Abstract

Due to high consumption of cosmetics in modern society, people are always exposed to the risk of skin damage and complications. Para-phenylenediamine (P-PD), an ingredient of hair dye, has been reported to cause allergic contact dermatitis. However, the mechanism has not been well elucidated. Here, we identify that P-PD causes dermatitis by increasing thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) and inflammatory cytokines. Topical application of P-PD to mouse ear skin in consecutive 5 days resulted in dermatitis symptoms and increased ear thickness. TSLP production in skin was upregulated by P-PD treatment alone. In addition, P-PD-induced TSLP production was potentiated by MC903, which is an in vivo TSLP inducer. P-PD increased TSLP production in keratinocytes (KCMH-1 cells and phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate-stimulated PAM212 cells). The production of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, IFN-γ, and CCL2, was upregulated by P-PD treatment together with MC903. The results show that repeated exposure to P-PD causes acute contact dermatitis mediated by increasing the expression of TSLP and proinflammatory cytokines.

Keywords: Dermatitis, Cytokines, Cosmetics, Infammation, Immunity, Risk

Introduction

People use several kinds of cosmetics for various purpose such as beautifying their appearances, cleansing body and anti-aging. Cosmetics are commonly composed of chemical compounds. Therefore, direct exposure to the skin has the potential to cause skin damage and complications. According to the report in United States, woman uses 12 cosmetics and man uses 6 cosmetics daily on average [1]. These cosmetics include eye shadow, skin cleansers, body lotions, shampoo, lip stick, mascara and hair styling products. Among them, the use of hair dyes has been increasing in recent decades, and the occurrence of contact sensitization to hair dyes has been consistently reported [2].

Over two-thirds of hair dyes currently contain para-phenylenediamine (P-PD) [3]. P-PD is an aromatic amine that reacts with hydrogen peroxide to give permanent hair colors. Because of its strong protein-binding capacity and penetrating deeply, P-PD is found in several products such as rubbers, printer ink, and photographic products. The main sources are hair dyes and henna tattoos [4]. Since P-PD provides very good cosmetic results as a hair dye ingredient, it is preferred and widely used. However, P-PD easily infiltrates skin, causing skin sensitization and allergic contact dermatitis [5]. The prevalence of P-PD sensitization varies between 0 and 1.5% in the general population while it increases to 4% with patch testing [6]. As an extremely potent sensitizer, P-PD causes acute dermatitis accompanied by redness, itching, and swelling in the scalp and nape area [7, 8]. It has been reported that P-PD acts as a contact allergen for many years [9–11]. However, there has been few report addressing how P-PD would cause skin inflammatory reaction and allergic contact dermatitis.

Thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) is especially expressed in large amount by keratinocytes and plays an important role in the elicitation phase of skin inflammation and mediates the progression of atopic dermatitis [12]. TSLP also promotes the differentiation to Th2 cells from naïve CD4+ T cells. Increased Th2 cells induces Th2-type immune responses and produce Th2 cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 [13]. In addition, TSLP synergistically respond with IL-1β, to activate mast cells to release Th2 cytokines and chemokines largely in the elicitation-phase of dermatitis [14].

Therefore, in this study, we investigated whether P-PD exposure induces the production of TSLP in keratinocytes, thereby inducing acute dermatitis symptoms. The results would provide an important information on elucidating the cellular mechanism as to how P-PD induces allergic contact dermatitis.

Materials and methods

Animals

BALB/c mice were obtained from Raon Bio (Seoul, Korea). The mice were housed in a room controlled for optimal temperature (23 ± 3 °C) and relative humidity (40–60%) under specific pathogen-free conditions. Mice were acclimated in the animal facility for at least a week before the experiments. Animal care and the experimental protocols were carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Catholic University of Korea (permission #2016-006-03) and the ARRIVE guidelines. Mice of individual experimental groups in each experiment were of similar age and weight and randomly allocated to treatment groups. Investigators were not given the information on treatment of mice in all experiments.

