Abstract

Background:

Heart failure patients have significant symptom burden, care needs, and often a progressive course to end-stage disease. Palliative care referrals may be helpful but it is currently unclear who and when patients should be referred. We conducted a systematic review of the literature to examine referral criteria for palliative care among heart failure patients.

Methods:

We searched Ovid, MEDLINE, Ovid Embase, and PubMed databases for articles in the English language from the inception of databases to January 17, 2019 related to palliative care referral in heart failure patients. Two investigators independently reviewed each citation for inclusion and then extracted the referral criteria. Referral criteria were then categorized thematically.

Results:

Of the 1199 citations in our initial search, 102 articles were included in the final sample. We identified 18 categories of referral criteria, including 7 needs-based criteria and 10 disease-based criteria. The most commonly discussed criterion was “Physical or emotional symptoms” (n=51 [50%]), followed by “Cardiac stage” (n=46 [45%]), “Hospital utilization” (n=38 [37%]), “Prognosis” (n=37 [36%]) and “Advanced cardiac therapies” (n=36 [35%]). Under cardiac stage, 31 (30%) articles suggested NYHA functional class ≥III and 12 (12%) recommended NYHA class ≥IV as cutoffs for referral. Prognosis of ≤1 year was mentioned in 21 (21%) articles as a potential trigger; few other criteria had specific cutoffs.

Conclusions:

This systematic review highlighted the lack of consensus regarding referral criteria for the involvement of palliative care in heart failure patients. Further research is needed to identify appropriate and timely triggers for palliative care referral.

Keywords: heart failure, palliative care, referral and consultation, selection criteria, symptom assessment, systematic review

Introduction

Heart failure is a global pandemic that affects 26 million people1. Despite significant scientific advancements, in the majority of cases, it still remains a progressive incurable disease2. Patients with advanced heart failure often suffer from a multitude of physical and psychological sequelae3 and encounter many complex decision-making needs necessitating sensitive communication throughout the unpredictable disease trajectory.

Palliative care is a philosophy of care that utilizes a holistic, multidisciplinary approach that seeks to improve quality of life through relief of suffering and stress by addressing the various (physical, psychosocial, spiritual) needs of patients and families when faced with life-threatening illness4. The World Health Organization has recommended “integrating palliative care into all relevant global disease control and health system plans” and “developing guidelines and tools on integrated palliative care across disease groups and levels of care, addressing ethical issues related to the provision of comprehensive palliative care”5. Over the past few years, there has been an increased recognition of the role that palliative care can play in improving health outcomes for patients with advanced heart failure6–8. Various organizations in the U.S. and worldwide, such as the American College of Cardiology, International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation, and European Society of Cardiology, have made recommendations supporting early integration of palliative care into heart failure management7, 9, 10. Currently, palliative care involvement for patients with heart failure remains suboptimal, with referrals often being made too late in the disease course11–13. This is partly attributed to the lack of standardized referral criteria, along with other factors such as heart failure’s unpredictable disease trajectory, variable healthcare providers’ attitudes and beliefs about palliative care, and variable access to specialty palliative care2, 11.

Unlike the field of oncology where there has been a fair amount of literature supporting the idea that timely and appropriate palliative care referrals can be beneficial, such evidence appears to be lacking when it comes to heart failure. A clearer understanding of the current criteria used to initiate a palliative care referral would be helpful towards a) improving the rate of referral of appropriate patients for palliative care interventions in a timely manner, b) allowing programs to establish clear and effective measures for quality improvement purposes, c) providing researchers a uniformity of standard for which to design future trials involving heart failure and palliative care, and d) paving the way for policymakers to help set up guidelines for optimal clinical care including facilitating benchmarking between services providing cardiac care, as well as shaping the evolution of palliative care programs. We conducted a systematic review of the literature to examine referral criteria for palliative care among patients with heart failure. This would represent a first step towards developing a standardized set of appropriate and timely referral criteria.

Methods

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Literature Search

The institutional review board at MD Anderson Cancer Center provided approval to proceed without the need for full committee review. Our clinical librarian searched Ovid, MEDLINE, Ovid Embase, and PubMed databases for publications in the English language from the inception of databases to January 17, 2019. The following concepts were searched using subject headings and keywords as needed, “palliative care”, “palliative medicine”, “terminal care”, “hospice care”, “end-of-life care”, “advance care planning”, “referral and consultation”, “referral”, “consultation”, “patient transfer”, “delivery of health care, integrated”, “heart failure”, and “myocardial failure” etc. The search terms were combined by “or” if they represented similar concepts, and by “and” if they represented different concepts. The majority of case reports and conference abstracts were excluded. The complete MEDLINE Search strategy is detailed in Appendix I (Supplemental Material).

After the initial search, two investigators (Y.C., H.K.) independently reviewed the title and abstract of each citation for inclusion. We included all original studies, reviews, systematic reviews, guidelines, editorials, commentaries, and letters, and excluded duplicates, case reports, and conference abstracts. If either of the two investigators coded that article as related to referral criteria for palliative care then that publication was included for further review. After the preliminary round, we then retrieved the full text of each article of interest and again two investigators (Y.C., H.K.) independently reviewed each of the articles and coded each publication as to whether it contained referral criteria for palliative care for heart failure patients. Among the 211 articles, 80 (%), 22 (%) and 109 (%) had 2, 1 and 0 reviewers endorsement for inclusion, respectively. The rate of agreement was 189/211=90% (Kappa 0.79, P<0.001) A senior investigator (D.H.) then reviewed the discrepancies and provided arbitration for the 22 publications in question which were ultimately all included.

Data Collection

All articles were reviewed by a palliative care physician (Y.C.) who extracted the referral criteria. These criteria were then categorized based on their themes. Our categorization of the referral criteria can also be further classified under two major domains (Table 1): needs-based criteria (i.e., patient/caregiver supportive care concerns) and disease-based criteria (i.e., diagnosis, prognosis, progression, or utilization of healthcare resources), which are modeled after the oncology palliative care literature14. A second investigator (H.K.) provided a secondary review (of all articles) for consistency. There was disagreement on the categorization for only 2 of 102 articles. With the aid of a third investigator (D.H.), we arrived at an overall consensus. This systematic review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guideline for reporting15 where applicable.

Table 1.

Palliative care referral criteria for heart failure

| Needs-based criteria | N(%) | Domain |

|---|---|---|

|

Physical or emotional symptoms2, 4, 6, 11, 12, 16–59 Mood disturbance, dyspnea, refractory pain, weight loss, ESAS score >7, fatigue, refractory angina, frailty, insomnia |

51 (50) | Needs |

|

Functional decline4, 12, 18, 21, 22, 26–28, 33–36, 38–40, 45, 53, 54, 60–67 Worsening quality of life, care dependency, cognitive decline, 6-minute walk test < 300 meters, validated performance status scale‡ |

26 (25) | Needs |

|

Decision support2, 11, 17–19, 23, 28–31, 35, 38, 40, 45, 47, 49, 55, 67, 68 Advance care planning or goals of care, hospice referral, care coordination, request for physician aid-in-dying |

19 (19) | Needs |

|

Psychosocial11, 17, 18, 28–33, 35, 38, 40, 42, 47, 67 Social needs, supportive counseling, spiritual issues, financial concerns |

