Abstract

Psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) are diagnosed in approximately 30% of patients referred to tertiary care epilepsy centers. Little is known about the molecular pathology of PNES, much less about possible underlying genetic factors. We generated whole-exome sequencing and whole-genome genotyping data to identify rare, pathogenic (P) or likely pathogenic (LP) variants in 102 individuals with PNES and 448 individuals with focal (FE) or generalized (GE) epilepsy. Variants were classified for all individuals based on the ACMG-AMP 2015 guidelines. For research purposes only, we considered genes associated with neurological or psychiatric disorders as candidate genes for PNES. We observe in this first genetic investigation of PNES that six (5.88%) individuals with PNES without coexistent epilepsy carry P/LP variants (deletions at 10q11.22-q11.23, 10q23.1-q23.2, distal 16p11.2, and 17p13.3, and nonsynonymous variants in NSD1 and GABRA5). Notably, the burden of P/LP variants among the individuals with PNES was similar and not significantly different to the burden observed in the individuals with FE (3.05%) or GE (1.82%) (PNES vs. FE vs. GE (3 × 2 χ2), P = 0.30; PNES vs. epilepsy (2 × 2 χ2), P = 0.14). The presence of variants in genes associated with monogenic forms of neurological and psychiatric disorders in individuals with PNES shows that genetic factors are likely to play a role in PNES or its comorbidities in a subset of individuals. Future large-scale genetic research studies are needed to further corroborate these interesting findings in PNES.

Subject terms: Disease genetics, Diagnostic markers, Neurological disorders, Psychiatric disorders, Next-generation sequencing, Genetic predisposition to disease

Introduction

PNES is considered a multifactorial biopsychosocial disorder1, that can coexist with epilepsy2, and which has a broad range of comorbid neurological and psychiatric disorders. Major depression and anxiety disorders are the most common psychiatric comorbidities, both reported in ~ 50% of all individuals with PNES3,4. PNES, epilepsy, and psychiatric disorders cluster in families with a positive family history of psychiatric disorders in 7–22% of all individuals with PNES5,6 and a positive family history of epilepsy in 7–48% of all individuals with PNES5–7. However, the upper ranges of the estimates for a positive family history of psychiatric disorders and epilepsy are driven by the inclusion of individuals with PNES and comorbid epilepsy. Such individuals were not routinely excluded in the majority of all PNES studies.

Recent results indicate that some genetic risk factors are shared between common neurological and psychiatric disorders (including epilepsy, depression, anxiety, and neuroticism)8,9 and may explain part of the observed phenotypic overlap10. Widespread pleiotropy for genes associated with Mendelian forms of neurological and psychiatric disorders suggests that these disorders are the response of a complex neurologic network, which is altered in several domains of function. For example, individuals affected by pathogenic variants in well-established epilepsy genes usually have additional neurological or psychiatric comorbidities11. While recent success in genetic studies has led to the identification of disease-associated genetic factors for virtually all disorders comorbid with PNES (i.e., anxiety, bipolar disorder, depression, epilepsy, intellectual disability, migraine, mood disorders, personality disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, and schizophrenia), a genetic basis of PNES has been speculated12, but never formally investigated.

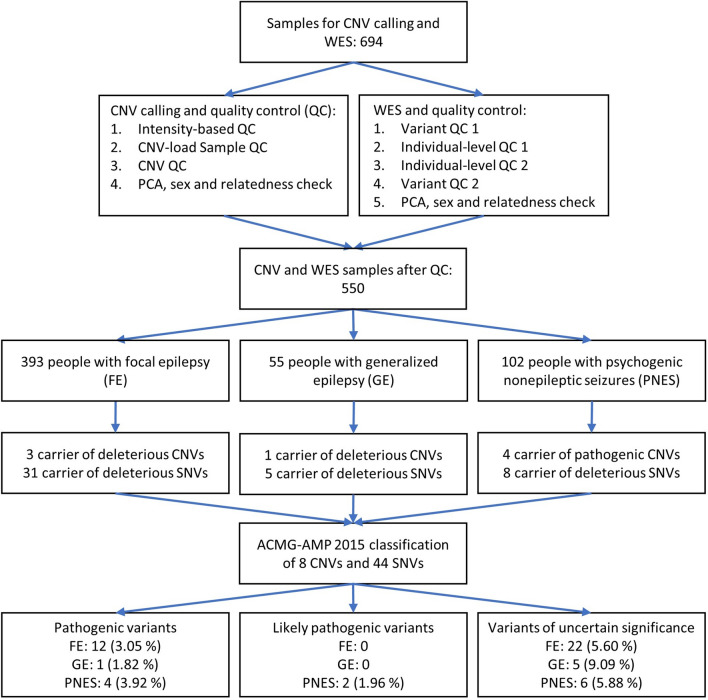

To characterize genetically the heterogeneous phenotypic spectrum of individuals referred to a tertiary care center—we genotyped and sequenced 550 individuals with PNES or epilepsy, from the Cleveland Clinic Epilepsy Center, while excluding individuals with both PNES and epilepsy. We then selected all copy-number (CNVs) and single nucleotide variants (SNVs) with strong computational support for a deleterious effect on the involved gene/s and classified them according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology (ACMG-AMP) 2015 guidelines13. The guidelines require an established gene to phenotype association as one criterion for pathogenicity prediction. Because the genetic basis of PNES is unknown and no established PNES genes exist, we applied the ACMG-AMP guidelines for research purposes only and considered genes associated with neurological or psychiatric disorders as candidate genes for PNES. Our overall study design is presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Study design and execution. SNV: single nucleotide variant, CNV: copy number variant, WES: whole-exome sequencing, QC: quality control, PCA: principal component analysis, FE: focal epilepsy, GE: generalized epilepsy, PNES: psychogenic nonepileptic seizures.

