Abstract

The Integrated Stress Response (ISR) helps metazoan cells adapt to cellular stress by limiting the availability of initiator methionyl-tRNA for translation. Such limiting conditions paradoxically stimulate the translation of ATF4 mRNA through a regulatory 5′ leader sequence with multiple upstream Open Reading Frames (uORFs), thereby activating stress-responsive gene expression. Here, we report the identification of two critical regulators of such ATF4 induction, the noncanonical initiation factors eIF2D and DENR. Loss of eIF2D and DENR in Drosophila results in increased vulnerability to amino acid deprivation, susceptibility to retinal degeneration caused by endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, and developmental defects similar to ATF4 mutants. eIF2D requires its RNA-binding motif for regulation of 5′ leader-mediated ATF4 translation. Consistently, eIF2D and DENR deficient human cells show impaired ATF4 protein induction in response to ER stress. Altogether, our findings indicate that eIF2D and DENR are critical mediators of ATF4 translational induction and stress responses in vivo.

Subject terms: Stress signalling, Gene regulation, Translation

Translation of ATF4 mRNA is stimulated during the integrated stress response. Here the authors show that two noncanonical translation initiation factors eIF2D and DENR are required for translational induction of ATF4 mRNA in Drosophila and human cells.

Introduction

The integrated stress response (ISR) in animals and a related-general amino acid control in yeast are adaptive signaling pathways that respond to a variety of stress conditions. Dysregulation of the ISR pathway is associated with a wide variety of diseases ranging from diabetes1–5 to neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s6–8, reflecting the importance of cellular stress adaptation in health. In addition, activation of the ISR aids cancer cell survival and metastasis by enhancing cellular adaptation to extrinsic stresses in the tumor microenvironment9–11.

ISR signaling is initiated by stress-activated kinases that phosphorylate the α-subunit of the eIF2 complex, thereby inhibiting eIF2’s ability to deliver initiator methionyl-tRNA (Met-tRNAiMet) to ribosomes (Fig. 1a)12–16. Such conditions reduce general mRNA translation in cells, but they also stimulate translation of the yeast GCN4 and the metazoan ATF4 main open reading frames, which encode transcription factors that mediate a signaling response12,17,18. These mRNAs have regulatory 5′ leader sequences containing multiple upstream open reading frames (uORFs), which interfere with main ORF translation in unstressed cells. Upon cellular stress that prompts eIF2α phosphorylation, this 5′ leader sequence now stimulates the main ORF translation (see Supplementary Fig 9 for schematic)18–22.

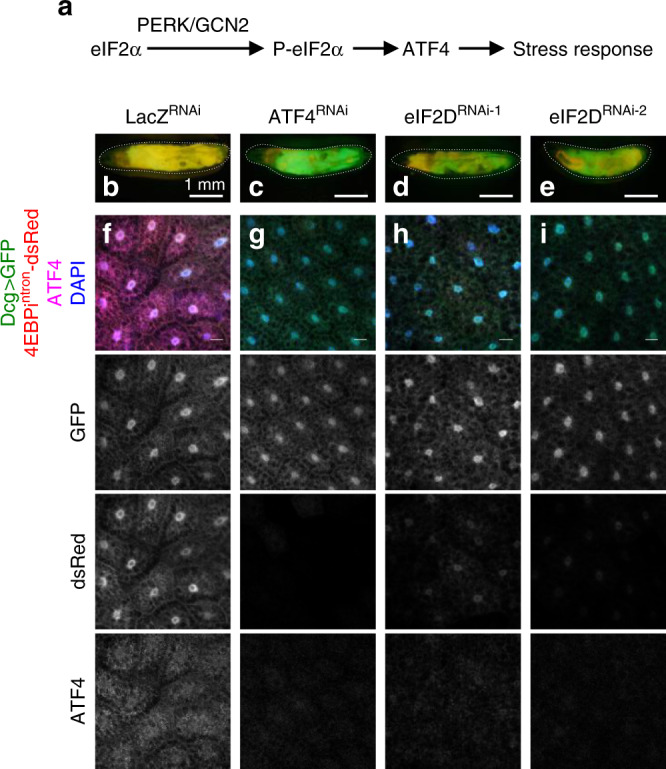

Fig. 1. An RNAi screen to identify genes required for ATF4 translation.

a Line diagram summarizing the ISR pathway in Drosophila. b–e Third instar larvae expressing 4E-BPintron-dsRed reporter with indicated RNAi lines and UAS-GFP driven by the fat body specific Dcg-Gal4. Individual larvae are outlined with dotted lines. Scale bars represent 1 mm. f–i Fat body tissues dissected from larvae in b–e expressing GFP (green), dsRed (red), immunolabeled with antiATF4 antibody (magenta) and DAPI (blue). Scale bars represent 25 μm unless otherwise indicated here and in subsequent figures. Data in b–i are representative images collected from two independent biological experiments with ten animals in each trial.

Thus far, eIF2 has been the only Met-tRNAiMet delivering factor implicated in initiation of ATF4 translation, and how ATF4 ORF translation is induced under limiting eIF2 conditions has remained poorly understood. Here we report the identification of a noncanonical methionyl-tRNA-delivering initiation factor, eIF2D, as a gene required for the translation of ATF4 in vivo. eIF2D is partially redundant with its homolog DENR in both Drosophila and in human cells. eIF2D requires its RNA-binding motif to regulate the ATF4 5′ leader. Loss of eIF2D and DENR in Drosophila phenocopies the pupal developmental defects observed in mutants of cryptocephal (crc), the Drosophila ATF4. In addition, eIF2D and DENR mutants are more vulnerable to amino acid deprivation and susceptible to age-dependent retinal degeneration in a Drosophila model of Retinitis Pigmentosa. Altogether, our findings indicate that noncanonical initiation factors are required for ISR signaling in vivo and provide insights into how ATF4 is translationally induced in stressed cells with attenuated general translation.

Results

eIF2D is a regulator of ATF4 mRNA translation

4E-BP is an established transcriptional target of ATF4 in both Drosophila and mammals10,23–26. Like mammals, Drosophila cells detect stress through conserved eIF2α kinases that activate ATF4-mediated ISR signaling27–29. We previously generated a transgenic Drosophila line in which the ATF4 responsive element in 4E-BP (4E-BPintron) drives the expression of dsRed. This line reports physiological ATF4 signaling in the late third instar larval fat body, an adipose-like tissue present underneath the cuticle of the larval torso24 (Fig. 1b, f). 4E-BPintron-dsRed is also expressed in the salivary glands located at the anterior end of each larva, but this signal is not affected by loss of ATF424. Thus, we focused on the dsRed fluorescence in the fat body to assess ATF4 signaling activity.

To identify genes required for ATF4 signaling, we drove expression of UAS-RNAi lines targeting genes annotated as translation initiation factors using the fat body-specific Dcg-Gal4 driver (Supplementary Table 1). We also co-expressed UAS-GFP together as a control. We selected for RNAi lines that suppressed 4E-BPintron-dsRed expression (reporting ATF4 activity) but had no effect on control GFP expression (reporting general cellular translation). As we reported previously24, the RNAi line targeting ATF4 caused a loss of dsRed but no change in GFP (Fig. 1c, g). Of the 50 RNAi lines targeting 28 genes, one of the two that targeted Pdcd4 (Programmed cell death 4, FlyBase ID: FBgn0030520) and two lines targeting eIF2D (eukaryotic Initiation Factor 2D, FlyBase ID: FBgn0041588) reduced 4E-BPintron-dsRed expression in the fat body (Fig. 1d, e and Supplementary Table 1). The two independent eIF2D RNAi lines targeted different regions of the gene, and therefore, we considered eIF2D a high confidence hit. The results from the screen were confirmed in dissected fat body tissues, which had decreased 4E-BPintron-dsRed signal upon knockdown of eIF2D without affecting control GFP expression (Fig. 1h, i). Additional immunolabeling with anti-ATF4 showed that eIF2D knockdown reduced ATF4 protein levels in the fat body (Fig. 1h, i). These experiments suggest that eIF2D is required for ATF4 expression in the fat body, but not for general mRNA translation.

