Abstract

Background:

The global COVID-19 pandemic has left health and social care systems facing the challenge of supporting large numbers of bereaved people in difficult and unprecedented social conditions. Previous reviews have not comprehensively synthesised the evidence on the response of health and social care systems to mass bereavement events.

Aim:

To synthesise the evidence regarding system-level responses to mass bereavement events, including natural and human-made disasters as well as pandemics, to inform service provision and policy during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond.

Design:

A rapid systematic review was conducted, with narrative synthesis. The review protocol was registered prospectively (www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero, CRD 42020180723).

Data sources:

MEDLINE, Global Health, PsycINFO and Scopus databases were searched for studies published between 2000 and 2020. Reference lists were screened for further relevant publications, and citation tracking was performed.

Results:

Six studies were included reporting on system responses to mass bereavement following human-made and natural disasters, involving a range of individual and group-based support initiatives. Positive impacts were reported, but study quality was generally low and reliant on data from retrospective evaluation designs. Key features of service delivery were identified: a proactive outreach approach, centrally organised but locally delivered interventions, event-specific professional competencies and an emphasis on psycho-educational content.

Conclusion:

Despite the limitations in the quantity and quality of the evidence base, consistent messages are identified for bereavement support provision during the pandemic. High quality primary studies are needed to ensure service improvement in the current crisis and to guide future disaster response efforts.

Keywords: Bereavement, grief, pandemics, disasters, disease outbreaks, coronavirus infections

What is already known about the topic?

Health and social care systems are facing the unprecedented challenge of supporting those bereaved during COVID-19, a disease characterised by risk factors for poor bereavement outcomes.

Recent reviews of the evidence to inform bereavement support during COVID-19 have focused on end of life and immediate post-death support and the impact of previous pandemics on grief and bereavement.

Evidence synthesis relating to bereavement interventions following other types of mass bereavement disasters could help to inform the response of health and social care systems to the ongoing global crisis.

What this paper adds

Six studies were identified which provided evidence on system responses to bereavement support in the aftermath of a variety of 21st century human-made and natural disasters.

None of the included studies described bereavement support programmes in the context of pandemics, and none were of high quality.

However, several key service features were identified across interventional approaches: proactive outreach to those in need; central coordination of locally delivered support; training for providers in crisis-specific core competencies; structured psycho-education as well as group-based support and use of existing social networks; formal risk assessment for prolonged grief disorder and referral pathways for specialist mental health support.

Implications for practice, theory and policy

Policy makers and those delivering services should design or adapt bereavement support to reflect the findings above; this will include advertising services widely to enable access to support for those who need it, providing training in core competencies specific to the COVID-19 context and providing options for individual and group support in the context of social distancing restrictions.

In addition, bereavement support providers including palliative care services should integrate prospective evaluation alongside service delivery and ensure real-time feedback to inform practice.

Policy makers should consider how best to integrate bereavement support in wider population-level support for the social and psychological consequences of COVID-19.

Background

At the time of writing, COVID-19 has resulted in 413,000 deaths worldwide, with an estimated 2 million people bereaved since the virus was first reported in Wuhan in December 2019. Globally, health and social care systems are facing the unprecedented challenge of supporting those who are grieving, while continuing to treat those with severe disease and prevent the virus from spreading exponentially. It is a time of great uncertainty,1,2 with the burden and course of future disease still unclear.

COVID-19 deaths are characterised by risk factors for poor bereavement outcomes, including prolonged grief disorder (PGD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and poor mental health.3,4 In secondary care and community settings, family members may not have access to their loved one prior to death, due to infection control requirements and the need to protect those highly vulnerable to the disease. Social distancing requirements mean that funerals are restricted and the bereaved may have to grieve alone, without the comfort of their loved ones. With many workplaces closed, the bereaved may also face economic hardship. Not being able to say goodbye, loss of social and community networks, living alone and loss of income are all associated with poor bereavement outcomes and will affect people bereaved by all illnesses in this period, not just COVID-19.5,6

The research community has reacted quickly to the COVID-19 crisis, with recent narrative reviews and commentaries identifying evidence-based recommendations for staff providing end-of-life and immediate post-death support to families.4,7,8 Another recent rapid review has synthesised the evidence regarding the impact of pandemics on grief and bereavement,9 but did not find evidence relating to bereavement support. Anticipating a lack of research relating to this and past pandemics, we sought to draw lessons from the evidence relating to bereavement support interventions following other types of natural and human-made disasters and terror attacks, as well as pandemics. It is hoped that this learning can guide the response of health and social care systems to the tsunami of bereavement they are currently facing during this ongoing global crisis.

