Abstract

Nineteen samples of Arabica and 14 of Robusta coming from various plantation were analysed by dynamic headspace capillary gas chromatography–mass spectrometry to characterize the volatile fraction of green and roasted samples and the relationships of the same species with geographical origin. As concerns green beans, Arabica species appear characterized by high content of n-hexanol, furfural and amylformate, while Robusta species by greater content of ethylpyrazine, dimethylsulfone and 2-heptanone. Four variables, 4-methyl-2,3-dihydrofuran, n-hexanol, limonene and nonanal, appear involved in the characterization of the geographical origin of the analysed samples. The volatile fraction of the roasted Arabica samples, appear characterized by high content of pyridine, diacetyl, propylformate, acetone and 2,3-pentanedione, while Robusta samples by high content of methylbutyrate, 2,3-dimethylpyrazine and 3-hexanone. Considering geographical origin of the analysed samples, four compounds appear involved, in particular 2-butanone, methylbutyrate, methanol and ethylformate. Very accurate (error rate lower than 5%) rules to classify samples as Arabica or Robusta according to their compounds profile were developed.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10068-020-00779-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Arabica and Robusta coffee, Dynamic head space, GC–MS, Green and roasted coffee, Volatile compound

Introduction

Coffee beans are the seeds of an evergreen shrub belonging to the Rubiaceae family and the genus Coffea. There are more than 100 species of coffee worldwide, but two species are of importance commercially, Coffea Arabica Linn. var. arabica, known in the trade as Arabica and Coffea canephora Pierre ex Froehner var. robusta, commercially called Robusta (Clarke and Macrae, 1985). Arabica is the most appreciated species worldwide, due to its sensory superiority, and represents more than 60% of global production. Its cultivation demands a relatively mild climatic conditions and a well-defined dry season (Toledo et al., 2016).

Robusta coffee grows at low altitudes, tolerates higher temperature and heavier rainfall, demands a higher soil humus content than Arabica and generally it is also much more resistant to diseases allowing mechanization of the cultivation technique. For these reasons the production of Robusta coffee is more economical (Clarke and Macrae, 1985; Colzi et al., 2017). Coffee beans contain several groups of bioactive compounds as alkaloids, phenolics and terpenoids. These compounds exhibit an antioxidant activity and coffee brew may be a good source of health-beneficial phytochemicals in diet (Lim et al., 2012). The condition of roasting process, temperature and time, are the most crucial for the content of bioactive compounds in coffee brew (Chung et al., 2013). In particular, high temperature and low water activity, facilitate molecular degradation in the roasting process (Herawati et al., 2019).

The volatile fraction of roasted coffee is one of the most important factors for determining coffee quality and it can be decisive at the time of purchase. The aroma of coffee is intrinsically related to the chemical composition of the bean, genetic strain, geographical location, climate, annual rainfall, agricultural practice and processing method applied (Toledo et al., 2016; Buffo and Cardelli-Freire, 2004). In order to characterize the species and the influence of geographical origin, some studies are focused on the identification of volatiles in green coffee (Flament, 2001), fingerprinting coffee flavor (Huang et al., 2007), discrimination of volatiles in defective coffee (Toci and Farah, 2008; Walker et al., 2019) and the effect of climatic conditions on the volatile compounds of green coffee (Bertrand et al., 2012).

Aroma volatiles produced during coffee bean roasting, have been previously reviewed (Grosch 2001; Toledo et al., 2016). Coffee volatiles are derived from numerous precursors found in the bean by chemical reactions, including Maillard reaction, Strecker degradation, degradation of trigonelline, chlorogenic acids, pigments, lipids, phenolic acids together with the breakdown of amino acids (Holscher and Steinhart, 1992; Ribeiro et al., 2009). Many studies have distinguished samples of roasted Arabica and Robusta coffee from different geographical origin (Colzi et al., 2017; Yener et al., 2014; Mathieu et al., 1996; Sanz et al., 2002; Rocha et al., 2004; Korhonovà et al., 2005). In most cases, emphasis was placed on geographical differentiation, but little can be concluded regarding the cause of differentiation. Some studies (Mondello et al., 2005; Cheong et al., 2013) indicated that it was very difficult to correlate the aromatic fraction present and the climatic conditions.

In order to satisfactorily analyze the aroma compounds of food, the analytical extraction methods applied are oriented to the sample manipulation and use of solvents reduction (Lee et al., 2013). Headspace techniques are the most suitable ones for the study of aroma compounds and dynamic sampling has been shown to be the most suitable as it does not introduce discrimination in the volatile components analyzed (Barcarolo et al., 1992; Clarke and Macrae, 1985). These methods have several advantages, such as being quicker, relatively simpler and highly reproducible. A particular dynamic headspace gas chromatography (DHS-GC) solvent-free device incorporated a reverse-flow step in order to avoid any contamination of the analytical gas chromatography column with gases or other substances that could not be correctly condensed (Barcarolo and Casson, 1997).

In some previous papers, the characterization of the volatile fraction of different matrices, such as olive oils (Procida et al., 2005, Procida et al., 2016), dairy products (Stefanon and Procida, 2004) and saffron (Procida et al., 2009) by headspace analyses of a number of samples, was reported in order to determine a relationship between compounds in the headspace and sensory evaluation.

In this paper, we have applied headspace analysis (Barcarolo and Casson, 1997) to a number of green and roasted Arabica and Robusta coffees samples. The aim of this preliminary study was to obtain flavor profile of the samples which vaporize at room temperature and could be correlated to natural olfactory perception. Qualitative and quantitative differences of the volatile fraction of the two coffee species, with the aim to identify possible markers that could discriminate the species of coffee analysed and highlight a correlation between the aromatic compounds of volatile pattern of single species and geographical origin, were investigated. For these purposes, the chemical composition of the volatile fraction of the analysed samples was explored to obtain a differentiation on the basis of chemometric tools.

