Abstract

The second COVID-19 wave is sweeping the globe as restrictions are lifted. Malta, the ‘poster child of Europe’s COVID-19 first wave success’ also fell victim shortly after it welcomed the first tourists on 1st of July 2020. Only four positive cases were reported over the successive 15 days. Stability was disrupted when two major mass events were organized despite various health professional warnings. In a matter of few just days, daily cases rose to two-digit figures, with high community transmission, a drastic rise in active cases, and a rate per hundred thousand in Europe second only to Spain. Frontliners were swamped with swabbing requests while trying to sustain robust case management, contact tracing and follow-up. Indeed, the number of hospitalizations and the need for intensive ventilation increased. Despite the initial cases were among young adults, within weeks a small spill off on the more elderly population was observed. Restrictions were re-introduced including mandatory mask wearing in specific locations and capping of the total number of people in a single gathering. Malta is an island and the potential for containment would have been relatively simple and effective and permitting mass gatherings was unwise. Protecting the health of the population should take centre stage while carrying out extensive testing, contact tracing and surveillance. Containment and mitigation along with public cooperation is the key to curbing resurgences especially with the influenza season around the corner.

Keywords: Coronavirus, Pandemics, Economy, Prevention, Population health, Population surveillance, Malta

Introduction

The seminal year 2020 revealed humanity’s vulnerability to pandemics as the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) spread from Wuhan, China, in December 2019 to the rest of the world resulting in a global World Health Organisation Public Health Emergency [1], World Health Organization [2]. Every country struggled to contain the first viral wave, with some countries showing more capability and resilience than others. The small European country of Malta was well prepared for the first wave and exhibited a laudable and successful containment effort originating from the collective efforts of the Public Health authorities, the government along with the general population [3]. This put Malta into the spotlight, with praises from prominent statesmen including the WHO Regional Director for Europe Dr. Hans Kluge and the Commonwealth General Secretary, who stated “[Malta] has done the best in the whole of Europe” (CDE [4, 5]. By end of May 2020, Malta appeared to have reach the trough of the first COVID-19 wave, with minimal sporadic cases being reported (a mean of 2 cases over a month) up till mid-June. This was followed by a number of consecutive days without any identified cases despite the high swabbing rate [6] (Fig. 1). During the first COVID-19 wave, the Superintendent of Public Health used to give a daily briefing that was well accepted and appreciated by the population, however these briefings were reduced to three times a week and then stopped when Malta moved into the ‘transition phase’ [7, 8]. Ongoing media intervention continued for the promotion of mitigation measures which remained in place though transition phase. This transition period into a “new normal” brought with it the lifting of previously imposed restrictions in an attempt to restart the national economy.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of the 7-day average moving timeline of the positive cases since March 2020

Raising of Restrictions

The ports and airport opened to a limited number of safe corridor countries on 1st July 2020, after 4 months of being closed [9]. It was accompanied by the lifting of the state of “Public Health Emergency” as well as the end of the restricted number of people in organised and spontaneous mass gatherings [10]. After the first week of the re-opening of the airport, 20,000 passengers had landed in Malta [11]. A number of public health measures were implemented at Malta International Airport including the mandatory wearing of masks, thermal temperature screening on arrival and departure, advocating for regular sanitization of hands and maintaining social distancing [12]. The COVID-19 situation appeared stable with only four positive cases being reported over a 15 days period, two of which were imported cases [13]. The Maltese economy started to pick up as residents and tourists alike visited restaurants, shops and cultural sights. Furthermore, as happened in other countries, a government economy stimulus package in the form of vouchers were distributed to all inhabitants in Malta as to encourage the restart of the economy [14]. On the 15th of July, further travel restrictions were lifted as more flights were re-instated to even more countries [15]. This followed the European Commission recommendation for the opening up of all borders to other member states and a list of third countries. No pre-screening was required of tourists even those originating from countries with higher rates than Malta.

