Abstract

Background/Purpose:

Poretti-Boltshauser syndrome is a rare, nonprogressive neurologic syndrome with characteristic cerebellar cysts on neuroimaging due to mutations in LAMA1. The ophthalmic findings in Poretti-Boltshauser syndrome are not well described. Here, we report the ophthalmic findings from multimodal imaging and electrophysiology of a patient with genetically confirmed Poretti-Boltshauser syndrome.

Methods:

A 3-year-old boy with confirmed mutations in LAMA1 underwent examination under anesthesia with electroretinography and multimodal imaging including fundus photography, fluorescein angiography, optical coherence tomography, and optical coherence tomography angiography.

Results:

Dilated fundus examination was notable for retinal vascular anomalies, including a large area of nonperfusion in the temporal macula with corresponding retinal thinning on optical coherence tomography. There was an absence of a distinct foveal avascular zone and decreased density of both the superficial and deep vascular plexuses in the macula on optical coherence tomography angiography. There was diffuse loss of choriocapillaris architecture and decreased choroidal thickness.

Conclusion:

Patients with Poretti-Boltshauser syndrome may possess chorioretinal thinning and retinal vascular abnormalities appreciable on examination and multimodal imaging. These findings suggest a role for LAMA1 in retinal and choroidal vascular development.

Keywords: electroretinography, fluorescein angiography, pediatric retina, optical coherence tomography, optical coherence tomography angiography, Poretti-Boltshauser syndrome

Poretti-Boltshauser syndrome (PBS) is rare, nonprogressive cerebellar syndrome characterized by ataxia, oculomotor apraxia, and intellectual disability as well as cerebellar dysplasia with cysts on neuroimaging.1 The condition is autosomal recessive due to mutations in LAMA1 (laminin1) (OMIM 150320), which belongs to a class of extracellular matrix proteins required for basement membrane assembly and critical for early embryonic development.1,2 The ophthalmic findings in PBS are not well described. Previous reports range from strabismus, cataracts, high myopia, retinal thinning, to a familial exudative vitreoretinopathy–like manifestation with retinal avascularity and neovascularization.1-3 Here, we report the first multimodal imaging and electroretinographic findings on the same patient to characterize the ophthalmic features of this rare disease.

Case Report

A 3-year-old boy, born to nonconsanguineous parents, was diagnosed with PBS due to compound heterozygous mutations in LAMA1 (R782X and Q1838X). He had multiple abnormalities on brain MRI including cerebellar cysts, absent septum pellucidum, partial agenesis of corpus callosum, and periventricular leukomalacia.

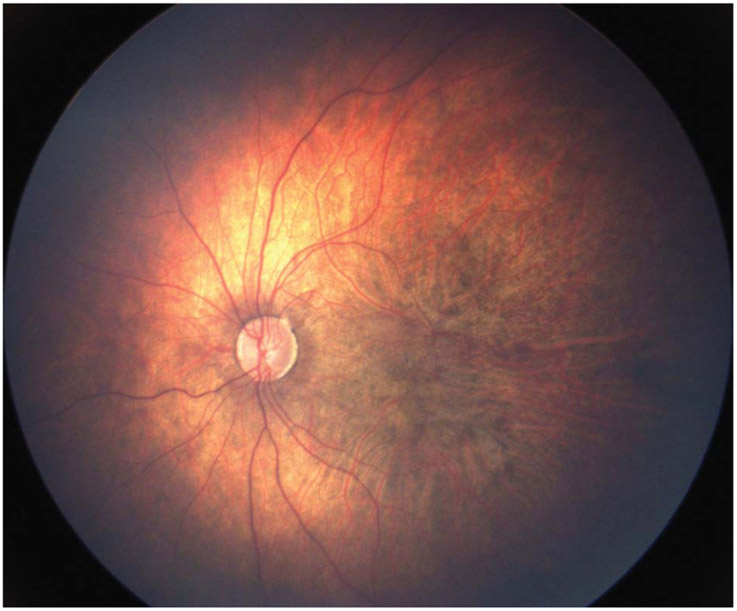

The patient was visually attentive but measured central unsteady and maintained in each eye with an alternating esotropia. On examination under general anesthesia, cycloplegic refraction with retinoscopy showed a refractive error of −16.50 diopters in both eyes. His anterior segment was normal, without cataract in either eye. His fundus examination showed mild pallor of the optic nerves, posterior staphyloma, prominent large choroidal vessels, diffuse patchy pigmentation, absence of the retinal vessels in the temporal macula out to the midperiphery, and blunted retinal vessels peripherally in both eyes (Figure 1).

