Abstract

A 25-year-old woman brought to the hospital with symptoms of acute confusion, disorientation, diplopia, hearing loss and unsteady gait which started 4 days prior to her presentation with rapid worsening in its course until the day of admission. She had a surgical history of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy 2 months earlier which was complicated by persistent vomiting around one to three times per day. She lost 30 kg of her weight over 2 months and was not compliant to vitamin supplementation. CT of the brain was unremarkable. Brain MRI was done which showed high signal intensity lesions involving the bilateral thalamic regions symmetrically with restricted diffusion on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery imaging. Other radiological investigations, such as magnetic resonance venography and magnetic resonance angiography of the brain were unremarkable. An official audiogram confirmed the sensorineural hearing loss. A diagnosis of Wernicke’s encephalopathy due to thiamin deficiency post-sleeve gastrectomy was made based on the constellation of her medical background, clinical presentation and further supported by the distinct MRI findings. Consequently, serum thiamin level was requested and intravenous thiamin 500 mg three times per day for six doses was started empirically, then thiamin 250 mg intravenously once daily given for 5 more days. Marked improvement in cognition, eye movements, strength and ambulation were noticed soon after therapy. She was maintained on a high caloric diet with calcium, magnesium oxide, vitamin D supplements and oral thiamin with successful recovery of the majority of her neurological function with normal cognition, strength, reflexes, ocular movements, but had minimal resolution of her hearing deficit. Serum thiamin level later was 36 nmol/L (67–200).

Keywords: obesity (nutrition), neurology, malnutrition

Background

Bariatric surgeries have been recognised as the most effective long-term treatment modality for severe obesity.1 Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) is the most popular bariatric surgery performed worldwide.2 Thiamin deficiency and Wernicke’s encephalopathy (WE) is often considered a disease of individuals with alcohol misuse, but it is also found in other cases such as chronic malnourishment, cachexia secondary to malignancy and more recently described post-bariatric surgery. Such a deficiency is more commonly recognised following malabsorptive type of bariatric procedures but can also occur with restrictive weight reduction interventions. WE can sometimes present with atypical symptoms such as hypothermia, papilloedema, seizures and hearing loss.3 An adequate dietary plan and vitamin supplements are required to avoid such complications, in addition to vigilance to uncommon presenting features of WE to avoid irreversible damage in patients undergoing bariatric procedures.

We reported a case of WE due to thiamin deficiency post-bariatric surgery which necessitated vitamin replacement and high caloric diet for improvement and recovery of her neurological symptoms to maintain normal functional status postoperatively.

Case presentation

A fit and well 25-year-old woman brought to the hospital with acute confusion, disorientation, diplopia, hearing loss and unsteady gait. The symptoms started 4 days prior to her presentation with rapid worsening in its course until the day of admission. The family denied the patient reporting any headache, neck pain, photophobia, fever, sick contacts or recent travel prior to presentation. She had a surgical history of LSG 2 months earlier which was complicated by persistent vomiting around one to three times per day. She lost 30 kg of her weight over 2 months and was not compliant to vitamin supplementation. On presentation she was conscious but disoriented to time, place and person.

Vital signs showed tachycardia at 140 beats/min, tachypnea with a respiratory rate of 28/min and the blood pressure was unrecordable by manual sphygmomanometer. General examinations of the heart, chest and abdomen were unremarkable.

Neurological examination revealed marked confusion and disorientation, lax neck, bilateral equal reactive pupils, bidirectional horizontal and vertical gaze evoked nystagmus, in addition to bilateral profound sensorineural hearing loss identified through Weber and Rinne tests. Her strength was 4/5 in both upper and lower limbs and had bilateral lower limb hypoesthesia with generalised brisk deep tendon reflexes.

