Abstract

Many fetuses are found to have ultrasonic abnormalities in the late pregnancy. The association of fetal ultrasound abnormalities in late pregnancy with copy number variations (CNVs) is unclear. We attempted to explore the relationship between types of ultrasonically abnormal late pregnancy fetuses and CNVs. Fetuses (n = 713) with ultrasound-detected abnormalities in late pregnancy and normal karyotypes were analyzed. Of these, 237 showed fetal sonographic structural malformations and 476 showed fetal non-structural abnormalities. Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)-based chromosomal microarray (CMA) was performed on the Affymetrix CytoScan HD platform. Using the SNP array, abnormal CNVs were detected in 8.0% (57/713) of the cases, with pathogenic CNVs in 32 cases and variants of uncertain clinical significance (VUS) in 25 cases. The detection rate of abnormal CNVs in fetuses with sonographic structural malformations (12.7%, 30/237) was significantly higher (P = 0.001) than that in the fetuses with non-structural abnormalities (5.7%, 27/476). Overall, we observed that when fetal sonographic structural malformations or non-structural abnormalities occurred in the third trimester of pregnancy, the use of SNP analysis could improve the accuracy of prenatal diagnosis and reduce the rate of pregnancy termination.

Subject terms: Medical genetics, Molecular medicine

Introduction

Current techniques used for genetic testing of fetuses with ultrasound abnormalities include karyotype analysis and chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA). Karyotype analysis is presently the gold standard for prenatal diagnosis, but its resolution is low1. Thus, submicroscopic deletions or duplications (smaller than 3–5 Mb) may not be detected with traditional cytogenetic analysis unless additional techniques such as fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) are used. CMA is a high-resolution and genome-wide screening screening technology for the human genome. It is divided into two categories: Microarray based Comparative Genomic hybridization (aCGH) and single nucleotide polymorphism array (SNP), both of which can detect chromosomal microdeletions or microduplications. SNP array can detect not only CNVs, but also uniparental disomy and chimera. CMA has the advantage of high throughput and high resolution, and has been proven to be a powerful diagnostic tool in cases with developmental delays/mental retardation, autism syndrome, multiple birth defects, etc2–4. With the wide application of CMA as a prenatal diagnostic technique, clinical values of chromosomal microdeletions and microduplications are increasingly recognized.

Abnormal ultrasound findings in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy allow the detection of a unique group of late developmental manifestations, including major and minor fetal abnormalities or ultrasound soft markers, which do not exist in the first trimester of pregnancy5. Because of the lack of technical expertise in hospitals, obstetric ultrasound examination is only carried out in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy and some structural abnormalities are found only later with fetal development, thus resulting in a missed examination time for chorionic villus sampling and amniocentesis (Typically, chorionic villus sampling is performed at 10–12 weeks’ gestation, and amniocentesis is performed at 15–18 weeks’ gestation). Hence, at these later points, it becomes necessary to employ cordocentesis for cytogenetic analysis and to further clarify the cause of abnormality.

The relationships between fetal ultrasound abnormalities during pregnancy and chromosomal copy number variations (CNVs) have been extensively investigated3,6,7. In recent years, CMA has been recommended as the preferred diagnostic method for prenatal diagnosis of fetal ultrasound abnormalities8. However, there was little research assessment of the utility of CMA used in fetuses with abnormal ultrasound in late pregnancy. This study retrospectively analyzed the results of SNP analysis of 713 cases, from 2016 to 2019, and explored the relationship between types of ultrasonically abnormal late pregnancy fetuses and CNVs.

Methods

Patient data

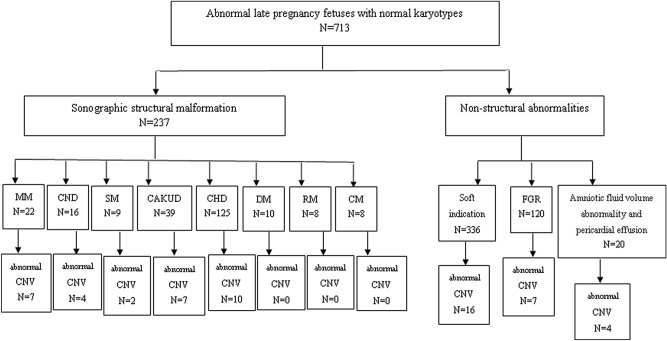

The data regarding pregnancies with abnormal ultrasound findings (n = 713) from November 2016 to July 2019 were collected at the Fujian Maternal and Child Health Hospital. The exclusion criteria were abnormal karyotype analysis results and normal fetal ultrasound findings. The inclusion criteria were fetal sonographic structural malformations and non-structural abnormalities. According to the anatomical system affected, sonographic structural malformations were divided into: (1) central nervous system; (2) cardiovascular system; (3) urogenital system; (4) skeletal system; (5) respiratory system; (6) digestive system; and (7) craniofacial region malformations. Non-structural abnormalities were divided into: (1) ultrasound soft markers (including an echogenic bowel, absence of nasal bone, lateral ventricle widening, intracardiac echogenic focus, and tricuspid regurgitation); (2) fetal growth restriction (FGR); and (3) amniotic fluid volume abnormality and pericardial effusion. Indications for late cordocentesis included fetal sonographic structural malformations (n = 237) and fetal non-structural abnormalities (n = 476) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Ultrasonically abnormal late pregnancy fetuses with normal karyotypes were selected from November 2016 to July 2019. MM multiple malformations, CND central nervous disease, SM skeleton malformation, CAKUD congenital heart disease, DM digestive malformation, RM Respiratory malformation, CM craniofacial malformation, FGR fetal growth restrictions, CNV copy number variation.

