Abstract

Introduction:

Over the last 30 years, early intervention services (EIS) for first-episode psychosis (FEP) were gradually implemented in the province of Quebec. Such implementation occurred without provincial standards/guidelines and policy commitment to EIS until 2017. Although the literature highlights essential elements for EIS, studies conducted elsewhere reveal that important EIS components are often missing. No thorough review of Quebec EIS practices has ever been conducted, a gap we sought to address.

Methods:

Adopting a cross-sectional descriptive study design, an online survey was distributed to 18 EIS that existed in Quebec in 2016 to collect data on clinical, administrative, training, and research variables. Survey responses were compared with existing EIS service delivery recommendations.

Results:

Half of Quebec’s population had access to EIS, with some regions having no programs. Most programs adhered to essential components of EIS. However, divergence from expert recommendations occurred with respect to variables such as open referral processes and patient–clinician ratio. Nonurban EIS encountered additional challenges related to their geography and lower population densities, which impacted their team size/composition and intensity of follow-up.

Conclusions:

Most Quebec EIS offer adequate services but lack resources and organizational support to adhere to some core components. Recently, the provincial government has created EIS guidelines, invested in the development of new programs and offered implementation support from the National Centre of Excellence in Mental Health. These changes, along with continued mentoring and networking of clinicians and researchers, can help all Quebec EIS to attain and maintain recommended quality standards.

Keywords: first-episode psychosis, mental health services, early intervention, schizophrenia, government mental health policy, clinical practice guidelines, evidence-based medicine

Abstract

Introduction:

Au cours des 30 dernières années, les programmes d’interventions pour premiers épisodes psychotiques (PIPEP) ont été graduellement implantés dans la province de Québec. Jusqu’en 2017, cette implantation a eu lieu sans lignes directrices/normes provinciales ni engagement politique. Bien que la littérature fait état de composantes essentielles des PIPEP, des études menées ailleurs révèlent que des composantes importantes des PIPEP sont souvent omises. Aucune recension exhaustive des pratiques des PIPEP du Québec n’a été menée auparavant, lacune que nous avons tenté de combler.

Méthodes:

Suivant un devis d’étude transversal et descriptif, un sondage en ligne a été distribué aux 18 PIPEP en fonction au Québec en 2016 pour recueillir des données sur les variables cliniques, administratives, de formation et de recherche. Les réponses au sondage ont été comparées avec les recommandations sur la prestation des PIPEP.

Résultats:

La moitié de la population du Québec avait accès aux PIPEP, mais certaines régions n’avaient pas de programme. La plupart des programmes adhéraient aux composantes essentielles des PIPEP. Toutefois, il y avait des écarts avec les recommandations d’experts quant à certaines composantes tels les processus de référence et les ratios patients/clinicien. Les PIPEP non urbains éprouvaient des difficultés additionnelles en lien avec la géographie et la densité de population plus faible de leur territoire, qui avaient des répercussions sur la taille/composition de leur équipe et sur l’intensité du suivi.

Conclusions:

La plupart des PIPEP du Québec offrent des services adéquats, mais manquent de ressources et de soutien administratif pour adhérer à des composantes fondamentales. Récemment, le gouvernement a créé des lignes directrices pour les PIPEP, investi dans l’élaboration de nouveaux programmes et offert du soutien à l’implantation avec le Centre national d’excellence en santé mentale. Ces changements, parallèlement au mentorat et au réseautage entre cliniciens et chercheurs pourraient aider tous les PIPEP du Québec à atteindre et à maintenir les standards de qualité recommandés.

Introduction

Multiple studies reveal that the implementation of essential components of EIS remains heterogeneous.1–3 A 2016 Canadian survey of 11 academic EIS found that while they generally followed existing standards and guidelines, there was significant variance in the extent to which essential care components were offered.4 The availability of guidelines alone may not be sufficient, and specific funding, mentoring, and auditing of fidelity to standards may be required to ensure consistency in the quality of programs.1,4–6

In Quebec, over a 30-year period, clinicians developed EIS without provincial standards/guidelines or policy commitments which only emerged in 2017. A provincial association of EI programs, the Association québécoise des programmes pour premiers épisodes psychotiques (AQPPEP), formed in 2004, has supported EIS through continuing education, training, and networking around the use of clinical guidelines. No thorough review of Quebec EIS practices has ever been conducted.

