Abstract

Nitrogen fixation, the six-electron/six-proton reduction of N2, to give NH3, is one of the most challenging and important chemical transformations. Notwithstanding the barriers associated with this reaction, significant progress has been made in developing molecular complexes that reduce N2 into its bioavailable form, NH3. This progress is driven by the dual aims of better understanding biological nitrogenases and improving upon industrial nitrogen fixation. In this review, we highlight both mechanistic understanding of nitrogen fixation that has been developed, as well as advances in yields, efficiencies, and rates that make molecular alternatives to nitrogen fixation increasingly appealing. We begin with a historical discussion of N2 functionalization chemistry that traverses a timeline of events leading up to the discovery of the first bona fide molecular catalyst system and follow with a comprehensive overview of d-block compounds that have been targeted as catalysts up to and including 2019. We end with a summary of lessons learned from this significant research effort and last offer a discussion of key remaining challenges in the field.

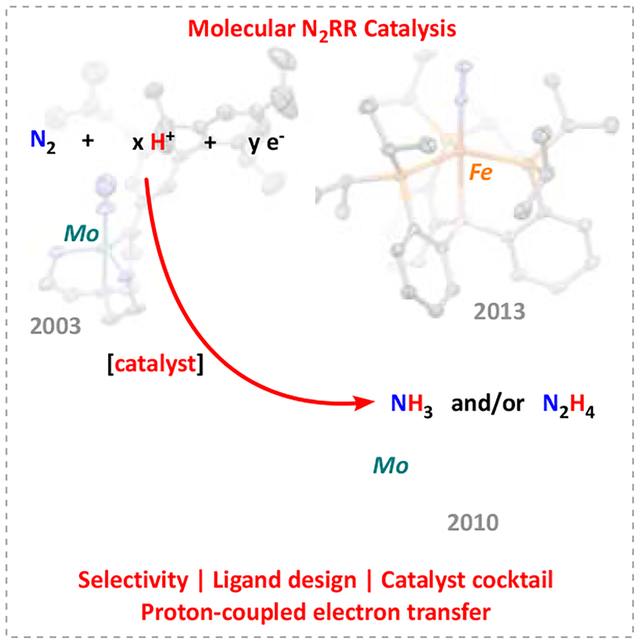

Graphical Abstract

1. INTRODUCTION TO THE FIELD OF N2 REDUCTION CATALYSIS

Catalytic nitrogen fixation is an essential chemical transformation in both biology and industry as it represents the primary means by which nitrogen (N2) from the air becomes bioavailable. This review focuses on the development and study of synthetic molecular catalysts that mediate the catalytic conversion of nitrogen to ammonia (N2-to-NH3, often abbreviated as the nitrogen reduction reaction or N2RR) in the presence of acid and reductant under moderate temperatures and pressures.

1.1. Motivation for New Ammonia Synthesis Catalyst Technologies

Conventional ammonia synthesis (i.e., Haber-Bosch) is among the most significant technological advances of the 20th century and has been critical to sustained global population growth.1 However, with operating pressures of 150–250 bar and temperatures of 400–500 °C, it has high cost demands for infrastructure leading to centralization of the manufacturing process and thus requires a global distribution system.2 This large-scale distribution and the necessary temperature and pressure to form NH3 from N2 and H2 over a solid-state Fe catalyst necessitates significant fossil fuel input with related high carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. While estimates vary, approximately 1–2% of annual global energy consumption is accounted for by conventional ammonia synthesis, with some 4% of global methane (CH4) and 60% of global hydrogen going into its production. The generation of the needed hydrogen via steam-reforming (providing for ~72% global ammonia production) accounts for nearly 0.5 gigatons of CO2 released annually.3 In addition, other environmental consequences from fertilizer use are severe, including surface and groundwater pollution from runoff, eutrophication of freshwater systems, and massive killing of aquatic organisms in coastal regions that comprise so-called dead zones due to depleted oxygen.4,5 These consequences could be mitigated if ammonia synthesis were electrified,6 and hence produced on scale, and on demand, in a distributed fashion. On demand distributed production of fertilizer could offset use (and hence production) of fertilizer that is sourced conventionally and could also be generated locally and at a rate that increases net absorption by crops (versus runoff), offering a possible environmental benefit to conventional practices in fertilizer acquisition and use.7

Although ammonia is a commodity chemical produced primarily for fertilizer (on a massive scale, ~150 million metric tons annually), it has also been identified as a promising alternative fuel. It is highly storable, easily liquefied, and has an energy density approaching half that of gasoline far exceeding that of compressed hydrogen. It can also be used as a fuel within an internal combustion engine (ICE) or via a solid-oxide fuel cell (SOFC). Moreover, globally substantial ammonia transport infrastructure and related safe-handling protocols already exist.8 For these reasons, ammonia synthesis is an extremely attractive target for electrification, especially via renewable energy technologies, requiring major advances in catalyst development. N2RR electrification would enable surplus energy in the grid, at times of excess supply, to be converted to fertilizer and/or to a storable and transportable fuel, particularly desirable in areas where wind and solar resources are vast. The eventual realization of an “ammonia fuel economy” that can contribute to diverse future energy strategies, along with technologies for on-site and on-demand ammonia fertilizer generation, will require breakthrough research discoveries in catalysis.9

1.2. Inspiration for Organometallic and Inorganic Chemistry

In contrast to the forcing conditions required in the Haber–Bosch process, certain microorganisms can fix N2 under ambient conditions, using extensive hydrolysis of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to power the delivery of H+ and e− equivalents to N2. These enzymes may hold important clues as to how H+/e− currency, potentially derived from photosynthetic water splitting, could be efficiently delivered to N2 via an appropriate catalyst. Housed within any given nitrogen-fixing organism are conserved sets of proteins—the nitrogenase enzymes—that bind and convert N2-to-NH3. Nitrogenases appear to require iron as an essential transition metal and typically contain molybdenum (FeMo-nitrogenase, most common form), with either vanadium (VFe-nitrogenase) or Fe (FeFe-nitrogenase) being assembled (and functionally active) in the absence of Mo.10,11 FeMo-nitrogenase was the first to be discovered and has been by far the most widely studied.12,13 In addition to various exogenous cofactors required for its function, this enzyme consists of an Fe-protein that delivers reducing equivalents and a MoFe-protein.10 The latter contains two structurally unique clusters. The first is the P-cluster (Fe8S7), which serves as an electron relay to the Fe-protein. The second is the M-cluster (MoFe7S9C-homocitrate), an inorganic FeMo cofactor (FeMoco, Figure 1) that mediates the catalytic bond-breaking and making steps.14

Figure 1.

X-ray structure of the FeMo-cofactor active site in the MoFe protein (PDB: 1M1N); blue = N, red = O, yellow = S, brown = Fe, gray = C, purple = Mo.13

Inorganic chemists have long puzzled (and engaged in spirited debate!) over how this cofactor operates15–19 and, in collaboration with biochemists, microbiologists, structural biologists, and spectroscopists, have pursued molecular model systems as a means of constraining hypotheses regarding viable inorganic mechanisms for catalytic N2RR. This has proven to be a remarkably rich research area. The list of talented chemists who have significantly contributed to what is now an enormous body of knowledge reads like a “Who’s Who of Inorganic Chemistry.” Fortunately, much of this work has been reviewed previously.15,20–29

The goal of this review is to be comprehensive only with respect to the comparatively recent body of literature pertaining to catalytic N2RR that is mediated by nominally well-defined synthetic complexes, in the presence of H+/e− sources. We acknowledge at the outset that much of the fascinating literature preceding such catalyst discoveries will not be detailed, except in cases where introducing background is needed to set the stage for the catalyst discoveries that will be covered. One such case is the early and pioneering work of Joseph Chatt and his co-workers.15,30 Given how central the research and ideas he and his team espoused were to the development of the broader field of N2RR catalysis, we felt it appropriate to briefly summarize some of this historical context here. The interested reader should consult a number of excellent reviews for a deeper dive into this and other early literature.15,31–34

2. DISCUSSION OF THE CHATT CYCLE

Coordination chemists began to think seriously about alternative catalyst technologies to the Haber–Bosch ammonia synthesis in the early 1960s (Figure 2). Several factors had set the stage; key among these was that, in 1963, the British Agricultural Council, led by Secretary Sir Gordon Cox, himself a coordination chemist by training, appointed the British inorganic chemist Joseph Chatt to oversee a multidisciplinary research unit dedicated toward understanding the mechanism of biological nitrogen fixation.35 It was by this time presumed that Fe and Mo were present within the active site of the single nitrogenase that was then known.36 Refreshingly, the Secretary of Agriculture must have intuited that, at its heart, the mechanism of nitrogen fixation was an inorganic chemistry problem. This took imagination and foresight, as it was not until two years later (1965) that Allen and Senoff reported their landmark (and fortuitous) discovery that N2 could coordinate as a ligand to a transition metal, via the isolation and characterization of [(NH3)5Ru(N2)]2+ (Figure 2).37,38 Hence, from the outset, the systematic study of inorganic and organometallic complexes for N2RR was established as an area of bioinorganic model chemistry.

Figure 2.

Timeline (1930 to present) of selected advances in nitrogen fixation catalysis by synthetically well-defined complexes.18,37,48–56

Fundamental studies toward understanding the binding, activation, and conversion of N2 to protonated intermediates and/or products at well-defined transition metal centers were deemed essential to helping formulate and constrain hypotheses concerning the biological process. The Unit of Nitrogen Fixation, first located at the University of London but soon thereafter relocated to Sussex, was highly innovative in its approach and comprised not just chemists but also microbiologists, biochemists, and geneticists, working collectively.39

Prior to his appointment leading the Unit of Nitrogen Fixation, Chatt (with Duncanson), contemporaneously with Dewar,40 played a key role in defining and generalizing the bonding of olefins to transition metals, describing the interaction by both sigma donation (from the olefin π-electrons to the metal) and π-bonding (from the metal to the olefin π-antibonding orbital).41 This type of bonding is today often referred to as the Dewar–Chatt–Duncanson model.42 This proposal paralleled what had already been developed for metal carbonyls43 and anticipated the type of bonding interactions in metal dinitrogen complexes.

