Abstract

Purpose of Review

Placental malaria is the primary mechanism through which malaria in pregnancy causes adverse perinatal outcomes. This review summarizes recent work on the significance, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and prevention of placental malaria.

Recent Findings

Placental malaria, characterized by the accumulation of Plasmodium-infected red blood cells in the placental intervillous space, leads to adverse perinatal outcomes such as stillbirth, low birth weight, preterm birth, and small-for-gestational-age neonates. Placental inflammatory responses may be primary drivers of these complications. Associated factors contributing to adverse outcomes include maternal gravidity, timing of perinatal infection, and parasite burden.

Summary

Placental malaria is an important cause of adverse birth outcomes in endemic regions. The main strategy to combat this is intermittent preventative treatment in pregnancy; however, increasing drug resistance threatens the efficacy of this approach. There are studies dissecting the inflammatory response to placental malaria, alternative preventative treatments, and in developing a vaccine for placental malaria.

Keywords: Placental malaria, Malaria in pregnancy, Pathogenesis of placental malaria, Prevention of placental malaria, Obstetrical outcomes of placental malaria, Plasmodium infection

Introduction

Malaria in pregnancy is an important global health issue. The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that 11 million pregnancies in sub-Saharan Africa were at risk of malaria in 2018 alone [1]. During pregnancy, the burden of adverse obstetrical and neonatal outcomes occurs as a result of placental malaria, when the parasite-infected red blood cells sequester in the intervillous spaces of the placenta. In endemic regions, placental malaria may be present in up to 63% of pregnant women, irrespective of malaria infection symptomatology [2–4].

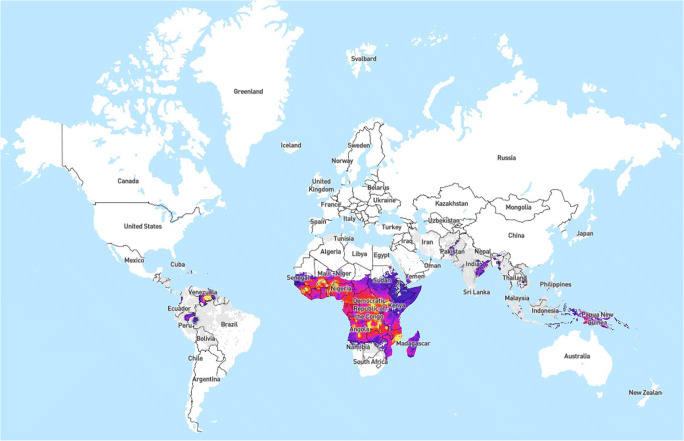

The global burden of malaria infection is primarily in low- and middle-income countries. The World Health Organization (WHO) reported in 2018 there were 228 million cases; 93% of cases occurred in Africa, followed by Southeast Asia (3.4%) and the Eastern Mediterranean Region (2.1%) [5]. Of note, sub-Saharan Africa and India carried 85% of all cases [5]. While cases in 2018 were lower than 2010 (251 million cases), the incidence rate has been relatively stable since 2014 at 57 cases per 1000 population at risk, demonstrating a slowing of the rate of change in addressing malaria infection [5](Fig. 1). Additionally, as the overall number of endemic regions decreases [5], studies are finding that malarial immunity in previously endemic regions are dropping, leading to more adverse pregnancy outcomes in women who become infected [6•, 7].

Fig. 1.

Global incidence of P. falciparum. Time-aware mosaic data set showing predicted all-age incidence rate (clinical cases per 1000 population per annum) of Plasmodium falciparum malaria for each year. Colors: one linear scale between rates of zero and 10 cases per 1000 (gray shades) and a second linear scale between 10 and 1000 (colors from purple to yellow). Malaria Atlas Project: WHO Collaborating Centre. Explorer Map - Plasmodium falciparum Incidence. No changes made to the map. Legend represented as is from map. Image located at: https://malariaatlas.org/explorer/#/. Available through open access via the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License accessible through: creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/. Disclaimer: Authors of this paper were not involved in the making of this map. This image was made through the Malaria Atlas Project. See open access attribution information above for details on accessing the map

Here, we review the recent literature on the pathogenesis, diagnosis, and outcomes from placental malaria, with a focus on human studies. We also discuss current concepts in treatment and strategies for prevention.

Pathogenesis

Malaria infection occurs due to the protozoan parasite Plasmodium which has five species that infect humans: P. falciparum, P. malariae, P. ovale, P. vivax, and P. knowlesi [1]. Of these, P. falciparum and P. vivax are the most prevalent [1, 5]. P. falciparum causes the highest rates of complications and mortality while P. vivax causes a less fatal but relapsing infection [1, 8–10].

Humans acquire the Plasmodium parasite via the bite of an infected Anopheles mosquito [11]. After the pre-erythrocytic liver stage, plasmodium parasites invade red blood cells (RBCs) and start to circulate in the bloodstream [12]. Differing from the other species, P. falciparum parasites express the P. falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1) receptor on infected RBC membranes [11]. During pregnancy, infected RBCs express a variant PfEMP1 receptor called VAR2CSA receptor that has an active Duffy-binding-like γ domain, which enables adherence and sequestration of infected RBCs in the intervillous spaces of the placenta [13, 14].