Karyotype analysis

According to the routine methods established in our laboratory, umbilical cord blood was routinely cultured for 72 h, and then the chromosomes were harvested, fixed and prepared. Cultured cells were analyzed by karyotype analysis using Giemsa banding at a resolution of 450–550 bands.

Single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array

Ultrasound-guided cordocentesis was used to extract umbilical cord blood for prenatal SNP-array testing. To avoid maternal cell contamination during cordocentesis, short-tandem repeats analysis was conducted before testing fetal samples. Genomic DNA extraction from fetal umbilical cord blood cells was performed using a QIAamp DNA blood mini kit (Qiagen, Germany). The concentration and purity of genomic DNA were measured using a NanoDrop One Microvolume UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). DNA digestion, amplification, purification, fragmentation, labeling, hybridization, washing, staining, scanning, and other steps were carried out according to the manual for an Affymetrix Genome CytoScan 750K gene chip. The reporting thresholds for CNVs were 400 kb deleted and 400 kb duplicated. Data analysis was carried out using the Chromosome Analysis Suite software 3.3 (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Based on the nature of CNVs detected, CNVs were classified as pathogenic, variants of uncertain clinical significance (VUS), and benign, according to the American College of Medical Genetics guidelines9.

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics 20 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for statistical analysis. The CNV rates were compared between fetuses with sonographic structural malformations and those with non-structural abnormalities. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics declaration

The protocol of this study was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee at the Fujian Provincial Maternal and Child Health Hospital (2014-042). All parents were informed that the data might be used for future research studies and signed written informed consent was obtained. All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Results

Detection rates of abnormal CNVs

The included women were pregnant for 28 to 37 weeks, with an average of 29.0 ± 3.4 weeks. The ages of the participants ranged from 18 to 46 years, with an average of 32.1 ± 6.1 years. Among the 713 fetuses with ultrasound-detected abnormalities and normal karyotypes, CMA detected abnormal CNVs in 8.0% (57/713) of the cases, including pathogenic CNVs in 32 cases, VUS in 25 cases, and seven cases with benign CNVs. The detection rate of abnormal CNVs in fetuses with sonographic structural malformations (12.7%, 30/237) was significantly higher (P = 0.001) than in fetuses with non-structural abnormalities (5.7%, 27/476) (Table 1). In the case of sonographic structural malformations, the detection rates of abnormal CNVs were 31.8%, 25%, 22.2%, 17.9%, and 8.0% in fetuses with multiple malformations (7/22), central nervous system malformations (4/16), skeletal malformations (2/9), congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (7/39), and congenital heart malformations (10/125), respectively. Among fetal non-structural abnormalities, the greatest number was represented by abnormal soft indications (70.6%, 336/476), followed by FGR (25.2%, 120/476) and amniotic fluid volume abnormality and pericardial effusion (4.2%, 20/476). The detection rates of abnormal CNVs were 20%, 5.8%, and 4.8% among the fetuses with amniotic fluid volume abnormality and pericardial effusion (4/20), FGR (7/120), and abnormal soft indications (16/336), respectively (Table 2, Fig. 1).

Table 1.

The detection rate of abnormal CNVs in 713 fetuses.

| Indication for prenatal diagnosis | Number | Number of abnormal CNV | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sonographic structural malformation | 237 | 30 | 12.7 |

| Non-structural abnormalities | 476 | 27 | 5.7 |

CNV copy number variation.

Table 2.

Phenotypic characteristics of 713 fetuses.

| Anomaly on ultrasonography | Number (% total cohort) | Number of CNV anomaly (% total anomaly) | Number of pathogenic CNV | Number of VUS CNV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sonographic structural malformation | 237 (33.2) | 30 (12.7) | 21 | 9 |

| Multiple malformations | 22 (3.1) | 7 (31.8) | 5 | 2 |

| Central nervous disease | 16 (2.2) | 4 (25.0) | 2 | 2 |

| Skeletal malformation | 9 (1.3) | 2 (22.2) | 2 | 0 |

| Congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract | 39 (5.5) | 7 (17.9) | 4 | 3 |

| Congenital heart disease | 125 (17.5) | 10 (8.0) | 8 | 2 |

| Digestive malformation | 10 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Respiratory malformation | 8 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Craniofacial malformation | 8 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Non-structural abnormalities | 476 (66.8) | 27 (5.7) | 11 | 16 |

| Amniotic fluid volume abnormality and pericardial effusion | 20 (2.8) | 4 (20.0) | 1 | 3 |

| Fetal growth restriction | 120 (16.8) | 7 (5.8) | 5 | 2 |

| Abnormal soft indication | 336 (47.1) | 16 (4.8) | 5 | 11 |

CNV copy number variation, VUS variants of uncertain clinical significance.