Cells

The murine keratinocyte squamous cell carcinoma cell line KCMH-1, which was derived from CBA/J mouse skin, was kindly provided by Dr. Noriyasu Hirasawa at the Tohoku University [15]. PAM212 cells, a mouse keratinocyte cell line, which was derived from BALB/c mouse skin, was kindly provided by Dr. Stuart H. Yuspa at the National Cancer Institute (Bethesda, MD, USA) [16]. KCMH-1 and PAM212 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) including 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum, 10,000 units/ml of penicillin and 10,000 μg/ml of streptomycin. The cells were plated in 48-well plates at a density of 5 × 104 cells/well and incubated overnight before the treatments.

Reagents

Para-phenylenediamine (P-PD), MC903 (calcipotriol), MTT (thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide) and phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Acute dermatitis model in mouse

BALB/c mice were randomly divided into 4 groups: vehicle (3:1 mixture of acetone:olive oil), P-PD (2.5%), MC903 0.5 nmole + 2.5% P-PD, and MC903 5 nmole (3 animals/group). Acute dermatitis was induced by repeated topical application of P-PD and MC903, as described previously [17]. Briefly, 20 μl of P-PD, P-PD + MC903, MC903 or vehicle was topically applied to the dorsal sides of right and left ears of each mouse daily for 5 days. Ear thickness was recorded every day before treatment. At day 6, mice were sacrificed to obtain ear skin tissues. The samples were stored at − 80 °C pending further analysis.

Reverse transcription and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis

This was performed as described previously [18]. Total RNAs were extracted from mouse ear tissues using WelPrep reagent (Welgene, Korea). Reverse transcription and qRT-PCR analysis was performed using ImProm-II Reverse Transcriptase and amplified using SYBR Premix for quantitative real-time PCR analysis. Primers used were as follows: Tslp, 5′-GGACCACTG GTGTTTATTCT-3′ and 5′-CAGGGTTTAG ATGCTGTCAT-3′; Il-4, 5′-AGATGGATGTGCCAAACGTCCTCA-3′ and 5′-AATATGCGAAGCACCTTGGAAGCC-3′; Il-13, 5′-GCAACGGCAG CATGGTATGG A-3′ and 5′-TGGTATAGGG GAGGCTGGAG AC-3′; Actin, 5′-TCATGAAGTGTGACGTTG ACATCCGT-3′ and 5′-TTGCGGTGCACGATGGAGGGGCCGGA-3′. Specificity of the amplified PCR products was assessed by melting curve analysis, and the gene expression was normalized to the corresponding actin level.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays

This was performed as described previously [19]. TSLP and IL-1β levels in ear skin homogenates were determined using a DuoSet enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The levels of IL-25, IL-33, IL-4, IL-13, IL-6, IFN-γ and CCL2 were measured using a MILLIPLEX MAP Mouse Cytokine (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The fluorescent intensity was read on a MAGPIX® (Luminex Corporation, Austin, TX, USA).

Cell viability assay

Cell viability studies were performed in 48-well plates. KCMH-1 and PAM212 cells were plated 5 × 104 cells/well. After overnight incubation, the test substances were treated, and the plates were incubated for 16 h. Cells were washed once before adding medium containing MTT (5 mg/ml). After 4 h of incubation at 37 °C, the medium was discarded and the formazan blue that formed in the cells were dissolved in DMSO. The optical density was measured at 540 nm.

Immunoblotting analysis

PAM212 cells were plated in six-well plates at a density of 1 × 106 cells/well and incubated overnight before the treatments. The cells were treated with PMA (15 nM) or vehicle in the presence or absence of P-PD. After 1 h of incubation, the cells were lysed in RIPA buffer and resolved with SDS-PAGE and subjected to immunoblotting assay.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the software GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). All data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Turkey’s multiple comparison test and expressed as means ± SEM. Values of p < 0.05 were considered significant. The graphs or pictures are representative of at least two or three independent experiments.

