Abstract

Background:

The Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology (MSRSGC) provides a standardized reporting system for salivary gland fine-needle aspiration (SGFNA). We review the clinical utility of the MSRSGC at a tertiary care cancer center by assessing the rates of malignancy (ROM) among different categories.

Methods:

A retrospective search was performed to retrieve all SGFNA cases performed at our institution between 1/1/07 and 12/31/18. The initial primary diagnoses were recorded and cases were then assigned to appropriate MSRSGC categories. ROM was then calculated for all categories.

Results:

A total of 976 cases were identified, and 373 with follow-up. The ROM was 19.7% (192/976) for all-comers and 51.3% (192/374) among cases with follow-up. Using MSRSGC, SGFNA showed a sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) of 65.6%, 87.4%, 100%, and 72.6%, respectively. ROM for MSRSGC categories I, II, III, IVa, IVb, V, and VI were 20.7%, 30.0%, 45.8%, 3.3%, 50.7%, 100%, and 100%, respectively. Utilizing MSRSGC resulted in a nondiagnostic rate of 14.4%. The nondiagnostic rate was lower when the procedure was performed by pathologists vs nonpathologists (12.9% vs 15.8%) but was comparable when rapid on site evaluation (ROSE) was performed (12.9% vs 11.6%).

Conclusion:

In our patient population, MSRSGC resulted in a perfect PPV and moderate NPV. Utilizing MSRSGC results in a higher nondiagnostic rate due to the inclusion of cases with benign elements or cyst contents only in this category. Performing ROSE is more important in attaining an adequate sample than the specialty of the person performing SGFNA.

Keywords: fine-needle aspiration, Milan system for reporting salivary gland cytopathology, salivary gland

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Salivary gland tumors comprise a diverse group of benign and malignant neoplasms constituting at least 3% of all head and neck tumors.1 Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) has become relatively widespread practice in the initial workup of salivary gland lesions.2 Salivary gland FNA is able to distinguish benign vs malignant entities relatively reliably.3 As a result, it has become accepted internationally as a cost-effective tool that can reduce unnecessary surgical procedures in some patients with benign and nonneoplastic entities and determine the extent of surgery in patients with malignant ones.4,5 Still, in spite of its widespread use, as of a few years ago, there was no internationally accepted system for the reporting of salivary gland cytopathology. The Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology (MSRSGC) was established with the goal of creating a practical standardized reporting system for the reporting salivary gland FNA.6

The MSRSGC provides recommendations for the designation of several different FNA findings that lack definitive evidence of a neoplasm. For instance, the MSRSGC recommends a nondiagnostic designation for FNA cases demonstrating only necrosis, cyst contents (excluding those with a mucinous background), or benign salivary gland elements (when a defined mass is clinically present), with the added recommendation of including a descriptive note. There is good reason for cases demonstrating only cyst contents to be considered nondiagnostic as opposed to negative, as some case series confirm that roughly a quarter of these cases represent neoplasms, including a subset of a poorly sampled mucoepidermoid carcinomas.7–9 Although benign elements only may be seen by FNA cytology (FNAC) in the setting of sialadenosis, a rare noninflammatory bilateral enlargement of salivary glands, this entity does not produce a distinct mass.10 The presence of necrosis only by salivary gland FNAC would obviously be of concern given its association with high-grade malignancy; however, it may occur in benign neoplastic and nonneoplastic conditions and thus is not diagnostically useful in isolation.10 The MSRSGC recommends a diagnosis of category III: atypia of undetermined significance for those cases demonstrating only mucinous cyst contents because of the known risk of mucoepidermoid carcinoma in this group. Indeed, even when the epithelial elements of a low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma are sampled by FNAC, the mucous cells may mimic histiocytes within a mucinous background and thus lead to a false-negative diagnosis.8

The primary purpose of this study was to review the clinical utility of the MSRSGC at a tertiary care cancer center by retrospectively applying its diagnostic categories to all in-house salivary gland FNAs over a 10-year period at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC). This includes a comparison of rate of malignancy (ROM) for the categories as they were initially signed out against ROM following recommendations of the MSRSGC. As we had developed a pathology-run ultrasound-guided FNA (US-FNA) clinic during the study period, we also aimed to compare how diagnoses differed depending on whether the FNA was performed by pathologists or nonpathologists.

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Following approval by the Institutional Review Board at MSKCC, we performed a retrospective search of the electronic database in order to retrieve all salivary gland FNA cases performed at MSKCC between January 2007 and December 2018. Cases sampled in other institutions were not included in the analysis. A total of 976 cases were identified, 373 of which had surgical follow-up.

