Abstract

Introduction:

Workplace stress and unemployment are each associated with disturbances in sleep. However, a substantial gap exists in what we know about the type of workplace stress preceding job loss and the lasting effect workplace stressors may have on long-term health outcomes. We hypothesized that a specific type of workplace stress, hindrance stress, would be a stronger predictor of current insomnia disorder, compared to challenge stress.

Methods:

Cross-sectional data were analyzed from 191 recently unemployed individuals participating in the ongoing Assessing Daily Patterns through occupational Transitions (ADAPT) study. Participants were administered the Cavanaugh et al. (J Appl Psychol. 85(1):65, 2000) self-reported work stress scale regarding their previous job and the Duke Sleep Interview (DSI-SD), a semi-structured interview assessing ICSD-3 insomnia disorder (chronic and acute).

Results:

Results from logistic regression analyses indicated that hindrance work stress was associated with an increased likelihood of current overall, chronic, and acute insomnia disorder, when controlling for challenge stress and significant demographic factors. Challenge stress was associated with an increased likelihood of chronic insomnia disorder when controlling for hindrance stress and covariates. The association between challenge stress and acute insomnia differed as a function of sex.

Conclusions:

Hindrance work stressors were associated with increased odds of current insomnia disorder, even after employment ended. Across each of the tested models, hindrance stress had stronger effects on insomnia than challenge stress. These findings support and extend both the challenge-hindrance framework of work-related stress and the 3 P model of insomnia.

Keywords: insomnia, occupational stress, unemployment, challenge hindrance

Introduction

Sleep is a barometer of mental and physical health [1, 2] and is influenced by events occurring in our personal, professional, and social lives. Stressful life events are theorized to precipitate insomnia disorder [3]. Unfortunately, few studies have examined the trajectory of sleep after stressful events. Involuntary job loss is a highly stressful event that was of particular concern to United States (U.S.) citizens in 2007–2010, when approximately one in six Americans lost their job as part of the Great Recession [4]. Involuntary job loss has been associated with the development of poor mental health outcomes [5], but very little is known about sleep specifically. However, there is a well-established relationship between unemployment and sleep complaints. Unemployed individuals have been found to have 1.5 times greater odds of being diagnosed with insomnia, characterized by difficulties initiating and maintaining sleep, than individuals who are not unemployed [6, 7].

Unemployed individuals often experience sleep loss and disruption due to stressors from income and financial disparities resulting from their unemployment [8, 9]. However, workplace stressors prior to job loss may also contribute to later sleep problems. One study examining sleep prospectively in relation to employment status found that downward career trajectories were associated with a shortened sleep duration five years later [10]. For many individuals, involuntary job loss is preceded by an intense clustering of job-related stressors, including conflictual exchanges, role conflicts, situational constraints, and job insecurity.

In the occupational health psychology literature, the types of job-related stressors preceding job loss are often classified as hindrance stressors, one type of stressor within the Challenge-Hindrance Framework [11]. Hindrance stressors are demands or situations that create unwanted burden, such as role ambiguity, interruptions, and conflicts around organizational politics [12], and tend to be associated with poor job satisfaction and performance. Hindrance stress is also associated with poor organizational commitment and increased turnover [13]. Conversely, challenge stressors are work-related demands or situations that have the potential for gain, such as time pressure and high workload [12]. Employees often perceive challenge stressors in a positive light, providing the opportunity for growth and professional achievement [12]; challenge stressors have a negative relationship with turnover intentions and turnover [13].

Emerging research suggests that hindrance stressors are more likely to be associated with negative sleep health in employees as compared to challenge stressors. Using survey data from the longitudinal observational Midlife Development in the United States Study (MIDUS II study, 2004–2006), researchers found that hindrance stressors were prospectively associated with shorter sleep duration, worse sleep quality, and more sleepiness [14]. Other studies examining job stress more broadly also found a negative effect of hindrance-relevant stressors on sleep. For instance, the presence of intragroup conflict and low employment opportunities is associated with an increased prevalence of insomnia [15]. Stressors, such as social exclusion [16], role conflict and repetitive work, have also been associated with sleep disruptions [17]. In contrast, the relationship between challenge stressors (e.g., time pressure) and sleep disruption is mixed [14, 17].

Most studies examining job stress and sleep have classified job stress more broadly and often from alternative theoretical frameworks, such as the demand-control [18] and effort-reward imbalance [19] models of work stress. Within these models, sleep disturbances are thought to be a product of job strain or work-home spillover resulting from high work demands and low resources. While these models have contributed much to our understanding of the negative impact of job stress on sleep health, no studies to our knowledge have examined challenge-hindrance stressors and insomnia disorder specifically. Utilizing cross-sectional data from the Assessing Daily Activity Patterns through occupational Transition (ADAPT) study [20], we hypothesized that higher levels of hindrance stress from an individual’s most recent job would be associated with an increased likelihood of current insomnia disorder, above and beyond the effect of challenge-related work stressors. Findings from this study will bridge a critical gap between the fields of occupational health and unemployment by examining past work stress and sleep in a unique cohort of individuals who have recently, involuntarily transitioned from full-time work to unemployment.

