Abstract

Objective:

The purpose of this study is to explore the evidence surrounding educational videos for patients and family caregivers in hospice and palliative care. We ask three research questions: 1.What is the evidence for video interventions? 2.What is the quality of the evidence behind video interventions? 3.What are the outcomes of video interventions?

Methods:

The study is a systematic review, following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines. Researchers systematically searched five databases for experimental and observational studies on the evidence supporting video education for hospice and palliative care patients and caregivers, published in 1969–2019.

Results:

The review identified 31 relevant articles with moderate-high quality of evidence. Most studies were experimental (74%), came from the United States (84%) and had a mean sample size of 139 participants. Studies showed that video interventions positively affect preferences of care and advance care planning, provide emotional support, and serve as decision and information aids.

Conclusion:

A strong body of evidence has emerged for video education interventions in hospice and palliative care. Additional research assessing video interventions’ impact on clinical outcomes is needed.

Practice Implications:

Videos are a promising tool for patient and family education in hospice and palliative care.

Keywords: Hospice and palliative medicine, video, audiovisual aid, education, systematic review, intervention, patient, caregiver, carer

INTRODUCTION

A serious illness carries a high risk of morbidity and mortality, and negatively impacts a person’s daily function, quality of life and increases burden for their family caregivers (1). Poor quality of communication between patients and providers may limit patients’ knowledge of prognosis, management of symptoms, and treatments options consistent with their preferences (2). Palliative care professionals work closely with patients and their family caregivers to ensure that goals of care are understood and symptoms are relieved. Video technology is one tool that is increasingly utilized to facilitate education for those living with serious illnesses (3). Videos can provide visual information and illustrate complex medical and emotional scenarios (4). However, the clinical outcomes of video education, especially in hospice and palliative care, have been understudied. Video education is of specific interested because it can improve communication barriers as a result in end-of-life (EOL) care, low health literacy and diverse learning styles and cultures.

Previous systematic reviews of video interventions have explored education about cancer (3), EOL communication (5) and shared-decision making (2, 6). In contrast, this review focuses specifically on videos as educational tools for family caregivers and patients enrolled in hospice and palliative care. The aims of this systematic review are: 1. To explore the evidence for video interventions. 2. To examine the quality of the evidence behind video-education interventions 3. To determine the outcomes of video-education interventions.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines directed the protocol for this systematic review. PRISMA is an internationally accepted approach on the conduct, evaluation, and reporting of randomized trials and intervention evaluations (7). To examine the quantitative and qualitative studies (research type and design) investigating adult patients and caregivers (sample) experience and outcomes (evaluation) of video education (phenomenon of interest) while receiving hospice and palliative care following the SPIDER search tool (8).

Video education is defined as viewing of audiovisual recorded material (that demonstrates or explains a topic using a video format) individually (with or without face-to-face trainer) or in-group as part of live session where a video was a key component of educational content. Palliative care is defined as the care provided to improve the quality of life for patients and their families living with life-threatening illness. Hospice care is a type of palliative care to provide comfort at end-of-life or when prognosis is 6 months or less.

The evidence supporting video education for patients and caregivers receiving hospice and palliative care was found using the following databases: PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Embase and Cochrane. With the assistance of a health sciences librarian, each database was evaluated to find the adequate Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) in order to search the following research keywords related to ‘palliative care’, ‘end-of-life’, ‘hospice’, ‘patient education’, ‘instruction’, ‘communication’, ‘video’, ‘videotape recording’, and ‘audiovisual aid’ (Further details available as supplementary material). No additional restrictions or filters were used in the search of each database. EndNote (9) and Covidence (10) were used to manage the references of the initial collection of titles and abstracts related of all five databases.

The inclusion criteria included video intervention studies in English of adult hospice and/or palliative care patients and caregivers/carers/surrogates, published in peer-reviewed journals between January 1, 1969 and June 7, 2019. To address aims #1 and #2 we included both quantitative and qualitative studies. Interventions studies were included to address aim #3 and seek the types of outcomes explored with video education. Pediatric patients and caregivers were excluded because their educational needs and health literacy are unique from the adult palliative care population. Also excluded from this review were all types of literature reviews, published comments, editorials, dissertations, conference proceedings, case reports, non-hospice or palliative care studies; studies that did not have an educational intent, non-intervention studies, studies focused on educating healthcare providers, including, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) simulation studies.

After the initial identification of articles, paper abstracts were reviewed by two authors (DMCO & APR) to ensure they met the inclusion criteria. The same two authors independently read all papers and extracted study information in a Microsoft Office Excel spreadsheet regarding study type (quantitative, qualitative or mixed), research question, aims, study design, setting, sample size, intervention, main outcome, results, quality of articles and themes. Extracted data were compared between the researchers and disagreement was resolved by consensus.

Different quality scoring criteria were used for quantitative and qualitative studies. The methodological rigor of each study was assessed using a modified scoring format from Parker-Oliver, et al (11). The scoring rubric is outlined in Table 2. For quantitative studies, higher scores represent higher scientific rigor in data collection, analysis, and reporting processes. Scores could range from 0 to 22, depending on the presence of certain elements influencing the methodological rigor. Scores were ranked into three categories: low 0–7, moderate 8–15 and high quality 16–22. Similarly, the qualitative studies were scored and a higher score reflects a higher degree of methodological rigor, analysis, and reporting process. Scores could range from 0–11 with higher scores assigned to increased methodological rigor. Scores were categorized by thirds, low 0–3, moderate 4–7 and high quality 8–11.

Table 2.

Scoring and Risk Bias Analysis

| Primary Author (Date) | Quality of Methodology | Risk of Bias | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | Mean Total | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Qualitative Studies | |||||||||||||||

| Alakson, et al (2019) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 11 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Chung, et al. (2016) | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Cruz-Oliver, et al.(2018) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 11 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| mDeep, et al. (2010) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 11 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Epstein, et al (2015) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 10 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Leow and Chan (2016) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 11 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Pensak, et al. (2017) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 11 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Thomas, et al. (2015) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 8 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Mean Qualitative Score | 9.6 | ||||||||||||||

| Possible score 0 – 11 | |||||||||||||||

| Quantitative Studies | |||||||||||||||

| Alakson, et al.(2019) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 22 | Low | Low | Low |

| Brown, et al. (1999) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 16 | Unclear | Unclear | Low |

| Capewell, et al.(2010) | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | N/A | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Cohen, et al. (2018) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 20 | Low | Low | Low |

| Cruz-Oliver, et al.(2016) | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 10 | N/A | N/A | Low |

| El-Jawahri, et al.(2010) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 20 | Low | High | Low |

| El-Jawahri, et al.(2016) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 19 | Low | High | Low |

| Epstein, et al. (2013) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 19 | High | High | Low |

| Gallagher-Thompson, et al.(2010) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 17 | Low | Unclear | Low |

| Gant, et al. (2007) | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 13 | Unclear | Unclear | Low |

| Hanson, et al. (2017) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 22 | Low | Low | Low |

| Kozlov, et al. (2017) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | N/A | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 16 | Low | Unclear | Low |

| Lambing, et al.(2006) | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | N/A | 1 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 11 | N/A | N/A | Low |

| Matsui (2010) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 11 | High | Unclear | Low |

| McIlvennan, et al.(2018) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 16 | Unclear | Unclear | Low |

| Schofield, et al.(2007) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | N/A | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 12 | Unclear | Unclear | Low |

| Steffen (2000) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 17 | Unclear | High | Low |

| Steffen and Gant (2015) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 20 | Low | Low | Low |

| Toraya (2014) | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | N/A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | N/A | N/A | Low |

| Volandes, et al.(2008) | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | N/A | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | N/A | N/A | Low |

| Volandes, et al.(2008) | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | N/A | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 10 | N/A | N/A | Low |

| Volandes, et al.(2009) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | N/A | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 14 | Low | High | Low |

| Volandes, et al.(2011) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | N/A | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 16 | Low | High | Low |

| Volandes, et al.(2012) | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | N/A | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | N/A | N/A | Low |

| Mean Quantitative Score | 14.79 | ||||||||||||||

| Possible score 0–22 | |||||||||||||||

Rigor Scoring – Qualitative:1) Is there a clear connection to an existing body of knowledge/Theoretical framework? 2) Are research methods appropriate to the question being asked? 3) Is the description of context for the study clear and sufficiently detailed? 4) I s the description of method clear and sufficiently detailed to be replicated? 5) Is there an adequate description of the sampling strategy? 6) Is the method of data analysis appropriate and justified? 7) Are procedures for data analysis clearly described and in sufficient detail? 8) Is there evidence that the data analysis involved more than one researcher? 9) Are the participants adequately described? 10) Are the findings presented in an accessible and easy-to-follow manner? 11) Is sufficient original evidence provided to support the relationship between interpretation and evidence?

