Barriers to optimal blood pressure (BP) control in the United States (US)

Between 1988 and 2008, BP control rates (defined as systolic/diastolic BP <140/90 mm Hg) steadily increased from 47% to 69% among US adults with hypertension taking antihypertensive medication.1,2 However, this upward trend has since stagnated at around 70%.3,4 The reasons for this plateau are complex, multifactorial, and likely interrelated. For example, therapeutic inertia, rising obesity rates, high healthcare costs, inequities in access to healthcare, poor dietary choices, and declining rates of physical activity likely all contribute. Despite these pressures, several integrated healthcare systems have successfully increased their BP control rates to >80% with multimodal interventions including patient registries, simplified treatment algorithms, and team-based care.5,6 One part of the success of these programs may be the increased use of fixed-dose combination (FDC) antihypertensive medication products, which reduce daily pill burden and improve adherence.7 Herein, we review the current landscape and potential for FDCs in the management of hypertension in the US.

Underutilization of combination antihypertensive therapy

Most patients require two or more antihypertensive medication classes to achieve adequate BP control. Monotherapy may only be successful in 10–33% of patients, perhaps even less with the more intensive BP goals recommended by the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines.8 Accordingly, data from the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) suggest that nearly all patients (87%) require at least two antihypertensive classes to achieve more intensive systolic BP goals (systolic BP <120 mm Hg).9 This is consistent with data from a meta-analysis of randomized trials showing the superior BP-lowering effect of combination therapy over monotherapy, with an equivalent safety profile.10

Both the US and European BP guidelines currently recommend initial combination antihypertensive therapy for most patients with systolic/diastolic BP ≥140/90 mm Hg, either as an FDC regimen or free-equivalent products.11,12 However, monotherapy has long occupied a precedent in hypertension management. Historically, US guidelines recommended (and clinicians practiced) a stepped-care approach to initial therapy for most patients.11 The stepped-care approach involves initiation of a single agent, with up-titration of the dose or conversion to a different monotherapy prior to the addition of another antihypertensive class. Consistent with this practice, recent data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) show that 40% of US adults with uncontrolled BP (≥140/90 mm Hg) take only one antihypertensive medication class.3 The findings suggests that a suboptimal antihypertensive medication regimen may contribute, in large part, to uncontrolled BP rates.

Underutilization of FDC antihypertensive therapy

FDC antihypertensive products represent one strategy to increase the use of combination therapy. Kaiser Permanente Northern California increased use of the FDC lisinopril/hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) from <1% to >27% as part of a multi-modal intervention that increased BP control rates from 44% to >80%.5 However, FDC antihypertensive products are perhaps not commonly used outside of integrated health systems. In NHANES 2005–2016, only 23% of US adults taking antihypertensive medication were using at least one FDC product.3 National prescription sales data also show low and declining FDC use from 17% to 14% between 2009 and 2014.13 Only 16% of commercial claims for initial hypertension management between 2009 and 2013 were for FDC products.14 A shift in the hypertension treatment paradigm is needed to promote earlier use of combination therapy and FDCs in the treatment sequence for most patients.

Barriers to broader use of FDC antihypertensive therapy

One potential barrier to FDC use is insufficient availability of FDC products that contain the number of medication classes often needed to successfully meet BP goals. At the time of this editorial, there are 33 Food and Drug Administration-approved FDC products for hypertension available in the US (Table 1). The majority contain two medication classes in one pill (31/33, 94%). Only two products contain three medication classes in one pill, both of which are composed of an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), a calcium channel blocker (CCB), and HCTZ. No products are commercially available that contain four medications in one pill. The lack of a four-medication FDC product may represent an important unmet need, as there is a growing body of evidence showing that low-dose triple and quadruple antihypertensive medication therapy provides superior or equivalent BP lowering with a reduced risk of adverse effects compared with fewer medications at standard doses.15–18 To achieve an intensive systolic BP goal of <120 mm Hg, data from SPRINT indicate that 32% and 24% of patients will need at least three and four antihypertensive medication classes, respectively.9

Table 1.