Results

Cohort and analysis overview

We generated genotyping as well as exome data for 694 individuals ascertained through the Epilepsy Biorepository of the Cleveland Clinic Epilepsy Center. The data was used to perform genome-wide CNV and whole-exome SNV analyses. After data quality control, 550 individuals with epilepsy or PNES were included in the downstream analyses (Table 1). The most prevalent diagnosis was focal epilepsy (FE, N = 393, 71.5%) followed by psychogenic nonepileptic seizures without epilepsy (PNES, N = 102, 18.5%), and generalized epilepsy (GE, N = 55, 10%).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical features of the 550 tertiary care epilepsy center patients.

| PNES | FE | GE | F/χ2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 102 | N = 393 | N = 55 | |||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |||

| Age | 42.5 (14.3) | 39.7 (14.8) | 38.2 (15.0) | 2.03 | 0.133 |

| Education | 13.7 (2.4) | 13.9 (2.5) | 14.1 (2.2) | 0.51 | 0.602 |

| PNES | FE | GE | F/χ2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 102 | N = 393 | N = 55 | |||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |||

| Sex (female) | 76 (74.5%) | 183 (46.6%) | 31 (56.4%) | 25.7 | < 0.001 |

| Comorbidities and family history | |||||

| Depression | 64 (62.7%) | 164 (41.7%) | 30 (54.5%) | 15.8 | < 0.001 |

| Anxiety | 54 (52.9%) | 106 (27.0%) | 25 (45.5%) | 28.3 | < 0.001 |

| Bipolar disorder | 11 (10.8%) | 1 (1.8%) | 1 (1.8%) | 20.2 | < 0.001 |

| PTSD | 14 (13.7) | 5 (1.3%) | 1 (1.8%) | 36.4 | < 0.001 |

| Chronic pain | 18 (17.6%) | 23 (5.9%) | 4 (7.3%) | 15.1 | 0.001 |

| Family history of seizures | 32 (31.4%) | 78 (19.8%) | 20 (36.4%) | 11.4 | 0.003 |

PNES: psychogenic nonepileptic seizures, FE: focal epilepsy, GE: generalized epilepsy, M: sample mean, SD: standard deviation, F/χ2: test statistic, P: P-value, N: number of individuals, PTSD: post-traumatic stress disorder.

Individuals in this study were 40 years old on average (standard deviation, SD = 15) and completed approximately 14 years of education (SD = 2). Fifty-three percent of the cohort was female and all of genetically defined European ancestry. The three study groups were well matched in terms of age and education. There were more females in the PNES group (75%) than in the epilepsy groups (FE: 47%, GE: 56%). The PNES group showed the highest proportion of individuals with comorbid psychiatric disorders or a history of chronic pain compared to the two epilepsy groups (Table 1). Individuals with FE were less likely to have a family history of epilepsy, defined as seizures in a first- or second-degree relative than those with GE (χ2 = 7.70, P = 0.006) or PNES (χ2 = 6.22, P = 0.013). However, the family history of seizures was similar between individuals with GE and PNES (χ2 = 0.402, P = 0.526). The percentage of individuals with comorbidities and a family history of seizures was similar between females and males with PNES (Supplementary Table 4).

Individuals with PNES carry pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants similar to individuals with epilepsy

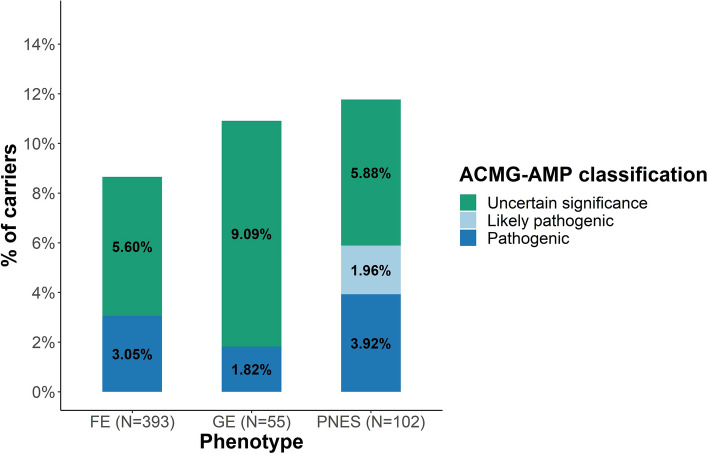

Rare genetic variants are well-established risk factors associated with epilepsy14. We first examined if individuals with PNES carry deleterious genetic variants, as classified by state-of-the-art in silico prediction methods. The results were compared to the control group of 448 individuals with epilepsy from the same epilepsy clinic. Identified potential deleterious insertion/deletion polymorphisms (indels, N = 56) did not survive our strict criteria for the visual inspection of the reads supporting each variant and were excluded from subsequent analyses. After data quality control and stringent variant filtering, we identified deleterious variants in 8.65% of all individuals with FE (N = 34, Supplementary Table 1), 10.91% of all individuals with GE (N = 6, Supplementary Table 2), and in 11.76% of all individuals with PNES (N = 12, Table 2) (Fig. 2). The proportions of individuals carrying only a specific variant type (single nucleotide or copy number variants) are displayed in Supplementary Figures 1 and 2. The deleterious variant burden across the three disorder types was not significantly different (PNES vs. FE vs. GE, two-tailed 3 × 2 χ2, P = 0.59; PNES vs. epilepsy, two-tailed 2 × 2 χ2, P = 0.38).

Table 2.

