Abstract

Domoic acid (DA), the focus of this research, is a marine algal neurotoxin and epileptogen produced by species in the genus Pseudo-nitzschia. DA is found in finfish and shellfish across the globe. The current regulatory limit for DA consumption (20 ppm in shellfish) was set to protect humans from acute toxic effects, but there is a growing body of evidence suggesting that regular consumption of DA contaminated seafood at or below the regulatory limit may lead to subtle neurological effects in adults. The present research uses a translational nonhuman primate model to assess neurophysiological changes after chronic exposure to DA near the regulatory limit. Sedated electroencephalography (EEG) was used in 20 healthy adult female Macaca fascicularis, orally administered 0.075 and 0.15 mg DA/kg/day for at least 10 months. Paired video and EEG recordings were cleaned and a Fast Fourier Transformation was applied to EEG recordings to assess power differences in frequency bands from 1–20 Hz. When DA exposed animals were compared to controls, power was significantly decreased in the delta band (1–4 Hz, p<0.005) and significantly increased in the alpha band (5–8 Hz, p<0.005), theta band (9–12 Hz, p<0.01), and beta band (13–20 Hz, p<0.05). The power differences were not dose dependent or related to the duration of DA exposure, or subtle clinical symptoms of DA exposure (intentional tremors). Alterations of power in these bands have been associated with a host of clinical symptoms, such as deficits in memory and neurodegenerative diseases, and ultimately provide new insight into the subclinical toxicity of chronic, low-dose DA exposure on the adult primate brain.

Keywords: Domoic acid, electroencephalography, nonhuman primate, chronic exposure, power spectrum density

1. Introduction

Over the past several decades, a rapidly changing global environment has led to increasing algal blooms worldwide (Wells et al., 2020). While some blooms may not impact human or wildlife health, other blooms contain algal toxins that can cause health effects in mammalian species (Backer and Miller, 2016; Berdalet et al., 2015; Grattan et al., 2016b). One algal toxin of emerging concern is domoic acid (DA), a small, excitatory amino acid produced by marine algae in the genus Pseudo-nitzschia.

DA is a glutamate receptor agonist that primarily binds with high affinity to 2-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-isoxazole-4-propionic acid (AMPA) and kainic acid (KA) type receptors and causes typical glutamate excitotoxity (Debonnel et al., 1989; Stewart et al., 1990). Its toxicity was not documented until 1987, when a mass poisoning occurred, afflicting over 100 people with seizures, memory loss, and death (Cendes et al., 1995; Perl et al., 1990a, 1990b). At high levels, DA targets the temporal lobe, with gross neurotoxicity (necrosis and vacuolization) observed in the hippocampus, thalamus, and amygdala (Carpenter, 1990; Cendes et al., 1995). In subacute studies, DA induces status epilepticus in rats when administered 1 mg/kg/h ip for 3–5 hrs (Muha and Ramsdell, 2011; Tiedeken and Ramsdell, 2013). DA has also been associated with an elevated risk of developing adult epilepsy or spontaneous seizures in naturally exposed sea lions (Ramsdell and Gulland, 2014). In these models, there is extensive neuronal damage, possibly attributable to the injury during seizures (Kirkley et al., 2014), as well as chronic deficits in memory (Cook et al., 2015). Additionally, a number of reports detail that chronic exposure to very low levels (below the current regulatory limit) of DA is associated with memory deficits in humans (Grattan et al., 2018, 2016a). Despite this, the existing body of literature on the effects of prolonged exposure to levels of DA near the human regulatory limit lacks any investigation of the subclinical neurophysiological changes that are linked to seizures and epilepsy.

Current regulatory limits in North America close fisheries when DA levels in shellfish reach 20 ppm DA (Wekell et al., 2004). This threshold was established based on information regarding DA levels associated with clinical symptoms in humans (~200 ppm) and a ten-fold safety factor (Perl et al., 1990b). Estimates suggest that, with the 20 ppm limit for shellfish, an adult consumes 0.075–0.1 mg DA/kg bodyweight per meal of seafood (Mariën, 1996; Toyofuku, 2006). Since 1987, there has been no documentation of acute human DA toxicity, but environmental factors are changing today’s oceans. In the last 30 years, there has been an increase in the frequency, severity and duration of toxic algal blooms, including DA blooms (McKibben et al., 2017; Wells et al., 2015). These changing DA algal bloom dynamics could lead to more frequent exposures to levels of DA at or below the current regulatory limit.

While seizures and other abnormal limb activities after DA exposure have been well documented in acutely exposed laboratory and wildlife animals alike (Dakshinamurti et al., 1991; Fujita et al., 1996; Iverson et al., 1989; Ramsdell and Gulland, 2014; Tryphonas et al., 1990), it remains unclear if lower level exposures to DA may have effects on neuroelectrophysiology. In the present investigation, we used electroencephalography (EEG) in a cohort of adult, female Macaca fascicularis chronically exposed to 0.075 and 0.15 mg DA/kg/day to investigate the effects of DA on the power spectrum of neuroelectric activity measured by EEG.

