Abstract

Background

An investigation into differences in the management and treatment of severe aortic stenosis (AS) between Germany, France and the UK may allow benchmarking of the different healthcare systems and identification of levers for improvement.

Methods

Patients with a diagnosis of severe AS under management at centres within the IMPULSE and IMPULSE enhanced registries were eligible.

Results

Data were collected from 2052 patients (795 Germany; 542 France; 715 UK). Patients in Germany were older (79.8 years), often symptomatic (89.5%) and female (49.8%) and had a lower EF (53.8%) than patients in France and UK. Comorbidities were more common and they had a higher mean Euroscore II.

Aortic valve replacement (AVR) was planned within 3 months in 70.2%. This was higher (p<0.001) in Germany than France/ UK. Of those with planned AVR, 82.3% received it within 3 months with a gradual decline (Germany>France> UK; p<0.001). In 253 patients, AVR was not performed, despite planned. Germany had a strong transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) preference (83.2%) versus France/ UK (p<0.001). Waiting time for TAVI was shorter in Germany (24.9 days) and France (19.5 days) than UK (40.3 days).

Symptomatic patients were scheduled for an AVR in 79.4% (Germany> France> UK; p<0.001) and performed in 83.6% with a TAVI preference (73.1%). 20.4% of the asymptomatic patients were intervened.

Conclusion

Patients in Germany had more advanced disease. The rate of intervention within 3 months after diagnosis was startlingly low in the UK. Asymptomatic patients without a formal indication often underwent an intervention in Germany and France.

Keywords: surgery-valve, percutaneous valve therapy, aortic valve disease, quality of care and outcomes

KEY QUESTIONS.

What is already known about this subject?

Patients with severe aortic stenosis (AS) are still diagnosed and treated late. The European Society of Cardiology/European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery guidelines recommend surgical aortic valve replacement for patients with symptomatic AS at low surgical risk, and transcatheter aortic valve implantation for those who are at increased operative risk. Despite accepted European guidelines, the practice of cardiovascular medicine differs between European countries.

What does this study add?

The investigation of differences in the management and treatment of severe AS between Germany, France and the UK revealed that patients in Germany had more advanced disease. The rate of intervention within 3 months after diagnosis was startlingly low in the UK. Asymptomatic patients without formal indication often underwent an intervention in Germany and France.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

The disclosure of differences in the treatment of patients with severe AS in Germany, France and the UK offers the possibility of optimising, adapting and critically questioning the respective procedure for the benefit of the patients.

Introduction

Patients with severe aortic stenosis (AS) are still diagnosed late and show advanced symptoms at the time of referral.1 Timely intervention is crucial to improve quality of life and survival.2 3 Once symptoms develop, the average survival of patients without appropriate intervention is 2–3 years.3 The only effective treatment for severe AS is aortic valve replacement (AVR), using either surgical AVR (SAVR) or transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI).2 3 The European Society of Cardiology/European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery guidelines recommend SAVR for patients with symptomatic AS at low surgical risk, and TAVI for those who are at increased operative risk.2 However, data from the IMPULSE registry, which covers nine European countries, indicate that almost a quarter of patients with symptomatic AS meeting guideline recommendations for AVR do not undergo such treatment.1

Despite accepted European guidelines, the practice of cardiovascular medicine differs between European countries.4–7 In the case of aortic valve disease, differences in the clinical features of patients undergoing intervention, time to intervention, implanted aortic valve sizes, type of anaesthesia and utilisation of TAVI have been reported.8–13 The rate of adoption of TAVI varies between countries, with Germany, as one of the earliest adopters, having the highest rate of usage14; by 2015, TAVI accounted for 59% of all aortic valve interventions in Germany compared with 36% in France.11 15 The percentage of TAVI-eligible patients who actually receive TAVI also varies, ranging from 36.2% in Germany to 6.4% in Portugal in 2011.14 Between-country differences in the rates of short-term complications after TAVI, including 30-day mortality, stroke, pacemaker implantation and paravalvular leak, have also been reported.16

Further evaluation of differences in the management of patients with severe AS between countries could provide impact for the various healthcare systems and help identify aspects of management that could be improved. To this end, an investigation into the potential differences between Germany, France and the UK with respect to the presentation and management of patients with severe AS was made based on two prospective, multicentre European registries, IMPULSE and IMPULSE enhanced with a virtually identical design.1 13 17 18

Methods

Study design and site selection

The design of both the IMPULSE (recruitment March 2015 to January 2017)17 and IMPULSE enhanced (recruitment March 2017 to October 2018)18 registries have been described previously. In short, both were prospective, multinational registries of patients with severe AS in Europe. Sites were selected based on their ability to deliver a full range of treatment options for AS including surgical and transcatheter procedures. Sites for the current analysis were those from Germany (Kiel, Cologne, Mainz, Erlangen, Trier, Munich, Kaiserslautern, Berlin), France (Paris and Annency) and the UK (Birmingham, London, Middlesbrough). Patient informed consent was obtained based on national legal requirements.

