Abstract

Introduction:

Community donation bins have become more common in the urban setting over the past several years. Many nonprofit organizations use these sturdy metal enclosures for unobserved collection of various donated items such as clothing, books, and household items. Although the donated items are often of low individual value, donation bins may become a target of individuals in low socioeconomic situations seeking desired items for personal use or resale, or for personal shelter within the bin.

Methods:

To identify donation bin-associated deaths, we reviewed cases taken under the jurisdiction of the coroner for investigation in the provinces of British Columbia and Ontario, Canada, over the years 2009 to 2019.

Results:

We present the circumstances and postmortem findings of five deaths that occurred in British Columbia and Ontario (Canada) between 2009 and 2019, wherein the decedents were each believed to have been reaching into donation bins and became caught within the door mechanism and died as a consequence of compression asphyxia involving the chest and/or neck.

Discussion:

Donation bins have the potential for harm when individuals attempt to access the bin contents through the entry portal. We advocate for greater attention and changes in the placement location and/or design of these potentially dangerous devices.

Keywords: Forensic pathology, Donation bin, Compression, Traumatic, Mechanical, Asphyxia

Introduction

Community donation bins have become more common in the urban setting over the past several years. Many nonprofit organizations use these sturdy metal enclosures for unobserved collection of various donated items such as clothing, books, and household items. Although the donated items are often of low individual value, donation bins may become a target of individuals in low socioeconomic situations seeking desired items for personal use or resale, or for personal shelter within the bin. Simple bins are designed with a square opening and no door ( Figure 1 : left), while other bins have a “mailbox chute” ( Figure 1 : middle). Alternatively, many bins are designed with a tamper-resistant door mechanism such as the “rolling chute” (sometimes termed “roll-up chute”) design wherein the donated items are placed into the metal trough/chute, and the items are only deposited into the base of the bin once the trough/chute is turned approximately 90° via lifting a handle ( Figure 1 : right, Figure 2A, B ). Although the design of these tamper-resistant bins deters casual theft, personal physical harm can arise if an individual seeks to access the contents of the bin via the narrow entryway ( Figure 3 ).

Figure 1:

Examples of three styles of donation bins. Left—simple entryway. Middle—mailbox chute style. Right—rolling chute style. (Image created by TBMH).

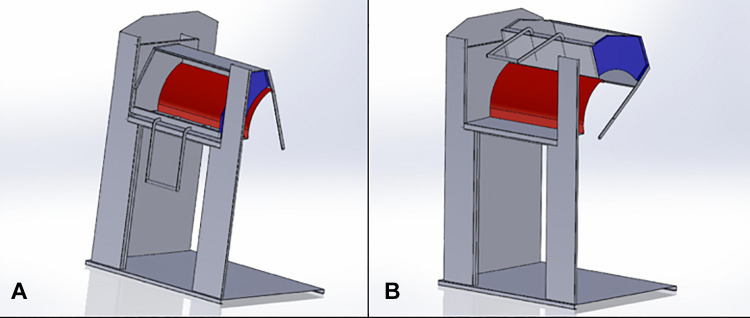

Figure 2:

A and B, Example of rolling chute donation bin mechanism. A, Door closed (resting) position. B, Door open (raised) position. (Images used with permission: Rangeview Fabrication).

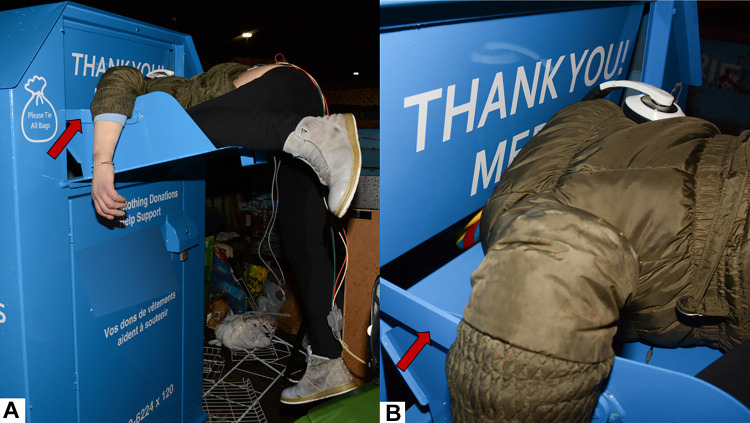

Figure 3:

A and B, The positioning of the decedent in case 5 when found. Electrocardiogram tabs and wiring had been applied by emergency medical services (EMS) prior to photography. A, Note the decedent’s legs are dangling, with full body weight on the opened door. B, Note the inner door is impinging upon the neck. The hinge mechanism that causes the inner door to close when the outer door is opened is shown by the red arrow in each image. (Images used with permission: Toronto Police Service).

