Background

High frequency of MNNG HOS transforming (MET) exon 14 skipping mutation (MET exon 14Δ) has been reported in pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinomas (PSCs). However, the frequencies differ greatly. Our study aims to investigate the frequency of MET alterations and the correlations among MET exon 14Δ, amplification, and protein overexpression in a large cohort of PSCs. MET exon 14Δ, amplification, and protein overexpression were detected in 124 surgically resected PSCs by using Sanger sequencing, fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH), and immunohistochemistry (IHC) respectively. MET exon 14Δ was identified in 9 (7.3%) of 124 cases, including 6 pleomorphic carcinomas, 2 spindle cell carcinomas and 1 carcinosarcoma. MET amplification and protein overexpression were detected in 6 PSCs (4.8%) and 25 PSCs (20.2%), respectively. MET amplification was significantly associated with overexpression (P < 0.001). However, MET exon 14Δ has no correlation with MET amplification (P = 0.370) and overexpression (P = 0.080). Multivariable analysis demonstrated that pathologic stage (hazard ratio [HR], 2.78; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.28–6.01; P = 0.010) and MET amplification (HR, 4.71; 95% CI, 1.31–16.98; P = 0.018) were independent prognostic factors for poor median overall survival (mOS). MET alterations including MET exon 14Δ and amplification should be recommended as routine clinical testing in PSCs patients who may benefit from MET inhibitors. MET IHC appears to be an efficient screen tool for MET amplification in PSCs.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; FFPE, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded; FISH, fluorescent in situ hybridization; GCN, gene copy number; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; HR, hazard ratio; IHC, immunohistochemistry; MET, MNNG HOS transforming; mOS, median overall survival; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PSCs, pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinomas; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitors; WHO, World Health Organization

Introduction

Pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinomas (PSCs) are a rare type of lung cancer with a poor prognosis. It approximately accounts for 0.1–0.4% of all lung cancer [[1], [2], [3]]. According to the 2015 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of lung tumors, PSCs are defined as a subgroup of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) that contain a component of sarcoma-like or sarcoma elements and are divided into five histological subtypes: pleomorphic carcinoma, spindle cell carcinoma, giant cell carcinoma, carcinosarcoma, and pulmonary blastoma [4]. PSCs usually have a poor response to chemoradiotherapy, and surgical resection remains the primary treatment [[5], [6], [7]].

MNNG HOS transforming (MET) gene is a proto-oncogene located on chromosome 7 band 7q21–q31, consisting of 21 exons separated by 20 introns [8,9]. Activation of the MET signaling pathway such as Mek/erk and PI3K/Akt could lead an array of cellular responses including proliferation, scattering, differentiation, and apoptosis [10,11]. MET gene abnormality can be distributed to various mechanisms, including amplification, exon mutation, and overexpression [12,13].

De novo MET amplification occurs in 1% to 5% of lung cancers and acquired MET amplification could also be detected in about 20% of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI)-resistant tumors [14,15]. MET overexpression in NSCLC is variable, ranging from 22.2–74.5% [[16], [17], [18]]. Both MET amplification and overexpression have been reported to be associated with a poor prognosis in NSCLC patients [19,20]. MET exon 14 skipping mutation (MET exon 14Δ) has been discovered as another driver mechanism that prevails in approximately 3.0–4.0% of lung adenocarcinoma [21]. Recently, a growing body of evidence has shown that MET inhibitors, such as crizotinib, capmatinib, and tepotinib, produced a good clinical response in NSCLC patients with MET exon 14Δ, suggesting that MET exon 14Δ is an attractive target for lung cancer treatment [[22], [23], [24]].

In recent years, a higher frequency of MET exon 14Δ has been reported in PSCs, with a prevalence ranging from 4.9% to 31.8% [25,26]. However, frequencies reported from previous studies vary widely, and available data on the correlation of MET alterations and overexpression in PSCs are sparse. Therefore, we conducted this multi-institutional study to determine the prevalence of MET alterations and the relationship among MET exon 14Δ, amplification, and overexpression in a large cohort of Chinese PSCs patients.

Materials and methods

Patients and specimens

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board and the academic committee of Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Center (B2020-139-01), and the exception to the requirement of informed consent was approved. Tissue samples were obtained from 134 PSCs patients who underwent surgical resection between November 1999 and October 2015 at nine institutions in China. All samples were taken from archived formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) specimens and Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining showing tumor cellularity > 50% were utilized. The diagnosis of all samples was confirmed by two experienced pathologists (Y.Z. and F.W.) according to the 2015 WHO criteria of lung tumors. We excluded 6 cases who had been misdiagnosed and 4 cases who failed to perform DNA extraction. Ultimately, 124 PSCs were enrolled in our study. Clinical data on demographics and tumor features were extracted from the medical records of each patient. The pathological staging was performed according to the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer.

