Abstract

Objective

It has been shown that angiogenesis is a desirable treatment for patients with ischemic heart disease. We set out to investigate the impact of high-intensity interval training (HIIT) and berberine supplementation on the gene expression of angiogenesis-related factors and caspase-3 protein in rats suffering from myocardial ischemic-reperfusion injury.

Methods

Fifty rats were divided into the following groups: (1) trained, (2) berberine supplemented, (3) combined, and (4) IR. Each cohort underwent five sessions of HIIT per week for a duration of 8 weeks followed by induction of ischemia. Seven days after completion of reperfusion, changes in the gene expression of angiogenesis-related factors and caspase-3 protein were evaluated in the heart tissue.

Results

We observed a significant difference between four groups in the transcript levels of vascular endothelial cell growth factor (VEGF), fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF2), and thrombospondin-1(TSP-1) (p ≤ 0.05). However, the difference in endostatin (ENDO) levels was not significant among the groups despite a discernible reduction (p ≥ 0.05). Moreover, caspase-3 protein and infarct size were significantly reduced in the intervention groups (p ≤ 0.05), and cardiac function increased in response to these interventions.

Conclusion

The treatments exert their effect, likely, by reducing caspase-3 protein and increasing the expression of angiogenesis-promoting factors, concomitant with a reduction in inhibitors of the process.

1. Introduction

Previous works have shown that the reperfusion of blood in ischemic heart tissue is an effective method to treat acute myocardial infarction. However, reperfusion-induced oxidative stress can be detrimental and cause pathologic process of myocardial ischemia-reperfusion (IR) injury. Furthermore, ischemia-reperfusion injury is associated with microvascular dysfunction [1, 2], necessitating appropriate countermeasures to mitigate IR injury [3].

Angiogenesis, the formation of new blood vessels from preexisting ones, is indispensable for revascularization and cardiac remodeling following myocardial ischemia [4, 5]. Rehabilitation of the myocardium ischemic region involves the activation of several stimulatory and inhibitory modulators of angiogenesis; the most notable of which are vascular endothelial cell growth factor (VEGF), fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF2), endostatin (ENDO), and thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1) [6]. VEGF is one of the major regulators of angiogenesis, which performs its duties by stimulating the proliferation and differentiation of vascular endothelial cells, increasing the permeability and reducing the apoptosis of endothelial cells through activating nitric oxide (NO). FGF2 stimulates angiogenesis through positive regulation of VEGF and dilation via NO [7]. Among the angiogenesis inhibitor proteins, thrombospondins play a key role in the heart remodeling and TSP-1 is one of the main physiological inhibitors of angiogenesis [8]. ENDO, a 20 kDa fragment of the C-terminal of type XVIII collagen, is also an inhibitor of angiogenesis, hampering endothelial cell proliferation, VEGF-induced migration, and endothelial duct formation [9].

Also, past studies have shown that prevention of apoptosis in endothelial cells improves angiogenesis in patients suffering from ischemia [10]. The most important caspase in the apoptotic endpoint is caspase-3 [11].

It has emerged that exercise is an effective approach to enhance angiogenesis and reduce caspase-3 [12]. Although regular endurance exercise interventions are invariably important for the preconditioning of the heart tissue, high intensity interval training is suggested to be a more effective approach which is recommended for patients with coronary heart disease [3].

On the other hand, berberine is an alkaloid in the form of yellow needle-shaped crystals, found in plants such as Berberis vulgaris [13]. To date, several studies have demonstrated that berberine exerts antiarrhythmic, antiapoptotic, and anti-inflammatory effects, culminating in a decrease in caspase-3 and the size of infarcted myocardium [13–15].

Wu et al. conducted a study to delineate the effect of exercise on the alterations of gene expression in angiogenesis context. Their findings demonstrated that three days of exercise in rats prior to induction of myocardial infarction leads to a significant increase of VEGF levels [16]. In this work, we investigated the effect of HIIT and berberine as preconditioning factors, solely or in combination, on changes in the expression of angiogenesis-promoting and angiogenesis-inhibiting molecular components (VEGF, FGF2, TSP-1, and ENDO) and caspase-3 protein one week after IR.

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects

Fifty 8-12-week-old male Wistar rats with a mean weight of 240 ± 20 g were acquired from the Pasteur Institute of Iran (PII). All investigations were carried out in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and the study protocol was approved by the animal's ethics committee at Bu-Ali Sina University of Hamedan (code: IR.BASU.REC.1398.041). The animals were divided into five groups (10 rats each) and kept in the animal house of Razi Research Center of Lorestan in a temperature of 22 ± 2°C, humidity of 60 ± 5%, and a 12-12 light-dark cycle with free access to food and water.

