Abstract

Introduction:

By the time an intervention is ready for evaluation in a definitive RCT the context of the evidence base may have evolved. To avoid research waste, it is imperative that intervention design and evaluation is an adaptive process incorporating emerging evidence and novel concepts. The aim of this study is to describe changes that were made to an evidence based intervention at the protocol stage of the definitive RCT to incorporate emerging evidence.

Methods:

The original evidence based intervention, a GP delivered web guided medication review, was modified in a five step process:

Identification of core components of the original intervention.

Literature review.

Modification of the intervention.

Pilot study.

Final refinements.

A framework, developed in public health research, was utilised to describe the modification process.

Results:

The population under investigation changed from older people with a potentially inappropriate prescription (PIP) to older people with significant polypharmacy, a proxy marker for complex multimorbidity. An assessment of treatment priorities and brown bag medication review, with a focus on deprescribing were incorporated into the original intervention. The number of repeat medicines was added as a primary outcome measure as were additional secondary patient reported outcome measures to assess treatment burden and attitudes towards deprescribing.

Conclusions:

A framework was used to systematically describe how and why the original intervention was modified, allowing the new intervention to build upon an effective and robustly developed intervention but also to be relevant in the context of the current evidence base.

Keywords: Complex intervention, potentially inappropriate prescribing (PIP), polypharmacy, deprescribing, multimorbidity

Introduction

Multimorbidity interventions tend to be complex in nature. A complex intervention is one with many different interacting elements that often requires a number of different behaviours from those delivering and receiving the intervention, and is further complicated by a degree of flexibility in its implementation.1 The Medical Research Council (MRC) has developed a framework for the development and evaluation of such interventions. This framework describes an iterative process whereby emerging evidence, piloting and feasibility work, and process and outcome evaluations, all contribute to the intervention design.1 By the time the final intervention has been deployed, found to be effective and the core components identified, depending on context and emerging evidence, the intervention may require some modification. Intervention modification may be described as a ‘systematically planned and proactive process of modification to fit the intervention into a new context…’, specifically delineating it from ‘intervention drift’ or unplanned changes.2 It is recognised that the core components of any effective intervention should be identified before adapting it any way, and that these components should not be modified, however discretionary components can be modified and additional components added.2 Intervention modification has been more thoroughly described in the area of public health interventions where differing contexts or populations may require an intervention to be adapted so it is suited to the local environment.3 It is important that any modifications to a complex intervention, whether it be at the point of system wide implementation or at the stage of a definitive RCT, are described in a systematic way. This transparency is necessary to allow for potential replication of an effective evidence based intervention and this paper sets out to systematically describe how and why a complex intervention was modified.

Supporting prescribing in older adults with multimorbidity (SPPiRE) is a cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT) that was designed to evaluate the effectiveness of a complex intervention comprising a web guided medication review and professional training in reducing polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate prescribing in older adults on 15 or more regular prescribed medicines in Irish primary care.4 SPPiRE built on a previous trial, optimising prescribing for older people in primary care (OPTI-SCRIPT), which was an exploratory cluster RCT.5 OPTI-SCRIPT was a complex intervention comprising academic detailing and a GP delivered web-guided medication review. This paper describes how the OPTI-SCRIPT intervention was modified in the context of emerging evidence in its associated fields of polypharmacy and multimorbidity and an emerging consensus that there is a paucity of specific evidence based recommendations to support clinicians manage these patients.6,7 It is established that a common cause of research waste is poor question selection,8 thus the driving factor for intervention modification in this case was a modified research question that encompassed the rapidly evolving concepts and evidence that were emerging in the intervention’s related fields.

Methodological approach

The OPTI-SCRIPT intervention was developed in line with MRC guidance and involved three main stages; review of the evidence base, modelling work, which involved both quantitative and qualitative methods, and a pilot study. The development of OPTI-SCRIPT has been extensively described elsewhere.9

The SPPiRE intervention was adapted from OPTI-SCRIPT in a five step process, see Table 1 for a summary. The SPPiRE study was originally entitled, OPTI-SCRIPT 2 and was designed to be the definitive, larger scale, nationwide version of the OPTI-SCRIPT RCT. Given the emerging evidence base and how the research question had been answered by a similar RCT in the intervening time frame, the trial management committee decided, at the time of protocol development of OPTI-SCRIPT 2 to modify the trial design and intervention to incorporate this emerging evidence. Due to the emergence of multiple new concepts, and the vast subject area, scoping searches of the literature were performed to:

Table 1.

Methodological approach for the modification of the OPTI-SCRIPT intervention.

| Step | Approach | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Identify the core components of the OPTI-SCRIPT intervention. | OPTI-SCRIPT RCT, parallel mixed methods process evaluation and economic evaluation. |

| 2 | Review the emerging evidence in the fields of polypharmacy and multimorbidity. | Scoping searches of the literature to assess where OPTI-SCRIPT fits and where knowledge gaps remain. |

| 3 | Modify the intervention and its evaluation to incorporate the information from steps 1 and 2. | Use of an existing framework to describe additions/substitutions and modifications to the OPTI-SCRIPT intervention and outcome measures used to assess its effect. |

| 4 | Assess the feasibility and acceptability of the modified intervention. | Uncontrolled pilot study of the modified intervention. |

| 5 | Final refinements to the intervention. | Assessment and incorporation of both qualitative and quantitative results from the pilot study. Detailed description of the final components and hypothesised pathway of change. |

Further clarify key concepts and definitions identified in the literature (specifically deprescribing, treatment burden and patient priorities).

To identify knowledge gaps and where OPTI-SCRIPT fits in the literature.

To review current multimorbidity and polypharmacy guidelines.

