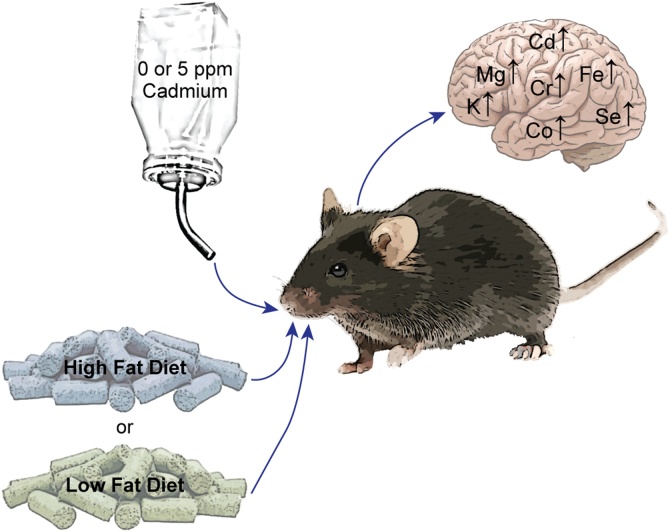

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Cadmium, Brain, Obesity, Trace elements, Metal homeostasis, Oxidative stress

Highlights

-

•

Whole-life exposure to cadmium leads to elevated metal levels in the brain that further increases in high-fat diet fed mice.

-

•

Female animals accumulate more cadmium in the brain than males, under all treatment conditions.

-

•

Cadmium exposure is associated with changes in the levels of several essential metals.

-

•

Cadmium and high fat diet increase levels of superoxide anion in the cortex, amygdala and hippocampus.

Abstract

Analyses of human cohort data support the roles of cadmium and obesity in the development of several neurocognitive disorders. To explore the effects of cadmium exposure in the brain, mice were subjected to whole life oral cadmium exposure. There were significant increases in cadmium levels with female animals accumulating more metal than males (p < 0.001). Both genders fed a high fat diet showed significant increases in cadmium levels compared to low fat diet fed mice (p < 0.001). Cadmium and high fat diet significantly affected the levels of several essential metals, including magnesium, potassium, chromium, iron, cobalt, copper, zinc and selenium. Additionally, these treatments resulted in increased superoxide levels within the cortex, amygdala and hippocampus. These findings support a model where cadmium and high fat diet affect the levels of redox-active, essential metal homeostasis. This phenomenon may contribute to the underlying mechanism(s) responsible for the development of neurocognitive disorders.

1. Introduction

Cadmium is a widespread human health concern [1,2]. The average dietary intake of this metal ranges from 8 to 25 μg per day, with a predicted half-life between 10–30 years [3,4]. Primary routes of non-occupational exposure include ingestion of cadmium containing foods and inhalation, mainly from cigarette smoke [4,5]. This metal is primarily stored in the kidney and liver. Analysis of human autopsy samples, however; show cadmium in the brain at levels between 0.003−0.12 μg/g [6].

The majority of toxicological research on cadmium has focused on its activity as a carcinogen and nephrotoxicant. Epidemiologic data and animal studies however, find associations between cadmium exposure, impaired neurodevelopment and neuronal function [[7], [8], [9]]. Occupationally-exposed adults show negative neurobehavioral traits and cognitive impairment [10,11]. Additionally, significant associations between maternal and infant cadmium levels and impaired neurodevelopment have been reported [[12], [13], [14], [15]]. Similarly, metallomic analysis of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) found that 8.5 % had higher hair cadmium levels, compared to the general population [9,16,17].

Studies using animal models suggest that cadmium-induced changes in blood-brain barrier permeability and neuronal damage may be the result of cadmium-mediated generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [[18], [19], [20], [21], [22]]. This damage is associated with negative impacts on memory and cognitive behavior [23,24].

Cadmium exposure is associated with increases in ROS. This metal however is not redox active in vivo. Thus alternate models have been suggested to explain ROS increases including depletion of glutathione [25,26]. Another alternative mechanism may be cadmium-induced disruption of trace element homeostasis [[27], [28], [29]].

Disruption of trace element homeostasis is also associated with obesity which now affects 17 % and 35 % of children and adults, respectively [30,31]. Epidemiological studies find a higher prevalence of obesity in ASD patients compared to control populations [32]. In addition, maternal obesity and/or gestational diabetes are ASD risk factors [33,34]. In animal models of ASD, a direct causative link between diet-induced obesity and worsening of ASD-like behavior has been observed [35].

To investigate the relationship among cadmium, obesity, essential trace metals and oxidative stress, changes in the levels of cadmium and essential metals in the brains of mice exposed to low-dose cadmium and high-fat diet (HFD) were quantified. Additionally, gender differences in the levels of these metals were examined.