Materials and methods

Sampling

Thirty-three green coffee samples (19 Arabica and 14 Robusta) from all the world were analysed. In particular as far as the Arabica is concerned, 5 samples came from Africa (Kenya, Cameroon, Uganda, Ethiopia and Burundi), 8 from Central America (Nicaragua, Cuba, Guatemala, Haiti, Costa Rica, Mexico, Santo Domingo and Puerto Rico) and 6 from South America (Venezuela, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Brazil Santos Florada and Fancy).

As far as Robusta are concerned, 8 samples came from Africa (Madagascar, Congo, Cameroon, Togo, Ivory Coast, Uganda, Angola and Central African Republic) and 6 from Asia (India Cherry and Parchment, Vietnam, Indonesia, Thailand and Java). All analysed samples of green coffee were subsequently roasted at 220 °C for about 15 min by a TT 7.5 roasting apparatus (Petroncini, Ferrara, Italy).

Headspace sampling

Three aliquots of 500 g each were ground for each sample considered. The aliquots to be analysed were taken from the whole mixture of the ground product (1.5 kg). 1 g of each sample, finely ground in a Retsch mill, was exactly weighed in a 10 ml vial then the vials were sealed with aluminium-rubber septum (Supelco, Bellefonte, PA, USA). 0.02 μl (17.8 μg) of the internal standard were added, either ethyl propionate (≥ 99.7%) to green coffee samples, or tetrahydrofuran (≥ 99.9%: Sigma St. Louis, USA) to roasted coffee; the internal standard was added to the sample for injection through the rubber septum by Hamilton 7001KH syringe (1 μl). Vials with samples were conditioned at 25 °C for 30 min before analysis, then stripping was carried out for 150 s on green samples and 90 s on roasted coffees. Stripping was realised with helium at a rate of 10 ml/min. During sampling volatile components are transferred into a capillary tube (0.53 mm I.D.) that was inside a cryogenic trap cooled by liquid nitrogen at − 110 °C: the trap is connected by an on-column mode to a capillary gas chromatograph (Carlo Erba GC 8000; Carlo Erba, Milan, Italy). The cryogenic trap, which was represented by a fused silica capillary tube, did not show activated adsorbent or porous polymers. This trap allows the acquisition of an aroma profile similar to natural olfactory perception without artefacts or problems related to competition between volatiles and incomplete or irreversible adsorption.

GC–MS analysis

At the end of the sampling time, desorption of volatile components took place by rapid heating of the cryogenic trap to 240 °C in 5 s and then by transferring volatiles to the analytical capillary column in 15 s. The analytical column used was a capillary fused-silica column 50 m x 0.32 mm I.D., coated with PS 264 (7% diphenyl/93% dimethylsiloxane), 3 μm film thickness (Mega, Milan, Italy). The GC system was coupled directly to a MD 800 mass spectrometer (Carlo Erba, Milan, Italy). Gas chromatographic conditions were the following: oven initial temperature 40 °C, held for 6 min, then programmed to 180 °C at a rate of 5 °C/min, then 5 min at 180 °C, then at 7 °C/min to 200 °C, held 2 min, and finally at 7 °C/min to 240 °C with 10 min of final isotherm. The transfer line temperature was kept at 250 °C.

The mass spectrometer scanned from 29 to m/z 300 at 0.5 s cycle time. The ion source was set at 180 °C and spectra were obtained by electron impact (70 eV).

The tentative identification of compounds was carried out through a study of the MS spectra and comparison with members of the NBS library.

Quantitative evaluation was carried out by using internal standard method: we set the response factor as unity for each substance so it was possible to give quantitative data as internal standard equivalent and to compare the content of each component in analysed samples.

Statistical analysis

The mean levels of each compound in Arabica and Robusta samples were compared using the Mann–Whitney test for the comparison of two groups. Bonferroni adjustment was applied to take into account multiplicity of the test. Only comparisons with adjusted p value < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

To identify the components of the volatile fraction that best discriminate between the two species the multivariate analysis technique named Classification Tree was applied. Classification tree is a method for supervised learning, i.e. to develop a classification rule based on data where true classification is known (in our case, the species) and information is available on potential predictors (the volatile compounds). With this technique, data are recursively partitioned into two groups based on the value of the single variable that, at that level, best discriminates among the considered classes. The result of the analysis is usually represented using a binary tree, where the leaves represent the classes and the branches represent the variables. In this way a classification rule is developed, that can then be applied to new samples where information about classification is not known. The power of the rule is measured in terms of misclassification error, i.e. the percentage of observations not correctly classified. Obviously, the classification ability of the technique increases with the complexity of the classification rule (i.e. the number of features used and/or levels of the tree), however results obtained with complex classification rules are hardly reproducible. For this reason, techniques based on the use of a validation set of data or on cross-validation (a leave one out method to evaluate the prediction error) have been developed to find a good compromise between the complexity of the rule and the misclassification error. Given the size of our sample, it was not possible to divide it in two parts, the training and the validation set, and then we made use of cross-validation to ‘prune’ a complex tree and find the optimal balance.

Classification tree methodology has been chosen because of its ability to handle a very large number of predictors and because it can detect complex interactions among them.

All the analyses were separately done for green and roasted coffee using the statistical package R ver. 3.4.2 (R. Core Team, 2015).

Results and discussion

In aroma research, headspace techniques are the most suitable for the determination of chemical components. The dynamic sampling was shown to be the most suitable since it does not introduce discrimination and enables nearly all of the volatile components to be analyzed. The particular head space configuration enables helium flow inversion through the Y press fit system during the sampling step and inhibits entry into the column of substances not cryofocused that exit through vapour exit device. This was performed with the aim of avoiding any contamination of the analytical column with incondensable gases, whose presence could produce a very broad peak and consequently lead to a poor chromatographic resolution (Barcarolo and Casson, 1997). Stripping was carried out at room temperature; it is thus possible to obtain an aroma profile as much as possible near to the natural olfactory perception (Hinshaw, 1988).

Analysis of the volatile fraction of green coffees allowed the identification of 68 compounds. These can be grouped into different classes, including alcohols, aldehydes, ketones, furans, sulfur compounds, esters, hydrocarbons, pyrroles, pyrazines and terpenes.