Results

Topical application of para-phenylenediamine aggravates acute dermatitis symptoms in mice

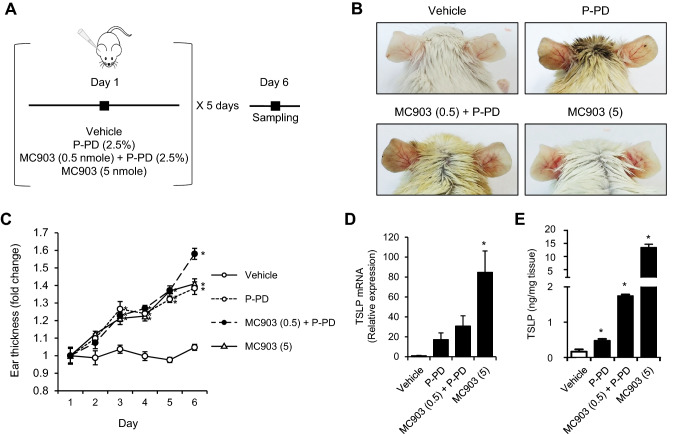

We investigated whether para-phenylenediamine (P-PD) induced acute dermatitis symptoms by increasing TSLP in mice. MC903 (calcipotriol) is well established TSLP inducer in skin and causes atopic dermatitis symptoms [20]. To investigate the potentiation effect of P-PD, MC903 0.5 nmole of which topical application on mouse ear does not induce TSLP production in ear skin was used [17]. To confirm the significant TSLP production, we used 5 nmole of MC903 as a positive control. The acute dermatitis experimental scheme is shown in Fig. 1a. Topical application of P-PD alone and P-PD with 0.5 nmole of MC903 to BALB/c mice induced ear dermatitis symptoms such as redness, erythema and edema (Fig. 1b). Similarly, 5 nmole of MC903 induced acute dermatitis symptoms (Fig. 1b). We measured ear thickness as an indicator of dermatitis as previous studies have shown that ear thickness is well correlated with dermatitis-like symptoms [21, 22]. Mouse ear thickness was compared with vehicle every day. Repeated application of P-PD resulted in increased ear swelling response (Fig. 1c). The stimulation of P-PD with 0.5 nmole of MC903 significantly potentiated ear swelling in day 6 (Fig. 1c). The mRNA levels of TSLP were increased in P-PD alone and P-PD with MC903 compared with vehicle (Fig. 1d). In addition, P-PD increased TSLP protein production (Fig. 1e). P-PD significantly potentiated TSLP production when treated with 0.5 nmole of MC903 (Fig. 1e). These results show that P-PD alone induces acute dermatitis with increased TSLP production in a mouse model and when stimulated together with low level of MC903, the effect of P-PD is potentiated.

Fig. 1.

Topical application of para-phenylenediamine aggravates acute dermatitis symptoms in mice. a Experimental scheme. b Representative pictures of mouse ear skin area. c Relative ear thickness. All measured values are normalized to the mean ear thickness for the group on day 1. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM (n = 5). d The mRNA levels of TSLP in ear tissue homogenates were determined by reverse transcription-real time quantitative-PCR. The mRNA levels were normalized with β-actin mRNA levels. e TSLP protein levels in ear tissue homogenates were determined by ELISA. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM (n = 5–6). *Significantly different from vehicle alone, p < 0.05. P-PD, para-phenylenediamine; MC903 (0.5), MC903 0.5 nmole; MC903 (5), MC903 5 nmole