The Quebec government’s latest 5-year mental health plan7 envisaged the development of EIS in all regions by 2020. In 2017, the ministry of health and social services committed funding to develop 15 new EIS8, appointed an advisor at the Centre national d’excellence en santé mentale (CNESM) to support program implementation and published provincial EIS standards.9,10 Our aim was to investigate the extent to which Quebec EIS established before 2016 (i.e., before these policy changes occurred) adhered to internationally recognized standards and thereby establish a baseline against which Quebec EIS can be measured in the future.

Methods

Adopting a cross-sectional descriptive study design, an online survey assessing clinical and administrative variables was distributed to 18 Quebec EIS that existed in 2016. All programs consented to their data being published as reported here. Responses were reviewed in relation to existing EIS recommendations, which are summarized in previous work.4

These recommendations were extracted from national and international guidelines on EIS for psychosis or articles on essential components of EIS. Clinical guidelines from the United Kingdom,11–14 Australia,15 New Zealand,16 Italy,17 and from four Canadian provinces (British Columbia,3 Ontario,18,19 New Brunswick,20 and Nova Scotia21,22) identified through PubMed, PsycINFO, and Google Scholar search were studied.

Half the surveyed EIS were in small cities (<150,000 inhabitants), semirural or rural areas, and the rest were attached to urban academic programs. These two sets of EIS were compared to elucidate additional challenges that smaller rural services may face and their impacts on service functioning.

Results

Seventeen of the 18 EIS responded to the survey. Two were excluded from the analysis of specific survey sections for which they had provided incomplete data. Table 1 presents the results of the survey regarding the implementation of the recommended core components of EIS.

Table 1.

Expert Recommendations Regarding Core Elements of EIS for FEP, Their Rationale, and Survey Results Describing Actual Practices around Those Core Elements for Quebec Programs.

| Core element | Expert Recommendation | Rationale | Survey Results Regarding Actual Practices |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inclusion diagnostic criteria |

|

||

| Exclusion criteria |

|

|

|

| Accessibility |

|

|

|

| Maximize engagement |

|

|

|

| Access to specific EIS ward/beds |

|

||

| Age at intake |

|

|

|

| Youth at ultrahigh risk for psychosis (UHR-P) |

|

||

| Biopsychosocial interventions |

|

|

|

| Case management |

|

|

|

| Team composition |

|

|

|

| Training and continuing education |

|

|

|

| Program duration and discharge orientation |

|

||

| Clinical and research evaluation |

|

|

|

| Program evaluation |

|

|

|

| Research activities |

|

|

|

Note. N = 17. EIS = early intervention services; AQPPEP = Association québécoise des programmes pour premiers épisodes psychotiques; FEP: first-episode psychosis; CBT: cognitive behavioural therapy.