Commercially available antihypertensive fixed-dose combination products in the United States, as of February 2020.

| Antihypertensive medication class combination | Generic name | Brand name | Generic available | Doses available |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACEI/thiazide diuretic | ||||

| Quinapril/HCTZ | Accuretic™ | Yes | 10/12.5mg, 20/12.5mg, 20/25mg | |

| ARB/thiazide diuretic | ||||

| Valsartan/HCTZ | Diovan HCT® | Yes | 80/12.5mg, 160/12.5mg, 320/12.5mg, 160/25mg, 320/25mg | |

| ACEI/CCB | ||||

| Trandolapril/verapamil | Tarka | Yes | 1/240mg, 2/180mg, 2/240mg, 4/240mg | |

| ARB/CCB | ||||

| Valsartan/amlodipine | Exforge | Yes | 160/5mg, 320/5mg, 160/10mg, 320/10mg | |

| ARB/CCB/thiazide diuretic | ||||

| Valsartan/amlodipine/HCTZ | Exforge HCT® | Yes | 5/160/12.5mg, 5/160/25mg, 10/160/12.5mg, 10/160/25mg, 10/320/25mg | |

| Beta-blocker/thiazide diuretic | ||||

| Propranolol/HCTZ | (none) | Yes | 40/25mg, 80/25mg | |

| Potassium-sparing diuretic/thiazide diuretic | ||||

| Triamterene/HCTZ | Dyazide®, Maxzide® | Yes | 25/37.5mg, 50/75mg | |

| Aldosterone antagonist/thiazide diuretic | Spironolactone/HCTZ | Aldactazide® | Yes | 25/25mg, 50/50mg† |

| Alpha-2-agonist/thiazide diuretic | Methyldopa/HCTZ | (none) | Yes | 250/15mg, 250/25mg |

| Direct renin inhibitor/thiazide diuretic | Aliskiren/HCTZ | Tekturna HCT | No | 150/12.5mg, 150/25mg, 300/12.5mg, 300/25mg |

ACEI: angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB: angiotensin receptor blocker; CCB: calcium channel antagonist; HCTZ: hydrochlorothiazide; rx: prescription

Available in 1/240mg formulation in branded Tarka® product only.

Available in 50/50mg formulation in branded Aldactazide® product only.

Another barrier to FDC use is the limited selection of specific medications available within each medication class and the doses available. Notably, of 26 FDCs containing a thiazide diuretic, 23 (88%) contain HCTZ, two contain chlorthalidone, and one contains bendroflumethiazide. Also, there are no thiazide diuretic/CCB dual-therapy FDCs. Such a product would be a significant addition for treating women who are or wish to become pregnant,19 and/or to provide evidence-based combination therapy for African Americans, who generally respond better to CCBs and thiazides compared to ACEIs, ARBs, and beta-blockers.20,21 Only one dual-therapy FDC product contains spironolactone, an important medication for the management of resistant hypertension. Lisinopril 40mg, a commonly used dose in practice, is not available in any FDC product. Additionally, HCTZ doses <25mg are ubiquitous in FDC products, which are not sufficiently potent to elicit a substantial BP-lowering effect.

