Abstract

Emergence of tigecycline-resistance tet(X) gene orthologues rendered tigecycline ineffective as last-resort antibiotic. To understand the potential origin and transmission mechanisms of these genes, we survey the prevalence of tet(X) and its orthologues in 2997 clinical E. coli and K. pneumoniae isolates collected nationwide in China with results showing very low prevalence on these two types of strains, 0.32% and 0%, respectively. Further surveillance of tet(X) orthologues in 3692 different clinical Gram-negative bacterial strains collected during 1994–2019 in hospitals in Zhejiang province, China reveals 106 (2.7%) tet(X)-bearing strains with Flavobacteriaceae being the dominant (97/376, 25.8%) bacteria. In addition, tet(X)s are found to be predominantly located on the chromosomes of Flavobacteriaceae and share similar GC-content as Flavobacteriaceae. It also further evolves into different orthologues and transmits among different species. Data from this work suggest that Flavobacteriaceae could be the potential ancestral source of the tigecycline resistance gene tet(X).

Subject terms: Molecular evolution, Antimicrobial resistance, Epidemiology

Emergence of tigecycline-resistance tet(X) genes is of concern. Here, the authors determine tet(X) prevalence in more than 6,000 clinical Gram-negative bacterial isolates collected between 1994 to 2019 in hospitals in China and suggest that Flavobacteriaceae could be the potential ancestral source of the tigecycline resistance genes.

Introduction

Excessive consumption of antimicrobials has resulted in rapid emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR), extensively drug-resistant (XDR) and even pandrug-resistant (PDR) bacteria, which compromised the effectiveness of treatment of infectious diseases1. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the leading causes of nosocomial infections throughout the world, were listed as the critical priority group by WHO (https://www.who.int/medicines/publications/global-priority-list-antibiotic-resistant-bacteria/en/) in terms of urgency of need for alternative antibiotics2. Treatment of severe infections caused by these bacteria were typically restricted to the last-resort antibiotics including tigecycline and colistin3. In China, tigecycline, which was launched for clinical usage in 2010, is the primary choice for treatment of serious XDR bacterial infections. This drug was more preferred than colistin, another last-line antibiotic which was recently approved for clinical application at the end of 2017 but nevertheless exhibits toxicity4. With the emergence and global spread of the plasmid-borne colistin-resistance gene mcr-1 in recent years, however, the clinical potential of colistin has been significantly compromised5. As a result, tigecycline is becoming increasingly important in treatment of infections caused by multidrug resistant organisms.

Tigecycline is a 9-t-butylglycylamido derivative of minocycline, which is the first drug of the glycylcycline class antibacterial agents6. It inhibits bacterial protein synthesis by reversibly binding to the 16S rRNA, hindering amino-acyl tRNA molecules from entering the A site of the ribosome and inhibiting elongation of peptide chains7. Chemical modification of tigecycline at the C-9 position of ring D led to enhanced binding to the target when compared to earlier classes of tetracyclines (tetracycline, doxycycline, and minocycline), and more effective evasion of common tetracycline resistance mechanisms8; tigecycline therefore exhibits broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity against MDR and XDR organisms. However, upon increasing clinical usage, tigecycline-resistant bacteria have emerged and posed a growing clinical concern9. The Tigecycline Evaluation and Surveillance Trial (TEST), which was a global antimicrobial susceptibility surveillance study, showed that between 2004 and 2013, tigecycline resistance rates in globally collected carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae (CRKP) and carbapenem-resistant E.coli (CREC) strains were 2.1% and 1.7%, respectively10. The MIC90 of A. baumannii, for which no breakpoints were available for tigecycline previously, was 2 mg L−1. 99% of E. coli strains and 91% of K. pneumoniae strains isolated from blood specimens were susceptible to tigecycline between 2012 and 2016, respectively10. The China Antimicrobial Surveillance Network (CHINET), which started monitoring tigecycline resistance in 2012, showed that the prevalence of tigecycline-resistant Klebsiella spp. slightly increased from 3.9% in 2012 to 5.4% in 2014, whereas the overall resistance rate of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella spp. to tigecycline during this period was 16.8%. Data from the China CRE Network in 2015 showed that the rate of susceptibility of carbapenem-resistant E. coli to tigecycline was higher than that of CRKP (90.9% versus 40.2%)11. The rate of resistance of Enterobacteriaceae to tigecycline was 3.0% and 3.3% in 2015 and 2016, respectively12,13.

Resistance to tigecycline is primarily due to over-expression of chromosome-encoding efflux pumps, mutations in the ribosomal binding sites and enzymatic inactivation8,14. Tet(X) is a flavin-dependent monooxygenase which is one of the most studied tigecycline-modifying enzymes8,15,16. Since identification of the tet(X) gene from the obligately anaerobic Bacteroides spp. in 2004, it has only been sporadically reported among strains of Enterobacteriaceae, Comamonadaceae, Flavobacteriaceae and Moraxellaceae17,18. To date, six orthologues of tet(X) have been reported, including tet(X) per se and tet(X1)~tet(X5), among which the plasmid-borne genes tet(X3), tet(X4), and tet(X5) were only reported recently and found to encode high-level tigecycline resistance phenotypes18–20. The emergence of plasmid-borne mobile tigecycline resistance genes recoverable from major pathogens including those of Enterobacteriaceae and Acinetobacter spp., poses serious threat to human health by compromising the antimicrobial efficacy of the last line drug tigecycline. Nevertheless, the origin, mechanism for transfer, and dissemination of the tigecycline resistance determinant tet(X), and its orthologues, remain poorly understood. In this study, we conduct a nationwide surveillance and genetic characterization of multiple genera of clinical isolates collected during the period 1994–2019 in China to fill this knowledge gap.

Results

Characterization of tet(X)-positive strains in clinical settings

To determine the prevalence of tigecycline resistance and presence of tet(X)s in clinical E. coli and K. pneumoniae strains, we screened 1547 K. pneumoniae and 1250 E. coli isolates recovered from clinical samples that were collected from 77 hospitals located in 26 provinces in China during the period 1994–2019. Four out of the 1250 E. coli strains tested (0.32%) were resistant to tigecycline and found to carry the tet(X4) gene, whereas 62 (4.0%) of the 1547 K. pneumoniae strains tested were resistant to tigecycline, but the tet(X) gene could not be detected in these strains (Table 1). All the four tet(X4)-positive E. coli strains were isolated from hospitals in Zhejiang province (Fig. 1a). To assess the prevalence of tigecycline resistance and the presence of tet(X)s in other types of Gram-negative bacteria, we conducted epidemiological study in hospitals in Zhejiang Province. We screened 3892 clinical Gram-negative bacteria belonging to Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria from different hospitals in Zhejiang Province. These bacteria include 2591 strains of Acinetobacter spp., 612 S. maltophilia strains, 376 Flavobacteriaceae strains, 136 strains of Burkholderia. spp., 108 strains of Pseudomonas spp. and 69 other Gram-negative isolates collected during the period 1994–2019 (Table 1). The rate of resistance to tigecycline varied among these strains, with Pseudomonas spp. exhibiting the highest rate (93/108, 86.11%), followed by Burkholderia. spp. (63/136, 46.32%), Flavobacteriaceae (95/376, 25.27%), S. maltophilia (43/612, 7.03%), and Acinetobacter spp. (103/2591, 3.98%). In addition, 68 Gram-negative isolates of other species were resistant to tigecycline (Table 1). These tigecycline-resistant bacteria were subjected to screening of the tet(X) orthologues, with results showing that a total of 102 (2.6%) bacterial strains carried the tet(X) orthologues. These include all 95 tigecycline-resistant Flavobacteriaceae strains, which were positive for tet(X2), one P. xiamenensis strain positive for tet(X2), one A. nosomialis strain positive for tet(X3), one Citrobacter freundii strain positive for tet(X4) and one A. baumannii strain positive for the tet(X5)-like gene, which exhibits 96.31% nucleotide identity and 95.0% amino acid identity to tet(X5)/Tet(X5) (Table 1, S1). These data indicated that all the tigecycline-resistant Flavobacteriaceae strains carried tet(X2), whereas the prevalence of tet(X)s in other Gram-negative bacteria is very low, and mostly belong to tet(X3-X5). The date at which the tet(X) orthologue was first detected in each bacterial species was summarized in Fig. 1b.