Rigor Scoring-Quantitative: 1) Aims and outcomes 2) Sample formation 3) Inclusion/exclusion criteria 4) Subjects described 5) Power of study calculated 6) Outcome measures 7) Follow-ups 8) Analysis 9) Baseline differences between groups 10) Unit of allocation to intervention 11) Randomization/method of allocation of subjects.

Risk bias 1) Blinding of participants and personnel 2) Blinding of outcome assessment 3) Incomplete outcome data. N/A= does not apply.

The final component of the methodological rigor involved evaluation of bias of quantitative studies. Using the Cochrane Collaboration ‘Risk of bias’ assessment tool (12), 4 items were evaluated: blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) and researcher bias. The evaluation of allocation concealment and random sequence generation is included among the elements of methodological rigor for quantitative studies (items #10 & 11). To minimize bias in the scoring of each article, initial data extraction and scoring was done independently by the first two authors. Inter-rater agreement was achieved as differences in scores were discussed and consensus was reached on the final scoring. An analysis table was built outlining the individual sores from each study, and the table was reviewed and discussed by all authors.

RESULTS

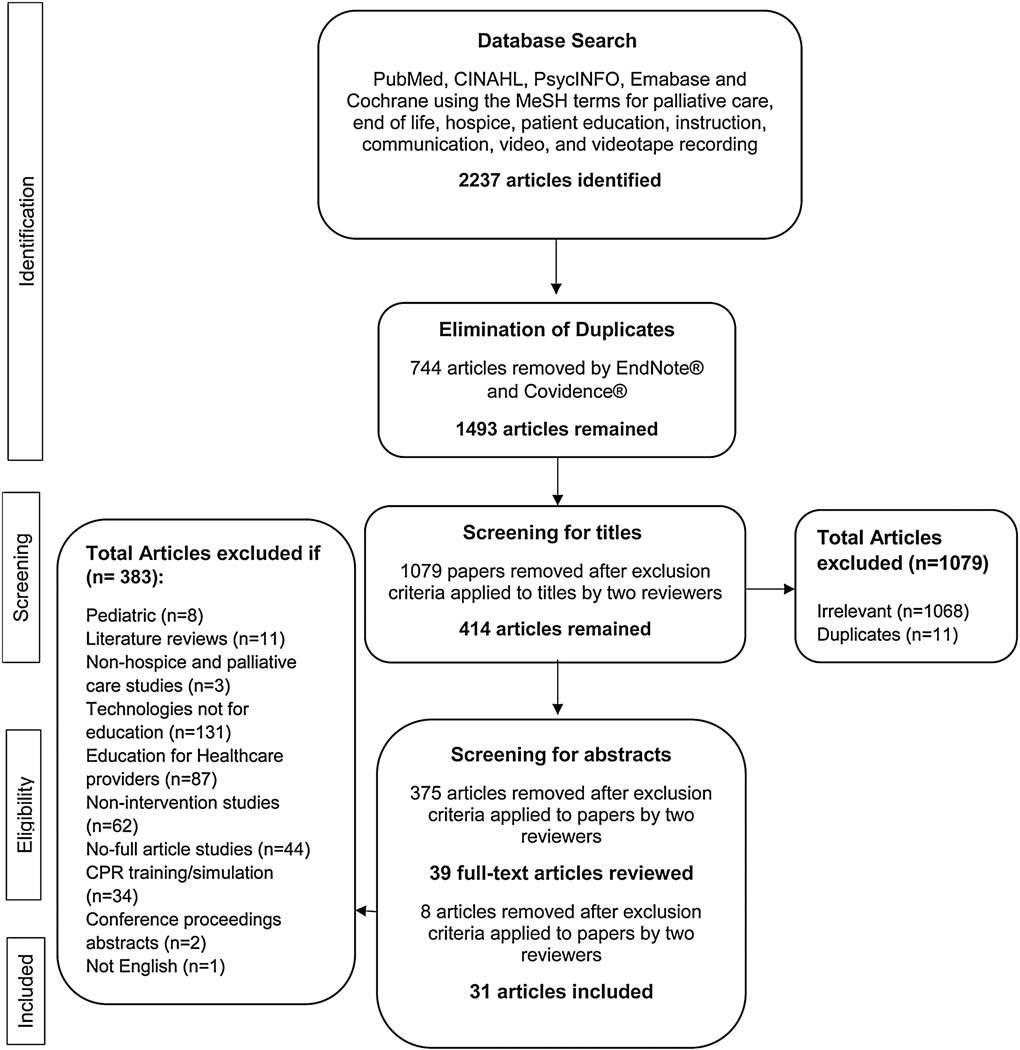

The initial search identified 2237 papers from the five databases. After the elimination of duplicates and irrelevant titles, the sample was slimmed to 414 abstracts. Abstracts were then reviewed for adherence to the inclusion criteria and the sample was shortened to 39 articles. Finally, the full articles were reviewed, and the inclusion criteria were applied, resulting in a final sample of 31 unduplicated, peer-reviewed, empirically based studies published between January 1999 and May 2019. See Figure 1 for a PRISMA flow diagram.

FIGURE 1. PRISMA flowchart.

Methodological rigor was evaluated for each study and is summarized in Table 3. More than three quarters (78%) of the studies used quantitative methodologies. One study was a multiple methods study and both quantitative and qualitative methodologies were evaluated separately (13). Studies were predominately randomized clinical trials (48%). In reviewing individual components of the quality of scoring, there was lack of power calculation (45%), selection bias because of inappropriate allocation concealment (23%) and inexplicit randomization method (19%). This reflects the majority of pilot/feasibility RCT studies included, where power calculation is not appropriate and allocation concealment is not always possible. The criteria for follow up (element #7) were difficult to score, because studies did not report this information or it was not applicable. The means score for quantitative studies was 14.79, representing moderate strength of evidence. Eight studies used qualitative methodology. The mean score of the qualitative evidence was 9.6, representing high strength of evidence. The 31 studies were published in 22 unique journals, indicating no journal bias. The sample involved 17 teams of authors. One research team published 39% of the articles resulting in potential researcher bias. As author of two of the studies in the review, we recognize the potential for bias in the assessment of evidence of our work. Thus, we have collaborated with two additional authors for independent study assessment and consensus (11). All articles had low risk for attrition bias.

Table 3.