Methods

This project utilizes screening and baseline data gathered from the ADAPT study, an ongoing, longitudinal observational study assessing the relationship between sleep and weight gain among individuals who have lost their jobs within the last 90 days. The study protocol and methods have been described previously [20]. The study was approved by the University of Arizona Human Subjects Protection Program and procedures have been performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Study sample

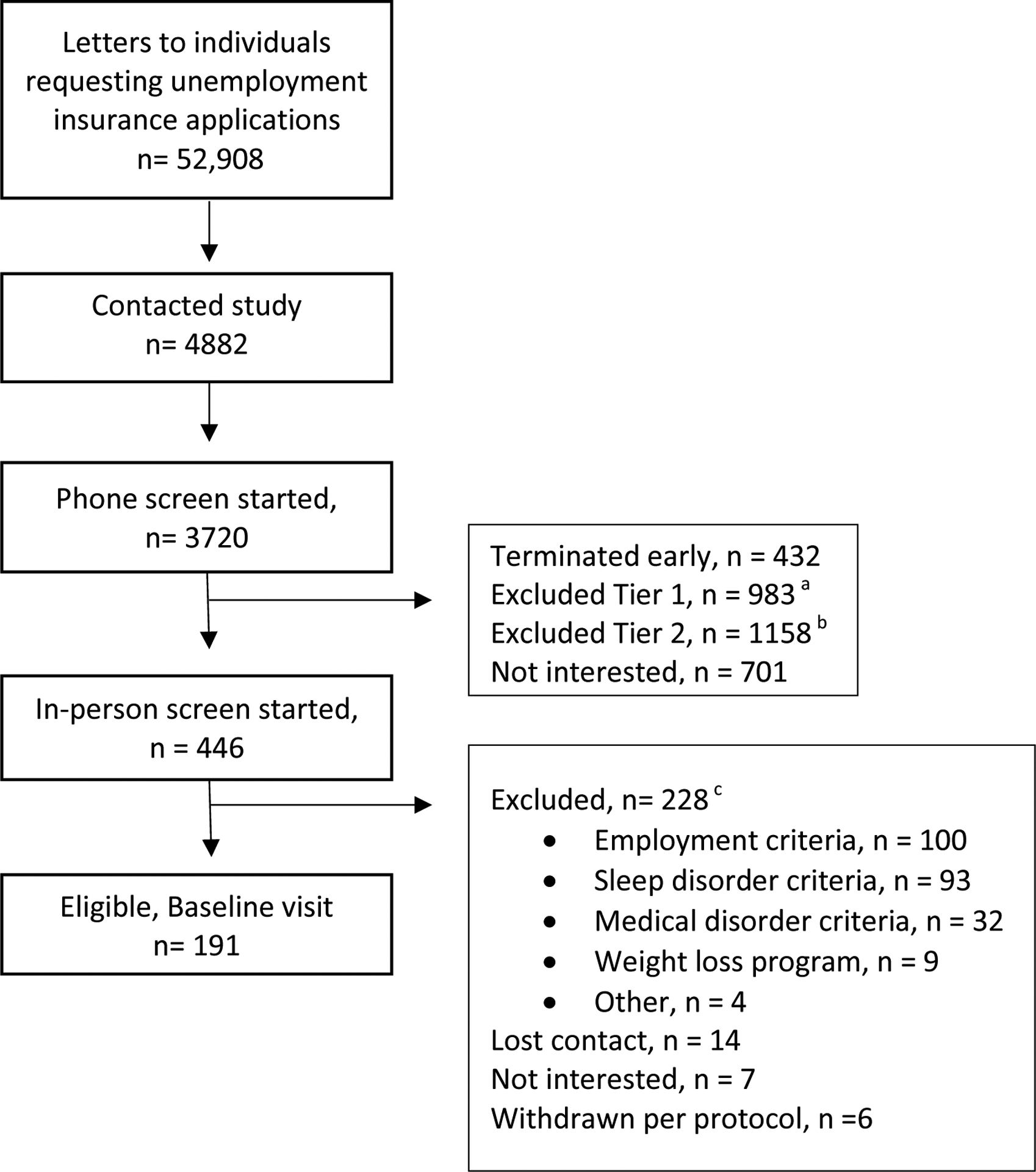

All participants meeting inclusion criteria for the parent study [20] were included in the current analysis. Consistent with the parent study, all participants were between the ages of 25–60 years. Participants were required to be unemployed (work ≤ 5h per week) and to have been laid off or terminated from primary, full-time employment (≥ 30h per week) within the last 90 days. Exclusion criteria included: medical sleep disorders like sleep apnea or sleep-related movement disorders; major current medical or psychiatric disorders that would interfere with study participation, such as cancer, substance/alcohol abuse disorders, and severe mental illness occurring at the time of interview. See Figure 1 for the participant recruitment diagram.

