Abstract

Since the detection of COVID-19 in December 2019, the rapid spread of the disease worldwide has led to a new pandemic, with the number of infected individuals and deaths rising daily. Early experience shows that it predominantly affects older age groups with children and young adults being generally more resilient to more severe disease.1, 2, 3 From a health standpoint, children and young people are less directly affected than adults and presentation of the disease has shown different characteristics. Nonetheless, COVID-19 has had severe repercussions on children and young people. These indirect, downstream implications should not be ignored. An understanding of the issues is essential for those who hope to advocate effectively for children to prevent irreversible damage to the adults of the future. This article reviews some of the evidence of harm to children that may accrue indirectly as a result of pandemics. It explores the physical and psychological effects, discusses the role of parenting and education, offering practical advice about how best to provide support as a healthcare professional.

Keywords: adverse childhood experience (ACE), children and young people, COVID-19, parenting, SARS-COV2, telemedicine

Physical health

Changes in health care delivery and prevention of infection

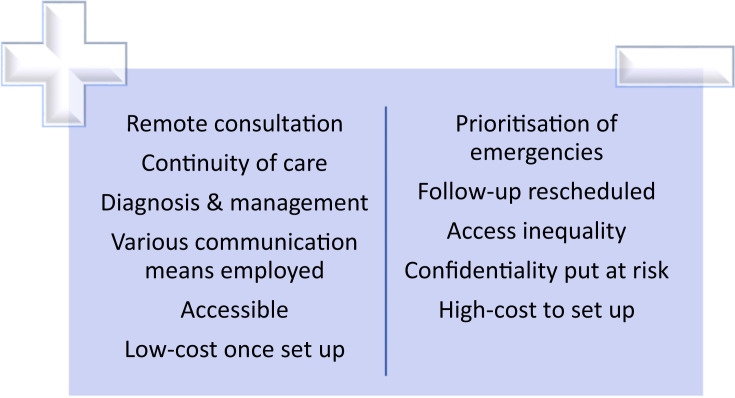

The use of telemedicine: one of the ‘positives’ to emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK has been a dramatic increase in the availability and use of remote consultations.4 Driven initially by a need to protect and safeguard patients and healthcare professionals, the early experiences have shown that many routine reviews and some acute consultations can be successfully managed remotely.

Telemedicine or telehealth is becoming the new norm and can be used as an alternative to face-to-face consultations, eliminating the risk of infection (Figure 1 ).5 Any technology available such as phone and texting, email, and video, has now been employed to be able to provide therapy. By being able to employ many different means of communication, it makes telemedicine available to a greater number of patients. Even so, there can still be inequalities in accessing healthcare as within different communities there is a difference in availability of communications means. It has been clear from early experience in the UK that there is a great difference in the availability of high quality internet connectivity between families which has limited the use of some approved, data-secure platforms such as Attend Anywhere. The issue of health disparities, the gap in access and quality of care are still present. Solutions for the NHS have not been cheap. However, in the longer term these may be cost effective and eliminate some expenses e.g. travel, parking for families.

Figure 1.

The advantages and disadvantages of telemedicine.

Some aspects of routine care for children have been hampered. The significant reduction in availability of lung function testing for children with chronic respiratory diseases is a concern. In some instances, these have been partially overcome with provision of home testing with either peak flow meters or portable spirometers which allow more nuanced care and advice to be given.6

Challenges to disease prevention – specific challenges in children: engaging the public in planning and decision making, together with educating parents and children efficiently, has proven useful when implementing public health strategies.7 Some strategies appear to have an evidence base. For instance it is suggested that social distancing might be more adhered to if public health officials portray it as an act of altruism, giving a sense of duty to protect the child's loves ones.8 The direct approach may also be helpful and has certainly been tried. For example, the Canadian Prime Minister specifically thanked children for their efforts which could only be accounted as an act to increase the feeling of social duty to the youth.9

The universal use of face masks and the inclusion of younger children within any guidance is still being debated. When it comes to children there are more issues to consider including the availability of masks of different sizes to fit well on the face as well as the risk of suffocation in children younger than two years.10 Additionally, when it comes to younger children, it is more challenging to persuade them not to take the mask off. Innovative ideas have started to emerge, with Disney designing fabric face masks with the children's favourite characters to help children in accepting to use them.11

Caring for children with chronic diseases and shielding

Whilst initial data does not suggest that children with comorbidities are at particularly increased risk of severe COVID-19 disease,12, 13, 14 the challenge of maintaining a good continuity of care for existing patients and adequate diagnostic care for children presenting for the first time remains.