This review aimed to synthesise the evidence regarding system-level responses to mass bereavement events, to inform service provision and policy during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. As key providers of bereavement support in the UK and internationally, review findings will have relevance for palliative care organisations as well as other national providers.

Methods

A rapid narrative systematic review was conducted which aimed to identify the key elements of effective bereavement support in times of mass bereavement and relevant implications for bereavement support provision during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK.

The review was conducted in accordance with palliative care evidence review service (PaCERS) modified systematic review methodology.10 This approach was developed to enable the rapid and robust assessment and reporting of clinical evidence following requests from palliative care practitioners in Wales. An initial request for this review was made by the Lead Clinician of the End of Life Care Board in Wales and the need for rapid synthesis and timely reporting during the ongoing pandemic favoured the application of this methodology. The review is reported following the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guideline.11 The protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) on 22 April 2020 (CRD42020180723).

Search strategy

A systematic search was conducted on 3 April 2020 across six databases: Ovid Medline All (which includes In-Process and other Non-Indexed Citations), In-Data-Review and PubMed-not-MEDLINE records from National Library of Medicine, Ovid PsycINFO, Ovid Global Health and Elsevier Scopus.

The search strategy was developed in Ovid Medline using a combination of text words and Medical Subject Headings, with dates limited to January 2000 to 3 April 2020 (see Supplementary File 1: search strategies). The search strategy consisted of a combination of list of synonyms in two categories, bereavement and pandemics and other disasters. Searches were limited to English language publications.

To identify additional papers, we searched Evidence Aid (https://www.evidenceaid.org/) and conducted forward citation tracking on included study reports. We also reviewed the reference lists of systematic reviews and included study reports to check for any additional relevant references.

Study selection

All references identified by the searches were downloaded into Endnote and deduplicated. This was followed by initial screening to remove irrelevant articles. Subsequently, titles and abstracts were independently dual-screened for inclusion; disagreements were adjudicated by a third reviewer. Full-text articles were retrieved for remaining records and independently dual-screened, with discrepancies resolved by discussion or by recourse to a third reviewer. Due to the need for timely completion and results that are of optimal relevance to UK policy and practice during the ongoing pandemic, our review was time-limited to studies published from 2000 onwards and conducted in countries with economies and health and social care systems comparable to the UK. Due to the predominantly older age range of COVID-19 deaths, the review also focused on support for adults or families grieving adult deaths, rather than child-focused support or support for families grieving the loss of children (Table 1).

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| • Empirical studies related to large scale community or

population events since 1990 resulting in large numbers of

sudden or rapid deaths • Studies conducted in health and social care economies relevant to the UK • Studies of systems approaches to bereavement support and effective domains: timing, place and pre-bereavement healthcare approaches |

• Study reports published before 2000 • Support that is only provided to children or young people (aged under 18) • Support that is predominantly for people grieving the loss of a child (aged under 18) • Systems not relevant to UK health and social care context • Opinion pieces or theoretical frameworks, where no primary data were reported • Studies in non-OECD countries (except Singapore, China and Taiwan) • Book chapters • Case reports |

OECD: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Data extraction

A standardised data extraction form was developed for the review. Data extraction was completed by one reviewer and checked against the original article by a second reviewer, who added to the data extracted where needed. Where more than one paper was identified reporting the same study, data from these papers were extracted and combined in one data extraction form. Any differences in the data extraction were resolved through discussion, with an independent reviewer consulted where needed.

Quality assessment

Quality assessment was conducted on all included studies using the appropriate checklist from the Specialist Unit for Review Evidence (SURE).12 Where several papers reported the same study, quality was assessed once for the overall study. Quality assessment was completed independently by one reviewer and checked for accuracy by a second reviewer. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion or by consulting a third reviewer. These assessments are used to give an indication of the strength and reliability of the evidence when reporting and discussing study findings.

Data synthesis

Due to the heterogeneity of the included studies and our wish to present a detailed narrative of results, the PaCERS methodology was extended to include a narrative synthesis approach, which integrated and described the results of the included studies.13 The study design, study setting, included population, intervention examined and stated outcomes were tabulated. Study details are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2.

