Abstract

Objective:

Patients suffering from major depressive disorder (MDD) experience impaired functioning and reduced quality of life, including an elevated risk of episode return. MDD is associated with high societal burden due to increased healthcare utilization, productivity losses, and suicide-related costs, making the long-term management of this illness a priority. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT), a first-line preventative psychological treatment, compared to maintenance antidepressant medication (ADM), the current standard of care.

Method:

A cost–utility analysis was conducted over a 24-month time horizon to model differences between MBCT and ADM in cost and quality-adjusted life years (QALY). The analysis was conducted using a decision tree analytic model. Intervention efficacy, utility, and costing data estimates were derived from published sources and expert consultation.

Results:

MBCT was found to be cost-effective compared to maintenance ADM over a 24-month time horizon. Antidepressant pharmacotherapy resulted in 1.10 QALY and $17,255.37 per patient on average, whereas MBCT resulted in 1.18 QALY and $15,030.70 per patient on average. This resulted in a cost difference of $2,224.67 and a QALY difference of 0.08, in favor of MBCT. Multiple sensitivity analyses supported these findings.

Conclusions:

From both a societal and health system perspective, utilizing MBCT as a first-line relapse prevention treatment is potentially cost-effective in a Canadian setting. Future economic evaluations should consider combined treatment (e.g., ADM and psychotherapy) as a comparator and longer time horizons as the literature advances.

Keywords: mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, depression, relapse prevention, economic evaluation, cost-effectiveness, health economics

Abstract

Objectif:

Les patients souffrant de trouble dépressif majeur (TDM) éprouvent un fonctionnement déficient et une qualité de vie réduite, notamment un risque élevé de retour d’un épisode. Le TDM est associé à une charge sociétale élevée en raison d’une utilisation accrue des soins de santé, de pertes de productivité et de coûts liés au suicide, faisant ainsi une priorité de la prise en charge à long terme de cette maladie. Le but de la présente étude est d’évaluer la rentabilité de la thérapie cognitive basée sur la pleine conscience (TCPC), un traitement psychologique préventif de première intention, comparativement aux médicaments antidépresseurs (MAD) d’entretien, la norme actuelle en matière de soins.

Méthode:

Une analyse coût-utilité a été menée sur un échéancier de 24 mois afin de modéliser les différences de coût et d’années de vie pondérées par la qualité (QUALY) entre la TCPC et les MAD. L’analyse a été menée à l’aide d’un modèle analytique d’arbre décisionnel. L’efficacité de l’intervention, l’utilité et les estimations des données de coûts ont été tirées de sources publiées et de consultations avec des experts.

Résultats:

La thérapie cognitive basée sur la pleine conscience s’est révélée rentable comparativement aux médicaments antidépresseurs d’entretien sur une période de 24 mois. La pharmacothérapie antidépressive a eu un résultat de 1,10 QALY et 17 255,37 $ par patient en moyenne, alors que la TCPC produisait 1,18 QALY et 15 030,70 $ par patient en moyenne. Le résultat est donc une différence de coût de 2 224,67 $ et une différence de QALY de 0,08, en faveur de la TCPC. De multiples analyses de sensibilité ont appuyé ces résultats.

Conclusions:

Tant d’un point de vue sociétal que de l’angle du système de santé, utiliser la TCPC comme traitement de première intention pour prévenir la rechute est potentiellement rentable dans un contexte canadien. Les futures évaluations économiques devraient envisager un traitement combiné (p. ex., les MAD et la psychothérapie) comme comparateur et des échéanciers plus longs à mesure que progresse la littérature.

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a common condition characterized by frequent relapse and recurrence.1,2 MDD is characterized by the presence of more than one major depressive episode. A depressive episode is diagnosed when an individual presents 5 or more symptoms (i.e., depressed mood, diminished interest in any or all activities, weight loss/gain, feelings of fatigue, etc.) in the same 2-week period.3 In Canada, the lifetime prevalence of MDD is 11.7% and the annual prevalence is 4.8%, indicating that over 1.5 million Canadians experienced a depressive episode in the past year.4 MDD is associated with reduced quality of life5 and carries a high societal burden due to increased healthcare utilization, productivity losses, and suicide-related costs.6 On average, individuals with recurrent depression will have 5 to 9 separate depressive episodes in their lifetime,7,8 and for those with a history of 3 or more episodes, the time to recurrence is much faster and 50% to 70% experience another episode within 2 years.9–11 The increased risk of relapse faced by patients in remission or recovery has prompted a focus on prophylactic treatment.