It is well known that in the volatile fraction of green samples several substances usually present in roasted product, such as furans that take origin from sucrose degradation, pyrazines and pyrroles from protein degradation phenomena, and pyridines, from trigonelline degradation, were identified. Degradation phenomena may occur for the main components of the bean during the steps of processing and storage of the product (Flament, 2001).

Our sampling technique allowed the detection of nine alcohols, namely methanol, ethanol, 2-propanol, isobutyalcohol, butanol, 3-methyl-1-butanol, 2-methyl-1-butanol, n-hexanol and 2-heptanol. As concerns the characterization of the species analyzed, the concentration of low molecular weight compounds, as methanol, ethanol, 2-propanol, isobuthylalcohol and butanol, seems homogeneous in the samples of Arabica and Robusta coffees. The two species significantly differ for the content of n-hexanol and 2-heptanol (Fig. 1). The content of hexanol varies from 4.69 and 47.61 μg/kg in Arabica coffee and in a range between 1.75 and 14.13 μg/kg in Robusta coffee samples analyzed: on the contrary, the concentration of 2-heptanol varies from 0.3 and 9.71 μg/kg in Arabica and ranged between 5.03 and 185.3 μg/kg in Robusta (Table 1). The higher lipoxygenase activity for linolenic acid than linoleic acid supports the biogenesis of more of C6 volatile compounds (Kalua et al., 2007).

Fig. 1.

Green coffee: boxplot of concentration of components with significant difference between the two species (p-values based on Mann–Whitney test)

Table 1.

Significant volatile compounds (μg/kg) in the examined samples of the green Arabica and Robusta coffees

| Plantation | Ethanal | Methylacetate | Isobutanal | Thiophene | Amylformate | 4-methyl-2,3-dihydrofuran | Hexanal | Furfural | n-hexanol | 2-heptanone | 2-heptanol | Ethylpyrazine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabica | Compound | |||||||||||

| Kenya | 3830 | 79.13 | 943.0 | 4.60 | 74.25 | 7.61 | 1467 | 23.90 | 24.63 | 6.10 | 5.28 | 4.61 |

| Cameroon | 1548 | 34.17 | 956.4 | 6.62 | 57.70 | 14.32 | 1008 | 127.3 | 20.01 | 4.38 | 1.81 | 11.36 |

| Uganda | 2043 | 33.83 | 1132 | 8,13 | 46.26 | 9.40 | 1119 | 25.06 | 11.15 | 6.15 | 7.91 | 4.73 |

| Ethiopia | 3144 | 7.45 | 535.3 | ND | 39.55 | 9.96 | 705.8 | 34.70 | 24.88 | 5.86 | 4.83 | 8.83 |

| Burundi | 1184 | 9.04 | 277.9 | ND | 16.87 | 4.16 | 440.2 | 11.08 | 8.21 | 3.72 | 5.05 | ND |

| Nicaragua | 1364 | 4.86 | 317.7 | ND | 116.7 | 7.30 | 2696 | 31.96 | 28.38 | 3.31 | 9.71 | 4.41 |

| Cuba | 874.5 | 8.74 | 502.4 | 3.64 | 18.40 | 3.37 | 350.7 | 21.67 | 5.66 | 1.28 | 4.85 | 3.14 |

| Guatemala | 4372 | 74.74 | 1438 | 4.34 | 116.4 | 12.19 | 1757 | 32.61 | 37.20 | 5.53 | 6.31 | 6.36 |

| Haiti | 427.8 | 18.37 | 1454 | 4.78 | 23.25 | 3.90 | 83,816 | 20.89 | 4.69 | 2.92 | ND | 6.38 |

| Costa Rica | 1779 | 23.79 | 491.3 | ND | 68.05 | 3.89 | 914.4 | 42.34 | 30.78 | 4.52 | 4.50 | 7.68 |

| Mexico | 3328 | 70.72 | 1208 | 3.52 | 64.44 | 4.71 | 118,516 | 26.99 | 19.53 | 5.47 | 4.60 | 7.75 |

| Santo Domingo | 1964 | 4.26 | 330.6 | 3.20 | 30.26 | 2.49 | 544.3 | 32.93 | 31.41 | 2.67 | 1.61 | 4.34 |

| Puerto Rico | 968.5 | 7.96 | 394.2 | ND | 76.39 | 0.94 | 2254 | 11.54 | 18.58 | 4.32 | 6.51 | ND |

| Venezuela | 3118 | 32.85 | 1396 | 4.40 | 50.60 | 9.01 | 701.1 | 70.78 | 19.72 | 4.40 | 5.53 | 1.42 |

| Peru | 2403 | 46.66 | 1680 | 8.24 | 151.8 | 9.44 | 2111 | 81.05 | 47.61 | 12.11 | 9.59 | 12.49 |

| Ecuador | 2624 | 40.50 | 2252 | 6.32 | 76.80 | 5.53 | 1590 | 38.44 | 17.75 | 5.61 | 6.31 | 9.24 |

| Colombia | 389.5 | 5.42 | 336.2 | ND | 61.29 | 7.81 | 577.5 | 53.03 | 19.07 | 3.20 | 1.77 | 6.67 |

| Brazil Santos Florada | 5723 | 2.33 | 178.9 | ND | 15.48 | 0.90 | 331.1 | 7.55 | 7.54 | ND | 0.30 | ND |

| Brazil Fancy | 902.9 | 8.84 | 463.2 | ND | 19.01 | 8.32 | 372.1 | 21.80 | 22.42 | 6.31 | 7.42 | 2.08 |

| Robusta | ||||||||||||

| Madagascar | 1410 | 50.20 | 1469 | 9.73 | 30.13 | 14.44 | 1581 | 58.0 | 7.87 | 23.0 | 42.0 | 9.25 |

| Congo | 2605 | 80.87 | 1864 | 11.17 | 26.61 | 35.56 | 1380 | 72.76 | 4.90 | 17.81 | 30.20 | 16.30 |

