Abstract

Background

Distal radius fracture (DRF) is the most common upper extremity fracture that requires surgery. Operative treatment with a volar locking plate has proved to be the treatment of choice for unstable fractures. However, no consensus has been reached about the benefits of pronator quadratus (PQ) repair after volar plate fixation of DRF in terms of patient-reported outcome measures, pronation strength, and wrist mobility.

Methods

We searched the PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Central, and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) databases up to March 13, 2020, and included randomized-controlled, non-randomized controlled, or case-control cohort studies that compared cases with and without PQ repair after volar plate fixation of DRF. We used a random-effects model to pool effect sizes, which were expressed as standardized mean differences (SMDs) and 95% confidence intervals. The primary outcomes included Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand scores and pronation strength. The secondary outcomes included the SMDs in pain scale score, wrist mobility, and grip strength. The outcomes measured were assessed for publication bias by using a funnel plot and the Egger regression test.

Results

Five randomized controlled studies and six retrospective case-control studies were included in the meta-analysis. We found no significant difference in primary and secondary outcomes at a minimum of 6-month follow-up. In a subgroup analysis, the pronation strength in the PQ repair group for AO type B DRFs (SMD = − 0.94; 95% CI, − 1.54 to − 0.34; p < 0.01) favored PQ repair, whereas that in the PQ repair group for non-AO type B DRFs (SMD = 0.39; 95% CI, 0.07–0.70; p = 0.02) favored no PQ repair.

Discussion

We found no functional benefit of PQ repair after volar plate fixation of DRF on the basis of the present evidence. However, PQ muscle repair showed different effects on pronation strength in different groups of DRFs. Future studies are needed to confirm the relationship between PQ repair and pronation strength among different patterns of DRF.

Registration

This study was registered in the PROSPERO registry under registration ID No. CRD42020188343.

Level of evidence

Therapeutic III

Keywords: Pronator quadratus, Distal radius fracture, Volar plate, Pronation

Introduction

Distal radius fracture (DRF) is the most common upper extremity fracture that requires surgery. Operative treatment with a volar locking plate has proved to be the treatment of choice for unstable fractures [1]. The pronator quadratus (PQ) muscle resides in the fracture zone and implant placement site. Several published studies have addressed methods of preservation or repair of the PQ muscle [2–4]. A previous study surveyed all active members of the American Society for Surgery of the Hand in the USA, and 83% (608/753) responded that they attempted to repair the PQ muscle [5]. In addition, one previous biomechanical study that included healthy volunteers reported that subjects with decreased pronation torque strength had temporary pronator quadratus paralysis [6]. However, the necessity for repair of the PQ for optimal functional outcome remains controversial.

Two studies, a retrospective case-control study [7] and a prospective randomized controlled study [8], both published in 2013, compared PQ repair with no PQ repair after distal radius plating surgery. They found no significant differences in Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) and pain scale scores 1 year postoperatively. An additional prospective randomized controlled study revealed that PQ repair might reduce pain in 3 months postoperatively [9]. The most recently published randomized controlled trial concluded that PQ repair showed no significant improvement in clinical outcome 1 year after surgery [10].

To compile the best available evidence, we performed a systemic review and meta-analysis of prospective randomized controlled and retrospective case-control studies to determine whether PQ repair after distal radius plating surgery is associated with patient-reported outcome measures, pain scale score, wrist mobility, and grip and pronation strengths.

Methods

Search strategy and inclusion criteria

We conducted this study in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines [11]. We performed an electronic search in the PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Central, and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) databases up to March 13, 2020, using search strategies (Additional file 1 Appendix 1). The bibliographies of the included trials and related review articles were manually reviewed for relevant references. Two independent reviewers (CCC and CKL) evaluated the studies by screening the titles and abstracts, followed by a detailed examination of the full texts of the eligible articles. Any inconsistencies were resolved using a consensual approach. If a disagreement could not be resolved, we consulted a third reviewer (WCL) for the final decision.

