Abstract

Objective

RA is a progressive, chronic autoimmune disease. We summarize the impact of disease activity as measured by the DAS in 28 joints (DAS28-CRP scores) and pain on productivity and ability to work using the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment questionnaire (WPAI) scores, in addition to the impact of disease duration on the ability to work.

Methods

Data were drawn from the Burden of RA across Europe: a Socioeconomic Survey (BRASS), a European cross-sectional study in RA. Analyses explored associations between DAS28-CRP score and disease duration with stopping work because of RA, and regression analyses assessed impacts of pain and DAS28-CRP on early retirement and WPAI.

Results

Four hundred and seventy-six RA specialist clinicians provided information on 4079 adults with RA, of whom 2087 completed the patient survey. Severe disease activity was associated with higher rates of stopping work or early retirement attributable to RA (21%) vs moderate/mild disease (7%) or remission (8%). Work impairment was higher in severe (67%) or moderate RA (45%) compared with low disease activity [LDA (37%)] or remission (28%). Moreover, patients with severe (60%) or moderate pain (48%) experienced increased work impairment [mild (34%) or no pain (19%)]. Moderate to severe pain is significant in patients with LDA (35%) or remission (22%). A statistically significant association was found between severity, duration and pain vs work impairment, and between disease duration vs early retirement.

Conclusion

Results demonstrate the high burden of RA. Furthermore, subjective domains, such as pain, could be as important as objective measures of RA activity in affecting the ability to work.

Keywords: rheumatoid arthritis, quality of life, health economics, outcome measures, pain assessment, management

Key messages

Work impairment was high in patients with RA and in patients in remission.

Patients with RA and moderate or severe pain experienced increased levels of work impairment.

Pain was a substantial problem for patients with mild RA or those who were in remission.

Introduction

RA is a disabling and progressive chronic inflammatory, systemic autoimmune disease of unknown cause that carries a significant burden [1]. It is associated with persistent symmetric polyarthritis (synovitis) that affects mainly the small joints of the hands and feet. This leads to the erosion and destruction of joints, causing deformity and irreversible disability. About 40% of people with RA may have extra-articular manifestations, including rheumatoid nodules, interstitial lung disease and severe vasculitis, and they are at increased risk of malignancy, notably B cell lymphoma. The risk of premature mortality is increased owing to cardiovascular and lung disease [2].

RA is the commonest of the inflammatory arthritides. Its annual incidence is 20–50 per 100 000 population in European countries [3], and the estimated prevalence is 1–6 per 1000 for men and 3–12 per 1000 for women [4]. Approximately 2.3 million individuals are diagnosed with RA in Europe each year, generating annual direct and indirect management costs in excess of €45 billion [3, 5]. The advent of biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) has been associated with an increase in spending on drug treatment but lower spending on hospital costs in the past 20 years [6, 7], whereas non-medical costs borne by patients with RA include absence from work and informal care [8].

Pharmacological treatment is based on a treat-to-target strategy, with the objective of achieving sustained remission or low disease activity (LDA) by treatment with DMARDs [9, 10]. The systematic assessment of disease activity has refocused the aims of treatment from symptom control to arresting disease progression [10]. However, clinical trials show that no more than half of patients achieve an adequate response with an additional DMARD after failure of first-line treatment with MTX, and the figure is only 10–20% after failure of a first biological DMARD [11].

RA is associated with a substantial economic burden for patients, families and health-care systems [12]. It is also associated with limitation of activity that is comparable to that caused by other chronic conditions, such as diabetes and heart disease [13]. Historically, 30–40% of patients experience work disability 5 years after diagnosis and one-third of patients terminate employment prematurely [14–16].

This study evaluated the impact of RA activity and duration on economic costs and patients’ ability to remain in work, and the impact of pain associated with RA and disease activity on work impairment, in patients in the cross-sectional study Burden of RA across Europe: a Socioeconomic Survey (BRASS).

Methods

Data were extracted from the BRASS study, a societal perspective observational RA dataset across 10 European countries (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, UK, Denmark, Sweden, Hungary, Poland and Romania). Eligible patients were aged ≥18 years at consultation, diagnosed with RA for >12 months and being seen in specialist care for >6 months [17, 18].