To validate our data from RNAi experiments, we generated two independent mutant alleles of eIF2D. We deleted a large genomic locus that spans eIF2D to generate a “Deficiency” line, Df(3R)eIF2D (Supplementary Fig. 1a). This deficiency was complemented with a genomic rescue transgene that deletes only the eIF2D sequence to generate the eIF2D mutant, Df.ΔeIF2D (Supplementary Fig. 1a; see “Methods” section). An equivalent line with a wild-type eIF2D rescue transgene, Df.eIF2DWT, was also generated for comparison. A second allele was made using CRISPR–Cas9 gene editing (eIF2DCR1, Supplementary Fig. 1b). Both alleles abolished eIF2D expression as detected through western blots (Fig. 2a, b). Consistent with the RNAi data, eIF2D mutants showed reduced ATF4 pathway activity as assessed by an 85% decrease in 4E-BPintron-dsRed in the fat body (Fig. 2c–e, j and Supplementary Fig. 1c–e). In contrast, loss of eIF2D had only a very minor effect on the expression of a control GFP transgene (Fig. 2g, h, j). We ascribe this minor change to variations in genetic background because it was not reproducible in the Df(3R)eIF2D/eIF2DCR1 transheterozygote (see Fig. 3k). Thus, we conclude that the effect of eIF2D loss is specific for the ATF4 signaling reporter, 4E-BPintron-dsRed.

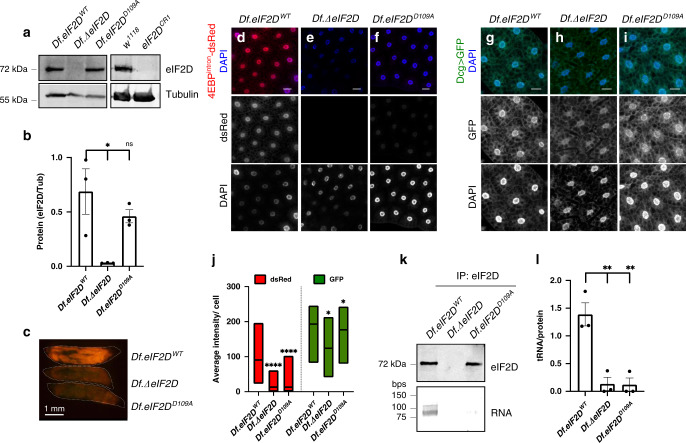

Fig. 2. eIF2D is required for ATF4 expression and ISR signaling.

a Western blot analysis of larval extracts from various allelic combinations of eIF2D mutants. w1118 is the isogenic wild type control for eIF2DCR1. b Quantitation of data from western blots in a representing the mean of three independent biological replicates with error bars representing standard error. c Expression of 4E-BPintron-dsRed in control larvae (Df.eIF2DWT), eIF2D deletion mutant (Df.ΔeIF2D) and an eIF2D mutant where the tRNA-binding interface is disrupted (Df.eIF2DD109A). Individual larvae are shown in dotted outlines. d–f Fat body tissues dissected from larvae in c showing 4E-BPintron-dsRed (red), and counterstained with DAPI (blue). g–i Fat body tissues from larvae of indicated genotypes expressing GFP (green) driven by the fat body specific driver, Dcg-GAL4, and counterstained with DAPI (blue). j Quantitation of fluorescent protein intensity from individual cells in d–f and g–i. Midline represents the mean value, with the top and bottom of the box representing the maximum and minimum values. Asterisks above boxes represent statistical significances between mutant and control values. n = 278, 341, 231, 213, 335, and 395, respectively for each box from left to right. k Analysis of eluates from immunoprecipitation of eIF2D. Top panel shows western blot analysis of eluates and bottom panel shows TBE-UREA gel analysis of bound RNA. l. Quantification of data from k representing the mean of four biological replicates, with RNA levels for each sample normalized to respective protein levels. Data in c–i are representative images collected from two independent biological experiments with ten animals in each trial. Statistical significance in b, j, and l were calculated using the two-tailed t-test with ****p < 0.00001, **p < 0.001, *p < 0.01 and n.s. not significant. Please see Source Data Files for the raw data in a, b, j, k, l.

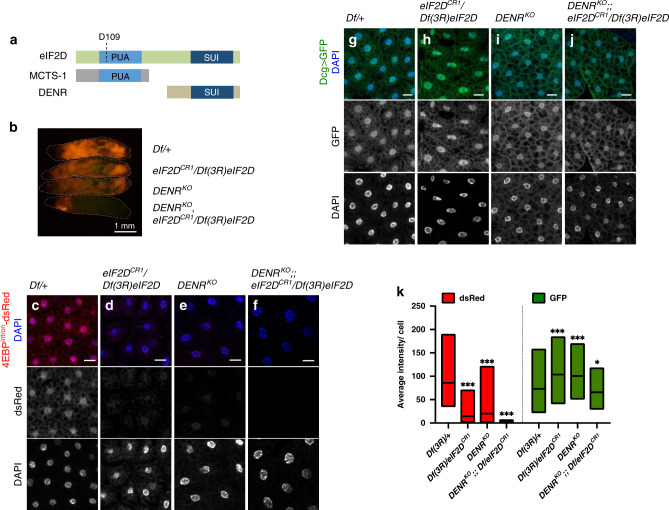

Fig. 3. eIF2D shares its function with DENR.

a A schematic diagram showing the domain architecture of eIF2D, DENR, and MCTS-1. b Expression of 4E-BPintron-dsRed in eIF2D and DENR single mutants (DENRKO) compared with that of DENR; eIF2D double mutants. Individual larvae are indicated with dotted outlines and their genotypes are indicated on the right. c–f Fat body tissues dissected from larvae in b showing 4E-BPintron-dsRed (red) and DAPI (blue). g–j Fat body tissues from larvae of indicated genotypes expressing GFP (green) driven by the fat body specific driver, Dcg-GAL4, and counterstained with DAPI. k Quantitation of fluorescent protein intensity from individual cells in c–j. Midline represents the mean value, with the top and bottom of the box representing the maximum and minimum values. Asterisks above boxes represent statistical significances between mutant and control values calculated with the a two-tailed t-test with ***p < 0.0001 and *p < 0.01. n = 384, 370, 426, 362, 103, 158, 145, and 138, respectively for each box from left to right. Data in b–j are representative images collected from three independent biological experiments with seven animals in each trial. Please see Source Data Files for the raw data used to generate graph in k.

To further confirm these results, we attempted to rescue the loss of 4E-BPintron-dsRed expression in eIF2D mutants by ectopically expressing a transgene containing the Drosophila ATF4 coding sequence without the 5′ leader (crcleaderless) to ensure ATF4 expression independent of upstream regulators. Fat body-specific expression of crcleaderless, but not a control transgene (lacZ), in eIF2D mutants restored the expression of 4E-BPintron-dsRed (Supplementary Fig. 2). Notably, overexpression of ATF4 with the crcleaderless transgene resulted in fragile fat body tissues in both control and eIF2D mutant animals, and led to an increase in 4E-BPintron-dsRed expression even in control animals (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b, d, f).

eIF2D requires its RNA-binding motif for ATF4 regulation

eIF2 has been the only known Met-tRNAiMet-delivering translational initiation factor implicated in ATF4 mRNA translation. At the same time, it has been established in yeast and mammals that translation of the GCN4 and ATF4 main ORF requires eIF2 inhibition17,30. Under these conditions, it is assumed that residual eIF2 activity mediates translation initiation of the ATF4 main ORF. Identification of eIF2D as an ATF4 regulator was intriguing, as previous studies have shown that eIF2D can deliver Met-tRNAiMet to P-sites of ribosomes on AUG start codons in vitro31–33. eIF2D does not share sequence homology with eIF2; it contains a PUA domain capable of interacting with Met-tRNAiMet, and a SUI1 domain that can recognize start codons31,32. Based on the available crystallographic structures of RNA-bound PUA domains and the cryoEM structure of eIF2D bound to uncharged tRNA (PDB:5oa3), we generated a third eIF2D mutant line with an amino acid residue substitution at the PUA domain:RNA binding interface (Df.eIF2DD109A, Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 3a, also see Fig. 3a). The D109A mutant protein was expressed at similar levels to wildtype eIF2D as assessed by western blots from larval tissues (Fig. 2b).