2. Methods

2.1. Animals and exposures

Six week old male and female C57BL/6 J mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. Mice were housed in a pathogen-free AAALAC-accredited facility and all procedures were approved by the University of Louisville’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. One week after the animals arrived, diets were changed to AIN-76A purified diet (Envigo) to limit the confounding effects of metal contamination found in standard chow [36]. Food and deionized water were provided ad libitum.

Cadmium exposure for parental mice (F0) began at 10 weeks of age. Cadmium containing drinking water (0 or 5 ppm [final concentration]) was prepared from stock solutions of cadmium chloride (Alfa Aesar) in deionized water and stored at −80 °C. Based on a survey of the literature, 5 ppm cadmium is one of the lower concentrations of cadmium tested, which is approximately 1% of the cadmium LD50 [37]. At 12 weeks of age mice were placed into breeding triplets (1 male to 2 females) within each cadmium exposure group (Suppl. Fig. 1). After weaning, offspring (F1) were continuously exposed to the same concentration of cadmium as their parents until sacrifice. Additionally, offspring were fed either a low-fat (LF; 13 % fat) or high-fat (HF; 2% fat) diets. Offspring were sacrificed 24 weeks after weaning (Suppl. Fig. 1). Brains were harvested from each mouse. Portions of each organ were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 °C for future analyses.

2.2. Metal analysis

Brains were digested by incubating in 70 % nitric acid at 85 °C for 4 h. Samples were then cooled to room temperature, centrifuged to remove undigested debris and then diluted to 2% nitric acid (final concentration) with Milli-Q deionized water. Element quantification was performed using an X Series II quadrupole inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific). During sample injection, internal standards including Bi, In, 6Li, Sc, Tb and Y (Inorganic Ventures) were mixed with each sample for instrument calibration. Each sample was analyzed three times.

2.3. Dihydroethidium histological analysis

The presence of ROS in the hippocampus, cortex and amygdala were probed using dihydroethidium (DHE) (Sigma Chemical Co). Brains were post-fixed, cryoprotected sequentially in 15 %, 30 % and 40 % sucrose, and embedded in tissue freezing medium for cryosectioning. Thick (25 μm) sagittal sections were prepared using a cryostat (Leica, Germany), mounted onto charged slides and then stored at -20℃ until staining. To test for the presence of ROS, sections from five non-cadmium treated HFD animals and five cadmium-treated HFD animals were incubated with 5 μM DHE at 37 °C for 30 min in the dark, as previously described [38]. To confirm the presence of superoxide, additional sections were pre-incubated for one hour at room temperature with Polyethylene Glycol-Conjugated Superoxide Dismutase (500 units/mL, Sigma) followed by DHE staining. Fluorescence images of hippocampus, cortex and amygdala regions of each animal were obtained using a laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica).

2.4. Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics for offspring mice (F1) were summarized as mean ± SD stratified by sex (male vs female), diet (LF vs. HF) and cadmium concentration (0 vs. 5 ppm). Three-way ANOVA with two-way and three-way interactions were applied to examine whether sex, diet and cadmium exposure were significant for each metal in F1mice. Bonferroni adjusted p-values resulting from the ANOVAs were reported, where the Bonferroni adjusted p-values were calculated by the original p-values times the number of tests at seven (i.e., three main effects, three two-way interactions and one-three-way interaction). The main effect or interaction was significant if the corresponding adjusted p-value was less than 0.05. A significant cadmium exposure effect indicated that the metal was significantly different between the two cadmium exposure levels. Significant sex effect indicated that metal concentration was significantly different between male and female mice. Similarly, significant diet effect indicated that metal concentration was significantly different between HFD and LFD fed mice. Two-way interaction term indicated whether the difference of metal concentration in F1 mice between two levels of one factor was significantly different among the different levels of the other factor. Three-way interactions indicated that the effects of one factor differed significantly among the different combinations of the other two factors. A factor had significant effect on the metal concentration if the main effect and/or its interaction term were statistically significant at a Bonferroni-adjusted significance level 0.05. Post-hoc t-tests for the effect of one factor with the other two factors fixed at certain levels were carried out only if the effect of the factor was statistically significant, thus the family-wise type I error rate was controlled at 0.05 [39]. In particular, group comparisons due to cadmium exposure were further examined using post-hoc t-tests only if either the cadmium exposure or its interaction in the three-way ANOVA were significant at Bonferroni adjusted significance level 0.05. The effects due to diet or sex were examined in a similar manner. The statistical analyses were carried out using the statistics software R version 3.6.2 (https://www.r-project.org/).

