Abstract

Advance directives are documents to convey patients’ preferences in the event they are unable to communicate them. Patients commonly present to the emergency department near the end of life. Advance directives are an important component of patient‐centered care and allow the health care team to treat patients in accordance with their wishes. Common types of advance directives include living wills, health care power of attorney, Do Not Resuscitate orders, and Physician (or Medical) Orders for Life‐Sustaining Treatment (POLST or MOLST). Pitfalls to use of advance directives include confusion regarding the documents themselves, their availability, their accuracy, and agreement between documentation and stated bedside wishes on the part of the patient and family members. Limitations of the documents, as well as approaches to addressing discrepant goals of care, are discussed.

Keywords: advance directives, emergency medicine, DNR, POLST, living will

1. INTRODUCTION

Advance directives can be confusing for patients and physicians, alike. Patients may lack a clear understanding of the implications of the documents they sign. Although advance directives are intended to clarify a patient's end‐of‐life wishes, physicians frequently find themselves struggling to reconcile bedside requests for care with those outlined in the documents with which they are presented. This paper describes advance directives frequently encountered in the emergency department setting. Limitations of the documents, as well as approaches to addressing discrepant goals of care, are discussed.

2. TYPES OF ADVANCE DIRECTIVES

The most common advance directives encountered in the ED are living wills, health care proxies, and Do Not Resuscitate orders. As of September 2019, 48 US states are actively participating in Physician (or Medical) Orders for Life‐Sustaining Treatment (POLST or MOLST) or Medical Orders for Sustaining Treatment (MOST). 1 , 2 Venkat and Becker provide a detailed assessment and review of state laws pertaining to the authority of substitute decision makers in all 50 US states and the District of Columbia. 3 , 4 Understanding the terms and limitations of these documents can assist physicians in their bedside discussions with patients and families.

2.1. Living Wills

The living will allows patients to document treatment options they wish to pursue if terminally ill or injured. Specifications regarding life support measures, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), defibrillation, ventilation, dialysis, and artificial hydration and nutrition are common components of the living will. Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) direction also may be included, but generally requires separate DNR documentation. Living wills provide the opportunity for the patient to define what she believes constitutes quality of life with regard to standards of personal health and comfort during a medical emergency or personal illness.

Living wills provide good guidance for the treatment of those in a persistent vegetative state, for those with debilitating disease, or for those who clearly wish to have comfort care only. They are more nebulous, however, with regard to acute care situations, especially those encountered in the ED. Although it may be clear that a patient does not wish for long‐term dependence on a ventilator, that same patient might benefit from short‐term ventilation with diuresis to treat an acute exacerbation of congestive heart failure, for example. Living wills do not direct physicians adequately in situations where the physician can foresee benefit to a short‐term medical intervention that a patient would otherwise reject for the long‐term. Further, physicians may not be able to predict how quickly a patient might recuperate from an acute medical insult. Patients with end‐stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease may recover quickly or may be unable to be weaned from the ventilator.

2.2. Health care proxies

Establishing exactly who should be making decisions on behalf of the patient is important. At times, the family member who presents with the patient may not be the legal medical proxy. Patients may designate health care proxies using a Durable Power of Attorney for Health Care Form, granting power to make health care decisions on behalf of the patient, when the patient is rendered incapacitated by illness or injury. When facing real‐time, critical decisions in the ED, physicians may need to rely on those who do not legally represent the patient as proxy, but who are familiar with the patient's wishes. Health care proxies only function at times when patients lack capacity, so determining when a patient lacks capacity for health care decision making is key.

2.3. Do not resuscitate

Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) orders vary by state, which only adds to the confusion of how to honor advance directives. Physicians who practice close to state borders may be unable to honor the DNR orders of patients from out of state. Further, many states do not recognize living wills or health care proxies in the out‐of‐hospital setting. Emergency medical system (EMS) personnel may be required to initiate resuscitative measures, unless state‐approved documentation can be provided. This can be distressing to family members who wish to terminate resuscitative measures.

