Abstract

Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) is home to approximately ¼ of the global livestock population, which in the last 60 years has increased by factors of 2.5–4 times for cattle, goats and sheep. An important resource for pastoralists, most livestock live in semi-arid and arid environments, where they roam during the day and are kept in enclosures (or bomas) during the night. Manure, although rich in nitrogen, is rarely used, and therefore accumulates in bomas over time. Here we present in-situ measurements of N2O fluxes from 46 bomas in Kenya and show that even after 40 years following abandonment, fluxes are still ~one magnitude higher than those from adjacent savanna sites. Using maps of livestock distribution, we scaled our finding to SSA and found that abandoned bomas are significant hotspots for atmospheric N2O at the continental scale, contributing ~5% of the current estimate of total anthropogenic N2O emissions for all of Africa.

Subject terms: Biogeochemistry, Climate sciences

Africa houses approximately one third of the global cattle, sheep and goat population. Here the authors show that manure accumulation in livestock enclosures can emit significant quantities of the greenhouse gas N2O for decades after abandonment, totaling 5% of continental anthropogenic N2O emissions.

Introduction

Anthropogenic disturbance of the global nitrogen (N) cycle has led to significant increases of atmospheric N2O concentrations from pre-industrial levels of 270 ppbv to 331.1 ppbv in 20181. This has been mainly attributed to the increasing use of synthetic fertilizers since the 1950’s to boost crop production2; however, N2O emissions associated with manure management is also one of the key drivers of atmospheric N2O increase since pre-industrial times3,4, with its current contribution estimated at 0.33 Tg N2O yr−1 or 3% of all anthropogenic N2O sources5. Africa contains 20%, 27%, and 32% of the global cattle, sheep, and goat populations6, with the majority of these populations roaming in semi-arid and arid environments (63%, 82%, and 70%, respectively). Forming the economic backbone of pastoralist communities, livestock numbers have increased dramatically in the last 60 years, e.g., cattle increased from ~120 Mio head in 1960 to >350 Mio in 20187 (Supplementary Fig. 1). These livestock are typically allowed to roam during the day for grazing and are held in temporary enclosures (in Swahili boma; in Afrikaans kraal) during the night, which can be used and subsequently abandoned any time from 1 month up to ~10 years. How the increase in livestock numbers, lack of manure spreading, and boma use and abandonment may have affected continental N2O emissions remains uncertain.

Grazing by livestock leads to a significant concentration of N in excreta, especially at low to medium feed quality, as only 7–33% of the ingested N is metabolized and the remaining N is excreted as dung or urine8,9. This change in N cycling may be particularly important in the semi-arid and arid regions of SSA (as well as other parts of the world), where pastoralist communities practice livestock production in traditional ways (Supplementary Fig. 2). Pastoralist communities do not typically use manure for fertilizer, as they do not produce crops in large amounts, if at all. As a result, manure accumulates in bomas, which after years can be up to several meters in height. Bomas are periodically abandoned when communities decide to move owing to, e.g., changes in resource availability. Manure remains in place, forming islands of soil fertility high in C, N, and P, which ultimately increases spatial heterogeneity in savanna landscapes and supports increased plant biomass and forage quality for many decades10,11. Bomas remain visible in the landscape even after years of abandonment as grassy glades, which attract wildlife, particularly large herbivores, who in turn deposit dung and maintain bomas as nutrient hotspots for decades up to thousands of years12,13.

