography: Marriage, divorce, and fertility. In: Chiswick BR, Miller PW, editors. Handbook of the economics of international migration. North Holland: Elsevier; 2015. pp. 315–374. [Google Scholar]

- Alba R, Nee V. Rethinking assimilation theory for a new Era of immigration. International Migration Review. 1997;31(4):793–1192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alders, M. (2000). Cohort fertility of migrant women in the Netherlands. Developments in fertility of women born in Turkey, Morocco, Suriname, and the Netherlands Antilles and Aruba. In Paper for the BSPS-NVD-URU Conference, 31 August–1 September. Utrecht: Statistics Netherlands.

- Ambrosini M. Séparées et réunies: Familles migrantes et liens transnationaux. Revue Européenne des Migrations Internationales. 2008;24(3):79–106. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G. Childbearing after migration: Fertility patterns of foreign-born women in Sweden. International Migration Review. 2004;38(2):747–774. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G, Scott K. Childbearing dynamics of couples in an universalistic welfare state: The role of labor market status, country of origin, and gender. Demographic Research. 2007;17(30):897–938. [Google Scholar]

- Baykara-Krumme H, Milewski N. Fertility patterns among Turkish women in Turkey and Abroad: The effects of international mobility, migrant generation, and family background. European Journal of Population. 2017;33(3):409–436. doi: 10.1007/s10680-017-9413-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchemin C. A manifesto for quantitative multi-sited approaches to international migration. International Migration Review. 2014;48(4):921–938. [Google Scholar]

- Bijwaard G. Immigrant migration dynamics model for The Netherlands. Journal of Population Economics. 2010;23(4):1213–1247. [Google Scholar]

- Billari, F.C., & Philipov, D. (2004). Education and the transition to motherhood: A comparative analysis of Western Europe. Vienna Institute of Demography. European Demographic Research, paper no. 3.

- Blangiardo GC. Gli aspetti statistici. In: Ismu F, editor. Ventunesimo Rapporto sulle migrazioni. Anno 2015. FrancoAngeli: Milano; 2016. pp. 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Blossfeld HP, Huinink J. Human capital investments or norms of role transition? How women’s schooling and career affect the process of family formation. The American Journal of Sociology. 1991;97:143–168. [Google Scholar]

- Bonifazi C. L’immigrazione straniera in Italia. Bologna: Il Mulino, Studi e Ricerche; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bonifazi C. L’ Italia delle migrazioni. Bologna: Il Mulino; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bonizzoni P. Famiglie transnazionali e ricongiunte: Per un approfondimento nello studio delle famiglie migranti. Mondi Migranti. 2007;2:91–108. [Google Scholar]

- Borjas GJ. Self-selection and the earnings of immigrants. American Economic Review. 1987;77:531–553. [Google Scholar]

- Borjas GJ. Immigration and self-selection. In: Abowd JM, editor. Immigration, trade, and the labor market. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1991. pp. 29–76. [Google Scholar]

- Bratti M, Tatsiramos K. The effect of delaying motherhood on the second childbirth in Europe. Journal of Population Economics. 2011;25(1):291–321. [Google Scholar]

- Carling J. Gender dimensions of international migration. Global Migration Perspectives. 2005;35:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson ED. The impact of international migration upon timing of marriage and childbearing. Demography. 1985;22(1):61–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter M. Fertility of Mexican immigrant women in the US: A closer look. Social Science Quarterly. 2000;81(4):1073–1086. [Google Scholar]

- Choi K. Fertility in the context of Mexican migration to the United States. Demographic Research. 2014;30(24):703–738. [Google Scholar]

- Clark RL, Glick JE, Bures RM. Immigrant families over the life course. Research directions and needs. Journal of Family Issues. 2009;30:852–872. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman DA. Trends in fertility and intermarriage among immigrant populations in Western Europe as measures of integration. Journal of Biosocial Science. 1994;26(1):107–136. doi: 10.1017/s0021932000021106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke T. Migration in a family way. Population, Space and Place. 2008;14(4):255–265. [Google Scholar]

- Courgeau D. Family formation and urbanization. Population: An English Selection. 1989;44(1):123–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Valk H, Milewski N. Family Life transitions of the second generation. Advances in Life Course Research. 2011;16(4):145–151. [Google Scholar]

- Feliciano C. Does selective migration matter? Gaining ethnic disparities in educational attainment among immigrants’ children. International Migration Review. 2005;39(4):841–871. [Google Scholar]

- Ford K. Duration of residence in the United States and the fertility of U.S. immigrants. International Migration Review. 1990;24(1):34–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrielli G, Paterno A, Strozza S. Proceeding of the International Conference on Migration and Development. Moscow: Lomonosov University; 2007. Characteristics and demographic behaviour of immigrants in different south-European contexts; pp. 336–368. [Google Scholar]