Following Allen and Senoff’s isolation of a terminally bound Ru(N2) complex,38 it was not much of a stretch to postulate that synthetic metal complexes might be able to bind and catalyze N2RR under suitable conditions. A surge of relevant research activity thus followed, not just in the UK but around the world, and within just a decade profound progress was made.15,33,34 For instance, Shilov and his collaborators in the former Soviet Union reported the exciting discovery that certain transition metal mixtures containing, for example, molybdenum precursors mixed with Mg(OH)2, could in fact catalyze N2 reduction to N2H4 and NH3 in alcohol/water mixtures in the presence of reducing agents such as sodium amalgam.20,44–47 But it was the work of Chatt and his team at Sussex, via their careful, rigorous preparation and study of M(N2) and M(NxHy) complexes, that most directly laid the groundwork for the well-defined synthetic N2RR catalysts that have emerged thus far.15,32

2.1. The Chatt Cycle As It Is Commonly Known

While M(N2) complexes for a range of TMs (e.g., Ru, Re, Os, Co) were known by the end of the 1960s, much of the early biomimetic work focused on Mo(N2) (and related W(N2)) complexes.32–34,57 Since the work of Bortels in 1930, it was long-held dogma that molybdenum was essential to nitrogen fixation48 and this fact, combined with the practical reality that so many M(NxHy) complexes featuring Mo (and W) proved accessible, helped focus model chemistry research in this area. Relatedly, biochemical experiments had suggested that nitrogenase activity was highly sensitive to alteration at or near the molybdenum site, such as at the homocitrate ligand.10 Chatt’s team established N2 binding and activation at Mo (and W), and showed that the coordinated N2 ligand could be protonated to release NH3 (and hydrazine) in variable yield (as high as 90% for W(PMe2Ph)4(N2)2 with H2SO4, assuming one N2 equiv is released as gas)58 depending on a range of factors (Figure 3). What is more, the group was able to identify a number of M(NxHy) complexes, including M(N),59 M(NNH2),60–64 M(NHNH2),65 M(NNH),60,66,67 M(NNH3)68,69 species (M = Mo or W), that likewise underwent protonation to release NH3 in similar yields.

Figure 3.

Protonation of M(cis-N2)2(PMe2Ph)4 and M(NxHy); M = Mo or W.15

These findings led Chatt to propose a simple scenario in which triple functionalization at Nβ leads to the release of NH3 and a nitride intermediate. This scenario is now known as the Chatt cycle, and a simplified version is depicted below (Figure 4).30 Worth noting is that while examples of the types of M(NxHy) species invoked in the Chatt cycle could be generated, most typically these species were not characterized in the same formal state of oxidation as invoked in the catalytic scheme.26 It would not be until Schrock’s discoveries some 30 years later50,70 that well-characterized examples of the proposed catalytic Mo(NxHy) intermediates, in an oxidation/protonation state matching the envisaged catalytic cycle, were discovered (Figure 11). Critically, this triamidoamine-ligated Mo system would also prove to be the first catalyst for nitrogen fixation, thereby cementing the importance of the Chatt cycle, sometimes formulated as the Schrock or “distal” cycle in the contemporary literature, in the field. Equally important, Chatt and his team underscored via their work the value of preparing and carefully studying well-defined M(NxHy) model complexes to test the validity of possible pathways for nitrogen fixation.

Figure 4.

Scheme demonstrating the distal (or Chatt) cycle for nitrogen fixation. In the modern literature, this cycle is also sometimes referred to as the Schrock cycle. Ligands on molybdenum are omitted for clarity.30

Figure 11.

(Top) Protonation reactions of (HIPTN3N)Mo(L) (L = CO or N2). For the CO analogue, pulse EPR (ENDOR) data indicated protonation at an amido arm; for N2, the site of protonation remains unknown;102 (middle) protonation/reduction reactions of the L = N2 and N analogues gave rise to [Mo]-NNH and [Mo]-NH3+; (bottom) reduction of [[Mo]-NH3]+ under N2 gives [Mo]-N2 in ~10% yield; [Mo] = (HIPTN3N)Mo.99

2.2. Alternative Mechanistic Scenarios for NH3 Formation

While it is the aforementioned cycle for which Chatt is most often credited, he and his co-workers also envisaged alternative scenarios that could account for NH3 (and N2H4) production via intermediates not included on the so-called Chatt pathway. For example, protonation of an M(NHNH2) or M(NH2NH2) intermediate can release hydrazine or ammonia (Figure 5).65 It is perhaps ironic that, although a M(NHNH2) species is not commonly referred to as a “Chatt-type” intermediate, it was his group that first prepared such a species (for W) and considered its direct relevance to NH3 release.61

Figure 5.

An alternative to the Chatt pathway that can account for productive NH3 formation.

Although Schrock’s best known contribution to N2-fixation chemistry, the (HIPTN3N)Mo system (HIPTN3N = 3,5-(2,4,6-i-Pr3C6H2)2C6H3NCH2CH2]3N3−), appears to proceed via a distal reaction pathway, during the mid-1980s, Schrock and co-workers also reported important results regarding alternative mechanisms for NH3 formation in Cp*-Group VI (Cp* = C5Me5−) compounds. During their study of the general reactivity of (Cp*)M (M = Mo, W) complexes with NxHy ligands, they found that protonation reactions of the N2 complexes gave (primarily) NH3, but studies suggested that the pathway for NH3 release was unlikely to involve the terminal nitride, M(N), intermediate.71 Instead, protonation of the hydrazido(2−) complex, (Cp*)W(Me)3(NNH2), occurred at Nα to give [(Cp*)W(Me)3(η2-NHNH2)]OTf —a reversible process in the presence of base. This is an interesting transformation, as one can ask whether the kinetic site of protonation of (Cp*)W(Me)3(NNH2) is at Nα or Nβ, and whether protonation occurs prior to, or following, isomerization of the nitrogenous ligand from an η1- to η2-form (Figure 6). A subsequent study by Norton provided compelling evidence for initial protonation at Nβ to generate [(Cp*)W(Me)3(NNH3)]+, followed by isomerization to give [(Cp*)W(Me)3(η2-NHNH2)]+.72 While the W(NNH3)+ species in this system was not derived from N2, the aforementioned transformations underscore that a so-called Chatt (or distal) intermediate can isomerize to an alternating intermediate W(η2-NHNH2).72

Figure 6.

Protonation of the hydrazido(2−) complex, (Cp*)W(Me)3(NNH2), can initially occur at Nα or Nβ, but ultimately gives [(Cp*)W(Me)3(η2-NHNH2)]+—a reversible process in the presence of NEt3. It remains unclear whether protonation occurs at the η1- or η2-form of the hydrazido(2−) species.72

With the (Cp*)M platform, the Schrock group could also synthesize hydrazine intermediates [(Cp*)M(Me)3(NH2NH2)]+. Reduction of these intermediates with sodium amalgam led to the formation of NH3 and (Cp*)M(NH). Indeed, reacting this platform with excess acid and reductant in the presence of hydrazine led to the catalytic formation of NH3 in yields up to 95% (note that the maximum yield for hydrazine disproportionation is 67%).73,74 This work, thus, conclusively demonstrated that NH3 formation does not necessarily proceed via the Chatt cycle, but rather that formally “alternating” intermediates M(NHNH2) and M(NH2NH2) can also lead to NH3 formation. The potential of such intermediates to contribute to hydrazine formation will be discussed later in the context of catalysis with Fe complexes.

Much of the work from Chatt was pursued in the absence of exogenous reductant and thus necessarily focused on zerovalent Mo and W species that could themselves provide the electrons required for nitrogen fixation. Nonetheless, Chatt, as early as 1969, noted that “the reduction of complexed (di)nitrogen requires specific reagents or conditions, and these may be just as elusive as the first nitrogen complexes.”75

Schrock’s early work is not only important for its initial elucidation of hybrid mechanisms for NH3 formation, but also for its preliminary efforts to perform protonolysis experiments in the presence of external reductants. Perhaps inspired by the success of Shilov and his collaborators in achieving catalytic N2 reduction with transition metal mixtures and amalgam reductants,44,76,77 Schrock and co-workers performed protonolysis experiments using [LutH]Cl (LutH = lutidinium) of μ-bridged Group VI dinitrogen complexes, such as [(Cp*)Mo(Me)3]2(μ-N2), in the presence of ZnHg amalgam.78 Although these experiments only gave 0.62–0.72 equiv of NH3, this work provided a viable approach for future studies that would yield catalysis.

In fact, the study of nitrogen fixation has revealed that the choice of acid and reductant is critical to catalyst performance. In many ways, the reagents are as much a part of the nitrogen fixation story as the catalysts themselves, with certain systems demonstrating dramatically different results and, by implication, different mechanisms when distinct reagent cocktails are supplied.18,51,79–81 Combinations of compatible acid and reductant have moved the field forward and allowed for the discovery of new catalysts. Indeed, in recent years attention has focused how the choice of reagents also controls the overall thermochemistry of the N2RR catalysis, providing a framework toward improvement of the thermal efficiency of the catalysis. In the next section, we will detail the two successive breakthroughs made by Schrock and co-workers. The first was the application of the (HIPTN3N)Mo ligand to support a series of Chatt-cycle intermediates in the relevant oxidation states70 and the second, the discovery that these intermediates could be turned over by application of an appropriate reductant and acid,50 a combination that went on to find broad application in the field.51,82–84

Another pathway for dinitrogen fixation concerns the formal scission of dinitrogen to two metal-bound nitrides followed by the transfer of proton and electron equivalents (via PCET or otherwise) to release ammonia (vide infra in Section 4.3 for an example from Nishibayashi and co-workers). This transformation has been shown feasible for a number of transition metal complexes, typically following formation of a μ2-bimetallic N2 adduct that undergoes N–N bond cleavage upon addition of a reducing agent.85–90 A classic example is shown in Figure 7 and concerns a Mo tris(amido) complex, (N(R)Ar)3Mo.91,92 This species binds N2 at room temperature reversibly to form (N(R)Ar)3Mo(N2), with the μ2-N2 bridged derivative, [(N-(R)Ar)3Mo]2(μ-N2), being formed at −35 °C over a period of days. Warming this complex results in formation of two terminally bonded nitride complexes, (N(R)Ar)3Mo(N).92,93

Figure 7.

N2 splitting by a Mo tris(anilide) complex; an alternative pathway to the formation of ammonia from μ-N2 complexes.

3. SCHROCK’S TRIS(AMIDO)AMINE Mo: THE FIRST WELL-DEFINED CATALYST SYSTEM

3.1. Azatrane Mo Complexes Relevant to N2 Fixation

With an eye toward nitrogen fixation, in 1994, Kol et al. showed that triamidoamine ligands [(RNCH2CH2)3N]3− where R = C6F5 could be used to gain access to molybdenum complexes of potential relevance to N2RR (Figure 8).94 A number of relevant molybdenum complexes were accessed, including a terminal nitride (((C6F5NCH2CH2)3N)Mo(N)), methylimido cation ([((C6F5NCH2CH2)3N)Mo(NCH3)]+), as well as both bridged (((C6F5NCH2CH2)3N)Mo]2(μ-N2) and terminal ([((C6F5NCH2CH2)3N)Mo(N2)]− dinitrogen complexes. The latter of these was shown to be nucleophilic at Nβ, undergoing facile silylation by iPr3SiCl to give [(C6F5NCH2CH2)3N]Mo-N=N−Si(iPr)3. Silyl-substituted-triamidoamine ligands have also been studied (vide infra for-an example using Ti - Figure 69)—with reaction of MoCl3(THF)3 and [(Me3SiNCH2CH2)3N]Li3 giving the paramagnetic μ-N2 complex, [(Me3SiNCH2CH2)3N]Mo]2(μ-N2) in 10% yield. In 1997, O’Donoghue et al. showed that a related TMS anion, {[(TMSNCH2CH2)3N]Mo-N=N}2(Mg(THF)2) reacted with FeCl2 to give {[(TMSNCH2CH2)3N]Mo-N=N}3(μ3-Fe).95,96 These contributions laid the groundwork for further exploring azatrane-Mo complexes as competent for the binding and activation of dinitrogen, as well as the stabilization of potential N2-fixation intermediates.