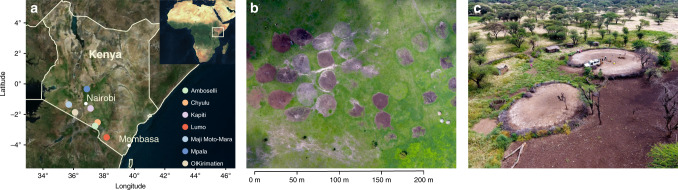

Although a number of studies have focused on the importance of abandoned bomas as soil fertility hotspots and their role in landscape and ecosystem diversity10–13, the importance of bomas as possible landscape hotspots of soil N2O emissions remains unexplored. Other studies across various systems and climates have shown that N2O emissions are positively related to soil N availability14. To test the hypothesis that bomas are spatial hotspots of N2O emissions in semi-arid and arid regions of SSA at decadal time scales, we measured fluxes at abandoned bomas across an age gradient as well as in adjacent savanna sites in Kenya, East Africa (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Location of study sites and aerial photos of bomas.

a Position of measuring locations across Kenya; b aerial picture of bomas at Kapiti Research Station; and c measurement of N2O fluxes at boma sites at Ol Kirimatien Group Ranch in South-west Kenya.

N2O fluxes were measured using the fast-box chamber method15 at seven different locations across Kenya at a total of forty-six boma sites, differing in age after abandonment (0.1–40 years) and at 22 adjacent savanna sites. In total, 257 flux measurements were conducted during the wet and dry seasons in 2018–2019 and were complemented by measurements of soil temperature and gravimetric water content. At all sites, we quantified the concentrations of soil C and N content at 0–10 cm depth, and at 0–1 m depth at a subset of sites (Kapiti Research Station, Mpala Research Centre, and Ol Kirimatien Group Ranch). Bomas that were abandoned from 0 to 15 years generally had no or little vegetation cover, likely a result of high nutrient concentrations. We therefore recorded vegetation presence and absence at each measuring site. We also observed an organic layer thickness of >0.3 m, indicating that the boma was used for consecutive years. In order to estimate measurement biases associated with day-time sampling, we investigated diurnal patterns of N2O emissions at a boma site at Kapiti Research Station. Furthermore, we explored short-term effects of rainfall on N2O fluxes by simulating a rain event by artificially adding water to a number of different bomas and adjacent savanna sites at the Mpala Research Centre.

Our results show that abandoned bomas remain active hotspots for N2O emissions for at least four decades, remaining about one order of magnitude higher than the savanna. Scaling this finding to SSA reveals that bomas are a neglected source for atmospheric N2O at the continental scale, with emissions more than doubling due to the increase in livestock in semi-arid and arid environments in the last 60 years. Based on our calculations, we estimate that bomas currently contribute about 5% of the current total anthropogenic N2O emissions for the continent of Africa.

Results and discussion

Comparing N2O fluxes from savanna and abandoned boma sites

In agreement with earlier studies11,12, we found higher C and N concentrations and stocks in the top 0–20 cm (in our study up to a magnitude higher) than in adjacent savanna soils, especially in bomas that were used for more than one year (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 3). N2O fluxes at boma sites (n = 46) varied over five orders of magnitudes from 9.3–10,266 µg N2O-N m−2 h−1 (mean: 643 ± 255 µg N2O-N m−2 h−1, n = 187 flux measurements in total), whereas fluxes at savanna sites (n = 22) had lower variation and were on average two orders of magnitudes lower (mean: 5.5 ± 1.0 µg N2O-N m−2 h−1, range: –0.7 to 15.9 µg N2O-N m−2 h−1, n = 70 flux measurements). Boma sites without vegetation (n = 18) emitted significantly more N2O (981 ± 408 µg N2O-N m−2 h−1, n = 107) than older boma sites (n = 28), which had plant cover (119 ± 48 µg N2O-N m−2 h−1, n = 80). Bomas with an organic layer thickness > 0.3 m (n = 24) showed significantly higher N2O emissions (1125 ± 471 µg N2O-N m−2 h−1) than bomas with a shallow organic layer (n = 22) (119 ± 40 µg N2O-N m−2 h−1)16.

