Abstract

Background

Inflammation is considered as one of the hallmarks of cancer development and progression. Ursolic acid (UA) showed strong effects as an anti-inflammatory and antioxidant. However, the anti-cancer effects of ursolic acid require further study.

Methods

This study aimed to investigate the role of ursolic acid in a lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-treated gastric tumour mouse model and in a human gastric carcinoma cell line (BGC-823 cells). This study also aimed to confirm whether ursolic acid can protect against proliferation and the inflammatory response induced by LPS, by inhibiting the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome via the NF-κB pathway.

Results

The present study demonstrated that ursolic acid significantly attenuated LPS-treated proliferation in a gastric tumour mouse model and the human gastric carcinoma BGC-823 cell line, reduced the expression of the NLRP3 inflammasome and suppressed the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines. In addition, ursolic acid inhibited the LPS-induced activation of NF-κB. Furthermore, the NF-κB pathway regulated the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome.

Conclusion

In conclusion, these results demonstrated that ursolic acid could suppress proliferation and the inflammatory response in an LPS-induced mouse gastric tumour model and human BGC-823 cells by inhibiting the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome via the NF-κB pathway. This indicates that ursolic acid can be a potential therapeutic agent for the treatment of gastric cancer.

Keywords: ursolic acid, gastric carcinoma, NLRP3 inflammasome, proliferation, inflammatory, NF-κB pathway

Introduction

Gastric cancer is one of the most common malignant tumours in the world.1,2 According to the latest cancer data, the morbidity and mortality of gastric cancer have risen to second place among malignant tumours in China.3 This is largely due to the lack of an effective clinical treatment.

Inflammation is considered a key hallmark of cancer. In the mid-19th century, Rudolph Virchow discovered a link between inflammation and cancer.4,5 In addition, previous studies found that more than 25% of malignant tumours are associated with chronic inflammation, infection, or both.6–8 Furthermore, other studies suggested that inflammation facilitates tumour development, progression, metastatic dissemination, as well as treatment resistance.9 Inflammation is a hallmark of innate immunity, which is triggered by pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). Both of these are recognised by pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs), which include members of the Toll-like receptors (TLRs), and nucleotide-binding and oligomerisation domain containing receptors (NOD-like receptors, NLRs).10 Once activated, several innate immune cells such as monocytes/macrophages are upregulated and secrete numerous inflammatory chemokines and cytokines, as well as activate a number of transcription factors such as NF-κB.11,12 Since dysregulation of the inflammatory immune response can lead to cancer, elucidating the inflammation reaction is of great significance to the development of effective therapies for cancer.

In recent years, Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), as the common alternative and complementary treatment, has established numerous treatments for cancer, indicating that TCM may be a promising alternative treatment for cancer in the future. Ursolic acid (UA), a triterpenoid compound widely found in nature, has a variety of rich biological activities including as an anti-inflammatory, anti-tumour etc.13 Thus, the anti-cancer effects of UA have attracted increasing worldwide interest. Studies have reported that UA inhibits the growth of cells in multiple types of cancer, such as hepatocellular carcinoma cells,14–16 breast cancer cells etc.17 The anti-cancer effect of UA is related to a variety of biological activities, including tumour cell apoptosis,18–20 and inhibiting tumour cell proliferation.14–17 In addition, UA plays an anti-cancer role through its tumour-specific immunoregulation. UA decreased the production and expression of VEGF and IL-8 in a dose-dependent manner, decreased ROS and NO levels, and decreased the migration and invasion of liver cancer cells.16 UA also suppressed lung cancer via decreasing the activity of NF-κB and inhibiting the proliferation of cancer cells.21 Together, these results suggest that UA has an immunoregulatory effect.

NOD-Like Receptors, especially the pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, which is composed of NLRP3, ASC and caspase-1,22 play a key role in mediating inflammatory responses by regulating production of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, and IL-18 in various tissues.23 In fact, induction of NF-κB subunit P65 phosphorylation leads to activation of NF-κB signalling, and transcriptional activation of NLPR3.24 However, it is unknown if the NF-κB-NLRP3 pathway is involved in the LPS-induced inflammatory response in gastric cells.

The objective of this study was to investigate if ursolic acid exhibits protection against LPS-induced inflammation, which promotes tumours, and explore the underlying mechanism (s).

Materials and Methods

Culture of BGC-823 Cells

The human gastric carcinoma cell line BGC823 was purchased from the Shanghai Institute of Cell Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). The cells were maintained in endotoxin-free RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen-Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), 100 µ/mL penicillin, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Once the BGC-823 cells reached 70%–80% confluence, they were transferred to 6-well plates (Corning, Inc., Corning, NY, USA) at a density of 3 × 105 cells per well and incubated in 10% FBS medium at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator overnight. Cells were treated with 50 µmol/L concentrations of UA, or 50 µmol/L NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor MCC950 or 25 µmol/L NF-κB inhibitor BAY-117082, accompanied with LPS (100 ng/mL) and then incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. UA (purity > 98%) and LPS were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), while MCC950 and BAY11-7082 were purchased from Selleck Chemicals LLC (Houston, TX, USA). All drugs were dissolved in DMSO.

Cell Proliferation Assays

Once BGC-823 cells reached 70% confluence, they were transferred to 96-well plates (Corning, Inc., Corning, NY, USA) at a density of 3 × 103 cells per well and incubated in 10% FBS medium at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator overnight. Cells were treated with different concentrations of UA (10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, and 80 µmol/L) or the NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor MCC950 (10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, and 90 µmol/L) accompanied with LPS (100 ng/mL) and then incubated at 37 °C for different durations (12, 24, 48, and 72 h). Cell proliferation was assessed using a cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8, Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc., Kumamoto, Japan) as described in the manufacturer’s recommendations. The absorbance at 450 nm was measured with an enzyme marker. Results were expressed as the mean ± SD.

Mouse Gastric Tumour Model

Six to eight-week-old female BALBc/c nu/nu mice (18–20 g body weight) were purchased from the Shanghai SLAC Laboratory Animal Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China) and were housed in the Laboratory Animal Centre of Putuo Hospital, Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Mice were maintained under a specific pathogen-free environment with the following conditions: 12 h light/dark cycles, temperature between 22–25 °C, and humidity of 50–60%. BGC-823 cells (1×107 cells/200 µL in PBS) were subcutaneously administered into the left axilla of nude mice via a syringe. Seven days later, the animals were randomly separated into one control group and three experimental groups (n = 5 mice/group). The control groups were treated with PBS (0.01 mol/L), while the experiment groups were treated with UA (10 mg/kg in 0.01 mol/L PBS), LPS (250 µg/kg in 0.01 mol/L PBS), or a mixture of LPS and UA (250 µg/kg LPS and 10 mg/kg UA in 0.01 mol/L PBS). After 14 days of drug administration, all nude mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation and tumour tissue samples from each group were removed and weighed, then cut into suitable pieces for Western blotting, RT-PCR and ELISA. Tumour volume (TV) was calculated by the formula, TV (mm3) = (L×w2)/2, where L is the longest dimension of the tumour (in mm) and W is the shortest dimension of the tumour (in mm). All animal experiments were approved and carried out in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Putuo hospital, affiliated with the Shanghai University of Chinese Medicine.