15 (15) | Needs |

| Caregiver distress11, 18, 27, 30, 32, 35, 38, 42, 45, 48, 54, 55, 69 | 13 (13) | Needs |

| Cardiac cachexia4, 12, 21, 22, 27, 29, 34, 60–62, 65, 66 | 12 (12) | Needs |

| Request (by patient/family/care team) for palliative care4, 12, 18, 30, 38, 40, 45, 54, 55 | 9 (9) | Needs |

| Disease-based criteria | N(%) | Domain |

|

Cardiac stage4, 16–38, 60–67, 70–83 Persistent NYHA stage III or IV or AHA stage C or D symptoms |

46 (45) | Disease |

|

Hospital utilization2, 4, 6, 12, 16–22, 25–30, 32, 33, 37, 38, 40, 44, 54, 55, 61–64, 67, 72, 76, 81, 84–88 Repeated hospital admissions, intensive care unit admission, prolonged length of stay |

38 (37) | Disease |

|

Prognosis4, 6, 12, 18–20, 25, 27, 29, 30, 33, 35–38, 40, 41, 46, 59, 60, 67, 69, 71, 74, 79, 86, 87, 89–97 “Surprise question,”* life expectancy < 1 year, validated risk score† |

37 (36) | Disease |

|

Advanced cardiac therapies2, 4, 6, 12, 17, 22, 27, 34, 38, 40, 43, 60–62, 65, 66, 68, 72, 73, 76, 79, 83–85, 98–108 Left ventricular assist device, dependence on inotropes or other intravenous therapy, heart transplant, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, ineligible for or uninterested in advanced therapies |

36 (35) | Disease |

|

Disease progression4, 12, 21, 27, 30, 32–36, 40, 41, 46, 54, 56, 59–66, 69, 73, 75, 79, 81, 82, 85, 93, 108, 109 Inability to tolerate GDMT, frequent exacerbations despite GDMT, EF < 35%, Peak oxygen consumption < 14 cc/kg/min or < 60% predicted, EF < 20%, lack of further treatment options |

33 (32) | Disease |

|

Medical complications of heart failure4, 12, 16, 17, 19, 21, 25, 27, 34, 36, 38, 40, 41, 43, 46, 56, 62, 64–66, 72, 75, 85, 87, 88, 96, 109 Cardiorenal syndrome, cardiac arrest, hyponatremia, recurrent malignant arrhythmias, implantable device shock, persistent hypotension, persistent tachycardia, multi-organ failure, persistent S3 gallop |

27 (26) | Disease |

|

End of life17, 19, 22, 27–29, 35, 38, 42, 49, 61, 85, 99, 108, 110 Withdrawal of life-prolonging interventions, patient refusing treatment |

15 (15) | Disease |

| Comorbidities4, 12, 18, 26, 34, 36, 38, 56, 67, 72, 77, 87, 96 | 13 (13) | Disease |

| New diagnosis of heart failure27, 30, 40, 43, 111 | 5 (5) | Disease |

|

High risk procedures12, 17, 38, 40, 110 Cardiac surgery, percutaneous aortic valve replacement |

5 (5) | Disease |

|

Other12, 30, 32, 36, 44, 64, 78, 109 Advanced age, need for specialty assessment, specific further medical information, takes up cardiac team’s time |

8 (8) | N/A |

Sub-categories are listed beneath each category in order of frequency from highest to lowest.

Abbreviations: Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS), New York Heart Association (NYHA), American Heart Association (AHA), Guideline-Directed Medical Therapy (GDMT), Seattle Heart Failure Model (SHFM), North American Evaluation Study of Congestive Heart Failure and Pulmonary Artery Catheterization Effectiveness (ESCAPE), Get With The Guidelines-Heart Failure (GWTG-HF), Enhanced Feedback for Effective Cardiac Treatment (EFFECT), CardioVascular Medicine Heart Failure (CVM-HF), Palliative Performance Scale (PPS), World Health Organization (WHO)

“Surprise question” asked to clinicians is “Would you be surprised if this patient were to die within the next year?”

Elevated B-type natriuretic peptide, ESCAPE risk score > 50%, SHFM score > 85%, EFFECT score >33% 1-year mortality, GWTG-HF score > 58, CVM-HF index score > 12

Karnofsky performance status < 40, low PPS score, WHO performance status score 2/3

Statistical Analysis

We summarized the data using descriptive statistics, including counts, frequencies, and percentages.