Figure 8.

(Top) Reactions of a Mo triamidoamine complex having C6F5 anilido groups provided access to complexes of potential relevance to N2RR;94 (bottom) reaction of an analogous Mo complex with TMS anilido groups with FeCl2 afforded a μ3-Fe bridging via N2 to three triamidoamine Mo centers.95

Figure 69.

Synthesis and characterization data of triamidoamine-Ti complexes relevant to catalytic nitrogen fixation.55

Recognizing that TMS- and C6F5- substituted tren [(RNCH2CH2)3N]3− ligands underwent deleterious side-reactivity (due to Si−N bond cleavage and the sensitivity of C6F5 groups to nucleophilic reagents), in 2001 Greco and Schrock designed a new route to access aryl-substituted triamidoamine ligands by Buchwald—Hartwig amination.97 A small library of ligand candidates was constructed including monoaryl (C6H5, 4–F-C6H4, 2,4,6-Me3C6H3) and triaryl (3,5-Ph2C6H3, 3,5-(4-tBuC6H3)2C6H3) derivatives that could be readily metalated with Mo (Figure 9). In a subsequent contribution, Greco and Schrock illustrated that a variety of different MoIIN2 complexes could be synthesized in a reductant-dependent fashion. These aryl-substituted triamidoamine Mo complexes (RPhN3N, R = H; 4-F; 2,4,6-Me; 3,5-Ph; 3,5-(4-tBu)Ph) all feature fairly activated N2 complexes (1740 cm–1 < νNN < 1815 cm−1). Accordingly, these species could be silylated or alkylated to provide (RPhN3N)Mo(NNR) (R = SiMe3 or Me) species. The alkyl diazenidos, (RPhN3N)Mo(NNCH3), can be reacted further with alkylating agents (e.g., CH3OTf, CH3OTs) to form cationic hydrazidos [(RPhN3N)Mo(NN(CH3)2] + (Figure 9). Similarly, reaction of (RPhN3N)Mo(NNTMS) with alkylating reagents provides [(RPhN3N)Mo(NN(CH3)(TMS)]+. Efforts to access neutral molybdenum hydrazido complexes were not successful, but reduction of [(RPhN3N)Mo(NN(CH3)2]+ with NaHg amalgam, provided the Mo(Vl) nitride complex, (RPhN3N)Mo(N) (and presumably a fixed nitrogen product).98

Figure 9.

Synthesis of alkylated Mo diazenido and hydrazido complexes en route to a Mo nitride compound in a triamidoamine Mo complex with Ar = 3,5-Ph2C6H3 or 3,5-(4-tBuC6H4)2C6H3 ligands.98

To prevent undesired bimolecular pathways problematic to an N2 reduction cycle, the highly encumbering 3,5-(2,4,6-iPr3C6H2)2C6H3 (HIPT = HexaIsoPropylTerphenyl) derivative was prepared (Figure 10).70 On this ligand, an impressive suite of N2-derived monometallic molybdenum complexes were prepared (vide infra), including (HIPTN3N)Mo(N2), [(HIPTN3N)Mo(N2)] −, (HIPTN3N)Mo(NNH), and [(HIPTN3N)Mo(NNH2)]+. Additional, species potentially relevant to an N2-fixation cycle could be accessed with azide as the N atom source, (HIPTN3N)Mo(N) and (HIPTN3NMo(NH). Lastly, [(HIPTN3N)Mo(NH3)]+ was accessed by treatment of (HIPTN3N)Mo(Cl) with NH3 in the presence of NaBArF4.

Figure 10.

Synthesis of a series of monometallic molybdenum NxHy complexes on 3,5-(2,4,6-iPr3C6H2)2C6H3 (HIPT) ligated Mo; [Mo] = (HIPTN3N)Mo.70

With these species in hand, Schrock’s team explored the possibility of catalysis with soluble acid and reducing equivalents.99 Treatment of (HIPTN3N)Mo(N2) with 1.0 equiv of [LutH]BArF4 and 2.0 equiv of Cp2Co (E1/2 = −1.3 V vs Fc/Fc+) provided (HIPTN3N)Mo(NNH) nearly quantitatively (Figure 10).100 Intriguingly, (HIPTN3N)Mo(N2) reacted directly with neither [LutH]BArF4or Cp2Co, but rapidly reacted with the combination of these reagents. The Schrock group suggested that N-amido protonation could proceed reduction followed by proton transfer. This hypothesis has found indirect support from theoretical work101 and ENDOR studies. ENDOR revealed that treatment of (HIPTN3N)Mo(CO) with [LutH]+ results in protonation of an N-amido arm, but similar behavior was not confirmed for (HIPTN3N)Mo(N2) (Figure 11).102 It has been hypothesized that this reactivity profile suggests a degree of concertedness in the transfer of the proton and electron to form the new N–H bond. In this review, we will refer to such reactions as proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) reactions.103,104 Two specific suggestions have been made. Chirik and co-workers suggested that reduction of pyridinium acids by the metallocenes results in pyridinyl radicals with weak N–H bonds that could therefore mediate the conversion of (HIPTN3N)Mo(N2) to (HIPTN3N)Mo(NNH) (and potentially other N–H bond forming steps).105,106 Although such a mechanism could be operative under catalytic conditions, it is known that triethylammonium is also efficacious for this reaction in a stoichiometric fashion. The Peters group has suggested with the support of computation that instead these acids protonate the metallocene species on the Cp(*) ring resulting in species with weak C–H bonds that can then mediate conversion of the N2 species to the NNH species via a PCET reaction (vide infra).80

If a larger quantity of [LutH]BArF4 (7.0 equiv) and Cp2Co (8.2 equiv) was reacted with (HIPTN3N)Mo(N2), then [(HIPTN3N)Mo(NH3)]+ was formed in 60% yield. Furthermore, the reaction of (HIPTN3N)Mo(N) with [LutH]BArF4 (3.5 equiv) and Cp2Co (4.2 equiv) gave [(HIPTN3N)Mo(NH3)]+ in 80% yield, which could be liberated with Bu4NCl and NEt3 to afford 0.88(2) equiv of NH3. Closing the catalytic cycle involved the reduction of [(HIPTN3N)Mo- NH3]+ to (HIPTN3N)Mo(NH3), the release of NH3, and the binding of N2. However, [(HIPTN3N)Mo(NH3)]+ is quite reducing, so the reaction with Cp2Co only converted 10% of the starting material to the desired (HIPTN3N)Mo(N2) complex (Figure 11).99

3.2. Description of the System and Key Findings

Building on this work, Yandulov and Schrock published the first example of N2 reduction catalysis mediated by a well-defined, synthetic catalyst in 2003 (Figure 12).50 In particular, they observed that using the more reducing Cp*2Cr (E1/2 = −1.47 V vs Fc+/0) allowed for complete reduction of [(hIPTN3N)Mo(NH3)]+. Likewise, slow addition of reductant (6 h, syringe pump) and solvent selection (heptane) were needed to attenuate background H2 formation. With these conditions, it was found that (HIPTN3N)Mo(N2), (HIPTN3N)Mo(NNH), (HIPTN3N)Mo(N), or [(HIPTN3N)Mo(NH3)]+, when combined with Cp*2Cr (36 equiv) and [LutH]BArF4 (48 equiv), were all competent (pre)catalysts for N2 reduction, generating between 7.56 and 8.06 equiv of NH3 (Figure 12). At the time, this selectivity (~66%) was second only to nitrogenase (~75%).50

Figure 12.

Catalytic N2RR cycle depicting (HIPTN3N)Mo intermediates and their efficacy as (pre)catalysts for N2RR using [LutH]BArF4 (48 equiv) and Cp*2Cr (36 equiv); [Mo] = (HIPTN3N)Mo.50,107 Characterized compounds are shown in purple and unobserved complexes in gray.

A series of experiments were performed in order to interrogate the catalytic reaction. (HIPTN3N)Mo(NNH) was reacted with 1 equiv of [LutH]BArF4 (Figure 13).100 This was found to give a 44:56 equilibrium mixture of (HIPTN3N)Mo(NNH) and [(HIPTN3N)Mo(NNH2)]+ (Keq = 1.6). Similarly, protonation of (HIPTN3N)Mo(N) using [LutH]BArF4 gave a 3:1 mixture of (HIPTN3N)Mo(N) and [(HIPTN3N)Mo(NH)]+.100 These results suggest that weaker acids would not be suitable for the catalysis.

Figure 13.

(Top) [Mo]-NNH and [LutH]+ are in equilibrium with [Mo]-NNH2+ and Lut (Keq = 1.6); (bottom) protonation of [Mo]N gives a mixture of the starting material and [Mo]NH+, which upon reduction, decayed to give [Mo]N and [Mo]-NH2; [Mo] = (HIPTN3N)Mo.99