3. Results

3.1. Cadmium accumulation in the brain

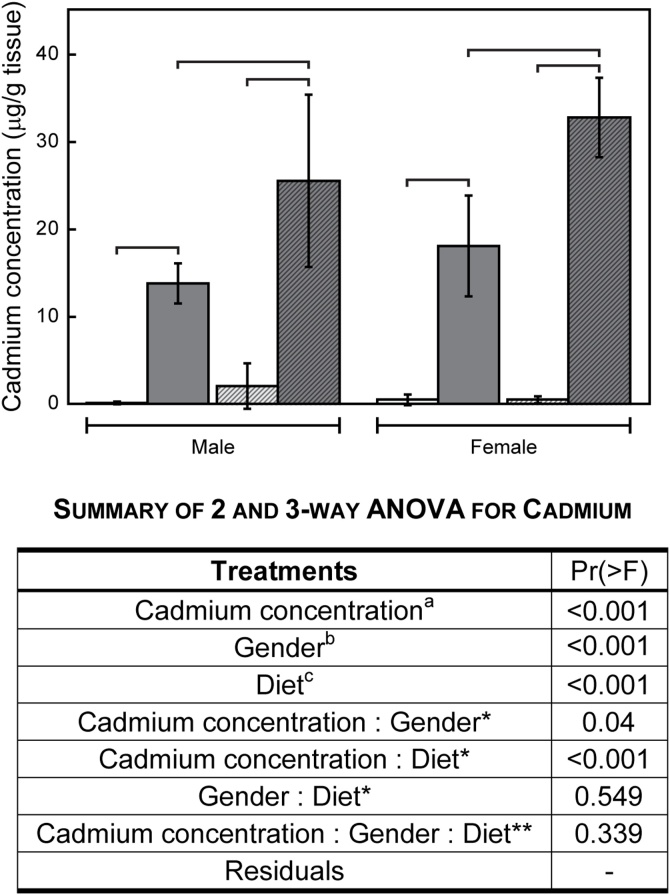

Concentrations of cadmium in brain were measured using ICP-MS. Exposure to 5 ppm cadmium resulted in significant increases in the metal under all experimental conditions (Fig. 1). For animals fed a LFD, exposure to 5 ppm cadmium increased brain cadmium from < 1 to 14−18 μg/g (Fig. 1). High fat diet did not affect the levels of cadmium in non-exposed animals. In cadmium-exposed animals, however; there were significantly higher levels of brain cadmium. Additionally, the cadmium concentration was almost double to that measured in LFD fed animals. Gender also significantly affected cadmium accumulation. Female mice had significantly more metal than correspondingly treated males. Two-way ANOVA for cadmium treatment and diet or gender indicated significant interactions (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Cadmium concentrations in mouse brain. Animals were exposed to 0 (light bars) or 5 ppm cadmium (dark bars) and fed either a LF (open bars) or HF (hatched bars) diet. Cadmium levels were measured by ICP-MS. Brackets indicate a significant difference (p < 0.05 < p) in metal concentration between treatment groups based on ANOVA analyses and post-hoc t-tests. In the summary of ANOVA results: a indicates whether cadmium concentration was significantly different between the two cadmium exposure levels; b indicates whether cadmium concentration was significantly different between male and female mice; c indicates whether cadmium concentration was significantly different between HFD and LFD; * two-way interaction term indicates whether the difference of cadmium concentration between two levels of one factor was significantly different among the different levels of the other factor and ** indicates three-way interactions.

3.2. Effect of cadmium exposure on essential metal levels in brain

ICP-MS measures concentration of metals with Z numbers between 9 (Be) and 208 (Pb). Additional analyses focused on the effects of cadmium, diet and gender on the following essential metals: 23Na, 24Mg, 39K, 44Ca, 55Mn, 52Cr, 57Fe, 59Co, 65Cu, 66Zn, 82Se, and 95Mo. In the absence of cadmium, LFD fed male mice had significantly higher levels of 24Mg, 39K and 57Fe in the brain than females (Table 1, Suppl. Tables 1 and 3). Similarly, female mice fed the HFD accumulated significantly more 24Mg, 39K, 52Cr, 57Fe, 59Co, 65Cu, 66Zn and 82Se than LFD fed mice in the absence of cadmium. Male animals did not demonstrate significant changes in essential metal levels in response to diet (Table 1, Suppl. Table 2). Cadmium significantly increased the levels of 24Mg, 39K, 52Cr, 57Fe, 59Co and 82Se (Table 1, Suppl. Table 1). Statistical analyses of the effects of cadmium, diet and gender on essential metal levels are presented in Suppl. Tables 1 – 3.

Table 1.

Essential Metal Concentration in Brain.

| Treatment Group |

Metal Concentration ± SD (μg/g) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Diet | Cd | 24Magnesium | 39Potassium | 52Chromium | 57Iron | 59Cobalt | 65Copper | 66Zinc | 82Selenium |

| Male | HFD | 0 ppm | 105,948 ± 31,677 | 2,549,352 ± 859,096 | 132 ± 39 | 11,908 ± 2,987 | 4.5 ± 1.02 | 2,847 ± 703 | 10,581 ± 2,637 | 94.1 ± 29.9 |

| 5 ppm | 112,383 ± 23,367 | 2,429,197 ± 797,925 | 155 ± 25 | 13,027 ± 2,438 | 4.6 ± 1.16 | 3,088 ± 518 | 12,975 ± 2,446 | 118.4 ± 11.1 | ||