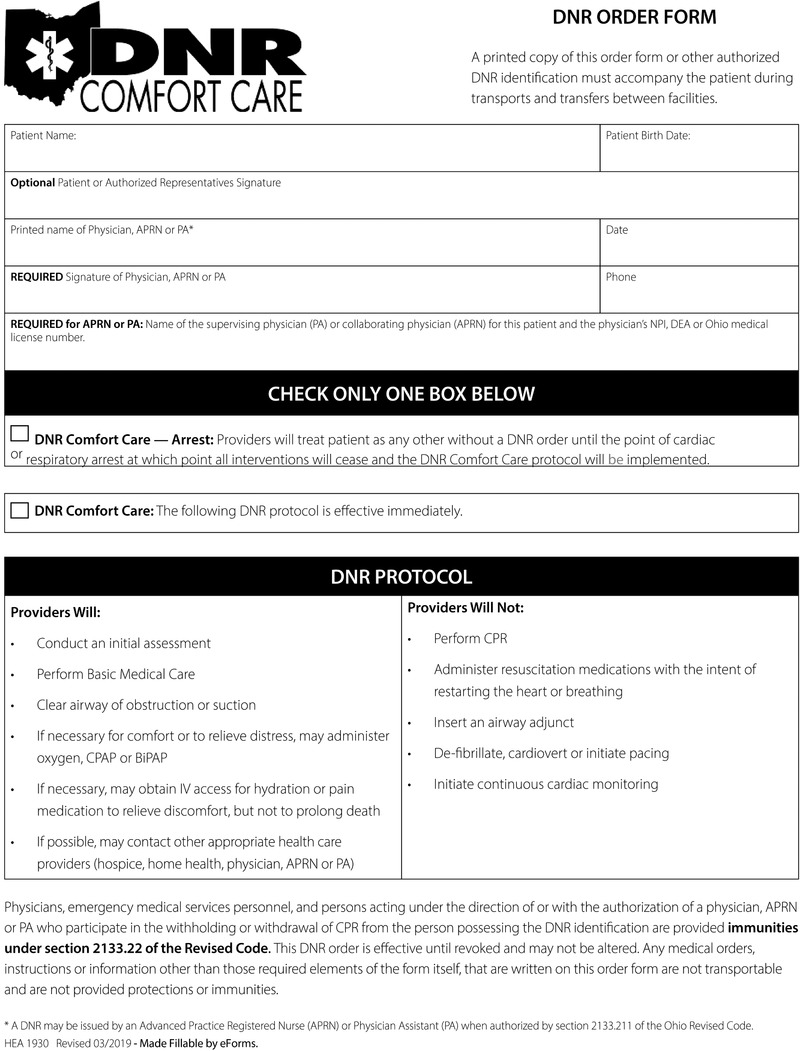

Many families do not realize that DNR orders are not the same as living wills. They may present the emergency physician with a living will, thinking that it details the wishes of the patient for resuscitation. But eschewing long‐term maintenance on a ventilator or other life‐support is quite different from directions to initiate or withhold pressors, intubation, pressure support ventilation, or other potentially short‐term interventions. DNR forms may specify those measures that will or will not be performed, under the DNR order. This may include not administering chest compressions, resuscitative drugs, defibrillation, artificial airways, and cardiac monitoring. Under “comfort care” protocols, suctioning of the airway, oxygen administration, bleeding, control, splinting, and emotional support may be provided. Knowledge of state law is critical to the appropriate enactment of a DNR order. An example of Ohio DNR law is shown in Figure 1. 5

FIGURE 1.

Ohio Do Not Resuscitate Form.

Credit: Figure reproduced with the permission from the Ohio Dept of Health 8

Despite such details, the extent to which patients wish to be resuscitated (if not a “full code”) can be difficult to ascertain. Frequently, misunderstandings about DNR documents lead patients to fear that “do not resuscitate” means “do not treat.” They worry that signing a DNR order condemns them to suffering from painful conditions at the end of life. Conversely, physicians can be confused by orders such as “comfort care‐arrest” or “slow code” protocols that ostensibly entail full resuscitative measures until the patient succumbs to cardiopulmonary arrest. Knowing how aggressively to treat the critically ill patient can be daunting. Finally, laymen lack an understanding of the realities of resuscitation. The majority of patients in full cardiopulmonary arrest cannot be resuscitated or returned to their previous functional status. Television depictions of CPR and other resuscitative measures paint a very different picture. For example, Grey's Anatomy and House show CPR to be life‐saving 70% of the time, while in reality CPR succeeds only 37% of the time. Furthermore, only 13% of patients survive to leave the hospital after CPR. 6 Enlightening patients who are signing DNR orders would be helpful, but may not be done by primary care physicians. Often, explaining the prognosis of resuscitative efforts to family members at the bedside falls to the emergency physician.