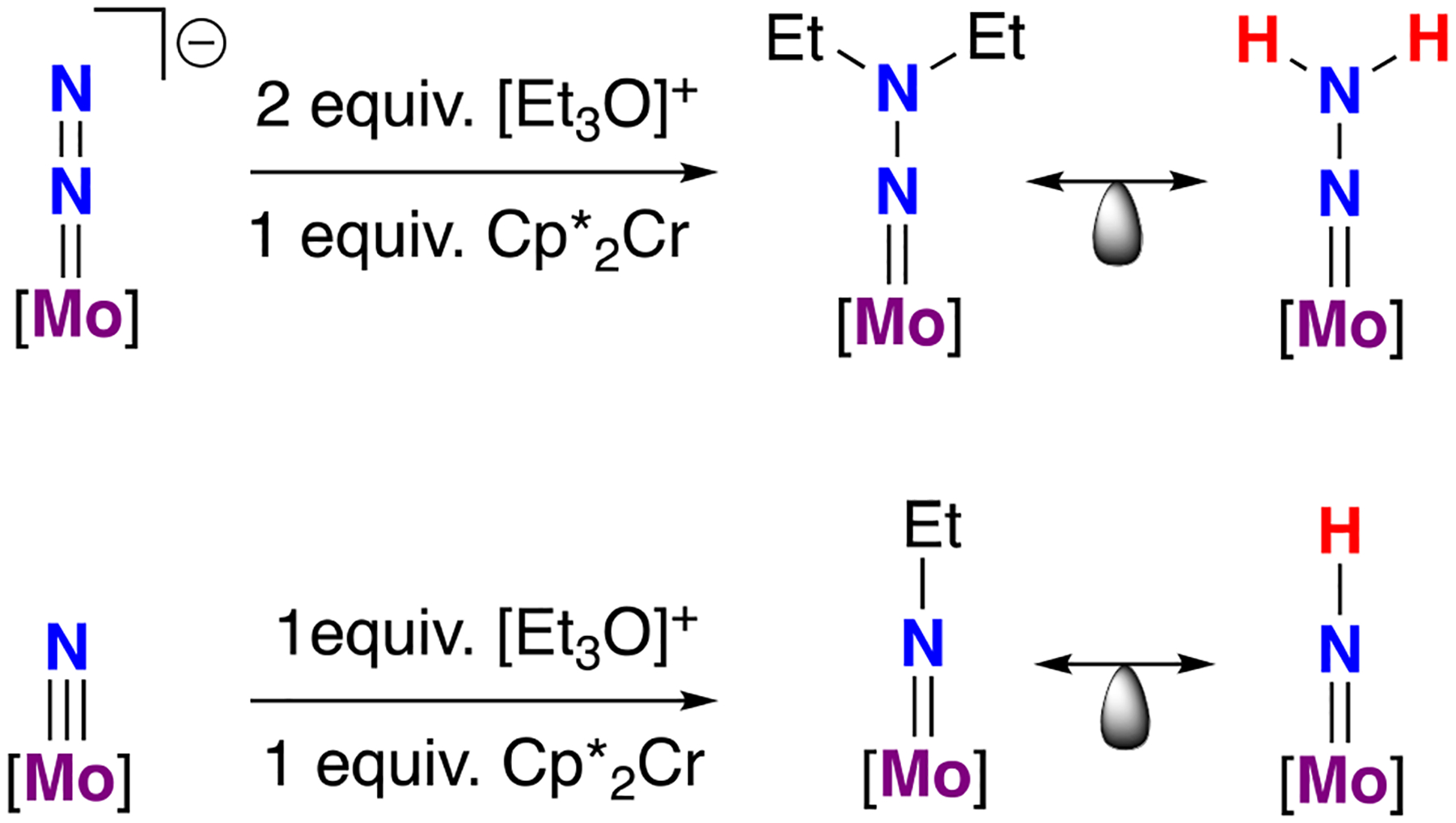

Consistent with these weak predicted bond strengths, reduction of [(HIPTN3N)Mo(NNH2)]+ by Cp2Co did not yield the expected (HIPTN3N)Mo(NNH2), but rather the formation of NH3, (HIPTN3N)Mo(NNH), and (HIPTN3N)Mo(N). Similarly, reduction of the cationic imide with Cp*2Cr initially gave a species tentatively assigned as the neutral imide, (HIPTN3N)Mo(NH), which then decayed to (HIPTN3N)Mo(N) and (HIPTN3N)Mo(NH2) in solution. These results are consistent with calculations by Chirik and co-workers that suggest that these species (the neutral hydrazido and neutral imide) have the weakest N–H bonds on this platform.106 In contrast, the alkylated congeners, (HIPTN3N)Mo(NNEt2) and (HIPTN3N)Mo(NEt), are stable, but efforts to achieve the catalytic reduction of N2 to NEt3 with [Et3O]BArF4 and Cp*2Cr were unsuccessful (Figure 14).108 While many factors may of course be at play that impede catalysis, one possible conclusion is that the net exchange of H atoms between nitrogen fixation intermediates may be relevant to achieving overall catalysis in N2RR. This is clearly speculative. Observations regarding the productive net transfer of H atoms between nitrogen fixation intermediate and the enhanced stability of alkylated congeners have been made on the silyl-anchored triphosphine system from Peters and co-workers (vide infra).109

Figure 14.

Use of an alkylating agent provided access to neutral [Mo]-NNEt2 and [Mo]-NEt; these species serve as structural analogues of the highly reactive R = H variants; [Mo] = (HIPTN3N)Mo.99,108

At the end of catalysis, [(HIPTN3N)Mo(NH3)]+ was the only Mo-containing species present, suggesting that the slow steps of the catalysis involve the reduction of this species and then exchange with N2. Consistent with this observation, the reduction potential of this species (−1.51 V vs Fc+/0 in THF) is slightly lower than that of the employed reductant, Cp*2Cr (–1.47 V vs Fc+/0 in THF).110 Exchange of N2 for NH3 in (HIPTN3N)Mo(NH3) was determined to undergo an associative mechanism on the basis of variable pressure N2 experiments (kobs = 2.4 fold faster at a 15 psi N2 overpressure). Indeed, performing N2RR at a pressure of 30 psi (instead of 15 psi) provides a small, but measurable, increase in ammonia yield (71% vs 63%) over a 6 h addition and 55% versus 45% over a 3 h addition time.110 Under catalytic conditions, dissociated NH3 is anticipated to be trapped via protonation, which should drive the reaction toward the N2 complex. Consistent with this, the rate of the substitution reaction was significantly enhanced by inclusion of triphenylborane as an NH3 trap.110 Computational studies by Reiher and co-workers have found support for the involvement of a six-coordinate (HIPTN3N)Mo(NH3)(N2) intermediate (as opposed to a five-coordinate species with a dissociated ligand arm) in the exchange process.101,111 Accessing states where there is rapid exchange of NH3 for N2 remains a general challenge for N2RR catalysts and accordingly is an ideal area for future catalyst design.

Schrock and co-workers performed X-ray diffraction analysis on (HIPTN3N)Mo(NNH), [(HIPTN3N)Mo(NNH2)]+, [(HIPTN3N)Mo(NH)]+, and [(HIPTN3N)Mo(NH3).100 The accumulated structural data show that the Mo–Namine distance varies as a function of the Mo axial ligand; as the N–N bond is weakened and cleaved on going from [HIPTN3N]Mo(N2) to [HIPTN3N]Mo(N), a lengthening in the Mo–Namine by ~0.19 Å is observed. An even more dramatic lengthening of the metal-axial ligand distance has been observed in the borane-anchored trisphosphine Fe system from Peters and co-workers.112–114 This suggests that flexibility of this interaction is perhaps critical for allowing catalysts to stabilize both π-accepting intermediates and π-donating intermediates and/or low-valent and high-valent states.

Given the formation of H2, presumably from Mo(H) species, during (HIPTN3N)Mo catalyzed nitrogen fixation, the reactivity of Mo(H) and Mo(H2) complexes was also of interest.99,107 Intriguingly, (HIPTN3N)Mo(H) could be prepared from the diazenido derivative, (HIPTN3N) Mo(NNH), via an effective “β-H elimination” (k1 = 2.2 × 10−6 s−1) (Figure 15). This is a very unusual transformation that potentially warrants further study. The use of the hydride species as a (pre)catalyst produced 7.65(3) equiv of NH3, suggesting that it could be readily returned to a catalytically on-path intermediate. Schrock and co-workers demonstrated that reaction of (HIPTN3N)Mo(H) with [LutH]BArF4 led to the formation of [(HIPTN3N)Mo(Lut)]+, which can presumably be reduced and bind N2 to rejoin the catalytic cycle. The performance of the (HIPTN3N)Mo(H) species as a precatalyst contrasts with that of other M(H) (M = Fe, Co, Os) species. In those cases, the M(H) species have uniformly performed more poorly as precatalysts than the related N2 complex (vide infra).53,54,115,116

Figure 15.

β-H elimination from the diazenido derivative, [Mo]–NNH, generated [Mo]–H; [Mo] = (HIPTN3N)Mo.99

The H2 complex, (HIPTN3N)Mo(H2), could be formed via the reaction of (HIPTN3N)Mo(N2) with H2 over 2–3 days (Figure 16).107 Exchange of N2 for H2 occurred at a rate of k = 3.4 × 10−6 s−1 and was independent of the H2 pressure, indicating a rate-limiting dissociation of N2 prior to H2 coordination, consistent with the proposed dissociative exchange of N2 and 15N2.99 Experiments for the reverse reaction (i.e., formation of (HIPTN3N)Mo(N2) from (HIPTN3N)Mo(H2) found the rate to be 1.0 × 10−6 s−1 (t1/2 = 8 days)). Use of (HIPTN3N)Mo(H2) as a (pre)catalyst provided ammonia in 52% yield relative to 60–65% (from (HIPTN3N)Mo(N2)). Experiments carried out with dihydrogen injected (~32 equiv and 64 equiv of H2 with respect to Mo) using (HIPTN3N)Mo(N) as the catalyst, showed that only 1 equiv of NH3 was formed, presumably from the nitride ligand.107 Cumulatively, these data suggest that H2 poisons the N2 fixation catalysis. This presents a significant challenge to achieving higher turnover numbers with this catalyst. Indeed, the ability to manage H2 formation is ultimately going to be an issue of concern in any catalytic nitrogen fixation system that is not perfectly selective for NH3.

Figure 16.

Generation of [Mo]–H2 and a plausible decay pathway involving intramolecular deprotonation to a terminal (HIPTN3NH)Mo(H) species; [Mo] = (HIPTN3N)Mo.107

3.3. Use of EPR for the Study of (HIPTN3N)Mo Complexes

Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) and electron nuclear double resonance (ENDOR) have enabled the characterization of a number of (HIPTN3N)Mo complexes. These have included (HIPTN3N)Mo(NH3),117 (HIPTN3N)Mo(N2),102,117–119 (hIPTN3N)Mo(CO),102,117 the amido-protonated analogue, [(HIPTN3N(H))Mo(CO)]+102 (vide supra) as well as the product of H2 with (HIPTN3N)Mo(N2), the Mo(III) anion, [(HIPTN3N)Mo(H)]−.119 More recently, Schrock, Hoffman, and Neese studied the electronic and geometric structures of [(HIPTN3N)Mo(N)]–-and (HIPTN3N)Mo(NH) by irradiation of their oxidized congeners with γ-rays at 77 K.120 Collectively, these studies serve to provide useful spectroscopic models to which more complicated [Mo]-containing clusters can be compared; several of these open-shell compounds are not characterizable by other means.