| LFD | 0 ppm | 93,593 ± 8,072 | 2,115,489 ± 228,811 | 116 ± 18 | 10,870 ± 1,064 | 3.8 ± 0.99 | 2,738 ± 853 | 8,339 ± 2,326 | 85.5 ± 12.9 | |

| 5 ppm | 112,751 ± 14,836 | 2,564,415 ± 606,709 | 130 ± 10 | 11,618 ± 1,265 | 4.5 ± 0.8 | 2,641 ± 422 | 9,284 ± 2,206 | 91.8 ± 28.4 | ||

| Female | HFD | 0 ppm | 98,873 ± 5,914 | 2,186,313 ± 178,297 | 134 ± 23 | 11,530 ± 1,445 | 4.9 ± 0.39 | 3,180 ± 141 | 12,640 ± 1,916 | 102.2 ± 29.0 |

| 5 ppm | 104,338 ± 11,676 | 2,191,195 ± 352,318 | 139 ± 15 | 11,529 ± 1,574 | 5 ± 0.76 | 3,075 ± 508 | 10,780 ± 2,062 | 103 ± 19.5 | ||

| LFD | 0 ppm | 73,071 ± 13,364 | 1,514,813 ± 362,650 | 94 ± 24 | 8,776 ± 1,320 | 3.2 ± 0.84 | 2,056 ± 591 | 6,763 ± 2,448 | 68.9 ± 18.2 | |

| 5 ppm | 123,552 ± 20,127 | 2,836,092 ± 642,158 | 150.4 ± 24 | 12,462 ± 2,080 | 4.9 ± 0.81 | 2,857 ± 865 | 9,996 ± 2,546 | 109.3 ± 31.8 | ||

Elements listed in this table showed significant responses to cadmium exposure based on three-way ANOVA. Detailed statistical analyses and indications of significant differences based on 3-way ANOVA and t-tests can be found Suppl. Tables 1–3. Values for all of the measured essential metals can be found in (Suppl. Tables 2 and 3).

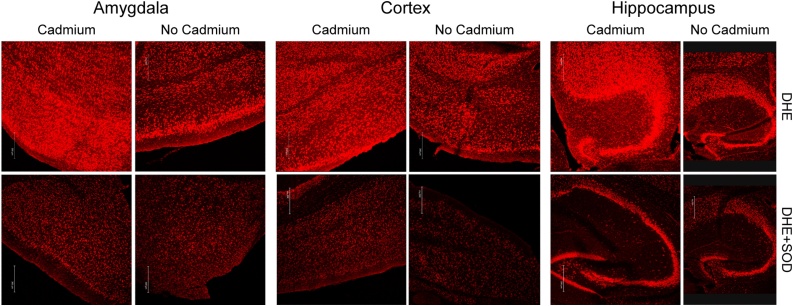

3.3. Cadmium and HFD-induced ROS in brain

The fluorescent probe DHE was used to determine the levels of superoxide in the brain of male and female mice, following 5 ppm cadmium treatment in HFD-fed animals. The relative DHE staining intensity was assessed in three brain regions relevant to ASD: cortex, hippocampus and amygdala. The DHE immunofluorescence in the three brain areas of Cd/HFD-treated mice was higher compared to their respective non-cadmium treated HFD animals (Fig. 2). Pre-incubation with superoxide dismutase reduced DHE fluorescence in treated animals to levels identical to those of non-treated mice, demonstrating the specificity of the superoxide staining (Fig. 2, lower panels). A significant difference between males and females was not observed, but this may be a consequence of a small sample size.

Fig. 2.

Cadmium increases superoxide in HFD-fed mice. TopPanels, Representative images of DHE stained brain tissue from male mice fed high fat diet showing increased superoxide in hippocampus (left), cortex (middle) and amygdala (right) brain regions associated with 5 ppm cadmium exposure. BottomPanels, brain tissues from the same animals shown in the toppanels were pre-incubated with superoxide dismutase prior to DHE staining.

4. Discussion

The ability of the transition metal cadmium to impact human health is well established. Analyses of human data from large cohort studies from US, Korea, China and Taiwan (NHANES, KNHANES, CHNS and NAHSIT) find significant associations between cadmium levels and other human diseases, including metabolic syndrome, type II diabetes, hypertension, hearing loss and a set of neurological abnormalities [[40], [41], [42]]. Neurological pathologies associated with cadmium exposure include cognitive impairment, defective neurodevelopment, and ASD. Although significant associations between cadmium levels and these pathologies have been established, there is a paucity of information on the mechanistic links between cadmium exposure and neurocognitive abnormalities.

To begin investigating the role of cadmium in the development of these diseases, the effects of chronic whole-life, low-dose exposure on the distribution of cadmium and essential metals were examined. A 24 wk. oral exposure to 5 ppm cadmium caused a significant increase brain levels compared to non-exposed animals. These levels however, were much lower than that present in the livers, kidneys and hearts of the same animals (Table 2).