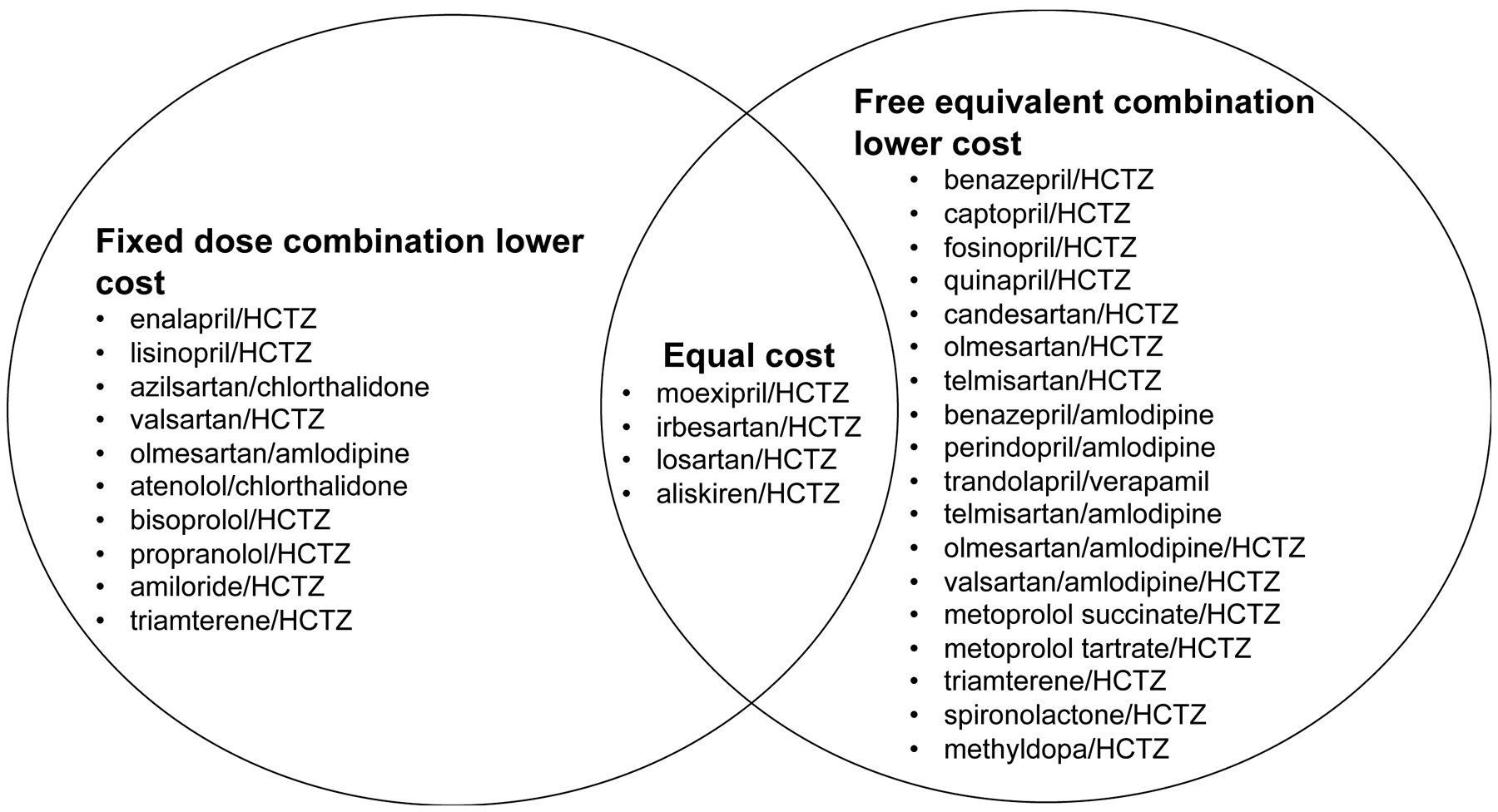

Generic availability, cost, and insurance coverage of FDC products are also important considerations for clinicians. At the time of this editorial, the majority (29/33, 88%) of FDC products are generically available, but there is a wide variation in average monthly cost to patients and insurers between and within class combinations. Only four FDCs are brand-only products (azilsartan/chlorthalidone [Edarbyclor], perindopril/amlodipine [Prestalia], metoprolol succinate/HCTZ [Dutoprol®], and aliskiren/HCTZ [Tekturna HCT]). However, generic products are not necessarily affordable or accessible to all patients. Generic FDC products may still be expensive for patients because 1) the insurer requires a prior authorization or step therapy and may still deny the prescription; 2) the patient has a high prescription deductible or medication copay; or 3) the patient has no prescription insurance coverage. The frequency and reasons that prescription insurers reject claims for FDC products in favor free-equivalent combinations is unclear. One potential reason may be that significant price differences exist between an FDC pill and free-equivalent combinations, even if the FDC product is generically available (Table 2). For example, for a benazepril/amlodipine regimen, the average Medicare Part D total monthly cost is $16.80 for one FDC pill, compared to $7.50 if prescribed with two pills. Of 32 regimens with FDC and free-equivalent product availability, only 10 (31%) are cheaper as FDC products compared to free-equivalent counterparts (Figure 1). Some lower-cost FDC products are available on low-cost pharmacy lists and are frequently prescribed for patients. For example, lisinopril/HCTZ and losartan/HCTZ are the two most frequently prescribed ACEI/thiazide and ARB/thiazide FDC products, respectively, with the greatest annual Medicare dispenses for their respective classes (Table 3).

Table 2.

Total monthly cost differences between free equivalent and fixed-dose combination regimens.

| Medication combination | Free equivalent combination | Fixed-dose combination | Cost Difference (FDC – Free equivalent) | Less expensive regimen | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual cost | Sum of individual costs | Cost | |||