Placental malaria is thought to occur via Plasmodium avoidance of spleen clearance through expression of the VAR2CSA protein that binds to the chondroitin sulfate A (CSA) in the placental intervillous space [15, 16•]. Placental malaria is characterized by the accumulation of these infected RBCs in the intervillous space and subsequent infiltration of maternal monocytes/macrophages [17]. Prominent inflammatory infiltration by monocytes/macrophages causing massive chronic intervillositis is related to severe placental malaria [18]. Inflammatory response to placental malaria inhibits mTOR signaling which is key [19]. Intervillositis due to placental malaria was found to be associated with increased autophagosome formation but decreased autophagosome/lysosome fusion leading to autophagosome accumulation in syncytiotrophoblasts blocking placental amino acid uptake [20•]. In mothers with placental malaria, autophagy-related genes were downregulated leading to autophagy dysregulation and thereby impairment of transplacental amino acid transport [21]. Also, blockage of mTOR signaling due to placental malaria leads to decreased placental amino acid uptake [20•]. Recently, it was found that placental malaria stimulates placental expression of inflammasomes which are linked to placental secretion and maturation of IL-1β, a pro-inflammatory cytokine that causes diminished nutrient transporter expression [19]. Thus, during placental malaria, the usually anti-inflammatory placental environment evolves into a pro-inflammatory state. Gravidity is an important factor that alters fetal and maternal responses during placental malaria [22]. In primigravid women, proportion of anti-inflammatory maternal vs fetal macrophages showed opposite trends in the setting of placental malaria [23]. On the other hand, compared with primigravid women, multigravid women had higher levels of IL-27 and IL-28A that induce secretion of protective cytokines against malaria [24]. The influence of timing of infection changes according to gravidity, as primigravidas with early asymptomatic infection and contrarily multigravidas experiencing parasitemia later in pregnancy have higher rates of placental malaria [25]. Other than these, a study in Sudan proposed the carriage of female fetus as a novel risk factor for placental malaria [26].

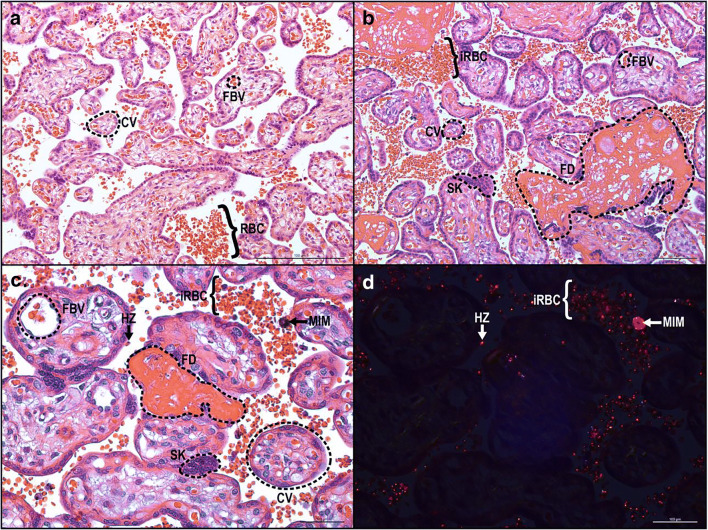

Increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, oxidative stress [27], and apoptosis lead to pathological changes in the placenta and poor pregnancy outcomes [28]. It has been shown that histopathological changes and placental malaria enhance the risk of preeclampsia in pregnant women, especially in primigravidas [29]. Histopathological changes during placental malaria include presence of hemozoin, perivillous fibrin deposition [30, 31], syncytial knot formation [32], and decrease in villous surface area (Fig. 2). These pathologic alterations in the placenta may limit exchange of nutrients between mother and fetus, increasing risk for fetal growth restriction and low birth weight babies [16•, 33]. Placental malaria decreases the abundance of megalin and DAB2 in syncytiotrophoblasts, which may be associated with low birth weight [34]. In Papua, increased placental mitochondrial DNA copy number demonstrated a relationship with reduced birth weight [35]. Malaria infection during early pregnancy leads to alterations in the vascular structure of the placenta, such as decrease of transport villi volume and increase of diffusion distance and diffusion vessel surface, which influence birth weight and gestational length [36]. Even so, Plasmodium infection mid-pregnancy has been linked increased risk of preterm birth, possibly due to the changes in angiogenic, metabolic, and inflammatory states [37].

Fig. 2.

Histological cross section of chorionic villi. (a) Chorionic villi (CV) have a continuous layer of syncytiotrophoblasts separating fetal and maternal cells. Fetal blood vessels (FBV) are located within the CV whereas maternal red blood cells (RBC) are circulating in the intervillous space (IVS). (b) During placental malaria, infected red blood cells (iRBC) accumulate within the IVS and lead to fibrin deposition (FD) and syncytial knot (SK) formation. Normal light (c) and polarized light (d) microscopy of malaria-infected placenta demonstrating hemozoin (HZ), dark-brown pigment in normal light and red in polarized light, accumulation within iRBC, and maternal intervillous monocyte (MIM)

Risk Factors

In endemic regions, infection is more common in younger women and in primigravidas or secundigravidas compared with women who have been pregnant more than twice [1, 4, 38–40] with primigravidas having nearly three times the risk of placental malaria as multigravidas [41]. This is thought to occur because VAR2CSA is functionally and antigenically distinct from all other PfEMP1 types, so that a woman is unlikely to have acquired protective immunity to prior to the first pregnancy [42]. A significant mediator of reduced risk in later pregnancies is through the development of antibodies against VAR2CSA [43, 44]. However, in regions with low transmission rates, all pregnancies are at increased risk of for placental malaria given the lower immunity within the population [7].

Maternal HIV infection increases susceptibility to and severity of placental malaria by impairing antibody development to variant surface antigens expressed by malaria-infected erythrocytes, dysregulating cytokine production, and reducing protective interferon-gamma (IFN-g) responses [45]. A systematic review found that malaria incidence is decreased in the setting of antiretroviral treatments, particularly protease inhibitors [4]. However, a recent randomized controlled trial tested this hypothesis in HIV-positive pregnant woman and found no decrease in placental malaria with the protease inhibitor compared with the non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors [46]. Therefore, antiretrovirals may not play a protective role in placental malaria infection.

Additional risk factors for placental malaria include low maternal socioeconomic status and antenatal stress and mental health disorders. Low socioeconomic status is associated with poor-quality housing, making it easier for mosquitos to enter, inability to afford protective insecticide-treated bed nets, and lack of access to antimalarials and malaria preventative tools [4, 5]. Even after controlling for malaria prevention medications, poverty has been shown to have an independent association with malaria infection [41]. Additionally, women in low- and middle-income countries where poverty is rampant also have higher rates of antenatal depression [47]. Antenatal depression is significantly associated with bed net non-use during pregnancy [48]. The impact of antenatal stress and mental health and how that interacts with the social and economic stressors women in low- and middle-income countries endure are critical factors to addressing malaria in pregnancy as a whole and placental malaria specifically.