All patient-level data were anonymized. Physicians were identified and recruited via a fieldwork agency, which collated all data for the study. The corresponding patients were invited to complete a linked questionnaire and were instructed to hand the form back in a sealed envelope or give it to an agent appointed by the physician. Physicians were recruited between April and June 2016; patient data were collected between June 2016 and May 2017.

Data collected from participating physicians included clinical economic and demographic information. Patient-reported data included indirect and direct non-medical resource use, adherence to treatment and health-related quality of life (obtained using the EuroQol EQ-5D-3L questionnaire [19]), among other patient-important outcomes. In the BRASS study, impairment caused by the patient’s RA was quantified using the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment questionnaire (WPAI). This tool is a ‘patient-reported quantitative assessment of the amount of absenteeism, presenteeism and daily activity impairment attributable to general health or a specific health problem’; it takes into account the proportion of time the patient is absent and the impact on their ability to perform their job [20, 21].

The association between disease duration, disease activity and the proportion of patients who had stopped working or retired early owing to RA was assessed by means of descriptive analyses, generalized linear models and a logistic regression model.

In descriptive analyses, disease duration was grouped into three arbitrary categories (1–5, 5–10 or 10+ years) to facilitate an evaluation of key endpoints among subgroups defined by disease duration and disease severity. Pain level was measured across four categories (none, mild, moderate or severe), which were defined by analgesic use and by interference in activities of daily living. Specifically, no pain = no analgesic use; mild pain = does not interfere with occupation or with activities of daily living but may require occasional non-narcotic analgesic; moderate pain = partial or occasional interference with occupation or activities of daily living and may involve use of non-narcotic medications; and severe pain = interferes with occupation or activities of daily living and requires frequent use of non-narcotic and narcotic medications. Disease activity, defined by DAS28-CRP as remission, mild/LDA, moderate or severe disease, was categorized as DAS in 28 joints (DAS28-CRP) ≤2.6, (>2.6 to ≤3.2), (>3.2 to ≤5.1) or >5.1, respectively, based on the most recent score reported by the physician in the previous 12 months. DAS was endorsed by the ACR as an appropriate measure for disease activity and remission in patients with RA [9].

Information was collected on demographics, health-related quality of life (EQ-5D) and clinical parameters including disease activity/severity, duration of disease, concomitant conditions and medications, and on costs associated with RA [18]. Costs were categorized into direct medical costs (DMC), direct non-medical costs (DnMC), indirect costs (IC) and total cost, and a combination of these. Direct medical costs covered predominantly health-care system perspective costs such as hospitalization, consultation, testing, surgical procedures and professional caregiver costs; the cost of self-medication was also reported in this category. Cost of medication would be considered a DMC, but in this case was excluded to avoid channelling bias owing to the high cost of medication for severe RA (which could mask the impact of other costs). Direct non-medical costs included costs such as travel expenditure, requirement for medical devices or aids and the cost of informal caregivers. Indirect costs looked at the cost of work time lost because of RA.

The relationship between disease severity (as measured by DAS28-CRP score), pain level and overall work impairment was initially assessed via a descriptive analysis and explored further using a generalized linear model. Pain level and severity were included as explanatory variables in the generalized linear model, against the overall work impairment outcome, while adjusting for age, sex and BMI.

In retired patients, this relationship was assessed by means of a logistic regression model with early retirement (retired early owing to RA vs retired for other reason) as the dependent (outcome) variable. The model evaluated the impact of disease duration (explanatory variable) on early retirement, adjusting for age, sex and BMI.

Model covariates were selected a priori and on the basis of established relationships with disease activity in RA based on empirical data. Education and socioeconomic status might represent unadjusted confounders, but the correlation between these variables and disease severity in RA might be influenced by unobservable characteristics, such as an individual’s time preference with regard to health and health investment.

A generalized linear model was constructed, which was specified using a log link and an inverse Gaussian family distribution, to investigate the association between disease duration, most recent DAS28-CRP score and total cost of patients excluding costs of conventional synthetic and biologic DMARDs. The model type and specification were chosen because they provided the best fit according to deviance residuals, Akaike information criterion and Bayesian information criterion. Disease duration and DAS28-CRP score were modelled as explanatory variables against the outcome total cost, adjusted for covariates including age, sex and BMI. This specification provided the optimal fit while maximizing residuals and offering parsimony in model design.

All analyses were performed in Stata v.16 (StataCorp 2019, Stata statistical software release 16; StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA).