An Avoidable Debacle

The stable status quo hit a stumbling block when two major mass events were organized despite the various health professional warnings and concerns about such events. Concurrently, Malta was being advertised by the Malta Tourism Authority as the “Island festival hotspot” attracting young adults from across Europe particularly while other countries had restricted such organised mass events [16]. During the weekend of 17 – 19 July 2020, a hotel “pool party” was attended by approximately 800 people. Two days down the line the COVID-19 situation went out of control, breaking the contained virus chain [17, 18]. Less than a week later, another organized mass gathering occurred as part of an annual Catholic Saint feast celebrations resulted in another cluster of COVID-19 spread within the community [19]. Additionally, other religious feasts also took place while a number of discotheques and bars were open without restrictions. In a matter of few days, the daily reported zero COVID-19 cases shoot up to two-digit figures and the number of active cases increased. Indeed, COVID-19 is currently being exacerbated worldwide by irresponsible behaviour at all ages, and adolescents with their propensity to party are major culprits [20–22].

Swabbing requests by the party/feast attendees and their contacts soared. For the first time since the initial COVID-19 outbreak in Malta, the swabbing centres were overwhelmed, with appointments scheduled for more than 7 days from the individual’s call to the COVID-19 helpline [23]. Within a short time, the number of hubs increased from four to six, as another two new swabbing hubs were opened [7, 18, 24–28] with the situation or symptomatic cases being given an appointment for testing within 24 h.

Inconsistent messages were disseminated to the population from some sectors outside health reassuring the public that “everything is under control” and “Malta is open for business” gave false signals that COVID-19 was over and all touristic activities could resume without limitation. Concurrently the Superintendent of Public Health along with the Minster of Health continued to emphasise to the public the importance of remaining vigilant and maintain social distancing etc. [27]. This resulted in an uproar by the medical professionals and others. The medical doctors association issued industrial actions that stopped all elective healthcare services unless mass gatherings were banned by the government [29]. Concurrently, the Superintendent of Public Health office along with the Maltese government issued ‘Standards for Gatherings’ mitigation standards, followed by a legal notice through the Public Health Act imposing a fine of 3,000 euro if these standards were breached by organizers [30]. A number of festivals and organised mass events cancelled in light of these mitigation standards, but events were still not banned completely as events up to 100 indoor and 300 outdoors could occur [31–34]. Indeed, another cluster of COVID-19 cases was established in early August 2020, originating mostly from Malta’s nightclub-disco area of Paceville [13].

The Second COVID-19 Wave

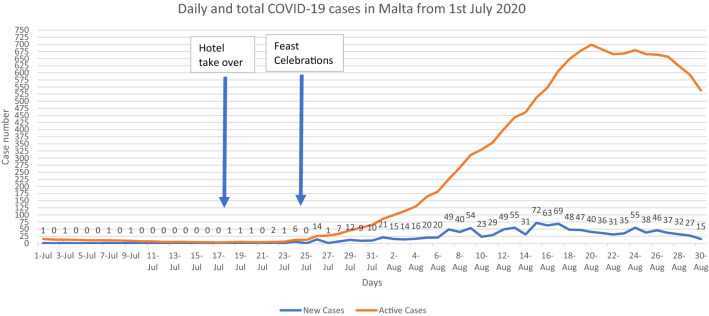

A steep rise in daily cases was reported just 15 days after the first organised mass event as seen in Fig. 2. The R factor rose beyond 1 as the case load rose, with R transiently exceeding 2 [26]. This sudden surge in cases exerted additional strain on the public health authorities in dealing with the bombardment of calls by the public through the COVID-19 helpline, the number of swabbing requests by both symptomatic and concerned individuals along with the attempt to sustain a robust case management, contact tracing and follow-up.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of the daily and total active COVID-19 cases in Malta as of 1st July 2020 [35]. *As reported by the official COVID-19 figures by Ministry of Health. The reminder clusters are as reported during the weekly COVID-19 Media Briefing

The Malta Association of Public Health Medicine (MAPHM) issued a press released following the onset of the second wave noting that:

This is the highest incidence of cases since the beginning of April, surpassing previous numbers, with many of the cases linked to mass events, parties or socializing in crowded areas … This was not inevitable. Nor was it unforeseen. These numbers are a direct consequence of irresponsible political behaviour, disregard of scientific evidence, and conflicting messages pushed by prominent personalities which led to inadequate physical distancing, infrequent and incorrect use of masks and disregard of public health recommendations….Three weeks after lifting most measures and – almost uniquely in the EU – allowing mass events to go ahead as if the battle against COVID-19 had been won, we are right back where we started… Health professionals’ advice has been consistent from the start. Lifting and reintroducing restrictive measures in response to observations remains the only ‘safe’ way to manage this epidemic. Masks should be worn in all public places, frequent hand washing observed, physical distance maintained wherever possible, and crowds of people limited to the smallest numbers possible. In this, our political leaders should lead by example, encouraging the population to adopt these behaviours, and allocating sufficient resources to enforce these regulations. Sectors which have adopted public health guidance have not been disrupted with clusters of COVID-19. In rare instances where outbreaks were identified, they were quickly brought under control” [36, 37].