- Gabrielli G, Terzera L, Paterno A, Strozza S. Histories of couple formation and migration: The case of foreigners in Lombardy, Italy. Journal of Family Issues. 2019;40(9):1107–1125. [Google Scholar]

- Glick JE. Connecting complex processes: A decade of research on immigrant families. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72(3):498–515. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider FK, Waite LJ. Sex differences in the entry into marriage. American Journal of Sociology. 1986;92(1):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein S, Goldstein A. Inter-relations between migration and fertility: Their significance for urbanisation in Malaysia. Habitat International. 1984;8(1):93–103. [Google Scholar]

- González-Ferrer A, Castro-Martín T, Kraus EK, Eremenko T. Childbearing patterns among immigrant women and their daughters in Spain: Over-adaptation or structural constraints? Demographic Research. 2017;37(19):599–634. [Google Scholar]

- González-Ferrer A, Hannemann T, Castro-Martín T. Partnership formation and dissolution among immigrants in the Spanish context. Demographic Research. 2016;35(1):1–30. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2016.35.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon M. Assimilation in American life. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Hakim C. Work-lifestyle choices in the 21st century: Preference theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hakim C. A new approach to explaining fertility patterns: Preference theories. Population and Development Review. 2003;29(3):349–374. [Google Scholar]

- Hill L, Johnson H. Fertility changes among immigrants: Generations, neighborhoods, and personal characteristics. Social Science Quarterly. 2004;85(3):811–826. [Google Scholar]

- Hiller HH, McCaig KS. Reassessing the role of partnered women in migration decision-making and migration outcomes. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2007;24(3):457–472. [Google Scholar]

- Hoem J. The impact of education on modern family-union initiation. European Journal of Population. 1986;2:113–133. [Google Scholar]

- Hoem JM. The dangers of conditioning on the time of occurrence of one demographic process in the analysis of another. Population Studies. 2014;68(2):151–159. doi: 10.1080/00324728.2013.843019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoem JM, Kreyenfeld M. Anticipatory analysis and its alternatives in life-course research. Demographic Research. 2006;15(17):485–498. [Google Scholar]

- Hoem J, Nedoluzhko L. The dangers of using ‘negative durations’ to estimate pre- and post-migration fertility. Population Studies. 2016;70(3):359–363. doi: 10.1080/00324728.2016.1221442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Impicciatore R, Dalla Zuanna G. The impact of education on fertility in Italy. Changes across cohorts and south–north differences. Quality and Quantity: International Journal of Methodology. 2017;51(5):2293–2317. [Google Scholar]

- Istat . Rapporto Annuale. La situazione del Paese nel 2010. Rome: Istituto Nazionale di Statistica; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Istat . Rapporto annuale 2016 – La situazione del Paese. Istat: Roma; 2016. Le trasformazioni demografiche e sociali: Una lettura per generazione; pp. 39–102. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn JR. Immigrant selectivity and fertility adaptation in the United States. Social Forces. 1988;67(1):108–128. [Google Scholar]

- Kohler H-P, Rodgers JL. Education, fertility, and heritability: Explaining a paradox. In: Wachter KW, Bulatao R, editors. Offspring. Human fertility behaviour in biodemographic perspective. Washington, DC: National Academic Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler H-P, Rodgers JL, Christensen K. Is fertility behaviour in our genes? Findings from a Danish twin study. Population and Development Review. 1999;25:253–288. [Google Scholar]

- Kravdal Ø. The high fertility of college educated women in Norway: An artefact of the separate modelling of each parity transition. Demographic Research. 2001;5(6):187–216. [Google Scholar]

- Kravdal Ø. Is the previously reported increase in second- and higher-order birth rates in Norway and Sweden from the mid-1970s real or a result of inadequate estimation methods? Demographic Research. 2002;6(9):241–262. [Google Scholar]

- Kravdal Ø. Effects of current education on second- and third-birth rates among Norwegian women and men born in 1964: Substantive interpretations and methodological issues. Demographic Research. 2007;17(9):211–246. [Google Scholar]

- Kulu H. Migration and fertility: Competing hypotheses re-examined. European Journal of Population. 2005;21:51–87. [Google Scholar]

- Kulu H. Fertility of internal migrants: Comparison between Austria and Poland. Population, Space and Place. 2006;12:147–170. [Google Scholar]

- Kulu H, González-Ferrer A. Family dynamics among immigrants and their descendants in Europe: Current research and opportunities. European Journal of Population. 2014;30(4):411–435. [Google Scholar]

- Kulu H, Milewski N. Family change and migration in the life course: An introduction. Demographic Research. 2007;17:567–590. [Google Scholar]