Obstetrical Outcomes

Placental malaria is thought to be the mechanism through which malaria exerts its poor obstetrical outcomes. These negative effects occur through the disruption of the maternal-fetal nutrient exchange and the inflammatory response in the placenta as detailed above. Recent studies of pregnant women with and without placental malaria demonstrated that placental malaria had a significant association with low birth weight (< 2500 g) (relative risk (RR) 3.45, 95% CI 1.44–8.23, p = 0.005; adjusted relative risk (aRR) 3.42, p = 0.02), preterm birth (RR 7.52, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.72–32.8, p = 0.007), small for gestational age (RR 2.30, 95% CI 1.10–4.80, p = 0.03; aRR 4.24, p < 0.001), stillbirth (odds ratio (OR) 1.95, 95% CI 1.48–2.57), and higher rates maternal anemia (aOR 2.22, 95% CI 1.02–4.84; p = 0.045) [16•, 49•, 50•, 51•], confirming that the pathological process occurring in the placenta is the likely source of these adverse obstetrical outcomes (Table 1). Longitudinal studies of malaria during pregnancy suggest that the total number of infections over pregnancy, and the parasitemia burden (measured by quantitative PCR), have the greatest association with placental malaria [25, 52]. The impact on timing of infections during pregnancy on the development of placental malaria is dependent on maternal gravidity, with earlier infections having a greater impact in primigravidas compared with later infections in multigravidas [25].

Table 1.

Obstetrical outcomes associated with placental malaria

| Outcome | Relative risk (RR) (95% CI; p value) | |

|---|---|---|

| Preterm birth | RR 7.52 (1.72–32.8, p = 0.007) | |

| Low birth weight | RR 3.45, 95% CI 1.44–8.23, p = 0.005 | #aRR 3.42; p 0.02 |

| Small for gestational age | RR 2.30, 95% CI 1.10–4.80, p = 0.03 | #aRR 4.24, p < 0.001 |

| Maternal anemia | *aOR 2.22, 95% CI 1.02–4.84; p = 0.045 | |

| Stillbirth | +OR 1.95, 95% CI 1.48–2.57 | |

The low birth weight associated with placental malaria is a significant global public health concern. Neonates and infants with low birth weight have increased risk of death in the first year of life [53] with 200,000 infant deaths a year as a result of maternal malaria [54]. Additionally, these infants are at increased risk for poor developmental outcomes through childhood and beyond [55]. This is of major concern as low birth weight is a placental malaria outcome that remains persistent in areas with low malaria transmission rates and is predicted to increase as malaria endemicity decreases globally [7, 55].

The higher rates of maternal anemia with placental malaria tend to be more severe, with hemoglobin < 7 [40]. Severe anemia during pregnancy not only increases the risk of low birth weight infants but also increases the risk of death from postpartum hemorrhage, a common obstetrical complication independent of malaria [1, 39, 40]. This again highlights the important and devastating impact of placental malaria on pregnant women.

Over 200,000 stillbirths in sub-Saharan Africa are attributed to malarial infection, making malaria one of the most preventable infectious causes of stillbirth worldwide [3, 51, 56]. Acute or chronic placental malaria infection is associated with a 2-fold increase in stillbirth risk [3] and is thought to be the link between malarial infection and stillbirth. This association between malarial infection and stillbirth was two times higher in low-to-intermediate endemicity areas than in areas of high endemicity [51•], further highlighting the complex relationship between decreasing malaria transmission rates and pregnancy outcomes.

Malaria in infancy and congenital malaria as a result of placental malaria has been actively evaluated. One study demonstrated that children born to mothers with placental malaria had a significantly higher odds of clinical malaria (OR, 4.1; 95% CI, 1.3–13.1) in the first year of life [54]. Another study found that clinical malaria episodes occurred earlier in children born to women with placental malaria than women with no placental malaria [57]. Congenital malaria, while rare, has been associated with placental malaria. A recent study demonstrated significant increased odds of this outcome in neonates born to women with placental malaria [58]. Yet, a systematic review of 14 studies found that there was insufficient evidence to confirm or exclude the causal association between malaria in pregnancy and malaria in infancy. Additionally, there is not clear evidence of vertical transmission [40, 59] and the outcome of congenital malaria is rare, making it a challenge to study.

Diagnosis and Management

Diagnosis of Placental Malaria

Placental malaria is difficult to diagnose during pregnancy. Peripheral blood smear, the classic diagnostic tool during clinical practice, is usually negative because parasitized RBCs sequester in the placenta. However, even submicroscopic peripheral infection or parasitemia before 3rd trimester is still a risk factor for developing placental malaria [60]. Rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) are successfully used to diagnose non-pregnant individuals with malaria; however, this technique is less efficient for the diagnosis of placental malaria. A newer version of RDT called highly sensitive rapid diagnostic test (HS-RDT) had higher sensitivity compared with light microscopy and conventional RDTs in placental blood samples when nested PCR was used as reference test [61]. Even though PCR is a more reliable technique for placental malaria diagnosis, it is inconvenient to use in primary care facilities and largely unavailable in low resource settings. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) is an alternative nucleic acid amplification technique that can be used outside a reference laboratory for molecular detection of placental malaria by analyzing placental blood that is quick, easy, and as accurate as nested PCR [62]. Nonetheless, the gold standard for placental malaria diagnosis is via placental histology, although it cannot be applied during ongoing pregnancies. The pathological classification system has been first described by Bulmer et al. in 1993 [63], then further modified by Rogerson et al. [15] and named as Rogerson Criteria. They categorized the placentas into four groups: (1) active infection, (2) active-chronic infection, (3) past-chronic infection, (4) not infected (Table 2). Active infection is characterized by the presence of parasitized RBCs in the intervillous space, malaria pigment in RBCs, and monocytes in the intervillous space but no pigment in fibrin. If a pigment accumulation in fibrin/fibrin-containing cells/syncytiotrophoblasts/stroma accompanies the previous findings, then it is called active-chronic phase. Past-chronic infection is identified as malaria pigment confined to fibrin or cells within fibrin in the absence of parasites. Another novel histological grading scheme for placental malaria was proposed by Muehlenbachs et al. [64]. They separately quantified degree of inflammation and pigment deposition and calculated a score for each feature. Inflammation score is (I) for minimal inflammation, (II) for present inflammation, and (III) for massive intervillositis. Pigment deposition score is assessed by calculating the percentage of high-power fields that are positive for pigment in fibrin in intervillous spaces, excluding erythrocytes and monocytes. Pigment deposition score is (I) for ≤ 10%, (II) for 10–40%, and (III) for > 40% pigment deposition per high-power field. Despite these instructions, there are some challenges for histologic diagnosis. Due to improper fixation of placental tissue, unbuffered formalin pigment can accumulate and resemble malaria pigment, making it difficult to distinguish them from each other for a correct diagnosis [65], and fixation with buffered formalin preparation is important for accurate diagnosis by histopathology. Placental impression smear has been proposed as an easier and cheaper method compared with placental histology, and may be useful in settings where histopathology cannot be performed [66]. However, histopathology is likely to remain the gold standard for the most sensitive diagnosis of clinically relevant placental malaria [49•].

