Abstract

Diabetes is a systemic disease that has achieved epidemic proportions in modern society. Ulcers and infections are common complications in the feet of patients with advanced stages of the disease, and are the main cause of amputation of the lower limb. Peripheral neuropathy is the primary cause of loss of the protective sensation of the feet and frequently leads to plantar pressure ulcers and osteoarticular disruption, which in turn develops into Charcot neuropathy (CN). Common co-factors that add to the morbidity of the disease and the risk of amputation in this population are obesity, peripheral arterial disease, immune and metabolic disorders. Orthopedic surgeons must be aware that the early detection and prevention of these comorbidities, through diligent medical care and patient education, can avoid these amputations.

Keywords: diabetes, foot, ulcer, infection, amputation

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a serious systemic disease whose incidence is rising along with the increase in obesity rates of the world population. 1 A bleak prospect is estimated for the year 2040, when it is believed that there will be 642 million diabetics in the world, which is to say that nearly 10% of the entire population of the planet will be diabetic. 2

Foot involvement in diabetic patients is associated with a chronic process that creates favorable conditions for the onset of plantar foot ulcer (DFU). 3 Among these triggering factors, some stand out: 1) peripheral neuropathy (PN) that causes loss of protective foot sensitivity; 2) peripheral arterial disease (PAD); and 3) the biomechanical alterations caused by osteoarticular destruction and deformities resulting from Charcot neuroarthropathy (CN), responsible for altering the supportive plantar foot pressure. 3

The prevention and treatment of DFU constitutes one of the major concerns in the care of diabetic patients. 4 Even when all preventive measures are properly adopted, the annual incidence of DFU reaches up to 2.2%. 5 Infections occur in up to 58% of patients who have a new DFU and, as a result, ∼ 5% of these patients will undergo a major amputation within 1 year. 6 7 Diabetic patients who develop foot injuries are subject to the high incidence of premature death directly associated with the high risk of major amputation in at least one of the lower limbs throughout life. 8 Mortality rate up to 5 years after DFU emergence reaches 45% in patients exhibiting a predominantly neuropathic ulcer, and 55% among those with ulcer with predominant cause in the ischemic component. 9

According to the US health care system, it is estimated that ∼ 20 to 40% of the amount of resources available to treat diabetic patients is spent on treating the complications of foot injuries. 10 One perspective of the large cost impact, potentially involved in treating complicated DFU with infection in diabetic patients, is provided by studies that estimate costs ranging from US$ 3,000.00 (Tanzania) up to US$ 188,000.00 (United States). 11

The aim of the present review is to highlight the main aspects of the pathophysiology and treatment of diabetes complications affecting the feet, highlighting ulcers and secondary infections. We will emphasize the importance of clinical history and physical examination in the correct diagnosis of these lesions, with emphasis on staging according to the severity of the various clinical situations that are present in the routine care of these patients. We believe it is very important to provide information that enables the orthopedic doctor to make appropriate therapeutic choices to try to prevent and, if possible, to avoid extremity amputation in diabetic patients.

Pathophysiology

The etiology of foot injuries in the diabetic patient is multifactorial and includes complications of neuropathy, vasculopathy, immunodeficiency, and uncontrolled blood glucose. 12 Peripheral nerve neuropathy results in loss of sensitivity, motor capacity (especially the intrinsic musculature of the foot) and autonomic deficit. In addition, it is undoubtedly the main cause involved in the emergence of foot ulcers and almost invariably is present in cases of CN. 3 12 13 Motor neuropathy causes structural changes in the foot due in part to muscle imbalance and intrinsic muscle weakness. Deformities most often triggered by motor neuropathy are claw toes, hammer toes, plantar prominence of metatarsal heads and cavus foot. 3 13 14 These deformities alter the patterns of plantar pressure during gait and make the numb feet even more susceptible to pressure ulcers. 3 13

Approximately 50% of diabetic patients have some degree of PAD. 15 Due to the neuroischemic process, it contributes directly to the development of neuropathy and consequent complications in the feet. 13 16 In diabetic patients affected by CN, the presence of advanced PAD is less common than in patients with pressure ulcer alone. 17 Immunodeficiency involving both the phagocytic ability of leukocytes, and their ability to produce antibodies (T lymphocytes), is well recognized in diabetic patients, contributing directly to the low immune response in the fight against infections. 18 19 Both PAD and immunodeficiency do not directly contribute to ulcer formation, but act as risk factors increasing the chance of complication in diabetic patients with neuropathy. 12

Initial Evaluation

Clinical History and Physical Examination

A detailed medical history is crucial in the proper management of complications related to the feet of diabetic patients. It is extremely important to adequately collect accurate information regarding disease duration, insulin dependence, pre-existing comorbidities, previous surgeries, family history, personal history (smoking, alcoholism, illegal drugs, availability of support and family assistance), and medications currently in use. 5 13