This research project was approved by the Research Ethics Subcommittee of the Faculty of Health and Social Care within the University of Chester. The approval stipulated that the study was to be carried out in accordance with regional and relevant guidelines, and all subjects who participated provided informed consent.

Results

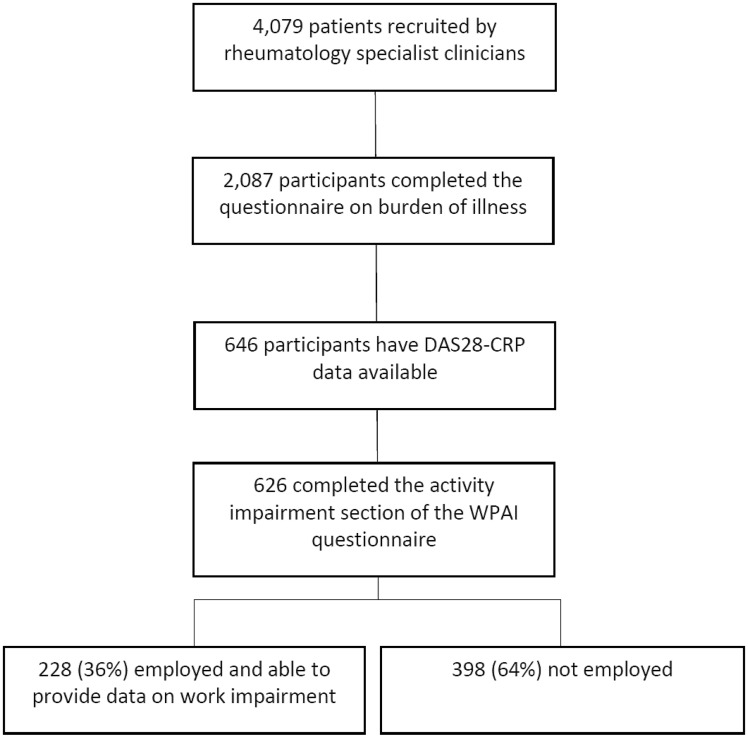

The flow of participants is summarized in Fig. 1. Four hundred and seventy-six RA specialist clinicians sequentially selected 4079 adult patients; of these, 2087 patients completed corresponding questionnaires about the burden of RA. This analysis included 646 patients who had completed a patient questionnaire and for whom the physician had provided information about disease activity as a DAS28-CRP. Of this subgroup, 626 completed the activity impairment section of the WPAI questionnaire, and of these, 228 (36%) were employed and therefore eligible to answer questions on work impairment. The remaining 20 patients did not complete the activity impairment section and were assumed to be missing at random.

Fig. 1.

Diagram of participant flow

In the cohort comprising the 626 individuals for whom data on activity impairment were available, age, disease duration and DAS28-CRP were 54.4 (14.0) years, 10.5 (9.7) years and 3.1 (1.2), respectively [mean (s.d.)]. In the subgroup of 228 who were employed and for whom work impairment data were obtained, age, disease duration and DAS28-CRP were 47.8 (10.8) years, 9.0 (8.3) years and 3.0 (1.2), respectively. The duration of RA and disease activity in these two cohorts were similar; the mean age of those in employment was lower, although no significant difference was observed between the two groups.

Costs

From the perspective of the RA-associated economic burden, both disease duration and DAS28-CRP score were predictive of resource use in addition to cost. Both disease duration and DAS28-CRP score had a statistically significant association with total cost (excluding treatment cost).

Outputs from the descriptive analysis are presented in Table 1. The DMC, DnMC, IC and total cost (excluding treatment costs) all increased with increasing RA severity, with the exception of IC for RA of >10 years duration, for which patients in remission or with mild RA had slightly higher costs than those with moderate RA. Among patients in remission or with mild RA, costs increased relatively more with RA >10 years duration compared with those with moderate or severe RA. IC accounted for a higher proportion of costs in this group compared with more severely affected patients, whereas costs were more evenly spread between categories for those with moderate RA, and DnMC were proportionately greater in patients with severe RA of >10 years duration.

Table 1.