Sanger sequencing

Each 5-um-thick slide of the FFPE sample was divided into the tumor and non-tumor regions by a pathologist reviewing H&E staining slides and only tumor regions were collected to perform DNA extraction. E.Z.N.A.™ FFPE DNA Isolation kits (OMEGA, Norcross, GA, USA) were used to perform DNA extraction according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA concentrations were measured using the Qubit dsDNA assay (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). DNA with an A260/A280 ratio of 1.8–2.0 was used for PCR amplification. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primer sets for MET exon 14 and franking introns were as follows: forward, 5′-TGTCGTCGATTCTTGTGTGC-3′; reverse, 5′-CTTCTGGAAAAGTAGCTCGGT-3′; and forward, 5′-CATTTGGATAGGCTTGTAAGTGC-3′; reverse, 5′-TCAAATACTTACTTGGCAGAGGT-3′, respectively. Next, primer sets specific for MET exon 14Δ products were combined with 2ul of DNA in PCR reactions. Finally, 20ul successfully amplified PCR products were directly sequenced using Sanger bidirectional sequencing reactions.

Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH)

4-μm-thick slides of FFPE were used with Vysis MET SpectrumRed FISH Probe and Vysis centromere of chromosome 7 (CEP7) SpectrumGreen Probe (Abbott Molecular, Chicago, IL, USA) to investigate MET gene copy number (GCN) status according to the manufacturer's instructions. The red fluorescent probe specific for the MET gene and the green fluorescent probe as a reference locus of MET specific for the CEP7. Gene GCN was reported by two methods: mean MET copy number per cell (mean MET/cell) and the MET copy number per centromere 7 ratio (MET/CEP7) [27]. MET gene and CEP7 copy number per cell and MET/CEP7 ratio were counted in at least 50 non-overlapping tumor cell nuclei, at a magnification of 100 x. MET amplification was defined according to the previously reported study, proposed as follows: MET gene mean copy number no less than 5 and a MET/CEP7 ratio greater than 2 [28]. Otherwise, a tumor was defined as negative amplification.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

MET IHC evaluation was performed using Confirm anti-Total c-MET (SP44) rabbit monoclonal antibody (Ventana Medical Systems, USA). IHC was carried out on the VENTANA Benchmark XT stainer using Ultraview detection system according to the manufacturer's instruction. The expression level of MET protein was recorded with the H-score assessment combining staining intensity (0–3) and the percentage of positive cells (0–100%) [29]. There were four staining scores as follows: 3+ (≥50% of tumor cells staining with strong intensity); 2+ (≥50% of tumor cells with moderate or higher staining but <50% of tumor cells with strong intensity); 1+ (≥50% of tumor cells with weak or higher staining but <50% of tumor cells with moderate or higher intensity); 0+ (no staining or <50% of tumor cells with any staining intensity). Score 2+ and score 3+ were defined as positive MET IHC or MET protein overexpression. Otherwise, a tumor was defined as negative MET IHC. IHC findings were analyzed by two independent investigators.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 22.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Pearson's chi-squared test and Fisher's exact test were used to analyze the correlations of MET exon 14Δ, amplification, and overexpression with clinical-pathological variables. Median overall survival (mOS) was determined from the date of disease diagnosis to patients' death due to any cause. mOS was analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test. The Cox proportional hazards regression model was used for univariable and multivariable survival analyses.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 124 PSCs patients from nine medical centers were enrolled in our study. The detailed clinical-pathologic characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Among these patients, the median age at disease onset was 61 years (range, 30 to 84 years), 108 (87.1%) were male, and 85 (68.5%) were ever-smokers. The most common histological subtype was pleomorphic carcinoma (n = 89, 68.7%), followed by carcinosarcoma (n = 17, 13.7%) and spindle cell carcinoma (n = 11, 8.9%). At the time of diagnosis, 115 (92.7%) patients had stage I-IIIA disease, and nine (7.3%) had stage IIIB-IV disease.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of PSCs (N = 124).

| Characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 108 (87.1) |

| Female | 16 (12.9) |

| Age | |

| Median (range), years | 61 (30–84) |

| <65 | 101 (81.5) |

| ≥65 | 23 (18.5) |

| Smoking history | |

| Smoker | 85 (68.5) |

| Non-smoker | 39 (31.5) |

| Histologic subtype | |

| Pleomorphic carcinoma | 89 (71.8) |

| Spindle cell carcinoma | 11 (8.9) |

| Giant cell carcinoma | 6 (4.8) |

| Carcinosarcoma | 17 (13.7) |

| Pulmonary blastoma | 1 (0.80) |

| Pathologic stage | |

| I–IIIA | 115 (92.7) |

| IIIB–IV | 9 (9.3) |

Abbreviations: PSCs, pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinomas.

