Abstract

A nanorod-like lanthanum metal–organic framework (LaMOF) was synthesized in aqueous solution by coordinating La(III) to the ligand 1,3,5-benzenetricarboxylic acid. The fibrous LaMOF was fabricated by splitting the nanorod-like LaMOF in a solution of d-amino acid oxidase, and the enzyme was immobilized simultaneously. Based on SEM and TEM images, STEM mapping, and spectra of XPS and FTIR, the mechanism of formation of the fibrous LaMOF and the distinct interfacial phenomena have been elucidated. The fabrication of the fibrous LaMOF and simultaneous immobilization of the enzyme were carried out in aqueous solutions at room temperature, without using any organic solvent. It is a clean and time- and energy-effective process. This work presents a distinct and clean methodology for the fabrication of the fibrous MOF. Potentially, the environmentally benign methodology can be extended to immobilize other enzymes.

Introduction

Metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) are coordinated metal ions linked by imidazolate or anionic carboxylate ligands.1−3 Among the metals, the lanthanum metal has unique electronic, optical, magnetic, and chemical characteristics resulting from the 4f electronic shells.4 Lanthanum MOFs (LaMOFs) have been synthesized by La ions coordinating to various ligands,5 including 1,4-henylenebis (methylidyne)tetrakis,6 5-(pyrimidyl)-tetrazolato,7 4,4′-(hexafluoroisopropylidene) bis(benzoic acid),8 5-carboxylato-tetrazolato,9 and 5-amino-isophthalic acid.10 LaMOFs can exhibit luminescence and adsorption properties11 and have been used for selective water adsorption10 and for the detection of picric acid and Fe3+ ions.12 Mono-, di-, and tricarboxylic acid-based LaMOFs were synthesized for the adsorption of arsenate from water.13 The LaMOF was calcinated as an inorganic adsorbent for phosphate capture.14 The composite of graphene oxide–LaMOF was prepared for the isolation of hemoglobin.15 The Cu–LaMOF was used for the oxidation of benzylic hydrocarbons and cycloalkenes.16 However, no results on using the LaMOF for enzyme immobilization have been reported.

Sustainable development requires that the MOF production should consider health, safety, and the environment.17 It is expected that the MOF production is carried out in a clean way with no involvement of toxic chemicals and with less energy consumed.18 MOFs have been utilized for immobilization of enzymes.19,20 The approaches, including adsorption on the surface, covalent linking, pore encapsulation, and coprecipitation, are commonly used to immobilize enzymes.21 Although tremendous results have been obtained, researchers are still showing great interest in exploring MOFs for enzyme immobilization.22−26d-Amino acid oxidases (DAAOs) are O2-dependent flavoenzymes, catalyzing the transformation of a d-amino acid substrate into the corresponding α-keto acid.27,28 DAAOs can catalyze the reactions for deracemization of racemic d-amino acids, oxidation of cephalosporin C, and production of precursors for pharmaceuticals. Herein, we present the fabrication of the fibrous LaMOF and simultaneous immobilization of DAAO in a green way, as illustrated in Scheme 1. The nanorod-like LaMOF is synthesized by coordinating lanthanum to the ligand 1,3,5-benzenetricarboxylic acid in aqueous solution. The nanorod-like LaMOF is then incubated in the solution of the enzyme, which is prepared by dissolving the enzyme in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The nanorod-like LaMOF is split into the fibrous LaMOF, and the enzyme is immobilized on the fibrous LaMOF simultaneously. The fabrication of the fibrous LaMOF was carried out in aqueous solution without using any organic solvents. The fabrication process was accomplished at room temperature, and the time needed was less than 3 h. Hence, it is a clean and time- and energy-effective process. This work presents a distinct and green methodology for the fabrication of the fibrous MOF. Potentially, the environmentally benign methodology can have a wide application for enzyme immobilization.

Scheme 1. Green Process for Fabrication of the Fibrous LaMOF and Simultaneous Immobilization of the Enzyme (BTC: 1,3,5-Benzenetricarboxylic Acid).