The human equivalent of D109 is D111, which is close to the first cytosine (C) of the universally-conserved CCA tail of the tRNA, likely to help stabilize the bound tRNA (Supplementary Fig. 3b)33,34. The D109A mutation was designed to specifically diminish tRNA binding without destabilizing the whole PUA fold. To test this, we immunoprecipitated eIF2D from wild-type control larvae (Df.eIF2DWT) and found nucleic acid species roughly the size of tRNA that co-purified with the eIF2D protein (Fig. 2k). No such species were detected in the eIF2D deletion mutants (Df.ΔeIF2D) (Fig. 2k, l). The co-purifiying nucleic acid species was DNase-insensitive but RNase-sensitive (Supplementary Fig. 3c), indicating that eIF2D binds an RNA molecule. Consistent with our predictive modeling, the D109A mutant protein failed to copurify with the RNA species that was associated with the wild-type protein (Fig. 2k, l). We also found evidence that the eIF2DD109A mutation disrupts ATF4 signaling. In comparison to the control Df.eIF2DWT genotype, the 4E-BPintron-dsRed reporter was significantly diminished in the Df.eIF2DD109A mutants (Fig. 2c, f, j) without significantly affecting the expression of a control GFP transgene (Fig. 2i, j). We note that the D109A allele had a slightly reduced effect on the ATF4 pathway reporter in comparison to the null allele (Fig. 2j). We speculate that this could be due to trace amounts of RNA binding activity in the D109A mutant that we could not detect in our experiments.

eIF2D shares its function with DENR

Although eIF2D mutants show a substantial decrease in 4E-BPintron-dsRed, we did not see a complete loss in the reporter signal (Fig. 2c, j and Supplementary Fig. 1c), suggesting that other factors act redundantly with eIF2D. For this reason, we turned our attention to Density-regulated reinitiation and release factor (DENR) and Multiple copies in T-cell lymphomas-1 (MCTS-1), two other proteins that contain SUI and PUA domains respectively (Fig. 3a). DENR and MCTS-1 have been implicated in regulating translation reinitiation of uORF containing transcripts that regulate growth and development in nonstressed cells35. In vitro biochemical assays show that eIF2D has the same function as the DENR–MCTS1 complex, that as a heterodimer reconstitutes the domain architecture of eIF2D31,34,36,37. While there are no available MCTS-1 loss-of-function mutants, a null DENRKO strain was reported previously35. In this mutant background, we saw reduction of 4E-BPintron-dsRed expression like that seen in eIF2D mutants (Fig. 3b–e). Strikingly, double mutants for eIF2D and DENR showed a complete loss of 4E-BPintron-dsRed in the fat body (Fig. 3b, c, f), with only ATF4-independent dsRed signals remaining in the salivary glands near the anterior end of the larvae. Like our analyses with eIF2D mutants, we attempted to rescue this loss of 4E-BPintron-dsRed by ectopic expression of the crcleaderless transgene in the fat body. When raised at either 25 or 20 °C, we could not recover eIF2D DENR double mutants overexpressing ATF4. However, we observed a complete rescue of 4E-BPintron-dsRed in DENRKO eIF2DCR1/+ animals raised at 20 °C (Supplementary Fig. 4). These results indicate that eIF2D and DENR both contribute to ATF4 signaling.

We compared the phenotypic consequences of DENR and eIF2D loss-of-function with that of the Drosophila ATF4 ortholog, cryptocephal (crc). crc is so named because the mutant animals exhibit a cryptocephalic, or hidden head phenotype, characterized by complete absence of a head and failure to extend the wings and legs38 during pupation (c.f. Fig. 4c vs. f), the developmental transition between prepupa and pupa (Fig. 4a). The cryptocephalic phenotype is extremely rare, with only five other loss-of-function Drosophila mutant alleles reported to exhibit this defect at a low penetrance (Eip74EFPneo24, brrbp-5, ftz-f1ex17, Kr-h11, and Sox14L1; Flybase)39–43. These five genes are conserved regulators of ecdysone signaling during insect metamorphosis. Importantly, DENR eIF2D double mutant animals, like crc mutant animals, exhibit a fully penetrant cryptocephalic phenotype (Fig. 4b). Loss of even one allele of eIF2D in DENR mutants resulted in a cryptocephalic phenotype (Fig. 4e), underscoring the contribution of both genes to ATF4 expression during development. crc and DENR eIF2D double mutants also exhibit other striking similarities, including lethality during larval stages (Fig. 4b) and defects during puparium formation (Supplementary Fig. 5a, d, e). In contrast, neither DENR nor eIF2D single mutants recapitulate crc mutant phenotypes. eIF2D single mutant animals are viable and do not exhibit any obvious developmental defects (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 5b), while DENR mutant animals primarily arrest during pupal stages of development35 (Fig. 4b) with minor defects in pupation (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 5c). The difference in severity between eIF2D and DENR mutants suggest that these factors may act in a tissue-specific manner and/or have other essential targets, a few of which are reported for DENR35,44,45. Taken together, our results demonstrate that the DENR eIF2D double mutant phenotype bears marked resemblance to the crc mutant phenotype, suggesting that DENR and eIF2D function redundantly to regulate ATF4 signaling during development.

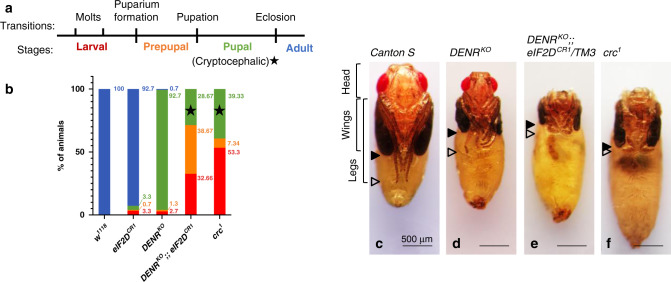

Fig. 4. DENR eIF2D double mutants resemble ATF4 mutants.

a Schematic of developmental transitions during the Drosophila life cycle. b Lethal phase analysis for control, eIF2D, DENR, DENR eIF2D double, and crc animals. Developmental stages are color-coded as shown in the schematic in a. Star symbol indicates animals that arrest during metamorphosis as cryptocephalic pupae. n = 150 for each genotype. c–f Analysis of pupal morphology in dissected control (Canton S), DENR, DENR eIF2D/TM3, and crc mutant animals. Solid arrowheads indicate the degree of wing extension and outlined arrowheads indicate the extent of leg extension. An extended analysis of lethal phase and animal morphology can be found in Supplementary Information (Extended analysis of lethal phase and animal morphology). Data in c–f are representative images collected from two independent biological experiments with ten animals in each trial. Scale bars are 500 μm.