Children with chronic diseases and their carers have been particularly anxious about the impact that COVID-19 could have on them. This can be partially resolved for many by maintaining communication with these families, providing reassurance, advising on hygiene measures, and educating on COVID-19. Where children fall outside clear guidelines, tailored and individualized plans offer reassurance for all of those involved with the provision of care.

At the start of this pandemic in the UK the advice given to the families with children with many chronic diseases was to shield the whole household to prevent the risk of severe illness. In hindsight, some of the advice was unduly cautious but faced with uncertainty public health authorities, paediatricians and primary care physicians erred on the side of caution. For some families, the increased anxiety may have longer term consequences. The act of shielding can have severe impacts on a child's physical and mental health. For example, going back to school could be beneficial for children with cerebral palsy or musculoskeletal problems as school provides developmental support and gives access to therapies.

As ongoing research suggests a low disease severity amongst the young1, 2, 3 and the negative effects of shielding, experts questioned whether shielding children with many comorbidities was ever justified. This led to the reformation of the strict guidelines. With social distancing rules being slowly lifted and school re-opening, the RCPCH has provided new guidelines for shielding.15

Acute care

One of the medical sectors highly affected by the pandemic is the Emergency Department (ED).16 Normally, in the UK the emergency services are unnecessarily overused, leading to overcrowding and stretching of resources particularly during weekends and evenings. However, regional data suggests that there was a decrease of more than 30% in the cases of children presenting to the paediatric ED by March 2020 and this decline in activity has been maintained into the summer. This has certainly helped to prevent services from being deluged and allowed time for new processes and health protection procedures to be put in place. Whilst this change in behaviour could discourage unnecessary attendance to ED, it could also put at greater risk children with serious pathologies that require treatment.

Safeguarding

In the UK, safeguarding has always been an important concern.17 During a time of a global pandemic, where focus is on the direct results of the disease, vulnerable children experiencing maltreatment and neglect at home are put on the side-line. Long home confinement, together with frustration, agitation, and aggression, creates opportunities to harm children. Moreover, the loss of the safety net provided by schools, social care and health professionals decreases the number of abuse cases reported. Without spotting narratives or signs of abuse, home becomes a very dangerous place for the vulnerable children.

Unfortunately, there is a trend of increasing incidences of domestic violence and calls to child support lines reported.18 Children and teenagers exposed to violence, either as witnesses or victims could experience detrimental effects on their physical and mental health.

Immunization delays

Incomplete immunization has always been a worrying issue and unfortunately, during a pandemic, this issue can be easily neglected. This could expose communities at risk of an outbreak of a vaccine-preventable disease. For this reason, the WHO have declared immunization as a core health service that should be safeguarded and conducted under safe conditions. Consequently, they have prepared documents that explain the reasoning behind this and respond to any questions the public or health authorities might have.19 , 20

Obesogenic behaviours in children

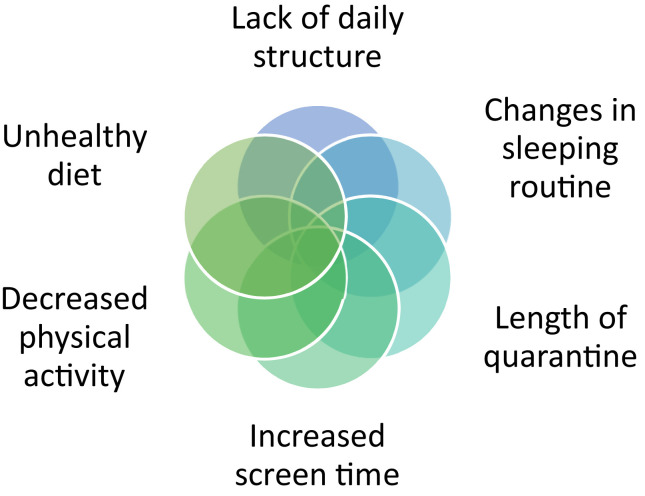

In recent years, weight gain during periods of school closure, especially during summer vacations, has been a worrying issue amongst the paediatric community.21 When comparing behaviours during summer and school season, accelerated weight gain is observed during the summer holidays.21 A school closure during a pandemic is not equivalent to summer vacations. Nonetheless, there are distinct similarities such as the lack of structure during the day, the increase in screen time and a change in sleeping routines (Figure 2 ). In fact, a small longitudinal observational study conducted in Verona Italy during this pandemic, has shown that the unfavourable trends in lifestyle discussed above, were observed amongst obese children and adolescents.22

Figure 2.