Fig. 1.

Fundus photograph of the left eye shows a pale optic nerve, posterior staphyloma, diffuse patchy pigmentation, prominence of the large choroidal vessels, and an apparent absence of retinal vessels in the temporal macula.

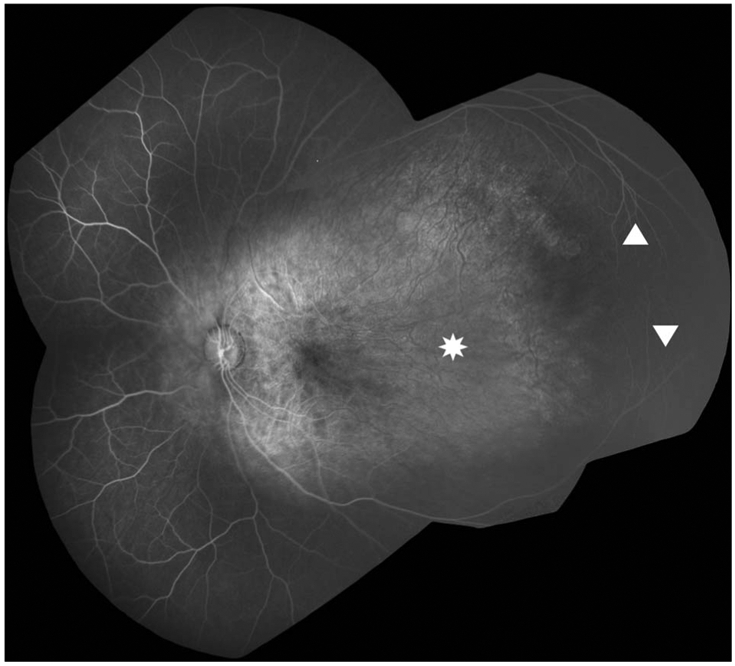

Fluorescein angiography demonstrated prominent choroidal vasculature suggestive of diffuse loss of the overlying choriocapillaris (Figure 2). The area of retinal avascularity in the temporal macula and midperiphery was encircled by arching vasculature from the superior and inferior arcades that reach each other at a peripheral temporal raphe. Retinal vessels in the periphery were present but with decreased density, and there was no evidence of fibrovascular proliferation or vitreoretinal traction with dragging of retinal vessels.

Fig. 2.

Fluorescein angiography montage image of the left eye shows absence of retinal vasculature from the temporal macula to the midperiphery (asterisk). This area is encircled by arcuate vessels from the superior and inferior arcades (triangles). Retinal vessels elsewhere are present nasally and peripherally but have decreased density. There is no fibrovascular proliferation or vitreoretinal traction.