The initial primary diagnostic categories were recorded, and cases were then assigned to the categories based on MSRSGC recommendations. Cases which included descriptions of “cyst contents only,” “benign salivary gland elements only,” or “necrosis only” were reclassified as category I: nondiagnostic. Those cases which had been previously diagnosed as negative with descriptive diagnoses suggesting reactive conditions such as sialadenitis or reactive lymph nodes were reclassified as category II: nonneoplastic. Cases which had previously been diagnosed as atypical were retained as category III: atypia of undetermined significance, and further added to this category were all cases with descriptions of only mucinous elements or mucinous cyst contents. Cases previously diagnosed as neoplastic were divided into two subgroups: those with a specific benign diagnosis (eg, pleomorphic adenoma, Warthin tumor, or lipoma) were reclassified as category IVa: benign neoplasm, while those providing a more descriptive diagnosis with a differential diagnosis including multiple entities were reclassified as category IVb: salivary gland neoplasm of undermined malignant potential. Cases that had previously been diagnosed as suspicious or malignant were retained as category V: suspicious for malignancy and category VI: positive for malignancy, respectively.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. General findings

The distribution of cases by Milan category with associated ROM is demonstrated in Table 1. Of 374 cases that underwent surgical resection, roughly 10% (n = 38) were found to be nonneoplastic, 39% (n = 144) were benign neoplasms (Table 2), and 51% (n = 192) were malignant. Among cases with follow-up, when considering the suspicious (Milan V) and positive for malignancy (Milan VI) categories together as malignant, the overall sensitivity for malignancy was 65.6% (126/192), while the specificity was 87.4% (159/182). The positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) among cases with follow-up were 100% (126/126) and 72.6% (159/219), respectively. When performing this analysis among positive for malignancy cases only (Milan VI), the rates of sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV were 57.8% (111/192), 87.4% (159/182), 100% (111/111), and 67.9% (159/234), respectively.

TABLE 1.

Overall distribution of cases

| Cases with follow-up |

Overall |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milan category | Case distribution | Cases with follow-up | Neoplasia | Malignancy | Neoplasia | Malignancy | |

| I. Nondiagnostic | 14.5% (142/976) | 20.0% (29/142) | 55.2% (16/29) | 20.7% (6/29) | 14.2% (16/142) | 4.2% (6/142) | |

| II. Nonneoplastic | 20.0% (195/976) | 15.4% (30/195) | 53.3% (16/30) | 30.0% (9/30) | 8.2% (16/195) | 4.6% (9/195) | |

| III. Atypical | 5.4% (54/976) | 44.4% (24/54) | 62.5% (15/24) | 45.8% (11/24) | 31.4% (17/54) | 20.4% (11/54) | |

| IVa. Benign neoplasm | 24.8% (242/976) | 38.0% (92/242) | 98.9% (91/92) | 3.3% (3/92) | 37.6% (91/242) | 1.2% (3/242) | |

| IVb. SUMP | 13.8% (135/976) | 54.1% (73/135) | 98.6% (72/73) | 50.7% (37/73) | 53.3% (72/135) | 27.4% (37/135) | |

| V. Suspicious | 2.5% (24/976) | 62.5%(15/24) | 100% (15/15) | 100% (15/15) | 62.5% (15/24) | 62.5% (15/24) | |

| VI. Malignant | 18.9% (184/976) | 60.3% (111/184) | 100% (111/111) | 100% (111/111) | 60.3% (111/184) | 60.3% (111/184) | |

| Total | 100% (976/976) | 38.3% (374/976) | 89.8% (336/374) | 51.3% (192/374) | 34.4% (336/976) | 19.7% (192/976) | |

TABLE 2.

Benign salivary gland neoplasms

| Milan category | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IVa | IVb | V | VI | |

| Pleomorphic adenoma (n = 99) | 7.1% (7/99) | 2% (2/99) | 0 | 73.7% (73/99) | 17.2% (17/99) | 0 | 0 |

| Warthin tumor (n = 26) | 3.8% (1/26) | 19.2% (5/26) | 7.7% (2/26) | 53.8% (14/26) | 15.4% (4/26) | 0 | 0 |

| Oncocytoma (n = 13) | 7.7% (1/13) | 0 | 7.7% (1/13) | 7.7% (1/13) | 76.9% (10/13) | 0 | 0 |

| Intercalated duct adenoma (n = 2) | 0 | 50% (1/2) | 0 | 0 | 50% (1/2) | 0 | 0 |

| Basal cell adenoma (n = 2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100% (2/2) | 0 | 0 |

| Intercalated duct adenoma (n = 2) | 0 | 50% (1/2) | 0 | 0 | 50% (1/2) | 0 | 0 |

| Cystadenoma (n = 1) | 0 | 0 | 100% (1/1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total (n = 144) | 6.3% (9/144) | 6.3% (9/144) | 2.8% (4/144) | 61.1% (88/144) | 24.3% (35/144) | 0 | 0 |