Factors encouraging obesogenic behaviours in children and young people.

The COVID-19 pandemic has further risk factors that might exacerbate the epidemic of childhood obesity.23 Firstly, as out-of-school time has increased more than a regular summertime, it has increased the period that children are exposed to obesogenic behaviours. Secondly, parents are stocking up shelves with highly processed and calorie dense food. This action is justified by the need to maintain food availability and minimise the number of trips outside. This, however, exposes children to higher calorie diets. Thirdly, social distancing and stay-at-home policies introduce the risk of decreasing opportunities for physical activity. School physical activities were removed, playgrounds could not be kept clean, parks closed their gates, community centres offering afterschool programs shut their doors. Children living in urban areas, confined within small apartments are at a greater risk of adopting a sedentary lifestyle. Lastly, there has been an increasing trend on the use of video games which counts as a sedentary activity and leads to excessive screen use.24

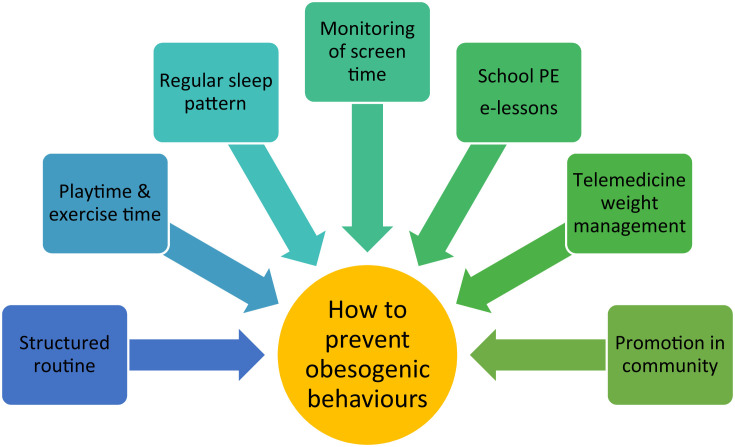

This obesogenic behaviour needs to be taken seriously and tackled as it could have profound consequences which are not easily reversible. Moreover, we should have in mind that adult obesity and its comorbidities are associated with COVID-19 mortality,25 which raises the question whether overweight or obese children will have more severe repercussions upon contracting COVID-19.

Therefore, there is a need to maintain a structured day routine for the children which includes playtime and exercise time, a restriction on calories, a regular sleep pattern and supervision of screen time (Figure 3 ).

Figure 3.

How to prevent obesogenic behaviours amongst children and young people.

The risk of malnourishment

Although emphasis is given to the obesogenic effects of the pandemic, there is also the issue of malnourishment as many students rely on school meals. In fact, school meals and snacks could represent up to two thirds of the nutritional needs in children in the USA.26 In addition to not receiving the appropriate nutrition through school, children could be exposed to cheaper, unhealthy food choices. In the UK a partial safety-net has been established and maintained over the summer period following a successful campaign by the English footballer, Marcus Rashford.26 This will offer some support to children who already received free school meals. However, not all children in the UK and many others worldwide will be protected. Insecurity over food availability causes long-term psychological and emotional harm to the children and parents.

Education

The challenges of school closure and the timing of going back

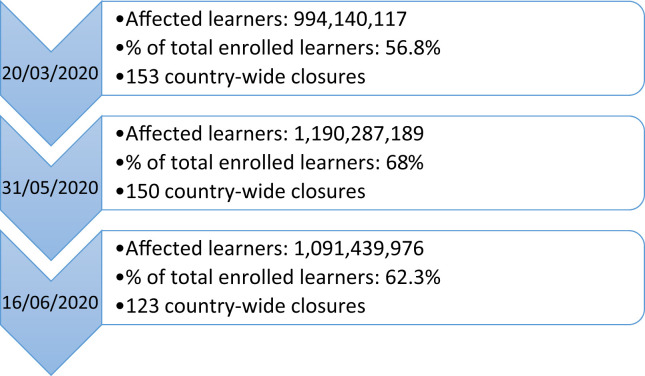

On Friday 20th March, schools across the UK closed stirring a wave of uncertainty around the country. Whilst the children of ‘key workers’ were allowed to remain in school, much formal education was halted and there was disruption to education and examinations for millions of children. UNESCO has provided statistics exploring the number of affected learners worldwide (Figure 4 ).27

Figure 4.