Table 2.

Rogerson criteria for histopathologic diagnosis of placental malaria

| Active infection | Active-chronic infection | Past-chronic infection | Not infected |

|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of parasitized RBCs in the intervillous space with malaria pigment in RBCs and monocytes in the intervillous space; no pigment in fibrin | Pigment accumulation in fibrin, fibrin-containing cells, syncytiotrophoblasts, stroma accompanies the previous findings | Malaria pigment confined to fibrin or cells within fibrin in the absence of parasites | Absence of parasite in placental RBCs without malaria pigment |

Data from Rogerson [15]

Treatment

Because placental malaria can only be diagnosed postpartum by assessing the placenta, treatment is primarily preventative. There are two main approaches to prevention in areas with active transmission: intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy (IPTp) and intermittent screening and treatment in pregnancy (ISTp). These two approaches are active areas of research given the ongoing changes in malaria endemicity and Plasmodium drug resistance.

In endemic regions, the WHO recommends IPTp with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) [5]. However, in sub-Saharan Africa, where the bulk of malarial infections occur, P. falciparum has developed sequential mutations in the dihydrofolate reductase (dhfr) and dihydropteroate synthase (dhps) genes, which confer resistance to pyrimethamine and sulfadoxine, respectively [55]. The efficacy of SP is lower in areas with high frequency of the quintuple mutant (triple dhfr mutation and double mutation at dhps) [55]. In regions where > 90% of parasites have the quintuple mutant, up to 40% of asymptomatic parasitemic women who receive SP for IPTp are parasitemic again by day 42, reflecting the failure of SP to clear existing P. falciparum infections and prevent new infection [67]. Additionally, the efficacy of SP is completely lost in the event of sextuple mutant (when an additional mutation in dhps is present) [55].

To combat the developing resistance, the WHO made recommendations for three or more doses of SP during pregnancy starting in the second trimester [5]. However, this method may not be effective in regions where resistance is rising, such as East Africa. Recently in Uganda, a randomized controlled trial compared SP with dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine (an artemisinin-based treatment [DP]) given for three doses or every 4 weeks. They found that the prevalence of moderate-to-high-grade pigment deposition was significantly higher in the SP group than the monthly DP group (55.6% vs. 20.6%, p = 0.003), and that the risk of any adverse birth outcome (low birth weight, preterm delivery, stillbirth, and spontaneous abortions) was significantly lower in the monthly DP (9.2%) than in the three-dose DP group (21.3%, p = 0.02) [68••]. A Kenyan trial demonstrated similar findings with IPTp with DP having significantly lower prevalence of malaria infection during pregnancy and at delivery when compared with those receiving IPTp with SP [69]. A population pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics model of the Ugandan trial found that the optimal dosing DP is 3 days of administration as a loading dose followed by either single daily or weekly dosage [70]. They found that lower amounts of medication were required with more frequent dosing, leading to less adverse side effects and increased time above target concentrations of DP leading to less placental malaria [70].

The efficacy and safety of DP has also been seen in West Africa. A trial that compared four artemisinin-based treatments (artemether–lumefantrine, amodiaquine–artesunate, mefloquine–artesunate, and dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine) in pregnant women in Burkina Faso, Ghana, Malawi, and Zambia with malaria infection had similar findings. They found that DP had the best efficacy, an acceptable safety profile, and the additional benefit of a longer post-treatment prophylactic effect, further supporting its suitability as chemoprophylaxis or chemoprevention agent for Africa and not just East Africa [71••].

ISTp, the intermittent screening for malaria during antenatal visits using a rapid diagnostic test and treating test-positive women with an effective antimalarial drug [72], has been studied as a potential alternative to IPTp both in areas of SP and areas of low transmission where IPTp is not a recommendation. The results have been unfavorable. On study in a low transmission setting found no additional benefit in placental malaria to ISTp in comparison with treating symptomatic patients [72]. Another study in an endemic region demonstrated that ISTp with DP when compared with IPTp with SP had higher levels of placental malaria and adverse obstetrical outcomes [67]. These findings highlight that in endemic regions, IPTp with SP is more effective, even in SP-resistant areas, than ISTp. Additionally, in low transmission regions, preventing placental malaria through ISTp may not be effective and alternative methods need to be evaluated.