Table 1.

Overview of isolation rate and tet(X) carriage rate of clinical isolates described in this study.

| Classification of bacteria | No. of isolates | Year of isolation | Location (number of hospitals) | No. of Tigecycline resistant strains (percentage, %) | tet(X) Variants | No.of tet(X)-carrying strains (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tet(X2) | tet(X3) | tet(X4) | tet(X5) | ||||||

| Enterobacterales | |||||||||

| E. coli | 1250 | 1998–2019 | 26 Provincesa (77) | 4 (0.32) | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 (0.32) |

| Klebsiella spp. | 1547 | 1994–2019 | 26 Provinces (77) | 62 (4.00) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Citrobacter spp. | 14 | 2014–2019 | Zhejiang (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 (7.14) |

| Enterobacter spp. | 34 | 2014–2019 | Zhejiang (1) | 1 (2.94) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Serratia spp | 15 | 2014–2019 | Zhejiang (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| R. ornithinolytica | 3 | 2014–2019 | Zhejiang (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pseudomonadales | |||||||||

| Acinetobacter spp. | 2591 | 2004–2019 | Zhejiang (19), Henan (1) | 103 (3.98) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 (0.08) |

| Pseudomonas spp. | 108 | 2009–2019 | Zhejiang (1) | 93 (86.11) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (100) |

| Burkholderiales | |||||||||

| Burkholderia spp | 136 | 2004–2013 | Zhejiang (4), Sichuan (1) | 63 (46.32) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Xanthomonadales | |||||||||

| S. maltophilia | 612 | 2004–2010 | Zhejiang (6), Beijing (3), Sichuan (2), Henan (2) | 43 (7.03) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sphingobacteriales | |||||||||

| S. mizuta | 3 | 2004–2009 | Zhejiang (3) | 2 (66.67) | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (100) |

| Flavobacteriales | |||||||||

| Elizabethkingia spp. | 248 | 2004–2010 | Zhejiang (7) | 248 (100) | 46 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 46 (18.55) |

| Chryseobacterium spp. | 127 | 2004–2010 | Zhejiang (7) | 127 (100) | 48 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 48 (37.80) |

| E. falsenii | 1 | 2019 | Jilin (1) | 1 (100) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (100) |

| Total | 6689 | 1994–2019 | 26 Provinces (77) | 747 (11.17) | 99 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 106 (1.58) |

E. coli, Escherichia coli; R. ornithinolytica, Raoultella ornithinolytica; S. maltophilia, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia; S. mizuta, Sphingomonas mizutaii; E. falsenii, Empedobacte falsenii.

a26 provinces included Anhui, Beijing, Fujian, Jiangsu, Shandong, Sichuan, Gansu, Guangdong, Guizhou, Zhejiang, Hainan, Hebei, Guangxi, Henan, Hunan, Hubei, Jilin, Jiangxi, Liaoning, Xinjiang, Tianjin, Shanghai, Shaanxi, Shanxi, Yunnan, and Chongqing.

Fig. 1. Distribution of tet(X)-positive bacterial strains.

a Distribution of tet(X)-positive clinical E. coli and K. pneumoniae strains in China. Dark blue background indicates provinces included in this surveillance; red star represents the province in which tet(X)-positive strains were isolated; light blue background indicates provinces in which no sample was collected. The map was created using Edraw Max v9.4. b Year of isolation of tet(X)-positive strains of specific bacterial species. The number of strains isolated each year is indicated.

The 106 tet(X)-positive isolates were subjected to whole genome sequencing and determination of the type of antimicrobial resistance genes carried by these strains. Our data showed that each strain carried a number of antimicrobial resistance genes (ranging from 1 to 14), apart from tet(X), conferring multidrug resistance phenotypes. All the 95 tet(X2)-positive Flavobacteriaceae isolates were multidrug resistant and displayed high-level resistance to the last-line antibiotics colistin (MIC ≥ 4 mg L−1) and tigecycline (MIC ≥ 16 mg L−1), as well as ceftzaidime, aztreonam, tobramycin. They were also highly resistant other antibiotics (Table 2, Supplementary Data 1). Notably, Flavobacteriaceae isolates were barely resistant to minocycline, with the resistance rate and MIC90 being 1.05% and ≤1 mg L−1, respectively. Similarly, the resistance rate for doxycycline was 32.63% (Table 2, Supplementary Data 1).

Table 2.

Antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of non-Flavobacteriaceae tet(X)-positive isolates and the corresponding transconjugants.

| Strain | Description | tet(X) Variants | MIC of antimicrobials (mg l−1) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCC | TZP | CAZ | SFP | FEP | ATM | IPM | MEM | AMK | TM | CIP | LEV | DO | MNO | TGC | CS | SXT | |||

| EC600 | E. coli | - | 16 | ≤4 | 0.5 | ≤8 | ≤0.12 | ≤1 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.25 | ≤2 | ≤1 | ≤0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 | ≤20 |

| SM2 | S. mizutaii | tet(X2) | ≥128 | 32 | ≥64 | ≥64 | ≥32 | ≥64 | 1 | 1 | ≥64 | ≥16 | ≥4 | ≥8 | 4 | ≤1 | ≥8 | ≥16 | 160 |

| AB1 | A. baumannii | tet(X5) | ≤8 | ≤4 | 8 | ≤8 | 16 | 16 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.25 | ≤2 | 8 | ≥4 | ≥8 | ≤0.5 | ≤1 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 | 80 |

| AN1 | nosomialis | tet(X3) | ≤8 | ≥128 | ≥64 | 32 | ≥32 | ≥64 | ≤0.25 | 0.5 | ≥64 | 4 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.12 | ≤0.5 | ≤1 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 | ≥320 |

| EC2 | E. coli | tet(X4) | ≤8 | ≤4 | 0.25 | ≤8 | ≤0.12 | ≤1 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.25 | ≤2 | 8 | ≥4 | 4 | ≥16 | ≥16 | 4 | ≤0.5 | ≥320 |

| CF1 | C. freundii | tet(X4) | ≤8 | ≤4 | 0.25 | ≤8 | ≤0.12 | ≤1 | 0.5 | ≤0.25 | ≤2 | ≤1 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.12 | ≥16 | ≥16 | ≥8 | ≤0.5 | ≤20 |

| J-CF1 | Transconjugant | tet(X4) | ≤8 | ≤4 | 0.5 | ≤8 | ≤0.12 | ≤1 | 0.5 | ≤0.25 | ≤2 | ≤1 | ≤0.25 | 0.5 | ≥16 | 8 | 2 | ≤0.5 | ≤20 |

| EC3 | E. coli | tet(X4) | 16 | ≤4 | 0.25 | ≤8 | ≤0.12 | ≤1 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.25 | ≤2 | 1 | ≤0.25 | 1 | ≥16 | ≥16 | 4 | ≤0.5 | ≥320 |

| J-EC3 | Transconjugant | tet(X4) | 64 | ≤4 | 0.5 | ≤8 | ≤0.12 | ≤1 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.25 | ≤2 | ≤1 | 2 | 4 | ≥16 | ≥16 | 2 | ≤0.5 | ≥320 |