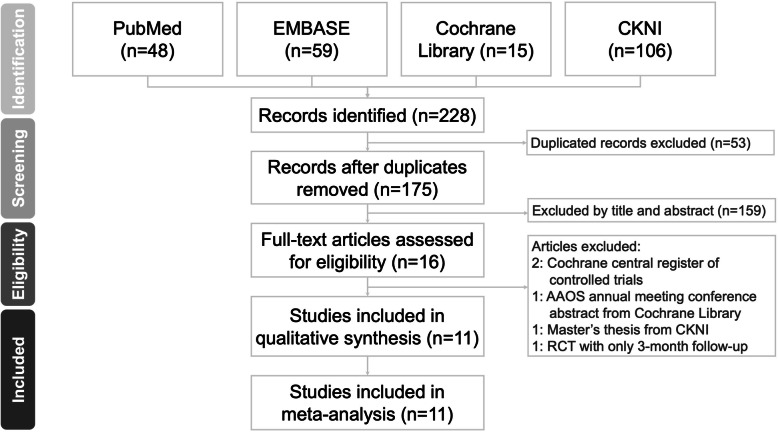

Regarding the types of studies included, we enrolled randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and comparative experimental trials. We included clinical trials that met the following criteria: (1) included a target population that was comprised of patients with DRFs treated with volar plate fixation; (2) comprised of two treatment arms after volar plate fixation, with and without PQ repair; and (3) measured the clinical outcome at least 6 months postoperatively. We excluded the following types of studies: (1) reviews, conference abstracts, or presentations, and (2) overlapping publications. We summarized the selection process in accordance with the PRISMA flowchart (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses flow diagram for searching and identifying the studies for inclusion in the analysis

Methodological quality assessment

All 12 studies were critically appraised for the assessment of their methodological qualities by two independent reviewers (WCL and CKL), which was checked by a third reviewer (CLS). We recorded the first author, year, number of fracture patterns based on the AO classification, participant characteristics, model of the volar plate, and detailed technique of the PQ repair. The methodological qualities of the enrolled studies were evaluated by two reviewers independently using the Jadad scale for RCTs [12] and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for comparative experimental trials [13]. The Jadad scale evaluates the methodology of RCTs in accordance with three aspects as follows: randomization (2 points), blinding (2 points), and an account of all patients (1 point) [12]. The five RCTs included in our study ranged had Jadad scale scores ranging from 3 to 5, with a maximum possible score of 5. Higher scores indicate better methodological quality. In evaluating case-control studies, the NOS contains nine items in three categories as follows: participant selection (four items), comparability (one item), and exposure (three items). A study can be scored a maximum of 1 point for items in the selection and exposure domains and a maximum of 2 points for the comparability domain [14]. The five case-control studies included all had a NOS score of 8, with a maximum possible score of 9. Higher scores indicate better methodological quality. Between-reviewer discrepancies were resolved through discussions under the supervision of the corresponding author. We tried to contact the primary authors of all the included studies; however, only the authors of three studies responded and provided complete original data sheets [7, 8, 10].

Meta-analysis methodology

A meta-analysis was performed using the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA) version 3 software (Biostat, Englewood, NJ, USA), thereby combining the relevant effects of interest from our identified studies.

All the outcomes were assessed within two groups after volar plate fixation of DRF as follows: PQ repair was performed in the study group but not in the control group in a minimum of 6 months after distal radius plating surgery. The standardized mean differences (SMDs) in DASH score and pronation strength between the two groups were the primary outcomes. The SMDs in wrist mobility (extension, flexion, supination, pronation, radial deviation, and ulnar deviation) and grip strength and visual analog scale score for pain between the groups were the secondary outcomes. A negative SMD value indicated that PQ repair was a favorable treatment option. Studies that did not report standard deviations (SDs) were excluded from the pooling. We also recorded any flexor complications mentioned in each included study. When the 95% confidence interval (CI) of the summary mean did not overlap, we considered it statistically significant. Between-trial heterogeneity was determined using I2 and chi-square tests [15]. A fixed-effects (inverse variance) model was used when the effects were assumed to be homogenous (p > 0.01). Statistical heterogeneity is implied when the p value was < 0.01; thus, a random-effects model was used in those circumstances. Articles that reported outcome measures were assessed for publication bias using a funnel plot [16] and the Egger regression test [17].