Results and Discussion

Fabrication of Fibrous LaMOF with Simultaneous Immobilization of Enzyme

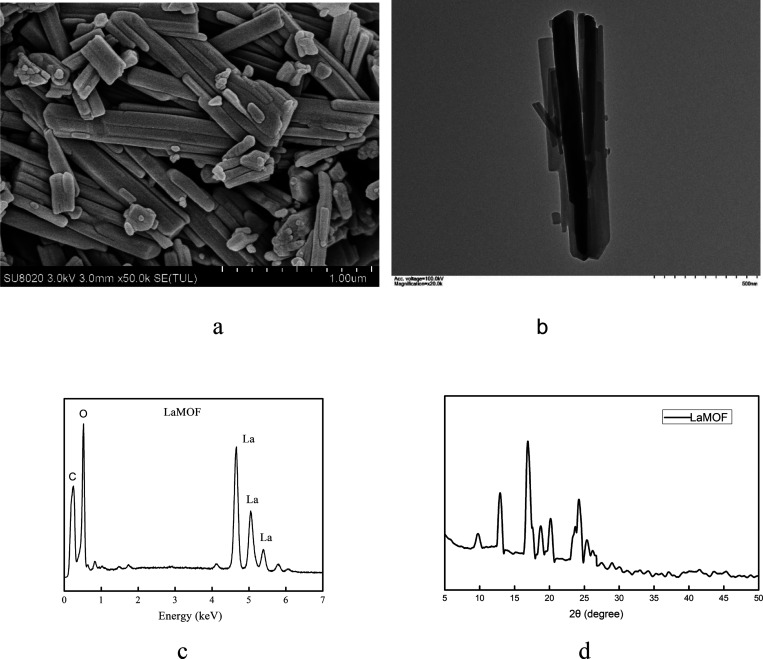

The lanthanum MOF (LaMOF) was synthesized by coordinating La(III) to the ligand 1,3,5-benzenetricarboxylic acid (BTC) in aqueous solution at room temperature. The LaMOF exhibited a morphology of bundles of nanorods, as illustrated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Figure 1a) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM, Figure 1b). Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) was used to analyze the elements. The obtained EDS spectrum is shown in Figure 1c, with peaks for C at 0.239 and O at 0.53 keV. The peaks at 4.64, 5.05, and 5.40 keV are for La. The XRD spectrum in Figure 1d exhibits the characteristic peaks of the LaMOF at 12.82, 16.90, and 24.12°.4

Figure 1.

(a) SEM and (b) TEM images of the lanthanum MOF (LaMOF). (c) EDS spectrum showing the peaks for C, O, and La. (d) XRD spectrum for the LaMOF.

The solution of d-amino acid oxidase (DAAO) was prepared by dissolving DAAO in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The nanorod-like LaMOF was incubated in the solution of DAAO. The formation of fibers started from the surface of the nanorods, as shown in Figure 2a. Further progress of LaMOF splitting was observed after 90 min of incubation (Figure 2b). A longer incubation time (120 min) led to fully splitting of the LaMOF (Figure 2c). The splitting of the nanorod-like LaMOF into the fibrous LaMOF (f-LaMOF) was accompanied by simultaneous immobilization of DAAO. At the N- and C-terminus of DAAO, there are His-tags. After splitting of the LaMOF, some of the metal sites of La(III) of the f-LaMOF were unsaturated. The coordinative interaction between the metal sites and the hexahistidine-tagged DAAO is one of the driving forces for the enzyme immobilization. Metal ion affinity chromatography uses similar interactions for purifying recombinant enzymes.21 The immobilization of DAAO may also come from the contribution of the nitrogen atoms of the amide groups that formed complexes with the metal. The TEM images in Figure 3 show obvious immobilization of DAAO for the sample of f-LaMOF@DAAO. In a separate experiment, the enzyme DAAO was labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC). The nanorod-like LaMOF was incubated in the solution of FITC-labeled DAAO dissolved in PBS. The f-LaMOF with the immobilized FITC-labeled DAAO was subjected to observation under a fluorescence microscope (DeltaVision OMX V3). The optical images in Figures 2 and 3 confirmed the immobilization of FITC-labeled DAAO. Figure 4a shows the scanning transmission electron micrograph (STEM) image and elemental mapping images for f-LaMOF@DAAO. The elemental distributions of La, O, and P within the conjugate f-LaMOF@DAAO can be observed. Figure 4b shows the EDS spectrum for the elements C, N, O, P, and La.

Figure 2.

SEM (left) and fluorescence (right) images. Splitting of the nanorod-like LaMOF into the fibrous LaMOF with simultaneous immobilization of DAAO. (a–c) Incubation of the nanorod-like LaMOF in the solution of DAAO was carried out for (a) 40 min, (b) 90 min, and (c) 120 min.

Figure 3.

TEM (left) and fluorescence (right) images. Splitting of the nanorod-like LaMOF into the fibrous LaMOF with simultaneous immobilization of DAAO. (a, b) Incubation of the nanorod-like LaMOF in the solution of DAAO was carried out for (a) 40 min and (b) 120 min.

Figure 4.

f-LaMOF@DAAO. (a) STEM image and elemental mapping images showing the elemental distributions of La, O, and P. (b) EDS spectrum showing the peaks for the elements C, N, O, P, and La.

Mechanism of Formation of Fibrous LaMOF

Separate experiments confirmed that the enzyme DAAO could not split the nanorod-like LaMOF into the fibrous LaMOF. It was postulated that PBS played a key role in the formation of the fibrous LaMOF. Figure 5a shows the SEM image for the nanorod-like LaMOF that was incubated in PBS for 40 min. It can be clearly observed that the splitting of the nanorod-like LaMOF into the fibrous LaMOF started from the surface of the nanorods. The TEM image in Figure 5b further confirmed this surface phenomenon. When the incubation time was increased to 2 h, fully splitting of the nanorod-like LaMOF into the fibrous LaMOF was accomplished, as illustrated by the images of SEM (Figure 6a) and TEM (Figure 6b). The scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) image and elemental mapping images for the fibrous LaMOF show the elemental distributions of La, O, and P within the fibrous LaMOF (Figure 7a). The EDS spectrum shows the peaks for the elements C, O, P, and La (Figure 7b).

