Abstract

Youth football helmet testing standards have served to largely eliminate catastrophic head injury from the sport. These standards, though, do not presently consider concussion and do not offer consumers the capacity to differentiate the impact performance of youth football helmets. This study adapted the previously developed Summation of Tests for the Analysis of Risk (STAR) equation for youth football helmet assessment. This adaptation made use of a youth-specific testing surrogate, on-field data collected from youth football players, and a concussion risk function developed for youth athletes. Each helmet is subjected to 48 laboratory impacts across 12 impact conditions. Peak linear head acceleration and peak rotational head acceleration values from each laboratory impact are aggregated into a single STAR value that combines player exposure and risk of concussion. This single value can provide consumers with valuable information regarding the relative performance of youth football helmets.

Keywords: Biomechanics, concussion, injury risk, impact

INTRODUCTION

It has been estimated that as many as 1.9 million sports-related concussions occur annually in the United States among youth athletes.3 Football has received much public scrutiny due to its high incidence of concussion at all levels of play, with some researchers even advocating for the elimination of tackle football among youth athletes.6, 13, 42 Some research has posited that exposure to repetitive subconcussive head impacts may lead to adverse neurocognitive changes.21, 22, 25 Limiting exposure to head impacts represents a crucial component of reducing concussion incidence in football, but the development of improved helmet protection can also mitigate injury.11 Youth athletes represent a vulnerable population as their continued development through puberty and adolescence may be affected differently by a concussion or repetitive head impact exposure than an adult.18, 23, 43, 52

Youth and varsity football helmets are currently held to the same certification standard and are designed similarly as a result. Matched model helmets, for example the Riddell Speed varsity helmet and Riddell Speed youth helmet feature the same interior padding, with the only design difference that exists between the youth and varsity model being the shell material, with the varsity helmet manufactured from polycarbonate and the youth helmet manufactured from acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) plastic.44 It should be noted that ABS is lighter and less expensive than polycarbonate. This difference in shell material has been shown to not have an effect on impact performance, as the helmet padding serves as the primary means of attenuating impact energy.51

Currently, all football helmets are certified by the National Operating Committee on Standards for Athletic Equipment (NOCSAE).37 This standard sought to limit catastrophic head injuries, such as skull fracture, in football and has succeeded in that regard.33 A youth-specific testing protocol has recently been proposed, which will assess youth football helmets separately from adult football helmets. Further, NOCSAE certification represents a pass/fail threshold, which does not provide information to consumers about the relative helmet performance. While all helmets that meet NOCSAE’s performance criteria are given a seal of approval, some helmets attenuate impacts more effectively than others.16

The Summation of Tests for the Analysis of Risk (STAR) methodology was originally developed as an evaluation tool to augment the existing certification standards by providing consumers with data about relative helmet performance. All STAR methodologies are predicated on two fundamental principles.2, 46, 53 The first is that helmets that reduce linear and rotational acceleration will also decrease the risk of concussion. Although all current head injury standards are based solely on linear acceleration, all head impacts have a rotational component, and both linear and rotational kinematics should be considered in determining injury risk.35, 36, 49, 58 The second principle is that the weighting of laboratory tests is based on how frequently a youth football player would experience a similar impact.

The purpose of this study was to develop a youth-specific football helmet testing protocol using data collected directly from youth football players. We accomplished this by adapting the STAR methodology for the evaluation of youth football helmets in managing concussion risk. This evaluation system considered real-world youth head impact exposure data and youth-specific concussion risk. These data consist of head impact exposure profiles and concussive injury risk. The safety certification provided by NOCSAE is meant to be augmented by the results from STAR testing to provide consumers with a complete perspective on a helmet’s safety.

METHODS

Youth Summation of Tests for the Analysis of Risk (Youth STAR)

Youth STAR is predicated on relating head impact exposure and head impact risk into a single metric to differentiate the performance of football helmets (Equation 1).2, 46, 54 Exposure, E, is a function of impact location, L, and velocity, V, while risk of concussion, R, is a function of peak linear head acceleration, a, and peak rotational head acceleration, α. Exposure and risk are specific to each sport and population assessed. Three impact velocities were used to represent some of the more severe head impacts a youth football player may experience on the field. The desired on-field acceleration percentiles to simulate in the impact testing were the 80th, 95th, and 99th percentiles.

| (1) |

Risk of concussion was assessed using a youth-specific risk function.5 This risk function relates peak linear head acceleration (PLA) and peak rotational head acceleration (PRA) into a single metric (Equation 2) that is then related to injury risk (Equation 3). Risk was mapped using a log-normal distribution, which does not have a simple solution due to the presence of the error function (erf), but it can be computed in a variety of software programs (MATLAB: logncdf; Microsoft Excel: lognorm.dist; R: plnorm). This risk function was developed from head impact data collected from youth football players who sustained a medically-diagnosed concussion and was designed to be used to assess the risk of single head impacts.

| (2) |

| (3) |

The STAR system tested each helmet model twice at each of the three impact velocities and four locations (front, front boss, back, and side). Two samples of each helmet model were used, for a total of 48 tests per helmet model. Peak linear and rotational head acceleration values were averaged for each impact velocity-location configuration. From this average test data, an overall STAR value may be computed for a given helmet model.