Loss of eIF2D and DENR results in impaired stress responses

To determine the physiological role of eIF2D in stress responses, we subjected wild type and eIF2D mutant flies to amino acid deprivation, a condition that activates the eIF2α kinase GCN2, culminating in the transcriptional induction of 4E-BP by ATF424. Under normal feeding conditions, most eIF2DCR1and DENRKO single or double mutant second instar larvae survived at high rates in the 8-h window of inspection. However, the survival rate decreased significantly in these mutants when grown on amino acid-deprived food for 8 h, comparable to that observed in the ATF4 mutant, crc1 (Fig. 5a). This reduced survival was consistent with the impaired transcriptional induction of 4E-BP (Fig. 5b). Notably, deletion of both eIF2D and DENR resulted in a ~50% decrease in ATF4 mRNA (Supplementary Fig. 6a), suggesting destabilization of the ATF4 transcript in the absence of these translation factors. However, the reduction in ATF4 mRNAs is modest, compared to the ~95% reduction in the ATF4 reporter (4E-BPintron-dsRed) expression (Fig. 3k). We further confirmed that reducing ATF4 gene dosage in half by using crc1 heterozygous mutants did not affect 4E-BPintron-dsRed expression in the fat body (Supplementary Fig. 6b–d).

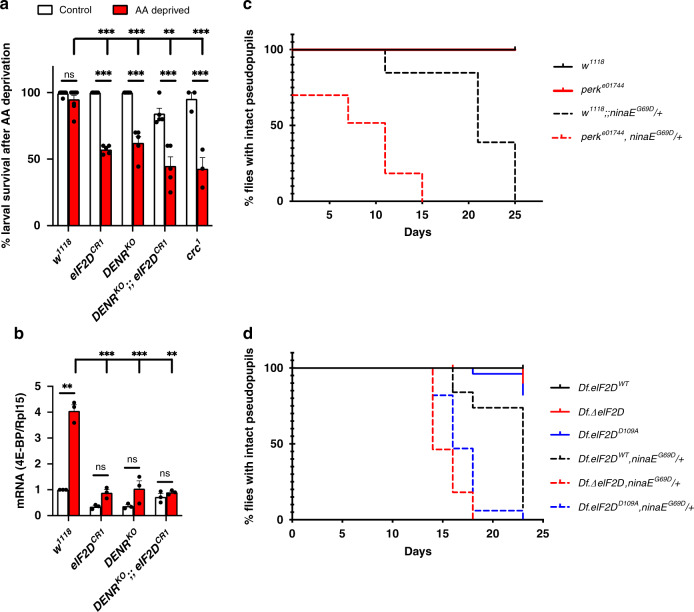

Fig. 5. eIF2D and DENR modulate stress response phenotypes.

a Survival rate of second instar larvae of the indicated genotypes when fed with normal food (white bars) or amino acid deprived food (4% sucrose, red bars) for 8 h. Data represent the mean from five independent experiments with 20 animals in each trial, and error bars represent standard error. b qPCR analysis of 4E-BP mRNA levels in larvae from a. Data are the mean from three independent experiments, with error bars representing standard error. In both a, b, p values were calculated using the two-tailed t-test with **p < 0.001, ***p < 0.0001 and n.s. not significant. c Photoreceptor degeneration in the ninaEG69D/+ adRP model in control and perk mutants as assessed by Rh1-GFP fluorescence that allows for visualization of photoreceptors in adult pseudopupils. Note that the lines for w1118 (solid black) and perke01744 (solid red) overlap. The difference in the course of retinal degeneration between the following pairs is statistically significant as assessed by the Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test (p < 0.0001): w1118 and w1118;;ninaEG69D/+, perke01744 and perke01744,ninaEG69D/+, w1118;;ninaEG69D/+ and perke01744,ninaEG69D/+. (n = 100). d Photoreceptor degeneration with ninaEG69D/+ monitored in various eIF2D mutant backgrounds. Note that the curves for the control Df.eIF2DWT (solid black), Df.ΔeIF2D (solid red) and Df.eIF2DD109A (solid blue) overlap for the early time points. The difference in the course of retinal degeneration between the following pairs is statistically significant as assessed by Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test (p < 0.0001): Df.eIF2DWT and Df.eIF2DWT,ninaEG69D/+, Df.ΔeIF2D and Df.ΔeIF2D,ninaEG69D/+, Df.ΔeIF2D and Df.ΔeIF2D,ninaEG69D/+, Df.eIF2DWT,ninaEG69D/+ and Df.ΔeIF2D,,ninaEG69D/+, Df.eIF2DWT,ninaEG69D/+ and Df.eIF2DD109A,ninaEG69D/+. (n = 100). Please see Source Data Files for the raw data in a–d.

To examine the role of eIF2D in a pathological context, we employed a Drosophila model for autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa (adRP), which utilizes a dominant point mutation in the endogenous Rh-1 encoding gene, ninaE (ninaEG69D)46,47. These mutations are analogous to the Rhodopsin mutants that underlie human adRP48,49. The misfolding-prone Rh-1G69D protein encoded by the Drosophila ninaEG69D allele imposes endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and triggers age-dependent retinal degeneration similar to the human disease50,51. Misexpression of Rh-1G69D in larval imaginal disks results in induction of ATF4 protein52 and its downstream target 4E-BP24. However, the role of ATF4 signaling in age-related retinal degeneration of ninaEG69D mutant adults has not been established. To do so, we examined PERK, the eIF2α kinase required for ATF4 induction in response to ER stress17. As mentioned above, crc1 mutants arrest during development, but loss-of-function perk mutants (perke01744)29 are viable and therefore amenable for age-related retinal degeneration analysis. Using the Rh1-GFP reporter that marks intact retinal photoreceptors (see “Methods” section), we observed that perk homozygous mutants in a ninaE wild type background did not show any signs of age-related retinal degeneration (Fig. 5c). As reported previously50,53, flies bearing the heterozygous ninaEG69D mutation exhibit photoreceptor degeneration between from 12 to 25 days after eclosion. The course of retinal degeneration in the ninaEG69D heterozygous flies was dramatically accelerated in perke01744 animals, with approximately 30% of flies exhibiting retinal degeneration at eclosion, and all flies showing retinal degeneration by day 15 (Fig. 5c). These results indicate that ISR signaling plays a protective role during retinal degeneration in response to ER stress.

We next examined if eIF2D affects retinal degeneration in the ninaEG69D model. Compared to control Df.eIF2DWT flies bearing the heterozygous ninaEG69D mutation, Df.ΔeIF2D mutant flies in an otherwise equivalent genetic background showed an early onset of degeneration at 14 days, with the data being statistically significant at p < 0.0001 as measured by the log rank analysis (Fig. 5d). Consistent with observations using 4E-BP-dsRed (Fig. 2c–f), the Df.eIF2DD109A RNA-binding mutant allele showed an intermediate phenotype in the ninaEG69D heterozygous background, with the majority of the flies undergoing degeneration at 16 days (Fig. 5d). The accelerated retinal degeneration phenotype of eIF2D mutants is similar to that observed in perk mutants, albeit less severe, likely due to the presence of DENR–MCTS1. The adult retinal degeneration phenotype could not be tested in DENRKO animals which are pupal lethal, as described above. None of the control or mutant alleles showed retinal degeneration in the absence of the ninaEG69D allele (Fig. 5d). These data indicate that eIF2D plays a protective role in ER stress-induced photoreceptor degeneration.