3.4. Evidence in Support of the Chatt/Schrock Cycle from Theory

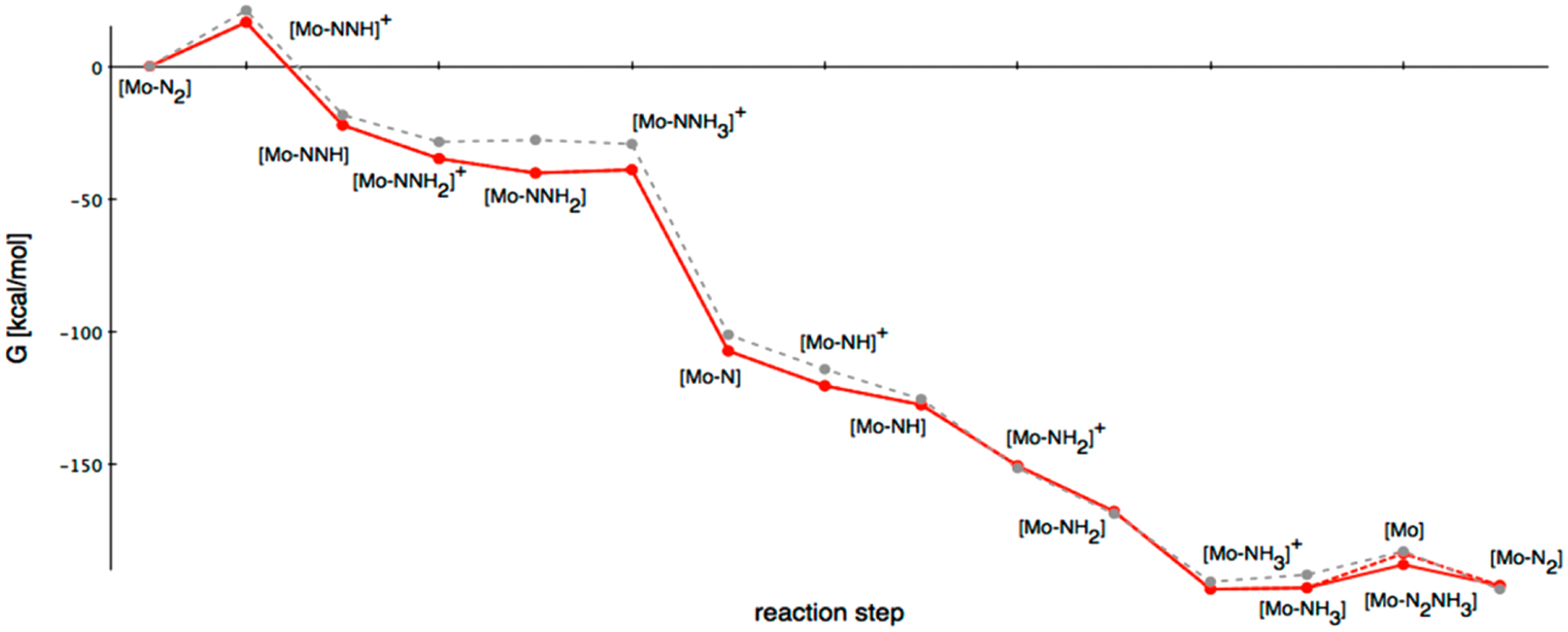

Several studies that bear on the theoretical mechanism of N2 fixation by the (HIPTN3N)Mo system have been published (Figure 17),101,121–127 and in 2008, theoretical and experimental data for this system were compared by Schrock.128 A brief summary is provided here. Early theoretical studies tended to simplify the catalyst structure to reduce computational expense. For example, Morokuma129 and Cao126 performed studies on truncated models that were not referenced to the catalytically relevant acid and reductant sources. In 2005, Tuczek and co-workers reinvestigated the complete cycle, modeling the HIPT portion of the ligand as hydrogen but using the relevant acid, [LutH]+ and reductant, Cp*2Cr sources as energetic references.121 Independently, Reiher101,122 and Neese & Tuczek124 later performed a series of DFT calculations taking the entire HIPT ligand moiety into account, requiring models of ~280 atoms. In broad terms, these data corroborated the cycle reported above (Figure 12). The following key points are recapitulated with numerical values taken from Nees and Tuczek (B3LYP/def2-TZVP)124—this study also summarized and compared its findings with those from other studies.

Figure 17.

Reproduced with permission from ref 124. Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society. Red: Gibbs free enthalpy ΔG° scheme of the Schrock cycle calculated with the B3LYP functional and the def2-TZVP basis set including solvent correction. Gray: calculations by Studt et al.121

Importantly, all on path intermediates were predicted to be neutral or positively charged; the formation of negatively charged intermediates are predicted to be highly unlikely.

Protonation of (HIPTN3N)Mo(N2) was calculated to be the most endergonic reaction step of the reaction (ΔG = +16.6 kcal mol−1) with protonation of an N-amido ligand arm being more favorable; this species has been characterized spectroscopically for (HIPTN3N)Mo(CO).102 Subsequent reduction, followed by protonation, was proposed to yield [(HIPTN3NH)Mo(NNH)]+. Later computational work from the Chirik group and Peters group have proposed PCET pathways to form the diazenido complex directly from (HIPTN3NH)Mo(N2) as a plausible first step in the catalysis.80,105,106

The most exergonic step of the reaction was N–N bond cleavage upon reduction of [(HIPTN3N)Mo(NNH3)]+ (ΔG = −68.4 kcal·mol−1).124

Consistent with experiment, reduction of the ammine cation, [(HIPTN3N)Mo(NH3)]+ to the neutral species by Cp*2Cr was essentially thermoneutral (ΔGcalc = +0.5 kcal·mol−1, ΔGexp = +0.9 kcal·mol−1).124

The dissociation of NH3 from (HIPTN3N)Mo(NH3) is endergonic (ΔG = +13.0 kcal·mol−1). Subsequent N2 coordination was exergonic (ΔG = −12.1 kcal·mol−1), rendering the net exchange slightly uphill (ΔG = +0.9 kcal·mol−1).124 This calculation agrees with the observed Keq value of 0.1 for this reaction, which corresponds to ΔG = +1.1 kcal·mol−1.124 An associative mechanism was also considered for this process, with calculation of the putative, six-coordinate (HIPTN3N)Mo(NH3)(N2) species being +8.8 kcal·mol−1 higher in energy than (HIPTN3N)Mo(NH3) and free N2.124

A necessary shortcoming of these (and most) DFT studies is that they cannot consider all of the species/interactions that might be relevant in the catalytic mixture. Hence, their primary value lies in their ability to shed light on specific questions given certain assumptions. So as to explore secondary interactions that might be relevant to the Schrock system, Reiher et al. studied “one-pot” models (where acid (acid = [LutH]+) and base (base = a Mo compound) were initially placed approximately 8 Å from one another). This study predicted hydrogen bonded complexes between (HIPTN3N)Mo(N) or (HIPTN3N)Mo(N2) and [LutH]+, indicating that the acid source is sufficiently small to approach the basic part of the molecule through voids made by the three HIPT ligands.122 A related hydrogen-bonded complex between [LutH]+ and a Mo(N) species in a different N2-fixation relevant complex (vide infra) was crystallographically characterized by Schrock and co-workers in 2019 (Figure 18).130 That complex underwent net PCET on treatment with reductant. These collective data support the possibility that a multisite PCET reaction could be relevant to diazenido formation in the (HIPTN3N)Mo system. In this proposal, a hydrogen bonded [(HIPTN3N)Mo(N2)—LutH]+ complex would transfer the proton only upon electron transfer from Cp*2Cr (Figure 17).

Figure 18.

(Left) A depiction of a hydrogen bonded complex between (HIPTN3N)Mo(N2) and [LutH]+ identified in a “one-pot” calculation;122 (right) a depiction of a crystallographically characterized hydrogen bonded complex between (Ar2N3)Mo(N) (Ar = 2,6-diisopropylphenyl) and [LutH]+.130

3.5. Second Generation Schrock Systems

Despite extensive efforts invested in improving the TON of the original (HIPTN3N)Mo system, reactivity (e.g., protonolysis) of the Mo-amido linkages and ligand exchange appears to plague it and related systems. These efforts are summarized here. By 2004, three new ligand variants appeared: two of which gauged sterics (tBu and CH3 in place of iPr) and one that gauged electronics (Br in place of H at the para position of the middle terphenyl ring) (Figure 19). For each ligand, the Mo(N) complex was prepared and its efficacy for catalytic N2RR was tested. The t-butyl analogue produced only 1.06 equiv of NH3 using Cp*2Cr (36 equiv) and [LutH]BArF4 (48 equiv), while the methyl analogue gave only 1.49 equiv of NH3. The p-Br analogue provided 6.4–7.0 equiv of NH3, slightly less than the standard HIPT-based Mo catalyst system.131

Figure 19.

A survey of second generation complexes tested for N2RR by Schrock and co-workers. Reported yields were found using the optimized conditions for the original catalytic result: [LutH]+ (48 equiv), Cp*2Cr (36 equiv), heptane, room temperature.131–134

In another iteration of ligand design, asymmetrical tren ligands were prepared in which one of the three HIPT groups was replaced by (1) a 3,5-disubstitutedbenzene-3,5-Me2C6H3, 3,5-(CF3)2C6H3, or 3,5-(MeO)2C6H3; (2) a 3,5-disubstituted-pyridine-3,5-Me2NC5H3 or −3,5-Ph2NC5H3 or (3) a 2,4,6-trisubstitutedbenzene-2,4,6-Me3C6H2 or −2,4,6-iPr3C6H2 (Figure 19).132 For each ligand, the Mo(N) complex was prepared and probed for competency in catalyzing N2RR. For these candidates, 0.2–2.0 equiv of NH3 was found.

In 2010, Chin and Schrock outlined the synthesis of a system comprising pyrrolide rather than anilide donor groups, which were pursued in hopes of attenuating undesired aminolysis in the presence of acid (a limitation of the HIPT system) (Figure 19).133 Diamido(2-mesityl)pyrrolyl complexes of the type ((ArN)2Pyr)Mo(X) (Ar = C6F5, 3,5-Me2C6H3, or 3,5-tBu2C6H3, X = Cl or NMe2), having two amide and one pyrrole group were prepared. The degree of N2 activation was attenuated in [((ArtBuN2)Pyr)]Mo(N2)]− (νNN = 2012 cm−1 vs 1990 cm−1 [(HIPTN3n)Mo(N2)]−). Perhaps relatedly, ((ArtBuN2)Pyr)Mo(N) proved to be a much poorer catalyst for N2RR (1.02 ± 0.12 equiv of NH3) with no evidence for N2 uptake during catalysis.

In a subsequent study, Reithofer and Schrock developed a HIPT derivative incorporating pendant nitrogens (2,5-diiso-propylpyrrolyl, DPPN3N) in the secondary coordination sphere (Figure 19).134 The hypothesis was that if (HIPTN3N)Mo undergoes decomposition by competitive protonation at the Mo–Namide bond, then providing Brønsted basic groups in the secondary coordination would prevent that and allow a greater population of catalyst to remain on-cycle. In this vein, (DPPN3N)Mo(Cl), (DPPN3N)Mo(N2), and [(DPPN3N)Mo(N2)]− precursors were prepared similarly to those for the HIPT system (vide supra). For (DPPN3N)Mo(N2), υnn = 1993 cm−1, indicating a similar degree ofactivation when compared to (HIPTN3N)Mo(N2). Of the Schrock Mo(N2) compounds discussed in this review, this is the only one that undergoes associative N2 substitution. In a standard experiment, treatment of (DPPN3N)Mo(14N2) with 15N2 showed a first order dependence on [15N2]. This conclusion is rationalized by virtue of having a smaller five-membered pyrrole-based ligand platform that allows for associative substitution, cf. a bulkier six-membered 3,5-substituted terphenyl-group. Other species, including (DPPN3N)Mo(NNH), [(DPPN3N)Mo(NNH2)]+, (DPPN3N)Mo(N), [(DPPN3N)Mo(NH)]+, and [(DPPN3N)Mo(NH3)]+, were also prepared. Efforts toward N2 reduction using (DPPN3N)Mo(N) as the (pre)catalyst produced 2.53 ± 0.35 equiv of NH3 making it formally catalytic.