Para-phenylenediamine increases TSLP production in keratinocytes

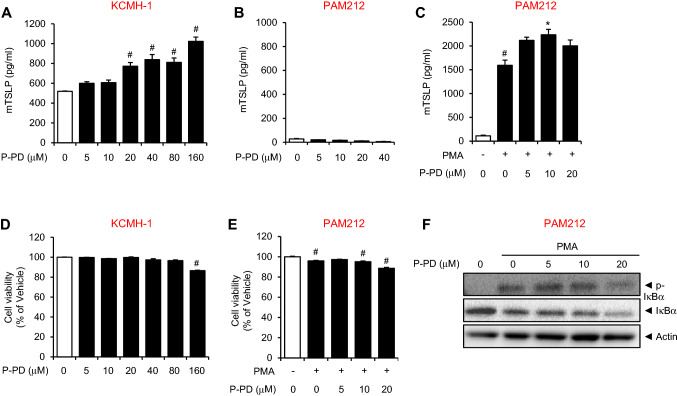

Next, we examined whether P-PD influences TSLP production in keratinocytes. Mouse derived keratinocyte cell line, KCMH-1, which intrinsically produces high amounts of TSLP [15], were treated with P-PD up to 160 μM for 16 h. The levels of TSLP was increased in KCMH-1 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2a). However, P-PD treatment up to 40 μM did not affect TSLP production in another mouse keratinocyte cell line, PAM212 (Fig. 2b). To investigate the potentiation effect of P-PD, PAM212 cells were stimulated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA). P-PD increased the production of TSLP in PAM212 cells stimulated with PMA (Fig. 2c). KCMH-1 cells used in the experiments constitutively produce high amounts of TSLP [15]. The basal levels of TSLP production in KCMH-1 cells are higher than those in PAM212 cells as shown in Fig. 2. These suggest that KCMH-1 cells are more sensitive to P-PD stimuli for inducing TSLP production than PAM212 cells. To examine whether P-PD affected cell viability, MTT assay was performed. Cytotoxicity of both KCMH-1 cells and PAM212 cells was not affected by P-PD with only marginal cytotoxic effects at the highest concentration (Fig. 2d, e).

Fig. 2.

Para-phenylenediamine increases TSLP production in keratinocytes. For a and d, KCMH-1 cells were treated with P-PD for 16 h. For b, c, and e, PAM212 cells were treated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA, 15 nM) and P-PD for 16 h. For a–c, TSLP protein levels in culture media were determined by ELISA. For d and e, cell viability was measured by MTT assay. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM (n = 3). #Significantly different from vehicle alone, p < 0.05. *Significantly different from PMA alone, p < 0.05. f PAM212 cells were treated with PMA (15 nM) in the presence or absence of P-PD for 1 h. Cell lysates were prepared and subjected to immunoblotting for each protein. P-PD, para-phenylenediamine

TSLP expression was regulated by an NF-κB-dependent manner in human epithelial cells [23]. To investigate the mechanism of how P-PD increases TSLP production, we examined the effect of P-PD on NF-κB activation in PAM212 cells (Fig. 2f). PMA induced phosphorylation and degradation of IκBα, while P-PD did not affect PMA-induced IκBα phosphorylation in PAM212 cells (Fig. 2f). P-PD potentiated PMA-induced IκBα degradation only at the highest concentration in PAM212 cells (Fig. 2f).

Topical application of para-phenylenediamine upregulates pro-inflammatory cytokines in mouse ear skin stimulated with MC903

We further examined whether topical application of P-PD affected the expression of inflammatory cytokines and cytokines. P-PD alone increased protein levels of IL-1β, but not IL-6 and IFN-γ (Fig. 3a–c). P-PD-induced production of IL-1β, IL-6, and IFN-γ was potentiated by 0.5 nmole of MC903 (Fig. 3a–c). Furthermore, the production of CCL2, a pro-inflammatory chemokine, was significantly increased by P-PD alone and potentiated by MC903 stimulation (Fig. 3d).

Fig. 3.

Topical application of para-phenylenediamine upregulates proinflammatory cytokines in mouse ear skin. a–d Mice were treated as described in the Fig. 1a. Protein levels of IL-1β, IL-6, IFN-γ, and CCL2 in ear tissue homogenates were determined by ELISA. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM (n = 5–6). *Significantly different from vehicle alone, p < 0.05. P-PD, para-phenylenediamine, MC903 (0.5), MC903 0.5 nmole, MC903 (5) MC903 5 nmole

Topical application of para-phenylenediamine does not induce Th2 responses

With TSLP, IL-25 and IL-33 are known to play an important role in the pathogenesis of allergic diseases [24]. In contrast to TSLP, the expression of IL-25 and IL-33 was not increased by P-PD alone (Fig. 4a, b). The production of IL-25 was significantly increased when P-PD was treated with 0.5 nmole of MC903 (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4.