During round table discussions subsequent to the OPTI-SCRIPT evaluations and scoping searches, modifications were made to the OPTI-SCRIPT 2 protocol by the trial’s multidisciplinary management committee (TMC), including GPs, pharmacists and researchers. Round table consensus was reached on modifications and in cases where there were differing views, an opinion was sought from a wider multidisciplinary Scientific Advisory Group who were not on the management committee. The study manager (CMcC) designed the additional components for the medication review based on the literature review. Various iterations of the review design were developed based on round table feedback from the TMC and on feedback from academic GPs in the department who tested the process using hypothetical clinical vignettes. The newly modified SPPiRE intervention was further assessed by an uncontrolled pilot study that involved six GPs and ten patients. Participating GPs were recruited through word of mouth and consisted of four academic GPs, one full time clinical GP and one GP registrar. Given changes to the target population, the process in which patients were identified was modified. A patient finder tool was developed and incorporated into GP practice electronic health record management systems, that searched for all patients aged 65 years and over who were also currently in receipt of 15 or more repeat prescribed medicines. Participating GPs, ran the finder tool to identify all potentially eligible patients and then screened their list of medicines to ensure the tool was correctly identifying those on 15 or more ‘repeat’ medicines. Each GP then selected either one or two patients to attend for a SPPiRE medication review. Quantitative data collected included the absolute number and proportion of practice over 65’s identified by GPs as potentially eligible when running this finder tool. Qualitative data was collected by the study manger (CMcC) in the form of semi-structured telephone or face-to-face interviews. Further refinements and modifications were made to the process of patient identification and to the medication review by the TMC based on the pilot study results.

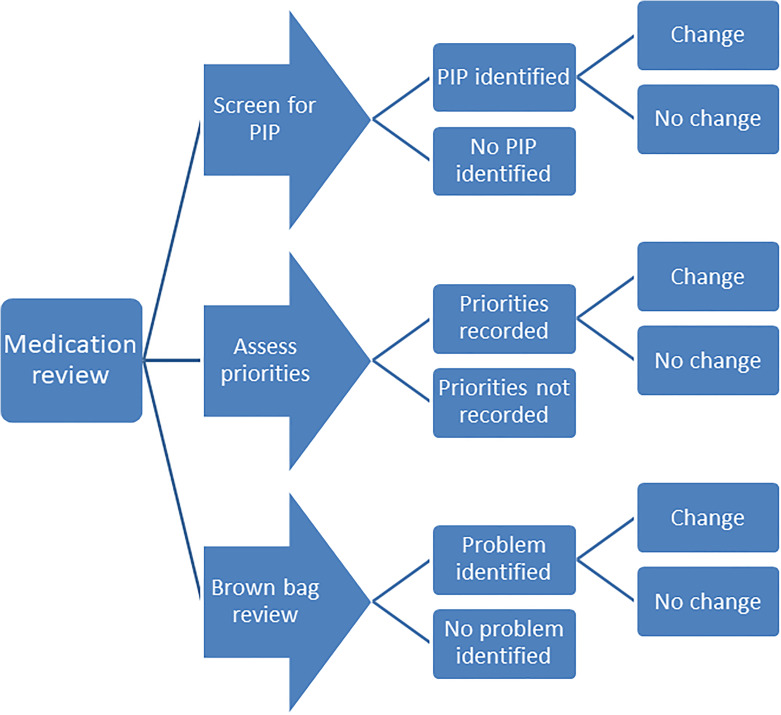

A framework that was developed to describe intervention modification will be used in this paper to describe step 3 (Table 1).10 This framework was not used during the process of modification but was selected to describe the steps involved in modification as it incorporated the main elements of the intervention and evaluation that were modified in this context of emerging evidence. Most of the work that informed the development of that framework was in the area of public health interventions where modifications are often necessary for an intervention to be implemented in a different context or population.3 The evolution of SPPiRE is similar in this regard as due to the emerging evidence described above, our research group reconsidered the overall research question and changed the population under investigation, focusing on a group more in need of intervention. This framework identifies three main components that can be modified, (see Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Adapted framework used to describe modifications to OPTI-SCRIPT intervention.10

-

The context in which the intervention is delivered:

Context modification is sub classified into changes to the format or setting an intervention is delivered in, or changes to the personnel or population delivering and receiving the intervention.

-

The content of the intervention:

This describes actual changes to the content and includes additions, substitutions, refinements, incorporation of an alternative approach or lengthening/shortening of an intervention.

-

The evaluation of the intervention:

Examples include selection of alternative or additional outcome measures so that the effect of new intervention components and approaches can be assessed.

Results

Identification and incorporation of the core components of the OPTI-SCRIPT intervention

The OPTI-SCRIPT intervention was a complex intervention that incorporated:

Academic detailing with an academic pharmacist who visited intervention practices and spent 30 minutes discussing PIP, medications reviews and the OPTI-SCRIPT web-guided alternative treatment algorithm process.

A web-guided medication review where the GP was presented with a list of PIPs for their patient and provided with alternative pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment algorithms and background information where relevant.

Patient information leaflets that provided the patient with information on the PIP and potential alternative pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment options.

The core component of the OPTI-SCRIPT intervention was the GP delivered web-guided medication review that involved identification of pre-selected PIPs and the provision of alternative treatment algorithms. The OPTI-SCRIPT criterion for PIP were derived from the Screening Tool of Older Persons’ Prescriptions11 and selected based on prevalence and a consensus method which has been described elsewhere.9 The trial’s parallel process evaluation demonstrated that the medication reviews were both feasible and acceptable to patients and GPs and suggested that face to face, as opposed to telephone or chart reviews were more likely to be effective, it also showed that the patient information leaflets were not used.12 As a result, the core structure of the SPPiRE intervention remained a face-to-face web guided medication review with the patient’s own GP.

Overview of emerging evidence

Subsequent to the completion of the OPTI-SCRIPT process and economic evaluations,12,13 our research group began formulating the protocol for the definitive trial. In the interim, the Data-driven Quality Improvement in Primary Care (DQIP) trial was published that assessed the effectiveness of a similar intervention that alerted GPs to PIP to facilitate a subsequent medication review, the results of which led our group to re-consider the original research question.14 Concurrently, some of our research group were involved in a Cochrane review looking at interventions to improve outcomes for patients with multimorbidity and to improve the appropriate use of polypharmacy,7,15 a seminal paper describing the burden of treatment theory was published16 and the concept of deprescribing was emerging.17 The first nationally developed guidance for multimorbidity was also published in the UK which specifically advised assessing treatment priorities and prioritising patients prescribed ≥15 medicines.18 This emerging evidence in the areas of multimorbidity, polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate prescribing led our group to consider not only medications that are potentially inappropriate as identified by an explicit tool but also potentially inappropriate due to an excessive treatment burden and inadequate evidence base for use in a specific patient. Given the large subject area, a general overview of this evidence is described below and summarised in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of emerging evidence that informed the evolution of OPTI-SCRIPT intervention into SPPiRE.