2.2. Preparation of Berberine Extract

Barberry roots were collected from wild specimens gathered from the city of South Khorasan (Iran). The roots (1 kg) were shade dried for two days at a temperature of 20 ± 5°C followed by being grinded with an electric grinder and completely powdered with a laboratory mill. Next, 100 g of the resulting powder was poured into a percolator. After 72 hours of shaking on a rotary shaker, the extract was passed through a filter paper and dissolved in a solvent (70% ethanol) utilizing a rotary machine which was used to condense the berberine extract. Finally, the obtained extract was stored in a refrigerator at 4°C. The concentration of berberine extract was determined by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (BFRL, China) and the standard commercial berberine (Berberine chloride, Sigma Aldrich). The column used in this machine was C18 with a diameter and height of 4.6 cm and 25 cm, respectively. The pump was SY-type which was also equipped with a UV/VIS detector. Moreover, measurements were performed at a wavelength of 330 nm with a flow rate of 1 mL/min, and the volume of each injection set was 25 μL. The mobile phase was ethanol (50%) and water (50%) prepared for HPLC. The rats in supplemented and combined intervention groups received 10 mg/kg of berberine extract 5 days a week through gavage [14].

2.3. Exercise Protocol

The rats were transferred to Razi Research Center of Lorestan and were left undisturbed for a week to get habituated to their new conditions. Subsequently, the animals were made to run 10 minutes a day for a week at speeds of 10-20 m/min to be familiarized with the treadmill, prior to allocating them to the following groups at random: (1) trained group (IR after HIIT), (2) supplemented group (IR after berberine supplementation), (3) combined group (IR after HIIT and berberine supplementation), and (4) IR group (IR without intervention).

The exercise protocol included five sessions of interval running per week on a treadmill for 8 consecutive weeks. Each session consisted of 5 minutes of warming up, 5 minutes of cooling down period, and 30 minutes of interval running at speeds of 29-36 m/min (equivalent to 50-90% VO2max) on a fixed incline of one percent. In the first week, each session comprised 5 intervals, each of which consisted of 30-35 seconds of high-intensity running at a speed of 29 m/min with 1-minute rest time in between (active recovery at 20 m/min, equivalent to 50-60% VO2max). Each week, the number of intervals, their duration, and the running speed were gradually increased without changing the resting time. At the eighth week, the rats were subjected to twelve 75-second intervals at a speed of 36 m/min [17].

2.4. Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury

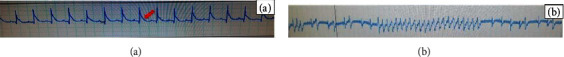

Forty-eight hours after the last exercise session and supplementation, the animals were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg), which took effect within 5 minutes. After that, fur was shaved, and the rats were fixed to a surgical bed for intubation, following which the animals were connected to a ventilator (Small Animal Ventilator, Harvard Model 683-USA) with a respiratory rate of 60-70 breaths per minute and a volume of 15 mL/kg. To stabilize body temperature, the surgical bed was equipped with a thermal pad with a mean temperature of 37 ± 1°C. Besides, occurrence of infarction was monitored by lead II recording, using a PowerLab electrocardiogram (ML750 Power Lab/4sp, AD Instruments). To induce the ischemia, a cross-cut of approximately 2 cm was made on the chest in the fourth left intercostal space to gain access to the heart. After gently rupturing the pericardium with small forceps, a silk thread (12 mm, USB6.0) was passed below the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery at a point of 2 mm under the left atrium and then pulled and tied to create experimental ischemia [3, 12]. The mean heart rate was calculated by an electrocardiogram (ECG). Also, ECG was used to monitor the successful blocking of LAD and changes in ECG, including ST-segment elevation (Figure 1(a)), premature ventricular contractions, and ventricular tachycardia in the electrocardiogram (Figure 1(b)). Thirty minutes after the blockage of LAD, the reperfusion maneuver was performed to restore blood flow to the myocardium. Then, the chest was closed by being sutured with silk thread (30 mm, USB 3.0), and tetracycline ointment was applied to the sutured area [3, 12].

Figure 1.

Electrocardiogram changes in ischemic rats. (a) ST segment elevation. (b) Premature ventricular contractions (PVC) and ventricular tachycardia (V Tach).