EEG signals reflect the total amount of neuroelectric activity generated in the cortex, with contributing noise from the skull, scalp, dura, and surrounding electrical interference. Power is a quantitative EEG (qEEG) measure that originates from the signaling of large, pyramidal neurons in the cortex, hippocampus and amygdala (Kirschstein and Kohling, 2009) and uses the Fast Fourier Transformation to describe the strength of the signal at a given frequency. Dramatic increases in power are frequently observed in epilepsy, but, in silent epilepsy and absence seizures (i.e. petit mal seizures), these increases can be mild and within normal parameters (Clemens et al., 2000). Alternatively, discordant changes in bands can be indicative of psychiatric disorders, neurodegenerative disease, or the engagement of specific tasks, such as in memory and learning challenges (Harmony, 2013; Newson and Thiagarajan, 2019). Thus, even subtle changes in EEG bandpower may be indicative of larger neuroelectrical aberrations. The goals of this study were to employ noninvasive EEG methods in sedated animals to evaluate differences in EEG bandpower after chronic exposure to DA near the human regulatory limit.

2. Methods

2.1. Animals and Study Protocol

For this study, a subset of 20 adult female Macaca fascicularis were selected from the cohort described in Burbacher et al., 2019. Age ranged between 6 and 11 years (mean: 7 years), and weight ranged between 2.8 and 4.8 kg (mean: 3.5 kg). Animals were singly housed in stainless steel cages, with visual and grooming contact access to an adjacent animal, in the Infant Primate Research Center at the Washington National Primate Research Center. Room temperature was maintained at approximately 24°C, with a 12-hour light-dark cycle. All animals were fed Purina Monkey Chow twice daily and were supplied with regular environmental enrichment that included fresh fruit and vegetables, frozen foraging treats, and cereals, grains, and other treats. All animal protocols strictly adhered to the Animal Welfare Act and the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Research Council and protocols were approved by the University of Washington Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Original study procedures and exposure monitoring protocols are described in detail in Burbacher et al. (2019). In brief, animals were exposed to either 0 (n=7), 0.075 (n=6), or 0.15 (n=8) mg/kg DA/day via an oral solution of 5% sucrose water for 306 to 596 days (mean: 429.6 ± SEM: 22.7), during which all but one female conceived and delivered a single infant (see Supplement 1). Testers performed clinical assessments at least 3x/week to track animal’s ability to visually orient and track a small piece of fresh produce, and then fully extend an arm to retrieve the treat. During the reaching task, hand/arm tremors were recorded as either present or absent. Testers were blind to the animal’s assignment and maintained an 80% reliability with the primary tester.

2.2. Experimental Design

All adult females underwent three sedated EEGs, for a total of 60 recordings. EEGs were conducted in the morning. The first and second EEGs were recorded 1.5 hours post dosing, and the third EEG was recorded 24 hours post-dosing. Each EEG occurred a minimum of 3 days apart, to assure the animal was fully recovered before undergoing sedation again. Animals were sedated for EEGs with 4 mg/kg im Telozol®, a combination of tiletamine and zolazepam (Zoetis Services LLC, Parsippany, NJ, USA), and monitored until fully sedate. Once sedated, animals were removed from the homecage and brought to a quiet testing suite for EEG acquisition. Females were prepped and closely monitored throughout EEG acquisition, as described below.

2.3. EEG Procedures and Acquisition

EEGs were acquired using an Avatar EEG 4000 Series Recorder (Avatar EEG Solutions Inc., Calgary, AB, Canada), equipped with eight 6-mm gold electrodes. Electrode cables were braided together to minimize sources of noise and cleaned with an alcohol wipe before each use. After the subject was fully sedated, the head was shaved and cleaned with alcohol, before applying electrodes with Ten20 conductive paste (Weaver and Company, Aurora, CO, USA) in approximation to the international 10–20 system locations F3/F4, T3/T4, P3/P4. A reference electrode was applied in the center of the head, and a ground electrode was applied to the left mid-back. Electrodes application was typically achieved within 15 minutes of sedation. All EEG sessions were paired with video monitoring to ensure that any movement during the session would be removed during preprocessing. EEGs were recorded for a minimum of 20 minutes or until the animal was waking from sedation. All impedances were kept below <100 kΩ and were checked at the beginning of the session and at least once during the session after electrodes had settled. Once the recording was complete, all electrode paste was removed, and the animal was returned to her homecage and monitored until fully awake.

2.4. EEG Processing and Power Calculation

Recordings were processed and analyzed in Matlab using the FieldTrip toolkit and a standardized method to analyze power from EEG recordings (Oostenveld et al., 2011). To minimize differences in sedation state, a 2–3-minute window was identified in all recordings at the same time post administration of the sedative (24 minutes post-injection). Once this window was identified, EEG recordings were synced with the paired video, and any segment with noticeable head movement, large facial movement (e.g. yawning), or electrode wire movement were removed from the recording, using the ft_databrowser function. Two independent, blinded testers reviewed each recording for epileptic and spike activity. After checking for epileptic activity, recordings were converted into Matlab files and preprocessed with ft_preprocessing to remove higher order trends from the data. Recordings were then divided into 1-second segments, and the ft_rejectvisualartifact graphical user interface was used to visually inspect the variance of each segment. Any segment outside of the normal variance in that recording was removed from further analysis. Whole recordings were excluded if: 1) the animal was resistant to sedation or 2) if more than 25% of total time was removed from the EEG. For each animal, the first EEG recording that met these criteria was used for analysis. All recordings from a single animal in the control group was rejected due to a lack of sedation on all 3 EEG recordings. Thus, the animals included in the analysis were 6 control animals, 6 in the 0.075 mg/kg group, and 8 in the 0.15 mg/kg group.