| Emerging evidence that informed the evolution of OPTI-SCRIPT intervention into SPPiRE | |

|---|---|

| Original research | |

| Paper | Conclusion |

| OPTI-SCRIPT trial5 | Web based medication review is effective in reducing PIP |

| OPTI-SCRIPT process evaluation12 | Web guided medication review acceptable to GPs and patients Focusing on high risk and ‘clinically relevant’ PIP more acceptable to GPs |

| DQIP trial14 | Alerts and informatics to facilitate GP medication review effective in reducing PIP |

| DQIP criteria19 | Identified priorities for safety and quality in prescribing Developed validated monitoring criteria |

| Systematic reviews | |

| Paper | Conclusion |

| Interventions for improving outcomes in multimorbidity7 | More RCTs in the area of multimorbidity needed Targeting risk factors or specific functional difficulties may lead to better outcomes |

| Interventions to improve the appropriate use of polypharmacy for older people15 | Interventions are effective in reducing PIP but impact on clinical and patient reported outcomes remains unclear |

| Interventions to Address Potentially Inappropriate Prescribing in Community-Dwelling Older Adults20 | Multi-faceted approach more likely to effective Future interventions should consider incorporating patient priorities |

| Clinical guidelines | |

| Guideline | Conclusions |

| SIGN Polypharmacy | Medication review should be offered to anyone in residential care, older patients and those on ≥10 medicines Consider unnecessary drug therapy Consider adherence and treatment burden |

| NICE Multimorbidity | Structured medication review should be offered to all people on ≥15 medicines Patient priorities should be assessed and care tailored accordingly Treatment burden should be addressed and minimised Consider treatments that can be stopped because of:

|

| NICE Medicines Optimisation | Structured medication review should be offered to anyone with polypharmacy (not defined), anyone with chronic conditions and older people Medication review should include an assessment of safety and appropriateness The need for monitoring should be reviewed |

| Review papers/new concepts | |

| Paper | Conclusion |

| Treatment burden16,21 | Important component to consider when providing care for patients with multimorbidity Polypharmacy is a common contributor to treatment burden |

| Deprescribing17,22,23 | Defined as ‘the process of withdrawal of an inappropriate medication, supervised by a health care professional with the goal of managing polypharmacy and improving outcomes’ Both feasible and safe Should be considered at every prescription request GPs concerned about precipitating ADWE |

OPTI-SCRIPT and DQIP trials

The OPTI-SCRIPT trial demonstrated that the intervention was effective in reducing PIP, however this was mediated mostly through the reduction in the prescription of proton pump inhibitors at full therapeutic dose for more than 8 weeks (adjusted odds ratio = 0.30; 95% CI, 0.14–0.68; p = .04).5 The trial’s parallel mixed methods process evaluation concluded that the intervention was both feasible and acceptable to GPs and patients, however GPs remarked that current practice workload made dedicated medication reviews for all older people unfeasible and that an intervention that focused on more high risk, or as they perceived clinically relevant PIP may be more amenable to incorporating into day to day practice.12 The economic evaluation concluded that despite being effective there was uncertainty about the cost effectiveness of the intervention,13 which may have reflected the fact that improved prescribing of proton pump inhibitors may not significantly affect self-rated health status. The DQIP study, a step wedged cluster RCT involving 34 general practices and 33,334 patients, demonstrated that an intervention comprising informatics that alerted GPs to PIP, did improve prescribing and was associated with reduced hospital admissions relating to heart failure and GI bleeding.14 Prior to the RCT, the DQIP group had developed a new set of prescribing criteria that included a list of indicators that were particularly associated with preventable drug related morbidity in the elderly and developed the first set of monitoring criteria, enabling the explicit identification of prescription that are high risk because of inadequate blood or other monitoring.19

Treatment burden and patient priorities

Treatment burden describes the work that is required of a patient to manage their medical conditions and is in addition to their disease burden.21 Examples include accessing and navigating complex and often fragmented health and social care systems, self-monitoring, life-style modification, adhering to complex treatment regimens and tolerating adverse effects from prescribed treatments.21 This ‘work’ often requires a degree of co-operation or assistance from the patient’s own social network. The burden of treatment theory, describes this relationship between patients, their social networks and the health care system which has assigned them this work,16 and was developed in order to better understand the resources a patient draws upon in order to adhere to their prescribed treatment regimen. For some patients, particularly those who are already time poor, socially isolated or have poor literacy skills this burden can become overwhelming.21 More recently the term ‘intrinsic capacity’ has been coined to describe the physical, mental and social capacities that a patient can draw upon to manage their health and that determines their overall functional ability. It has been proposed that it is necessary to consider a patient’s individual intrinsic capacity to ensure that health care is orientated towards appropriate outcomes and potentially harmful overtreatment is avoided.24

Polypharmacy may constitute treatment burden and although it is often appropriate and necessary in patients with multimorbidity, it is also frequently cited as an area of major concern by patients themselves.25,26 This has important consequences as patients with a significant medication burden may tactically manage their medicines by avoiding medicines they believe to be causing side effects or by altering dosing regimens to suit their lifestyle.27 Medicines management has been identified as an important component to improving outcomes for patients with multimorbidity.7,28 Many polypharmacy and multimorbidity guidelines have incorporated the concept of treatment burden, and advise taking a pragmatic and individualised approach when trying to rationalise medicines, specifically by addressing the patient’s priorities for treatment and trying to tailor care appropriately.18,29 This approach is supported in several review articles which recommend exploring patients’ priorities and actual drug utilisation as well as accepting and embracing uncertainty.22,30,31 Despite these recommendations, few relevant tools exist to support the elicitation of patient priorities in this context of multimorbidity and polypharmacy.32

Deprescribing

Rising levels of polypharmacy and treatment burden have led to calls for deprescribing type interventions, where inappropriate or ineffective medicines are discontinued.22 Despite being a vital component of safe prescribing, it is recognised that clinicians face many barriers to deprescribing, including a lack of awareness of appropriateness, a lack of acceptability of deprescribing, practical considerations such as time constraint and incorrect doctor assumptions about patient priorities.33 Qualitative work describing GPs’ approaches to managing patients with multimorbidity has also suggested that GPs are reticent to ‘rock the boat’ in these older complex patients.34 Similarly qualitative work with patients and their carers has suggested that both can be reluctant to stop a medicine that is not currently giving any perceived benefit for fear of missing out on possible future benefits.35 As a result, medicines that may be ineffective or inappropriate are often not discontinued.