Of the malignant cases, there were 83 primary salivary gland carcinomas (Table 3), 65 metastases, 40 lymphomas, 2 plasma cell myelomas, and 2 sarcomas (1 angiosarcoma and 1 Ewing sarcoma). The vast majority of metastatic tumors were of cutaneous origin, with the most common diagnoses being squamous cell carcinoma (49.2%, 32/65) and melanoma (29.2%, 19/65) followed by Merkel cell carcinoma (9.2%, 6/65).

TABLE 3.

Primary salivary gland malignancies

| Milan category | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IVa | IVb | V | VI | |

| Mucoepidermoid carcinoma (n = 24) | 4.2% (1/24) | 4.2% (1/24) | 16.6% (4/24) | 0 | 41.7% (10/24) | 8.3% (2/24) | 25.0% (6/24) |

| Acinic cell carcinoma (n = 9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33.3% (3/9) | 0 | 66.7% (6/9) |

| Adenoid cystic carcinoma (n = 8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50.0% (4/8) | 0 | 50.0% (4/8) |

| Myoepithelial carcinoma, de novo (n = 8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 62.5% (5/8) | 0 | 37.5% (3/8) |

| Myoepithelial carcinoma, ex PA (n = 2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50.0% (1/2) | 50.0% (1/2) | 0 | 0 |

| Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma | 0 | 0 | 16.7% (1/6) | 0 | 66.7% (4/6) | 0 | 16.7% (1/6) |

| Salivary duct carcinoma, de novo (n = 5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100% (5/5) |

| Salivary duct carcnoma, ex PA (n = 6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33.3% (2/6) | 0 | 66.7% (4/6) |

| Basal cell adenocarcinoma (n = 3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100% (3/3) | 0 | 0 |

| Carcinoma ex PA (n = 3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100% (3/3) | 0 |

| Adenocarcinoma (NOS) (n = 3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33.3% (1/3) | 0 | 0 | 66.7% (2/3) |

| Secretory carcinoma (n = 2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50.0% (1/2) | 0 | 50.0% (1/2) | |

| Oncocytic carcinoma (n = 1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50.0% (1/2) | 0 | 50.0% (1/2) | |

| Polymorphous adenocarcinoma (n = 1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100% (1/1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Clear cell carcinoma (n = 1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100% (1/1) | 0 | 0 |

| Total (n = 83) | 1.2% (1/83) | 1.2% (1/83) | 6.0% (5/83) | 3.6% (3/83) | 42.2% (35/83) | 6.0% (5/83) | 40.1% (33/83) |

Of the 976 salivary gland FNA cases that occurred during the study period, 56.4% of cases were collected by nonpathologists (Table 4), while 43.6% were collected by pathologists (Table 5). Roughly two-thirds of nonpathologist-performed salivary gland FNAs (78.4%, 431/550) still had adequacy performed by either a cytotechnologist or pathology attending.

TABLE 4.

FNAs performed by nonpathologists

| Milan category |

Total | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IVa | IVb | V | VI | ||||

| No adequacy (n = 119) | Malignant | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 15 | 25 | |

| Benign | 7 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 16 | ||

| No follow-up | 29 | 13 | 4 | 15 | 10 | 0 | 7 | 78 | ||

| Total | 31.1% (37/119) | 14.3% (17/119) | 5.0% (6/119) | 17.6% (21/119) | 11.8% (14/119) | 1.9% (2/119) | 18.5% (22/119) | 119 | ||

| Adequacy performed (n = 431) | Malignant | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 13 | 7 | 56 | 82 | |

| Benign | 3 | 3 | 5 | 33 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 63 | ||

| No follow-up | 46 | 76 | 18 | 83 | 37 | 6 | 20 | 286 | ||

| Total | 11.6% (50/431) | 18.6% (80/431) | 6.3% (27/431) | 26.9% (116/431) | 16.0% (69/431) | 3.0% (13/431) | 17.6% (76/431) | 431 | ||

| Grand Total | 15.8% (87/550) | 17.6% (97/550) | 6.0% (33/55) | 25.1% (137/550) | 15.1% (83/550) | 2.7% (15/550) | 17.8% (98/550) | 550 | ||

TABLE 5.

