Abstract

Background and Aims

Patient-reported outcome measures are increasingly important in daily care and research in inflammatory bowel disease [IBD]. This study provides an overview of the content and content validity of IBD-specific patient-reported outcome measures on three selected constructs.

Methods

Databases were searched up to May 2019 for development and/or content validity studies on IBD-specific self-report measures on health-related quality of life, disability, and self-report disease activity in adults. Evidence was synthesised on content validity in three aspects: relevance, comprehensiveness, and comprehensibility following the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments methodology. Questionnaire items were organised in themes to provide an overview of important aspects of these constructs.

Results

For 14/44 instruments, 25 content validity studies were identified and 25/44 measures had sufficient content validity, the strongest evidence being of moderate quality, though most evidence is of low or very low quality. The Crohn’s Life Impact Questionnaire and IBD questionnaire-32 on quality of life, the IBD-Control on disease activity, and the IBD Disability Index Self-Report and its 8-item version on disability, have the strongest evidence of sufficient relevance, comprehensiveness, and comprehensibility, ranging from moderate to very low quality. A fair number of recurring items themes, possibly important for the selected constructs, was identified.

Conclusions

The body of evidence for content validity of IBD-specific health-related quality of life, self-report disease activity, and disability self-report measures is limited. More content validity studies should be performed after reaching consensus on the constructs of interest for IBD, and studies should involve patients.

Keywords: Content validity, patient-reported outcome measures, inflammatory bowel diseases

1. Introduction

The main types of inflammatory bowel disease [IBD], ulcerative colitis [UC] and Crohn’s disease [CD], are lifelong diseases with relapsing and remitting characteristics of varying intensity. They often have a significant impact on health status and quality of life, by affecting physical and emotional well-being and by impairment of social and functional abilities.1–3

The World Health Organization defines health as ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’ and quality of life as ‘an individual’s perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns. It is a broad ranging concept affected in a complex way by the person’s physical health, psychological state, personal beliefs, social relationships and their relationship to salient features of their environment’ 4,5 In light of these general definitions, focusing on physical health as a treatment target alone will not suffice in restoring health and quality of life.

Patient-reported outcome measures [PROMs] can be used to monitor these unobservable constructs such as quality of life. A PRO is any report of the status of a patient’s health condition that comes directly from the patient, without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else.6

IBD-related PROMs measuring health status or health-related quality of life [Hr-QoL] are now commonly used as secondary or co-primary endpoints in medical trials.6–8 Many of the commonly used PROMs were developed prior to the Food and Drug Administration [FDA] guidance for the use of PROMs in drug labelling claims, which also specified recommendations for their development and validation.6 Currently applied PROMs might not meet these recommendations.

Apart from the need for PROMs in new drug development, the pairing or replacement of direct measurements of physical health with PROMs bridges biological disease aspects with patient experience. Structured implementation of PROMs, beyond trials, in daily care or health registries has been proposed but so far has not widely been implemented.9,10

One obstacle in standardising the use of PROMs is the lack of consensus regarding relevant outcomes and the most suitable PROMs to be used to assess those outcomes in IBD.11–16 Core Outcome Sets [COS] are minimally required sets of outcomes, agreed to be important for a specific population [e.g., in research or daily practice]. They are important to synchronise outcomes across different research projects or populations, but also to standardise the definitions used for the constructs that we elect to measure for our outcomes. Several organisations, such as the Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials [COMET] initiative17 and COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments [COSMIN],18 have proposed methodologies for COS development and provide platforms for interested parties to initiate new projects. Few COS for IBD populations have been defined17 and work is under way to develop new ones.19

Overall, the intensified applications of PROMs in IBD research and clinical care call for further evidence on their reliability, validity, and responsiveness. Content validity is considered to be the most important measurement property, because it should be clear that the items of the PROM are relevant, comprehensive, and comprehensible with respect to the construct of interest and study population. Multiple reviews have been published evaluating measurement properties of IBD-specific PROMs.20–22 However, no work has been published focusing on the content validity of IBD-specific PROMs. Therefore we performed a systematic review on content validity studies according to the COSMIN guideline for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures.23

The aim of this study is to provide an overview of the content [i.e., included items] and content validity of all IBD-specific patient-reported outcome measures focusing on health-related quality of life, disability, and self-report disease activity.

2. Methods

A systematic review was performed in accordance with the PRISMA [Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses] statement.24 The primary methodology and inclusion criteria were published in a protocol in the PROSPERO database under registration number CRD42017065282. After initial screening, the scope of the review was narrowed to specifically assess the content validity, including the development processes, and item content of IBD-specific instruments measuring the constructs: health-related quality of life, disability, and self-report disease activity. The COSMIN checklist25 was replaced by its updated version: the COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist26,27 and the COSMIN guideline for systematic reviews of PROMs.23 Full amendments to the protocol can be reviewed in the PROSPERO database.

Basic concept definitions of the three chosen constructs were formulated as the starting point for the review, in order to structure the evaluation of item content and to assess and compare content validity of various PROMs within their concept. This broad approach was chosen to be inclusive of all PROMs regardless of their given definitions or conceptual models [e.g., in Hr-QoL the Wilson and Cleary conceptual model28 or Needs-based model29] on which they were based, as no consensus has been reached regarding the preferred core domains or operationalisation of Hr-QoL, disability, and self-report disease activity in IBD. 1]

‘Health-related quality of life’ encompasses an individual’s perception of well-being on multiple fronts in life, and items must at least represent physical, emotional, and social aspects of IBD. 2] ‘Disability’ encompasses an individual’s perception of decreased function compared with a norm, and items must at least represent physical, emotional, social, and function-related [e.g., education, work, or house work] aspects of IBD. 3] ‘Self-report disease activity’ encompasses an individual’s perception of impaired bodily functions and/or symptoms caused by IBD, which is expressed in both intestinal [including IBD-specific extra-intestinal manifestations] and systemic physical aspects such as sleep, appetite, and energy.

2.1. Eligibility criteria

Instruments specifically designed for IBD populations with only self-report items were included. All studies on measurement properties and development of instruments [including concept elicitation studies] were eligible in the screening phase. The population criteria were: patients 18 years and older with inflammatory bowel diseases, including Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and IBD-unclassified.

Original articles were selected in full text if they reported studies on the PROM development or content validity of [translated] PROMs and the authors stated they intended to measure ‘health-related quality of life’ or ‘health status’, any form of ‘disability’, or ‘self-report disease activity’. Through snowballing, any concept elicitation study or study that could be viewed as a development study [from originally clinician-reported, generic, or composite instruments] relevant to the development of an included PROM, was also eligible for inclusion.

Publication language was no restriction if Google Translate could provide an adequate translation. New PROMs developed by analysing retrospective data from items with the potential to be self-reported items from originally clinician-reported, generic, or composite measures, were excluded if no prospective self-reported validation took place. Studies including children were excluded.

2.2. Literature search

MEDLINE via Pubmed, EMBASE via Ovid and Embase.com, and PsycINFO via Ebsco were searched from inception up to 5 July, 2017. An update was performed to include later publications up to 15 May, 2019. A sensitive search strategy was developed in cooperation with an experienced information specialist, and consisted of four groups of search terms. These four components were adaptations from previously developed building blocks published on [www.bmi-online.nl], and represented the following subjects: 1] inflammatory bowel diseases; 2] patient-reported outcomes measures; 3] clinimetric studies; and 4] diagnostic test validation. For the full query see Supplementary Data 1, available at ECCO-JCC online.

2.3. Study selection

The search results were combined in Refworks [www.refworks.com] and duplicates were removed. The remaining studies were exported into Covidence [www.covidence.org], where further missed duplicates were removed. Two independent reviewers [EA and BK or FC] screened all abstracts for eligibility for full-text evaluation; disputed abstracts were discussed in a face-to-face meeting and, if no consensus could be reached, a third reviewer [DA] made the final decision. The same process was used for the full-text screening. Reference lists of full-text articles were also screened for additional articles. If additional unpublished information was necessary for inclusion or analysis of the PROM characteristics, the corresponding author was contacted once to request the data.

Data collection and evidence synthesis were performed by EA. Data on population characteristics, language, country, target population, construct definitions, medical setting, and recall period were collected on piloted forms. Data on study quality and evidence synthesis for content validity were entered into an Excel spreadsheet provided by COSMIN via their website [www.cosmin.nl].