Results

Literature search and study characteristics

We retrieved 175 non-duplicate citations and reviewed their titles and abstracts, and included 15 articles for meticulous evaluation after eliminating references that did not meet the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). We excluded two studies from the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials database, one master’s thesis, which is a review article from the CNKI database, and one RCT that compared PQ repair with no PQ repair with only 3 months of follow-up. Therefore, the meta-analysis included five RCTs [8, 10, 18–20] and six retrospective case-control studies [7, 21–25].

A total of 732 patients were included along with a breakdown of the numbers of patients, mean ages, and sex ratios in comparison groups, except for two studies. Patient sex data and mean patient age were well recorded in all the studies. The mean ages of the patients ranged from 48.7 to 64.0 years in the group with PQ repair and from 47.1 to 63.6 years in the group without PQ repair. The female-to-male ratio in each study was well proportioned between the two study groups. The mean patient age and sex ratio were also comparable in all the studies. The details of each study are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of the retrieved studies that compared between with and without pronator quadratus repair after distal radius fracture volar plating surgery

| Study (author, year) | Study design | Sex (M/F) | Fracture stage (A/B/C) | Mean age, years | Blinding | Randomization | Outcome measures | Follow-up timing | Country | Quality assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Si, 2012 | RCS |

R: 15 (3/12) NR: 15 (5/10) |

R: 0/15/0 NR: 0/15/0 |

R: 57.6 (35–70) NR: 56.3 (48–70) |

NA | NA | DASH and ROM | 3 days, 1 month, and 6 months | China | 8# |

| Hershman, 2013 | RCS |

R: 62 (29/33) NR: 50 (21/29) |

R: 13/10/29 NR: 17/12/21 |

R: 53.8 (4) NR: 51.6 (4.5) |

NA | R: hand fellow; NR: trauma fellow | DASH, VAS score, grip strength, and ROM | 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months | USA | 8# |

| Tosti, 2013 | RCT |

R: 33 (9/24) NR: 24 (4/20) |

R: 8/1/24 NR: 2/1/21 |

R: 51 (18.9) NR: 60 (13.7) |

Double | Year of birth | DASH, VAS, ROM, and grip strength | 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 3 months, and 12 months | USA | 3* |

| Qian 2017 | RCS |

R: 43 (NA) NR: 40 (NA) |

R: 0/21/22 NR: 0/20/20 |

R & NR: 52.2 (23–72) | NA | NA | DASH, ROM, and pronation/supination power | 13 months (11–19 months) | China | 8# |

| Hohendorff, 2018 | RCT |

R: 20 (4/16) NR: 16 (6/10) |

R: 14/0/6 NR: 8/1/7 |

R: 64 (18–77) NR: 54 (18–80) |

NA | Blinded envelope | DASH, VAS, ROM, grip strength, and pronation power | 12 months | Germany | 4* |

| Wang, 2018 | RCS |

R: 25 (4/21) NR: 20 (4/16) |

R: 0/12/13 NR: 0/8/12 |

R: 53.6 NR: 57.8 |

NA | NA | DASH, VAS, and ROM | 6 weeks and 6 months | China | 8# |

| Zhang, 2018 | RCT |

R: 45 (29/16) NR: 45 (30/15) |

R: 5/22/18 NR: 6/19/16 |

R: 55.7 (3.4) NR: 54.1 (2.4) |

Double | Admission sequence | VAS and ROM | 1 day, 3 days, 1 month, and 6 months | China | 2* |

| Cang, 2019 | RCS |

R: 37 (NA) NR: 23 (NA) |

R: 0/18/19 NR: 0/12/11 |

R & NR: 40.9 (5.0) | NA | NA | ROM, DASH and pronation/supination power | 10.5 months (6–15 months) | China | 8# |

| Chao, 2019 | RCT |

R: 42 (13/29) NR: 42 (15/27) |

R: 9/25/8 NR: 7/24/11 |

R: 48.7 (7.7) NR: 47.1 (8.5) |

Single | Undescribed method | DASH, VAS, ROM, and grip strength | 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 3 months, and final (11–15 months) | China | 2* |

| Pathak, 2019 | RCS |

R: 29 (11/18) NR: 34 (13/21) |

R & NR: A2–C2 |

R: 54.9 (24–77) N: 48.6 (22–72) |

NA | NA | DASH, VAS, ROM, and grip strength | 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, and final (R: 35.2; NR: 38.6) | India | 8# |

| Sonntag, 2019 | RCT |

R: 36 (5/31) NR: 36 (10/26) |

R: 22/0/12 NR: 19/1/13 |

R: 62.0 (10.8) NR: 63.6 (15.6) |

Double | Randomized allocation sequence | DASH, PRWE, ROM, pronation, and grip strength | 2 weeks, 5 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months | Denmark | 5* |

