Abstract

Purpose

Women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) have an increased ovarian responsiveness to exogenous recombinant follicle stimulating hormone (rFSH) but also have high rates of obesity, which is known to affect serum FSH concentrations following exogenous injection. The purpose of this study was to compare rFSH absorption and ovarian response between lean and overweight/obese PCOS subjects and normo-ovulatory controls.

Methods

Fourteen women with PCOS aged 18–42 years old with a BMI of 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 (normal) or 25.0–40.0 kg/m2 (overweight/obese) and eleven normo-ovulatory controls matched by age and BMI were included. After downregulation with oral contraceptives, participants were administered a single subcutaneous injection of 225 IU rFSH and underwent serial blood draws over 72 h.

Results

Lean PCOS subjects exhibited a significantly higher area under the curve (AUC) of baseline-corrected serum FSH over 72 h when compared with overweight/obese PCOS subjects (183.3 vs 139.8 IU*h/L, p = 0.0002), and lean, normo-ovulatory women had a significantly higher AUC FSH when compared with overweight/obese, normo-ovulatory women (193.3 vs 93.8 IU*h/L, p < 0.0001). Within overweight/obese subjects, those with PCOS had a significantly higher AUC FSH compared with normo-ovulatory controls (p = 0.0002). Lean PCOS subjects similarly had the highest AUC of baseline-corrected estradiol (6095 pg h/mL), compared with lean normo-ovulatory subjects (1931 pg h/mL, p < 0.0001) and overweight/obese PCOS subjects (2337 pg h/mL, p < 0.0001).

Conclusion

Lean PCOS subjects exhibited significantly higher baseline-corrected FSH and estradiol levels following rFSH injection compared with overweight/obese PCOS subjects with similar ovarian reserve markers. Amongst overweight/obese subjects, those with PCOS had significantly higher FSH and E2 levels when compared with normo-ovulatory controls.

Keywords: Polycystic ovary syndrome, Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics, Body mass index, Obesity, Follicle stimulating hormone

Introduction

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is one of the most common hormonal disorders affecting reproductive-aged women, with an estimated prevalence between 4 and 12% of women in their reproductive years of life [1–3]. It is a complex, multi-system reproductive-metabolic disorder characterized by anovulation, hyperandrogenism, and often obesity and insulin resistance. Notably, PCOS is the most common cause of anovulatory infertility, with as many as 74% of women with PCOS reporting infertility [4]. When treating PCOS-related infertility, the goal is induction of follicular maturation and ovulation. For women who fail first-line therapy—oral ovulation induction agents such as letrozole and clomiphene citrate—the use of exogenous gonadotropins is the mainstay of treatment in women requiring in vitro fertilization (IVF).

For years, recombinant human follicle stimulating hormone (rFSH) has been the formulation of choice due to its high biochemical purity [5, 6]. It has been demonstrated in clinical studies that women with PCOS have an increased ovarian responsiveness to exogenous FSH, with an exaggerated estradiol pharmacodynamic response when compared with healthy controls [7, 8]. This is likely due to a combination of factors, namely, the higher number of antral and pre-antral follicles in women with PCOS, as well as an increased inherent granulosa cell responsiveness to FSH, as evidenced by studies demonstrating that granulosa cells obtained from women with PCOS exhibit a significantly greater rise of estradiol following FSH stimulation compared with that observed in granulosa cells of ovulatory women [9].

PCOS-related infertility in many women is also complicated by high rates of obesity; approximately 60% of PCOS women in the USA have an obese body mass index (BMI) [10]. Separate studies, which have excluded women with PCOS, have demonstrated that overweight and obese women require higher doses of FSH to achieve similar maximal serum concentrations as normal-weight women, likely due to the increased volume of distribution in women with an increased body mass [11]. It is generally accepted in clinical practice that higher doses of gonadotropins are needed for ovulation induction in obese patients in order to address the inverse relationship between FSH serum concentrations and body mass, although there is no consensus on the treatment of obese women with PCOS who may have an inherently exaggerated response to FSH and higher ovarian reserve markers.

The mechanisms underlying the interplay of ovarian and granulosa cell responsiveness with the effect of adiposity on FSH absorption and metabolism, within the framework of the complex metabolic syndrome of PCOS, are poorly understood. To our knowledge, no prior studies have compared the pharmacokinetics of rFSH between lean and overweight/obese women with PCOS to normo-ovulatory controls. In this study, we aimed to determine whether there are differences in the absorption and pharmacokinetic parameters of rFSH, or ovarian responses to rFSH, between lean and overweight/obese PCOS and normo-ovulatory women in age and BMI-matched subgroups, to elucidate whether PCOS or obesity has the greater impact.

Methods

Study participants

Women aged 18–42 years old were eligible to participate. Participants were required to have a BMI categorized as either normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2) or overweight/obese (over 25.0 kg/m2). An upper BMI cutoff of 40.0 kg/m2 was chosen because many infertility programs in the USA do not accept women with class 3 obesity for treatment. Participants were classified as either having polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), defined as having at least two out of three of the revised Rotterdam criteria [12]—(1) oligo- or anovulation, (2) clinical and/or biochemical signs of hyperandrogenism, and (3) polycystic ovaries by transvaginal ultrasound (> 12 antral follicles in one ovary)—or as normo-ovulatory, with a history of regular menstrual periods (every 21 to 35 days, with cycle-to-cycle variability of less than 1 week).

Participants with PCOS were initially recruited, and these participants were matched to normo-ovulatory control participants by age (± 4 years) and BMI (± 3 kg/m2) in a 1:1 fashion. Study participants were categorized into one of four groups: PCOS with a normal BMI, PCOS with overweight/obese BMI, normo-ovulatory with normal BMI, and normo-ovulatory with overweight/obese BMI. Women who were currently pregnant or breastfeeding, peri- or post-menopausal, or reported a history of stroke, coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, thrombophlebitis, adrenal insufficiency, diabetes, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, uncontrolled hypertension, or active thromboembolic disease were ineligible. Those with kidney or liver disease were also excluded as FSH is renally and hepatically cleared from circulation [5]. Current smoking, heavy alcohol use, illicit drug use, and recent hormone use within 30 days were also exclusion criteria. Participants were required to have prior exposure to estrogen-containing contraceptives without serious adverse reactions to be eligible. Study participants were recruited using the Partners Healthcare Rally for Research volunteer program, as well as via advertisements in free local online media. Recruitment began in October of 2014 and concluded December 2018 (on hiatus June 2016 through January 2018 due to changes in study personnel).