Vaccination

P. falciparum–derived VAR2CSA receptor is the main molecule facilitating the binding of infected RBCs to CSA in the intervillous space. Formation of antibodies against VAR2CSA inhibits binding of infected RBCs to CSA, thereby preventing complications related to placental malaria [40]. VAR2CSA is a large and diverse protein that has six Duffy-binding-like (DBL) domains and four interdomain (ID) regions making it hard to produce an efficient vaccine. However, a certain region of this protein called as minimum binding domain (MBD) has been identified as the critical region sufficient for the induction of antibody response [73]. Two vaccines called PRIMVAC and PAMVAC have been developed based on the MBDs of 3D7 and FCR3 parasite lines respectively [74]. Antibodies generated by PRIMVAC recognized homologous and two heterologous strains but their ability to inhibit adhesion was not as successful in heterologous strains as it was in the homologous one [75]. Recently, a first-in-human, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose escalation trial conducted in both malaria naïve and P. falciparum–exposed non-pregnant women showed that PRIMVAC adjuvanted with either Alhydrogel or glucopyranosyl lipid adjuvant in stable emulsion (GLA-SE) had acceptable safety profiles and induced the production of functional antibodies against its homologous strain, however had limited cross reactivity against heterologous variants only if higher doses applied [76••]. Likewise, PAMVAC resulted in the production of inhibitory antibodies against its homologous strain [77]. Overall, we can say that both of these vaccines mainly function against their homologous parasites. Still, there is insufficient evidence in terms of protection from placental malaria and its adverse outcomes, and the vaccine-related antibody formation [78••]. Rather than protection, presence of antibodies has been linked to placental and peripheral infection [78••]. Another challenge for successful vaccine development is the presence of global genetic varieties of VAR2CSA, especially in African populations, leading to potential variation in vaccine efficiency [79]. Sequencing of MBD of VAR2CSA can be separated into four or five clades, including FCR3-like variant and 3D7-like variant which is linked to increased risk of low birth weight [79]. Notably, it was also shown that binding inhibition and opsonizing function of antibodies changes according to parasite variant and geographical location besides gravidity [80•].

Further Investigation

Since the exact pathogenesis and maternal and fetal immune response regarding placental malaria are still unclear, there are gaps in terms of prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of placental malaria. As mentioned before, diagnosis of placental malaria is very challenging. Accurate, cost-effective, and easily applicable tools for identification of placental malaria should be developed to decrease the burden of the disease on both mother and fetus. It is important that those tools aim to make the diagnosis before delivery without need of placental specimens, as pathologic changes occur during early pregnancy. For treatment, there needs to be further studies evaluating the optimal regimen for IPTp alternatives in regions with ongoing SP resistance and the development of standardized regimens in low transmission regions where placental malaria is still common. In terms of protection, the exact protective and functional mechanism of naturally acquired antibodies in pregnant women against placental malaria is not fully understood and requires advanced research. Although two preventive vaccines against P. falciparum for placental malaria (PRIMVAC and PAMVAC) are under development, they are not applied routinely yet. Further investigations regarding their safety and efficacy, also considering population dependent variances in protectivity, need to be conducted. Additionally, an interesting new area of research is the recently reviewed fetal in utero immune response against malaria, its effect during childhood, and differences based on sex [22, 30].

Funding

SLG is supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIAID K08AI141728).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on The Placenta, Tropical Diseases, and Pregnancies

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Arthurine K. Zakama and Nida Ozarslan contributed equally to this work.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

- 1.Zakama AK, Gaw SL. Malaria in pregnancy: what the obstetric provider in nonendemic areas needs to know. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2019;74:546–556. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0000000000000704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feleke DG, Adamu A, Gebreweld A, Tesfaye M, Demisiss W, Molla G. Asymptomatic malaria infection among pregnant women attending antenatal care in malaria endemic areas of North-Shoa, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Malar J. 2020;19:1–6. doi: 10.1186/s12936-020-3152-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ismail MR, Ordi J, Menendez C, Ventura PJ, Aponte JJ, Kahigwa E, Hirt R, Cardesa A, Alonso PL. Placental pathology in malaria: a histological, immunohistochemical, and quantitative study. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:85–93. doi: 10.1016/S0046-8177(00)80203-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawford HLS, Lee AC, Kumar S, Liley HG, Bora S. Establishing a conceptual framework of the impact of placental malaria on infant neurodevelopment. Int J Infect Dis. 2019;84:54–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2019.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO. World Malaria Report 2017. World Health Organization. 2017. 10.1071/EC12504.

- 6.• Mayor A, Bardají A, Macete E, Nhampossa T, Fonseca AM, González R, et al. Changing trends in P. falciparum burden, immunity, and disease in pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2015. 10.1056/NEJMoa1406459This study showed that as immunity decreases, adverse outcomes from malaria in pregnancy increased. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Odongo CO, Odida M, Wabinga H, Obua C, Byamugisha J. Burden of placental malaria among pregnant women who use or do not use intermittent preventive treatment at Mulago hospital, Kampala. Malar Res Treat. 2016;2016:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2016/1839795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mace KE, Arguin PM, Tan KR. Malaria surveillance - United States, 2015. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2018;67:1–28. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6707a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. Malaria. Int Travel Heal. 2016:1–23 Available: http://www.who.int/ith/ITH_chapter_7.pdf. Accessed 1 May 2020.

- 10.Cdc CFDC and P. Treatment of malaria ( guidelines for clinicians). Treat Malar (Guidelines Clin.). 2013:1–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66420-3.