Mapping of On-Field Exposure

On-field head impact exposure consists of impact frequency (count), severity, and location. On-field data were collected from male youth football players, ages 9 to 14, wearing youth helmets as part of a larger study. All athletes received helmets which were outfitted with helmet-mounted accelerometer arrays (Head Impact Telemetry System, Simbex, Lebanon, NH). The study was approved by the Virginia Tech Institutional Review Board. The youth athletes provided verbal assent and their parents/guardians provided written consent for participation in the on-field study.

In considering on-field head impact severity, bivariate empirical cumulative distribution functions (CDF) of linear and rotational acceleration were determined from a subset of the athletes who participated in the larger study. For all games and practices, linear and rotational acceleration data were collected for each head impact with a resultant acceleration exceeding the 10 g threshold. Data were collected from 38 youth players between the ages of 10 and 12 wearing Riddell Speed youth helmets. STAR impact conditions were used to produce linear and rotational head accelerations for the youth surrogate equipped with a Riddell Speed youth helmet. Tests were conducted at each impact location for velocities ranging from 1.9 to 6.2 m/s. Two trials at each impact location-velocity combination were conducted and then results were averaged across impact locations. The bivariate CDFs were used to relate measured laboratory accelerations for each velocity to the desired on-field acceleration percentiles.

Exposure weightings for each impact velocity were initially set based on the desired on-field percentiles (80th, 95th, and 99th). Head impact data from 56 youth player-seasons were used to determine the average number of head impacts experienced during a single season of youth football. These athletes were between the ages of 10 and 12 and had participated in at least 75% of their team’s sessions for the season. It should be noted that a subset of the sample of 38 youth athletes aged 10 to 12 wearing Riddell Speed youth helmets were a part of this sample of 56 (i.e. those that also met the participation threshold). Head impact exposure between individuals can vary considerably and limiting the group of athletes considered to only those who participated in most of the season served as a means of capturing a better representation of youth football player head impact exposure. Five percent of head impacts exceed the 95th percentile and were attributed to the highest impact velocity, 15% of head impacts occur between the 80th and 95th percentile of head impacts and were attributed to the middle impact velocity, and the remaining 80% were attributed to the lowest impact velocity. These exposure weightings were equally distributed among the four impact locations.

The STAR methodology is predicated on weighting impacts based on on-field data. These on-field data underpin our protocol and analysis, but we also know that the head-neck assembly responds differently for each location-velocity combination and using equivalent exposure weightings among the different locations has the potential to underweight a location. To avoid the potential of overweighting or underweighting specific location-velocity combinations, the results from laboratory testing were averaged with the corresponding on-field data to develop the final exposure weightings. The determination of these two exposure weighting systems is described below.

Impact tests with a vinyl-nitrile disc (40 mm thickness VN600 foam) on a bare headform were conducted to determine how each location’s exposure needed to be scaled in order to contribute 25% towards the overall STAR value. These bare headform tests represent a helmet that offers the same padding properties at all locations. Four trials at each impact location-velocity combination were conducted, with the peak linear and rotational head acceleration values averaged. These average acceleration values were used to generate risk values and resulting STAR values using the initial exposure weightings. Each location’s contribution to the overall STAR value was summed across velocities and then normalized to achieve the desired 25% contribution of each location to the overall STAR value. A unique normalization factor was generated for each location. These factors were applied to the exposure weightings to generate a modified exposure mapping profile, which varied by both location and velocity.

Azimuth angles for each head impact were used to assign the on-field impacts to laboratory impact locations. Azimuth angles were defined as the angle from the positive X-axis within the X-Y plane. Elevation angles were defined as the angle from the X-Y plane. All measurements were made using the SAE J211 coordinate system in relation to a “zero” condition in which the headform was in a position of 0° Y and Z-axis rotation and the median (midsagittal) and basic (transverse) plane intersection of the headform was aligned with the center of the impactor.1 The front impact location was defined from an azimuth angle from 0 degrees to 33.75 degrees, the front boss location from 33.75 degrees to 83.75 degrees, the side location from 83.75 degrees to 140 degrees, and the back location from 140 degrees to 180 degrees. To map the entire head, the equivalent negative angles corresponded to the same impact locations. The proportion of impacts that occurred at each impact location was then computed. This proportion, in conjunction with the average total number of head impacts and the percentiles associated with the three impact velocities, was used to determine on-field exposure weightings.

Development of Youth Surrogate

The previously-developed adult surrogate that has been used for evaluating hockey helmets was adapted in order to have a representative youth surrogate for assessing youth football helmets.46 The surrogate consists of a head-neck assembly mounted on a sliding mass which simulates the effective mass of a torso. The masses and dimensions for these surrogate components were based on a 50th percentile adult male. For this analysis, the desired anthropometry to model was that of a 50th percentile 10–12 year old male. The head, neck, and sliding mass were modified from the adult surrogate in order to effectively represent a youth male (Table 1).