RA severity, RA duration and costs

| Severity | Duration (years) | DMC excluding treatment (€) | DnMC (€) | IC (€) | Total cost excluding treatment (€) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Remission/mild | 1–5 | 1250 (252) | 251 (151) | 1223 (150) | 3040 (148) |

| 6–10 | 1630 (177) | 1291 (92) | 1639 (91) | 4560 (88) | |

| >10 | 2055 (236) | 2224 (122) | 4960 (118) | 9700 (117) | |

| Moderate | 1–5 | 1654 (148) | 1460 (79) | 2128 (78) | 5469 (76) |

| 6–10 | 2131 (131) | 2875 (66) | 2694 (64) | 8115 (63) | |

| >10 | 3311 (174) | 4256 (95) | 4700 (89) | 12 791 (88) | |

| Severe | 1–5 | 3494 (18) | 4918 (5) | 6351 (4) | 14 961 (4) |

| 6–10 | 4678 (18) | 4437 (10) | 3875 (10) | 13 498 (10) | |

| >10 | 7173 (32) | 11523 (14) | 6409 (13) | 27 512 (13) |

Costs are formatted as follows: cost (subgroup sample size).

DMC: direct medical costs; DnMC: direct non-medical costs; IC: indirect costs.

Costs by RA duration category for patients in remission or with mild RA are captured in Table 1. Costs in each category increased with the duration of RA, with the greatest incremental difference evident in IC in patients with >10 years duration. DnMC were low in patients with RA duration 1–5 years.

Table 1 also contains the costs by RA duration category for patients with moderate RA. All costs increased with duration of RA, with the greatest proportional increment occurring in DnMC between the 1–5 and 6–10 years categories.

Finally, in patients with severe RA (Table 1), incremental increase by duration category was apparent only for DMC. DnMC in patients with RA of >10 years duration far exceeded those associated with shorter duration RA. This was not true of IC, which were similar for RA of shortest and longest duration but lowest for 6–10 years duration. Consequently, total costs were higher for RA of 1–5 years duration than for 6–10 years duration, but still greatest for >10 years duration.

The incremental increase in cost by RA duration and disease severity is presented in Table 2. The mean (95% CI) per-patient total cost (excluding treatment) increased by €1075 (334, 1817) (P = 0.004) for a one unit increase in DAS28-CRP score (Table 2). A unit increment in disease duration of 1 year was associated with a rise in per-patient mean (95% CI) total cost (excluding treatment) of €360 (81, 639) (P = 0.012).

Table 2.

Incremental increase in cost by RA duration and severity

| Coefficient | ME | P-value | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost model | (€) | ||||

| Disease duration | 0.053 | 1075* | 0.004 | 0.017 | 0.088 |

| Change per unit increase in DAS28 | 0.157 | 360* | 0.004 | 0.050 | 0.264 |

| Age | 0.005 | NR | 0.364 | −0.006 | 0.017 |

| Sex (female) | −0.171 | NR | 0.268 | −0.472 | 0.131 |

| BMI | −0.001 | NR | 0.967 | −0.041 | 0.039 |

| Constant | 7.645 | NR | 0.000 | 6.740 | 8.550 |

| Overall work impairment model | (%) | ||||

| Change per unit increase in DAS28 | NR | 4.7* | 0.011 | 1.1 | 8.4 |

| Mild vs no pain | NR | 33.3* | 0.022 | 4.9 | 61.8 |

| Moderate vs no pain | NR | 43.4* | 0.004 | 13.6 | 73.2 |

| Severe vs no pain | NR | 45.0* | 0.009 | 11.2 | 78.9 |

Costs are formatted as follows: cost (subgroup sample size).

ME: marginal effect; NR: not reported.

P < 0.05.