- 11.Phillips MA, Burrows JN, Manyando C, Van Huijsduijnen RH, Van Voorhis WC, Wells TNC. Malaria. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2017;3. 10.1038/nrdp.2017.50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Ashley EA, Pyae Phyo A, Woodrow CJ. Malaria. Lancet. 2018;391:1608–1621. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30324-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wahlgren M, Goel S, Akhouri RR. Variant surface antigens of Plasmodium falciparum and their roles in severe malaria. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2017;15:479–491. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark RL. Genesis of placental sequestration in malaria and possible targets for drugs for placental malaria. Birth Defects Research. 2019;111:569–583. doi: 10.1002/bdr2.1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rogerson SJ, Hviid L, Taylor DW, Rogerson SJ, Hviid L, Duff PE, et al. Malaria in pregnancy : pathogenesis and immunity. Malaria in pregnancy : pathogenesis and immunity. 2007;3099:105–117. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kapisi J, Kakuru A, Jagannathan P, Muhindo MK, Natureeba P, Awori P, et al. Relationships between infection with Plasmodium falciparum during pregnancy, measures of placental malaria, and adverse birth outcomes NCT02163447 NCT. Malar J. 2017;16:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-2040-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDonald CR, Tran V, Kain KC. Complement activation in placental malaria. Front Microbiol. 2015;6. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Pehrson C, Salanti A, Theander TG, Nielsen MA. Pre-clinical and clinical development of the first placental malaria vaccine. Expert Review of Vaccines. 2017;16:613–624. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2017.1322512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reis AS, Barboza R, Murillo O, Barateiro A, Peixoto EPM, Lima FA, Gomes VM, Dombrowski JG, Leal VNC, Araujo F, Bandeira CL, Araujo RBD, Neres R, Souza RM, Costa FTM, Pontillo A, Bevilacqua E, Wrenger C, Wunderlich G, Palmisano G, Labriola L, Bortoluci KR, Penha-Gonçalves C, Gonçalves LA, Epiphanio S, Marinho CRF. Inflammasome activation and IL-1 signaling during placental malaria induce poor pregnancy outcomes. Sci Adv. 2020;6:eaax6346. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aax6346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.• Dimasuay KG, Gong L, Rosario F, McBryde E, Spelman T, Glazier J, et al. Impaired placental autophagy in placental malaria. PLoS One. 2017. 10.1371/journal.pone.0187291Placental malaria is associated with dysregulation of placental autophagy and this is possibly impairing placental amino acid transfer to the fetus. Therefore, this may be the underlying mechanism of low birth weight due to placental malaria, especially with intervillositis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Lima FA, Barateiro A, Dombrowski JG, de Souza RM, de Sousa CD, Murillo O, et al. Plasmodium falciparum infection dysregulates placental autophagy. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0226117. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feeney ME. The immune response to malaria in utero. Immunol Rev. 2020;293:216–229. doi: 10.1111/imr.12806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gaw SL, Hromatka BS, Ngeleza S, Buarpung S, Ozarslan N, Tshefu A, Fisher SJ. Differential activation of fetal Hofbauer cells in Primigravidas is associated with decreased birth weight in symptomatic placental malaria. Malar Res Treat. 2019;2019:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2019/1378174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Djontu JC, Siewe Siewe S, Mpeke Edene YD, Nana BC, Chomga Foko EV, Bigoga JD, Leke RFG, Megnekou R. Impact of placental Plasmodium falciparum malaria infection on the Cameroonian maternal and neonate’s plasma levels of some cytokines known to regulate T cells differentiation and function. Malar J. 2016;15:561. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1611-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tran EE, Cheeks ML, Kakuru A, Muhindo MK, Natureeba P, Nakalembe M, Ategeka J, Nayebare P, Kamya M, Havlir D, Feeney ME, Dorsey G, Gaw SL. The impact of gravidity, symptomatology and timing of infection on placental malaria. Malar J. 2020;19:227. doi: 10.1186/s12936-020-03297-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adam I, Salih MM, Mohmmed AA, Rayis DA, Elbashir MI. Pregnant women carrying female fetuses are at higher risk of placental malaria infection. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0182394. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Megnekou R, Djontu JC, Bigoga JD, Medou FM, Tenou S, Lissom A. Impact of placental Plasmodium falciparum malaria on the profile of some oxidative stress biomarkers in women living in Yaoundé, Cameroon. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0134633. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharma L, Shukla G. Placental malaria: a new insight into the pathophysiology. Frontiers in Medicine. 2017;4. 10.3389/fmed.2017.00117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Obiri D, Erskine IJ, Oduro D, Kusi KA, Amponsah J, Gyan BA, Adu-Bonsaffoh K, Ofori MF. Histopathological lesions and exposure to Plasmodium falciparum infections in the placenta increases the risk of preeclampsia among pregnant women. Sci Rep. 2020;10:8280. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-64736-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Odorizzi PM, Feeney ME. Impact of in utero exposure to malaria on fetal T cell immunity. Trends Mol Med. 2016;22:877–888. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Imamura T, Sugiyama T, Cuevas LE, Makunde R, Nakamura S. Expression of tissue factor, the clotting initiator, on macrophages in Plasmodium falciparum –infected placentas. J Infect Dis. 2002;186:436–440. doi: 10.1086/341507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ahenkorah J, Tetteh-Quarcoo PB, Nuamah MA, Kwansa-Bentum B, Nuamah HG, Hottor B, et al. The impact of Plasmodium infection on placental histomorphology: a stereological preliminary study. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2019;2019:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2019/2094560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kidima WB. Syncytiotrophoblast functions and fetal growth restriction during placental malaria: updates and implication for future interventions. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2015/451735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lybbert J, Gullingsrud J, Chesnokov O, Turyakira E, Dhorda M, Guerin PJ, et al. Abundance of megalin and Dab2 is reduced in syncytiotrophoblast during placental malaria, which may contribute to low birth weight. Sci Rep. 2016;6. 10.1038/srep24508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Oktavianthi S, Fauzi M, Trianty L, Trimarsanto H, Bowolaksono A, Noviyanti R, Malik SG. Placental mitochondrial DNA copy number is associated with reduced birth weight in women with placental malaria. Placenta. 2019;80:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2019.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moeller SL, Nyengaard JR, Larsen LG, Nielsen K, Bygbjerg IC, Msemo OA, Lusingu JPA, Minja DTR, Theander TG, Schmiegelow C. Malaria in early pregnancy and the development of the placental vasculature. J Infect Dis. 2020;220:1425–1434. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elphinstone RE, Weckman AM, McDonald CR, Tran V, Zhong K, Madanitsa M, et al. Early malaria infection, dysregulation of angiogenesis, metabolism and inflammation across pregnancy, and risk of preterm birth in Malawi: a cohort study. PLoS Med. 2019;16. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Omer SA, Idress HE, Adam I, Abdelrahim M, Noureldein AN, Abdelrazig AM, Elhassan MO, Sulaiman SM. Placental malaria and its effect on pregnancy outcomes in Sudanese women from Blue Nile state. Malar J. 2017;16:374. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-2028-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fried M, Duffy PE. Malaria during pregnancy. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2017;7. 10.1101/cshperspect.a025551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Rogerson SJ, Desai M, Mayor A, Sicuri E, Taylor SM, van Eijk AM. Burden, pathology, and costs of malaria in pregnancy: new developments for an old problem. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:e107–e118. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Okiring J, Olwoch P, Kakuru A, Okou J, Ochokoru H, Ochieng TA, Kajubi R, Kamya MR, Dorsey G, Tusting LS. Household and maternal risk factors for malaria in pregnancy in a highly endemic area of Uganda: a prospective cohort study. Malar J. 2019;18:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12936-019-2779-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ofori MF, Lamptey H, Dickson EK, Kyei-Baafour E, Hviid L. Etiology of placental plasmodium falciparum malaria in African women. J Infect Dis. 2018;218:277–281. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O’Neil-Dunne I, Achur RN, Agbor-Enoh ST, Valiyaveettil M, Naik RS, Ockenhouse CF, et al. Gravidity-dependent production of antibodies that inhibit binding of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes to placental chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan during pregnancy. Infect Immun. 2001;69:7487–7492. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.12.7487-7492.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Duffy PE. Plasmodium in the placenta: parasites, parity, protection, prevention and possibly preeclampsia. Parasitology. 