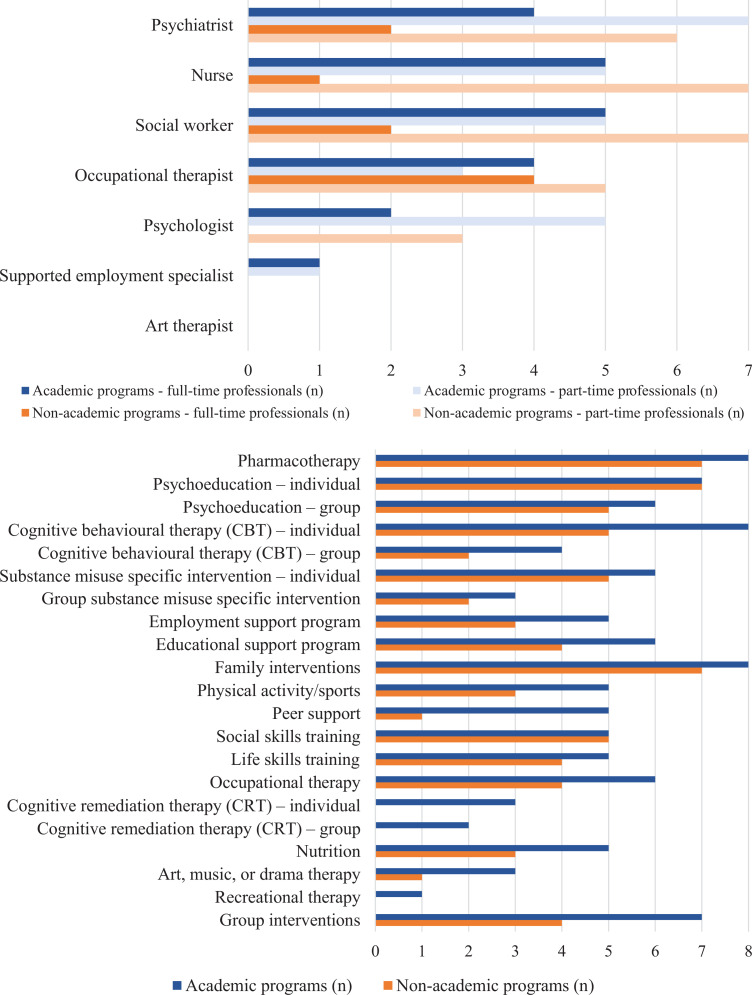

Detailed program and patient characteristics are reported in Table 2. Figure 1 shows the differences in access to mental health professionals in surveyed EIS and the variety of psychosocial interventions they offered.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the Surveyed EIS for FEP in Quebec, as of 2016.

| Program characteristics | Program Name | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Implementation year | 1999 | 1988 | 2002–2003 | 2010 | 1999 | 1994 | 2009 | 2014 | 2014 | 2004 | 2009 | 2001 | 2014 | 2014 | 2009 | 2005 | 2005 | |

| Location | Large city | Large city | Large city | Large city | Large city | Large city | Large city | Small city/rural area | Small city/rural area | Small city/rural area | Small city/rural area | Small city/rural area | Suburban area | Suburban area | Large city | Large city | Large city | |

| Population covered | 225,000 | 370,000 | 400,000 | 150,000 | 600,000 | 600,000 | 125,000 | 100,000 | 85,000 | 77,000 | 192,000 | 200,000 | 120,200 | 160,000 | 59,000 | Québec, supra-regional | 300,000 | |

| Program statistics | Referrals per year | 90 | 155 | 156 | 30 | 50 | 70 | 32 | 28 | 15 | 30 | 20 | 35 | 53 | 50 | 50 | ||

| Accepted new cases per year | 67 | 140 | 55 | 25 | 45 | 55 | 24 | 17 | 12 | 25 | 12 | 32 | 25 | 50 | ||||

| Accepted new cases per year per 100,000 population | 30 | 38 | 14 | 17 | 8 | 9 | 24 | 20 | 16 | 13 | 6 | 27 | 42 | |||||

| Services | Program duration | 5 years | 5 years | 2 years | 2 years | 3 years | > 5 years | 5 years | 5 years | 5 years | 3 years | 5 years | 5 years | 3 years | 3 years | 3 years | No maximum | No maximum |

| Services for UHR patients | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Specific hospital beds | 6 | 12 | 10 | Yes | 10 | No | No | No | No | 3 | No | No | No | No | 8 | Yes | Yes | |

| Patient to case manager ratio | 30:1 | No case management | 19–23:1 | 15–20:1 | 8–20:1 | No case management | 20:1 | 17:1 | 25:1 | 15:1 | NA | 24:1 | 16–18:1 | 10:1 | NA | |||

| Admission criteria | Age range | 17–30 | 18–35 | 14–35 | 16–35 | 18–30 | 18–30 | 13–30 | 14–28 | 16–35 | 15–28 | 18–35 | 17–35 | 17–35 | 12–17 | < 17 | 6–17 | |

| Maximum length of psychosis prior to treatment | No maximum | No maximum | No maximum | No maximum | No maximum | No maximum | No maximum | No maximum | No maximum | No maximum | 2 years | 2 years | No maximum | No maximum | No maximum | No maximum | No maximum | |

| Maximum length of prior treatment with ATP medication | 1 year | 5 years | 1 month | 1 month | 6 months | No maximum | 1 month | No maximum | 2 years | No maximum | No maximum | No maximum | 6 months | 6 months | 1month | No maximum | No maximum | |

| Inclusion of affective psychosis | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Inclusion of substance-induced psychosis | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | |

| Inclusion of concurrent of acquired brain injury/developmental disorders | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Inclusion of concurrent epilepsy | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Inclusion of concurrent mental retardation | Yes | No | No | No | Yes, if mild | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes, if mild | No | Yes | No | |

| Inclusion despite legal problems | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | ||

| Accessibility/early detection | School, community clinic or self-referral are accepted | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | ||

| Targeted maximum delay after between referral and first contact with patient | 24 hr | 2 weeks | 3 days | 4 days | 1 month | No maximum | 1 week | 3 days | 3 days | 3 days | 1 week | 1 week | 1 week | No maximum | No maximum | |||

| Targeted maximum delay after between referral and face-to-face full assessment | 2 weeks | 2 weeks | 1 week | 2 weeks | No maximum | No maximum | 1 week | 2 weeks | 1 week | 1 week | 1 week | 1 week | 1 week | No maximum | No maximum | |||

| Targeted maximum delay after between referral and entry into program | 2 weeks | 2 months | 2 weeks | No maximum | No maximum | No maximum | 1 week | No maximum | 1 week | 3 months | 3 weeks | No maximum | 1 week | No maximum | No maximum | |||

| Average time for entry into program | 1 week | 1 month | 1 week | 1 week | 1,5 month | 1 month | 2 days | 1 month | 3–4 days | 1 month | 3 weeks | 5 days | 24 hours | 1–2 weeks | 2–3 weeks | |||

| Public education | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | ||

| Direct education of sources of referral | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | ||

| Standardized processes | Use of clinical practice guidelines | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Formal protocol for initial assessment | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | |||

| Regular use of standardized evaluation tools | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | |||

| Formal process for evaluation of patient and treatment outcome | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | |||

| Evaluation for quality assurance | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | |||

| Education and research | Continuing education within program | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | ||

| Research within program | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | |||

| Patient characteristics | Average age at admission | 23 | 24,5 | 23 | 22 | 21 | 18 | 20 | 19 | 23 | 22 | 22 | 15 | 15,5 | 16 | |||

| % studying at admission | 25 | 50 | 15 | 22 | 25 | 20 | 25 | 60 | 50 | 98 | 95 | 95 | ||||||

| % working at admission | 45 | 20 | 15 | 20 | 25 | 50 | 25 | 20 | 50 | 0 | 3 | 0 | ||||||

| % living with their family at admission | 40 | 60 | 80 | 70 | 60 | 67 | 50 | 60 | 80 | 95 | 95 | 95 | ||||||

| % living independently at admission | 55 | 40 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 33 | 50 | 40 | 20 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| First Nation (%) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 2 | 0 | ||||

| Visible minorities (%) | 33 | 60 | 35 | 15 | 15 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 10 | 25 | 5 | 80 | ||||

| First-generation immigrants (%) | 25 | 40 | 18 | 35 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 10 | 2 | 10 | |||||

| Second-generation immigrants (%) | 20 | 15 | 48 | 25 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 15 | 4 | 70 | |||||

| Use of antipsychotics < 1 month prior to admission | 35 | N/A | 3 | 95 | 40 | 99 | 90 | 20 | 70 | N/A | 95 | 70 | ||||||

| Use of antipsychotics 1–3 months | 35 | N/A | 1 | 5 | 40 | 10 | 30 | 15 | N/A | 5 | 15 | |||||||

| Use of antipsychotics 3–6 months | 20 | N/A | 0 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 20 | 10 | N/A | 0 | 3 | |||||||

| Use of antipsychotics > 6 months | 10 | N/A | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 20 | 5 | N/A | 0 | 2 |

Note. EIS = early intervention services; UHR = ultrahigh risk.

Figure 1.

Team composition of Quebec early intervention services and offered psychosocial interventions.