| Cameroon | 2463 | 23.94 | 1508 | 5.30 | 54.51 | 77.34 | 3282 | 42.81 | 14.13 | 23.11 | 185.3 | 23.30 |

| Togo | 1742 | 65.90 | 2889 | 19.40 | 6.37 | 18.11 | 741.8 | 64.89 | ND | 16.81 | 38.40 | 16.76 |

| Ivory Coast | 1363 | 52.93 | 1440 | 14.13 | 24.97 | 14.72 | 1106 | 72.0 | 8.78 | 31.50 | 37.90 | 12.77 |

| Uganda | 2572 | 186.1 | 2161 | 5.10 | 18.06 | 19.64 | 823.1 | 40.76 | 4.71 | 6.75 | 9.70 | 19.0 |

| Angola | 2646 | 118.1 | 1482 | 4.12 | 28.31 | 16.05 | 1068 | 39.87 | 4.82 | 7.10 | 7.05 | 16.40 |

| Central African Rep. | 1847 | 77.0 | 2958 | 17.15 | 17.51 | 22.26 | 1413 | 67.70 | 2.21 | 12.76 | 23.50 | 18.80 |

| India Cherry | 1667 | 136.5 | 2501 | 11.80 | 9.03 | 16.11 | 536.9 | 31.47 | 1.75 | 16.78 | 22.63 | 13.60 |

| India Parchment | 468.3 | 56.20 | 1176 | 8.22 | 16.46 | 6.21 | 739.3 | 23.84 | 3.44 | 4.60 | 5.03 | 4.33 |

| Vietnam | 1666 | 73.73 | 1712 | 11.73 | 13.61 | 11.86 | 972.3 | 34.87 | 3.34 | 6.75 | 9.92 | 12.67 |

| Indonesia | 1430 | 139.9 | 2094 | 9.71 | 9.57 | 10.57 | 460.3 | 37.86 | 3.98 | 8.62 | 14.62 | 29.36 |

| Thailand | 2008 | 10.42 | 344.9 | 7.70 | 27.03 | 4.31 | 792.1 | 39.50 | 3.97 | 5.32 | 16.57 | 11.68 |

| Java | 1103 | 23.48 | 595.7 | 9.96 | 17.70 | 11.11 | 837.1 | 74.90 | 9.23 | 6.83 | 13.67 | 18.64 |

Values are mean (n = 3)

ND not detected

Seventeen aldehydes were identified in the green samples analyzed. Observing the data, the concentration of ethanal in Arabica ranged between 389.5 and 5723 μg/kg while hexanal, ranged between 350.7 and 118,516 μg/kg appears higher than in Robusta samples, ranged from 468.3 to 2646 μg/kg and from 460.3 to 3282 μg/kg, respectively (Table 1). The higher presence of ethanal in Arabica may be associated with the sensory quality of the samples, in particular with the fruity attribute, while hexanal may be indicator of body and bitterness (Bertrand et al., 2012). A significative difference was observed for isobutanal, whose concentration ranged between 178.9 and 2252 μg/kg in Arabica samples and between 344.9 and 2958 μg/kg in Robusta samples (Fig. 1).

Besides, our sampling technique allowed the detection of nine ketones, namely acetone, butan-2,3-dione, butan-2-one, 2,3-pentadione, 3-hydroxy-2-butanone, 3-methyl-2-pentanone, 2-heptanone, 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-one and 3-octen-2-one. From a quantitative point of view, only 2-heptanone shows a significant difference, with values that range between 1.28 and 12.11 μg/kg for Arabica and 4.6 μg/kg and 31.5 μg/kg for Robusta coffees (Fig. 1). This is probably correlated to a reduced seasonal temperature variation during seed grown and with high elevation and cool climate of regions of coffee produced (Bertrand et al., 2012).

Among furans, namely furan, 2-methyl-furan, 2-ethylfuran, 4-methyl-2,3-dihydrofuran, 2-methyl tetrahydrofuran-3-one, furfural and pentylfuran, only 4-methyl-2,3-dihydrofuran shows a significant difference between the two species, with values that range between 0.9 and 14.3 μg/kg for Arabica and 4.3 μg/kg and 77.3 μg/kg for Robusta coffees (Fig. 1).

The analysis of green coffee samples allowed the identification of four pyrazines, namely methylpyrazine, 2,6-dimethylpyrazine, ethylpyrazine and 2,3-dimethylpyrazine. The concentration of ethylpyrazine in Robusta varies from 4.33 to 29.36 μg/kg and is significantly greater respect to Arabica, ranged between 1.42 and 12.49 μg/kg (Fig. 1).

In the volatile fraction of coffee samples, four sulfur compounds were identified, namely 2-thiapropane, carbon disulphide, dimethylsulfone and thiophene. While the concentration of 2-thiopropane and carbon disulphide appear homogeneous in the coffee samples analyzed, dimethylsulfone is only present in Robusta species from 0.18 to 7.36 μg/kg. Besides, the concentration of thiophene in Robusta varies from 4.12 to 19.4 μg/kg, while in Arabica from 3.2 to 8.24 μg/kg (Fig. 1). The concentration of thiophene appears three-fold present in green Robusta coffee rather than in Arabica coffee samples. Sulfur-containing compounds, mainly obtained from methionine, cysteine and cystine via Strecker degradation, are extremely influential on the sensory profile of coffee: due to their extremely low odour thresholds they have a great olfactory impact. Their identification and quantification is crucial for the assessment of coffee sensory quality (Sunarharum et al., 2014; Dulsat-Serra et al., 2016).

Lastly, methylacetate and amylformate show a significant difference between the two species. Methylacetate ranges from 2.33 to 79.13 μg/kg in Arabica samples, while from 10.42 to 186.1 μg/kg in Robusta samples (Table 1); amylformate ranges between 15.48 and 151.8 μg/kg in Arabica samples, and between 6.37 and 54.51 μg/kg in Robusta samples (Fig. 1).