UNESCO data on affected schools and pupils worldwide.

A collaboration amongst WHO, UNICEF and IFRC has provided comprehensive guidance to help protect schools and children, with advice in the event of school closure and for schools that remained open.28 Important points in this guidance document are the emphasis given to a holistic approach towards children by tackling the negative impacts on both learning and wellbeing and to educate towards COVID-19 and its prevention. Even so, these guidelines can only be considered as checklists and tips for each government to use accordingly.

China provided a successful example of an emergency home schooling plan,29 where a virtual semester was delivered in a well organized manner through the internet and TV broadcasts, yielding satisfactory results. However, digital learning is an imperfect system that brings to the surface the inequalities caused by poverty and deprivation. Many children have had either limited, shared or no online access either as a result of a lack of equipment (laptops or tablets) or internet access. Some parents struggled with the provision of adequate supervision. This issue was significantly more challenging for parents with additional educational needs e.g. ADHD or learning difficulties, for those with many children of different ages and for those children who might have additional carer responsibilities. It was also much more difficult for parents who were being expected to work from home at the same time. The full effects of a temporary ‘pause’ in many children's education in the UK remain to be seen but the effects are likely to widen the gap between children from more deprived backgrounds.

Psychological impacts

Learning from previous pandemics

Since the beginning of the 21st century, there have been several major disease outbreaks including the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2003, the H1N1 influenza pandemic in 2009 and the Ebola in 2013. However, mental health research was largely overlooked. The absence of mental health services during previous pandemics increased the risk of psychological distress to those affected.30

There are variable psychological manifestations as a result of a pandemic. Early childhood trauma can affect a child in many ways.31 It can increase the risk of developing a mental illness and it can also delay developmental progress. Moreover, early childhood trauma in the form of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) can have profound effects that manifest in later life such as an increase in substance abuse and problems with relationships or education as well as increase the risk of chronic diseases such as asthma, obesity and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.32

About 30% of isolated or quarantined children during the H1N1 pandemic in the United States of America met the criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).33 This study noted the lack of professional psychological support to these children during or after the pandemic. Out of the much smaller percentage of children that did receive input from mental health services, the most common diagnoses were anxiety disorder and adjustment disorder. Moreover, the same study also showed that one quarter of parents would also fulfil the criteria for PTSD which shows that parental anxiety and mental health can be reflected upon other members of the family including the children.

Stressors

Events and conditions can have effects on our physical and mental health. These act as stressors or triggers and can predispose anyone, including children to adverse responses; either physical or psychological.

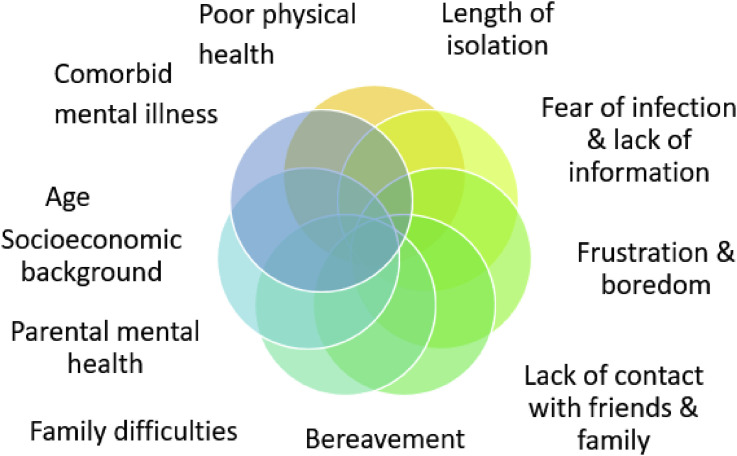

The stressors that could impact a child during a pandemic are shown in Figure 5 . The duration of the lockdown appears to be particularly important. Researchers have shown that the longer the quarantine, the higher the chances of mental health issues emerging in adults. It is unknown whether the same applies to children.8

Figure 5.