eIF2D and DENR control gene expression through the ATF4 5′ leader

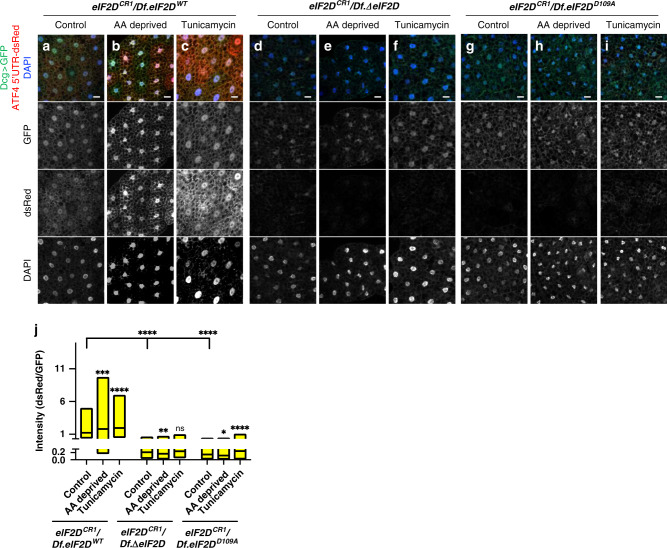

Since eIF2D was originally characterized as a putative translation initiation factor31,32, we sought to test if it regulates the translation of ATF4 mRNA via its 5′ leader. Using a reporter, where the coding sequence of ATF4 is replaced with nuclear localization sequence-tagged dsRed and expressed via a tubulin promoter (ATF4 5′UTR-dsRed)54, we found that Df.ΔeIF2D and Df.eIF2DD109A mutant larvae have reduced nuclear dsRed signals in the fat body without affecting control GFP expression (Fig. 6a, d, g, j), indicating that the effect of eIF2D loss is specific to our reporter with the ATF4 5′ leader. Loss of DENR showed a similar reduction in the expression of the ATF4 5′UTR-dsRed reporter (Supplementary Fig. 7), indicating that eIF2D and DENR likely regulate ATF4 mRNA translation via the ATF4 5′ leader. We also tested the effect of eIF2D on the induction of ATF4 via its 5′UTR in response to stress imposed by amino acid deprivation or Tunicamycin54. We found that both Df.ΔeIF2D and Df.eIF2DD109A mutant larvae showed little to no induction of ATF4 5′UTR-dsRed in response to either amino acid deprivation (Fig. 6b, e, h, j) or Tunicamycin feeding (Fig. 6c, f, i, j), while control larvae (Df.eIF2DWT) showed an expected increase in dsRed expression in both conditions (Fig. 6j). There was little to no effect on expression of a control GFP transgene in any of the conditions or genotypes tested (Fig. 6a–i).

Fig. 6. eIF2D and DENR regulate the translation of the ATF4 ORF.

a–i Expression of the ATF4 5′UTR-dsRed reporter in fat bodies of control (Df.eIF2DWT), eIF2D transheterozygous null (Df.ΔeIF2D) and point (Df.eIF2DD109A) mutants. The reporter utilizes a dsRed reporter bearing a nuclear localization sequence. Control GFP expression is driven by Dcg-GAL4. Larvae in b, e, h were subjected to 4 h of amino acid deprivation and those in c, f, i were fed Tunicamycin for 4 h. Data are representative images collected from two independent biological experiments with ten animals in each trial. j Quantification of the ATF4 5′UTR-dsRed reporter intensities normalized to corresponding GFP intensities from the same cells. Midline represents the mean value, with the top and bottom of the box representing the maximum and minimum values. Asterisks above the boxes represent statistical significances between mutant and control values calculated with the a two-tailed t-test with ***p < 0.0001 and *p < 0.01. n = 158, 157, 112, 104, 139, 131, 120, 148, and 137, respectively for each box from left to right. Please see Source Data Files for raw data.

Human cells require eIF2D and DENR for stress-induced ATF4 induction

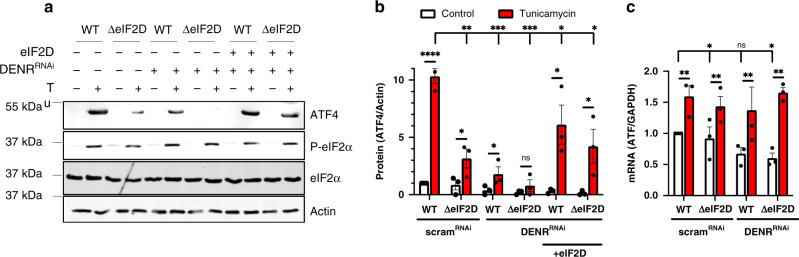

To determine if the role of eIF2D in ATF4 translation is conserved in humans, we assessed ATF4 expression in HAP1 cells (a near haploid human cell line), where eIF2D was deleted using CRISPR-Cas9 editing (ΔeIF2D). As expected, treatment with the ER stress-causing chemical Tunicamycin induced ATF4 protein synthesis in wild type (WT) control cells, while ΔeIF2D HAP1 cells showed a partial reduction in ATF4 induction under otherwise equivalent conditions (Fig. 7a, b and Supplementary Fig. 8a, b). Knocking down DENR in WT HAP1 cells also resulted in a partial decrease in ATF4 induction in response to Tunicamycin treatment (Fig. 7a, b). Consistent with the Drosophila system, knocking down DENR in ΔeIF2D HAP1 cells (Supplementary Fig. 8c, d) led to a substantial loss of ATF4 induction, more so than individually depleting eIF2D or DENR (Fig. 7a, b). While these conditions blocked ATF4 synthesis, they did not reduce eIF2α phosphorylation (Fig. 7a and Supplementary Fig. 8a, e), ruling out the possibility that eIF2D and DENR indirectly affect ATF4 through upstream factors. The loss of ATF4 induction in cells lacking eIF2D and DENR was rescued by transgenic expression of eIF2D, ruling out potential off-target effects of CRISPR-Cas9 or DENR siRNA (Fig. 7a, b). As reported previously, induction of stress led to a moderate increase in ATF4 mRNA levels55, which is also seen in ΔeIF2D HAP1 cells and WT cells treated with DENR siRNA (Fig. 7c). While depletion of both DENR and eIF2D saw a ~40% decrease in ATF4 mRNA levels in unstressed cells, ATF4 mRNA amount in Tunicamycin-treated cells were not significantly different (Fig. 7c), consistent with a requirement for eIF2D and DENR in ATF4 mRNA translation during stress.

Fig. 7. Regulation of ATF4 by eIF2D and DENR is conserved in human cells.

a Western blots of total cell lysates from control human HAP1 cells (WT) or equivalent cells with CRISPR-Cas9 mediated deletion of the eIF2D locus (ΔeIF2D). Cells were transfected with scrambled RNAi or DENR RNAi, and treated with DMSO or Tunicamycin (Tu, 10 μg/ml). pcDNA-heIF2D was used to re-introduce human eIF2D into cells. The blots were probed with antibodies recognizing ATF4 (panel 1), phospho-eIF2α (panel 2), total eIF2α (panel 3), and actin (panel 4). b Quantitation of ATF4 protein levels in a as normalized to the loading control (actin). Data are the mean of 3 independent experiments. c qPCR analysis of ATF4 mRNA in HAP1 cells from a normalized to GAPDH. Data are the mean of three independent experiments. Error bars represent standard error, p values were calculated using the two-tailed t-test with *p < 0.01, **p < 0.001, ****p < 0.00001 and n.s. not significant. Please see Source Data Files for raw data in a–c.

Discussion

Here, we report eIF2D and DENR as previously unrecognized regulators of ATF4 translation in Drosophila and human cells. Though several studies have examined regulatory targets of DENR individually35,44, none have uncovered the link between these translational initiation factors and ATF4-mediated ISR signaling. Our data show that in the absence of both eIF2D and DENR, ATF4 fails to be induced in Drosophila and human HAP1 cells. Furthermore, we demonstrate that the loss of eIF2D and DENR disrupts a number of pathophysiological processes in Drosophila that also require ATF4 signaling.