Study design and procedures

Initial eligibility screening took place via structured telephone interviews. Eligible subjects then presented for an in-person screening visit and intake, which consisted of a physical examination, brief medical questionnaire, urine hCG testing, baseline laboratory studies, and transvaginal ultrasound examination. For normo-ovulatory women, the initial screening visit occurred during the early follicular phase (days 2–5 of the menstrual cycle), and for PCOS women, the initial visit occurred at random in the absence of regular menses. Baseline laboratory studies at the screening visit were comprised of serum 17-hydroxyprogesterone to exclude late-onset congenital adrenal hyperplasia (using a cutoff of 3 ng/mL), DHEA-S, testosterone, hemoglobin A1c to exclude diabetes mellitus (using a cutoff of 6.4%), and fasting insulin. Participants who were on hormone-containing medications at the time of the initial phone screening underwent a washout period of at least 1 month prior to the screening visit.

Eligible research participants then were started on an oral contraceptive pill (Apri, 150 μg desogestrel and 30 μg ethinyl estradiol, Teva Pharmaceuticals) during the early follicular phase, which they continued for 2–3 weeks until 4 days prior to scheduled research admission. Participants were then admitted to the Harvard Catalyst Clinical Research Center (HCCRC) inpatient unit at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH). Urine pregnancy tests were performed again upon admission and confirmed to be negative. Subcutaneous injection of 225 IU of Gonal-f was administered by an HCCRC registered nurse in the lower abdominal area in a standardized fashion, 4 cm lateral to the halfway point between the pubic symphysis and the umbilicus, and a transabdominal ultrasound was performed by study staff at the injection site to determine the total depth of the subcutaneous fat.

Serial blood samples were taken immediately prior to and 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 16, and 24 h after the FSH injection via an indwelling IV catheter. Study participants remained in the HCCRC for the duration of this portion of the study and were discharged after the 24-h blood draw. During the admission, each participant’s hydration status and body fat composition were formally evaluated by a BWH staff nutritionist using a bioelectrical impedance analysis, which was completed using the Quantum II BIA analyzer (RJL Systems, Clinton Township, MI). Following the admission, study participants returned to the outpatient Center for Clinical Investigation for blood draws via conventional venipuncture at 48 and 72 h post-FSH injection. Samples were immediately processed by the HCCRC laboratory, and aliquots of serum from each specimen were reserved. Samples were frozen at − 80 °C to avoid degradation until assays were run.

Sample analysis

The following serum samples were evaluated for steroid hormones through the Brigham Research Assay Core laboratory (Boston, MA). Serum follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and estradiol (E2) from each time point (baseline and 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 16, 24, 48, and 72 h after injection) were measured using electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (ECLIA) (assays manufactured by Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA). For FSH, the intra-assay variation was 3.1–4.3%, and the inter-assay variation was 4.3–5.6%. For estradiol, the intra-assay variation was 2.0–4.2% and the inter-assay variation was 3.1–5.6%. Progesterone was measured at baseline by ECLIA (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA; intra-assay variation 6.11–11.19%, inter-assay variation 6.59–9.57%), as was dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S; Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA; intra-assay variation 1.6–8.3%, inter-assay variation 3.7–11.3%), and sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG; Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA; intra-assay variation 4.5–4.8%, inter-assay variation 5.2–5.5%). Luteinizing hormone (LH) was measured at baseline and 24 h after injection by ECLIA (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA; precision of 4.3–6.4%). Anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) at baseline (Ansh Labs, Webster, TX; intra-assay variation 2.3–4.5%, inter-assay variation 2.1–3.7%). Testosterone was measured at baseline, 24 and 72 h after injection by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS; intra-assay variation below 4%, inter-assay variation below 5%).

Androstenedione and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) concentrations were evaluated at baseline, 24 and 72 h after injection by LC-MS/MS (intra-assay variation 6.23% and 4.6%, respectively) by Assay Services at the Wisconsin National Primate Research Center (Madison, Wisconsin). All samples were run in a single batch to decrease inter-assay variation.

Power calculation

A prior study demonstrated a 39.5% higher maximal concentration and 31.8% higher area under the curve of estradiol following an IV bolus of rFSH in women with PCOS when compared with normal ovulatory controls after IV injection of the same medication [8]. Assuming a difference between the PCOS control groups of 25% and standard deviation of 10%, a sample size of n = 5 subjects per group was required. All calculations assumed a type I error probability of 0.05 and 80% power. To allow for the most conservative sample size calculation as well as potential dropout, we aimed to recruit 7 women in each group for a total of 28 subjects.

Statistical analysis

A visual inspection of the data was performed to assess for normality. Data were not normally distributed, and this was confirmed by applying the Shapiro-Wilks test to the main outcomes (FSH, estradiol). Thus, non-parametric tests were used for all comparisons. Paired comparisons of pharmacokinetic parameters and steroid hormone response following the subcutaneous FSH injection were performed using Wilcoxon rank sum tests. For categorical variables, chi-square tests were performed, except in cases in which cell sizes were fewer than five, and Fisher exact test was used.

In order to adjust for inter-individual baseline differences in endogenous FSH and E2, time 0 values, the endogenous FSH and E2 levels in a subject, were subtracted from levels obtained after rFSH administration, as has been done in prior pharmacokinetic studies [13]. Areas under the curve for the baseline-corrected serum concentrations of follicle stimulating hormone and estradiol following the injection of rFSH were calculated using GraphPad Prism 8 (San Diego, California).

Results

One hundred thirty-two women responded to recruitment efforts and underwent initial phone screening. Of these, ninety-eight women either were disqualified based on the phone screen or declined participation after the study was further described in detail. The remaining 34 women presented for the initial screening study visit and were enrolled. Of the enrolled participants, nine were either found to be ineligible at the time of screening or declined further participation. The remaining 25 eligible women completed the study (7 lean/normal-weight PCOS, 7 overweight/obese PCOS, 6 lean/normal-weight normo-ovulatory, and 5 overweight/obese normo-ovulatory). Of note, all women were in the follicular phase at admission except one participant in the overweight/obese, normo-ovulatory control group, as demonstrated by a progesterone level of 8.49 ng/mL. Results were not significantly changed when this participant was excluded (data not shown).