Various interventions have been developed to aid clinicians in deprescribing inappropriate medicines and it has been demonstrated that these interventions are both feasible36 and safe37; however few interventions have been carried out by GPs in primary care and have targeted older multimorbid patients. In many of the trials identified in primary care, either a researcher or other member of the MDT performed the intervention and the results were then fed back to the GP.38–43 Other trials have looked at stopping a particular class of medication for example PPIs44 or medicines associated with falls in elderly45 as opposed to a more generic approach looking at overall medication appropriateness and effectiveness.

Many polypharmacy and multimorbidity guidelines have incorporated this concept of deprescribing and support taking a pragmatic and individualised approach when rationalising medications, where individual priorities as well as actual and intended drug utilisation are assessed.18,29

Modification of the OPTI-SCRIPT 2 protocol in the context of emerging evidence

Based on the emerging evidence described in step 2 above, the OPTI-SCRIPT TMC modified the original OPTI-SCRIPT 2 protocol. Approval for these modifications was sought from the trial funders and the ICGP Research Ethics Committee. Guidance on developing and evaluating multimorbidity interventions indicates a need to consider a clear research question and target population and a specific intervention focus46 and this was the initial approach during the modification process. The target population was changed from patients aged ≥65 years with an identified PIP to those aged ≥65 years and prescribed ≥15 repeat medicines, as significant polypharmacy has been identified as a proxy marker for multimorbidity. This was decided upon primarily because the original research question had been addressed and answered by the DQIP study and secondly because this population had been identified as in need of evidence based interventions.7 We decided to build on OPTI-SCRIPT and incorporate evolving guidance on managing patients with multimorbidity in primary care.18,28 The focus of the intervention therefore had to be broadened to address significant polypharmacy and incorporate a deprescribing element. The study manager, in consultation with the TMC and based on scoping searches of the literature developed several iterations of the new medication review process. A framework that was developed to describe intervention modification has been employed to describe the changes to the OPTI-SCRIPT intervention and its evaluation. This framework was not employed at the time of modification but rather retrospectively in analysing changes reported in this paper to ensure that modifications were described in a clear and systematic manner. This framework was developed using public health studies to code and describe modifications that were made at the point of large-scale implementation of evidence-based interventions; as a result, not all components of the framework were relevant in this context, for example, detail on who made the modifications and at what level they were made. However, the core components of this framework were adopted as they included the main elements of modification that were used in the development of SPPiRE and served as a useful tool to describe the actual and degree of change in each of the components, see Figure 1. These modifications and their rationale are outlined in Table 3.

Table 3.

Modifications to context, content and evaluation of the OPTI-SCRIPT intervention and trial.

| Framework component | Modification | Evidence/rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Context modification | ||

| Format/Setting/Personnel | No modification. GP delivered web guided face to face medication review. | OPTI-SCRIPT RCT demonstrated effectiveness of web guided medication review.5 |

| Population | Modified from patients aged ≥65 years with at least one identified PIP to patients aged ≥65 years and prescribed ≥15 medicines. | Evidence based interventions needed for patients with multimorbidity.7

Multimorbidity guidelines recommend targeting patients on ≥15 medicines.18 Treatment burden identified as important concept.16,21 |

| Content modification | ||

| Tailoring/tweaking/refining | Refinement and updating of the OPTI-SCRIPT PIP criteria. Review of clinical guidelines and treatment recommendations updated accordingly. Additional/updated clinical components added to the website (e.g. an anticholinergic risk scale). | Newly developed monitoring criteria.19

STOPP Version 211 Anticholinergic risk scale54 |

| Additions | GPs prompted to ask about and record patient treatment priorities. Brown bag medication review; patients asked to bring all their medicines in with them to the review. |

Multimorbidity and polypharmacy guidelines recommend18,29,55,56:

|

| Substitutions | Academic detailing delivered in person by research pharmacist substituted for online training videos developed by research GP. | Feasibility issues with large nationwide cluster RCT Time constraint identified as common theme by OPTI-SCRIPT GPs |

| Integration of another approach | Tailoring care and considering treatment priorities:

|

Concepts of treatment burden and deprescribing emerging as important considerations in caring for patients with multimorbidity. |

| Lengthening | Medication review process lengthened to 30 to 40 minutes. | SPPiRE pilot study. |

| Evaluation modification | ||

| Methodology | Similar to OPTI-SCRIPT the modified intervention will be evaluated by a cluster RCT with a parallel mixed methods process evaluation and economic evaluation. Slight differences to patient identification process. | Feasibility work around practice, recruitment and retention taken from OPIT-SCRIPT. Patient identification process piloted in SPPiRE pilot study. |

| Additional primary outcome measures | Number of repeat medicines, defined as any medicine with an ATC code prescribed on a repeat basis, including items prescribed regularly on an as needed basis. | Need to capture deprescribing approach of intervention. |

| Additional secondary outcome measures | Multimorbidity treatment burden questionnaire. Patients attitudes to deprescribing questionnaire. Medication changes, including medicines stopped, started and dose changes. |