2.5. Creatine Kinase-MB (CK-MB) Measurement

1 day after the surgery, anesthetization was performed with ketamine and xylazine (100 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg, respectively). In order for sampling the blood from the jugular vein, the rats were held by grasping the loose skin of the back firmly with fingers and elevating their heads. We shaved the hairs on the back of the neck and disinfected it with alcohol. By using a 1 mL syringe, a 25-gauge needle was inserted into the jugular vein through the pectoral muscle below the sternoclavicular junction. The blood was withdrawn slowly to avoid the collapse of these vessels, and approximately 1.5 mL blood was collected. After using a plastic tubing cutter to cut the syringe, the collected samples were transferred into heparin-coated capillary tubes and centrifuged at 4°C and 10,000 × g for 10 min. The plasma samples were stored at −80°C until the analyzing time. The blood plasma sample of each rat was prepared by a commercial kit (Pars Azmoon, Iran) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. In addition, the changes in the serum CK-MB levels were measured by a spectrophotometer (Cecil CE 7200).

2.6. Measurement of Echocardiography Indices

7 days after the surgery, anesthetization was performed with ketamine and xylazine (100 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg, respectively). Then, the chest was shaved, and the animal was placed on its back. Echocardiography was carried out by an echocardiography machine (M-Mode, Landwind Medical, p09 Specification, China) equipped with a 10 MHz transducer. Different echocardiographic indices were obtained according to the instructions of the American Society of Echocardiography [12]. Besides, the stroke volume (SV) was calculated from the difference between the end-systolic volume and end-diastolic volume (SV = diastolic volume − systolic volume), and the cardiac output is a product of the heart rate and the stroke volume (CO = stroke volume × heart rate). Also, the percent of muscle shortening (% FS) and injection fraction (% EF) was calculated as follows: %FS = ((LVEDD − LVESD)/LVEDD) × 100; %EF = (stroke volume/diastolic volume) × 100 [18].

2.7. Collecting Heart Tissues

After echocardiography, the chest was opened, and the heart was quickly excised. Next, the heart was rinsed with distilled water, snap frozen upon removal of atria and vascular root, and weighed. In addition, the heart weight (HW) to body weight (BW) ratio and HW to tibia length (TL) ratio were calculated [19]. The heart biopsy was performed at 1 mm far from the damaged area of the rat's heart [12]. After that, the tissue samples were quickly frozen in liquid N2 for further analyses. The duration of the process was less than 2 min. Finally, the target tissues were stored at -80° C.

2.8. Caspase-3 Protein

Total lysates were prepared from left ventricular tissue of the infarct area one week after reperfusion. Capsase-3 levels were measured by ELISA kit (ZellBio, Germany, Cat#GB-326-1) as per the manufacturer's recommendations. In brief, 40 μL of each lysate, along with standard caspase-3, was incubated with caspase antibody for 60 minutes. Following this incubation, the wells were washed and incubated with streptavidin-HRP for 60 minutes at 37°C. After that, the plates were washed again, and chromogenic substrate was added to each well which incubated for 10 minutes followed by addition of stop solution. The optical density of each well was read on an ELISA plate reader.

2.9. Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reactions

RNA was extracted using tissue/Max Spin super RNA extraction kit (Maxcell, Iran) based on the manufacturer's recommendations. cDNA was also synthesized using a cDNA Synthesis Kit (Yekta Tajhiz, Iran). Also, PCR primers were purchased from SinaClon (Iran) (Table 1). PCR reactions were set up as follows: 1 μL of SYBR Green master mix (Yekta Tajhiz, Iran) was mixed with 5 μL of RNase-free water. 1 μM of both forward and reverse primers and 100 ng of cDNA templet were added to the above mix and subjected to amplification cycles. The β-actin mRNA was used as the reference gene. The target gene expression was quantified using the formula 2−ΔΔCT [12].

Table 1.

Primer sequence of selected angiogenic and angiostatic genes.

| Gene | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| VEGF | TGTGTGTGTGTATGAAATCTGTG | GCAGAGCTGAGTGTTAGCAA |

| FGF | ACGGCTGCTGGCTTCTAAGTG | AGTTCGTTTCAGTGCCACATACC |

| TSP-1 | TCGCAAAGTGACGGAAGAGAAC | ATTGGAGCAGGGCATGATGG |

| ENDO | ACTGCCTGGATGAAGAAGATGATG | CGTAGATATGTCTCCTGCCTGTG |

| β-Actin | GTAACCCGTTGAACCCCATT | CCATCCAATCGGTAGTAGCG |

β-Actin: beta-actin; ENDO: endostatin; FGF: fibroblast growth factor; TSP-1: thrombospondin-1; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor.