Pathogenic, likely pathogenic, and variants of uncertain significance in individuals with PNES.

| ID | Variant type | Gene/s | Associated neurological/psychiatric disorder | ACMG-AMP classification | CytoBand | Chr | Start GRCh37 | Stop GRCh37 | Consequence/nucleotide change/affected exon | Mis_z | pLI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PNES1 | 1.58 Mb deletion | 7 genes | Epilepsy | Pathogenic | 10q23.1-q23.2 | 10 | 87,136,787 | 88,718,934 | CN loss | – | – |

| PNES2 | 218 Kb deletion | 9 genes | Epilepsy | Pathogenic | distal 16p11.2 | 16 | 28,826,049 | 29,044,745 | CN loss | – | – |

| PNES3 | 229 Kb deletion | PAFAH1B1, METTL16 | Epilepsy | Pathogenic | 17p13.3 | 17 | 2,341,350 | 2,570,479 | CN loss | – | – |

| PNES4 | Nonsynonymous SNV | NSD1 | Neurological/psychiatric | Likely pathogenic | 5q35.3 | 5 | 176,720,953 | 176,720,953 | p.Lys1926Arg (exon 23 out of 23) | 3.70 | 1.00 |

| PNES5 | 4.91 Mb Deletion | 39 genes | Neurological/psychiatric | Pathogenic | 10q11.22-q11.23 | 10 | 46,943,377 | 51,856,375 | CN loss | – | – |

| PNES6 | Nonsynonymous SNV | GABRA5 | Neurological/psychiatric | Likely pathogenic | 15q12 | 15 | 27,188,485 | 27,188,485 | p.Ala334Gly (exon 10 out of 11) | 3.31 | 0.88 |

| PNES7 | Stopgain SNV | LHX9 | NA | Uncertain significance | 1q31.3 | 1 | 197,896,819 | 197,896,819 | p.Gln269Ter (exon 4 out of 5)a | 1.13 | 0.98 |

| PNES8 | Nonsynonymous SNV | MAPKAPK2 | NA | Uncertain significance | 1q32.1 | 1 | 206,904,045 | 206,904,045 | p.Leu235Pro (exon 6 out of 10) | 3.10 | 1.00 |

| PNES9 | Splicing SNV | CAMKV | NA | Uncertain significance | 3p21.31 | 3 | 49,899,726 | 49,899,726 | c.95+1G>A (exon 2 out of 11) | 3.39 | 1.00 |

| PNES10 | Stopgain SNV | GAPVD1 | NA | Uncertain significance | 9q33.3 | 9 | 128,118,066 | 128,118,066 | p.Arg1319Ter (exon 25 out of 28) b | 2.75 | 1.00 |

| PNES11 | Nonsynonymous SNV | PRPF8 | NA | Uncertain significance | 17p13.3 | 17 | 1,579,337 | 1,579,337 | p.Arg855Pro (exon 18 out of 43) | 8.55 | 1.00 |

| PNES12 | Splicing SNV | MYH9 | NA | Uncertain significance | 22q12.3 | 22 | 36,717,867 | 36,717,867 | c.706-1G>C (exon 7 out of 41) | 3.67 | 1.00 |

Chr: chromosome, GRCh37: Genome Reference Consortium Human Build 37, Mis_z: Z-score for missense variant intolerance of a gene, pLI: probability for the loss-of-function variant intolerance of a gene, Mb: mega base pairs, Kb: kilo base pairs, CN: copy number.

aExon numbers based on transcript NM_020204.

bExon numbers based on transcript NM_001282680.

Figure 2.

Burden of pathogenic and likely pathogenic SNVs and CNVs in individuals with FE, GE, or PNES. Each stacked bar plot represents the total percentage of carriers of (i) pathogenic variants, highlighted in blue; (ii) likely pathogenic variants, highlighted in light blue; and (iii) variants of uncertain significance, highlighted in green. The classification of the variants in the individuals with PNES was performed for research purposes only. FE: focal epilepsy, GE: generalized epilepsy, PNES: psychogenic nonepileptic seizures, N: number of individuals with each phenotype.

Next, we classified all deleterious variants according to the ACMG-AMP 2015 guidelines to determine if individuals with PNES carry ACMG-AMP-classified pathogenic (P) or likely pathogenic (LP) genetic variants in genes associated with neurological disorders, and/or psychiatric disorders, including epilepsy. We found P/LP variants in 3.05% of all individuals with FE (N = 12, Supplementary Table 1), 1.82% of all individuals with GE (N = 1, Supplementary Table 2), and in 5.88% of all individuals with PNES (N = 6, Table 2) (Fig. 2). The P/LP variant burden across the three disorder types was not significantly different (PNES vs. FE vs. GE, two-tailed 3 × 2 χ2, P = 0.30; PNES vs. epilepsy, two-tailed 2 × 2 χ2, P = 0.14). We also identified ACMG-AMG variants of uncertain significance (VUS) in 5.60% of all individuals with FE (N = 22, Supplementary Table 1), 9.09% of all individuals with GE (N = 5, Supplementary Table 2), and in 5.88% of all individuals with PNES (N = 6, Table 2) (Fig. 2). Out of all six P/LP variant carriers with PNES, one (16.7%) reported a family history of seizures, and two (33.3%) a family history of psychiatric disorders (anxiety, mood disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder).

Detailed evaluation of the deleterious variants found in individuals with PNES

We are unaware of any studies to date that have conducted genetic testing in individuals with PNES. Subsequently, there are no genes or variants that have been associated with PNES. Variant pathogenicity classification requires an established gene-phenotype association13. For research purposes, we classified variants in our sample of individuals with PNES as if the variants would have been identified in individuals with neurologic or psychiatric disorders. As a consequence, variants in genes associated with neuropsychiatric disorders could qualify for pathogenicity if additional variant level criteria were fulfilled.