Summary of Selected Papers

| Reference | Aims | Theory | Study Design | Setting | Sample Size (N) | Intervention | Outcome measures and results | Theme | Video Content, duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aslaks on, et al. (2019) (13) | To evaluate if ACP videos could be integrated into surgical care and if patients would engage in perioperative ACP discussions after the intervention | None | RCT with recorded interviews | Single-center, Tertiary care, Academic Hospital-Across US | 92 patients undergoing major cancer surgery I= 45 C= 47 | I: ACP video featuring a patient and her family undergoing preoperative and postoperative issues C: Informational video about surgery program | No difference in discussion of ACP content nor in patient-centeredness between groups HADS remained stable Participants categorized video as helpful 41% (vs. 39%) | Effect on preference and ACP | Patient and family discussing preparing for, undergoing and recovering from major surgery and recommen ding ACP 6-minutes |

| Brown, et al. (1999) (14) | To assess if the addition of video tape would stimulate ACP completion more than written materials alone | Communication theory: Video increases knowledge allowing informed consent. | RCT | Community dwelling – in Colora do | 1247 patients randomized I = 619 C = 638 | I: Peace of Mind videotape + Written-materials C: Written-materials only | ACP completion after 3 months 34% of study population had at least one ACP, compared with 20% at baseline. No difference found between the groups. | Effect on preference and ACP | 9 interviews of patients and families describing their feelings and choices about ACP unknown |

| Capewell, et al. (2010) (38) | To determine the feasibility of evaluating a DVD based educational intervention among cancer patients | System theory: Barriers to cancer pain include patient, professional and HC system levels. | Prospective | Community dwelling – in United Kingdom | 15 patients and 10 caregivers | Baseline (V1): 6-min DVD-based educational video with researcher. Participants received a takehome DVD copy and leaflet. At 5–10 days (V2): Second visit/questi onnaire At 25–35 days (V3): Third visit/questionnaire | Patient pain questionnaire (PPQ) Reduction of 18% between V1 and the final assessment V2 or V3 (p=0.007) No significant improvements between V2 and V3(p= 0.067) Brief pain inventory (BPI) Reduction of 9.6% between V1 and V2 (p=0.0 2) Hospital anxiety/Depression Scale (HAD) No significant changes Family Pain questionnaire (FPQ) Knowledge subscale improved by 42% between V1 and V3. | Information aid | Multi-disciplinary palliative care staff talking about cancer pain and opioid use 6-minutes |

| Chung et al. (2016) (39) | To find a development strategy for a culturally credible video with emphasis on Hispanic hospice patients | Communication theory: Communication between patient and provider is best method to deliver information to Latinos. Video can help clinicians communicate with Latinos. | Focus group | Comnunity dwelling - Hospice - in California | 78 Latino caregivers: Phase 2 = 47 Phase 3 = 12 | I: Video about a patient with Alzheimer’s disease, her family caregivers and healthcare providers | Video’s educational effectiveness, strength and weaknesses Phase 2: Request for more powerful shots that facilitate virtual engagement and for additional information about hospice enrollment. Phase 3: Caregivers stated that video will increase awareness of hospice availability | Satisfaction and acceptance of video | Latino family’s personal testimonial of caring for Mexican-American with late stage Alzheimer Dementia and bilingual interdisciplinary hospice team member stories about hospice <10-minutes |

| Cohen, et al. (2018) (15) | To understand the relationship of proxy level of care preferences and documented ACP in the EVINCE cohort; To evaluate how does ACP video improve concordance between care preferences and patterns of advance directives | Self-efficacy theory | Cluster RCT | Multi-center, Nursing home facilities - in Boston | 328 resident-proxydyads I= 172 C=156 | I: description + 12- minutes video on tablet showed to proxy C: Description of three levels of care options | Concordance between proxy level of care preferences and ACP documented in residents charts When proxies stated intensive care preference, 58% of residents’ charts were deemed to be concordant with that preference; When comfort care was preferred, residents in the intervention arm were more likely to have directives concordant with preference compared to control (AOR= 2.48, CI 1.01-6.09) | Effect on preference and ACP | Visual images of the 3-part goals of care choices in advance dementia: life prolonging care in the ICU with simulated resuscitation, basic medical care in medical ward, and comfort care on home hospice 12-minutes |

| Cruz-Oliver, et al. (2016) (35) | To assess the effectiveness of educating Latinos using telenovel as about CG stress and improve their attitudes towards using EOL care | None | Pre-posttest survey to CGs | Community dwelling - Across US | 145 caregivers | Audiovisual Intervention using telenovela and Power Point presentation | Knowledge and Attitudes Post-video higher awareness of CG stress and were more willing to accept help from hospice, social work, adult day care and chore worker. 6-month post-intervention survey/follow-up 91% said they most probably intended to use these services | Informtion aid | Bilingual telenovela about a caregiver struggling to care for her father with dementia and how healthcare providers help her keep patient at home 15-minutes |

| Cruz-Oliver, et al. (2018) (36) | To identify the motives of CGs to participat e in educatio nal intervent ion and to evaluate their learning outcome | None | Pre-posttest survey to CGs | Community dwelling - Across US | 145 caregivers | Telenovela and Power Point presentation | Pretest 2-open ended questions about expected learning Most (75%) expected to learn how to help the sick Post-test learning assessment Participants left the training with better understanding about how to accept help (45%) and the services available (46%) | Information aid | Bilingual telenovela about a caregiver struggling to care for her father with dementia and how healthcare providers help her keep patient at home 15-minutes |

| Deep, et al. (2010) (16) | To determine if the video images of a patient with advanced dementia impact informed decisions about future care. | Self-efficacy theory: Video communication leads to increased knowledge and self-efficacy. | Cross - sectional structured interviews | Outpatient clinic - in Boston | 120 patients | I: A 2-minute documentary video of a patient with advanced dementia C: Verbal description | Post-video reasons for change in choice of care: Medical care inherently good, avoid suffering, Inadequate QOL, Not become a burden to family, futile treatment, preserve life Post-video change in preference of care 18/25 change d from life-prolon ging to comfort; 16/22 changed from limited to comfort t; 3 themes on the impact of the video: Value of the visual as oppose d to words, imparti ng knowle dge about experie nce & emotio nal reactio n to video. | Effect on preference and ACP | Two daughters talking to the patient with dementia 2-minutes |

| El-Jawahri, et al. (2010) (17) | To determine the preference of care of cancer patients after a video intervention | Communie ation theory: These interventions maybe difficult for patients to imaging using verbal description alone. Video images have been shown to improve understanding of complex health info and inform decision-making. | RCT | Oncology elinie - in Boston | 50 glioma patients I= 23 C= 27 | I: 6-min video plus verbal narrative C: Verbal narrative | GOC preference of care assessment 91% of participants in the video group preferred comfort (life-preserving 0%, basic 4%, and uncertain 4%) | Effect on preference and ACP | Visual images of the 3-part goals of care framework in advance cancer: life prolonging care in the ICU with simulated resuscitation, basic medical care in medical ward, and comfort care on home hospice 6-minutes |

| El-Jawahri, et al. (2016) (18) | To assess the effectiveness of a video-assisted intervention compared to a verbal description in patients choosing comfort care | Communication theory: Video-assisted approach was designed to stimulate and supplement the conversation with clinicians. Patients can be empowered to engage clinicians in ACP, strengthening discussions with providers. | RCT | Single-Center Aeade mie Hospital - Aeross US | 246 patients > 64 yrs old: I = 123 C = 123 | I: Verbal Narrative plus 6-minute GOC video for patients with advanced heart failure C: Verbal Description only Control arm | GOC preferences 51% participants in the video intervention preferred comfort care, to forgo CPR/Intubation and had higher ACP knowledge Follow up conversation At 3 month, 61% (vs. 15% in control) had GOC conversation with health care provider | Effect on preference and ACP | Doctor introduces ACP and 3-part goals of care framework, followed by simulated code with clinicians conducting CPR and intubation 6-minutes |

| Epstein, et al. (2015) (19) | To assess the impressions of a CPR educational video for cancer patients | Communication theory | Interview of participants in a RCT | Outpatient oncology clinic - in New York | 54 patients I= 29 C= 25 | I: Educational 3-minutes video about CPR C: Narrative description | Answers to open-ended question about post-intervention concerns Advance care planning should be started early, information about the process of CPR affirmed values, participants were apprehensive about ACP but wanted to discuss it, gaps in medical knowledge emerged, CPR information was helpful/accept able, physicians should be involve d in ACP. While sometimes difficult to discuss, ACP was deemed a helpful and desired process. They believed that the process ideally should be begin early, involve clinicians, and that video educati on is an appropriate and affirming conversation starter. | Effect on preference and ACP | Visual images of the 3-part goals of care framework in advance cancer: life prolonging care in the ICU with simulated resuscitation, basic medical care in medical ward, and comfort care on home hospice 3-minutes |