| $6.75 | $33.30 | $26.55 | Free equivalent | ||

| HCTZ | $2.85 | ||||

| $38.85 | $62.40 | $23.55 | Free equivalent | ||

| HCTZ | $2.85 | ||||

| $15.45 | $7.50 | $−7.95 | FDC | ||

| HCTZ | $2.85 | ||||

| $10.05 | $28.50 | $18.45 | Free equivalent | ||

| HCTZ | $2.85 | ||||

| $6.15 | $3.00 | $−3.15 | FDC | ||

| HCTZ | $2.85 | ||||

| $29.85 | $27.90 | $−1.95 | Equal | ||

| HCTZ | $2.85 | ||||

| $10.95 | $19.20 | $8.25 | Free equivalent | ||

| HCTZ | $2.85 | ||||

| $209.40 | $178.20 | $−31.20 | FDC | ||

| Chlorthalidone | $24.30 | ||||

| $71.25 | $83.70 | $12.45 | Free equivalent | ||

| HCTZ | $2.85 | ||||

| $14.25 | $15.90 | $1.65 | Equal | ||

| HCTZ | $2.85 | ||||

| $7.65 | $6.00 | $−1.65 | Equal | ||

| HCTZ | $2.85 | ||||

| $107.55 | $116.40 | $8.85 | Free equivalent | ||

| HCTZ | $2.85 | ||||

| $34.05 | $81.60 | $47.55 | Free equivalent | ||

| HCTZ | $2.85 | ||||

| $20.85 | $14.40 | $−6.45 | FDC | ||

| HCTZ | $2.85 | ||||

| $7.50 | $16.80 | $9.30 | Free equivalent | ||

| $27.00 | $153.90 | $126.90 | Free equivalent | ||

| $45.90 | $94.80 | $48.90 | Free equivalent | ||

| Verapamil | $33.90 | ||||

| $108.30 | $84.60 | $−23.70 | FDC | ||

| Amlodipine | $3.60 | ||||

| $33.80 | $100.80 | $67.00 | Free equivalent | ||

| Amlodipine | $3.60 | ||||

| $21.60 | $34.80 | $13.20 | Free equivalent | ||

| Amlodipine | $3.60 | ||||

| $111.15 | $131.40 | $20.25 | Free equivalent | ||

| HCTZ | $2.85 | ||||

| $24.45 | $96.60 | $72.15 | Free equivalent | ||

| HCTZ | $2.85 | ||||

| $27.30 | $16.50 | $−10.80 | FDC | ||

| Chlorthalidone | $24.30 | ||||

| $17.55 | $5.10 | $−12.45 | FDC | ||

| HCTZ | $2.85 | ||||

| $17.85 | $196.80 | $178.95 | Free equivalent | ||

| HCTZ | $2.85 | ||||

| $4.95 | $29.40 | $24.45 | Free equivalent | ||

| HCTZ | $2.85 | ||||

| n/a | $91.20 | n/a | n/a | ||

| Bendroflumethiazide | n/a | ||||

| $32.85 | $29.40 | $−3.45 | FDC | ||

| HCTZ | $2.85 | ||||

| $19.95 | $13.50 | $−6.45 | FDC | ||

| HCTZ | $2.85 | ||||

| $292.65 | $6.30 | $−286.35 | FDC | ||

| HCTZ | $2.85 | ||||

| $8.85 | $29.40 | $20.55 | Free equivalent | ||

| HCTZ | $2.85 | ||||

| $9.75 | $44.10 | $34.35 | Free equivalent | ||

| HCTZ | $2.85 | ||||

| $193.05 | $194.10 | $1.05 | Equal | ||

| HCTZ | $2.85 | ||||