Among the 89 pleomorphic carcinomas, 76 patients had a biphasic tumor, with an epithelial component consisting of adenocarcinoma in 52 (68.4%) cases, squamous cell in 15 (19.7%) cases, and other histology types, including six (7.9%) large cell carcinoma and three (3.9%) adenosquamous carcinoma. The rest of the 13 pleomorphic carcinomas were a mixture of sarcomatous components of spindle cells and giant cells.

MET exon 14Δ in PSCs

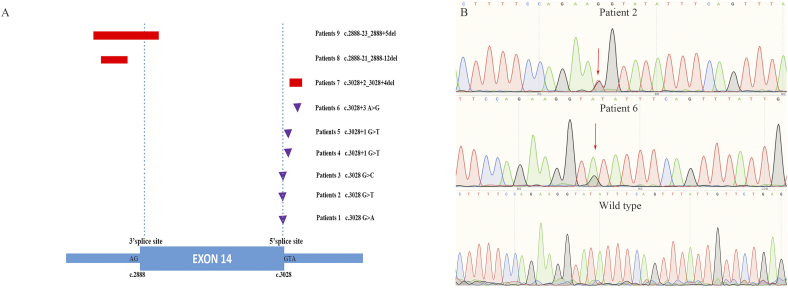

By PCR-direct sequencing, nine (7.3%) patients harboring MET exon 14Δ were identified, including six pleomorphic carcinomas, two spindle cell carcinomas, and one carcinosarcoma. The clinical and pathological characteristics of nine patients are listed in Table 2. Patients predominantly male (66.7%), with age < 65 (62.5%), and had a history of smoking (62.5%). All patients (100.0%) had pathologic stage I-IIIA disease. No significant differences were found in ages, gender, smoking status, histological subtypes, and pathologic stage between patients with or without MET exon 14Δ (Supplemental Table S1). The locations of MET exon 14Δ and its franking introns are presented in Fig. 1A, including 6 point mutations and 3 deletions. Representative MET exon 14Δ and wild type by bidirectional Sanger sequencing are showed in Fig. 1B.

Table 2.

Clinical-pathologic features of nine PSCs with MET exon 14 mutation.

| Number | Gender | Age | Smoking status | Pathologic stage | Histologic subtype | Epithelial components | Sarcomatous components | Location of MET exon 14Δ | MET IHC | MET amplification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 78 | Yes | T3N0M IIB |

Spindle cell carcinoma | / | Spindle cells | c. 3028A > G | Negative | Negative |

| 2 | Male | 59 | Yes | T2N2M0 IIIA |

Pleomorphic carcinoma | Adenocarcinoma | Spindle cells + giant cells | c. 3028G > T | Positive (2+) | Negative |

| 3 | Male | 54 | Yes | T2N1M0 IIB |

Carcinosarcoma | Adenosquamous carcinoma | Undifferentiated sarcoma | c. 3028G > C | Negative | Negative |

| 4 | Male | 66 | No | T2N0M0 IB |

Pleomorphic carcinoma | Large cell carcinoma | Spindle cells | c. 3028 + 1G > T | Negative | Negative |

| 5 | Male | 51 | Yes | T2N0M0 IB |

Spindle cell carcinoma | / | Spindle cells | c. 3028 + 2_3028 + 4 del | Positive (2+) | Negative |

| 6 | Female | 66 | No | T2N0M0 IB |

Pleomorphic carcinoma | Squamous carcinoma | Spindle cells | c. 3028 + 3A > G | Negative | Negative |

| 7 | Female | 66 | No | T2N2M0 IIIA |

Pleomorphic carcinoma | Adenocarcinoma | Spindle cells | c. 3028 + 2_3028 + 4 del | Negative | Negative |

| 8 | Female | 61 | No | T2N2M0 IIIA |

Pleomorphic carcinoma | Adenocarcinoma | Spindle cells | c. 2888-21_2888-12 del | Positive (3+) | Negative |

| 9 | Male | 62 | Yes | T2N0M0 IB |

Pleomorphic carcinoma | Adenocarcinoma | Spindle cells + giant cells | c. 2888-23_2888 + 5 del | Positive (2+) | Positive |

Abbreviations: IHC, immunohistochemistry; MET, MNN HOS transforming gene; MET exon 14Δ, MET exon 14 mutation; PSCs, pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinomas.

Fig. 1.

Identification of MET exon 14 skipping mutations in PSCs. (A) Schematic diagram showing genomic positions of MET mutations that cause MET exon 14 skipping in 9 PSCs patients. Deletions are shown as rectangles, and point mutation is shown as triangles. The figure to the right indicates the patient number and the nucleotide position of each mutation, (B) representative sequencing histograms of MET exon 14 skipping mutation and wild type. (Abbreviations: MET, MNN HOS transforming gene; PSCs, pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinomas.)