| EC4 | E. coli | tet(X4) | 16 | ≤4 | 4 | ≤8 | 1 | 16 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.25 | ≤2 | ≤1 | ≤0.25 | 1 | ≥16 | ≥16 | 4 | ≤0.5 | ≥320 |

| J-EC4 | Transconjugant | tet(X4) | ≥128 | ≤4 | ≥64 | 16 | 4 | ≥64 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.25 | ≤2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | ≥16 | ≥16 | ≥8 | ≤0.5 | ≥320 |

| EF1 | E. falsenii | tet(X2) | ≥128 | ≥128 | 32 | 16 | 2 | ≥64 | ≥16 | ≥16 | ≥64 | ≥16 | 2 | 2 | ≥16 | ≥16 | ≥8 | ≥16 | ≤20 |

| PX1 | P. xiamenensis | tet(X2) | ≤8 | 16 | 0.25 | 16 | ≤0.12 | ≤1 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.25 | ≤2 | ≤1 | ≥4 | ≥8 | ≤0.5 | ≤1 | ≤0.5 | 1 | ≥320 |

| EC1 | E. coli | tet(X4) | ≤8 | ≤4 | ≤0.12 | ≤8 | ≤0.12 | ≤1 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.25 | ≤2 | ≤1 | ≤0.25 | 1 | ≥16 | ≥16 | 4 | ≤0.5 | ≥320 |

TCC ticarcillin/clavulanic acid, TZP piperacillin/tazobactam, CAZ ceftzaidime, SFP cefoperazone/sulbactam, FEP cefepime, ATM aztreonam, IPM imipenem, MEM meropenem, AMK amikacin, TM tobramycin, CIP ciprofloxacin, LEV levofloxacin, DO doxycycline, MNO minocycline, TGC tigecycline, CS colistin, SXT trimethoprime/sulfamethoxazole.

Analysis of the resistance gene profile of Flavobacteriaceae isolates showed that resistance to carbapenems in these organisms may be due to carriage of blaB, blaCME, blaGOB, blaIND-2b, blaOXA-347, blaIND-5, and blaIND-8, resistance to macrolides (ermF), sulfonamides (sul2) and tetrcyclines (tet(36)) (Fig. 2). The P. xiamenensis isolate was found to carry the resistance genes sul1, sul2, floR, cmx, aadA2, and aac(6’)-Ib and was resistant to ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin and trimethoprime/sulfamethoxazole. The two tet(X)-positive Acinetobacter spp. isolates (A. baumannii and A.nosomialis), despite carrying the tet(X) genes, were both sensitive to tigecycline and the clinically important antibiotics colistin and carbapenems. qRT-PCR analysis indicated that tet(X) gene in both strains were expressed with ΔΔCt values (average ± standard deviation) being 490 ± 19.343 and 12.339 ± 0.337, respectively. This might be due to mutations in these two genes that rendered them inactive. The detail mechanism should be further investigated. The four E. coli isolates and one C. freundii isolate shared highly similar antimicrobial resistance profiles, and exhibited high-level resistance to tigecycline (MIC = 4 and ≥8, respectively, Table 3). Conjugation results indicated that only the tet(X3) genes carried by two E. coli isolates and one C. freundii isolate could be successfully transferred to the E. coli strain EC600. All transconjugants exhibited 4–16-folds elevation in MIC when compared to the wild type recipients (Table 3). The result suggested that the tet(X) gene carried by strains of the Flavobacteriaceae, S. mizutaii and Acinetobacter spp. could not be readily transferred to E. coli under the test condition.

Fig. 2. Heatmap of antimicrobial resistance genes in tet(X)-positive isolates in China.

The X axis represents the antimicrobial resistance gene carried by each strain. The Y axis indicates tet(X)-positive strains described in this study. Labels in the Y axis represent the species of the strain, AB Acinetobacter baumannii, AN Acinetobacter nosomialis, C Chryseobacterium sp., CB Chryseobacterium bernardetii, CF Citrobacter freundii, CI Chryseobacterium indologenes, CL Chryseobacterium lactis, EA Elizabethkingia anophelis, EC Escherichia coli, EF Empedobacter falsenii, EM Elizabethkingia meningoseptica, PX Pseudomonas xiamenensis, SM Sphingobacterium mizutaii. Red and pink colors indicate the presence and absence of the corresponding antimicrobial resistance genes, respectively.

Table 3.

Susceptibility of tet(X)-positive Flavobacteriaceae strains to commonly used antibiotics.

| Antibiotic | MIC50 (mg l−1) | MIC90 (mg l−1) | Range (mg l−1) | R% | I% | S% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCC | ≥128 | ≥128 | ≤8–≥128 | 96.84% | 0.00% | 3.16% |

| TZP | ≥128 | ≥128 | ≤4–≥128 | 96.84% | 0.00% | 3.16% |

| CAZ | ≥64 | ≥64 | 32–≥64 | 100.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| SFP | ≥64 | ≥64 | ≤8–≥64 | 71.58% | 17.89% | 10.53% |

| FEP | ≥32 | ≥32 | 2–≥32 | 94.74% | 4.21% | 1.05% |

| ATM | ≥64 | ≥64 | ≥64 | 100.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| IPM | ≥16 | ≥16 | ≤0.25–≥16 | 96.84% | 0.00% | 3.16% |

| MEM | ≥16 | ≥16 | 1–≥16 | 96.84% | 0.00% | 3.16% |

| AMK | ≥64 | ≥64 | 16–≥64 | 98.95% | 0.00% | 1.05% |

| TM | ≥16 | ≥16 | ≥16 | 100.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| CIP | ≥4 | ≥4 | 0.5–≥4 | 84.21% | 1.05% | 14.74% |

| LEV | ≥8 | ≥8 | 0.25–≥8 | 81.05% | 3.16% | 15.79% |

| DO | 8 | ≥16 | 1–≥16 | 32.63% | 26.32% | 41.05% |

| MNO | ≤1 | ≤1 | ≤1–≥16 | 1.05% | 0.00% | 98.95% |

| TGC | ≥8 | ≥8 | 4–≥8 | 100.00% | Na | 0.00% |

| CS | ≥16 | ≥16 | ≥16 | 100.00% | Na | 0.00% |

| SXT | ≥320 | ≥320 | ≤20–≥320 | 77.89% | Na | 22.11% |

TCC ticarcillin/clavulanic acid, TZP piperacillin/tazobactam, CAZ ceftzaidime, SFP cefoperazone/sulbactam, FEP cefepime, ATM aztreonam, IPM imipenem, MEM meropenem, AMK amikacin, TM tobramycin, CIP ciprofloxacin, LEV levofloxacin, DO doxycycline, MNO minocycline, TGC tigecycline, CS, colistin, SXT trimethoprime/sulfamethoxazole.

R resistant, I intermediate, S susceptible.

Na, not applicable since no intermediate value was defined for the corresponding antibiotic.

Dissemination of tet(X)-positive strains

Combined analysis of our data and that from literature enabled us to provide a comprehensive view on the current prevalence of tet(X) orthologues in different bacterial species. The tet(X) orthologous genes were detectable in two phyla, Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria, including eight families, 16 genus and 28 species (Fig. 3, Supplementary Data 2)21. Bacteroidetes is composed of three large classes, Bacteroidia, Flavobacteria and Sphingobacteria22. The tet(X) gene is commonly distributed among strains of these classes, with the chromosomal-borne tet(X) orthologues, tet(X), tet(X1), and tet(X2) being the most dominant. Plasmid-borne tet(X) genes, tet(X3), and tet(X4), were also sporadically detected among members of Bacteroidetes, mostly in strains belonging to Myroides spp., S. multivorum and E. brevis. This study revealed the high prevalence of tet(X2) in Flavobacteria, in particular among species of Chryseobacterium, Elizabethkingia and Empedobacter, as well as in Sphingobacteria. It should be noted that detection of tet(X2) in clinical isolates of Bacteroidetes is mainly reported by this study (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Taxonomy of Tet(X)-producing isolates analyzed in this and previous studies.