Stressors that could impact the mental health of children and young people.

Some children and young people (CYP) will be more vulnerable to the adverse consequence of any stressors and these pre-pandemic predictors should also be considered. In a child, such predictors could include the age of the child and a history of mental illness. There is a complex link between mental health and social background. Families with lower incomes face tough choices about how to cope with the day-to-day challenge of providing basic necessities (e.g. food, clothing and heating) and may be less able to give priority to the mental health of their children (or themselves).

When considering what can influence mental health, the link between physical and mental health should also be considered. The physical health of a child can be affected either directly or indirectly by COVID-19. This raises the question of how this could affect the psychological wellbeing too and if it would lead to a vicious cycle.

Management strategies

Telemedicine for mental health: the sudden advance in telemedicine in the UK has been one of the unexpected changes brought about by COVID-19. It has been helpful in maintaining some healthcare for physical ailments ranging from acute illness to review of children with chronic conditions like asthma, diabetes and cystic fibrosis. It can also be used for psychological counselling for parents or children. This can help children learn how to cope with mental health problems via professional help within the security of their own house.34 Telemedicine for mental health is already established in some countries. The psychological crisis intervention, is a multidisciplinary team program developed as a collaboration amongst a few Chinese hospitals that uses the internet to provide support.30

What else can be done?: telemedicine is most probably not sufficient in managing and providing for the mental health needs of the high numbers affected. When the already limited access to trained professionals is struck by a global pandemic, the shortage of professionals and paraprofessionals becomes noticeable and therefore the needs of the high number of patients are not met.35

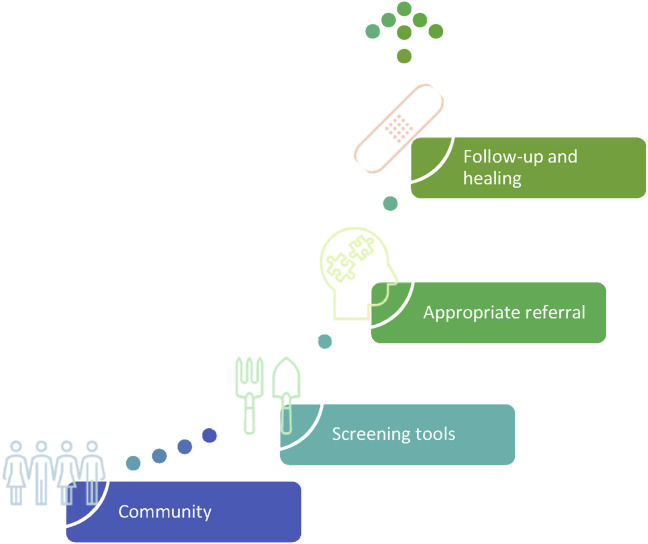

When dealing with mental health a hierarchal and stepwise approach that starts in the community is helpful (Figure 6 ). Integration of behavioural health disorder screening tools within the response of public health to a pandemic is crucial to cope with demand. These should recognize the importance of identifying the specific stressors and build on the epidemiological picture of each individual to identifying those CYP at greatest risk of suffering from psychological distress.36

Figure 6.

A stepwise approach to identify, diagnose, and manage mental health problems.

Following the correct identification of patients in the community, the next step involves an appropriate referral. Interventions can vary according to the individual's presentation and can include psychoeducation or prevention education. Any behavioural and psychological intervention should be based on the comprehensive assessment of that patient's risk factors.35 For instance, researchers have shown that specific patient populations such as the elderly and immigrant workers may require a tailored intervention.37 , 38 This hypothesis could therefore be stretched to children and teenagers as their needs are different to adults.

The rapid changes that both parents and children are forced to face and the uncertainty of an unpredictable future have been compared to the loss of normalcy and security that palliative care patients are faced with and paediatric palliative care teams may be well-placed to provide psychological support to families.39

Community organizations have a significant role to play in addressing mental health problems. They empower communities and provide tailored support. When this support comes from organizations which understand the community, the community's beliefs are embodied within the programs offered. It is therefore becoming obvious that best results will only be yielded if different bodies work together. This stresses how crucial it is to maintain good communication between community health services, primary and secondary care institutions. This is to ensure patients receive a timely diagnosis and better follow-up.35 Conversely, poor communication could delay meeting the needs of the patients.