MET FISH and IHC in PSCs

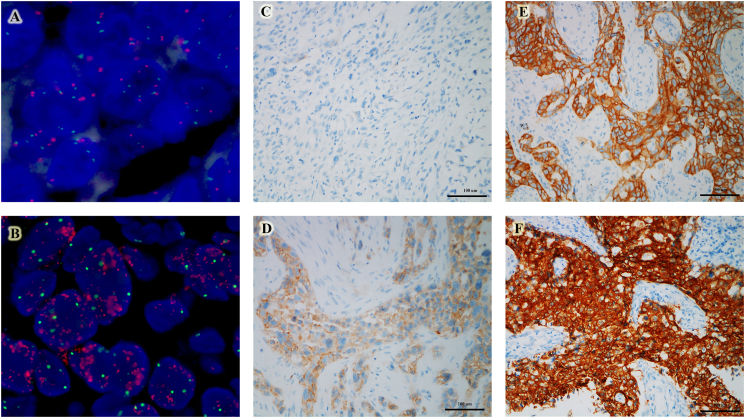

MET amplification by FISH was found in six (4.8%) patients, including one MET gene copy number was 10, and five MET/CEP7 ratio greater than 2 (Fig. 2A and B). MET protein overexpression by IHC was identified in 25 (20.2%) patients (Fig. 2C–F). The detailed clinical and pathological characteristics are described in Supplemental Table 1. No significant difference was found among ages, gender, smoking status, histological subtypes, and pathologic stage between patients with or without MET amplification and IHC overexpression.

Fig. 2.

MET amplification and protein expression in PSCs. (A) negative amplification, (B) amplification, (C) IHC score 0, (D) IHC score 1, (E) IHC score 2, (F) IHC score 3. (Abbreviations: IHC, immunohistochemistry; MET, MNN HOS transforming gene; PSCs, pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinomas.)

Correlation among MET exon 14Δ, MET FISH and MET IHC

There was a good correlation between MET FISH and MET IHC (P < 0.001, Table 3). Of note, all MET amplification patients had concurrent protein overexpression. Concordant results were seen in 105 (84.7%) cases, with positive IHC/MET amplification in six cases and negative IHC/negative amplification in 99 cases. However, no relationship was found between MET exon 14Δ and overexpression (P = 0.080) or amplification (P = 0.370).

Table 3.

Correlation among MET IHC, MET amplification and MET exon 14Δ in PSCs.

| Variations |

MET IHC |

P |

MET amplification |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive (n = 25) | Negative (n = 99) | Positive (n = 6) | Negative (n = 118) | |||

| MET exon 14Δ | 0.080 | 0.370 | ||||

| Positive (n = 9) | 4 | 5 | 1 | 8 | ||

| Negative (n = 115) | 21 | 94 | 5 | 110 | ||

| MET amplification | <0.001 | |||||

| Positive (n = 6) | 6 | 0 | / | / | ||

| Negative (n = 118) | 19 | 99 | / | / | ||

| MET IHC | <0.001 | |||||

| Positive (n = 25) | / | / | 6 | 19 | ||

| Negative (n = 99) | / | / | 0 | 99 | ||

Abbreviations: FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; MET, MNN HOS transforming gene; MET exon 14Δ, MET exon 14 mutation; IHC, immunohistochemistry; PSCs, pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinomas.

Survival analysis

After the exclusion of 25 patients (20.1%) who were lost to follow-up, a total of 99 patients eventually entered into the survival analysis. The median follow-up time was 83.0 months (interquartile range, 18.8 to 58.2). The mOS was 13.9 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 9.65 to 18.2). Univariable analysis revealed that pathologic stage (P = 0.009) and MET amplification (P = 0.019) were associated with a shorter mOS (Table 4). Representative Kaplan-Meier curves showing the mOS were shown in Fig. 3A and B. Multivariable analysis demonstrated that pathologic stage (hazard ratio [HR], 2.77; 95% CI, 1.283–6.011; P = 0.010) and MET amplification (HR, 4.71; 95% CI, 1.307–16.975; P = 0.018) were independent prognostic factors (Table 4).

Table 4.