Patients

Consecutive patients (on a centre level) of at least 18 years of age were included in the registries based on a new finding of native severe AS on echocardiography, irrespective of symptoms. A diagnosis of severe AS was defined as one or more of the following findings: an aortic valve area (AVA) of <1 cm2 (computed using continuity equation), an indexed AVA of <0.6 cm2/m2, a maximum jet velocity (Vmax) of >4 m/s or a mean transvalvular gradient of >40 mm Hg.19 Patients with prior aortic valve interventions were excluded.

Data collection

Severe symptoms were defined as the presence of Canadian Cardiovascular Society class III or IV angina, New York Heart Association functional class III or IV and/or dizziness on exertion/syncope. Frailty was assessed according to the ability of the patient to walk 5 m in less than 6 s and to perform activities of daily living (ADL).20 ADL and life expectancy were assessed by the dedicated nurses or physicians, but no specific list of ADL or risk calculator was recommended. The results of the echocardiographic assessment were recorded, including the presence of coexisting aortic regurgitation, mitral or tricuspid valve disease; transvalvular gradient; left ventricle dimensions and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).

At 3 months after enrolment, information on vital status (alive/dead), treatment decisions (SAVR, TAVI, balloon aortic valvuloplasty, conservative treatment or no decision) and the number of interventions performed were documented. Watchful waiting was defined as the scheduling of further patient follow-up. Data were entered into a standardised electronic case report form.

Statistics

Data are presented descriptively, using means with SD, medians with IQR or absolute values with percentages. Comparisons between countries were made using a Pearson’s X2 or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, and a t-test, Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon rank sum test or analysis of variance for continuous variables. A p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS V.24.0 (IBM).

Results

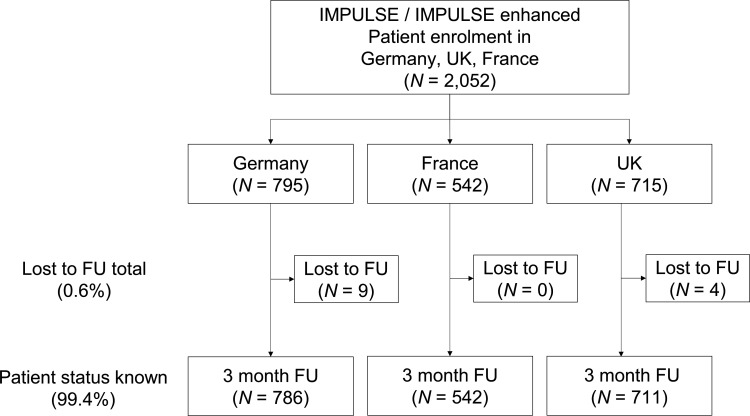

The study included 2052 patients with 795 patients (38.7%) recruited from Germany, 542 patients from France (26.4%) and 715 patients (34.8%) from the UK (figure 1). After 3 months, a status was available for 2039 patients (99.4%), resulting in a loss to follow-up of 0.6%.

Figure 1.

Patient flow chart. Fu, follow-up.

Patient population

Among the three countries, patients in Germany were older (mean age 79.8 years), more often female (49.8%) and more often symptomatic (89.5%) (table 1). Comorbidities such as renal impairment, extracardiac arteriopathy, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pulmonary disease/hypertension and diabetes were all more common in Germany than in the other countries. Patients in Germany had a lower indexed AVA (0.39 vs 0.43 cm2/m2 in France) and a lower ejection fraction (53.8%) than patients in France or the UK. Concomitant valve disease was common in the UK, while it was less common in Germany and France. The mean EuroSCORE II was higher in Germany (5.3%) than in the UK (3.5%) or France (2.9%).

Table 1.

Patient and disease characteristics

| Total (n=2052) |

Germany (n=795) |

France (n=542) |

UK (n=715) |

P value | |

| Age (years) | 78.0±10.4 | 79.8±7.9 | 76.0±11.1 | 77.5±11.8 | <0.001 |

| Female gender (%) | 46.6 | 49.8 | 43.0 | 45.9 | 0.043 |

| Frailty severe (%) | 4.9 | 5.0 | 4.6 | 5.1 | 0.916 |

| Symptomatic AS * (%) | 79.5 | 89.5 | 72.0 | 73.9 | <0.001 |

| NYHA III/IV (%) | 42.1 | 55.7 | 36.0 | 31.3 | <0.001 |

| Angina CCS III/IV (%) | 3.4 | 5.5 | 1.7 | 3.0 | 0.002 |

| Comorbidities (%) | |||||

| CrCl <50 mL/min (%) | 29.1 | 34.3 | 21.2 | 30.2 | <0.001 |

| Extracardiac arteropathy (%) | 12.4 | 21.8 | 4.8 | 7.5 | <0.001 |

| COPD (%) | 13.2 | 16.0 | 10.0 | 12.5 | 0.005 |

| PAH >55 mm Hg (%) | 8.4 | 11.7 | 8.3 | 4.5 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes on insulin (%) | 8.4 | 11.4 | 9.1 | 4.7 | <0.001 |