Topical application of para-phenylenediamine does not induce Th2 responses. a–f Mice were treated as described in the Fig. 1a. a, b, e, f IL-25, IL-33, IL-4 and IL-13 protein levels in ear tissue homogenates were determined by ELISA. c, d The mRNA levels of IL-4 and IL-13 in ear tissue homogenates were determined by reverse transcription-real time quantitative-PCR. The mRNA levels were normalized with β-actin mRNA levels. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM (n = 5–6). *Significantly different from vehicle alone, p < 0.05. n.s. not significant compared to vehicle alone. P-PD, para-phenylenediamine, MC903 (0.5), MC903 0.5 nmole, MC903 (5) MC903 5 nmole

TSLP induces the differentiation of naïve CD4+ cells to Th2 lymphocytes producing Th2 cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-13 [25]. Therefore, we examined whether P-PD induced Th2 cytokine production. The mRNA level of IL-4 was slightly elevated by P-PD while it was significantly increased in P-PD with MC903 group (Fig. 4c). In contrast, the mRNA levels of IL-13 was not significantly changed by P-PD treatment (Fig. 4d). Protein levels of IL-4 and IL-13 were not increased by P-PD or MC903 (Fig. 4e, f).

Discussion

P-PD has long been used as an ingredient of oxidative hair dyes and known to cause contact allergy for many decades. Previous studies have reported that P-PD induces apoptosis in human urothelial cells and exacerbates thrombus formation upon vascular injury [26, 27]. To our knowledge, this study is the first to show that P-PD increases the production of TSLP in keratinocytes and a mouse model. TSLP is primarily secreted by keratinocytes and plays a critical role in the early onset of atopic dermatitis, a representative disease caused by immune imbalances. These suggest that repeated exposure to P-PD may cause atopic dermatitis symptoms through the production of TSLP.

Keratinocytes secrete innate immune cytokines such as IL-1 and IL-6 when exposed to skin injury or ultraviolet B (UVB) light [28, 29]. IFN-γ, a Th1 cytokine that activates dendritic cells, is involved in antigen presenting and plays an essential role in eliciting inflammatory cascade in skin diseases such as psoriasis [30]. CCL2 is a representative pro-inflammatory chemokine generated by keratinocytes [31]. Our results show that P-PD treatment increased the production of IL-1β in skin. Furthermore, P-PD potentiates the production of TSLP, inflammatory cytokines and chemokines when exposed together with a TSLP producer such as MC903. The potentiation of P-PD was observed when P-PD was applied together with low amount (0.5 nmole) of MC903 at which concentration MC903 itself did not induce TSLP in mouse ear skin [17]. These suggest that P-PD toxicity can be aggravated when the skin is sensitized with other stimulation.

The expression of other inflammatory cytokines except TSLP was greater in P-PD + MC903 0.5 nmole group than in MC903 5 nmole alone group. These suggest that there are other mechanisms besides TSLP for upregulating these inflammatory cytokines by P-PD + MC903. Kasi et al. showed that P-PD induced intracellular ROS generation and activated protein tyrosine kinase/Ras/Raf/JNK-dependent signaling pathway in NRK-52E normal rat renal tubular epithelial cell line [32]. It needs to be further elucidated in future study whether P-PD activates the intracellular signaling pathways such as protein tyrosine kinase and JNK in keratinocytes and the activation contributes to the production of the inflammatory cytokines in keratinocytes.

Keratinocytes secrete not only TSLP but also IL-25 and IL-33, which are classified as epithelial cytokines and play an important role in the pathogenesis of mucosal diseases. Especially, TSLP elicits a Th2 immune response and promotes the progression to atopic dermatitis by inducing differentiation of naïve CD4 cells to Th2 cells. Mature Th2 cells produce IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13, which are called Th2 cytokines. In our study, the skin levels of IL-25 and IL-33 were not changed upon P-PD alone while P-PD together with MC903 showed significant increase of IL-25 in skin suggesting that IL-25 induction by P-PD contributes to the acute dermatitis symptoms caused by P-PD. In addition, other Th2 immunity factors such as IL-4 and IL-13 did not show any significant change. These results suggest that 5 days of P-PD application may not be sufficient to induce Th2 responses despite of TSLP production.