Results

Literature Search

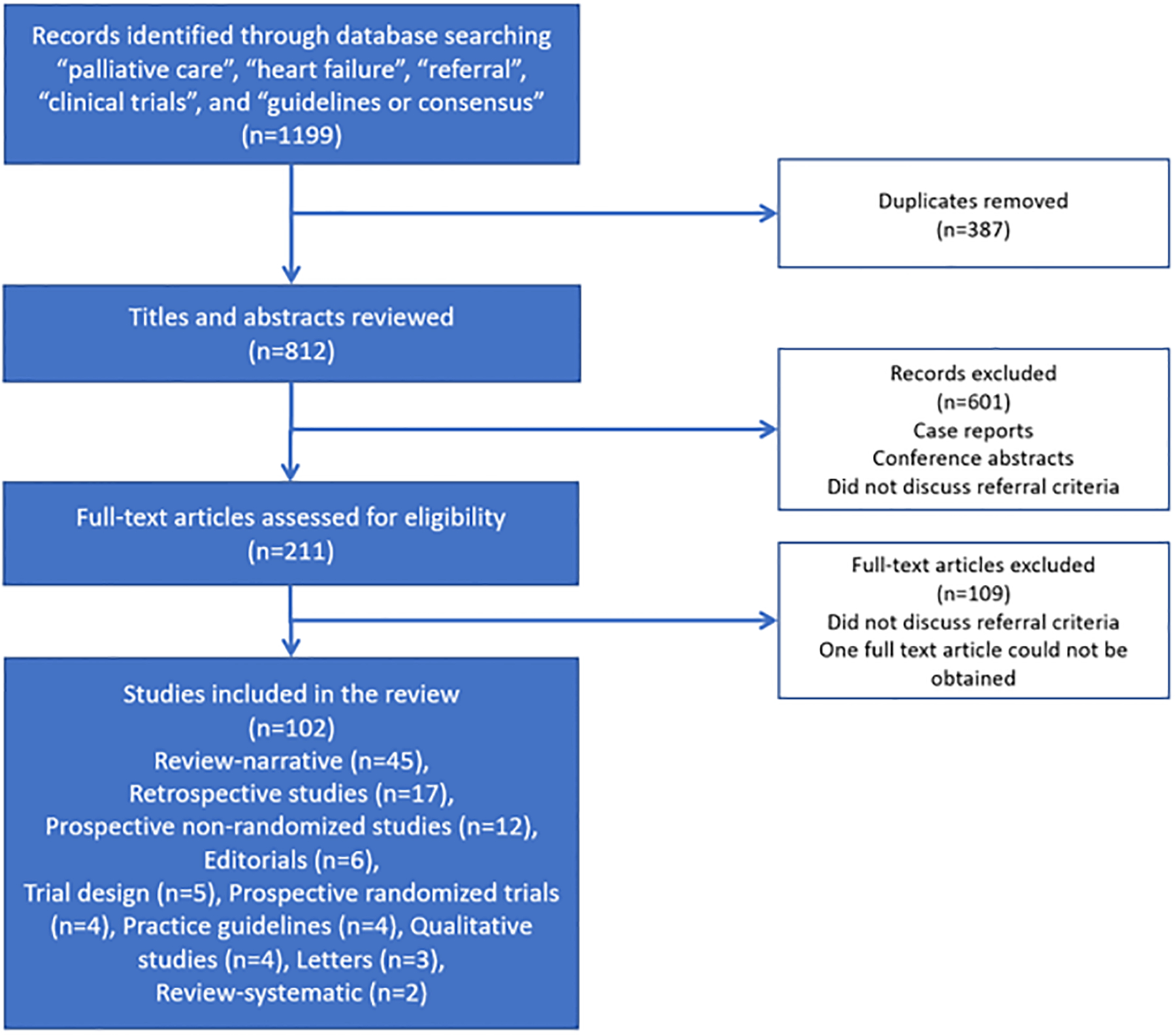

Our literature search identified 1199 articles. Three hundred eighty-seven were excluded as they represented duplicates, case reports, or conference abstracts. A total of 812 articles were reviewed, with a final sample of 102 (12.5%) publications included (Figure 1). The characteristics of the included articles are summarized in Table 2. A majority of the articles were from the United States (n=51 [50%]) and were published after 2010 (n=76 [75%]). The most prevalent article type were narrative reviews (n=45 [44%]). There were also 17 (17%) retrospective studies, 12 (12%) prospective non-randomized studies, 4 (4%) qualitative studies, and 4 (4%) prospective randomized trials. Majority of the articles were published in either cardiology (n=42 [41%]) or palliative care journals (n=38 [37%]).

Figure 1.

Study Flowchart

Table 2.

Publication Characteristics

| Article characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Article type | |

| Editorials | 6 (6) |

| Practice Guidelines | 4 (4) |

| Letters | 3 (3) |

| Prospective non-randomized studies | 12 (12) |

| Prospective randomized trials | 4 (4) |

| Qualitative studies | 4 (4) |

| Retrospective studies | 17 (17) |

| Review-narrative | 45 (44) |

| Review-systematic | 2 (2) |

| Trial design | 5 (5) |

| Publication year | |

| 2003–2010 | 26 (25) |

| 2011–2018 | 76 (75) |

| Journal type | |

| Cardiology journals | 42 (41) |

| Palliative care journals | 38 (37) |

| General medical journals | 8 (8) |

| Nursing journals | 8 (8) |

| Other | 6 (6) |

| Country | |

| United States | 51 (50) |

| United Kingdom | 28 (27) |

| Canada | 10 (10) |

| Sweden | 2 (2) |

| The Netherlands | 2 (2) |

| Ireland | 2 (2) |

| Australia | 1 (1) |

| China | 1 (1) |

| Czech Republic | 1 (1) |

| Denmark | 1 (1) |

| Germany | 1 (1) |

| Italy | 1 (1) |

| Spain | 1 (1) |

Categories of Referral Criteria

We identified 18 categories of referral criteria, which were broadly grouped according to “needs-based” (n=7) and “disease-based” (n=10) (Table 1).

The most commonly discussed criterion was “Physical or emotional symptoms” (n=51 [50%]), followed by “Cardiac stage” (n=46 [45%]), “Hospital utilization” (n=38 [37%]), “Prognosis” (n=37 [36%]), and “Advanced cardiac therapies” (n=36 [35%]); most articles mentioned more than one criteria category (n=78 [76%]). Ninety-two of the articles (90%) did not make an identifiable distinction between inpatient palliative care referral criteria and outpatient palliative care referral criteria. Only 2 (2%) articles mentioned inpatient, 4 (4%) articles outpatient, and 4 (4%) articles with both inpatient and outpatient.

Physical and emotional symptoms to trigger referral

This was the most prevalent category with 51 articles (50%). The most commonly discussed symptom was “mood disturbance” (n=15 [15%]), followed by “dyspnea” (n=11 [11%]). There were 3 articles (3%) that discussed using the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS), a validated symptom assessment tool, as a trigger for palliative care referral with a cutoff score of 7 or above (ESAS worst possible severity score is 10). However, 33 publications (32%) did not outline any specific symptoms to be considered as criteria, nor assessment scales or cutoffs.

Heart failure stage to trigger referral

Cardiac stage (NYHA functional class, AHA stages) was the next most prevalent category (n=46 [45%]). 43 articles (42%) recommended using NYHA functional class to trigger a referral. Thirty-one publications (30%) indicated NYHA functional class III and/or IV as referral criteria for palliative care consult and 12 articles (12%) indicated NYHA class IV only as a trigger to referral. Only 7 articles mentioned using AHA/ACC stages for referral (stages C/D, n=3 [3%]; stage D only, n=4 [4%]).

Hospital utilization as referral criteria

Thirty-eight articles (37%) comprise this category. Among these, eight (8%) articles specifically stated ≥2 hospitalizations in 12 months as a criterion, 3 (3%) articles referenced ≥2 admissions in the last 6 months, and 5 (5%) articles mentioned intensive care unit (ICU) admission as a possible referral criterion.

Prognosis as referral criteria

Among the 37 publications (36%) suggesting prognosis as a referral criterion (Table 4), the surprise question (“Would you be surprised if this patient were to die within the next year?”) was mentioned as a trigger for palliative care referral in 14 (14%) articles. Other investigators also suggested the use of mortality risk scores (n=10 [10%]). Seven (7%) articles listed life expectancy <1 year as referral criteria, whereas 4 articles (4%) were nonspecific in terms of defining prognosis.

Table 4.

Number of articles that recommended palliative care referral based on prognosis

| Sub-category | N (% = N/37) |

|---|---|

| “Surprise question”* | 14 (38) |

| Validated risk score† | 10 (27) |

| Life expectancy < 1 year | 7 (19) |

| Elevated BNP | 4 (11) |

| Unspecified | 4 (11) |

Abbreviations: Seattle Heart Failure Model (SHFM), North American Evaluation Study of Congestive Heart Failure and Pulmonary Artery Catheterization Effectiveness (ESCAPE), Get With The Guidelines-Heart Failure (GWTG-HF), Enhanced Feedback for Effective Cardiac Treatment (EFFECT), CardioVascular Medicine Heart Failure (CVM-HF), B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP)

“Surprise question” asked to clinicians is “Would you be surprised if this patient were to die within the next year?”

ESCAPE risk score > 50%, SHFM score > 85%, EFFECT score >33% 1-year mortality, GWTG-HF score > 58, CVM-HF index score > 12

Advanced cardiac therapies as referral criteria

This category had 36 articles (35%) and included insertion of left ventricular assist device (LVAD) (n=18 [18%]), dependence on inotropes or other intravenous therapy (n=11 [11%]), consideration for heart transplants (n=5 [5%]), and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator placement (n=4 [4%]) as potential triggers. Twelve (12%) articles indicated that patients who were ineligible for or uninterested in advanced therapies should be considered for palliative care referral.

Disease progression as referral criteria

This category had a total of 33 articles (32%) and included heart failure exacerbations (n=11 [11%]), inability to tolerate goal directed medical therapy (n=8 [8%]), and low left ventricular ejection fraction (n=7 [7%]). Five articles (5%) specified EF <35% and 2 (2%) suggested EF <20% as triggers.

Medical complications of heart failure

This category had a total of 27 (26%) publications. Complications warranting referral to palliative care included cardiorenal syndrome (n=11 [11%]), cardiac arrest (n=9 [9%]), hyponatremia (n=7 [7%]), implantable device shocks (n=7 [7%]), recurrent malignant arrhythmias (n=6 [6%]), persistent hypotension (n=5 [5%]), persistent tachycardia (n=3 [3%]), and multi-organ failure (n=3 [3%]).