Discussion

Access, Treatment Delay, and Care Continuity

At the time of the survey, about 3.75 million people (less than half of Quebec’s population) lived in catchment areas served by EIS.64 To reduce the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) and traumatic pathways to care, 10 programs had an open referral policy and most accepted self-referrals and referrals from schools, family, and friends. Several programs specified maximum acceptable delays between referral and initial screening, assessment and entry to program. The average time between referral and intake varied greatly (3–90 days). To promote early case identification (community capacity to recognize early signs of psychosis and refer without undue delay), 8 programs engaged in public education, and 11 offered education to potential referral sources (e.g., schools). The reasonable delays between referral, assessments, and the beginning of treatment reported by 11 programs could be attributed to service reorganizations that bypassed traditional pathways to care. Although these efforts sought to reduce DUP, most programs did not specifically estimate DUP. Our results are similar to those of an Ontarian EIS survey.65

Some programs’ restrictive intake criteria may have excluded some patients who might have benefited from EI. To ensure continuity of care, EIS should serve people from adolescence past the age of majority (18 years in Quebec) instead of having hard age-based cut-offs. Several surveyed adult programs admitted patients under 18, but child and adolescent programs did not continue follow-up once patients turned 18.

High-Quality Interventions

Similar to the Ontario survey’s results,65 most Quebec programs offered various evidence-based services, namely, pharmacotherapy, patient and family psychoeducation, cognitive-behavior therapy, and substance misuse interventions.

Four of the 15 programs did not offer intensive case management and one offered it only to patients considered difficult to engage. Furthermore, as in the Ontario study,66 most programs did not adhere to recommended low patient-to-case manager ratios. This could lead to staff burnout65,67 and impede the provision of services of appropriate intensity. Given that case management is a pillar of EI,58,59 lack of selective and inadequately resourced case management is disconcerting.

High-Fidelity Implementation

Quebec’s EIS struggle with integrating administrative or organizational elements that could improve the implementation of standards and guidelines, likely due to their widely reported lack of adequate administrative, financial, and political support. Few programs had formal protocols for patient assessment, outcomes monitoring, and quality assurance. Such heterogeneity has been observed in implementing other high-intensity mental health programs on large scales.68

To address the lack of continuing education opportunities especially in French, that most programs reported, AQPPEP organizes conferences and mentoring on-site and online. These are often the main or only continuing education opportunities available.

Contextual Influences

Unlike academic programs with dense urban catchment populations (range: 125,000–600,000; median: 370,000), non-academic programs face challenges attributable to the vastness (up to 10 times larger) and sparse populations of their catchments (range: 77,000–200,000; median: 120,000). Their smaller, less professionally diverse teams often dedicate part of their time to non-EIS activities and offer fewer types of psychosocial interventions. Some remote programs offer outreach services so that patients need not travel long distances to receive care. They combine several types of group interventions to serve more patients simultaneously and hold groups (e.g., family psychoeducation) in collaboration with local community organizations (often not restricted to first-episode psychosis [FEP] patients). The scarcity of employment support personnel and adapted employment options could result in patients in rural programs having poorer social and functional recovery. To enhance EI service provision and training/supervision opportunities for remote areas, alternative service models like flexible assertive community treatment,69 specialist outreach70 or hub-and-spoke,70 and technological options should be considered. Training and supervising mental health-care providers, especially for interventions like cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for psychosis, remains challenging for all EIS.70

It is known that fidelity to service models is attainable rapidly after implementation.71,72 We found that how long programs had been in operation had little bearing on their fidelity to core EI components. British Columbia and Ontario, where provincial EIS standards exist,3,19 have reported heterogeneous implementation and called for close and continuous monitoring.65,73 Fidelity scales have been proposed and used in program audits to facilitate homogenization and adherence to standards among EIS.29,60,74,75 Dedicated resources to support programs in continuous quality improvement (like the implementation advisor appointed by CNESM in 2017) may also help improve and evaluate fidelity.

Our findings also highlight the need to support EIS programs as they are being created in Quebec to ensure their alignment with standards and their collection of data on key performance indicators71 from the outset.

Limitations

Data collected through a survey completed by program directors is subject to desirability bias. Although the data were 90% complete, two small programs did not complete most of the survey. EIS engaging in research activities may have been able to provide more accurate data-informed answers than non-academic programs. How programs were evaluated by patients and their families was not addressed.

Although most services reported offering many psychosocial interventions, the survey did not query what proportion of patients received them. We also did not enquire whether clinicians offering specialized interventions were properly trained and supervised.