Compression (also known as mechanical, crush, traumatic) asphyxia refers to a form of suffocation where pulmonary respiration and/or vascular flow is impeded by external pressure(s) on the body. This may take the form of a heavy weight compressing the neck, chest, abdomen, or wedging of the body within a narrow space (1). This phenomenon as a cause of death has been observed due to compression against inanimate objects, for example, within a crushed motor vehicle (2), car doors (3), revolving doors (4), bar bells (5), or from sustained external chest compression by another individual (6).

Methods

Approval of a research agreement adhering to the standards of the British Columbia Coroner’s Act was obtained through the British Columbia Coroners Service (BCCS). Both the BCCS and the Office of the Chief Coroner of Ontario provided permission to complete a retrospective review of their databases to identify and describe cases that involved deaths related to individuals caught within donation bins. Where available, history and scene information, and forensic pathology findings were obtained and reported in brief.

Results

We identified five coroner-completed cases (of seven total British Columbia and Ontario cases) where individuals died as a result of becoming entrapped with the entry-door of community donation bins. Where available, the official medical cause of death is provided. Details of each case are provided below, and a summary of pertinent case information is provided in Table 1.

Table 1:

Summary Information of the Five Compression Asphyxia Deaths Involving Community Donation Bins in Ontario and British Columbia.

| Case # | Age/Sex | Height (feet, inches) | Weight (lbs) | BMI | Time of day | Season | Bin type | Location | Postmortem examination | Cause of death | Drugs detected | Associated diseasesa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 45F | N/A | N/A | N/A | Night | Fall | Rolling chute | Store parking lot | Coroner External | Anoxic brain injury d/t asphxyiation d/t neck caught in a donation bin. | Amphetamine | Nil |

| 2 | 29M | 5’6" | 154 | 24.2 | Night | Summer | Rolling chute | Street boulevard | FP Full | Mechanical asphyxia | Methamphetamine, fentanyl, codeine. | Nil |

| 3 | 20M | N/A | N/A | N/A | Night | Summer | Rolling chute | Vacant private lot | FP Full | Asphyxia d/t external neck compression d/t entrapment in donation bin. | Methamphetamine | Nil |

| 4 | 33M | 5’5" | 150 | 25 | Night | Fall | Rolling chute | Outside community center | FP Full | Traumatic asphxia in the setting of methamphetamine toxicity. | Methamphetamine | Nil |

| 5 | 35F | 5’5" | 158 | 26.3 | Night | Winter | Mailbox | Apartment parking lot | FP Full | Asphyxia d/t neck compression d/t donation bin entrapment. | Methamphetamine, fentanyl, cocaine. | Nil |

a The associated diseases column refers to identified diseases that could have contributed to death.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (kg/m2); d/t = due to; FP Full, autopsy completed by a forensic pathologist that included at least an external and internal examination of the body; N/A, describes data that was not available.

Case 1

A 45-year-old woman was observed by a store employee at a shopping center to be reaching into a rolling chute style donation bin and kicking her legs in an attempt to reach further into the bin. Approximately 1 hour later, the same employee saw the woman hanging out of the donation bin, unresponsive. Emergency medical services (EMS) were called and the pulseless woman was extricated from the bin and resuscitation efforts were commenced. Return of spontaneous circulation was achieved by EMS, however, the woman was found to have evidence of irreversible hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy and died in the intensive care unit of a regional hospital approximately 24 hours later.

External examination by the coroner identified bruising on the decedent’s neck with no other evidence of injury. Qualitative hospital toxicology screening detected amphetamine. The cause of death was established as: Anoxic brain injury, due to asphyxiation, due to neck being caught in a donation bin.

Case 2

A 29-year-old man was found by a passerby in the early morning hours with the lower half of his body protruding from a rolling chute style donation bin. Emergency medical services attended, however, the decedent could not readily be extricated, and the donation bin needed to be cut in order to get him out. Once extricated, resuscitation efforts were unsuccessful.

External examination by a forensic pathologist demonstrated multiple abrasions on the neck. Layered neck dissection revealed hemorrhage of the superficial and deep strap muscles, hyoid bone fracture, and posterior neck soft tissue hemorrhage. No evidence of significant natural disease was identified. Quantitative toxicological analysis identified the presence of methamphetamine, amphetamine, fentanyl, codeine, and morphine. The cause of death was determined to be: Mechanical asphyxia.