Figure 1,

Study Recruitment

aTier 1 exclusion criteria include: > 90 days since job loss; employed < 6 months at previous job; quit previous job. bTier 2 exclusion criteria include: not between ages of 25–60; current part-time or full-time work > 5 hours per week; previous job was seasonal or < 30 hours per week; layoff is temporary; retirement plans in the next 2 years; current job offer of > 5h per week; current weight loss medications or program or past weight loss surgery; sleep apnea or restless legs syndrome diagnoses; enrolled in cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia; uncontrolled medical condition; schizophrenia or bipolar disorder diagnosis; recent past psychiatric hospitalization or suicidality; current substance or alcohol abuse disorders; pregnant or < 3 months postpartum; recent felony charge. cParticipants may meet multiple criteria for exclusion.

Procedure

Participants were recruited via study flyers included in the Arizona Department of Economic Security Unemployment Insurance (UI) intake packets. The study flyer was distributed to all individuals in Tucson, Arizona and neighboring metropolitan areas who requested an unemployment insurance application packet between Oct 2015-Dec 2018. Interested individuals contacted study staff and participated in a phone screen grossly assessing inclusion and exclusion criteria. At the end of the phone screen, eligible individuals were then scheduled for an in-person screening visit to confirm eligibility criteria and administer ambulatory home testing for sleep apnea. At the screening visit, all individuals participated in informed consent procedures. Participants provided demographic information, confirmed employment status, and provided information about employment history. They completed the Duke Structured Interview for Sleep Disorders (DSI-SD) and the Cavanaugh et al. (2000) self-reported work stress scale [21]. At the end of the visit, participants were given the ApneaLink Plus™ (ResMed) with instructions to wear the device in their home overnight.

Measures

Control variables.

Participants completed a demographic form providing information on biological sex, age, race, ethnicity, and education history. All categorical variables were collapsed into dichotomous categories as follows: education (1 = bachelor’s degree or above; 0 = less than bachelor’s degree), race (0 = white, 1 = other), ethnicity (0 = Non-Hispanic/Latino; 1 = Hispanic/Latino), and sex (0 = female, 1 = male). In addition, individuals provided the date of job loss and date of job hire to allow for the calculation of the days since job loss and years employed at previous job.

Exclusion criteria.

Detailed information about exclusion criteria and assessment are outlined in the parent study protocol paper [20]. Briefly, participants received a past employment interview, a medical history interview, and the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI; [22]) to assess for employment, medical, and severe mental illness exclusion criteria. Sleep disorders were assessed via the Duke Structured Sleep Interview for Sleep Disorders (see description below) and the ApneaLink Plus,™ an ambulatory in-home screening device for sleep disordered breathing. The ApneaLink Plus™ was scored by a registered polysomnographic technologist and interpreted by a physician board-certified in sleep medicine.

Cavanaugh et al. (2000; [21]) self-reported work stress scale.

This self-report measure has high levels of reliability and validity, and includes six challenge stressor questions and five hindrance stressor questions related to the participant’s most recent job [21]. Challenge stressor items queried about past workload, time spent at work, job demands, time pressure, and responsibility (Cronbach’s α = .90 for current sample). Hindrance stressor items queried about past organizational politics, role ambiguity, obstacles associated with accomplishing tasks, job insecurity, and promotion potential (Cronbach’s α = .78 for current sample). Respondents provided answers via a five-point Likert scale, in which 5 indicated “produced a great deal of stress” and 1 indicated “produced no stress” [21].

Duke Structured Sleep Interview for Sleep Disorders (DSI-SD) [23].

The DSI-SD is a structured clinical interview with good preliminary validation data for the clinical assessment of Insomnia Disorder based on both the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) and International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD) sleep disorder nosologies [24]. The administered version included ICSD-2 nosology with additional questions about insomnia timeframe and frequency of symptoms to allow for an assessment of both adjustment sleep disorder (acute insomnia) and chronic insomnia disorder based on International Classification of Sleep Disorders, third edition (ICSD-3) [24]. All DSI-SD raters completed a structured training program incorporating video review and participated in reliability rating requiring a kappa ≥ .75 for insomnia diagnosis as compared to a licensed clinician who possessed a masters-level degree or above. Current Acute or Chronic Insomnia Disorder was scored as a dichotomous variable (1 = present; 0 = absent).

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics quantified sample characteristics, including demographics and insomnia disorder prevalence. Continuous predictor variables were standardized to a standard deviation of one to facilitate interpretation of results. Covariates were selected via the seven-step purposeful selection technique [25]. This iterative technique involves conducting a univariate and multivariate logistic regression models with various decision points about model-building based on statistical (e.g., partial likelihood test ratio), arithmetic, and theoretical factors. Hindrance and challenge stress were examined along with the following covariates informed by both the insomnia and work stress literature base: education (undergraduate, bachelor’s degree or higher) [26, 27], race [27, 28], ethnicity (Hispanic vs non-Hispanic) [27], age [27, 29], sex [26, 27], days since job loss [30], and years employed at previous job [29]. Covariates and predictors were assessed for multicollinearity using linear regression. Items with variance inflation factors (VIF) below 2.50 were maintained [31] for the final logistic regression model predicting the probability of any Insomnia Disorder.