Asterisks (*) and (**) represent the location of the tet(X) gene in plasmid and chromosome, respectively. Text in red fonts depicts tet(X)-positive isolates tested in this study, and information of isolates with black fonts were retrieved from the literature (Supplementary Data 2). Strains isolated from different sources are shown by circles in different colors (human, red; animal, yellow; unknown, black). Year at the end of each branch denotes the year in which the first strain of the related taxonomy was isolated.

Proteobacteria isolates carrying tet(X) belonged to the two major clades of Betaproteobacteria and Gammaproteobacteria. Only two genera, Delftia and Comamonas, which belong to Betaproteobacteria, were previously reported to carry a chromosome-borne tet(X) genes (tet(X) and tet(X2)). Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonadaceae, Moraxellaceae and Morganellaceae are families of Gammaproteobacteria that carry tet(X). The dominant tet(X) orthologues reported among Gammaproteobacteria were mostly plasmid-borne genes (tet(X3)~tet(X5)), although tet(X1 and X2) were also reported in a few cases. Most of the previously reported tet(X) orthologues in Gammaproteobacteria were from animal sources, and this study has identified several tet(X) orthologues in clinical isolates of several different species (Fig. 3, Supplementary Data 2)3.

Analysis of origin and evolution trend of the TetX protein

The tet(X) gene was first discovered in anaerobic Bacteroides spp.; yet it did not confer tigecycline resistance to this host strain since the TetX protein required oxygen to transform tigecycline16. Bacteroides spp. exhibited a median GC-content of 43.5%, whereas that of the tet(X) gene was around 37%, suggesting that tet(X) did not originate from Bacteroides spp. The average chromosomal GC-content of Acinetobacter, Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas, Sphingobacterium, Flavobacteriaceae were 39%, 50%, 61%, 40%, and 37% (except Enpedobacter which is around 31.6%), respectively. The similar GC-content of Flavobacteriaceae and the tet(X) gene, the location of tet(X) genes on the chromosome among the Flavobacteriaceae strains, as well as the high carriage rate of tet(X2) by Flavobacteriaceae in this study, suggested that it could be an ancestral source of the tet(X) gene.

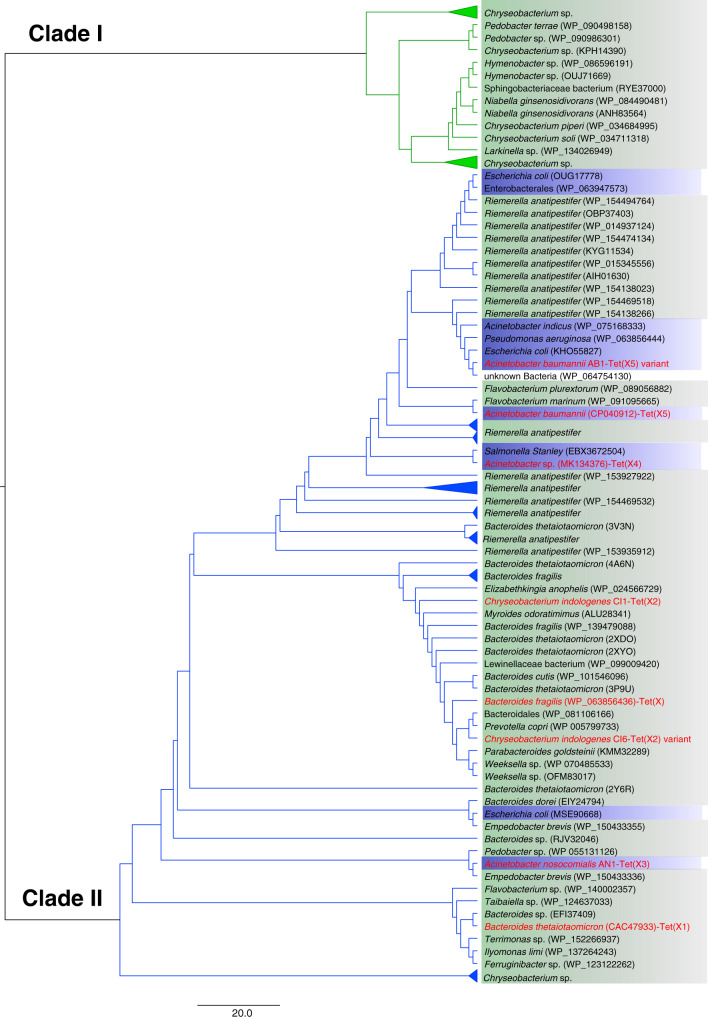

To validate our hypothesis and determine the phylogenetic profile of Tet(X), multiple sequence alignment of the Tet(X) was performed. A total of 97 Tet(X) candidate proteins that returned hits with >60% identity with the tet(X) gene per se was retrieved from the NCBI database. Intriguingly, the reconstruction of a maximum phylogeny tree allowed us to identify two distinctive clades, one (clade I) containing a total of 28 Tet(X) candidate proteins carried by Flavobacteria and Sphingobacteria, among which the Chryseobacterium sp. that belongs to the Flavobacteriaceae family was the most dominant. This clade also contained other species from Flavobacteriales (hymeobacter sp., Larkinella sp.) and species that belong to Sphingobacteriales (Pedobacter sp., Niabella sp.). The other clade (clade II) contained the published TetX orthologues (Tet(X)~Tet(X5)) harbored by isolates that belong to diverse phylogenetic groups including Flavobacteriia, Sphingobacteria, Bacteroidales and Gammaproteobacteria (Fig. 4). The phylogenetic tree depicts a divergent evolutionary pattern of Tet(X). The first clade of Tet(X) protein evolved among Flavobacteriia and Sphingobacteria and did not spread to other species. Tet(X) candidate proteins in this clade were 60%~64% identical to that of Tet(X) in terms of amino acid sequence. The other clade evolved in a more divergent manner and covered all different variants of TetX proteins reported to date. Importantly, Tet(X)/Tet(X2) proteins in this clade were able to disseminate further into members of Bacteroidales and Gammaproteobacteria. Some of the Tet(X)/Tet(X2) proteins could further evolve into other variants of Tet(X) such as Tet(X3~5), especially in Gammaproteobacteria (Fig. 4). Interestingly, we detected two variants of Tet(X2) proteins among 97 strains of Flavobacteria and both belonged to clade II of Tet(X) proteins; this finding further indicates that Tet(X2) might be the origin of other TetX variants commonly detectable in clinical settings in China (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Phylogeny of TetX generated by the maximum likelihood method.

Blue and green backgrounds denote bacteria that belong to Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes, respectively. Published (with accession numbers) and representative tet(X) orthologues are labeled with red font. The evolutionary history is depicted by using the Maximum Likelihood method and on the basis of the JTT matrix-based model. The tree with the highest log likelihood (-3778.5180) is shown. Initial tree(s) for the heuristic search were obtained automatically by applying Neighbor-Join and BioNJ algorithms to a matrix of pairwise distances estimated using a JTT model, and then selecting the topology with superior log likelihood value. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site. The analysis involved 97 amino acid sequences. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There is a total of 131 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted with MEGA7 [2].