The demographic and baseline characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. Participants in the PCOS group had a mean age of 27.1 years and mean BMI of 27.4 kg/m2. The normo-ovulatory group had a mean age of 27.4 and BMI of 26.3 kg/m2. There was no significant difference in age between PCOS and normo-ovulatory, lean and overweight/obese, or any of the subgroups. Participants in the normal weight group had an average BMI of 22.6 kg/m2, whereas participants in the overweight/obese group had an average BMI of 31.7 kg/m2. BMI was significantly higher in the overweight/obese PCOS and overweight/obese normo-ovulatory subgroups when compared with their lean counterparts. All women were nulliparous. PCOS subjects overall had no significant differences in baseline or demographic characteristics compared with their normo-ovulatory controls. When comparing normal weight with overweight/obese women, normal weight women had significantly lower BMIs, waist-to-hip ratios, total body fat percentages, and subcutaneous thickness at the injection site of FSH.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics of study population

| PCOS (n = 14) | Normo-ovulatory (n = 11) | Normal weight (n) | Overweight/obese (n) | p value (< 0.05) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 13) | PCOS (n = 7) | Normo-ovulatory (n = 6) | All (n = 12) | PCOS (n = 7) | Normo-ovulatory (n = 5) | ||||

| Age (years)* | 27.1 (4.4) | 27.4 (3.7) | 26.5 (2.9) | 26.6 (3.4) | 26.4 (2.6) | 26.5 (2.9) | 27.5 (5.4) | 28.6 (4.8) | |

| BMI* | 27.4 (6.0) | 26.3 (4.8) | 22.6 (1.8) | 22.4 (1.6) | 22.7 (2.1) | 31.7 (3.6) | 32.4 (4.1) | 30.7 (3.1) | b, d, e |

| Race† | |||||||||

| White | 6 (42.9) | 7 (63.6) | 8 (61.5) | 4 (57.1) | 4 (66.7) | 5 (41.7) | 2 (28.6) | 3 (60.0) | |

| Asian/PI | 3 (21.) | 2 (18.2) | 3 (23.1) | 1 (14.3) | 2 (33.3) | 2 (16.7) | 2 (28.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| AA/Black | 1 (7.1) | 2 (18.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (25.0) | 1 (14.3) | 2 (40.0) | |

| Hispanic | 4 (28.6) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (15.4) | 2 (28.6) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (16.7) | 2 (28.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Waist to hip ratio* | 0.86 (0.09) | 0.80 (0.04) | 0.79 (0.04) | 0.79 (0.01) | 0.79 (0.04) | 0.88 (0.08) | 0.93 (0.07) | 0.82 (0.04) | b, d |

| Total body fat percentage* | 36.1 (10.9) | 32.0 (8.0) | 28.1 (5.0) | 29.1 (5.0) | 27.0 (4.7) | 40.9 (9.4) | 43.0 (10.9) | 38.0 (6.9) | b, d |

| Subcutaneous thickness (mm)* | 21.5 (18.0) | 15.2 (9.8) | 8.3 (2.6) | 7.7 (1.8) | 9.0 (3.4) | 30.8 (14.1) | 37.6 (13.9) | 22.6 (10.0) | b, d |

*Expressed as mean (SD)

†Expressed as number (%)

aStatistically significant at alpha < 0.05 between all PCOS and all normo-ovulatory

bStatistically significant at alpha < 0.05 between all normal weight and all overweight/obese

cStatistically significant at alpha < 0.05 between normal weight PCOS and normal weight normo-ovulatory

dStatistically significant at alpha < 0.05 between normal weight PCOS and overweight/obese PCOS

eStatistically significant at alpha < 0.05 between normal weight normo-ovulatory and overweight/obese normo-ovulatory

fStatistically significant at alpha < 0.05 between overweight/obese PCOS and overweight/obese normo-ovulatory

Table 2 demonstrates the basal endocrine-metabolic analyte values of the study population, either obtained at the initial screening visit (17-OHP, DHEA-S, total testosterone, fasting insulin, and hemoglobin A1c; antral follicle count and endometrial thickness by transvaginal ultrasound) or the study visit at time 0 prior to the FSH injection and after two to 3 weeks of oral contraceptive use (AMH). PCOS subjects differed from normo-ovulatory women in their markers of ovarian reserve (higher antral follicle counts and AMH levels) and had higher DHEA-S, total testosterone, and A1c at screening when compared with normo-ovulatory women. Lean women had lower fasting insulin at screening when compared with overweight/obese women. Three women in the overweight cohort (two with PCOS, one normo-ovulatory) had a hemoglobin A1c in the prediabetes range.

Table 2.

Mean basal endocrine-metabolic values in PCOS vs. normo-ovulatory, and normal-weight vs. overweight/obese subjects; expressed as mean (SD)

| PCOS (n = 14) | Normo-ovulatory (n = 11) | Normal weight (n = 13) | Overweight/obese (n = 12) | p value (< 0.05) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 13) | PCOS (n = 7) | Normo-ovulatory (6) | All (n = 12) | PCOS (n = 7) | Normo-ovulatory (n = 5) | ||||

| Antral follicle count | 43.9 (14.2) | 20.6 (7.5) | 31.5 (18.9) | 42.3 (19.3) | 19.0 (7.5) | 35.3 (13.7) | 45.8 (5.5) | 22.6 (7.8) | a, c, f |

| Endometrial hickness (mm) | 6.3 (2.0) | 5.2 (2.0) | 6.0 (2.3) | 6.8 (2.4) | 5.1 (2.0) | 5.5 (1.8) | 5.7 (1.5) | 5.2 (2.2) | |

| AMH (ng/mL)* | 10.3 (6.2) | 4.7 (3.0) | 7.2 (6.1) | 9.9 (7.1) | 4.0 (2.6) | 8.5 (5.3) | 10.6 (5.6) | 5.6 (3.5) | a |

| 17-OHP (ng/dL) | 70.4 (48.2) | 50.2 (42.3) | 65.4 (58.5) | 76.9 (56.9) | 39.3 (8.1) | 63.3 (49.0) | 63.9 (41.3) | 62.6 (63.5) | |

| DHEA-S (μg/dL) | 236.1 (168.4) | 131.3 (55.5) | 164.8 (68.2) | 180.7 (74.9) | 146.2 (60.5) | 217.3 (189.3) | 291.6 (220.6) | 113.4 (48.7) | a |

| Total testosterone (ng/dL) | 50.3 (22.4) | 28.4 (9.7) | 35.3 (15.5) | 40.7 (17.7) | 29.0 (10.4) | 46.4 (24.9) | 59.9 (23.8) | 27.6 (9.9) | a, f |

| Fasting insulin (uIU/mL) | 11.5 (9.2) | 8.4 (4.5) | 6.3 (1.9) | 6.2 (2.1) | 6.4 (1.9) | 14.3 (9.1) | 16.8 (10.6) | 10.8 (5.8) | b, d |

| Hemoglobin A1c (%) | 5.4 (0.3) | 5.1 (0.4) | 5.2 (0.3) | 5.3 (0.3) | 5.0 (0.2) | 5.3 (0.4) | 5.4 (0.4) | 5.2 (0.5) | a |