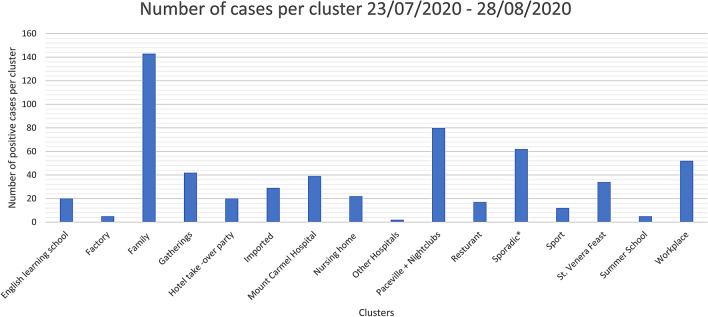

As cases continued to accumulate, clusters began to be identified by the ‘COVID-19 Public Health Response Team’ as part of the contact tracing system (Fig. 3) [35]. Although mass events were the triggering factors to the resurgence of the virus in Malta, it was now obvious that a high community spread was present. The average age of positive cases was observed to shift from 24.3 years (16 to 22 July 2020) to 38.7 years (13 to 19th August 2020) to 40.5 yeas (20 to 26th August 2020) [35]. In fact a spill of COVID-19 from the young to the elderly was recorded [38], leading to an increase in hospitalization and invasive ventilation, as seen in Table 1 (ICU) [35] although the number of hospitalization was relatively low when compared to other countries. Of note, outsourced hospitals (Boffa and St. Thomas) were used to cater for those positive cases that are clinical stable but were unable to return home due to social reasons. The tenth COVID-19 death was announced on the 21st August after 3 months without any COVID-19 related mortality while eight days later the eleventh death was announced, followed by the twelfth death a day later [39, 40]. During the month of August, it was noted that around 20% of the positive cases did not exhibit any symptoms [25].

Fig. 3.

Table 1.

Distribution of positive cases between institutions and the community in August 2020

| 7th August | 14th August | 17th August | 21st August | 28th August | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infectious Diseases Unit | 4 | 5 | 9 | 4 | 5 |

| Intensive Care Unit (ITU) | 0 | 3# | 2## | 3### | 3## |

| COVID-19 wards | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 0 |

| Boffa Hospital* | 7 | 16 | 13 | 17 | 14 |

| St. Thomas Hospital* | 5 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 14 |

| Community | 295 | 468 | 566 | 643 | 557 |

*Individuals do not require medical treatment but cannot go home due to social reasons

#1 on ventilator, rest on oxygen therapy only

##On oxygen therapy only

###On ventilators

A high swabbing rate had been instituted from the onset of COVID-19 in Malta in March [3]. To date (1st September 2020) a total of 192,509 swabs have been recorded. On the 17th of August, Malta was reported to be the third highest swabbing country in the world after the Gulf region and Bahrain [42]. Since the onset of the second wave, an average of 1.5% of the daily swabs were positive cases.

The new second wave restrictions

On the 7th of August 2020, a re-introduction of restrictions were announced, which included: (i) the banning of events of more than 100 people indoors and 300 people outdoors; (ii) reduction of hospital visits, only one family member was permitted to visit the sick daily (iii) visits to the elderly at residential homes could only be done behind Perspex on a roster basis; (iv) dance floors were to be shut down and (v) a €50 fine was introduced for those found not wearing a mask while using public transport and while in shops [43, 44]. On the same day, the Superintendent of Public Health was once again started to give weekly briefings on the COVID-19 situation [45]. Ten days later (17th August 2020), the second set of restrictions were introduced [46, 47] following the persistent incline in daily COVID-19 cases. These restrictions included (i) the closure of bars and nightclubs excluding those that include a restaurant, (ii) the banning of boat parties (iii) wedding receptions may only be held in a seated environment while following restaurant pre-instated restrictions, (as from the 28th August) (iv) the mandatory wearing of masks in all closed public spaces, the exception being restaurants, (v) a new 'amber' list of countries, arrivals from which need to produce COVID-19 negative test result [46]. The imposition of these restrictions saw the positive cases start to decline as observed in Fig. 2.