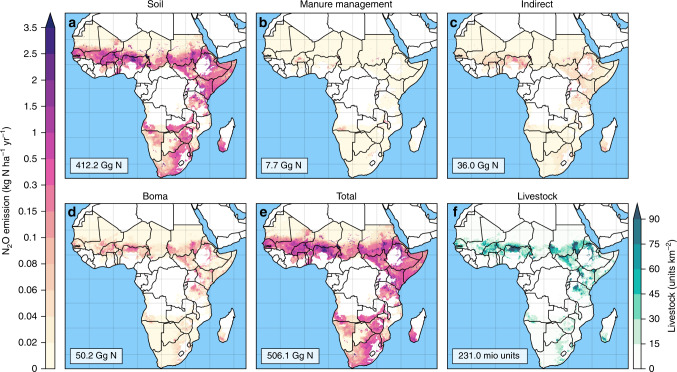

N2O fluxes declined exponentially with time since boma abandonment (Fig. 2), this also corresponded to a negative correlation of soil N content (%) with boma age (Supplementary Fig. 4), which was consistent with our hypothesis and previous studies14.

Fig. 2. N2O fluxes from bomas (0.1–40 years old) and savanna sites.

This figure shows data for bomas sampled in Kenya from 0.1 to 40 years in comparison with fluxes at adjacent savanna sites. Round symbols refer to boma sites with organic layer thickness of <0.3 m, whereas triangles indicate that the organic layer thickness is >0.3 m. Bomas without vegetation cover are marked by orange symbols, whereas blue symbols show bomas with vegetation cover. Details on the regression are given in Supplementary Table 2. The 95% confidence interval for the regression is highlighted in gray. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean for each boma. Distribution of fluxes for adjacent savanna sites are summarized in a box plot (dark line depicts the median; box shows 25–75% percentiles, and whiskers depict range of measurements). Given their small magnitude, savanna sites were not considered as background in the boma flux calculations.

There was no relationship between N2O fluxes and soil moisture across the 46 boma sites in our data set. However, the simulated rainfall event enhanced average N2O fluxes by a factor of 3 for ~60 hours (from 20.0 ± 4.2 µg N2O-N m−2 h−1 to 56.1 ± 12.6 µg N2O-N m−2 h−1) (Supplementary Fig. 5). This contrasted with results observed for the neighboring savanna sites, which showed no enhancement of N2O fluxes with rainfall (before: 0.6 ± 0.5 µg N2O-N m−2 h−1, after simulated rainfall: 0.9 ± 0.5 µg N2O-N m−2 h−1). With respect to diurnal variation, measurements revealed that soil N2O fluxes were approximately two times higher in the afternoon than in the morning hours (Supplementary Fig. 6). We performed the measurements in this study in the morning hours and on days without rainfall, so we consider these measurements to be biased towards the low-end of potential N2O emission estimates.

Bomas as sources of N2O at the continental scale

To assess whether our findings of elevated N2O fluxes from bomas are relevant at the scale of Africa and at decadal time-periods, we first calculated cumulative N2O emissions for a 40-year period following abandonment using the exponential regression curve of Fig. 2. We consider this to be a conservative estimate because we did not include the range of variation from diurnal measurements or pulse emissions of N2O following rainfall events. This calculation resulted in a cumulative mean emission rate of 25 g N2O-N per m−2 boma area over 40 years (95% confidence interval, CI: 13.3–48.1 g N2O-N m−2) and a mean annual rate of 0.62 g N2O-N m−2 (CI: 0.33–1.20 g N2O-N m−2 yr−1). In order to scale up these estimates to the continent, we multiplied the mean 40-year emission rate with the total abandoned boma areas in semi-arid and arid environments in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), which we estimated for each year. The calculation of annual abandoned total boma area was based on information on animal numbers, area per livestock in bomas, average number of years of boma use, an average number of bomas used simultaneously per herder, and the fraction of bomas that were not extracted for manure (i.e., as fertilizer or for selling) (Supplementary Fig. 7). We developed a range estimate by simulating various scenarios for the combination of the different scaling parameters to explore overall uncertainty of our continental boma N2O emissions estimate by Monte Carlo simulation (see Methods, Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8).