Figure 5.

(a) SEM and (b) TEM images after incubation of the nanorod-like LaMOF in PBS for 40 min. Splitting of the nanorod-like LaMOF into the fibrous LaMOF starting from the surface of the nanorods.

Figure 6.

(a) SEM and (b) TEM images for the fully split LaMOF (fibrous LaMOF). Incubation of the nanorod-like LaMOF in PBS for 2 h.

Figure 7.

(a) STEM image and elemental mapping images for f-LaMOF showing the elemental distributions of La, O, and P. (b) EDS spectrum showing the peaks for C, O, P, and La.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and FTIR spectra were measured for the nanorod-like LaMOF, f-LaMOF, and f-LaMOF@DAAO. Figure 8a shows the XPS survey spectra. La, C 1s, and O 1s are the main elements of the nanorod-like LaMOF, in accordance with the compositions of the LaMOF that is synthesized by the coordination of La(III) with BTC. After fully splitting of the nanorod-like LaMOF into the f-LaMOF in PBS, the peaks of P 2p and P 2s appearing in the spectrum of the f-LaMOF confirmed the existence of the P element. It is indicative of the involvement of phosphate in the splitting of the nanorod-like LaMOF. The peak of N 1s appeared in the spectrum of f-LaMOF@DAAO, and the N element came from the immobilized DAAO. Figure 8b shows the expanded scans of the nanorod-like LaMOF spectrum in the La 3d regions. Binding energies of 836.1 and 852.9 eV correspond to the two main peaks for 3d5/2 and 3d3/2, respectively, and binding energies of 839.3 and 856.1 eV are for the satellite peaks.29,30 For the nanorod-like LaMOF, the main peaks exhibited smaller intensities than the satellite peaks (Figure 8b), but the difference is not significant. The satellite peaks are ascribed to the state of 3d94f1, which is attributed to the electron transfer from O 2p to the 4f shell of lanthanum.29,30 Similarly, the f-LaMOF (Figure 8c) and f-LaMOF@DAAO (Figure 8d) exhibited two peaks, each of these peaks is a doublet. However, the main peaks are more intense than the satellite peaks. This is ascribed to the more electronegative phosphate coordinating more strongly with the La(III) ion, decreasing the intensity of the satellites being adjacent to the 3d5/2 and 3d3/2 core levels.

Figure 8.

(a) XPS survey spectra for the LaMOF, f-LaMOF, and f-LaMOF@DAAO. (b–d) Expanded scans of the spectrum in the La 3d regions.

The XPS survey spectra show that both f-LaMOF and f-LaMOF@DAAO exhibit the C 1s peaks. It is indicated that, after splitting of the LaMOF into the fibrous LaMOF by phosphate, there exists the ligand BTC that is still coordinating to La(III). More information can be obtained from the expanded scans of the spectra in the C 1s regions, as shown in Figure 9, in which the C 1s XPS spectrum of the ligand BTC is also shown for comparison. The C 1s spectra were deconvoluted into three peaks using PeakFit 4.0 software, 284.7 eV for C–C, 286.2 eV for C–O, and 288.8 eV for O—C=O, corresponding to graphitic, alcoholic, and carboxyl carbons, respectively.30 The LaMOF is synthesized by coordinating La(III) to the carboxyl of BTC. Herein, we pay attention to O—C=O, which can reflect the situations of the carboxyl of BTC before and after splitting of the LaMOF. The relative peak intensities of O—C=O are 37.0% in BTC (Figure 9a), 13.0% in the LaMOF (Figure 9b), 24.0% in the f-LaMOF (Figure 9c), and 18.7% in f-LaMOF@DAAO (Figure 9d). Compared to free BTC, the LaMOF shows a decreased intensity of O—C=O, ascribing to the coordination of La(III) with the carboxyl of BTC. The f-LaMOF was formed by phosphate coordinating to the already carboxyl-coordinated La(III) ions. The replacement of one of the carboxyl groups by phosphate yields a swinging carboxyl. The swinging carboxyl groups contribute to the increased intensity of O—C=O in the f-LaMOF (Figure 9c), in contrast to that in the LaMOF (Figure 9b). The relative peak intensities of O—C=O of f-LaMOF@DAAO is 18.76%. However, this value cannot be used for comparison as the intensity of O—C=O in f-LaMOF@DAAO comes from the contributions of both the ligand BTC and the enzyme DAAO.

Figure 9.

(a–d) C 1s XPS spectra of (a) BTC, (b) LaMOF, (c) f-LaMOF, and (d) f-LaMOF@DAAO.