Collectively, our results demonstrate that repeated topical application of P-PD increases TSLP production in both keratinocytes and a mouse model. Repeated topical application of P-PD induces the production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines resulting in acute dermatitis. The results suggest that the application of P-PD may cause skin complication and dermatitis, especially when the skin was sensitized.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants (18172MFDS231 and 19172MFDS221) from the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety, Korea in 2018 and 2019.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Chen X, Sullivan DA, Sullivan AG, Kam WR, Liu Y. Toxicity of cosmetic preservatives on human ocular surface and adnexal cells. Exp Eye Res. 2018;170:188–197. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2018.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nohynek GJ, Fautz R, Benech-Kieffer F, Toutain H. Toxicity and human health risk of hair dyes. Food Chem Toxicol Int J Publ Br Ind Biol Res Assoc. 2004;42:517–543. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McFadden JP, White IR, Frosch PJ, Sosted H, Johansen JD, Menne T. Allergy to hair dye. BMJ. 2007;334:220. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39042.643206.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McFadden JP, Yeo L, White JL. Clinical and experimental aspects of allergic contact dermatitis to para-phenylenediamine. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:316–324. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oakes T, Popple AL, Williams J, Best K, Heather JM, Ismail M, Maxwell G, Gellatly N, Dearman RJ, Kimber I, Chain B. The T cell response to the contact sensitizer paraphenylenediamine is characterized by a polyclonal diverse repertoire of antigen-specific receptors. Front Immunol. 2017;8:162. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vogel TA, Coenraads PJ, Bijkersma LM, Vermeulen KM, Schuttelaar ML. p-Phenylenediamine exposure in real life—a case–control study on sensitization rate, mode and elicitation reactions in the northern Netherlands. Contact Dermat. 2015;72:355–361. doi: 10.1111/cod.12354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Basketter DA, Goodwin BF. Investigation of the prohapten concept. Cross reactions between 1,4-substituted benzene derivatives in the guinea pig. Contact Dermat. 1988;19:248–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1988.tb02921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nacaroglu HT, Yavuz S, Basman E, Bahceci S, Tasdemir M, Yigit O, Can D. The clinical spectrum of reactions developed based on paraphenylenediamine hypersensitivity two pediatric cases. Postepy dermatologii i alergologii. 2015;32:393–395. doi: 10.5114/pdia.2015.52738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mukkanna KS, Stone NM, Ingram JR. Para-phenylenediamine allergy: current perspectives on diagnosis and management. J Asthma Allergy. 2017;10:9–15. doi: 10.2147/jaa.S90265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thyssen JP, White JM. Epidemiological data on consumer allergy to p-phenylenediamine. Contact Dermat. 2008;59:327–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2008.01427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma VK, Chakrabarti A. Common contact sensitizers in Chandigarh, India. A study of 200 patients with the European standard series. Contact Dermat. 1998;38:127–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1998.tb05677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ziegler SF. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin and allergic disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:845–852. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leyva-Castillo JM, Hener P, Michea P, Karasuyama H, Chan S, Soumelis V, Li M. Skin thymic stromal lymphopoietin initiates Th2 responses through an orchestrated immune cascade. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2847. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong CK, Hu S, Cheung PF, Lam CW. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin induces chemotactic and prosurvival effects in eosinophils: implications in allergic inflammation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2010;43:305–315. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0168OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Segawa R, Yamashita S, Mizuno N, Shiraki M, Hatayama T, Satou N, Hiratsuka M, Hide M, Hirasawa N. Identification of a cell line producing high levels of TSLP: advantages for screening of anti-allergic drugs. J Immunol Methods. 2014;402:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yuspa SH, Hawley-Nelson P, Koehler B, Stanley JR. A survey of transformation markers in differentiating epidermal cell lines in culture. Cancer Res. 1980;40:4694–4703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang G, Lee HE, Lim KM, Choi YK, Kim KB, Lee BM, Lee JY. Potentiation of skin TSLP production by a cosmetic colorant leads to aggravation of dermatitis symptoms. Chem Biol Interact. 