Genetic basis of transmission of the tet(X) genes

Analysis of the tet(X) region in the Flavobacteriaceae isolates indicated that it could be located within mobilizable transposons, and carriage of multiple copies of tet(X2) by a single genome was detected in the genome of at least two Flavobacteriaceae isolates (C. bernardetii CB1 and S. mizutaii SM1). These findings indicated that tet(X) could undergo active gene transfer, especially in Bacteroides sp. isolates. The clade containing all published tet(X) orthologues comprises several separate sub-clades within the tree, suggesting the evolution routes of the tet(X) genes are highly diverse. The products generated through these evolution routes should be closely monitored.

To trace the transmission routes of tet(X), the gene environment of tet(X) in different organisms was analyzed. Genome mining indicated that the tet(X2) genes in completely sequenced Flavobacteriaceae strains were flanked by resistance genes catB and ant(6)-I, and were all located in integrative and conjugative elements (ICE) ranging from 54 to 97 Kbp in size (Fig. 5). ICE are modular mobile genetic elements integrated into a host genome and are passively propagated during chromosomal replication and cell division. Induction of ICE gene expression leads to excision and production of the conserved conjugation machinery (a type IV secretion system), which may promote genetic transfer to appropriate recipients23. The ICEs acted as a reservoir for the transmission of the tet(X) gene in Flavobacteriaceae. In Acinetobacter spp. and Enterobacteriaceae, tet(X3) and tet(X4) were typically associated with the genetic arrangements xerD-tet(X3)-res-orf1-ISVsa3 and ISVsa3-orf2-abh-tet(X4), respectively3. Direct alignment of tet(X) genetic environments in Flavobacteriaceae with that of Acinetobacter spp. and Enterobacteriaceae returned no hits. However, a 397-bp fragment composed of partial fragments of the mobile element ISVsa3 and the virD2 gene, which are uniquely detectable in members of Acinetobacter spp. and Enterobacteriaceae, was identified in the genome of two C. bernardetii strains. Such findings suggested that genetic exchange among strains of C. bernardetii and Acinetobacter spp. /Enterobacteriaceae occurred, during which the tet(X) gene could have been exchanged among strains of different species during their evolution. Of note, such genetic exchange events could occur in processes other than conjugation. For example, some of the bacteria (e.g., Acinetobacter sp.) can be naturally competent and may have scavenged DNA fragments containing tet(X) from the environment.

Fig. 5. Alignment of integrative and conjugative elements with tet(X) in Flavobacteriaceae.

Yellow arrows indicate the ORFs. Shading area between different sequences indicate the aligned regions. Location of the tet(X) gene and the region responsible for conjugative transfer are labeled. ICE sequences aligned in this figure, from top to bottom, were from tet(X)-positive strains Chryseobacterium indologenes CI6, Chryseobacterium bernardetii CB1, Chryseobacterium sp. C3, Elizabethkingia anophelis EA1, Elizabethkingia anophelis EA3, Elizabethkingia meningoseptica EM1 and Chryseobacterium lactis CL2, respectively.

To investigate the genetic basis of plasmid-borne tet(X) transmission, Nanopore and Illumina sequencing were performed to obtain the complete plasmid map. The tet(X4)-carrying plasmid in the C. freundii isolate belonged to IncN/X1type and was designated as pCF1. It was 51,531 bp in size and contained 70 ORFs, with a GC-content of 49.4%. This plasmid was found to be 99.87% identical to the 43,265 bp IncN plasmid pL2-43 (accession: KJ484641) from an E. coli isolate at 71% coverage (Supplementary Fig. 1). However, a 17 Kbp region bordered by an IS26 element carrying the tet(X4) gene in pCF1 was absent in pL2-43, suggesting that the plasmid has undergone genetic recombination and was being transferred between different species of Enterobacteriaceae (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Complete sequence of the tet(X)-bearing plasmid recovered from four E. coli strains (EC1~EC4) was determined. The plasmid from E. coli strain EC1 was an IncX1 plasmid and was designated as pEC1-tetX4. It was 49,366 bp in size, contained 63 ORFs with a GC-content of 47.6%, and was 99.90% identical to the 57,104 bp plasmid pYY76-1-2 (accession: CP040929) recovered from an E. coli isolate, at 100% coverage. The plasmid carried multiple antimicrobial resistance genes including tet(X4), tet(A), floR, aadA2, and lnu(F). The tet(X4) gene was located in the genetic environment IS26-abh-tet(X4)-ISVsa3, suggesting that it was acquired by horizontal gene transfer (Supplementary Fig. 2).

The plasmid from E. coli strain EC2 belonged to IncHI1B/HI1A/FIA and was designated as pEC2-tetX4. It was 193,021 bp in size and contained 228 ORFs, with a GC-content of 46.4%. It was 100% identical to the 190,128 bp plasmid pYPE10-190k-tetX4 (accession: CP041449), which was recovered from an E. coli isolate, at 99% coverage. The plasmid carried multiple antimicrobial resistance genes including tet(X4), floR, aadA1, blaTEM-1B, and qnrS1. The tet(X4) gene was located in the genetic environment orf1-abh-tet(X4)-ISVsa3-orf2 (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Plasmid from E. coli strain EC3 and EC4 were identical, belonged to the IncFIBk/FIA(HI1)/X1 type, and were designated as pEC3-tetX4 and pEC4-tetX4, respectively. They were 101,519 bp in length and contained 120 ORFs, with a GC-content of 49.8%. They were 99.7% identical to the 101,987 bp plasmid pYPE12-101k-tetX4 (accession: CP041443) recovered from an E. coli isolate, at 99% coverage. The plasmid carried multiple antimicrobial resistance genes including tet(X4), mef(B), sul3, floR, tet(A), qnrS1, dfrA5, blaTEM-1B, and tet(M). The tet(X4) gene was located in the genetic environment ISVsa3-abh-tet(X4)-ISVsa3-orf2 (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Discussion

Tigecycline has become a viable alternative for treating severe infections, especially for those caused by XDR bacteria8. However, tigecycline-resistant bacterial strains have continued to emerge as a result of widespread antibiotic usage, and has become a major clinical concern9. Tet(X) is a tetracycline destructase, which exhibits a unique enzymatic tetracycline inactivation mechanism8,15,16. A recent study reported the emergence of the plasmid-borne tigecycline resistance genes tet(X3)–tet(X5) in China, the products of which significantly compromised the treatment effectiveness of tigecycline3,19,20. A nationwide surveillance reported a high carriage rate of such genes among livestock3. The selective pressure imposed by the continuous application of tetracyclines in veterinary medicine could serve to maintain and spread the tet(X) genes among pathogenic microorganisms19. In clinical settings, dissemination of tet(X) orthologues clonally or via horizontal gene transfer could result in extensive colonization of tetracycline resistant organisms in human. In this study, we isolated tet(X) positive strains from hospitals located in the various provinces in China and conducted a comprehensive surveillance and molecular typing study.

According to data obtained in our surveillance, 11.17% of the test isolates exhibited tigecycline resistance, yet only 1.58% of all isolates carried tet(X)-like genes, suggesting that factors other than Tet(X) mediated the majority of tigecycline resistance in clinical settings. The over-expression of chromosomal efflux pumps of the RND family and those encoded by the plasmid-borne tmexCD1-toprJ1 gene cluster, mutations in the ribosomal binding site such as the rpsJ gene, and mutations in the plasmid-mediated efflux pump genes tet(A) and tet(L) were reported to be associated with tigecycline resistance phenotypes24–27. Factors that confer the drug susceptibility phenotypes of tigecycline-resistant bacteria remained to be investigated.