*Drawn at study admission visit at time 0; all other measurements/analytes obtained at initial screening visit

aStatistically significant at alpha < 0.05 between all PCOS and all normo-ovulatory

bStatistically significant at alpha < 0.05 between all normal weight and all overweight/obese

cStatistically significant at alpha < 0.05 between normal weight PCOS and normal weight normo-ovulatory

dStatistically significant at alpha < 0.05 between normal weight PCOS and overweight/obese PCOS

eStatistically significant at alpha < 0.05 between normal weight normo-ovulatory and overweight/obese normo-ovulatory

fStatistically significant at alpha < 0.05 between overweight/obese PCOS and overweight/obese normo-ovulatory

Table 3 demonstrates additional mean endocrine values of the study population drawn at study visit time 0, immediately prior to FSH injection and following 2–3 weeks of suppression on oral contraceptives. PCOS subjects had higher levels of androstenedione and DHEA than normo-ovulatory controls. While the testosterone levels of PCOS subjects were higher than that of the normo-ovulatory controls, this did not reach statistical significance as it did at the screening visit. Overweight/obese women had significantly lower SHBG levels than lean women.

Table 3.

Mean endocrine values in PCOS vs. normo-ovulatory, and normal-weight vs. overweight/obese subjects, drawn at study visit time 0 immediately prior to SC rFSH injection; expressed as mean (SD)

| Analyte | PCOS (n = 14) | Normo-ovulatory (n = 11) | Normal weight (n = 13) | Overweight/obese (n = 12) | p value (< 0.05) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 13) | PCOS (n = 7) | Normo-ovulatory (6) | All (n = 12) | PCOS (n = 7) | Normo-ovulatory (n = 5) | ||||

| LH (IU/L) | 4.8 (3.8) | 3.3 (2.6) | 3.1 (2.1) | 4.1 (2.1) | 4.7 (3.3) | 4.1 (4.1) | 5.4 (5.0) | 2.3 (1.3) | |

| FSH (IU/L) | 4.6 (2.4) | 5.6 (4.6) | 5.0 (4.6) | 4.2 (2.9) | 5.9 (6.2) | 5.1 (2.0) | 5.0 (1.8) | 5.4 (2.5) | |

| Estradiol (pg/mL) | 44.7 (16.6) | 40.9 (35.1) | 39.8 (21.2) | 47.1 (20.4) | 31.4 (20.5) | 36.5 (30.7) | 42.4 (13.0) | 52.3 (47.6) | |

| Progesterone (ng/mL) | 0.5 (0.3) | 1.2 (2.4) | 0.5 (0.2) | 0.6 (0.3) | 0.4 (0.1) | 1.2 (2.3) | 0.5 (0.4) | 2.2 (3.5) | |

| DHEA-S (μg/dL) | 236.1 (168.4) | 131.3 (55.5) | 164.8 (68.2) | 180.7 (74.9) | 146.2 (60.5) | 217.3 (189.3) | 291.6 (220.6) | 113.4 (48.7) | |

| Total Testosterone (ng/dL) | 33.2 (7.7) | 24.4 (8.4) | 34.9 (14.6) | 37.9 (15.9) | 31.4 (13.5) | 29.5 (8.9) | 33.2 (7.8) | 24.4 (8.4) | |

| Androstenedione (ng/mL) | 1.0 (0.4) | 0.6 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.4) | 1.1 (0.4) | 0.6 (0.2) | 0.7 (0.3) | 0.9 (0.3) | 0.5 (0.1) | a, f |

| DHEA (ng/mL) | 3.9 (4.3) | 1.6 (1.7) | 3.2 (4.0) | 4.1 (5.1) | 2.1 (2.2) | 2.6 3.1) | 3.7 (3.7) | 1.0 (0.4) | a, f |

| SHBG (nmol/L) | 118.3 (44.9) | 134.6 (36.9) | 148.1 (38.6) | 148.4 (37.8) | 147.6 (46.1) | 103.2 (33.1) | 88.2 (28.9) | 124.1 (28.7) | b, d |

aStatistically significant at alpha < 0.05 between all PCOS and all normo-ovulatory

bStatistically significant at alpha < 0.05 between all normal weight and all overweight/obese

cStatistically significant at alpha < 0.05 between normal weight PCOS and normal weight normo-ovulatory

dStatistically significant at alpha < 0.05 between normal weight PCOS and overweight/obese PCOS

eStatistically significant at alpha < 0.05 between normal weight normo-ovulatory and overweight/obese normo-ovulatory

fStatistically significant at alpha < 0.05 between overweight/obese PCOS and overweight/obese normo-ovulatory