FTIR spectra of the LaMOF, f-LaMOF, and f-LaMOF@DAAO are shown in Figure 10a. Compared to

the LaMOF, the f-LaMOF and f-LaMOF@DAAO exhibit broad peaks in the

region of 900–1200 cm–1, ascribing to protonated

phosphate. Each broad peak was deconvoluted into two peaks, to speculate

on the molecular configurations of the coordination involved by phosphate.

For the f-LaMOF, the broad spectrum is an assemblage of two v3 vibrations (1051 and 1006 cm–1). For

f-LaMOF@DAAO, the bands were slightly shifted to 1050 and 1005 cm–1. The v3 vibrations at 1051/1050

cm–1 are ascribed to the monoprotonated  ,31−33 and at 1006/1005 cm–1,

the v3 vibrations are attributed to fully deprotonated

phosphate

,31−33 and at 1006/1005 cm–1,

the v3 vibrations are attributed to fully deprotonated

phosphate  The FTIR spectra indicate

the coordination of La(III) with phosphate in the forms of

The FTIR spectra indicate

the coordination of La(III) with phosphate in the forms of  and

and . The f-LaMOF exhibited an intensity ratio of 1050 to 1006 cm–1 being smaller than that of 1050 to 1005 cm–1 by f-LaMOF@DAAO. The difference in the intensity ratio is possibly

ascribed to that f-LaMOF@DAAO that was obtained by splitting of the

LaMOF accompanied by the immobilization of DAAO.

. The f-LaMOF exhibited an intensity ratio of 1050 to 1006 cm–1 being smaller than that of 1050 to 1005 cm–1 by f-LaMOF@DAAO. The difference in the intensity ratio is possibly

ascribed to that f-LaMOF@DAAO that was obtained by splitting of the

LaMOF accompanied by the immobilization of DAAO.

Figure 10.

(a) FTIR spectra for the La-MOF, f-LaMOF, and f-LaMOF@DAAO. (b) f-LaMOF and (c) f-LaMOF@DAAO in the region of 900–1200 cm–1.

The XPS and

FTIR spectra provide evidence for phosphate coordinating to La(III)

in the f-LaMOF and f-LaMOF@DAAO. Phosphate has a central phosphorus

being surrounded by four oxygen atoms with a high charge-to-radius

ratio, providing phosphate a capability of coordinating to metals.

Phosphonate monoester and bis(phosphonatemonoester) were used as linkers

in Cu(II) and Zn(II) MOFs.34,35 The “lanthanum

phosphate” chain in lanthanum coordination polymers demonstrated

the coordination of lanthanum with phosphate.36 In contrast to carboxylate, phosphate is more electronegative. Phosphate

groups exhibited relatively pronounced affinity toward metal ions

than carbonyl.37−39 Research

on the coordination of acetyl phosphate with metal ions Ca2+, Cu2+, Mg2+, and Zn2+ demonstrated

that the primary metal ion binding site in acetyl phosphate is the  group.37−39 Compared to the phosphate group, the carbonyl

group is a relatively weak binding site to coordinate the metal ions.37−39 When the nanorod-like LaMOF is

incubated in the enzyme solution, the phosphate competes with the

carboxyl of BTC as a coordinating site. The carboxyl oxygen-coordinated

La(III) ion recognizes the phosphate oxygen. The more electronegative

phosphate coordinates more strongly with the La(III) ion. Thus, La–O

bonds between La(III) and carboxyl groups of BTC in the nanorod-like

LaMOF can be partially broken and replaced by a phosphate anion. In

the f-LaMOF and f-LaMOF@DAAO, both the phosphate and carbonyl oxygens

coordinating to La(III) can result in a stabilized structure.

group.37−39 Compared to the phosphate group, the carbonyl

group is a relatively weak binding site to coordinate the metal ions.37−39 When the nanorod-like LaMOF is

incubated in the enzyme solution, the phosphate competes with the

carboxyl of BTC as a coordinating site. The carboxyl oxygen-coordinated

La(III) ion recognizes the phosphate oxygen. The more electronegative

phosphate coordinates more strongly with the La(III) ion. Thus, La–O

bonds between La(III) and carboxyl groups of BTC in the nanorod-like

LaMOF can be partially broken and replaced by a phosphate anion. In

the f-LaMOF and f-LaMOF@DAAO, both the phosphate and carbonyl oxygens

coordinating to La(III) can result in a stabilized structure.