For follow-up analyses, the same set of analytical procedures were repeated separately examining chronic (≥ 3 months) and acute insomnia disorder (< 3 months) [24]. All data were analyzed using the IBM SPSS Version 26.0 statistical program.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Data were analyzed from the full, parent cross-sectional sample of 191 participants who involuntarily lost their jobs within the last 90 days and were eligible for the parent study [20]. See Table 1 for participant characteristics. Participants in this U.S. Southwestern study were overrepresented on White race and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, as compared to the national averages of individuals who have lost their permanent jobs [32]. Participants represented previous jobs in all of the standard occupational code classifications [33], except military-specific occupations. The majority of participants were previously employed in management (n = 34, 17.8%), office and administrative support (n = 26, 13.6%), and business and financial operations (n = 17, 8.9%).

Table 1,

Participant Characteristics of original sample (n = 191).

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 114 | 59.7 |

| Male | 77 | 40.3 |

| Race | ||

| White | 134 | 70.2 |

| Not White | ||

| American Indian, Alaska Native | 7 | 3.7 |

| Asian | 1 | 0.5 |

| Black, African American | 12 | 6.3 |

| Pacific Islander | 1 | 0.5 |

| More than one race | 15 | 7.9 |

| Other | 13 | 6.8 |

| Unknown or declined to answer | 8 | 4.2 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 61 | 31.9 |

| Not Hispanic | 130 | 68.1 |

| Education | ||

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 71 | 37.2 |

| Less than bachelor’s degree | 120 | 62.8 |

| Chronic Insomnia Disorder | 45 | 23.6 |

| Acute Insomnia Disorder | 59 | 30.9 |

| Any Insomnia Disorder | 104 | 54.5 |

| M | SD | |

| Age, years | 41.07 | 10.29 |

| Years employed at previous job | 3.87 | 4.75 |

| Days since job loss | 41.79 | 19.61 |

| Hindrance stress score | 8.38 | 5.19 |

| Challenge stress score | 10.39 | 6.28 |

Note. Hindrance stress score, n = 187. Challenge stress score, n = 188.

The percentage of missing values across the 12 variables varied between 0 and 33%. In total, 13 out of 2,292 records (.57%) were incomplete. All missing data were scored as ‘prefer not to answer.’ We used multiple imputation to create and analyze 3 multiply imputed datasets. Incomplete variables were imputed under fully conditional specification, using the default settings of the IBM SPSS 26.0 package. The parameters of substantive interest were estimated in each imputed dataset separately and pooled for the main analyses.

Work Stressors Predicting Insomnia Disorder

Only ethnicity and education were retained as significant covariates in the purposeful selection process with hindrance stress; challenge-related work stress did not increase the odds of an insomnia disorder classification. Neither ethnicity nor education significantly interacted with hindrance stress in predicting increased likelihood of insomnia disorder classification. The variance inflation factors for the final model using the original dataset including ethnicity, education, and hindrance stress were acceptable; the largest VIF was 1.09 for education. Holding educational status and ethnicity constant, logistic regression results indicated that past hindrance-related work stress increased the odds of being diagnosed with insomnia disorder (see Table 2).

Table 2,

Logistic Regression Analysis Predicting Current Insomnia Disorder in Individuals with Recent Job Loss (n = 191)

| Predictor | β | SE β | p | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hindrance stress, z score | 0.82 | .18 | .00 | 2.26 | 1.58, 3.22 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 1.33 | .38 | .00 | 3.79 | 1.80, 7.98 |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | −0.70 | .35 | .05 | 0.50 | 0.25, 0.98 |

| Constant | 0.07 | .24 | .77 | NA | NA |

| Test | X2 | df | p | ||

| Overall model evaluation | |||||

| Likelihood ratio test | 35.59 | 3 | .00 | ||

| Goodness-of-fit test | |||||

| Hosmer & Lemeshow | 9.59 | 8 | .30 |

Note. NA = not applicable. All tests of model fit are based on the original data (n = 187).

Although challenge stress was removed on Step 1 of the purposeful selection process, we conducted an additional analysis including challenge stress to formally assess the proposed hypothesis that hindrance stress is associated with an increased likelihood of current insomnia above and beyond the effects of challenge stress. Consistent with the purposeful selection results, challenge stress did not significantly increase the likelihood of insomnia classification; hindrance stress remained a significant predictor with challenge stress in the model, OR = 2.45, 95% CI [1.52, 3.70].

The same purposeful selection process was employed for follow-up analyses separately examining current chronic and acute insomnia disorder. The final model for current chronic insomnia disorder is presented in Table 3. Education was assessed as an important covariate for inclusion, and both challenge and hindrance stress from past employment were associated with increased odds of current chronic insomnia disorder. Education did not significantly interact with hindrance or challenge stress in predicting the likelihood of chronic insomnia disorder classification. The variance inflation factors for the final model using the original dataset were acceptable (hindrance stress VIF = 1.42; challenge stress VIF = 1.43; education VIF = 1.05). No substantive differences emerged from exploratory models separately examining challenge and hindrance stress, controlling for education.