Once in remission, patients with recurrent depression are recommended maintenance treatment for at least 2 years.12 While antidepressant medication (ADM) is the current standard of care, many people do not wish to stay on medication for indefinite periods, or cannot tolerate the side effects, leading to poor adherence rates.13 Nonadherence to antidepressants is associated with poor clinical outcomes such as increased risk of relapse, emergency department visits, and hospitalization rates.14 Thus, there is growing interest in psychotherapy alternatives to long-term antidepressant use as a means to prevent relapse. Many countries, including Canada, have adopted mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) as a first-line maintenance treatment, either in addition to antidepressants or as an alternative to antidepressants for patients who wish to stop taking medication15–18 but still require prophylaxis. MBCT is a structured group therapy program that consists of 8 weekly, 2-hr sessions delivered in a group of 8 to 15 participants, which integrates the practice of mindfulness meditation with the tools of cognitive therapy for depression. MBCT teaches patients how to disengage from habitual (“automatic”) dysfunctional cognitive routines such as depression-related ruminative thought patterns as a way to reduce vulnerability to relapse.19,20

More recently, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that have compared MBCT to maintenance ADM have found MBCT to generally perform on par with antidepressants for preventing relapse,21–24 and several meta-analyses have emerged showing MBCT is an efficacious intervention25–30 against other comparators. For example, one meta-analysis with 6 studies (N = 593) found that MBCT reduced the risk of relapse by 43% compared to treatment as usual for patients with 3 or more previous episodes.26

At present, the literature examining MBCT’s cost-effectiveness is scarce and inconsistent.31 Three economic evaluations were conducted alongside RCTs over time horizons ranging from 15 to 24 months.22,23,32 Kuyken et al.22 reported no significant cost difference between MBCT and maintenance ADM over a 15-month clinical follow-up. A subsequent study by the Kuyken et al.23 reported a nonsignificant cost difference between the MBCT group and ADM group using a larger sample size and 24-month follow up. The cost–utility analysis concluded that maintenance ADM (m-ADM) dominated MBCT such that MBCT was associated with higher costs and poorer quality-adjusted life years (QALY).23 In contrast, a study by Shawer et al.32 found MBCT + depression active relapse monitoring (DRAM) had a high probability of being cost-effective compared to DRAM alone. Overall, the health economic evidence for MBCT has examined multiple effect outcomes and the findings are inconclusive.29

To inform decision makers about resource allocation and costs associated with MBCT, this study presents a cost–utility analysis of MBCT compared to ADM in the adult population over a 24-month time horizon. To our best knowledge, this is the first economic evaluation to compare the cost-effectiveness of MBCT to ADM in a Canadian setting.

Methods

The study conducted a model-based cost–utility analysis. The primary outcome is a generic measure for health gain called quality-adjusted life years (QALY). Measuring outcomes in QALYs allows for decision makers to make comparisons across interventions for different conditions. We adopted a societal perspective and applied a 1.5% discount rate in accordance with Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health guidelines.33 The study adopted a 24-month time horizon, based on the existing literature on model-based economic evaluations conducted for depression treatments.34 A literature review was undertaken to obtain efficacy, utility, and costing data. Parameter inputs were based on the best available evidence. Values from published sources were supplemented with expert consultation.

Target Population and Comparators

The target population is adults aged 18 to 65 who had experienced at least 2 past episodes of MDD and are currently in remission. Individuals with comorbid conditions such as bipolar disorder, substance abuse disorder, and psychotic disorder were excluded. Canadian clinical guidelines recommends MBCT, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and ADM as first-line interventions for the prevention of depression relapse.15,16 However, the majority of RCTs have studied the efficacy of MBCT in comparison to ADM. Only one study was found to compare MBCT to CBT,35 thus, due to the absence of evidence, we could not include CBT as a comparator. For the purposes of this study, MBCT is defined as a structured 8-week group psychotherapy program,17 and ADM is defined as maintenance antidepressant pharmacotherapy, specifically receiving venlafaxine at 375 mg/day for the entirety of the 24-month time horizon.

Model Structure and Assumptions

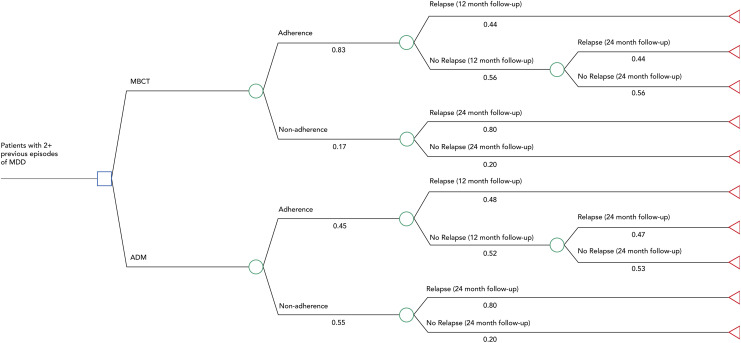

A decision tree was developed using Treeage Pro 2017 (Figure 1). The model assumes that patients with at least 2 prior episodes of MDD enter 1 of the 2 intervention arms (MBCT vs. ADM). The model incorporates adherence to treatment and relapse. We assumed that once an individual relapsed, they enter an MDD state and acquire the costs and utility of an acute MDD episode. We assume that individuals who are nonadherent, in either arm, do not benefit from the treatment (state of “no treatment”). Within either intervention arm, individuals who are nonadherent to the treatment are assumed to acquire the costs of relapsing and health utility of the relapsed state over the entirety of the time horizon (i.e., health costs over 24 months, productivity costs over 24 months). Similarly, nonadherent individuals who enter the nonrelapse state are assumed to acquire the costs and health utility of not relapsing.