| Epstein, et al. (2013) (20) | To compare the effect of a video intervention versus a narrative description to enhance the completion of ACP and documented discussio n about desired EOL care | Communication theory | RCT | Single-center, Out-patient oncology clinic - in New York | 57 cancer patients I= 30 C= 26 | I: Short 3-min CPR and mechanical ventilation video C: Narrative description of CPR - script identical to the one heard in the video | ACP completion 40% (12/30) of patients in the video arm completed ACP vs. 15% (4/26) in narrative arm (p=.07) Preferences for CPR changed significantly in the video arm (p=.02 3) and not in the narrative arm | Effect on preference and ACP | Visual images of the 3-part goals of care framework in advance cancer: life prolonging care in the ICU with simulated resuscitation, basic medical care in medical ward, and comfort care on home hospice 3-minutes |

| Gallagher-Thompson, et al. (2010) (27) | To determine if a Skill-DVD compared to Educational-DVD about dementia patients would be effective in reducing depressive symptoms & stress related to CG (CES-D & pos affect) of Chinese dementia patients | Self-efficacy theory: Build skills and self-efficacy to improve outcomes | RCT | Community dwelling - Across US | 76 caregivers: I = 40 C=36 | I: Skill training DVD intervention (SKDVD) C: Education DVD intervention (EDDVD) | CES-D decreased depressive symptoms in both groups post video Positive Affect subscale score increased significantly in skill-DVD (p=0.0 01) RMBPC Stress/negative reaction toward patient behavior decreased more in the skill-DVD group (p=0.0 19) | Emotional support | Narrator explains information about dementia, caregiver stress, how to communicate and access resources in Mandarin 2.5 hours |

| Gant, et al. (2007) (26) | To determine the efficacy of video intervention in reducing psychosocial distress in male caregivers | None | RCT of male caregivers | Community dwelling - Urban Midwest | 32 male caregivers: I =17 C =15 | I: Video/Workbook/telephone coaching C: 37-page booklet Basic Dementia Care Guide + biweekly phone calls | RMBPC Significant reduction in caregiver upset and annoyance across both the booklet/check-in calls and the video/coaching intervention Video intervention greater efficacy not demonstrated Self-efficacy Scale, Positive/negative emotions Greater efficacy of video intervention not demonstrated | Emotional support | Unknown specific content, but it was based on Dementia Caregiving Skills Program Unknown |

| Hanson, et al. (2017) (33) | To verify if GOC video intervention can improve communication and decision making as well as acceptance to palliative care for advance dementia patients and family decision makers | None | Cluster RCT | Community dwelling - nursing home - in North Carolina | I = 151 dyads C = 151 dyads | I: Family decision makers had two-part intervention consisting of an 18-min. Goals of Care (GOC) video plus a discussion with the nursing home care team. C: Informational video and Usual care plan | Quality of communication score Improv ed End-of-life communication (QOC) scores compar ed to control at 3 months and at end of the study Concordance with clinicians GOC Greater concor dance with providers ACP problem score No difference in ACP problem score Quality of Palliative Care Hospital transfer and survival time did not differ significantly | Decision aid | On dementia, goals of prolonging life, supporting function, or improving comfort, and how to prioritize goals 18-minutes |

| Kozlov, et al. (2017) (37) | To evaluate if laypersons’ knowledge about palliative care improve with brief, self-administrated educational intervention compared to written page | Communication theory: Patient knowledge of health services drives utilization Patients are not able to make fully informed treatment decisions when they are unaware of all the care options available. | RCT | Multi-Center both Acade mic & Community Hospitals - in Missouri | 152 laypersons I = 77 C = 76 | I1: Video Intervention about palliative care C1: Information page intervention I2: Diet video C2: Information page control | Palliative care Knowledge Scale & Mean confidence ratings (PaCKs) No significant difference was found in the knowledge scores and confidence in knowledge between the video-intervention and the information-intervention groups. | Information aid | Doctor giving information about palliative care, scenes of doctor interacting with patients 3-minutes |

| Lambing, et al. (2006) (43) | To evaluate how can seriously ill patients that received a CD-ROM intervent ion feel with the educational program | Self-efficacy theory | Prospective pilot | Single-center Academic Hospital - in Michig an | 50 patients diagnosed with life- limiting illness | Pre-intervention questionnaire, ‘Completin g a Life’ CD-ROM, Post-intervention questionnaire | Comfort level with information provided 90% somewhat comfor table using CD ROM 98% found it easy to use | Satisfaction and acceptance of video | Information in taking charge, finding comfort, reaching closure and personal stories of patients with terminal illness 1 hour |

| Leow and Chan (2016) (42) | To evaluate the perception of CGs of advanced cancer patients after receiving a video intervention, having telephone follow-ups and participating in online forum | Communieation theory | Semi-struetured face-to-face interviews | Single-center Home Hospice - in Singap ore | 12 caregivers of patients with advanced cancer | I: 6-week psychoeducational intervention ‘Caring for the CG’ program that includes: 1 23-min video, 2-Telephone follow-up 3-Online social support | 2 open ended questions about perception and most/least useful component Most (10/12) participants found it most useful; Most particip ants said they ‘identify with the scenes in the video’ relating to the frustrations the CG in the video was experiencing | Satisfaction and acceptance of video | Unknown specific content, but it is based on Caring for the Caregiver Program psychoeducational intervention 23-minutes |

| Matsui (2010) (21) | To find the preference of care of Japanese older adults after an educational program | None | Quasi-experimental | Community dwelling - in Japan | 121 adults (>65 years old) | I: 90-min educational program consisting of a lecture, video about EOL care in hospice and discussion C: Handouts | Post-video life sustaining treatment preferences Regarding artificial nutrition changed from 46% to 25% in the category “leave it to physicians” Attitudes about Advanced Directives Positive attitudes about Advanced Directives increased 1 month post-video from 43% to 52% (p=.02 4) Acceptability Program acceptance was higher in the intervention group (8.6 vs. 7.5, p=.011 ) 1-mo post video discussion with physician about preferences of care 49% (from 29%)stated that they would not prefer artificial nutrition and this remained 1 month follow-up (p<.010) | Effect on preference and ACP | The video introduced public preferences for life sustaining treatment, actual EOL care in a hospice at home and in the NH and living wills produce by the Japan Society for Dying with Dignity 90-minutes |

| McIlvennan, et al. (2018) (32) | To determine if a DT-LVAD could be effective in improving shared decision making for caregivers | Communication theory | Stepped-wedge RCT | Multi-Center both Academic & Comm unity Hospitals - Across US | 182 caregivers I=71 C=111 | I: 1-Delivery of an in-person 2.5h clinician-directed decision support training of local staff; 2-Integration of 26-min video and 8-page pamphlet about decision aids C: Formal industry pamphlets, videos and program-specific LVAD documents | Decision Quality-Knowledge no change in quality - knowledge between groups Values-choice concordance At 1-month concordance between values and treatment choice was higher in the intervention group (p=0.0 26) but not at 6mo (p=0.0 8) | Decision aid | Decision Aid for patients and their caregivers considering DT-LVAD 26-minutes |

| Pensak, et al. (2017) (40) | To determine the acceptability, anticipated usability and feasibility of Pep-Pal = a mobilized adapated version of PEPRR=Psycho-Educational, Paced Respiration and Relaxation Program | Self-efficacy theory | Focus groups and individual interviews | Single-center, Academic Hospital - in Colora do | Focus group= 6 Interview= 9 | Focus group of Step 2 with 6 CGs: Pep-Pal 10-min mock-up video Interview of Step 2 with 9 CGs: Pep-pal videos | Focus group quotes based on 5 outcomes: Majority preferred combination of animated and human delivery, suggested to include more positive examples, could use video in the waiting room, include breathing exercises, and that a website will be great. Interviews subthemes: Distractions, validating the CG experience, combination of 1:1 support, no difficulty, an acceptable way to get support prognosis introduction early on diagnosis | Satisfaction and acceptance of video | Introduction to stress management, mind-body connection, how our thoughts can lead to stress, strategies for maintaining energy and stamina, comping with uncertainty, managing relations and coping with your needs, getting the support you need, and improving intimacy. 9 videos of 10-minutes each |