RCS retrospective case-control study, RCT randomized controlled trial, R repair, NR non-repair, NA not applicable, DASH Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand, ROM range of motion, VAS visual analog scale, MWS Mayo wrist score, PRWE patient-rated wrist evaluation

#The study was assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale score

*The study was assessed using the Jadad scale score

For pronation strength measurement, two studies [10, 18] used a baseline hydraulic wrist dynamometer (Fabrication Enterprises), and another two studies [25] used a hand dynamometer (Qianli, China). For grip strength measurement, three studies [8, 10, 18] used a dynamometer (Jamar; Therapeutic Equipment, Clifton, NJ) and two studies [7, 19] did not mention the hand dynamometer model used. One study [8] provided grip strength data in comparison with those of the uninjured side instead of the actual measured values.

Most studies presented the number of fractures in each AO Foundation/Orthopaedic Trauma Association (AO/OTA) fracture classification [26], except one study [23] that did not report the included fracture types. Two studies analyzed the outcomes of patients with DRF AO/OTA types B and C [22, 25] with or without PQ repair instead of the pooled outcomes. We divided these two studies into two sub-studies for the statistical analysis.

Surgical procedure and postoperative management

All the internal fixation surgeries were performed using the modified volar approach of Henry. Among the included studies, different types of volar plate, methods of PQ repair, and postoperative management strategies were used. We summarized them in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of the surgery and postoperative management details of the retrieved studies

| Study (author, year) | Plate | PQ repair method | Postoperative management |

|---|---|---|---|

| Si, 2012 | Unknown VLP | Direct interrupted (absorbable 2-0) | Physical therapy in 2 days |

| Hershman, 2013 | Stryker and Synthes VLP | NA | Splint for 2 weeks, full weight bearing in 6 weeks |

| Tosti, 2013 | Medartis (VA) and Synthes (VA) VLP | Figure-of-eight (Vicryl 2-0) | Immobilization for 2 weeks and then start of physical therapy |

| Qian 2017 | Synthes VLP | Figure-of-eight (Vicryl 3-0) | NA |

| Hohendorff, 2018 | Stryker (VA) VLP | PQ to BR (PDS 4-0) | Splint for 2 weeks and unlimited mobility in 4 weeks |

| Wang, 2018 | NA | Figure-of-eight (absorbable 4-0) | Physical therapy in 2 days |

| Zhang, 2018 | Unknown VLP | Direct interrupted (absorbable 2-0) | Physical therapy in 2 days |

| Cang, 2019 | Synthes VLP | Figure-of-eight (absorbable 3-0) | NA |

| Chao, 2019 | NA | Direct interrupted (absorbable 3-0) | Physical therapy in 1 weeks |

| Pathak, 2019 | NA | Direct interrupted (Vicryl 3-0) | Immobilization for 1–2 weeks and then start of physical therapy |

| Sonntag, 2019 | Stryker (VA), Synthes (VA) | Continuous with a minimum of four sutures (Vicryl 3-0) | Splint for 2 weeks and gradual weight bearing |

PQ pronator quadratus, NA not applicable, VLP volar locking plate, VA variable angle, PDS polydioxanone