After preprocessing, recordings were unblinded and then band pass filtered at 50 Hz to remove harmonics. Timeseries data were segmented into 1-second epochs. Absolute and relative power (% of total power observed in each frequency) was calculated with FieldTrip function ft_freqanalysis using a Hanning window and with multitapered Fast Fourier Transformation, yielding power values expressed in 1 Hz frequency bands from 1–50 Hz.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

To understand if exposure to DA affected the distribution of power, FieldTrip’s ft_freqstatistics function was used. This uses nonparametric Monte Carlo simulation with a two-tail correction to estimate the significant probabilities of difference in power distributions between dose groups. The two-tailed alpha was set at 0.05, and distributions were compared at each channel and frequency from 1–50 Hz.

To compare frequency bands of interest that have previously been shown to be affected by DA (Scallet et al., 2004), two multivariate analysis of covariances (MANCOVAs) were conducted in R (R Core Team, 2020), using data averaged across the entire primate head. The initial analysis examined differences between DA exposed animals and controls, using DA exposure duration and tremor scores as covariates. A second analysis examined whether or not the DA effects were dose dependent, again using DA exposure duration and tremor scores as covariates. Outcome variables included total power in the frequency bands of interest: delta (1–4 Hz), theta (5–8 Hz), alpha (9–12 Hz), and beta (13–20 Hz). Any significant dependent variables in the MANCOVAs were further assessed with post-hoc testing using a Bonferroni correction applied to the p-values from the four bands of interest. Group differences were considered significant when the post-hoc Bonferroni corrected p-value was less than 0.05.

3. Results

After artifact removal and visual inspection of the EEG recordings, 13 of the 60 total EEGs were excluded, primarily due to an animal’s lack of sedation during the recording (see exclusion criteria above). Overall, recordings were clean, without many artifacts, and amplitudes were low, as expected for sedated recordings (Supplement 2). No epileptic or spike activity was identified on any recording. On two recordings from one control animal, we captured distinct electrooculographic (EOG) artifacts across multiple sessions, which, to the best of our knowledge, have never been documented in this species before (Supplement 3). When observed, the EOG artifact occurred simultaneously on all channels. Notably, paired video-capture did not show any signs of body movement or eye blinking, but only displayed subtle, closed-eyelid movements.