| Schofie, et al. (2007) (29) | To assess the effect of this DVD on cancer patients’ pretreatment anxiety, informational needs and self-efficacy | None | Quasi-experimental | Single-center, Oncology clinic – in Australia | 100 patients with cancer (>18 years old) | I: Take-home DVD about receiving chemother apy and self-management of common side effects C: Usual care | Satisfaction Intervention group more satisfied (p=0.0 26) HADS No significant difference between the usual care and the intervention groups Self-perceived palliative vs. Self-perceived curative patients Curative patients rated themselves as more confident maintaining activity / independence, stress management, accepting cancer/maintaining positive attitude affective regulation and seeking social support | Emotional support | Focused on preparation for receiving chemotherapy and self-management of eight common side effects 25-minutes |

| Steffen (2000) (28) | To evaluate the usefulnes s of a CG anger-management intervention ingroup or at home | Self-efficacy theory | RCT | Community-dwelling - in Boston | 33 caregivers of dementia patients I1= 10 I2= 9 C= 9 | I1: 1-Home-based viewing of an anger-management video segments for the next 8 weeks and a workbook plus 20- min weekly telephone checks I2: Class-based meeting with a trained facilitator C: Wait-list participants | Anger intensity anger scores for the two intervention conditions were each significantly lower than in the posttre atment Wait-list group (p<.01) BDI Mean BDI for the home-based viewin g condition was significantly different than waitlist (p<.01) | Emotional support | Narrator present specific components, brief interviews with caregiver and an enacted role-play of assertion skills 4 hours |

| Steffen and Gant (2015) (30) | To evaluate the effect of a basic education/telephone support condition vs. video instruction/telephone support condition on reducing negative behaviors, depression, and negative moods | None | RCT - single blind | Community dwelling – Across US | 74 caregivers I=33 C=41 | I: Video instruction/workbook/telephone behavioral coaching C: Basic education/telephone support | RMBPC Behavioral upset significantly reduced with medium effect at 10 weeks, but at 6-months post intervention remain similar between both groups BDI-II Greater efficacy of the behavioral coaching in reducing depressive symptoms (p<0.0 5) Negative mood Lower level of negativ e mood and anxiety in the behavioral coaching group | Emotional support | Narrator explains behavioral activation, management of disruptive dementia behaviors, relaxation during caregiving and self-efficacy 5 hours |

| Thomas, et al. (2015) (41) | The determine how a multimedia DVD for CGs meet informational needs and provide peer support | Self-efficacy theory | Focus group and interviews with caregivers | Community dwelling – in Australia | 29 caregivers | CGs received a DVD multimedia sent by mail and a questionnaire to complete. | Rating scale on helpfulness, on satisfaction and how well they related to media CGs stated they were satisfied, that the DVD was a positive tool (realistic, informative, interesting, inspiring) to introduced palliative care to caregivers CGs related well with the film | Satisfaction and accept ance of video | Interview about self-care, social support, palliative care, EOL discussions and bereavement. Unknown |

| Toraya (2014) (22) | To assess if an educational AD video is effective in increasing patient understanding regarding discussion of future HC wishes and AD documents | Communication theory: communication is an important part of ACP and videos facilitate communication. | Pre-post survey | Single-center community Hospital outpatient clinic – in Washington | 45 participants from outpatient clinics | I: 12-minute video to encourage discussion about Advanced Directives | Changes in future HC wishes 58% said video changed their HC wishes Rating of the video helpfulness Mean rank of video helpful ness was 8.8 (0–10) | Effect on preference and ACP | Video encourages discussions about future healthcare wishes and ACP 12-minutes |

| Volandes, et al. (2008) (23) | To assess the influence of Health Literacy as opposed to race in EOL care preferences after video intervention | Communication theory: Health literacy is barrier to communication and educational video can assist | Cross sectional questionnaire | Outpatient clinic - Urban and Suburb an Boston | 144 participants/patients AA=80 W=64 | I: Verbal description followed by 2-min video of a patient with dementia. Participant s were evaluated on their health Literacy | Tool used to measure health literacy of each participants Preferences of care after hearing verbal description 67% of low health literacy participants preferred aggressive care HL remained significant and independent predictor of preferences for care (OR 7.1, 95 0 CI 2.1-24.2) Comparison with preferences of care after video Majority of subjects across both races and all health literacy groups chose comfort care after viewing the video. The distribution of subject’s preferences changed significantly (p=0.0001). | Effect on preference and ACP | Narrator describes the salient features of advanced dementia. 2-minutes |

| Volandes, et al. (2008) (25) | To determine if patients’ preferences for EOL care can be independently predicted by educational level after hearing verbal description of advance dementia To evaluate a video decision aid about advance dementia effect on communication barriers posed by limited educational level | Communication theory | Cross sectional - questionnaire | Outpatient clinic - in Boston | 104 Latino patients | I: Verbal description about preferences of care followed by 2-min video of a patient with dementia | Preferences of care Pre/post video intervention Before video 40% preferred comfort care and after the video 75% preferred comfor t care After watching the video differences by education disappeared | Effect on preference and ACP | Narrator describes the salient features of advanced dementia. 2-minutes |

| Volandes, et al. (2009) (31) | To assess if patients & surrogates that viewed a video decision-support tool for advance dementia concur more about EOL preferences compared to those receiving a verbal description | Communication theory: The video engages and allows both patients/surrogates to envision future health states in a manner not captured with verbal communication. | RCT | Single-Center Community Hospital - in Boston | 14 patient-surrogate dyads: I= 8 dyads C=6 dyads | I: Verbal narrative plus viewing a 2-minute video decision-support tool C: Verbal narrative of advanced dementia | Surrogates preferences for their loved one There was 100% concordance of surrogates and patients preferences Knowledge scores for dyad Increased for both groups, but higher in the intervention | Decision aid | Two daughters talking to the patient with dementia 2-minutes |

| Volandes, et al. (2011) (34) | To evaluate if rural patients would be more likely to prefer comfort care after a video decision aid | Communication theory-Video can communicate informatio n to support decision making | RCT | Outpatient clinic - Rural Louisiana | 77 advanced dementia patients I=33 C=43 | I: Verbal narrative followed by a Video decision aid C: Verbal description only | Difference in proportions of subjects preferring comfort care between the groups 91% in the video group vs. 72% in the verbal description group (p=.04 7) Factors associated with preference for comfort care white, female, video arm and higher HL (P<.05) | Decision aid | Two daughters talking to female patient with advance dementia and visual images of the 3-part goals of care framework : life prolonging care in the ICU with simulated resuscitation, basic medical care in medical ward, and comfort care on home hospice 6-minutes |

| Volandes, et al. (2012) (24) | To assess the effect of reinforcing verbal description with video in order to improve knowledge about CPR; To determine if there is a difference on stated preferences after watching the video | Communication theory | Cross sectional | Oncology clinic - in New York | 80 patients with advanced cancer | I: Verbal description followed by 6-min video describing 3 choices of HC (life-prolonging, basic, comfort care) | Pre/post: Preference of Care After verbal description, 36% preferred comfort care Did not change significantly after viewing the video CPR/ventilator preferences CPR/v entilator preferences changed significantly (61% pre, 71% post video, p=0.03) | Effect on preference and ACP | Visual images of the 3-part goals of care choices of health care in advance cancer: life prolonging care in the ICU with simulated resuscitation, basic medical care in medical ward, and comfort care on home hospice 6-minutes |

RTC = Randomized Controlled Trial, I = Intervention, C = Control, CG = caregiver, CES-D = Center for Epidemiological studies Depression Scale, RMBPC=revised memory and behavior problems checklist, GOC = Goals of care, HAD= Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, PPQ= Patient Pain Questionnaire, BPI= Brief Pain Inventory, QOL = Quality of Life, AA= African Americans, W= Whites, REALM= Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine tool, HL= Health Literacy, HC= Healthcare, CG= caregiver, BDI-II= Beck Depression Inventory over the past two weeks, LVAD= Left Ventricular Assist Device, ACP= Advanced Care Planning, EOL= End-of-life, ACP= Advance Care Planning, US= United States

Most of the studies were experimental (74%). Research was international with samples from United Kingdom, Australia, Japan, Singapore, and most (84%) came from the United States. The mean sample size of all studies was 139 participants, with a range of 12–1302 participants, including 644 caregiver-patient dyads. Most studies (77%) compared another educational method with the video intervention. The remaining studies (23%) used a pre-post analysis approach without a comparator. Three theories were identified, including communication, self-efficacy and system theory, as authors’ conceptual approach for their use of videos. Table 4 identifies and summarizes the articles in the sample.