We found that the majority of tet(X)-positive strains in clinical settings in China belonged to Flavobacteriaceae. Organisms in the family Flavobacteriaceae, which is within the phylum Bacteroidetes, were first isolated by Bergey28, proposed by Jooste29 and were included in the first edition of the Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology22, in which the taxon was not formally described. The family includes the genus of Chryseobacterium, Elizabethkingia, Wautersiella, and 72 others as of 201930–35. Species in the family have been isolated from various habitats, including freshwater, marine environments, soil, glacier and other environments, and are considered opportunist human pathogens31,36,37. Notably, Elizabethkingia meningoseptica and Chryseobacterium indologene are the most common clinical species of this family. These bacteria are phenotypically similar to many of the Flavobacteriaceae and Flavobacteria-like organisms, as well as S. mizutae, which is not included in the family Flavobacteriaceae, rendering clinical identification difficult38,39. E. meningoseptica isolates may cause meningitis in premature newborns and immunocompromised patients32,40. In adults, various infection cases caused by these strains, which are often associated with a severe underlying illness such as pneumonia, endocarditis, postoperative bacteremia and meningitis, have been reported40. C. indologenes is associated with nosocomial infections and has been shown to cause a variety of invasive infections41, such as primary bacteremia, catheter-related bacteremia, ocular infection, peritonitis, biliary tract infection and ventilator-associated pneumonia42,43. Interestingly, infections caused by C. indologenes have been reported mainly in Taiwan42. The genus Sphingobacterium can be occasionally isolated from blood, cerebrospinal fluid, urine and wounds. Strains of this genus may cause bacteremia, peritonitis and chronic respiratory infections39. To date, only three cellulitis cases caused by Sphingobacterium have been reported39,44,45. The source of infection was likely environmental in these three cases, suggesting that the bacterium is an opportunistic pathogen that may cause infection in immune-compromised patients.

Strains in the family of Flavobacteriaceae are usually resistant to multiple antibiotics prescribed for treating gram-negative bacterial infections, such as aminoglycosides, β-lactams, glycopeptides, quinolones or even carbapenems, the last line of defense against multi-drug resistant organisms, and thus constitute a major clinical concern.32,41,46. Infections caused by Flavobacteriaceae can be serious and are often associated with high death rate. The treatment outcome of infections caused by strains in this family depends on three factors: severity of the infection, immune status of the patient concerned, and the drug susceptibility phenotypes of the infecting agent41,47.

The tet(X) gene was first identified in Bacteroides fragilis but it was found that the gene could not be expressed48. In 2009, Ghosh found a functional tet(X) gene in Sphingobacterium sp. strain, which was the first wild type bacterium of this species isolated49. According to result of a search of tet(X)-positive (including its variants) isolates in NCBI, the tet(X) genes have only been sporadically reported (Fig. 1). More recently, He et al. reported 77 tet(X3) or tet(X4) positive isolates from animals and human, including 51 Enterobacteriaceae, 16 Acinetobacter, four Myroides spp., two Raoultella ornithinolytica, two Empedobacter brevis, and one each of S. multivorum and Providencia rustigianii strains3. There is significant difference in detection rate of tet(X3) or tet(X4) in organisms isolated from animals and humans (6.9%, 73 out of 1,060; 0.07%, 4 out of 5485). Only four tet(X4)-positive strains have been isolated from inpatients, including one A. baumannii (Jilin, 2013) and three E. coli strains (Zhejiang, 2016–17). We screened a total of 6692 isolates collected from hospitals that belonged to 13 different genera (Table 1) and showed that almost all tet(X)-positive species belong to Flavobacteriaceae (95, 25.27%). We found this gene in only 2 Acinetobacter spp. (0.08%), 6 E. coli (0.40%), 1 B. diminuta (100%), 4 S. mizuta (100%) and 1 P. xiamenensis (100%) strain. Notably, we did not find this gene in strains of K. pneumoniae and other common Enterobacteriaceae species.

Aerobic culture of Flavobacteriaceae is known to degrade tigecycline and exhibit resistance to this drug. The chromosomal GC-content of Flavobacteriaceae strains (37%) was similar to that of the tet(X) gene. Phylogenetic analysis revealed a divergent evolutionary pattern of tet(X), among which the route involving Flavobacteriaceae generated a major clade, suggesting that it can be regarded as an ancestral source of this gene. This hypothesis is substantiated by the genetic organization and synteny of genes upstream and downstream of tet(X) in Flavobacteriaceae. The tet(X) gene is located on ICE elements, but conjugal transfer of tet(X) from Flavobacteriaceae to other bacteria using E. coli recipient was not demonstrated, suggesting that strains of Flavobacteriaceae may lack other gene functions necessary for transfer of tet(X) under our test condition. The recovery of a 397-bp Acinetobacter/Enterobacteriaceae-restricted DNA fragment in Flavobacteriaceae indicates that genetic exchange can occur among members of the phylum Proteobacteria and Bacteriodetes, and that various strains in the family of Enterobacteriaceae may acquire the tet(X) genes during this process. Despite these observations, we cannot rule out the possibility that there was a non-Flavobacteriaceae ancestor which passed the ancestral tet(X) gene to Flavobacteriaceae and Proteobacteria on occasions such as polyphyletic events.

Methods

Retrospective screening of tet(X)-carrying clinical isolates

The study comprised two phases, both of which involved analysis of clinical isolates collected from hospitals in China. The first focused on surveillance of tet(X) genes in clinical E. coli and K. pneumoniae isolates collected from 77 hospitals located in 26 provinces and municipalities in China during the period 1994 to 2019, including Anhui, Beijing, Fujian, Gansu, Guangdong, Guangxi, Guizhou, Hainan, Hebei, Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Jilin, Jiangxi, Liaoning, Jiangsu, Shandong, Shanxi, Shaanxi, Shanghai, Sichuan, Tianjing, Xinjiang, Zhejiang, Yunnan, and Chongqing. The second phase included surveillance of tet(X) genes in non-duplicated clinical strains of different Gram-positive bacterial species including Flavobacteriaceae, Acinetobacter. spp., Burkholderia. spp., Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, P. aeruginosa and other Gram-negative bacteria collected from seven hospitals located in Zhejiang Province. All isolates were collected as part of an active surveillance process conducted in China. Ethical permission for this study was given by the Zhejiang University ethics committee with the reference No. 2019-074. All strains were subjected to species confirmation using 16S rRNA gene-based sequencing and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization/time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) (Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Bremen, Germany). All isolates were subjected to screening of tet(X) orthologues by PCR and Sanger sequencing according to methods published previously3. All primers used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Antimicrobial susceptibility tests and transconjugation

The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of tet(X)-positive strains against 15 commonly used antibiotics (imipenem, meropenem, ceftzaidime, cefepime, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, doxycycline, minocycline, tigecycline, tobramycin, colistin, ticarcillin/clavulanic acid, piperacillin/tazobactam, cefoperazone/sulbactam, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole) were determined by the VITEK 2 COMPACT automatic microbiology analyzer, and interpreted according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines, except tigecycline and colistin50, the breakpoints of which were interpreted according to the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST)51.

The efficiency of plasmid conjugation between 27 tet(X)-carrying strains and the E.coli strain EC600 was tested using the mixed broth method52. These strains included 17 randomly selected Flavobacteriaceae strains (5 C. indologenes, 3 E. meningoseptica, 3 E. anophelis, 2 C. bernardetii, 1 C. lactis, 2 Chryseobacterium sp., 1 E. falsenii), as well as strains of E. coli (3), C. freundii (1), S. mizuta (3), Acinetobacter spp. (2), A.nosomialis (1), A. baumannii (1), and P. xiamenensis (1). Transconjugants were selected on LB agar plates supplemented with 1 μg mL−1 tigecycline and 600 μg ml−1 rifampicin. PCR was conducted to confirm the presence of tet(X) genes; MALDI-TOF MS was applied to confirm the species identity of the transconjugants. MIC of the transconjugants was tested using the aforementioned method.