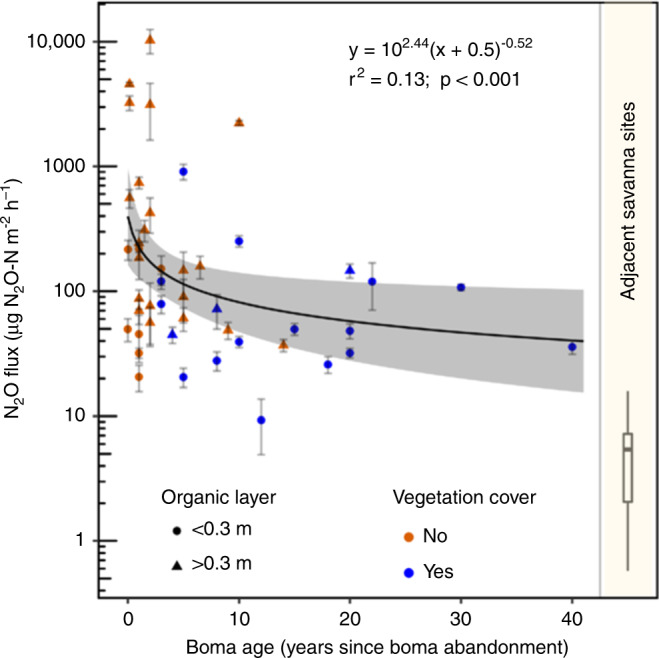

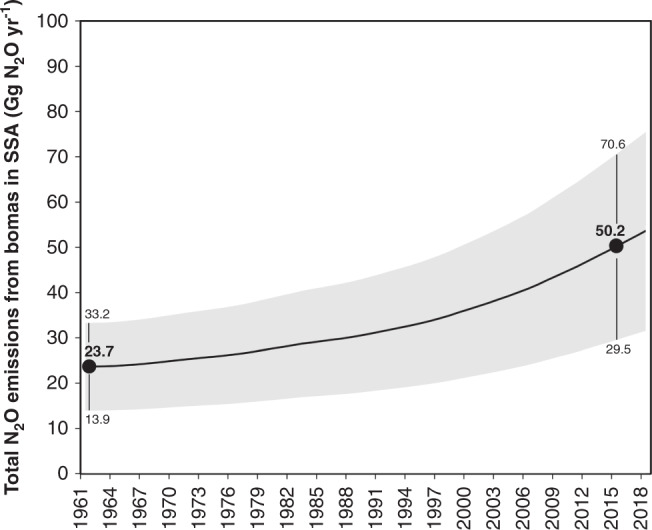

According to our calculations, the median of total N2O emissions from bomas in semi-arid and arid climates of SSA is ~50.2 Gg N2O yr−1 (25–75th percentile: 29.5–70.6 Gg N2O yr−1, Fig. 3)16, with the highest N2O emissions in countries that have the highest numbers of livestock in pastoral systems, including Ethiopia, North- and South-Sudan, Kenya, Tanzania and Burkina Faso and Nigeria (Fig. 4). This is one magnitude higher than estimates of N2O emissions associated with manure management as documented in the EDGAR5 database for the same land area (7.7 Gg N2O yr−1) and comprises 5% of the current estimate of total anthropogenic N2O emissions for Africa at continental scale (EDGAR5 = 974 Gg N2O yr−1).

Fig. 3. Change in the source strength of abandoned bomas from 1961 to 2018.

The emission trend was based on changes in livestock numbers in semi-arid and arid SSA and the calculation scheme outlined in “Methods”. The bold line indicates the median value, while the gray shaded area represents the upper and lower quartiles.

Fig. 4. Sources of agricultural N2O fluxes and livestock units.