Table 1:

Representative masses of the adult and youth surrogates. The adult body mass is based off the 50th percentile Hybrid III dummy and the youth body mass is the equivalent of an 11 or 12 year old male. Each body mass is scaled to give a sliding mass estimate of the effective upper torso mass. The head circumference, head mass, and neck size are based off the specifications for the corresponding components of each surrogate.

| Adult Surrogate | Youth Surrogate | |

|---|---|---|

| Simulated Body Mass (kg) | 77.7 | 38.1 |

| Head Circumference (cm) | 57.6 | 53.4 |

| Head Mass (kg) | 4.9 | 4.12 |

| Neck Mass (kg) | 1.54 | 0.91 |

| Sliding Mass (kg) | 16 | 8 |

The human head is more than 90% of its full size by the time an individual reaches the age of five and grows gradually to full size between the ages of 10 and 16.17, 38 This difference in head size is equivalent to the difference between a large and medium sized helmets. A large helmet is intended for head circumferences between 55.9 and 59.7 cm, while a medium helmet is intended for circumferences between 51.8 cm and 55.9 cm. A 50th percentile 10 year old male has a head circumference of 53.5 cm and a 50th percentile 12 year old male has a head circumference of 54.3 cm, compared to a full grown 50th percentile male head circumference of 56.6 cm.34, 45 NOCSAE has different headforms, which are meant to be used with different sized helmets.37 The small, red NOCSAE headform with a circumference of 53.4 cm was chosen to emulate a youth player, as a majority of youth football players wear medium sized helmets. This headform has a mass of 4.12 kg.

Youth athletes have weaker necks than their adult counterparts.19, 24, 27, 30, 39 Scaling techniques have been used to develop Hybrid III necks for a 10 year old dummy and a 5th percentile female dummy.26 Though not explicitly defined, the stiffness and strength values for both the Hybrid III 5th percentile female neck and the Hybrid III 10 year old child neck are lower than that of the 50th percentile male neck.12, 57 The 10 year old neck is composed of molded butyl rubber with a center cable (mass = 0.80 kg), whereas the 5th percentile female neck is constructed of butyl rubber, segmented by aluminum discs with a center cable to limit strain on the rubber (mass = 0.91 kg). With the combination of appropriate mass, similar design to the Hybrid III 50th percentile neck (mass = 1.54 kg) (Table 1), and lower overall stiffness and strength that would be consistent with that of a child neck, the decision was made to proceed with the Hybrid III 5th percentile female neck for the child surrogate.26, 32

The head-neck assembly was mounted to a sliding mass that simulates the mass of the torso.41 The sliding torso mass of the adult surrogate is 16 kg and constructed of steel. Youth football players are between the ages of 6 and 14, representing a wide range of body masses. According to Center for Disease Control (CDC) growth charts, a 50th percentile 6 year old boy has a total body mass of 21.0 kg and a 50th percentile 14 year old boy has a total body mass of 51.0 kg. If you average these two extremes you get a mass of 36.0 kg. Applying the ratio of a 50th percentile male (77.7 kg) to the adult surrogate torso (16.0 kg), an 8 kg sliding mass was selected, which corresponds to a 38.9 kg body mass. This 38.9 kg simulated total body mass is representative of a 50th percentile male child between the ages of 11 and 12 (Table 1).29 To decrease the mass of the sliding table, the youth surrogate sliding mass was built out of aluminum rather than steel.

Impact Testing

An impact pendulum was used to simulate head impacts to evaluate youth football helmets. The pendulum arm, which is constructed of aluminum, is 190.5 cm in length, and has a 16.3 kg impacting mass. The pendulum arm has a total mass of 36.3 kg and mass moment of inertia of 72 kg-m2. A hemispherical nylon impactor face 20.3 cm in diameter, with a 12.7 cm radius of curvature, was used to represent a helmet shell geometry.54 This impacting face is rigid, as the use of a compliant impactor face has the potential to mask differences in helmet performance.47 The impact pendulum was used for impact testing as it has excellent repeatability and reproducibility compared to the pneumatic ram impactor that is traditionally used.41

The small, red NOCSAE headform was modified to fit a Hybrid III 5th percentile female neck. This head-neck assembly was then mounted on the 8 kg sliding mass. The complete youth surrogate was mounted to a linear slide table (Biokinetics, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada), which has 5 degrees of freedom to allow for control of helmet impact location. Each helmet was impacted at four impact locations: front, front boss, rear, and side (Table 2). These locations represented both centric and non-centric head impacts and assessed overall helmet performance (Figure 1). Helmet position on the headform was set with the NOCSAE nose gauge for a small headform before each test.

Table 2:

Pendulum impact testing locations. Measurements of Y and Z-position are relative to the basic plane of the NOCSAE headform. Positive rotation in the Y-axis is away from the pendulum, and positive rotation in the Z-axis is clockwise. The X-position is set such that the helmet contacts the impactor face when the pendulum arm is in a neutral vertical position for each location.

| Location | Y (cm) | Z (cm) | Rotation Y (deg) | Rotation Z (deg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Front | 0 | +5.2 | −20° | 0° |

| Front Boss | 0 | +2.2 | −25° | +67.5° |

| Side | −4 | +5.7 | −5° | −100° |

| Back | 0 | +3.7 | 0° | −180° |

Figure 1:

Impact locations clockwise from top left: front, front boss, side, back.

The headform was instrumented with 3 linear accelerometers (Endevco 7264B-2000, Meggitt Sensing Systems, Irvine, CA) and a triaxial angular rate sensor (ARS3 PRO-18K, DTS, Seal Beach, CA) at the headform center of gravity to measure linear acceleration and rotational velocity. Data were sampled at 20,000 Hz and filtered using a 4-pole phaseless Butterworth filter, with cutoff frequencies of 1650 Hz (CFC 1000) for linear data and 256 Hz (CFC 155) for angular rate data. The angular rate data were differentiated to compute measures of angular acceleration. Impact response was characterized by peak resultant linear acceleration and peak resultant rotational acceleration.