FNAs performed by pathologists

| Milan category | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IVa | IVb | V | VI | ||

| Malignant | 4 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 23 | 6 | 62 | 107 |

| Benign | 13 | 16 | 8 | 52 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 103 |

| No follow-up | 38 | 76 | 8 | 52 | 15 | 3 | 24 | 216 |

| Total | 12.9% (55/426) | 23.0% (98/426) | 4.9% (21/426) | 24.6% (105/426) | 12.2% (52/426) | 2.1% (9/426) | 20.2% (86/426) | 426 |

3.2 |. Category I: nondiagnostic

3.2.1 |. Nondiagnostic category before implantation of MSRSGC

Of all FNAs performed over the 10-year period, nondiagnostic results were initially reported (not according to MSRSGC guidelines) in 6.9% (67/976). As might be expected, only a minority of nondiagnostic salivary gland FNA cases had surgical follow-ups (23.9%, 16/67). Of these, 13 were associated with benign lesions (5 pleomorphic adenomas, 4 ectatic salivary ducts, 1 epidermal inclusions cyst, 1 reactive lymph node), and 3 were associated with malignancy (2 metastatic squamous cell carcinomas, 1 lymphoma). The overall rate of malignancy for FNA cases with a nondiagnostic FNA was thus relatively low (4.5%, 3/67) compared with the rate for cases with surgical follow-up (18.8%, 3/16).

3.2.2 |. Cyst contents and benign elements only

There were 38 cases over the study period that were described as having nonmucinous cyst contents only, constituting 3.8% of salivary gland FNAs overall. Of these, the majority (95%, 36/38) had initially been diagnosed as negative, with 2 cases diagnosed as nondiagnostic. Of the 6 cases with surgical follow-up, 5 were benign (2 ectatic salivary ducts, 1 case of chronic sialadenitis, 1 lymphoepithelial cyst, and 1 Warthin tumor) and 1 demonstrated a mucoepidermoid carcinoma. In total, then, the overall ROM associated with cyst contents only on salivary gland FNA was 2.6% (1/38), while among cases with follow-up the rate was 16.7% (1/6).

There were 47 cases over the study period which featured benign salivary gland elements only, accounting for 4.8% of salivary gland FNAs overall. Similar to those with cyst contents, the majority of these (80.9%, 38/47) were signed out as negative, with the remainder signed out as nondiagnostic. Of 12 cases with surgical follow-up, 9 were benign lesions (5 pleomorphic adenomas, 1 salivary duct ectasia, 1 case of chronic sialadenitis, 1 intercalated duct adenoma, 1 oncocytoma) and 3 represented metastatic malignancy (melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and papillary thyroid carcinoma). A salivary gland FNA consisting of benign contents only was thus associated with a 6.4% (3/47) overall ROM and 25% (3/12) ROM among those with follow-up.

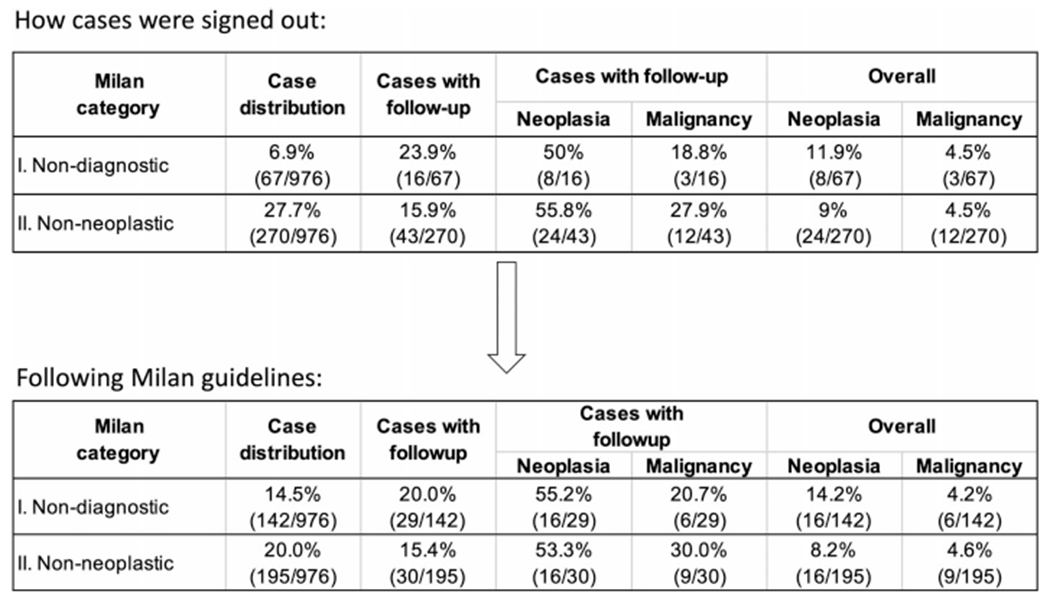

If all cases described as consisting only of nonmucinous cyst contents, benign contents, or necrosis had been diagnosed as nondiagnostic as recommended by the MSRSGC, the nondiagnostic rate would have been 14.4% (142/976) as opposed to the observed 6.9%. In terms of the risk for malignancy, this change in designation would have had minimal impact (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Difference in rates between how cases were classified and how they would have been classified following Milan recommendations. In the bottom table, cases with benign contents only, cyst contents only, or necrosis only are all classified as category I: nondiagnostic