Table 3,

Logistic Regression Analysis Predicting Current Chronic Insomnia Disorder in Individuals with Recent Job Loss (n = 191)

| Predictor | β | SE β | p | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hindrance stress, z score | 0.47 | .22 | .03 | 1.60 | 1.05, 2.45 |

| Challenge stress, z score | 0.39 | .21 | .07 | 1.47 | 0.97, 2.24 |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | −1.47 | .44 | .00 | 0.23 | 0.20, 0.54 |

| Constant | −0.83 | .21 | .00 | NA | NA |

| Test | X2 | df | p | ||

| Overall model evaluation | |||||

| Likelihood ratio test | 25.74 | 3 | .00 | ||

| Goodness-of-fit test | |||||

| Hosmer & Lemeshow | 12.15 | 8 | .15 |

Note. NA = not applicable. All tests of model fit are based on the original data (n = 185).

The final model for current acute insomnia disorder is presented in Table 4. Ethnicity and sex were included as covariates; female sex and Hispanic ethnicity were each associated with increased likelihood of acute insomnia. In addition, both challenge and hindrance stress from past employment were associated with current acute insomnia disorder. Hindrance stress increased the likelihood of acute insomnia classification while challenge stress decreased the likelihood of classification. An assessment of two-way interactions between covariates and stressor variables demonstrated that this challenge-related resiliency effect seemed to primarily occur in males (see Figure 2). No other interactions were significant. The variance inflation factors for the final model, without the interaction, were acceptable (hindrance stress VIF = 1.44; challenge stress VIF = 1.42; ethnicity VIF = 1.02; sex VIF = 1.01). No substantive differences emerged when separately examining challenge and hindrance stress, controlling for ethnicity and sex.

Table 4,

Logistic Regression Analysis Predicting Current Acute Insomnia Disorder in Individuals with Recent Job Loss (n = 191)

| Predictor | β | SE β | p | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hindrance stress, z score | 0.68 | .22 | .00 | 1.97 | 1.29, 3.01 |

| Challenge stress, z score × Sex | 0.83 | .41 | .05 | 2.28 | 1.02, 5.11 |

| Challenge stress, z score | −1.19 | .40 | .00 | 0.30 | 0.14, 0.66 |

| Female sex | 0.92 | 0.39 | .02 | 2.51 | 1.18, 5.33 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 0.95 | 0.35 | .01 | 2.59 | 1.29, 5.19 |

| Constant | −1.83 | .36 | .00 | NA | NA |

| Test | X2 | df | p | ||

| Overall model evaluation | |||||

| Likelihood ratio test | 25.07 | 5 | .00 | ||

| Goodness-of-fit test | |||||

| Hosmer & Lemeshow | 14.31 | 8 | .08 |

Note. NA = not applicable. All tests of model fit are based on the original data (n = 185).

Figure 2,

Mean Challenge Stressor Score by Sex and Current Acute Insomnia Disorder Status

Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval.

Discussion

The current study contributes to both the occupational health and unemployment literature by demonstrating that hindrance stressors associated with a previous job increase the likelihood of chronic and acute insomnia disorder. Hindrance stressors increased the odds of insomnia above and beyond challenge stressors and other demographics associated with insomnia, including Hispanic ethnicity and lower education level. Findings suggest that hindrance stressors experienced at a previous job confer unique, detrimental health risks for individuals even after their position has been terminated.

Results from this study support and extend prior research and theory in a number of ways. While previous work has demonstrated that hindrance stress is associated with burnout [34], anger [35], and loss of vitality [36], findings from this study demonstrate that hindrance stress is associated with insomnia disorder, a condition associated with significant health burden [37] and negative quality of life [38]. Insomnia has been associated with numerous physical and mental health conditions [39–41] and has been identified as an important prodromal symptom of depression [42]. Insomnia is also expensive for employers in terms of healthcare costs and productivity loss [43]. The identification of hindrance stress as a risk factor for insomnia disorder provides proof-of-concept for future intervention trials examining sleep and stress-focused workplace wellness programs for the primary prevention of insomnia.

In addition, future research of secondary prevention initiatives for insomnia and job stress appears warranted. Approximately 55% of the sample met criteria for insomnia disorder, a much higher prevalence than national estimates of the disorder ranging from 4–27% depending on assessment methodology [37, 38]. Accessible sleep intervention for unemployed individuals has the potential to deter depression and other downstream health effects in this high-risk group of individuals.

The 3P model of insomnia [44] posits that insomnia develops as a result of an acute precipitating event(s) as well as predisposing and perpetuating factors. Hindrance stressors are cumulative, interactional stressors that occurred while employed at the previous job; they are not acute events. Although the entire sample was exposed to job loss, an acute event; this exposure does not explain the relationship between hindrance stressors and insomnia disorder. Moreover, involuntary job loss alone cannot explain the development of insomnia in a significant portion of the sample who were diagnosed with chronic insomnia; 43% of the current insomnia sample had chronic insomnia disorder that began prior to job loss. Therefore, study results suggest that event stressors may not be a necessary condition for the development of insomnia. Consequently, these results support a modification to the 3P model to include other forms of ongoing stress, such as hindrance stressors. Prospective research is necessary to test this claim.