2.4. POLST/MOLST

One document with the potential to alleviate confusion about resuscitative measures is the Physician (or Medical) Orders for Life‐Sustaining Treatment form. POLST are portable medical orders designed to assist health care providers to implement patient medical wishes, by translating them into medical orders to be followed in both in patient and out‐patient settings. 7 As of September, 2019, three programs are “mature,” a designation by the National POLST Paradigm reserved solely for programs where use of POLST is statewide and part of the standard of care for appropriate persons. Nineteen states and the District of Columbia are “endorsed,” that is, actively participating in National POLST governance and meeting the National POLST standards. There are 24 “active” programs, which are at various stages of development, working towards implementing POLST statewide. Seven states’ programs are “unaffiliated,” which does not indicate the level of development of POLST in that state, but rather that the National POLST Paradigm does not confer a designation on it. 2 , 7

POLST orders contain five sections, detailing instructions for CPR, medical interventions, antibiotics, artificially administered nutrition, and reasoning for orders with signatures. POLST, like DNR, is an actionable medical order, signed by both a health care provider and the patient or medical proxy. It is designed to be portable to all healthcare settings, rather than to apply only as an outpatient or inpatient. A key feature is its emphasis on goals of care, from full treatment to limited treatments short of those employed in intensive care, as well as comfort measures. Treatment plans conforming to the patient's wishes are more easily formulated, due to the specific language of the POLST document. 9 POLST forms are primarily intended for those who are seriously ill or frail, with advanced, chronic, or progressive life‐limiting illness, or anyone with strong treatment preferences. 4 , 7

3. PEARLS AND PITFALLS OF ADVANCE DIRECTIVES IN THE EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT

3.1. Lack of advance directives

Unfortunately, most ED patients do not have advance directives. It has been estimated that only 7%–42% of Americans have a completed advance directive. 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 Without advance directives, families and providers may erroneously assume inaccurate end‐of‐life wishes. 17 , 18 , 19 , 20

3.2. Availability

Availability of advance directive documents may be limited in the ED environment. Some patients may have documentation in the medical record; however, this documentation may not be current. 21 Often, families do not have the appropriate documentation when the patient and family arrive in the ED.

3.3. Accuracy and interpretation of advance directives

With all advance directives, a patient with decision making capacity can change or revoke his/her previously documented orders. Times when a health care proxy can revise or rescind such orders is less clear. It is not unusual, at the bedside, for emergency physicians to find themselves confronted with confusing documents, or with documents that contradict the wishes expressed by the surrogate decision maker. The situation is made even more difficult when the legal health care proxy is absent, or when patients have never discussed their wishes for end‐life care with their family. When such documents are absent, physicians should ascertain patients’ wishes through bedside discussion with the patient and family members (regardless of proxy status). States typically designate spouses as proxy decision makers, followed by children and siblings, where appropriate. Importantly, some states make a clear distinction between the authority of the health care power of attorney versus the next‐of‐kin to make decisions regarding withholding and withdrawing care. 3 Parents or guardians serve as decision makers for minors, although teens or “mature minors” may possess legal standing for medical decision making in some circumstances. Making such difficult decisions at the bedside is never ideal. In general, however, physicians enjoy medical‐legal protection when following advance directives in good faith. 1

Patients and families may not agree regarding the application of advance directives to clinical scenarios, for example, trauma, surgery, or other clinical settings. 22 This underscores the importance of a discussion to ascertain the accuracy of advance directives, and the appropriate application to the clinical setting.

4. ADDRESSING PATIENT AND FAMILY PREFERENCES FOR END‐OF‐LIFE CARE IN THE EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT

Despite the importance of advance directives, many patients do not have an advance directive, the advance directive may not be available or may not be current. These pitfalls underscore the importance of a valid discussion in the ED of the patient's preferences for end‐of‐life care.