ACEI: angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB: angiotensin receptor blocker; CCB: calcium channel antagonist; FDC: fixed-dose combination; HCTZ: hydrochlorothiazide.

Cost data were generated from the 2014–2018 Medicare Part D Drug Spending Data available from the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Information-on-Prescription-Drugs/MedicarePartD). The medication costs represent ingredient costs, dispensing fees, taxes, and patient out-of-pocket costs, inflated to 2019 US Dollars and averaged over the one-year calendar year; however, they do not reflect manufacturer rebates. The cost represents per 30 tablets of the generic product, if available. Costs are averaged across manufacturers.

Figure 1.

Antihypertensive regimens that are lower cost when prescribed as a fixed dose combination pill or free equivalent products.

HCTZ: hydrochlorothiazide

Table 3.

Number of Medicare prescriptions dispensed for each antihypertensive fixed-dose combination product in the United States in 2018.

| Antihypertensive medication class combination | Generic name Brand name |

Generic dispenses | Brand dispenses |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACEI/thiazide diuretic | |||

| Moexipril/HCTZ Uniretic® |

10,290 | 0 | |

| ARB/thiazide diuretic | |||

| Azilsartan/chlorthalidone Edarbyclor |

0 | 67,752 | |

| ACEI/CCB | |||

| Perindopril/amlodipine Prestalia |

0 | 14 | |

| ARB/CCB | |||

| Telmisartan/amlodipine Twynsta® |

686,682 | 279 | |

| ARB/CCB/thiazide diuretic | |||

| Valsartan/amlodipine/ HCTZ Exforge HCT® |

87,652 | 2,499 | |

| Beta-blocker/thiazide diuretic | |||

| Metoprolol succinate/HCTZ Dutoprol® |

0 | 1,237 | |

| Potassium-sparing diuretic/thiazide diuretic | |||

| Amiloride/HCTZ (none) |

71,435 | 0 | |

| Aldosterone antagonist/thiazide diuretic | Spironolactone/HCTZ Aldactazide® |

265,366 | 1,064 |

| Alpha-2-agonist/thiazide diuretic | Methyldopa/HCTZ (none) |

812 | 0 |

| Direct renin inhibitor/thiazide diuretic | Aliskiren/HCTZ Tekturna HCT |

0 | 13,210 |

ACEI: angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB: angiotensin receptor blocker; CCB: calcium channel antagonist; HCTZ: hydrochlorothiazide; rx: prescription

Utilization data were generated from the 2014–2018 Medicare Part D Drug Spending Data available from the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Information-on-Prescription-Drugs/MedicarePartD).