Case 3

A 20-year-old man living in a recovery house was first observed by a passerby to be deep within a rolling chute style donation bin with only his lower legs protruding out of the bin, motionless. The fire department was required to extricate the decedent from the bin. Once removed, the man was without vital signs and death was pronounced after resuscitation efforts by EMS were unsuccessful.

Autopsy findings included bruising of the neck (subcutaneous tissues and anterior neck muscles) and no other significant injuries to the body or natural diseases. Toxicological testing of the blood showed the presence of methamphetamine. The cause of death was established as: Asphyxia, due to external neck compression, due to entrapment in donation bin.

Case 4

A 33-year-old man of no fixed address was found partially wedged in a rolling chute style clothing donation bin. There was a chair beside the bin, and it appeared that he had been trying reach into the bin and slipped possibly due to the heavy rainfall, causing the antitheft mechanism to trap him inside the opening. His legs were hanging from the bin, with his torso trapped between the sloped door and door frame. His head and arms were inside the bin. Emergency medical services attended the scene and found him without vital signs. The local fire department extricated the body.

At autopsy, the decedent was dressed in multiple layers of clothing. His pockets contained drug paraphernalia and there was evidence of previous self-harm. There were two red abrasions on the anterior neck and a patterned crush abrasion. A layered dry neck dissection revealed a small area of hemorrhage on the inferior aspect of the left lobe of the thyroid. There was no hemorrhage into the soft tissue and muscles of the neck. There was an abraded contusion over the lower right side of the chest wall. A layered torso examination revealed two small areas of subcutaneous hemorrhage on the left lower abdomen. Toxicologic analysis was positive for methamphetamine and amphetamine at a level which can be associated with recreational use. The cause of death was traumatic asphyxia in the setting of methamphetamine intoxication.

Case 5

A 35-year-old woman of no fixed address with chronic mental illness and stimulant drug use was heard yelling for help and appeared to be stuck within a mailbox style community donation bin. Emergency medical services attended and could not readily extricate the woman as the donation bin entry door was pinching the decedent at the level of her head and neck ( Figure 3A, B ). Emergency medical services applied monitoring equipment and found she was in asystole. The fire department needed to use a metal saw to open the bin and extract the deceased woman.

Autopsy demonstrated abrasive injuries of the face and neck with underlying multifocal hemorrhage of the anterior neck muscles and focal bruising of the upper chest. Toxicological testing of the blood was positive for fentanyl, cocaine, and methamphetamine. The cause of death was established as: Asphyxia due to external neck compression due to donation bin entrapment. Additionally, it is noted that there was no natural disease that may have been contributed to death identified in any of the five decedents (Table 1).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first research description of deaths resulting from complications of individuals becoming entrapped within the door mechanisms of community donation bins. In addition to the five cases described herein, we are aware of two additional deaths in British Columbia involving donation bins occurring in 2016 and 2018 (T. Sidhu, personal communication, January 10, 2020). One involved a 39-year-old woman caught within a rolling chute style bin and the other was a 34-year-old man caught within a mailbox-style bin. As the coroner investigations were not completed at the time of manuscript submission, no additional information on examination findings or official cause of death can be provided. We are also aware of two deaths of men aged 20 to 40 years old that occurred in the province of Alberta, Canada, within the past five years and were described as “compressional type asphyxia deaths” (M. Weinberg, personal communication, January 10, 2019). Given this, we are aware of nine donation bin-associated deaths in Canada. Although death investigation in Canada is overseen provincially, we feel this study illustrates the value of interprovincial data sharing and forensic pathologist involvement as a means of identifying unsafe infrastructure in communities and supporting enhancement of public safety.

Compression (also known as mechanical, crush, traumatic) asphyxia refers to a form of suffocation where cardiopulmonary function is restricted by external pressure(s) on the body. This may take the form of a heavy weight compressing the neck, chest or abdomen, or wedging of the body within a narrow space. Byard et al. reviewed causes of compression asphyxia for their region over a 25-year period and determined the majority of cases involved motor vehicles; wherein the decedent was trapped in a vehicle due to motor vehicle collision or caught underneath a vehicle.(1) Compression by a car door can also cause death.(3) Industrial accidents and farm accidents also represent a significant number of cases of compression asphyxia.(1) In the city-setting, hazards may include revolving doors,(4) weight lifting apparatus,(5) or as we have described here, donation bins. Additionally, compression asphyxia may result from sustained external chest compression due to the weight of another individual(6) or from the weight and positioning of one’s own body, as described in cases of positional asphyxia (7).