- Kulu H, Steele F. Interrelationships between childbearing and housing transitions in the family life course. Demography. 2013;50(5):1687–1714. doi: 10.1007/s13524-013-0216-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulu H, Vikat A. Fertility differences by housing type: The effect of housing conditions or of selective moves? Demographic Research. 2007;17(26):775–802. [Google Scholar]

- Landale NS. Immigration and the family: An overview. In: Booth A, Crouter AC, Landale NS, editors. Immigration and the family: Research and policy on US immigrants. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1997. pp. 281–293. [Google Scholar]

- Lillard LA. Simultaneous equations for hazards: Marriage duration and fertility timing. Journal of Econometrics. 1993;56(1–2):189–217. doi: 10.1016/0304-4076(93)90106-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillard, L. A., & Panis, C. W. A. (2003). AML Multilevel Multiprocess Statistical Software, Release 2.0. EconWare, Los Angeles.

- Lindstrom DP, Giorguli Saucedo S. The interrelationship of fertility, family maintenance and Mexico-U.S. migration. Demographic Research. 2007;17(28):821–858. [Google Scholar]

- Lübke C. How migration affects the timing of childbearing: The transition to a first birth among polish women in Britain. European Journal of Population. 2015;31(1):1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Maffioli D, Paterno A, Gabrielli G. Transnational couples in Italy: Characteristics of partners and fertility behavior. In: Kim DS, editor. Cross-border marriage: Global trends and diversity. Seoul: Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs; 2012. pp. 279–319. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer J, Riphahn RT. Fertility assimilation if immigrants: Evidence from count data models. Journal of Population Economics. 2000;13:241–261. [Google Scholar]

- Milewski N. First child of immigrant workers and their descendants in West Germany: Interrelation of events, disruption, or adaptation? Demographic Research. 2007;17(29):859–896. [Google Scholar]

- Mulder CH, Wagner M. Migration and marriage in the life course: A method for studying synchronized events. European Journal of Population. 1993;9(1):55–76. doi: 10.1007/BF01267901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mussino E, Gabrielli G, Paterno A, Strozza S, Terzera L. Motherhood of foreign women in Lombardy: Testing the effects of migration by citizenship. Demographic Research. 2015;33(23):653–664. [Google Scholar]

- Mussino E, Strozza S. Does citizenship still matter? Second birth risks of resident foreigners in Italy. European Journal of Population. 2012;28(3):269–302. [Google Scholar]

- Nedoluzhko L, Andersson G. Migration and first-time parenthood: Evidence from Kyrgyzstan. Demographic Research. 2007;17(25):741–774. [Google Scholar]

- Olivito E, editor. Gender and migration in Italy: A multilayered perspective. New York: Routledge; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ortensi LE. Engendering the fertility-migration nexus: The role of women’s migratory patterns in the analysis of fertility after migration. Demographic Research. 2015;32(53):1435–1468. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi F, Strozza S. Mobilità della popolazione, immigrazione e presenza straniera. In: GCD-SIS, editor. Rapporto sulla popolazione. L’Italia all’inizio del XXI secolo. Bologna: Il Mulino; 2007. pp. 111–137. [Google Scholar]

- Simoni M, Zucca G, editors. Famiglie migranti. Primo rapporto nazionale sui processi d’integrazione sociale delle famiglie immigrate in Italia. Milan: FrancoAngeli; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Singley SG, Landale NS. Incorporating origin and process in migration fertility frameworks: The case of Puerto Rican women. Social Forces. 1998;76(4):1437–1464. [Google Scholar]

- Sobotka T. The rising importance of migrants for childbearing in Europe. Demographic Research. 2008;19(9):225–248. [Google Scholar]

- Steele F, Kallis C, Goldstein H, Joshi H. The relationship between childbearing and transitions from marriage and cohabitation in Britain. Demography. 2005;42:647–673. doi: 10.1353/dem.2005.0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephen EH, Bean FD. Assimilation, disruption and the fertility of Mexican-origin women in the United States. International Migration Review. 1992;26(1):67–88. [Google Scholar]

- Therborn G. Between sex and power: Family in the world 1900–2000. London: Routledge; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Therborn G, editor. African families in a global context (research report no. 131) Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Toulemon L. Fertility among immigrant women new data, a new approach. Population & Societies. 2004;400:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Upchurch DM, Lillard LA, Panis CWA. Nonmarital childbearing: Influences of education, marriage, and fertility. Demography. 2002;39:311–329. doi: 10.1353/dem.2002.0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitali A, Billari FC, Prskawetz A, Testa M-R. Preference theory and low fertility: A comparative perspective. European Journal of Population. 2009;25(4):413–438. [Google Scholar]

- Wimmer A, Glick-Schiller N. Methodological nationalism, the social sciences, and the study of migration: An essay in historical epistemology. International Migration Review. 2003;37(3):576–610. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.