2.4. Item content

Items from all included PROMs were organised according to [our perception of] four domains, which are represented in our broad definitions of the included constructs: physical aspects, emotional aspects, social aspects, and function-related aspects. Items that did not fit in any of the four domains were grouped under miscellaneous themes. Physical aspects include items referring to bodily functions, symptoms, or impairments. Emotional aspects include items on emotions, worries, and cognitive functions. Social aspects refer to interaction with friends/family/support and implied ‘social’ encounters. Function-related aspects refer to items on functioning at home, travel, work, or school, or in performing leisure activities [other than implied ’social’ encounters]. Items with very similar themes but different wording were grouped. Items addressing multiple themes in a single item could be tabulated per theme as a fraction. For example, one item referring to both worry and anxiety was tabulated as 1/2 for worry and 1/2 for anxiety, instead of adding another theme on the combination of worry and anxiety. PROMs with multiple items on the same theme were tabulated with a number representing the frequency with which the theme occurred. The frequency of items per instrument and across all instruments was calculated.

2.5. Evaluation of content validity

The COSMIN group has developed standards and criteria for the evaluation of measurement properties of PROMs. Standards refer to design requirements and preferred statistical methods for evaluating the methodological quality of studies [risk of bias] on measurement properties. Standards are rated on a 4-point rating scale from ‘very good’ to ‘inadequate’.25 Per measurement property, the standards are summarised according to the ‘worst score counts’ principle, to give a rating for the quality of the study. Criteria refer to what constitutes good measurement properties [quality of PROMs].23

First, standards for development studies regarding concept elicitation and available qualitative studies are applied, followed by standards for content validity studies in five categories: relevance and comprehensiveness studied by professionals, and relevance, comprehensiveness, and comprehensibility studies in target populations.

Second, 10 criteria for good measurement properties are applied per available development and content validity study, on the aspects of relevance, comprehensiveness, and comprehensibility. Each criterion is scored as sufficient [+], insufficient [-], or indeterminate [?], and is summarised per aspect with the addition of an inconsistent [±] rating option. The reviewer applied the same criteria to rate the content of the PROM from the perspective of the broad definitions used as a starting point for the review.

Third, available ratings from the second step are added together per PROM, to provide an overall rating per aspect as sufficient [+], insufficient [-], inconsistent [±], or indeterminate [?]. When rating content validity of modified versions of a PROM, the original’s development process is used, paired with the evidence from the modification process, content validity studies, and a rating by the reviewer to the specific modified version.27

Overall ratings [per PROM] for each aspect of content validity were evaluated for quality of evidence according to a modified Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation [GRADE] approach.23 Assuming the quality of evidence is high, it is downgraded based on risk of bias, inconsistency, or indirectness. It ranges from high quality of evidence from at least a content validity study of adequate quality, to very low quality from an inadequate development study with either inadequate content validity studies or the absence of such studies. In PROMs with only development or content validity studies with indeterminate ratings, the overall rating is solely based on the rating provided by the reviewer.

Following alterations of the number of items, response options, or subscales, the resulting scales are considered modified unique instruments, with a similar base for development. Further details on the COSMIN methodology can be found in the user manuals.23,26,27

3. Results

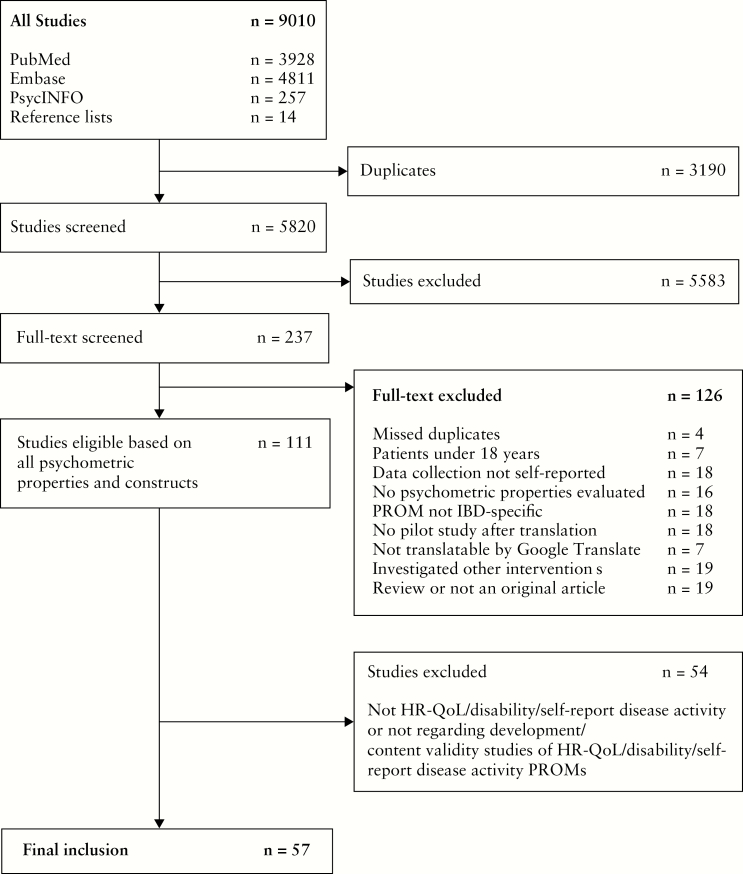

The search strategy yielded 5820 articles, after removal of duplicates. Of 237 articles selected for full-text review, 57 articles were included representing 44 unique PROMs, including 28 ‘original’ PROMs and 16 modified versions. Nine of these 57 articles regarded clinician-administered and/or composite instruments that were considered a part of the development process for their modified self-report sequels, and were therefore included.30–38 The selection process is depicted in Figure 1. In all selection stages, a consensus for eligibility was reached between the two independent reviewers.

Figure 1.

Inclusion flowchart.

3.1. PROM characteristics

The PROM characteristics such as the provided construct definitions, target populations, subscales, and range of scores are represented in Table 1. Of all 44 instruments seven report to measure some concept of disability: two on perceived work disability39,40and the rest on a form of disease-related disability.41–45 Eighteen PROMs could be categorised as measuring self-reported disease activity. This includes eight PROMs measuring ‘UC disease activity’ 46–52 and one predicting mucosal inflammation in UC.53 Four PROMs report to measure ‘CD disease activity’ 51,54–56 and one predicts mucosal inflammation in CD.53 The remaining four of 18 report to measure ‘IBD disease activity’ 57,58 or ‘disease control’ in IBD patients.59 Nineteen PROMs report to measure a concept of ‘health-related quality of life’, ‘health status’, or ‘disease burden’. The IBDQ-3260–66 reports to be a health status measure for IBD patients, though its modified versions67–74 also report to be Hr-QoL measures and, if a construct definition was provided, it varied per modification. Five other PROMs also report to measure Hr-QoL in IBD patients.75–79 Some of the Hr-QoL instruments are validated for UC patients, two measuring health status80,81 and one Hr-QoL,82 and three PROMs are CD-specific and report to measure health status,80 HR-QoL,83 and disease burden.84

Table 1.

PROM characteristics - Disability.

| PROM (Abbr.) | Primary language | Construct description | Target pop. | Intended context of use | Recall period | Response options | (sub)scale(s) (number of items) | Range of scores (worst-best) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IBD Disability Scale (IBD-DS)41 | English (AUS) | Limitations and restrictions to normal activity that a patient may experience because of disease, expressed in impaired body function and structures, activity limitation, participation restriction and interaction with environmental factors. | IBD | clinical practice and social services | 1 month | 5-level Likert and yes/no | Total score (58) Mobility (?) Self-care (?) Major life activities (?) Gastrointestinal-related symptoms (?) Mental-related symptoms (?) Enviromental-related issues (?) Support? (?) | NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA |

| Crohn's Perceived Work Disability Questionnaire (CPWDQ)39 | Spanish (ES) | Disability is partial or total inability to perform social roles such as work activity in a manner consistent with norms or expectations, and is a potential consequence of disease. "Total" CD disability has two clear components: "acute" disability induced by disease activity, and permanent disability. Permanent disability is usually associated with active disease that does not respond to any treatment, or with sequelae of disease or of previous surgical treatment. For work disability, the impairment must be permanent or, at least, should have a low probablility of improvement. | CD | Awarding social benefits and medical research | 1 year | 4-level Likert scale | Total score (16) Clinical determinants (11) Social derterminants (5) | 64 - 16 NA NA |