If patients are able to communicate, their wishes should be established. Patient wishes should be discussed in an open, honest, and compassionate manner. Patients should be assured that medical treatment will be provided to maintain comfort and dignity. Previous advance directives should be verified, and if valid and confirmed, they should be followed. If there is no advance directive, providers should provide information regarding the disease process, prognosis, and treatment alternatives.

For some patients, hospice placement from the ED is a preferable option for appropriate end‐of‐life care. 23

If the patient is unable to communicate, advance directives should guide care. If there is no advance directive, families may be asked about the patient wishes. It is important to ascertain the patient wishes as expressed to or known by the family, not personal wishes of family members.

At times, there may be disagreement about the best medical treatment and level of invasive and aggressive medical care at the end of life. There may be disagreement among family members, or disagreement with the treating physician. When there is a lack of agreement, communication should aim to develop consensus about the best course of action that is consistent with patient goals and values. The American Medical Association Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs recommends a process‐based approach to addressing discrepant goals of care 24 : Bear in mind that due to time constraints, not all of these elements may be feasible in the emergency department setting.

Deliberation and resolution.

Joint decision making with physician and patient or proxy.

Assistance of a consultant or patient representative.

Utilization of an institutional committee (ie, ethics committee)

American College of Emergency Physicians Policy on Ethical Issues at the End of Life provides important guidance for emergency physicians (Table 1). 25 Table 2, 26 provides advice on the treatment of patients who present in extremis without an advance directive.

Table 1.

ACEP Policy Statement: Ethical Issues at the End of Life

| The American College of Emergency Physicians believes that: |

|

| To enhance EOL care in the ED, the American College of Emergency Physicians believes that emergency physicians should: |

|

Table 2.

Bedside emergency department approach to patients in extremis, without an advance directive a

|

|

|

|

|

|

Adapted from: Episode 70 End of Life Care in Emergency Medicine. Emergency Medicine Cases. https://emergencymedicinecases.com/end-of-life-care-in-emergency-medicine/, accessed October 17, 2019.

5. CONCLUSIONS

With advance directives, patients communicate end‐of‐life wishes. Despite such intentions, confusion regarding the documents themselves, their availability, their accuracy, and agreement between documentation and stated bedside wishes are not uncommon. Physicians should discuss treatment options in an open, honest, and compassionate manner. Patients should be assured that medical treatment will be provided to maintain comfort and dignity. Valid advance directives should be followed, in the absence of advance directives, providers should provide information regarding the disease process, prognosis, and treatment alternatives to the patient and family to guide care. No conflicts to declare.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author declare no conflict of interest.

Biography

Eileen Baker is an emergency physician with Riverwood Emergency Services, Inc, and is Medical Director, Medical Student Ethics Curriculum, University of Toledo College of Medicine and Life Sciences.

Baker EF, Marco CA. Advance directives in the emergency department. JACEP Open. 2020;1:270–275. 10.1002/emp2.12021

Supervising Editor: Mike Wells, MBBCh, PhD.

Funding and support: By JACEP Open policy, all authors are required to disclose any and all commercial, financial, and other relationships in any way related to the subject of this article as per ICMJE conflict of interest guidelines (see www.icmje.org). The authors have stated that no such relationships exist.

REFERENCES

- 1.National POLST Program Designations As of October 2019. Available at: https://polst.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/2019.10.04-National-POLST-Program-Designations-Map.pdf, Accessed October 15, 2019.

- 2. Tark A, Agarwal M, Dick AW, Stone PW. Variation in POLST across the nation: environmental scan. J Palliat Med 2019;22:1032‐1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Venkat A, Becker J. The effect of statutory limitations on the authority of substitute decision makers on the care of patients in the intensive care unit: case examples and review of state laws affecting withdrawing or withholding life‐sustaining treatment. J Intensive Care Med. 2014;29:71‐80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jesus JE, Geiderman JM, Venkat A, et al. Physician Orders for Life‐Sustaining Treatment (POLST): ethical considerations, legal issues, and emerging trends. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;64:140‐144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohio DNR Identification Form. Available at: https://eforms.com/download/2018/02/Ohio-DNR-Form.pdf. Accessed October 24, 2019.