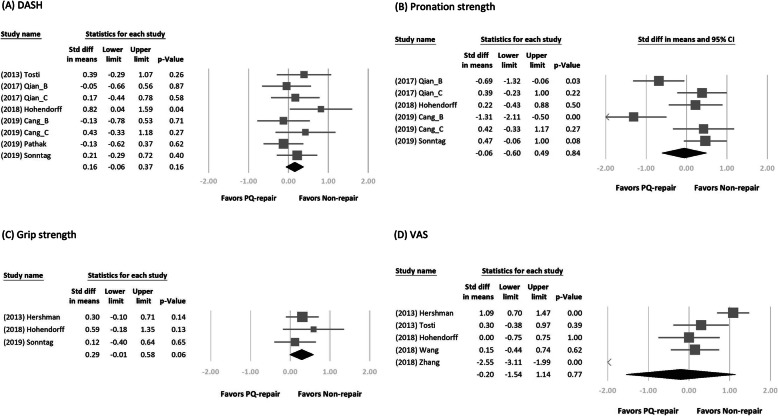

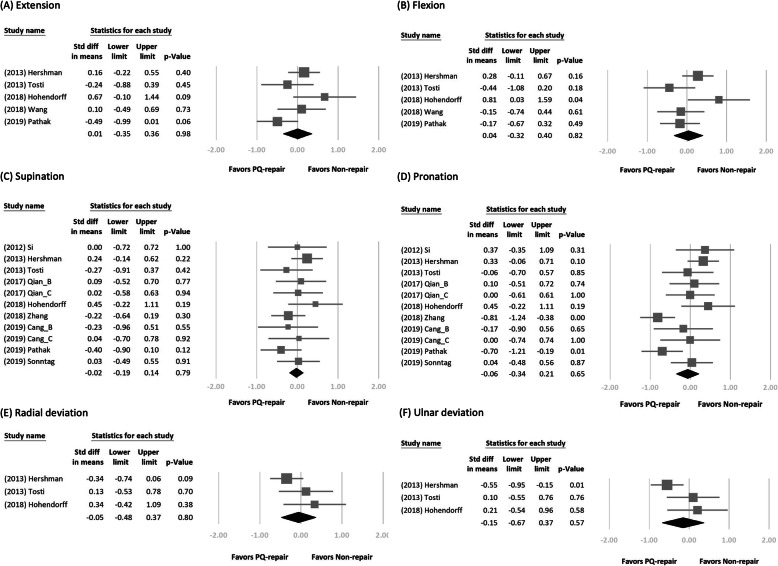

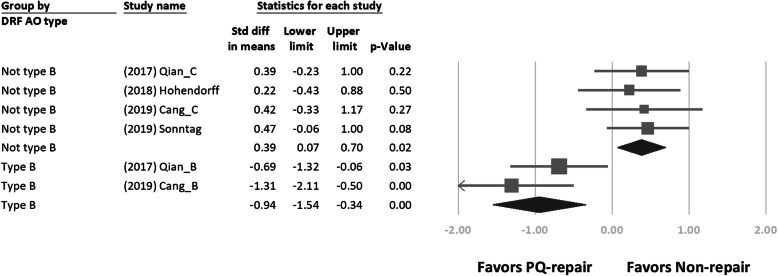

Meta-analysis of the outcomes

We retrieved the long-term follow-up outcome from each study. Figures 2 and 3 show the forest plot of the different clinical outcomes between the two groups. We demonstrated the pooled mean of the outcomes in Table 3. No significant difference in each outcome was found between the two treatment arms. In a subgroup analysis of DRFs of AO type B or non-type B, we found a significant difference in pronation strength between the two treatment arms (SMD = − 0.94; 95% CI, − 1.54 to − 0.34; p < 0.01, favoring PQ repair in the type B group vs SMD = 0.39; 95% CI, 0.07–0.70; p = 0.02, favoring PQ repair in the non-type B group; Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

Forest plots of the standardized mean differences in functional outcome, wrist strength, and pain score. Forest plots of the standardized mean differences in a Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand score, b pronation strength, c grip strength, and d visual analog scale score for pain between the two treatment arms

Fig. 3.

Forest plots of the standardized mean differences in wrist mobility. Forest plots of the standardized mean differences in wrist mobility between the two treatment arms: a extension, b flexion, c supination, d pronation, e radial deviation, and f ulnar deviation

Table 3.

Summary of the outcomes by meta-analysis

| With PQ repair | Without PQ repair | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pooled estimate | 95% CI | n | Pooled estimate | 95% CI | n | |

| DASH | 24.73 | 16.22–33.25 | 8* | 22.15 | 9.86–34.44 | 8* |

| Pronation strength (kg cm) | 50.70 | 44.32–67.08 | 6* | 57.39 | 40.32–74.45 | 6* |