Finally, results from this study support the Challenge-Hindrance framework of work stress, consistent with previous workplace research [14]. Challenge stressors had different associations with insomnia disorder based on insomnia time frame. Challenge stress was associated with an increased likelihood of chronic insomnia but appeared to serve as a potential protective factor to acute insomnia disorder in males. Studies have demonstrated the benefits of challenge stressors, including increased work engagement [34], motivation [45], personal capability [46], and learning [36]. Crane and Searle [47] found that challenge stressors increase psychological resilience, or the ability to adapt in the face of adversity. One interpretation of current findings is that male participants with high levels of challenge stressors on the past job may positively appraise their ability to overcome short-term stressors, such as involuntary job loss; this in turn may reduce the likelihood of developing acute insomnia. This interpretation requires further investigation. However, hardiness, a construct highly associated with resiliency, has been associated with decreased insomnia symptoms in sailors during naval missions [48].

Challenge stressors have also been associated with job strain [13] and emotional exhaustion in teachers [49]. Thus, individuals who experience challenge stressors over a longer period of time may be more likely to develop negative health outcomes; this may be one explanation for the positive relationship between challenge stressors and chronic insomnia. An alternative explanation is that individuals with chronic insomnia are emotionally exhausted and may be more likely to experience or report challenge stressors. Prospective research is necessary to test these possibilities.

Findings from this study highlight the importance of including gender in models assessing occupational stress and sleep. Occupational stress research suggests that women and men are challenged by different stressors in the workplace due to different individual, organizational, and societal factors associated with gender roles, occupational sex classification, and institutionalized gendered expectations [50]. Implicit gender roles in the workplace dictate that ambitious men are often praised for their persistence and willingness to take on challenges outside of their prescribed roles, while women with similar behaviors are seen in a negative light [51]. Women who pursue leadership roles and related additional challenges in the workplace are often perceived as violating unspoken gender norms [52] and may experience workplace bias for demonstrating ambitious or stereotypical masculine behaviors [53, 54]. In addition to workplace bias, employed women in heterosexual partnerships continue to experience a disproportionate number of household task demands compared to their male counterparts [55–58]. Thus, exposure to additional challenge stressors at work may not confer a resiliency effect for women. Taken together, these findings contribute to our understanding of factors that may lead to higher rates of insomnia in women as compared to men [59].

Results of the study must be interpreted with consideration of the cross-sectional sample, which precludes the ability to make strong causal claims. Reverse or bidirectional pathways may be plausible since insomnia has been shown to contribute to the development of workplace difficulties including absenteeism, reduced productivity, and increased accidents [60]. Future research could address causality by examining the timeframe of hindrance stressors in relation to insomnia disorder onset. In addition, prospective studies could address the potential of retrospective recall bias, including whether individuals with insomnia disorder or individuals who have involuntarily lost their jobs are more likely to report past, job-related hindrance stressors. It is plausible that people who are fired due to performance issues may perceive their previous job as having more hindrance stress than people who lost their jobs as part of a mass downsizing. The identification of intermediary mechanisms by which hindrance stress contributes to insomnia could inform future intervention. Also, research is necessary examining variables that could modify the relationship between stress and sleep, such as industry and type of employment.

Although total population sampling was employed, participation was voluntary, suggesting that the sample may represent a group of individuals more likely to participate in research. Odds ratios must be interpreted with caution given the high prevalence of insomnia in this sample. Despite these limitations, this study has a number of strengths, including: control of sleep disordered breathing, age, sex, education, and job loss factors; the assessment of insomnia disorder via semi-structured interview, an outcome with high clinical relevance; and a diverse sample of individuals from a wide-range of industries with demographics representative of the U.S. Southwest.

Conclusion

Although a substantial body of research has documented relationships between workplace stress and sleep, few studies have examined perceptions of past workplace stress on current sleep after involuntary job loss. The current study demonstrates that hindrance stressors from a previous job are associated with increased odds of insomnia disorder. These findings challenge a common assumption that the effect of workplace stressors ends with the termination of employment, although future, prospective research is necessary to test this claim specifically. These findings also highlight the value of applying theory-based frameworks for stress when examining sleep outcomes.

Acknowledgments:

We would like to thank the Arizona Department of Economic Security for their partnership in recruiting participants on the study. This study would like to acknowledge the contribution and assistance of Jesi Post, April Brookshier, Devan Gengler, Candace Mayer, and Darlynn Rojo-Wissar for their contributions coordinating study activity and collecting data. This work is supported by the US National Institute of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI,1R01HL117995-01A1).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Patricia L. Haynes, University of Arizona.

Rebecca L. Wolf, University of Arizona, A.T Still University.

George W. Howe, George Washington University.

Monica R. Kelly, University of Arizona, Sepulveda VA Medical Center.