Western Blotting Analysis

Protein samples were extracted from tumour tissues and cells using RIPA buffer (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). Protein quantification of each sample was measured using a BCA kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). Fifty µg of total protein was separated by 10% SDS–PAGE and subsequently transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). After incubation for 2 h at room temperature with 5% fat-free dry milk, the membranes were incubated with specific primary antibodies: NLRP3 (#15101,1:1000), ASC (#67824,1:1000), phospho-p65 (#3033,1:1000), totalp65 (#8242,1:1000), Cleaved caspase-3 (#9661,1:1000), GAPDH (#2118,1:10000, purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA), IL-1β (sc-32294, purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) overnight at 4 °C. The membranes were washed three times with TBST (Tris-buffered saline-0.1% Tween-20, 10 min/wash) and were incubated with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody at 1:5000 dilution for 1 h at room temperature. The image software (Quantity One, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) was used to analysis the densitometry of bands.

RT-PCR Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from tumour tissues and cells using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The PrimeScript® RT Reagent kit (Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Dalian, China) was used to transcribe RNA into cDNA at 37 °C for 15 min, 85 °C for 5 sec, and held at 4 °C, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. qPCR was performed with cDNA, SYBR (Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), forward/reverse primers and sterile water on a Real-Time PCR Detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA). The real-time PCR conditions included denaturation at 95 °C for 30 sec, and 40 cycles of denaturation and annealing/extension at 60 °C for 1 min. The levels of mRNA expression were quantified using the 2-∆∆Cq method.25 Specific primers of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and CCL-2 are listed as follows:

IL-1β: A:5′-GTGGCAATGAGGATGACTT-3′ S:5′-TGGGCTTATCATCTTTCAA-3′, IL-6: A:5′-CCTTCCAAAGATGGCTGAAA-3′ S:5‘-AGCTCTGGCTTGTTCCTCAC-3′, TNF-α: A:5′-GCCCCCAGAGGGAAGAGTTCCCCA-3′ S:5′-GCTTGAGGGTTTGCTACAACATGGGC-3′, CCL-2: A:5′-CTTCTGTGCCTGCTGCTCAT-3′ S:5‘-GCTTGTCCAGGTGGTCCAT-3′, β-actin: A:5′-TGTTACCAACTGGGACGACA-3′ S:5′-CTGGGTCATCTTTTCACGGT-3′.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) Analysis

Concentrations of IL-1β in culture supernatant of cells and tumour tissues were determined with a specific ELISA (R&D System, Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

Caspase-1 Activity Analysis

Caspase-1 activity was determined using the specific Caspase-1 Activity Assay Kit (#C1101) purchased from Beyotime according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 21.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Individual comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA and the Student-Newman-Keuls test. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Effects of UA on the Proliferation and Inflammatory Response of an LPS-Treated Mouse Gastric Tumour Model

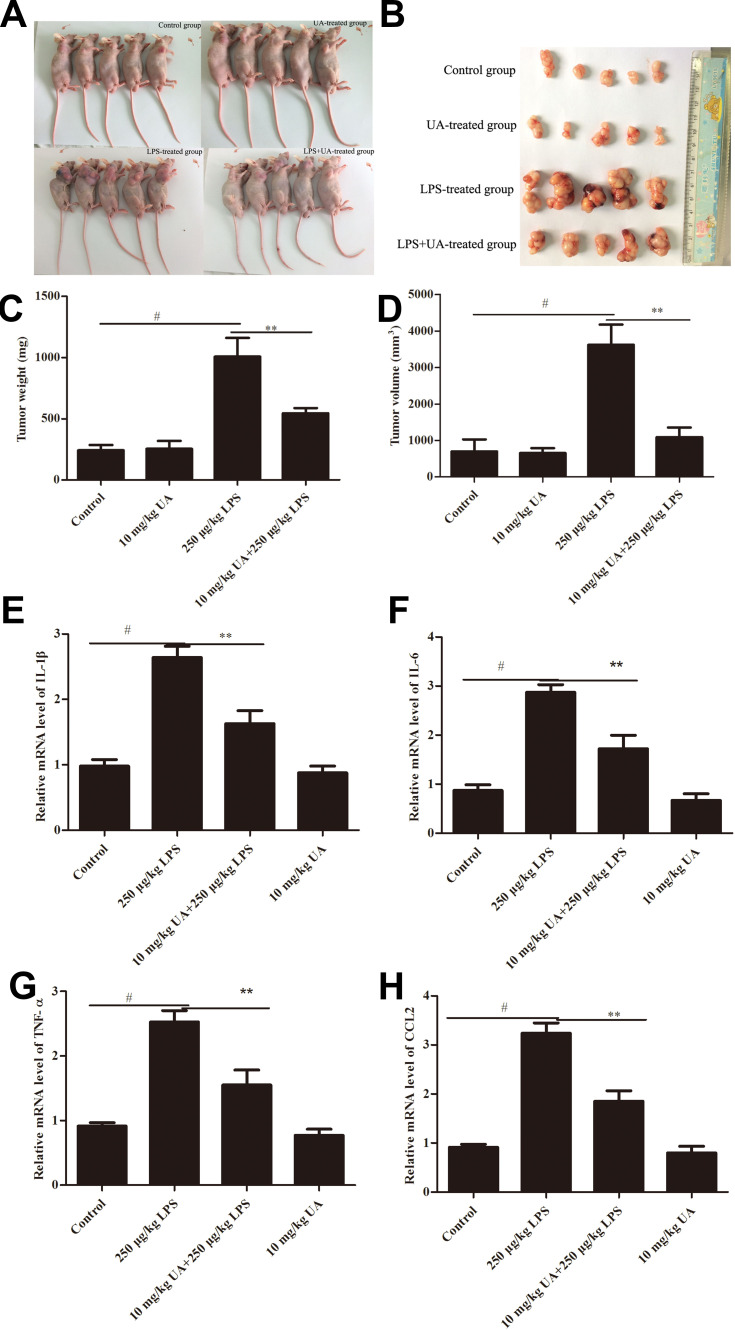

Previous studies have shown that LPS is able to stimulate tumour growth.26–31 Consistent with these studies, LPS-treated mice observed significant tumour growth compared to the control group (Figure 1A–D). In this study, we first investigated the anti-growth effect of UA on a LPS-induced gastric cancer mouse model in vivo. As expected, UA significantly attenuated the weight, and volume of tumours in the UA+LPS injection group compared with the LPS-treated group (Figure 1A–D, **P<0.01). These data indicated that UA inhibited LPS-induced tumour proliferation in a mouse gastric tumour model.