Univariable and Multivariable OS Analysis in Patients with PSCs (n = 124).

| Parameter | Univariable analysis |

Multivariable analysis |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% Cl | P | HR | 95% Cl | P | |

| Age (<65 vs. >65) | 1.361 | 0.854–2.170 | 0.195 | 1.436 | 0.859–2.403 | 0.168 |

| Gender (male vs. female) | 1.078 | 0.569–2.043 | 0.819 | 1.002 | 0.447–2.242 | 0.997 |

| Smoking status (yes vs. no) | 1.200 | 0.749–1.924 | 0.448 | 1.377 | 0.761–2.943 | 0.291 |

| Pathologic stage (IIIB–IV vs. I–IIIA) | 2.587 | 1.227–5.455 | 0.013 | 2.777 | 1.283–6.011 | 0.010 |

| Pleomorphic carcinoma (yes vs. no) | 1.072 | 0.645–1.781 | 0.788 | 1.097 | 0.630–1.991 | 0.742 |

| MET exon 14Δ (positive vs. negative) | 1.385 | 0.599–3.201 | 0.446 | 1.077 | 0.413–2.806 | 0.880 |

| MET amplification (positive vs. negative) | 3.181 | 1.139–8.881 | 0.027 | 4.710 | 1.307–16.975 | 0.018 |

| MET IHC (positive vs. negative) | 1.263 | 0.727–2.192 | 0.408 | 1.001 | 0.533–1.897 | 0.998 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival; MET, MNN HOS transforming gene; MET exon 14Δ, MET exon 14 mutation; IHC, immunohistochemistry; PSCs, pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinomas.

Fig. 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve for overall survival in PSCs. (A) MET amplification, (B) pathologic stage. (Abbreviations: MET, MNN HOS transforming gene; mOS, median overall survival; PSCs, pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinomas.)

Discussion

MET abnormalities including MET exon 14Δ and amplification have been identified as targetable alterations in NSCLC. Though rare, MET gene alterations have been attracting considerable attention in PSCs, especially for MET exon 14Δ, demonstrating a higher frequency than other subtypes of NSCLC [25]. However, through a careful review of the past literature, we found that the frequency of MET exon 14Δin PSCs varies greatly, and most studies were conducted in Caucasian populations, and data from Asian is scanty. On these grounds, we describe the largest, to the best of our knowledge, multi-institutional study to assess the prevalence of MET alterations and the correlation among MET exon 14Δ, amplification, and overexpression in Chinese PSCs.

Huge discrepancies existed in the frequency of MET exon 14Δamong previous studies in PSCs, ranging from 4.9% to 31.8% [25,26]. In our study, the incidence of MET exon 14Δ was 7.3%, which was consistent with recently reported data of 7.7% (8/104) by Schrock et al. and 6.2% (5/81) by Mignard et al. [30,31]. Nevertheless, other studies have reported a higher frequency of more than 20% [25,32]. These discrepancies can be explained by the following reasons. On one hand, most previous investigations were based on a limited number of PSCs. Tong et al. and Awad et al. reported a high incidence rate of 31.8% with 22 PSCs samples and 26.6% with 15 PSCs samples, respectively [32,33]. Besides, Liu et al. and Kwon et al. also reported frequencies of 22% with 36 PSCs patients and 20% with 45 PSCs patients [25,34]. Future larger sample size studies remain urgently needed to identify a more accurate frequency of MET exon 14Δ, especially for PSCs patients with different races and tumor stages. On the other hand, different detection methods may also influence the incidence of MET exon 14Δ. Previous MET exon 14Δhas been detected by next-generation sequencing (NGS), sanger sequencing, qRT-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), and whole-exome sequencing (WES).

Up to now, the frequency of MET amplification and overexpression in PSCs has rarely been reported, and most studies were focused on the common types of NSCLC (Supplemental Table S2). In our study, MET amplification was detected in six (4.8%) patients, and the frequency was lower than that reported by Mignard et al. (8.5%) and Tong et al. (13.6%) [31,32]. The variations could be attributed to the sample size and the different methodologies used in each study. Besides, MET protein overexpression was found in 25 (20.2%) PSCs, which was far higher than MET DNA alterations, and the result was also frequently observed in studies with NSCLC.

The relationship between MET overexpression and MET DNA alterations remains controversial in PSCs. Our results demonstrated a good correlation between MET amplification and overexpression, all cases with MET amplification presented a strong overexpression. However, there was a negative predictive value between MET exon 14Δ and overexpression or amplification. The results were partially different from a recent study by Mignard and colleagues [31]. They found that MET IHC could not be considered as a screening test either for MET amplification or MET exon 14Δin PSCs. However, some studies demonstrated a good correlation between MET IHC and MET amplification in NSCLC [34,35]. Interestingly, Awad et al. reported a study presented a phenomenon that stage IV MET exon 14ΔNSCLCs were significantly more likely to have concurrent MET amplification and strong MET protein expression, suggesting that MET genomic alterations and MET protein expression may be correlated with advanced stage [33]. Of note, patients with MET exon 14Δ and MET amplification in our study were all detected in stage I-IIIA. This may explain why we did not find any correlation among MET exon 14Δ, amplification and overexpression. As we all know, various factors could affect the results, standardized clinical trials are urgently needed to evaluate the relationship between MET genetic alterations and protein expression.