Pathogenic CNVs detected in fetuses with ultrasound abnormalities and normal karyotypes using an SNP array

Among the 32 cases with pathogenic CNVs, 24 were related to known chromosomal disorders, namely, 22q11 deletion syndrome (n = 5), 22q11.2 duplication syndrome (n = 3), 17q12 deletion syndrome (n = 3), cat eye (n = 1), 16p11.2 deletion syndrome (n = 4), Prader–Willi syndrome (n = 1), Miller–Dieker syndrome (n = 1), Wolf–Hirschhorn syndrome (n = 1), Sotos syndrome (n = 1), 7q11.23 duplication syndrome (n = 2), and 1q21.1 duplication syndrome (n = 2). Additionally, the pathogenic CNVs were associated with a loss at 17p12, 1p36.33p36.23, and 22q13.33 and a gain at 15q13.3, 1q21.1q21.2, 3q29, Xq28, and 10q11.22q11.23 (Table 3).

Table 3.

The pathogenic copy number variation in ultrasonically abnormal fetuses.

| Case | CC week | SNP array | Size (Mb) | Indication | Interpretation | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 28+6 | Chr22: 18,648,855–21,800,471 | 3.1 | CHD, thymic dysplasia | Pathogenic: loss 22q11.2 (22q11deletion syndrome) | Termination of pregnancy |

| 2 | 29 | Chr22: 20,730,143–21,800,471 | 1.0 | Multiple cysts of the left choroid plexus, renal cysts of the left, and varus | Pathogenic: loss 22q11.2 (22q11deletion syndrome) | Termination of pregnancy |

| 3 | 33+5 | Chr22: 18,916,842–21,800,471 | 2.9 | VSD; Mirror-image right aortic arch | Pathogenic: loss 22q11.2 (22q11deletion syndrome) | Termination of pregnancy |

| 4 | 32+3 | Chr22: 18,648,855–21,800,471 | 3.1 | VSD | Pathogenic: loss 22q11.2 (22q11deletion syndrome) | Termination of pregnancy |

| 5 | 28+1 | Chr22: 18,648,855–21,800,471 | 3.1 | VSD; right aortic arch | Pathogenic: loss 22q11.2 (22q11deletion syndrome) | Termination of pregnancy |

| 6 | 28+5 | Chr22: 49,683,904–51,197,766 | 3.1 | Echogenic bowel | Pathogenic: loss 22q13.33 (22q13 deletion syndrome) | Termination of pregnancy |

| 7 | 33+1 | Chr22: 18,649,189–21,800,471 | 3.1 | CHD: Oval valve bulging tumor | Pathogenic: gain 22q11.2 (22q11.2 duplication syndrome), de novo | Termination of pregnancy |

| 8 | 30 | Chr22: 18,648,855–21,459,713 | 2.8 | FGR | Pathogenic: gain 22q11.21 (22q11.2 duplication syndrome), inherited from mother |

Normal delivery Good growth and development |

| 9 | 28+3 | Chr22: 18,648,855–21,800,471 | 3.1 | FGR | Pathogenic: gain 22q11.21 (22q11.2 duplication syndrome), inherited from father |

Cesarean section Good growth and development |

| 10 | 28+3 | Chr22: 18,888,899–18,649,190 | 1.7 | VSD, persistent left superior vena cava | Pathogenic: gain 22q11.1q11.21 (cat eye syndrome) | Termination of pregnancy |

| 11 | 28+4 | Chr17: 34,822,465–36,404, 555 | 1.58 | Double kidney echo enhancement | Pathogenic: loss 17q12 (17q12 deletion syndrome) | Termination of pregnancy |

| 12 | 28+ | Chr17: 34,822,465–36, 243,365 | 1.4 | Double kidney echo enhancement | Pathogenic: loss 17q12 (17q12 deletion syndrome) | Termination of pregnancy |

| 13 | 29+4 | Chr17: 34,822,465–36,307, 773 | 1.48 | Double kidney echo enhancement | Pathogenic: loss 17q12 (17q12 deletion syndrome) | Termination of pregnancy |

| 14 | 29+5 | Chr16: 28,810,324–29,032,280 | 0.22 | Lateral ventricle widening, echogenic bowel, Left ventricular hyperecho | Pathogenic: loss 16p11.2 (16p11.2 deletion syndrome), de novo | Termination of pregnancy |

| 15 | 31 | Chr16: 29,591,326–30,176,508 | 0.57 | Hydrocephalus | Pathogenic: loss 16p11.2 (16p11.2 deletion syndrome), de novo | Termination of pregnancy |

| 16 | 28+4 | Chr16: 29,580,020–30,190,029 | 0.60 | Spinal dysplasia | Pathogenic: loss 16p11.2 (16p11.2 deletion syndrome), de novo | Termination of pregnancy |

| 17 | 28 | Chr16: 29,567,296–30,190,029 | 0.6 | Lateral ventricle widening | Pathogenic: loss 16p11.2 (16p11.2 deletion syndrome), de novo | Termination of pregnancy |

| 18 | 33+1 | Chr15: 32,003,537–32,444,043 | 0.43 | VSD, Aortic ride across, pulmonary stenosis, | Pathogenic: gain 15q13.3, the triple dose effect score was 1, penetrance of 5–10% in ClinGen database |