Table 2.

Tissue cadmium concentrations.

| Treatment group |

Mean cadmium concentration (μg/g tissue) ± SD* |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Diet | Cadmium Concentration (ppm) | Brain | Heart | Kidney | Liver |

| Male | LF | 0 | 0.1 ± 0.14 | 2.1 ± 2.6 | 5 ± 6.99 | 2.2 ± 3.16 |

| 5.0 | 13.8 ± 2.29 | 95.9 ± 44.13 | 3,624 ± 490.46 | 1,393.3 ± 226.02 | ||

| HF | 0 | 2.1 ± 2.62 | 2.2 ± 2.26 | 5 ± 4.75 | 4.1 ± 4.53 | |

| 5.0 | 25.6 ± 9.84 | 152 ± 51.37 | 5,706.9 ± 1,139.59 | 2,010 ± 856.03 | ||

| Female | LF | 0 | 0.5 ± 0.62 | 3.9 ± 2.08 | 4.2 ± 6.63 | 3 ± 3.8 |

| 5.0 | 18.1 ± 5.75 | 105.6 ± 15.18 | 4,909.1 ± 848.01 | 2,356.7 ± 446.26 | ||

| HF | 0 | 0.5 ± 0.4 | 3.2 ± 5.82 | 3.9 ± 2.74 | 5.6 ± 7.19 | |

| 5.0 | 32.8 ± 4.55 | 153.5 ± 56.55 | 8,117.5 ± 2,624.51 | 3,006.4 ± 1,384.27 | ||

LF, low-fat diet; HF, high-fat diet.

Details on the isolation and characteristics of heart, kidney and liver used in cadmium measurements can be found in [43].

Female mice accumulated more cadmium than males, which was similar to that observed in other tissues [43]. Gender-specific differences in cadmium levels and several biological endpoints from blood, urine, liver and kidney have observed in several large human cohort studies [41,44,45]. Elevated cadmium levels are associated with lower intelligence and ASD in males [13,46]. In a study of ∼1,300 five-year old children, an association between low-level cadmium exposure and lower IQ scores was reported with a more pronounced response in girls [47].

Although gender differences have been observed, the mechanism(s) responsible for these differences have not been established. One potential mechanism may be a higher rate and accumulation of cadmium in women due to increased gastrointestinal absorption due to higher levels of the duodenal metal transporter (DMT1), which also has a high affinity for cadmium [[48], [49], [50], [51]].

Cadmium and obesity interact to exacerbate human pathologies including prediabetes, metabolic syndrome, hypertension and neuropathology’s [[52], [53], [54], [55]]. Therefore, the impact of high fat diet on cadmium levels in the brain was also examined. High fat diet fed mice accumulated approximately two-fold more metal than those fed a LFD. Additionally, HFD-fed female mice had the highest levels of cadmium in the brain (Fig. 1). Similar responses to HFD on cadmium accumulation were previously observed in hearts, kidneys and livers of the identical animals [43]. As with brain, female HFD-fed mice accumulated the highest level of metal in these tissues.

It has been hypothesized that environmental toxicant-induced elevation of ROS in the brain may contribute to cognitive dysfunction [56,57]. Both obesity and cadmium exposure are associated with increased levels of ROS and several human diseases [[58], [59], [60]]. Moderate to low level cadmium exposure induces lipid peroxidation in the brain and interferes with antioxidant defenses [21,57]. This damage may affect the integrity and permeability of brain endothelium leading to additional oxidative injury and neuronal death [21,61].

Increased levels of superoxide were detected in the hippocampus, cortex and amygdala of HFD-fed/cadmium-treated animals (Fig. 2). Cadmium itself is not redox active in vivo; however, cadmium exposure led to significant increases in several redox-active essential metals including chromium, iron, and cobalt. HFD-fed mice also showed significant increases in the levels of chromium, cobalt, and copper (Table 1, Suppl. Table 1). Thus, cadmium-induced oxidative damage in the brain may be the consequence of elevated levels of these redox active metals that can be enhanced by high fat diet. Increased redox active metals could be responsible for the cadmium-mediated oxidative damage, brain alterations, and neuronal dysfunction.

Whole life exposure to cadmium in combination with HFD significantly affected cadmium and essential metal levels in the brain (Fig. 3). In addition, gender differences in metal distribution were observed. The disruption of essential metal homeostasis by cadmium and/or obesity, as well as gender specific differences may contribute to the progression of neurodevelopmental disorders. These results can serve as the basis for future studies to elucidate molecular mechanisms of cadmium-induced neurotoxicity focusing on neurodevelopmental disorders in response to environmental exposures.

Fig. 3.

Summary results on the effects of cadmium and diet on essential metal homeostasis. Mice were exposed to cadmium and/or HFD as diagrammed. After 24 weeks brains were collected and then cadmium and essential metals measured by ICP-MS. Metals whose levels significantly changed under any condition are presented.