Assay of Enzymatic Activity

The deamination of d-alanine was catalyzed by the immobilized enzyme f-LaMOF@DAAO. d-Alanine was converted to pyruvate. The reaction of 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH) with pyruvate can produce a colored product.40 The reaction of d-alanine deamination was carried out for 10 min followed by the addition of DNPH. There is no significant difference in a brownish color between the two systems of free DAAO and f-LaMOF@DAAO (Figure 11a). The characteristic absorption peaks of the colored products centered at 372 nm are shown in Figure 11b. Both systems exhibited comparable absorption intensities. The qualitative results in Figure 11a,b indicated that both systems produced a comparable amount of pyruvate. Furthermore, the enzyme kinetics was studied for quantitative comparison between free DAAO and f-LaMOF@DAAO. The immobilized enzyme used the same enzyme concentration as that of the free enzyme. The plot of the initial reaction rate versus d-alanine concentration is shown in Figure 11c. By fitting to the Michaelis–Menten kinetics equation, kinetics parameters were obtained as listed in Table 1. The apparent Km value of 12.02 mM f-LaMOF@DAAO is smaller than the Km value of 15.37 mM free DAAO.41 It is indicated that f-LaMOF@DAAO exhibited an enhanced affinity toward the substrate. The catalysis efficiency can be measured by the kcat/Km ratio.42 The apparent kcat/Km ratio of f-LaMOF@DAAO is 70.4 mM–1 min–1, in comparison to a kcat/Km ratio of 75.2 mM–1 min–1 by DAAO.41 The immobilized enzyme f-LaMOF@DAAO retained 93.5% of the activity of free DAAO. The activity loss due to the immobilization is not significant. Under the same reaction conditions, f-LaMOF@DAAO was reused five times. Prior to each reuse, f-LaMOF@DAAO was washed with the PBS buffer, centrifuged, and dried. After five times of reuse, f-LaMOF@DAAO retained 89.6% of its original activity, as shown in Figure 11d.

Figure 11.

d-Alanine deamination under the catalysis of f-LaMOF@DAAO. (a) Photographs of the colored products. (b) Absorption at 372 nm for the colored products. (c) Plot of the initial reaction rate (V0) versus d-alanine concentration. (d) Reuse of f-LaMOF@DAAO.

Table 1. Kinetics Parameters for DAAO and f-LaMOF@DAAOa.

| parameters | DAAO | f-LaMOF@DAAO |

|---|---|---|

| Km (mM) | 15.37 | 12.02 ± 0.42 |

| kcat (min–1) | 1155.8 | 845.7 ± 16.5 |

| kcat/Km (mM–1 min–1) | 75.2 | 70.4 ± 2.2 |

Conclusions

In the solution of d-amino acid oxidase, the fibrous LaMOF was fabricated and DAAO was immobilized simultaneously. The enzyme solution is prepared by dissolving DAAO in phosphate-buffered saline. PBS is an environmentally benign solvent.43−45 It is a perfect solution for dissolving enzymes and proteins as the structures and conformation of enzymes and proteins can be well preserved in PBS. This is the reason that immobilization of enzymes/proteins on various supports is generally carried out in PBS. This work presents a distinct methodology for the fabrication of the fibrous MOF. Potentially, the environmentally benign methodology can be extended to immobilize enzymes/proteins for wide applications.

Experiments

Materials

Lanthanum(III) nitrate hexahydrate and 1,3,5-benzenetricarboxylic acid were purchased from Sigma. d-Amino acid oxidase (DAAO) with His-tags was expressed and purified as described in previous work.25,28

Preparation of Fibrous LaMOF with Simultaneous Enzyme Immobilization

The aqueous solution of lanthanum nitrate was prepared by dissolving 1.3 g of lanthanum nitrate hexahydrate in 8 mL of H2O, designated as solution A. The solution of 1,3,5-benzenetricarboxylic acid (BTC) was prepared by dissolving 0.84 g of BTC in 40 mL of water/ethanol (vol/vol, 10:1), designated as solution B. Solution A was added to solution B under agitation at room temperature for 30 min. The initial ratio of BTC to La is 4:3. The precipitate was obtained by centrifugation followed by washing with water. The synthesized LaMOF exhibited a nanorod-like morphology.

The nanorod-like LaMOF (10 mg) was added to 7 mL of the DAAO solution, which was prepared by dissolving DAAO in phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.6, 10 mM). The enzyme concentrations were 10.3 mg mL–1. The mixture was sonicated for 1 min and then incubated for 10 min. The sonication and incubation were repeated several times. Afterward, the mixture was agitated at 140 rpm for 2 h. The precipitate was recovered by centrifugation, that is, the fibrous LaMOF immobilized with DAAO (f-LaMOF@DAAO).

The concentrations of DAAO were determined using the microbicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay. By measuring the amount of DAAO in the original solutions, supernatants, and washing solutions, the amount of DAAO immobilized on the f-LaMOF was determined. Triplicate measurements were carried out, and average values were obtained. The amount of DAAO immobilized was finally determined to be 0.27 ± 0.02 mg DAAO/mg f-LaMOF.

Enzymatic Activity Assay

Qualitative Assay

d-Alanine (10 mM) was dissolved in PBS (1.5 mL, pH 8.0, 50 mM). Then, immobilized DAAO (f-LaMOF@DAAO) was added to the d-alanine solution. The enzyme concentration was 0.6 mg mL–1. The catalysis was carried out for 6 min. Then, trichloroacetic acid solution (20% w/v) was used to terminate the reaction. The solution was centrifuged, and the supernatant was collected. The solution of 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH) (250 μL, 0.1 mM) was added to the supernatant. After incubation for 12 min, NaOH (500 μL, 1.5 M) was added and incubation was continued for another 10 min, and the color change of the solution was observed. Fifteen microliters of the solution was measured to obtain UV–vis absorption. For free DAAO, similar measurement was performed.