2018;284:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2018.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee HE, Yang G, Han SH, Lee JH, An TJ, Jang JK, Lee JY. Anti-obesity potential of Glycyrrhiza uralensis and licochalcone A through induction of adipocyte browning. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;503:2117–2123. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.07.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang G, Koo JE, Lee HE, Shin SW, Um SH, Lee JY. Immunostimulatory activity of Y-shaped DNA nanostructures mediated through the activation of TLR9. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;112:108657. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.108657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li M, Hener P, Zhang Z, Kato S, Metzger D, Chambon P. Topical vitamin D3 and low-calcemic analogs induce thymic stromal lymphopoietin in mouse keratinocytes and trigger an atopic dermatitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11736–11741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604575103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jang HY, Koo JH, Lee SM, Park BH. Atopic dermatitis-like skin lesions are suppressed in fat-1 transgenic mice through the inhibition of inflammasomes. Exp Mol Med. 2018;50:73. doi: 10.1038/s12276-018-0104-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dai J, Choo MK, Park JM, Fisher DE. Topical ROR inverse agonists suppress inflammation in mouse models of atopic dermatitis and acute irritant dermatitis. J Investig Dermatol. 2017;137:2523–2531. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.07.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee HC, Ziegler SF. Inducible expression of the proallergic cytokine thymic stromal lymphopoietin in airway epithelial cells is controlled by NFkappaB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:914–919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607305104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Divekar R, Kita H. Recent advances in epithelium-derived cytokines (IL-33, IL-25, and thymic stromal lymphopoietin) and allergic inflammation. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;15:98–103. doi: 10.1097/aci.0000000000000133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klonowska J, Glen J, Nowicki RJ, Trzeciak M. New cytokines in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis-new therapeutic targets. Int J Mol Sci. 2018 doi: 10.3390/ijms19103086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reena K, Ng KY, Koh RY, Gnanajothy P, Chye SM. Para-phenylenediamine induces apoptosis through activation of reactive oxygen species-mediated mitochondrial pathway, and inhibition of the NF-kappaB, mTOR, and Wnt pathways in human urothelial cells. Environ Toxicol. 2017;32:265–277. doi: 10.1002/tox.22233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zaid Y, Marhoume F, Senhaji N, Kojok K, Boufous H, Naya A, Oudghiri M, Darif Y, Habti N, Zouine S, Mohamed F, Chait A, Bagri A. Paraphenylene diamine exacerbates platelet aggregation and thrombus formation in response to a low dose of collagen. J Toxicol Sci. 2016;41:123–128. doi: 10.2131/jts.41.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oyoshi MK, He R, Kumar L, Yoon J, Geha RS. Cellular and molecular mechanisms in atopic dermatitis. Adv Immunol. 2009;102:135–226. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(09)01203-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noske K. Secreted immunoregulatory proteins in the skin. J Dermatol Sci. 2018;89:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson-Huang LM, Suarez-Farinas M, Pierson KC, Fuentes-Duculan J, Cueto I, Lentini T, Sullivan-Whalen M, Gilleaudeau P, Krueger JG, Haider AS, Lowes MA. A single intradermal injection of IFN-gamma induces an inflammatory state in both non-lesional psoriatic and healthy skin. J Investig Dermatol. 2012;132:1177–1187. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giustizieri ML, Mascia F, Frezzolini A, De Pita O, Chinni LM, Giannetti A, Girolomoni G, Pastore S. Keratinocytes from patients with atopic dermatitis and psoriasis show a distinct chemokine production profile in response to T cell-derived cytokines. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:871–877. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.114707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kasi RA, Moi CS, Kien YW, Yian KR, Chin NW, Yen NK, Ponnudurai G, Fong SH. Para-phenylenediamine-induces apoptosis via a pathway dependent on PTK-Ras-Raf-JNK activation but independent of the PI3K/Akt pathway in NRK-52E cells. Mol Med Rep. 2015;11:2262–2268. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]