Author contributions

J.H.F. and G.N.B. designed the study. J.C.M., R.J. and E.G. performed the experiments including organ harvest and immunohistochemistry. M.K. and Q.X. performed statistical analyses of the data. All of the authors contributed to the preparation of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded in part by National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health (R01ES028102 and T35ES14559), Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (P20GM113226-6176).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Jianxiang (Jason) Xu for his excellent assistance in metal measurements by ICP-MS. Walter H. Watson and Tom Burke for their assistance during the mouse harvest.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxrep.2020.08.005.

Contributor Information

Gregory N. Barnes, Email: gregory.barnes@louisville.edu.

Jonathan H. Freedman, Email: jonathan.freedman@louisville.edu.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Faroon O., Ashizawa A., Wright S., Tucker P., Jenkins K., Ingerman L., Rudisill C. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (US); Atlanta (GA): 2012. Toxicological Profile for Cadmium. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.International Programme on Chemical Safety . 2015. Cadmium.http://www.who.int/ipcs/assessment/public_health/cadmium/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Järup L., Åkesson A. Current status of cadmium as an environmental health problem. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2009;238(3):201–208. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waalkes M.P., Coogan T.P., Barter R.A. Toxicological principles of metal carcinogenesis with special emphasis on cadmium. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 1992;22(3–4):175–201. doi: 10.3109/10408449209145323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olsson I.M., Bensryd I., Lundh T., Ottosson H., Skerfving S., Oskarsson A. Cadmium in blood and urine--impact of sex, age, dietary intake, iron status, and former smoking--association of renal effects. Environ. Health Perspect. 2002;110(12):1185–1190. doi: 10.1289/ehp.021101185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lech T., Sadlik J.K. Cadmium concentration in human autopsy tissues. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2017;179(2):172–177. doi: 10.1007/s12011-017-0959-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iqbal G., Zada W., Mannan A., Ahmed T. Elevated heavy metals levels in cognitively impaired patients from pakistan. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2018;60:100–109. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2018.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Y., Chen L., Gao Y., Zhang Y., Wang C., Zhou Y., Hu Y., Shi R., Tian Y. Effects of prenatal exposure to cadmium on neurodevelopment of infants in shandong, China. Environ. Pollut. 2016;211:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2015.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yasuda H., Yasuda Y., Tsutsui T. Estimation of autistic children by metallomics analysis. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:1199. doi: 10.1038/srep01199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hart R.P., Rose C.S., Hamer R.M. Neuropsychological effects of occupational exposure to cadmium. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 1989;11(6):933–943. doi: 10.1080/01688638908400946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Viaene M.K., Masschelein R., Leenders J., De Groof M., Swerts L.J., Roels H.A. Neurobehavioural effects of occupational exposure to cadmium: a cross sectional epidemiological study. Occup. Environ. Med. 2000;57(1):19–27. doi: 10.1136/oem.57.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ciesielski T., Weuve J., Bellinger D.C., Schwartz J., Lanphear B., Wright R.O. Cadmium exposure and neurodevelopmental outcomes in U.S. children. Environ. Health Perspect. 2012;120(5):758–763. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gustin K., Tofail F., Vahter M., Kippler M. Cadmium exposure and cognitive abilities and behavior at 10 years of age: a prospective cohort study. Environ. Int. 2018;113:259–268. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim Y., Ha E.H., Park H., Ha M., Kim Y., Hong Y.C., Kim E.J., Kim B.N. Prenatal lead and cadmium co-exposure and infant neurodevelopment at 6 months of age: the Mothers and Children’s Environmental Health (MOCEH) study. Neurotoxicology. 2013;35:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodriguez-Barranco M., Lacasana M., Aguilar-Garduno C., Alguacil J., Gil F., Gonzalez-Alzaga B., Rojas-Garcia A. Association of arsenic, cadmium and manganese exposure with neurodevelopment and behavioural disorders in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2013;454-455:562–577. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He M.J., Wei S.Q., Sun Y.X., Yang T., Li Q., Wang D.X. Levels of five metals in male hair from urban and rural areas of chongqing, china. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2016;23(21):22163–22171. doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-7448-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shah F., Kazi T.G., Afridi H.I., Kazi N., Baig J.A., Shah A.Q., Khan S., Kolachi N.F., Wadhwa S.K. Evaluation of status of trace and toxic metals in biological samples (scalp hair, blood, and urine) of normal and anemic children of two age groups. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2011;141(1–3):131–149. doi: 10.1007/s12011-010-8736-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen S., Ren Q., Zhang J., Ye Y., Zhang Z., Xu Y., Guo M., Ji H., Xu C., Gu C., Gao W., Huang S., Chen L. N-acetyl-l-cysteine protects against cadmium-induced neuronal apoptosis by inhibiting ros-dependent activation of akt/mtor pathway in mouse brain. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2014;40(6):759–777. doi: 10.1111/nan.12103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chow E.S., Hui M.N., Lin C.C., Cheng S.H. Cadmium inhibits neurogenesis in zebrafish embryonic brain development. Aquat. Toxicol. 