2.10. Infarct Size Measurement

2 mm slices were made from the left ventricle (from base to apex) of the frozen hearts by graded molds. Next, the container containing the tetrazolium solution was inserted into the bain-marie at 37° C. Then, the heart was immersed in a bain-marie for 15–20 minutes. It is observed that the infarct areas due to necrosis and the loss of intracellular dehydrogenase enzymes could not react with tetrazolium, and, as a result, these areas turn yellow to white. To increase the contrast of dark red and white areas, the slices were fixed in 10% formalin for 48 h. After this period, scans were obtained from the tissues. Then, with Photoshop software (Adobe Photoshop, 2019), the surface area of necrotic or infarct zones were calculated as a percentage of the infarcted left ventricle [12].

2.11. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses and comparisons were performed in SPSS version 23. The comparison between the groups was performed in terms of Mean ± SEM of the results at p ≤ 0.05 significance level. After establishing the normality of data distribution by Shapiro-Wilk test, they were further analyzed with one-way ANOVA and Turkey's post hoc test [3].

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics

Measurement of the heart weights did not reveal any difference amongst the cohorts (Table 2). At the completion of the treatment, we detected reduced body mass in all experimental groups compared to IR group (p = 0.01) (Table 2). The heart weight to body weight ratio, however, was only increased in the trained and the combined groups in comparison with IR rats (p = 0.01) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of the rats in different groups.

| Groups | Trained | Supplemented | Combined | IR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Age (week) | 8-10 | 8-10 | 8-10 | 8-10 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 376 ± 3.02 | 378 ± 1.93 | 375 ± 2.32 | 368 ± 2.48 |

| Heart weight (g) | 0.91 ± 0.04 | 0.90 ± 0.06 | 0.90 ± 0.08 | 0.78 ± 0/01 |

| Body weight (g) | 266 ± 20∗ | 277 ± 50∗ | 265 ± 10∗ | 319 ± 70 |

| Heart weight/body weight (g) | 0.003 ± 0.0001∗ | 0.002 ± 0.0001 | 0.002 ± 0.0003∗ | 0.002 ± 0.0004 |

| Heart weight/tibia length (g/mm) | 0.023 ± 0.003 | 0.023 ± 0.002 | 0.022 ± 002 | 0.019 ± 001 |

Data are presented as Mean ± SEM. ∗Significant difference in comparison with IR group. p < 0.05.

3.2. Echocardiographic Data

Stroke volume (SV), cardiac output (CO), fractional shortening (FS), and ejection fraction (EF) had a significant increase in three intervention groups compared to IR group (p = 0.01). EF was 51.74 ± 0.06% in IR group and 63.5 ± 0.9, 63.4 ± 0.4, and 64.7 ± 0.9 in three intervention groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

The mean cardiac echocardiography indexes of the rats in different groups at 1-week post IR.

| Groups | Train | Supplemented | Combined | IR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SV (mL) | 187.77 ± 6.92∗ | 184.10 ± 15.00∗ | 195.21 ± 16.43∗ | 128.45 ± 6.42 |

| CO (mL/min) | 70 ± 27∗ | 69 ± 13∗ | 73 ± 16∗ | 57 ± 12 |

| EF (%) | 63.5 ± 0.9∗ | 63.4 ± 0.4∗ | 64.7 ± 0.9∗ | 51.74 ± 0.6 |

| FS (%) | 35 ± 0.6∗ | 35 ± 0.7∗ | 36 ± 0.2∗ | 27 ± 0.8 |

SV: stroke volume; CO: cardiac output; EF: left ventricular ejection fraction; FS: fractional shortening. Values are means ± standard deviations. The data are mean ± sem. ∗Sign of significant difference with IR group. ∗p ≤ 0.05.

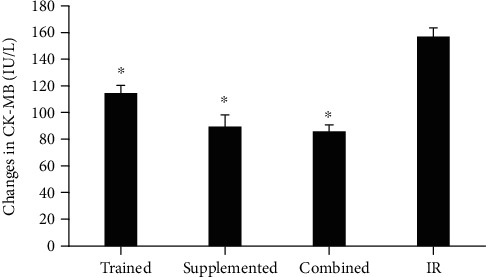

3.3. Creatine Kinase-MB

As depicted in Figure 2, serum level of CK-MB was increased in IR group, and CK-MB elevations were more modest in intervention groups than those in IR group at day one of postreperfusion (p = 0.01) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Creatine kinase-MB changes in different groups after 1 day of ischemia-reperfusion. ∗Significant difference in comparison with IR group. p < 0.05.