Many studies have shown that the clinicopathological features of NSCLC patients with MET exon 14Δwere older age (more than 70 years) [33,36,37]. While our study found that the median age of MET exon 14Δ patients was 62 years (range, 51 to 78 years), which was consistent with the study reported by Si-yang Liu and colleagues [38]. The study also showed that the MET exon 14Δoccurs at a young median age, 59 years old (range, 45 to 77 years) in 12 Chinese NSCLC patients, similar to ALK and ROS1 rearrangements. These discrepancies may be related to ethnical differences.

Furthermore, we provided a survival analysis of MET genetic alterations and protein expression in Chinese PSCs. In this cohort of surgically resected PSCs without MET TKI treatment, only MET amplification suffered a much shorter mOS, while MET exon 14Δor overexpression may not affect patient survival. Previous studies have evaluated the prognostic value of MET DNA alterations and protein expression based on NSCLC patients and the results remain uncertain [39]. However, we should notice that the small numbers of cases with MET exon 14Δ, amplification, and overexpression in our studies. Further large prospective studies are needed to elucidate this puzzle.

The present study has several limitations. One, due to the limited number of analyzed samples, we cannot detect the frequencies of other driver mutations, such as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) and ROS proto-oncogene 1, receptor tyrosine kinase (ROS-1). Two, data on when the disease recurrence or disease progression were unavailable in most patients (79/124, 63.7%), so that we cannot evaluate the relationship between MET alterations and the subsequent treatment response.

Conclusion

In summary, our study showed that 7.3% of PSCs patients harboring MET exon 14Δ, and widespread screening for MET exon 14Δin PSCs should be encouraged. Besides, the selection of tumors with MET amplification using IHC is effective. However, MET exon 14Δis difficult to identify by IHC or amplification results.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and the academic committee of Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Center (B2020-139-01), and exception to the requirement of informed consent was approved.

Funding sources

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81572270), Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (2017JJ3188) and Foundation of Hunan Health Committee Research Plan (A2017005).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Xue-wen Liu: Conceptualization, Writing - original draft, Funding acquisition;

Xin-ru Chen: Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Visualization, Validation;

Yu-ming Rong: Formal analysis, Writing - original draft;

Lyu Ning: Methodology, Software, Writing - original draft;

Chun-wei Xu, Fang Wang, Fang Wang, Wen-yong Sun, San-gao Fang, Jing-ping Yuan, Hui-juan Wang, Wen-xian Wang, Wen-bin Huang, Jian-ping Xu, Zhen-ying Yue: Resources, Writing - original draft;

Li-kun Chen: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing - review & editing, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranon.2020.100868.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary tables