| Echocardiography | |||||

| Mean aortic PG (mm Hg) | 45.7±15.3 | 43.6±16.2 | 49.3±14.3 | 45.3±14.5 | <0.001 |

| AVA indexed (cm2/m2) | 0.40±0.11 | 0.39±0.09 | 0.43±0.11 | 0.40±0.12 | <0.001 |

| PAP systolic (mm Hg) | 39.4±14.1 | 43.2±14.5 | 40.6±12.1 | 33.9±13.5 | <0.001 |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 56.0±12.8 | 53.8±13.2 | 58.4±10.9 | 56.7±13.2 | <0.001 |

| Concomitant valve disease (%) | |||||

| Aortic regurg mod/sev (%) | 7.5 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 16.3 | <0.001 |

| Mitral regurg mod/sev (%) | 9.7 | 6.5 | 3.8 | 17.7 | <0.001 |

| Mitral stenosis mod/sev (%) | 2.1 | 0.7 | 3.7 | 2.4 | 0.001 |

| Tricuspid regurg mod/sev (%) | 8.5 | 5.8 | 2.8 | 15.9 | <0.001 |

| EuroSCORE II(%) | 3.9±4.7 | 5.3±6.0 | 2.9±3.1 | 3.5±4.2 | <0.001 |

*Defined as one or more cardiac symptoms presumably related to severe AS (chest pain, shortness of breath, dizziness on exertion/syncope, NYHA III or IV, and Angina pectoris CCS III or IV).

AS, aortic stenosis; AVA, aortic valve area; CCS, Canadian Cardiovascular Society; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CrCI, creatinine clearance; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PAH, pulmonary artery hypertension; PAP, pulmonary artery pressure; PG, pressure gradient; regurg, regurgitation.

Patient status after 3 months

Overall, AVR was planned within 3 months in 70.2% of the cases. This was higher (p<0.001) in Germany than in France and the UK (table 2). Of the patients with planned AVR, 82.3% actually received an AVR within 3 months, again with a gradual decline between Germany and France on the one hand and the UK on the other (p<0.001). Germany had a strong preference for TAVI (83.2%) while France and the UK had a less strong preference (p<0.001). Forty-four patients (3.7%) died within 3 months, despite receiving AVR with higher death rates in Germany than in France/UK. The waiting time for TAVI was substantially shorter (p<0.001) in Germany (24.9 days) and France (19.5 days) than in the UK (40.3 days). Differences were not as pronounced for surgery, where the waiting time was about 14 days shorter in France (21.1 days) than in Germany or the UK. In 253 patients AVR was not performed, despite being planned and 12 patients overall died on the waiting list which is 0.8% of all patients or 4.7% of those waiting. There were no differences between countries in these numbers. In about one-third of patients AVR was neither planned nor performed (29.8%) which reached 49.8% in the UK while it was only 12.7% in Germany (p<0.001). Of these, 12.0% died within 3 months.

Table 2.

Patient status after 3 months

| Total (n=2052) |

Germany (n=795) |

France (n=542) |

UK (n=715) |

P value | |

| Patients available/lost to FU, n (%) | 2039/13 | 786/9 | 542/0 | 711/4 | |

| AVR planned, n (%) | 1431 (70.2) | 686 (87.3) | 388 (71.6) | 357 (50.2) | <0.001 |

| AVR performed, n (%) | 1178 (82.3) | 624 (91.0) | 350 (90.2) | 204 (57.1) | <0.001 |

| TAVI, n (%) | 847 (71.9) | 519 (83.2) | 196 (56.0) | 132 (64.7) | <0.001 |

| SAVR, n (%) | 331 (28.1) | 105 (16.8) | 154 (44.0) | 72 (35.3) | |

| Death despite AVR, n (%) | 44 (3.7) | 33 (5.3) | 7 (2.0) | 4 (2.0) | 0.012 |

| Time to AVR (days) | 26.0±25.1 | 24.9±25.0 | 19.5±20.4 | 40.3±27.2 | <0.001 |

| Time to TAVI (days) | 24.9±25.6 | 22.7±25.1 | 18.3±19.9 | 43.1±26.9 | <0.001 |

| Time to SAVR (days) | 28.9±23.8 | 35.8±21.8 | 21.1±20.9 | 35.2±27.3 | <0.001 |

| AVR not performed, n (%) | 253 (17.7) | 62 (9.0) | 38 (9.8) | 153 (42.9) | <0.001 |