Figure 1.

Ursolic acid treatment attenuates the proliferation and inflammatory response in a LPS-induced mouse tumours model. BGC-823 cells (1×107 cells/200 µL in PBS) were subcutaneously administered into the left axilla of nude mice via a syringe. Seven days later, the animals were randomly separated into one control group and three experimental groups (n = 5 mice/group). The control groups were treated with PBS (0.01 mol/L), while the experimental groups were treated with UA (10 mg/kg in 0.01 mol/L PBS), LPS (250 µg/kg in 0.01 mol/L PBS), or a mixture of LPS and UA (250 µg/kg LPS and 10 mg/kg UA in 0.01 mol/L PBS). After 14 days of drug administration, all nude mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation and tumour tissue samples from each group were removed. Tumour volume (TV) was calculated by the formula, TV (mm3) = (L×w2)/2, where L is the longest dimension of the tumour (in mm) and W is the shortest dimension of the tumour (in mm). The tumour photos (A and B), volume (C) and weight (D) of the mice were analysed using one-way ANOVA. mRNA levels of IL-1β (E), IL-6 (F), TNF-α (G) and CCL-2 (H) were detected by quantitative real-time RT-PCR. All data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 5, #P<0.01 significantly different from the control group; **P<0.01 significantly different from the LPS-treated group).

In order to verify whether LPS-induced pro-inflammatory cytokines release could be inhibited by UA, we tested the mRNA levels of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α and CCL-2 by RT-PCR. The RT-PCR results showed that the mRNA levels of IL-1β (Figure 1E), IL-6 (Figure 1F), TNF-α (Figure 1G) and CCL-2 (Figure 1H) were significantly increased in the LPS-induced mouse gastric tumour model compared with the control group (#P<0.01). Conversely, the level of these markers was attenuated after UA treatment (Figure 1E–H **P<0.01). These data indicated that UA inhibited the LPS-induced inflammatory response in a mouse gastric tumour model.

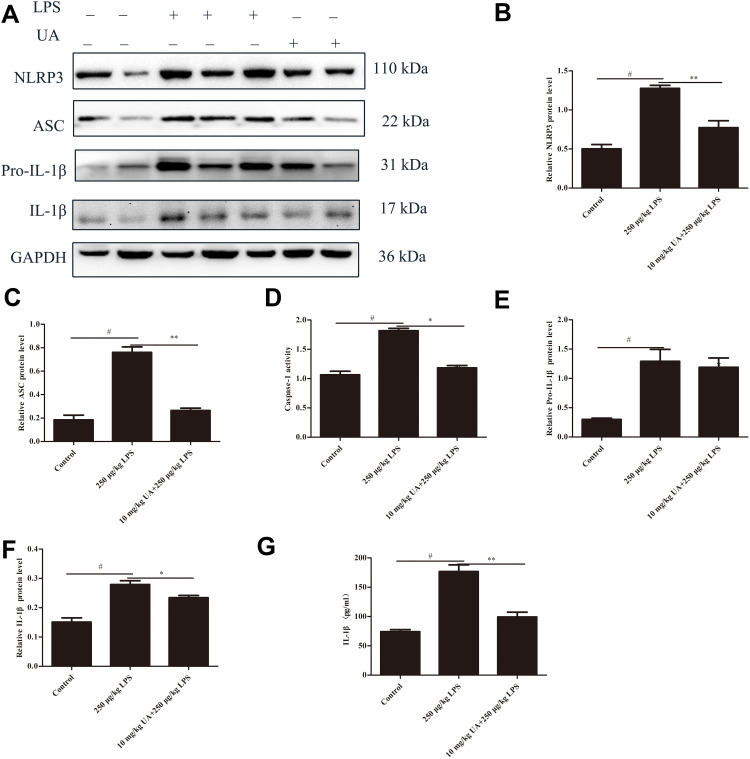

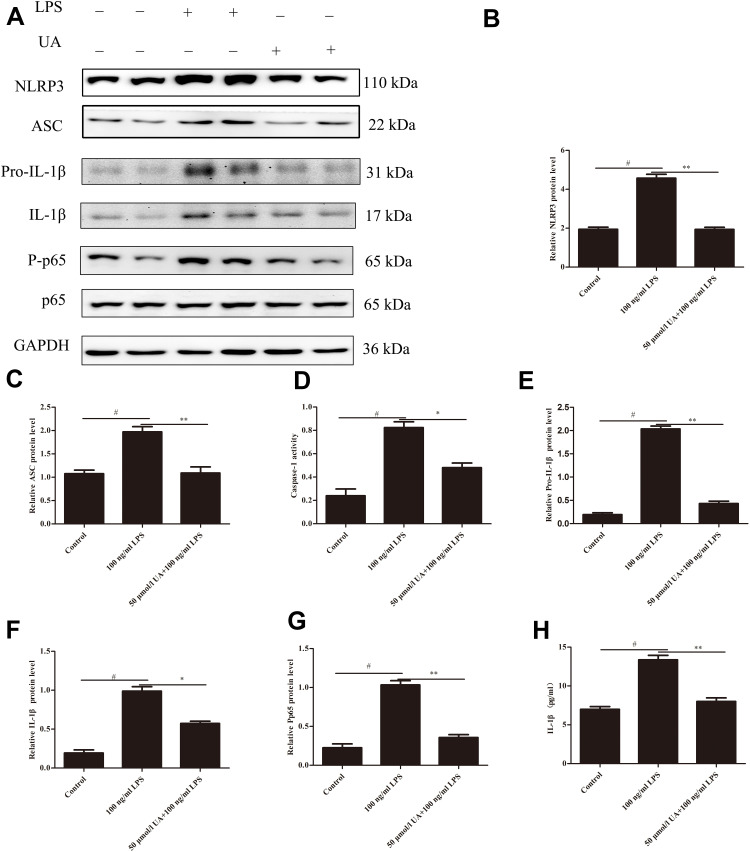

UA Inhibits the LPS-Induced Activation of the NLRP3 Inflammasome in a Mouse Gastric Tumour Model

The NLRP3 inflammasome plays a critical role in the LPS-induced inflammation model.32 Consistent with that study, the expression of NLRP3, ASC, and the levels of activated caspase-1 in this study were significantly upregulated in LPS-treated groups compared with the control groups (Figure 2A–D #P<0.01). In addition, the expression of Pro-IL-1β (Figure 2E), IL-1β (Figure 2F) and the production of IL-1β (Figure 2G) by ELISA were increased in the LPS-treated group compared with control groups (#P<0.01). However, the expression of NLRP3, ASC, caspase-1, and IL-1β, and the production of IL-1β in the LPS + UA group were significantly reduced compared to the LPS group (Figure 2A–G, *P<0.05, **P<0.01)). These data indicated that UA inhibited the activation of the LPS-induced NLRP3 inflammasome.