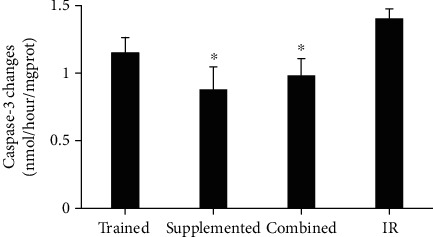

3.4. Caspase-3

ELISA analysis revealed a significant reduction in Caspase-3 levels in supplemented and combined groups compared to IR group (p = 0.01) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Caspase-3 changes in different groups after 7 days of ischemia-re in rat heart tissue. ∗Significant of difference in comparison with IR group. p < 0.05.

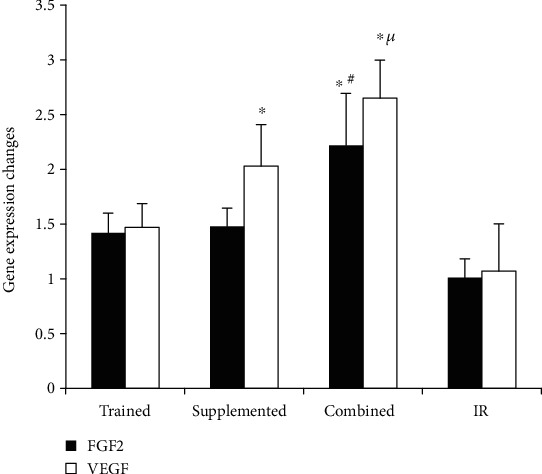

3.5. Gene Expressions in the Border Zone Left Ventricular

Q-PCR analysis revealed some alterations in the expression of angiogenesis-related genes in myocardial tissues among different experimental rat groups. In this analysis, VEGF transcript levels were elevated in supplemented group compared to that of IR group. Also, an increase in VEGF was observed in the combined group compared to the trained and IR groups (p = 0.001). Interestingly, elevated levels of FGF2 transcripts were only detected in the myocardial tissues of the rats subjected to this later regiment (p = 0.001) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Fibroblast growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor gene expression changes in the heart tissue. ∗Significant difference in comparison with IR group. #Significant difference in comparison with trained and supplemented group. μSignificant difference in comparison with trained group. p < 0.05.

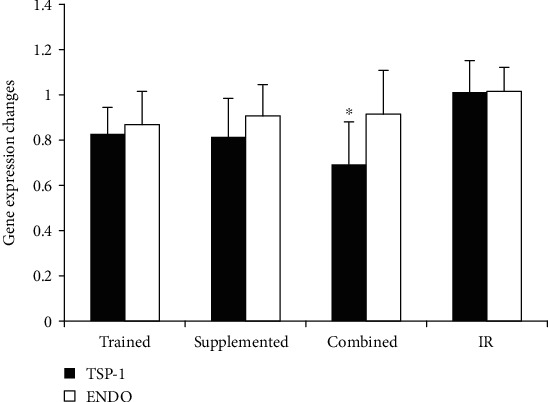

Analysis of angiogenic inhibiting factors showed that neither TSP-1 nor ENDO was reduced at mRNA level by either training or supplement treatment separately. The only significant reduction in TSP-1 transcript was discerned in the rat under combined treatment (p = 0.01) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Endostatin and thrombosponidin-1 gene expression changes in the heart tissue. ∗Significant difference in comparison with IR group. p < 0.05.

In conclusion, these data suggest that although training or berberine treatment separately can support angiogenesis in ischemic myocardial tissue, the combination of them synergizes to exert a larger effect.

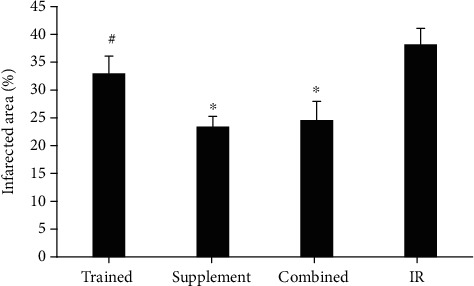

3.6. Infarct Size

The size of the infarct area was smaller in supplemented and combined cohorts of rats (supplemented 23.4 ± 1.85% and combined 24.6 ± 3.36%) with respect to that of IR (38.2 ± 2.86%) and trained rats (33 ± 3.08%) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Infarct size area in different groups after 7 days of ischemia-reperfusion in the heart tissue of the rats. ∗Significant difference in comparison with IR group. #Significant difference in comparison with supplement and combined groups. p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

Our results indicated a higher heart to body weight ratio in the trained and combined treated rats as opposed to the IR group. Also, despite the decrease in heart rate in the intervention groups compared to the IR, but with an increase in stroke volume, an improvement in heart function was shown.