| Death on waiting list, n (%) | 12 (0.8) | 7 (1.0) | 1 (0.3) | 4 (1.1) | 0.311 |

| AVR not planned or no info, n (%) | 608 (29.8) | 100 (12.7) | 154 (28.4) | 354 (49.8) | <0.001 |

| Death, n (%) | 59 (9.7) | 12 (12.0) | 10 (6.5) | 37 (10.5) | 0.267 |

| All-cause death | 115 (5.6) | 52 (6.6) | 18 (3.3) | 45 (6.3) | 0.023 |

| Cardiac-related death (%) | 53 (2.6) | 25 (3.2) | 11 (2.0) | 17 (2.4) | 0.393 |

| Non-cardiac death (%) | 39 (1.9) | 15 (1.9) | 7 (1.3) | 17 (2.4) | 0.371 |

| Unknown cause (%) | 23 (1.1) | 12 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 11 (1.5) | 0.015 |

AVR, aortic valve replacement; FU, follow-up; SAVR, surgical aortic valve replacement; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

The overall death rate in patients with a known status at 3 months was 5.6% (n=115), which was attributed to cardiac reasons in 53 of the 115 (46.1%), non-cardiac reasons (33.9%) or unknown (20.0%). Death rates were higher in Germany and the UK compared with France irrespective of the cause of death.

Patient status by symptoms at baseline

Symptomatic patients were scheduled for an AVR in 79.4% of all cases (Germany>France>UK; p<0.001) (table 3). It was also performed in the majority (83.6% of those planned) and with a strong preference for TAVI (73.1% of those performed). The wait time was about a month (25.3 days for TAVI and 28.6 days for SAVR). In 334 patients, no AVR was planned despite being symptomatic. Germany had the highest proportion of interventions planned (88.9%) and a strong preference for TAVI (84.0%) with intermediate wait times for TAVI and long wait times for SAVR. France had a higher preference for SAVR than the other countries and particularly short wait times for an intervention. The UK had the lowest rate of interventions planned (and the highest rates of decline) with particularly long wait times for TAVI (40.3 days) and less so for SAVR (34.9 days). For 37.5% of the symptomatic patients in the UK no intervention was planned.

Table 3.

Status at 3 months in patients with symptoms at baseline

| Total (n=2052) |

Germany (n=795) |

France (n=542) |

UK (n=715) |

P value | |

| Patients available/lost to FU, n (%) | 2039/13 | 786/9 | 542/0 | 711/4 | |

| Symptomatic patients, n (%) | 1623 (79.6) | 705 (89.7) | 390 (72.0) | 528 (74.3) | <0.001 |

| AVR planned, n (%) | 1289 (79.4) | 627 (88.9) | 332 (85.1) | 330 (62.5) | <0.001 |

| AVR performed, n (%) | 1077 (83.6) | 574 (91.5) | 305 (91.9) | 198 (60.0) | <0.001 |

| TAVI, n (%) | 787 (73.1) | 482 (84.0) | 176 (57.7) | 129 (65.2) | <0.001 |

| SAVR, n (%) | 290 (26.9) | 92 (16.0) | 129 (42.3) | 69 (34.8) | |

| Time to AVR (days) | 26.2±25.1 | 25.1±24.9 | 19.0±20.2 | 40.3±27.1 | <0.001 |

| Time to TAVI (days) | 25.3±25.5 | 23.1±25.0 | 18.1±19.8 | 43.2±26.7 | <0.001 |

| Time to SAVR (days) | 28.6±23.9 | 35.6±21.9 | 20.3±20.8 | 34.9±27.2 | <0.001 |

| AVR not performed, n (%) | 212 (16.4) | 53 (8.5) | 27 (8.1) | 132 (40.0) | <0.001 |

| AVR not planned, n (%) | 334 (20.6) | 78 (11.1) | 58 (14.9) | 198 (37.5) | <0.001 |

AVR, aortic valve replacement; FU, follow-up; SAVR, surgical aortic valve replacement; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

20.4% of the asymptomatic patients were also scheduled for an intervention (table 4). Of these, AVR was indicated in 28.2% based on an LVEF <50%, Vmax >5.5 m/sec or PAP sys>60 mm Hg and it was performed within 3 months in 80% of the patients. The rates of planned interventions were particularly high in Germany (n=59; 72.8%) of which more than in the other countries had a formal indication (42.4%). On the other hand, rates of planned interventions were particularly low in the UK (14.8%). For the majority of planned interventions AVR was not even performed (66.7% of those with an indication and 79.2% of those without).