Figure 1.

Decision tree model.

Those who adhere to the treatment are observed at a 12- and 24-month time period. Individuals who relapse at 12 months are assumed to remain in that state for the entirety of our time horizon, acquiring the costs and utility of a relapsed health state. Individuals who do not relapse at 12 months and relapse at 24 months are assumed to acquire costs associated with relapse for the last year and a QALY of (nonrelapse state utility × 1 + relapse state utility × 1) to account for the change in health state. We assumed that once individuals relapsed, they acquired the cost of an MDD episode and were assigned the same healthcare and productivity costs, regardless of intervention group.

Health State Utilities

Health utility is described as an individual’s preference for particular health outcomes. The valuations typically fall between 0 (death) and 1 (optimal health). We quantified health effects by using QALYs which were calculated by multiplying the utility of a particular health state by the amount of time spent in that health state. We adopted utility values from three different sources (Table 1). The utility of relapse and nonrelapse post-MBCT intervention was obtained from Koeser et al.,38 which converted quality of life outputs into EQ-5D scores. Utilities of relapse and nonrelapse post-pharmacotherapy were generated in the study of Sapin et al.37 by using a generic measure, EQ-5D, and translated using the time-trade-off approach. Utility for individuals who were nonadherent but experienced no relapse (i.e., remained in remission) was derived from Revicki and Wood,36 this source used the standard gamble method to measure health states.

Table 1.

Utility and Efficacy Parameters.

| Parameter | Value (SD) | Distribution | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Utilities | |||

| Remission, no maintenance treatment | 0.86 (0.16) | Beta | Revicki and Wood36 |

| Relapse, no maintenance treatment | 0.33 (0.25) | Beta | Sapin et al.37 |

| MBCT adherence, relapse into depressive episode | 0.48 (0.05) | Beta | Koeser et al.38 |

| ADM adherence, relapse into depressive episode | 0.58 (0.28) | Beta | Sapin et al.37 |

| MBCT adherence, no relapse | 0.80 (0.02) | Beta | Koeser et al.38 |

| ADM adherence, no relapse | 0.85 (0.13) | Beta | Sapin et al.37 |

| Probabilities | |||

| Adherence, MBCT | 0.83 (0.166) | Beta | Kuyken et al.23 |

| Adherence, ADM | 0.45 (0.09) | Beta | Composite of Klein et al.39, ten Doesschate et al.13, Sheehan et al.40, and Akincigil et al.41 |

| Relapse, 12 months, MBCT | 0.44 (0.11) | Beta | Piet and Houggard42 |

| Relapse, 12 months, ADM | 0.48 (0.12) | Beta | Piet and Houggard42 |

| Relapse, 24 months, MBCT | 0.44 (0.11) | Beta | Kuyken et al.23 |

| Relapse, 24 months, ADM | 0.47 (0.118) | Beta | Kuyken et al.23 |

| Relapse, nonadherence | 0.80 (0.2) | Beta | Frank et al.43 |

Note. Adherence SE based on assumption of ± 20% and relapse (MBCT, ADM) SE based on assumption of ± 25%. ADM = antidepressant medication; MBCT = mindfulness-based cognitive therapy.

Efficacy and Adherence

Efficacy and probability values were obtained from various sources (Table 1). MBCT has a growing evidence base with 9 high-quality RCTs; however, follow-up has generally not gone past 18 months.44 Relapse probability data at 12 months were obtained from Piet and Houggard42 meta-analysis (6 studies, N = 593). The meta-analysis used the Jadad criteria42 and found that the included studies generally had high methodological quality. The results are comparable to other meta-analyses in the literature. Relapse probabilities at 24 months were obtained from the only RCT that followed patients over 24 months—Kuyken et al.,23 which had a large sample (N = 424). Due to the lack of systematic adherence data in the literature, Kuyken et al.23 and expert consultation were used to estimate MBCT adherence. For MBCT, patients were considered to be adherent if they had attended at least 4 of the 8 group sessions. A composite measure was computed for adherence to ADM based on 4 relevant studies.13,39–41 Nonadherence to ADM is defined as missing doses or prematurely stopping medication altogether. Adherence was measured using prescription refill data or self-reported via the Medication Adherence Questionnaire.