Establishing the cause and manner of death in cases of compression asphyxia requires a thorough death investigation. This includes: scene documentation (e.g., comprehensive scene and decedent photography and examination of the body by a coroner, forensic pathologist, or other death investigator), full external and internal examination of the body (including layered dissection at sites of potential external compression such as the neck, chest, and back), and ancillary studies as necessary to exclude competing causes of death (e.g., histology, toxicology, medical imaging). Although supportive findings may be identified (e.g., neck and torso contusions and abrasions, facial plethora with petechial hemorrhages), the determination of compression asphyxia is generally a diagnosis of exclusion in the context of appropriate scene and circumstances.

It is estimated that approximately 12 000 donation bins exist in Canada, including an estimated 7000 mailbox-style bins, 2000 rolling chute-style bins, and 3000 bins of alternate designs (J. Luison, personal communication, January 3, 2019). The proliferation of free-standing donation bins reduces the need to make material donations at stores/organizations at specific times of day, and provides a source of income for many charities. In this regard, donation bins serve a positive role. However, for individuals in need, there may be incentive to seek access to the bins for either shelter or to obtain items for personal use or resale, even it means taking some personal risk. An example of this is the theft of live electrical wiring for copper content, despite obvious electrocution risk (8). As a deterrent against theft, the mailbox style bin may have a mechanism that closes an inner door when the outer door is opened ( Figure 3A , B -arrows), as observed in one of our cases (case 5). Alternatively, many bins use a design termed the “rolling chute” (or “roll-up chute”) wherein items are placed in a trough/chute and then a lever is raised to drop the items into the bin, as observed in four of our five cases (cases 1, 2, 3, and 4). Both designs deter theft in that there is never a direct open passage into the bin. However, a motivated individual may contort their body to squeeze through the narrow passageway over the rotating chute. Injury can result by forcing one’s head, neck, and upper body through the narrow opening between the chute opening and the door frame and/or ceiling of the bin. Furthermore, there is a natural upward force into the area of the upper body and neck during the process of trying to enter the bin, as the lower body and legs continue to depress the lever mechanism such that is chute opening is trying to close (see Figures 2A , B and 3A , B). Direct pressure on the neck can initially limit venous outflow of the brain, and stronger pressures may occlude cerebral arterial inflow and potentially cause airway compression. Compressive pressure on the chest may be mechanically obstructive, limiting the capacity for the individual to appropriately expand the chest and resulting in hypoventilation. Asphyxia resulting from cerebral hypoxia with loss of consciousness and subsequent death may result from either of these circumstances or a combination of both.

We also observed that toxicological testing of the blood identified the stimulant compounds of methamphetamine and/or amphetamine in all five cases. Two individuals also tested positive for opioid drugs and one also was positive for the stimulant drug cocaine (Table 1). Given the small sample size of this study, the finding of stimulant drugs in all individuals tested may only be coincidence. However, it is considered that use of recreational stimulant drugs may be an enabling factor for individuals to overcome the physical and exertional challenges of squeezing into a donation bin opening. Also, the increased cardiorespiratory drive (e.g., tachycardia, hypertension, and tachypnea) associated with stimulant drug use may increase the risk of sudden cardiac arrhythmia secondary to physical struggle in the setting of compression asphyxia; perhaps akin to the physiological changes observed in deaths associated with excited delirium (9).