The phenotypic characteristics of all deleterious variant carriers with PNES are listed in Table 3 and Supplementary Tables 5 and 6. Six individuals with PNES were affected by P/LP variants (three males and three females). These variants included four CNVs and two missense variants (Table 2). Three out of the six P/LP variants were found to be known epilepsy-associated CNVs (deletions at 10q23.1-q23.2, distal 16p11.2, and 17p13.3). Deletions at 10q23.1-q23.2 are associated with complex genetic neurodevelopmental syndromes15. Our patient with PNES and the 10q23.1-q23.2 deletion had normal neurodevelopment, an onset of PNES at 33 years of age, a history of migraine, chronic pain and mood disorder, and no history of febrile seizures or family history of seizures.

Table 3.

Phenotypic characteristics of individuals with PNES and deleterious genetic variants.

| ID | Sex | Identified variant (ACMG-AMP classification) | Age | Age at PNES onset | Cognition/neuro exam | MRI | Febrile seizures | Medical comorbidities | Psychiatric comorbidities | FH of seizures | FH of psychiatric disease |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PNES1 | Male | Pathogenic | 33 | 33 | Normal/normal | Normal | No | Migraine, chronic pain | Mood disorder | No | No |

| PNES2 | Male | Pathogenic | 59 | 55 | Normal/normal | Normal | No | HTN, DM, HPL, COPD, OSA, CAD/CHF, CKD | None | No | No |

| PNES3 | Female | Pathogenic | 33 | 30 | Normal/normal | Unknown | No | None | Anxiety, PTSD | No | Yes—PTSD, anxiety |

| PNES4 | Male | Likely pathogenic | 58 | 12 | Normal/normal | Normal | No | HTN, OSA | Mood disorder | No | No |

| PNES5 | Female | Pathogenic | 50 | 50 | Normal/normal | Normal | No | Hypothyroidism | Mood disorder, anxiety | Yes—aunt | Yes—mood disorder |

| PNES6 | Female | Likely pathogenic | 45 | 40 | Normal/normal | Normal | No | HTN, HPL, CAD, CVD | Mood disorder, anxiety, PTSD | No | No |

| PNES7 | Female | Uncertain significance | 39 | 34 | Normal/normal | Normal | No | Migraine, HTN, DM, OSA, PCOS, optic neuritis | Mood disorder, anxiety | No | Yes—mood disorder, OCD |

| PNES8 | Female | Uncertain significance | 50 | 50 | Normal/normal | Normal | No | Migraine, HPL | Anxiety | No | No |

| PNES9 | Female | Uncertain significance | 48 | 28 | Normal/normal | Mild chronic microvascular disease | No | DM, OSA, IBS, CVD | Mood disorder, anxiety | No | No |

| PNES10 | Female | Uncertain significance | 43 | 7 | Normal/normal | Mild chronic microvascular disease | No | Migraine, DM, CKD, OSA, hypothyroidism | Mood disorder, anxiety | Yes—MGM | No |

| PNES11 | Female | Uncertain significance | 26 | 15 | Normal/normal | Normal | No | Migraine, chronic pain | Mood disorder, anxiety, PTSD | Yes—MGF | Yes—mood disorder, anxiety |

| PNES12 | Male | Uncertain significance | 53 | 51 | Normal/normal | Normal | No | None | Mood disorder | Yes—mother | No |

HTN: hypertension, DM: diabetes mellitus, HPL: hyperlipidemia, COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, CAD: coronary artery disease, CHF: congestive heart failure, CKD: chronic kidney disease, OSA: obstructive sleep apnea, PTSD: post-traumatic stress disorder, Mood Disorder: depression or bipolar disorder, CVD: cerebrovascular disease, PGF: paternal grandfather, PCOS: polycystic ovarian syndrome, OCD: obsessive–compulsive disorder, MGF: maternal grandfather, MGM: maternal grandmother, IBS: irritable bowel syndrome.

Deletions and duplications at distal 16p11.2 locus are associated with epilepsy, autism spectrum disorder, schizophrenia, lower IQ, and subcortical brain abnormalities16. Our patient with PNES and the distal 16p11.2 deletion had normal neurodevelopment, an onset of PNES at 55 years of age, and no history of febrile seizures or a family history of seizures. The third epilepsy-associated variant in PNES was a PAFAH1B1 gene disrupting 17p13.3 deletion. PAFAH1B1 is a well-established gene for lissencephaly with seizures as the core symptom of this disorder17. The 17p13.3 deletion also disrupts the gene METTL16. However, METTL16 is not associated with any disease and is unlikely to play a role in PNES causation, because METTL16 is known to tolerate missense (missense Z-score = 2.35) and loss-of-function variants (pLI = 0.61)18. Our patient with PNES and deletion of PAFAH1B1 had normal neurodevelopment, an onset of PNES at 30 years of age, a history of anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and no history of febrile seizures or family history of seizures.