Several logistical concerns may limit FDC use in clinical practice. One challenge is that separate medication components within FDCs cannot be tailored individually. This limits a clinician’s flexibility to easily titrate medications according to patient needs or discriminate which medication may be causing a nonspecific side effect (e.g., dizziness). Non-adherence may be more impactful to a patient taking FDCs compared to those taking free-equivalent combinations. For example, if a patient stops taking their one, triple-therapy FDC pill, they have no antihypertensive coverage, compared with at least partial coverage if they stop taking one of three individual pills. Clinicians also may have varied perceptions about FDC costs, formulary availability, effectiveness, safety, and role in hypertension treatment.22 Qualitative data exploring these clinical perceptions are needed to inform interventions around FDC use. Finally, implementation studies are needed to develop effective interventions for increasing FDC use and evaluate impact on BP control. Team-based care strategies, such as pharmacist-delivered medication therapy management, should be tested.

Future directions

Options for FDC products containing an ACEI or ARB and HCTZ therapy are quite robust. However, several important gaps in the armamentarium of FDC antihypertensive products need to be addressed. First, a wider array of FDC options containing triple- or quadruple-therapy is needed to translate emerging evidence, such as the benefits of low-dose combination therapy, into clinical practice. This is especially important given that patients will likely require more medications to achieve the more intensive BP goals recommended in recent guidelines. Second, more FDC products should incorporate chlorthalidone and/or spironolactone. Among the thiazide diuretics, chlorthalidone provides the most consistent and robust data supporting a reduction in cardiovascular outcomes.9,23,24 Spironolactone is the preferred agent for most patients with resistant hypertension, as supported by recent data from the PATHWAY-2 study.25 However, spironolactone is not available in any triple- or quadruple-therapy FDCs. Products incorporating spironolactone may assist with adherence for patients with resistant hypertension, who require at least three medication classes to achieve BP control. Additional FDC products are needed which incorporate doses commonly used in clinical practice (e.g., lisinopril 40 mg) or other medications used to treat comorbid cardiovascular diseases (i.e., anti-anginal, anti-platelet, and anti-hyperlipidemic agents). Additional research is needed to: 1) explore clinician perspectives of antihypertensive FDC use; 2) describe the frequency and reasons for insurer denials of antihypertensive FDC prescriptions; 3) ensure access to FDC products is equitable for all patients; and 4) develop and evaluate effective interventions to increase FDC products.

Summary and conclusions

Increasing use of combination therapy is crucial to achieve more intensive BP goals recommended in clinical practice guidelines. By providing combination therapy in one pill, FDCs are promising agents for the treatment of hypertension, but these products are underutilized. More aggressive use of the available safe, effective, and generic FDC products may help to restore the upward trend in BP control rates in the US.

Funding:

Dr. Bress is supported by K01HL133468 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Derington is supported by research funds received to her institution from Amgen, Inc. and Amarin Corporation for research unrelated to the current manuscript. Dr. Cohen is supported by K23HL133843 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Derington is a past recipient of American Heart Association grant #19POST34380226/Derington/2019.