Given are N2O fluxes for semi-arid and arid regions in SSA based on EDGAR55 (a: soil; b: manure management; c: indirect emissions) and the total N2O emissions from bomas d from this study, and the resulting sum of total agricultural N2O emissions (=a+b+c+d) e. f depicts the livestock density for cattle, sheep, and goats in semi-arid and arid environments in Africa6. Livestock units23 summarize total number of cattle, sheep, and goats with .

Our measurements of N2O emissions from bomas and resulting estimates for semi-arid and arid regions in SSA are relevant in the context of current uncertainties of anthropogenic sources and drivers of N2O increases in the atmosphere17, showing a systematic underestimation of N2O emissions from manure management at the scale of Africa. In 40 years following abandonment, an additional 1.34% (95% confidence interval, CI: 0.90–2.56%; Supplementary Note 1) of the accumulated manure N is directly emitted in form of N2O that is not considered by current IPCC methodology18,19. In addition, Africa’s population of livestock has increased exponentially in the last 60 years7 (Supplementary Fig. 1), and our results indicate that observed increases in atmospheric N2O concentration may not only be linked to the global increase in the use of fertilizers20, but also to numbers of livestock in semi-arid and arid regions and the manure accumulation in bomas (Fig. 4).

It was recently suggested that Africa contributed 20% to the observed increase in global N2O emissions between 2000 and 2005 and 2010 and 2015 (or ~0.32 Tg N yr−1 of the total 1.6 Tg N yr−1 increase)17. Our estimate of the increase in emissions from the abandoned bomas during this period is 0.006 Tg N yr−1 (or only 2% of this increase) and therefore cannot explain this difference. However, our measurements from abandoned bomas are biased low, and direct N2O emissions from active bomas and indirect N2O emissions from leached or volatilized N, which have not been investigated here, may have also contributed to the observed increase in N2O emissions from the African continent, and warrants further research.

Given the remoteness of settlements of pastoral communities, there is unlikely to be an economically viable solution for transporting and selling manure. However, simple management practices such as the use of mobile bomas, which can be changed at monthly intervals21, annual spreading or the distribution of manure upon abandonment on the adjacent rangeland, would not only significantly decrease N2O emissions, but could also work to restore rangeland productivity as nutrients are redistributed in the landscape, thereby creating larger areas with improved, nutrient-rich forage22.

Conclusion

Our results show that N2O emissions from bomas have not been adequately considered, and therefore we recommend that current methodology for estimating N2O emissions from livestock held by pastoralists in semi-arid and arid landscapes in SSA and elsewhere should be refined to include abandoned bomas. Moreover, further research in understanding indirect emissions due to N losses from bomas along hydrological (leaching, surface run-off) and atmospheric (mainly NH3 volatilization) pathways is needed to develop a full picture of the importance of abandoned bomas as a source for atmospheric N2O. To decrease the environmental N footprint of bomas, improved but simple manure management measures should be considered.

Methods

Field N2O flux measurements

At seven different semi-arid and arid savanna regions in Kenya (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 9), N2O measurements from soils at 46 boma sites and 22 adjacent reference sites (undisturbed savanna) were carried out. At each boma and control site, 3–7 plots were chosen randomly for flux measurements. Local members of the pastoral communities, including herders and/or community elders were interviewed for information on the time since abandonment of each boma.

N2O fluxes from bomas were measured using the fast-box chamber method15, deploying an ultra-portable greenhouse gas analyzer of ABB-Los Gatos Research Inc. (Modell 909–0041). A gas-tight, vented chamber (0.3 × 0.2 × 0.15 m) was pressed against the ground on foam frames for 4–7 min, during which time sample air was pumped from the headspace of the chamber to the analyzer and returned to the chamber thereafter. In this way, changes in headspace N2O concentrations were continuously measured over the sample period, with a running average of every 5 s. Linear regression over the sample period was used to calculate fluxes. The detection limit for N2O fluxes was <1 µg N2O-N m−2 h−1.