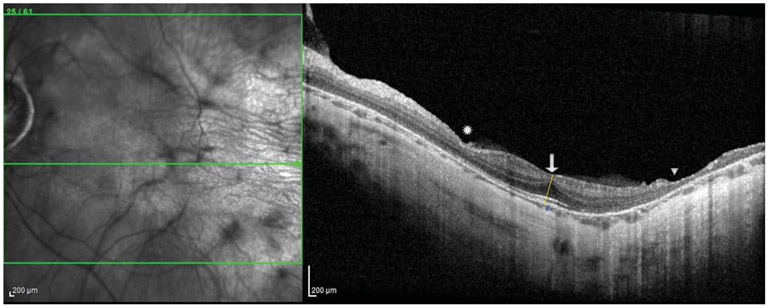

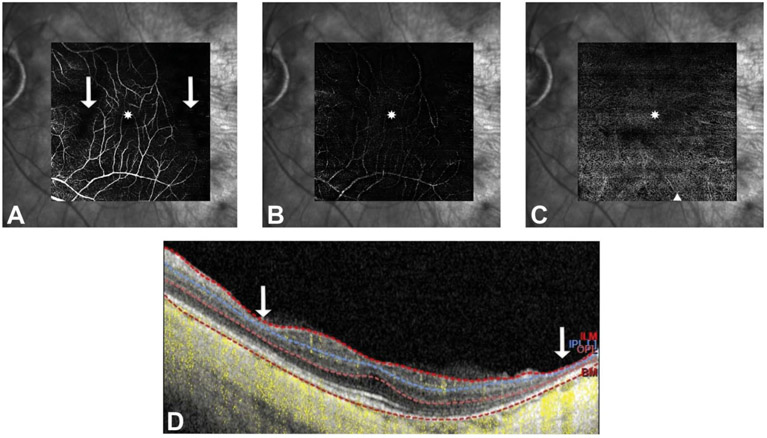

Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (OCT) and OCT angiography (OCTA) images were taken using the HRA + OCT SPECTRALIS with OCTA Module and the investigational Flex module (Heidelberg, Germany) under Institutional Review Board approval and after informed consent was obtained. Structural OCT (30° × 30) showed a mild epiretinal membrane, blunted foveal contour, intact outer retinal bands subfoveally in both eyes, and central foveal thickness of 275 μM in the right eye and 250 μM in the left eye. There was a focal area of retinal thinning in the nasal macula and a larger area in the temporal macula both corresponding to areas of nonperfusion starting 4.3 mm and 2.5 mm temporal to the foveal center in the right and left eyes, respectively (Figure 3). There was widespread choroidal thinning seen in the macula with subfoveal choroidal thickness of 70 μM in the right eye and 35 μM in the left eye. Although the quality of OCTA (20° × 20°) was limited by high myopia, it revealed more vessels than were appreciated on fluorescein angiography. In the superficial vascular complex, the vasculature was vertically straightened crossing the horizontal raphe from both above and below including temporal to the fovea. There was absence of a distinct foveal avascular zone and decreased vessel density even in areas where the retinal laminations appeared intact (Figure 4A). In the deep vascular complex and in the choriocapillaris, there were similar areas of profoundly decreased vessel density diffusely (Figure 4, B and C), although image quality in these slabs was limited.

Fig. 3.

Optical coherence tomography at the fovea shows persistence of the inner retinal layers (arrow), focal areas of inner retinal thinning nasally (asterisk) and profound total retinal thinning in the temporal macula (triangle) corresponding to areas of nonperfusion, and a severely thin choroid. The retinal thickness in the central 1-mm subfield is 224 and 231 μM, the central foveal thickness measured at the yellow line is 275 and 250 μM, and the central choroidal thickness measured at the blue line is 70 and 35 μM in the right and left eyes, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Optical coherence tomography angiography shows vertically oriented superficial retinal vessels, absence of the foveal avascular zone (asterisk), and profoundly decreased vessel density in the deep vascular complex (B) more so than superficial (A). There are no vessels visualized in a small area in the nasal macula and in a larger area in the temporal macula (arrows) that correspond to inner retinal thinning (arrows) seen on a sample B-scan through the fovea with OCTA flow overlay (yellow) and segmentation overlay (dotted lines) (D). Optical coherence tomography angiography of the choriocapillaris (C) also demonstrates decreased vascular density with increased visibility of the underlying larger choroidal vessels (triangle).