Figure 2.

Ursolic acid inhibited the LPS-induced expression of the NLRP3 inflammasome in mice. (A) Protein levels of NLRP3, ASC, Pro-IL-1β and IL-1β were evaluated by Western blot analysis. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Densitometry analysis of the effects of UA on the expression of NLRP3 (B) and ASC (C). An activity detection kit measured Caspase-1 activity (D). The effect of UA on the protein expression of Pro-IL-1β (E) and IL-1β (F) was examined by Western blot analysis. (G) Production of IL-1β was measured using an ELISA kit. One-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. All data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 5, #P<0.01, significantly different from the control group; *P<0.05, **P<0.01 significantly different from the LPS-treated group).

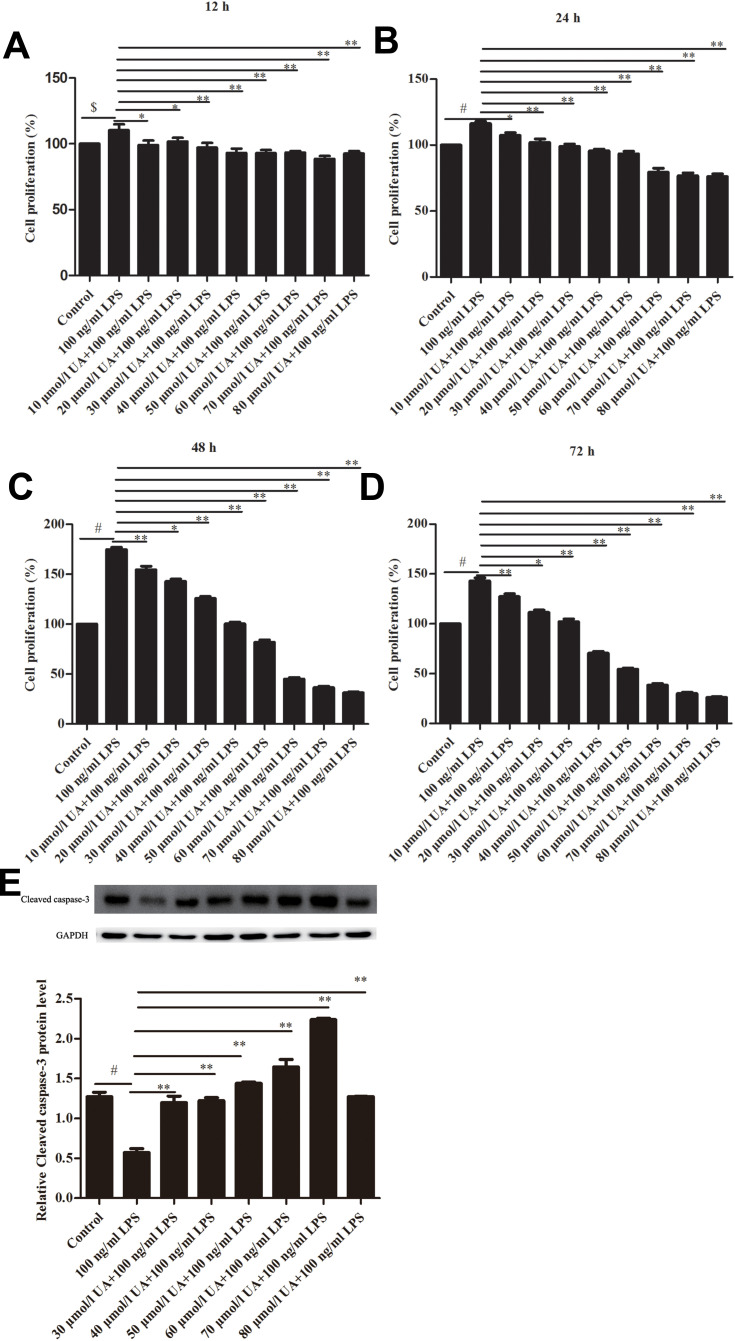

Effects of UA on the Proliferation of LPS-Treated BGC-823 Cells

We first investigated the anti-proliferative effect of increasing concentrations (10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, and 80 µmol/L) and time points (12, 24, 48, 72 h) of UA on LPS-treated BGC-823 cells using the CCK8 assay. As illustrated in Figure 3A–D, with a dose-dependent pretreatment of UA for a 12–72 h incubation time, cell viability was gradually decreased and maintained at the lowest levels with 50–80 µmol/L UA compared to LPS-treated cells that were not pretreated with UA. As illustrated in Figure 3E, consistent with the cell viability, pretreatment of 30–80 µmol/L UA for a 48 h incubation time, UA increased the protein level of cleaved caspase-3 compared to LPS-treated cells that were not pretreated with UA. Moreover, a significant decrease of cell viability was detected at 12–72 h with 50 µmol/L UA (Figure 3A–D, *P< 0.05; **P<0.01). Therefore, 50 µmol/L UA treatment for 48 h was used for most of the subsequent experiments. These data indicated that UA inhibited LPS-induced tumour cell proliferation.

Figure 3.

The effects of UA on the proliferation of LPS-induced BGC-823 cells. Dose-dependent (10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70 and 80 µmol/L) and time-dependent effects of UA on cell proliferation of LPS (100 ng/mL) induced BGC-823 cells. Cell proliferation was assayed by the CCK-8 Kit at 12 h (A), 24 h (B), 48 h (C), and 72 h (D). Western blot analysis was performed to assess the induction of cleaved caspase-3 (E). All data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 6, $P<0.05, #P<0.01, significantly different from the control group; *P<0.05, **P<0.01 significantly different from the LPS-treated group).