References

- 1.Reid KJ, Martinovich Z, Finkel S, et al. Sleep: a marker of physical and mental health in the elderly. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(10):860–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong ML, Lau EYY, Wan JHY, Cheung SF, Hui CH, Mok DSY. The interplay between sleep and mood in predicting academic functioning, physical health and psychological health: a longitudinal study. J Psychosom Res. 2013;74(4):271–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spielman AJ, Glovinsky P. The varied nature of insomnia. In: Hauri P, editor. Case studies in insomnia. New York: Plenum Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farber HS. Job loss in the Great Recession: Historical perspective from the Displaced Workers Survey, 1984–2010. National Bureau of Economics, NBER Working Paper No. 17040, Cambridge, MA; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Price RH, Choi JN, Vinokur AD. Links in the chain of adversity following job loss: how financial strain and loss of personal control lead to depression, impaired functioning, and poor health. J Occup Health Psychol. 2002;7(4):302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xiang Y-T, Ma X, Cai Z-J, et al. The prevalence of insomnia, its sociodemographic and clinical correlates, and treatment in rural and urban regions of Beijing, China: a general population-based survey. Sleep. 2008;31(12):1655–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doi Y, Minowa M, Okawa M, Uchiyama M. Prevalence of sleep disturbance and hypnotic medication use in relation to sociodemographic factors in the general Japanese adult population. J Epidemiol. 2000;10(2):79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weller SA. Financial stress and the long-term outcomes of job loss. Work Employ Soc. 2012;26(1):10–25. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Warr P. Job loss, unemployment and psychological well-being. Role transitions: Springer; 1984. p. 263–85. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Virtanen P, Janlert U, Hammarstrom A. Exposure to temporary employment and job insecurity: a longitudinal study of the health effects. Occ Environ Med. 2011;68(8):570–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheng X, Wang Y, Hong W, Zhu Z, Zhang X. The curvilinear relationship between daily time pressure and work engagement: The role of psychological capital and sleep. Int J Stress Manag. 2019;26(1):25. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Webster JR, Beehr TA, Christiansen ND. Toward a better understanding of the effects of hindrance and challenge stressors on work behavior. J Voc Behav. 2010;76(1):68–77. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Podsakoff NP, LePine JA, LePine MA. Differential challenge stressor-hindrance stressor relationships with job attitudes, turnover intentions, turnover, and withdrawal behavior: a meta-analysis. J Appl Psychol. 2007;92(2):438–54. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.2.438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.French KA, Allen TD, Henderson TG. Challenge and hindrance stressors in relation to sleep. Soc Sci Med. 2019;222:145–53. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakata A, Haratani T, Takahashi M, et al. Job stress, social support, and prevalence of insomnia in a population of Japanese daytime workers. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59(8):1719–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pereira D, Elfering A. Social stressors at work, sleep quality and psychosomatic health complaints—a longitudinal ambulatory field study. Stress and Health. 2014;30(1):43–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knudsen HK, Ducharme LJ, Roman PM. Job stress and poor sleep quality: data from an American sample of full-time workers. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(10):1997–2007. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karasek RA Jr. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Admin Sci Quart. 1979:285–308. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siegrist J, Siegrist K, Weber I. Sociological concepts in the etiology of chronic disease: the case of ischemic heart disease. Soc Sci Med. 1986;22(2):247–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haynes PL, Silva GE, Howe GW, et al. Longitudinal assessment of daily activity patterns on weight change after involuntary job loss: the ADAPT study protocol. BMC Pub Health. 2017;17(1):793. 10.1186/s12889-017-4818-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cavanaugh MA, Boswell WR, Roehling MV, Boudreau JW. An empirical examination of self-reported work stress among US managers. J Appl Psychol. 2000;85(1):65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59 Suppl 20:22–33;quiz 4–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edinger JD, Kirby AC, Lineberger MD, Loiselle MM, Wohlgemuth WK, Means MK. Duke Structured Interview Schedule for DSM-IV-TR and International Classification of Sleep Disorders, Second Edition (ICSD-2) Sleep Disorder Diagnoses. Durham, North Carolina: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edinger JD, Wyatt JK, Stepanski EJ, et al. Testing the reliability and validity of DSM-IV-TR and ICSD-2 insomnia diagnoses: results of a multitrait-multimethod analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(10):992–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hosmer DW Jr, Lemeshow S, Sturdivant RX. Applied logistic regression: John Wiley & Sons; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Green MJ, Espie CA, Benzeval M. Social class and gender patterning of insomnia symptoms and psychiatric distress: a 20-year prospective cohort study. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:152. doi: 10.1186/1471-244x-14-152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu M, Taylor JL, Perrin NA, Szanton SL. Distinct clusters of older adults with common neuropsychological symptoms: Findings from the National Health and Aging Trends Study. Geriatr Nurs. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2019.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smagula SF, Stone KL, Fabio A, Cauley JA. Risk factors for sleep disturbances in older adults: Evidence from prospective studies. Sleep Med Rev. 2016;25:21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2015.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marinaccio A, Ferrante P, Corfiati M, et al. The relevance of socio-demographic and occupational variables for the assessment of work-related stress risk. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1157. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaspersen SL, Pape K, Vie GA, et al. Health and unemployment: 14 years of follow-up on job loss in the Norwegian HUNT Study. Eur J Public Health. 2016;26(2):312–7. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckv224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Allison PD. Logistic Regressing Using SAS: Theory and Application. Second ed. Cary NC: SAS Institute Inc.; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 32.U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Labor force characteristics by race and ethnicity, 2019. Washington, DC: Division of Information and Marketing Services; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Standard Occupational Classification Policy Committee (SOCPC). 2010 SOC User Guide. Washington, D; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crawford ER, Lepine JA, Rich BL. Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: a theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. J Appl Psychol. 2010;95(5):834–48. doi: 10.1037/a0019364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li F, Wang G, Li Y, Zhou R. Job demands and driving anger: The roles of emotional exhaustion and work engagement. Accid Anal Prev. 2017;98:198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2016.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prem R, Ohly S, Kubicek B, Korunka C. Thriving on challenge stressors? Exploring time pressure and learning demands as antecedents of thriving at work. J Organ Behav. 2017;38(1):108–23. doi: 10.1002/job.2115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roth T, Coulouvrat C, Hajak G, et al. Prevalence and perceived health associated with insomnia based on DSM-IV-TR; International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision; and Research Diagnostic Criteria/International Classification of Sleep Disorders, Second Edition criteria: results from the America Insomnia Survey. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69(6):592–600. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Olfson M, Wall M, Liu SM, Morin CM, Blanco C. Insomnia and Impaired Quality of Life in the United States. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(5). doi: 10.4088/JCP.17m12020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hsu CY, Chen YT, Chen MH, et al. The Association Between Insomnia and Increased Future Cardiovascular Events: A Nationwide Population-Based Study. Psychosom Med. 2015;77(7):743–51. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vgontzas AN, Liao D, Pejovic S, Calhoun S, Karataraki M, Bixler EO. Insomnia with objective short sleep duration is associated with type 2 diabetes: A population-based study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(11):1980–5. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seow LSE, Verma SK, Mok YM, et al. Evaluating DSM-5 Insomnia Disorder and the Treatment of Sleep Problems in a Psychiatric Population. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14(2):237–44. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baglioni C, Battagliese G, Feige B, et al. Insomnia as a predictor of depression: a meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. J Affect Disord. 2011;135(1–3):10–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sarsour K, Kalsekar A, Swindle R, Foley K, Walsh JK. The association between insomnia severity and healthcare and productivity costs in a health plan sample. Sleep. 2011;34(4):443–50. doi: 10.1093/sleep/34.4.443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spielman AJ, Yang C-M, Glovinsky PB. 25 Insomnia: Sleep Restriction Therapy. Diag Treat. 2016:277. [Google Scholar]