2007;134:1877–1881. doi: 10.1017/S0031182007000170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Steketee RW, Wirima JJ, Bloland PB, Chilima B, Mermin JH, Chitsulo L, et al. Impairment of a pregnant woman’s acquired ability to limit Plasmodium falciparum by infection with human immunodeficiency virus type-1. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;55:42–49. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.55.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Natureeba P, Ades V, Luwedde F, Mwesigwa J, Plenty A, Okong P, Charlebois ED, Clark TD, Nzarubara B, Havlir DV, Achan J, Kamya MR, Cohan D, Dorsey G. Lopinavir/ritonavir-based antiretroviral treatment (ART) versus efavirenz-based ART for the prevention of malaria among HIV-infected pregnant women. J Infect Dis. 2014;210:1938–1945. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gelaye B, Rondon MB, Araya R, Williams MA. Epidemiology of maternal depression, risk factors, and child outcomes in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:973–982. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30284-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weobong B, Ten Asbroek AHA, Soremekun S, Manu AA, Owusu-Agyei S, Prince M, et al. Association of antenatal depression with adverse consequences for the mother and newborn in rural Ghana: findings from the DON population-based cohort study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e116333. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.• Ategeka J, Kakuru A, Kajubi R, Wasswa R, Ochokoru H, Arinaitwe E, et al. Relationships between measures of malaria at delivery and adverse birth outcomes in a high-transmission area of Uganda. J Infect Dis. 2020. 10.1093/infdis/jiaa156This study investigated the association between various measurements of malaria at delivery (placental blood microscopy, LAMP, and histopathology) and adverse birth outcomes. Placental histopathology detected more malarial infection and was associated with small for gestational age. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Lufele E, Umbers A, Ordi J, Ome-Kaius M, Wangnapi R, Unger H, Tarongka N, Siba P, Mueller I, Robinson L, Rogerson S. Risk factors and pregnancy outcomes associated with placental malaria in a prospective cohort of Papua New Guinean women. Malar J. 2017;16:427. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-2077-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moore KA, Simpson JA, Scoullar MJL, McGready R, Fowkes FJI. Quantification of the association between malaria in pregnancy and stillbirth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Heal. 2017;5:e1101–e1112. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30340-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Briggs J, Ategeka J, Kajubi R, Ochieng T, Kakuru A, Ssemanda C, Wasswa R, Jagannathan P, Greenhouse B, Rodriguez-Barraquer I, Kamya M, Dorsey G. Impact of microscopic and submicroscopic parasitemia during pregnancy on placental malaria in a high-transmission setting in Uganda. J Infect Dis. 2019;220:457–466. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nambozi M, Tinto H, Mwapasa V, Tagbor H, Kabuya JBB, Hachizovu S, Traoré M, Valea I, Tahita MC, Ampofo G, Buyze J, Ravinetto R, Arango D, Thriemer K, Mulenga M, van Geertruyden JP, D’Alessandro U. Artemisinin-based combination therapy during pregnancy: outcome of pregnancy and infant mortality: a cohort study. Malar J. 2019;18:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12936-019-2737-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Boudová S, Divala T, Mungwira R, Mawindo P, Tomoka T, Laufer MK. Placental but not peripheral Plasmodium falciparum infection during pregnancy is associated with increased risk of malaria in infancy. J Infect Dis. 2017;216:732–735. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Walker PGT, Floyd J, ter Kuile F, Cairns M. Estimated impact on birth weight of scaling up intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy given sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine resistance in Africa: a mathematical model. PLoS Med. 2017;14:1–19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Del Castillo M, Szymanski AM, Slovin A, Wong ECC, De Biasi RL. Case report: congenital Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Washington, DC. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;96:167–169. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tassi Yunga S, Fouda GG, Sama G, Ngu JB, Leke RGF, Taylor DW. Increased susceptibility to Plasmodium falciparum in infants is associated with low, not high, placental malaria parasitemia. Sci Rep. 2018;8:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18574-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hangi M, Achan J, Saruti A, Quinlan J, Idro R. Congenital malaria in newborns presented at Tororo General Hospital in Uganda: a cross-sectional study. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2019;100:1158–1163. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.17-0341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Adam I, Elhassan EM, Haggaz AED, Ali AAA, Adam GK. A perspective of the epidemiology of malaria and anaemia and their impact on maternal and perinatal outcomes in Sudan. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2011. 10.3855/jidc.1282. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Briggs J, Ategeka J, Kajubi R, Ochieng T, Kakuru A, Ssemanda C, Wasswa R, Jagannathan P, Greenhouse B, Rodriguez-Barraquer I, Kamya M, Dorsey G. Impact of microscopic and submicroscopic parasitemia during pregnancy on placental malaria in a high-transmission setting in Uganda. J Infect Dis. 2019;220:457–466. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vásquez AM, Medina AC, Tobón-Castaño A, Posada M, Vélez GJ, Campillo A, González IJ, Ding X. Performance of a highly sensitive rapid diagnostic test (HS-RDT) for detecting malaria in peripheral and placental blood samples from pregnant women in Colombia. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0201769. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vásquez AM, Zuluaga L, Tobón A, Posada M, Vélez G, González IJ, Campillo A, Ding X. Diagnostic accuracy of loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) for screening malaria in peripheral and placental blood samples from pregnant women in Colombia. Malar J. 2018;17:262. doi: 10.1186/s12936-018-2403-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bulmer JN, Rasheed FN, Francis N, Morrison L, Greenwood BM. Placental malaria. I Pathological classification. Histopathology. 1993;22:211–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1993.tb00110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Muehlenbachs A, Fried M, McGready R, Harrington WE, Mutabingwa TK, Nosten F, Duffy PE. A novel histological grading scheme for placental malaria applied in areas of high and low malaria transmission. J Infect Dis. 2010;202:1608–1616. doi: 10.1086/656723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu Y, Griffin JB, Muehlenbachs A, Rogerson SJ, Bailis AJ, Sharma R, Sullivan DJ, Tshefu AK, Landis SH, Kabongo JMM, Taylor SM, Meshnick SR. Diagnosis of placental malaria in poorly fixed and processed placental tissue. Malar J. 2016;15:272. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1314-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ouédraogo S, Accrombessi M, Diallo I, Codo R, Ouattara A, Ouédraogo L, et al. Placental impression smears is a good indicator of placental malaria in sub-saharan Africa. Pan Afr Med J. 2019. 10.11604/pamj.2019.34.30.20013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.Madanitsa M, Kalilani L, Mwapasa V, van Eijk AM, Khairallah C, Ali D, Pace C, Smedley J, Thwai KL, Levitt B, Wang D, Kang’ombe A, Faragher B, Taylor SM, Meshnick S, ter Kuile FO. Scheduled intermittent screening with rapid diagnostic tests and treatment with dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine versus intermittent preventive therapy with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine for malaria in pregnancy in Malawi: an open-label randomized controlled Tr. PLoS Med. 2016;13:1–19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kakuru A, Jagannathan P, Muhindo MK, Natureeba P, Awori P, Nakalembe M, et al. Dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine for the prevention of malaria in pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:928–939. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1509150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Desai M, Gutman J, L’Lanziva A, Otieno K, Juma E, Kariuki S, et al. Intermittent screening and treatment or intermittent preventive treatment with dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine versus intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine for the control of malaria during pregnancy in western Kenya: an open-lab. Lancet. 2015;386:2507–2519. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00310-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Savic RM, Jagannathan P, Kajubi R, Huang L, Zhang N, Were M, Kakuru A, Muhindo MK, Mwebaza N, Wallender E, Clark TD, Opira B, Kamya M, Havlir DV, Rosenthal PJ, Dorsey G, Aweeka FT. Intermittent preventive treatment for malaria in pregnancy: optimization of target concentrations of dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67:1079–1088. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.•• Group TPS. Four artemisinin-based treatments in African pregnant women with malaria. 2016. 10.1056/NEJMoa1508606, 10.1056/NEJMoa1508606Before this study, there was limited information in on the safety and efficacy of artemisinin combination treatments for malaria in pregnant women. This study demonstrated that out of four artemisinin-based options, dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine had the best efficacy and an acceptable safety profile.