The next three P/LP variants (one P, two LP) were identified in two genes and at a chromosomal position, each implicated in neurological or psychiatric disorders with or without seizures (NSD1, 10q11.22-q11.23 deletion, and GABRA5; Table 2). Heterozygous mutations in the NSD1 gene are associated with Sotos syndrome (autosomal dominant)19. Sotos syndrome is characterized by distinctive facial features, intellectual disability (ID), and overgrowth or macrocephaly, and seizures are reported in 9–50% of cases20. Our patient with PNES and an NSD1 mutation had normal neurodevelopment, an onset of PNES at 12 years of age, a history of mood disorder, and no history of febrile seizures or family history of seizures. Deletions and duplications at 10q11.22-q11.23 are associated with developmental delay or ID21. Our patient with PNES and the 10q11.22-q11.23 deletion had normal neurodevelopment, an onset of PNES at 50 years of age, a history of mood disorder and anxiety, no history of febrile seizures, and a suggestive family history of seizures (affected aunt). Finally, GABRA5 is a candidate gene for epilepsy and developmental delay22, which has not yet been statistically associated with epilepsy through an exome-wide cohort screen. Our patient with PNES and a GABRA5 mutation had normal neurodevelopment, an onset of PNES at 40 years of age, a history of mood disorder, anxiety, and PTSD, and no history of febrile seizures or family history of seizures.

Out of the six identified VUS, four were identified in genes with a potential role in brain function (LHX9, MAPKAPK2, CAMKV, and MYH9). Expression of LHX9 was shown to be repressed by kainic acid-induced seizures23, while MAPKAPK2 expression was induced24. CAMKV encodes for a synaptic protein crucial for dendritic spine maintenance25. Heterozygous mutations in MYH9 are associated with a spectrum of autosomal dominant thrombocytopenias26. The most devastating consequence of thrombocytopenia is intracranial hemorrhage, and one case with recurrent seizures related to intracranial hemorrhage was recently described in the literature27.

Discussion

We generated whole-exome sequencing and whole-genome genotyping data to identify rare, P/LP variants in a cohort of 550 individuals with PNES or epilepsy (focal or generalized). This study represents the first genetic investigation of PNES. We used the ACMG-AMP 2015 guidelines13 to classify variants from the perspective of Mendelian forms of neurological or psychiatric disorders, including epilepsy. We show that P/LP variants in genes implicated in a broad range of neurological and psychiatric disorders are found in individuals with PNES evaluated in a tertiary care epilepsy center. Interestingly, we did not observe a significant difference in the burden of P/LP variants, when comparing individuals with PNES without coexistent epilepsy to individuals with epilepsy. The observed variant burden is not surprising for the epilepsies, and elevated burdens of CNVs or SNVs have been observed in several large-scale studies that compared individuals with epilepsy against population controls11,14,28,29. In contrast, genetic factors have not been previously identified for PNES.

We executed a very stringent state-of-the-art variant filtering strategy, optimized for high specificity to identify deleterious SNVs. Following evidence from large-scale studies in epilepsy and other neurological disorders showing that most of the causal variants are ultra-rare in the general population14,30, we only selected and classified unique SNVs not seen in > 200 k population controls. We only considered CNVs if the locus had previously been associated with neurological or psychiatric disorders. The goal of this strategy was to prioritize genetic variants that have a high likelihood to be true and pathogenic for a robust comparison of the PNES and epilepsy groups. Future studies will have to balance sensitivity vs. specificity to prioritize variant discovery.

Among the 12 deleterious variants identified in individuals with PNES without coexistent epilepsy, 50% (6/12) were classified according to the ACMG-AMP 2015 guidelines as pathogenic or likely pathogenic. The ACMG-AMP 2015 guidelines require an established gene to phenotype association as one criterion for pathogenicity prediction13. In a clinical setting, the same variants would not be classified as pathogenic since no single established PNES gene exists. Nevertheless, the detection of pathogenic variants that are likely to cause Mendelian forms of neurological or psychiatric disorders in individuals with PNES is in line with emerging evidence that neurological or psychiatric disorders share a broad range of pleiotropic acting genetic variation8,11,31. Our results are also in line with the observation that up to 48% of all individuals with PNES report a family history of epilepsy and 22% a family history of psychiatric disorders6. PNES could represent one of several clinically defined phenotypes associated with pleiotropic acting genetic variants, affecting genes essential for brain development and function. Surprisingly, none of the P/PL variant carriers with PNES had an abnormal bedside cognition/neurological examination or any major structural abnormality on MRI. However, formal neuropsychological testing was not performed; therefore, it is possible that individuals had more subtle forms of cognitive impairment. It is also possible that our results represent phenotype expansions for some of the genes affected by P/PL variants. Phenotype expansions are common as shown for SLC6A1, a known gene for autism spectrum disorders, epilepsy, and ID32, which was recently associated with schizophrenia without ID or other neurodevelopmental disorder33. Finally, despite an ACMG-AMP 2015 guidelines classification as VUS, we cannot exclude the involvement of the six identified VUS in PNES causation, as all variants identified in this study were predicted in silico as highly pathogenic, never seen in the general population, and affected highly variant intolerant genes. Future case/control studies are needed to identify genes that have not been implicated in other disorders as associated with PNES.

The four identified deletions in individuals with PNES in this study have been reported in the literature in epilepsy and other neurological disorders, with high phenotypic variability and incomplete penetrance15,16,21,34. This high degree of pleiotropy has been observed for the vast majority of all deletions that have been associated with epilepsy or other neurological disorders35. Most likely, these deletions impair neurodevelopmental processes in a rather nonspecific manner and contribute to the genetic variance of a broad spectrum of neurological disorders. The specific disease phenotype is likely further specified by the interplay with genetic background effects and environmental influences following an oligo-/polygenic inheritance model with substantial genetic heterogeneity. Environmental factors which predispose to PNES are very well established1. Genetic vulnerability for a neurological or psychiatric condition could predispose to PNES when combined with environmental stressors. Individual differences in the genetic vulnerability to specific types of trauma and other environmentally relevant variables have been demonstrated, for example, for PTSD36,37. In our study, the P/LP variant carriers showed a similar rate of presence/absence of a history of trauma or abuse as individuals with PNES and no identified variants (P/LP carriers: 3/3 vs. no variants identified: 30/25). However, more research is needed to support this hypothesis and to explain our observation that individuals with PNES alone can carry pathogenic variants that affect genes linked to clinically severe phenotypes.