Table 4.

Status at 3 months in asymptomatic patients at baseline

| Total (n=2052) |

Germany (n=795) |

France (n=542) |

UK (n=715) |

P value | |

| Patients available/lost to FU, n (%) | 2039/13 | 786/9 | 542/0 | 711/4 | |

| Asymptomatic patients, n (%) | 416 (20.4) | 81 (10.3) | 152 (28.0) | 183 (25.7) | <0.001 |

| AVR planned, n (%) | 142 (34.1) | 59 (72.8) | 56 (36.8) | 27 (14.8) | <0.001 |

| AVR indicated* | 40 (28.2) | 25 (42.4) | 12 (21.4) | 3 (11.1) | 0.004 |

| AVR performed, n (%) | 32 (80.0) | 20 (80.0) | 11 (91.7) | 1 (33.3) | 0.134 |

| TAVI, n (%) | 23 (71.9) | 17 (85.0) | 5 (45.5) | 1 (100.0) | 0.054 |

| SAVR, n (%) | 9 (28.1) | 3 (15.0) | 6 (54.5) | 0 (0) | |

| AVR not performed, n (%) | 8 (20.0) | 5 (20.0) | 1 (8.3) | 2 (66.7) | 0.134 |

| AVR not indicated | 102 (71.8) | 34 (57.6) | 44 (78.6) | 24 (88.9) | 0.004 |

| AVR performed, n (%) | 69 (67.6) | 30 (88.2) | 34 (77.3) | 5 (20.8) | <0.001 |

| AVR not performed, n (%) | 33 (32.4) | 4 (11.8) | 10 (22.7) | 19 (79.2) | |

| AVR not planned, n (%) | 274 (65.9) | 22 (27.2) | 96 (63.2) | 156 (85.2) | <0.001 |

*Based on LVEF <50%, Vmax >5.5 m/sec, PAP sys >60 mm Hg.

AVR, aortic valve replacement; FU, follow-up; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; SAVR, surgical aortic valve replacement; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

Discussion

The German and French healthcare systems are funded mainly by a social health insurance whereas the UK system is funded through central taxation. Different systems of funding and reimbursement affect the adoption and implementation of medical technologies, including cardiovascular technologies. None of these countries has absolute restrictions on the number of interventions performed. Substantial differences in the presentation and management of severe AS were evident between three major European countries, based on data from the IMPULSE and IMPULSE enhanced registries. Substantial differences in patient characteristics, the type of intervention delivered and the time to delivery of interventions were seen.

Patients enrolled into the registries in Germany had more advanced disease than patients in France or the UK. German patients tended to be older, more often symptomatic, with a lower ejection fraction and a higher EuroSCORE, and Germany had the highest proportion of urgent cases. The reason for these differences is not clear. One possibility might be that patients in Germany were referred and/or diagnosed with severe AS later than in other countries. It is also possible that the specific German centres involved in the IMPULSE and IMPULSE enhanced registries received more patients with advanced disease/severe symptoms than other centres in Germany.

Planned AVR interventions were performed within 3 months of presentation for the majority of patients with severe AS in Germany and France, although there remains room for improvement, as 9.0% of patients in Germany and more than 9.8% in France did not receive an intervention. However, the 3-month intervention rate was startlingly low in the UK, with less than 42.9% of patients in whom an intervention was agreed actually receiving an intervention within this time frame. Reasons for the delay in treatment provision were not obtained for the current analysis, but possible explanations could involve funding and logistical issues, as during heart team-based decision-making all key player are simultaneously aware of the patient and there is no delay in final decision. Nevertheless, patients waiting for treatment have a higher mortality and are more often admitted to a hospital for heart failure (HF). Furthermore, HF hospitalisation is associated with important morbidity and healthcare costs. TAVR patients who require hospitalisation before their TAVR require a prolonged post-TAVR stay, which also is associated with increased costs.21 22 Greater wait times correlate also with deterioration in functional capacity and quality of life, which negatively affects post-TAVR mortality and recovery. 23 Early treatment is recommended for patients with symptomatic severe AS, because of their otherwise poor prognosis.2 A substantial number of patients in all three countries did not undergo a valve intervention within 3 months, with this most strikingly evident in the UK, where more than 70% of patients (153 planned but not performed, 354 not planned) did not receive an AVR within this timeframe. Improving the timeliness of treatment could help improve outcomes for patients with severe AS. It has been shown that a simple, low-cost, structured communication (facilitated data relay) can help reduce the time to TAVI.13

With respect to the selection of treatment, TAVI was preferred over SAVR for most patients in all three countries, but it was far more common in Germany (where it accounted for 83.2% of interventions) than in France or the UK. This is perhaps not surprising, given that Germany was one of the earliest adopters of TAVI,24 and the rate of TAVI overtook that of SAVR from 2013 onwards.25 More comorbidities, older patients and more advanced disease in the German cohort could also be a reason for more TAVR treatment.