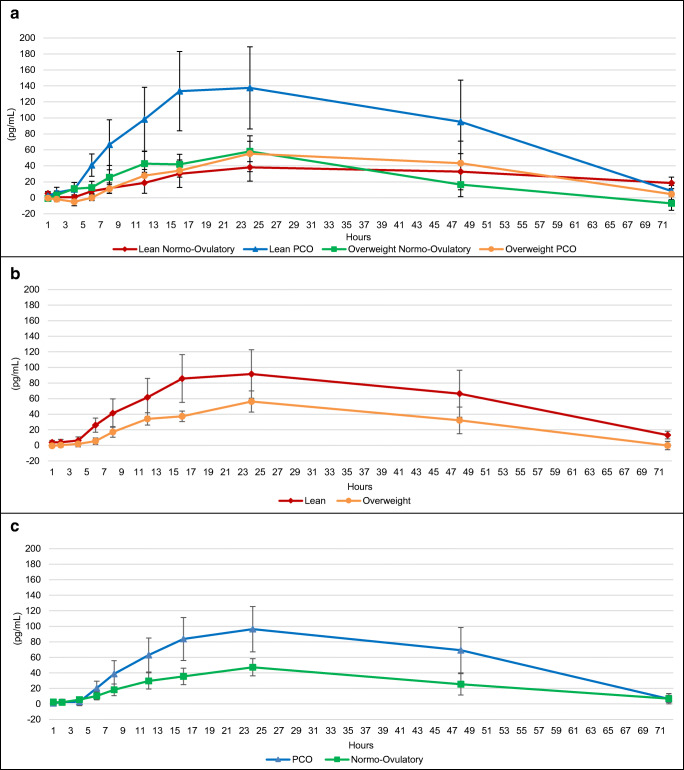

The mean baseline-corrected concentration-time profiles of serum FSH following the subcutaneous FSH injection are shown in Fig. 1–c, and pharmacokinetic parameters are shown in Table 4. Lean women exhibited significantly higher peak serum concentration over baseline (Cmax) of FSH when compared with overweight/obese women (p = 0.01). There was no difference in Cmax of FSH when comparing PCOS and normo-ovulatory subjects. There was no difference between subgroups in the time to maximal baseline-corrected FSH (Tmax) or the proportion of women who reached Cmax by the 12-h or 24-h time points after FSH injection. Lean women demonstrated a significantly higher area under the curve (AUC) of baseline-corrected FSH over 72 h when compared with overweight/obese women (187.9 vs 120.6 IU*h/L, p < 0.0001). Similarly, lean PCOS subjects had a significantly higher AUC0–72 of baseline-corrected FSH when compared with overweight/obese PCOS subjects (183.3 vs 139.8 IU*h/L, p = 0.0002), and lean, normo-ovulatory women had a significantly higher AUC0–72 of baseline-corrected FSH when compared with overweight/obese, normo-ovulatory women (193.3 vs 93.8 IU*h/L, p < 0.0001). Of women in the overweight/obese group, those with PCOS had significantly higher AUC0–72 of baseline-corrected FSH when compared with normo-ovulatory women (139.8 vs 93.8 IU*h/L, p = 0.0002), but there was no difference between PCOS and normo-ovulatory women in the lean subgroup. When comparing overweight/obese PCOS subjects with lean normo-ovulatory controls, the latter had a significantly higher AUC0–72 of baseline-corrected FSH (139.8 vs 193.3 IU*h/L, p = 0.03).

Fig. 1.

a Baseline-corrected change in FSH (IU/L) by subgroup. b Baseline-corrected change in FSH (IU/L) by BMI (lean versus overweight/obese). c Baseline-corrected change in FSH (IU/L) by ovulatory status (PCOS versus normo-ovulatory). Data presented as mean + SEM

Table 4.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of baseline-corrected concentrations of FSH and estradiol after SC rFSH injection in PCOS vs. normo-ovulatory, and normal-weight vs. overweight/obese subjects*

| PCOS (n = 14) | Normo-Ovulatory (n = 11) | Normal weight (n = 13) | Overweight/obese (n = 12) | p value (< 0.05)† | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 13) | PCOS (n = 7) | Normo-ovulatory (6) | All (i = 12) | PCOS (n = 7) | Normo-ovulatory (n = 5) | ||||

| Baseline-corrected concentration of FSH | |||||||||

| Tmax (h) | 16.4 (11.4) | 18.7 (12.1) | 15.9 (11.7) | 11.7 (5.9) | 20.7 (15.3) | 19.2 (11.6) | 21.1 (14.0) | 16.4 (7.8) | |

| Tmax by 12 h (%) | 9 (64.3) | 5 (45.5) | 9 (69.2) | 6 (85.7) | 3 (50.0) | 5 (41.7) | 4 (42.9) | 2 (40.0) | |

| Tmax by 24 h (%) | 13 (92.9) | 10 (90.9) | 12 (92.3) | 7 (100.0) | 5 (83.3) | 11 (91.7) | 6 (85.7) | 5 (100.0) | |

| Cmax (IU/L) | 5.5 (2.9) | 5.5 (3.3) | 6.9 (2.7) | 6.6 (2.1) | 7.2 (3.5) | 4.0 (2.7) | 4.3 (3.3) | 3.5 (1.7) | b |

| AUC0–72 (IU*h/L) | 161.5 (61.7) | 148.1 (116.8) | 187.9 (109.7) | 183.3 (59.1) | 193.3 (156.2) | 120.6 (61.0) | 139.8 (67.5) | 93.8 (53.6) | b, d, e, f |

| Baseline-corrected concentration of estradiol | |||||||||

| Tmax (h) | 25.9 (15.6) | 36.0 (22.8) | 35.5 (21.8) | 26.0 (16.2) | 46.7 (23.4) | 24.7 (15.3) | 25.7 (16.3) | 23.2 (15.6) | |

| Tmax by 12 h (%) | 3 (21.4) | 2 (18.2) | 1 (7.7) | 1 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (33.3) | 2 (28.6) | 2 (40.0) | |

| Tmax by 24 h (%) | 10 (71.4) | 6 (54.5) | 7 (53.8) | 5 (71.4) | 2 (33.3) | 9 (75.0) | 5 (71.4) | 4 (80.0) | |

| Cmax (pg/mL) | 115.5 (127.4) | 58.5 (41.8) | 113.6 (131.6) | 166.8 (158.2) | 51.4 (53.6) | 65.3 (48.9) | 64.1 (63.1) | 67.0 (25.7) | |

| AUC0–72 (pg*h/mL) | 4203 (2384) | 1868 (955) | 4173 (2407) | 6095 (2986) | 1931 (1124) | 2095 (1173) | 2337 (1470) | 1842 (638) | a, b, c, d, f |

*Proportion of women who reached Tmax by the 12- and 24-h time points are expressed as n (%); all other data are expressed as mean (SD) or mean (SEM)

†p values comparing responses calculated using chi square tests for categorical variables (in cases in which cell sizes were < 5, Fisher exact test was performed) or Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous variables, except for AUC which was calculated using t-test with Welch’s correction

aStatistically significant at alpha < 0.05 between all PCOS and all normo-ovulatory

bStatistically significant at alpha < 0.05 between all normal weight and all overweight/obese

cStatistically significant at alpha < 0.05 between normal weight PCOS and normal weight normo-ovulatory

dStatistically significant at alpha < 0.05 between normal weight PCOS and overweight/obese PCOS

eStatistically significant at alpha < 0.05 between normal weight normo-ovulatory and overweight/obese normo-ovulatory

fStatistically significant at alpha < 0.05 between overweight/obese PCOS and overweight/obese normo-ovulatory