The physical examination is essential to check the presence of any deficit in the protective sensation of the feet using the Semmes-Wienstein monofilament test 5.07. 20 The skin should be examined for signs of autonomic neuropathy, particularly regarding dryness and the presence of skin fissures. Evidence of motor neuropathy can be observed mainly when there is imbalance in the intrinsic muscles of the foot causing claw or hammer deformity of the toes and, consequently, providing the plantar prominence of the metatarsal heads. 14 It is important to investigate the presence of excessive tension in the posterior leg musculature formed by the soleus-gastrocnemius complex that may be shortened, causing restriction in the range of motion of the ankle or even residual equinus foot, responsible for the generation of areas of hyperpressure in the plantar region of the forefoot. On static inspection, it is vital to check for signs of calluses or ulcers located under areas where bony prominences are identified in the forefoot plantar region. With the patient standing upright, it is important to search for edema, to assess the proper alignment of the feet and ankles, in addition to identifying signs of instability in the ankle region or engaging the entire hindfoot. During gait it is possible to verify the exacerbation of possible instability in these joints. 5 13

Vascular Tests

Diabetic patients are at high risk of developing vascular disease that compromises macro and microcirculation. 5 13 In macrovascular disease, the progressive occlusion of both deep femoral artery and the trifurcated infra popliteal segment (anterior tibial artery, posterior and peroneal) occurs. 15 Thus, it is important during clinical evaluation to always palpate the popliteal, posterior tibial and dorsal pulses of the foot. When it is possible to palpate the pulses of both the posterior tibial and dorsal arteries of the foot, it is unlikely to be any real need for vascular intervention, since blood circulation in the foot is adequate. 14 In contrast, the absence of a palpable pulse in the foot has sensitivity of ∼ 70% in the diagnosis of peripheral vascular disease, and when it is found, it is advisable to request expert assessment of a vascular surgeon. 14 In microvascular disease, microcirculation impairment that mainly affects the following organs typically occurs: 1) retinal vessels may cause amaurosis; 2) glomerular vessels with consequent impairment of renal function, which may result in complete failure of this organ; and 3) vessels that nourish the peripheral nerves (vasa nervorum) causing progressive degeneration and sensory-motor-autonomic neuropathy. 14 21 During clinical examination, it is important to identify apparent signs of peripheral arterial disease through the perception of cold skin during palpation of the foot, besides observing the decrease or absence of hair, skin redness and shiny skin. 5 13

At first, noninvasive vascular evaluation should assess the presence or absence of blood flow, its velocity and waveform by doppler ultrasound. 13 Abnormal tests are indicative of the presence of macrovascular disease, and identify the need to request consultation with a vascular surgeon for a more detailed assessment. 13 To evaluate possible changes in microcirculation, it is very useful to use the oximetry device to measure transcutaneous oxygen pressure at the extremity. According to the degree of tissue oxygenation measured, it is possible to estimate the degree of microcirculation impairment and the local healing potential of the DFU. 13 Any obvious signs of ischemia require immediate consultation with a physician specialized in endovascular treatment and, often, it is necessary to perform angiography to evaluate potential intervention to unclog an artery that is eventually blocked. 13 Revascularization of the extremity may restore macrovascular circulation; however, changes in the microvascular circulation system will persist, and may often cause negative impact on wound healing in the skin or surgical wounds. 13

Foot Ulcers

Plantar foot ulcer in diabetic patients occurs in ∼ 15% of those who already have peripheral neuropathy with loss of protective sensitivity. 22 They often result from repetitive trauma or excessive pressure patterns acting on one extremity whose sensitivity is greatly diminished or absent. When the presence of an ulcer is detected, the patient should be questioned about the duration and progression of the lesion size. Persistence of an ulcer in the same site for .> 30 days is associated with a significant increase in the risk of infection that may eventually progress to osteomyelitis. 23 In addition, it is very important to identify the exact location of the ulcer, to accurately measure its diameter and depth, besides assessing the presence or absence of protective sensitivity and active bleeding at the wound margins. Patients whose ulcer size exceeds 2 cm 2 are more likely to develop osteomyelitis. 23 24

Classification of Ulcers

The University of Texas Wound Classification System is highly efficient as a predictor of ulcer healing and was elected as the standard classification system recommended by experts. 25 26 It focuses on the evaluation of the depth of the ulcer, the presence or absence of abscess, osteomyelitis, gangrene and pyoarthritis, in addition to documenting the presence of ischemia in the extremity. 3 ( Table 1 )

Table 1. University of Texas classification for foot injuries.

| Grade 0 | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage A | Pre-or postulcerative lesion completely epithelialized | Superficial wound not involving tendon, capsule, or bone | Wound penetrating to tendon or capsule | Wound penetrating bone or joint |

| Stage B | With infection | With infection | With infection | With infection |

| Stage C | With ischemia | With ischemia | With ischemia | With ischemia |

| Stage D | With infection and ischemia | With infection and ischemia | With infection and ischemia | With infection and ischemia |

Treatment of Ulcers

Initial DFU treatment includes local debridement, removal of weight bearing load of the foot, and frequent dressing. Local debridement does not require any anesthesia due to lack of sensitivity caused by peripheral neuropathy, and is capable of turning a chronic wound into an acute wound as it removes necrotic tissue and reduces the number of bacteria that form the biofilm around the ulcer, creating a favorable environment for healthy granulation tissue formation. 13 Removal of weight bearing, preventing the load support on the foot sole, combined with creating a bleeding environment at the base of the ulcer, is essential for healing of neuropathic ulcers. Frequent dressing change, keeping the wound clean, is apparently enough to promote healing if local pressure has been drastically reduced. There is insufficient evidence to support any recommendation regarding the use of topical medications, or even commercially developed dressings, which are often costly and claim to have the potential benefit of accelerating DFU healing. 13

Changes in patient conditions are crucial to facilitate DFU healing and include: adequate glycemic control, optimal nutritional status, total cessation of smoking, and improved circulation in the extremity. 13 The favorable prognosis for DFU healing can be measured by checking for at least 50% reduction in ulcer diameter after 4 weeks employing appropriate treatment through local wound care and elimination of the load on the affected extremity; otherwise, the potential for spontaneous wound healing is low. 27 28

Weight Bearing

One of the most important components in the treatment of DFU is the removal of the load through the following alternatives: 1) use of therapeutic shoes with high wedge soles; 2) removable boots; 3) walkers; 4) custom-made orthoses; 5) total contact casting (TCC).