Impact on the Economy

Like the rest of the world, one of the main scopes in lifting the instituted preventive restrictions in Malta between May and June 2020, was to re-start the economy. Such actions were anticipated to lead to an increase in COVID-19 cases with the risk of precipitating a second and further waves [48]. The key to success is in the ability of government to strike the difficult balance between stimulating the economy and luring tourists to the country while maintaining a low morbidity/mortality [49]. What was perceived as an economic benefit turned into an nightmare for the tourism industry as a substantial number of European countries (Belgium, Cyprus, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Greece, Latvia, Lithuania, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, the UK, Slovenia and Switzerland) and the US labelled Malta as a “high risk” country. These countries imposed travel restrictions on visitors arriving from Malta with many potential tourists cancelled their sojourn [50]. Matters were further exacerbated when the UK announced the introduction of these travel restrictions [51]. This is expected to exert a significant impact on the Maltese economy, especially since the UK is Malta’s largest tourism market, followed by Italy.

Besides lost revenue from tourism, the second wave led to challenges imposed on the healthcare system due to a literal tripling of the swabbing rate, COVID-19 admissions and ICU stays, the usage of offsite locations to house patients and health care workers who needed to be quarantined due to inadvertent exposure to COVID-19.

Curbing the Spread and the Way Forward

In a matter of days, Malta rapidly transitioned from the ‘poster child of Europe’s COVID-19 success’ to a high-risk country. Malta is an island and the potential for containment could have been relatively simple and effective [52]. The combination of the influx of tourists, relaxation of social distancing measures, lack of coherence with mitigation standards in place after relaxation of measures, irresponsible behavior especially amongst youths and mass events produces the "lethal cocktail" and onset of the second wave in Malta. Permitting mass gatherings without imposing a restriction to the number of attendees carried an unprecedented high risk. In the mist of COVID-19, mass gatherings have been defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a “high density of individuals present in a venue for a defined period of time, which can amplify transmission of COVID-19, and place additional strain on a country’s healthcare system”[53]. This issue was alerted on by the Public Health authorities as a high risk. In fact, a risk assessment tool was created by the WHO in order to assess a country’s situation and aid in the mitigation of the organization of mass gatherings [54]. Amidst the surge in cases and hospitlization, the infection fatality rate remains very low and the healthcare system, up till date of writing, is coping well.

Conclusion

Protecting the health of the population should take centre stage during these unprecedent times and as Joseph Wu from the University of Hong Kong stated, “it all depends on how much social mixing resumes and what kind of prevention we do” [55]. The prime factor in curbing the viral spread is to gain the population trust and continue to advocate for strict hand hygiene, social distancing and wearing masks while protecting the vulnerable [56, 57]. As observed in Malta, a spill off of the viral infection is affecting the elderly population. It has been reported that people beyond 70 years contribute to the highest disability adjusted life years (DALYs) out of the total DALYs if infected by COVID-19 [58]. This needs to be backed by tailored mitigations and restrictions if and as the need arises, while extensively undergoing rigorous testing, contact tracing covering at least 80% of the COVD-19 positive cases contacts and surveillance of the situation [55]. Ultimately, we are all in this pandemic together, and prevention, containment and mitigation along with public cooperation is the key especially with the influenza season around the corner.

Funding

No funding was achieved.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

Authors declare no conflict of interests.

Ethical Approval

No ethical clearance was required since this is a narrative report.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet (London, England) 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. (2020c, March 16). WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 16 March 2020. Retrieved April 15, 2020, from https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---16-march-2020

- 3.Cuschieri S. COVID-19 panic, solidarity and equity—the Malta exemplary experience. Journal of Public Health. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10389-020-01308-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CDE News. (2020). Commonwealth General Secretary says that Malta has done the best in the whole of Europe. Retrieved June 3, 2020, from https://corporatedispatch.com/commonwealth-general-secretary-says-that-malta-has-done-the-best-in-the-whole-of-europe/

- 5.Grech Urpani, D. (2020, March 28). “An Example To Follow”: WHO Europe Regional Director Gives Shout-Out To Malta’s COVID-19 Measures. Retrieved April 15, 2020, from https://lovinmalta.com/news/news-international/an-example-to-follow-who-europe-regional-director-gives-shout-out-to-maltas-covid-19-measures/