- 45.LePine JA, Podsakoff NP, LePine MA. A meta-analytic test of the challenge stressor–hindrance stressor framework: An explanation for inconsistent relationships among stressors and performance. Acad Manag J. 2005;48(5):764–75. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van den Broeck A, De Cuyper N, De Witte H, Vansteenkiste M. Not all job demands are equal: Differentiating job hindrances and job challenges in the Job Demands–Resources model. Eur J Work Org Psychol. 2010;19(6):735–59. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crane MF, Searle BJ. Building resilience through exposure to stressors: The effects of challenges versus hindrances. J Occ Health Psychol. 2016;21(4):468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nordmo M, Hystad SW, Sanden S, Johnsen BH. The effect of hardiness on symptoms of insomnia during a naval mission. Int Marit Health. 2017;68(3):147–52. doi: 10.5603/imh.2017.0026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu H, Qiu S, Dooley LM, Ma C. The Relationship between Challenge and Hindrance Stressors and Emotional Exhaustion: The Moderating Role of Perceived Servant Leadership. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;17(1). doi: 10.3390/ijerph17010282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Juster R-P, Moskowitz D, Lavoie J, D’Antono B. Sex-specific interaction effects of age, occupational status, and workplace stress on psychiatric symptoms and allostatic load among healthy Montreal workers. Stress. 2013;16(6):616–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.MacKenzie Davey K. Women’s accounts of organizational politics as a gendering process. Gender Work Org. 2008;15(6):650–71. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dennis MR, Kunkel AD. Perceptions of men, women, and CEOs: The effects of gender identity. Soc Behav Personal. 2004;32(2):155–71. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Phelan JE, Rudman LA. Prejudice toward female leaders: Backlash effects and women’s impression management dilemma. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2010;4(10):807–20. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heilman ME. Gender stereotypes and workplace bias. Research in organizational Behavior. 2012;32:113–35. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Van der Lippe T, De Ruijter J, De Ruijter E, Raub W. Persistent inequalities in time use between men and women: A detailed look at the influence of economic circumstances, policies, and culture. Eur Sociol Rev. 2011;27(2):164–79. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Artazcoz L, Artieda L, Borrell C, Cortès I, Benach J, García V. Combining job and family demands and being healthy: What are the differences between men and women? Eur J Public Health. 2004;14(1):43–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Craig L. Does father care mean fathers share? A comparison of how mothers and fathers in intact families spend time with children. Gender Society. 2006;20(2):259–81. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lachance-Grzela M, Bouchard G. Why do women do the lion’s share of housework? A decade of research. Sex roles. 2010;63(11–12):767–80. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang B, Wing Y-K. Sex differences in insomnia: a meta-analysis. Sleep. 2006;29(1):85–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Daley M, Morin CM, LeBlanc M, Gregoire JP, Savard J, Baillargeon L. Insomnia and its relationship to health-care utilization, work absenteeism, productivity and accidents. Sleep Med. 2009;10(4):427–38. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2008.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]