Costs

All costs are per patient, reported in 2018 Canadian dollars, and used Canadian sources where possible (Table 2). Cost for MBCT was determined by consulting a multisite mindfulness center in Ontario. The center runs its programs with an MD facilitator, where the MD bills Ontario Healthcare Insurance Plan (OHIP) and the center charges an overhead cost (i.e., administration, materials, physical space, marketing) to the patient. We assumed that MDs billed OHIP for delivering group psychotherapy.48 Cost of ADM was guided by Segal et al.21 drug protocol for maintenance ADM, which prescribed venlafaxine as the maintenance ADM. This study was conducted in Ontario with Ontarian physicians—we assume that the study’s protocol reflects maintenance ADM prescription patterns in Canada. Maximum dosage of venlafaxine (375 mg/day) was assumed and calculated using the Ontario Drug Benefit (ODB) database. We applied an 8% markup fee and a $13.25 dispensing fee. To our knowledge, there is no standard for a commonly prescribed maintenance ADM, patients remain on their existing medication and continue taking it. In the literature, venlafaxine and escitalopram (comparable drug in terms cost and effect) are well represented in trials investigating the prevention of relapse of depression.49,50

Table 2.

Costing Data (per Year).

| Parameter | Value (Standard Error) | Distribution | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention costs | |||

| MBCT (physician group psychotherapy billing + patient out-of-pocket) | $922.25 ($230.50) | Gamma | OHIP codes K040 and K04; expert consultation |

| ADM (Venlafaxine, max. dosage 375 mg/day) | $379.8 ($94.95) | Gamma | ODB DIN 02452839 and ODB DIN 02452847 |

| Direct health-care costs for relapse (outpatient visits, ER visits, hospitalization costs) | $3,404.56 ($2,357.59 to $3,964.66) | Gamma | Chiu et al.45 |

| Direct health-care costs for no relapse (physician follow-up visits) | $125.50 ($31.38) | Gamma | OHIP code K005; Health Quality Ontario46 |

| Productivity costs | $8,202.68 ($2,050.67) | Gamma | Evans-Lacko and Knapp47 |

Note. Standard error based on an assumption that the mean costs vary by ± 25%.

ER = Emergency room; ODB = Ontario Drug Benefit Program; OHIP = Ontario Health Insurance Plan Schedule of Benefits and Fees.

Direct healthcare costs include outpatient visits, emergency department visits, and hospitalization costs. These healthcare costs were retrieved from Chiu et al.’s45 retrospective cohort study conducted in Ontario. A cohort of 409 individuals with MDD was followed for 5 years to determine the average healthcare costs associated with their depression. Costs were in USD 2013 dollars, which were inflated and converted to 2018 CAD dollars. We assumed that those in the nonrelapse state had 2 annual follow-up visits with a general physician as suggested by Health Quality Ontario.46 Productivity costs associated with absenteeism and presenteeism were obtained from a large cross-national survey study.47 Evans-Lacko and Knapp47 sampled employed individuals with self-reported depression across 8 countries, gathering a sample size of 1,000 survey respondents from Canada. Respondents reported their salaries and completed the Work Performance Questionnaire. Total productivity costs were calculated using the human capital approach. Costs were reported in 2014 USD dollars, which were inflated and converted to 2018 CAD dollars.

Sensitivity Analyses

Three forms of sensitivity analyses were conducted: probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA), univariate sensitivity analyses, and two scenario analyses. We performed a PSA, Monte Carlo simulation with 10,000 iterations to assess parameter uncertainty at a $50,000 willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold. The probability distributions were calculated based on standard errors or a range reported in the literature. Univariate analyses were conducted to understand the key drivers of the model’s results (Table 3). Since adherence data in the base case analysis were derived from RCTs, which may not adequately reflect adherence rates in real-world settings, a scenario analysis was conducted to test this parameter. We assumed that both treatments would be equally preferred and therefore equally adhered to. Thereby, 2 scenarios were tested:

Table 3.

One-Way Sensitivity Analysis Parameters.

| Assumptions | Base Case | Modified Value |

|---|---|---|

| Cost of MBCT | $922.25 | $691.50 to $1152.50 |

| Cost of ADM for 24 months, Venlafaxine | $759.60 | $569.70 to $949.50 |

| Adherence ADM | 0.47 | 0.38 to 0.56 |

| Adherence MBCT | 0.83 | 0.664 to 0.996 |

| Probability of relapse, 12 months, MBCT | 0.44 | 0.33 to 0.55 |

| Probability of relapse, 12 months, ADM | 0.48 | 0.36 to 0.60 |

| Probability of relapse, nonadherence | 0.80 | 0.60 to 1.0 |

| Utility of MBCT adherence, relapse into depressive episode | 0.48 | 0.384 to 0.576 |

| Utility of ADM adherence, relapse into depressive episode | 0.58 | 0.464 to 0.696 |

Note. Costs SE based on assumption of ±25%; adherence and utility SE based on assumptions of ±20%; probability modified values based on the SD reported in the respective studies. ADM = antidepressant medication; MBCT = mindfulness-based cognitive therapy.