Functional Decline

“Functional decline” was mentioned in 26 (25%) articles with few highlighted specific criteria other than functional decline. Four articles list specific performance scales as possible referral criteria (Karnofsky performance scale < 50, n=2 [2%]; Palliative performance scale, n=1 [1%]; WHO performance status 2/3, n=1 [1%]). Two publications (2%) listed the 6-min walk test < 300m as a potential trigger for referral. Care dependency was also referenced by 7 articles (7%). Four publications (4%) mentioned cognitive decline.

Decision Support

This category included 19 articles (19%), with 16 (16%) highlighting need for advance care planning/goals of care as potential referral criteria. Assistance for hospice referral (n=4 [4%]), care coordination (n=2 [2%]), and request for physician aid in dying (n=2 [2%]) were also mentioned as potential triggers.

Other Referral Criteria

We identified nine other referral categories that were mentioned less commonly. Five of the nine categories were mentioned in ≤15% of the articles (“End of life”, n=15 [15%]; “Psychosocial”, n=15 [15%]; “Caregiver distress”, n=13 [13%]; “Comorbidities”, n=13 [13%]; and “Cardiac cachexia”, n=12 [12%]). The other four categories each had less than 10% of articles (“Request by patient/family/care team for palliative care”, n=9 [9%]; “New diagnosis of heart failure”, n=5 [5%]; “High risk procedures”, n=5 [5%]; and “Other”, n=8 [8%]). Please refer to Table 1 for specific subcategories, if available, for each of the above categories listed.

Discussion

We conducted a systematic review of the literature in order to examine what criteria have been considered for initiating a palliative care referral in heart failure. With our final sample of 102 articles, we discovered a wide array of reasons for which to refer heart failure patients to specialist palliative care. A large number of categories for referral criteria were identified, covering 18 different themes. This observation suggests that these articles recognized a multitude of opportunities along the disease trajectory to refer patients; however, it also underscores that there was no clearly established consensus. The most commonly noted criteria category was physical or emotional symptoms, followed by cardiac stage, hospital utilization, prognosis, advanced cardiac therapies, and disease progression. We found no clear universal consensus on referral criteria for patients with heart failure. As such, our goal was to map all the criteria found without preference for one set of criteria over another. Some investigators proposed that a palliative care referral should be considered based on a patient’s palliative care needs, while others support referrals based on disease trajectory or other factors. Findings from this study would facilitate further research to identify which of these criteria should be considered to trigger a referral.

“Physical or emotional symptoms” was the most prevalent referral category highlighting the increasing awareness of the high symptom burden among heart failure patients, and the role of palliative care in symptom management11. Utilizing a holistic and inter-disciplinary approach4, specialist palliative care can provide support for patients and their families concurrently with cardiology teams. However, despite acknowledging the need for referral for symptom management, only a few articles have explicitly described which symptoms and how they should be assessed, as well as the cutoff for referral for specialist palliative care4, 24. For example, 3 randomized controlled trials of antidepressants in patients who develop depression in the setting of heart failure have been negative, and a rigorous symptom-based, collaborative-care management approach did not significantly improve outcomes for patients with heart failure112. Further research is needed.

Categories such as “Cardiac stage”, “Advanced cardiac therapies”, “Disease progression”, and “Medical complications of heart failure” were also commonly mentioned as potential criteria for palliative care referral. However, the specifics remain elusive (ex., inability to tolerate goal directed medical therapy) with only a few mentioning definitive referral cutoffs (ex., LVEF <35%)4, 73. When a cutoff was proposed, the timing of palliative care referral seemed to be variable, as patients with stage D/NYHA class III-IV heart failure have a 1-year mortality rate of > 50%, and those on intravenous inotrope therapy have a median survival of 461 to 584 days113, 114.

Among the articles that discussed prognosis as a referral criterion, a majority suggested a cutoff of 1 year as potential trigger, with multiple investigators recommending the use of the “surprise question” (“Would you be surprised if this patient were to die within the next year?”) for screening. However, prognostication of survival in heart failure is particularly challenging because of its unpredictable trajectory. The sensitivity, specificity and overall accuracy of the surprise question may depend on the patient population and clinician experience115. Quantitative risk models have poor performance at prospectively identifying individuals who will die in the next year116. And data shows that clinicians are equally inaccurate while also bringing additional biases to prognostication117.

Although multiple guidelines for patients with heart failure supported the integration of palliative care for patients with heart failure, there appeared to be no consensus between these professional bodies on when patients should be referred. For example, the 2013 ACC/AHA Guidelines for the Management of Heart Failure stated, “Consider palliative care or hospice care throughout the hospital stay, before discharge, at the first visit after discharge, and during follow-up in selected patients. Palliative and supportive care are effective for patients with symptomatic advanced heart failure to improve quality of life”7. The 2013 ISHLT Guidelines for Mechanical Circulatory Support suggested that a palliative care referral should considered during evaluation for mechanical circulatory support implantation9. The 2016 ESC Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure recommended that a palliative care approach “should be introduced early in the disease trajectory and increased as the disease progresses ”10. The European Association for Palliative Care Task Force recently published an expert position statement which supports the use of need-based criteria instead of time-based criteria for referral118.

Despite guidelines recommending early integration of palliative care into heart failure management, many of the suggested referral criteria identified in our study involved patients with advanced heart failure far into the disease trajectory. This could be in part due to primary palliative care being provided by non-palliative care specialists (as specialty palliative care is typically reserved for more complex and higher level palliative needs). Furthermore, throughout our systematic review, there were very few articles (10%) proposing a clear distinction between criteria meant for inpatient versus outpatient specialist palliative care referral. Since outpatient referrals facilitate earlier access to palliative care services, such timeliness is threatened by the lack of consensus and clarity in this area. Importantly, palliative care is most effective when provided earlier to allow for timely symptom management, longitudinal patient education and monitoring, psychological interventions, and support advance care planning119–121; however, more randomized trials are needed to confirm this in the heart failure population. Similar to palliative care for cancer patients, referral criteria would ideally be focused on: 1) earlier timing of appropriate referral (and not rely solely on prognostication) and 2) consideration of needs-based criteria rather than disease-based criteria14, 122, 123. Given limited available palliative care resources, and considering the large volume of potential heart failure patients, it will be impossible for specialist palliative care providers to see all the potential heart failure patients who are triggered by the 18 referral categories identified. Consequently, finding the most effective and eventually validated referral criteria at the appropriate time will be a critical factor to ensure that those with the most complex palliative needs are referred at the ideal time to specialist palliative care providers in order to optimize care. Further research is needed to identify the right time, the right reason/indication for palliative care referral for heart failure patients.

Our systematic review has several limitations. First, a large proportion of articles were narrative reviews based on expert opinion. There were very few empiric studies in the literature that examined how triggered referral using specific criteria impacted patient outcomes compared to routine referral. In a randomized clinical trial, Rogers et al. compared routine outpatient palliative care referral versus usual care for 150 patients with high Evaluation Study of Congestive Heart Failure and Pulmonary Artery Catheterization Effectiveness risk scores6. They found that timely palliative care involvement was associated with a significant improvement in quality of life, depression and anxiety. However, another randomized trial by Hopp et al. comparing inpatient palliative care referral to usual care for hospitalized patients with stage III/IV heart failure and a 1 year mortality risk of >=33% based on the Enhanced Feedback for Effective Cardiac Treatment score reported no significant difference in the proportion of patients choosing comfort-oriented care74. Further research is needed to examine outcomes associated with automatic referral and our study represents only a first step to developing standardized referral criteria. Second, we did not conduct a hand search or search grey literature, thus, may not have captured all available data. Third, we included certain eligibility criteria of randomized trials as possible referral criteria, although, they may not have been specifically designed for this.