Impairment while working

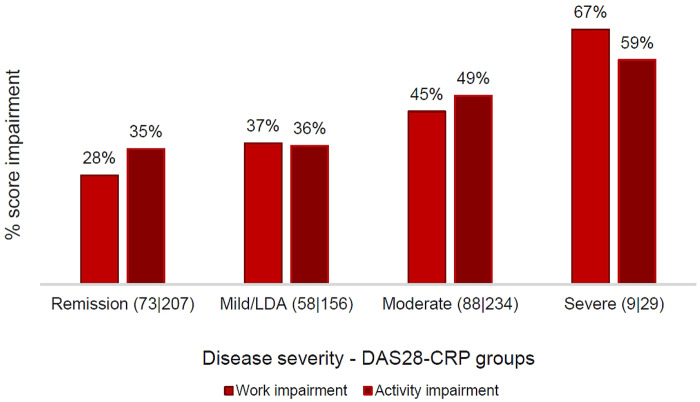

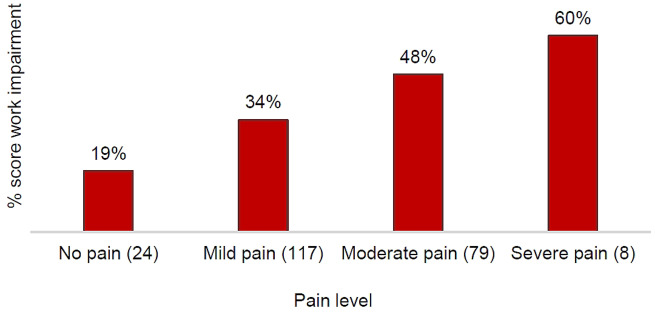

Analysis of the overall employed cohort (n = 228) showed that patients experienced increased levels of work impairment with greater levels of disease activity (Fig. 2) and pain level (Supplementary Fig. S1, available at Rheumatology Advances in Practice online). Pain level and DAS28-CRP score independently had a statistically significant association with work impairment (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Work impairment by DAS28-CRP severity

The number of patients is in parentheses, with format (work impairment | activity impairment). LDA: low disease activity.

Regression analysis was conducted on work impairment in the employed patients for whom this outcome was relevant. The average marginal effect of covariates was calculated with the confounders of age, sex, BMI and either DAS28-CRP or pain level held constant. A unit increase in DAS28 score meant an increase in work impairment of 4.7% (P = 0.011). Existence of mild, moderate or severe pain vs no pain increased impairment by 33.3, 43.4 and 45.0%, respectively (P < 0.05; Table 2).

Descriptive analysis also indicated that patients suffered greater activity impairment with moderate and severe RA, with little difference between patients in remission and those with active but mild RA (Fig. 2).

Early retirement

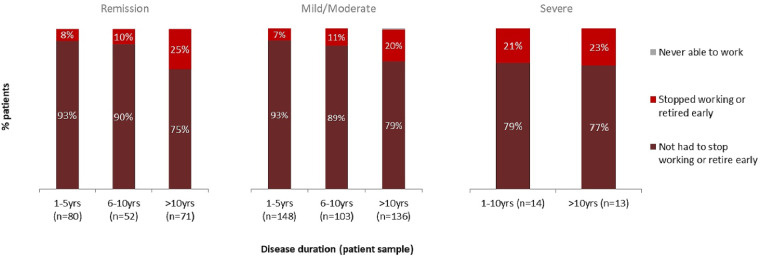

Descriptive analysis on 646 patients with a recent DAS28-CRP score and employment status information evaluated the probability for a patient to retire early or stop working. As RA duration increased, so did the proportion of patients who either stopped working or retired for reasons associated with their RA (Fig. 3). The correlation persisted in patients whose most recent DAS28-CRP score indicated that they were in remission and in those patients who were in mild/moderate disease activity categories. The number of patients with severe RA for whom recent DAS28-CRP scores were available was limited (n = 27); of these patients, the proportion of those who had stopped working or retired early was approximately one-fifth.

Fig. 3.

Work status of patients

The number of patients is in parentheses.

Of those in the BRASS cohort who had retired (n = 971), 23% had retired early because of RA. Logistic regression analysis showed the disease duration covariate to have an odds ratio of 1.043 (P < 0.001). The average marginal effect was 0.6% (P < 0.001) per year of disease and was non-linear over time; this yearly increase occurred until the disease duration was ∼50 years.

Chronic pain

The proportion of patients reported as currently suffering moderate to severe levels of pain attributable to RA increased as the severity of RA worsened (Fig. 4). However, even among patients in remission the prevalence of moderate/severe pain attributable to RA was 22%, and more than half reported mild pain. Almost all patients with moderate or severe RA reported pain, with the majority reporting moderate or severe pain.

Fig. 4.

Pain level by DAS28-CRP severity

LDA: low disease activity.