The infarct size is an appropriate indicator of cardiac resistance to IR injury [3], and the role of apoptosis in regulating infarct size has been shown before [20]. In this regard, there is an elevation of caspse-3 expression a few hours after reperfusion, which lasts for several weeks [20, 21].

This study found that the combination of HIIT and berberine, as preconditioning factors, reduced caspase-3 and infarct size in intervention groups. In support of our findings, there is evidence that angiogenic factors, such as VEGF and FGF2, impact apoptosis by regulating the expression of antiapoptotic proteins such as BCL-2, surviving, and XIAP, through activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-mediated Akt )PI3K/Akt( pathway and increasing nitric oxide [10, 22] . Also, angiostatic factors such as THPS-1 and ENDO are known to activate caspase-3 and apoptosis through dephosphorylation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase, depletion of BCL- and BCL-XL and activation of p38 group of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases (P38 MAPK pathway) [10, 21].

Creatine kinase-MB is a biomarker of heart damage due to its highly regulated balance in the cardiac tissue [23]. The serum level of CK-MB reaches its peak 24 hours after ischemia and returns to basal level within 72 hours [24]. High serum CK-MB levels in our model is indicative of damage to the cardiac tissue. The protective role of both HIIT and berberine treatment, seperataley or in combination, against the cardiac damage is shown by reduced serum levels of creatine kinase-MB in our study.

Our findings also uncovered regulations exerted by different treatments on the gene expression of angiogenesis factors in the injured tissue. The increase of VEGF mRNA to a greater extent in the supplemented and combined groups indicates that exercise can be more effective if combined with berberine treatment, in line with Yardley et al. [25] observations. Our data, however, are in contrast to that of Nazarali et al. [26]. This inconsistency is likely to stem from the presence or lack of ischemia-reperfusion injury in the rats, the type and intensity of exercises, the age of the animals, and the target tissue. Hemodynamic angiogenesis stimuli, such as physical activity, are known to increase the level of nitric oxide by creating shear stress and activating ion channels (e.g., potassium channels). Nitric oxide, in turn, elevates the myocardial VEGF levels, thereby promoting angiogenesis [26, 27].

Although the role of fibroblast growth factor family in angiogenesis of the heart has not fully understood yet, FGF2 is a known stimulator of endothelial cell proliferation and the physical organization of endothelial cells [28, 29]. In our experimental IR condition, the detection of elevated FGF2 in the surrounding tissue upon ischemia is indicative of its role in promoting angiogenesis in ischemic tissue. Considering that hypoxia, NO, and NADPH factors also regulate FGF2 expression in the repairing tissues [28, 30, 31], the significant increase in the myocardial FGF2 in the combined group suggests that the surrounding tissue of damaged myocardium has probably healed sooner and has experienced improved blood reperfusion. Some studies have reported that an increased FGF2 expression occurs at high volumes of exercise in subjects with high body fat [32]. Furthermore, although berberine supplementation increases angiogenesis [15], the dose of berberine in our study may not have been sufficient to increase FGF2 significantly.

In addition to regulating the rate of blood flow during intense exercise, endostatin can act as both pro- and antiangiogenic factor through stimulation of VEGF-dependent endothelial cells proliferation and induction of apoptosis, respectively [27, 33]. In line with Brixius et al. report [33], we did not find any changes in myocardial expression of endostatin in ischemic tissues.

Our results demonstrated a significant reduction in levels of TSP-1 in the ischemic tissue of the rats treated with combination of berberine and HIIT. TSP-1 exerts its antiangiogenic effect through several mechanisms including, but not limited to, inhibition of endothelial cell cycle progression and mobilization, blocking VEGF and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling pathways, and altering the function of NO and apoptosis in endothelial cells [8, 34, 35]. Given the natural increase of TSP-1 level after ischemia in the area near to the site of infarction [8], which leads to a limited spread of granulation tissue, our observations indicate the effectiveness of this combined treatment in improving wound healing process. Berberine has also been shown to promote angiogenesis in the ischemic myocardial tissue through activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-mediated Akt- (PI3K/Akt-) dependent signaling and AMPK in endothelial cells [15].

5. Conclusion

In brief, our study demonstrates that the combined use of berberine extract and HIIT can lead to significant changes in the myocardial levels of angiogenic (VEGF and FGF2), angiostatic (TSP-1) factors and caspase-3 protein, 7 days after reperfusion. However, it can be said that HIIT and berberine, solely or in combination, reduce caspase-3 and the size of myocardial infarction. Nevertheless, when these interventions combined, they have a greater effect on the expression of the angiogenesis gene in the infarcted heart. These changes were manifested as an increase in the levels of the former and a decrease in the levels of the later agents. We suggest that this combined intervention can be considered as an important precautionary method in myocardial infarction events.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research Promotion from Bu-Ali Sina University, Hamedan (grant number: 1011235).