Quantitative Assay

The kinetics for f-LaMOF@DAAO was investigated at 30 °C. f-LaMOF@DAAO was dissolved in 20 mL of PBS buffer (pH 8.0, 50 mM). The concentration of DAAO immobilized was 0.002 mg mL–1. d-Alanine was dissolved in the PBS buffer with a concentration range from 0.3 to 40 mM. HPLC (Shimadzu LC-10A) with a C18 column (Diamonsil) was used to measure the concentrations of d-alanine and pyruvate. PBS (0.05 M, pH 2.5) and methanol (95:5 v/v) constituted the mobile phase with a flow rate of 0.8 mL min–1. Prior to the injection, the solutions were filtered using a polycarbonate membrane (220 nm).

At each d-alanine concentration, the initial reaction rate was obtained by measuring the change of d-alanine concentration every 1 min for 5 min. At each d-alanine concentration, triplicate measurements were carried out. For each d-alanine concentration, the initial rate of the reaction was obtained based on 15 data points. Eight d-alanine concentrations were used to plot the initial rate of the reaction versus d-alanine concentration. By fitting the Michaelis–Menten equation to data, the kinetics parameters were obtained.

Characterization

SEM Measurements

After drying the samples at room temperature, the samples were sputter coated with gold. Then, the samples were subjected to the observation using a scanning electron microscope (Hitachi SU80 20).

EDS Measurement

The samples were dried at room temperature, and then the images and data were obtained using a scanning electron microscope (Hitachi S-4700).

Observation of the Immobilized DAAO under a Microscope

The enzyme DAAO was labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC). The FITC-labeled DAAO was immobilized on the f-LaMOF using similar procedures to immobilization of DAAO. After washing with Triton X-100, the sample of f-LaMOF@FITC-DAAO was observed under a fluorescence microscope (DeltaVision OMX V3).

TEM Measurement

The LaMOF was dispersed in double-deionized water under sonication. Then, a drop of the suspension was dropped on a copper wire. After drying on air, the copper wire was subjected to the TEM measurements using a transmission electron microscope (FEI Tecnai G2 20).

STEM Measurement

The samples were dispersed in double-deionized water under sonication. Then, a drop of the suspension was dropped on a copper wire. After drying on air, the copper wire was subjected to the STEM measurements using a scanning transmission electron microscopy analyzer (FEI Scios).