Previously reported biochemical functions of eIF2D and DENR-MCTS-1 as noncanonical Met-tRNAiMet delivering translation initiation factors32,56 provide mechanistic insights regarding the translational regulation of ATF4. For mRNAs with single ORFs in their 5′ leaders, the AUG codon procures the first methionine through ribosomes associated with the eIF2-GTP-Met-tRNAiMet ternary complex21. However, during translation of mRNAs with multiple uORFs, such as those seen in the ATF4 5′ leader (schematic in Supplementary Fig. 9), the scanning ribosome consumes the Met-tRNAiMet upon encountering the uORFs. Therefore, translation initiation at the ATF4 main ORF requires the scanning ribosomes to acquire another Met-tRNAiMet. We posit that eIF2D and DENR (together with MCTS-1) could act as Met-tRNAiMet delivery factors for the ATF4 ORF (model in Supplementary Fig. 9). This is supported by previous in vitro experiments showing that eIF2D can act as a noncanonical Met-tRNAiMet carrier31,56, and by our data showing that the RNA binding interface within the PUA domain of eIF2D is required for regulation of ATF4 via the 5′ leader. This model of eIF2D and DENR–MCTS1 acting as noncanonical Met-tRNAiMet carriers would predict a decreased occupancy of ribosomes at the ATF4 main ORF in the absence of eIF2D and DENR-MCTS1. An accompanying manuscript by Teleman and colleagues57 also independently reports that loss of DENR negatively affects ATF4 translation due to decreased ribosome occupancy at the ATF4 ORF, validating our hypothesis. These data support our model that eIF2D and DENR affect translation of ATF4, and warrant future studies to further understand the molecular mechanism of this model.

eIF2D and DENR-MCTS-1 have been demonstrated to also participate in ribosome recycling after translation termination31,56,58. If this were the primary function of eIF2D and DENR-MCTS-1 in translation of the ATF4 mRNA, decreased ribosome recycling in eIF2D DENR double mutants would be predicted to have the effect of enhancing ATF4 main ORF translation. In Saccharomyces cerevisae, the homologs of eIF2D, DENR, and MCTS-1 (Tma64 Tma22, and Tma20, respectively) have more prominent roles in ribosome recycling as evidenced by increased translation of downstream of ORFs and uORFs58. The translation of GCN4, the S. cerevisiae equivalent of ATF4, also increases upon the loss of these recycling factors59. Together, these findings suggest that the in vivo roles of eIF2D, DENR, and MCTS have diverged during evolution, with metazoan factors playing more prominent roles in translational initiation of ATF4 mRNA.

In conclusion, we report that unconventional Met-tRNAiMet delivery factors are required for ATF4 induction during ISR signaling in Drosophila and humans. This discovery provides insights into how ATF4 translation occurs efficiently in stressed cells, where the canonical Met-tRNAiMet delivery factor, eIF2, is inhibited by eIF2α kinases. Additionally, since abnormal ISR signaling is associated with a wide range of metabolic and degenerative diseases in humans, we anticipate these findings to have clinical impact.

Methods

Drosophila genetics

All Drosophila lines generated and used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Flies were reared under standard conditions. Oligos are listed in Supplementary Table 2. For quantification of fluorescent images and western blots, p-values were calculated using the two-tailed T-test for two independent means. For retinal degeneration assays, p values were calculated through Log-rank analysis using the Mantel-Cox test.

eIF2D mutants (Df(3R)eIF2D)

To generate a Deficiency line deleting the eIF2D locus, we employed the FRT-mediated recombination strategy using two insertion lines PBac{PB}CG14512[c06309] and PBac{WH}eIF2D[f04182]. eIF2D rescue transgenes (depicted in Supplementary Fig. 1a), were amplified using a BACPAC plasmid (CH321-74G8) as template. For the eIF2DD109A rescue transgene, the WT rescue plasmid was cut with unique sites Bsu36I and StuI and replaced with a corresponding D109A mutation-bearing DNA fragment generated by gene synthesis. The rescue fragments were cloned into the EcoR1 site in p-attB by InFusion assembly (ClonTech) and injected into embryos for targeted insertion into the attP2 locus. The resulting transgenes were recombined with the Df(3R)eIF2D lines to generate Df.eIF2DWT wild type and the Df.ΔeIF2D mutant lines. To generate eIF2DCR1, we used CRISPR-Cas9 to introduce a single cut in the first exon of eIF2D and used homology directed repair to introduce a 22 bp deletion (see Supplementary Table 2 for guide RNA and homology arm primers).

UAS-crcleaderless transgenic fly: The main ORF from the crc RA isoform was amplified from w1118 adult cDNA and was cloned into the pUAST plasmid between the EcoRI and XbaI sites. Transgenic flies were generated by injecting this plasmid in w1118 embryos by standard P-element transformation.

Lethal phase analysis

50 L1 larvae of the appropriate genotype were picked and placed in a vial containing standard cornmeal molasses media supplemented with yeast paste. Three vials were tested per genotype for a total n of 150. Animals were allowed to mature at 25 °C for 14 days. After 14 days, animals that had not eclosed were transferred to a grape agar plate and allowed to age for an additional 7 days at 25 °C to determine final lethal phase. Bainbridge and Bownes staging criteria was used to determine lethal phases during metamorphosis60.

Pupa imaging

Animals of the appropriate genotype and developmental stage were imaged while in the pupal case (for puparium morphology) or dissected out of the pupal case (for pupa morphology). All pupa images were taken on an Olympus SXZ16 stereomicroscope coupled to an Olympus DP72 digital camera with DP2-BSW software.

Starvation assay

Second instar larvae of each genotype were moved to a new vial containing 4% sucrose as a nutrient source. The number of surviving larvae was counted 8 h later. 4E-BP and ATF4 mRNA levels in surviving larvae were assessed using qPCR.

Retinal degeneration

The assays were done in the cn.bw−/− background to eliminate eye pigments. The integrity of the photoreceptors was assessed through green fluorescent pseudopupils as seen by the Rh1-GFP transgene. Live flies for each genotype were monitored over 30 days and data were analyzed by log-rank test using the Kaplan–Meier method to determine significance.

Structure-based identification of the D109 mutation

Analysis of the contact interface between RNA and PUA domains from several crystallographic structures (PDB 3LWP, 3LWR, and 3HAX), as well as the lower resolution cryoEM structure of human eIF2D bound to tRNA (5OA3) identified over ten PUA amino acid side chains contacting tRNA. We prioritized human D111 since the equivalent amino acid in the PUA domain of the human DKC1 protein has an established human genetic phenotype of causing the disease dyskeratosis congenita, reasoning that this established bioactivity in vivo would make it more likely to have a tRNA-specific expression phenotype in our experimental system. In order to confirm the 3D structural equivalence of Drosophila eIF2D D109 with human eIF2D D111, homology models of the Drosophila eIF2D PUA domain were made using previously described approaches61 using all of the PUA crystallographic and cryoEM templates and this amino acid side chain superimposed to observe that human D111 and Drosophila D109 occupied the same location in the structure.

Immunostaining

Fat bodies or eye disks from wandering 3rd instar larvae were dissected in 1× PBS and fixed in 4% PFA, 1× PBS for 20 min. Tissues were then washed 1x with 1× PBS and permeabilized in 0.2% Triton-X 100, 1× PBS (PBST) for 20 min. The tissues were stained in PBST with primary antibodies at the indicated dilution and Alexafluor-conjugated secondary antibodies at 1:500 for 1.5 h, washed 3× with PBST and mounted with DAPI. All incubations were carried out at room temperature with mild agitation. Primary antibodies: Rabbit anti-GFP (1:500, Life Technologies A6455), Rabbit anti-RFP (1:250, Thermo Fisher R10367), Guinea pig anti-ATF4 (1:1054), Mouse anti-Rh1 (1:500, DSHB 4C5), Rabbit anti-PeIF2α (1:500, Cell Signaling 9721S).