Need to capture deprescribing and tailoring care approach of intervention. |

Context modification

Given that the core component of the OPTI-SCRIPT intervention was a GP delivered face to face, web guided medication review, the format, setting and personnel involved in the delivery of the intervention remained as such. Due to emerging evidence in the field of multimorbidity it was decided to target a population at higher risk of adverse medication related events.7 The first nationally published multimorbidity guidelines in the UK recommended targeting patients on ≥15 medicines as they are particularly at risk of adverse medication related events,18 and a national Irish dispensing database indicated that approximately 5% of those aged ≥65 years in Ireland are on ≥15 medicines.47 Agreeing upon the medication count of eligible participants involved several round table discussions and modelling exercises, whereby numbers of potentially eligible patients were estimated based on differing practice demographics and considering the prevalence of various degrees of polypharmacy in people aged ≥65 years. The trade-offs were between identifying patients most likely to benefit from a medicines management type intervention, identifying those with significant treatment burden and the practicalities of needing to identify a sufficient number of eligible participants. Another consideration was the potential difficulty of recruiting participants with a high degree of treatment burden. The target population was changed from patients aged ≥65 years with at least one PIP to patients aged ≥65 years who are prescribed ≥15 repeat medicines, a proxy marker for complex multimorbidity.48 Focusing on a group at higher risk of adverse medication related events, means they are potentially more likely to benefit from intervention and the intervention is more likely to be cost effective.49 A similar intervention to SPPiRE that targeted a lower risk group, (on >5 repeat medicines), did not have a significant effect as the population under investigation already enjoyed good quality of life.50

Content modification

The core component of the OPTI-SCRIPT intervention, a GP delivered web-guided medication review that involved identification of pre-selected PIP and the provision of alternative treatment algorithms, was maintained and various additions and modifications were made (see Figure 1 and Table 3).

The pharmacist delivered academic detailing was substituted for online professional training videos. The primary reason for this was practical; it was not feasible for an academic pharmacist to travel to the 51 different general practices that had been recruited nationwide for the SPPiRE trial. It has been established that when used with other interventions, academic detailing has a small but consistent beneficial effect on prescribing,51 however there is evidence that technological mediated approaches may be an alternative when face to face academic detailing is not feasible.52 In the case of SPPiRE, professional training was in the form of online training videos that provided a background on the core areas of polypharmacy, potentially inappropriate prescribing, multimorbidity and treatment burden as well as demonstrating how to perform a SPPiRE medication review using a clinical vignette. The OPTI-SCRIPT process evaluation described how the academic detailing sessions were well received by GPs but a common theme was time pressure, and the advantage of the online videos was that the GPs could access them at a time and place that suited and could revisit the material if desired.

The major modification to the medication review process was the addition of two new components to the web guided medication review; an assessment of patient priorities and a brown bag medication review, where patient medication concerns are addressed. The SPPiRE intervention thus incorporated both explicit measure of medication appropriateness, following on from OPTI-SCRIPT but also an assessment of patient concerns and priorities. At the time of the SPPiRE protocol development there was little published in the literature on how best to assess and record patient priorities and the effectiveness of doing so in improving prescribing or patient reported outcome measures; a systematic review identified one such tool which had been developed and validated for use in patients with multimorbidity.32,53 As the effectiveness, feasibility and potential for negative effects from use of these tools had not been assessed it was decided not to directly operationalise this process. In the SPPiRE intervention, GPs were prompted to ask their patient about their treatment priorities and record them. This idea of eliciting patient treatment priorities was covered in one of the online training videos. Similarly, intervention GPs were provided with information about ‘brown bag’ medication reviews in the training videos and supporting material, where they were advised to review each medicine with the patient to reconcile the items with the prescription list and to assess the effectiveness and side effects of each medicine. All patients were advised to bring all their medicines in with them to their appointment.

Some minor adjustments were made to the OPTI-SCRIPT PIP criteria based on the OPTI-SCRIPT trial results and the publication of monitoring criteria for high risk drugs,5,19 (see Online Appendix 1 and 2 for a list of the OPTI-SCRIPT and SPPiRE criteria). Clinical guidelines were reviewed and alternative treatment option recommendations updated as necessary. Some additional clinical components were added to the website, including links to online clinical guidelines, patient information leaflets and links to specific medication related information, for example an anticholinergic burden scoring system.54

Evaluation modification

Similarly to OPTI-SCRIPT, the effectiveness of the SPPiRE intervention will be assessed by a cluster RCT with a parallel mixed methods process evaluation and economic evaluation. Given the modifications to the population under investigation and to the content of the intervention, it was necessary to consider additional or alternative outcome measures. The OPTI-SCRIPT intervention targeted older patients with an identified PIP and the intervention specifically targeted PIP whereas the SPPiRE intervention targeted older patients with significant polypharmacy (≥15 medicines). SPPiRE also has a deprescribing element that prompts participating GPs to consider deprescribing medicines that are identified as PIP and medicines that either do not align to the patient’s treatment priorities or are causing concern or adverse effects for the patient. It was therefore necessary to incorporate a primary outcome that would capture deprescribing.11 Capturing and measuring the effectiveness of a deprescribing intervention is difficult, particularly for this cohort of patients with very significant polypharmacy, where one hospital admission or episode of care might result in multiple medication changes that are not necessarily reflected in the overall medication count. Consideration must also be given to the complex system in which the complex intervention is delivered; factors intrinsic to the system may affect the response to an intervention resulting in a response that is not linear or dose dependent.57,58 Assessing outcomes at multiple time points is a potential strategy to address that, but this also depends on resource issues. At the time of writing, despite most general practices in Ireland being fully computerised, it has not been possible to electronically extract participant data. A trial’s process evaluation can try and untangle and make senses of the many factors involved in whether an intervention has an effect or not and how context (or components of the complex system) may have exerted an influence. On a practical level, an objective and straightforward outcome measure was needed due to the difficulty in blinding GPs and study personnel as well as for calculating the sample size; and the number of repeat medicines was selected as an additional primary outcome measure (as well the proportion of patients with at least 1 PIP which was maintained from OPTI-SCRIPT). Prescriptions and medical record data required for the primary outcomes were submitted by GPs to the study manager but were assessed by a blinded independent pharmacist. Website data collected for the process evaluation will look at the immediate medication count pre and post intervention and the actual medication changes during the intervention. Additional secondary outcome measures will include medication changes (number of medicines stopped, started and dose changes), to further assess the response to the intervention.

OPTI-SCRIPT included patient reported secondary outcome measures and these were modified to determine the effect of the new individualised approach. Health related quality of life scores59 were maintained but patient medication beliefs and well-being scores60 were substituted for a patients attitude to deprescribing score61 and a multimorbidity treatment burden questionnaire.62 The latter was developed specifically to assess the effect of multimorbidity interventions on treatment burden.