| Short Crohn's Disease Work Diseability Questionnaire (sCDWDQ)40 | Spanish (ES) | Disability has been defined as chronic limitation(s) that interfere with the ability to engage in usual daily activities. Work-disability is defined as the inability to perform any substantial gainful work-related tasks because of a medically determinable physical or mental impairment. | CD | Clinical trials and clinical practice | 1 year | 4-level Likert scale | Total (9) | 36 - 9 |

| IBD Disability Index-14 self-report (IBDDI-14-s)42,43 | English (INT) | Problems associated with a disease involving body functions, body structures or activities and participation. I The decrement in functioning is the result of an interacion between underlying health conditions and contextual factors, namely environmental and personal factors. | IBD | Clinical trials and clinical practice | 1 week | Variable | Total score (14) | 100 - 0 |

| IBD Disability Index self-report (IBDDI-SR)44 | English (NZ/AUS) | Problems associated with a disease involving body functions, body structures or activities and participation.I The decrement in functioning is the result of an interacion between underlying health conditions and contextual factors, namely environmental and personal factors. | IBD | Clinical trials and clinical practice | 1 week | Variable | Total score (28) Overall health (1) Body functions (9) Body structures (2) Activities and participation (6) Environmental factors (14) | -80 - 22 -4 - 0 -31 - 2 -3 - 2 -24 - 0 -18 - 18 |

| IBD Disability Index Self-Report (IBDDI-SR-8)44 | English (NZ/AUS) | Problems associated with a disease involving body functions, body structures or activities and participation. I The decrement in functioning is the result of an interacion between underlying health conditions and contextual factors, namely environmental and personal factors. | IBD | Clinical trials and clinical practice | 1 week | Variable | Total score (8) | -26 - 6 |

| IBD Disk45 | English (INT) | Problems associated with a disease involving body functions, body structures or activities and participation. I The decrement in functioning is the result of an interacion between underlying health conditions and contextual factors, namely environmental and personal factors. | IBD | Clinical practice | 1 week | Numerical scale | Visual score (10) | 100 - 0 |

| Self-report disease activity | ||||||||

| Patient Harvey Bradshaw Index (pHBI)54 | Dutch (NL) | No clear description provided, probably: Disease flares can be intense and are frequently accompanied by increased pain, fatigue, and diarrhea (...) CD can challenge the well-being of patients and limit their daily functioning54. And: Over-all activity of Crohn's disease (...) incorporting factors considered as important indicators of disease activity by most knowledgable gastroenterologists34. | CD | Clinical trials | 1 week | Variable rating scales (range 0-4) or frequency | Total score (11) | >15 - 0 |

| Harvey Bradshaw mobile App (HBImApp)55 | Spanish (ES) | No clear description provided, probably: "CD is extremely unpredictable, characterized by periods of remission and activity.(…) Exacerbation is associated with symptoms, such as diarrhea, abdominal pain, and/or weight loss". | CD | Clinical practice | 1 day | Variable rating scales (range 0-4) or frequency or present/ absent | Total score (12) | >16 - 0 |

| Self-report Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index (s-SCCAI)48 | English (UK) | Probably like SCCAI. SCCAI has no clear definition provided, only: Complete assessment of disease activity of UC involves symptomatic evaluation, physical examination, (...) laboratory indices, and sigmoidoscopic assessment. (…) devise an (...) index of disease activity using a small number of clinical criteria (..) not require physical examination, sigmoidoscopic evaluation, or laboratory indices36. | UC | Clinical trials | Not defined | Variable rating scales (range 0-4) | Total score (6) | 19 - 0 |

| Patient Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index (p-SCCAI)46 | Dutch (NL) | "UC is a chronic, relapsing condition that is manifested as inflammation in the rectum and sometimes in the rest of the colon. UC is predominantly associated with symptoms such as abdominal pain, (bloody) diarrhea, weight loss, anemia, fatigue and fevers. Extracolonic features (..) can also occur." | UC | Clinical practice and clinical trials | 1 week | Variable rating scales or yes/no/ I don't know (range 0-3) | Total score (13) | 19 - 0 |

| German IBD activity index - CD (GIBDI-CD)56 | German (DE) | No clear description provided, only 'Disease activity'. | CD (excl. pouch or stoma) | Survey research | Variable | Variable rating scales (range 0-4) | Total score (8) | 21 - 0 |

| German IBD activity index - UC (GIBDI-UC)56 | German (DE) | No clear description provided, only 'Disease activity'. | UC or CD with pouch (excl. stoma) | Survey research | Variable | Variable rating scales (range 0-4) | Total score (7) | 21 - 0 |

| Manitoba IBD Index (MIBDI)57 | English (CA) | No clear description provided, only: patient-defined disease activity over longer periods of time." | UC and CD | Prospective research | 6 months | 6-Level Likert (a-f) | Single question | a - f |

| Mobile Health Index CD (mHI-CD)51 | English (USA) | No clear description provided, only "Disease activity". | CD | Home monitoring application | Not defined | Variable rating scales or yes/no | Total score (4) (weighted scoring fomula) | 14,2856 - 0 |

| Mobile Health Index UC (mHI-UC)51 | English (USA) | No clear description provided, only "Disease activity". | UC | Home monitoring application | Not defined | Variable rating scales | Total score (4) (weighted scoring formula) | 10,6773 - 0 |

| 6-point Score49 | English (USA) | Probably like Mayo Score. Mayo has no clear description provided, only: Patients daily recorded the frequency of their stools, any rectal bleeding, (...) a physician global-assessment score (the patient's daily record of abdominal discomfort and general sense of well-being and other observations, such as physical findings and the patient's performance status) (..) and the proctoscopic appearance37." | UC | Clinical trials | Not defined | 4-level Likert (0-3) | Total score(2) | 6 - 0 |

| Patient-reported ulcerative colitis severity index (PRUCSI)47 | English (USA) | Probably like Mayo Score. Mayo has no clear definition provided. Probably: "Patients daily recorded the frequency of their stools, any rectal bleeding, (...) a physician global-assessment score (the patient's daily record of abdominal discomfort and general sense of well-being and other observations, such as physical findings and the patient's performance status) (..) and the proctoscopic appearance37." | UC | Clinical trials | Undefined | Variable rating scales (range 0-4) | Total score (3) (weighted score formula) | 11,5155 - 0 |

| Self-Report Scale (SRS)50 | English (CA) | No clear description provided. Probably based on symptoms represented in original St. Mark's index38 in combination with laboratory indices and sigmoidoscopic findings. | UC | Clinical trials and clinical practice | 1 day | Variable rating scales (range 0-3) | Total score (7) | 13 - 0 |

| IBD Symptom Inventory - Long form (IBDSI-LF)58 | English (CA) | "Symptoms that could be used in both CD and UC (…) a wide range of symptoms which may vary in presentation among patients over time (…) such as fatigue, gas and blaoting, urgency of bowel movements, soiling, difficulties with weight, fever and sleeping (...) general health, abdominal pain, consistancy of bowel movements and IBD-related complications." | IBD | Clinical practice | 1 week | Variable rating, Likert of frequency scales (rescaled scoring range 0-4) | Total score (35)* Bowel symptoms (9) Abdominal discomfort (11) Fatigue (6) Bowel complications (3) Systemic complications (5) | 137 - 0 4 - 0 4 - 0 4 - 0 4,3 - 0 4 - 0 |

| IBD Symptom Inventory - Short form (IBDSI-SF)58 | English (CA) | "Symptoms that could be used in both CD and UC (…) a wide range of symptoms which may vary in presentation among patients over time (…) such as fatigue, gas and blaoting, urgency of bowel movements, soiling, difficulties with weight, fever and sleeping (...) general health, abdominal pain, consistancy of bowel movements and IBD-related complications." | IBD | Research or clinical practice | 1 week | Variable rating, Likert of frequency scales (rescaled scoring range 0-4) | Total score (24)* | 95 - 0 |

| Bowel symptoms (9) Abdominal and bodily discomfort (12) Fatigue (3) | 3,9 - 0 4 - 0 4 - 0 | |||||||

| Monitor IBD at Home questionnaire - CD (MIAH-CD)53 | Dutch (NL) | No clear description provided. Only: "(…) IBD activity should accurately reflect mucosal inflammation." | CD | Remote monitoring | 1 day | Rating scale (0 - >10) or yes/no or No/Yes, urgent/ Yes, very urgent | Total score (6) (weighted scoring formula) | 8,59 - 1,01 |