Abbreviations

- IR:

Ischemia-reperfusion

- HIIT:

High-intensity interval training

- VEGF:

Vascular endothelial cell growth factor

- FGF2:

Fibroblast growth factor

- TSP-1:

Thrombospondin-1

- ENDO:

Endostatin

- PII:

Pasteur institute of Iran

- HPLC:

High-performance liquid chromatography

- PI3K/Akt:

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-mediated Akt

- P38 MAPK pathway:

p38 group of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases

- LAD:

Left anterior descending

- ERK:

Extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- β-Actin:

Beta-actin

- PVC:

Premature ventricular contractions

- V Tach:

Ventricular tachycardia.

Data Availability

The datasets generated/analyzed during the current study are available.

Ethical Approval

All the investigations were carried out in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and the study protocol was confirmed by the animal's ethics committee at Bu-Ali Sina University of Hamedan (code: IR.BASU.REC.1398.041).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' Contributions

PB participated in the design of the experiment, collection of data, and interpretation of results; FN participated in the design of the experimental study and data evaluations; AN has an effective role in the use of facilities and technical assistance management; and AR participated in review. However, the authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript, as well as agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

References

- 1.Gu M., Zheng A. B., Jin J., et al. Cardioprotective effects of genistin in rat myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury studies by regulation of P2X7/NF-κB pathway. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2016;2016:9. doi: 10.1155/2016/5381290.5381290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lejay A., Fang F., John R., et al. Ischemia reperfusion injury, ischemic conditioning and diabetes mellitus. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2016;91:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rahimi M., Shekarforoush S., Asgari A. R., et al. The effect of high intensity interval training on cardioprotection against ischemia-reperfusion injury in wistar rats. EXCLI Journal. 2015;14:237–246. doi: 10.17179/excli2014-587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang J. Q., Wilson B. S., Garza M. A. Post-myocardial infarction exercise training induces angiogenesis in the heart. Journal of Clinical Trials in Cardiology. 2018;5(1):1–5. doi: 10.15226/2374-6882/5/1/00146. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Go A. S., Mozaffarian D., Roger V. L., et al. Executive summary: heart disease and stroke statistics--2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129(3):399–410. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000442015.53336.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Almeida I., Oliveira Gomes A., Lima M., Silva I., Vasconcelos C. Different contributions of angiostatin and endostatin in angiogenesis impairment in systemic sclerosis: a cohort study. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. 2016;34 Suppl 100(5):37–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gogiraju R., Bochenek M. L., Schäfer K. Angiogenic endothelial cell signaling in cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2019;6:p. 20. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2019.00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schellings M. W. M., van Almen G. C., Sage E. H., Heymans S. Thrombospondins in the heart: potential functions in cardiac remodeling. Journal of Cell Communication and Signaling. 2009;3(3-4):201–213. doi: 10.1007/s12079-009-0070-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barroso M. C., Boehme P., Kramer F., et al. Endostatin a potential biomarker for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Arquivos Brasileiros de Cardiologia. 2017;109(5):448–456. doi: 10.5935/abc.20170144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dimmeler S., Zeiher A. M. Endothelial cell apoptosis in angiogenesis and vessel regression. Circulation Research. 2000;87(6):434–439. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.87.6.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teringova E., Tousek P. Apoptosis in ischemic heart disease. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2017;15(1):87–87. doi: 10.1186/s12967-017-1191-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ranjbar K., Nazem F., Nazari A., et al. Synergistic effects of nitric oxide and exercise on revascularisation in the infarcted ventricle in a murine model of myocardial infarction. EXCLI Journal. 2015;14:1104–1115. doi: 10.17179/excli2015-510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yao J., Kong W., Jiang J. Learning from berberine: treating chronic diseases through multiple targets. Science China Life Sciences. 2015;58(9):854–859. doi: 10.1007/s11427-013-4568-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y. J., Yang S. H., Li M. H., et al. Berberine attenuates adverse left ventricular remodeling and cardiac dysfunction after acute myocardial infarction in rats: role of autophagy. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology. 2014;41(12):995–1002. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu M.-L., Yin Y. L., Ping S., et al. Berberine promotes ischemia-induced angiogenesis in mice heart via upregulation of microRNA-29b. Clinical and Experimental Hypertension. 2017;39(7):672–679. doi: 10.1080/10641963.2017.1313853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu G., Rana J. S., Wykrzykowska J., et al. Exercise-induced expression of VEGF and salvation of myocardium in the early stage of myocardial infarction. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2009;296(2):H389–H395. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01393.