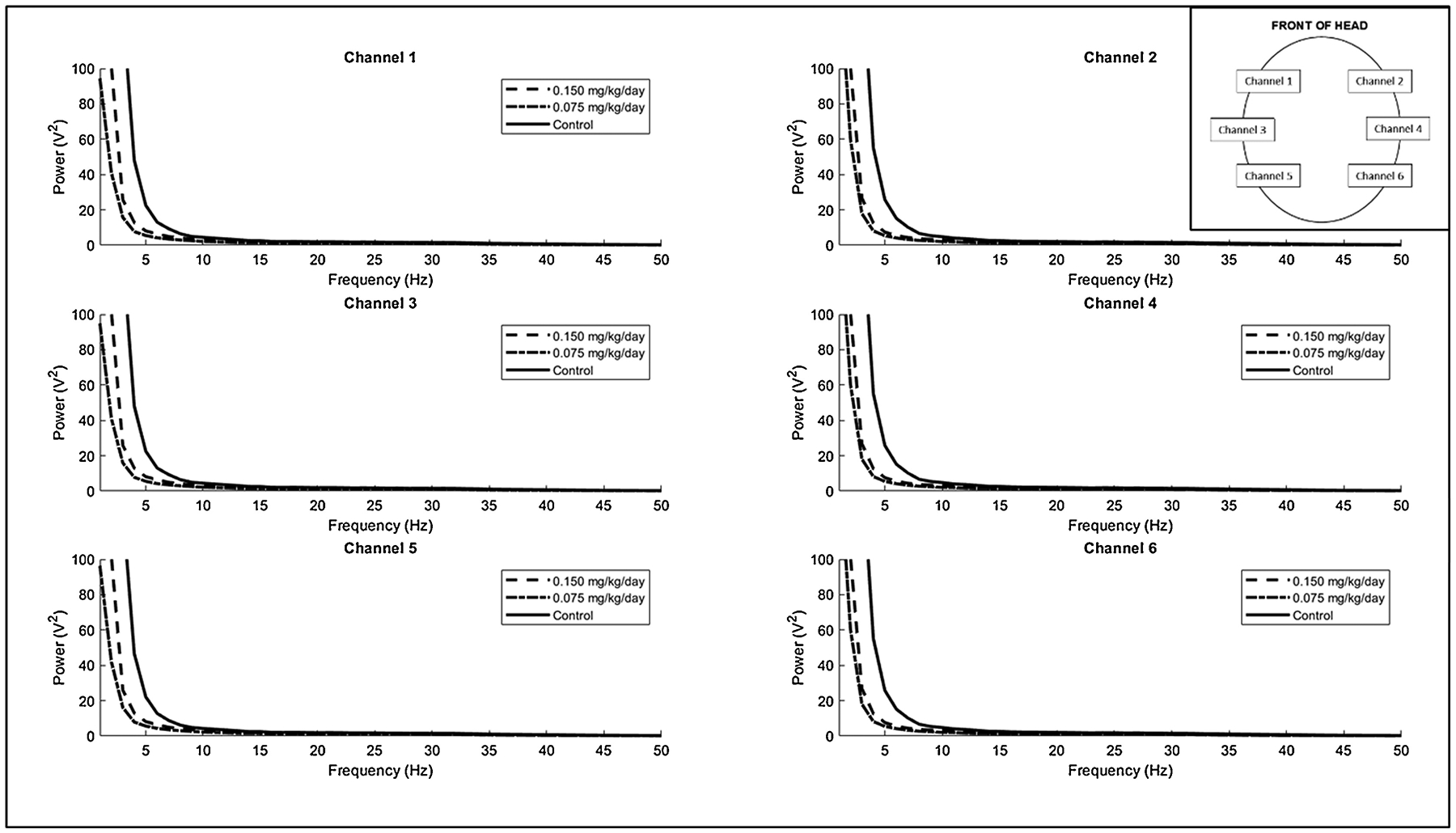

Unsurprisingly and likely due to volume conduction across the small primate head, power distributions across all animals were highly similar on all electrodes on the same side of the head, and somewhat similar between each hemisphere (Fig. 1). Using a Monte Carlo simulation to compare the absolute and relative power spectrum between exposed and control groups across all frequencies, we found that there were no significant differences in the overall distributions between dose groups (Fig. 1).

Figure 1:

The group mean power spectral density across all frequencies for each channel on the EEG recording. Inset shows the position of each channel on the head.