| Monitor IBD at Home questionnaire - UC (MIAH-UC)53 | Dutch (NL) | No clear description provided. Only: "(…) IBD activity should accurately reflect mucosal inflammation." | UC | Remote monitoring | 2 day | Rating scale (0 - >10) or yes/no or No/Yes, urgent/ Yes, very urgent | Total score (5) (weighted scoring formula) | 9,83 - 0 |

| Visual analog scale - UC (VAS-UC)52 | Japanese (JA) | "UC (…) causes diffuse mucosal injuries from the rectum toward the proximal colon (…) patients present symptoms such as visible blood in stools, diarrhea and abdominal pain." "symptoms (…) are expected to reflect or partly parallel the activity of the disease in the colorectum." | UC | Clinical practice | 1 day | Visual analog scale (0-10) | General condition (1) Bloody stools (1) Stool form (1) Abdominal pain (1) | 0 - 10 0 - 10 0 - 10 0 - 10 |

| IBD-Control (IBD-C)59 | English (UK) | The goal of therapy for inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) is to achieve and maintain disease control and thereby optimise quality of life (QoL). Core domains in disease control are: physical, social, emotional and treatment. | UC and CD | Clinical practice | 2 weeks | yes/not sure/no (0-2) | IBD-C-8 sumscore (8) | 0 - 16 |

| Visual analog scale (0-100) | IBD-C-VAS (1) | 0 - 100 | ||||||

| Yes/not sure/no or better/ no change/worse | IBD-C individual questions (5) | NA | ||||||

| *Some questions have subquestions; some are not added in any total score or sumscore. | ||||||||

| IBD Questionnaire (IBDQ-32)60-66 | English (CA) | Health status, specifically: "Disease-related dysfunction in IBD patients" including identified domains by Mitchell et al: bowel function, systemic function, emotional function, social impairment and functional impairment85. | IBD (excl. proctitis and ileostomy) | Clinical trials | 2 weeks | 7-level Likert (1-7) | Total score (32) 49,50,52,53 Bowel symptoms (10) Systemic symptoms (5) Emotional function (12) Social function (5) | 32 - 224 10 - 70 7 - 35 12 -84 5 - 35 |

| IBD Questionnaire 5-Likert (IBDQ-5L)71 | Dutch (NL) | The quality of life of patients with a chronic disease, like inflammatory bowel disease, includes the patient's symptoms and physical functioning as well as psychosocial variables. | IBD (incl. ileostomy) | Clinical trials | 2 weeks | 5-level Likert (1-5) | Total score (32) Bowel symptoms (10) Systemic symptoms (5) Emotional function (12) Social function (5) | 32 - 160 5 - 50 5 - 25 12 -60 5 - 25 |

| UK IBD Questionnaire (IBDQ- 30)69-70 | English (UK) | Health-related quality of life is a subjective assessment of the patients' overall physical, mental, and social well-being as it relates to their own experience of ill health. | IBD (incl. proctitis) | Clinical trials | 2 weeks | 4-level Likert (1-4) | Bowel function I (6) Bowel function II (4) Systemic function (4) Emotional function (9) Social function (7) | 6 - 24 4 - 16 4 - 16 9 - 36 7 - 31 |

| Norwegian IBD Questionnaire (IBDQ-N)68 | Norwegian (N) | No clear description provided, probably like IBDQ-32. | IBD (excl. ileostomy) | Clinical trials | 2 weeks | 7-level Likert (1-7) | Total score (32) Bowel function I (7) Bowel function II (5) Emotional function I (11) Emotional function II (4) Social function (4) Single question (1) | 32 - 224 7 - 49 5 - 35 11 - 77 4 - 28 4 - 28 1 - 7 |

| German IBD Questionnaire (IBDQ-D)73 | German (DE) | No clear description provided, probably like IBDQ-32. | UC - IPAA patients | Clinical trials | 2 weeks | 7-level Likert (1-7) | Total score (32) | 32 - 224 |

| Short IBD Questionnaire 10-items (sIBDQ-10)72 | Englisch (UK) | No clear description provided, probably like IBDQ-32. | UC (excl. ileostomy and IPAA) | Clinical practice | 2 weeks | 7-level Likert (1-7) | Total score (10) Bowel scale (2) Systemic scale (2) Emotional scale (4) Social scale (4) | 10 - 70 2 - 14 2 - 14 4 - 28 2 - 14 |

| IBD Questionnaire 36-items (IBDQ -36)74 | English (CA) | No clear description provided, probably like IBDQ-32. | "Well" IBD | Clinical practice | 2 weeks | 7-level Likert (1-7) | Total score (36) Bowel symptoms (8) Systemic symptoms (7) Emotional function (8) Social impairment (6) Functional impairment (7) | 1 - 7 1 - 7 1 - 7 1 - 7 1 - 7 1 - 7 |

| Short IBD Questionnaire 9-items (sIBDQ-9)67 | Spanish (ES) | Health-related quality of life has been defined as the functional effect of an illness and its consequent therapy upon a patient, as perceived by the patient. | IBD | Clinical practice | 2 weeks | 7-level Likert (1-7) | Total score (9) | 0 - 100 |

| Health-related Quality of life | ||||||||

| Crohn's and Ulcerative Colitis Questionnaire (CUCQ-32)78,79 | English (UK) | No clear description provided. Probably like IBDQ-32. | IBD | Clinical trials and clinical practice | 2 weeks | 4-level Likert (0-3) or ordinal format (0-14) | Total score (32) Bowel (14)66 Psychological (9) Social (5) General (4) | 272 - 0 NA NA NA NA |

| Acute severe UC | Clinical trials and clinical practice | 2 weeks | 4-level Likert (0-3) or ordinal format (0-14) | Bowel (5)67 Psychological (10) Social (6) General (11) | NA NA NA NA | |||

| Crohn's and Ulcerative Colitis Questionnaire 8-items (CUCQ-8)78 | English (UK) | No clear description provided. Probably like CUCQ-32. | IBD | Clinical trials and clinical practice | 2 weeks | 4-level Likert (0-3) or ordinal format (0-14) | Total score (8) | 90 - 0 |

| Edinburgh IBD Questionnaire (EIBDQ)76 | English (UK) | No clear description provided, only: "the functional impact of an illness, and its consequent therapy, upon the patient, as perceived by the patient." | IBD | Clinical practice | Variable | 4-level Likert or Yes/No | Disease scale (5) Bowel scale (6) Information (2) | Not specified Not specified Not specified |

| Padova Quality of Life Questionnaire (PQoLQ)75 | Italian (I) | No clear description provided, only: "quality of life (QOL) is a somewhat complex and elusive concept, which has been defined as the possibility of attaining satisfaction from the activities of daily life, and is therefore a highly subjective value judgement." | IBD (excl. total colectomy) | Clinical practice | 2 weeks | 4-level Likert (0-3) | Total score (29) Intestinal symptoms (8) Systemic symptoms (7) Emotional function (9) Social symptoms (5) | 87 - 0 24 - 0 21 - 0 27 - 0 15 - 0 |

| IBD Quality of Life Questionnaire (IBD-QOL)77 | Chinese (CN-ML) | Patients' subjective perception of IBD, the impacts on daily life and the physical, mental and and social aspects of well-being. | UC and CD (excl. ostomies) | Clinical trials | 2 weeks | 5-level Likert (1-5) | Total score (22) Social function (5) Emotional function (6) Symptoms and discomfort (5) Bowel symptoms and its influences (6) | 22 - 110 5 - 25 6 - 30 5 - 25 6 - 30 |

| Function-related Quality of Life Instrument (Func-QoL)82 | English (USA) | The effects of accidents, disease and treatments on an individual's ability to both perform and enjoy the many functions and activities including work, recreation, household management and family life. | UC | Clinical trials | Not defined | Visual analog scale (0-10) or frequency | Disease specific parameters (5) (Trips to the toilet, stool consistency, rectal bleeding, abdominal/rectal pain, urgency) General parameters (7) (Ability to sleep, sexual relationship, outdoor activities, social activities, indoor activities, work/occupation, hobbies/recreation) | 10 - 0 Change score per individual item 10 - 0 Change score per individual item |

| Short Health Scale (SHS)81 | Swedish (SE) | Health-related quality of life is a measure of patients' experience of how illness or treatment interferes with life. Domains within this health status are biological variables, symptom burden, functional status (psychological and mental capacity and social activities), disease-related worry and general well-being. | UC | Clinical trials and clinical practice | Not defined | Visual analog scale (0-100) | Symptom burden (1) Functional status (1) Disease-related worry (1) General well-being (1) | 100-0 100-0 100-0 100-0 |