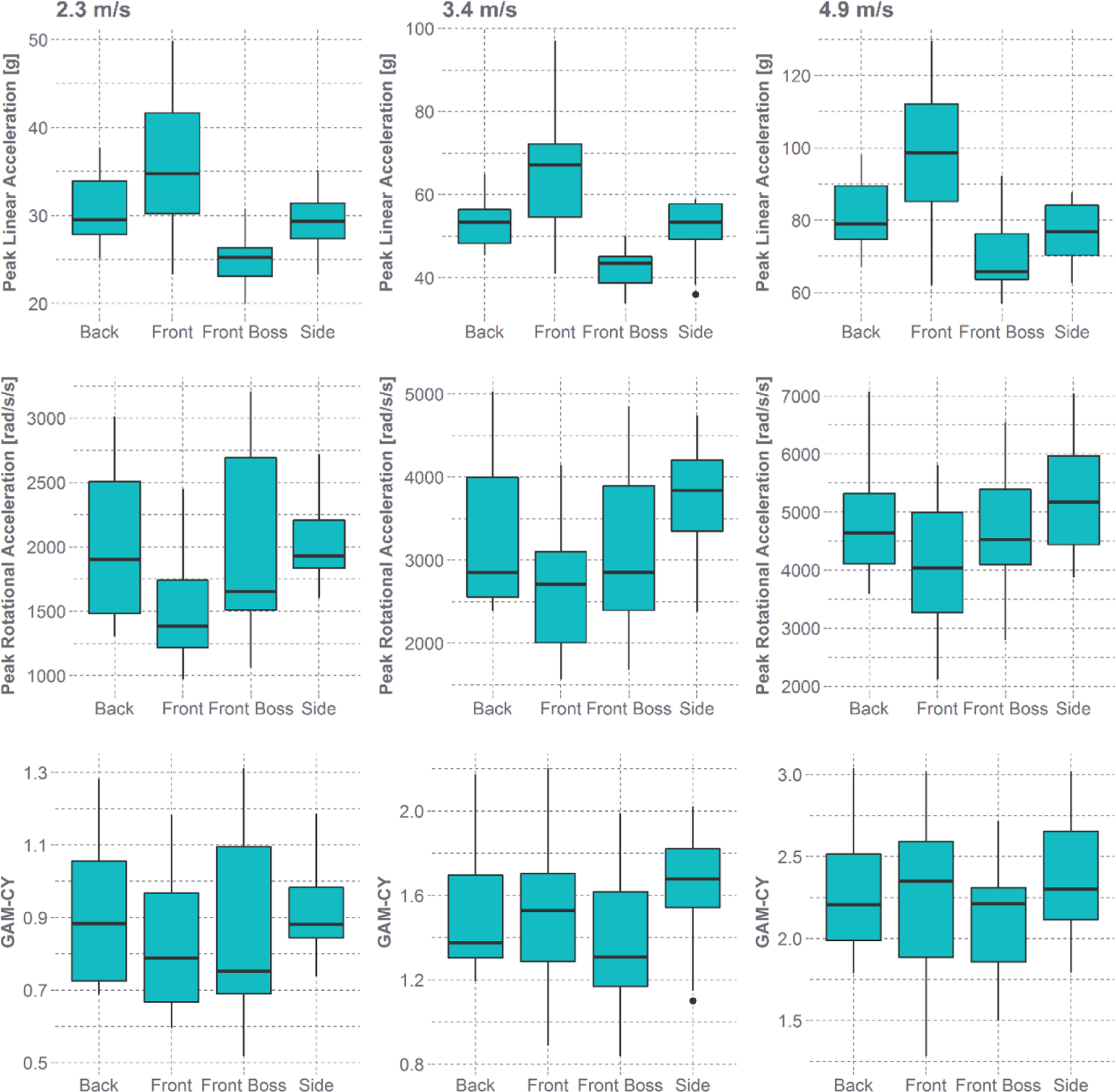

Differences in peak linear acceleration, peak rotational acceleration, and GAM-CY between impact locations and velocities were assessed using ANOVA (Tukey’s HSD post hoc) with a significance level set at α = 0.05.

RESULTS

Mapping of On-Field Exposure

A total of 7043 head impacts collected from the 38 youth football players aged 10–12 wearing Riddell Speed youth football helmets were included in this dataset to determine impact velocities. Impacts to the top of the head were not included in this analysis, as the STAR system does not assess impacts to the top of the head. The median head impact in this dataset was associated with a peak linear acceleration of 17.9 ± 1.6 g and a peak rotational acceleration of 954 ± 103 rad/s2, with 95th percentile accelerations of 48.8 ± 9.7 g and 2476 ± 641 rad/s2. Laboratory impact testing with a youth Riddell Speed helmet revealed that impact velocities of 2.3, 3.4, and 4.9 m/s were associated with the 80th, 95th, and 99th percentile head impacts that a youth player would experience (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mapping of on-field data to laboratory testing. Gray dots represent on-field head impacts experienced by youth football players. Orange dots represent the average kinematic response across all locations for laboratory pendulum impacts. These impacts represent the 80th, 95th, and 99th percentiles of on-field data and are associated with impact velocities of 2.3, 3.4, and 4.9 m/s.