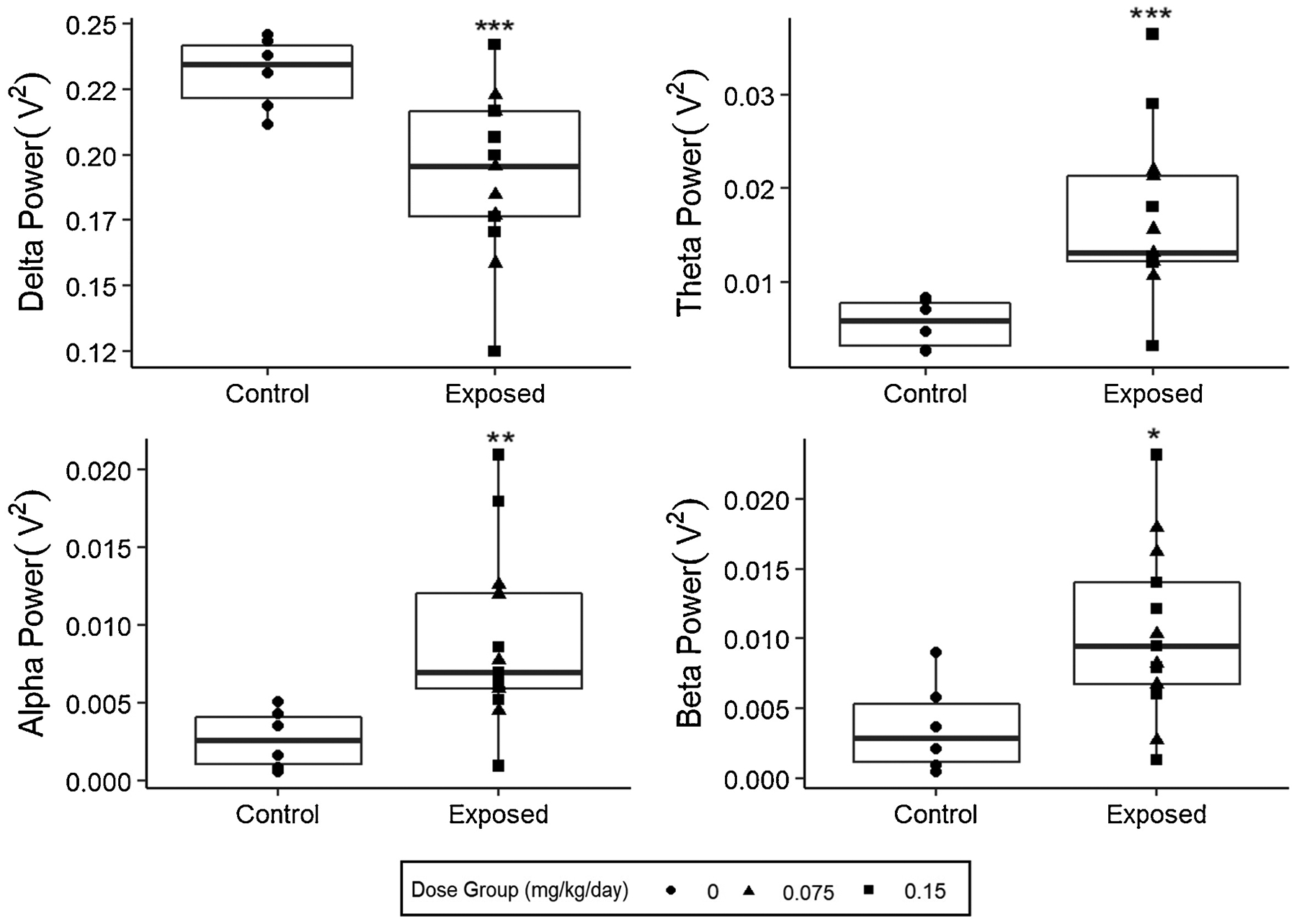

Preassessment with the bands of interest (delta (1–4 Hz), theta (5–8 Hz), alpha (9–12 Hz), and beta (13–20 Hz)) confirmed that variances in each band were similar between each group, and power was normally distributed, thus the assumptions for MANCOVA testing were met. The initial analysis examining the effects of any DA exposure indicated a significant effect of DA exposure (p < 0.05, Table 1) that was not related to the duration of exposure to DA or tremors (p >0.05). This relationship, however, was not dose dependent, even when accounting for duration of exposure and tremor scores (p > 0.05, Table 2). Post-hoc testing using a t-test and Bonferroni correction to compare differences between the exposed and control groups in all bands revealed that all bands were affected, but in different directions (Table 3, Fig. 2). Mean differences between the exposed and unexposed groups were: −0.04 V2 for delta power (adjusted-p=0.004); 0.011 V2 for theta (adjusted-p=0.002); 0.006 V2 for alpha (adjusted-p=0.009); 0.0068 V2 for beta (adjusted-p=0.024).

Table 1:

MANCOVA results for exposure only assessments

| Exposure Only | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pillai | Approximate F-statistic | p | |

| Exposure Status | 0.557 | 3.78 | 0.033 |

| Tremor Score | 0.308 | 1.33 | 0.314 |

| Days Exposed | 0.462 | 2.58 | 0.091 |

Table 2:

MANCOVA results for dose-response assessments

| Dose-Response | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pillai | Approximate F-statistic | p | |

| 0.15 mg/kg | 0.314 | 1.26 | 0.34 |

| 0.075 mg/kg | 0.478 | 2.52 | 0.10 |

| Tremor Score | 0.311 | 1.24 | 0.35 |

| Days Exposed | 0.465 | 2.39 | 0.11 |

Table 3:

Post-Hoc Testing of Exposure

| Exposed Mean | Unexposed Mean | Difference | p-value | adj.p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delta | 0.19 | 0.23 | −0.04 | 0.001 | 0.004 |

| Theta | 0.0168 | 0.0055 | 0.0113 | 0.0006 | 0.0024 |

| Alpha | 0.0089 | 0.0026 | 0.0063 | 0.002 | 0.009 |

| Beta | 0.0105 | 0.0037 | 0.0068 | 0.006 | 0.024 |

Figure 2:

Comparison of the mean total absolute power spectral density over the given frequency band among exposure groups. Each point overlay represents a single individual in the group. (*adj. p-value<0.05,**adj. p-value <0.01, ***adj. p-value<0.005)

4. Discussion

Domoic acid (DA) is a common marine algal neurotoxin that is becoming more widespread under changing oceanic conditions (Wells et al., 2020). It is well documented that acute exposure to DA (>1 mg/kg) can cause seizures and epilepsy (Cendes et al., 1995; Fujita et al., 1996; Gulland et al., 2002; Teitelbaum et al., 1990) and increased electroencephalography (EEG) power in all frequencies have been documented in humans, sea lions, and rodents after acute DA exposure (Cendes et al., 1995; Fujita et al., 1996; Gulland et al., 2002; Teitelbaum et al., 1990). Despite these clear effects at high levels, there is presently little research regarding changes in EEG following long-term exposure to DA at levels near the human regulatory limit (0.075–0.1 mg/kg). Recent evidence from human and animal models suggests that chronic, low-level DA exposure may be related to other subtle neurological changes in motor responses (intention tremors in nonhuman primates, see Burbacher et al., 2019) and challenges with regular daily activities involving everyday memory and cognition in humans (Grattan et al., 2018, 2016a) and mouse models (Lefebvre et al., 2017).

The present research used EEG to assess chronic, low-level neuroelectric power effects in the nonhuman primate model, Macaca fascicularis, exposed to 0.075–0.15 mg DA/kg/day. Results from a power spectrum analysis demonstrated that animals exposed to DA have decreased power in the delta band and increased power in the alpha, theta, and beta bands. These changes in electrophysiology were not dose dependent or related to clinical symptomology (intention tremors) previously reported in some of the DA exposed females. Proportionately, animals with the highest median power in delta had the lowest median power in all other bands and tended to be in the control group (n=5/10). Similarly, animals with the lowest median delta power had the highest median power in other bands, and most were exposed animals (n=8/10).