| Crohn's Disease burden thermometer (CD Burden)86 | English (USA) | No clear description provided, probably: symptom burden is the difference between the current health and the anticipated current health without CD symptoms. Treatment burden is the difference between current health and the anticipated current health if all things related to their CD treatment could be stopped while maintaining current health. | CD | Clinical practice | 'Current' | Visual analog scale (0-100) | Symptom burden (1) Treatment burden (1) | 0 - 100 0 - 100 |

| Crohn's Life Impact Questionnaire (CLIQ)83 | English (UK) | Life derives its quality from the ability and capacity of an individual to meet certain human needs. Rather than focus on symptoms and activity limitations, the needs-based model looks at how these impairments affect need fulfilment. | CD | Clinical trials and clinical practice | Today | True/ Not true (1-0) | Total score (27) | 27 - 0 |

| Health Status Scale Crohn's Disease (HSS-CD)80 | English (USA) | No clear description provided, both: "the scales were standardized to (…) includes health care use, daily function, and psychological distress." and "Health status is a quantifiable, multidimentional concept that incorporates the person's perception of illness, functional status, and phychological concomitants in addition to disease activity." | CD | Clinical practice and clinical trials | Variable | Variable | Composit score CD (10) (weighted scoring formula) | 100 - 0 |

| Health Status Scale Ulcerative Colitis (HSS-UC)80 | English (USA) | No clear description provided, both: "the scales were standardized to (…) includes health care use, daily function, and psychological distress." and "Health status is a quantifiable, multidimentional concept that incorporates the person's perception of illness, functional status, and phychological concomitants in addition to disease activity." | UC | Clinical practice and clinical trials | Variable | Variable | Composit score UC (9) (weighted scoring formula) | 100 - 0 |

| Abbreviations: AUS: Australia; CA: Canada; CD: Crohn’s disease; CN-ML, Chinese mainland; DE: Germany. ES, Spain; I: Italy. IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; INT, internationally developed; IPAA, ileal pouch-anal anastomosis; JA:Japan; NL: Netherlands; N: Norway. NA, not available; NL: Netherlands. NZ: New Zealand. Pop: population; PROM, Patient-Reported Outcome Measure; SE: Sweden; UC: Ulcerative colitis; UK: United Kingdom; USA: United States of America. |

3.2. Item content

The number of items per PROM ranged from 1 to 58, with a mean number of 16. The mean number of items for disability, self-report disease activity, and HR-QoL were 21, 9, and 20, respectively. Across all 44 PROMs, 155 item themes were recognised and grouped per domain as 47 physical aspects, 31 emotional aspects, 16 social aspects, and 37 function-related aspects; 24 remaining item themes were placed under miscellaneous, as is shown in Supplementary Data 2, available at ECCO-JCC online. The clinician-reported/composite instruments, that formed the basis for its adjoining modified PROMs, are displayed in grey as a reference. Their items are not included in the total item frequency across all PROMs, displayed in the last column.

The most frequently used themes in the physical aspect section were abdominal pain [27 PROMS, 26.5 items], energy/tiredness/fatigue [23 PROMs, 29.5 items], and diarrhoea/liquid stool/loose stool [23 PROMs, 25 items]; in the emotional aspects: tearful/upset [14 PROMs, 11.1 items] and angry/irritable [11 PROMs, 16.7 items]; in social aspects: cancelling/delaying social engagements [13 PROMs, 13 items]; and in intimate relationships/sexual activity [14 PROMs, 14 items]. Inability to play sports/leisure activities/outdoors [12 PROMs, 14 items] and affected function at or ability to work/attend school [10 PROMs, nine items] were the most frequently used items of the function-related aspects, and the overall most frequently used item was general well-being or health [32 PROMs, 34 items], which was placed under miscellaneous themes.

A comparison of our item division with the grouping of items within the PROMs’ subscales could not be made because this was not reproducible for all included PROMs. With the frequencies of the items, it is important to realise that several of the instruments had a single source for item generation: in Hr-QoL, items in all IBDQ-32 versions60–74 are based on one qualitative study,85 and the CUCQ instruments78,79 took the IBDQ-3069,70 as the basis for their instrument. The PQoLQ75 has, albeit not explicitly, stated how their items were generated: 27 of its 29 items were in common with the IBDQ-32 and did use the same development strategy. This is often referred to as the Padova IBDQ. Sixteen PROMs featured 71 items which were unique to their instrument, of which the IBD-DS41 featured 23 and the CLIQ 11. 83

With our predefined broad definitions as a reference, all the Hr-QoL PROMs should have items on physical, emotional, and social aspects, which most did, but the Func-QoL82 missed items on emotional aspects, the SHS81 lacked items on social aspects, and the HSS-CD80 and HSS-UC80 only had items on physical aspects. All items from the CD Burden86 PROM were placed under miscellaneous, which can be explained by ‘CD burden’ being a separate construct from Hr-QoL. In all ‘disability’ PROMs the four domains were represented. Self-report disease activity PROMs mainly featured items on physical aspects, except for the p-SCCAI,46 IBDSI-LF,58 and IBDSI-SF58 which have items on function-related aspects, and the IBD-C59 with items in each group except social aspects. The latter measures the distinct construct ‘disease control’ instead of ‘disease activity’, possibly explaining these findings.

3.3. Evaluation of content validity

3.3.1. Risk of bias assessment

Characteristics of participants involved in development and/or content validity studies are tabulated in Supplementary Data 3, available at ECCO-JCC online. In general, patient characteristics are poorly reported, limiting the interpretation of the represented target groups. The results on the standards and criteria of the individual development and content validity studies are shown in Supplementary Data 4, available at ECCO-JCC online. For 10 of the 44 PROMs, the definition of the construct was described clearly and in more detail than the general concepts of Hr-QOL, disability, and disease activity. Seven studies referred to a underlying conceptual framework. For 14 instruments, 22 content validity studies involving patients and three studies involving professionals were identified. For six PROMs it was not clear how many subscales were present or which items made up the reported subscales.39–41,44,67,78 The reported content validity studies represent the instruments as a whole. Comprehensibility was the most studied [n = 17] aspect of content validity, including five on the IBDQ-32 [and modifications] and one on the IBDDI-14-s, aimed at testing an adaptation in a new language.

3.3.2. Content validity

In all, 25 PROMs were rated as sufficient for relevance, comprehensiveness, and comprehensibility, as is shown in Table 2. Of these PROMs, the ‘disability’ measure IBDDI-SR-844 had moderate quality of evidence for all aspects, based on content validity studies of doubtful quality; those for relevance and comprehensibility were extrapolated from the content validity studies on the IBDDI-SR.44 For ‘Hr-QoL’, the CLIQ83 and IBDQ-3260–66 were found to have the best quality of evidence, rated as moderate, based on the presence of content validity studies of doubtful quality for relevance and comprehensibility. For self-report disease activity, the IBD-C59 had, albeit with low quality evidence based on the development study of doubtful quality and no content validity studies, the highest evidence in its group. It is followed by the equally placed MIBDI,57 MIAH-CD,53 IBDSI-LF, and IBDSI-SF,58 and then by GIBDI-CD and GIBDI-UC56 with very low quality evidence due to inadequate development studies and no content validity studies. Of the remaining PROMs with sufficient ratings for all three aspects, only the IBDDI-SR,44 IBDDI-14-s,42,43 IBDQ-30,69,70 and IBDQ-3674 had moderate quality of evidence for one or two of the aspects, generated by content validity studies of doubtful quality; the rest had a low or very low quality.

Table 2.