3.2.3 |. Nondiagnostic category by MSRSGC

Among patients with initially nondiagnostic FNAC cases by MSRSGC criteria, 32 underwent at least one more repeat FNA. For 9 of these patients, the repeat FNAC was similarly non-diagnostic. Following this second nondiagnostic FNAC, 2 of these patients underwent surgical resection, with 1 demonstrating a 0.7-cm pleomorphic adenoma and 1 demonstrating a hemangioma.

There were 23 patients who initially had nondiagnostic FNAC and then had a diagnostic specimen on repeat FNA. 10 of these were categorized as category II: nonneoplastic, 5 were categorized as category III: atypia of undetermined significance (1 of these had surgical follow-up revealing chronic sialadenitis), 1 was categorized as IVa: benign neoplasm (Warthin tumor), 4 were categorized as category IVb: SUMP (the 2 cases with surgical follow-up showed benign neoplasms), and 3 were categorized as category VI: positive for malignancy (2 squamous cell carcinomas and 1 lymphoma).

3.2.4 |. Category II: nonneoplastic

Over the study period, there were 270 cases (27.7%) diagnosed as negative. As noted, however, a number of these cases consisted of benign contents or cyst contents only, eliminating these leaves 195 cases (20.0%). Of these, 130 provided a specific diagnosis, with the most common being reactive lymph node (66.9%, 87/130), chronic sialadenitis (19.2%, 25/130), and acute sialadenitis (6.9%, 9/130). Only a minority of nonneoplastic cases (20.0%) had surgical follow-up, with 9 malignancies (6 lymphomas, 1 mucoepidermoid CA, and 2 metastatic carcinomas from skin). In addition, there were 9 misdiagnosed benign neoplasms, including 5 Warthin tumors.

3.2.5 |. Category III: atypia of undetermined significance

This category of the MSRSGC was established to reduce the number of both false-positive and false-negative diagnoses. It should be used in situations where the FNAC findings are qualitatively or quantitatively insufficient to distinguish between nonneoplastic and neoplastic processes.

A primary diagnosis of atypical was utilized in only 5.5% of cases (54/976). The most common provided indications for this designation were the presence of an atypical epithelial (50%, 27/54) or lymphoid (27.8%, 15/54) population.

There were 24 atypical cases with surgical follow up (44%). Of these, 15 were neoplastic, including 4 benign (2 Warthin tumors, 1 oncocytoma, and 1 cystadenoma) and 11 malignant (5 lymphomas, 4 mucoepidermoid carcinomas, 1 metastatic squamous cell carcinoma, and 1 epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma) neoplasms. An atypical diagnosis was thus associated with a 20.4% risk of malignancy overall and 45.8% among cases with follow-up.