EEG power is a quantitative measure that reflects the action and signaling of large, pyramidal neurons in the cortex, hippocampus and amygdala (Kirschstein and Köhling, 2009). Power can be divided into several frequency bands, each related to many different cognitive and neurological functions. The delta band is comprised of brain oscillations from the slowest frequency band in the EEG assessment and typically ranges from 0–4 Hz, and dominates deep sleep and basic homeostatic resting states (Başar et al., 1999; Knyazev, 2012). Delta also reflects most inhibitory responses of functional processing (Herrmann et al., 2016). Theta is comprised of oscillations in the 5–8 Hz range, and alpha ranges from 9–12 Hz. These two closely connected bands are often connected to memory and cognition, but frequently operate in opposite directions during tasks (i.e. when one increases, the other decreases) (Herrmann et al., 2016; Klimesch, 1999). Beta rhythms are between 13 and 20 Hz and have been linked to sensory and motor tasks and processing. While each band is often known for specific processing tasks, broad spectral changes across several bands have been identified as collectively reflective of performance on memory and learning tests (Finnigan and Robertson, 2011) and many psychiatric disorders (Newson and Thiagarajan, 2019), even during resting states. DA exposed macaques had decreased delta power in EEGs, and increased power in the theta and alpha bands. Decreases in low frequency power have been observed in neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson and Alzheimer’s disease (Bosboom et al., 2009; Poza et al., 2007); whereas increases in higher frequencies have been linked to psychiatric disorders, such as depression (Hinrikus et al., 2009).

These findings bear careful interpretation, because it is not clearly evident how the different power bands are translated across individuals and across species. Previous EEG research in Macaca fascicularis suggests that most resting EEG activity lies in the delta band, which aligns with our findings (Authier et al., 2009). In humans, however, resting-state EEG power is much more broadly distributed across bands (Hooper, 2005). Additionally, we used a sedative that contains two active ingredients: tiletamine, a relative of ketamine, and zolazepam, a benzodiazepine. These two sedatives interact with the NMDA and GABA pathways, respectively, and are not known to cause changes in the lower frequency oscillations (Choi, 2017). However, benzodiazepines are used to treat seizures and, in high, sedative doses, benzodiazepines result in excessive activity in the beta band (Van Lier et al., 2004). While we did not observe any seizure-like spikes or discharges in DA exposed females, any seizure-like activity may have been suppressed under sedation. Still, all sedation effects were balanced between dosed and control animals; so, while sedation likely had some effects on the results reported here, the observed differences are notable and necessitate further investigation.

The results of the present study collectively suggest that chronic exposure to DA near the current human regulatory limit may result in subtle changes in EEG, possibly reflecting changes in pyramidal neurons. While the functional effects of these EEG changes are not evident from the current study, continued research efforts should focus on how chronic ingestion of real-world levels of DA may be related to neurophysiological and other neurological changes in human populations across the globe.

Supplementary Material

Supplement 2: Ten second sample of raw EEG recording from one control animal, midway through the session.

Supplement 3: Displays the distinct electrooculographic (EOG) artifacts from one animal. Each vertical line represents a 1-second interval.

Highlights.

Domoic acid is a common marine neurotoxin and epileptogen

Adult macaques were orally exposed to domoic acid near the human regulatory limit

Sedated EEGs were administered to monkeys and power was measured

Exposed animals had decreased delta power and increased alpha, theta, beta power

Further research is needed to understand functional effects of power changes

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the staff and volunteers of the Center on Human Development and Disability (CHDD), Infant Primate Research Laboratory and the University of Washington National Primate Research Center for their skilled assistance in this research.