Investigations

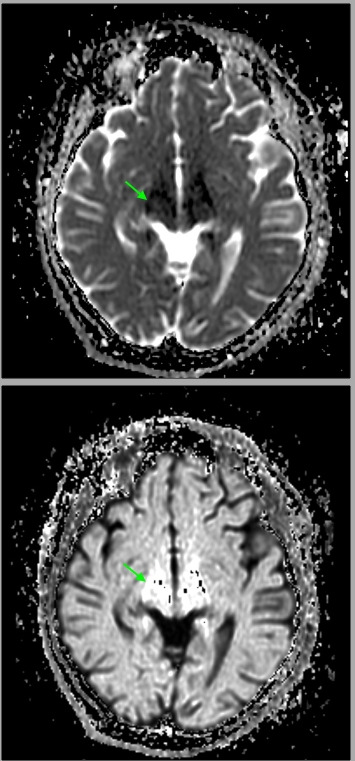

Her pertinent laboratory investigations are shown in (table 1). Serum thiamin level was requested initially and the patient was started on thiamin replacement empirically, few days later it was as the level shown in the table. Initial screening CT of the brain was unremarkable. Brain MRI was done which showed high signal intensity lesions involving the bilateral thalamic regions symmetrically with restricted diffusion on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery imaging (figure 1). Other radiological investigations, such as magnetic resonance venography (MRV) and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) of the brain were unremarkable. An official audiogram confirmed the sensorineural hearing loss. Thorough investigation ruled out any gastric leakage or obstructive aetiologies. Lumbar puncture was not performed owing to low concern for any other pathology.

Table 1.

Initial blood investigations

| Test | Result | Reference range |

| Haemoglobin | 13.7 g/L | 11.5–12.5 |

| White cell count | 9.8×109/L | 5.5–15.5×109/L |

| Creatinine | 107 µmol/L | 44–80 |

| Urea | 8.88 mmol/L | 2.8–7.1 |

| Sodium | 146 mmol/L | 135–146 |

| Potassium | 4.3 mmol/L | 3.5–5.3 |

| Magnesium | 0.8 mmol/L | 0.74–0.99 |

| Prothrombin time | 24.5 | 12.8–15.2 |

| Activated partial thromboplastin time | 26.3 | 25.8–34.2 |

| International normalised ratio | 1.77 | 0.9–1.1 |

| Albumin | 38.4 g/L | 35–52 |

| Amylase | 93 IU/L | 25–130 |

| Lipase | 187 IU/L | 13–60 |

| Alanine aminotransferase | 166 IU/L | 5–37 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 64 IU/L | 5–34 |

| Total bilirubin | 23.1 µmol/L | 2.5–22 |

| Vitamin D | 7.5 nmol/L | >50 |

| Vitamin B12 | 1400 ng/mL | 200–900 |

| Thyroid stimulating hormone | 6.4 mIU/L | 0.45–4.5 |

| Free thyroxine | 17.7 pmol/L | 10–20 |

| Serum thiamin | 36 nmol/L | 67–200 |

Figure 1.

Brain MRI showed bilateral high fluid-attenuated inversion recovery signal intensity lesions in the thalamic regions, a typical finding of Wernicke’s encephalopathy.

Differential diagnosis

There are several neurological and systemic conditions that can result in acute confusion in young age. These include central nervous system infections such as meningitis and encephalitis, ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke, metabolic, hepatic and uraemic encephalitis, alcohol intoxication or withdrawal, drug reaction or drug overdose. Our patient did not have any clinical correlation with these conditions, given that the family denied history of fever, headache, neck pain and recent travel or contact to sick people, on examination no meningeal irritation signs. CT MRV MRA of the brain was unremarkable which ruled out ischaemic, haemorrhagic strokes and structural or vascular abnormalities.

A diagnosis of WE due to thiamin deficiency post-sleeve gastrectomy was made based on the constellation of her medical and surgical background, clinical presentation with symptoms of the classical triad of WE and further supported by ‘Caine’ criteria, the suggested criteria to diagnose WE, plus the distinct MRI findings and marked improvement after thiamin replacement.

Treatment

She was admitted to the intensive care unit for resuscitation and close monitoring.

Consequently, intravenous thiamin 500 mg three times per day for six doses was started empirically then thiamin 250 mg intravenously once daily given for 5 days more. Marked improvement in cognition, eye movements, strength and ambulation were noticed soon after therapy. On day 3 she was transferred to general medical ward. She was maintained on oral thiamin, high caloric diet with calcium, magnesium oxide and vitamin D supplements.

Outcome and follow-up

Significant improvement of her symptoms had been established after thiamin and mineral replacement. On discharge, she had recovered the majority of her neurological function with normal cognition, strength, reflexes and ocular movements but had minimal resolution of her hearing deficit. She was discharged from hospital with follow-up in internal medicine, neurology and physiotherapy clinics 1 week after discharge. She was following up in clinics regularly with good outcome and further improvement.