References

- 1.Venissac N., Pop D., Lassalle S., Berthier F., Hofman P., Mouroux J. Sarcomatoid lung cancer (spindle/giant cells): an aggressive disease? J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2007;134(3):619–623. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yendamuri S., Caty L., Pine M., Adem S., Bogner P., Miller A., Demmy T.L., Groman A., Reid M. Outcomes of sarcomatoid carcinoma of the lung: a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Database analysis. Surgery. 2012;152(3):397–402. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Terzi A., Gorla A., Piubello Q., Tomezzoli A., Furlan G. Biphasic sarcomatoid carcinoma of the lung: report of 5 cases and review of the literature. European journal of surgical oncology: the journal of the European Society of Surgical Oncology and the British Association of Surgical Oncology. 1997;23(5):457. doi: 10.1016/s0748-7983(97)93733-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Travis W.D., Brambilla E., Nicholson A.G., Yatabe Y., Austin J.H., Beasley M.B., Chirieac L.R., Dacic S., Duhig E., Flieder D.B. The 2015 World Health Organization classification of lung tumors: impact of genetic, clinical and radiologic advances since the 2004 classification. Journal of thoracic oncology: official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2015;10(9):1243–1260. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bae H.M., Min H.S., Lee S.H., Kim D.W., Chung D.H., Lee J.S., Kim Y.W., Heo D.S. Palliative chemotherapy for pulmonary pleomorphic carcinoma. Lung cancer (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 2007;58(1):112–115. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lococo F., Luppi F., Cerri S., Montanari G., Stefani A., Rossi G. Pulmonary carcinosarcoma arising in the framework of an idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Lung. 2016;194(1):171–173. doi: 10.1007/s00408-015-9818-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sokucu S.N., Kocaturk C., Urer N., Sonmezoglu Y., Dalar L., Karasulu L., Altin S., Bedirhan M.A. Evaluation of six patients with pulmonary carcinosarcoma with a literature review. TheScientificWorldJournal. 2012;2012:167317. doi: 10.1100/2012/167317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Y. The human hepatocyte growth factor receptor gene: complete structural organization and promoter characterization. Gene. 1998;215(1):159–169. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00264-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maulik G., Shrikhande A., Kijima T., Ma P.C., Morrison P.T., Salgia R. Role of the hepatocyte growth factor receptor, c-Met, in oncogenesis and potential for therapeutic inhibition. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2002;13(1):41–59. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(01)00029-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Birchmeier C., Birchmeier W., Gherardi E., Vande Woude G.F. Met, metastasis, motility and more. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;4(12):915–925. doi: 10.1038/nrm1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peruzzi B., Bottaro D.P. Targeting the c-Met signaling pathway in cancer. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2006;12(12):3657–3660. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu Y.L., Zhang L., Kim D.W., Liu X., Lee D.H., Yang J.C., Ahn M.J., Vansteenkiste J.F., Su W.C., Felip E. Phase Ib/II study of capmatinib (INC280) plus gefitinib after failure of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitor therapy in patients with EGFR-mutated, MET factor-dysregulated non-small-cell lung cancer. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2018;36(31):3101–3109. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.77.7326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsuta K., Kozu Y., Mimae T., Yoshida A., Kohno T., Sekine I., Tamura T., Asamura H., Furuta K., Tsuda H. c-MET/phospho-MET protein expression and MET gene copy number in non-small cell lung carcinomas. Journal of thoracic oncology: official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2012;7(2):331–339. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318241655f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bean J., Brennan C., Shih J.Y., Riely G., Viale A., Wang L., Chitale D., Motoi N., Szoke J., Broderick S. MET amplification occurs with or without T790M mutations in EGFR mutant lung tumors with acquired resistance to gefitinib or erlotinib. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104(52):20932–20937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710370104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drilon A., Cappuzzo F., Ou S.I., Camidge D.R. Targeting MET in lung cancer: will expectations finally be MET? Journal of thoracic oncology: official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2017;12(1):15–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galleges Ruiz M.I., Floor K., Steinberg S.M., Grünberg K., Thunnissen F.B., Belien J.A., Meijer G.A., Peters G.J., Smit E.F., Rodriguez J.A. Combined assessment of EGFR pathway-related molecular markers and prognosis of NSCLC patients. Br. J. Cancer. 2009;100(1):145–152. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Onitsuka T., Uramoto H., Ono K., Takenoyama M., Hanagiri T., Oyama T., Izumi H., Kohno K., Yasumoto K. Comprehensive molecular analyses of lung adenocarcinoma with regard to the epidermal growth factor receptor, K-ras, MET, and hepatocyte growth factor status. Journal of thoracic oncology: official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2010;5(5):591–596. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181d0a4db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tokunou M., Niki T., Eguchi K., Iba S., Tsuda H., Yamada T., Matsuno Y., Kondo H., Saitoh Y., Imamura H. c-MET expression in myofibroblasts: role in autocrine activation and prognostic significance in lung adenocarcinoma. Am. J. Pathol. 2001;158(4):1451–1463. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64096-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park S., Choi Y.L., Sung C.O., An J., Seo J., Ahn M.J., Ahn J.S., Park K., Shin Y.K., Erkin O.C. High MET copy number and MET overexpression: poor outcome in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Histol. Histopathol. 2012;27(2):197–207. doi: 10.14670/HH-27.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pyo J.S., Kang G., Cho W.J., Choi S.B. Clinicopathological significance and concordance analysis of c-MET immunohistochemistry in non-small cell lung cancers: a meta-analysis. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2016;212(8):710–716. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2016.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reungwetwattana T., Liang Y., Zhu V., Ou S.I. The race to target MET exon 14 skipping alterations in non-small cell lung cancer: the why, the how, the who, the unknown, and the inevitable. Lung cancer (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 2017;103:27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2016.