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rahmati-Ahmadabad S., Department of Exercise Physiology, Central Tehran Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran, Azarbayjani M., Department of Exercise Physiology, Central Tehran Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran, Nasehi M., Cognitive and Neuroscience Research Center (CNRC), Tehran Medical Sciences Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran The effects of high-intensity interval training with supplementation of flaxseed oil on BDNF mRNA expression and pain feeling in male rats. Annals of Applied Sport Science. 2017;5(4):1–12. doi: 10.29252/aassjournal.5.4.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Darbandi Azar A., Tavakoli F., Moladoust H., Zare A., Sadeghpour A. Echocardiographic evaluation of cardiac function in ischemic rats: value of m-mode echocardiography. Research in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2014;3(4, article e22941) doi: 10.5812/cardiovascmed.22941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen H.-H., Zhao P., Zhao W. X., et al. Stachydrine ameliorates pressure overload-induced diastolic heart failure by suppressing myocardial fibrosis. American Journal of Translational Research. 2017;9(9):4250–4260. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palojoki E., Saraste A., Eriksson A., et al. Cardiomyocyte apoptosis and ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction in rats. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2001;280(6):H2726–H2731. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.6.H2726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang X., Guo Z., Ding Z., Mehta J. L. Inflammation, autophagy, and apoptosis after myocardial infarction. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2018;7(9, article e008024) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.008024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chavakis E., Dimmeler S. Regulation of endothelial cell survival and apoptosis during angiogenesis. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2002;22(6):887–893. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000017728.55907.A9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laposy C. B., Freitas S. . B. Z., Louzada A. N., et al. Cardiac markers: profile in rats experimentally infected with Toxocara canis. Revista Brasileira de Parasitologia Veterinária. 2012;21(3):291–293. doi: 10.1590/S1984-29612012000300020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson J. L., Adams C. D., Antman E. M., et al. ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non–ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction—Executive Summary. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2007;50(7):652–726. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yardley M., Ueland T., Aukrust P., et al. Immediate response in markers of inflammation and angiogenesis during exercise: a randomised cross-over study in heart transplant recipients. Open Heart. 2017;4(2, article e000635) doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2017-000635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nazarali P. Effect of high-intensity interval training (HIIT) on vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in heart muscle in healthy rats. Research Journal of Fisheries and Hydrobiology. 2015;10 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suhr F., Brixius K., de Marées M., et al. Effects of short-term vibration and hypoxia during high-intensity cycling exercise on circulating levels of angiogenic regulators in humans. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2007;103(2):474–483. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01160.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao T., Zhao W., Chen Y., Ahokas R. A., Sun Y. Acidic and basic fibroblast growth factors involved in cardiac angiogenesis following infarction. International Journal of Cardiology. 2011;152(3):307–313. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.House S. L., Wang J., Castro A. M., Weinheimer C., Kovacs A., Ornitz D. M. Fibroblast growth factor 2 is an essential cardioprotective factor in a closed-chest model of cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury. Physiological Reports. 2015;3(1, article e12278) doi: 10.14814/phy2.12278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Virag J. A. I., Rolle M. L., Reece J., Hardouin S., Feigl E. O., Murry C. E. Fibroblast growth factor-2 regulates myocardial infarct repair: effects on cell proliferation, scar contraction, and ventricular function. The American Journal of Pathology. 2007;171(5):1431–1440. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang Z.-S., Padua R. R., Ju H., et al. Acute protection of ischemic heart by FGF-2: involvement of FGF-2 receptors and protein kinase C. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2002;282(3):H1071–H1080. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00290.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brenner D. R., Ruan Y., Adams S. C., Courneya K. S., Friedenreich C. M. The impact of exercise on growth factors (VEGF and FGF2): results from a 12-month randomized intervention trial. European Review of Aging and Physical Activity. 2019;16(1):p. 8. doi: 10.1186/s11556-019-0215-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brixius K., Schoenberger S., Ladage D., et al. Long-term endurance exercise decreases antiangiogenic endostatin signalling in overweight men aged 50–60 years. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2008;42(2):126–129. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2007.035188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olfert I. M., Breen E. C., Gavin T. P., Wagner P. D. Temporal thrombospondin-1 mRNA response in skeletal muscle exposed to acute and chronic exercise. Growth Factors. 2009;24(4):253–259. doi: 10.1080/08977190601000111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lawler J. Thrombospondin-1 as an endogenous inhibitor of angiogenesis and tumor growth. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 2002;6(1):1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2002.tb00307.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated/analyzed during the current study are available.