The online world: the internet is a potentially useful tool for the provision of mental health support. There are a lot of reliable resources online that anyone could use effectively without being in direct contact with professionals. Large organizations such as UNICEF have provided online documents to help teenagers protect their mental health during the pandemic. Many books about the current pandemic and its psychological impact are being released electronically for free for the public.34 Likewise, online self-help interventions such as CBT for depression can be used by anyone experiencing such symptoms. This type of intervention and signposting of lower risk CYP and families to safe, well-constructed resources is highly efficient, allowing mental health professionals to focus more intensive interventions on higher risk individuals.

The online world is more easily accessible and much more appealing to older children and teenagers. As young people are becoming the experts of this virtual world, it is only logical to use social media for our benefit. Successful mental health campaigns in the past used hashtags on social media like Instagram and Twitter to increase awareness of mental health problems.40 With more bloggers and social media influencers talking about mental health, together with the use of hashtags, the societal benefits become apparent. A strong feeling of empowerment is built that helps combat the stigma of mental health. Moreover, there is a therapeutic benefit through the provision of information on how to find professional support or self-management strategies. Even though online gaming can have negative impacts on young people's physical health, during a period of home confinement, it provides a mean for friends to stay in contact. Both online gaming and the yet extensive use of social media have the potential of bringing people closer together and gives a feeling of solidarity.

Regarding young children, using online resources on their own might not be an easy task, although they are surprisingly becoming experts of the web too. Nonetheless, there are many resources designed with the purpose to explain the pandemic to children and alleviate their anxiety as well as promoting good hygiene. A good example is the collaboration of Sesame Street with Headspace, a mindfulness and meditation company, to create YouTube videos that help young children tackle stress and anxiety. Parents, carers, or older siblings could all help the young ones to access these resources.

The power of technology and the artificial world is becoming a turning point for societies today. Interestingly, an artificial intelligence program has been created with the purpose of identifying people with suicidal ideations via scanning their posts on specific social media platforms. Once identified, volunteers take appropriate steps to help these individuals. During a time of extensive home confinement, where the use of the web becomes even more prominent, such programs might again provide a service to society by identifying teenagers struggling with mental health.41

The power of arts and playing: healing through creative expression is a popular tool amongst child therapists and is has proven useful in previous pandemics too.31 During the Ebola break, a dynamic art program was established for Liberian children. It focused on how therapeutic expressive arts could teach coping skills and build healthy relationships in a safe and supportive space for children to express themselves and experience healing; interventions that showed positive results early on.

The advantage of art programs like this is that once they are built by mental health professionals and child health specialists, they can be delivered in the communities using paraprofessionals who receive appropriate training. This allows the projects to be implemented at a wider area while more children benefit from.

Parenting

Looking after the wellbeing of children

Parents should provide a core pillar of support for children, with school and teachers, the rest of the family and friends providing robust supporting pillars. With home confinement, these supporting pillars break down and the parent becomes the only resource for a child to seek help from. When the wellbeing of the child is at risk, it is important for parents to monitor the children's behaviours and performance.

Open communication is necessary to identify any issues; physical or psychological. Having direct conversations about the pandemic can prove useful in mitigating their anxiety. A common notion is for parents to shield their children from bad news to protect them. It is true that most of the information about the pandemic that children are exposed to is not directed to them and it hence becomes overwhelming. However, children will still ask important questions and ask for satisfactory answers. Shielding the world from them is not the right answer.

Parents should practice active listening and responding appropriately to any questions the child might have as well as adapting their responses to the child's reactions. Narrating a story or encouraging the child to draw what is on their mind might enable the start of a discussion. Attention also needs to be given to any difficulties sleeping and the presence of nightmares as it could be a sign that the child is not coping well. Although strict monitoring of behaviours is required, it is a very delicate issue and it should not put the child into an uncomfortable position. With daily home confinement, it is important to respect the children's privacy and identity.

Whilst it may seem overwhelming to families to provide all the information required to children there are already many reliable resources available online about how best to maintain the health and wellbeing of their children through this pandemic. UNICEF has provided online resources for parents to use with emphasis given on how to talk to a child about the pandemic and provide comfort. Similarly, the WHO have also provided a series of posters on parenting during the pandemic again with the purpose of promoting the wellbeing of children.