| Grip strength (kg) | 32.63 | 19.86–45.39 | 3 | 32.86 | 19.77–45.94 | 3 |

| VAS | 1.39 | 0.89–1.89 | 5 | 1.61 | 0.40–2.81 | 5 |

| Extension (degrees) | 62.84 | 45.09–80.59 | 6 | 63.94 | 52.31–75.57 | 6 |

| Flexion (degrees) | 62.18 | 48.99–75.36 | 6 | 63.23 | 53.05–73.41 | 6 |

| Supination (degrees) | 68.12 | 53.82–82.42 | 11* | 68.66 | 53.63–83.69 | 11* |

| Pronation (degrees) | 62.86 | 52.24–73.24 | 11* | 63.00 | 52.36–73.64 | 11* |

| Radial deviation (degrees) | 19.07 | 16.52–21.62 | 3 | 20.67 | 18.95–22.39 | 3 |

| Ulnar deviation (degrees) | 31.42 | 25.60–37.25 | 3 | 33.98 | 31.45–36.51 | 3 |

PQ pronator quadratus, SMD standardized mean difference, CI confidence interval, DASH Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand, VAS visual analog scale for pain

*Presented outcomes separately for AO type B and C fractures, which we counted as two studies

Fig. 4.

Forest plots of the standardized mean differences in pronation strength. Forest plots of the standardized mean differences in pronation strength between the two treatment arms for AO type B distal radius fractures

The Egger test revealed no significant publication bias regarding most clinical outcomes except radial deviation range of motion (t = 39.2, df = 1, p = 0.02; Table 4).

Table 4.

Results of the Egger test for each outcome

| t | df | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DASH | 2.08 | 6* | 0.082 |

| VAS | 0.15 | 3 | 0.891 |

| Extension | 0.27 | 3 | 0.802 |

| Flexion | 0.09 | 3 | 0.931 |

| Supination | 0.05 | 9* | 0.958 |

| Pronation | 0.70 | 9* | 0.500 |

| Radial deviation | 39.2 | 1 | 0.016 |

| Ulnar deviation | 9.29 | 1 | 0.068 |

| Grip strength | 0.64 | 1 | 0.637 |

| Pronation strength | 1.36 | 4* | 0.244 |

DASH Disability of Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand score, VAS visual analog scale

*Presented outcomes separately for AO type B and C fractures, which we counted as two studies

Discussion

With the popularity of the volar locking plate in the management of unstable DRFs, demonstrable repair of the PQ muscle postoperatively has become an issue. The PQ consists of a superficial head, which acts on forearm pronation, and a deep head, which is a dynamic stabilizer of the distal radioulnar joint [27]. As noted, a clinical study in healthy volunteers demonstrated that pronation strength decreased by 21% after the PQ muscle was anesthetized [6]. However, most clinical studies that compared cases with and without PQ repair after distal radius volar plating surgery did not show this significant difference.

Regarding pronation strength, two studies showed that the pronation strength in the group without PQ repair decreased significantly only in the patients with AO/OTA type B fractures but not in those with AO/OTA type C fractures [22, 25]. One study included patients with AO/OTA type A2, A3, and C1 fractures [18], while another study included patients with AO/OTA type A2, A3, C1–3 fractures [10]. Having better repair quality with preoperatively intact and nicely prepared PQ flaps seems logical. Although the durability of PQ repair has been supported [5], ensuring good-quality repair, especially in comminuted DRFs with frayed PQ muscles, is sometimes difficult. Two RCTs routinely checked the length or retraction of the PQ in ultrasonography examinations [10, 18]. In our included studies, patients in the group without PQ repair who had more metaphyseal displaced and complex fracture patterns had better pronation strengths (Fig. 4). However, a retrospective study showed that the completeness of PQ repair did not influence wrist mobility and grip strength [28]. More evidence is needed to confirm the relationship between the quality of PQ repair and pronation strength among different patterns of DRF.

The reliability and validity of the DASH questionnaire in the German, Chinese, and Danish versions have been confirmed [29–31]. Fracture classification might influence clinical outcomes. We found that most studies included patients with similar distributions of AO/OTA types A, B, and C. As a result, this factor was controlled within each group. The other factor is postoperative treatment. Each study had a different postoperative treatment. An RCT found that patients starting wrist mobilization 2 or 6 weeks after volar plate fixation of the distal radius did not influence the patient-reported outcome measures, grip strength, and wrist mobility at 6 and 12 months [32]. Although each study used varied postoperative treatments, we could assume that it did not influence the postoperative outcome in a minimum of 6 months for quantitative calculation.