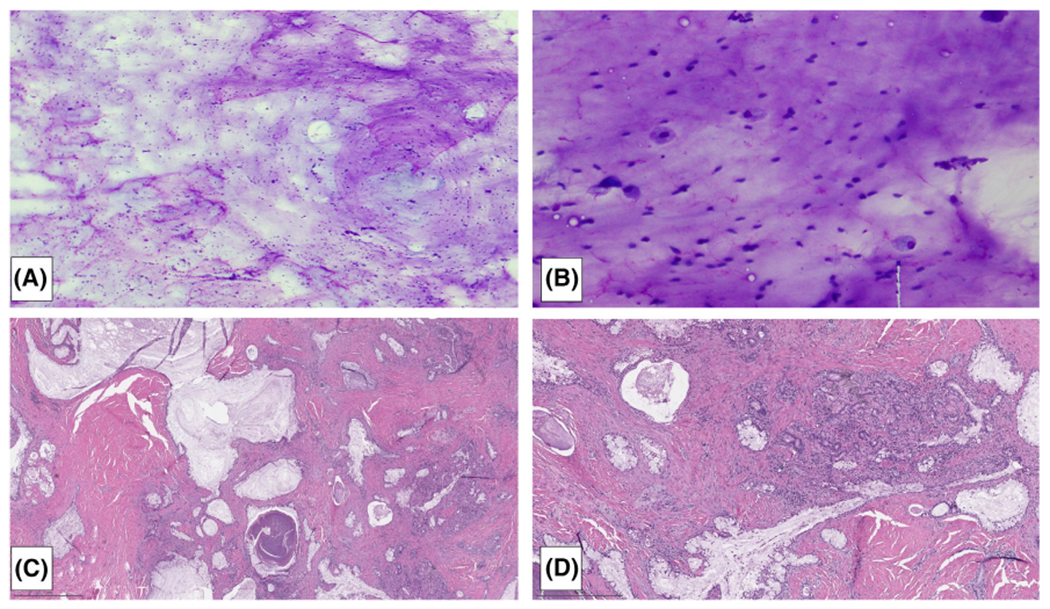

3.3 |. Mucinous contents only

According to the MSRSGC, a diagnosis of atypia of undetermined significance should be assigned to cases demonstrating mucinous contents only. There were 11 cases which demonstrated mucinous contents only, 5 of which had surgical follow-up. This revealed 3 mucoepidermoid carcinomas (Figure 2) and 2 cases of chronic sclerosing sialadenitis. The overall rate of malignancy among cases with mucinous contents only was thus 27.3%, while among those with follow-up the rate was 60%.

FIGURE 2.

This FNA of a cystic parotid mass demonstrated abundant mucin (A) and macrophages (B) without an evaluable epithelial component, categorized as atypical per MSRSGC. Follow-up revealed a low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma (C,D) [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

3.3.1 |. Category IVA: benign neoplasm

There were 242 cases (24.8% of total) that were diagnosed as a benign neoplasm by FNAC at MSKCC over the study period, all represented by three diagnoses: pleomorphic adenoma (52.1%, 126/242), Warthin tumor (47.5%, 115/242), and a single lipoma case. Of these, there were 92 cases with surgical follow-up. Of the 126 cases diagnosed as pleomorphic adenoma by FNAC, 76 (60.3%) were resected. Although the vast majority were confirmed as pleomorphic adenoma, there were 3 malignancies (1 low grade adenocarcinoma NOS, 1 polymorphous adenocarcinoma, and 1 myoepithelial carcinoma ex-PA). Of the 115 cases diagnosed as Warthin tumor by FNAC, 16 (13.9%) were resected, all confirming the diagnosis. The single lipoma case had no surgical follow-up. In total, the overall rate of malignancy for this category was 1.2% (3/242), while the rate among those with surgical follow-up was 3.3% (3/92).

3.3.2 |. Category IVB: salivary gland neoplasm of undetermined malignant potential

There were 135 cases that fit this category during the study period, representing 13.8% of overall cases. All had a primary diagnostic code of neoplastic, often with a descriptive note but without naming a specific entity. About half of these cases (54.1%, 73/135) ultimately had surgical follow-up. All were confirmed as neoplastic except a single case of cystic duct ectasia which was categorized as an oncocytic neoplasm. There were 37 malignancies among cases with follow-up. 35 of these were primary salivary gland malignancies, with the most common diagnoses being mucoepidermoid carcinoma (10 cases) followed by myoepithelial carcinoma (6 cases). The overall rate of malignancy for this category was thus 27.4% (37/135), while the rate among those with surgical follow-up was 50.7% (37/73).

3.3.3 |. Category V: suspicious for malignancy

There were 24 cases (2.5% of overall cases), which were signed out with a primary diagnostic code of suspicious for malignancy during the study period. Of these, 13 were diagnosed as suspicious for lymphoma, of which 9 were confirmed as lymphoma via flow cytometry or subsequent core biopsy. There were 10 cases that were suspicious for carcinoma, 5 of which had follow-up, all revealing carcinoma (3 carcinoma ex PAs and 2 mucoepidermoid carcinomas). A single case classified as suspicious for sarcoma was revealed to be an angiosarcoma on follow-up resection. The overall rate of malignancy for category V lesions was thus 62.5% (15/24), while the rate among cases with follow-up was 100% (15/15).

3.3.4 |. Category VI: positive for malignancy

There were 184 cases (18.9% of overall cases) diagnosed as malignant over the course of the study period. The most common entities diagnosed as malignant by FNAC included lymphoma (n = 40) followed by metastatic squamous cell carcinoma (n = 28), metastatic melanoma (n = 18), and metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma (n = 6). Among the primary salivary gland malignancies, the most common specific diagnoses included mucoepidermoid carcinoma (n = 6), acinic cell carcinoma (n = 6), and salivary duct carcinoma (n = 5). Of the cases diagnosed as malignant by FNAC, there were 111 confirmed as malignant via surgical follow-up, and an additional 22 cases confirmed as lymphoma via flow cytometry. None of the cases with follow-up were found to be false positives during the study period. The overall rate of malignancy was thus 60.3% (111/184) overall, while the rate among cases with follow-up was 100% (111/111).