Discussion

Key results

This study describes the magnitude of non-treatment costs (direct and indirect) associated with the different levels of RA severity. DnMC were high regardless of RA duration, whereas IC were proportionately higher among those with less severe RA, perhaps reflecting the impact of RA on work time even at low levels of medical intervention. In addition to this, those with moderate or severe RA incurred other higher costs (e.g. DMC), which crowded out IC, thereby accounting for a larger proportion of overall costs. There was a trend for costs to increase with RA duration in patients with mild and moderately severe RA but not among those with severe RA. In terms of economic benefit outside of treatment costs, this would indicate the importance of current guidelines for the management of patients with RA, which focus on early intervention and a treat-to-target goal of remission or LDA [10]. The prevalence of pain, impairment of activity and work, and early retirement all increased with RA severity. These outcomes occurred and worsened in patients with long-standing RA; this suggests, indirectly, that treatment might not have achieved the targets identified in management guidelines.

Levels of work impairment were high in patients with moderate or severe RA (45 and 67%, respectively) but also in those with mild RA or who were in remission (37 and 28%, respectively). In addition, pain has been recognized as an independent factor that increases the level of work impairment. Patients with severe (60%) or moderate pain (48%) experienced increased levels of work impairment compared with those who had mild (34%) or no pain (19%). It should be noted that moderate to severe pain is a substantial problem even in patients with mild RA (prevalence 35%) or those who are in remission (22%).

Limitations

The patients in BRASS were recruited sequentially by their physicians. This process might select a population more likely to have co-morbidity or dissatisfaction with their treatment, including the possibility that pain might be more common, than in a population selected at random. However, patients treated with a DMARD do routinely see their physicians for therapeutic monitoring, and in that respect the BRASS population does reflect normal practice. The use of patient-reported pain and work impairment is a strength of this study but, although participants were asked specifically to describe pain attributable to RA, it is uncertain how well they could distinguish between pain associated with suboptimal control of RA and pain attributable to other causes, such as fibromyalgia [22]. Nevertheless, the presence of pain despite treatment suggests that current management strategies might not be meeting patients’ needs fully.

Such a high prevalence of pain, work impairment and early retirement suggests that, although patients in this cohort had relatively mild and not very active disease overall (as indicated by the mean DAS28-CRP of 3.0), the burden of RA is cumulative over time and not reflected solely in the current DAS.

In the logistic regression model of overall work impairment, the estimated coefficients might exhibit a bias owing to a collinear relationship between the change per unit increase in DAS28 score and pain level. Although collinearity might be present, studies have reported clinically significant pain amongst patients in remission (according to DAS28) and that pain level captures symptoms (such as fatigue) that are not associated with the DAS28 score. As model covariates were selected a priori and informed by established confounders, the presence of unobserved confounding cannot be ruled out.

Interpretation

Our findings suggest that the clinician’s targets for disease control should be pursued in light of the patient’s goals for their management. The ACR [9] and EULAR [10] guidelines recommend that treatment should be based on shared decision-making between the patient and the rheumatologist. The benefits of shared decision-making include alignment of patient and rheumatologist considerations and aims, improved patient adherence to medication and improved patient satisfaction with management decisions. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) can support this process by describing and quantifying the patient’s perspective on the impact of RA, and this is probably of particular importance when treatment does not achieve the target of remission or mild/LDA. However, utilization of patient-reported outcomes in daily clinical practice has generally been limited, suggesting that there is scope to improve the implementation of management guidelines. An analysis of the South Swedish Arthritis Treatment Group Register between 2005 and 2011 showed that patients’ subjective assessments of pain and disease activity, measured by a visual analog scale, more strongly predicted the impact of RA on work (absenteeism) than clinical measures such as swollen joint count, ESR and CRP [23]. We show that a formal measure, such as DAS28-CRP score, is correlated with WPAI, which measures absenteeism and also presenteeism and daily activity impairment. Together, our studies emphasize the importance of using both patient-reported outcomes and clinical measures to capture the impact of RA on work impairment adequately.

Generalizability

Integrating a systematic use of selected patient-reported outcomes in the assessment of RA patients could enhance the decision-making process between the patient and the health-care professional multidisciplinary team to strengthen and facilitate a holistic approach to patient care by monitoring a wider variety of relevant and patient-centric outcomes. Standardized, evidence-based recommendations and new technologies could help to facilitate this approach in daily clinical practice [24, 25]. Pain, fatigue, and physical and social function have been validated as patient-reported outcomes in research studies, and their potential role in clinical practice should be assessed as one approach to tackling the unmet needs identified in the present study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Steve Chaplin, HCD Economics, for writing services.

Funding: This work was supported by Eli Lilly and company.