Normal delivery VSD |

| 19 | 37 | Chr15: 31,999,631–32,444,043 | 0.43 | Severe hydrocephalus | Pathogenic: gain 15q13.3, the triple dose effect score was 1, penetrance of 5–10% in ClinGen database | Termination of pregnancy |

| 20 | 29+6 | Chr15: 32,011,458–32,914,239 | 0.88 | Half vertebral body | Pathogenic: gain 15q13.3, The triple dose effect score was 1, penetrance of 5–10% in ClinGen database | Termination of pregnancy |

| 21 | 34 | Chr1: 145,958,361–147,830,830 | 1.8 | Lateral ventricle widening | Pathogenic: gain 1q21.1q21.2 (1q21.1 duplication syndrome) | Termination of pregnancy |

| 22 | 29+6 | Chr1: 145,995,176–147,398,268 | 1.4 | Pulmonary stenosis; hypoplastic right heart; Tricuspid stenosis with incomplete closure | Pathogenic: gain 1q21.1q21.2 (1q21.1 duplication syndrome) | Termination of pregnancy |

| 23 | 28+4 | Chr7: 72,701,098–74,069,645 | 1.3 | VSD, unilateral renal agenesis | Pathogenic: gain 7q11.23 (7q11.23 duplication syndrome) | Termination of pregnancy |

| 24 | 32+6 | Chr7: 72,723,370–74,143,240 | 1.42 | FGR | Pathogenic: gain 7q11.23 (7q11.23 duplication syndrome) | Termination of pregnancy |

| 25 | 29+2 | Chr17: 525–5,204,373 | 5.2 | Bilateral ventricle widening,Strephenopodia, cerebellum entricular dysplasia | Pathogenic: loss 17p13.3p13.2, (Miller-Dieker syndrome) | Termination of pregnancy |

| 26 | 30+4 | Chr17: 14,083,054–15,482,833 | 1.4 | Left renal dysplasia | Pathogenic: loss 17p12, Hereditary stress susceptibility peripheral neuropathy, Inherited from mother | Termination of pregnancy |

| 27 | 34+1 | Chr4: 68,345–6,608,624 | 6.5 | FGR, pulmonary stenosis | Pathogenic: loss 4p16.3p16.1 (Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome) | Termination of pregnancy |

| 28 | 28+4 | Chr3: 195,743,957–197,386,180 | 1.6 | VSD | Pathogenic: gain 3q29 (3q29 duplication syndrome) | Termination of pregnancy |

| 29 | 31+6 | Chr5: 175,416,095–177,482,506 | 2.0 | Polyhydramnios | Pathogenic: loss 5q35.2q35.3 (Sotos syndrome) | Termination of pregnancy |

| 30 | 29 | ChrX; Chr1: 152,446,333–153,581,657 | 1.1 | Bilateral ventricular walls are rough and echo is enhanced | Pathogenic: gain Xq28, 1q44, loss 1p36.33p36.23 (1p36 deletion syndrome) | Termination of pregnancy |

| 849,466–592,172 | 7.7 | |||||

| 246,015,892–249,224,684 | 3.2 | |||||

| 31 | 33+1 | Chr10: 46,252,072–51,903,756 | 5.6 | FGR | Pathogenic: gain 10q11.22q11.23, reports in the DGV database, de novo | Termination of pregnancy |

| 32 | 32+6 | Chr15: 35,077,111–54,347,324 | 19.2 | FGR | Pathogenic: uniparental disomy, Inherited from mother (Prader–Willi syndrome) | Termination of pregnancy |

CC cordocentesis, CHD congenital heart disease, VSD ventricular septal defect, FGR fetal growth restriction.

VUS detected in fetuses with ultrasound abnormalities and normal karyotypes using an SNP array

The SNP array detected that 25 fetuses carried VUS, which were associated with microdeletions, ranging from 0.22 to 5.5 Mb, and microduplications, ranging from 0.20 to 2.9 Mb (Table 4). Among the 25 cases with VUS, three fetuses were found to have 16p13.11 duplications, and three fetuses were found to have 15q11.2 deletions. The detected VUS were also associated with a gain at 17q21.31, 13q14.3, 10q24.31q24.32, 8p23.2, 4q24, 2q36.1q36.2, and 2q22.2 and a loss at 16p13.11, 1q21.1, 2q11.1.1q11.2, 3p26.3, 3p22.1, 3q28, 5p15.33p15.31, 10q11.21q11.22, 14q21.2q21.3, and Xp21.1. In addition, two fetuses lacked heterozygosity (Table 4).

Table 4.

The variants of uncertain clinical significance in ultrasonically abnormal fetuses.

| Case | CC week | SNP array | Size (Mb) | Indication | Interpretation | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 28+4 | Chr16: 14,897,401–16,534,031 | 1.6 | VSD |

VUS Loss 16p13.11, Hereditary stress susceptibility peripheral neuropathy, The carrier frequency in the population is less than 1% |

Eutocia Good growth and development |

| 2 | 28+3 | Chr16: 15,325,072–16,272,403 | 0.92 | Bilateral dysplasia with hydronephrosis |

VUS Gain 16p13.11, The carrier frequency in the population is less than 1%, penetrance of 5–10% |

Termination of pregnancy |

| 3 | 32+2 | Chr16: 15,171,146–16,309,046 | 1.1 | Echogenic bowel |

VUS: Gain 16p13.11, The carrier frequency in the population is less than 1%, penetrance of 5–10%, Inherited from mother |