4 |. DISCUSSION

Utilizing MSRSGC at our institution, salivary gland FNAC demonstrated test characteristics to those reported in other recent post-MSRSGC studies, which have reported sensitivities ranging from 57.7% to 80.1% and specificities ranging from 68.6% to 98%.11–14 Although we demonstrated a perfect PPV for malignancy, our NPV was somewhat lower (72.6%) than those previously reported for salivary gland FNAC.11–13 This is likely related to the high prevalence of malignancy in our patient population. The rate of malignancy among our subjects was 19.7% (192/976) for all-comers and 51.3% (192/374) for cases with follow-up. By comparison, in one of the largest studies of salivary gland FNAC with histologic follow-up to date, Rossi et al found a malignancy rate of 8.9% (154/1729) among all-comers and 21.7% (154/709) among those with follow-up.9 In a recent large study by Chen et al, these rates were 4.6% (47/1020) and 13.5% (47/349), respectively.11

One important observation regards the rate of malignancy in nonneoplastic FNA. The MSRSGC describes a risk of malignancy for all categories based on a comprehensive meta-analysis of 29 studies of FNA for salivary gland with histologic follow-up.6,15 One might infer that including only cases with surgical follow-up might select for those with a particularly high clinical suspicion of malignancy and that the quoted 25% risk of malignancy for the nondiagnostic category might thus overstate the true risk. In our analysis of the nondiagnostic category, we found a marked difference in the overall risk of malignancy (4.5%) compared with ROM for those cases with histologic follow-up (18.8%), which more closely reflected the risk quoted in the MSRSGC. Although the “true” ROM for a lesion called nondiagnostic by FNA likely lies between these two values, we believe it is likely better approximated by the former.

The application of MSRSGC guidelines resulted in a significantly higher rate of nondiagnostic salivary gland FNACs (14.5% vs the original 6.9%) due to the inclusion of cases with cyst contents or benign elements only. A similar finding was observed in a review of 164 salivary gland FNAC cases by Layfield et al, where reclassification using MSRSGC resulted in 29 nondiagnostic cases compared with just 2 using the original diagnostic scheme.16 Our series found the ROM among cases demonstrating cyst contents or benign elements only to be relatively low overall (2.6% and 6.4%, respectively), with a somewhat higher ROM among those with surgical follow-up (16.7% and 25%, respectively). These ROMs mirror those of other nondiagnostic cases, justifying their inclusion within this category. Still, it should be noted that the given the high prevalence of malignancy in our population, these relatively low ROMs suggest that a salivary gland lesion with a nondiagnostic FNAC may be considered a lower risk compared with its pretest probability before FNAC.

The most common causes of false-negative salivary gland FNAC at our institution was lymphoma, with 6 cases misdiagnosed as nonneoplastic by FNAC, roughly 10% of overall lymphoma cases. This result echoes that of several large studies, confirming lymphoma as a consistent cause of false-negative diagnoses in salivary gland FNAC.9,11,14 In light of this, in the absence of flow cytometric or other immunophenotypic evidence, the practicing cytopathologist should exercise caution in categorizing as nonneoplastic any salivary gland FNAC that shows a dominant population of lymphocytes.

The cases of carcinoma arising from prior pleomorphic adenomas were less likely to be categorized as malignant by FNAC than their de novo counterparts. Only four of six salivary duct carcinomas arising ex-PA were categorized as malignant by FNAC vs all five arising denovo. For myoepithelial carcinomas, three of eight de novo cases were diagnosed as malignant compared to neither of two arising ex-PA. Carcinoma ex-PA is a particularly challenging diagnosis for salivary gland FNAC and represents another significant cause of false-negative FNAC. In the study by Chen et al, carcinoma ex-PA represented 5 of 8 false-negative salivary gland FNACs, while in the study by Viswanathan et al it contributed to 4 of 13 false-negative FNACs (14).

Finally, while the nondiagnostic rate was lower when the FNA procedure was performed by pathologists vs nonpathologists (12.9% vs 15.8%), the rate was comparable between these groups when rapid on site evaluation (ROSE) was performed. When nonpathologists performed the procedure, the nondiagnostic rate was about three times higher for cases without ROSE (31.1%) compared with those with ROSE (11.6%). It thus appears that the most important factor for acquiring a diagnostic specimen was whether ROSE was performed at all rather than who was performing the procedure. These findings highlight the importance of ROSE when performing salivary gland FNA both to decrease the number of nondiagnostic specimens and false-negative cases.