In 2018, Wickramasinghe and Schrock again endeavored to maintain catalyst efficiency by limiting Mo–Namide protonation or dissociation (Figure 20). In this effort, they synthesized a calix[6]azacryptand ligand (CAC(OMe)3) that tethered the three HIPT triamidoamine ligand arms together.135 The X-ray structure of the nitride complex, (CAC(OMe)3)Mo(N), confirmed that the three-amido arms were locked in the desired configuration. Unfortunately, this system was not active for catalytic N2 fixation, producing only 1.28 equiv of NH3 using [Ph2NH2]OTf (96 equiv) and KC8 (84 equiv). The yield under the standard conditions used for (HIPTN3N)Mo were not reported.

Figure 20.

A calix[6]azacryptand ligand designed by the Schrock group aimed at protecting the reactive Mo active site for use in N2RR.135

3.6. Schrock Work on W, Cr, and V

The Schrock group explored the (HIPTN3N)M platforms (M = W, Cr, and V) for catalytic N2RR, but without success.136–138 In the case of tungsten, the preparative chemistry was found to be very similar to that for Mo (vide supra), with many candidate intermediates of N2RR being readily synthesized (Figure 21). However, attempts to demonstrate catalytic nitrogen fixation resulted in only stoichiometric yields of NH3 (1.3–1.5 equiv). The authors attributed the inability of the (HIPTN3N)W system to serve as an N2RR catalyst to a problematic redox couple for the ammonia adduct: [(HIPTN3N)W(NH3)]+/0.136 It is much harder to reduce this species than its Mo analogue (−2.06 V vs Fc+/0 compared to −1.63 V vs Fc+/0).100 Furthermore, chemical reduction does not lead to the neutral ammonia or N2 adduct hinting at undesired side reactivity.84

Figure 21.

Synthesis of candidate NxHy intermediates on (HIPTN3N) W relevant to N2 fixation. Note: this system produces only stoichiometric yields of NH3 (1.3−1.5 equiv).136

In the case of Cr, (HIPTN3N) complexes of both CrIII and CrII proved unable to bind N2. This contrasts directly with the behavior of the Mo and W complexes, which readily form dinitrogen complexes at these redox states, but is consistent with the lack of known CrII or CrIII dinitrogen complexes. The authors speculate that the relatively slow binding of CO to the HIPTN3N-complexes of CrII and CrIII compared to that observed for Mo and W could be due to the high-spin nature of the Cr centers. The nitride complex, (HIPTN3N)Cr(N), was prepared via thermolysis of the corresponding azide complex (Figure 22). Reductive protonation of this species under their standard catalytic conditions led to the formation of 0.8 equiv of NH3. This result suggests that downstream reduction steps are viable for (HIPTN3N)Cr, but presumably the lack of N2 uptake short-circuits viable catalysis.137

Figure 22.

Synthesis of (HIPTN3N)Cr(N) and (HIPTN3N)V(NH) and their reductive protonation to give 0.8 and 0.76 equiv of NH3, respectively. These results demonstrate that catalytic N2RR is not accessible with these species, but downstream functionalization reactions are productive.137,138

To compare V, the complex (HIPTN3N)V(THF) was prepared. Dinitrogen binding was only observed upon reduction to the anionic state, [(HIPTN3N)V(N2)]−, which required the use of KC8 (as opposed to Cp*2Cr). Attempts to use the latter as a precatalyst for nitrogen fixation under the standard Schrock-type conditions were unsuccessful (0.2 equiv of NH3). The (HIPTN3N)V(NH) complex could be prepared either via reaction of the V(THF) species with methylaziridine (Figure 22) or via reaction of the V(NH3) with base and oxidant. Its use as a precatalyst led to the formation of 0.78 equiv of NH3 akin to results obtained with (HIPTN3N)Cr(N) discussed above. This again points to the challenge of N2-uptake, at least using the original catalytic conditions with Cp*2Cr as the reductant.138 A computational study of this system posited several reasons to explain its inefficiency. In particular, the study pointed to the lower basicity of the various N2-fixation intermediates which might lead to increased preference for ligand protonation, the lesser thermodynamic driving force for N–N bond cleavage, and the persistent challenge of exchanging NH3 for N2.139

3.7. Third Generation Schrock Systems (Tridentate Platforms)

Recently, Schrock and co-workers have exploited a geometrically distinct, diamido(pyridine) pincer framework for Mo catalyzed N2 fixation (Figure 22).140 In 2017, they reported that the diamido(pyridine) ligand, [2,6-(ArNCH2)2NC5H3]2− (Ar2N3, Ar = 2,6-diisopropylphenyl), can be used to prepare (Ar2N3)Mo(N)(OtBu). Reaction of this nitride with 108 equiv of [Ph2NH2]OTf and 54 equiv of Cp*2Co (conditions discovered in the context of Fe-catalyzed N2RR, (vide infra) gave 7.9 equiv of NH3. By contrast, [Ar2N3]Mo(N)(OC6F5) was not competent for catalysis (1.3 equiv of NH3 under same conditions). The authors suggested that the tBuO fragment in the more active species might be more readily converted to a Mo–OH or Mo(O) unit, which is the catalytically active species.

A series of stoichiometric experiments were performed to shed light on the mechanism by which (Ar2N3)Mo(N)(OtBu) facilitates N2RR (Figure 24). Reaction of this species with the relevant acid, [H2NPh2]OTf, was found to protonate a ligand Mo-N amido linkage. By contrast, use of the weaker/bulkier (and catalytically ineffective) acid, [LutH]OTf, was found to provide an adduct species via a hydrogen-bond to the nitride (vide supra).130 Treatment of either of these species with Cp2Co resulted in the reformation of (Ar2N3)Mo(N)(OtBu), presumably via the loss of a half-equivalent of H2, though this was not confirmed. The authors speculated that this reaction pointed to the possibility of PCET reactivity during N2RR, but this has not been confirmed.

Figure 24.

Reaction of (Ar2N3)Mo(N)(OtBu) with [H2NPh2]+ results in protonation of a Mo-Nanilido arm whose product is shown to the right and use of [LutH]+ results in hydrogen-bond formation with the nitride shown on the left. Following reduction, each of these complexes releases H2 to provide the starting material shown in the center.130

4. NISHIBAYASHI’S LOW-VALENT Mo-PHOSPHINE SYSTEMS

4.1. Description of the Original System and Key Findings

In 2010, Nishibayashi and co-workers introduced a dinuclear molybdenum system as an N2 fixation (pre)catalyst (Figure 25).51 Specifically, a PNP-based (PNP = 2,6-bis(di-tert-butyl-phosphinomethyl)pyridine) complex (PNP)MoCl3 was prepared and reduced to the corresponding dinitrogen Mo(0) complex, [(PNP)Mo(N2)2]2(μ-N2), through reaction with NaHg amalgam (terminal υNN= 1936 cm−1). Use of adamantly-or isopropyl-substitutents in lieu of the tert-butyl groups did not provide the analogous Mo(0) complexes, highlighting the critical role of P-substituent. In a trial experiment, N2 reduction was assayed using [LutH]OTf (96 equiv) and Cp2Co (72 equiv) as proton and electron sources, in toluene at room temperature. Notably, a solution of the reductant was added slowly over the course of the reaction by syringe pump to prevent rapid recombination of electron and proton sources. Altogether, this mixture produced 11.8 equiv of NH3 (6.9 equiv of per Mo); using larger quantities of acid and reductant (266 equiv and 288 equiv, respectively) produced 23.2 equiv of NH3 (11.6 equiv per Mo center). Similar activity was found using Cp*2Cr, though use of less reducing Cp2Cr produced no NH3. The optimal acid was found to be [LutH]OTf, with Cl− and BArF4− counteranions providing significantly less NH3 (0.7 and 2.7 equiv, respectively). Other Mo complexes, such as cis-Mo(Me2Ph)4(N2) and trans-Mo(N2)(dppe)2 (dppe = 1,2-bis(diphenylphosphino)-ethane), give only stoichiometric quantities of NH3. To probe catalytic intermediates, [(PNP)Mo(N2)2]2(μ-N2) was treated with [HOEt2]BF4 in pyridine, providing the cationic hydrazido adduct, [(PNP)Mo(N-NH2)(F)(pyr)]BF4 (pyr = pyridine, Figure 25). Early on, the authors posited that this reaction proceeds through a mononuclear Mo complex, invoking a series of six stepwise proton and electron transfers, though this hypothesis was later subjected to refinement (vide infra). Notwithstanding, in 2011, this represented the most active catalytic method of accessing NH3 directly from N2 using soluble acid and reducing equivalents with a molecular species.

Figure 25.

Nishibayashi’s first generation, [(PNP)Mo(N2)2]2}(μ-N2) N2RR catalyst. In these reactions, Cp2Co was added via syringe pump and the acid counterion had a marked effect on the performance. Protonation of [(PNP)Mo(N2)2]2}(μ-N2) using [HOEt2]BF4 provided a hydrazido(2−) Mo complex.51

Further studies were performed using phosphine adducts of the aforementioned PNP-pincer complexes.141 In a follow-up contribution, Arashiba et al. showed that reduction of the corresponding (PNP)MoCl3 precursors with NaHg amalgam in the presence of PMe2R (R = Me or Ph) provided (PNP)Mo(N2)2(PMe2R) (Figure 26). Initial protonation studies using excess sulfuric acid (H2SO4) revealed that these derivatives produced 1.38 and 0.85 equiv of NH3, respectively. Under catalytic conditions, the PMe2Ph derivative produced only a small amount of NH3 (0.2 equiv).

Figure 26.

Protonation studies of six-coordinate (PNP)Mo(N2)2(PMe2R) complexes gave 1.38 (R = Me) and 0.85 (R = Ph) equiv of NH3.141

Examination of phosphine R group also provided information into the nature of PNP coordination mode (Figure 27).141 In this way, a variety of unsymmetrical PNP-based ligands were prepared, featuring R = tBu groups positioned on one phosphine arm and one of R′ = Ad, tBu, iPr, or Cy on the other. In all cases, the corresponding (PNP)MoCl3 precursors were accessed and reduced under standard NaHg amalgam conditions, giving binuclear [Mo] complexes having one of two geometries. In the first, the two terminal N2 units remain characteristically trans-disposed (R = tBu, R′ = Ad or Ph) and in the second, the two terminal N2 groups are mixed; both -trans and -cis geometries were found; both geometries feature a bridging N2 unit. Subjecting the four of these catalysts to a solution of [LutH]OTf (96 equiv) and addition of Cp2Co (72 equiv) via syringe pump over 1 h produces between 1 and 14 equiv of NH3/Mo center—the greatest yields were observed for the catalyst containing R′ = tBu or Ad groups. Naturally, the phosphine R groups have a profound influence on downstream Mo(NxHy) adducts, causing either enhanced or decreased activity. This work highlights the subtle nuances of ligand design and shows that larger R groups are more adept at protecting the reactive Mo core.

Figure 27.