- 6. Science Daily . CPR: It's not always a lifesaver, but it plays one on TV. August 28, 2015. Available at: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2015/08/150828135219.htm. Accessed October 9, 2019.

- 7. American College of Emergency Physicians, “Guidelines for Emergency Physicians on the Interpretation of Physician Orders for Life‐Sustaining Treatment (POLST),” Policy Statement, April 2017. Available at: https://www.acep.org/globalassets/new-pdfs/policy-statements/guidelines.emergency.physicians.on.interpretation.physician.orders.for.life-sustaining.treatment.pdf. Accessed October 8, 2019.

- 8. https://odh.ohio.gov/wps/wcm/connect/gov/9660690e-44bf-4c71-b7bd-2310f9b644e7/DNR%2Bcomfort%2Bcare%2Bform1.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CONVERT_TO=url&CACHEID=ROOTWORKSPACE.Z18_M1HGGIK0N0JO00QO9DDDDM3000-9660690e-44bf-4c71-b7bd-2310f9b644e7-mSn9I9G.

- 9.National POLST Form. Available at: https://polst.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/2019.09.02-National-POLST-Form-with-Instructions.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2019.

- 10. Rao JK, Anderson LA, Lin F‐C, Laux JP. Completion of advance directives among U.S. consumers. American J Prevent Med. 2014;46:65‐70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Reuter PG, Agostinucci JM, Bertrand P, et al. Prevalence of advance directives and impact on advanced life support in out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest victims. Resuscitation. 2017;116:105‐108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gamerstfelder EM, Seaman JB, Tate J, et al. Prevalence of advance directives among older adults admitted to intensive care units and requiring mechanical ventilation. J Gerontol Nurs. 2016;42:34‐41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nathens AB, Rivara FP, Wang J, Mackenzie EJ, Jurkovich GJ. Variation in the rates of do not resuscitate orders after major trauma and the impact of intensive care unit environment. J Trauma. 2008;64:81‐88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Adams SD, Cotton BA, Wade CE, et al. Do not resuscitate status, not age, affects outcomes after injury: an evaluation of 15,227 consecutive trauma patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74:1327‐1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Elsayem AF, Bruera E, Valentine A, et al. Advance directives, hospitalization, and survival among advanced cancer patients with delirium presenting to the emergency department: a prospective study. Oncologist. 2017;22:1368‐1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Taylor DM, Ugoni AM, Cameron PA, McNeil JJ. Advance directives and emergency department patients: owners rates and perceptions of use. Intern Med J 2003;33:586‐92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wenger NS, Phillips RS, Teno JM, et al. Physician understanding of patient resuscitation preferences: insights and clinical implications. J.Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:S44‐51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Golin CE, Wenger NS, Liu H, et al. A prospectives study of patient‐physician communication about resuscitation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:S52‐60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fischer GS, Tulsky JA, Rose MR, Siminoff LA, Arnold RM. Patient knowledge and physician predictions of treatment preferences after discussion of advance directives. J Gen Intern Med 1998,13:447‐454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Beach MC, Morrison RS. The effect of do‐not‐resuscitate orders on physician decision‐making. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:2057‐2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Grudzen CR, Buonocore P, Steinberg J, et al. AAHPM Research Committee Writing Group. Concordance of advance care plans with inpatient directives in the electronic medical record for older patients admitted from the emergency department. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51:647‐651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Marco CA, Mozeleski E, Mann D, et al. Advance directives in emergency medicine: patient perspectives and application to clinical scenarios. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36:516‐518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liberman T, Kozikowski A, Kwon N, et al. Identifying advanced illness patients in the emergency department and having goals‐of‐care discussions to assist with early hospice referral. J Emerg Med. 2018;54:191‐197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Medical futility in end‐of‐life care: report of the Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs. JAMA. 1999;10:937‐41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. American College of Emergency Physicians: Ethical Issues at the End of Life. Available at: https://www.acep.org/patient-care/policy-statements/ethical-issues-at-the-end-of-life/. Accessed 10/16/2019. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adapted from: Episode 70 End of Life Care in Emergency Medicine. Emergency Medicine Cases. Available at: https://emergencymedicinecases.com/end-of-life-care-in-emergency-medicine/. Accessed October 17, 2019.