Looking after the wellbeing of parents

Parents and carers are often portrayed as superheroes. However, even these superheroes may experience anxiety and fear during a pandemic. The psychological health of parents and their children seem to be inextricably linked and PTSD is commoner in children whose parents are experiencing it too.33

As parents with poorer mental health might not be able to respond to the needs of their children effectively, then addressing this is important. Alleviating their stressors will help improve mental health. Priority should be given in ensuring that the basic needs of these families are met, including food provisions, financial support, and healthcare access. Once these are provided, there are higher chances that any psychological support can have a positive effect on parents. Such support can have multiple different dimensions and various tools can be utilized. Such tools should be easily accessible, put to practice quickly and aim to strengthen mental resiliency. For instance, behavioural practitioners are suggesting the use of acceptance and commitment therapy.42

The power of family activities

Anecdotally the consequence of a prolonged period of lockdown for some families in the UK has been a positive one. Home confinement can benefit interactions and help children to engage in family activities. This may help strengthen family bonds and meet the psychological needs of a developing mind. Collaborative games fight loneliness and strengthen family relations. Other activities that families could do together include learning new skills like cooking or taking up new hobbies like building puzzles. Researchers have also shown that during the brief school closure due to the A/H1N1 influenza pandemic in 2010, as time went by, parents became more prepared and started planning more activities. This gave more reasons to young people to stay at home and helped in encouraging social distancing; which proved harder at the start of the influenza pandemic.43

Conclusion

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic goes beyond the risk of a severe acute respiratory response. It has posed severe social and economic consequences worldwide. Children and young people have been exposed to very severe repercussions which if not addressed, could have even worse outcomes in the future. Therefore, governments, communities, non-governmental organizations and healthcare professionals need to work in collaboration to prevent causing irreversible damage to a generation.

References

- 1.Ludvigsson J.F. Systematic review of COVID-19 in children shows milder cases and a better prognosis than adults. Acta Paediatr Int J Paediatr. 2020:1088–1095. doi: 10.1111/apa.15270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.She J., Liu L., Liu W. COVID-19 epidemic: disease characteristics in children. J Med Virol. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cruz A., Zeichner S. COVID-19 in children: initial characterization of the pediatric disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;145 doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carroll W.D., Strenger V., Eber E., et al. European and United Kingdom COVID-19 pandemic experience: the same but different. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2020;35:50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2020.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klein J.D., Koletzko B., El M.H., Hadjipanayis A., Thacker N., Bhutta Z. vols. 1–5. 2020. (Promoting and supporting children ’ s health and healthcare during COVID-19 – international paediatric association position statement). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abrams E.M., Szefler S.J. Managing asthma during COVID-19: an example for other chronic conditions in children and adolescents. J Pediatr. 2020;2019 doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braunack-Mayer A.J., Street J.M., Rogers W.A., Givney R., Moss J.R., Hiller J.E. Including the public in pandemic planning: a deliberative approach. BMC Publ Health. 2010;10 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brooks S.K., Webster R.K., Smith L.E., et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395:912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prime minister appeals to Canadian children to follow social distancing rules | CBC News.

- 10.Esposito S., Principi N. To mask or not to mask children to overcome COVID-19. Eur J Pediatr. 2020;27:9–12. doi: 10.1007/s00431-020-03674-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coronavirus US: Disney creates fabric face masks for children | Daily Mail Online.

- 12.Ashton J., Batra A., Coelho T., Afzal N., Beattie R. Challenges in chronic paediatric disease during the COVID-19 pandemic: diagnosis and management of inflammatory bowel disease in children. Arch Dis Child. 2020:321244. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-319482. 0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fazzi E., Galli J. New clinical needs and strategies for care in children with neurodisability during COVID-19. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2020:19–20. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.14557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wise J. Covid-19 is no worse in immunocompromised children, says NICE. BMJ. 2020;369 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.COVID-19-’shielding’ guidance for children and young people.

- 16.Isba R, Edge R, Jenner R, Broughton E, Francis N, Butler J. Where have all the children gone? Decreases in paediatric emergency department attendances at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020. 2020;0(0):2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Viner R., Ward J., Cheung R., Wolfe I., Hargreaves D. Child health in 2030 in England: comparisons with other wealthy countries. R Coll Paediatr Child Heal. 2018;(October) [Google Scholar]

- 18.“Isolated at home with their tormentor”: Childline experiences increase in calls since closure of schools.