Modification of ligand phosphine substituent gave different Mo2(μ-N2) isomers. For R = tBu, R′ = Ad or Ph, trans-/trans- is observed, while for R = tBu, R′ = iPr or Cy, trans-/cis-is observed. The R = tBu, R′ = Ad substituted phosphine provides the highest yield of NH3 (14 equiv) during N2RR.141

In an effort to develop catalytic N2RR using N2 and H2 under mild reaction conditions, the Nishibayashi group studied the reactivity of high-valent molybdenum complexes with hydride reagents to generate on-cycle catalytic dinitrogen complexes (Figure 28).142 For this reason, Arashiba et al. showed that reduction of [PNP]MoCl3 (R = tBu) with KC8 produces a μ-N2 bridged dimolybdenum precursor, {[PNP]Mo(Cl)2]2}(μ-N2) (Figure 27). Treatment of this precursor with KHBEt3 results in formation of the dinitrogen complex, {[PNP]Mo(N2)2]2}(μ-N2) as well as 2 equiv of H2. Reaction of {[PNP]Mo(Cl)2]2}(μ-N2) with excess H2SO4 provides no reduced nitrogen-based products (cf. 0.6 equiv of NH3, 0.06 equiv of N2H4 for {[PNP]Mo(N2)2]2}(μ-N2)). This reaction demonstrates that high-valent [Mo]-halide bonds can be cleaved by way of hydride reagents, allowing for access to on-path [Mo]-N2 complexes by way of H2 elimination.

Figure 28.

On-cycle (PNP)Mo(N2) complexes can be generated through H2 evolution from their respective halide precursors.142

In 2013, a modified ligand was reported where the ligand pincer phosphine donors were changed to arsine, a donor featuring a larger element of poorer σ-donating/π-accepting ability (Figure 29).143 The ANA pincer ligand was prepared and coordinated to molybdenum; reduction of this precursor provided a cis-/trans-N2 dimolybdenum complex having υNN = 1904 cm−1 for the μ-N2 ligand (cf. υNN = 1890 cm−1 for the PNP analogue, {[PNP]Mo(N2)2]2}(μ-N2) R = tBu). In the presence of PMe3, a phosphine complex, [ANA]Mo(N2)2PMe3 was isolated. Despite producing similar amounts of NH3 (cf. the PNP system) when exposed to excess H2SO4 (ca. 0.6 equiv of NH3), catalysis was nonproductive using {[ANA]Mo(N2)2]2}-(μ-N2) R = tBu) and varying equivalents of Cp2Co and [LutH]OTf, producing only 2 equiv of NH3. This data point contrasts with the PNP-based system where 12 equiv of NH3 was observed under similar conditions. The previously formed unsymmetrical phosphine complexes that contained trans-/cis-N2 units were also ineffective for catalysis (R = tBu, R′ = iPr (3 equiv of NH3), Cy (1 equiv of NH3)).

Figure 29.

Arsine analogues of the PNP class of ligands have been prepared, though Mo complexes of these ligands are not active for catalytic N2RR under the conditions shown.143

4.2. Mechanistic Conclusions That Can Be Drawn and Uncertainties

Next, the effect of substitution at the 4-position of such PNP ligands having PtBu2 groups was explored (Figure 30).82 The installation of both electron-donating and -withdrawing groups was carried out, with the hypothesis that electron-donating groups would increase N2 activation and thus accelerate Nβ protonation. From this design perspective, five candidate [(4-XPNP)Mo(N2)2]2(μ-N2) complexes were prepared having X = Ph, Me3Si, tBu, Me, and OMe groups at the 4-position. Structurally, no distinct differences were observed from the parent (X = H) system. As judged by IR spectroscopy, substitution of more electron-donating groups provides a more activated N2 entity (υNN = 1932 cm−1 for X = OMe vs 1944 cm−1 for X = H). All of these species are catalytically active for NH3 formation, resulting in 28 and 31 equiv of NH3 for the tBu- and Me-substituted PNP ligands, respectively, using 216 equiv of Cp2Co and 288 equiv of [LutH]OTf. The greatest amount of NH3 is formed when R = OMe (34 equiv) under the same conditions.

Figure 30.

Ligand modifications have been targeted by changing the ligand 4-X group. The reaction scheme depicts the first three steps relevant to catalytic N2RR as calculated by DFT (1) Nβ protonation, (2) N2 dissociation, and (3) triflate coordination.82

The study of N2 reduction catalysis using density functional theory provided insight into the high barrier by which initial Nβ protonation occurs (Figure 30). This process involves three steps, (1) protonation to give a Mo diazenido, Mo(NNH), followed by (2) displacement of the trans-N2 ligand, and (3) attack of a triflate (OTF−) unit—the final two steps offsetting the high endothermicity of the first. In terms of phosphine R group, installation of tBu best stabilizes the protonated diazenido intermediate and was found to have the lowest energy pathway. Substitution of an electron-donating group at the PNP 4-position is also thought to accelerate Nβ protonation due to N2 activation.

To test the importance of reductant concentration on the catalytic behavior of the 4-OMe catalyst, Cp2Co was added over a longer period of time (5 h vs 1 h) and gave a greater amount of NH3 (36 equiv), suggesting a longer catalyst lifetime. Increasing the amount of acid ([LutH]OTf: 480 equiv) and reductant (Cp2Co: 360 equiv) provides 52 equiv of NH3. In terms of reductant and acid optimization, it was found that Cp*2Cr has a negligible effect on reaction outcome, while use of [4-ClLutH]OTf (pKa = 5.46 in H2O) provides only a stoichiometric amount of NH3. Use of a weaker acid, [4-CH3LutH]OTf (pKa = 7.55 in H2O) gives only 10 equiv of NH3. Given the highly active nature of the 4-OMe catalyst, mechanistic studies comparing the 4-OMePNP catalyst and the parent PNP catalyst were carried out. From these, it was determined that when X = H the reaction is first order in Mo, while when X = OMe the reaction is zeroth order in Mo, suggesting different rate-determining steps (the reaction order with respect to reductant was found to be first order in both cases). At present, it is unclear how such a mechanism can be zeroth order in Mo. Dihydrogen yields were also measured, showing that X = OMe not only produces the highest quantity of NH3, but also the lowest quantity of H2. Performing the reaction under a partial H2 atmosphere also results in lower activity for NH3 formation for the 4-OMe catalyst (96:4 N2/H2 — 23 equiv of NH3), indicating that H2 inhibits NH3 formation—a conclusion that has been drawn for other synthetic nitrogenases (N2ases).107 Overall, substitution at the 4-position of the PNP ligand was found to have a marked effect on N2 reduction selectivity, allowing for rate enhancement of the first protonation event and suppression of molecular hydrogen formation.

In 2014, Tanaka et al. explored the use of mononuclear molybdenum nitrides for catalytic N2RR (Figure 31).83 Treatment of Mo(Cl)3(THF)3 with Me3SiN3 at 50 °C for 1 h, followed by addition of the PNP ligand, gave (PNP)Mo(N)-(Cl)2, which served as a synthetic precursor to related species including (PNP)Mo(N)(Cl), [(PNP)Mo(N)(Cl)]OTf, and [(PNP)Mo(NH)(pyr)(Cl)]OTf (pyr = pyridine). Of these compounds, only (PNP)Mo(N)(Cl) and the oxidized product, [(PNP)Mo(N)(Cl)]OTf, exhibited catalytic efficacy (6.6 and 7.1 equiv of NH3).

Figure 31.

Mononuclear PNP-ligated molybdenum nitrides are active for catalytic N2 fixation using [LutH]+ (48 equiv) and Cp2Co (36 equiv).83

In view of this result, DFT calculations were performed to assess the relevancy of [(PNP)Mo(N)]OTf or related complexes to the observed catalysis83 (Figure 32). The initial pathway was calculated to be similar to that outlined above (Figure 30), with a dinuclear molybdenum complex being protonated initially, and then breaking up upon a third (reductive) protonation step to liberate NH3 and a terminal nitride product, [(PNP)Mo(N)]OTf. The latter is a competent precatalyst, and, following a series of reductive protonation steps, (PNP)Mo(NH3) is generated and combines with (PNP)Mo(N2)3 to regenerate a μ-bridged N2 complex; NH3 can be replaced by N2 in this species to restart the catalytic cycle. (PNP)Mo(N2)3 itself is not thought to be catalytically competent. Instead, the authors suggest that the terminal N2 ligand that undergoes monoprotonation (the first step of the cycle) must be that of a dimolybdenum complex, with electron transfer from an adjacent Mo center preactivating the Mo(N2) fragment. This is an interesting hypothesis that provides an opportunity for future experimental studies.

Figure 32.

Complete calculated N2RR cycle for Nishibayashi’s dinuclear Mo2 complexes. [Mo] = (PNP)Mo(N2)3.83

Redox-active subunits have also been incorporated within the PNP ligand framework by the Nishibayashi group to canvass possible advantages of placing a redox relay close to the catalytic active site (Figure 33).144 The direct incorporation of metallocene subunits such as ferrocene and ruthenocene, in the trans-/trans-N2 (PNP)dimolybdenum framework, was found to have a negligible effect on the degree of N2 activation as judged by IR spectroscopy; derivatives featuring ethylene or phenylene linkers to the metallocene subunits also showed similar activation. Cyclic voltammetry revealed marked shifts in the E1/2 associated with the Fe(II/III) couple compared to free ferrocene, consistent with electronic communication between Fe and Mo; spectroelectrochemistry demonstrated low energy transitions in the near-IR at around 800–1800 nm, consistent with Fe-to-Mo charge transfer (MMCT). The degree of electronic communication was weaker when a linking (ethylene or phenylene) group was present.

Figure 33.

A survey of Nishibayashi’s Mo complexes for catalytic N2RR Fc = ferrocene, EtFc = ethylferrocene.83,84,144–146

In terms of catalysis, it was found that the ferrocene-appended catalyst gave 37 equiv of NH3, compared with 23 equiv of NH3 under the same conditions where X = H (Figure 33). Control experiments employing the X = H parent catalyst in the presence of exogenously added ferrocene gave only 21 equiv of NH3, suggesting that inclusion of the redox-active subunit may have some benefit. From a DFT study, one step that was suggested to be dramatically affected by inclusion of a metallocene within the catalyst framework concerns reduction of the hydrazidium, [Mo(NNH3)]+, complex, enabling release NH3 and Mo(N). Azaferrocene-based PNP Mo complexes have also been employed to survey their efficacy for catalytic N2 fixation, but they were not successful under the conditions explored.145

PNN-based Mo complexes have also been studied by Nishibayashi and co-workers, especially for derivatives featuring the PNN ligand 2-(di-ferf-butylphosphinomethyl)-6-(diethylaminomethyl)pyridine (Figure 32).146 (PNN)Mo(N2)2(PMe2R) (R = Ph or Me) derivatives were accessed by reduction of the (PNN)MoCl3 precursor and treatment with PMe2R. The PNN ligand was observed to be a stronger donor ligand than the corresponding PNP ligand, as judged by N2 stretching frequencies (1877 cm−1 vs 1915 cm−1 for the PNP ligand). However, treatment of these complexes, or the corresponding nitride derivatives, with excesses of reductants and acids (e.g., 36 equiv of Cp2Co, 48 equiv of [LutH]OTf failed to reveal catalytic activity (Figure 33)). Other PNP ligands, such as N,N′-bis(di-ferf-butyl-phosphino)-2,6-diaminopyridine and 2,6-bis(diadamantyl-phosphinomethyl)pyridine, have also been used to access terminal molybdenum nitrides of the type [(PNP)Mo(N)(Cl)]BArF4; however, these adducts produced little NH3 (1.3 and 1.8 equiv., respectively) when exposed to 36 equiv of Cp2Co and 48 equiv of [LutH]OTf.147

PPP-pincer ligands were next targeted as promising candidates for catalysis (Figure 33).84 Despite difficulties in synthesizing the N2-bridged dimolybdenum PPP-pincer complex, the terminal nitrides, (PPP)Mo(N)(Cl) and [(PPP)Mo(N)(Cl)]BArF4—akin to those prepared in the PNP systems83—were accessible. Exposure of the cationic Mo nitride to [LutH]OTf (48 equiv) and 36 equiv of Cp*2Co produced 6.1 equiv of NH3, whereas Cp*2Cr and Cp2Co were far less effective reductants. However, the use of [ColH]OTf (ColH = 2,4,6-trimethylpyridinium) as the acid produced 9.6 equiv of NH3, and the addition of much higher amounts of reductant and acid (540 equiv of Cp*2Co and 720 equiv of [ColH]OTf), produced as many as 63 equiv of NH3.