Data were analyzed using classification trees to evaluate the discrimination ability of the compounds that we considered. The classification tree gives a rule to classify the different samples as Arabica or Robusta based on their characteristics. In our case, we obtained the following rule: classify as robusta if the value of 2-heptanol is higher than 9.8 μg/kg or if the value of n-hexanol is lower than 5.2 μg/kg.

The classification rule based on the concentration of 2-heptanol and n-hexanol correctly classifies 18 out of the 19 Arabica samples (1 is indeed classified as Robusta), while all the Robusta samples are correctly classified. The classification rule that we have found is indeed very simple (only two features are involved) and powerful, with just 1 (3% of the total sample) misclassification error. Indeed, other rules with the same characteristics can be found:

classify as Robusta if ethylpyrazine is greater than or equal to 13 μg/kg or if dimethyl sulfone is greater than or equal to 1.4 μg/kg (only one Robusta sample classified as Arabica);

classify as Robusta if 2-heptanone is greater than or equal to 6.5 μg/kg or if n-hexanol is lower than 4.3 μg/kg (only one Arabica sample classified as Robusta);

classify as Arabica if n-hexanol is greater than or equal to 16 μg/kg or if furfural is greater than or equal to 28 μg/kg (only 1 Robusta sample classified as Arabica);

classify as Arabica if amylformate is greater than or equal to 30 μg/kg or if diacetyl is lower than 105 μg/kg (only 1 Robusta sample classified as Arabica);

The four classification rules so identified are equivalent because they share the same degree of complexity and have the same classification error. It can be noticed that most of the variables involved were already identified with the simple comparison of the two species: indeed, also the boxplots in Fig. 1 show the high degree of separation between the two species when considering specific compounds. However, some of the substances used for classification purposes (furfural, diacetyl and dimethyl sulphone) were not significantly different in the two groups.

We applied the same procedure also taking into account the geographical origin of the samples: in this way, we created six classes, four for the Arabica samples (origin: Africa, Caribbean, Central America, South America) and two for the Robusta samples (origin: Africa and Asia).

We then evaluated the discrimination ability of the considered substances by using a classification tree. The result has been obtained from a more complex tree that has been subsequently pruned to find the best balance between complexity and misclassification error.

The resulting classification rule is in this case more complex due to the more articulated nature of the classification. The origin of Robusta samples is identified by 4-methyl-2.3-dihydrofuran (Africa if it is greater than 14 μg/kg) or n-hexanol (Asia if it is lower than 4.3 μg/kg), the Arabica samples have 4-methyl-2.3-dihydrofuran lower than 14 μg/kg and n-hexanol greater than 4.3 μg/kg and can be further classified by origin according to limonene (greater than 9.6 μg/kg for Africa samples) or to n-nonanal (lower than 8 μg/kg for Caribbean, between 8 and 22 μg/kg for South America, greater than 22 μg/kg for Central America).

The classification rule misclassifies 5 samples (15% of the entire sample): an Arabica sample from Africa was classified as coming from the Caribbean, and Arabica sample coming from the Caribbean and another one coming from South America were classified as coming from Central America, a Robusta sample coming from Asia was classified as an Arabica coming from South America and last a Robusta sample coming from Asia was classified as coming from Africa. The classification performance, even if lower than in the case of the species, seems to be more than adequate.

As far as the volatile fraction of roasted coffees, the analytical technique employed allowed the identification of 84 compounds, grouped into different classes, including furans, pyrazines, pyrrole, sulfur compounds, aldehyde, ketones, alcohols and esters.

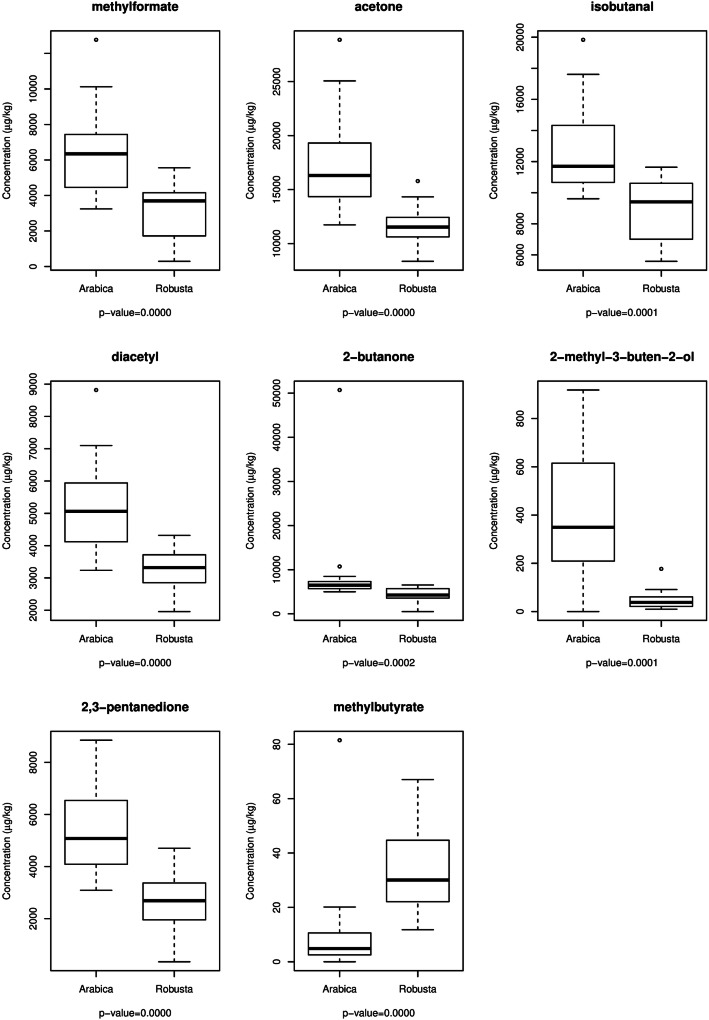

The comparison of the two species in terms of the detected compounds identified eight statistically significant differences (Fig. 2). Of these, 4 refer to ketones: acetone ranges from 11,734 to 28,873 μg/kg for Arabica samples, while in Robusta samples ranges from 8359 to 15,792 μg/kg; diacetyl ranges from 3235 to 8818 μg/kg for Arabica samples and from 1959 and 4316 μg/kg for Robusta samples; 2-butanone ranges from 4996 to 50,711 μg/kg for Arabica samples and from 512.2 to 6530 μg/kg for Robusta samples; 2,3-pentanedione ranges from 3087 to 8853 μg/kg for Arabica samples and from 341.4 to 4701 μg/kg for Robusta samples (Table 2). Two esters, namely methylformate and methylbutyrate show significant differences between the two species, as well as one aldehyde (isobutanal) and one alchool (2-methyl-3-buten-2-ol).