It is uncertain how best to prevent compression asphyxia deaths in donations bins. During the course of this research, we confirmed that the coroner’s services of the involved provinces were aware of these deaths and exploring options for enhancing bin safety. A simple approach is the application of a warning label on the bin indicating the risk for injury and death if the bin is tampered. However, the donation bin associated with case 3 had a warning label that read “if you enter or reach into this bin you may die or be seriously injured.” As such, it is unclear if such warning labels will sufficiently reduce injury and/or death. Another consideration is a change in the location of the donation bins. It could be argued that placing the bins in areas of greater visibility with increased foot traffic may be one harm reduction approach. Alternatively, given that these deaths appear to be more likely occur at night (Table 1), placing bins in areas that can be locked off during the evening (e.g., rolling the bins into a secured garage or shed) may improve safety. Lastly, the optimal solution may be that the bin designs need to be improved. Deaths in our study were associated with both the rolling chute (4/5) ( Figure 1 : right) or the mailbox style (1/5) ( Figure 1 : center) bins. We are not aware of any deaths associated with the simple entryway style bin ( Figure 1 : left). In response to the most recent deaths in British Columbia, the city of Vancouver temporarily banned donation bins while they researched the scope of the donation bin safety issues and described approaches to donation bin regulations in other Canadian jurisdictions.(10) Subsequently, the city mandated changes via by-law amendments and required donation bin operators to obtain specific business licences, closely monitor all approved bin locations, and have a professional engineer verify safety of the bin design (10). Establishing what constitutes a safe bin design and developing a baseline standard for bin safety was undertaken via a collaborative effort by individuals and organizations including: a major Canadian donation bin fabricator, affected municipalities (e.g., cities of Toronto and Vancouver), universities and engineering professionals (J. Luison, personal communication, January 3, 2019). Through this process, two primary changes to existing bin designs (mailbox and rolling chute styles) were identified with the goal to reduce/eliminate the potential for harm. The mailbox style bin was made safer by disengaging the metal mechanism that caused the inner door to close when the outer door was opened. This hinge mechanism is shown by the arrows in Figure 3A, B . The rolling chute style bins were made safer by retrofitting a metal insert to better restrict potential access to the small bin opening. An example of this change is shown in a video produced by a bin manufacturer (https://vimeo.com/310162178). Although no national data exists on the commitment of bin operators to embracing these safety enhancements, it is estimated that the majority of mailbox and rolling chute-style donation bins in Canada have undergone these safety improvements (J. Luison, personal communication, January 3, 2019).

Conclusion

We present the circumstances and postmortem findings of five deaths that occurred as a result of individuals attempting to reach into community donation bins and becoming caught within the door mechanism and dying as a consequence of compression asphyxia. Autopsy findings included blunt force compressive injuries of the neck and chest (e.g., bruises, abrasions, and a hyoid fracture). Also, it was observed that methamphetamine and/or amphetamine were detected in all cases where toxicological testing of the blood was completed. To reduce the risk of these deaths, we advocate for by-law enforced changes in the placement location and/or design of these potentially dangerous devices.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the following individuals and organizations for their support of this research by providing unpublished data, images, and supportive information: J. Luison (Rangeview Fabrication), T. Sidhu (British Columbia Coroners Service), M. Weinberg (Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Alberta, Canada), J. Herath (Ontario Forensic Pathology Service), J. Maxwell (Ontario Forensic Pathology Service), and the Toronto Police Service.

Footnotes

Ethical Approval: As per Journal Policies, ethical approval was not required for this manuscript.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: This article does not contain any studies conducted with animals or on living human subjects.

Statement of Informed Consent: No identifiable personal data were presented in this manuscript.

Disclosures & Declaration of Conflicts of Interest: The authors, reviewers, editors, and publication staff do not report any relevant conflicts of interest.

Financial Disclosure: The authors have indicated that they do no have financial relationships to disclose that are relevant to this manuscript.

ORCID iD: Tyler Bruce Malcolm Hickey https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0633-4058

References

- 1. Byard RW, Wick R, Simpson E, Gilbert JD. The pathological features and circumstances of death of lethal crush/traumatic asphyxia in adults—A 25-year study. Forensic Sci Int. 2006;159(2-3):200–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pathak H, Borkar J, Dixit P, Shrigiriwar M. Traumatic asphyxial deaths in car crush: report of 3 autopsy cases. Forensic Sci Int. 2012;221(1-3);e21–e24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Byard RW, Woodford NWF. Automobile door entrapment—A different form of vehicle-related crush asphyxia. J Forensic Leg Med. 2008;15(5):339–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cortis J, Falk J, Rothschild MA. Traumatic asphyxia—fatal accident in an automatic revolving door. Int J Legal Med. 2015;129(5):1103–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jumbelic MI. Traumatic asphyxia in weightlifters. J Forensic Sci. 2007;52(3):702–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Miyaishi S, Yoshitome K, Yamamoto Y, Naka T, Ishizu H. Negligent homicide by traumatic asphyxia. Int J Legal Med. 2004;118(2):106–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chmieliauskas S, Mundinas E, Fomin D, et al. Sudden deaths from positional asphyxia: a case report. Medicine. 2008;97(24):e11041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Taylor AJ, McGwin G, Brissie RM, Rue LW, Davis GG. Death during theft from electric utilities. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2003;24(2):173–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gill JR. The syndrome of excited delirium. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 2014;10(2):223–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vancouver City Council. Regulating clothing donation bins. 2019. Vancouver City Council website: https://council.vancouver.ca/20190528/documents/a2.pdf (accessed: July 24, 2020).