Western blotting

Cell lysates were prepared in 1% NP-40, 1× TBS on ice for 10 min and debris was cleared by centrifuging at 16,000×g for 10 min, 4 °C. Ten larval heads were dissected in 1× PBS and lysed similarly in 100 μl buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, protease inhibitor cocktail [Roche], 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS. Lysates were analyzed on denaturing SDS-PAGE followed by western blotting with primary antibodies at indicated dilutions at 4 °C overnight and HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:1000, Jackson Immunolabs) for 1 h at room temperature.

Primary antibodies: Guinea pig anti-eIF2D (1:500, raised against GST-tagged full length recombinant Drosophila eIF2D expressed using pet23a vector), Guinea Pig anti-Drosophila ATF424, Rabbit anti-ATF4 (1:200, SCBT sc-200), Rabbit anti-PeIF2α (1:500, Abcam ab32157), Rabbit anti-eIF2α (1:2000, Abcam ab26197), Mouse anti-actin (1:5000, Millipore), Rabbit anti-GFP (1:1000, Life Technologies A6455).

Immunoprecipitation assays

Larval lysates were prepared from 25 larvae as described above in RNAse-free lysis buffer containing 20U/ml of SUPERase-In RNAse inhibitor (Thermo Fisher). The lysates were incubated with anti-eIF2D antibody (1:100) for 2 h at 4 °C on an end-over-end rotator. 10 μl of Protein A Dynabeads (Thermo Fisher, prewashed 3× with lysis buffer) were added to the antibody:lysate mixture and incubated further for 2 h at 4 °C. Beads were washed with 1 ml ice-cold lysis buffer and eluted in 20 μl 1% SDS by boiling at 95 °C for 5 min. Eluates were analyzed on a 15% UREA-TBE gel for nucleic acid species.

For the nuclease-sensitivity assay, eluates were diluted tenfold in distilled water and DNase buffer (provided with TURBO DNase kit, Thermofisher). and digested with 1 μl TURBO DNase or RNase I (NEB) for 1 h at 37 °C. Digested eluates were analyzed on 15% UREA-TBE gel.

Cell culture

WT and ΔeIF2D HAP1 cells (Horizon Discovery, HZGHC002651c012) were cultured according to supplier’s protocol. Cells were transfected with negative control scrambled siRNA (Qiagen) or DENR siRNA (Dharmacon, L-012614-00-0005) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Human eIF2D (Dharmacon, 4339127) was subcloned into the EcoRI and XbaI sites of pcDNA3.1 and cotransfected with siRNA.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (supported by NIH P40OD018537), the Vienna Drosophila Stock Center, and the Harvard Exelixis collection for fly lines used in this project. We thank all the members of the Ryoo laboratory, Drs. Jessica Treisman, Erika Bach, Christine Vogel and Justin Rendleman for critical discussions. Comments from Drs. David Ron and Marc Amoyel helped improve the manuscript. We thank Ishwar Navin for his aid in generating the eIF2D antibody. This work was supported by NIH grants R01EY020866 and R01GM125954 to H.D.R., DP2OD004631 and the Irma T. Hirschl/Monique Weill Caulier Research Award to T.C., R01GM123204 to A.B., the American Heart Association fellowship (17POST33420032) and K99/R00 pathway to Independence award (1K99EY029013) to D.V.

Source data

Author contributions

D.V. and H.D.R. conceived the project, designed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. S.N. and A.B. performed the developmental analysis for eIF2D and DENR mutants. L.L. and T.C. performed the Drosophila eIF2D structural modeling. D.V. performed all other experiments. A.Y. provided technical assistance for all fly experiments. B.B. generated the leaderless UAS-crcleaderless transgenic fly.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. All fluorescent microscopy images (Figs. 1b–e, 2c, 3b, 4c–f and Supplementary Figs. 1c, 2a, 4a, 5) and confocal microscopy images (Figs. 1f–i, 2d–i, 3c–j, 6a–i and Supplementary Figs. 1d, e, 2b–e, 4b–d, 6b, c, 7a–c) presented in the manuscript have associated raw images, and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Paul Lasko, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-020-18453-1.