Total contact casting or custom-made orthoses specially designed to reduce plantar pressure on the DFU remain the standard procedure for treating DFU. 27 28 29 The superiority of TCC over removable orthoses in the treatment of DFU resides in the adherence of the patient to the treatment, as studies indicate that the average wearing time of removable orthoses is restricted to only 28% of all daily activities. 30

Surgery for percutaneous Achilles tendon lengthening may be indicated in combination with the treatment of the forefoot DFUs with TCC when there is restriction in ankle dorsiflexion (it is not possible to bend this joint beyond 90°). The increased dorsiflexion ability of the ankle provided by stretching the Achilles tendon often assists in decreasing forefoot plantar pressure, accelerating the healing of plantar ulcers, and decreasing the incidence of recurrence of these lesions in the medium term. 31

Advanced Modes for Ulcer Healing

More recently, hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) and negative pressure therapy (NPT) have been advocated as advanced modalities to accelerate wound healing. There is considerable debate about the real effectiveness of these treatment proposals. Prospective randomized, controlled, double-blind studies are inconclusive regarding the effect of HBOT or NPT on the reduction in amputation rates compared to the treatment with only local wound care. 32 33 34

Recurrence of Ulcers

Patient education plays a key role in preventing DFU recurrence. As patients can understand the mechanism that causes the injury, they can participate more actively and adhere to strategies to prevent the emergence of new ulcers. Despite the greater participation of patients in prevention, the relapse rate is high and reaches levels above 40%. 35 36 37 This high prevalence is due to the fact that PN and PAD persist as the true factors directly involved in the pathophysiology of these lesions. 13 Due to its course marked by frequent relapses, recurrent ulceration is highly prone to develop severe complications involving deep infection, abscess formation, and osteomyelitis. 38 39 As a result, the estimated risk of extremity amputation at some point in the course of this condition varies from 71 to 85% of the cases. 40 41

Foot Infections

Approximately 50% of DFUs suffer from contiguous secondary infection, causing a profound negative impact on the quality of life of the patient. 6 42 The main risk factors associated with DFU infection are: 1) deep ulcerated lesions; 2) ulcers present for > 30 days; 3) previous history of recurrent ulcers; 4) injuries of traumatic etiology; 5) concomitant presence of PAD. 23

On clinical examination, it is important to note that the diabetic patient may not manifest typical signs and symptoms of a serious infection (general malaise, numbness, nausea, anorexia and fever) due to their poor immune-leukocyte response. 43 The earliest sign of a serious infection is a hyperglycemia that does not recede even when the prescribed insulin dosage is significantly increased. 5 13 It is essential, at this moment, to perform detailed inspection of the ulcer, verifying the following aspects: 1) its extension (diameter > 2 centimeters is a warning sign); 2) its depth (introducing an instrument through the wound and noticing that it touches the underlying bone is a sign of seriousness, and is a predictive factor for osteomyelitis with an incidence rate between 53 and 89%); 3) its odor (when fetid, it is suggestive of deep abscess); 4) its margins; 5) the presence of drainage (dense and turbid yellowish discharge denotes presence of pus). 23 24 36 44 45 46 47 48 It is always recommended to perform the elevation of the extremity for ∼ 5 to 10 minutes to determine if the possibly present erythema is due to an infectious process (erythema does not recede) or CN (erythema recedes). 3 49 50

Simple laboratory tests, such as: 1) the presence of increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR); 2) hyperglycemia; and 3) leukocytosis, may help in the diagnosis of an active infection. Plain radiographs with conventional foot and ankle views may show images with signs of rupture of the cortical bone underlying the corresponding DFU region. These changes are highly suggestive of the presence of osteomyelitis; however, they appear later, only becoming visible after 10 to 20 days from the beginning of the bone infection. 51 52

Once the infection is diagnosed, the patient must be admitted to the hospital for immediate treatment. Laboratory tests necessary to monitor the evolution of the clinical condition of the patient during treatment should be ordered and repeated regularly. Stand out, among them: 1) complete blood count; 2) ESR; 3) C-reactive protein; 4) albumin dosage; 5) glycemic dosage; 6) renal and hepatic function tests (serum urea, creatinine, glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase [GOT], glutamic pyruvic transaminase [GPT]). 13 It is advisable to elect a clinician to monitor and keep track of the metabolic functions of the patient throughout the hospitalization period to treat the infection.