Quality of the evidence for content validity of the PROMs.

| PROM | Aspects of content validity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relevance | Comprehensiveness | Comprehensibility | ||||||

| Reference number | Rating of results | Quality of evidence | Rating of results | Quality of evidence | Rating of results | Quality of evidence | ||

| DISABILITY | IBDDI-SR-8 | 44 | + | M | + | M | + | M |

| IBDDI-SR | 44 | + | M | + | VL | + | M | |

| IBDDI-14-s | 42,43 | + | M | + | VL | + | M | |

| CPWDQ | 39 | + | L | + | L | + | L | |

| IBD-DS | 41 | + | VL | + | VL | + | VL | |

| IBD-Disk | 45 | + | VL | + | VL | + | VL | |

| sCDWDQ | 40 | + | L | - | L | + | L | |

| HR-QOL | CLIQ | 83 | + | M | + | L | + | M |

| IBDQ-32 | 60–66 | + | M | + | L | + | M | |

| IBDQ-30 | 69,70 | + | L | + | L | + | M | |

| IBDQ-N | 68 | + | L | + | L | + | M | |

| IBDQ-36 | 74 | + | L | + | M | + | L | |

| IBDQ-5L | 71 | + | L | + | L | + | L | |

| sIBDQ-10 | 72 | + | L | + | L | + | L | |

| IBD-QOL | 77 | + | L | + | L | + | L | |

| CUCQ-32 | 78,79 | + | VL | + | VL | + | VL | |

| CUCQ-8 | 78 | + | VL | + | VL | + | VL | |

| PQoLQ | 75 | + | VL | + | VL | + | VL | |

| SHS | 81 | + | VL | + | VL | + | VL | |

| IBDQ-D | 73 | + | M | - | M | + | M | |

| sIBDQ-9 | 67 | + | L | - | L | + | L | |

| HSS-CD | 80 | ± | VL | - | VL | + | VL | |

| HSS-UC | 80 | ± | VL | - | VL | + | VL | |

| Func-QoL | 82 | ? | VL | - | VL | ? | VL | |

| EIBDQ | 78 | - | VL | - | VL | - | VL | |

| DISEASE ACTIVITY | IBD-C | 59 | + | L | + | L | + | L |

| MIBDI | 57 | + | VL | + | VL | + | VL | |

| MIAH-CD | 53 | + | VL | + | VL | + | VL | |

| IBDSI-LF | 58 | + | VL | + | VL | + | VL | |

| IBDSI-SF | 58 | + | VL | + | VL | + | VL | |

| GIBDI-CD | 56 | + | VL | + | VL | + | VL | |

| GIBDI-UC | 56 | + | VL | + | VL | + | VL | |

| HBImApp | 55 | + | VL | - | M | + | M | |

| p-HBI | 54 | + | VL | - | VL | + | M | |

| p-SCCAI | 46 | + | VL | - | VL | + | M | |

| s-SCCAI | 48 | + | VL | - | VL | + | M | |

| CD Burden | 86 | ± | VL | + | VL | + | VL | |

| mHI-CD | 51 | + | VL | - | VL | + | VL | |

| mHI-UC | 51 | + | VL | - | VL | + | VL | |

| MIAH-UC | 53 | + | VL | - | VL | + | VL | |

| SRS | 50 | + | VL | - | VL | + | VL | |

| 6-point score | 49 | ± | VL | - | VL | ± | VL | |

| PRUCSI | 47 | ± | VL | - | VL | ± | VL | |

| VAS-UC | 52 | ± | VL | + | VL | ? | VL | |

Rating of results: Sufficient (+); Insufficient (-); Inconsistent (±); Inderterminate (?). Quality of evidence: H: high; M: moderate; L: low; VL: very low.

The remaining 19 PROMs were rated dissimilar between relevance, comprehensiveness, and comprehensibility, or insufficient for all aspects. The IBD-D73 had sufficient comprehensibility with a moderate quality of evidence based on a study of doubtful quality in IBD patients. Relevance and comprehensiveness were studied in a different population, ileal pouch-anal anastomosis [IPAA] patients, in a content validity study of doubtful quality: comprehensiveness was rated insufficient and relevance sufficient, both with moderate quality of evidence. The IPAA patients missed items on extra-intestinal manifestations. Comprehensiveness was also rated insufficient in 18 other instruments; however, the reviewers’ rating was decisive in all of those cases, as no content validity studies or clear development studies on comprehensiveness were identified. Only the HBImApp55 had a doubtful quality content validity study on comprehensiveness, though the criteria for comprehensiveness were rated as indeterminate. The EIBDQ76 was the only instrument rated insufficient for all three aspects. The criteria for good content validity were rated indeterminate based on its development study of inadequate quality, and thus the insufficient scores were based on the reviewers’ rating of the PROM. The Func-QoL82 could not be rated for relevance and comprehensibility, nor the VAS-UC52 for comprehensibility, because we did not have access to the full PROM and no other evidence was available from development or content validity studies.

4. Discussion

This study shows that of 44 IBD-specific PROMs reported to measure a form of Hr-QoL, disability, or self-report disease activity, 25 were rated as having sufficient relevance, comprehensiveness, and comprehensibility, but the strongest evidence stems from content validity studies of doubtful quality. Five instruments have the strongest evidence for measuring what they should measure in their group. In Hr-QoL, the evidence for relevance and comprehensibility of the CLIQ83 and IBDQ-3260–66 is of moderate quality and of low quality for comprehensiveness. In self-report disease activity the IBD-C59 has sufficient relevance, comprehensiveness, and comprehensibility, with low quality of evidence. In disability PROMs, the IBDDI-SR44 and IBDDI-SR-844 have sufficient relevance, comprehensiveness, and comprehensibility, based on evidence of moderate quality, except for comprehensiveness of the IBDDI-SR with very low quality. The overall body of evidence is of low quality due to a general lack of content validity studies and failure to base development processes on construct definitions and patient involvement. Before recommendations for their use in everyday practice can be made, independent content validity studies are advised and other measurement properties must be taken into account.

Ten PROMs provided a clear definition of the construct, seven with a clear conceptual framework. The grouping of all PROM items by the reviewer showed a fair number of recurring items that might be important for measurement of the selected constructs. Although some of the instruments had the same source for item generation, the modified versions kept including those items in their PROM, showing that these are important items in our selected constructs. The multitude of singularly used items could be an indication of the heterogeneity in current construct definitions.

In the encroaching demand for valid PROMs in clinical practice and medical research, the initial focus should be on reaching consensus for the preferred construct definitions in IBD populations. Definitions and conceptual frameworks for constructs such as Hr-QoL and disability are available, but these need to be operationalised for IBD populations when used for the development of solid IBD PROMs. Work is under way to define COS for several specified groups in IBD,17,19 addressing these issues. Once these have been defined, all available instruments on the specified construct, including those identified in this work, should be re-evaluated from the scope of the COS to find the most suitable measures. If available measures are unsuitable, new measures should be developed. Qualitative studies involving our IBD target populations cannot be omitted in that process. We feel our current work could be used as a starting point for concept elicitation and item generation when performing such qualitative studies.

One of the strengths of this work is the use of the methodology for the systematic review of PROMs following the standards and criteria for content validity in the COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist. The knowledge on PROM development has increased rapidly over the past decennia. This methodology is one of its youngest aids. Some of the PROMs pre-date these developments, but many were developed after the publication of the FDA guidance6 or the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research [ISPOR] quidelines87 for qualitative studies in PROM development. Future researchers and developers of PROMs in the field of gastroenterology should be aware of the different guidelines that can be used when preparing a study on PROM development or psychometric testing.

Some limitations to the design and execution of this work must be acknowledged. Some degree of subjectivity was necessary in the rating of the standards of criteria. A lack of consensus on definition and operationalisation of the constructs only complicated the ratings. However, we tried to be as transparent and systematic as possible. Most conclusions on content validity were solely based on the reviewers’ opinion of the instrument from the perspective of these definitions, because additional evidence from studies was lacking. This may have been especially of influence for the comprehensiveness of self-report disease activity measures, for which clear definitions were not provided by the authors. Our definition stated that disease activity must affect both intestinal and systemic physical aspects, which was not met by 11/18 instruments because of lack of sufficient items on systemic physical aspects. These findings accentuate the need for clarity and consensus on the construct of disease activity from the perspective of the various IBD populations, with a subsequent re-evaluation of available instruments.

Item content grouping, data extraction, and the steps of the COSMIN methodology for content validity were only performed by a single reviewer, due to lack of resources. The results could be biased by the interpretation of data by a single reviewer. The inclusion criteria were narrowed and methods of data extraction were altered with the updated COSMIN methodology after initial title and abstract screening up to July 2017. Because a sensitive search strategy was used, we expect this will not have changed the results.

The information reported by the included articles was insufficient to correctly apply the COSMIN methodology in several areas. Ideally, subscales of a PROM are assessed as individual instruments in reference to clearly defined construct definitions. This was not possible, because individual subscales of included PROMs could not all be reproduced and all PROMs were assessed as a whole. None of the studies reported to have assessed the subscales on their PROM individually either, when assessing relevance, comprehensiveness, and comprehensibility.