Eutocia Good growth and development |

| 4 | 31+1 | Chr16: 15,510,512–16,309,046 | 0.78 | Tricuspid regurgitation |

VUS Gain 16p13.11, The carrier frequency in the population is less than 1%, penetrance of 5–10% |

Eutocia Good growth and development |

| 5 | 33+2 | Chr15: 22,770,421–23,277,435 | 0.50 | VSD,Dandy-Walker malformation |

VUS Loss 15q11.2, inherited from father |

Termination of pregnancy |

| 6 | 28 | Chr15: 22,770,421–23,286,423 | 0.5 | Echogenic bowel |

VUS Loss 15q11.2, inherited from father |

Cesarean growth retardation |

| 7 | 29+1 | Chr15: 22,770,421–23,082,237 | 0.30 | Subcutaneous cyst at the back of the neck |

VUS Loss 15q11.2, inherited from father |

Cesarean growth retardation |

| 8 | 32+4 | Chr17: 41,774,473–42,491,805 | 0.70 | FGR |

VUS Gain 17q21.31, no report in the DGV |

Cesarean growth retardation |

| 9 | 28+1 | Chr13: 52,649,105–53,172,866 | 0.53 | Hydronephrosis, strephenopodia, tricuspid regurgitation |

VUS Gain 13q14.3, no report in the DGV, de novo |

Termination of pregnancy |

| 10 | 33+2 | Chr10: 102,972,457–103,179,063 | 0.20 | Posterior fossa widened |

VUS Gain 10q24.31q24.32, no report in the DGV |

Eutocia Good growth and development |

| 11 | 29 | Chr8: 3,703,883–5,940,433 | 2.2 | Bilateral choroid plexus cysts |

VUS Gain 8p23.2, no report in the DGV database, de novo |

Eutocia Good growth and development |

| 12 | 29+3 | Chr4: 106,284,925–107,545,257 | 1.2 | VSD |

VUS Gain 4q24, no report in the DGV, de novo |

Loss to follow-up |

| 13 | 35+2 | Chr2: 224,459,152–225,330,583 | 0.85 | Posterior fossa widened |

VUS Gain 2q36.1q36.2, no report in the DGV, de novo |

Cesarean Good growth and development |

| 14 | 28+1 | Chr2: 143,043,284–143,866,399 | 0.80 | Pericardial effusion |

VUS Gain 2q22.2, no report in the DGV, de novo |

Eutocia Good growth and development |

| 15 | 34 | Chr1; Chr9: 145,375,770–145,770,627, 4,623,660–5,501,699 | 0.68, 0.86 | Lateral ventricle widening |

VUS Loss 1q21.1, gain 9p24.1, no report in the DGV, de novo |

Eutocia Good growth and development |

| 16 | 32 | Chr2: 96,679,225–97,669,032 | 0.97 | Hydronephrosis |

VUS Loss 2q11.1.1q11.2, No report in the DGV database, de novo |

Eutocia Good growth and development |

| 17 | 33+3 | Chr3: 1,855,754–2,663,625 | 0.79 | Bilateral ventricle widening |

VOUS Loss 3p26.3, no report in the DGV, de novo |

Cesarean Good growth and development |

| 18 | 29+1 | Chr3: 42,875,130–43,309,436 | 0.42 | Lateral ventricle widening |

VUS Loss 3p22.1, no report in the DGV, de novo |

Loss to follow-up |

| 19 | 32+1 | Chr3, Chr15: 188,788,120–191,331,505,23,620,191–24,978,547 | 2.5 | Unilateral renal agenesis |

VUS Loss 3q28, gain 15q11.2, no report in the DGV, de novo |

Termination of pregnancy |

| 20 | 29+6 | Chr5: 4,482,234–6,636,035 | 2.1 | Pericardial effusion |

VUS Loss 5p15.33p15.31, no report in the DGV, de novo |

Termination of pregnancy |

| 21 | 29+2 | Chr10: 42,433,738–48,006,310 | 5.5 | Echogenic bowel |

VUS Loss 10q11.21q11.22, The deletion fragment contains RET gene, associated with congenital megacolon, de novo |

Termination of pregnancy |

| 22 | 32+4 | Chr14: 46,782,405–49,288,860 | 2.5 | Hydrocephalus |

VUS Loss 14q21.2q21.3, no report in the DGV, de novo |

Eutocia Good growth and development |

| 23 | 32+6 | ChrX: 32,670,116–32,891,702 | 0.22 | Pericardial effusion |

VUS Loss Xp21.1, no report in the DGV, de novo |

Loss to follow-up |

| 24 | 28+6 | Chr3, Chr5, Chr6, Chr12, Chr17, Chr21: 163,256,369–197,791,601, 41,029,137–46,313,469, 143,341,406–161,527,784, 56,011,100–77,134,151, 39,639,602–45,479,706, 28,124,165–42,352,287 | 99.1 | Lateral ventricle widening |

VUS Lack of heterozygosity 3q26.1q29, 5p13.1p11, 6q24.2q26, 12q13.2q21.2, 17q21.2q21.32, 21q21.3q22.2 |

Termination of pregnancy |

| 25 | 32+3 | Chr4: 133,718,289–154,569,367 | 20.8 | FGR |

VUS Lack of heterozygosity 4q28.3q31.3 |

Eutocia Good growth and development |

CC cordocentesis, VSD ventricular septal defect, FGR fetal growth restriction, VUS variants of uncertain clinical significance.