Conclusion

Quebec EIS offer quality services to persons with FEP and adhere to several of the model’s essential components, despite lacking dedicated funding and policy support until recently. There is some heterogeneity in programs’ clinical and administrative components. Similar to studies of EI implementation, we found that smaller (rural) programs offered several essential components in adherence to standards, despite having a limited number of clinicians.65 Some of the variance in services offered may be attributed to specific clinical or geographical realities. Most programs reported difficulties in implementing some essential components, even though clinical guidelines are widely available to clinicians and administrators.

Our survey represents an initial step in the monitoring of EIS implementation prior to the establishment of provincial guidelines and wider funding commitments. The survey allowed us to evaluate programs’ perceptions of their own performance. The next step would be to use scales to measure the quality of services and their fidelity to the EI model, as was recently done in Ontario66 and in other countries.76,77 Comparing the results of this survey with scale-based assessments in the future will help develop interventions to improve the quality of care and enhance programs’ and clinicians’ awareness of their strengths and weaknesses.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Bastian Bertulies-Esposito  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7285-0181

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7285-0181

References

- 1. Cocchi A, Cavicchini A, Collavo M, et al. , Implementation and development of early intervention in psychosis services in Italy: A national survey promoted by the Associazione italiana interventi precoci nelle psicosi. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2018;12(1):37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Catts SV, Evans RW, O’Toole BI, et al. Is a national framework for implementing early psychosis services necessary? results of a survey of Australian mental health service directors. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2010;4(1):25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ehmann T, Hanson L, Yager J, et al. Standards and guidelines for early psychosis intervention (EPI) programs. Victoria: British Columbia Ministry of Health Services; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nolin M, Malla A, Tibbo P, et al. Early intervention for psychosis in Canada: what is the state of affairs? Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(3):186–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Csillag C, Nordentoft M, Mizuno M, et al. Early intervention services in psychosis: from evidence to wide implementation. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2016;10(6):540–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Csillag C, Nordentoft M, Mizuno M, et al. Early intervention in psychosis: from clinical intervention to health system implementation. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2018;12(4):757–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ministère de la santé et des services sociaux, Plan d’action en santé mentale 2015-2020. Québec, Canada: Gouvernement du Québec; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8. La Presse Canadienne. Québec investit 26,5 millions en santé mentale. Le Devoir, April 29, 2017 Available from https://www.ledevoir.com/societe/sante/497541/quebec-investit-26-5-millions-en-sante-mentale [accessed 2017 Jun 15].