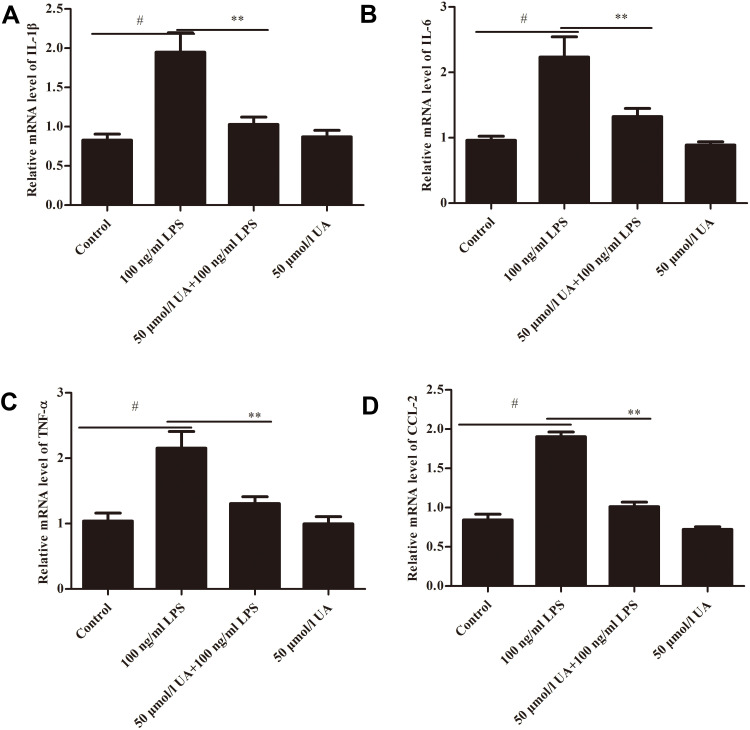

Effect of UA on the Expression of Inflammatory Cytokines in LPS-Induced BGC-823 Cells

Furthermore, we investigated the effect of UA on the LPS-induced inflammatory response in BGC-823 cells. We detected mRNA levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and CCL-2 in the LPS +UA group. The RT-PCR results indicated that the mRNA levels of IL-1β (Figure 4A, #P< 0.01), IL-6 (Figure 4B, #P< 0.01), TNF-α (Figure 4C, #P< 0.01) and CCL-2 (Figure 4D, #P< 0.01) were highly expressed in LPS-induced BGC-823 cells. Conversely, these markers were markedly decreased after 50 µmol/L UA pre-treatment (Figure 4A–D, **P< 0.01). Therefore, these data indicated that UA inhibited the LPS-induced inflammatory response in BGC-823 cells.

Figure 4.

The effects of UA on the expression of LPS-induced inflammatory cytokines in BGC-823 cells. BGC-823 cells were treated with LPS (100 ng/mL) for 48 h in the presence or absence of pre-treatment with UA (50 µmol/L) for 60 min. mRNA levels of IL-1β (A), IL-6 (B), TNF-α (C) and CCL-2 (D) were detected by quantitative real-time RT-PCR. All data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 6, #P<0.01, significantly different from the control group; **P<0.01 significantly different from the LPS-treated group).

UA Inhibits the LPS-Induced Activation of the NLRP3 Inflammasome in LPS-Treated BGC-823 Cells

In addition, in this study, we confirmed that the increased expression of NLRP3, and ASC induced by LPS (Figure 5A–C, #P< 0.01) was significantly attenuated after 50 µmol/L UA pre-treatment (Figure 5A–C, **P<0.01). Since caspase-1 activation is a critical step for activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome,22 we then investigated the effect of UA on caspase-1 activity. The results show that the high level of activated caspase-1 induced by LPS (Figure 5D, #P< 0.01) was markedly decreased in the 50 µmol/L UA pre-treatment group (Figure 5D, *P< 0.05). In addition, increased expression of Pro-IL-1β (Figure 5E, #P< 0.01), IL-1β (Figure 5F and H, #P< 0.01), and activation of NF-κB (Figure 5G, #P< 0.01) induced by LPS were also attenuated in the 50 µmol/L UA pre-treatment group (Figure 5E–H, *P< 0.05; **P< 0.01). These data indicated that UA inhibited the LPS-induced activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in BGC-823 cells.

Figure 5.

LPS-induced induction of the NLRP3 inflammasome and NF-κB in BGC-823 cells is attenuated by UA treatment. BGC-823 cells were treated with LPS (100 ng/mL) for 48 h in the presence or absence of pre-treatment with UA (50 µmol/L) for 60 min. (A) Protein levels of NLRP3, ASC, Pro-IL-1β, IL-1β, and NF-κB were evaluated by Western blot analysis. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Densitometry analysis of the effects of UA on expression of NLRP3 (B) and ASC (C). An activity detection kit measured Caspase-1 activity (D). The effect of UA on the protein expression of Pro-IL-1β (E), IL-1β (F), and NF-κB (G) was examined by Western blot analysis. (H) The production of IL-1β was measured using an ELISA kit. One-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. All data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 6, #P<0.01, significantly different from the control group; *P<0.05, **P<0.01 significantly different from the LPS-treated group).