Disclosure statement: J.-P.C., F.D.L., W.F. and I.K. are employees and stockholders of Eli Lilly and Company. The other authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Rheumatology Advances in Practice online.

References

- 1. Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D. et al. The global burden of rheumatoid arthritis: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1316–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cojocaru M, Cojocaru IM, Silosi I, Vrabie CD, Tanasescu R.. Extra-articular manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis. Maedica (Buchar) 2010;5:286–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lundkvist J, Kastäng F, Kobelt G.. The burden of rheumatoid arthritis and access to treatment: health burden and costs. Eur J Health Econ 2008;8:49–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.European Commission. Musculoskeletal problems and functional limitation. 2003. https://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_projects/2000/monitoring/fp_monitoring_2000_frep_01_en.pdf (14 August 2020, date last accessed).

- 5. Morse A. Services for people with rheumatoid arthritis. Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General. HC 823 Session 2008–2009. 15 July 2009. National Audit Office. Stationery Office. London, 2009. https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2009/07/0809823.pdf

- 6. Kirchhoff T, Ruof J, Mittendorf T. et al. Cost of illness in rheumatoid arthritis in Germany in 1997–98 and 2002: cost drivers and cost savings. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011;50:756–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Husberg M, Bernfort L, Hallert E, et al. Costs and disease activity in early rheumatoid arthritis in 1996–2000 and 2006–2011, improved outcome and shift in distribution of costs: a two-year follow-up. Scand J Rheumatol 2018;47:378–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Husberg M, Davidson T, Hallert E.. Non-medical costs during the first year after diagnosis in two cohorts of patients with early rheumatoid arthritis, enrolled 10 years apart. Clin Rheumatol 2017;36:499–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL. et al. American College of Rheumatology. 2015 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2016;68:1–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Smolen JS, Landewé R, Bijlsma J. et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:960–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Smolen JS, Aletaha D.. Rheumatoid arthritis therapy reappraisal: strategies, opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2015;11:276–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Boonen A, Severens JL.. The burden of illness of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol 2011;30: S3–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Perruccio AV, Power JD, Badley EM.. The relative impact of 13 chronic conditions across three different outcomes. J Epidemiol Community Health 2007;61:1056–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Young A, Dixey J, Cox N. et al. How does functional disability in early rheumatoid arthritis (RA) affect patients and their lives? Results of 5 years of follow-up in 732 patients from the Early RA Study (ERAS). Rheumatology 2000;39:603–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Young A, Dixey J, Kulinskaya E. et al. Which patients stop working because of rheumatoid arthritis? Results of five years' follow up in 732 patients from the Early RA Study (ERAS). Ann Rheum Dis 2002;61:335–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Scott DL, Smith C, Kingsley G.. What are the consequences of early rheumatoid arthritis for the individual? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2005;19:117–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Burke T, Jacob I, Andersen L. et al. An introduction to the burden of RA - a Socioeconomic Survey (BRASS). Rheumatology (Oxford) 2017;56:168. [Google Scholar]

- 18. O’Hara J, Rose A, Jacob I, Burke T, Walsh S.. The burden of rheumatoid arthritis across Europe: a socioeconomic survey (BRASS). University of Chester: National Rheumatoid Arthritis Society, 2017. https://www.nras.org.uk/publications/the-burden-of-rheumatoid-arthritis-across-europe-a-socioeconomic-survey-brass (14 August 2020, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 19.The EuroQol Group. EuroQol - a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990;16:199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM.. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics 1993;4:353–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Reilly MC. Development of the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) Questionnaire. Reilly Associates. 2008. http://www.reillyassociates.net/WPAI-Devolpment.doc (9 January 2018, date last accessed).

- 22. Duffield SJ, Miller N, Zhao S, Goodson NJ.. Concomitant fibromyalgia complicating chronic inflammatory arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2018;57:1453–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Olofsson T, Söderling JK, Gülfe A. et al. Patient-reported outcomes are more important than objective inflammatory markers for sick leave in biologics-treated patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2018;70:1712–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Oude Voshaar MAH, Das Gupta Z, Bijlsma JWJ. et al. International consortium for health outcome measurement set of outcomes that matter to people living with inflammatory arthritis: consensus from an international working group. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2019;71:1556–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fautrel B, Alten R, Kirkham B. et al. Call for action: how to improve use of patient-reported outcomes to guide clinical decision making in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int 2018;38:935–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.