In conclusion, in this report, we provide the first evidence that genetic factors may play a role in the etiology of PNES. Future large-scale projects that employ comprehensive genetic testing, including polygenic risk scores, are needed for PNES and related genetically understudied disorders such as PTSD, and other conversion disorders. Potentially, such work could provide clues to the etiology and pathophysiology of the disorder, enable the identification of disease biomarkers, and set new directions for the development of new therapies for PNES.

Material and methods

Study participants

Data for this study were obtained from a Cleveland Clinic Institutional Review Board-approved epilepsy biorepository. All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations regarding research involving human subjects. All participants provided written, informed consent, and a blood or saliva sample for use in medical/genetic research. Participants were selected for study inclusion if they met the following criteria: (1) age 18 years or older, (2) video-EEG confirmed diagnosis of focal epilepsy (FE), generalized epilepsy (GE), or psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) without comorbid epileptic seizures, and (3) had blood or saliva DNA available for whole-exome sequencing (N = 694). Our study cohort is detailed in Fig. 1.

Phenotyping procedures

Initial medical record review was conducted for all potential study participants by an epilepsy biorepository research coordinator trained in clinical epilepsy phenotyping (L.F.) and supervised by clinical epileptologists (J.F.B., L.J.). Diagnoses of epilepsy or PNES were established after review of the history and physical examination, scalp EEG video evaluation report, progress notes, social work, psychology and/or psychiatry report, and discharge summary as well as other documentation pertinent to the medical history and clinical diagnoses. Psychiatric diagnoses were established through review of the medical records and patient self-reports during the video-EEG admission. Individuals were classified as having FE, GE, or PNES based on video-EEG and concordant history. All individuals classified as PNES on initial review were re-reviewed by a clinical epileptologist (J.F.B.) to confirm the diagnosis. The diagnosis of PNES required video-EEG recording of a semiology typical for PNES, and an absence of epileptiform abnormalities on either interictal or ictal EEG38. Accordingly, all individuals with PNES included in this study had video-EEG diagnosed PNES without comorbid epilepsy. Individuals with episodes explained by another diagnosis such as physiologic nonepileptic events (e.g., syncope, migraine, sleep disorder) were excluded from the study as were those with comorbid PNES and epileptic seizures and those with episodes consisting of purely subjective symptoms without objective signs (to prevent the inclusion of individuals with epileptic auras, which often do not have EEG abnormalities).

Copy number calling

A total of 688,032 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were genotyped for all samples of this study using the Global Screening Array with Multi-disease drop-in (GSA-MD v1.0) (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The SNP-data was used to detect CNVs in our dataset, using PennCNV’s copy number variant (CNV) calling algorithm39 with GC-wave adjustment. We generated a custom population B-allele frequency (BAF) file before calling CNVs. Adjacent CNVs were merged if the number of intervening markers between them was less than 20% of the total number of the whole segment encompassing both CNVs. CNV calling was followed by extensive quality control (QC) for both samples and CNVs, respectively. Samples with signal intensity log R Ratio (LRR) standard deviation < 0.23, variability of the average LRR values in sliding windows (waviness factor, WF) < 0.02, departure of the BAF from the expected values for two copies (BAF drift) < 0.003, total numbers of CNVs < 80, and European ancestry were included in the analysis. CNV calls were removed from the dataset if they spanned less than 20 markers, were less than 20 Kb in length, had a marker density (amount of markers/length of CNV) < 0.0001, overlapped by > 50% of their total length with regions known to generate artifacts40, or had a frequency > 1% in the study sample. CNVs that were spanning more than 20 markers over ≥ 1 Mb were included in the analysis, even if the marker density was < 0.0001. All CNVs of interest were examined visually by plotting the signal intensities using PennCNV39 (Supplementary Figures 3–9).

Whole-exome sequencing

Whole-exome sequencing (WES) of all samples in this study was performed using Nextera Rapid Capture Exomes enrichment and paired-end reads (151 bp) Illumina sequencing on the Illumina HiSeq 4,000. Duplicate read removal, format conversion, and indexing of the reads, aligned to the GRCh37 human genome reference (RefSeq: GCF_000001405.13), were performed using Picard (https://broadinstitute.github.io/picard). All samples were jointly called using the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) best practice pipeline41.

WES quality control

Quality control (QC) was performed in two iterations of a sample- and variant-level quality filtering. Sequencing and alignment quality metrics were computed using Picard tools (https://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/), leading to the exclusion of samples with freemix contamination estimates > 0.02 and excess chimeric reads > 1%. Low quality variants were filtered out based on the following criteria: (i) phred quality score, QUAL < 20; (ii) GATK truth sensitivity tranche > 99.5% for single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and > 95% for indels; (iii) > 2 alleles; (iv) inbreeding coefficient < − 0.2; (v) sample read depth (DP) for SNVs < 20 and for indels < 30; (vi) genotype quality (GQ) < 99; (vii) allelic balance of heterozygous SNV < 0.25, homozygous SNV < 0.9, heterozygous indels < 0.30, and homozygous indels < 0.95. At the individual level, we removed related samples (KING42 kinship coefficient > 0.0442), samples not clustering with the 1,000 Genomes Project European-ancestry samples (GCTA43 principal component analysis), and samples with ambiguous sex or mismatch with the reported gender. We also filtered out samples that exceeded three standard deviations (SD) from the mean of the entire study cohort on any of the following WES metrics: (i) low mean DP; (ii) low singleton count; (iii) low SNV count; (iv) low or high singleton/SNV ratio; (v) low transition/transversion ratio; (vi) low or high heterozygous/homozygous variant ratio; and (vii) low or high insertion/deletion ratio. Finally, we applied the following exclusion thresholds for variants in the samples that survived previous QC filtering: (i) genotype call rate < 0.95; (ii) minor allele frequency > 0.1; (iii) deviation from the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium with P < 1 × 10–20. The supporting aligned reads of all variants that survived filtering for deleteriousness, detailed in the following paragraph, were visually inspected using the IGV browser44.