4.3. Catalyst Redesign and Keys to Achieving Higher Turnover Numbers

In 2017, Nishibayashi and co-workers proposed that reactive terminal (PNP)Mo(N) could be formed via cleavage of a bridging dinitrogen unit, thus circumventing the formation of early protonation intermediates such diazenido, hydrazido, and hydrazidium (Figure 34).81 Use of (PNP)Mo(I)3 as a precursor afforded access to (PNP)Mo(N)(I) following reduction by Cp*2Co. By contrast, reduction of the chloride-containing species, (PNP)MoCl3, with NaHg amalgam produced [(PNP)Mo(N2)2]2(μ-N2), thus highlighting the importance of the Mo-halide starting material and reductant. Using (PNP)Mo(I)3 as a (pre)catalyst, treatment with standard loadings of 36 equiv of Cp*2Co and 48 equiv of [ColH]OTf gave 10.9 equiv of NH3, while (PNP)Mo(N)(I) gave 12.2 equiv of NH3. Under similar conditions, [(PNP)Mo(N2)2]2(μ-N2) gave 7.1 equiv of NH3. [LutH]OTf was not applicable as an acid source when using (PNP)Mo(I)3 as the (pre)catalyst.

Figure 34.

Proposed pathway for reductive cleavage of N2 to form a terminal nitride, (PNP)Mo(N)(I), of relevance to catalytic N2RR. The observed reactivity profile is I (50.7 equiv of NH3) > Br (40.5 equiv of NH3) > Cl (24.4 equiv of NH3).81

Much higher loadings established the viability of much higher, and truly impressive turnover numbers. For example, the use of 2160 equiv of Cp*2Co and 2880 equiv of [ColH]OTf gave the highest amount of NH3 (415 equiv), more than 35 times greater yield than achieved by [(PNP)Mo(N2)2]2(μ-N2) under similar acid and reductant loadings. A lower amount of ammonia was produced using (PNP)Mo(Br)3 (40.5 equiv of NH3) or (PNP)Mo(Cl)3 (24.4 equiv of NH3) when compared with (PNP)Mo(I)3 (50.7 equiv of NH3; [catalyst] = 0.002 mmol). In all cases, the catalysis showed little competing dihydrogen formation.

The proposed catalytic cycle, which warrants additional experimental support, invokes reduction of (PNP)Mo(X)3 to give [(PNP)]Mo(X)]2(μ-N2), from which (PNP)Mo(N)(X) is then formed (Figure 34). Following a series of stepwise reductive protonation steps (PNP)Mo(NH3)(X) is generated, which then loses NH3 and (re)binds N2 to restart the catalytic cycle. This cycle is interesting to consider by comparison to a distal (or alternating) pathway for N2 reduction via discrete one-electron/one-proton steps, as it features fewer protonated intermediates. Moreover, this work points to the viability of halide precatalysts for generating on path intermediates.

The Nishibayashi group has more recently reported catalytic studies with a variety of molybdenum triiodide complexes containing nearly all of the PNP permutations discussed above, (RPNP)Mo(I)3, including different phosphine substituents (R = H, R′ = tBu, Ad, iPr, or Ph) or different groups at the 4-position of the central ring of the ligand (X = Ph, Me, OMe, Fc, or Rc, R′ = tBu).148 Interestingly, and in contrast to the Mo2(μ-N2) complexes discussed previously, the highest quantity of NH3 was obtained when X = Ph. To rationalize this observation, it was proposed that (PNP)Mo(I)3 and [(PNP)Mo(N2)2]2(μ-N2) operate via different rate-determining steps (RDS). In the molybdenum iodide system, electron-withdrawing groups are thought to promote an RDS involving reduction of a cationic “Mo(NHy)” fragment, while in the Mo2(μ-N2) system, electron-donating groups are thought to promote an RDS involving Nβ protonation.

PCP-type pincer ligands, comprised of both N-heterocyclic carbene and diphosphine donors, have also been explored by the Nishibayashi group in an effort to evaluate N2RR catalyst performance (Figure 35).149 Two such ligands: 1,3-bis(2-(di-tert-butylphosphino)methyl)benzimidazol-2-ylidene (BImPCP) and 1,3-bis(2-(di-tert-butylphosphino)ethyl)imidazol-2-ylidene (ImPCP) were prepared, from which (rPCp)moCl3 (R = Im or BIm) precursors were accessed. Reduction using NaHg amalgam provided the μ-N2 molybdenum complexes [(RPCP)Mo(N2)2]2(μ-N2), for which the IR spectrum provides signals at 1978 cm−1 and 1911 cm−1. The catalytic utility of these compounds was next interrogated using a mixture of [LutH]OTf (96 equiv) and metallocene (72 equiv); the metallocene was added in toluene via syringe pump. After optimization, it was found that pairing larger amounts of reductant (Cp*2Cr: 1440 equiv) and acid ([LutH]OTf: 1920 equiv) with the 5,6-dimethylbenzimidazol-2-ylidene catalyst afforded the maximum (up to 115 equiv) amount of ammonia.

Figure 35.

PCP-type pincer ligands featuring N-heterocyclic carbene donors are useful for N2RR in the presence of [ColH]OTf (96 equiv) and reductant (72 equiv); Cp*2Cr was found to be most effective for both classes of catalyst.149

In an effort to use H2O as a proton source, Nishibayashi and co-workers have explored the combination of coupling wazter oxidation with nitrogen fixation (Figure 36).150 In a model study, water oxidation was performed using ceric ammonium nitrate ([Ce(NO3)6](NH4)2) and a Ru complex, Ru(bda)-(isoq)2 (bda = 2,2′-bipyridine-6,6′-dicarboxylate, isoq = isoquinoline) to generate O2 and acid. Addition of lutidine formed [LutH]+, which upon combination with Cp2Co in the presence of [(PNP)Mo(N2)2]2(μ-N2), generated 8.5 equiv of NH3; this compares well with 9.7 equiv of NH3 that was observed when purified [LutH]OTf was used. Using larger amounts of reagent resulted in up to 17.1 equiv of NH3. Visible light-driven water oxidation was also studied using Na2S2O8 as a sacrificial oxidizing reagent and [Ru(bpy)3]OTf (bpy = 2,2′-bipyridine) as the photosensitizer. Using the same catalyst, 6.0 equiv of NH3 was observed following sequestration of the solvated HOTf with lutidine; it was proposed that sulfate inhibits the formation of NH3 from N2.

Figure 36.

Efforts toward using H2O as a proton source in N2RR. Water oxidation was performed using [Ru(bpy)3]OTf2 as a photooxidant, peroxydisulfate as a sacrificial reductant, and a Ru complex, [Ru(bda)-(isoq)2] (bda = 2,2′-bipyridine-6,6′-dicarboxylate, isoq = isoquinoline), as the water oxidation catalyst. The generated acid was trapped using lutidine to give [LutH]+, which enabled N2RR catalysis by (PNP)Mo.150

4.4. New Conditions Lead to Remarkable Rate and Efficiency

Very recently, Nishibayashi and co-workers have exploited SmI2 as a reductant compatible with polar, protic H+ donors (e.g., alcohols or water) (Figure 37).79 Related approaches have been gaining in popularity for the reduction of organic molecule substrates owing to the dramatic O–H bond weakening that occurs upon coordination of the alcohol or water to the Sm(II) center.151–154 This is an exciting result that opens up a new approach for the study of N2RR catalysts that shows great promise. Indeed, the selectivity for NH3 and total turnover number demonstrated in this recent report are remarkable. Using the aforementioned (BMimPCP)Mo(Cl)3 precatalyst, reaction of N2 with SmI2 and ethylene glycol generates NH3 at a turnover frequency (TOF) of 117 min−1. Water can also be used in this reaction; treatment of N2 with a [Mo]-precatalyst, SmI2 (14 400 equiv), and H2O (14 400 equiv) in THF at room temperature for 4 h gives 4350 equiv of NH3 (91%).

Figure 37.

Remarkable efficiencies were achieved using a Sm/alcohol mixture for N2RR. This reaction is proposed to occur via PCET. Use of H2O (14400 equiv) and SmI2 (14 400 equiv). gave ca. 4350 equiv of NH3.79

5. ACHIEVING NITROGEN FIXATION CATALYSIS AT Fe

For decades, Mo had played center stage in the modeling of biological nitrogenases, owing in part to its early discovery within the MoFe variant.48 The initially unexpected presence of Mo, the sensitivity of nitrogenase performance to alterations near Mo, and the early success in developing model systems, led to a strong emphasis on this metal as being the site of N2RR. Then, in 1986, it was discovered that there was a vanadium-dependent nitrogenase, VFe,155 and subsequently in 1988, the existence of an all Fe biological nitrogenase was disclosed.156 Subsequent study of the biological nitrogenases has led to the conclusion that they are likely structurally (and potentially mechanistically) similar.11,36,157–159 In particular, recent spectroscopic and crystallographic evidence has begun to emerge in both the MoFe and VFe nitrogenases that the site of N2-binding and functionalization is likely to be at an Fe site. In particular, both the Rees and Einsle groups have obtained structures that demonstrate sulfide-loss and ligand binding between Fe2 and Fe6 (Figure 38).160,161 Meanwhile, Hoffman, Seefeldt, and co-workers have established that reductive elimination of bridging iron hydrides may be essential to N2 binding in all three biological nitrogenases.158,159,162

Figure 38.

Structure of a recently reported, proposed intermediate of VFe-nitrogenase, featuring removal of a bridging sulfide as SH− and the identification of a μ2-bridging light atom in its place. The light atom (X) has been hypothesized to be the N atom of an imido ligand.161 Further studies are needed to validate this assignment.