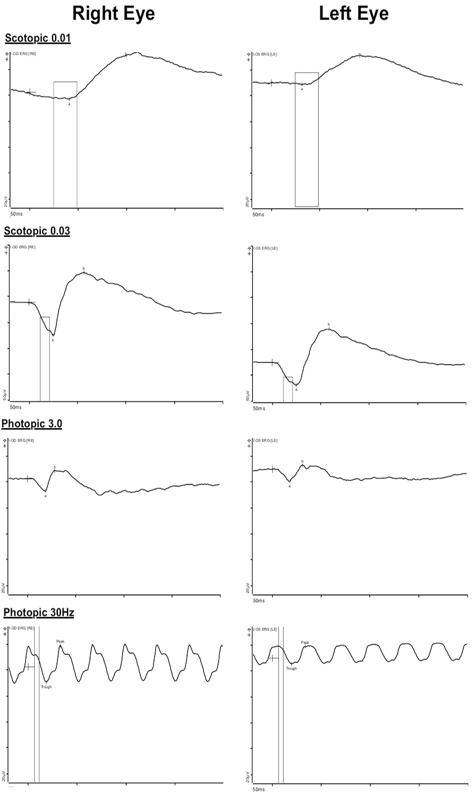

Full-field electroretinography (ERG), following the standards of the International Society of Clinical Electrophysiology of Vision (ISCEV), was recorded from both eyes (Color Dome Ganzfeld Diagnosys unit, Diagnosys, MA). Dark-adapted ERG (rod response, maximal response) was obtained after 20 minutes of dark adaptation and light adaption responses (cone response and 30-Hz Flicker), after 3 minutes of light adaptation. The results were compared with normative data after adjusting for age and refractive error (C.R.A.C.K. ERG, Toronto, Canada). The ERG showed a mildly reduced b-wave in both eyes, left greater than right, more in photopic than scotopic conditions, suggestive of inner retinal dysfunction primarily affecting the cone signal (Figure 5).

Fig. 5.

The b-wave is mildly reduced (to 57% compared with normal controls in photopic conditions) in both eyes, left greater than right, suggesting dysfunction of the inner retina for cones greater than rod signal.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this report is the first to characterize the ocular findings in PBS using electrophysiology and multimodal imaging. Macular abnormalities have never been described in this syndrome, and here, we report abnormal foveal development with indistinct foveal avascular zone and corresponding lack of foveal depression. We visualized more retinal vessels in the macula on OCTA than were readily apparent on fundus examination or fluorescein angiography alone. The retinal vessels in the macula were abnormal with regions of nonperfusion in the nasal and temporal macula and involving both the superficial and deep capillary plexuses. These areas of avascularization corresponded to severe inner retinal thinning seen on structural analysis with OCT. The patient’s high myopia (−16 diopters) with posterior staphyloma also contributed to the chorioretinal thinning seen. This report is also the first to show mildly reduced b-wave on full-field ERG, suggestive of more global inner retinal dysfunction beyond the macula, likely related to the retinal vascular developmental abnormalities.

To date, there are only a few reports in the literature describing ocular findings in PBS and only one description of the retinal vasculature. Marlow et al3 reported a pair of siblings who had compound heterozygous mutations in LAMA1 (R222X and Y777X). These two patients, similar to our case, had a large area of avascularity posteriorly with visible retinal vessels in the midperiphery. The retinal vascular changes described previously and found in this case are similar to familial exudative vitreoretinopathy with large areas of avascular retina. However, in contrast to the temporal dragging of vessels classically seen in familial exudative vitreoretinopathy, this case demonstrates vertically elongated macular vessels that cross the horizontal raphe. Poretti-Boltshauser syndrome also has similarities to incontinentia pigmenti, another inherited (X-linked) condition with congenital vascular abnormalities often with patchy peripheral retinal avascularity and corresponding inner retinal thinning, including in the macula.