- 9. Ministère de la santé et des services sociaux. Cadre de référence: programmes d’interventions pour premiers épisodes psychotiques (PIPEP). Québec, Canada: Gouvernement du Québec; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Centre national d’excellence en santé mentale. Proposition de guide à l’implantation dses équipes de premier épisode psychotique. Montréal, Canada: Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11. NIMHE National Early Intervention Programme. Early intervention (ei) acceptance criteria guidance. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Psychosis and schizophrenia in children and young people: the NICE guideline on recognition and management. Leicester, UK: The British Psychological Society and the Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Initiative to Reduce the Impact of Schizophrenia. IRIS guidelines update September 2012. IRIS Initiative Ltd; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Early Intervention in Psychosis Network (EIPN). Standards for early intervention in psychosis services. London, UK: Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Early Psychosis Guidelines Writing Group and EPPIC National Support Program. Australian clinical guidelines for early psychosis Orygen: The National Centre of Excellence; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Disley B. Early intervention in psychosis guidance note. Wellington, New Zealand: Mental Health Commission; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 17. The Italian national guidelines system (SNLG). Early intervention in schizophrenia—Guidelines. Milan, Italy: The Italian National Guidelines System; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Program policy framework for early intervention in psychosis. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Early psychosis intervention program standards. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Early Psychosis Services N.B., Administrative guidelines. Addiction, Mental Health and Primary Health Care Services Fredericton, New Brunswick: Addiction, Mental Health and Primary Health Care Services; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nova Scotia Department of Health. Nova Scotia provincial service standards for early psychosis. Halifax, Nova Scotia; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nova Scotia Department of Health. Standards for mental health services in Nova Scotia. Halifax, Nova Scotia; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Addington DE, McKenzie E, Norman R, et al. Essential evidence-based components of first-episode psychosis services. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(5):452–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Arendt M, PB M, Rosenberg R, et al. Familial predisposition for psychiatric disorder: comparison of subjects treated for cannabis-induced psychosis and schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(11):1269–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Niemi-Pynttäri JA, Sund R, Putkonen H, et al. Substance-induced psychoses converting into schizophrenia: a register-based study of 18,478 Finnish inpatient cases. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(1):e94–e99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Implementing the early intervention in psychosis access and waiting time standard. Guidance; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hughes F, Stavely H, Simpson R, et al. At the heart of an early psychosis centre: the core components of the 2014 early psychosis prevention and intervention centre model for Australian communities. Australas Psychiatry. 2014;22(3):228–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Larsen TK, Joa I, Langeveld J, et al. , Optimizing health-care systems to promote early detection of psychosis. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2009;3(Suppl 1):S13–S16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Melton R, Blea P, Hayden-Lewis KA, et al. Practice guidelines for Oregon early assessment and support alliance (EASA). 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Turner M, Nightingale S, Mulder R, et al. Evaluation of early intervention for psychosis services in New Zealand: What works? Auckland: Health Research Council of New Zealand; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Harris MG, Henry LP, Harrigan SM, et al. The relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome: an eight-year prospective study. Schizophr Res. 2005;79(1):85–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Marshall M, Lewis S, Lockwood A, et al. Association between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in cohorts of first-episode patient: a systematic review. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(9):975–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Norman RMG, Malla AK, Duration of untreated psychosis: a critical examination of the concept and its importance. Psychol Med. 2001;31(3):381–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Perkins DO, Gu H, Boteva K, et al. Relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: a critical review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(10):1785–1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Berry K, Ford S, Jellicoe-Jones L, et al. PTSD symptoms associated with the experiences of psychosis and hospitalisation: a review of the literature. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33(4):526–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Insel TR. Raise-ing our expectations for first-episode psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(4):311–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. MacDonald K, Fainman-Adelman N, Anderson KK, et al. Pathways to mental health services for young people: a systematic review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2018;53(10):1005–1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. McGorry PD. Posttraumatic stress disorder following recent-onset psychosis. an unrecognized postpsychotic syndrome. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1991;179(5):253–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tarrier N, Khan S, Cater J, et al. , The subjective consequences of suffering a first episode psychosis: trauma and suicide behaviour. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42(1):29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Doyle R, Turner N, Fanning F, et al. , First-episode psychosis and disengagement from treatment: a systematic review. Psych Serv. 2014;65(5):603–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bertolote J, McGorry P. Early intervention and recovery for young people with early psychosis: consensus statement. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187(Suppl. 48):s116–s119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Marshall M, Rathbone J. Early intervention for psychosis. Cochr Database Syst Rev. 2011;(6): 171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. McGorry PD, Yung AR, Phillips LJ, et al. Randomized controlled trial of interventions designed to reduce the risk of progression to first-episode psychosis in a clinical sample with subthreshold symptoms. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(10):921–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Fusar-Poli P, Borgwardt S, Bechdolf A, et al. The psychosis high-risk state: a comprehensive state-of-the-art review. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(1):107–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fusar-Poli P, Diaz-Caneja CM, Patel R, et al. Services for people at high risk improve outcomes in patients with first episode psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;133(1):76–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. McGlashan TH, Zipursky RB, Perkins D, et al. Randomized, double-blind trial of olanzapine versus placebo in patients prodromally symptomatic for psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(5):790–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Morrison AP, French P, Walford L, et al. Cognitive therapy for the prevention of psychosis in people at ultra-high risk: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185(4):291–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nordentoft M, Thorup A, Petersen L, et al. Transition rates from schizotypal disorder to psychotic disorder for first-contact patients included in the OPUS trial. a randomized clinical trial of integrated treatment and standard treatment. Schizophr Res. 2006;83(1):29–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. van der Gaag M, Smit F, Bechdolf A, et al. Preventing a first episode of psychosis: meta-analysis of randomized controlled prevention trials of 12 month and longer-term follow-ups. Schizophr Res. 2013;149(1-3):56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cotter J, Drake RJ, Bucci S, et al. What drives poor functioning in the at-risk mental state? a systematic review. Schizophr Res. 2014;159(2-3):267–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hui C, Morcillo C, Russo DA, et al. Psychiatric morbidity, functioning and quality of life in young people at clinical high risk for psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2013;148(1-3):175–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Simon AE, Gradel M, Cattapan-Ludewig K, et al. Cognitive functioning in at-risk mental states for psychosis and 2-year clinical outcome. Schizophr Res. 2012;142(1-3):108–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bertelsen M, Jeppesen P, Petersen L, et al. Five-year follow-up of a randomized multicenter trial of intensive early intervention vs standard treatment for patients with a first episode of psychotic illness: the OPUS trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(7):762–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Craig TK, Garety P, Power P, et al. The Lambeth early onset (LEO) team: randomised controlled trial of the effectiveness of specialised care for early psychosis. BMJ. 2004;329(1067):1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Melau M. OPUS fidelity rapport 2016. København, Denmark: Psykiatrisk Center København; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Petersen L, Jeppesen P, Thorup A, et al. A randomised multicentre trial of integrated versus standard treatment for patients with a first episode of psychotic illness. BMJ. 2005;331(602):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Petersen L, Thorup A, Øqhlenschlæger J, et al. Predictors of remission and recovery in a first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorder sample: 2-year follow-up of the OPUS trial. Can J Psychiatry. 2008;53(10):660–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Fowler D, Hodgekins J, Howells L, et al. Can targeted early intervention improve functional recovery in psychosis? a historical control evaluation of the effectiveness of different models of early intervention service provision in Norfolk 1998-2007. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2009;3(4):282–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Dieterich M, Irving CB, Bergman H, et al. , Intensive case management for severe mental illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;1:1–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Addington DE, Norman R, Bond GR, et al. , Development and testing of the first-episode psychosis services fidelity scale. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(9):1023–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Gold PB, Meisler N, Santos AB, et al. , The program of assertive community treatment: implementation and dissemination of an evidence-based model of community-based care for persons with severe and persistent mental illness. Cogn Behav Prac. 2003;10(4):290–303. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Nordentoft M, Rasmussen JØ, Melau M, et al. How successful are first episode programs? a review of the evidence for specialized assertive early intervention. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2014;27(3):167–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Iyer S, Jordan G, Macdonald K, et al. Early intervention for psychosis: a Canadian perspective. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2015;203(5):356–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Statistics Canada. Quebec [province] and Canada [country] (table). Census Profile, 2016 Available from http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm? [accessed 2018 Jan 1]