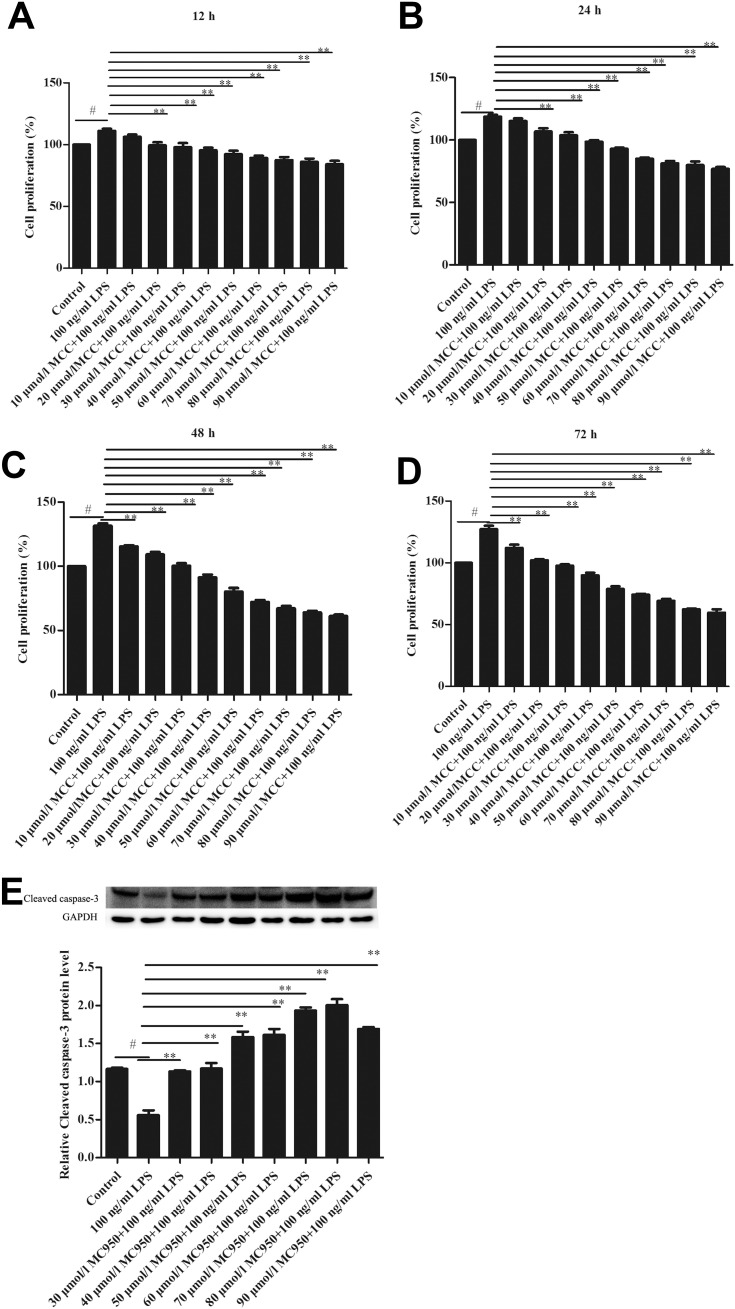

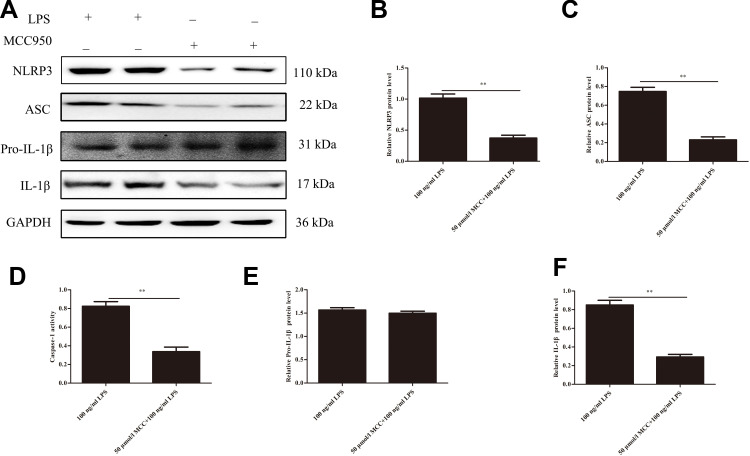

Tumour Cell Proliferation and the Inflammatory Response to LPS are Mediated by the NLRP3 Inflammasome

To evaluate the role of the NLRP3 inflammasome in LPS-induced changes in proliferation and the inflammatory response, we used the NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor MCC950 in BGC823 cells. We first investigated the contribution of NLRP3 to LPS-induced cell proliferation with increasing concentrations (10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, and 90 µmol/L) and time points (12, 24, 48, 72 h) of MCC950 on LPS-treated BGC-823 cells using the CCK8 assay. As illustrated in Figure 6A–D, with a dose-dependent pretreatment of MCC950 for a 12–72 h incubation time, cell proliferation was gradually decreased and maintained at the lowest levels with 50–90 µmol/L MCC950 compared to LPS-treated cells that were not pretreated with MCC950. As illustrated in Figure 6E, consistent with the cell viability, pretreatment of 30–90 µmol/L MCC950 for a 48 h incubation time, increased the protein level of cleaved caspase-3 compared to LPS-treated cells that were not pretreated with MCC950. Moreover, a significant decrease in cell viability was detected at 12–72 h with 50 µmol/L MCC950 (Figure 6A–D, **P<0.01). Therefore, a 50 µmol/L MCC950 treatment for 48 h was used for most of the subsequent experiments. The increased level of NLRP3, ASC, IL-1β and activated caspase-1 induced by LPS were significantly attenuated in the MCC950 pretreatment group (Figure 7A–F, **P< 0.01). Thus, the data showed that LPS-induced tumour cell proliferation and the inflammatory response were mediated by the NLRP3 inflammasome.

Figure 6.

LPS-induced proliferation in BGC-823 cells is mediated by the NLRP3 inflammasome. Dose-dependent (10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80 and 90 µmol/L) and time-dependent effects of the NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor MCC950 on cell proliferation of LPS (100 ng/mL) induced BGC-823 cells. Cell proliferation was assayed by the CCK-8 Kit at 12 h (A), 24 h (B), 48 h (C), and 72 h (D). Western blot analysis was performed to assess the induction of cleaved caspase-3 (E). All data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 6, #P < 0.01, significantly different from the control group; **P<0.01 significantly different from the LPS-induced group).

Figure 7.

The NLRP3 inflammasome regulated the expression of LPS-induced inflammatory cytokines in BGC-823 cells. (A) Protein levels of NLRP3, ASC, Pro-IL-1β and IL-1β were evaluated by Western blot analysis. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Densitometry analysis of the effects of MCC950 on the expression of NLRP3 (B) and ASC (C). An activity detection kit measured Caspase-1 activity (D). The effect of MCC950 on the protein expression of Pro-IL-1β (E), and IL-1β (F) was examined by Western blot analysis. All data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 6, significantly different from the control group; **P<0.01 significantly different from the LPS-treated group).