- 6.Our World in Data. (2020). Coronavirus (COVID-19) Testing - Statistics and Research - Our World in Data. Retrieved August 30, 2020, from https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus-testing

- 7.Caruana, C. (2020c). Health briefings that made Charmaine Gauci a household name end. Retrieved June 9, 2020, from https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/health-briefings-that-made-charmaine-gauci-a-household-name-end.796245

- 8.Costa, M. (2020). Charmaine Gauci’s COVID-19 updates will now take place three times a week. Retrieved June 9, 2020, from https://www.maltatoday.com.mt/news/national/102421/charmaine_gaucis_covid19_updates_will_now_take_place_three_times_a_week#.Xt9h5i2w0cg

- 9.Borg, J. (2020a). Bars, gyms to reopen Friday, airport, ports in July—Robert Abela. Retrieved June 9, 2020, from https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/bars-gyms-to-re-open-friday-airport-ports-in-july-robert-abela.795559

- 10.Times of Malta. (2020f). Coronavirus public health emergency will end on June 30. Retrieved August 4, 2020, from https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/legal-notice-enabling-travel-to-and-from-22-countries-published.798852

- 11.Malta Independent. (2020). 20,000 passenger movements in first week since airport reopening—The Malta Independent. Retrieved August 4, 2020, from https://www.independent.com.mt/articles/2020-07-09/local-news/20-000-tourists-visit-Malta-in-first-week-since-airport-reopening-6736225000

- 12.Malta International Airport. (2020). Covid-19 Travel Advice - Malta International Airport. Retrieved August 4, 2020, from https://www.maltairport.com/covid19/

- 13.COVID-19 Public Health responders. (n.d.). Covid-19 Infographics. Retrieved August 17, 2020, from https://deputyprimeminister.gov.mt/en/health-promotion/covid-19/Pages/covid-19-infographics.aspx

- 14.Times of Malta. (2020c). Cash vouchers, cheaper fuel and lower tax on property sales to boost economy. Retrieved June 11, 2020, from https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/cash-vouchers-cheaper-fuel-and-lower-tax-on-property-sales-to-boost.797253

- 15.Borg, J. (2020b). No flight restrictions from July 15, public health emergency to be lifted. Retrieved June 14, 2020, from https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/public-health-emergency-to-be-lifted-new-destinations-including-italy.798498

- 16.Rackham, A. (2020). Malta: The island hoping to be 2020’s festival hotspot - BBC News. Retrieved August 4, 2020, from https://www.bbc.com/news/newsbeat-53395609

- 17.Caruana. Claire. (2020). Testing under way after new COVID-19 case attended ‘hotel takeover’ party. Retrieved August 4, 2020, from https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/new-covid-19-case-attended-hotel-takeover-party.806931

- 18.Caruana, C. (2020e). Six new COVID-19 cases after Hotel Takeover party. Retrieved August 4, 2020, from https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/hotel-takeover-six-new-covid-19-cases.807063

- 19.Times of Malta. (2020j). Sta Venera band march attendees urged to get tested for COVID-19. Retrieved August 4, 2020, from https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/sta-venera-festa-attendees-urged-to-get-tested-for-covid-19.807792

- 20.Bouayed J, Bohn T. Behavioural manipulation—Key to the successful global spread of the new Coronavirus SARS-Cov-2? Journal of Medical Virology. 2020 doi: 10.1002/JMV.26446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Furuse Y, Sando E, Tsuchiya N, Miyahara R, Yasuda I, Ko YK, et al. Clusters of Coronavirus disease in communities, Japan, January-April 2020. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2020 doi: 10.3201/eid2609.202272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murillo-Llorente MT, Perez-Bermejo M. Covid-19: Social irresponsibility of teenagers towards the second wave in Spain. Journal of Epidemiology. 2020 doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20200360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Atttard, C. (2020). “Jisplodu l-appuntamenti għas-swab tests; nappellaw għall-paċenzja”—Newsbook. Retrieved August 4, 2020, from https://newsbook.com.mt/jisplodu-l-appuntamenti-ghas-swab-tests-nappellaw-ghall-pacenzja/?fbclid=IwAR1fX38t2cQq2uUgIQRHYN4Jeg02EIQ0dRFeNdU-KQPFx7ajzYLLF8xlpRo