Table 4.

Themes of Video Education

| Definition of themes |

| 1) Effect on preference and ACP: videos’ ability to influence preferences and ACP |

| 2) Emotional support: videos’ ability to influence emotion and mood |

| 3) Decision aid: videos’ ability to influence decisions with decision aid |

| 4) Information aid: videos’ ability to influence education with information aid |

| 5) Satisfaction and acceptance of video: outcomes related with satisfaction with video |

ACP=Advance care planning

There were five basic categories of video-education intervention studies. First, there were those designed to impact patient and family preferences for care and ACP, including the completion of advanced care plans. Second were studies designed to assess video interventions’ impact on emotions, including those with an effect on patient/family mood. Third were studies evaluating the impact of the video on decision-making. Fourth were studies of video interventions serving as informational aids with the goal of impacting knowledge. Finally, there were video intervention studies focused on satisfaction and acceptance of the video intervention itself. See table 4 for themes definitions.

The most common theme of the video interventions was preferences of care and ACP (13–25). Generally, the videos changed participants’ preferences toward comfort care (21), eliminating the differences by participants’ educational (25) and health literacy level (23). Three of these studies found that, while ACP completion rate increased following video education, it was not significantly different to other educational means, such as written information (14), and ACP discussion did not change (13). However, ACP completion rate was higher with videos as compared to verbal narrative intervention (20). Qualitative data revealed that after watching videos study participants changed to preferences to comfort only in an effort to avoid suffering, become a burden, or experience futile treatment (16).

Video interventions with the goal of providing or improving emotion (26–30) included four studies with an effect on mood (26–28) including caregiver depression (28, 30). Two video interventions were noted to successfully improve caregiver reaction to patient dementia-related behaviors (27); however, the effect did not last 6 months post-intervention (30).

The effectiveness of videos as a decision aid was the focus of four studies (31–34). Three articles reported on findings that demonstrated video education resulted in greater concordance between clinicians’ goals-of-care (GOC) and proxies’ (33) as well as concordance between patients’ preferences and their proxies (31, 32).

The effectiveness of videos as an information aid was demonstrated in two pre-posttest studies (35, 36) but not in a randomized clinical trial (37). Prospectively, after video education about cancer pain, patient pain scores improved within 1.5 weeks, but this effect did not last 35 days post-video; however, family pain knowledge improved (38). Qualitative data showed that after watching the video participants had a better understanding about how to accept professional help and caregiver support services available (36).

Five studies found overall satisfaction and acceptance of video education. Study results noted that participants expressed high levels of satisfaction, helpfulness and comfort (39–43). Specifically, three articles provide detailed description of video development (39–41) where participants identified with video content (41), preferred positive examples, found videos to be an acceptable way to get support (40) and showed an increased awareness of hospice and palliative care (39).

A wide array of clinical outcomes was tested. Nearly one-third of the outcomes measured patient choice of treatment (32%). Another third looked at patient and caregiver physical/psychological wellness, including pain, anxiety, depression and self-efficacy (29%). Finally, the last type of outcome involved advance care planning (ACP) completion or discussion (13%). Subjective measures included satisfaction with the video intervention, helpfulness of video and attitude change. Most video content consisted of stories/documentaries (48%) with non-cancer patients (84%) and were delivered in-person (68%) with an average duration of 37 minutes.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Discussion

The aim of this study was to review the evidence regarding the use of videos for education of patients and family caregivers in hospice and palliative care. The overall evidence is of moderate-high quality. Generally, the evidence supports the use of video education in hospice and palliative care as the studies showed positive impact on care preferences and advance care planning (ACP), emotions, decision-making, and knowledge. Additionally, video education participants expressed satisfaction and acceptance of video technology.

There were some challenging biases in the research. Researcher bias was present with a significant portion of the evidence coming from one research team. Another source of bias was the lack of blinding of participants and allocation concealment. Additionally, many studies did not report a power calculation or their randomization method. Many of these biases were due to the inherent limitation of the use of a pre-post intervention study design with no control group. The sensitive nature of conducting research on seriously ill patients poses both ethical and logistical challenges that require researchers to develop innovative techniques that do not always conform to the scientific gold standard of the double-blind, randomized controlled trial or the use of usual care comparator (5).

Efforts to bring healthcare into accord with seriously ill patients’ wishes through use of advance directives and Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) orders have had limited success, in part because meaningful options are often offered too late and preferences are rarely documented in medical record (5, 44). The ACP process, albeit difficult, is a helpful desired process that should occur early in the disease process (19). Numerous studies demonstrated the efficacy of video as a decision support tool in ACP (5) and treatment choices (2). Similarly, in our study the evidence supporting the effectiveness of video-education intervention on changing care preferences and ACP is strong.

Palliative care patients and their caregivers experience complex medical care options resulting in high emotional distress as they choose between potentially life-prolonging treatments with side effects and comfort-focused care with less aggressive treatments. The evidence reviewed here suggests that decision aids help patients and caregivers communicate more effectively and participate in a shared decision-making process with healthcare professionals (6). This included content about treatment goals for advanced dementia, role of the surrogate decision maker, and the three levels of medical care (life-prolonging care, basic medical care, and comfort care). One concern sometimes cited regarding video decision aids for cancer patients is that the images and stories, particularly regarding disease progression or prognosis, may have a negative effect on patient or caregiver mood. This concern was not supported by the review, as numerous studies found no increase in patients’ anxiety after receiving video education (13, 29, 38). Another group (3) reported similar findings when using technologies for cancer patient education, noting that interventions did not significantly influence anxiety when diagnosis and treatment were discussed, especially when interventions were carried out with the assistance of a healthcare provider (3).

Interventions using video as a decision support tool in hospice and palliative care should begin to include the use of more stories that include caregivers’ perspective and experience in the ACP process for higher identification of participants with video content. Austin et al. (2) reports that decision tools improve patient preparation for treatment choices, including ACP, palliative care and goals-of-care communication, feeding options in dementia, lung transplant in cystic fibrosis and truth telling in terminal cancer. Most of these studies provided evidence of an effect on clinical outcomes, changes in ACP documentation, clinical decision-making and treatment received (2). Because the effect of knowledge is well established, future research needs to focus on outcomes measuring the effect of the change in knowledge on treatment decisions, health care intensity and cost (2).

When assessing videos’ effect on patient/caregiver knowledge, there was one article that reported negative results in knowledge about palliative care (37), while others showed positive effects in participant’s attitudes toward EOL care services (35, 36). On the contrary, various studies reported significant impact in knowledge among interventions that used video as information aids (6). The evidence showed that educational technology was effective and, in some cases, slightly superior to traditional educational methods (3). Videos have the capability of engaging audiences by combining different types of media. This prevents the patient from being distracted from the message by extraneous details, as tends to happen in verbal communication, and provide information that may be especially suitable for patients who are nonnative speakers of English and for those with low literacy levels (3). Although more than two thirds of videos were delivered in-person, many studies did not explore whether the content provided in the video interventions was effectively delivered (i.e. viewing time) and evaluated using validated learning measurements (6). Moreover, despite these studies claiming to be educational interventions, none explicitly described the pedagogy or learning approach on which the materials were based.