This systematic review is limited by the sample size and quality of the available studies. To compensate for limiting the research articles in English, we conducted an extensive search strategy in most available databases, including CNKI, to ensure that all potentially relevant papers were identified and reviewed. The measurement tools for grip and pronation strength varied greatly in the included studies, which could influence the data quantification. Finally, three authors provided raw data, making up for the missing items in the included studies [7, 8, 10].

One potential benefit of PQ repair is that it enables the separation of the volar plate from the flexor tendon, which might prevent complications such as flexor tendon irritation or rupture. A systematic review revealed that the median interval between surgery and flexor tendon rupture was 9 months (interquartile range, 6–26 months) [33]. A cohort study included 451 patients with a mean follow-up of 3.2 years. The flexor tendon rupture rate was only 1.1% [34]. In the studies included in our analysis, no flexor tendon rupture was found in each group. The discrepancy in the literature may be attributed to the difference in follow-up duration. We could not conclude whether PQ repair is a protective factor against flexor complications. Future studies with longer follow-up periods are needed to compare between with and without PQ repair.

Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis found no significant differences between the groups with and without PQ repair in terms of DASH score, pronation strength, pain score, wrist mobility, and grip strength at a minimum of 6-month follow-up after volar plating surgery for DRF. However, PQ muscle repair showed different effects on pronation strength among the different DRF groups. Future studies are needed to confirm the relationship between PQ repair and pronation strength among the different DRF patterns.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Rick Tosti, Stuart Hershman, Igor Immerman, and Jesper Sonntag for providing us their original data sheets for the completion of this meta-analysis. We appreciate Chih-Wei Hsu for his support in reviewing the structure of this project as well.

Abbreviations

- AO/OTA

AO Foundation/Orthopaedic Trauma Association

- CI

Confidence interval

- DASH

Disability of Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand score

- DRF

Distal radius fracture

- NOS

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

- PQ

Pronator quadratus

- RCT

Randomized controlled trial

- SMD

Standardized means difference

- VAS

Visual analog scale for pain

Authors’ contributions

Each author is expected to have made substantial contributions to the conception. WCL designed of the work; CCC and CLS made the acquisition and analysis; CLS made the data interpretation; CKL and WCL have drafted the work; and YCF and JBJ substantively revised it. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s13018-020-01942-w.

References

- 1.Saving J, et al. External fixation versus volar locking plate for unstable dorsally displaced distal radius fractures-a 3-year follow-up of a randomized controlled study. J Hand Surg Am. 2019;44(1):18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2018.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galmiche C, et al. Minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis for extra-articular distal radius fracture in postmenopausal women: longitudinal versus transverse incision. J Wrist Surg. 2019;8(1):18–23. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1667305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee DY, Park YJ, Park JS. A meta-analysis of studies of volar locking plate fixation of distal radius fractures: conventional versus minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis. Clin Orthop Surg. 2019;11(2):208–219. doi: 10.4055/cios.2019.11.2.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cannon TA, et al. Pronator-sparing technique for volar plating of distal radius fractures. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39(12):2506–2511. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2014.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swigart CR, et al. Assessment of pronator quadratus repair integrity following volar plate fixation for distal radius fractures: a prospective clinical cohort study. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(9):1868–1873. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McConkey MO, et al. Quantification of pronator quadratus contribution to isometric pronation torque of the forearm. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34(9):1612–1617. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hershman SH, et al. The effects of pronator quadratus repair on outcomes after volar plating of distal radius fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2013;27(3):130–133. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e3182539333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tosti R, Ilyas AM. Prospective evaluation of pronator quadratus repair following volar plate fixation of distal radius fractures. J Hand Surg Am. 2013;38(9):1678–1684. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Häberle S, et al. Pronator quadratus repair after volar plating of distal radius fractures or not? Results of a prospective randomized trial. Eur J Med Res. 2015;20:93. doi: 10.1186/s40001-015-0187-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sonntag J, et al. No effect on functional outcome after repair of pronator quadratus in volar plating of distal radial fractures: a randomized clinical trial. Bone Joint J. 2019;101-b(12):1498–1505. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.101b12.Bjj-2019-0493.R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liberati A, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jadad AR, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(9):603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun L, et al. Prognostic value of pathologic fracture in patients with high grade localized osteosarcoma: a systemic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. J Orthop Res. 2015;33(1):131–139. doi: 10.1002/jor.22734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.JJ, D., H. JPT, and A. DG, Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 10.10.2. 2nd ed. 2019: Chichester (UK): John Wiley & Sons.