5 |. CONCLUSION

We here apply the MSRSGC to 10 years worth of in-house salivary gland FNAC cases at a tertiary care cancer center. In our hands, salivary gland FNAC provided a relatively high specificity (87.4%) with only moderate sensitivity (65.6%) and—perhaps because of the high prevalence of disease in our patient population—perfect PPV (100%) and a relatively low NPV (72.6%) compared with prior studies. Among cases with follow-up, the Milan category with the lowest ROM was category IVa: benign neoplasm, with a rate of 3.3% (3/92). For the other categories, the ROM progressively increased as expected from a low of 20.7% (6/29) for category 1: nondiagnostic to 100% for both category V: suspicious for malignancy (15/15) and category VI: positive for malignancy (111/111). We found that following the MSRSGC criteria, we had a relatively high proportion of nondiagnostic cases (14.4%) and that moving cyst contents only or benign contents only to the nondiagnostic category had minimal impact on ROMs. The most common cause of false-negative diagnosis at our institution was lymphoma. We also found that ROSE was effective at limiting nondiagnostic rates among salivary gland FNAC cases.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE OF INTEREST

The authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial or nonfinancial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Del Signore AG, Megwalu UC. The rising incidence of major salivary gland cancer in the United States. Ear. Nose Throat J. 2017;96(3):E13–E13, E16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rossi ED, Faquin WC, Baloch Z, et al. The Milan system for reporting salivary gland cytopathology: analysis and suggestions of initial survey. Cancer Cytopathol. 2017;125(10):757–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colella G, Cannavale R, Flamminio F, Foschini MP. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of salivary gland lesions: a systematic review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg [Internet. 2010;68(9):2146–2153. Available from. 10.1016/j.joms.2009.09.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Layfield LJ, Gopez E, Hirschowitz S. Cost efficiency analysis for fine-needle aspiration in the workup of parotid and submandibular gland nodules. Diagn Cytopathol. 2006;34(11):734–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jinnin T, Kawata R, Higashino M, Nishikawa S, Terada T, Haginomori SI. Patterns of lymph node metastasis and the management of neck dissection for parotid carcinomas: a single-institute experience. Int J Clin Oncol [Internet. 2019;24(6):624–631. Available from. 10.1007/s10147-019-01411-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Faquin WC, Rossi ED, Baloch Z, et al. In: Faquin WC, Rosi ED, eds. The Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing AG; 2018:1–182. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Griffith CC, Pai RK, Schneider F, et al. Salivary gland tumor fine-needle aspiration cytology: a proposal for a risk stratification classification. Am J Clin Pathol. 2015;143(6):839–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klijanienko J, Vielh P. Fine-needle sampling of salivary gland lesions IV: review of 50 cases of mucoepidermoid carcinoma with histologic correlation. Diagn Cytopathol. 1997;17(2):92–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rossi ED, Wong LQ, Bizzarro T, et al. The impact of FNAC in the management of salivary gland lesions: institutional experiences leading to a risk-based classification scheme. Cancer Cytopathol. 2016;124(6):388–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malhotra P, Arora VK, Singh N, Bhatia A. Algorithm for cytological diagnosis of nonneoplastic lesions of the salivary glands. Diagn Cytopathol. 2005;33(2):90–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen Y-A, Wu C-Y, Yang C-S. Application of the Milan system for reporting salivary gland cytopathology: a retrospective 12-year bi-institutional study. AmJ Clin Pathol. 2019;151(6):613–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hollyfield JM, O'Connor SM, Maygarden SJ, et al. Northern Italy in the American south: assessing interobserver reliability within the Milan system for reporting salivary gland cytopathology. Cancer Cytopathol. 2018;126(6):390–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thiryayi SA, Low YX, Shelton D, Narine N, Slater D, Rana DN. A retrospective 3-year study of salivary gland FNAC with categorisation using the Milan reporting system. Cytopathology. 2018;29(4): 343–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Viswanathan K, Sung S, Scognamiglio T, Yang GCH, Siddiqui MT, Rao RA. The role of the Milan system for reporting salivary gland cytopathology: a 5-year institutional experience. Cancer Cytopathol. 2018;126(8):541–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wei S, Layfield LJ, LiVolsi VA, Montone KT, Baloch ZW. Reporting of fine needle aspiration (FNA) specimens of salivary gland lesions: a comprehensive review. Diagn Cytopathol. 2017;45(9): 820–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Layfield LJ, Baloch ZW, Hirschowitz SL, Rossi ED. Impact on clinical follow-up of the Milan system for salivary gland cytology: a comparison with a traditional diagnostic classification. Cytopathology. 2018; 29(4):335–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]