The mean baseline-corrected concentration-time profiles of serum estradiol following the subcutaneous FSH injection are shown in Fig. 2–c, and pharmacokinetic parameters are shown in Table 4. There was no difference in Cmax of baseline-corrected estradiol concentration between any of the subgroups, nor was there any difference in average Tmax or the proportion of women who reached Cmax by the 12- or 24-h timepoints. However, the AUC0–72 of baseline-corrected estradiol was significantly different between PCOS and normo-ovulatory groups (4203 vs 1868 pg*h/mL, p < 0.0001) and lean and overweight/obese groups (4173 vs 2095 pg*h/mL, p < 0.0001). The subgroup with the highest AUC0–72 E2 was the lean PCOS group (6095 pg*h/mL), which was significantly higher than the lean normo-ovulatory group (1931 pg*h/mL, p < 0.0001) and the overweight/obese PCOS group (2337 pg*h/mL, p < 0.0001). Similarly, the overweight/obese PCOS subgroup had a higher AUC0–72 E2 than the overweight/obese, normo-ovulatory subgroup (2337 vs 1842 pg*h/mL, p = 0.02). The latter had the lowest AUC0–72 E2 of all the subgroups evaluated. When comparing overweight/obese PCOS women with lean normo-ovulatory controls, though the latter had a lower AUC0–72 E2, it was not statistically significant (2337 vs 1931 pg*h/mL, p = 0.1).

Fig. 2.

a Baseline-corrected change in E2 (pg/mL) by subgroup. b Baseline-corrected change in E2 (pg/mL) by BMI (lean versus overweight/obese). c Baseline-corrected change in E2 (pg/mL) by ovulatory status (PCOS versus normo-ovulatory). Data presented as mean + SEM

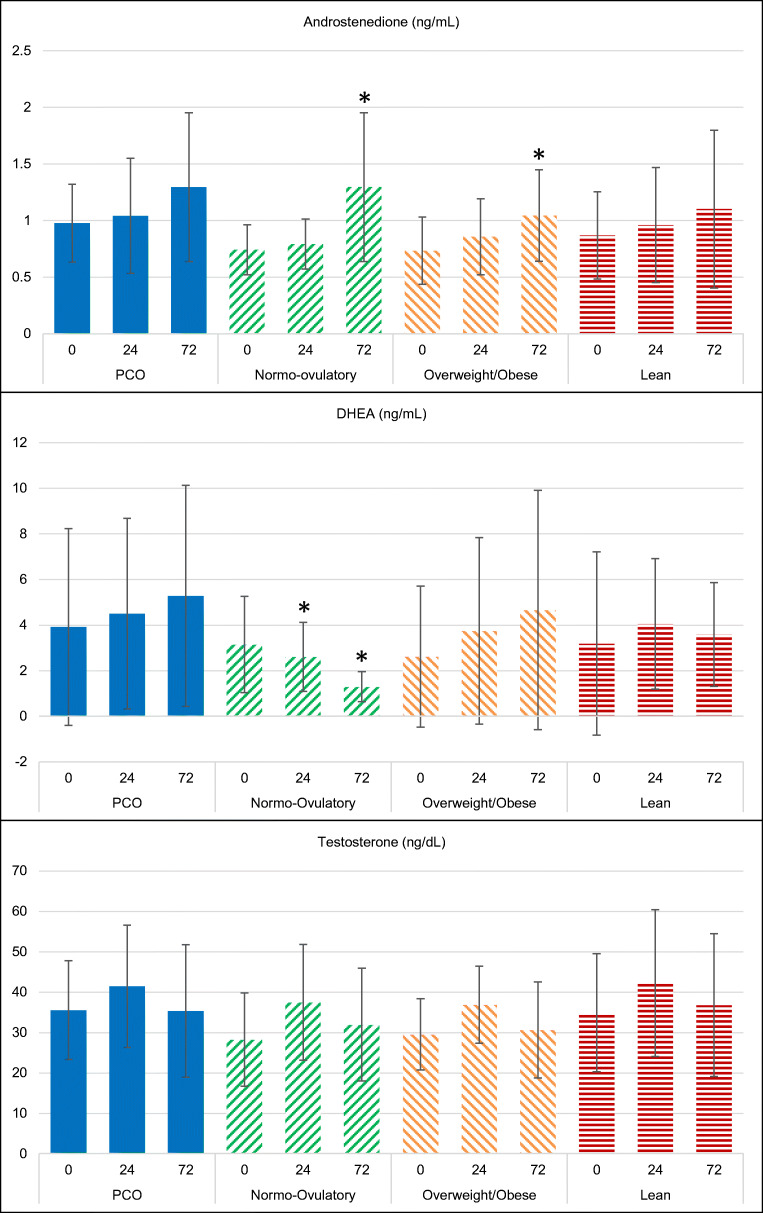

Baseline (time 0, just prior to FSH injection) and subsequent (24- and 72-h timepoints following FSH injection) serum androgen levels are shown in Fig. 3. The PCOS group did not demonstrate any significant differences at 24 h or 72 h following FSH injection from baseline of any of the androgens tested (androstenedione, DHEA or testosterone). Similarly, the lean subgroup did not demonstrate any significant differences at 24 h or 72 h of any androgens. Amongst the normo-ovulatory group, at 72 h the androstenedione level was significantly higher compared with baseline; the 24-h DHEA was significantly lower, as was the 72-h DHEA. This was in contrast to the PCOS group, in which the average DHEA level trended upwards following FSH injection, although this was not significantly different from baseline. Amongst overweight/obese participants, the 72-h androstenedione was significantly higher than baseline. While a similar trend appeared for DHEA, this did not reach statistical significance.

Fig. 3.

Mean (+ SD) serum androgen levels before and after (at 24 and 72 h) administration of rFSH in PCOS and normo-ovulatory subjects, overweight/obese and lean subjects. A significant change from baseline (p < 0.05) is denoted by an asterisk

Discussion

This study compared the absorption of rFSH following subcutaneous injection and the subsequent ovarian response in normal-weight and overweight/obese women with PCOS, as well as normo-ovulatory controls, across BMI and ovulatory status subgroups. It is the first FSH pharmacokinetic study to specifically include PCOS patients across a wide BMI spectrum. Our major finding, as discussed in detail below, was that following rFSH injection, the FSH and estradiol response in overweight/obese PCOS subjects is lesser than that in lean PCOS, but greater than that in matched normo-ovulatory subjects.