Fig. 2.

Roasted coffee: boxplot of concentration of components with significant difference between the two species (p-values based on Mann–Whitney test)

Table 2.

Significant volatile compounds (μg/kg) in the examined samples of the roasted Arabica and Robusta coffees

| Plantation | Methylformate | Acetone | Isobutanal | Diacetyl | 2-butanone | 2-methyl-3-buten-2-ol | Propylformate | 2,3-pentanedione | Methylbutyrate | Pyridine | 3-hexanone | 2,3-dimethylpyrazine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabica | Compound | |||||||||||

| Kenya | 4330 | 13,878 | 9610 | 4371 | 5302 | 234.5 | 15.85 | 4498 | 4.09 | 8835 | 295.5 | 124.4 |

| Cameroon | 7822 | 18,448 | 16,035 | 7101 | 7639 | 918.5 | 44.18 | 8853 | ND | 11,075 | 704.4 | 171.6 |

| Uganda | 4163 | 12,539 | 10,264 | 3235 | 4996 | 365.3 | 201 | 3556 | 6.95 | 8515 | 303.3 | 245.7 |

| Ethiopia | 6348 | 16,304 | 11,335 | 3814 | 5723 | 210.7 | 18.77 | 3087 | 4.84 | 5332 | 172.6 | 46.12 |

| Burundi | 10,125 | 24,926 | 10,844 | 5347 | 5516 | ND | 6.62 | 4605 | 3.71 | 4457 | 209.8 | 32.12 |

| Nicaragua | 4289 | 11,734 | 10,921 | 4067 | 6228 | 755 | 65.01 | 5696 | 14.98 | 13,040 | 479.9 | 448.2 |

| Cuba | 7011 | 16,369 | 12,175 | 6061 | 6464 | 792.7 | 50.38 | 7959 | 3.25 | 11,119 | 511.2 | 449.4 |

| Guatemala | 5376 | 18,880 | 13,910 | 5018 | 7169 | 223.4 | 19.59 | 4268 | 1.81 | 5934 | 240.7 | 100.2 |

| Haiti | 3242 | 13,980 | 10,194 | 4169 | 7074 | 349.4 | 16.06 | 3342 | 81.50 | 18,869 | 603.6 | 553.4 |

| Costa Rica | 8158 | 20,690 | 17,610 | 6814 | 7472 | 6.0 | 22.05 | 6570 | 0.86 | 4297 | 194.0 | 49.68 |

| Mexico | 6594 | 15,794 | 11,808 | 6216 | 7086 | 591.7 | 32.70 | 6728 | 6.91 | 16,714 | 1062 | 723.1 |

| Santo Domingo | 3892 | 16,036 | 10,476 | 3866 | 5927 | 126.2 | ND | 3192 | 20.15 | 11,825 | 277.8 | 202.7 |

| Puerto Rico | 5780 | 11,896 | 11,025 | 3596 | 50,711 | 572.3 | 54.93 | 5691 | 9.85 | 6523 | 224.3 | 150.7 |

| Venezuela | 4580 | 14,722 | 10,349 | 4304 | 5023 | 310.7 | 16.94 | 5637 | ND | 6401 | 240.8 | 170.8 |

| Peru | 7050 | 19,743 | 15,161 | 5817 | 5659 | 207.9 | 5.36 | 5076 | 1.19 | 9934 | 194.5 | 207.1 |

| Ecuador | 8421 | 16,877 | 14,384 | 5169 | 7080 | 181.2 | 16.32 | 3907 | 3.75 | 12,603 | 356.9 | 294.8 |

| Colombia | 12,770 | 28,873 | 19,833 | 8818 | 10,727 | 638.2 | 17.54 | 8655 | 6.42 | 6644 | 663.1 | 130.1 |

| Brazil Santos Florada | 5492 | 15,429 | 11,693 | 5062 | 6222 | 692.9 | 8.75 | 6510 | 11.39 | 3746 | 432.2 | 112.3 |

| Brazil Fancy | 6475 | 25,063 | 14,270 | 5815 | 8468 | 415.4 | 43.58 | 4952 | 12.36 | 13,909 | 500.4 | 155.3 |

| Robusta | ||||||||||||

| Madagascar | 4155 | 11,136 | 10,582 | 2852 | 4035 | 21.06 | 9.08 | 1951 | 14.96 | 2265 | 190.9 | 116.4 |

| Congo | 1350 | 8359 | 6460 | 1959 | 3339 | 14.51 | 9.06 | 1379 | 23.99 | 4520 | 429.5 | 206.0 |

| Cameroon | 1934 | 10,197 | 6507 | 2710 | 3974 | 30.37 | 11.46 | 2035 | 25.79 | 6931 | 492.3 | 150.4 |

| Togo | 3817 | 15,792 | 10,601 | 4217 | 6254 | 20.82 | 1.94 | 3622 | 55.94 | 10,022 | 1236 | 868.9 |

| Ivory Coast | 1555 | 11,516 | 5586 | 2118 | 2672 | 9.94 | ND | 1154 | 19.43 | 7671 | 466.6 | 191.7 |

| Uganda | 2749 | 8591 | 7003 | 2873 | 3559 | 61.08 | 10.52 | 341.4 | 44.70 | 6722 | 425.0 | 431.5 |