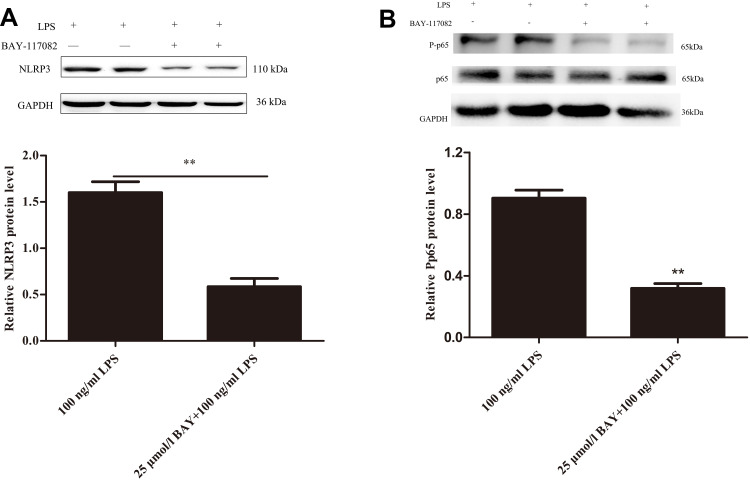

The LPS-Induced Activation of the NLRP3 Inflammasome is Mediated by NF-κB

Previous studies have shown that NF-κB binding sites are present in the NLRP3 promoter.33,34 We further investigated the connection between NF-κB and the NLRP3 inflammasome in LPS-treated BGC-823 cells. We found that the expression of NLRP3 and NF-κB activity were markedly increased in LPS-treated cells (Figure 5A and B and G, **P< 0.01). We then used the NF-κB inhibitor BAY11-7082 to inhibit the expression of NF-κB, and the results indicated that BAY11-7082 could reduce NLRP3 protein expression (Figure 8A and B, **P< 0.01). Thus, the data conclusively showed that the NF-κB pathway is potentially inducing the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome following LPS treatment.

Figure 8.

NF-κB induced the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in LPS-induced BGC-823 cells. BGC-823 cells were treated with LPS (100 ng/mL) for 48 h ± BAY-117082 (25 µmol/L) pre-treatment for 60 min. Protein levels of NLRP3 were evaluated by Western blot analysis (A). Protein levels of Pp65 were evaluated by Western blot analysis (B). GAPDH was used as a loading control. Densitometry analysis of the effects of BAY on expression of NLRP3 and Pp65. All data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 6, **P<0.01 significantly different from the LPS-induced group).

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that LPS-induced inflammation plays a critical role in mediating gastric cancer tumour initiation and development, and that the NLRP3 inflammasome is localised in gastric cancer tissues. NLRP3 and ASC expression and Caspase-1 activity are upregulated in LPS-treated gastric cancer cells and tumour tissues. The activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome is closely associated with the NF-κB pathway following LPS treatment. Previous publications have reported that UA has anti-inflammatory and anti-tumour functions.35,36 Our results demonstrated that ursolic acid could suppress the inflammatory response and tumour proliferation in a LPS-treated mouse gastric tumour model and human BGC-823 cells by inhibiting the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome via the NF-κB pathway. Recently, remarkable advancements have increased our understanding of how inflammation plays a critical role in mediating tumour initiation and development.9,10,27 Inflammatory cytokines, which are associated with the tumour microenvironment, play an important role in the occurrence, progression, and promotion of cancer. LPS is the main pathogenic factor of gram-negative bacteria, which are commonly observed in patients with gastric and lung cancer. In addition, previous research reported that LPS effectively stimulates tumour growth in experimental models of NSCLC.25 In the present study, LPS-induced the inflammatory response, which promotes tumour progression in a gastric cancer mouse model and human BGC-823 cells.

UA, a natural pentacyclic triterpenoid carboxylic acid, is the major component of some traditional herbal medicines. Previous publications have reported that UA has anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidative, and anti-diabetic functions.35,36 Studies have also shown that UA induces apoptosis of gastric cancer cells by inhibiting the expression of COX-2.17 Moreover, an in vivo mouse model of gastric cancer confirmed the anti-tumour effect of UA. In our study, UA attenuated the LPS-induced inflammatory response and tumour progression, and suppressed the LPS-induced NLRP3 inflammasome and NF-κB activity.

Inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, form a positive feedback loop to induce cell and DNA damage and accelerate cell proliferation and transformation.37 Our results showed that the expression of the inflammatory factors IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, and CCL-2 increased in a LPS-treated mouse model and BGC-823 cells. Conversely, these mediators decreased after UA treatment. These data suggest that UA inhibited the activation of the inflammatory cascade in LPS-treated in vivo and in vitro experiments.

NF-κB is a significant nuclear transcription factor, which promotes transcription of genes related to inflammation. NF-κB is activated in a variety of tumour types, such as liver cancer, lung cancer, breast cancer, etc. In our study, we found that NF-κB phosphorylation and NF-κB activity significantly increased in LPS-treated BGC-823 cells. Furthermore, research has shown that NF-κB regulates the expression of genes associated with proliferation, invasion, as well as metastasis of cancer.38 Thus, NF-κB is a key target in the development of a cancer treatment.

Recently, significant advances have greatly improved our understanding of NLR function. NLRs, including inflammasomes, play a key role in the initiation and progression of cancer.10 The NLRP3 inflammasome is the most extensively studied member of the NLR family. Our data show that the protein expression level of NLRP3 and ASC successfully increased in LPS-induced in vivo and in vitro experiments. Furthermore, the results show that activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome led to the activation of caspase-1 and increased expression of IL-1β. We also showed that inhibition of NLRP3 significantly attenuated the LPS-induced cell proliferation and activation of IL-1β. Thus, these results show that the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome is a key factor in the development of cancer in LPS-induced in vivo and in vitro experiments.

NF-κB plays a critical role in regulating inflammation and serves as the first signal in the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome.12,39–41 Previous studies demonstrated that NF-κB inhibition led to a remarkable reduction of NLRP3 expression.33 We found that blocking NF-κB activation with the NF-κB inhibitor BAY-117082 could downregulate NLRP3 expression in BGC-823 cells. Cumulatively, these results suggest that the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome is closely associated with the NF-κB pathway, following LPS treatment.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that ursolic acid could suppress proliferation and the inflammatory response in a LPS-treated mouse gastric tumour model and BGC-823 cells by inhibiting the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome via the NF-κB pathway. Therefore, ursolic acid is a potential therapeutic for preventing cancer in the future.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China 31800988 (Z.X. Chen), Personnel Training Program Funded by Putuo Hospital affiliated to Shanghai University of Chinese Medicine 2017216A (Z.X. Chen).

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest for this work.