We identified 18 categories of palliative care referral criteria for patients with heart failure. These were broadly classified as either need-based criteria or disease-based criteria. This diversity highlights the many reasons to involve palliative care and at the same time the lack of consensus on who and when patients should be referred. As we move towards a more personalized approach to medical care, it is important to refer the right patient to the right service at the right time. Theoretically, this would help to triage the limited available palliative care resources, while concurrently standardizing appropriate and timely palliative care access. Referral criteria are being examined in cancer patients but few studies have been conducted in heart failure patients. Further research is needed to delineate appropriate and timely triggers for palliative care referral for heart failure patients.

Supplementary Material

Table 3.

Number of articles that recommended palliative care referral for physical or emotional symptoms

| Sub-category | N (% = N/51) |

|---|---|

| Mood disturbance | 15 (29) |

| Dyspnea | 11 (22) |

| Fatigue | 3 (6) |

| Refractory pain | 4 (8) |

| Weight loss | 4 (8) |

| Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale > 7 | 3 (6) |

| Refractory angina | 2 (4) |

| Insomnia | 1 (2) |

| Frailty | 1 (2) |

| Unspecified | 33 (65) |

Table 5.

Number of articles that recommended palliative care referral based on need for advanced cardiac therapies

| Sub-category | N (% = N/36) |

|---|---|

| Consideration of left ventricular assist device | 18 (50) |

| Ineligible for or uninterested in advanced therapies | 12 (33) |

| Dependence on inotropes or other intravenous therapy | 11 (31) |

| Consideration of heart transplant | 5 (14) |

| Consideration of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator placement | 4 (11) |

| Left ventricular assist device-associated complications | 1 (3) |

| Rejection after transplant | 1 (3) |

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE.

What is new?

This systematic review identified eighteen categories of potential triggers for specialist palliative care referral, including 7 needs-based and 10 disease-based criteria.

Our findings highlight the lack of consensus on who and when patients with heart failure should be referred to specialist palliative care, which may explain why palliative care access is currently highly variable and often delayed.

What are the clinical implications?

This study serves as a first step towards developing a set of criteria to facilitate timely palliative care referral for patients with heart failure, with the long-term goals of standardizing palliative care access, personalizing care choices, improving patients’ quality of life, and triaging the limited palliative care resources.

Funding:

Dr. Hui reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Cancer Institute (R01CA214960-01A1; R01CA225701-01A1; R01CA231471-01A1) and National Institute of Nursing Research (1R21NR016736-01), Helsinn Therapeutics and Insys Therapeutics during the conduct of the study.

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ESAS

Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale

- NYHA

New York Heart Association

- AHA

American Heart Association

- GDMT

Guideline-Directed Medical Therapy

- SHFM

Seattle Heart Failure Model

- ESCAPE

North American Evaluation Study of Congestive Heart Failure and Pulmonary Artery Catheterization Effectiveness

- GWTG-HF

Get With The Guidelines-Heart Failure

- EFFECT

Enhanced Feedback for Effective Cardiac Treatment

- CVM-HF

CardioVascular Medicine Heart Failure

- PPS

Palliative Performance Scale

- WHO

World Health Organization

- BNP

B-type natriuretic peptide

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest. The funding organizations had no role in the design or conduct of the study; in collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or in preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

References:

- 1.Ponikowski P, Anker SD, AlHabib KF, Cowie MR, Force TL, Hu S, Jaarsma T, Krum H, Rastogi V, Rohde LE, Samal UC, Shimokawa H, Budi Siswanto B, Sliwa K and Filippatos G. Heart failure: preventing disease and death worldwide. ESC Heart Fail. 2014;1:4–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McIlvennan CK and Allen LA. Palliative care in patients with heart failure. BMJ. 2016;353:i1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou K and Mao Y. Palliative care in heart failure : A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Herz. 2019;44:440–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiskar K, Toma M and Rush B. Palliative care in heart failure. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2018;28:445–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. WHO Definition of Palliative Care. 2019; http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/ Last accessed June 23, 2020.