The average 10–12 year old football player in our dataset experienced 214 ± 120 head impacts during a single season, with a range from 65 to 637 head impacts. Using this average number of head impacts and the percentiles associated with the testing velocities, initial exposure weightings were set as follows: 171.2 impacts for the 2.3 m/s velocity, 32.0 for the 3.4 m/s velocity, and 10.8 for the 4.9 m/s velocity. These numbers were then divided by 4 and allocated equally to each of the impact locations, so that initial weightings for each location were 42.8, 8.0, and 2.7 head impacts. The peak linear and rotational head acceleration values from the bare headform VN foam tests were used to determine the exposure weightings required for each location to contribute 25% towards the STAR value. From the on-field data, it was observed that 51.5% of impacts occurred at the front location, 15.5% at the front boss, 11.2% at the side, and 21.7% at the back location. These proportions were used to allocate the 214 total head impacts among the four locations to determine the on-field exposure weightings. These on-field exposure weightings were then averaged with the exposure weightings generated from the laboratory VN testing to determine the final exposure weightings for each location and velocity (Table 3).

Table 3:

Exposure weightings used for each location and impact velocity for Youth Football STAR. The average youth football player experiences 214 head impacts per season.

| Location | 2.3 m/s | 3.4 m/s | 4.9 m/s |

|---|---|---|---|

| Front | 112.6 | 21.1 | 7.1 |

| Front Boss | 22.3 | 4.2 | 1.4 |

| Side | 13.8 | 2.6 | 0.9 |

| Back | 22.4 | 4.2 | 1.4 |

Impact Testing Results

Impact performance was observed to vary by impact location and velocity (Figure 3). For peak linear acceleration, the front location was associated with higher values than all other locations for both the 3.4 m/s (p < 0.0001) and 4.9 m/s (p < 0.0001) test velocities. For peak rotational acceleration, the side location was associated with higher values than all other (p < 0.005). The front location was also associated with the lowest peak rotational acceleration of all locations (p < 0.042). For GAM-CY, the side location was associated with higher values than either the front or front boss location (p < 0.013).

Figure 3.

Impact distributions by location and velocity. The front location was associated with higher peak linear acceleration values than the other locations. The side location was associated with higher peak rotational acceleration and GAM-CY values.

Exemplar Calculation

For example, impacts at the front location at a velocity of 3.4 m/s for one helmet model resulted in an average peak linear acceleration value of 66.7 g and an average peak rotational value of 2758 rad/s2. These peak acceleration values were then used to determine a GAM-CY value (Equation 2), which was 1.45. Plugging this value into the youth concussion risk function (Equation 3) results in a risk value for this impact of 4.5%. This risk value is then multiplied by the exposure weighting for this location-velocity combination (8.0; Table 3) to produce that location-velocity combination’s contribution to the overall STAR value (0.36). This method is repeated for all location-velocity combinations, with individual values summed to compute the overall STAR value.