To assess the severity of the situation, it is important to measure the true extent of the initial involvement of both soft tissues and bones and joints. 3 13 49 Plain radiographs can be very useful and they need to be studied carefully in the search for the following signs: 1) cortical bone erosion; 2) periosteal reaction; 3) images suggestive of the presence of gas in the soft tissues (often produced by anaerobic germs); 4) radiopaque images suggestive of possible foreign bodies from previous injury not recognized by the patient. 5 21 51 52 Bone scintigraphy and nuclear magnetic resonance may be useful and help in the diagnosis of osteomyelitis. 23 51 52 53 54 55

Once the presence of infection is identified, it is necessary to collect deep tissue samples, preferably bone tissue, from the ulcer, and send it for culture of both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. 53 It is important to identify the infecting germ to properly select the most appropriate antibiotic. 26 33

Infection Treatment

Treatment of foot infections is dictated by the severity of the condition. Superficial infections should be treated with surgical debridement to remove all necrotic tissue, moist dressing, and measures to prevent weight-bearing on the foot. In addition, it is necessary to add to the mentioned cares the prescription of oral empirical antibiotics, as well as outpatient follow-up with frequent visits to closely monitor the evolution of the clinical condition. 3 13 49 The duration of antibiotic treatment is controversial, but it should be maintained until the resolution of infection. 25

Some moderate infections and all deep and severe infections require immediate hospitalization to start the treatment as soon as possible to reduce the risk of amputation. 46 56 In severe cases, it is mandatory to perform early surgical intervention aimed at draining deep abscesses and removing, through careful debridement, both devitalized soft tissues and all infected and necrotic bone. Emphasis should be placed on the recommendation to leave the surgical wound fully open to allow for continuous drainage and to prevent further abscess collection. 46 56 ( Figure 1 ) Multiple sequentially scheduled interventions are often required in a short time period (∼ 48 hours) to make sure that all necrotic tissue has been completely removed and only viable uninfected tissue remains in the debridement bed, the well-known granulation tissue ( Figure 2 ).

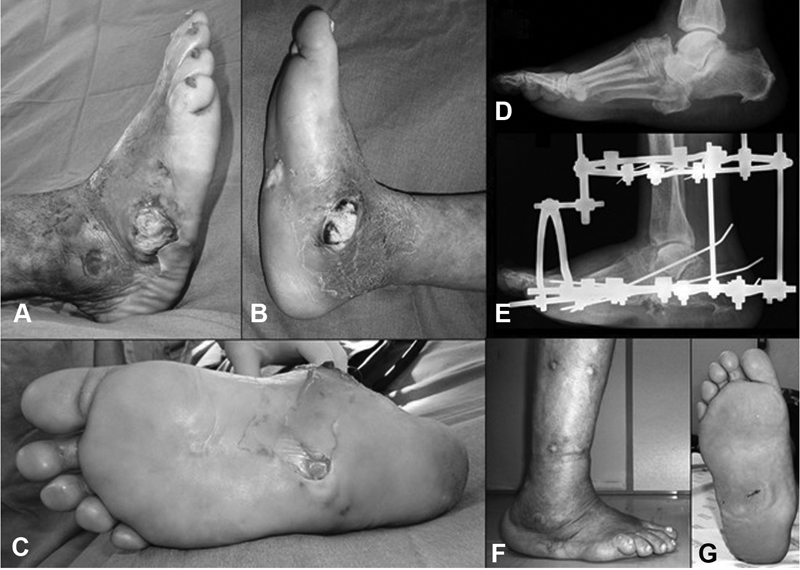

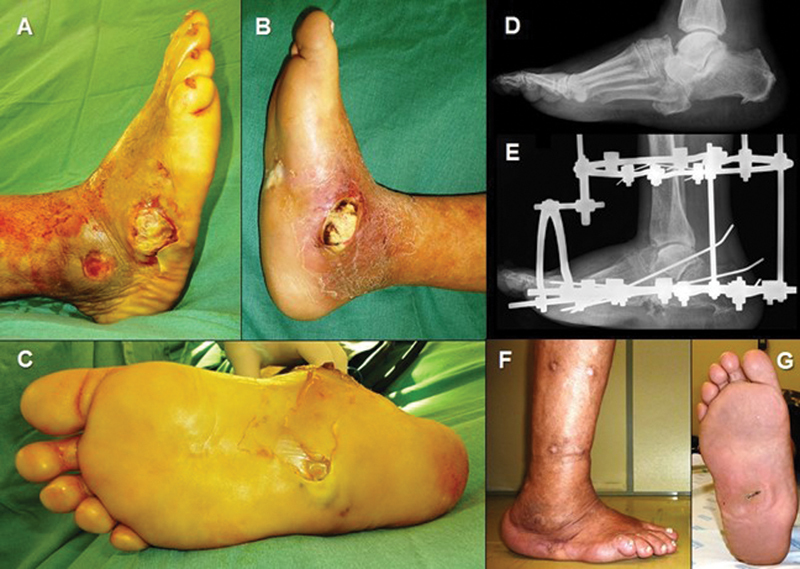

Fig. 1.

Lateral ( A ), medial ( B ) and plantar ( C ) images of the right foot, showing the presence of multiple ulcers infected with associated tissue necrosis. In the preoperative radiographic image, performed in the lateral view of the foot, there is a talonavicular dislocation and a plantar protrusion of the cuboid bone in the midfoot ( D ). After surgical debridement and removal of the dislocated cuboid bone, the radiographic image in the lateral view of the foot shows the stabilization of the extremity with the circular external fixator ( E ). Six months after treatment, it was possible to avoid amputation of the extremity and the foot is aligned and free of infection and ulcers ( F and G ).