Discussion

Bariatric procedures have achieved outstanding results in terms of weight loss and improvement in comorbidities. However, there remain some associated risks to these procedures; most of which have been described in the form of anastomotic leakage, bleeding, stenosis and nutritional deficiency (ND).2 ND post-bariatric surgery can arise from several mechanisms that include preoperative deficiency, malabsorption, inadequate supplementation and reduced dietary intake.4 Many nutrients can be affected post-bariatric surgery including thiamin, a water-soluble vitamin also known as vitamin B1. Thiamin is primarily found in foods such as brown rice, yeast, legumes and cereals made from whole grains.5 Thiamine is absorbed in the small intestine via both active transport and passive diffusion with the jejunum being the major site of absorption.6 Continuous intake of thiamin is required to maintain normal body levels due to limited tissue storage although the half-life of thiamin can extend to 10–20 days.7 Thiamin deficiency and WE is well established in patients with alcohol misuse disorder, chronic malnourishment and malignancy, but has also been commonly encountered post-bariatric surgery.8

WE was first described in patients who had bariatric surgery in 1981 with over 95% of cases of WE after bariatric surgery involved gastric bypass operations.9 Thiamine deficiency has been discovered in up to 49% patients undergoing gastric bypass owing to its malabsorptive nature. Nonetheless there have been a number of reported cases in the literature after sleeve gastrectomy mainly owing to protracted vomiting.10 Current guidelines for bariatric surgery suggest preventive thiamin supplementation (12 mg) in multivitamin treatment for all patients undergoing surgery, and higher doses for patients with suspicion for deficiency.11 Typically thiamin deficiency occurs around 6 weeks to 3 months after surgery, but has been reported to occur as early as 2 weeks postoperatively.12

Our patient presented 60 days postoperatively with a picture of WE in addition to the uncommon manifestation of hearing impairment. MRI findings were supportive of the diagnosis negating more invasive testing. Her deficiency most likely resulted from a multitude of reasons including limited storage due to thiamin’s short half-life, poor oral intake due to vomiting and non-compliance with vitamin replacement. Replenishment of her thiamin stores leads to prompt improvement in the majority of her symptoms. This rapid improvement has also been observed in other reported cases.12

Less common findings in WE that can impair or delay the diagnosis of WE include auditory symptoms in the form of hearing impairment or tinnitus. Hearing impairment is often in the form of sensorineural deficit and is thought to correspond to brain abnormalities involving the geniculate nuclei of the thalamus or the inferior colliculi. However, an alternative aetiology has been proposed by Prosperini et al,13 who demonstrated that hearing loss in WE can be due to peripheral acoustic nerve damage by showing deficits on brainstem auditory-evoked potential testing in their patient. From reviewing the literature (table 2), there appears to be a limited number of patients suffering from auditory dysfunction as part of WE manifestation. A total of 17 cases were identified with no unifying underlying aetiology for the development of WE; although gastric surgery appeared to be the most common precipitator (7/17). Out of 17 patients 1 suffered from tinnitus,14 and the remainder had hearing impairment. However, a large proportion of the patients (12/17) were women, which may shed light as a possible underlying predisposition. The majority (9/17) had full recovery of their auditory deficit, while (5/17) had a partial response as in our patient. This may reflect the time-frame at which the illness was picked up and treatment with thiamine initiated, favouring earlier treatment. Only one patient did not have any tangible recovery of her hearing impairment,15 and uniquely in this patient, she had repeated presentations of WE which may point towards the chronicity of the illness and irreversible peripheral or central nervous damage sustained.

Table 2.

Case reports of auditory involvement associated with thiamine deficiency

| Author | Age/sex | Presumed aetiology | MRI findings | Auditory symptom recovery |

| Kondo et al16 | 28/F | Cancer-induced dietary limitations, 5-FU, and parenteral nutrition | Not reported | Yes |

| Towbin et al17 | 15/F | Gastric bypass | CT—non-specific findings. MRI not done | Yes |

| Walker et al18 | 17/F | Hyperemesis gravidarum | Bilateral hyperintensities of medial thalami and posterior limb of internal capsule | Yes |

| Foster et al19 | 35/F | Gastric bypass | Bilateral hyperintensities of floor of the fourth ventricle, periaqueductal grey matter, the medial thalami, and the premotor and motor cortices | Not mentioned |

| Wilson et al20 | 17/F | Hyperemesis gravidarum | Bilateral medial thalamic signal hyperintensities | Partial |

| Flabeau et al*14 | 31/F | Crohn’s disease/parenteral nutrition | Signal changes in inferior colliculi | Yes |

| Jethava et al21 | 35/F | Gastric bypass | Bilateral symmetric intraparenchymal thalami signal changes | Partial |

| Scarano et al22 | 27/F | Sleeve gastrectomy | Signal hyperintensities of the thalamus, periaqueductal grey matter, mammillary body and caudate nucleus | Not mentioned |