Pilot of modified intervention

While we had previously conducted the exploratory OPTI-SCRIPT trial that had fed into SPPiRE, given the extent of the modifications made, we undertook a small uncontrolled pilot study of the SPPiRE intervention and process of patient identification in April 2017. Overall the intervention was well received by both GPs and patients, the majority of who reported feeling reassured that their medicines were being reviewed. Feedback from the pilot study resulted in small refinements to the process of patient identification, the training videos and the web site layout and has been described briefly elsewhere,4 further details are outlined in Table 4 below.

Table 4.

SPPiRE pilot results.

| Pilot component | Problem | Change |

|---|---|---|

| Patient finder tool | Over-identification of patients Ambiguity as to what items are counted as a medicine |

Tool re-coded so that only items with a unique WHO-ATC code are counted Tool re-coded so that only medicines marked as ‘current’ are counted Guidance document drawn up for participating GPs on how to count items on prescription list |

| Educational videos | Not fully watched by all GPs due to time constraints | Content condensed Focus on demonstrating review process |

| Web-guided medication review | Not fully completed by all GPs | Web site layout modified Instructions made more explicit Recommendation for more time to complete process (40 instead of 30 minutes) |

Final components of SPPiRE intervention

Following the completed pilot study final refinements were made to the intervention and a hypothesised pathway of change was drawn up for the trial’s parallel process evaluation63 see Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Hypothesised pathway of change for the SPPiRE intervention.

The finalised SPPiRE intervention has two broad steps, the first consists of prompts for the GP to record information and the second involves reviewing that information with the patient and agreeing and recording any subsequent medication changes. The sub components are described in detail below:

-

Part 1: Gather and record information:

1.1 Input SPPiRE ID number, participant age and number of repeat medicines.

-

1.2 Check for potentially inappropriate prescriptions (PIPs) by:

Identifying relevant drug groups

Recording if PIP is present

-

1.3 Address patient priorities by:

Recording patient reported treatment priorities

Considering if ongoing symptoms could be adverse drug reactions

-

1.4 Conduct a brown bag medication review by:

Assessing the effectiveness and side effects of each medicines

Assessing for actual drug utilisation

Recording any concerns identified by the GP or patient

-

Part 2: GP reviews the information gathered in step 1 with the patient, agrees upon and records any medication changes:

2.1 Review identified PIP, consider suggested alternatives and record any agreed changes

2.2 Review patient treatment priorities, consider if ongoing symptoms could be adverse drug reactions and record any agreed changes

2.3 Review information input during brown bag review and record any agreed changes.

2.4 GP is prompted to print a summary sheet for the patient, their carer, and/or their community pharmacist and to record the number of medicines at the end of the review following any agreed changes.

Discussion and conclusion

The MRC guidelines emphasise how complex interventions should be designed and evaluated in a systematic and through way, so that it is possible to tease out the potentially effective components and replicate the intervention for any potential broader implementation. However, given the time lag involved in intervention design and evaluation it is often the case that emerging bodies of evidence will render some of the original design obsolete, or even affect the relevance of the original research question. In order to ensure that clinical research is useful and not wasteful of resources and participants’ time it is vital that both the original research question, intervention design and intervention evaluation are continually re-evaluated in the context of emerging evidence. Furthermore, any subsequent modification to intervention design should be thoroughly described along with the rationale for the modifications. We utilised a framework that has been implemented in public health research to systematically describe which components of the original OPTI-SCRIPT intervention were modified, why this was done and subsequent modifications to the evaluation of the intervention so that the potential effect of any modification is assessed. This appears to be the first application of this framework outside of public health fields. A limitation of this work was that this framework was not used at the point of modification but retrospectively to describe the steps already taken. It is difficult to ascertain at this point, if the process and outcome of the modification would have been altered had the framework been employed at the time of modification, however it is likely that additional types of alteration may have been considered as a long list of possible alterations are detailed in the framework and that identifying the nature of the modification prior to its introduction may have generated more multi-disciplinary round table discussion prior to the process of modification. For example, ‘integrating another approach into the intervention’ was identified as a content modification as the idea of individually tailoring care and considering deprescribing were specific new approaches in the SPPiRE intervention. This approach was introduced over several iterations of intervention modification. This involved the study manager designing the original approach which may have been subject to individual biases and assumptions based on her professional background and then adjusting the modification based on MDT round table feedback. Although use of a framework driven top down approach to intervention modification may have the advantage of reducing bias in the process, the downside may be that alternative modifications not identified by the framework are not considered. On reflection now, use of the framework at the beginning of the process may have resulted in more structure and the need for less iterations in design, however we also feel that if such a framework were to be used from the beginning of the process it would be necessary to maintain a good degree of flexibility in how to it is utilised. We feel the overall approach has allowed us to build on an effective and robustly developed intervention so that the modified intervention was relevant to the current context and evidence base. A strength of this work is the demonstration of how intervention modification, at any stage in the development, evaluation or implementation process can and should be systematically and transparently described. This is particularly important in the areas of multimorbidity and polypharmacy where there is a rapidly evolving evidence base and given the priority of addressing these major areas for health systems, practitioners and patients.

Supplemental material

Supplemental Material, APPENDIX_1_SPPiRE_criteria for The evolution of an evidence based intervention designed to improve prescribing and reduce polypharmacy in older people with multimorbidity and significant polypharmacy in primary care (SPPiRE) by Caroline McCarthy, Frank Moriarty, Emma Wallace, Susan M Smith and Barbara Clyne for the SPPiRE Study Team in Journal of Comorbidity

Supplemental Material, APPENDIX_2_OPTI-SCRIPT_criteria.docx for The evolution of an evidence based intervention designed to improve prescribing and reduce polypharmacy in older people with multimorbidity and significant polypharmacy in primary care (SPPiRE) by Caroline McCarthy, Frank Moriarty, Emma Wallace, Susan M Smith and Barbara Clyne for the SPPiRE Study Team in Journal of Comorbidity

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: Caroline McCarthy and Susan M Smith are also affiliated with HRB Primary Care Clinical Trials Network Ireland, Discipline of General Practice, School of Medicine, NUI Galway, Ireland (https://primarycaretrials.ie).