Sparse information was available on the methodology and results of most included content validity studies. For example, the IBDQ-D73 reports a focus group session with 13 IBD patients to examine a translation from English to German. The authors report the following: ‘Their suggestions regarding the choices of words and comprehensibility were worded into a final version’. This was interpreted as a content validity study for comprehensibility and it was rated of doubtful quality, because it is unclear what exactly was done. The criteria for good measurement properties resulted in ‘indeterminate’ for comprehensibility, and the judgment of the reviewer resulted in ‘sufficient’. In case of ‘indeterminate’ criteria for the development or content validity studies or a lack of the latter, the reviewers’ rating was leading, ultimately deciding whether a PROMs was ‘sufficient’. Though with a doubtful content validity study present, there is moderate quality of evidence for its ‘sufficient’ comprehensibility. We feel this might have led to overestimation of the reliability of the ‘sufficient’ rating. Last, the lack of information regarding the tested populations in the development and content validity studies makes generalisability of the results difficult.

In conclusion, the majority of currently available IBD-specific PROMs measuring Hr-QoL, disability, and self-report disease activity lack both a clear definition of the construct of interest and patient involvement in the development and evaluation of its quality. Repeated studies on content validity are rarely performed. Overall, 25 out of 44 PROMs appear to have sufficient content validity, with the strongest evidence being of moderate quality, though most evidence is of low or very low quality. Future research should focus on defining the constructs of interest for IBD populations, and performing qualitative studies with IBD patients to design new instruments or confirm the content validity of the available instruments in light of the chosen constructs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. S. M. Bakker, medical information specialist at Noordwest Ziekenhuisgroep library and consultant J. C. F. Ket, medical information specialist at the Amsterdam UMC, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam library, for their aid in constructing and executing the systematic search in the various online databases.

Conference presentation: ECCO conference, Copenhagen 2019. Preliminary results up to July 2017 on content validity were presented by poster presentation.

Funding

This work was supported by an unrestricted educational grant from Dr Falk. The funder had no role in the study design, analysis or interpretation of data, preparation of the manuscript, or decision to publish.

Conflict of Interest

NKHB has served as a speaker for AbbVie and MSD. He has served as consultant and principal investigator for TEVA Pharma BV and Takeda. He has received an [unrestricted] research grant from Dr Falk and Takeda, all outside the submitted work. DPA has served as a speaker for Dr Falk and Janssen Cilag. He has served as a consultant for Takeda. He received a research grant from Dr Falk and Janssen Cilag, all outside the submitted work.

Author Contributions

EA, CN, NKHB, DPA, and LM all contributed to the design of the study. EA, BK, and FC collected data, and EA analysed the data. EA drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Irvine EJ. Quality of life of patients with ulcerative colitis: past, present, and future. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2008;14:554–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Romberg-Camps MJ, Bol Y, Dagnelie PC, et al. Fatigue and health-related quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease: results from a population-based study in the Netherlands: the IBD-South Limburg cohort. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2010;16:2137–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cosnes J. Can we modulate the clinical course of inflammatory bowel diseases by our current treatment strategies? Dig Dis 2009;27:516–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Preamble to the Constitution of WHO as Adopted by the International Health Conference. 1946. Geneva: WHO; 1948.

- 5. World Health Organization, Health Statistics and Information Systems. WHOQOL: Measuring Quality of Life. https://www.who.int/healthinfo/survey/whoqol-qualityoflife/en/Accessed April 8, 2018.

- 6.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration; Center for Drug Evaluation and Research [CDER]; Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research [CBER]; Center for Devices and Radiological Health [CDRH]. Guidance for Industry Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims 2009; https://www.fda.gov/media/77832/downloadAccessed May 4, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mouzas IA, Pallis AG. Assessing quality of life in medical trials on patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Ann Gastroenterol 2000;13:261–3. [Google Scholar]

- 8. European Medicines Agency. Reflection Paper on the Regulatory Guidance for the Use of Health Related Quality of Life [Hrql] Measures in the Evaluation of Medicinal Products. Doc. Ref. EMEA/CHMP/EWP/139391/2004. 2005 www.ema.europe.euAccessed May 4, 2017.

- 9. Khanna P, Agarwal N, Khanna D, et al. Development of an online library of patient-reported outcome measures in gastroenterology: the GI-PRO database. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:234–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dutch Organisation for Gastroenterologists and Hepatologists. Dutch IBD Treatment Guideline. 2014–2015. https://www.mdl.nl/sites/www.mdl.nl/files/richlijnen/Document_volledig_Handleiding_met_literatuur_def.pdf Accessed May 4, 2017.