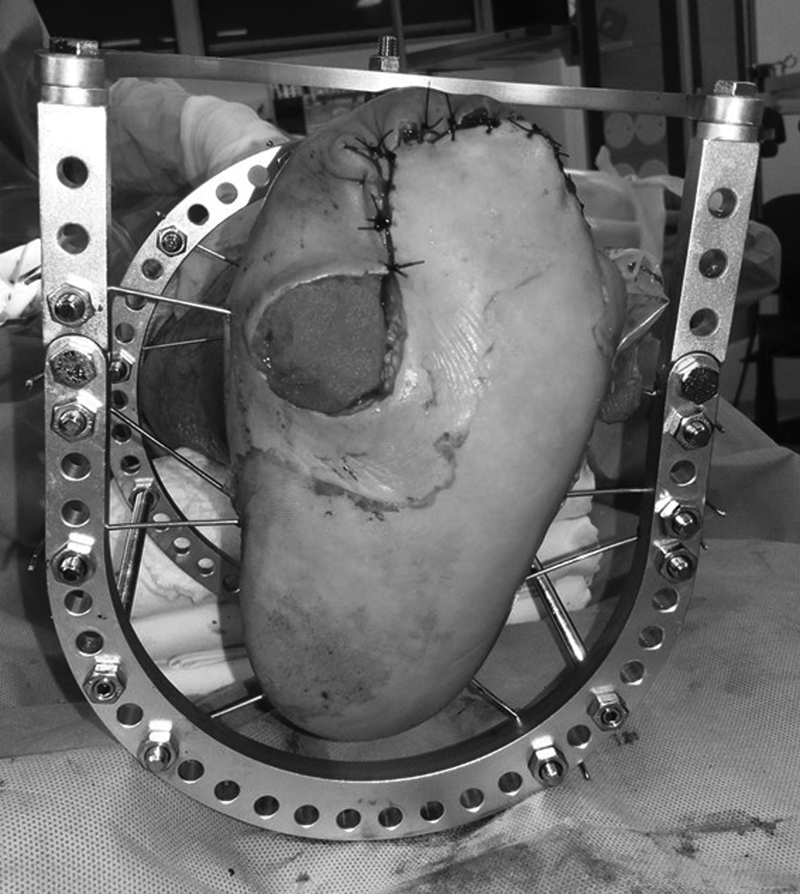

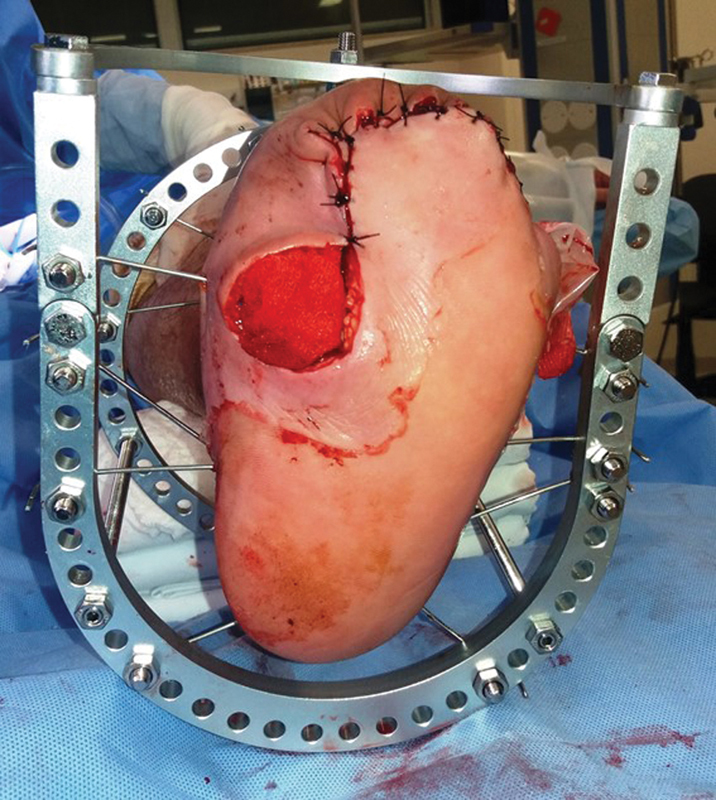

Fig. 2.

Plantar view of the left foot after surgery for debridement of infected plantar ulcer followed by abscess drainage, removal of devitalized tissue and transmetatarsal partial amputation. The area corresponding to the ulcer was left open and covered with an occlusive dressing with saline moistened gauze. The extremity was stabilized with a circular external fixator and the patient was hospitalized for systemic intravenous antibiotic therapy of broad spectrum.