- 6.Rogers JG, Patel CB, Mentz RJ, Granger BB, Steinhauser KE, Fiuzat M, Adams PA, Speck A, Johnson KS, Krishnamoorthy A, Yang H, Anstrom KJ, Dodson GC, Taylor DH Jr., Kirchner JL, Mark DB, O’Connor CM and Tulsky JA. Palliative Care in Heart Failure: The PAL-HF Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:331–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Writing Committee M, Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE Jr., Drazner MH, Fonarow GC, Geraci SA, Horwich T, Januzzi JL, Johnson MR, Kasper EK, Levy WC, Masoudi FA, McBride PE, McMurray JJ, Mitchell JE, Peterson PN, Riegel B, Sam F, Stevenson LW, Tang WH, Tsai EJ, Wilkoff BL and American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice G. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128:e240–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evangelista LS, Lombardo D, Malik S, Ballard-Hernandez J, Motie M and Liao S. Examining the effects of an outpatient palliative care consultation on symptom burden, depression, and quality of life in patients with symptomatic heart failure. J Card Fail. 2012;18:894–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feldman D, Pamboukian SV, Teuteberg JJ, Birks E, Lietz K, Moore SA, Morgan JA, Arabia F, Bauman ME, Buchholz HW, Deng M, Dickstein ML, El-Banayosy A, Elliot T, Goldstein DJ, Grady KL, Jones K, Hryniewicz K, John R, Kaan A, Kusne S, Loebe M, Massicotte MP, Moazami N, Mohacsi P, Mooney M, Nelson T, Pagani F, Perry W, Potapov EV, Eduardo Rame J, Russell SD, Sorensen EN, Sun B, Strueber M, Mangi AA, Petty MG, Rogers J, International Society for H and Lung T. The 2013 International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation Guidelines for mechanical circulatory support: executive summary. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32:157–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McMurray JJ, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, Auricchio A, Bohm M, Dickstein K, Falk V, Filippatos G, Fonseca C, Gomez-Sanchez MA, Jaarsma T, Kober L, Lip GY, Maggioni AP, Parkhomenko A, Pieske BM, Popescu BA, Ronnevik PK, Rutten FH, Schwitter J, Seferovic P, Stepinska J, Trindade PT, Voors AA, Zannad F, Zeiher A and Guidelines ESCCfP. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1787–1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gelfman LP, Kavalieratos D, Teuteberg WG, Lala A and Goldstein NE. Primary palliative care for heart failure: what is it? How do we implement it? Heart Fail Rev. 2017;22:611–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meyers DE and Goodlin SJ. End-of-Life Decisions and Palliative Care in Advanced Heart Failure. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32:1148–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Warraich HJ, Wolf SP, Mentz RJ, Rogers JG, Samsa G and Kamal AH. Characteristics and Trends Among Patients With Cardiovascular Disease Referred to Palliative Care. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e192375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hui D, Meng YC, Bruera S, Geng Y, Hutchins R, Mori M, Strasser F and Bruera E. Referral Criteria for Outpatient Palliative Cancer Care: A Systematic Review. Oncologist. 2016;21:895–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG and Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lowey SE. Palliative Care in the Management of Patients with Advanced Heart Failure. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2018;1067:295–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klinedinst R, Kornfield ZN and Hadler RA. Palliative Care for Patients With Advanced Heart Disease. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2019;33:833–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janssen DJA, Johnson MJ and Spruit MA. Palliative care needs assessment in chronic heart failure. Current opinion in supportive and palliative care. 2018;12:25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hritz CM. Palliative Therapy in Heart Failure. Heart Fail Clin. 2018;14:617–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ng AY, Wong FK and Lee PH. Effects of a transitional palliative care model on patients with end-stage heart failure: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2016;17:173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gavazzi A, De Maria R, Manzoli L, Bocconcelli P, Di Leonardo A, Frigerio M, Gasparini S, Humar F, Perna G, Pozzi R, Svanoni F, Ugolini M and Deales A. Palliative needs for heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Results of a multicenter observational registry. Int J Cardiol. 2015;184:552–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campbell RT, Jackson CE, Wright A, Gardner RS, Ford I, Davidson PM, Denvir MA, Hogg KJ, Johnson MJ, Petrie MC and McMurray JJ. Palliative care needs in patients hospitalized with heart failure (PCHF) study: rationale and design. ESC Heart Fail. 2015;2:25–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gelfman LP, Kalman J and Goldstein NE. Engaging heart failure clinicians to increase palliative care referrals: overcoming barriers, improving techniques. J Palliat Med. 2014;17:753–760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Timmons MJ, MacIver J, Alba AC, Tibbles A, Greenwood S and Ross HJ. Using heart failure instruments to determine when to refer heart failure patients to palliative care. J Palliat Care. 2013;29:217–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haga K, Murray S, Reid J, Ness A, O’Donnell M, Yellowlees D and Denvir MA. Identifying community based chronic heart failure patients in the last year of life: a comparison of the Gold Standards Framework Prognostic Indicator Guide and the Seattle Heart Failure Model. Heart. 2012;98:579–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buck HG and Zambroski CH. Upstreaming palliative care for patients with heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2012;27:147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson MJ and Gadoud A. Palliative care for people with chronic heart failure: when is it time? J Palliat Care. 2011;27:37–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Howlett JG. Palliative care in heart failure: addressing the largest care gap. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2011;26:144–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bekelman DB, Nowels CT, Allen LA, Shakar S, Kutner JS and Matlock DD. Outpatient palliative care for chronic heart failure: a case series. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:815–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Selman L, Harding R, Beynon T, Hodson F, Hazeldine C, Coady E, Gibbs L and Higginson IJ. Modelling services to meet the palliative care needs of chronic heart failure patients and their families: current practice in the UK. Palliat Med. 2007;21:385–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson MJ and Houghton T. Palliative care for patients with heart failure: description of a service. Palliat Med. 2006;20:211–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gibbs LM, Khatri AK and Gibbs JS. Survey of specialist palliative care and heart failure: September 2004. Palliat Med. 2006;20:603–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Daley A, Matthews C and Williams A. Heart failure and palliative care services working in partnership: report of a new model of care. Palliat Med. 2006;20:593–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turris M and Rauscher C. Palliative trajectory markers for end-stage heart failure. Or “oh Toto. This doesn’t look like kancerous!”. Can J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2005;15:17–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Albert NM. Referral for palliative care in advanced heart failure. Prog Palliative Care. 2008;16:220–228. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fonarow GC. Clinical Risk Prediction Tools in Patients Hospitalized with Heart Failure. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2012;13:e14–e23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson MJ. Management of end stage cardiac failure. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83:395–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Slawnych M. New Dimensions in Palliative Care Cardiology. Can J Cardiol. 2018;34:914–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Campbell RT, Petrie MC, Jackson CE, Jhund PS, Wright A, Gardner RS, Sonecki P, Pozzi A, McSkimming P, McConnachie A, Finlay F, Davidson P, Denvir MA, Johnson MJ, Hogg KJ and McMurray JJV. Which patients with heart failure should receive specialist palliative care? Eur J Heart Fail. 2018;20:1338–1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Psotka MA, McKee KY, Liu AY, Elia G and De Marco T. Palliative Care in Heart Failure: What Triggers Specialist Consultation? Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2017;60:215–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McClung JA. End-of-Life Care in the Treatment of Heart Failure in Older Adults. Heart Fail Clin. 2017;13:633–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hupcey JE, Kitko L and Alonso W. Palliative Care in Heart Failure. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2015;27:577–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beattie JM. Advanced heart failure, communication and the Goldilocks principle. Current opinion in supportive and palliative care. 2015;9:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dionne-Odom JN, Kono A, Frost J, Jackson L, Ellis D, Ahmed A, Azuero A and Bakitas M. Translating and testing the ENABLE: CHF-PC concurrent palliative care model for older adults with heart failure and their family caregivers. J Palliat Med. 2014;17:995–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Waller A, Girgis A, Davidson PM, Newton PJ, Lecathelinais C, Macdonald PS, Hayward CS and Currow DC. Facilitating needs-based support and palliative care for people with chronic heart failure: preliminary evidence for the acceptability, inter-rater reliability, and validity of a needs assessment tool. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45:912–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McClung JA. End-of-life care in the treatment of advanced heart failure in the elderly. Cardiol Rev. 2013;21:9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bakitas M, Macmartin M, Trzepkowski K, Robert A, Jackson L, Brown JR, Dionne-Odom JN and Kono A. Palliative care consultations for heart failure patients: how many, when, and why? J Card Fail. 2013;19:193–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith D. Development of an end-of-life care pathway for patients with advanced heart failure in a community setting. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2012;18:295–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schwarz ER, Baraghoush A, Morrissey RP, Shah AB, Shinde AM, Phan A and Bharadwaj P. Pilot study of palliative care consultation in patients with advanced heart failure referred for cardiac transplantation. J Palliat Med. 2012;15:12–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hogg KJ and Jenkins SM. Prognostication or identification of palliative needs in advanced heart failure: where should the focus lie? Heart. 2012;98:523–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McKelvie RS, Moe GW, Cheung A, Costigan J, Ducharme A, Estrella-Holder E, Ezekowitz JA, Floras J, Giannetti N, Grzeslo A, Harkness K, Heckman GA, Howlett JG, Kouz S, Leblanc K, Mann E, O’Meara E, Rajda M, Rao V, Simon J, Swiggum E, Zieroth S, Arnold JM, Ashton T, D’Astous M, Dorian P, Haddad H, Isaac DL, Leblanc MH, Liu P, Sussex B and Ross HJ. The 2011 Canadian Cardiovascular Society heart failure management guidelines update: focus on sleep apnea, renal dysfunction, mechanical circulatory support, and palliative care. Can J Cardiol. 2011;27:319–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Martin DE. Palliation of dyspnea in patients with heart failure. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2011;30:144–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ezekowitz JA, Thai V, Hodnefield TS, Sanderson L and Cujec B. The correlation of standard heart failure assessment and palliative care questionnaires in a multidisciplinary heart failure clinic. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;42:379–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.O’Leary N, Murphy NF, O’Loughlin C, Tiernan E and McDonald K. A comparative study of the palliative care needs of heart failure and cancer patients. Eur J Heart Fail. 2009;11:406–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Harding R, Beynon T, Hodson F, Coady E, Kinirons M, Selman L and Higginson I. Provision of palliative care for chronic heart failure inpatients: how much do we need? BMC Palliat Care. 2009;8:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lopez-Candales AL, Carron C and Schwartz J. Need for hospice and palliative care services in patients with end-stage heart failure treated with intermittent infusion of inotropes. Clin Cardiol. 2004;27:23–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Johnson MJB S Palliative and end-of-life care for patients with chronic heart failure and chronic lung disease. Clin Med J R Coll Phys Lond. 2010;10:286–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Johnson MJM A; Butler J; Rogers A; Sam E; Fuller A; Beattie JM Heart failure specialist nurses’ use of palliative care services: a comparison of surveys across England in 2005 and 2010. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing : journal of the Working Group on Cardiovascular Nursing of the European Society of Cardiology. 2012;11:190–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.O’Keeffe ST, Canavan M. Palliative care for cardiac failure in Ireland. Eur Geriatr Med. 2011;2:46–47. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brannstrom M and Boman K. A new model for integrated heart failure and palliative advanced homecare--rationale and design of a prospective randomized study. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2013;12:269–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dalgaard KM, Bergenholtz H, Nielsen ME and Timm H. Early integration of palliative care in hospitals: A systematic review on methods, barriers, and outcome. Palliative & supportive care. 2014;12:495–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jaarsma T, Beattie JM, Ryder M, Rutten FH, McDonagh T, Mohacsi P, Murray SA, Grodzicki T, Bergh I, Metra M, Ekman I, Angermann C, Leventhal M, Pitsis A, Anker SD, Gavazzi A, Ponikowski P, Dickstein K, Delacretaz E, Blue L, Strasser F, McMurray J and Advanced Heart Failure Study Group of the HFAotESC. Palliative care in heart failure: a position statement from the palliative care workshop of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail. 2009;11:433–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Riley JP and Beattie JM. Palliative care in heart failure: facts and numbers. ESC Heart Fail. 2017;4:81–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Davidson PM, Macdonald PS, Newton PJ and Currow DC. End stage heart failure patients - palliative care in general practice. Aust Fam Physician. 2010;39:916–920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.O’Leary N. The comparative palliative care needs of those with heart failure and cancer patients. Current opinion in supportive and palliative care. 2009;3:241–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Martin Gřiva ML, Jiří Šťastný. Palliative care in cardiology. Cor Vasa. 2015;57:e39–e44. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Boyd KJ, Worth A, Kendall M, Pratt R, Hockley J, Denvir M and Murray SA. Making sure services deliver for people with advanced heart failure: a longitudinal qualitative study of patients, family carers, and health professionals. Palliat Med. 2009;23:767–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fang JC, Ewald GA, Allen LA, Butler J, Westlake Canary CA, Colvin-Adams M, Dickinson MG, Levy P, Stough WG, Sweitzer NK, Teerlink JR, Whellan DJ, Albert NM, Krishnamani R, Rich MW, Walsh MN, Bonnell MR, Carson PE, Chan MC, Dries DL, Hernandez AF, Hershberger RE, Katz SD, Moore S, Rodgers JE, Rogers JG, Vest AR, Givertz MM and Heart Failure Society of America Guidelines C. Advanced (stage D) heart failure: a statement from the Heart Failure Society of America Guidelines Committee. J Card Fail. 2015;21:519–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hauptman PJ and Havranek EP. Integrating palliative care into heart failure care. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:374–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wells R, Stockdill ML, Dionne-Odom JN, Ejem D, Burgio KL, Durant RW, Engler S, Azuero A, Pamboukian SV, Tallaj J, Swetz KM, Kvale E, Tucker RO and Bakitas M. Educate, Nurture, Advise, Before Life Ends Comprehensive Heartcare for Patients and Caregivers (ENABLE CHF-PC): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2018;19:422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Treece J, Chemchirian H, Hamilton N, Jbara M, Gangadharan V, Paul T and Baumrucker SJ. A Review of Prognostic Tools in Heart Failure. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018;35:514–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lewin WH, Cheung W, Horvath AN, Haberman S, Patel A and Sullivan D. Supportive Cardiology: Moving Palliative Care Upstream for Patients Living with Advanced Heart Failure. J Palliat Med. 2017;20:1112–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Szekendi MK, Vaughn J, Lal A, Ouchi K and Williams MV. The Prevalence of Inpatients at 33 U.S. Hospitals Appropriate for and Receiving Referral to Palliative Care. J Palliat Med. 2016;19:360–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hopp FP, Zalenski RJ, Waselewsky D, Burn J, Camp J, Welch RD and Levy P. Results of a Hospital-Based Palliative Care Intervention for Patients With an Acute Exacerbation of Chronic Heart Failure. J Card Fail. 2016;22:1033–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Thorvaldsen T, Benson L, Stahlberg M, Dahlstrom U, Edner M and Lund LH. Triage of patients with moderate to severe heart failure: who should be referred to a heart failure center? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:661–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mentz RJ, Tulsky JA, Granger BB, Anstrom KJ, Adams PA, Dodson GC, Fiuzat M, Johnson KS, Patel CB, Steinhauser KE, Taylor DH Jr., O’Connor CM and Rogers JG. The palliative care in heart failure trial: rationale and design. Am Heart J. 2014;168:645–651 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lindvall C, Hultman TD and Jackson VA. Overcoming the barriers to palliative care referral for patients with advanced heart failure. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e000742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Charnock LA. End of life care services for patients with heart failure. Nurs Stand. 2014;28:35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Adler ED, Goldfinger JZ, Kalman J, Park ME and Meier DE. Palliative care in the treatment of advanced heart failure. Circulation. 2009;120:2597–2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Paes P. A pilot study to assess the effectiveness of a palliative care clinic in improving the quality of life for patients with severe heart failure. Palliat Med. 2005;19:505–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rosenfeld K and Rasmussen J. Palliative care management: a Veterans Administration demonstration project. J Palliat Med. 2003;6:831–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rabow MW, Petersen J, Schanche K, Dibble SL and McPhee SJ. The comprehensive care team: a description of a controlled trial of care at the beginning of the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2003;6:489–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Behnam Bozorgnia PJM. Current Management of Heart Failure. When to Refer to Heart Failure Specialist and When Hospice is the Best Option. Med Clin North Am. 2015;99:863–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gelfman LP, Bakitas M, Warner Stevenson L, Kirkpatrick JN and Goldstein NE. The State of the Science on Integrating Palliative Care in Heart Failure. J Palliat Med. 2017;20:592–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.McDonagh TA. Challenges in advanced chronic heart failure: drug therapy. Future Cardiol. 