Similar to prior studies, women in our study with a normal BMI had a higher maximum concentration of FSH and higher AUC following rFSH injection when compared with women with an overweight/obese BMI. Similarly, within normo-ovulatory and PCOS subgroups, the lean cohort consistently had a statistically significantly higher AUC FSH when compared with their overweight/obese counterparts, suggesting that the absorption of FSH is mediated by adiposity and overall volume of distribution. Interestingly, there was no difference between AUC FSH when comparing the overall PCOS with normo-ovulatory groups, which were matched 1:1 by age and BMI and did not differ significantly by BMI or total body fat percentage. However, within the overweight/obese group itself, those with PCOS had a higher average AUC FSH when compared with normo-ovulatory controls, suggesting there may be additional mechanisms at play in women with PCOS affecting FSH absorption, metabolism, and/or clearance.

There were multiple differences in estradiol concentration-time profiles following rFSH injection between groups. As expected, and can be explained from differences in FSH absorption, the overall lean group had a significantly higher AUC E2 compared with the overweight/obese group. Those in the PCOS group also tended to have higher AUC E2 when compared with the overall normo-ovulatory cohort even in similar BMI subgroups, which speaks to the ovarian responsiveness of women with PCOS to FSH, and may be explained by either the inherent granulosa cell responsiveness or the increased number of antral and pre-antral follicles (not surprisingly, the PCOS population had significantly higher AFC and AMH values compared to the normo-ovulatory controls). The most exaggerated estradiol response was in the lean PCOS subgroup, with the highest AUC E2. The group with the next highest estradiol response was the overweight PCOS subgroup, whose AUC E2 was significantly higher than that of the overweight normo-ovulatory subgroup.

This calls into question the clinical predicament of choosing a starting dose of gonadotropin when initiating IVF in women with varying BMI’s and ovulatory status. In current practice, it is common to conservatively dose patients with PCOS due to the risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) based on their measures of ovarian reserve. This is particularly true within the lean PCOS subtype, as thin BMI and high AFC/AMH levels are known risk factors for OHSS [14–18]. However, in the case of the overweight/obese PCOS patients, it is unclear whether to dose their gonadotropins according to markers of ovarian reserve or BMI, or to consider both. Our data suggested that the overweight PCOS patient does have significantly lower overall circulating FSH and estradiol levels following rFSH injection when compared with the lean PCOS patient with similar ovarian reserve markers. This is notable to consider when initiating patients on gonadotropins, as it suggests that overweight/obese PCOS patients may need to be dosed higher than lean PCOS patients to achieve similar circulating FSH levels and potentially to induce adequate follicular recruitment and maturation.

Interestingly, our study also demonstrated that when comparing the overweight/obese PCOS patient with a lean, normo-ovulatory control, despite the overweight PCOS patient having a lower AUC FSH, her estradiol response is similar (if not slightly higher) than that of a lean, normo-ovulatory patient. This speaks to the inherent ovarian responsiveness of PCOS patients, the mechanism of which is likely multifactorial. As previously discussed, PCOS patients typically have higher numbers of antral and pre-antral follicles, as well as granulosa cells that have an exaggerated response to FSH. Furthermore, some data have suggested the role of insulin acting as a co-gonadotropin within the ovary, amplifying steroid hormone production [19]. Our study found that the subgroup with the lowest FSH absorption and most blunted E2 response is that of overweight/obese, normo-ovulatory women.

In our study, women with PCOS exhibited no significant change from baseline in their serum androgen levels following FSH injection. This is in contrast to the normo-ovulatory group, which demonstrated on average significantly lower DHEA levels 24 h and 72 h after FSH injection, and higher androstenedione levels at 72 h. Amongst prior studies, in which similarly PCOS and normo-ovulatory control patients were subjected to an intravenous bolus of FSH, it had been previously shown that PCOS patients had an exaggerated androgen response with significantly higher androstenedione and DHEA levels at 24 h after FSH compared to baseline [20]. However, in the Wachs et al. study, the PCOS subgroup had a significantly higher mean BMI compared with the normo-ovulatory controls (34.8 vs 28.9 kg/m2), and after adjusting for BMI as well as insulin levels, the analysis demonstrated no difference in androgen responses between PCOS and normo-ovulatory women. It has been previously reported that BMI and insulin may be positively associated with LH-stimulated androgen production by theca cells [19, 21, 22]. This may in part explain why in our study the overweight/obese group, which had an overall higher fasting insulin level than the lean group, had a more exaggerated androstenedione response to FSH than the lean group.

A potential explanation for the difference in androgen response in our study compared with prior studies is that the Wachs study utilized a bolus of IV FSH, whereas we administered a subcutaneous injection of FSH, consistent with what is clinically performed in current practice. Furthermore, our patients were downregulated with 2–3 weeks of combined oral contraceptive pills as is commonly done prior to initiating an IVF stimulation, which may have exerted an effect on androgen response either by SHBG-mediated mechanisms or another mechanism altogether. Further studies are needed to better explain the effect of FSH on ovarian androgen production in PCOS versus normo-ovulatory women.

A key strength of this study is in the highly standardized and matched subject population. All subjects with PCOS were matched by age and BMI to normo-ovulatory controls, thus allowing us to recruit subjects across a wide BMI differential. Another strength is the utility of a study design that mimics what is done in clinical practice, with the use of oral contraceptive lead-in and subcutaneous rFSH administration. In comparison, prior studies have either utilized intravenous FSH [8, 20, 23] which is never used clinically, and/or pituitary downregulation with a GnRH agonist [11] which has declined in popularity in favor of GnRH antagonist protocols, which reduce the risk of OHSS.

There are of course limitations to this pilot study to consider. First, we only administered a single dose of rFSH, rather than repeated daily doses as is performed for most IVF protocols. Second, it is difficult to know how the results of this study might have changed if enrolled patients had a clinical diagnosis of infertility. It would be important to study whether these pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic differences translate to an infertile population, and whether the differences in FSH and E2 may also translate to clinical outcomes (such as follicular recruitment, duration of ovarian stimulation prior to oocyte retrieval, egg maturity, and embryo quality). Finally, the study was powered to detect differences in pharmacokinetic parameters following FSH injection, not to examine the androgen response. A larger cohort may be needed to fully investigate the difference in serum androgen response to FSH between PCOS and normo-ovulatory subjects.