| Zhang et al23 | 23/M | Pancreatitis—diet limitation | Symmetric hyperintensities in the bilateral inferior colliculi, posteromedial thalamus, mammillary bodies and cerebellar peduncles | Partial |

| Lamdhade et al15 | 16/F | Failure to thrive from intestinal atresia | Hyperintense signal changes in the bilateral caudate nucleus, mammillary body, periaqueductal region and vermis | No |

| Wu et al24 | 57/M | Anorexia | Bilateral signal hyperintensities in the thalamus, periaqueductal grey matter, and the structures surrounding the third and the fourth ventricles | Yes |

| Moussa et al25 | 49/M | Antral gastritis | Signal hyperintensities in the vermis, bilateral inferior colliculi, dorsomedial thalamus, posterior part of corpus callosum and bilateral inferior cerebellar peduncles | Yes |

| Hansen et al†26 | 43/F | Alcoholism and nutritional | Hyperintensities in the bilateral thalamus, periaqueductal grey matter and the floor of fourth ventricle | Partial |

| Nakamura et al†27 | 61/M | Unclear | Symmetrical high signal intensities involving the tectum, bilateral inferior colliculi and the medial thalami | Yes |

| Gilani et al†28 | 35/F | Gastric bypass | Hyperintense signal changes in the medial thalami, hypothalami, mammillary bodies and periaqueductal grey matter | Partial |

| Nguyen et al29 | 35/F | Sleeve gastrectomy | Signal hyperintensities in the mammillary bodies bilaterally, the periaqueductal grey matter and the inferior colliculus | Yes |

| Prosperini et al13 | 27/M | Sleeve gastrectomy | Symmetric hyperintensities in the bilateral thalamus, hypothalamus and mammillary bodies | Yes |

*Image publication.

†Abstract only.

F, female; 5-FU, 5-fluorouracil; M, male.

Restrictive bariatric surgery is a less common cause of WE due to lower risk of malabsorption, however, it can be confounded by vomiting and poor oral intake leading to acute WE from depleted thiamin stores. In patients undergoing restrictive bariatric surgery, clinicians should still be cognisant for the possibility of developing WE post-surgery despite the lower associated risk, and very rarely can it be associated with hearing loss.

Learning points.

Thiamin deficiency and Wernicke’s encephalopathy (WE) is well established in patients with alcohol misuse disorder, chronic malnourishment and malignancy; but has also been commonly encountered post-bariatric surgery.8

WE typically presents with classical signs of encephalopathy, oculomotor dysfunction and gait ataxia.

WE can sometimes present with atypical symptoms such as hypothermia, papilloedema, seizures and hearing loss.3

Diagnosis of WE is mainly based on clinical suspicion, supported by ‘Caine’ criteria, the suggested criteria to diagnose WE which includes two or more of four: dietary deficiency, oculomotor abnormalities, cerebellar dysfunction and either altered mental status or mild memory impairment.

Laboratory testing of serum thiamin level is not necessarily required to diagnose WE, as serum thiamin level will not reflect brain thiamin concentration, also sensitivity and specificity is unclear, so normal blood thiamin level does not exclude the possibility of WE.

Adequate thiamine replacement required in patients diagnosed with WE to achieve good clinical outcome and significant improvement.

Footnotes

Contributors: EAM was directly involved in patient care. EAM and KA were involved in the conception and design. EAM, SAH and MIG did the data interpretation. EAM, SAH, MIG and KA wrote the report. All authors have contributed to the manuscript editing.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Patterson EJ, Urbach DR, Swanström LL. A comparison of diet and exercise therapy versus laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery for morbid obesity: a decision analysis model. J Am Coll Surg 2003;196:379–84. 10.1016/S1072-7515(02)01754-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parmar CD, Efeotor O, Ali A, et al. Primary banded sleeve gastrectomy: a systematic review. Obes Surg 2018:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sechi G, Serra A. Wernicke’s encephalopathy: new clinical settings a Lancet Neurol. 2007] - PubMed result. Lancet Neurol 2007;6:442–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xanthakos SA. Nutritional deficiencies in obesity and after bariatric surgery. Pediatr Clin North Am 2009;56:1105–21. 10.1016/j.pcl.2009.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ross AC, Caballero BH, Cousins RJ, et al. Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease. Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2014. Available: https://jhu.pure.elsevier.com/en/publications/modern-nutrition-in-health-and-disease-eleventh-edition [Accessed December 25, 2018].