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was conducted to test whether tet(X) genes in the two Acinetobacter spp. strains susceptible to tigecycline were expressed. Briefly, total RNA was extracted using the QIAGEN RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Extracted RNA was treated with Invitrogen TURBO DNA-free Kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA), followed by reverse transcription using the Invitrogen SuperScript™ III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). qRT-PCR was conducted in a Light Cycler 480 (Roche Diagnostics), using primers in Supplementary Table 153. All reactions were performed in triplicate. The 16S rRNA gene of Acinetobacter spp. were amplified with previously published primers and used as endogeneous reference genes54. A. baumannii ATCC 19606 with a tigecycline MIC of 0.5 μg mL−1 was used as the reference strain. Relative expression levels of the tet(X) genes were obtained by the ΔΔCT analysis method.

Whole-genome sequencing and bioinformatics analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from overnight cultures by using the PureLink Genomic DNA Mini Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). All isolates carrying the tet(X) genes were subjected to whole genome sequencing using the HiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Genome assembly was conducted with SPAdes v3.12.055. Oxford nanopore MinION sequencing was conducted to obtain the complete genome sequences of strains carrying the tet(X) gene, using the SQK-RBK004 sequencing kit and flowcell R9.556. Hybrid assembly of Illumina and nanopore sequencing reads was constructed using Unicycler v 0.3.057. Genome sequences were annotated using RAST v2.0 with manual editing58. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) of all Enterobacteriaceae isolates was conducted using MLST v2.1159. Acquired antibiotic resistance genes were identified by ResFinder 2.160. Heatmap of antimicrobial resistance genes was plotted using Genesis v1.7.761. Plasmid replicons were analyzed using PlasmidFinder 2.162. Insertion sequences (ISs) were identified using ISfinder v2.063. The genetic location of the tet(X) gene was determined by aligning the contigs carrying tet(X) with complete genome sequences in the NCBI database and those generated in this study. 16S rRNA genes of all isolates were obtained using Barrnap v0.964. Integrative and conjugative elements were predicted using ICEberg265. GC-content of all genome assemblies were calculated using CLC Genomics Workbench v9 (Qiagen, CA, USA).

Prevalence of tet(X) orthologues in Gram-negative bacteria

We searched PubMed with no language restriction for articles that contained the terms tet(X), tet(X) and tigecycline resistance, tigecycline resistance gene to retrieve information on previously published tet(X)-positive isolates, including isolation source, year of isolation and location of the tet(X) genes. These isolates were classified according to Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology35. Information of tet(X)-positive strains both from previous studies and this study were plotted to create a classification figure using Adobe Illustrator v22.1.

Sequence acquisition and alignment of TetX

To identify sequence homologous to tet(X) and its orthologues, a BLASTp v.2.10.0 search was performed using the amino acid sequences of TetX to TetX5 as query sequences. In order to avoid BLAST hits from very closely related species, uncultured environmental samples were excluded from the search and the max target sequences acquired were 100. The top unique protein sequences were selected and submitted to the Guidance2 server to evaluate the quality of the alignment and identify potential regions and sequences that reduce the quality of alignment66. Multiple sequence alignment was performed using MUSCLE v3.8.31 with default parameters67. A model with the least score (JTT + I) evaluated using the Models function in MEGA 7 was selected as the best amino acid substitution model to reconstruct the Maximum-Likehood tree. Gaps and missing data were treated as partial deletions. Results were validated using 1000 bootstrap replicates68.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81861138052, 81871705, 31761133004, and 81772250).

Author contributions

R.Z., N.D., Z.S., G.C., and S.C. designed the study. R.Z., Y.Z., J.L., C.L., H.Z., Y.H., Q.S., Q.C., L.S., and J.C. collected the strains, conducted the screening experiment, bacteria characterization and literature review. S.C., R.Z., N.D., E.W.C.C., and G.C. analyzed and interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed, revised, and approved the final report.

Data availability

The whole genome sequencing data of all strains in this study have been submitted to the NCBI database under the BioProject accession number PRJNA595705. The 16S rRNA gene sequences of all strains in this study have been deposited in the NCBI GenBank database under accession numbers MT793124-MT793229.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Sanjana Mukherjee and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Rong Zhang, Ning Dong, Zhangqi Shen.

Contributor Information

Gongxiang Chen, Email: chengongxiang@zju.edu.cn.

Sheng Chen, Email: shechen@cityu.edu.hk.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-020-18475-9.

References

- 1.Magiorakos AP, et al. Multidrug‐resistant, extensively drug‐resistant and pandrug‐resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:268–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Guidelines for the Prevention and Control of Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, Acinetobacter Baumannii and Pseudomonas Aeruginosa In Health Care Facilities. (2017). [PubMed]

- 3.He T, et al. Emergence of plasmid-mediated high-level tigecycline resistance genes in animals and humans. Nat. Microbiol. 2019;4:1450–1456. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0445-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foschi C, et al. Ease-of-use protocol for the rapid detection of third-generation cephalosporin resistance in Enterobacteriaceae isolated from blood cultures using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time-of-flight mass spectrometry. J. Hosp. Infect. 2016;93:206–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2016.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu Y-Y, et al. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016;16:161–168. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00424-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karageorgopoulos DE, Kelesidis T, Kelesidis I, Falagas ME. Tigecycline for the treatment of multidrug-resistant (including carbapenem-resistant) Acinetobacter infections: a review of the scientific evidence. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2008;62:45–55. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhanel GG, et al. Review of eravacycline, a novel fluorocycline antibacterial agent. Drugs. 2016;76:567–588. doi: 10.1007/s40265-016-0545-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Linkevicius M, Sandegren L, Andersson DI. Potential of tetracycline resistance proteins to evolve tigecycline resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016;60:789–796. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02465-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaewpoowat Q, Ostrosky-Zeichner L. Tigecycline: a critical safety review. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2015;14:335–342. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2015.997206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoban DJ, Reinert RR, Bouchillon SK, Dowzicky MJ. Global in vitro activity of tigecycline and comparator agents: tigecycline evaluation and surveillance trial 2004–2013. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2015;14:27. doi: 10.1186/s12941-015-0085-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Y, et al. Epidemiology of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections: report from the China CRE network. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018;62:e01882–17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01882-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fupin Hu EA. CHINET surveillance of bacterial resistance across China:report of the results in 2015. Chin. J. Infect. Chemother. 2016;16:10. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fupin Hu EA. CHINET surveillance of bacterial resistance across China:report of the results in 2016. Chin. J. Infect. Chemother. 2017;17:11. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun Y, et al. The emergence of clinical resistance to tigecycline. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2013;41:110–116. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moore IF, Hughes DW, Wright GD. Tigecycline is modified by the flavin-dependent monooxygenase TetX. Biochemistry. 2005;44:11829–11835. doi: 10.1021/bi0506066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang W, et al. TetX is a flavin-dependent monooxygenase conferring resistance to tetracycline antibiotics. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:52346–52352. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409573200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walkiewicz K, Davlieva M, Wu G, Shamoo Y. Crystal structure of Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron TetX2, a tetracycline degrading monooxygenase at 2.8 Å resolution. Proteins. 2011;79:2335. doi: 10.1002/prot.23052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leski TA, et al. Multidrug-resistant tet (X)-containing hospital isolates in Sierra Leone. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2013;42:83–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2013.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun, J. et al. Plasmid-encoded tet (X) genes that confer high-level tigecycline resistance in Escherichia coli. Nat. Microbiol.4, 1457–1464 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Wang, L. et al. Novel plasmid-mediated tet (X5) gene conferring resistance to tigecycline, eravacycline and omadacycline in clinical Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 64, 01326–01319 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Speer B, Bedzyk L, Salyers A. Evidence that a novel tetracycline resistance gene found on two Bacteroides transposons encodes an NADP-requiring oxidoreductase. J. Bacteriol. 1991;173:176–183. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.1.176-183.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boone, D., Castenholz, R., Garrity, G. & Bergey, D. J. B. M. O. S. B. Bergey’s Manual® of Systematic Bacteriology. Vol. 38, 89–100 (Williams & Wilkins, MD, Baltimore, 1984).