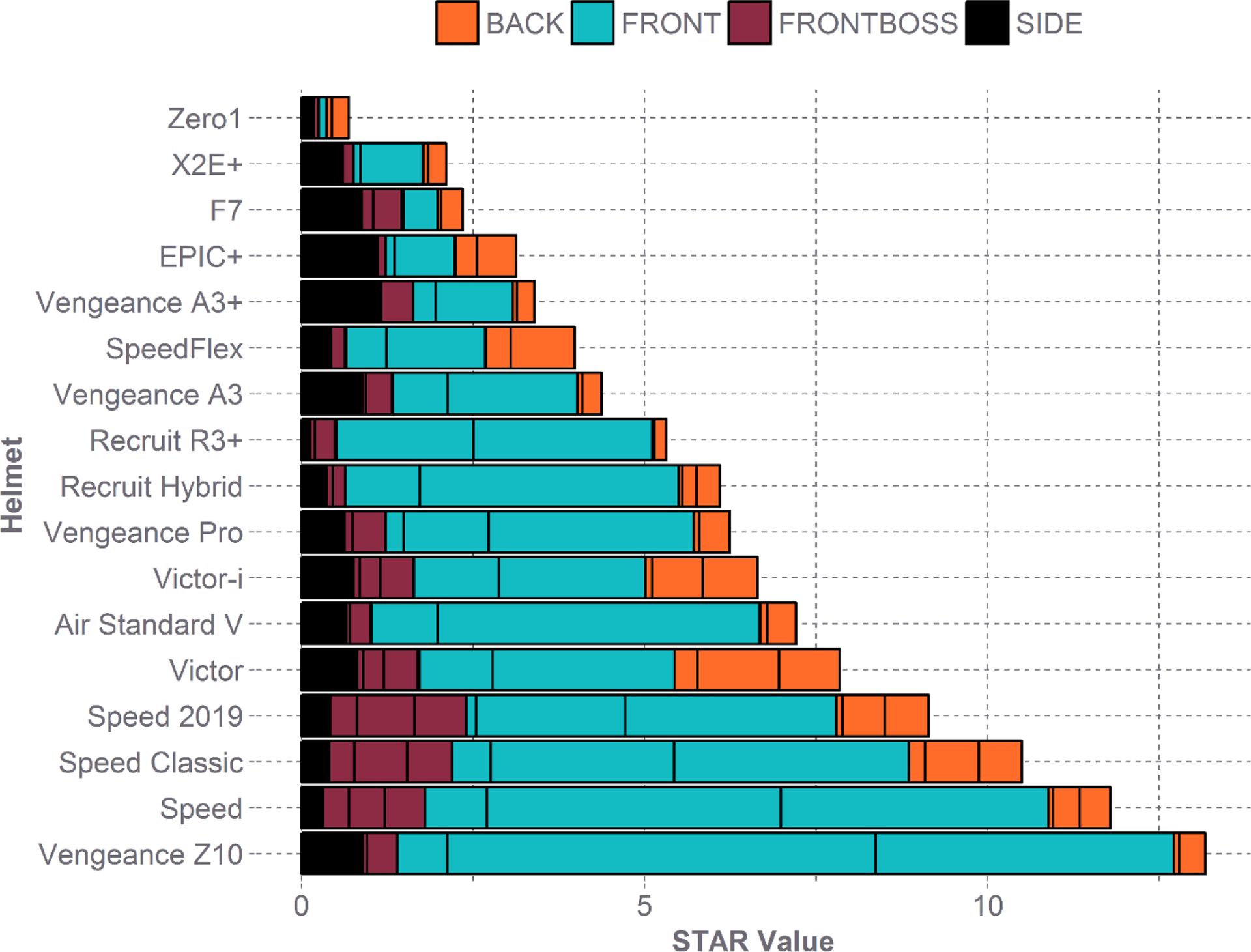

STAR Value Assessment

A total of 17 youth football helmet models are currently commercially available and were included in this analysis. Two samples of each helmet model were tested for a total of 34 helmet samples, each of which was tested 24 times, resulting in a total of 816 impact tests. Helmet performance varied by location and velocity across helmets. The Youth STAR equation was able to differentiate the performance of youth football helmets (Figure 4). A helmet with a lower STAR value would be associated with a greater ability to attenuate impact energy and limit energy transfer to the head.

Figure 4.

Summary of STAR Values by helmet. Helmet performance varied considerably, with the highest performing helmet having a STAR value of 0.69 and the lowest performing helmet having a STAR value of 13.17.

DISCUSSION

This study sought to develop the Youth Football STAR evaluation system, which considers the combined contribution of linear and rotational kinematics towards concussion, for assessing the relative performance of youth football helmets. Youth Football STAR is intended to only provide additional information for consumers regarding relative helmet performance and is not meant to replace the current NOCSAE certifying standard. NOCSAE’s impact testing standards currently serve as a pass/fail threshold for baseline helmet safety performance and has been instrumental in effectively eliminating catastrophic head injuries from the game of football. Youth Football STAR will serve as a supplement to the NOCSAE certification standard by informing consumers about relative helmet performance. Accordingly, only those football helmets that have the NOCSAE seal will ever be tested under the Youth Football STAR methodology. It should also be noted that helmet technology will never eliminate all head injuries and that participation in any sporting activity carries risk.

Youth STAR differs from the previously developed STAR evaluation system for varsity football helmets by considering exposure and risk for a youth player.53 The average athlete considered under Varsity STAR hits his head 420 times per season, compared to the average 10–12 year old youth football player modeled here (214 head impacts per season). There are known physical differences between adults and children that contribute towards an increased susceptibility of youth to concussion.27, 31 Thus, the Youth STAR methodology considers a concussion risk function that is youth-specific. For equivalent measures of peak linear acceleration and peak rotational acceleration, the youth concussion risk function results in higher probability of risk. Youth helmets are worn by those players below the age of 14, which essentially encompasses players below the high school level. Due to these population differences, there is a necessity to consider the populations separately and have different testing criteria.

The Youth STAR test surrogate was developed to model a youth player between the ages of 10 and 12. The impact durations ranged from 10 to 15 ms for tests conducted in this study. These values are similar to what has been reported in standard drop tests (8 −12 ms)48, laboratory recreations (15 ms)40, and on-field measurement (8–14 ms).9, 20 Furthermore, all the peak linear and rotational acceleration values of the impacts performed lie within the range of acceleration values observed through laboratory recreations of real world impacts56 as well as on-field data.4, 9, 14, 15, 28, 55 Further, the NOCSAE headform provides a more realistic helmet fit than the Hybrid III headform while providing a similar impact response.8, 10

The kinematic response to the same energy input varied by impact location (Figure 3). Using equal weighting between locations and not considering these response differences or the on-field data distributions would necessarily lead to underweighting or overweighting. The final exposure weightings (Table 3) resulted in varied performance among the youth helmet models tested (Figure 4). Those helmets that performed best were those that reduced kinematics at each location and velocity. For those helmets that were lower in performance, the front location was generally poor at reducing energy input into the head. By simply improving the front pad, these helmets could improve considerably. Helmet manufacturers can use these results to inform their design choices. They must also consider how those design changes might affect their performance in NOCSAE standards testing.

The Youth STAR methodology and results are based on aggregate data of head impact exposure and injury risk, and individual concussion risk may vary. It has recently been shown that concussion tolerance is individual-specific, with a subset of players who appear to be more vulnerable to concussion.50 While no helmet can completely protect an athlete, those helmets with higher star ratings are those that were observed to most effectively reduce head impact kinematics. Those helmets that best reduce head acceleration should result in fewer concussions across the playing population.

There are several limitations to note with this study. The on-field head impact measurements are associated with known error for individual acceleration measurements, though the effect of these errors is minimized when looking at distributions of head impact data.7 The concussion risk function for youth athletes used in this study has a limited dataset, though it considers the individualized nature of concussion.5 Head impact exposure weightings were not necessarily representative of actual on-field exposure profiles that a player would experience, but they do ensure that helmets which effectively reduce head acceleration at all locations are rewarded. The current STAR value thresholds may need to be updated in the future as safer helmet models, which offer enhanced impact protection, are developed.