Intravenous antibiotic therapy is always required to treat severe infections and its duration depends on the extent of the infection. 25 Bone tissue cultures collected during debridement surgery are important to direct specific antibiotic treatment. 33 55 It may be necessary to consult an infectious disease specialist to assist in the selection and monitoring of antibiotics, because the combination of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria in deep infections is often the rule and, frequently, antibiotic combination of drugs with nephrotoxic and hepatotoxic potential used for prolonged periods (usually 6 to 12 weeks) is required. 55

Amputations

Even with prompt appropriate treatment, foot infections in diabetic patients can be difficult to control, and the possibility of amputation is always present and should be discussed with the patient beforehand. 5 13 49 Studies show that the risk of amputation exceeds 20% of the cases of moderate or severe infection. 44 57 58 Diabetic patients who develop foot infection are 56 times more likely to be hospitalized, and 154 times more likely to need amputation than those patients who present no infection. 23 The most commonly amputation levels performed involve the forefoot, midfoot, Syme, transtibial (below the knee), and transfemoral (above the knee). 5 13 49 The surgeon should consider the specific factors and requirements of each patient before deciding which is the most appropriate level for amputation, aiming at family and social reintegration, besides allowing the possibility of functional recovery compatible with the conditions and functional capacities of the patient. 5 13 49 Despite the goal of the surgeon to preserve the longest possible extremity in an effort to reduce the energy expenditure required for ambulation after an amputation, it is necessary to evaluate the patient's healing ability before performing the surgery. 13 It is noteworthy that morbidity and mortality after major amputations (transtibial or transfemoral) are high, reaching 29% in the first 2 years after surgery. 13 Diabetic patients with chronic renal failure requiring dialysis are particularly vulnerable to major amputations, reaching a 52% mortality rate within 2 years of surgery. 13 In addition, ∼ 10% of amputated patients require contralateral transtibial amputation. 13 Despite amputation-related problems, it provides a better chance of recovery compared to multiple rescue attempts in a sick patient. 5 49 In some selected patients, amputation of a severely compromised extremity can significantly improve quality of life, even improving the physical capacity of the patients and allowing to maintain independent ambulation using lower limb prosthesis. 59

Prevention

The different problems that can affect the feet in diabetic patients often present initially as hidden signs, making immediate diagnosis difficult. It is necessary and essential for the physician to have a high degree of suspicion and constant, and highly accurate surveillance, to detect potentially serious situations at an early stage. We can say without a doubt that, in diabetic patients, early and accurate diagnosis of complications is essential for successful treatment.

Prevention should be the primary focus of attention to try to avoid the sequence of events that can trigger extremity amputation. 5 13 49 Avoiding DFU development, and treating pre-existing ones to try to prevent them from becoming infected, is an arduous task that requires the utmost attention and the participation of the patient, family members, and health professionals headed by the doctor. The following actions play a crucial role in preventing DFU: 1) conducting patient education programs; 2) encouraging the use of protective footwear and molded insoles made of soft material (indicated to accommodate preexisting deformities and also reduce friction on the sole in the foot support phase during gait); 3) medical and other health professionals available for periodic clinical evaluation of patients at risk.

Concluding Remarks

Diabetes mellitus is a systemic disease with serious manifestations in the lower limbs, affecting mainly the feet and causing high morbidity and mortality for patients. Diabetic foot is a well-known term that truly corresponds to a syndrome that presents with a broad spectrum of signs and symptoms, all due to chronic and late complications of DM. The main manifestations of diabetic foot are: neuroarthropathy, ulceration, and infection. These problems often overlap with previously installed deformities such as claw toes, equinus toe contracture, and skin disorders caused by dry skin. The etiology of these complications is multifactorial and includes neuropathy, vasculopathy, immunodeficiency and inadequate glycemic control.

Proper management of the problems that affect the foot in diabetic patients begins with an appropriate clinical evaluation to allow early start of treatment. The main emphasis should be focused on prevention strategies, especially: 1) patient education; 2) frequent monitoring with periodic examinations; 3) direct and understandable communication between the patient and the multidisciplinary team involved in the treatment and composed of surgeons, clinicians, endocrinologists, infectologists, in addition to orthopedic surgeons specialized in the treatment of foot and ankle disorders.

Conflitos de Interesses O autor declara não haver conflitos de interesses.

Trabalho desenvolvido no Grupo de Cirurgia do Pé e Tornozelo, Departamento de Ortopedia e Traumatologia da Santa Casa de Misericórdia de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brasil.

Study developed at Foot and Ankle Surgery Group, Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology of Santa Casa de Misericórdia de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