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paik P.K., Felip E., Veillon R., Sakai H., Cortot A.B., Garassino M.C., Mazieres J., Viteri S., Senellart H., Van Meerbeeck J. Tepotinib in non-small-cell lung cancer with MET exon 14 skipping mutations. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383(10):931–943. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2004407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drilon A., Clark J.W., Weiss J., Ou S.I., Camidge D.R., Solomon B.J., Otterson G.A., Villaruz L.C., Riely G.J., Heist R.S. Antitumor activity of crizotinib in lung cancers harboring a MET exon 14 alteration. Nat. Med. 2020;26(1):47–51. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0716-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dhillon S. Capmatinib: first approval. Drugs. 2020;80(11):1125–1131. doi: 10.1007/s40265-020-01347-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu X., Jia Y., Stoopler M.B., Shen Y., Cheng H., Chen J., Mansukhani M., Koul S., Halmos B., Borczuk A.C. Next-generation sequencing of pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma reveals high frequency of actionable MET gene mutations. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2016;34(8):794–802. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.0674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saffroy R., Fallet V., Girard N., Mazieres J., Sibilot D.M., Lantuejoul S., Rouquette I., Thivolet-Bejui F., Vieira T., Antoine M. MET exon 14 mutations as targets in routine molecular analysis of primary sarcomatoid carcinoma of the lung. Oncotarget. 2017;8(26):42428–42437. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noonan S.A., Berry L., Lu X., Gao D., Barón A.E., Chesnut P., Sheren J., Aisner D.L., Merrick D., Doebele R.C. Identifying the appropriate FISH criteria for defining MET copy number-driven lung adenocarcinoma through oncogene overlap analysis. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2016;11(8):1293–1304. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cappuzzo F., Marchetti A., Skokan M., Rossi E., Gajapathy S., Felicioni L., Del Grammastro M., Sciarrotta M.G., Buttitta F., Incarbone M. Increased MET gene copy number negatively affects survival of surgically resected non-small-cell lung cancer patients. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27(10):1667–1674. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spigel D.R., Edelman M.J., O'Byrne K., Paz-Ares L., Mocci S., Phan S., Shames D.S., Smith D., Yu W., Paton V.E. Results from the phase III randomized trial of onartuzumab plus erlotinib versus erlotinib in previously treated stage IIIB or IV non-small-cell lung cancer: METLung. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2017;35(4):412–420. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.69.2160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schrock A.B., Li S.D., Frampton G.M., Suh J., Braun E., Mehra R., Buck S., Bufill J.A., Peled N., Karim N.A. Pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinomas commonly harbor either potentially targetable genomic alterations or high tumor mutational burden as observed by comprehensive genomic profiling. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2017;12(6):932–942. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mignard X., Ruppert A.M., Antoine M., Vasseur J., Girard N., Mazieres J., Moro-Sibilot D., Fallet V., Rabbe N., Thivolet-Bejui F. c-MET overexpression as a poor predictor of MET amplification or exon 14 mutation in lung sarcomatoid carcinoma. Journal of thoracic oncology: official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2018;13(12):1962–1967. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tong J.H., Yeung S.F., Chan A.W., Chung L.Y., Chau S.L., Lung R.W., Tong C.Y., Chow C., Tin E.K., Yu Y.H. MET amplification and exon 14 splice site mutation define unique molecular subgroups of non-small cell lung carcinoma with poor prognosis. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2016;22(12):3048–3056. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Awad M.M., Oxnard G.R., Jackman D.M., Savukoski D.O., Hall D., Shivdasani P., Heng J.C., Dahlberg S.E., Janne P.A., Verma S. MET exon 14 mutations in non-small-cell lung cancer are associated with advanced age and stage-dependent MET genomic amplification and c-met overexpression. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2016;34(7):721–730. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.4600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kwon D., Koh J., Kim S., Go H., Kim Y.A., Keam B., Kim T.M., Kim D.W., Jeon Y.K., Chung D.H. MET exon 14 skipping mutation in triple-negative pulmonary adenocarcinomas and pleomorphic carcinomas: an analysis of intratumoral MET status heterogeneity and clinicopathological characteristics. Lung cancer (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 2017;106:131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2017.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li Y., Gao L., Ma D., Qiu T., Li W., Li W., Guo L., Xing P., Liu B., Deng L. Identification of MET exon14 skipping by targeted DNA- and RNA-based next-generation sequencing in pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinomas. Lung cancer (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 2018;122:113–119. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frampton G.M., Ali S.M., Rosenzweig M., Chmielecki J., Lu X., Bauer T.M., Akimov M., Bufill J.A., Lee C., Jentz D. Activation of MET via diverse exon 14 splicing alterations occurs in multiple tumor types and confers clinical sensitivity to MET inhibitors. Cancer discovery. 2015;5(8):850–859. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee G.D., Lee S.E., Oh D.Y., Yu D.B., Jeong H.M., Kim J., Hong S., Jung H.S., Oh E., Song J.Y. MET exon 14 skipping mutations in lung adenocarcinoma: clinicopathologic implications and prognostic values. Journal of thoracic oncology: official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2017;12(8):1233–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu S.Y., Gou L.Y., Li A.N., Lou N.N., Gao H.F., Su J., Yang J.J., Zhang X.C., Shao Y., Dong Z.Y. The unique characteristics of MET exon 14 mutation in Chinese patients with NSCLC. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2016;11(9):1503–1510. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park S., Koh J., Kim D.W., Kim M., Keam B., Kim T.M., Jeon Y.K., Chung D.H., Heo D.S. MET amplification, protein expression, and mutations in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Lung cancer (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 2015;90(3):381–387. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary tables