Healthcare perspective: Cost of MBCT includes OHIP billing for group therapy only, excluding productivity costs.

Adherence probabilities were the same for MBCT and ADM: 60%.

Results

The cost–utility of MBCT was assessed by the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). An ICER is calculated by dividing the difference in total costs (incremental costs) by the difference in a measure of health outcome or effect (incremental effect) between 2 interventions to provide a ratio of “extra cost per extra unit of health effect.”

Base Case Analysis

Over a 24-month time horizon, MBCT was found to be less costly and associated with a greater health gain than ADM. ADM resulted in $17,255.37 per patient on average and 1.10 QALYs, whereas MBCT resulted in $15,030.70 per patient on average and 1.18 QALYs. There was a cost difference of $2,224.67 and an incremental QALY gain of 0.08 in favor of MBCT. This suggests that MBCT is cost saving and results in greater health gain compared to ADM. The results may be considered cost-effective using the commonly reported threshold of $50,000/QALY.

Sensitivity Analysis

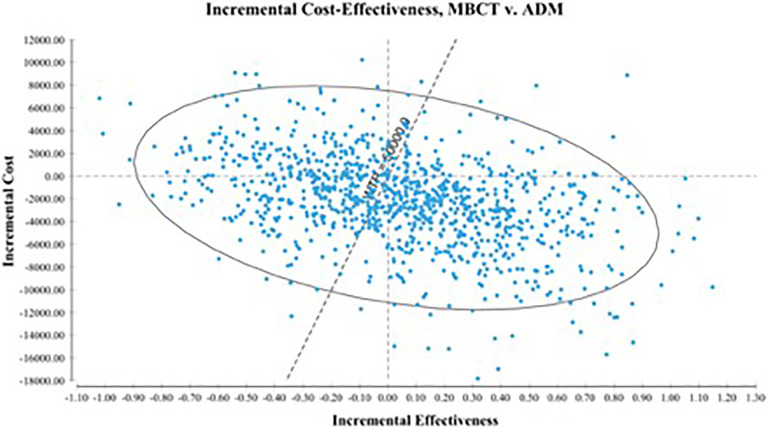

Figure 2 shows the results of the PSA in an incremental cost-effectiveness plane. The PSA demonstrated superiority in the southeast quadrant in which 44% of ICERs fell. The southeast quadrant refers to the intervention of interest (MBCT) being more effective and less costly than the comparator (ADM). Of the 26% of ICER iterations that landed in the southwest quadrant, 22% fall below the assigned WTP. The southwest quadrant describes a negative trade-off wherein the intervention of interest is less effective and less costly than the comparator. In total, 74% of iterations fell below the WTP threshold. The cost-effectiveness acceptability curve showed a high probability of MBCT being cost-effective at all levels of WTP ≥ $0; at the highest threshold level of $100,000, the probability of MBCT being cost-effective did not fall below 55%.

Figure 2.

Incremental cost-effectiveness scatter plot.

The univariate analyses found that the health utility of relapsing on ADM was the most sensitive parameter, followed by probability of adherence for both ADM and MBCT conditions. Nonetheless, at low and high values for all parameters, the ICER range remained negative, indicating that MBCT was cost-effective compared to ADM given parameter uncertainty. From a healthcare perspective, MBCT costs an average of $4,590.79 per patient for 1.18 QALYs while ADM costs $5,591.32 per patient for 1.10 QALYs. The incremental cost difference was $1,000.53 for 0.08 additional QALY gain over 24 months. This suggests that compared to ADM, MBCT has a cost savings of $1,000.53 and greater health outcomes. In the adherence scenario analysis (60% adherence for both conditions), MBCT was no longer dominant over ADM (ICER = $3,269.17/QALY). When adherence rates to both conditions were equal, MBCT was no longer cost-effective, affirming that adherence to treatment is a key factor in acquiring maximum health gain. In this case, MBCT and ADM were both comparable in cost and QALYs.