Soil and environmental parameters

Environmental variables including gravimetric and volumetric soil water content, soil and air temperatures, organic layer thickness, and aboveground plant biomass (if present) were measured in all plots. At selected boma sites, we also measured total N and C stocks for 0–1 m depth (see Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 9). We noted crusts only on bomas that were abandoned for <5 years. As nutrient concentrations diminish with time, vegetation starts to grow on abandoned bomas. Furthermore, owing to rainfall and trampling of wild animals and sometimes of livestock, crusts are fragile, fragmented and <5 mm in thickness.

Identifying drivers of N2O fluxes

For regression analyses on controlling parameters of N2O fluxes (Supplementary Tables 2–4; Supplementary Notes 2 and 3), we calculated an average flux per boma (or control) site for our analyses. We used Welch’s t test to compare N2O fluxes from boma and adjacent savanna plots, as well as for comparing N2O fluxes from vegetated plots with those from bare soil plots and from plots of high versus low organic layer depth (>0.3 m versus <0.3 m). A depth of 0.3 m was chosen as a threshold value to distinguish between bomas that were used for 1–2 years and those that were used consecutively for >2 years, as manure accumulates at a rate of 0.1 to 0.15 m yr−1.

To determine the effect of potential driver variables on N2O fluxes (log10), we explored a multiple regression model for gravimetric soil water content (including a quadratic term to allow a decrease at high soil water content) as well as soil temperature, organic layer N, organic layer C, vegetation cover, time since abandonment, and organic layer depth (Supplementary Table 3 and 4, multiple r2 = 0.41, adjusted r2 = 0.26). Only soil temperature significantly affected N2O fluxes in the multiple linear regression model. In addition, a mixed modeling approach was used to assess whether random effects (e.g., on site) improved the model. This did not improve the model performance, indicated by a higher AIC (138 versus 91).

To estimate overall N2O emissions of bomas over time, we built a simple regression model relating boma age (since abandonment) to average boma N2O fluxes on a log-log scale (Supplementary Table 2, displayed in Fig. 2). Since the variability explained by this model is moderate (r2 = 0.13), there are relatively wide confidence intervals (Fig. 2), but these reflect the full variability of our measured N2O fluxes. From the model fit, we calculated the cumulative N2O emission on a per-area basis over 40 years, i.e., including oldest abandoned bomas investigated.

Upscaling N2O fluxes from bomas to SSA

The estimated N2O flux over the 40 years period served as an input for upscaling measurements, thereby taking into account uncertainty of estimated N2O flux as well as the uncertainty in further parameters used for spatial upscaling (Supplementary Fig. 7 and below).

Gridded estimates of livestock numbers were taken from Gilbert et al.6 (Fig. 4f) and restricted to semi-arid and arid environments of SSA (Supplementary Fig. 10). The calculation of total livestock units for pastoral systems (i.e., sum of cattle+goat+sheep) was based on livestock conversion factors as reported by Houerou and Hoste23, which are for cattle in herd 0.7 and for sheep and goat 0.1. Information on the boma area per livestock unit was obtained from Okello et al.24. Based on interviews with herders and local experts it became evident that several bomas are used at the same time as herders move their livestock across grazing areas in response to the availability of forage and water and that at least two bomas are simultaneously in use on average—one close to a semi-permanent homestead and one within seasonal grazing areas. The number of years that a boma is used varies considerably across sites, between 1 month to up to several years in this study and confirmed by several others12,25, with 3.7 years being the central value. Information on manure extraction from bomas was not available. Based on interviews with herders we assumed for 90% of bomas manure is either not extracted or irregularly or only partially extracted. Manure use increases in regions with mixed farming, i.e., simultaneous crop and livestock production and short (<2–5 km) transport distances, and with increasing humidity26, but is hardly existing in remote regions with livestock production only, which are in the focus of our study.

Total N2O emissions from bomas in semi-arid and arid environments of SSA were calculated as follows:

Step 1: Calculation of total livestock numbers (TLN) by combing population data for cattle, goat and sheep and converting to a single livestock unit, based on conversions for semi-arid and arid environments23.