| Angola | 3771 | 11,984 | 10,671 | 3670 | 4468 | 41.15 | 17.51 | 3079 | 28.65 | 4721 | 334.8 | 161.7 |

| Central African Rep. | 1723 | 10,625 | 8871 | 3181 | 4828 | 45.04 | 7.63 | 2452 | 22.11 | 9221 | 397.6 | 350.5 |

| India Cherry | 4333 | 14,330 | 11,414 | 3554 | 6530 | 35.10 | 13.14 | 3368 | 67.03 | 11,160 | 1069 | 320.7 |

| India Parchment | 292.4 | 11,576 | 9345 | 3716 | 512.2 | 58.35 | 21.48 | 3111 | 39.48 | 10,389 | 601.7 | 771.4 |

| Vietnam | 3841 | 12,591 | 9474 | 3456 | 5574 | 67.52 | 11.49 | 2281 | 31.47 | 8762 | 366.2 | 498.8 |

| Indonesia | 5559 | 12,430 | 9825 | 3739 | 5690 | 91.42 | 17.73 | 2921 | 41.95 | 11,484 | 737.7 | 748.0 |

| Thailand | 3620 | 11,536 | 11,635 | 4316 | 6086 | 176.9 | 26.63 | 4701 | 45.50 | 10,517 | 634.1 | 729.3 |

| Java | 4581 | 11,272 | 8558 | 3096 | 3700 | 33.52 | 5.39 | 3444 | 11.79 | 3777 | 289.6 | 176.1 |

Values are mean (n = 3)

ND not detected

When applying classification trees considering only the species, four equivalent solutions are found, that give a perfect classification of the samples (no misclassification error) with very simple classification rules:

Classify as Arabica if 2-methyl-3-buten-2-ol is greater than 179.09 μg/kg or if acetone is greater than 15,914 μg/kg, otherwise classify as Robusta;

Classify as Arabica if methylbutyrate is lower than 11.59 μg/kg or if pyridine is greater than or equal to 11,655 μg/kg, otherwise classify as Robusta;

Classify as Arabica if diacetyl is greater than or equal to 3777 μg/kg and 2,3-dimethylpyrazine is lower than 726.2 μg/kg or if diacetyl is lower than 3777 μg/kg and propylformate is greater than 38.21 μg/kg, otherwise classify as Robusta;

Classify as Arabica if acetone is greater than or equal to 11,656 μg/kg and 2,3-pentanedione is greater than or equal to 3083 μg/kg and 3-hexanone is lower 1066 μg/kg, otherwise classify as Robusta.

Again, some of the variables involved in the classification rules do not significantly differ in the two species but give an important contribution when considered in conjunction with other variables.

The classification tree derived when jointly considering species and geographical origin again gives a more complex classification rule, that involves several substances. The origin of Robusta samples is identified by 2-butanone (Africa if it is lower than 4913 μg/kg) or methylbutyrate (Asia if it is greater than 26 μg/kg), the Arabica samples have 2-butanone greater than 4913 μg/kg and methylbutyrate lower than 26 μg/kg and can be further classified by origin according to methanol (greater than 3498 μg/kg for South America samples) or to ethylformate (lower than 167 μg/kg for Africa and greater than 167 μg/kg for Central America).

The quality of the classification is lower than in the previous cases: indeed, three Arabica samples from the Caribbean and one from South America are classified as coming from Africa, one Arabica sample coming from Africa is classified as coming from South America, one Arabica sample from the Caribbean and one Robusta sample from Africa are classified as Robusta coming from Asia and two Robusta samples from Asia are classified as coming from Africa. In total 9 samples out of 33 (27% of the entire dataset) are misclassified.

The analytical technique used to characterize the volatile fraction of coffee samples, has several advantages, being quicker, simpler, highly reproducible and yielding ‘true’ aroma profile, very similar to natural olfactory perception. Furthermore, there is little chance of artefact formation, competition phenomena, selective, incomplete or irreversible adsorption and incomplete desorption.

Chemometric evaluation of the data, shows for green beans, as well as for roasted ones, that the two species are very well characterized by few substances. This is quite evident when considering each substance separately (in some cases the separation of the two species is very strong) and even more striking when considering jointly all the substances using classification trees. Indeed, very simple classification rules are able to classify correctly nearly all the observed samples. The same is true when also considering geographical origin, at least for green coffee, while the misclassification error is much higher when considering roasted coffee.

The results are then quite strong and really promising, a validation on a different set of samples would be advisable.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Giuseppe Procida, Email: gprocida@units.it.

Corrado Lagazio, Email: corrado.lagazio@unige.it.

Francesca Cateni, Email: cateni@units.it.

Marina Zacchigna, Email: zacchign@units.it.

Angelo Cichelli, Email: cichelli@unich.it.