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the U.S. National Institutes of Health R01 ES023043, P51 OD010425, HD083091 and NCATS Grant TL1 TR000422 (SS).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Authier S, Paquette D, Gauvin D, Sammut V, Fournier S, Chaurand F, Troncy E, 2009. Video-electroencephalography in conscious non human primate using radiotelemetry and computerized analysis: Refinement of a safety pharmacology model. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 60, 88–93. 10.1016/J.VASCN.2008.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backer LC, Miller M, 2016. Sentinel Animals in a One Health Approach to Harmful Cyanobacterial and Algal Blooms. Vet. Sci 3, 8 10.3390/vetsci3020008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Başar E, Başar-Eroglu C, Karakaş S, Schürmann M, 1999. Are cognitive processes manifested in event-related gamma, alpha, theta and delta oscillations in the EEG? Neurosci. Lett 259, 165–168. 10.1016/S0304-3940(98)00934-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berdalet E, Fleming LE, Gowen R, Davidson K, Hess P, Backer LC, Moore SK, Hoagland P, Enevoldsen H, 2015. Marine harmful algal blooms, human health and wellbeing: Challenges and opportunities in the 21st century. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. United Kingdom 96, 61–91. 10.1017/S0025315415001733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosboom JLW, Stoffers D, Wolters EC, Stam CJ, Berendse HW, 2009. MEG resting state functional connectivity in Parkinson’s disease related dementia. J. Neural Transm 116, 193–202. 10.1007/s00702-008-0132-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burbacher T, Grant K, Petroff R, Crouthamel B, Stanley C, McKain N, Shum S, Jing J, Isoherranen N, 2019. Effects of chronic, oral domoic acid exposure on maternal reproduction and infant birth characteristics in a preclinical primate model. Neurotoxicol. Teratol 440354 10.1101/440354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter S, 1990. The Human Neuropathology of Encephalopathic Mussel Toxin Poisoning. Symp. Domoic Acid Toxic 73–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cendes F, Andermann F, Carpenter S, Zatorre RJ, Cashman NR, 1995. Temporal lobe epilepsy caused by domoic acid intoxication: Evidence for glutamate receptor–mediated excitotoxicity in humans. Ann. Neurol 37, 123–126. 10.1002/ana.410370125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi B-M, 2017. Characteristics of electroencephalogram signatures in sedated patients induced by various anesthetic agents. J. Dent. Anesth. Pain Med 17, 241 10.17245/jdapm.2017.17.4.241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens B, Szigeti G, Barta Z, 2000. EEG frequency profiles of idiopathic generalised epilepsy syndromes. Epilepsy Res. 42, 105–115. 10.1016/S0920-1211(00)00167-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook PF, Reichmuth C, Rouse AA, Libby LA, Dennison SE, Carmichael OT, Kruse-Elliott KT, Bloom J, Singh B, Fravel VA, Barbosa L, Stuppino JJ, Van Bonn WG, Gulland FMD, Ranganath C, 2015. Algal toxin impairs sea lion memory and hippocampal connectivity, with implications for strandings. Science (80-.) 350, 1545–1547. 10.1126/science.aac5675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dakshinamurti K, Sharma SK, Sundaram M, 1991. Domoic acid induced seizure activity in rats. Neurosci. Lett 127, 193–197. 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90792-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debonnel G, Beauchesne L, Montigny C. de, 1989. Domoic acid, the alleged mussel toxin, might produce its neurotoxic effect through kainate receptor activation: an electrophysiological study in the rat dorsal hippocampus. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol 67, 29–33. 10.1139/y89-005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnigan S, Robertson IH, 2011. Resting EEG theta power correlates with cognitive performance in healthy older adults. Psychophysiology 48, 1083–1087. 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2010.01173.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita T, Tanaka T, Yonemasu Y, Cendes F, Cashman NR, Andermann F, 1996. Electroclinical and pathological studies after parenteral administration of domoic acid in freely moving nonanesthetized rats: An animal model of excitotoxicity. J. Epilepsy 9, 87–93. 10.1016/0896-6974(95)00075-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grattan LM, Boushey CJ, Liang Y, Lefebvre KA, Castellon LJ, Roberts KA, Toben AC, Morris JGJ, 2018. Repeated dietary exposure to low levels of domoic acid and problems with everyday memory: Research to public health outreach. Toxins (Basel). 10, 103 10.3390/toxins10030103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grattan LM, Boushey CJ, Tracy K, Trainer VL, Roberts SM, Schluterman N, Morris JGJ, 2016a. The association between razor clam consumption and memory in the CoASTAL cohort. Harmful Algae 57, 20–25. 10.1016/j.hal.2016.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grattan LM, Holobaugh S, Morris JGJ, 2016b. Harmful algal blooms and public health. Harmful Algae. 10.1016/j.hal.2016.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulland FMD, Haulena M, Fauquier D, Langlois G, Lander ME, Zabka TS, Duerr R, 2002. Domoic acid toxicity in Californian sea lions (Zalophus californianus): clinical signs. Vet. Rec 150, 475–480. https://doi.org/doi: 10.1136/vr.150.15.475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmony T, 2013. The functional significance of delta oscillations in cognitive processing. Front. Integr. Neurosci 10.3389/fnint.2013.00083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann CS, Strüber D, Helfrich RF, Engel AK, 2016. EEG oscillations: From correlation to causality. Int. J. Psychophysiol 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2015.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinrikus H, Suhhova A, Bachmann M, Aadamsoo K, Võhma Ü, Lass J, Tuulik V, 2009. Electroencephalographic spectral asymmetry index for detection of depression. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput 47, 1291–1299. 10.1007/s11517-009-0554-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper GS, 2005. Comparison of the distributions of classical and adaptively aligned EEG power spectra. Int. J. Psychophysiol 55, 179–189. 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2004.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iverson F, Truelove J, Nera E, Tryphonas L, Campbell J, Lok E, 1989. Domoic acid poisoning and mussel-associated intoxication: Preliminary investigations into the response of mice and rats to toxic mussel extract. Food Chem. Toxicol 27, 377–384. 10.1016/0278-6915(89)90143-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkley KS, Madl JE, Duncan C, Gulland FMD, Tjalkens RB, 2014. Domoic acid-induced seizures in California sea lions (Zalophus californianus) are associated with neuroinflammatory brain injury. Aquat. Toxicol 156, 259–268. 10.1016/j.aquatox.2014.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschstein T, Köhling R, 2009. What is the source of the EEG? Clin. EEG Neurosci 40, 146–149. 10.1177/155005940904000305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimesch W, 1999. EEG alpha and theta oscillations reflect cognitive and memory performance: A review and analysis. Brain Res. Rev 10.1016/S0165-0173(98)00056-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knyazev GG, 2012. EEG delta oscillations as a correlate of basic homeostatic and motivational processes. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre KA, Kendrick PS, Ladiges W, Hiolski EM, Ferriss BE, Smith DR, Marcinek DJ, 2017. Chronic low-level exposure to the common seafood toxin domoic acid causes cognitive deficits in mice. Harmful Algae 64, 20–29. 10.1016/j.hal.2017.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariën K, 1996. Establishing tolerable dungeness crab (Cancer magister) and razor clam (Siliqua patula) domoic acid contaminant levels. Environ. Health Perspect 104, 1230–6. 10.1289/ehp.961041230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKibben SM, Peterson W, Wood AM, Trainer VL, Hunter M, White AE, 2017. Climatic regulation of the neurotoxin domoic acid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 114, 239–244. 10.1073/pnas.1606798114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muha N, Ramsdell JS, 2011. Domoic acid induced seizures progress to a chronic state of epilepsy in rats. Toxicon 57, 168–171. 10.1016/j.toxicon.2010.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newson JJ, Thiagarajan TC, 2019. EEG Frequency Bands in Psychiatric Disorders: A Review of Resting State Studies. Front. Hum. Neurosci 12 10.3389/fnhum.2018.00521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oostenveld R, Fries P, Maris E, Schoffelen J-M, 2011. FieldTrip: Open Source Software for Advanced Analysis of MEG, EEG, and Invasive Electrophysiological Data. Comput. Intell. Neurosci 2011 10.1155/2011/156869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perl TM, Bedard L, Kosatsky T, Hockin JC, Todd EC, McNutt LA, Remis RS, 1990a. Amnesic shellfish poisoning: a new clinical syndrome due to domoic acid. Canada Dis. Wkly. Rep 16 Suppl 1, 7–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perl TM, Bedard L, Kosatsky T, Hockin JC, Todd ECD, 1990b. An outbreak of toxic encephalopathy caused by eating mussels contaminated with domoic acid. N. Engl. J. Med 322, 1775–1780. 10.1056/NEJM199006213222504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poza J, Hornero R, Abásolo D, Fernández A, García M, 2007. Extraction of spectral based measures from MEG background oscillations in Alzheimer’s disease. Med. Eng. Phys 29, 1073–1083. 10.1016/j.medengphy.2006.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team, 2020. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. https://doi.org/http://www.R-project.org/