- 23.Johnson CM, Grossman AD. Integrative and conjugative elements (ICEs): what they do and how they work. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2015;49:577–601. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-112414-055018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.SK C, et al. Roles of ramR and tet(A) mutations in conferring tigecycline resistance in Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017;61:e00391–17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00391-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.M L, L S, DI A. Mechanisms and fitness costs of tigecycline resistance in Escherichia coli. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2013;68:2809–2819. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lv, L. et al. Emergence of a plasmid-encoded resistance-nodulation-division efflux pump conferring resistance to multiple drugs, including tigecycline, in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Mbio11, e02930-19 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Y Z, et al. Emergence of an Empedobacter falsenii strain harbouring a tet(X)-variant-bearing novel plasmid conferring resistance to tigecycline. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020;75:531–536. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkz489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weeks OB. Flavobacterium aquatile (Frankland and Frankland) Bergey et al., type species of the genus Flavobacterium. J. Bacteriol. 1955;69:649–658. doi: 10.1128/jb.69.6.649-658.1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jooste PJ, Britz TJ, De Haast J. A numerical taxonomic study of Flavobacterium-Cytophaga strains from dairy sources. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1985;59:311–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1985.tb03325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van der Velden LB, de Jong AS, de Jong H, de Gier RP, Rentenaar RJ. First report of a Wautersiella falsenii isolated from the urine of an infant with pyelonephritis. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2012;74:404–405. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang RG, et al. Description of Chishuiella changwenlii gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from freshwater, and transfer of Wautersiella falsenii to the genus Empedobacter as Empedobacter falsenii comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014;64:2723–2728. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.063115-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ceyhan M, Celik M. Elizabethkingia meningosepticum (Chryseobacterium meningosepticum) Infections in Children. Int J. Pediatr. 2011;2011:215237. doi: 10.1155/2011/215237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu L, et al. Sphingobacterium alkalisoli sp. nov., isolated from a saline-alkaline soil. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2017;67:1943–1948. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.001895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bernardet JF. Proposed minimal standards for describing new taxa of the family Flavobacteriaceae and emended description of the family. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2002;52:1049–1070. doi: 10.1099/00207713-52-3-1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krieg, N. R. et al. Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. (Springer-Verlag, New York, 2010).

- 36.Ao L, et al. Flavobacterium arsenatis sp. nov., a novel arsenic-resistant bacterium from high-arsenic sediment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014;64:3369–3374. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.063248-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Y, et al. Flavobacterium collinsense sp. nov., isolated from a till sample of an Antarctic glacier. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016;66:172–177. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.000688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vandamme P, Bernardet JF, Segers P, Kersters K, Holmes B. NOTES: new perspectives in the classification of the Flavobacteria: Description of Chryseobacterium gen. nov., Bergeyella gen. nov., and Empedobacter nom. rev. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1994;44:827–831. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tronel H, Plesiat P, Ageron E, Grimont PAD. Bacteremia caused by a novel species of Sphingobacterium. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2003;9:1242–1244. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2003.00801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin PY, et al. Clinical and microbiological analysis of bloodstream infections caused by Chryseobacterium meningosepticum in nonneonatal patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004;42:3353–3355. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.7.3353-3355.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bellais S, Poirel L, Leotard S, Naas T, Nordmann P. Genetic diversity of carbapenem-hydrolyzing metallo-beta-lactamases from Chryseobacterium (Flavobacterium) indologenes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000;44:3028–3034. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.11.3028-3034.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin Y-T, et al. Clinical and microbiological characteristics of Chryseobacterium indologenes Bacteremia. J. Microbiol. Immunol. 2010;43:498–505. doi: 10.1016/S1684-1182(10)60077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peñasco Y, Duerto J, González-Castro A, Domínguez MJ, Rodríguez-Borregán JC. Ventilator-associated pneumonia due to Chryseobacterium indologenes. Med. Intensiv. 2016;40:66–67. doi: 10.1016/j.medin.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marinella MA. Cellulitis and sepsis due to sphingobacterium. JAMA. 2002;288:1985. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.16.1985-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huys G, et al. Sphingobacterium cellulitidis sp. nov., isolated from clinical and environmental sources. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2017;67:1415–1421. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.001832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen GX, Zhang R, Zhou HW. Heterogeneity of metallo-beta-lactamases in clinical isolates of Chryseobacterium meningosepticum from Hangzhou, China. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006;57:750–752. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kyritsi MA, Mouchtouri VA, Pournaras S, Hadjichristodoulou C. First reported isolation of an emerging opportunistic pathogen (Elizabethkingia anophelis) from hospital water systems in Greece. J. Water Health. 2018;16:164–170. doi: 10.2166/wh.2017.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guiney DG, Hasegawa P, Davis CE. Expression in Escherichia coli of cryptic tetracycline resistance genes from bacteroides R plasmids. Plasmid. 1984;11:248–252. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(84)90031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ghosh S, Sadowsky MJ, Roberts MC, Gralnick JA, LaPara TM. Sphingobacterium sp. strain PM2-P1-29 harbours a functional tet(X) gene encoding for the degradation of tetracycline. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2009;106:1336–1342. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.04101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.In, C. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute by Wayne, PA (2018).

- 51.European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Clinical Breakpoints and Dosing of antibiotics. (2019).

- 52.Borgia S, et al. Outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae containing bla NDM-1, Ontario, Canada. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012;55:e109–e117. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li Y, Shen Z, Ding S, Wang S. A TaqMan-based multiplex real-time PCR assay for the rapid detection of tigecycline resistance genes from bacteria, faeces and environmental samples. BMC Microbiol. 2020;20:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12866-020-01813-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Higgins PG, Wisplinghoff H, Stefanik D, Seifert H. Selection of topoisomerase mutations and overexpression of adeB mRNA transcripts during an outbreak of Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2004;54:821–823. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bankevich A, et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012;19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li, R. et al. Efficient generation of complete sequences of MDR-encoding plasmids by rapid assembly of MinION barcoding sequencing data. Gigascience7, gix132 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Wick RR, Judd LM, Gorrie CL, Holt KE. Unicycler: resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017;13:e1005595. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Overbeek R, et al. The SEED and the Rapid Annotation of microbial genomes using Subsystems Technology (RAST) Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;42:D206–D214. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Seemann, T. mlst.https://github.com/tseemann/mlst (2019).

- 60.Zankari E, et al. Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012;67:2640–2644. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sturn A, Quackenbush J, Trajanoski Z. Genesis: cluster analysis of microarray data. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:207–208. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.1.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Carattoli A, et al. In silico detection and typing of plasmids using PlasmidFinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014;58:3895–3903. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02412-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Siguier P, Pérochon J, Lestrade L, Mahillon J, Chandler M. ISfinder: the reference centre for bacterial insertion sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D32–D36. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Seemann, T. https://github.com/tseemann/barrnap (Github, 2015).

- 65.Liu M, et al. ICEberg 2.0: an updated database of bacterial integrative and conjugative elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;47:D660–D665. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sela I, Ashkenazy H, Katoh K, Pupko T. GUIDANCE2: accurate detection of unreliable alignment regions accounting for the uncertainty of multiple parameters. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W7–W14. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinform. 2004;5:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The whole genome sequencing data of all strains in this study have been submitted to the NCBI database under the BioProject accession number PRJNA595705. The 16S rRNA gene sequences of all strains in this study have been deposited in the NCBI GenBank database under accession numbers MT793124-MT793229.