Discussion

The findings from this study suggest that adopting MBCT as a first-line relapse prevention treatment is potentially cost-effective in a Canadian setting for patients with a previous history of depression. To our knowledge, this is the first cost–utility analysis of MBCT and ADM using a decision tree analytic model utilized Canadian data on economic and healthcare costs.45 This study contributed to the literature gap on the need for economic evaluations of psychotherapy in the treatment of depression.31,34 Our overall findings are consistent with Shawyer et al.,32 regardless of the choice of comparator and outcome measure (disability-adjusted life years). This study’s findings are consistent with Kuyken et al.22 which found that MBCT had a high probability (>80%) of being cost-effective at WTP levels of ≥$10,000. This study found a lower probability of MBCT (>55%) being cost-effective at WTP levels ≥ $0. In their second replication study, Kuyken et al.23 found that MBCT was no longer cost-effective (higher costs and poorer health outcomes, on average, than maintenance antidepressant treatment). The inconsistency in findings may be attributed to differences in methodology (i.e., RCT vs. model-based cost-effectiveness analyses). Using a decision-analytic model allowed this study to integrate adherence to treatment as a key component within our model. It is well known that adherence to treatment is critical for successful relapse prevention, as is treatment preference.24 Preference for treatment varies depending on a myriad of factors including therapeutic relationships, side effects, affordability, and personal beliefs. By conducting a model-based analysis, we were able to incorporate this real-world consideration into our analysis. In fact, as per our scenario sensitivity analysis, when adherence rates were simulated to be the same, neither intervention dominated. This means both interventions were on par in terms of costs and QALYs when adherence to treatment was the same. Adherence data were sourced from clinical trials, validated through expert consultation, which do not always mirror the outcomes of patients receiving front-line treatment. Future economic evaluation studies should incorporate patient-level data to follow and account for adherence and preference.

Limitations

This study had a number of limitations. We relied on several costing assumptions, such as the assumption that individuals acquired the same healthcare and productivity costs regardless of their intervention. This may be an inaccurate representation of acquired costs in practical settings because different interventions may have variable impact on how individuals use healthcare services and engage in employment once they have relapsed. Our healthcare costs capture the average cost of an episode of MDD, regardless of a patient’s past history of depression. This would be an important consideration in our target population since cumulative burden costs on the healthcare system are not accounted for in our model. The cost for MBCT can differ based on who is delivering the intervention (i.e. general practitioner, psychiatrist, social worker) and the setting in which it is delivered (i.e. hospital, community setting, private practice). To the best of our knowledge, we incorporated the range of costs found from published sources within our sensitivity analysis. In our model, cost of MBCT was not found to be an important driver. Additionally, individual characteristics and medical history influence risk of relapse.51–54 In this respect, our study did not account for the population’s heterogeneity.

This study excluded combination therapy (MBCT in addition to maintenance antidepressants) as a relevant comparator. Combination therapy is typical in practice for patients at greater risk of relapse, especially for individuals with a history of depression. Two efficacy studies on combination MBCT and ADM were recently published.55,56 Similarly, combination CBT and ADM is an emerging area of research for relapse prevention.57 Due to the lack of health utility measures for patients who undertake combination therapy, combination therapy was not included in this study. Further research on efficacy and health utility measures for combination therapy will allow for a cost–utility analysis that encompasses the range of treatment options available for the target population. Additionally, due to the recurrent nature of depression for patients in this population, access to data that depict the cumulative costs of experiencing an MDD episode will allow for more comprehensive understanding of the burden of costs associated with MDD. In order to capture patient heterogeneity (history of depression, comorbidity, etc.),58,59 future research should consider conducting patient-level simulations which allow for individual patient histories to be recorded. A limitation within our study’s model may be the extent of our chosen time horizon (i.e., 24 months). In a systematic review of economic evaluations on depression treatments, 51% of included studies used decision trees with time horizons ranging from 6 weeks to 27 months.34 Decision trees are typically simpler to build with lower data requirements and consider a smaller number of health states. This study utilized a decision tree and thus, shorter time horizon, due to the focus on a specific segment of the population with major depression (patients in maintenance phase with 2+ previous episodes), where the risk of relapse is much higher (i.e., fewer number of possible health states).43 However, there are advantages with modelling longer time horizons due to the recurrent nature of the disease and one possibility would be to utilize a cohort-based state-transition Markov model which allows for extended time horizons up to a lifetime.

Conclusions

The long-term management of MDD recognizes the need for interventions that reduce acute symptom severity and prevent episode relapse or recurrence. The findings of this study suggest that MBCT is a potentially cost-effective intervention for relapse prophylaxis as compared to ADM and warrants greater dissemination.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the continuous support and guidance offered by Brian Chan, PhD, affiliate scientist at the University Health Network in Toronto, Canada.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Dr. Segal receives royalties from books and training workshops related to Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy. Tina Pahlevan and Christine Ung declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Tina Pahlevan, MPH  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7889-8293