Variant deleteriousness assessment

We applied for the identified CNVs and SNVs two different strategies to assess the likelihood of a deleterious effect on disease-relevant loci or genes. CNVs: We only considered CNVs as deleterious if the locus had previously been associated with neurological or psychiatric disorders. SNVs: We used ANNOVAR45 with custom databases to perform a state-of-the-art variant annotation for subsequent deleteriousness assessment. We applied two different filters, based on: i) variant type and frequency and (ii) predicted variant deleteriousness. The frequency-based filter was based on the following criteria: (i) variant not in a genomic duplication (> 1,000 bases of non-repeat masked sequence); (ii) not present in multiple variant databases, totaling > 200 k population controls (Supplementary Table 3). From the remaining variants, we selected only variants with a high confidence prediction to be deleterious using following criteria: (i) loss-of-function (LoF) variants ranked in the top 1% most deleterious variants in the human genome (scaled CADD ≥ 20)46 found in known epilepsy genes or highly LoF-intolerant genes18 (probability, pLI ≥ 0.95); (ii) missense variants ranked in the top 1% most deleterious variants in the human genome (scaled CADD ≥ 20)46 found in missense-constrained regions (MPC ≥ 2 and MTR centile < 15%)47,48, of epilepsy genes or missense intolerant genes (missense Z-score > 3.09, corresponding to P < 10–3)18.

ACMG-AMP 2015 classification of the deleterious CNVs and SNVs

The pathogenicity of all deleterious SNVs was assessed according to the ACMG-AMP guidelines13 using InterVar49. We adjusted the InterVar interpretations were needed for: (i) variant type in genes with a known mode of inheritance; (ii) location of the variant in protein; (iii) absence of variant in population controls; (iv) known gene function and association with disease. Deleterious SNVs expected to cause disorders that are not neurological or psychiatric (i.e., incidental findings), were considered as variants of uncertain significance. The pathogenicity of all deleterious CNVs was assessed directly, using the ACMG-AMP criterions PVS1, PS1, and PS413, when supported by definite evidence.

Supplementary information

Author contributions

C.L. and D.L. designed the study. C.L., M.S., L.M.N., A.S., and R.M.B. analyzed the data. M.J.D. provided computational infrastructure. L.F., L.J., I.M.N., J.F.B., and R.M.B. recruited and phenotyped the individuals from the Cleveland Clinic tertiary care epilepsy center. C.L., J.F.B., R.M.B., and D.L. interpreted the analyses. D.L. supervised the study. C.L. and D.L. wrote the manuscript. All authors interpreted the data and revised the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by institutional funding from the Cleveland Clinic Foundation. RMB received support from the NIH/NCATS, CTSA UL1TR000439, Cleveland, Ohio.

Data availability

Data are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Costin Leu, Email: leuc@ccf.org.

Dennis Lal, Email: lald@ccf.org.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-72101-8.