CONCLUSIONS

An adapted version of the previously developed STAR methodology was presented for use with youth football helmets. A youth test surrogate with a smaller head, less stiff neck, and scaled sliding mass were used to represent a 10–12 year old boy. Head impact exposure and concussion risk values were derived from on-field head impact data from youth football players. Each impact location was weighted to contribute equally towards the overall STAR value. The STAR values for all currently available youth football helmets were presented, with most helmets offering excellent impact protection. This information will help inform consumers purchasing football helmets by directing them towards helmets that more effectively mitigate head acceleration.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01NS094410. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors also appreciate the support of the Institute for Critical Technology and Applied Science at Virginia Tech.

REFERENCES

- 1.SAE J211, Instrumentation for Impact Test - Part 1 - Electronic Instrumentation.

- 2.Bland ML, McNally C, Zuby DS, Mueller BC and Rowson S. Development of the STAR evaluation system for assessing bicycle helmet protective performance. Annals of biomedical engineering 1–11, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bryan MA, Rowhani-Rahbar A, Comstock RD and Rivara F. Sports-and recreation-related concussions in US youth. Pediatrics 138:e20154635, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campolettano ET, Gellner RA and Rowson S. High-magnitude head impact exposure in youth football. Journal of Neurosurgery: Pediatrics 20:604–612, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campolettano ET, Gellner RA, Smith EP, Bellamkonda S, Tierney CT, Crisco JJ, Jones DA, Kelley ME, Urban JE, Stitzel JD, Genemaras A, Beckwith JG, Greenwald RM, Maerlender AC, Brolinson PG, Duma SM and Rowson S. Development of a Concussion Risk Function for a Youth Population Using Head Linear and Rotational Acceleration. Ann Biomed Eng 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cantu RC and Hyman M. Concussions and our kids: America’s leading expert on how to protect young athletes and keep sports safe. 2012.

- 7.Cobb BR Laboratory and Field Studies in Sports-Related Brain Injury. 2015.

- 8.Cobb BR, MacAlister A, Young TJ, Kemper AR, Rowson S and Duma SM. Quantitative comparison of Hybrid III and National Operating Committee on Standards for Athletic Equipment headform shape characteristics and implications on football helmet fit. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part P: Journal of Sports Engineering and Technology 229:39–46, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cobb BR, Urban JE, Davenport EM, Rowson S, Duma SM, Maldjian JA, Whitlow CT, Powers AK and Stitzel JD. Head impact exposure in youth football: elementary school ages 9–12 years and the effect of practice structure. Ann Biomed Eng 41:2463–73, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cobb BR, Zadnik AM and Rowson S. Comparative analysis of helmeted impact response of Hybrid III and National Operating Committee on Standards for Athletic Equipment headforms. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part P: Journal of Sports Engineering and Technology 230:50–60, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crisco JJ and Greenwald RM. Let’s get the head further out of the game: a proposal for reducing brain injuries in helmeted contact sports. Curr Sports Med Rep 10:7–9, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Culver CC, Neathery RF and Mertz HJ. Mechanical necks with humanlike responses. Proceedings of the 16th Stapp Car Crash Conference SAE 720959:1972. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daneshvar DH, Nowinski CJ, McKee AC and Cantu RC. The epidemiology of sport-related concussion. Clin Sports Med 30:1–17, vii, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daniel RW, Rowson S and Duma SM. Head Impact Exposure in Youth Football. Ann Biomed Eng 40:976–981, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daniel RW, Rowson S and Duma SM. Head impact exposure in youth football: middle school ages 12–14 years. J Biomech Eng 136:094501, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duma SM, Rowson S, Cobb B, MacAllister A, Young T and Daniel R. Effectiveness of helmets in the reduction of sports-related concussions in youth. Institute of Medicine, Commissioned paper by the Committee on Sports-Related Concussion in Youth 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farkas LG, Posnick JC and Hreczko TM. Anthropometric growth study of the head. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal 29:303–308, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grady MF Concussion in the adolescent athlete. Current problems in pediatric and adolescent health care 40:154–169, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graham R, Rivara FP, Ford M and Spicer C. Sports-Related Concussion in Youth. National Research Council and Institute of Medicine Sports-Related Concussions in Youth: Improving the Science, Changing the Culture 309–330, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenwald RM, Gwin JT, Chu JJ and Crisco JJ. Head impact severity measures for evaluating mild traumatic brain injury risk exposure. Neurosurgery 62:789–98; discussion 798, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guskiewicz KM, Marshall SW, Bailes J, McCrea M, Cantu RC, Randolph C and Jordan BD. Association between recurrent concussion and late-life cognitive impairment in retired professional football players. Neurosurgery 57:719–26; discussion 719–26, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guskiewicz KM, Marshall SW, Bailes J, McCrea M, Harding HP Jr., Matthews A, Mihalik JR and Cantu RC. Recurrent concussion and risk of depression in retired professional football players. Med Sci Sports Exerc 39:903–9, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halstead ME and Walter KD. Sport-related concussion in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 126:597–615, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huelke DF An overview of anatomical considerations of infants and children in the adult world of automobile safety design. Annual Proceedings/Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine 42:93, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Janda DH, Bir CA and Cheney AL. An evaluation of the cumulative concussive effect of soccer heading in the youth population. Inj Control Saf Promot 9:25–31, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jarrett K, Salloum M, Wade B, Morgan C, Moss S and Zhao Y. Hybrid III Dummy Family Update-10 Year Old and Large Male. Injury Biomechanics Research 77–94, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karlin AM Concussion in the pediatric and adolescent population:“different population, different concerns”. PM&R 3:S369–S379, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelley ME, Urban JE, Miller LE, Jones DA, Espeland MA, Davenport EM, Whitlow CT, Maldjian JA and Stitzel JD. Head Impact Exposure in Youth Football: Comparing Age-and Weight-Based Levels of Play. Journal of Neurotrauma, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuczmarski RJ CDC growth charts; United States. 2000. [PubMed]