- 11. Lichtenstein GR, Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ; Practice Parameters Committee of American College of Gastroenterology Management of Crohn’s disease in adults. Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104:465–83; quiz 464, 484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mowat C, Cole A, Windsor A, et al. ; IBD Section of the British Society of Gastroenterology Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut 2011;60:571–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. Crohn’s Disease: Management Clinical Guideline. London: NICE; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. Ulcerative Colitis: Management. Clinical Guideline.London: NICE; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gomollón F, Dignass A, Annese V, et al. ; ECCO Third European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease 2016 part 1: diagnosis and medical management. J Crohns Colitis 2017;11:3–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gionchetti P, Dignass A, Danese S, et al. ; ECCO Third European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease 2016 part 2: surgical management and special situations. J Crohns Colitis 2017;11:135–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.COMET. The COMET [Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials] Initiative. http://comet-initiative.org/Accessed August 29, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.COSMIN. COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments. www.COSMIN.nlAccessed December 3, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ma C, Panaccione R, Fedorak RN, et al. Development of a core outcome set for clinical trials in inflammatory bowel disease: study protocol for a systematic review of the literature and identification of a core outcome set using a Delphi survey. BMJ Open 2017;7:e016146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Alrubaiy L, Rikaby I, Dodds P, Hutchings HA, Williams JG. Systematic review of health-related quality of life measures for inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 2015;9:284–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. de Jong MJ, Huibregtse R, Masclee AAM, Jonkers DMAE, Pierik MJ. Patient-reported outcome measures for use in clinical trials and clinical practice in inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;16:648–63.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chen XL, Zhong LH, Wen Y, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease-specific health-related quality of life instruments: a systematic review of measurement properties. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2017;15:177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Prinsen CAC, Mokkink LB, Bouter LM, et al. COSMIN guideline for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual Life Res 2018;27:1147–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, et al. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: an international Delphi study. Qual Life Res 2010;19:539–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mokkink LB, de Vet HCW, Prinsen CAC, et al. COSMIN risk of bias checklist for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual Life Res 2018;27:1171–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Terwee CB, Prinsen CAC, Chiarotto A, et al. COSMIN methodology for evaluating the content validity of patient-reported outcome measures: a Delphi study. Qual Life Res 2018;27:1159–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wilson IB, Cleary PD. Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life. A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA 1995;273:59–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ian Doyal LG. A Theory of Human Need. London: Palgrave; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Peyrin-Biroulet L, Cieza A, Sandborn WJ, et al. Disability in inflammatory bowel diseases: developing ICF core Sets for patients with inflammatory bowel diseases based on the international classification of functioning, disability, and health. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2010;16:15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Peyrin-Biroulet L, Cieza A, Sandborn WJ, et al. ; International Programme to Develop New Indexes for Crohn’s Disease [IPNIC] group Development of the first disability index for inflammatory bowel disease based on the international classification of functioning, disability and health. Gut 2012;61:241–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gower-Rousseau C, Sarter H, Savoye G, et al. ; International Programme to Develop New Indexes for Crohn’s Disease [IPNIC] group Validation of the inflammatory bowel disease disability index in a population-based cohort. Gut 2017;66:588–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Leong RW, Huang T, Ko Y, et al. Prospective validation study of the international classification of functioning, disability and health score in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis 2014;8:1237–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Best WR, Becktel JM, Singleton JW, Kern F Jr. Development of a Crohn’s disease activity index. National Cooperative Crohn’s Disease Study. Gastroenterology 1976;70:439–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Harvey RF, Bradshaw JM. A simple index of Crohn’s-disease activity. Lancet 1980;1:514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Walmsley RS, Ayres RC, Pounder RE, Allan RN. A simple clinical colitis activity index. Gut 1998;43:29–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. A randomized study. N Engl J Med 1987;317:1625–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Powell-Tuck J, Bown RL, Lennard-Jones JE. A comparison of oral prednisolone given as single or multiple daily doses for active proctocolitis. Scand J Gastroenterol 1978;13:833–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Vergara M, Montserrat A, Casellas F, et al. Development and validation of the Crohn’s disease perceived work disability questionnaire. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011;17:2350–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vergara M, Sicilia B, Prieto L, et al. Development and validation of the short Crohn’s disease work disability questionnaire. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2016;22:955–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Allen PB, Kamm MA, Peyrin-Biroulet L, et al. Development and validation of a patient-reported disability measurement tool for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013;37:438–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shafer LA, Walker JR, Chhibba T, et al. Independent validation of a self-report version of the IBD disability index [IBDDI] in a population-based cohort of IBD patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2018;24:766–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lo B, Julsgaard M, Vester-Andersen MK, Vind I, Burisch J. Disease activity, steroid use and extraintestinal manifestation are associated with increased disability in patients with inflammatory bowel disease using the inflammatory bowel disease disability index: a cross-sectional multicentre cohort study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;30:1130–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Paulides E, Kim C, Frampton C, et al. Validation of the inflammatory bowel disease disability index for self-report and development of an item-reduced version. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;34:92–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ghosh S, Louis E, Beaugerie L, et al. Development of the IBD disk: a visual self-administered tool for assessing disability in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2017;23:333–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bennebroek Evertsz’ F, Nieuwkerk PT, Stokkers PC, et al. The patient simple clinical colitis activity index [P-SCCAI] can detect ulcerative colitis [UC] disease activity in remission: a comparison of the P-SCCAI with clinician-based SCCAI and biological markers. J Crohns Colitis 2013;7:890–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bewtra M, Brensinger CM, Tomov VT, et al. An optimized patient-reported ulcerative colitis disease activity measure derived from the Mayo score and the simple clinical colitis activity index. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014;20:1070–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jowett SL, Seal CJ, Phillips E, Gregory W, Barton JR, Welfare MR. Defining relapse of ulcerative colitis using a symptom-based activity index. Scand J Gastroenterol 2003;38:164–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lewis JD, Chuai S, Nessel L, Lichtenstein GR, Aberra FN, Ellenberg JH. Use of the noninvasive components of the Mayo score to assess clinical response in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2008;14:1660–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Maunder RG, Greenberg GR. Comparison of a disease activity index and patients’ self-reported symptom severity in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2004;10:632–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Van Deen WK, van der Meulen-de Jong AE, Parekh NK, et al. Development and validation of an inflammatory bowel diseases monitoring index for use with mobile health technologies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:1742–50.e1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tsuda S, Kunisaki R, Kato J, et al. Patient self-reported symptoms using visual analog scales are useful to estimate endoscopic activity in ulcerative colitis. Intest Res 2018;16:579–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. de Jong MJ, Roosen D, Degens JHRJ, et al. Development and validation of a patient-reported score to screen for mucosal inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohn’s Colitis 2019;13(5):555–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bennebroek Evertsz’ F, Hoeks CC, Nieuwkerk PT, et al. Development of the patient Harvey Bradshaw index and a comparison with a clinician-based Harvey Bradshaw index assessment of Crohn’s disease activity. J Clin Gastroenterol 2013;47:850–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Echarri A, Vera I, Ollero V, et al. The Harvey-Bradshaw Index adapted to a mobile application compared with in-clinic assessment: the MediCrohn Study. Telemed J E Health 2020;26:80–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Janke KH, Raible A, Bauer M, et al. Questions on life satisfaction [FLZM] in inflammatory bowel disease. Int J Colorectal Dis 2004;19:343–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Clara I, Lix LM, Walker JR, et al. The mManitoba IBD index: evidence for a new and simple indicator of IBD activity. Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104:1754–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sexton KA, Walker JR, Targownik LE, et al. The inflammatory bowel disease symptom inventory: a patient-report scale for research and clinical application. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2019;25:1277–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Bodger K, Ormerod C, Shackcloth D, Harrison M; IBD Control Collaborative Development and validation of a rapid, generic measure of disease control from the patient’s perspective: the IBD-control questionnaire. Gut 2014;63:1092–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Guyatt G, Mitchell A, Irvine EJ, et al. A new measure of health status for clinical trials in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 1989;96:804–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ciccocioppo R, Klersy C, Russo ML, et al. Validation of the Italian translation of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire. Dig Liver Dis 2011;43:535–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Han SW, McColl E, Steen N, Barton JR, Welfare MR. The inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire: a valid and reliable measure in ulcerative colitis patients in the North East of England. Scand J Gastroenterol 1998;33:961–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Irvine EJ, Feagan BG, Wong CJ. Does self-administration of a quality of life index for inflammatory bowel disease change the results? J Clin Epidemiol 1996;49:1177–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Masachs M, Casellas F, Malagelada JR. Spanish translation, adaptation, and validation of the 32-item questionnaire on quality of life for inflammatory bowel disease[IBDQ-32]. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2007;99:511–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ren WH, Lai M, Chen Y, Irvine EJ, Zhou YX. Validation of the mainland Chinese version of the inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire [IBDQ] for ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2007;13:903–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Russel MG, Pastoor CJ, Brandon S, et al. Validation of the Dutch translation of the inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire [IBDQ]: a health-related quality of life questionnaire in inflammatory bowel disease. Digestion 1997;58:282–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Alcalá MJ, Casellas F, Fontanet G, Prieto L, Malagelada JR. Shortened questionnaire on quality of life for inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2004;10:383–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Bernklev T, Moum B, Moum T; Inflammatory Bowel South-Eastern Norway [IBSEN] Group of Gastroenterologists Quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: translation, data quality, scaling assumptions, validity, reliability and sensitivity to change of the Norwegian version of IBDQ. Scand J Gastroenterol 2002;37:1164–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Cheung WY, Garratt AM, Russell IT, Williams JG. The UK IBDQ - a British version of the inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire. Development and validation. J Clin Epidemiol 2000;53:297–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Mnif L, Medhioub M, Boudabbous M, Chtourou L, Amouri A, Tahri N. Tunisian version validation of quality life’s questionnaire for chronic inflammatory disease of intestine. Tunis Med 2013;91:685–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. de Boer AG, Wijker W, Bartelsman JF, de Haes HC. Inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire: cross-cultural adaptation and further validation. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1995;7:1043–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Han SW, Gregory W, Nylander D, et al. The SIBDQ: further validation in ulcerative colitis patients. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:145–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Häuser W, Dietz N, Grandt D, et al. Validation of the inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire IBDQ-D, German version, for patients with ileal pouch anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis. Z Gastroenterol 2004;42:131–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Love JR, Irvine EJ, Fedorak RN. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol 1992;14:15–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Martin A, Leone L, Fries W, Naccarato R. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. Ital J Gastroenterol 1995;27:450–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Smith GD, Watson R, Palmer KR. Inflammatory bowel disease: developing a short disease specific scale to measure health related quality of life. Int J Nurs Stud 2002;39:583–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Ruan J, Chen Y, Zhou Y. Development and validation of a questionnaire to assess the quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in Mainland China. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2017;23:431–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Alrubaiy L, Cheung WY, Dodds P, et al. Development of a short questionnaire to assess the quality of life in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis 2015;9:66–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Hutchings HA, Alrubiay L, Watkins A, Cheung WY, Seagrove AC, Williams JG. Validation of the Crohn’s and Ulcerative Colitis questionnaire in patients with acute severe ulcerative colitis. United European Gastroenterol J 2017;5:571–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Drossman DA, Li Z, Leserman J, Patrick DL. Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease health status scales for research and clinical practice. J Clin Gastroenterol 1992;15:104–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Hjortswang H, Järnerot G, Curman B, et al. The short health scale: a valid measure of subjective health in ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol 2006;41:1196–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Zbrozek A, Hoop R, Robinson M, McPherson M. Test of an instrument to measure function-related quality of life in patients with ulcerative colitis. Pharmacoeconomics 1993;4:31–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Wilburn J, McKenna SP, Twiss J, Kemp K, Campbell S. Assessing quality of life in Crohn’s disease: development and validation of the Crohn’s Life Impact Questionnaire [CLIQ]. Qual Life Res 2015;24:2279–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Barnes EL, Kappelman MD, Long MD, Evon DM, Martin CF, Sandler RS. A novel patient-reported outcome-based evaluation [PROBE] of quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2019;114:640–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Mitchell A, Guyatt G, Singer J, et al. Quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol 1988;10:306–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Wilcox AR, Dragnev MC, Darcey CJ, Siegel CA. A new tool to measure the burden of Crohn’s disease and its treatment: do patient and physician perceptions match? Inflamm Bowel Dis 2010;16:645–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]