References

- 1.Kanemoto K, et al. PNES around the world: Where we are now and how we can close the diagnosis and treatment gaps-an ILAE PNES Task Force report. Epilepsia Open. 2017;2:307–316. doi: 10.1002/epi4.12060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Magaudda A, et al. Identification of three distinct groups of patients with both epilepsy and psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsy Behav. 2011;22:318–323. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ekanayake V, et al. Personality traits in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) and psychogenic movement disorder (PMD): Neuroticism and perfectionism. J. Psychosom. Res. 2017;97:23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2017.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walsh S, Levita L, Reuber M. Comorbid depression and associated factors in PNES versus epilepsy: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Seizure. 2018;60:44–56. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2018.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Madaan P, et al. Clinical spectrum of psychogenic non epileptic seizures in children; an observational study. Seizure. 2018;59:60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2018.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alessi R, Valente KD. Psychogenic non-epileptic seizures at a tertiary care center in Brazil. Epilepsy Behav. 2013;26:91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asadi-Pooya AA, Emami M. Juvenile and adult-onset psychogenic non-epileptic seizures. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2013;115:1697–1700. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brainstorm Consortium et al. Analysis of shared heritability in common disorders of the brain. Science. 2018 doi: 10.1126/science.aap8757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leu C, et al. Pleiotropy of polygenic factors associated with focal and generalized epilepsy in the general population. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0232292. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hesdorffer DC. Comorbidity between neurological illness and psychiatric disorders. CNS Spectr. 2016;21:230–238. doi: 10.1017/S1092852915000929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heyne HO, et al. De novo variants in neurodevelopmental disorders with epilepsy. Nat. Genet. 2018;50:1048–1053. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0143-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asadi-Pooya AA. Biological underpinnings of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: Directions for future research. Neurol. Sci. 2016;37:1033–1038. doi: 10.1007/s10072-016-2540-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richards S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015;17:405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Epi25 Collaborative Ultra-rare genetic variation in the epilepsies: A whole-exome sequencing study of 17,606 individuals. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2019;105:267–282. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2019.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balciuniene J, et al. Recurrent 10q22-q23 deletions: A genomic disorder on 10q associated with cognitive and behavioral abnormalities. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;80:938–947. doi: 10.1086/513607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sønderby IE, et al. Dose response of the 16p11.2 distal copy number variant on intracranial volume and basal ganglia. Mol. Psychiatry. 2018 doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0118-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cardoso C, et al. The location and type of mutation predict malformation severity in isolated lissencephaly caused by abnormalities within the LIS1 gene. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000;9:3019–3028. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.20.3019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karczewski KJ, et al. Variation across 141,456 human exomes and genomes reveals the spectrum of loss-of-function intolerance across human protein-coding genes: Supplementary Information. bioRxiv. 2019 doi: 10.1101/531210. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fickie MR, et al. Adults with Sotos syndrome: Review of 21 adults with molecularly confirmed NSD1 alterations, including a detailed case report of the oldest person. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2011;155A:2105–2111. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nicita F, et al. Seizures and epilepsy in Sotos syndrome: Analysis of 19 Caucasian patients with long-term follow-up. Epilepsia. 2012;53:e102–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stankiewicz P, et al. Recurrent deletions and reciprocal duplications of 10q11.21q11.23 including CHAT and SLC18A3 are likely mediated by complex low-copy repeats. Hum. Mutat. 2012;33:165–179. doi: 10.1002/humu.21614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Butler KM, et al. De novo variants in GABRA2 and GABRA5 alter receptor function and contribute to early-onset epilepsy. Brain. 2018;141:2392–2405. doi: 10.1093/brain/awy171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lakhina V, et al. Seizure evoked regulation of LIM-HD genes and co-factors in the postnatal and adult hippocampus. F1000Res. 2013;2:205. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.2-205.v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vician LJ, et al. MAPKAP kinase-2 is a primary response gene induced by depolarization in PC12 cells and in brain. J. Neurosci. Res. 2004;78:315–328. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liang Z, et al. The pseudokinase CaMKv is required for the activity-dependent maintenance of dendritic spines. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:13282. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balduini CL, Pecci A, Savoia A. Recent advances in the understanding and management of MYH9-related inherited thrombocytopenias. Br. J. Haematol. 2011;154:161–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang EJ, et al. Identification of a novel MYH9 mutation in a young adult with inherited thrombocytopenia and recurrent seizures by targeted exome sequencing. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2019 doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000001430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pérez-Palma E, et al. Heterogeneous contribution of microdeletions in the development of common generalised and focal epilepsies. J. Med. Genet. 2017;54:598–606. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2016-104495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niestroj L-M, et al. Evaluation of copy number burden in specific epilepsy types from a genome-wide study of 18,564 subjects. Genetics. 2019 doi: 10.1101/651299. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Genovese G, et al. Increased burden of ultra-rare protein-altering variants among 4,877 individuals with schizophrenia. Nat. Neurosci. 2016;19:1433–1441. doi: 10.1038/nn.4402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chawner SJRA, et al. Genotype-phenotype associations in children with copy number variants associated with high neuropsychiatric risk in the UK (IMAGINE-ID): A case-control cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019 doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30123-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johannesen KM, et al. Defining the phenotypic spectrum of SLC6A1 mutations. Epilepsia. 2018;59:389–402. doi: 10.1111/epi.13986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rees E, et al. De novo mutations identified by exome sequencing implicate rare missense variants in SLC6A1 in schizophrenia. Nat. Neurosci. 2020;23:179–184. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0565-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blazejewski SM, Bennison SA, Smith TH, Toyo-Oka K. Neurodevelopmental genetic diseases associated with microdeletions and microduplications of chromosome 17p13.3. Front. Genet. 2018;9:80. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Torres F, Barbosa M, Maciel P. Recurrent copy number variations as risk factors for neurodevelopmental disorders: Critical overview and analysis of clinical implications. J. Med. Genet. 2016;53:73–90. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2015-103366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharma S, Ressler KJ. Genomic updates in understanding PTSD. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2019;90:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2018.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smoller JW. The genetics of stress-related disorders: PTSD, depression, and anxiety disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41:297–319. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.LaFrance WC, Baker GA, Duncan R, Goldstein LH, Reuber M. Minimum requirements for the diagnosis of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: A staged approach: A report from the International League Against Epilepsy Nonepileptic Seizures Task Force. Epilepsia. 2013;54:2005–2018. doi: 10.1111/epi.12356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang K, et al. PennCNV: An integrated hidden Markov model designed for high-resolution copy number variation detection in whole-genome SNP genotyping data. Genome Res. 2007;17:1665–1674. doi: 10.1101/gr.6861907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marshall CR, et al. Contribution of copy number variants to schizophrenia from a genome-wide study of 41,321 subjects. Nat. Genet. 2017;49:27–35. doi: 10.1038/ng.3725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van der Auwera GA, et al. From FastQ data to high confidence variant calls: The Genome Analysis Toolkit best practices pipeline. Curr Protoc Bioinform. 2013;11:11.10.1–11.10.33. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1110s43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manichaikul A, et al. Robust relationship inference in genome-wide association studies. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2867–2873. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang J, Lee SH, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. GCTA: A tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011;88:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robinson JT, et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:24–26. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: Functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kircher M, et al. A general framework for estimating the relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nat. Genet. 2014;46:310–315. doi: 10.1038/ng.2892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Samocha KE, et al. Regional missense constraint improves variant deleteriousness prediction. bioRxiv. 2017 doi: 10.1101/148353. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Traynelis J, et al. Optimizing genomic medicine in epilepsy through a gene-customized approach to missense variant interpretation. Genome Res. 2017;27:1715–1729. doi: 10.1101/gr.226589.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li Q, Wang K. InterVar: Clinical interpretation of genetic variants by the 2015 ACMG-AMP guidelines. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017;100:267–280. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.