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7889-8293

References

- 1. Judd LL. The clinical course of unipolar major depressive disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54(11):989–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bockting CL, Hollon SD, Jarrett RB, Kuyken W, Dobson K. A lifetime approach to major depressive disorder: the contributions of psychological interventions in preventing relapse and recurrence. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;4116–4126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. BMC Med. 2013;17:133–137. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Patten SB, Williams JVA, Lavorato DH, Wang JL, McDonald K, Bulloch AG. Descriptive epidemiology of major depressive disorder in Canada in 2012. Can J Psychiatry. 2015;60(1):23–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ishak WW, Greenberg JM, Cohen RM. Predicting relapse in major depressive disorder using patient-reported outcomes of depressive symptom severity, functioning, and quality of life in the individual burden of illness index for depression (IBI-D). J Affect Disord. 2013;151(1):59–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ferrari AJ, Charlson FJ, Norman RE, et al. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS Med. 2013;10(11):e1001547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kessler E, Walters RC. Epidemiology of DSM-III-R major depression and minor depression among adolescents and young adults in the national comorbidity survey. Depress Anxiety. 1998;7(1):3–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kessler RC, Zhao S, Blazer DG, Swartz M. Prevalence, correlates, and course of minor depression and major depression in the national comorbidity survey. J Affect Disord. 1997;45(1-2):19–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kupfer DJ, Frank E, Perel JM, et al. Five-year outcome for maintenance therapies in recurrent depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49(10):769–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Boland RJ, Keller MB. Course and outcome of depression. In: Gotlib IH, Hammen CL, editors. Handbook of depression 2nd ed New York (NY): Guilford Press; 2002. p. 223–243. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Keller MB, Boland RJ. Implications of failing to achieve successful long-term maintenance treatment of recurrent unipolar major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44(5):348–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sim K, Lau WK, Sim J, Sum MY, Baldessarini RJ. Prevention of relapse and recurrence in adults with major depressive disorder: systematic review and meta-analyses of controlled trials. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;19(2): pyv076 doi:10.1093/ijnp/pyv076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ten Doesschate MC, Bockting CLH, Schene AH. Adherence to continuation and maintenance antidepressant use in recurrent depression. J Affect Disord. 2009;115(1-2):167–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ho SC, Chong HY, Chaiyakunapruk N, Tangiisuran B, Jacob SA. Clinical and economic impact of non-adherence to antidepressants in major depressive disorder: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2016;1931–1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Parikh SV, Quilty LC, Ravitz P, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2016 clinical guidelines for the management of adults with major depressive disorder: section 2. Psychological treatments. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(9):524–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kennedy SH, Lam RW, McIntyre RS, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2016 clinical guidelines for the management of adults with major depressive disorder: section 3. Pharmacological treatments. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(9):540–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. American Psychiatric Association. Treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. Washington (DC): APA; 2010. p. 152 [Accessed October 10, 2018] https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Clinical guideline: depression in adults: recognition and management. London: NICE; 2019. p. 53 [Accessed October 2, 2018] https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Segal ZV, Williams JMG, Teasdale JD. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: a new approach to preventing relapse. New York (NY): Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 20. van der Velden AM, Kuyken W, Wattar U, et al. A systematic review of mechanisms of change in mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in the treatment of recurrent major depressive disorder. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;3726–3739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Segal ZV, Bieling P, Young T, et al. Antidepressant monotherapy vs sequential pharmacotherapy and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, or placebo, for relapse prophylaxis in recurrent depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2010;67(12):1256–1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kuyken W, Byford S, Taylor RS, et al. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy to prevent relapse in recurrent depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76(6):966–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kuyken W, Hayes R, Barrett B, et al. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy compared with maintenance antidepressant treatment in the prevention of depressive relapse/recurrence: results of a randomised controlled trial (the PREVENT study). Health Technol Assess. 2015;19(73):1–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Huijbers MJ, Spinhoven P, van Schaik DJF, Nolen WA, Speckens AE. Patients with a preference for medication do equally well in mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for recurrent depression as those preferring mindfulness. J Affect Disord. 2016;19532–19539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhang Z, Zhang L, Zhang G, Jin J, Zheng Z. The effect of CBT and its modifications for relapse prevention in major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kuyken W, Warren FC, Taylor RS, et al. Efficacy of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in prevention of depressive relapse: an individual patient data meta-analysis from randomized trials. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(6):565–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Clarke K, Mayo-Wilson E, Kenny J, Pilling S. Can non-pharmacological interventions prevent relapse in adults who have recovered from depression? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials . Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;3958–3970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Galante J, Iribarren SJ, Pearce PF. Effects of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy on mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Res Nurs. 2013;18(2):133–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Klainin-Yobas P, Cho MAA, Creedy D. Efficacy of mindfulness-based interventions on depressive symptoms among people with mental disorders: a meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(1):109–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chiesa A, Serretti A. Mindfulness based cognitive therapy for psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2011;187(3):44–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Feliu-Soler A, Cebolla A, McCracken LM, et al. Economic impact of third-wave cognitive behavioral therapies: a systematic review and quality assessment of economic evaluations in randomized controlled trials. Behav Ther. 2018;49(1):124–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shawyer F, Enticott JC, Özmen M, Inder B, Meadows GN. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for recurrent major depression: a “best buy” for health care? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2016;50(10):1001–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. Guidelines for the economic evaluation of health technologies: Canada. 4th ed Ottawa (ON): CADTH; 2017. p. 76 [Accessed October 14, 2018] https://www.cadth.ca/sites/default/files/pdf/guidelines_for_the_economic_evaluation_of_health_technologies_canada_4th_ed.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kolovos S, Bosmans JE, Riper H, Chevreul K, Coupé VMH, van Tulder MW. Model-based economic evaluation of treatments for depression: a systematic literature review. Pharmacoecon Open. 2017;1(3):149–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Manicavasgar V, Parker G, Perich T. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy vs cognitive behaviour therapy as a treatment for non-melancholic depression. J Affect Disord. 2011;130(1-2):138–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Revicki DA, Wood M. Patient-assigned health state utilities for depression-related outcomes: differences by depression severity and antidepressant medications. J Affect Disord. 1998;48(1):25–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sapin C, Fantino B, Nowicki ML, Kind P. Usefulness of EQ-5D in assessing health status in primary care patients with major depressive disorder. Health Qual Life Outcom. 2004;220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Koeser L, Donisi V, Goldberg DP, McCrone P. Modelling the cost-effectiveness of pharmacotherapy compared with cognitive-behavioural therapy and combination therapy for the treatment of moderate to severe depression in the UK. Psychol Med. 2015;45(14):3019–3031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Klein NS, van Rijsbergen GD, Ten Doesschate MC, Hollon SD, Burger H, Bockting CL. Beliefs about the causes of depression and recovery and their impact on adherence, dosage, and successful tapering of antidepressants. Depress Anxiety. 2017;34(3):227–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sheehan DV, Keene MS, Eaddy M, Krulewicz S, Kraus JE, Carpenter DJ. Differences in medication adherence and healthcare resource utilization patterns. CNS Drugs. 2008;22(11):963–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Akincigil A, Bowblis JR, Levin C, Walkup JT, Jan S, Crystal S. Adherence to antidepressant treatment among privately insured patients diagnosed with depression. Med Care. 2007;45(4):363–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17(1):1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Perel JM, et al. Three-year outcomes for maintenance therapies in recurrent depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47(12):1093–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Shapero BG, Greenberg J, Pedrelli P, et al. Mindfulness-based interventions in psychiatry. FOC. 2018;16(1):32–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chiu M, Lebenbaum M, Cheng J, de Oliveira C, Kurdyak P. The direct healthcare costs associated with psychological distress and major depression: a population-based cohort study in Ontario, Canada . PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0184268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Health Quality Ontario. Psychotherapy for major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder: a health technology assessment. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser [Internet]. 2017;17(15):1–167. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Evans-Lacko S, Knapp M. Global patterns of workplace productivity for people with depression: absenteeism and presenteeism costs across eight diverse countries. Soc Psychiatry Epidemiol. 2016;51(11):1525–1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kurdyak P, Newman A, Segal Z. Impact of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy on health care utilization: a population-based controlled comparison. J Psychosom Res. 2014;77(2):85–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bauer M, Tharmanathan P, Volz HP, Moeller HJ, Freemantle N. The effect of venlafaxine compared with other antidepressants and placebo in the treatment of major depression: a meta-analysis. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;259(3):172–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Garnock-Jones KP, McCormack PL. Escitalopram: a review of its use in the management of major depressive disorder in adults. CNS Drugs. 2010;24(9):769–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mocking RJT, Figueroa CA, Rive MM, et al. Vulnerability for new episodes in recurrent major depressive disorder: protocol for the longitudinal DELTA-neuroimaging cohort study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(3):e009510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Buckman JEJ, Underwood A, Clarke K, et al. Risk factors for relapse and recurrence of depression in adults and how they operate: A four-phase systematic review and meta-synthesis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;6413–6438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Burcusa SL, Iacono WG. Risk for recurrence in depression. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27(8):959–985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bockting CLH, Spinhoven P, Koeter MWJ, et al. Differential predictors of response to preventive cognitive therapy in recurrent depression: a 2-year prospective study. Psychother Psychosom. 2006;75(4):229–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Huijbers MJ, Spinhoven P, Spijker J, et al. Adding mindfulness-based cognitive therapy to maintenance antidepressant medication for prevention of relapse/recurrence in major depressive disorder: randomised controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2015;18754–18761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Huijbers MJ, Spinhoven P, Spijker J, et al. Discontinuation of antidepressant medication after mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for recurrent depression: randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;208(4):366–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bockting CLH, Klein NS, Elgersma HJ, et al. Effectiveness of preventive cognitive therapy while tapering antidepressants versus maintenance antidepressant treatment versus their combination in prevention of depressive relapse or recurrence (DRD study): a three-group, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psych. 2018;5(5):401–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Musliner KL, Munk-Olsen T, Eaton WW, Zandi PP. Heterogeneity in long-term trajectories of depressive symptoms: patterns, predictors and outcomes. J Affect Disord. 2016;192:199–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Steinert C, Hofmann M, Kruse J, Leichsenring F. The prospective long-term course of adult depression in general practice and the community. a systematic literature review. J Affect Disord. 2014;152-154:65–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]