Referências

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.National Diabetics Statistics Report 2017 Department of Health and Human Services, Center for Disease Prevention and Control; 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu F B. Globalization of diabetes: the role of diet, lifestyle, and genes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(06):1249–1257. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brodsky J W. St Louis, MO: Mosby; 1993. The diabetic foot; pp. 278–283. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amaral A H, Junior, Amaral L AH, Bastos M G, Nascimento L C, Alves M J, Andrade M AP.Prevenção das lesões de membros inferiores e redução da morbidade em pacientes diabéticos Rev Bras Ortop 20144905482–487.26229849 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abbott C A, Carrington A L, Ashe H. The North-West Diabetes Foot Care Study: incidence of, and risk factors for, new diabetic foot ulceration in a community-based patient cohort. Diabet Med. 2002;19(05):377–384. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2002.00698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prompers L, Huijberts M, Apelqvist J. High prevalence of ischaemia, infection and serious comorbidity in patients with diabetic foot disease in Europe. Baseline results from the Eurodiale study. Diabetologia. 2007;50(01):18–25. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0491-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prompers L, Schaper N, Apelqvist J. Prediction of outcome in individuals with diabetic foot ulcers: focus on the differences between individuals with and without peripheral arterial disease. The EURODIALE Study. Diabetologia. 2008;51(05):747–755. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-0940-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wukich D K, Raspovic K M, Suder N C. Patients with diabetic foot disease fear major lower-extremity amputation more than death. Foot Ankle Spec. 2018;11(01):17–21. doi: 10.1177/1938640017694722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moulik P K, Mtonga R, Gill G V. Amputation and mortality in new-onset diabetic foot ulcers stratified by etiology. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(02):491–494. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boulton A J, Vileikyte L, Ragnarson-Tennvall G, Apelqvist J.The global burden of diabetic foot disease Lancet 2005366(9498):1719–1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cavanagh P, Attinger C, Abbas Z, Bal A, Rojas N, Xu Z R. Cost of treating diabetic foot ulcers in five different countries. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2012;28 01:107–111. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibbons G W, Habershaw G M. Diabetic foot infections. Anatomy and surgery. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1995;9(01):131–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Del Core M A, Ahn J, Lewis R B.The evaluation and treatment of diabetic foot ulcers and diabetic foot infections Foot Ankle Int. 20183(1S):13S–23S. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robinson A H, Pasapula C, Brodsky J W. Surgical aspects of the diabetic foot. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91(01):1–7. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B1.21196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wukich D K, Shen W, Raspovic K M, Suder N C, Baril D T, Avgerinos E. Noninvasive arterial testing in patients with diabetes: a guide for foot and ankle surgeons. Foot Ankle Int. 2015;36(12):1391–1399. doi: 10.1177/1071100715593888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wukich D K, Sadoskas D, Vaudreuil N J, Fourman M. Comparision of diabetic Charcot patients with and without foot wounds. Foot Ankle Int. 2017;38(02):140–148. doi: 10.1177/1071100716673985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wukich D K, Raspovic K M, Suder N C. Prevalence of peripheral arterial disease in patients with diabetes Charcot neuroarthropathy. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2016;55(04):727–731. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2016.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richard C, Wadowski M, Goruk S, Cameron L, Sharma A M, Field C J. Individuals with obesity and type 2 diabetes have additional immune dysfunction compared with obese individuals who are metabolically healthy. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2017;5(01):e000379. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2016-000379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grayson M L, Gibbons G W, Balogh K, Levin E, Karchmer A W. Probing to bone in infected pedal ulcers. A clinical sign of underlying osteomyelitis in diabetic patients. JAMA. 1995;273(09):721–723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suder N C, Wukich D K. Prevalence of diabetic neuropathy in patients undergoing foot and ankle surgery. Foot Ankle Spec. 2012;5(02):97–101. doi: 10.1177/1938640011434502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peterson N, Widnall J, Evans P, Jackson G, Platt S. Diagnostic imaging of diabetic foot disorders. Foot Ankle Int. 2017;38(01):86–95. doi: 10.1177/1071100716672660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reiber G E.The epidemiology of diabetic foot problems Diabet Med 199613(uppl 1, Suppl 1)S6–S11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lavery L A, Armstrong D G, Wunderlich R P, Mohler M J, Wendel C S, Lipsky B A. Risk factors for foot infections in individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(06):1288–1293. doi: 10.2337/dc05-2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richard J L, Lavigne J P, Sotto A. Diabetes and foot infection: more than double trouble. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2012;28 01:46–53. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lavery L A, Armstrong D G, Harkless L B. Classification of diabetic foot wounds. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1996;35(06):528–531. doi: 10.1016/s1067-2516(96)80125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oyibo S O, Jude E B, Tarawneh I, Nguyen H C, Harkless L B, Boulton A J. A comparison of two diabetic foot ulcer classification systems: the Wagner and the University of Texas wound classification systems. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(01):84–88. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rossi W R, Rossi F R, Fonseca Filho F F. Pé diabético: o tratamento das úlceras plantares com gesso de contato total e análise dos fatores que interferem no tempo de cicatrização. Rev Bras Ortop. 2005;40(03):89–97. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheehan P, Jones P, Caselli A, Giurini J M, Veves A. Percent change in wound area of diabetic foot ulcers over a 4-week period is a robust predictor of complete healing in a 12-week prospective trial. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(06):1879–1882. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.6.1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lavery L A, Higgins K R, La Fontaine J, Zamorano R G, Constantinides G P, Kim P J. Randomised clinical trial to compare total contact casts, healing sandals and a shear-reducing removable boot to heal diabetic foot ulcers. Int Wound J. 2015;12(06):710–715. doi: 10.1111/iwj.12213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Armstrong D G, Lavery L A, Kimbriel H R, Nixon B P, Boulton A J. Activity patterns of patients with diabetic foot ulceration: patients with active ulceration may not adhere to a standard pressure off-loading regimen. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(09):2595–2597. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.9.2595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mueller M J, Diamond J E, Sinacore D R. Total contact casting in treatment of diabetic plantar ulcers. Controlled clinical trial. Diabetes Care. 1989;12(06):384–388. doi: 10.2337/diacare.12.6.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blume P A, Walters J, Payne W, Ayala J, Lantis J. Comparison of negative pressure wound therapy using vacuum-assisted closure with advanced moist wound therapy in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(04):631–636. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fedorko L, Bowen J M, Jones W. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy does not reduce indication for amputation in patients with diabetes with nonhealing ulcers of the lower limb: a prospective, double blind, randomized controlled clinical trial. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(03):392–399. doi: 10.2337/dc15-2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Löndahl M, Katzman P, Nilsson A, Hammarlund C. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy facilitates healing of chronic foot ulcers in patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(05):998–1003. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bus S A, van Deursen R W, Armstrong D G, Lewis J E, Caravaggi C F, Cavanagh P R. Footwear and offloading interventions to prevent and heal foot ulcers and reduce plantar pressure in patients with diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2016;32 01:99–118. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bus S A, van Netten J J, Lavery L A. IWGDF guidance on the prevention of foot ulcers in at-risk patients with diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2016;32 01:16–24. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pound N, Chipchase S, Treece K, Game F, Jeffcoate W. Ulcer-free survival following management of foot ulcers in diabetes. Diabet Med. 2005;22(10):1306–1309. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reiber G E, Lipsky B A, Gibbons G W.The burden of diabetic foot ulcers Am J Surg 1998176(2A, Suppl)5S–10S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taylor S M, Johnson B L, Samies N L.Contemporary management of diabetic neuropathic foot ulceration: a study of 917 consecutively treated limbs J Am Coll Surg 201121204532–545., discussion 546–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Laborde J M. Neuropathic plantar forefoot ulcers treated with tendon lengthenings. Foot Ankle Int. 2008;29(04):378–384. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2008.0378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reiber G E, Boyko E J, Smith D J. Bethesda, Md: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 1995. Lower extremity foot ulcers and amputation in diabetes; pp. 409–428. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raspovic K M, Wukich D K. Self-reported quality of life and diabetic foot infections. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2014;53(06):716–719. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2014.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bagdade J D, Root R K, Bulger R J. Impaired leukocyte function in patients with poorly controlled diabetes. Diabetes. 1974;23(01):9–15. doi: 10.2337/diab.23.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wukich D K, Hobizal K B, Raspovic K M, Rosario B L. SIRS is valid in discriminating between severe and moderate diabetic foot infections. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(11):3706–3711. doi: 10.2337/dc13-1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lam K, van Asten S A, Nguyen T, La Fontaine J, Lavery L A. Diagnostic accuracy of probe to bone to detect osteomyelitis in diabetic foot: a systematic review. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(07):944–948. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aragón-Sánchez F J, Cabrera-Galván J J, Quintana-Marrero Y. Outcomes of surgical treatment of diabetic foot osteomyelitis: a series of 185 patients with histopathological confirmation of bone involvement. Diabetologia. 2008;51(11):1962–1970. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1131-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lavery L A, Armstrong D G, Peters E J, Lipsky B A. Probe-to-bone test for diagnosing diabetic foot osteomyelitis: reliable or relic? Diabetes Care. 2007;30(02):270–274. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morales Lozano R, González Fernández M L, Martinez Hernández D, Beneit Montesinos J V, Guisado Jiménez S, Gonzalez Jurado M A. Validating the probe-to-bone test and other tests for diagnosing chronic osteomyelitis in the diabetic foot. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(10):2140–2145. doi: 10.2337/dc09-2309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brodsky J W. Outpatient diagnosis and care of the diabetic foot. Instr Course Lect. 1993;42:121–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cierny G, III, Mader J T, Penninck J J. A clinical staging system for adult osteomyelitis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;(414):7–24. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000088564.81746.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Malhotra R, Chan C S, Nather A.Osteomyelitis in the diabetic footDiabet Foot Ankle201405 10.3402/dfa.v5.24445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Sanverdi S E, Ergen B F, Oznur A.Current challenges in imaging of the diabetic footDiabet Foot Ankle20123 10.3402/dfa.v3i0.18754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Lepäntalo M, Apelqvist J, Setacci C. Chapter V: Diabetic foot. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011;42 02:S60–S74. doi: 10.1016/S1078-5884(11)60012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pineda C, Espinosa R, Pena A. Radiographic imaging in osteomyelitis: the role of plain radiography, computed tomography, ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging, and scintigraphy. Semin Plast Surg. 2009;23(02):80–89. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1214160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tone A, Nguyen S, Devemy F. Six-week versus twelve-week antibiotic therapy for nonsurgically treated diabetic foot osteomyelitis: a multicenter open-label controlled randomized study. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(02):302–307. doi: 10.2337/dc14-1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schneekloth B J, Lowery N J, Wukich D K. Charcot neuroarthropathy in patients with diabetes: an update systematic review of surgical management. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2016;55(03):586–590. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van Battum P, Schaper N, Prompers L. Differences in minor amputation rate in diabetic foot disease throughout Europe are in part explained by differences in disease severity at presentation. Diabet Med. 2011;28(02):199–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2010.03192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wukich D K, Hobizal K B, Brooks M M. Severity of diabetic foot infection and rate of limb salvage. Foot Ankle Int. 2013;34(03):351–358. doi: 10.1177/1071100712467980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wukich D K, Ahn J, Raspovic K M, La Fontaine J, Lavery L A. Improved quality of life after transtibial amputations in patients with diabetes-related foot complications. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2017;16(02):114–121. doi: 10.1177/1534734617704083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]