Cattle, sheep, goat: total number of cattle, sheep, goat

Step 2: Calculating boma use intensity (BUI)

BUI = BAL * NB * FMB/YB

with

BAL: boma area per livestock, the work of Okello et al.24 indicates that the space for one cattle in a boma is ~4–16 m2, central value: 10

NB: number of bomas in use at the same time, interviews and expert knowledge, central value = 2.5

FMB: Fraction of bomas without use of manure, interviews and expert knowledge, central value = 0.9

YB: years of boma use, interviews and expert knowledge, central value = 3.7

Note: in 2015 the total area of newly abandoned bomas in semi-arid and arid SSA was estimated at 1792 km2. The total area of semi-arid and arid SSA equals 15.16 Mio km2. Thus, the area of newly abandoned bomas equals 0.11‰ of the total area of semi-arid and arid SSA.

Step 3: Calculating N2O emission intensity (N2O_int)

N2O_int = N2O x N2O_years * 4/28

N2O: mean average annual N2O flux from bomas, this study

N2O_years = observed minimum number of years with N2O fluxes significantly greater than at adjacent savanna sites = 40 years

44/28 = conversion of N2O-N to N2O

Step 4: Calculating total N2O emissions from bomas in semi-arid and arid environments

Or (summarizing steps 1–3)

Supplementary Fig. 7 shows histograms, probability distribution functions, and cumulative distribution functions of the different variables used for assessing the uncertainty of the upscaling procedure. To provide statistics such as median, 25 and 75% percentile values, etc. for upscaled N2O emissions we used the Latin hypercube sampling (LHS) method. The concept behind LHS is to divide the cumulative curve of each variable into n equally probable intervals and take a random sample at each probable interval for each variable. The n values obtained for each of the components were then paired with each other to recalculate the equation n times for assessing the uncertainty in a prediction equation.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank George Wanyama, Francis Njenga, and Sheila Okoma for their invaluable support for laboratory analyses. We also acknowledge the staff at Mpala Research Centre for their logistical support. K.B.B. and L.M. received funds via the CGIAR Research Program on Livestock. We thank all donors that globally support our work through their contributions to the CGIAR system. K.B.B., R.K., C.W., and K.F. were partly funded by the Helmholtz ATMO “Atmosphere and Climate” program. J.R. was funded by a grant within the UPSCALERS project (Upscaling Site-Specific Climate-smart Agriculture and Land use practices to Enhance Regional production Systems in West Africa) as funded by the African Union Commission.

Author contributions

K.B.B., G.G., R.K., and L.M. conceived and designed the study. K.B.B., G.G., L.M., R.K., and M.B. conducted the field work. K.B.B., G.G., J.R., C.W., and K.F. analyzed data, developed the upscaling approach, and established uncertainty analyses. K.B.B. wrote the first draft with all authors contributing to further revisions.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available in the figshare repository 10.6084/m9.figshare.12793868. Raw data files and graphic files are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Martin Chantigny, Arezoo Taghizadeh-Toosi, and other, anonymous, reviewers for their contributions to the peer review of this work. Peer review reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-020-18359-y.

References

- 1.WMO. The state of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere based on global observations through 2018. WMO Greenhouse Gas Bulletin. 2019;15:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.IPCC. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, R.K. Pachauri and L.A. Meyer (eds)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 151 pp. (2014).

- 3.Davidson EA. The contribution of manure and fertilizer nitrogen to atmospheric nitrous oxide since 1860. Nat. Geosci. 2009;2:659–662. doi: 10.1038/ngeo608. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tubiello, F. N. et al. Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use Emissions by Sources and Removals by Sinks 1990–2011 Analysis. FAO Statistics Division Working Paper Series ESS/14-02 (2014).