This study has several notable limitations. This review was limited to articles published in the English language and therefore, it may have missed significant research and trends taking place in other languages. Some studies used convenience samples and followed a pre-post intervention design and the nature of interventions designed to improve these outcomes often results in a non-blinded study design that hinders methodological rigor. Additionally, the widely heterogeneous outcomes measured in this sample made comparison of effectiveness impossible. To minimize the limitations, we have used a systematic process for identification of evidence, a defined standardized assessment based on previous reviews in related fields, as well as a two-pronged approach to assess both rigor and risk bias.

Conclusion

Recent calls for the reprioritization of patient education, as an essential element in patients’ management, require standardized tools to ensure that the education is effective. Thus, the evaluation of video interventions for different patient groups in a variety of circumstances is important. This review of the evidence found that videos achieved improvement in choice of treatment, goals-of-care discussion, decision-making and change in caregiver attitudes and mood. For the most part, videos were well accepted, and patients were more satisfied with information and decision-making process. To ensure that video education is used effectively to optimize care, it is essential that research continues to build on the existing evidence base and test new techniques for implementing and delivering quality education for hospice and palliative care patients and their caregivers.

Practice implications

While the role of videos in hospice and palliative care shows significant promise, their use should be one of many different modes of education between the patient, family caregiver and healthcare providers. The use of video is a rich and potentially important area that can expand beyond its use for healthcare interventions, namely, for video-conferencing or telehealth with distributed family caregivers, distance learning, and as important component of website resources (i.e. like: www.healthtalk.org) to foster credible patient/caregiver information. If hospices and palliative care programs are to invest in video technology, then the evidence needs strengthening. Given the limited resources of hospice and palliative programs, a focus on patient-based outcomes is critical. In this sense, it is imperative to start with the proper use of video development processes that is well described in various studies (39–41).

Future interventions should continue to take advantage of the mobile, connected, health information and communication technologies. The proven value of video in helping patients clarify their treatment preferences should encourage more providers to experiment this medium; however, research is needed to help providers determine when face-to face video delivery is necessary, and when remote video delivery will achieve comparable results. For example, nurses have higher recognition of the need for Internet guidance and may play a more active role in referring to and discussing content of educational videos (45). Further, it is unknown the time of exposure to video education interventions that is needed to achieve psychological or behavioral changes. We did not find evidence or justification for the dosage or frequency of interventions for patients/caregivers across studies. Moreover, is imperative to determine what type of video intervention is most effective within specific patient/caregiver populations based on disease trajectories; when is the appropriate time (before, during or after palliative consultation) and mode (in-person, mail, online) of delivery; and investigate psychological and behavioral outcomes in both patient and caregiver groups to optimize their quality of care.

Supplementary Material

Table 1.

Methodological Rigor Scoring

| Articles are scored with a methodology score from EITHER Part A or Part B | |

| A. Quantitative scoring | |

| 1. Aims/outcome (observational and experimental) | |

| a. Defined at outset | 2 |

| b. Implied in paper | 1 |

| c. Unclear | 0 |

| 2. Sample formation (observational and experimental) | |

| a. Random | 2 |

| b. Quasi-random; sequential series in given setting or total available | 1 |

| c. Selected, historical, other, insufficient information | 0 |

| 3. Inclusion/exclusion criteria (observational and experimental) | |

| a. Explicitly described | 2 |

| b. Implied by patient characteristics, setting | 1 |

| c. Unclear | 0 |

| 4. Subjects described (observational and experimental) | |

| a. Full information | 2 |

| b. Partial information | 1 |

| c. No information | 0 |

| 5. Power of study calculated (observational and experimental) | |

| a. Yes | 2 |

| b. No | 0 |

| 6. Outcome measures (observational and experimental) | |

| a. Objective | 2 |

| b. Subjective | 1 |

| c. Not explicit | 0 |

| 7. Follow-up (observational and experimental) | |

| a. > 80% of subjects available for follow-up | 2 |

| b. 70–80% of subjects available for follow-up | 1 |

| c. < 70% of subjects available for follow-up | 0 |

| 8. Analysis (observational and experimental) | |

| a. Intention to treat/including all available data | 2 |

| b. Excluding drop-outs but evidence of bias adjusted or no bias evident | 1 |

| c. Excluding drop-outs and no attention to bias or imputing results | 0 |

| 9. Baseline differences between groups (experimental only) | |

| a. None or adjusted | 2 |

| b. Differences unadjusted | 1 |

| c. No information | 0 |

| d. Cohort/descriptive study only/not applicable | 0 |

| 10. Unit of allocation to intervention (experimental only) | |

| a. Appropriate | 2 |

| b. Nearly | 1 |

| c. Inappropriate or no control group | 0 |

| d. Cohort/descriptive study only/not applicable | 0 |

| 11. Randomization/method of allocation of subjects (experimental only) | |

| a. Random | 2 |

| b. Method not explicit | 1 |

| c. Before exclusion of drop-outs or nonrandomized | 0 |

| d. Cohort/descriptive study only/not applicable | 0 |

| Total score (possible 22) | |

| B. Qualitative scoring | |

| 1. Is there a clear connection to an existing body of knowledge/Theoretical framework? | |

| a. Yes | 1 |

| b. No | 0 |

| 2. Are research methods appropriate to the question being asked? | |

| a. Yes | 1 |

| b. No | 0 |

| 3. Is the description of the context for the study clear and sufficiently detailed? | |

| a. Yes | 1 |

| b. No | 0 |

| 4. Is the description of the method clear and sufficiently detailed to be replicated? | |

| a. Yes | 1 |

| b. No | 0 |

| 5. Is there an adequate description of the sampling strategy? | |

| a. Yes | 1 |

| b. No | 0 |

| 6. Is the method of data analysis appropriate and justified? | |

| a. Yes | 1 |

| b. No | 0 |

| 7. Are procedures for data analysis clearly described and in sufficient detail? | |

| a. Yes | 1 |

| b. No | 0 |

| 8. Is there evidence that the data analysis involved more than one researcher? | |

| a. Yes | 1 |

| b. No | 0 |

| 9. Are the participants adequately described? | |

| a. Yes | 1 |

| b. No | 0 |

| 10. Are the findings presented in an accessible and easy-to-follow manner? | |

| a. Yes | 1 |

| b. No | 0 |

| 11. Is sufficient original evidence provided to support the relationship between interpretation and evidence? | |

| a. Yes | 1 |

| b. No | 0 |

| Total score (possible 11) | |

Highlights.

Video education in hospice and palliative care (HPC) has been understudied.

The evidence supports the use of video education in hospice and palliative care.

Video interventions have positive impact on preferences and advance care planning.

Videos are a promising tool for education and communication enhancement in HPC.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We would like to thank the Medical Student Training in Aging Research (MSTAR) Program Scholarship for supporting the work of A.P.R. in this project. We also would like to thank the librarian Carrie Price at the JHH Welch Center for her assistance in the article search strategy.

FUNDING

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute and award number R01CA203999 (Parker Oliver) through a Diversity Supplement. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Nothing to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Dulce M. Cruz-Oliver, Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine, Palliative Medicine Program, Johns Hopkins Hospital 600 N. Wolfe Street, Suite 342B, Baltimore, MD 21287.

Angel Pacheco Rueda, Medical Student, University of Puerto Rico, Medical Sciences Campus, School of Medicine Box 365067 San Juan, PR 00936-5067.

Liliana Viera-Ortiz, Assistant Professor of Palliative Care, University of Puerto Rico, Medical Sciences Campus, Department of Surgery Box 365067 San Juan, PR 00936-5067.

Karla T. Washington, Associate Professor of Family and Community Medicine, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Missouri Medical Sciences Building, DC032.00 Columbia, MO, 65212 USA.