In the current analysis, patients with symptomatic severe AS were likely to receive an appropriate, guideline-recommended2 intervention. Asymptomatic patients were frequently intervened despite the absence of guideline defined criteria such as LVEF <50%, Vmax >5.5 m/sec, pulmonary artery pressure (PAP) sys>60 mm Hg. In 34.1% of the patients an intervention was planned of which 71.8% had no such indication.

It is possible some of these patients had other factors present that made an intervention reasonable such as rapid progression, excessive left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy, elevated brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) and others2. This cannot be determined from the reported data; however, the high rate of intervention in asymptomatic patients in Germany in particular, suggests that at least some of these patients were treated outside of guideline recommendations. Non-adherence to guideline recommendations could be due to various reasons, including under-recognition of symptoms, underutilisation of exercise stress testing to confirm whether patients were symptomatic, and overestimation of surgical risk.26 Overtreatment could be due to an ‘indication creep’ towards treating lower-risk patients with TAVI in addition to the high-risk patients for which this approach was initially intended; this has been noted in Germany previously.11 27

The rate of all-cause mortality during the 3-month period after enrolment into the registry was higher in Germany and the UK (6.6% and 6.3%, respectively) than in France (3.3%), which seems to correlate with the higher risk of patients and the more advanced disease, at least for the German cohort. Previous reports from country-specific registries include 30-day mortality rates of 5.6% after TAVI and 3.1% after SAVR in Germany,25 5.8% and 6.2% after TAVI and 2.1% after SAVR in the UK,28 29 and 5.4% and 6.0% after TAVI in France.30 31 The study was not powered to investigate the impact of delay to treatment and mortality outcomes.

Impact of healthcare systems on outcomes

Centres participating in the IMPULSE and IMPULSE enhanced registries all had the capability of performing both SAVR and TAVI. However, the healthcare systems within which the centres were embedded differ between the various countries. This may have had some effect on the outcomes reported in the current analysis. The German and French healthcare systems are funded mainly by a social health insurance whereas the UK system is funded through central taxation.4 Different systems of funding and reimbursement affect the adoption and implementation of medical technologies, including cardiovascular technologies.32 TAVI has been widely adopted, although the number of TAVIs performed differs between countries14: Germany performed 164 per million persons (pmp) in 2014,27 France performed 86.8 pmp in 201533 and the UK performed 49.5 pmp in 2016.34 More recent rates of 227 pmp for Germany and 137 pmp for France have been reported.35 Administrative data indicate that TAVI comprised 59% of all AVR procedures in Germany in 2015,11 compared with 36% in France in the same year.15 Data for 2015 were not available for the UK; but in 2012, TAVI accounted for 10.9% of all AVRs.28 The current study suggests that the proportion of interventions performed using TAVI continues to increase in all three countries, and ranges from 56.0% in France to 83.2% in Germany.

Multidisciplinary heart teams are advocated as a way of improving the management of complex cases, and may be particularly relevant for patients with AS because their care requires input from several specialties such as cardiology and cardiac surgery.36 37 There is some evidence that the involvement of Heart Teams in TAVI cases can improve clinical outcomes.24 38 In the current study, heart teams were the most common in Germany, with more than 80% of decisions on the management of patients with severe AS made by such teams. In contrast, such teams accounted for just over one-third of decisions in France and the UK, with cardiologists/interventional cardiologists responsible for most decisions in these countries.

Limitations

The data included in this registry have been collected from a number of different centres from three different healthcare systems (Germany, France, UK) across Europe; it does, however not cover all European countries nor all centres in the participating countries. Therefore, it may not be fully representative of the European situation. It will also be only an approximation to the current situation in Germany which has also been investigated in GARY and the German Heart Surgery Report.21–23 As such the strength of the IMPULSE project is not the full coverage, but the consistent documentation of patients across different European centres giving the chance to find national specifics and room for improvement.

Although the reasons for not performing an AVR were queried in this register, there is a possibility that all possible reasons have not been recorded. Furthermore the analysis period was set to 3 months. It was not recorded, if an AVR was performed later than this period or never. But this study was not powered to determine the right time point of AVR. Three month was set to benchmark how fast the AVR was done.

Conclusions

Substantial country-specific differences in the presentation and management of severe AS were evident between three major European countries. Of note, patients in Germany had more advanced disease, the rate of intervention within 3 months was startlingly low in the UK, and asymptomatic patients without an appropriate indication often underwent an intervention in Germany and France.