REFERENCES

- 1.Egan BM, Zhao Y, Axon RN. US Trends in Prevalence, Awareness, Treatment, and Control of Hypertension, 1988–2008. JAMA 2010; 303: 2043–2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hajjar I, Kotchen TA. Trends in Prevalence, Awareness, Treatment, and Control of Hypertension in the United States, 1988–2000. J Am Med Assoc 2003; 290: 199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Derington CG, King JB, Herrick JS, Shimbo D, Kronish IM, Saseen JJ et al. Trends in antihypertensive medication monotherapy and combination use among US adults, NHANES 2005–2016. Hypertension 2020; 75: 973–981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang Y, Moran AE. Trends in the Prevalence, Awareness, Treatment, and Control of Hypertension Among Young Adults in the United States, 1999 to 2014. Hypertension 2017; 70: 736–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaffe MG, Young JD. The Kaiser Permanente Northern California Story: Improving Hypertension Control From 44% to 90% in 13 Years (2000 to 2013). J Clin Hypertens 2016; 18: 260–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fletcher RD, Amdur RL, Kolodner R, McManus C, Jones R, Faselis C et al. Blood pressure control among US veterans: A large multiyear analysis of blood pressure data from the veterans administration health data repository. Circulation 2012; 125: 2462–2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Du L-P, Cheng Z-W, Zhang Y-X, Li Y, Mei D. The impact of fixed-dose combination versus free-equivalent combination therapies on adherence for hypertension: A meta-analysis. J Clin Hypertens 2018; 20: 902–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mensah GA, Bakris G. Treatment and Control of High Blood Pressure in Adults. Cardiol Clin 2010; 28: 609–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wright Jr. JT, Williamson J, Whelton P, Snyder J, Sink K, Roccoo M et al. A Randomized Trial of Intensive versus Standard Blood-Pressure Control. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 2103–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paz MA, De-La-Sierra A, Sáez M, Barceló MA, Rodríguez JJ, Castro S et al. Treatment efficacy of anti-hypertensive drugs in monotherapy or combination: ATOM systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials according to PRISMA statement. Med 2016; 95: e4071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr, Collins KJ, Dennisson Himmelfarb C et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical P. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018; 71: e127–e248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering Wi, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M et al. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 3021–3104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ritchey M, Tsipas S, Loustalot F, Wozniak G. Use of Pharmacy Sales Data to Assess Changes in Prescription-and Payment-Related Factors that Promote Adherence to Medications Commonly Used to Treat Hypertension, 2009 and 2014. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0159366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lauffenburger JC, Landon JE, Fischer MA. Effect of Combination Therapy on Adherence Among US Patients Initiating Therapy for Hypertension: a Cohort Study. J Gen Intern Med 2017; 32: 619–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bennett A, Chow CK, Chou M, Dehbi HM, Webster R, Salam A et al. Efficacy and Safety of Quarter-Dose Blood Pressure-Lowering Agents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Hypertension 2017; 70: 85–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Webster R, Salam A, De Silva HA, Selak V, Stepien S, Rajapakse S et al. Fixed low-dose triple combination antihypertensive medication vs usual care for blood pressure control in patients with mild to moderate hypertension in Sri Lanka a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2018; 320: 566–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chow CK, Thakkar J, Bennett A, Hillis G, Burke M, Usherwood T et al. Quarter-dose quadruple combination therapy for initial treatment of hypertension: placebo-controlled, crossover, randomised trial and systematic review. Lancet 2017; 389: 1035–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salam A, Atkins ER, Hsu B, Webster R, Patel A, Rodgers A. Efficacy and safety of triple versus dual combination blood pressure-lowering drug therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Hypertens 2019; 37: 1567–1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice Bulletin No. 203: Chronic hypertension in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2019; 133: e26–e50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jamerson K, DeQuattro V. The impact of ethnicity on response to antihypertensive therapy. Am J Med 1996; 101: 22S–32S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cushman WC, Reda DJ, Perry HM, Williams D, Abdellatif M, Materson BJ. Regional and racial differences in response to antihypertensive medication use in a randomized controlled trial of men with hypertension in the United States. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160: 825–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tocci G, Borghi C, Volpe M. Clinical management of patients with hypertension and high cardiovascular risk: Main results of an italian survey on blood pressure control. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev 2014; 21: 107–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.SHEP Cooperative Research Group. Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. Final results of the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP). JAMA 1991; 265: 3255–3264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Major Outcomes in High-Risk Hypertensive Patients Randomized to or Calcium Channel Blocker vs Diuretic. JAMA 2002; 288: 2981–2997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams B, Macdonald TM, Morant S, Webb DJ, Sever P, McInnes G et al. Spironolactone versus placebo, bisoprolol, and doxazosin to determine the optimal treatment for drug-resistant hypertension (PATHWAY-2): A randomised, double-blind, crossover trial. Lancet 2015; 386: 2059–2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]