- 6.Institute of Medicine (US) Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes and its Panel on Folate OBV and C Dietary Reference Intakes for Thiamin, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin, and Choline. National Academies Press, 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ariaey-Nejad MR, Balaghi M, Baker EM, et al. Thiamin metabolism in man. Am J Clin Nutr 1970;23:764–78. 10.1093/ajcn/23.6.764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Osiezagha K, Ali S, Freeman C, et al. Thiamine deficiency and delirium. Innov Clin Neurosci 2013;10:26–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lim RB, Blackburn GL, Jones DB. Benchmarking best practices in weight loss surgery. Curr Probl Surg 2010;47:79–174. 10.1067/j.cpsurg.2009.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kröll D, Laimer M, Borbély YM, et al. Wernicke encephalopathy: a future problem even after sleeve gastrectomy? A systematic literature review. Obes Surg 2016;26:205–12. 10.1007/s11695-015-1927-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zafar A. Wernicke's encephalopathy following Roux en Y gastric bypass surgery. Saudi Med J 2015;36:1493–5. 10.15537/smj.2015.12.12643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Fahad T, Ismael A, Soliman MO, et al. Very early onset of Wernicke's encephalopathy after gastric bypass. Obes Surg 2006;16:671–2. 10.1381/096089206776945075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prosperini L, Stasolla A, Grieco G, et al. Non-Alcoholic Wernicke encephalopathy presenting as bilateral hearing loss: a case report. J Neurol 2019;266:1027–30. 10.1007/s00415-019-09220-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flabeau O, Foubert-Samier A, Meissner W, et al. Hearing and seeing: unusual early signs of Wernicke encephalopathy. Neurology 2008;71:694. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000324599.66359.b1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lamdhade S, Almulla A, Alroughani R. Recurrent Wernicke s Encephalopathy in a 16-Year-Old Girl with Atypical Clinical and Radiological Features. Case Rep Neurol Med 2014;2014:1–6. 10.1155/2014/582482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kondo K, Fujiwara M, Murase M, et al. Severe acute metabolic acidosis and Wernicke's encephalopathy following chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin: case report and review of the literature. Jpn J Clin Oncol 1996;26:234–6. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jjco.a023220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Towbin A, Inge TH, Garcia VF, et al. Beriberi after gastric bypass surgery in adolescence. J Pediatr 2004;145:263–7. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.04.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walker MA, Zepeda R, Afari HA, et al. Hearing loss in Wernicke encephalopathy. Neurol Clin Pract 2014;4:511–5. 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foster D, Falah M, Kadom N, et al. Wernicke encephalopathy after bariatric surgery: losing more than just weight. Neurology 2005;65:1987. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000188822.86529.f0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson RK, Kuncl RW, Corse AM. Wernicke's encephalopathy: beyond alcoholism. Nat Clin Pract Neurol 2006;2:54–8. 10.1038/ncpneuro0094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jethava A, Dasanu CA. Acute Wernicke encephalopathy and sensorineural hearing loss complicating bariatric surgery. Conn Med 2012;76:603–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scarano V, Milone M, Di Minno MND, et al. Late micronutrient deficiency and neurological dysfunction after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a case report. Eur J Clin Nutr 2012;66:645–7. 10.1038/ejcn.2012.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang S-Q, Guan Y-T. Acute bilateral deafness as the first symptom of Wernicke encephalopathy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2012;33:E44–5. 10.3174/ajnr.A3040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu L, Jin D, Sun X, et al. Cortical damage in Wernicke's encephalopathy with good prognosis: a report of two cases and literature review. Metab Brain Dis 2017;32:377–84. 10.1007/s11011-016-9920-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moussa TD, Hamid A, Fatimata HD, et al. An unusual mode of revelation of Wernicke's encephalopathy: bilateral blindness with bilateral hypoacousia. Neurol India 2017;65:1406–7. 10.4103/0028-3886.217941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hansen M, Bozorgi A, Richards S, et al. A case of severe Wernicke encephalopathy with bilateral sensorineural hearing loss (P2.139). Neurology 2018;90. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakamura T, Imai K, Hamanaka M, et al. [A case of Wernicke encephalopathy with hypoacusia and MR high intensity of the inferior colliculi that normalized after thiamine administration]. Rinsho Shinkeigaku 2018;58:100–4. 10.5692/clinicalneurol.cn-001082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilani W, Khazanehdari S, Noor E. Deaf, confused and blind: a rare presentation of Wernicke encephalopathy (P1.9-046). Neurology 2019;92. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nguyen JTT, Franconi C, Prentice A, et al. Wernicke encephalopathy hearing loss and palinacousis. Intern Med J 2019;49:536–9. 10.1111/imj.14249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]