Miscellaneous

Participating centres

France: Bichat Hospital, Paris (Dr. Messika-Zeitoun), Centre Hospital d’Annecy (Dr. Belle)

Germany: University of Cologne Heart Center, Cologne (Dr. Wahlers, Dr. Baldus), University Clinic Mainz, Mainz (Dr. Schulz), University Hospital Erlangen (Dr. Arnold), Krankenhaus der Barmherzigen Brüder Trier (Dr. Hauptmann), Heart Center Bogenhausen, Munich (Dr. Rieber), Westpfalz-Klinikum, Kaiserslautern (Dr. Bernat), University Heart Center & Charité, Berlin (Dr. Lauten), University of Kiel, Kiel (Dr. Frey, Dr. Lutz)

United Kingdom: St Bartholomew's Hospital, London (Dr. Lloyd), Queen Elizabeth Hospital & Institute of Cardiovascular Sciences, University of Birmingham, Birmingham (Dr. Steeds), James Cook Hospital, Middlesbrough (Dr. Muir, Dr. Belder)

Acknowledgments

Data were captured using the s4trials Software provided by Software for Trials Europe GmbH, Berlin, Germany (www.s4trials-europe.com).

Footnotes

Twitter: @MJLutz, @Richard.Steeds

Contributors: NF, RPS, DM-Z, JK, MT and PB were involved in the conception and design of the study. ML and PB drafted the manuscript and all other authors revised the article for important intellectual content. All authors gave final approval of the version published.

Funding: This work was supported by a research grant provided by Edwards Lifesciences (Nyon, Switzerland) to the Sponsor, the Institute for Pharmacology and Preventive Medicine (IPPMed, Cloppenburg, Germany).