- 72.Kuepfer I, Mishra N, Bruce J, Mishra V, Anvikar AR, Satpathi S, Behera P, Muehlenbachs A, Webster J, terKuile F, Greenwood B, Valecha N, Chandramohan D. Effectiveness of intermittent screening and treatment for the control of malaria in pregnancy: a cluster randomised trial in India. BMJ Glob Heal. 2019;4:e001399. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Patel JC, Hathaway NJ, Parobek CM, Thwai KL, Madanitsa M, Khairallah C, Kalilani-Phiri L, Mwapasa V, Massougbodji A, Fievet N, Bailey JA, ter Kuile FO, Deloron P, Engel SM, Taylor SM, Juliano JJ, Tuikue Ndam N, Meshnick SR. Increased risk of low birth weight in women with placental malaria associated with P. falciparum VAR2CSA clade. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-04737-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rogerson SJ, Aitken EH. Progress towards vaccines to protect pregnant women from malaria. EBioMedicine. 2019;42:12–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chêne A, Gangnard S, Guadall A, Ginisty H, Leroy O, Havelange N, Viebig NK, Gamain B. Preclinical immunogenicity and safety of the cGMP-grade placental malaria vaccine PRIMVAC. EBioMedicine. 2019;42:145–156. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.•• Sirima SB, Richert L, Chêne A, Konate AT, Campion C, Dechavanne S, et al. PRIMVAC vaccine adjuvanted with Alhydrogel or GLA-SE to prevent placental malaria: a first-in-human, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020. 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30739-XThis study investigated the safety and immunogenity of PRIMVAC vaccine among two different women populations from France and Burkina Faso. They showed that PRIMVAC was safe and immunogenic and induced functional antibodies against homologous VAR2CSA variant and with higher doses also against heterologous variants. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 77.Mordmüller B, Sulyok M, Egger-Adam D, Resende M, De Jongh WA, Jensen MH, et al. First-in-human, randomized, double-blind clinical trial of differentially adjuvanted PAMVAC, a vaccine candidate to prevent pregnancy-associated malaria. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;69:1509–1516. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cutts JC, Agius PA, Lin Z, Powell R, Moore K, Draper B, et al. Pregnancy-specific malarial immunity and risk of malaria in pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Med. 2020;18:1–21. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1467-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Benavente ED, Oresegun DR, de Sessions PF, Walker EM, Roper C, Dombrowski JG, de Souza RM, Marinho CRF, Sutherland CJ, Hibberd ML, Mohareb F, Baker DA, Clark TG, Campino S. Global genetic diversity of var2csa in Plasmodium falciparum with implications for malaria in pregnancy and vaccine development. Sci Rep. 2018;8:15429. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-33767-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Doritchamou J, Teo A, Morrison R, Arora G, Kwan J, Manzella-Lapeira J, et al. Functional antibodies against placental malaria parasites are variant dependent and differ by geographic region. Infect Immun. 2019;87:1–14. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00865-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]