- 19.Vpd S., Group S.A. 2020. Guiding principles for immunization activities during the COVID-19 pandemic; pp. 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faqs T. 2020. Frequently asked questions ( FAQ ) immunization in the context of COVID-19 pandemic; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brazendale K., Beets M.W., Weaver R.G., et al. Understanding differences between summer vs. school obesogenic behaviors of children: the structured days hypothesis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activ. 2017;14:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12966-017-0555-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pietrobelli A., Pecoraro L., Ferruzzi A., et al. Effects of COVID-19 lockdown on lifestyle behaviors in children with obesity living in Verona, Italy: a longitudinal study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2020 doi: 10.1002/oby.22861. 0–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rundle A.G., Park Y., Herbstman J.B., Kinsey E.W., Wang Y.C. COVID-19–Related school closings and risk of weight gain among children. Obesity. 2020;28:1008–1009. doi: 10.1002/oby.22813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lockdown and loaded: coronavirus triggers video game boost - BBC News.

- 25.Woo Baidal J.A., Chang J., Hulse E., Turetsky R., Parkinson K., Rausch J.C. Zooming towards a telehealth solution for vulnerable children with obesity during COVID-19. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2020 doi: 10.1002/oby.22860. 0–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dunn C., Kenney E., Fleischhacker S., Bleich S. Feeding low-income children during the covid-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;40:1–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2005638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.School closures caused by Coronavirus (Covid-19).

- 28.COVID-19: IFRC, UNICEF and WHO issue guidance to protect children and support safe school operations.

- 29.Wang G., Zhang Y., Zhao J., Zhang J., Jiang F. Mitigate the effects of home confinement on children during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet. 2020;395:945–947. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30547-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang J., Wu W., Zhao X., Zhang W. Recommended psychological crisis intervention response to the 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia outbreak in China: a model of West China Hospital. Precis Clin Med. 2020;3:3–8. doi: 10.1093/pcmedi/pbaa006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Decosimo C.A., Hanson J., Quinn M., Badu P., Smith E.G. Playing to live: outcome evaluation of a community-based psychosocial expressive arts program for children during the Liberian Ebola epidemic. Glob Ment Heal. 2019;6 doi: 10.1017/gmh.2019.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ross N., Gilbert R., Torres S., et al. Adverse childhood experiences: assessing the impact on physical and psychosocial health in adulthood and the mitigating role of resilience. Child Abuse Negl. 2020;103:2106–2115. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sprang G., Silman M. Posttraumatic stress disorder in parents and youth after health-related disasters. Disaster Med Pub Health Prep. 2013;7:105–110. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2013.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu S., Yang L., Zhang C., et al. Online mental health services in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatr. 2020;7:e17–e18. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30077-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duan L., Zhu G. Psychological interventions for people affected by the COVID-19 epidemic. Lancet Psychiatr. 2020;7:300–302. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30073-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mazza C., Ricci E., Biondi S., et al. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Italian people during the COVID-19 pandemic: immediate psychological responses and associated factors. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2020;17:1–14. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17093165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang Y., Li W., Zhang Q., Zhang L., Cheung T., Xiang Y.T. Mental health services for older adults in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatr. 2020;7:e19. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30079-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liem A., Wang C., Wariyanti Y., Latkin C.A., Hall B.J. The neglected health of international migrant workers in the COVID-19 epidemic. Lancet Psychiatr. 2020;7 doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30076-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weaver M.S., Wiener L. Applying palliative care principles to communicate with children about COVID-19. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2020;60(1):e8–e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berry N., Lobban F., Belousov M., et al. Understanding why people use Twitter to discuss mental health problems. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19 doi: 10.2196/jmir.6173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jiao W.Y., Wang L.N., Liu J., et al. Behavioral and emotional disorders in children during the COVID-19 epidemic. J Pediatr. 2020;221:264–266.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coyne L., Gould E.R., Grimaldi M., Wilson K.G., Baffuto G. First things first: parent psychological flexibility and self-compassion during COVID-19 lisa. Behav Analyst Pract. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s40617-020-00435-w. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miller J.C., Danon L., O'Hagan J.J., Goldstein E., Lajous M., Lipsitch M. Student behavior during a school closure caused by pandemic influenza A/H1N1. PLoS One. 2010;5:1–8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]