Competing interests: PB has received research funding for the present project and honoraria for consultancy from Edwards Lifesciences. NF, RPS and DM-Z have received honoraria for advisory board meetings and TKR speakers’ honoraria from Edwards Lifesciences. The institutions of these three and those of the remaining authors representing study centers have received funding for employing a study nurse.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the independent ethics review board at each participating institution. Patient informed consent was obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Frey N, Steeds RP, Rudolph TK, et al. Symptoms, disease severity and treatment of adults with a new diagnosis of severe aortic stenosis. Heart 2019;105:1709–16. 10.1136/heartjnl-2019-314940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baumgartner H, Falk V, Bax JJ, et al. 2017 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J 2017;38:2739–91. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kanwar A, Thaden JJ, Nkomo VT. Management of Patients With Aortic Valve Stenosis. Mayo Clin Proc 2018;93:488–508. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rydén L, Stokoe G, Breithardt G, et al. Patient access to medical technology across Europe. Eur Heart J 2004;25:611–6. 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dickstein K, Normand C, Auricchio A, et al. Crt survey II: a European Society of cardiology survey of cardiac resynchronisation therapy in 11 088 patients-who is doing what to whom and how? Eur J Heart Fail 2018;20:1039–51. 10.1002/ejhf.1142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benzer W, Rauch B, Schmid J-P, et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation in twelve European countries results of the European cardiac rehabilitation registry. Int J Cardiol 2017;228:58–67. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.11.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liapis CD, Avgerinos ED, Sillesen H, et al. Vascular training and endovascular practice in Europe. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2009;37:109–15. 10.1016/j.ejvs.2008.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roques F, Nashef SAM, Michel P, et al. Regional differences in surgical heart valve disease in Europe: comparison between Northern and southern subsets of the EuroSCORE database. J Heart Valve Dis 2003;12:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kapetanakis EI, Athanasiou T, Mestres CA, et al. Aortic valve replacement: is there an implant size variation across Europe? J Heart Valve Dis 2008;17:200–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dall'Ara G, Eltchaninoff H, Moat N, et al. Local and general anaesthesia do not influence outcome of Transfemoral aortic valve implantation. Int J Cardiol 2014;177:448–54. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.09.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stachon P, Zehender M, Bode C, et al. Development and In-Hospital Mortality of Transcatheter and Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement in 2015 in Germany. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:475–6. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.04.077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parma R, Dąbrowski M, Ochała A, et al. The Polish interventional cardiology TAVI survey (PICTS): adoption and practice of transcatheter aortic valve implantation in Poland. Postepy Kardiol Interwencyjnej 2017;13:10–17. 10.5114/aic.2017.66181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steeds RP, Lutz M, Thambyrajah J, et al. Facilitated data relay and effects on treatment of severe aortic stenosis in Europe. J Am Heart Assoc 2019;8:e013160. 10.1161/JAHA.119.013160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mylotte D, Osnabrugge RL, Martucci G, et al. Adoption of transcatheter aortic valve implantation in Western Europe. Interv Cardiol 2014;9:37–40. 10.15420/icr.2011.9.1.37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nguyen V, Michel M, Eltchaninoff H, et al. Implementation of transcatheter aortic valve replacement in France. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;71:1614–27. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.01.079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krasopoulos G, Falconieri F, Benedetto U, et al. European real world trans-catheter aortic valve implantation: systematic review and meta-analysis of European national registries. J Cardiothorac Surg 2016;11:159. 10.1186/s13019-016-0552-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frey N, Steeds RP, Serra A, et al. Quality of care assessment and improvement in aortic stenosis - rationale and design of a multicentre registry (IMPULSE). BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2017;17:5. 10.1186/s12872-016-0439-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rudolph TK, Messika-Zeitoun D, Frey N, et al. Caseload management and outcome of patients with aortic stenosis in primary/secondary versus tertiary care settings-design of the impulse enhanced registry. Open Heart 2019;6:e001019. 10.1136/openhrt-2019-001019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baumgartner H, Hung J, Bermejo J, et al. Recommendations on the echocardiographic assessment of aortic valve stenosis: a focused update from the European association of cardiovascular imaging and the American Society of echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2017;30:372–92. 10.1016/j.echo.2017.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katz S, Downs TD, Cash HR, et al. Progress in development of the index of ADL. Gerontologist 1970;10:20–30. 10.1093/geront/10.1_Part_1.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beckmann A, Hamm C, Figulla HR, et al. The German aortic valve registry (GARY): a nationwide Registry for patients undergoing invasive therapy for severe aortic valve stenosis. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012;60:319–25. 10.1055/s-0032-1323155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beckmann A, Meyer R, Lewandowski J, et al. German heart surgery report 2019: the annual updated registry of the German Society for thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2020;68:263–76. 10.1055/s-0040-1710569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beckmann A, Meyer R, Lewandowski J, et al. German heart surgery report 2018: the annual updated registry of the German Society for thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2019;67:331–44. 10.1055/s-0039-1693022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamm CW, Mohr F, Heusch G. Lessons learned from the German aortic valve registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:689–92. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.06.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eggebrecht H, Mehta RH. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) in Germany 2008-2014: on its way to standard therapy for aortic valve stenosis in the elderly? EuroIntervention 2016;11:1029–33. 10.4244/EIJY15M09_11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Freed BH, Sugeng L, Furlong K, et al. Reasons for nonadherence to guidelines for aortic valve replacement in patients with severe aortic stenosis and potential solutions. Am J Cardiol 2010;105:1339–42. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.12.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mylotte D, Piazza N, Serruys PW. Tavi adoption in Germany: onwards and upwards. EuroIntervention 2016;11:968–70. 10.4244/EIJV11I9A198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grant SW, Hickey GL, Ludman P, et al. Activity and outcomes for aortic valve implantations performed in England and Wales since the introduction of transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2016;49:1164–73. 10.1093/ejcts/ezv270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ludman PF, Moat N, de Belder MA, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation in the United Kingdom: temporal trends, predictors of outcome, and 6-year follow-up: a report from the UK transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) registry, 2007 to 2012. Circulation 2015;131:1181–90. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Avinée G, Durand E, Elhatimi S, et al. Trends over the past 4 years in population characteristics, 30-day outcomes and 1-year survival in patients treated with transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 2016;109:457–64. 10.1016/j.acvd.2016.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Auffret V, Lefevre T, Van Belle E, et al. Temporal Trends in Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement in France: FRANCE 2 to FRANCE TAVI. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:42–55. 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rydén A, Sörstadius E, Bergenheim K, et al. The humanistic burden of type 1 diabetes mellitus in Europe: examining health outcomes and the role of complications. PLoS One 2016;11:e0164977. 10.1371/journal.pone.0164977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dudek D, Barbato E, Baumbach A, et al. Current trends in structural heart interventions: an overview of the EAPCI registries. EuroIntervention 2017;13:Z11–13. 10.4244/EIJV13IZA3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ludman PF. Uk TAVI registry. Heart 2019;105:s2–5. 10.1136/heartjnl-2018-313510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Biagioni C, Tirado-Conte G, Rodés-Cabau J, et al. State of transcatheter aortic valve implantation in Spain versus Europe and non-European countries. J Invasive Cardiol 2018;30:301–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thourani VH, Borger MA, Holmes D, et al. Transatlantic editorial on transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2017;52:1–13. 10.1093/ejcts/ezx196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coylewright M, Mack MJ, Holmes DR, et al. A call for an evidence-based approach to the heart team for patients with severe aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65:1472–80. 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.02.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones DR, Chew DP, Horsfall MJ, et al. Multidisciplinary transcatheter aortic valve replacement heart team programme improves mortality in aortic stenosis. Open Heart 2019;6:e000983. 10.1136/openhrt-2018-000983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]