- 24.Calleja, C., & Caruana, C. (2020). Doctors deployed to test and trace COVID-19 patients to ease backlog. Retrieved August 17, 2020, from https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/doctors-deployed-to-test-and-trace-covid-19-patients-to-ease-backlog.811272

- 25.Caruana, C. (2020a). 20 per cent of August’s COVID-19 patients have no symptoms. Retrieved August 22, 2020, from https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/80-per-cent-of-augusts-covid-19-patients-have-no-symptoms.812883

- 26.Caruana, C. (2020b). 49 new coronavirus cases, as R factor rises above 2. Retrieved August 17, 2020, from https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/50-new-covid-19-cases-registered-overnight.810060

- 27.Caruana, C. (2020d). ‘If we keep on going the way we are, I will be worried’ – Charmaine Gauci. Retrieved August 5, 2020, from https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/if-we-keep-on-going-the-way-we-are-i-will-be-worried-charmaine-gauci.809667

- 28.Times of Malta. (2020l). Two new COVID-19 testing centres to be opened in Qormi and Burmarrad. Retrieved August 17, 2020, from https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/two-new-covid-19-testing-centres-to-be-opened-in-qormi-and-burmarrad.810315

- 29.Times of Malta. (2020g). Doctors threaten clinic closures, appointment disruptions over mass events. Retrieved August 4, 2020, from https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/doctors-threaten-clinic-closures-appointment-disruptions-over-mass.808650

- 30.Department of Information. (2020). Organised Public Mass Events Regulations, 2020 - Public Health Act. Retrieved from https://www.justiceservices.gov.mt/DownloadDocument.aspx?app=lp&itemid=30326&l=1

- 31.Carabott, S. (2020b). Ħamrun San Gejtanu march cancelled following COVID-19 spike. Retrieved August 17, 2020, from https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/hamrun-san-gejtanu-march-cancelled-following-covid-19-spike.808176

- 32.Martin, I. (2020b). International music festivals cancelled amid COVID-19 fears. Retrieved August 17, 2020, from https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/international-music-festivals-to-be-cancelled-amid-covid-19-fears.808776

- 33.Newsbeat. (2020). Malta festivals cancelled due to rise in Covid-19 cases - BBC News. Retrieved August 17, 2020, from https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-53642430

- 34.Times of Malta. (2020e). Church cancels all feasts for the year after COVID-19 spike. Retrieved August 17, 2020, from https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/church-cancels-all-feasts-after-covid-19-spike.809001

- 35.COVID-19 Public Health Response Team - Ministry for Health. (2020b). COVID-19 Data Management System.

- 36.Malta Association of Public Health Medicine. (2020). MAPHM Statement 7th August 2020 – MAPHM. Retrieved August 7, 2020, from https://maphm.org/2020/08/07/maphm-statement-7th-august-2020/

- 37.Times of Malta. (2020i). Public health experts blame “irresponsible” politicians for rise in virus cases. Retrieved August 7, 2020, from https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/public-health-experts-blame-irresponsible-politicians.810045

- 38.Caruana Claire. (2020). Gauci warns of “worrying” spill of COVID-19 from young to elderly. Retrieved August 22, 2020, from https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/watch-live-charmaine-gauci-delivers-update-on-covid-19-in-malta.811806

- 39.Times of Malta. (2020a). 72-year-old man is tenth COVID-19 victim. Retrieved August 22, 2020, from https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/72-year-old-man-is-tenth-covid-19-victim.813264

- 40.Times of Malta. (2020b). 86-year-old COVID-19 patient dies in hospital. Retrieved August 30, 2020, from https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/86-year-old-covid-19-patient-dies-in-hospital.814974

- 41.COVID-19 Public Health Response Team - Ministry for Health. (2020a). COVID-19 Dashboard - Malta - Infogram. Retrieved June 15, 2020, from https://infogram.com/1p1xpwwgj1w3v2imxjzwjvv152b63z02dvv?fbclid=IwAR0Ht0zJadMBkRKPS8pLbo3iVHhJzlVizQRcftZcdcJFQ74-SctWeNHMWHU

- 42.Diacono, T. (2020). Malta Ranked Third Best Worldwide For Its COVID-19 Testing Rate. Retrieved August 22, 2020, from https://lovinmalta.com/opinion/analysis/malta-ranked-third-best-worldwide-for-its-covid-19-testing-rate/