- 16.Sterne JA, Egger M. Funnel plots for detecting bias in meta-analysis: guidelines on choice of axis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(10):1046–1055. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00377-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peters JL, et al. Comparison of two methods to detect publication bias in meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006;295(6):676–680. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.6.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hohendorff B, et al. Pronator quadratus repair with a part of the brachioradialis muscle insertion in volar plate fixation of distal radius fractures: a prospective randomised trial. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2018;138(10):1479–1485. doi: 10.1007/s00402-018-2999-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chao Y, et al. The effect of repairing pronator quadratus after distal radius fracture plating surgery [in Chinese] J Practical Orthopaedics. 2019;25(11):1015–1018. doi: 10.13795/j.cnki.sgkz.2019.11.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Y, et al. Clinical effect of palmar locking plate combined with repair of pronator quadratus muscle in the treatment of distal radius fracture [In Chinese] Medical Innovation of China. 2018;15(14):111–115. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-4985.2018.14.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Si W, Qin W, Hao Y. Middle-term clinical effect of pronator quadratus after volar plate of a distal radius fracture [in Chinese] J Pracitcal Orthopaedics. 2012;18(11):973–975. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qian Z. Comparison the functional recovery of repairing pronator quadratus or not after internal fixation of distal radius fractures [in Chinese]. Chines Journal of Hand Surgery. 2017:33(2). 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1005-054X.2017.02.027.

- 23.Pathak S, et al. Do we really need to repair the pronator quadratus after distal radius plating? Chin J Traumatol. 2019;22(6):345–349. doi: 10.1016/j.cjtee.2019.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang H, Li Q. Analysis of functional effect of repairing pronator quadratus muscle after operation for distal radius [in Chinese] Shannxi Med J. 2018;47(9):1164–1170. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-7377.2018.09.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cang T, Li Y. The effect of repairing of the pronator quadratus on postoperative hand function druing open reduction and internal fixation of distal radius fractures [in Chinese] Chinese Journal of Clinical Rational Drug Use. 2019;12(32):190–191. doi: 10.15887/j.cnki.13-1389/r.2019.32.118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marsh JL, et al. Fracture and dislocation classification compendium - 2007: Orthopaedic Trauma Association classification, database and outcomes committee. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21(10 Suppl):S1–133. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200711101-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stuart PR. Pronator quadratus revisited. J Hand Surg Br. 1996;21(6):714–722. doi: 10.1016/s0266-7681(96)80175-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahsan ZS, Yao J. The importance of pronator quadratus repair in the treatment of distal radius fractures with volar plating. Hand (N Y) 2012;7(3):276–280. doi: 10.1007/s11552-012-9420-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen H, et al. Validation of the simplified Chinese (Mainland) version of the Disability of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand questionnaire (DASH-CHNPLAGH) J Orthop Surg Res. 2015;10:76. doi: 10.1186/s13018-015-0216-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Offenbacher M, et al. Validation of a German version of the ‘Disabilities of Arm, Shoulder and Hand’ questionnaire (DASH-G) Z Rheumatol. 2003;62(2):168–177. doi: 10.1007/s00393-003-0461-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schonnemann JO, et al. Reliability and validity of the Danish version of the disabilities of arm, shoulder, and hand questionnaire in patients with fractured wrists. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2011;45(1):35–39. doi: 10.3109/2000656X.2011.554708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lozano-Calderon SA, et al. Wrist mobilization following volar plate fixation of fractures of the distal part of the radius. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(6):1297–1304. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Asadollahi S, Keith PP. Flexor tendon injuries following plate fixation of distal radius fractures: a systematic review of the literature. J Orthop Traumatol. 2013;14(4):227–234. doi: 10.1007/s10195-013-0245-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thorninger R, et al. Complications of volar locking plating of distal radius fractures in 576 patients with 3.2 years follow-up. Injury. 2017;48(6):1104–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2017.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.