- Ramsdell JS, Gulland FMD, 2014. Domoic acid epileptic disease. Mar. Drugs 12, 1185–1207. 10.3390/md12031185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scallet A, Kowalke PK, Rountree RL, Thorn BT, Binienda ZK, 2004. Electroencephalographic, behavioral, and c-fos responses to acute domoic acid exposure. Neurotoxicol. Teratol 26, 331–342. 10.1016/j.ntt.2003.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart GR, Zorumski CF, Price MT, Olney JW, 1990. Domoic acid: A dementia-inducing excitotoxic food poison with kainic acid receptor specificity. Exp. Neurol 110, 127–138. 10.1016/0014-4886(90)90057-Y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teitelbaum J, Zatorre RJ, Carpenter S, Gendron D, Cashman NR, 1990. Neurological Sequelae of Domoic Acid Intoxication. Symp. Domoic Acid Toxic 16, 9–12. 10.2174/13816128236661701241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiedeken JA, Ramsdell JS, 2013. Persistent neurological damage associated with spontaneous recurrent seizures and atypical aggressive behavior of domoic acid epileptic disease. Toxicol. Sci 133, 133–143. 10.1093/toxsci/kft037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyofuku H, 2006. Joint FAO/WHO/IOC activities to provide scientific advice on marine biotoxins (research report). Mar. Pollut. Bull 52, 1735–1745. 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2006.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tryphonas L, Truelove J, Iverson F, Todd ECD, Nera E, 1990. Neuropathology of experimental domoic acid poisoning in nonhuman primates and rats. Symp. Domoic Acid Toxic 78–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Lier H, Drinkenburg WHIM, Van Eeten YJW, Coenen AML, 2004. Effects of diazepam and zolpidem on EEG beta frequencies are behavior-specific in rats. Neuropharmacology 47, 163–174. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wekell JC, Jurst J, Lefebvre K.a, 2004. The origin of the regulatory limits for PSP and ASP toxins in shellfish. J. Shellfish Res 23, 927–930. [Google Scholar]

- Wells ML, Karlson B, Wulff A, Kudela R, Trick C, Asnaghi V, Berdalet E, Cochlan W, Davidson K, De Rijcke M, Dutkiewicz S, Hallegraeff G, Flynn KJ, Legrand C, Paerl H, Silke J, Suikkanen S, Thompson P, Trainer VL, 2020. Future HAB science: Directions and challenges in a changing climate. Harmful Algae 91, 101632 10.1016/j.hal.2019.101632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells ML, Trainer VL, Smayda TJ, Karlson BSO, Trick CG, Kudela RM, Ishikawa A, Bernard S, Wulff A, Anderson DM, Cochlan WP, 2015. Harmful algal blooms and climate change: Learning from the past and present to forecast the future. Harmful Algae 49, 68–93. 10.1016/j.hal.2015.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplement 2: Ten second sample of raw EEG recording from one control animal, midway through the session.

Supplement 3: Displays the distinct electrooculographic (EOG) artifacts from one animal. Each vertical line represents a 1-second interval.