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate: Full ethical approval for the study was granted by the Irish College of General Practitioners Research Ethics Committee (ICGP REC; SPPiRE study). Informed written consent was given by all patients and GPs participating in the study.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was funded by the Health Research Board (HRB) Primary Care Clinical Trials Network (http://primarycaretrials.ie/), grant reference number CTNI-014-011.

ORCID iD: Caroline McCarthy  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2986-5994

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2986-5994

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008; 337: a1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Movsisyan A, Arnold L, Evans R, et al. Adapting evidence-informed complex population health interventions for new contexts: a systematic review of guidance. Implement Sci 2019; 14(1): 105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Escoffery C, Lebow-Skelley E, Haardoerfer R, et al. A systematic review of adaptations of evidence-based public health interventions globally. Implement Sci 2018; 13(1): 125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McCarthy C, Clyne B, Corrigan D, et al. Supporting prescribing in older people with multimorbidity and significant polypharmacy in primary care (SPPiRE): a cluster randomised controlled trial protocol and pilot. Implement Sci 2017; 12(1): 99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clyne B, Smith SM, Hughes CM, et al. Effectiveness of a multifaceted intervention for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older patients in primary care: a cluster-randomized controlled trial (OPTI-SCRIPT Study). Ann Family Med 2015; 13(6): 545–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Muth C, Blom JW, Smith SM, et al. Evidence supporting the best clinical management of patients with multimorbidity and polypharmacy: a systematic guideline review and expert consensus. J Intern Med 2019; 285(3): 272–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Smith SM, Wallace E, O’Dowd T, et al. Interventions for improving outcomes in patients with multimorbidity in primary care and community settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; 3(3): CD006560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bleijenberg N, de Man-van Ginkel JM, Trappenburg JCA, et al. Increasing value and reducing waste by optimizing the development of complex interventions: enriching the development phase of the Medical Research Council (MRC) Framework. Int J Nurs Stud 2018; 79: 86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Clyne B, Bradley MC, Hughes CM, et al. Addressing potentially inappropriate prescribing in older patients: development and pilot study of an intervention in primary care (the OPTI-SCRIPT study). BMC Health Serv Res 2013; 13: 307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stirman SW, Miller CJ, Toder K, et al. Development of a framework and coding system for modifications and adaptations of evidence-based interventions. Implement Sci 2013; 8: 65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S, et al. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing 2015; 44(2): 213–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Clyne B, Cooper JA, Hughes CM, et al. A process evaluation of a cluster randomised trial to reduce potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people in primary care (OPTI-SCRIPT study). Trials 2016; 17(1): 386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gillespie P, Clyne B, Raymakers A, et al. Reducing potentially inappropriate prescribing for older people in primary care: cost-effectiveness of the OPTI-SCRIPT intervention. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2017; 33(4): 494–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dreischulte T, Donnan P, Grant A, et al. Safer prescribing – a trial of education, informatics, and financial incentives. N Engl J Med 2016; 374(11): 1053–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Patterson SM, Cadogan CA, Kerse N, et al. Interventions to improve the appropriate use of polypharmacy for older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; 10: CD008165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. May CR, Eton DT, Boehmer K, et al. Rethinking the patient: using Burden of Treatment Theory to understand the changing dynamics of illness. BMC Health Serv Res 2014; 14: 281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Reeve E, Gnjidic D, Long J, et al. A systematic review of the emerging definition of ‘deprescribing’ with network analysis: implications for future research and clinical practice. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2015: 80(6): 1254–1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Multimorbidity: assessment, prioritisation and management of care for people with commonly occurring multimorbidity. 2017, https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng56. [PubMed]

- 19. Dreischulte T, Grant AM, McCowan C, et al. Quality and safety of medication use in primary care: consensus validation of a new set of explicit medication assessment criteria and prioritisation of topics for improvement. BMC Clin Pharmacol 2012; 12: 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Clyne B, Fitzgerald C, Quinlan A, et al. Interventions to address potentially inappropriate prescribing in community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016; 64(6): 1210–1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mair FS, May CR. Thinking about the burden of treatment. BMJ 2014; 349: g6680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gnjidic D, Le Couteur DG, Kouladjian L, et al. Deprescribing trials: methods to reduce polypharmacy and the impact on prescribing and clinical outcomes. Clin Geriatr Med 2012; 28(2): 237–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Anderson K, Foster M, Freeman C, et al. Negotiating “unmeasurable harm and benefit”: perspectives of general practitioners and consultant pharmacists on deprescribing in the primary care setting. Qual Health Res 2017; 27(13): 1936–1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Integrated care for older people: guidelines on community-level interventions to manage declines in intrinsic capacity. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Löffler C, Kaduszkiewicz H, Stolzenbach C-O, et al. Coping with multimorbidity in old age – a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract 2012; 13(1): 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Noel PH, Frueh BC, Larme AC, et al. Collaborative care needs and preferences of primary care patients with multimorbidity. Health Expect 2005; 8(1): 54–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Coventry PA, Small N, Panagioti M, et al. Living with complexity; marshalling resources: a systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis of lived experience of mental and physical multimorbidity. BMC Fam Pract 2015; 16: 171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wallace E, Salisbury C, Guthrie B, et al. Managing patients with multimorbidity in primary care. BMJ 2015; 350: h176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Medicines optimisation: the safe and effective use of medicines to enable the best possible outcomes. 2015. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng5 [PubMed]