References

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen W, Zheng RS, Baade PD, et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(2):115–132. doi: 10.3322/caac.21338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet. 2001;357(9255):539–545. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Virchow R. Diekrankhaften GeschwülsteR. Berlin: August Hirschwald; 1863:57–101. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karin M. Nuclear factor-κB in cancer development and progression. Nature. 2006;441(7092):431–436. doi: 10.1038/nature04870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hussain SP, Harris CC. Inflammation and cancer: an ancient link with novel potentials. Int J Cancer. 2007;121(11):2373–2380. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, et al. Cancer related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454(7203):436–444. doi: 10.1038/nature07205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shalapour S, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer: an eternal fight between good and evil. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(9):3347–3355. doi: 10.1172/JCI80007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhiyu W, Wang N, Wang Q, et al. The inflammasome: an emerging therapeutic oncotarget for cancer prevention. Oncotarget. 2016;7(31):50766–50780. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kono H, Rock KL. How dying cells alert the immune system to danger. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(4):279–289. doi: 10.1038/nri2215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gross O, Thomas CJ, Guarda G, et al. The inflammasome: an integrated view. Immunol Rev. 2011;243(1):136–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01046.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li W, Yan R, Liu Y, et al. Co-delivery of Bmi1 small interfering RNA with ursolic acid by folate receptor-targeted cationic liposomes enhances anti-tumor activity of ursolic acid in vitro and in vivo. Drug Deliv. 2019;26(1):794–802. doi: 10.1080/10717544.2019.1645244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tian Z, Lin G, Zheng RX, et al. Anti-hepatoma activity and mechanism of ursolic acid and its derivatives isolated from Aralia decaisneana. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(6):874–879. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i6.874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim KA, Lee JS, Park HJ, et al. Inhibition of cytochrome P450 activities by oleanolic acid and ursolic acid in human liver microsomes. Life Sci. 2004;74(22):2769–2779. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin CC, Huang CY, Mong MC, et al. Antiangiogenic potential of three triterpenic acids in human liver cancer cells. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59(2):755–762. doi: 10.1021/jf103904b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Milgraum LZ, Witters LA, Pasternack GR, et al. Enzymes of the fatty acid synthesis pathway are highly expressed in in situ breast carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 1997;3(11):2115–2120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yan SL, Huang CY, Wu ST, et al. Oleanolic acid and ursolic acid induce apoptosis in four human liver cancer cell lines. Toxicol in Vitro. 2010;24(3):842–848. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2009.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shyu MH, Kao TC, Yen GC. Oleanolic acid and ursolic acid induce apoptosis in HuH7 human hepatocellular carcinoma cells through a mitochondrial-dependent pathway and downregulation of XIAP. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58(10):6110–6118. doi: 10.1021/jf100574j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu YX, Gu ZL, Yin JL, et al. Ursolic acid induces human hepatoma cell line SMMC-7721 apoptosis via p53-dependent pathway. Chin Med J. 2010;123(14):1915–1923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shishodia S, Majumdar S, Banerjee S, et al. Ursolic acid inhibits nuclear factor-kappaB activation induced by carcinogenic agents through suppression of IkappaBalpha kinase and P65 phosphorylation: correlation with down-regulation of cyclooxygenase 2, matrix metalloproteinase 9, and cyclin D1. Cancer Res. 2003;63(15):4375–4383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Latz E, Xiao TS, Stutz A. Activation and regulation of the inflammasomes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13(6):397–411. doi: 10.1038/nri3452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schroder K, Tschopp J. The inflammasomes. Cell. 2010;140(6):821–832. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bauernfeind FG, Horvath G, Stutz A, et al. Cutting edge: NF-κB activating pattern recognition and cytokine receptors license NLRP3 inflammasome activation by regulating NLRP3 expression. J Immunol. 2009;183(2):787–791. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hattar K, Savai R, Subtil FS, et al. Endotoxin induces proliferation of NSCLC in vitro and in vivo: role of COX-2 and EGFR activation. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2013;62(2):309–320. doi: 10.1007/s00262-012-1341-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Melkamu T, Qian X, Upadhyaya P, et al. Lipopolysaccharide enhances mouse lung tumorigenesis: a model for inflammation-driven lung cancer. Vet Pathol. 2013;50(5):895–902. doi: 10.1177/0300985813476061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Y, Tu Q, Yan W, et al. CXC195 suppresses proliferation and inflammatory response in LPS-induced human hepatocellular carcinoma cells via regulating TLR4-MyD88-TAK1-mediated NF-κB and MAPK pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;456(1):373–379. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.11.090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang H, Wang B, Wang T, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 prompts human breast cancer cells invasiveness via lipopolysaccharide stimulation and is overexpressed in patients with lymph node metastasis. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e109980. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li S, Xu X, Jiang M, et al. Lipopolysaccharide induces inflammation and facilitates lung metastasis in a breast cancer model via the prostaglandin E2-EP2 pathway. Mol Med Rep. 2015;11(6):4454–4462. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.3258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gökyildirim Mira Y, Grandel U, Hattar K, et al. Targeting CREB-binding protein overrides LPS induced radioresistance in non-small cell lung cancer cell lines. Oncotarget. 2018;9(48):28976–28988. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.25665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang MY, Tu CE, Wang SC, et al. Corylin inhibits LPS-induced inflammatory response and attenuates the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in microglia. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2018;18(1):221. doi: 10.1186/s12906-018-2287-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qiao Y, Wang P, Qi J, et al. TLR-induced NF-κB activation regulates NLRP3 expression in murine macrophages. FEBS Lett. 2012;586(7):1022–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.02.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grishman EK, White PC, Savani RC. Toll-like receptors, the NLRP3 inflammasome, and interleukin-1β in the development and progression of type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Res. 2012;71(6):626–632. doi: 10.1038/pr.2012.24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vasconcelos MA, Royo VA, Ferreira DS, et al. In vivo analgesic and anti-inflammatory activities of ursolic acid and oleanoic acid from Miconia albicans (Melastomataceae). Z Naturforsch C. 2006;61(7–8):477–482. doi: 10.1515/znc-2006-7-803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kurek A, Grudniak AM, Szwed M, et al. Oleanolic acid and ursolic acid affect peptidoglycan metabolism in Listeria monocytogenes. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2010;97(1):61–68. doi: 10.1007/s10482-009-9388-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fan Y, Mao R, Yang J. NF-κB and STAT3 signaling pathways collaboratively link inflammation to cancer. Protein Cell. 2013;4(3):176–185. doi: 10.1007/s13238-013-2084-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prasad S, Ravindran J, Aggarwal BB. NF-κB and cancer: how intimate is this relationship. Mol Cell Biochem. 2010;336(1–2):25–37. doi: 10.1007/s11010-009-0267-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luo ZL, Ren JD, Huang Z, et al. The role of exogenous hydrogen sulfide in free fatty acids induced inflammation in macrophages. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;42(4):1635–1644. doi: 10.1159/000479405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rathinam VA, Vanaja SK, Fitzgerald KA. Regulation of inflammasome signaling. Nat Immunol. 2012;13(4):333–342. doi: 10.1038/ni.2237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoesel B, Schmid JA. The complexity of NF-κB signaling in inflammation and cancer. Mol Cancer. 2013;12:86. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-12-86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]