References

- 1.Delépine M, et al. EIF2AK3, encoding translation initiation factor 2-alpha kinase 3, is mutated in patients with Wolcott-Rallison syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:406–409. doi: 10.1038/78085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harding HP, et al. Diabetes mellitus and exocrine pancreatic dysfunction in perk-/- mice reveals a role for translational control in secretory cell survival. Mol. Cell. 2001;7:1153–1163. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00264-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang P, et al. The PERK eukaryotic initiation factor 2 alpha kinase is required for the development of the skeletal system, postnatal growth, and the function and viability of the pancreas. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:3864–3874. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.11.3864-3874.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Back SH, et al. Translation attenuation through eIF2alpha phosphorylation prevents oxidative stress and maintains the differentiated state in beta cells. Cell Metab. 2009;10:13–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iida K, Li Y, McGrath BC, Frank A, Cavener DR. PERK eIF2 alpha kinase is required to regulate the viability of the exocrine pancreas in mice. BMC Cell Biol. 2007;8:38. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-8-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma T, et al. Suppression of eIF2α kinases alleviates Alzheimer’s disease-related plasticity and memory deficits. Nat. Neurosci. 2013;16:1299–1305. doi: 10.1038/nn.3486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Höglinger GU, et al. Identification of common variants influencing risk of the tauopathy progressive supranuclear palsy. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:699–705. doi: 10.1038/ng.859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yuan SH, et al. Tauopathy-associated PERK alleles are functional hypomorphs that increase neuronal vulnerability to ER stress. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018;27:3951–3963. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddy297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ye J, et al. The GCN2-ATF4 pathway is critical for tumour cell survival and proliferation in response to nutrient deprivation. EMBO J. 2010;29:2082–2096. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tameire F, et al. ATF4 couples MYC-dependent translational activity to bioenergetic demands during tumour progression. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019;21:889–899. doi: 10.1038/s41556-019-0347-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng Y-X, et al. Cancer-specific PERK signaling drives invasion and metastasis through CREB3L1. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:1079. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01052-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dever TE, et al. Phosphorylation of initiation factor 2 alpha by protein kinase GCN2 mediates gene-specific translational control of GCN4 in yeast. Cell. 1992;68:585–596. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90193-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berry MJ, Knutson GS, Lasky SR, Munemitsu SM, Samuel CE. Mechanism of interferon action. Purification and substrate specificities of the double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase from untreated and interferon-treated mouse fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:11240–11247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen J-J, London IM. Regulation of protein synthesis by heme-regulated eIF-2α kinase. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1995;20:105–108. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)88975-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shi Y, et al. Identification and characterization of pancreatic eukaryotic initiation factor 2 alpha-subunit kinase, PEK, involved in translational control. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:7499–7509. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.12.7499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harding HP, Zhang Y, Ron D. Protein translation and folding are coupled by an endoplasmic-reticulum-resident kinase. Nature. 1999;397:271–274. doi: 10.1038/16729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harding HP, et al. Regulated translation initiation controls stress-induced gene expression in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell. 2000;6:1099–1108. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00108-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harding HP, et al. An integrated stress response regulates amino acid metabolism and resistance to oxidative stress. Mol. Cell. 2003;11:619–633. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vattem KM, Wek RC. Reinitiation involving upstream ORFs regulates ATF4 mRNA translation in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:11269–11274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400541101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ingolia NT, Ghaemmaghami S, Newman JRS, Weissman JS. Genome-wide analysis in vivo of translation with nucleotide resolution using ribosome profiling. Science. 2009;324:218–223. doi: 10.1126/science.1168978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hinnebusch AG, Ivanov IP, Sonenberg N. Translational control by 5′-untranslated regions of eukaryotic mRNAs. Science. 2016;352:1413–1416. doi: 10.1126/science.aad9868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu PD, Harding HP, Ron D. Translation reinitiation at alternative open reading frames regulates gene expression in an integrated stress response. J. Cell Biol. 2004;167:27–33. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200408003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamaguchi S, et al. ATF4-mediated induction of 4E-BP1 contributes to pancreatic beta cell survival under endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Metab. 2008;7:269–276. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kang M-J, et al. 4E-BP is a target of the GCN2-ATF4 pathway during Drosophila development and aging. J. Cell Biol. 2017;216:115–129. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201511073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vasudevan D, et al. The GCN2-ATF4 signaling pathway induces 4E-BP to bias translation and boost antimicrobial peptide synthesis in response to bacterial infection. Cell Rep. 2017;21:2039–2047. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.10.096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malzer E, et al. The integrated stress response regulates BMP signalling through effects on translation. BMC Biol. 2018;16:34. doi: 10.1186/s12915-018-0503-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Armstrong AR, Laws KM, Drummond-Barbosa D. Adipocyte amino acid sensing controls adult germline stem cell number via the amino acid response pathway and independently of Target of Rapamycin signaling in Drosophila. Development. 2014;141:4479–4488. doi: 10.1242/dev.116467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bjordal M, Arquier N, Kniazeff J, Pin JP, Léopold P. Sensing of amino acids in a dopaminergic circuitry promotes rejection of an incomplete diet in Drosophila. Cell. 2014;156:510–521. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang L, Ryoo HD, Qi Y, Jasper H. PERK limits drosophila lifespan by promoting intestinal stem cell proliferation in response to ER stress. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005220. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hinnebusch AG. Evidence for translational regulation of the activator of general amino acid control in yeast. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1984;81:6442–6446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.20.6442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Skabkin MA, et al. Activities of Ligatin and MCT-1/DENR in eukaryotic translation initiation and ribosomal recycling. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1787–1801. doi: 10.1101/gad.1957510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dmitriev SE, et al. GTP-independent tRNA delivery to the ribosomal P-site by a novel eukaryotic translation factor. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:26779–26787. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.119693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vaidya AT, Lomakin IB, Joseph NN, Dmitriev SE, Steitz TA. Crystal structure of the C-terminal domain of human eIF2D and its implications on eukaryotic translation initiation. J. Mol. Biol. 2017;429:2765–2771. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2017.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weisser, M. et al. Structural and functional insights into human re-initiation complexes. Mol. Cell67, 447–456 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Schleich S, et al. DENR-MCT-1 promotes translation re-initiation downstream of uORFs to control tissue growth. Nature. 2014;512:208–212. doi: 10.1038/nature13401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lomakin, I. B. et al. Crystal structure of the human ribosome in complex with DENR-MCT-1. Cell Rep.20, 521–528 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Lomakin IB, Dmitriev SE, Steitz TA. Crystal structure of the DENR-MCT-1 complex revealed zinc-binding site essential for heterodimer formation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:528–533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1809688116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fristrom JW. Development of the morphological mutant cryptocephal of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1965;52:297–318. doi: 10.1093/genetics/52.2.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fletcher JC, Burtis KC, Hogness DS, Thummel CS. The Drosophila E74 gene is required for metamorphosis and plays a role in the polytene chromosome puffing response to ecdysone. Development. 1995;121:1455–1465. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.5.1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fletcher JC, Thummel CS. The ecdysone-inducible Broad-complex and E74 early genes interact to regulate target gene transcription and Drosophila metamorphosis. Genetics. 1995;141:1025–1035. doi: 10.1093/genetics/141.3.1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beckstead R, et al. Bonus, a Drosophila homolog of TIF1 proteins, interacts with nuclear receptors and can inhibit betaFTZ-F1-dependent transcription. Mol. Cell. 2001;7:753–765. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00220-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pecasse F, Beck Y, Ruiz C, Richards G. Krüppel-homolog, a stage-specific modulator of the prepupal ecdysone response, is essential for Drosophila metamorphosis. Dev. Biol. 2000;221:53–67. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ritter AR, Beckstead RB. Sox14 is required for transcriptional and developmental responses to 20-hydroxyecdysone at the onset of drosophila metamorphosis. Dev. Dyn. 2010;239:2685–2694. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Castelo-Szekely V, et al. Charting DENR-dependent translation reinitiation uncovers predictive uORF features and links to circadian timekeeping via Clock. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:5193–5209. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schleich S, Acevedo JM, Clemm von Hohenberg K, Teleman AA. Identification of transcripts with short stuORFs as targets for DENR•MCTS1-dependent translation in human cells. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:3722. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03949-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Colley NJ, Cassill JA, Baker EK, Zuker CS. Defective intracellular transport is the molecular basis of rhodopsin-dependent dominant retinal degeneration. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:3070–3074. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.3070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kurada P, O’Tousa JE. Retinal degeneration caused by dominant rhodopsin mutations in Drosophila. Neuron. 1995;14:571–579. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90313-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dryja TP, et al. A point mutation of the rhodopsin gene in one form of retinitis pigmentosa. Nature. 1990;343:364–366. doi: 10.1038/343364a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sung CH, et al. Rhodopsin mutations in autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88:6481–6485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.15.6481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kang M-J, Ryoo HD. Suppression of retinal degeneration in Drosophila by stimulation of ER-associated degradation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:17043–17048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905566106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ryoo HD, Domingos PM, Kang M-J, Steller H. Unfolded protein response in a Drosophila model for retinal degeneration. EMBO J. 2007;26:242–252. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kang M-J, Chung J, Ryoo HD. CDK5 and MEKK1 mediate pro-apoptotic signalling following endoplasmic reticulum stress in an autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa model. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012;14:409–415. doi: 10.1038/ncb2447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang H-W, Brown B, Chung J, Domingos PM, Ryoo HD. Highroad is a carboxypetidase induced by retinoids to clear mutant rhodopsin-1 in drosophila retinitis pigmentosa models. Cell Rep. 2018;22:1384–1391. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kang K, Ryoo HD, Park J-E, Yoon J-H, Kang M-J. A drosophila reporter for the translational activation of ATF4 marks stressed cells during development. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0126795. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dey S, et al. Both transcriptional regulation and translational control of ATF4 are central to the integrated stress response. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:33165–33174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.167213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Skabkin MA, Skabkina OV, Hellen CUT, Pestova TV. Reinitiation and other unconventional posttermination events during eukaryotic translation. Mol. Cell. 2013;51:249–264. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bohlen et al. DENR promotes translation reinitiation via ribosome recycling to drive expression of oncogenes including ATF4. Nature Communications. 10.1038/s41467-020-18452-2 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Young, D. J. et al. Tma64/eIF2D, Tma20/MCT-1, and Tma22/DENR recycle post-termination 40S subunits in vivo. Mol. Cell71, 761–774 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Makeeva DS, et al. Translatome and transcriptome analysis of TMA20 (MCT-1) and TMA64 (eIF2D) knockout yeast strains. Data Brief. 2019;23:103701. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2019.103701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bainbridge SP, Bownes M. Staging the metamorphosis of Drosophila melanogaster. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 1981;66:57–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Martinez-Ortiz W, Cardozo TJ. An improved method for modeling voltage-gated ion channels at atomic accuracy applied to human Cav channels. Cell Rep. 2018;23:1399–1408. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. All fluorescent microscopy images (Figs. 1b–e, 2c, 3b, 4c–f and Supplementary Figs. 1c, 2a, 4a, 5) and confocal microscopy images (Figs. 1f–i, 2d–i, 3c–j, 6a–i and Supplementary Figs. 1d, e, 2b–e, 4b–d, 6b, c, 7a–c) presented in the manuscript have associated raw images, and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.