- 65. Durbin J, Selick A, Hierlihy D, et al. A first step in system improvement: a survey of early psychosis intervention programmes in Ontario. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2016;10(6):485–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Durbin J, Selick A, Langill G, et al. , Using fidelity measurement to assess quality of early psychosis intervention services in Ontario. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;70(9):840–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Woltmann EM, Whitley R, McHugo GJ, et al. The role of staff turnover in the implementation of evidence-based practices in mental health care. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(5):732–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Phillips SD, Burns BJ, Edgar ER, et al. Moving assertive community treatment into standard practice. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(6):771–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Drukker M, Sytema S, Driessen G, et al. Function assertive community treatment (FACT) and psychiatric service use in patients diagnosed with severe mental illness. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2011;20(3):273–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Cheng C, deRuiter WK, Howlett A, et al. Psychosis 101: evaluating a training programme for northern and remote youth mental health service providers. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2013;7(4):442–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Salyers MP, Godfrey JL, McGuire AB, et al. Implementing the illness management and recovery program for consumers with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(4):483–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. McHugo GJ, Drake RE, Whitley R, et al. Fidelity outcomes in the national implementing evidence-based practices project. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(10):1279–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Ehmann T. A quiet evolution: early psychosis services in British Columbia a survey of hospital and community resources 2003-2004. Richmond: British Columbia Schizophrenia Society; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 74. Hetrick SE, Bailey AP, Smith KE, et al. Integrated (one-stop shop) youth health care: best available evidence and future directions. Med J Aust. 2017;207(10):S5–S18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Melau M, Albert N, Nordentoft M, Development of a fidelity scale for Danish specialized early interventions service. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2017;13(3):568–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Melau M, Albert N, Nordentoft M, Programme fidelity of specialized early intervention in Denmark. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2019;13(3):627–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Mueser KT, Meyer-Kalos PS, Glynn SM, et al. Implementation and fidelity assessment of the navigate treatment program for first episode psychosis in a multi-site study. Schizophr Res. 2019;204:271–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]