- 43.Carabott, S. (2020a). €50 fine for refusing to wear mask, as daily COVID-19 cases reach “new record.” Retrieved August 17, 2020, from https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/doctors-strike-continues-as-covid-19-cases-reach-new-record.810000?utm_source=tom&utm_campaign=newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_content=2020-08-07

- 44.Martin, I. (2020a). Ban on events of more than 100 inside, 300 outside amid virus surge. Retrieved August 17, 2020, from https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/watch-live-robert-abela-and-chris-fearne-hold-news-conference.810072

- 45.Times of Malta. (2020d). Charmaine Gauci briefings back on Friday. Retrieved August 17, 2020, from https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/charmaine-gauci-briefings-back-on-friday.809898

- 46.Ministry for Health. (2020). STQARRIJA MILL-UFFIĊĊJU TAD-DEPUTAT PRIM MINISTRU U MINISTERU GĦAS-SAĦĦA Introdotti iktar miżuri restrittivi. Retrieved August 19, 2020, from https://www.gov.mt/en/Government/DOI/PressReleases/Pages/2020/August/17/pr201562.aspx?fbclid=IwAR3LRrGpLPlx2ViIHAv7TaWDItkmu7Mb7F7ukZjQaMAYMjt_c9H0SUXdeeY

- 47.Times of Malta. (2020m). Watch: Bars, clubs closed and masks mandatory in new COVID-19 rules. Retrieved August 17, 2020, from https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/fearne-gauci-to-announce-new-covid-19-measures-at-11am.812367

- 48.Wise J. Covid-19: Risk of second wave is very real, say researchers. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.) 2020;369:m2294. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grech V, Grech P, Fabri S. A risk balancing act—Tourism competition using health leverage in the COVID-19 era. The International Journal of Risk & Safety in Medicine. 2020 doi: 10.3233/JRS-200042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Times of Malta. (2020h). Finland is latest country to impose Malta travel restrictions. Retrieved August 21, 2020, from https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/finland-is-latest-country-to-impose-malta-travel-restrictions.812901

- 51.Times of Malta. (2020n). Wave of cancellations hits tourism industry. Retrieved August 22, 2020, from https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/wave-of-cancellations-hits-tourism-industry.811938

- 52.Times of Malta. (2020k). Time to rise up to the challenge and start fixing the damage - doctors. Retrieved August 24, 2020, from https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/time-to-rise-up-to-the-challenge-and-start-fixing-the-damage-doctors.811977?fbclid=IwAR0HzveapRUMMs4ChzTTnM1c7v_ZnfkY48iIunV_B9VSZtfM-1xjTeBi-mA#.XzdwaQ4NAG0.facebook

- 53.World Health Organization. (2020a). Considerations for mass gatherings in the context of COVID-19: annex: considerations in adjusting public health and social measures in the context of COVID-19. Retrieved August 24, 2020, from https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/considerations-for-mass-gatherings-in-the-context-of-covid-19-annex-considerations-in-adjusting-public-health-and-social-measures-in-the-context-of-covid-19

- 54.World Health Organization. (2020b). How to use WHO risk assessment and mitigation checklist for mass gatherings in the context of COVID-19. Retrieved August 24, 2020, from https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/how-to-use-who-risk-assessment-and-mitigation-checklist-for-mass-gatherings-in-the-context-of-covid-19

- 55.Scudellari M. How the pandemic might play out in 2021 and beyond. Nature. 2020;584(7819):22–25. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-02278-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Al Saidi AMO, Nur FA, Al-Mandhari AS, El Rabbat M, Hafeez A, Abubakar A. Decisive leadership is a necessity in the COVID-19 response. The Lancet. 2020;396(10247):295–298. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31493-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lazarus JV, Binagwaho A, El-Mohandes AAE, Fielding JE, Larson HJ, Plasència A, et al. Keeping governments accountable: the COVID-19 Assessment Scorecard (COVID-SCORE) Nature Medicine. 2020;26(7):1005–1008. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0950-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nurchis MC, Pascucci D, Sapienza M, Villani L, D’Ambrosio F, Castrini F, et al. Impact of the burden of COVID-19 in Italy: Results of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) and productivity loss. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020 doi: 10.3390/ijerph17124233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]