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectra

FTIR-attenuated total reflection (ATR) spectra were recorded on a spectrometer (Bruker Tensor 27) at a nominal resolution of 2 cm–1. Each spectrum is the result of the accumulation and averaging of 512 interferograms. Ultrapure nitrogen was continuously introduced into the sample compartment to minimize the spectral contribution of atmospheric water.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (21776011 and 21978018).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Vikrant K.; Tsang D. C. W.; Raza N.; Giri B. S.; Kukkar D.; Kim K.-H. Potential Utility of Metal-Organic Framework-Based Platform for Sensing Pesticides. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 8797–8817. 10.1021/acsami.8b00664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du X.; Su H.; Zhang X. Metal–Organic Framework-Derived Cu-Doped Co9S8 Nanorod Array with Less Low-Valence Co Sites as Highly Efficient Bifunctional Electrodes for Overall Water Splitting. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 16917–16926. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b04739. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shang W.; Kang X.; Ning H.; Zhang J.; Zhang X.; Wu Z.; Mo G.; Xing X.; Han B. Shape and Size Controlled Synthesis of MOF Nanocrystals with the Assistance of Ionic Liquid Mircoemulsions. Langmuir 2013, 29, 13168–13174. 10.1021/la402882a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha J.; Carlos L. D.; Paz F. A. A.; Ananias D. Luminescent Multifunctional Lanthanides-Based Metal-Organic Frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 926–940. 10.1039/C0CS00130A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y.-N.; Xiong P.; He C.-T.; Deng J.-H.; Zhong D.-C. A Lanthanum Carboxylate Framework with Exceptional Stability and Highly Selective Adsorption of Gas and Liquid. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 5013–5018. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.8b00082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plabst M.; Bein T. 1,4-Phenylenebis(methylidyne)tetrakis(phosphonic acid): A New Building Block in Metal Organic Framework Synthesis. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 48, 4331–4341. 10.1021/ic802294e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gándara F.; de la Peña-O’Shea V. A.; Illas F.; Snejko N.; Proserpio D. M.; Gutiérrez-Puebla E.; Monge M. A. Three Lanthanum MOF Polymorphs: Insights into Kinetically and Thermodynamically Controlled Phases. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 48, 4707–4713. 10.1021/ic801779j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Diéguez A.; Salinas-Castillo A.; Sironi A.; Seco J. M.; Colacio E. A chiral diamondoid 3D lanthanum metal–organic framework displaying blue-greenish long lifetime photoluminescence emission. CrystEngComm 2010, 12, 1876–1879. 10.1039/b919243c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheta S. M.; El-Sheikh S. M.; Abd-Elzaher M. M.; Wassel A. R. A novel nano-size lanthanum metal-organic framework based on 5-amino-isophthalic acid and phenylenediamine: Photoluminescence study and sensing applications. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2019, e4777 10.1002/aoc.4777. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calahorro A. J.; Fairen-Jiménez D.; Salinas-Castillo A.; López-Viseras M. E.; Rodríguez-Diéguez A. Novel 3D lanthanum oxalate metal-organic-framework: Synthetic, structural, luminescence and adsorption properties. Polyhedron 2013, 52, 315–320. 10.1016/j.poly.2012.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plessius R.; Kromhout R.; Ramos A. L. D.; Ferbinteanu M.; Mittelmeijer-Hazeleger M. C.; Krishna R.; Rothenberg G.; Tanase S. Highly Selective Water Adsorption in a Lanthanum Metal-Organic Framework. Chem. – Eur. J. 2014, 20, 7922–7925. 10.1002/chem.201403241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C.; Yan Y.; Pan Q.; Sun L.; He H.; Liu Y.; Liang Z.; Li J. A microporous lanthanum metal-organic framework as a bi-functional chemosensor for the detection of picric acid and Fe3+ ions. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 13340–13346. 10.1039/C5DT01065A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhu S. M.; Imamura S.; Sasaki K. Mono-, Di-, and Tricarboxylic Acid Facilitated Lanthanum-Based Organic Frameworks: Insights into the Structural Stability and Mechanistic Approach for Superior Adsorption of Arsenate from Water. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 6917–6928. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b06489. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; Sun F.; He J.; Xu H.; Cui F.; Wang W. Robust Phosphate Capture Over Inorganic Adsorbents Derived from Lanthanum Metal Organic Frameworks. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 326, 1086–1094. 10.1016/j.cej.2017.06.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.-W.; Zhang Y.; Chen X.-W.; Wang J.-H. Graphene Oxide–Rare Earth Metal–Organic Framework Composites for the Selective Isolation of Hemoglobin. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 10196–10204. 10.1021/am503298v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancino P.; Vega A.; Santiago-Portillo A.; Navalon S.; Alvaro M.; Aguirre P.; Spodine E.; García H. A novel copper(II)–lanthanum(III) metal organic framework as a selective catalyst for the aerobic oxidation of benzylic hydrocarbons and cycloalkenes. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 3727–3736. 10.1039/C5CY01448D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.; Serre C. Toward Green Production of Water-Stable Metal–Organic Frameworks Based on High-Valence Metals with Low Toxicities. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 11911–11927. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b01022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Y.; Huang G.; Li H.; Hill M. R. Magnetic Metal–Organic Framework Composites: Solvent-Free Synthesis and Regeneration Driven by Localized Magnetic Induction Heat. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 13627–13632. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b02323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paul A.; Srivastava D. N. Amperometric Glucose Sensing at Nanomolar Level Using MOF-Encapsulated TiO2 Platform. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 14634–14640. 10.1021/acsomega.8b01968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Abetxuko A.; Morant-Miñana M. C.; Knez M.; Beloqui A. Carrierless Immobilization Route for Highly Robust Metal–Organic Hybrid Enzymes. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 5172–5179. 10.1021/acsomega.8b03559. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lian X.; Fang Y.; Joseph E.; Wang Q.; Li J.; Banerjee S.; Lollar C.; Wang X.; Zhou H.-C. Enzyme-MOF (metal–organic framework) Composites. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 3386–3401. 10.1039/C7CS00058H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao S.-L.; Yue D.-M.; Li X.-H.; Smith T. J.; Li N.; Zong M.-H.; Wu H.; Ma Y.-Z.; Lou W.-Y. Novel Nano-/Micro-Biocatalyst: Soybean Epoxide Hydrolase Immobilized on UiO-66-NH2 MOF for Efficient Biosynthesis of Enantiopure (R)-1, 2-Octanediol in Deep Eutectic Solvents. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 3586–3595. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.6b00777. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.; Li P.; Modica J. A.; Drout R. J.; Farha O. K. Acid-Resistant Mesoporous Metal–Organic Framework toward Oral Insulin Delivery: Protein Encapsulation, Protection, and Release. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 5678–5681. 10.1021/jacs.8b02089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J.; Fu Y.; Li R.; Feng W. Multifunctional Hollow–Shell Microspheres Derived from Cross-Linking of MnO2 Nanoneedles by Zirconium-Based Coordination Polymer: Enzyme Mimicking, Micromotors, and Protein Immobilization. Chem. Mater. 2018, 30, 1625–1634. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.7b04945. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T.-T.; Yi J.-T.; Zhao Y.-Y.; Chu X. Biomineralized Metal–Organic Framework Nanoparticles Enable Intracellular Delivery and Endo-Lysosomal Release of Native Active Proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 9912–9920. 10.1021/jacs.8b04457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad M.; Razmjou A.; Liang K.; Asadnia M.; Chen V. Metal–Organic-Framework-Based Enzymatic Microfluidic Biosensor via Surface Patterning and Biomineralization. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 1807–1820. 10.1021/acsami.8b16837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollegioni L.; Molla G. New biotech applications from evolved D-amino acid oxidases. Trends Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 276–283. 10.1016/j.tibtech.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du K.; Sun J.; Song X.; Song C.; Feng W. Enhancement of the solubility and stability of D-amino acid oxidase by fusion to an elastin like polypeptide. J. Biotechnol. 2015, 212, 50–55. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2015.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Signorelli A. J.; Hayes R. G. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy of Various Core Levels of Lanthanide Ions: The Roles of Monopole Excitation and Electrostatic Coupling. Phys. Rev. B 1973, 8, 81. 10.1103/PhysRevB.8.81. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramana C. V.; Vemuri R. S.; Kaichev V. V.; Kochubey V. A.; Saraev A. A.; Atuchin V. V. X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy Depth Profiling of La2O3/Si Thin Films Deposited by Reactive Magnetron Sputtering. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2011, 3, 4370–4373. 10.1021/am201021m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan X.-H.; Liu Q.; Chen G.-H.; Shang C. Surface complexation of condensed phosphate to aluminum hydroxide: An ATR-FTIR spectroscopic investigation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2005, 289, 319–327. 10.1016/j.jcis.2004.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elzinga E. J.; Sparks D. L. Phosphate adsorption onto hematite: An in situ ATR-FTIR investigation of the effects of pH and loading level on the mode of phosphate surface complexation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2007, 308, 53–70. 10.1016/j.jcis.2006.12.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai Y.; Sparks D. L. ATR–FTIR Spectroscopic Investigation on Phosphate Adsorption Mechanisms at the Ferrihydrite-Water Interface. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2001, 241, 317–326. 10.1006/jcis.2001.7773. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iremonger S. S.; Liang J.; Vaidhyanathan R.; Martens I.; Shimizu G. K. H.; Daff T. D.; Aghaji M. Z.; Yeganegi S.; Woo T. K. Phosphonate Monoesters as Carboxylate-like Linkers for Metal Organic Frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 20048–20051. 10.1021/ja207606u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iremonger S. S.; Liang J.; Vaidhyanathan R.; Shimizu G. K. H. A permanently porous van der Waals solid by using phosphonate monoester linkers in a metal organic framework. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 4430–4432. 10.1039/c0cc04779a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves J. A.; Wright P. A.; Lightfoot P. Two Closely Related Lanthanum Phosphonate Frameworks Formed by Anion-Directed Linking of Inorganic Chains. Inorg. Chem. 2005, 44, 1736–1739. 10.1021/ic048456v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigel H.; Da Costa C. P.; Song B.; Carloni P.; Gregáň F. Stability and Structure of Metal Ion Complexes Formed in Solution with Acetyl Phosphate and Acetonylphosphonate: Quantification of Isomeric Equilibria. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 6248–6257. 10.1021/ja9904181. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kluger R.; Cameron L. L. Activation of Acyl Phosphate Monoesters by Lanthanide Ions: Enhanced Reactivity of Benzoyl Methyl Phosphate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 3303–3308. 10.1021/ja016600v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigel H.; Da Costa C. P. Metal ion–carbonyl oxygen recognition in complexes of acetyl phosphate. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2000, 79, 247–251. 10.1016/S0162-0134(99)00163-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedemann T. E.; Haugen G. E. Pyruvic acid II. The determination of keto acids in blood and urine. J. Biol. Chem. 1943, 147, 415–442. [Google Scholar]