2008;87(3):157–169. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2008.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lopez E., Arce C., Oset-Gasque M.J., Canadas S., Gonzalez M.P. Cadmium induces reactive oxygen species generation and lipid peroxidation in cortical neurons in culture. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2006;40(6):940–951. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.10.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shukla A., Shukla G.S., Srimal R.C. Cadmium-induced alterations in blood-brain barrier permeability and its possible correlation with decreased microvessel antioxidant potential in rat. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 1996;15(5):400–405. doi: 10.1177/096032719601500507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang B., Du Y. Cadmium and its neurotoxic effects. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/898034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halder S., Kar R., Chandra N., Nimesh A., Mehta A.K., Bhattacharya S.K., Mediratta P.K., Banerjee B.D. Alteration in cognitive behaviour, brain antioxidant enzyme activity and their gene expression in F1 generation mice, following cd exposure during the late gestation period: modulation by quercetin. Metab. Brain Dis. 2018;33(6):1935–1943. doi: 10.1007/s11011-018-0299-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang H., Zhang L., Abel G.M., Storm D.R., Xia Z. Cadmium exposure impairs cognition and olfactory memory in male C57bl/6 mice. Toxicol. Sci. 2018;161(1):87–102. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfx202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shagirtha K., Bashir N., MiltonPrabu S. Neuroprotective efficacy of hesperetin against cadmium induced oxidative stress in the brain of rats. Toxicol. Ind. Health. 2017;33(5):454–468. doi: 10.1177/0748233716665301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shukla G.S., Srivastava R.S., Chandra S.V. Prevention of cadmium-induced effects on regional glutathione status of rat brain by vitamin e. J. Appl. Toxicol. 1988;8(5):355–359. doi: 10.1002/jat.2550080504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arnaud J., de Lorgeril M., Akbaraly T., Salen P., Arnout J., Cappuccio F.P., van Dongen M.C., Donati M.B., Krogh V., Siani A., Iacoviello L. Gender differences in copper, zinc and selenium status in diabetic-free metabolic syndrome european population - the immidiet study. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2012;22(6):517–524. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Azab S.F., Saleh S.H., Elsaeed W.F., Elshafie M.A., Sherief L.M., Esh A.M. Serum trace elements in obese egyptian children: a case-control study. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2014;40:20. doi: 10.1186/1824-7288-40-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miao X., Sun W., Fu Y., Miao L., Cai L. Zinc homeostasis in the metabolic syndrome and diabetes. Front. Med. 2013;7(1):31–52. doi: 10.1007/s11684-013-0251-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marreiro D.N., Fisberg M., Cozzolino S.M. Zinc nutritional status and its relationships with hyperinsulinemia in obese children and adolescents. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2004;100(2):137–149. doi: 10.1385/bter:100:2:137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ogden C.L., Carroll M.D., Kit B.K., Flegal K.M. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the united states, 2011-2012. JAMA. 2014;311(8):806–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Curtin C., Anderson S.E., Must A., Bandini L. The prevalence of obesity in children with autism: a secondary data analysis using nationally representative data from the national survey of children’s health. BMC Pediatr. 2010;10:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-10-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li M., Fallin M.D., Riley A., Landa R., Walker S.O., Silverstein M., Caruso D., Pearson C., Kiang S., Dahm J.L., Hong X., Wang G., Wang M.C., Zuckerman B., Wang X. The association of maternal obesity and diabetes with autism and other developmental disabilities. Pediatrics. 2016;137(2) doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sullivan E.L., Nousen E.K., Chamlou K.A. Maternal high fat diet consumption during the perinatal period programs offspring behavior. Physiol. Behav. 2014;123:236–242. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zilkha N., Kuperman Y., Kimchi T. High-fat diet exacerbates cognitive rigidity and social deficiency in the btbr mouse model of autism. Neuroscience. 2017;345:142–154. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.01.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kozul C.D., Nomikos A.P., Hampton T.H., Warnke L.A., Gosse J.A., Davey J.C., Thorpe J.E., Jackson B.P., Ihnat M.A., Hamilton J.W. Laboratory diet profoundly alters gene expression and confounds genomic analysis in mouse liver and lung. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2008;173(2):129–140. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry . Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry; Atlanta, GA: 2012. Toxicological Profile for Cadmium (update) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li Z., Jagadapillai R., Gozal E., Barnes G. Deletion of semaphorin 3F in interneurons is associated with decreased gabaergic neurons, autism-like behavior, and increased oxidative stress cascades. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019;56(8):5520–5538. doi: 10.1007/s12035-018-1450-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller R.G. 2d ed. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1981. Simultaneous Statistical Inference. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kang G.H., Uhm J.Y., Choi Y.G., Kang E.K., Kim S.Y., Choo W.O., Chang S.S. Environmental exposure of heavy metal (lead and cadmium) and hearing loss: data from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANS 2010-2013) Ann. Occup. Environ. Med. 2018;30:22. doi: 10.1186/s40557-018-0237-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liao K.W., Pan W.H., Liou S.H., Sun C.W., Huang P.C., Wang S.L. Levels and temporal variations of urinary lead, cadmium, cobalt, and copper exposure in the general population of Taiwan. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2019;26(6):6048–6064. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-3911-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu P., Zhang Y., Su J., Bai Z., Li T., Wu Y. Maximum cadmium limits establishment strategy based on the dietary exposure estimation: an example from Chinese populations and subgroups. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2018;25(19):18762–18771. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-1783-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Young J.L., Yan X., Xu J., Yin X., Zhang X., Arteel G.E., Barnes G.N., States J.C., Watson W.H., Kong M., Cai L., Freedman J.H. Cadmium and high-fat diet disrupt renal, cardiac and hepatic essential metals. Sci. Rep. 2019;9(1):14675. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-50771-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nishijo M., Satarug S., Honda R., Tsuritani I., Aoshima K. The gender differences in health effects of environmental cadmium exposure and potential mechanisms. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2004;255(1–2):87–92. doi: 10.1023/b:mcbi.0000007264.37170.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vahter M., Berglund M., Akesson A., Liden C. Metals and women’s health. Environ. Res. 2002;88(3):145–155. doi: 10.1006/enrs.2002.4338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roberts A.L., Lyall K., Hart J.E., Laden F., Just A.C., Bobb J.F., Koenen K.C., Ascherio A., Weisskopf M.G. Perinatal air pollutant exposures and autism spectrum disorder in the Children of Nurses’ Health Study II participants. Environ. Health Perspect. 2013;121(8):978–984. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1206187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kippler M., Tofail F., Hamadani J.D., Gardner R.M., Grantham-McGregor S.M., Bottai M., Vahter M. Early-life cadmium exposure and child development in 5-year-old girls and boys: a cohort study in rural Bangladesh. Environ. Health Perspect. 2012;120(10):1462–1468. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Akesson A., Berglund M., Schutz A., Bjellerup P., Bremme K., Vahter M. Cadmium exposure in pregnancy and lactation in relation to iron status. Am. J. Public Health. 2002;92(2):284–287. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.2.284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Berglund M., Lindberg A.L., Rahman M., Yunus M., Grander M., Lonnerdal B., Vahter M. Gender and age differences in mixed metal exposure and urinary excretion. Environ. Res. 2011;111(8):1271–1279. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gunshin H., Mackenzie B., Berger U.V., Gunshin Y., Romero M.F., Boron W.F., Nussberger S., Gollan J.L., Hediger M.A. Cloning and characterization of a mammalian proton-coupled metal-ion transporter. Nature. 1997;388(6641):482–488. doi: 10.1038/41343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vahter M., Akesson A., Liden C., Ceccatelli S., Berglund M. Gender differences in the disposition and toxicity of metals. Environ. Res. 2007;104(1):85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Iqbal G., Ahmed T. Co-exposure of metals and high fat diet causes aging like neuropathological changes in non-aged mice brain. Brain Res. Bull. 2019;147:148–158. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2019.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jiang F., Zhi X., Xu M., Li B., Zhang Z. Gender-specific differences of interaction between cadmium exposure and obesity on prediabetes in the NHANS 2007-2012 population. Endocrine. 2018;61(2):258–266. doi: 10.1007/s12020-018-1623-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Noor N., Zong G., Seely E.W., Weisskopf M., James-Todd T. Urinary cadmium concentrations and metabolic syndrome in u.S. Adults: the national health and nutrition examination survey 2001-2014. Environ. Int. 2018;121(Pt 1):349–356. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang Q., Wei S. Cadmium affects blood pressure and negatively interacts with obesity: findings from NHANES 1999-2014. Sci. Total Environ. 2018;643:270–276. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.06.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Branca J.J.V., Morucci G., Pacini A. Cadmium-induced neurotoxicity: still much ado. Neural Regen. Res. 2018;13(11):1879–1882. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.239434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kumar R., Agarwal A.K., Seth P.K. Oxidative stress-mediated neurotoxicity of cadmium. Toxicol. Lett. 1996;89(1):65–69. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(96)03780-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marseglia L., Manti S., D’Angelo G., Nicotera A., Parisi E., Di Rosa G., Gitto E., Arrigo T. Oxidative stress in obesity: a critical component in human diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014;16(1):378–400. doi: 10.3390/ijms16010378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nemmiche S. Oxidative signaling response to cadmium exposure. Toxicol. Sci. 2017;156(1):4–10. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfw222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tan B.L., Norhaizan M.E., Liew W.P. Nutrients and oxidative stress: Friend or foe? Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018;2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/9719584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mendez-Armenta M., Rios C. Cadmium neurotoxicity. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2007;23(3):350–358. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.