- 30.Meehan WP 3rd, Taylor AM and Proctor M. The pediatric athlete: younger athletes with sport-related concussion. Clin Sports Med 30:133–44, x, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meehan WP, Taylor AM and Proctor M. The pediatric athlete: younger athletes with sport-related concussion. Clinics in sports medicine 30:133–144, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mertz H, Irwin A, Melvin J, Stanaker R and Beebe M. Size, weight and biomechanical impact response requirements for adult size small female and large male dummies. 1989.

- 33.Mertz HJ, Prasad P and Nusholtz G. Head injury risk assessment for forehead impacts. 1996.

- 34.Nellhaus G Head circumference from birth to eighteen years: practical composite international and interracial graphs. Pediatrics 41:106–114, 1968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Newman JA A generalized acceleration model for brain injury threshold (GAMBIT). Proceedings of International IRCOBI Conference, 1986 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Newman JA, Barr C, Beusenberg MC, Fournier E, Shewchenko N, Welbourne E and Withnall C. A new biomechanical assessment of mild traumatic brain injury. Part 2: results and conclusions. Proceedings of the International Research Conference on the Biomechanics of Impacts (IRCOBI) 223–230, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 37.NOCSAE. Standard Performance Specification for Newly Manufactured Football Helmets. 2017.

- 38.Olvey SE, Trammell TR and Mellor A. Recommended standards for helmet design in children based on anthropometric and head mass measurements in 223 children ages six to seventeen. 2006.

- 39.Ommaya AK, Goldsmith W and Thibault L. Biomechanics and neuropathology of adult and paediatric head injury. Br J Neurosurg 16:220–42, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pellman EJ, Viano DC, Tucker AM, Casson IR and Waeckerle JF. Concussion in professional football: reconstruction of game impacts and injuries. Neurosurgery 53:799–812; discussion 812–4, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pellman EJ, Viano DC, Withnall C, Shewchenko N, Bir CA and Halstead PD. Concussion in professional football: helmet testing to assess impact performance--part 11. Neurosurgery 58:78–96; discussion 78–96, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pfister T, Pfister K, Hagel B, Ghali WA and Ronksley PE. The incidence of concussion in youth sports: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 50:292–297, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Refakis CA, Turner CD and Cahill PJ. Sports-related Concussion in Children and Adolescents. Clinical Spine Surgery, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Riddell. Riddell Speed Helmet. http://www.riddell.com/shop/on-field-equipment/helmets/riddell-speed-helmet.html

- 45.Roche AF, Mukherjee D, Guo S and Moore WM. Head circumference reference data: birth to 18 years. Pediatrics 79:706–712, 1987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rowson B, Rowson S and Duma SM. Hockey STAR: A Methodology for Assessing the Biomechanical Performance of Hockey Helmets. Annals of biomedical engineering 43:2429–2443, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rowson S, Daniel RW and Duma SM. Biomechanical performance of leather and modern football helmets. J Neurosurg 119:805–9, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rowson S and Duma SM. Development of the STAR Evaluation System for Football Helmets: Integrating Player Head Impact Exposure and Risk of Concussion. Ann Biomed Eng 39:2130–40, 2011.21553135 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rowson S and Duma SM. Brain injury prediction: assessing the combined probability of concussion using linear and rotational head acceleration. Ann Biomed Eng 41:873–82, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rowson S, Duma SM, Stemper BD, Shah A, Mihalik JP, Harezlak J, Riggen LD, Giza CC, DiFiori JP and Brooks A. Correlation of concussion symptom profile with head impact biomechanics: a case for individual-specific injury tolerance. Journal of neurotrauma 35:681–690, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sproule DW, Campolettano ET and Rowson S. Football helmet impact standards in relation to on-field impacts. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part P: Journal of Sports Engineering and Technology 231:317–323, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Terwilliger VK, Pratson L, Vaughan CG and Gioia GA. Additional post-concussion impact exposure may affect recovery in adolescent athletes. Journal of neurotrauma 33:761–765, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tyson A and Rowson S. Adult Football STAR Methodology Virginia Tech, Virginia Tech Helmet Lab, Blacksburg, VA: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tyson AM and Rowson S. Varsity Football Helmet STAR Protocol. 2018.

- 55.Urban JE, Davenport EM, Golman AJ, Maldjian JA, Whitlow CT, Powers AK and Stitzel JD. Head Impact Exposure in Youth Football: High School Ages 14 to 18 Years and Cumulative Impact Analysis. Ann Biomed Eng 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Viano DC, Casson IR and Pellman EJ. Concussion in professional football: biomechanics of the struck player--part 14. Neurosurgery 61:313–27; discussion 327–8, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yoganandan N, Arun MW and Pintar FA. Normalizing and scaling of data to derive human response corridors from impact tests. J Biomech 47:1749–56, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang L, Yang KH and King AI. A proposed injury threshold for mild traumatic brain injury. J Biomech Eng 126:226–36, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]