- Du K.; Zhao J.; Sun J.; Feng W. Specific Ligation of Two Multimeric Enzymes with Native Peptides and Immobilization with Controlled Molar Ratio. Bioconjugate Chem. 2017, 28, 1166–1175. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.7b00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanfins E.; Dairou J.; Hussain S.; Busi F.; Chaffotte A. F.; Rodrigues-Lima F.; Dupret J.-M. Carbon black nanoparticles impair acetylation of aromatic amine carcinogens through inactivation of arylamine N-acetyltransferase enzymes. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 4504–4511. 10.1021/nn103534d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong B.; Arnoult O.; Smith M. E.; Wnek G. E. Electrospinning of Collagen Nanofiber Scaffolds from Benign Solvents. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2009, 30, 539–542. 10.1002/marc.200800634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zha Z.; Teng W.; Markle V.; Dai Z.; Wu X. Fabrication of gelatin nanofibrous scaffolds using ethanol/phosphate buffer saline as a benign solvent. Biopolymers 2012, 97, 1026–1036. 10.1002/bip.22120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bak S. Y.; Yoon G. J.; Lee S. W.; Kim H. W. Effect of humidity and benign solvent composition on electrospinning of collagen nanofibrous sheets. Mater. Lett. 2016, 181, 136–139. 10.1016/j.matlet.2016.06.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]