- 30. Todd A, Holmes HM. Recommendations to support deprescribing medications late in life. Int J Clin Pharm 2015; 37(5): 678–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Spinewine A, Schmader KE, Barber N, et al. Appropriate prescribing in elderly people: how well can it be measured and optimised? Lancet (London, England) 2007; 370(9582): 173–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mangin D, Stephen G, Bismah V, et al. Making patient values visible in healthcare: a systematic review of tools to assess patient treatment priorities and preferences in the context of multimorbidity. BMJ Open 2016; 6(6): e010903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Anderson K, Stowasser D, Freeman C, et al. Prescriber barriers and enablers to minimising potentially inappropriate medications in adults: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. BMJ Open 2014; 4(12): e006544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sinnott C, Hugh SM, Boyce MB, et al. What to give the patient who has everything? A qualitative study of prescribing for multimorbidity in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 2015; 65(632): e184–e191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Reeve E, To J, Hendrix I, et al. Patient barriers to and enablers of deprescribing: a systematic review. Drugs Aging 2013; 30(10): 793–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Page AT, Clifford RM, Potter K, et al. The feasibility and effect of deprescribing in older adults on mortality and health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2016; 82(3): 583–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Iyer S, Naganathan V, McLachlan AJ, et al. Medication withdrawal trials in people aged 65 years and older: a systematic review. Drugs Aging 2008; 25: 1021–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zermansky A G, Petty DR, Raynor D K, et al. Randomised controlled trial of clinical medication review by a pharmacist of elderly patients receiving repeat prescriptions in general practice. BMJ 2001; 323(7325): 1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Williams ME, Pulliam CC, Hunter R, et al. The short-term effect of interdisciplinary medication review on function and cost in ambulatory elderly people. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004; 52(1): 93–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Allard J, Hebert R, Rioux M, et al. Efficacy of a clinical medication review on the number of potentially inappropriate prescriptions prescribed for community-dwelling elderly people. CMAJ 2001; 164(9): 1291–1296. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lenander C, Elfsson B, Danielsson B, et al. Effects of a pharmacist-led structured medication review in primary care on drug-related problems and hospital admission rates: a randomized controlled trial. Scand J Prim Health Care 2014; 32(4): 180–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Campins L, Serra-Prat M, Gozalo I, et al. Randomized controlled trial of an intervention to improve drug appropriateness in community-dwelling polymedicated elderly people. Fam Pract 2016; 34(1): 36–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Olsson IN, Runnamo R, Engfeldt P. Drug treatment in the elderly: an intervention in primary care to enhance prescription quality and quality of life. Scand J Prim Health Care 2012; 30(1): 3–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Reeve E, Andrews JM, Wiese MD, et al. Feasibility of a patient-centered deprescribing process to reduce inappropriate use of proton pump inhibitors. Ann Pharmacother 2015; 49(1): 29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Campbell AJ, Robertson MC, Gardner MM, et al. Psychotropic medication withdrawal and a home-based exercise program to prevent falls: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999; 47(7): 850–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Smith SM, Bayliss EA, Mercer SW, et al. How to design and evaluate interventions to improve outcomes for patients with multimorbidity. J Comorb 2013; 3: 10–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Moriarty F, Hardy C, Bennett K, et al. Trends and interaction of polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate prescribing in primary care over 15 years in Ireland: a repeated cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2015; 5(9): e008656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Brilleman SL, Salisbury C. Comparing measures of multimorbidity to predict outcomes in primary care: a cross sectional study. Fam Pract 2013; 30(2): 172–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chiolero A, Paradis G, Paccaud F. The pseudo-high-risk prevention strategy. Int J Epidemiol 2015; 44(5): 1469–1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Muth C, Uhlmann L, Haefeli WE, et al. Effectiveness of a complex intervention on Prioritising Multimedication in Multimorbidity (PRIMUM) in primary care: results of a pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2018; 8(2): e017740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. O’Brien MA, Rogers S, Jamtvedt G, et al. Educational outreach visits: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007; 2007(4): Cd000409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ho K, Nguyen A, Jarvis-Selinger S, et al. Technology-enabled academic detailing: computer-mediated education between pharmacists and physicians for evidence-based prescribing. Int J Med Inform 2013; 82(9): 762–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. van Summeren JJ, Schuling J, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM, et al. Outcome prioritisation tool for medication review in older patients with multimorbidity: a pilot study in general practice. Br J Gen Pract 2017; 67(660): e501–e506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sumukadas D, McMurdo ME, Mangoni AA, et al. Temporal trends in anticholinergic medication prescription in older people: repeated cross-sectional analysis of population prescribing data. Age Ageing 2014; 43(4): 515–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Scottish Government Model of Care Polypharmacy Working Group. Polypharmacy guidance. 2nd ed Edinburgh: Scottish Government, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 56. American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on the Care of Older Adults with Multimorbidity. Guiding principles for the care of older adults with multimorbidity: an approach for clinicians. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012; 60(10): E1–E25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Plsek PE, Greenhalgh T. The challenge of complexity in health care. BMJ 2001; 323(7313): 625–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Shiell A, Hawe P, Gold L. Complex interventions or complex systems? Implications for health economic evaluation. BMJ 2008; 336(7656): 1281–1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. The EuroQol Group. EuroQol – a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 1990; 16(3): 199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Pouwer F, van der Ploeg HM, Ader HJ, et al. The 12-item Well-Being Questionnaire. An evaluation of its validity and reliability in Dutch people with diabetes. Diab Care 1999; 22(12): 2004–2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Reeve E, Low LF, Shakib S, et al. Development and validation of the revised Patients’ Attitudes Towards Deprescribing (rPATD) Questionnaire: versions for older adults and caregivers. Drugs Aging 2016; 33(12): 913–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Duncan P, Murphy M, Man M, et al. Development and validation of the Multimorbidity Treatment Burden Questionnaire (MTBQ). BMJ Open 2018; 8: e019413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kyne K, McCarthy C, Kiely B, et al. Study protocol for a process evaluation of a cluster randomised controlled trial to reduce potentially inappropriate prescribing and polypharmacy in patients with multimorbidity in Irish primary care (SPPiRE). HRB Open Res 2019; 2: 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, APPENDIX_1_SPPiRE_criteria for The evolution of an evidence based intervention designed to improve prescribing and reduce polypharmacy in older people with multimorbidity and significant polypharmacy in primary care (SPPiRE) by Caroline McCarthy, Frank Moriarty, Emma Wallace, Susan M Smith and Barbara Clyne for the SPPiRE Study Team in Journal of Comorbidity

Supplemental Material, APPENDIX_2_OPTI-SCRIPT_criteria.docx for The evolution of an evidence based intervention designed to improve prescribing and reduce polypharmacy in older people with multimorbidity and significant polypharmacy in primary care (SPPiRE) by Caroline McCarthy, Frank Moriarty, Emma Wallace, Susan M Smith and Barbara Clyne for the SPPiRE Study Team in Journal of Comorbidity