- 5.Janssens-Maenhout G, et al. EDGAR v4.3.2 Global Atlas of the three major greenhouse gas emissions for the period 1970–2012. Earth Syst. Sci. Data. 2019;11:959–1002. doi: 10.5194/essd-11-959-2019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilbert M, et al. Global distribution data for cattle, buffaloes, horses, sheep, goats, pigs, chickens and ducks in 2010. Sci. Data. 2018;5:180227. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2018.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QA, visited in March 20, 2020.

- 8.Silva LFP, et al. Nitrogen recycling and feed effificiency of cattle fed protein-restricted diets. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2019;59:2093–2107. doi: 10.1071/AN19234. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gourley CJ, et al. Nitrogen use efficiency and manure management practices in contrasting dairy production systems. Agric. Ecosys. Environm. 2012;147:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2011.05.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muchiru J, et al. The role of abandoned pastoral settlements in the dynamics of African large herbivore communities. J. Arid Environ. 2008;72:940–952. doi: 10.1016/j.jaridenv.2007.11.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muchiru J, et al. The impact of abandoned pastoral settlements on plant and nutrient succession in an African savanna ecosystem. J. Arid Environ. 2009;73:322–331. doi: 10.1016/j.jaridenv.2008.09.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blackmore AC, et al. The origin and extent of nutrient-enriched patches within a nutrient-poor savanna in South Africa. J. Biogeogr. 1990;17:463–470. doi: 10.2307/2845378. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marshall F, et al. Ancient herders enriched and restructured African grasslands. Nature. 2018;561:387–390. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0456-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yao Z, et al. Soil N intensity as a measure to estimate annual N2O and NO fluxes from natural and managed systems. Curr. Opin. Environm. Sust. 2020;47:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2020.03.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hensen A, et al. Low cost and state of the art methods to measure nitrous oxide emissions. Environ. Res. Lett. 2013;8:025022. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/8/2/025022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Butterbach-Bahl, K. et al. Data on nitrous oxide emissions and flux measurements at various boma sites in Kenya. figshare 10.6084/m9.figshare.12793868 (2020).

- 17.Wells KC, et al. Top-down constraints on global N2O emissions at optimal resolution: application of a new dimension reduction technique. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018;18:735–756. doi: 10.5194/acp-18-735-2018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.IPCC 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories, prepared by the National Greenhouse Gas Inventories Programme. Eggleston, H. S., Buendia, L., Miwa, K., Ngara, T., and Tanabe, K. (eds) IGES Japan (2006).

- 19.IPCC 2019 Refinement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories. Gómez, D., Irving, W. (eds), IGES Japan (2019).

- 20.Winiwarter W, et al. Technical opportunities to reduce global anthropogenic emissions of nitrous oxide. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018;13:014011. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/aa9ec9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poresnky LM, et al. Generation of ecosystem hotspots using short-term cattle corrals in an African. Savanna Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 2015;68:131–141. doi: 10.1016/j.rama.2015.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reynolds AQ, et al. Ecological sites: can they be managed to promote livestock production? Rangelands. 2019;41:239–243. doi: 10.1016/j.rala.2019.07.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le Houerou HN, Hoste CH. Rangeland production and annual rainfall relations in the Mediterranean basin and in the African Sahelo-Sudanian zone. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 1977;30:181–189. doi: 10.2307/3897463. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okello MM, et al. Human-carnivore conflicts in private conservancy lands of Elerai and Oltiyiani in Amboseli area, Kenya. Nat. Res. 2014;5:375–391. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Western D, Dunne T. Environmental aspects of settlement site decisions among pastoral Maasai. Hum. Ecol. 1979;7:75–98. doi: 10.1007/BF00889353. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Onduru DD, et al. Manure and soil fertility management in sub-humid and semi-arid farming systems of Sub-Saharan Africa: experiences from Kenya. Int. J. Agric. Res. 2008;3:166–187. doi: 10.3923/ijar.2008.166.187. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are available in the figshare repository 10.6084/m9.figshare.12793868. Raw data files and graphic files are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.