Benign CNVs detected in fetuses with ultrasound abnormalities and normal karyotypes using SNP array

The seven benign CNVs in fetuses were inherited from their healthy parents (Table 5). According to the Database of Genomic Variants (DGV), these genes have not been reported previously.

Table 5.

The variants of benign in ultrasonically abnormal fetuses.

| Case | CC week | SNP array | Size (Mb) | Indication | Interpretation | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 28+2 | Chr5: 76,983,283–77,512,158 | 0.5 | VSD |

B Gain 5q14.1, no report in the DGV, inherited from mother |

Eutocia Good growth and development |

| 2 | 30 | Chr3 : 33,805,560–35,318,562 | 1.5 | Pericardial effusion |

B Loss 3p22.1, no report in the DGV, inherited from mother |

Cesarean Good growth and development |

| 3 | 31+6 | Chr5: 154,435,034–156,727,811 | 2.9 | Echogenic bowel |

B Gain 5q33.2q33.3, no report in the DGV, inherited from father |

Eutocia Good growth and development |

| 4 | 28+6 | Chr7: 139,340,641–139,769,640 | 0.4 | Right subclavian artery vagus |

B Gain7q34, no report in the DGV, inherited from mother |

Eutocia Good growth and development |

| 5 | 28+6 | Chr8: 126,044,027–126,414,021 | 0.4 | Persistent left superior vena cava, single umbilical artery |

B Gain8q24.13, no report in the DGV, inherited from mother |

Eutocia Good growth and development |

| 6 | 29 | Chr9: 122,199,202–123,921,999 | 1.7 | Left ventricular echo, echogenic bowel |

B Gain9q33.1q33.2, no report in the DGV, inherited from father |

Eutocia Good growth and development |

| 7 | 29 | Chr9: 19,620,590–21,572,153 | 1.9 | Left ventricular echo |

B Gain18q11.2, no report in the DGV, inherited from father |

Eutocia Good growth and development |

CC cordocentesis, VSD ventricular septal defect, B benign.

Genealogical analysis and pregnancy outcomes

The parents of nine fetuses with pathogenic CNVs were tested, and it was found that five CNVs were de nova and four were inherited. Among the 25 cases of fetuses with VUS, the parents refused genetic testing in seven cases. In the other 18 cases, the variants were confirmed to be inherited. Some pregnant women with fetuses with pathogenic CNV (n = 29) and VUS (n = 7) chose to terminate the pregnancies. However, 15 cases with VUS CNVs women chose to continue the pregnancy and showed good growth and development on postnatal examination. In the seven cases in which fetuses were found to have inherited a benign CNV from one of the normal parents, the pregnancies were continued and had a favorable outcome.

Discussion

We retrospectively analyzed the SNP analysis data of 713 cases, and explored the correlation between phenotype characteristics of the fetuses and pathogenic CNVs. All 713 fetuses with abnormal ultrasound findings and normal karyotypes were investigated by CMA. We detected abnormal CNVs in 8.0% (57/713) of the cases, including pathogenic CNVs in 32 cases (4.5%, 32/713) and VUS in 25 cases (3.5%, 25/713). This rate of detection of abnormal CNVs was somewhat higher than that reported in previous studies10–12. We suggest that CMA should be considered for genetic analysis in cases with abnormal ultrasound findings in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy.

With the growth of the fetus, more fetal ultrasound abnormalities (structural and non-structural) are found during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy. In our study, the detection rate of abnormal CNVs in fetuses with sonographic structural malformations (12.7%, 30/237) was significantly higher (P = 0.001) than in fetuses with non-structural abnormalities (5.7%, 27/476). Among the fetuses with sonographic structural malformations, those with multiple malformations showed the greatest rate of CNVs (31.8%, 7/22), followed by fetuses with central nervous system malformations (25%, 4/16), congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (18.0%, 7/39), and congenital heart malformations (8%, 10/125). These findings are slightly different from those of a previous study13, in which cardiovascular, central nervous, gastrointestinal, and musculoskeletal system malformations were mostly associated with pathogenic CNVs.

At present, the consensus regarding the application of CMA in prenatal diagnosis does not include cases with non-structural abnormalities. There are few studies reporting the relationships between sonographic non-structural abnormalities and chromosomal duplications/deletions. In our study, among the fetuses with non-structural abnormalities, those with amniotic fluid volume abnormality and pericardial effusion showed the greatest rate of CNVs (20%, 4/20), followed by fetuses with FGR (5.8, 7/120) and abnormal soft indications (4.8%, 16/336). Compared with that reported in another study14, the CNV detection rate in the fetuses with sonographic non-structural abnormalities was slightly higher in this study, likely due to differences in the selected cohorts of fetuses with ultrasound anomalies in late pregnancy.

In most cases, there are direct causal relationships between pathogenic CNVs and fetal phenotypes. However, the use of genotype–phenotype associations is not always reliable in prenatal diagnosis. Our findings revealed 32 cases of pathogenic CNVs. The most common was 22q11 deletion syndrome15, which is associated with congenital heart disease. We also found three fetuses with 17q12 deletion syndrome16, which is associated with congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract. The only ultrasonographic manifestations in these fetuses were double kidney echo enhancements. A CNV on human chromosome 16p11.2 is associated with autism spectrum disorders17,18. We detected this known 16p11.2 deletion syndrome in four fetuses, with different ultrasonographic manifestations. The ultrasonographic manifestations in three of the fetuses were hydrocephalus, spinal dysplasia, and lateral ventricle widening. The fourth fetus presented with a widened lateral ventricle, echogenic bowel, and echogenic foci within the left ventricle. Owing to the limitations of ultrasound, fetal phenotypes are often incomplete, which may complicate prenatal counseling19. Therefore, the application of genomic detection techniques is important in fetuses with ultrasound abnormalities.