The structural and vascular abnormalities in this case highlight the critical role of laminins in human ocular development. Laminins are a family of heterotrimeric glycoproteins within basement membranes and the extracellular matrix that are expressed during the early stages of embryonic development and play an important role in neuronal migration and normal embryologic development.4 Insights from animal models suggest that laminin-1 is vital to lens development, retinal organization, and retinal vascular angiogenesis. Studies using mouse models have shown that LAMA1 is critical for the formation of the internal limiting membrane on which astrocytes rely for migration and in turn dictate angiogenesis.5 Disruptions of this process lead to abnormalities of vascular development characterized by persistence of the hyaloidal vessels and disorganization of the capillary network with a higher density of capillary branch points. Laminins intersect with the Wnt signaling pathway which is implicated in familial exudative vitreoretinopathy, and they have also been shown to alter the activation of nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-kB) which is the transcription factor implicated in incontinentia pigmenti.6,7 Laminin also localizes to Bruch membrane, which functions as the basement membrane for the choriocapillaris and the large choroidal vessels.8 Similar to our case, mutations in other laminin genes, including LAMAB2 in the setting of Pierson syndrome, result in decreased choroidal thickness.9

The retinal abnormalities in PBS are progressive, and these patients require close follow-up. In the report by Marlow et al,3 one patient went on to develop retinal neovascularization in both eyes with preretinal hemorrhages then treated with laser photocoagulation to the avascular retina. The patient also developed an atrophic hole at the edge of avascular retina and underwent laser retinopexy around the retinal break.3 Similarly, mice models of LAMA1 are prone to retinal detachments, likely a result of progressive retinal atrophy.10

This case highlights the structural, vasculature, and functional abnormalities in PBS and emphasizes the role of LAMA1 on human ocular development. Clinicians should consider PBS on the differential diagnosis in young patients with congenital vascular abnormalities in the context of neurologic findings (e.g., ataxia) and be aware that these patients may be susceptible to long-term ocular complications including neovascularization and retinal detachment.

Acknowledgments

Funding: R01 EY025009, R21 EY029384, Heed Ophthalmic Foundation.

Footnotes

C. A. Toth: Alcon royalties (through Duke for surgical technology), Hemasonics: royalties. The remaining authors have no conflict of interests to disclose.

References

- 1.Micalizzi A, Poretti A, Romani M, et al. Clinical, neuroradiological and molecular characterization of cerebellar dysplasia with cysts (Poretti-Boltshauser syndrome). Eur J Hum Genet 2016;24:1262–1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aldinger KA, Mosca SJ, Tétreault M, et al. Mutations in LAMA1 cause cerebellar dysplasia and cysts with and without retinal dystrophy. Am J Hum Genet 2014;95:227–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marlow E, Chan RVP, Oltra E, et al. Retinal avascularity and neovascularization associated with LAMA1 (laminin1) mutation in poretti-boltshauser syndrome. JAMA Ophthalmol 2018;136:96–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vilboux T, Malicdan MCV, Chang YM, et al. Cystic cerebellar dysplasia and biallelic LAMA1 mutations: a lamininopathy associated with tics, obsessive compulsive traits and myopia due to cell adhesion and migration defects. J Med Genet 2016;53:318–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Sullivan ML, Puñal VM, Kerstein PC, et al. Astrocytes follow ganglion cell axons to establish an angiogenic template during retinal development. Glia 2017;65:1697–1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bailey RL, Herbert JM, Khan K, et al. The emerging role of tetraspanin microdomains on endothelial cells. Biochem Soc Trans 2011;39:1667–1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou YW, Munoz J, Jiang D, Jarrett HW. Laminin-α1 LG4-5 domain binding to dystroglycan mediates muscle cell survival, growth, and the AP-1 and NF-kB transcription factors but also has adverse effects. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2012;302:C902–C914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marshall GE, Konstas AG, Reid GG, et al. Type IV collagen and laminin in Bruch’s membrane and basal linear deposit in the human macula. Br J Ophthalmol 1992;76:607–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arima M, Tsukamoto S, Akiyama R, et al. Ocular findings in a case of Pierson syndrome with a novel mutation in laminin ß2 gene. J AAPOS 2018;22:401–403.e401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edwards MM, Mammadova-Bach E, Alpy F, et al. Mutations in Lama1 disrupt retinal vascular development and inner limiting membrane formation. J Biol Chem 2010;285:7697–7711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]