In this pilot study, we found that, similar to previous studies, FSH absorption and maximum circulating concentrations were mediated by BMI, with overweight/obese women having significantly lower Cmax FSH than women with a normal BMI. PCOS also appeared to mediate FSH absorption and metabolism, although through an unclear mechanism, as overweight/obese PCOS women had a significantly higher AUC FSH when compared with overweight/obese normo-ovulatory women. Beyond the pharmacokinetics of FSH absorption and metabolism, there are additional factors driving ovarian responsiveness, as overweight/obese PCOS women had a similar estradiol response to the same FSH dosage as lean normo-ovulatory controls. Further studies are warranted to better understand the pathways involved in ovarian response to gonadotropins in ovulatory and PCOS subgroups. Such studies may allow for finer tuning of rFSH dosing in the daily clinical practice of in vitro fertilization.

Acknowledgments

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources, the National Center for Advancing Translational Science, or the National Institutes of Health.

Funding information

This work was conducted with support from the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Expanding the Boundaries Grant; EMD Serono; and Harvard Catalyst, The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (the project was supported by Grant Number 1UL1TR002541-01, Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center, from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science and Grant Number 1UL1TR001102). Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health under Award Number P51OD011106 to the Wisconsin National Primate Research Center, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Compliance with ethical standards

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee (Partners Healthcare Institutional Review Board) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Disclosure statement

MSL, AL, AVD, AB have nothing to disclose. ESG receives royalties from UpToDate.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Azziz R, Woods KS, Reyna R, Key TJ, Knochenhauer ES, Yildiz BO. The prevalence and features of the polycystic ovary syndrome in an unselected population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(6):2745–2749. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-032046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knochenhauer ES, Key TJ, Kahsar-Miller M, Waggoner W, Boots LR, Azziz R. Prevalence of the polycystic ovary syndrome in unselected black and white women of the southeastern United States: a prospective study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83(9):3078–3082. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.9.5090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Kouli CR, Bergiele AT, Filandra FA, Tsianateli TC, Spina GG, Zapanti ED, Bartzis MI. A survey of the polycystic ovary syndrome in the Greek Island of Lesbos: hormonal and metabolic profile. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:4006–4011. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.11.6148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldzieher JW, Axelrod LR. Clinical and biochemical features of polycystic ovarian disease. Fertil Steril. 1963;14:631–653. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)35047-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ben-Rafael Z, Levy T, Schoemaker J. Pharmacokinetics of follicle-stimulating hormone: clinical significance. Fertil Steril. 1998;69:40S–49S. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(97)00507-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mannaerts B, de Leeuw R, Geelen J, Van Ravestein A, Van Wezenbeek P, Schuurs A, Kloosterboer H. Comparative in vitro and in vivo studies on the biological characteristics of recombinant human follicle-stimulating hormone. Endocrinology. 1991;129(5):2623–2630. doi: 10.1210/endo-129-5-2623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coffler MS, Patel K, Dahan MH, Malcom PJ, Kawashima T, Deutsch R, Chang RJ. Evidence for abnormal granulosa cell responsiveness to follicle stimulating hormone in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(4):1742–1747. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosencrantz MA, Wachs DS, Coffler MS, Malcom PJ, Donohue M, Chang RJ. Comparison of inhibin B and estradiol responses to intravenous FSH in women with polycystic ovary syndrome and normal women. Hum Reprod. 2010;25(1):198–203. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erickson GF, Magoffin DA, Cragun JR, Chang RJ. The effects of insulin and insulin-like growth factors-I and -II on estradiol production by granulosa cells of polycystic ovaries. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990;70(4):894–902. doi: 10.1210/jcem-70-4-894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Azziz R, Sanchez LA, Knochenhauer ES, Moran C, Lazenby J, Stephens KC, Taylor K, Boots LR. Androgen excess in women: experience with over 1000 consecutive patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:453–462. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steinkampf MP, Hammond KR, Nichols JE, Slayden SH. Effect of obesity on recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone absorption: subcutaneous versus intramuscular administration. Fertil Steril. 2003;80:99–102. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(03)00566-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS consensus workshop group Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) Hum Reprod. 2004;19(1):41–47. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Le Cotonnec JY, Loumaye E, Porchet HC, Beltrami V, Munafo A. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interactions between recombinant human luteinizing hormone and recombinant human follicle-stimulating hormone. Fertil Steril. 1998;69(2):201–209. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(97)00503-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luke B, Brown MB, Morbeck DE, Hudson SB, Coddington CC, Stern JE. Factors associated with ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) and its effect on assisted reproductive technology (ART) treatment and outcome. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:1399–1404. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.05.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swanton A, Storey L, McVeigh E, Child T. IVF outcome in women with PCOS, PCO and normal ovarian morphology. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010;149:68–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee TH, Liu CH, Huang CC, Wu YL, Shih YT, Ho HN, Yang YS, Lee MS. Serum anti-Müllerian hormone and estradiol levels as predictors of ovarian hyper stimulation syndrome in assisted reproduction technology cycles. Hum Reprod. 2008;23(1):160–167. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jayaprakasan K, Chan Y, Islam R, Haoula Z, Hopkisson J, Coomarasamy A, Raine-Fenning N. Prediction of in vitro fertilization outcome at different antral follicle count thresholds in a prospective cohort of 1,012 women. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:657–663. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aramwit P, Pruksananonda K, Kasettratat N, Jammeechai K. Risk factors for ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome in Thai patients using gonadotropins for in vitro fertilization. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65:1148–1153. doi: 10.2146/ajhp070566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ciampelli M, Fulghesu AM, Cucinelli F, Pavone V, Ronsisvalle E, Guido M, Caruso A, Lanzone A. Impact of insulin and body mass index on metabolic and endocrine variables in polycystic ovary syndrome. Metabolism. 1999;48(2):167–172. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(99)90028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wachs DS, Coffler MS, Malcom PJ, Shimasaki S, Chang RJ. Increased androgen response to follicle-stimulating hormone administration in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(5):1827–1833. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bergh C, Carlsson B, Olsson JH, Selleskog U, Hillensjö T. Regulation of androgen production in cultured human thecal cells by insulin-like growth factor I and insulin. Fertil Steril. 1993;59(2):323–331. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)55675-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nahum R, Thong KJ, Hillier SG. Metabolic regulation of androgen production by human thecal cells in vitro. Hum Reprod. 1995;10(1):75–81. doi: 10.1093/humrep/10.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wachs DS, Coffler MS, Malcom PJ, Chang RJ. Comparison of follicle-stimulating-hormone-stimulated dimeric inhibin and estradiol responses as indicators of granulosa cell function in polycystic ovary syndrome and normal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(8):2920–2925. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]