We detected 25 fetuses with VUS, of which three fetuses had 16p13.11 duplications and one had a 16p13.11 deletion. According to the literature20–23, gain and loss at 16p13.11 have been associated with autism, schizophrenia, and epilepsy. The carrier frequencies of duplications and deletions at the 16p13.11 locus are less than 1% in the general population, but the penetrance is 5–10%24; therefore, we defined the CNVs at 16p13.11 as VUS. We also detected 15q11.2 deletions in three fetuses. The ultrasonographic manifestations in these fetuses included ventricular septal defect (VSD), a Dandy–Walker malformation, an echogenic bowel, and a subcutaneous cyst at the back of the neck. Genetic analysis showed that these deletions were inherited from one of the normal parents. However, there are some reports of 15q11.2 deletions causing neurodevelopmental alterations25,26. Thus, we also defined the 15q11.2 deletions as VUS. Another 15 mutations were defined as VUS because these CNVs have not been reported in the DGV and were identified as de novo variants by pedigree analysis. Two cases were identified to lack heterozygosity. The parents of these two cases refused to undergo a pedigree test, and therefore, we defined the lack of heterozygosity as VUS. Seven fetuses were found to have inherited their CNVs from their normal parents. As there are no reports of these CNVs in the DGV, they were defined as benign CNVs. At present, the greatest difficulty in the use of SNP-array results in prenatal diagnosis lies in the correct interpretation of VUS. Literature reports show that the rates of VUS detection are 1.4–12.3%11,27,28; hence, the rate found in our study (3.5%) was consistent with previous findings.

Following the application of an SNP array to rule out genomic abnormalities, pregnant women generally choose to deliver their babies, thus avoiding unnecessary termination of pregnancy. This outcome emphasizes the importance of CMA in genetic counseling. In our study, 29 cases of fetal sonographic structural malformations with pathogenic CNVs resulted in pregnancy termination; however, in three cases, the parents chose to deliver and neonates had good outcomes no other abnormalities were found except one with VSD. Of the 25 cases of fetuses with VUS, in 15 cases, the parents chose to deliver, and the babies showed good growth and development after birth. We also found that seven cases associated with benign CNVs continued their pregnancies and had a favorable outcome. According to our experience, if the observations by ultrasound associated with chromosomal anomalies and other fatal malformation are excluded, the pregnant women may have increased confidence in continuing pregnancy, especially CNVs were inherited.

There were some limitations to our study. First, we only used the SNP array to detect CNVs in fetuses with ultrasound-detected abnormalities and normal karyotyping analysis results. Thus, we cannot rule out single-gene mutations. In recent years, next-generation sequencing has been used as a new technique for genetic testing to detect single-gene mutations and CNVs. This technology may provide a more comprehensive prenatal genetic diagnosis for fetuses with ultrasound-detected abnormalities and a better assessment of the fetal prognosis. Second, the origins of some VUS were not traced, and thus, the sample size should be increased to further study these VUS. In addition, the numbers of cases in the subsystems of some ultrasound abnormalities were insufficient, and therefore, it was impossible to group those cases at a deeper level. In the future, more cases need to be analyzed, or multicenter collaborations are required, to improve the statistical reliability of the findings.

Conclusion

CMA can be used as an effective method for genetic diagnosis of ultrasonically abnormal late pregnancy fetuses. The detection rate of CMA was different for different types of ultrasonically abnormal late pregnancy fetuses. CMA can improve the detection rate of chromosomal abnormalities that cannot be detected by karyotype analysis. In genetic counselling, CMA should be utilized based on the type of ultrasonic abnormality observed.

Acknowledgements

We thank all participants included in this study. This work was supported by the Key Special Projects of the Fujian Provincial Department of Science and Technology (2013YZ0002-1); the Key Clinical Specialty Discipline Construction Program of Fujian (20121589); and the Fujian Provincial Natural Science Foundation (2017J01238).

Author contributions

L.P.X. and Y. Lin developed the study concept. M.Y.C. designed the study. H.L.H. performed CMA analysis. X.Q.W and Y. Li performed karyotyping. N.L. performed data analysis and interpretation. X.R.X. and L.J.S. performed statistical analysis. M.Y.C. and H.L.H. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

All data generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available upon request by contact the corresponding author.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Meiying Cai and Na Lin.

Contributor Information

Liangpu Xu, Email: xiliangpu@fjmu.edu.cn.