2008;4:517–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fasolino T and Phillips M. Utilizing Risk Readmission Assessment Tool for Nonhospice Palliative Care Consults in Heart Failure Patients. J Palliat Med. 2016;19:1098–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Denvir MA, Murray SA and Boyd KJ. Future care planning: a first step to palliative care for all patients with advanced heart disease. Heart. 2015;101:1002–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lemond L and Allen LA. Palliative care and hospice in advanced heart failure. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2011;54:168–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Patel RB, Warraich HJ, Butler J and Vaduganathan M. Surprise, surprise: improving the referral pathway to palliative care interventions in advanced heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21:235–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ng Fat Hing N, MacIver J, Chan D, Liu H, Lu YTL, Malik A, Wang VN, Levy WC, Ross HJ and Alba AC. Utility of the Seattle Heart Failure Model for palliative care referral in advanced ambulatory heart failure. BMJ supportive & palliative care. 2018; 10.1136/bmjspcare-2018-001626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Snow R, Vogel K, Vanderhoff B, Kelch BP and Ferris FD. A Prognostic Indicator for Patients Hospitalized with Heart Failure. J Palliat Med. 2016;19:1320–1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.AbouEzzeddine OF, French B, Mirzoyev SA, Jaffe AS, Levy WC, Fang JC, Sweitzer NK, Cappola TP and Redfield MM. From statistical significance to clinical relevance: A simple algorithm to integrate brain natriuretic peptide and the Seattle Heart Failure Model for risk stratification in heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2016;35:714–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Steel A and Bakhai A. Proposal for routine use of mortality risk prediction tools to promote early end of life planning in heart failure patients and facilitate integrated care. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:280–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Murray S and Boyd K. Using the ‘surprise question’ can identify people with advanced heart failure and COPD who would benefit from a palliative care approach. Palliat Med. 2011;25:382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Small N, Gardiner C, Barnes S, Gott M, Payne S, Seamark D and Halpin D. Using a prediction of death in the next 12 months as a prompt for referral to palliative care acts to the detriment of patients with heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Palliat Med. 2010;24:740–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Berry JI. Hospice and heart disease: missed opportunities. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2010;24:23–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sam Straw RB, John Gierula, Maria F. Paton, Aaron Koshy, Richard Cubbon, Michael Drozd, Mark Kearney, Klaus K. Witte. Predicting one-year mortality in heart failure using the ‘Surprise Question’: a prospective pilot study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21:227–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Woodburn JL, Staley LL, Wordingham SE, Spadafore J, Boldea E, Williamson S, Hollenbach S, Ross HM, Steidley DE and Pajaro OE. Destination Therapy: Standardizing the Role of Palliative Medicine and Delineating the DT-LVAD Journey. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;57:330–340 e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Crespo-Leiro MG, Metra M, Lund LH, Milicic D, Costanzo MR, Filippatos G, Gustafsson F, Tsui S, Barge-Caballero E, De Jonge N, Frigerio M, Hamdan R, Hasin T, Hulsmann M, Nalbantgil S, Potena L, Bauersachs J, Gkouziouta A, Ruhparwar A, Ristic AD, Straburzynska-Migaj E, McDonagh T, Seferovic P and Ruschitzka F. Advanced heart failure: a position statement of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018;20:1505–1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bayoumi E, Sheikh F and Groninger H. Palliative care in cardiac transplantation: an evolving model. Heart Fail Rev. 2017;22:605–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Barrett T. Cardiac Palliative Medicine. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2017;14:428–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Katz JN, Waters SB, Hollis IB and Chang PP. Advanced therapies for end-stage heart failure. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2015;11:63–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Fendler TJ, Swetz KM and Allen LA. Team-based Palliative and End-of-life Care for Heart Failure. Heart Fail Clin. 2015;11:479–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.McGonigal P. Improving end-of-life care for ventricular assist devices (VAD) patients: paradox or protocol?*. Omega (Westport). 2013;67:161–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Swetz KM, Freeman MR, AbouEzzeddine OF, Carter KA, Boilson BA, Ottenberg AL, Park SJ and Mueller PS. Palliative medicine consultation for preparedness planning in patients receiving left ventricular assist devices as destination therapy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86:493–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Rizzieri AG, Verheijde JL, Rady MY and McGregor JL. Ethical challenges with the left ventricular assist device as a destination therapy. Philos Ethics Humanit Med. 2008;3:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Stuart B. Palliative care and hospice in advanced heart failure. J Palliat Med. 2007;10:210–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Janssens SR U. The chronic critically ill patient from the cardiologist’s perspective. Med Klin Intensivmed Notfmed. 2013;108:267–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Coventry PA, Grande GE, Richards DA and Todd CJ. Prediction of appropriate timing of palliative care for older adults with non-malignant life-threatening disease: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2005;34:218–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lauck SB, Gibson JA, Baumbusch J, Carroll SL, Achtem L, Kimel G, Nordquist C, Cheung A, Boone RH, Ye J, Wood DA and Webb JG. Transition to palliative care when transcatheter aortic valve implantation is not an option: opportunities and recommendations. Current opinion in supportive and palliative care. 2016;10:18–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bekelman DB, Nowels CT, Retrum JH, Allen LA, Shakar S, Hutt E, Heyborne T, Main DS and Kutner JS. Giving voice to patients’ and family caregivers’ needs in chronic heart failure: implications for palliative care programs. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:1317–1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Bekelman DB, Allen LA, McBryde CF, Hattler B, Fairclough DL, Havranek EP, Turvey C and Meek PM. Effect of a Collaborative Care Intervention vs Usual Care on Health Status of Patients With Chronic Heart Failure: The CASA Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:511–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Friedrich EB and Bohm M. Management of end stage heart failure. Heart. 2007;93:626–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Mody BP, Zaid S, Khan MH, Cooper H, Ahn C, Aronow WS and Lanier GM. Continuous Outpatient Intravenous Inotrope Therapy: Milrinone is Associated with Improved Survival Compared to Dobutamine Irrespective of Indication. J Card Fail. 2019;25:S6–S6. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Downar J, Goldman R, Pinto R, Englesakis M and Adhikari NK. The “surprise question” for predicting death in seriously ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2017;189:E484–E493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Allen LA, Matlock DD, Shetterly SM, Xu S, Levy WC, Portalupi LB, McIlvennan CK, Gurwitz JH, Johnson ES, Smith DH and Magid DJ. Use of Risk Models to Predict Death in the Next Year Among Individual Ambulatory Patients With Heart Failure. JAMA cardiology. 2017;2:435–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Yamokoski LM, Hasselblad V, Moser DK, Binanay C, Conway GA, Glotzer JM, Hartman KA, Stevenson LW and Leier CV. Prediction of rehospitalization and death in severe heart failure by physicians and nurses of the ESCAPE trial. J Card Fail. 2007;13:8–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Sobanski PZ, Alt-Epping B, Currow DC, Goodlin SJ, Grodzicki T, Hogg K, Janssen DJA, Johnson MJ, Krajnik M, Leget C, Martinez-Selles M, Moroni M, Mueller PS, Ryder M, Simon ST, Stowe E and Larkin PJ. Palliative Care for people living with heart failure - European Association for Palliative Care Task Force expert position statement. Cardiovasc Res. 2020;116:12–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, Dahlin CM, Blinderman CD, Jacobsen J, Pirl WF, Billings JA and Lynch TJ. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Temel JS, Greer JA, Admane S, Gallagher ER, Jackson VA, Lynch TJ, Lennes IT, Dahlin CM and Pirl WF. Longitudinal perceptions of prognosis and goals of therapy in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: results of a randomized study of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2319–2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Hui D, Hannon BL, Zimmermann C and Bruera E. Improving patient and caregiver outcomes in oncology: Team-based, timely, and targeted palliative care. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:356–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Hui D, Anderson L, Tang M, Park M, Liu D and Bruera E. Examination of referral criteria for outpatient palliative care among patients with advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28:295–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Hui D, Mori M, Watanabe SM, Caraceni A, Strasser F, Saarto T, Cherny N, Glare P, Kaasa S and Bruera E. Referral criteria for outpatient specialty palliative cancer care: an international consensus. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:e552–e559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.