Debra Parker Oliver, Paul Revare Family Professor of Family Medicine. Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Missouri Medical Sciences Building, DC032.00 Columbia, MO, 65212 USA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sanders JJ, Curtis JR, Tulsky JA. Achieving Goal-Concordant Care: A Conceptual Model and Approach to Measuring Serious Illness Communication and Its Impact. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(S2):S17–S27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Austin CA, Mohottige D, Sudore RL, Smith AK, Hanson LC. Tools to Promote Shared Decision Making in Serious Illness: A Systematic Review. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(7):1213–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gysels M, Higginson IJ. Interactive technologies and videotapes for patient education in cancer care: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15(1):7–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quintiliani LM, Murphy JE, Buitron de la Vega P, Waite KR, Armstrong SE, Henault L, et al. Feasibility and Patient Perceptions of Video Declarations Regarding End-of-Life Decisions by Hospitalized Patients. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(6):766–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ostherr K, Killoran P, Shegog R, Bruera E. Death in the Digital Age: A Systematic Review of Information and Communication Technologies in End-of-Life Care. J Palliat Med. 2016;19(4):408–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baik D, Cho H, Masterson Creber RM. Examining Interventions Designed to Support Shared Decision Making and Subsequent Patient Outcomes in Palliative Care: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2019;36(1):76–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Methley AM, Campbell S, Chew-Graham C, McNally R, Cheraghi-Sohi S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: a comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.EndNote X9.1 for Windows & Mac. Philadelphia,PA: Clarivate Analytics; [updated 3/12/2019 Available from: endnote.com]. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Covidence systematic review software. Melbourne, Australia: Veritas Health Innovation; [Available from: www.covidence.org]. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oliver DP, Demiris G, Wittenberg-Lyles E, Washington K, Day T, Novak H. A systematic review of the evidence base for telehospice. Telemed J E Health. 2012;18(1):38–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higgins JPT GS. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 5.1.0 ed: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. [Available from: https://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/chapter_8/table_8_5_d_criteria_for_judging_risk_of_bias_in_the_risk_of.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aslakson RA, Isenberg SR, Crossnohere NL, Conca-Cheng AM, Moore M, Bhamidipati A, et al. Integrating Advance Care Planning Videos into Surgical Oncologic Care: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2019;22(7):764–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown JB, Beck A, Boles M, Barrett P. Practical methods to increase use of advance medical directives. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1999;14(1):21–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen SMV AE; Shaffer ML; Hanson LC; Habtemariam D; Mitchell SL Concordance Between Proxy Level of Care Preference and Advance Directives Among Nursing Home Residents With Advanced Dementia: a Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2018;57(1):37–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deep KS, Hunter A, Murphy K, Volandes A. “It helps me see with my heart”: How video informs patients’ rationale for decisions about future care in advanced dementia. Patient Education and Counseling. 2010;81(2):229–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El-Jawahri A, Podgurski LM, Eichler AF, Plotkin SR, Temel JS, Mitchell SL, et al. Use of Video to Facilitate End-of-Life Discussions With Patients With Cancer: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(2):305–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El-Jawahri A, Paasche-Orlow MK, Matlock D, Stevenson LW, Lewis EF, Stewart G, et al. Randomized, Controlled Trial of an Advance Care Planning Video Decision Support Tool for Patients With Advanced Heart Failure. Circulation. 2016;134(1):52–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Epstein AS, Shuk E, O’Reilly EM, Gary KA, Volandes AE. ‘We have to discuss it’: cancer patients’ advance care planning impressions following educational information about cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Psycho-Oncology. 2015;24(12):1767–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Epstein AS, Volandes AE, Chen LY, Gary KA, Li YL, Agre P, et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial of a Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Video in Advance Care Planning for Progressive Pancreas and Hepatobiliary Cancer Patients. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2013;16(6):623–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsui M Effectiveness of end-of-life education among community-dwelling older adults. Nurs Ethics. 2010;17(3):363–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toraya C Evaluation of advance directives video education for patients. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(8):942–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Volandes AE, Paasche-Orlow M, Gillick MR, Cook EF, Shaykevich S, Abbo ED, et al. Health literacy not race predicts end-of-life care preferences. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2008;11(5):754–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Volandes AE, Levin TT, Slovin S, Carvajal RD, O’Reilly EM, Keohan ML, et al. Augmenting advance care planning in poor prognosis cancer with a video decision aid A Preintervention-Postintervention Study. Cancer-Am Cancer Soc. 2012;118(17):4331–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Volandes AE, Ariza M, Abbo ED, Paasche-Orlow M. Overcoming educational barriers for advance care planning in Latinos with video images. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2008;11(5):700–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gant JR, Steffen AM, Lauderdale SA. Comparative outcomes of two distance-based interventions for male caregivers of family members with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2007;22(2):120–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gallagher-Thompson D, Wang PC, Liu W, Cheung V, Peng R, China D, et al. Effectiveness of a psychoeducational skill training DVD program to reduce stress in Chinese American dementia caregivers: results of a preliminary study. Aging Ment Health. 2010;14(3):263–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steffen AM. Anger management for dementia caregivers: A preliminary study using video and telephone interventions. Behav Ther. 2000;31(2):281–99. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jefford M, Karahalios E, Baravelli C, Schofield R, Carey M, Franklin J, et al. Development and evaluation of an evidence-based DVD for cancer survivors (CS) at treatment completion. Ejc Suppl. 2007;5(4):153–. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steffen AM, Gant JR. A telehealth behavioral coaching intervention for neurocognitive disorder family carers. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;31(2):195–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Volandes AEM SL; Gillick MR; Chang Y; Paasche-Orlow MK Using video images to improve the accuracy of surrogate decision-making: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2009;10(8):575–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McIlvennan CK, Matlock DD, Thompson JS, Dunlay SM, Blue L, LaRue SJ, et al. Caregivers of Patients Considering a Destination Therapy Left Ventricular Assist Device and a Shared Decision-Making Intervention: The DECIDE-LVAD Trial. JACC Heart Fail. 2018;6(11):904–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hanson LC, Zimmerman S, Song MK, Lin FC, Rosemond C, Carey TS, et al. Effect of the Goals of Care Intervention for Advanced Dementia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(1):24–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Volandes AE, Ferguson LA, Davis AD, Hull NC, Green MJ, Chang YC, et al. Assessing End-of-Life Preferences for Advanced Dementia in Rural Patients Using an Educational Video: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2011;14(2):169–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cruz-Oliver DM, Malmstrom TK, Fernandez N, Parikh M, Garcia J, Sanchez-Reilly S. Education Intervention “Caregivers Like Me” for Latino Family Caregivers Improved Attitudes Toward Professional Assistance at End-of-life Care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2016;33(6):527–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cruz-Oliver DM, Parikh M, Wallace CL, Malmstrom TK, Sanchez-Reilly S. What Did Latino Family Caregivers Expect and Learn From Education Intervention “Caregivers Like Me”? Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018;35(3):404–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kozlov E, Reid MC, Carpenter BD. Improving patient knowledge of palliative care: A randomized controlled intervention study. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(5):1007–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Capewell C, Gregory W, Closs S, Bennett M. Brief DVD-based educational intervention for patients with cancer pain: feasibility study. Palliat Med. 2010;24(6):616–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chung K, Augustin F, Esparza S. Development of a Spanish-Language Hospice Video. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2017;34(8):737–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pensak NA, Joshi T, Simoneau T, Kilbourn K, Carr A, Kutner J, et al. Development of a Web-Based Intervention for Addressing Distress in Caregivers of Patients Receiving Stem Cell Transplants: Formative Evaluation With Qualitative Interviews and Focus Groups. JMIR Res Protoc. 2017;6(6):e120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thomas K, Moore G. The development and evaluation of a multimedia resource for family carers of patients receiving palliative care: A consumer-led project. Palliative & Supportive Care. 2015;13(3):417–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leow MQH, Chan SWC. Evaluation of a video, telephone follow-ups, and an online forum as components of a psychoeducational intervention for caregivers of persons with advanced cancer. Palliative & Supportive Care. 2016;14(5):474–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lambing A, Markey CA, Neslund-Dudas CM, Bricker LJ. Completing a life: Comfort level and ease of use of a CD-ROM among seriously ill patients. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2006;33(5):999–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Durbin CR, Fish AF, Bachman JA, Smith KV. Systematic review of educational interventions for improving advance directive completion. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2010;42(3):234–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wittenberg-Lyles E, Oliver DP, Demiris G, Swarz J, Rendo M. YouTube as a Tool for Pain Management With Informal Caregivers of Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2014;48(6):1200–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.