Hailong Huang, Email: huanghailong@fjmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Yi J-L, Zhang W, Meng D-H, Ren L-J, Wei Y-L. Epidemiology of fetal cerebral ventriculomegaly and evaluation of chromosomal microarray analysis versus karyotyping for prenatal diagnosis in a Chinese hospital. J. Int. Med. Res. 2019;47:030006051985340. doi: 10.1177/0300060519853405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu J, Qian Y, Sun Y, Yu J, Dong M. Application of single nucleotide polymorphism microarray in clinical diagnosis of intellectual disability or retardation. J. Zhejiang Univ. Med. Sci. 2019;48:420–428. doi: 10.3785/j.issn.1008-9292.2019.08.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fangbo Q, Ye S. Application of whole-genome chromosomal microarray analysis in genetic diagnosis of spontaneous miscarriages and stillbirths. Acta Univ. Med. Nanjing (Nat. Sci.) 2018;11:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jang W, et al. Chromosomal microarray analysis as a first-tier clinical diagnostic test in patients with developmental delay/intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorders, and multiple congenital anomalies: A prospective multicenter study in Korea. Ann. Lab. Med. 2019;39:299–310. doi: 10.3343/alm.2019.39.3.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanvisut R, et al. Cordocentesis-associated fetal loss and risk factors: Experience of 6650 cases from a single center. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/uog.21980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Srebniak MI, et al. Prenatal SNP array testing in 1000 fetuses with ultrasound anomalies: Causative, unexpected and susceptibility CNVs. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2016;24:645–651. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2015.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lovrecic L, et al. Clinical utility of array comparative genomic hybridisation in prenatal setting. BMC Med. Genet. 2016;17:81. doi: 10.1186/s12881-016-0345-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Obstetricians ACO, Genetics GCO. Committee opinion no. 581: The use of chromosomal microarray analysis in prenatal diagnosis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;122:1374–1377. doi: 10.1097/00006250-201312000-00042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanemaaijer NM, et al. Practical guidelines for interpreting copy number gains detected by high-resolution array in routine diagnostics. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2012;20:161–165. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levy B, Wapner R. Prenatal diagnosis by chromosomal microarray analysis. Fertil. Steril. 2018;109:201–212. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hillman SC, et al. Use of prenatal chromosomal microarray: Prospective cohort study and systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;41:610–620. doi: 10.1002/uog.12464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robson SC, et al. Evaluation of array comparative genomic Hybridisation in prenatal diagnosis of fetal anomalies: A multicentre cohort study with cost analysis and assessment of patient, health professional and commissioner preferences for array comparative genomic hybridis. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2017;122:1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xia Y, et al. Clinical application of chromosomal microarray analysis for the prenatal diagnosis of chromosomal abnormalities and copy number variations in fetuses with congenital heart disease. Prenat. Diagn. 2018;38:406–413. doi: 10.1002/pd.5249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Srebniak MI, et al. Types of array findings detectable in cytogenetic diagnosis: A proposal for a generic classification. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2014;22:856–858. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2013.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Celep G, Oğur G, Günal N, Baysal K. DiGeorge syndrome (Chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome): A historical perspective with review of 66 patients. J. Surg. Med. 2019 doi: 10.28982/josam.513859. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jing X-Y, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of 17q12 deletion syndrome: A retrospective case series. J. Obstetr. Gynaecol. J. Inst. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2019 doi: 10.1080/01443615.2018.1519693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stein JL. Copy number variation and brain structure: Lessons learned from chromosome 16p11.2. Genome Med. 2015;7(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s13073-015-0140-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Redaelli S, et al. Refining the phenotype of recurrent rearrangements of chromosome 16. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20(5):1095. doi: 10.3390/ijms20051095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wapner RJ, Driscoll DA, Simpson JL. Integration of microarray technology into prenatal diagnosis: Counselling issues generated during the NICHD clinical trial. Prenat. Diagn. 2012;32:396–400. doi: 10.1002/pd.3863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Torres F, Barbosa M, Maciel P. Recurrent copy number variations as risk factors for neurodevelopmental disorders: Critical overview and analysis of clinical implications. J. Med. Genet. 2015;394:949–956. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2015-103366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bravo C, Gamez F, Perez R, Aguaron A, De Leon-Luis J. Prenatal diagnosis of Potocki-Lupski syndrome in a fetus with hypoplastic left heart and aberrant right subclavian artery. J. Perinatol. 2013;33:394–396. doi: 10.1038/jp.2012.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jefferies JL, et al. Cardiovascular findings in duplication 17p11.2 syndrome. Genet. Med. 2012;14:90–94. doi: 10.1038/gim.0b013e3182329723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tropeano M, et al. Male-biased autosomal effect of 16p13.11 copy number variation in neurodevelopmental disorders. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e61365. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maria T, et al. Male-biased autosomal effect of 16p13.11 copy number variation in neurodevelopmental disorders. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e61365. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Butler MG. Clinical and genetic aspects of the 15q11.2 BP1-BP2 microdeletion disorder. J. Intell. Disabil. Res. 2017;61:568–579. doi: 10.1111/jir.12382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rafi SK, Butler MG. The 15q112 BP1-BP2 microdeletion (Burnside-Butler) syndrome: In silico analyses of the four coding genes reveal functional associations with neurodevelopmental phenotypes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020 doi: 10.3390/ijms21093296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Breman A, et al. Prenatal chromosomal microarray analysis in a diagnostic laboratory; experience with > 1000 cases and review of the literature. Prenat. Diagn. 2012;32:351–361. doi: 10.1002/pd.3861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bardin R, et al. Cytogenetic analysis in fetuses with late onset abnormal sonographic findings. J. Perinat. Med. 2017;27:975–982. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2017-0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available upon request by contact the corresponding author.