References

- Barcarolo R, Casson C, Tutta C. Analysis of the volatile constituents of food by headspace GC-MS with reversal of the carrier gas flow during sampling. J. High Resol. Chromatogr. 1992;15:307–311. doi: 10.1002/jhrc.1240150508. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barcarolo R, Casson P. Modified capillary GC/MS system enabling dynamic head space sampling with on-line cryofocusing and cold on column injection of liquid samples. J. High Resol. Chromatogr. 1997;20:24–28. doi: 10.1002/jhrc.1240200105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand B, Boulanger R, Dussert S, Ribeyre F, Berthiot L, Descroix F, Joet T. Climatic factors directly impact the volatile organic compound fingerprint in green Arabica coffee bean as well as coffee beverage quality. Food Chem. 2012;135:2575–2583. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.06.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffo RA, Cardelli-Freire C. Coffee flavor: An overview. Flavour Fragance J. 2004;19:99–104. doi: 10.1002/ffj.1325. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong MW, Tong KH, Ong JJM, Liu SQ, Curran P, Yu B. Volatile composition and antioxidant capacity of Arabica coffee. Food Res. Int. 2013;51:388–396. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2012.12.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chung HS, Kim DH, Youn KS, Lee JB, Moon KD. Optimization of roasting conditions according to antioxidant activity and sensory quality of coffee brews. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2013;22:23–29. doi: 10.1007/s10068-013-0004-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke RJ, Macrae R. Coffee. Chemistry. London: Elsevier Applied Science Publishers; 1985. pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Colzi I, Taiti C, Marone E, Magnelli S, Gonnelli C, Mancuso S. Covering the different steps of the coffee processing: Can headspace VOC emission be exploited to successfully distinguish between Arabica and Robusta? Food Chem. 2017;237:257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.05.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulsat-Serra N, Quintanilla-Casas B, Vichi S. Volatile thiols in coffee: A review on their formation, degradation, assessment and influence on coffee sensory quality. Food Res. Int. 2016;89:982–988. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2016.02.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flament I. Coffee flavor chemistry. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: Wiley; 2001. pp. 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Grosch W. Evaluation of the key odorants of food by diluition experiments, aroma models and omission. Chem. Senses. 2001;26:533–545. doi: 10.1093/chemse/26.5.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herawati D, Giriwono PE, Dewi FNA, Kashiwagi T, Andarwulan N. Critical roasting level determines bioactive content and antioxidant activity of Robusta coffee beans. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2019;28:7–14. doi: 10.1007/s10068-018-0442-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw JV. Capillary inlet systems for gas chromatographic trace analysis. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 1988;26:142–145. doi: 10.1093/chromsci/26.4.142. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holscher W, Steinhart H. Investigation of roasted coffee freshness with an improved headspace technique. Z. Lebensm. Unters Forsch. 1992;195:33–38. doi: 10.1007/BF01197836. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang LF, Wu MJ, Zhong KJ, Sun X, Liang YZ, Dai YH, Huang KL, Guo F. Fingerprint developing of coffee flavor by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and combined chemometrics methods. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2007;588:216–223. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalua CM, Allen MS, Bedgood DR, Jr, Bishop AG, Prenzler PD, Robards K. Olive oil volatile compounds, flavour development and quality: A critical review. Food Chem. 2007;100:273–286. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.09.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Korhonovà M, Hron K, Klimcikovà D, Muller L, Bednàr P, Bartàk P. Coffee aroma-statistical analysis of compositional data. Talanta. 2005;80:710–715. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2009.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Lee Y, Lee JG, Buglass AJ. Development of a simultaneous multiple solid-phase microextraction-single shot-gas chromatography/mass spectrometry method and application to aroma profile analysis of commercial coffee. J. Chromatogr. A. 2013;1295:21–24. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2013.04.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim D, Kim W, Lee MG, Heo HJ, Chun OK, Kim DO. Evidence for protective effects of coffees on oxidative stress-induced apoptosis through antioxidant capacity of phenolics. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2012;21:1735–1744. doi: 10.1007/s10068-012-0231-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu F, Malosse C, Cain AH, Frérot B. Comparative headspace analysis of fresh red coffee berries from different cultivated varieties of coffee trees. J. High Resol. Chromatogr. 1996;19:298–300. doi: 10.1002/jhrc.1240190513. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mondello L, Costa R, Tranchida PQ, Dugo P, Lo Presti M, Festa S, Dugo G. Reliable characterization of coffee bean aroma profiles by automated headspace solid phase microextraction-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry with the support of a dual-filter mass spectra library. J. Sep. Sci. 2005;28:1101–1109. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200500026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Procida G, Giomo A, Cichelli A, Conte LS. Study of volatile compounds of virgin olive oils and sensory evaluation: a chemometric approach. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2005;85:2175–2183. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Procida G, Pagliuca G, Cichelli A. Geographical differentiation between Italian and Spanish saffron based on volatile fraction composition. A preliminary study. Agro Food Ind. Hi-Tech. 20: 48-53 (2009)

- Procida G, Cichelli A, Lagazio C, Conte LS. Relationships between volatile compounds and sensory characteristics in virgin olive oil by analytical and chemometric approach. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016;96:311–318. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.7096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R. Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Available from: https://www.r-project.org/ Accessed Feb. 10, 2015

- Ribeiro JS, Augusto F, Salva TJG, Thomaziello RA, Ferreira MM. Prediction of sensory properties of Brazilian Arabica roasted coffees by headspace solid phase microextraction-gas chromatography and partial least squares. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2009;634:172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2008.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha S, Maetzu L, Barros A, Cid C, Coimbra MA. Screening and distinction of coffee brew based on headspace solid-phase microextraction/gas chromatography/principal components analysis. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2004;84:43–51. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.1607. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz C, Czerny M, Cid C, Schieberle P. Comparison of potent odorants in a filtered coffee brew and in an instant coffee beverage by aroma extract dilution analysis. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2002;214:299–302. doi: 10.1007/s00217-001-0459-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanon B, Procida G. Effects of including silage in the diet on volatile compound profiles in Montasio cheese and their modification during ripenind. J. Dairy Res. 2004;71:58–65. doi: 10.1017/S0022029903006563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunarharum WB, Williams DJ, Smyth HE. Complexity of coffee flavor: A compositional and sensory perspective. Food Res. Int. 2014;62:315–325. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2014.02.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toci AT, Farah A. Volatile compounds as potential defective coffee beans’ markers. Food Chem. 2008;108:1133–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.11.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toledo PRAB, Pezza L, Pezza HR, Toci AT. Relationship between the different aspects related to coffee quality and their volatile compounds. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2016;15:705–719. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker HE, Lehman KA, Wall MM, Siderhurst MS. Analysis of volatile profiles of green Hawai’ian coffee beans damaged by the coffee berry borer (Hypothenemus hampei) J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019;99:1954–1960. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.9393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yener S, Romano A, Cappellini L, Mark TD, Del Pulgar JS, Gasperi F, Navarini L, Biasiolo F. PTR-ToF-MS characterisation of roasted coffees (C. Arabica) from different geographic origins. J. Mass Spectrom. 49: 929-935 (2014) [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.