Study characteristics and results.

| References | Country | Intervention | Study design | Study objectives | Sample characteristics (N) | Outcomes/methods | Key results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broms25 | Sweden | Programme organised by Ersta Association for Diaconal Work

(Ersta) to support Swedish survivor families of South-East

Asian Tsunami 2004 Multi-agency support was provided between January 2005 and August 2007 including: (a) Support groups for bereaved (14 age specific groups) and non-bereaved survivors (b) Memorials and rituals (c) Drop in weekly meetings (d) Individual counselling (e) Three weekend gatherings (f) Day seminars with plenary and group sessions to deal with crisis and grief (g) Focused groups relaxation and sleep therapy |

Retrospective evaluation (descriptive study and preliminary evaluation) | To identify what needs the survivors had and how professionals should support survivors during similar events in the future. | Support provided to 1362 Swedish survivors, adults,

teenagers, children and grandparents who were grieving,

injured and traumatised. Not clear how many participants were in receipt of different types of support |

Evaluation included reports and documentation (personal communications and notes) of the initiatives during the 32-month period and a group discussion with participants from one of the bereavement support groups |

Several benefits were identified for programme

components: Support groups enabled sharing of experiences, understanding of own and others experiences, normalising of grief experiences, looking towards recovery and hope for the future. Seminars provided reassurance and promoted a sense of safety to participants. Weekend gatherings – participants valued connectedness with other survivors. It was also observed how those who did not take up professional support showed signs of resilience (naturally emerging groups who organised their own support) |

| Donahue et al.14

Donahue et al.15 Covell et al.16 Covell et al.17 Frank et al.18 Jackson et al.19 Jackson et al.20 |

USA | Project Liberty was a collaboration between New York Office

Mental Health, local governments and nearly 200 local

agencies. Its main goal was to alleviate psychological

distress experienced by New York residents as a result of

9/11 terror attacks (September 2001) The programme provided free community-based disaster mental health services to over 1 million people, including public education, group and predominantly individual counselling The counselling services aimed to support clients to identify and understand their response to loss, review their options, provide emotional support and connect them with existing social support. Clients with more complex needs were referred to specialist local services |

Longitudinal outcome evaluation14 | 1. To assess the relative impairment of individuals who

received enhanced services, compared with those receiving

only crisis counselling 2. To determine whether the provision of additional services resulted in better outcomes for enhanced services recipients |

Crisis counselling (n = 153, T1

only) Enhanced service (n = 93 T1, n = 76 T2) |

Outcomes below were used at T1 and T2 (on average 7 weeks

later), to fulfil two objectives Complicated grief Depression Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) Daily functioning |

Enhanced services recipients had more symptoms of

depression, grief traumatic stress and poorer daily

functioning when compared to crisis counselling recipients

(T1). At follow-up enhanced services, respondents reported significantly fewer symptoms of depression and grief and slightly less traumatic stress and improvement in three functioning domains (job/school, relationships and household activities) |

| Crisis counselling services were available until December

2003. In June 2003, Project Liberty also introduced an

enhanced therapy service delivered by specially trained,

licenced mental health professionals, for people showing

complicated grief symptoms

(22 months + post-disaster) This support included techniques for recognising post-disaster distress; developing skills to cope with anxiety, depression and other symptoms; and teaching cognitive reframing. It also provided information about natural grieving processes and traumatic grief symptoms and included strategies for dealing with loss and for reengaging in satisfying life activities. The enhanced service closed to new clients in December 2003 |

|||||||

| Analysis of service use data Donahue et al.15 Covell et al.16,17 |

To determine who used the service, how they used it and if

reflective of local demographic characteristics and

estimated need.15

To determine changes in the rates at which people sought access to services according to risk category16 To describe characteristics of counselling clients that predicted referral to intensive mental health treatments over the 2-year period after 91117 |

A total of 753,015 service encounter logs were analysed15

465,428 logs of first visit service encounters over 27 months16 684,500 logs of service encounters for individual counselling sessions17 |

Service logs analysed to (a) Determine rates of use by different demographic groups and to evaluate patterns of use over time15 (b) Proportion number of first visits across following risk categories16 (bereaved family member, persons directly affected, rescue workers, school children, displaced employed and unemployed, persons with disabilities and general population) (c) Organise recorded event reactions into domains relating to PTSD, functional impairment and depression(behavioural, emotional, |

687,848 individual crisis counselling sessions were provided

to an estimated 465,428 individuals, including large numbers

of persons from racial or ethnic minority

groups. Most services were provided in community settings rather than provider offices. Demographic characteristics were generally representative of the local areas and estimated need15 Individuals who lost family members accounted for 40% of visits in the first month but dropped to 5% or fewer visits by fifth months Uniform personnel used disproportionately larger percentages of services after the first year |

|||

| physical and cognitive) and identify characteristics that predicted referral to specialist services17 | Occupationally displaced and unemployed workers sought

counselling at relatively steady rates16

Overall, about 9% of individual counselling visits ended with a referral to professional mental health services The strongest predictor of referral was having reactions that fell into multiple of the four domains. Those who had greater attack-related exposure were also more likely to be referred17 |

||||||

| Cross-sectional survey19,20 | To assess service user satisfaction with counselling services19

To determine the likelihood and predictors of Project Liberty counselling recipients’ achieving satisfactory life functioning 16–26 months post 91120 |

607 Project Liberty service recipients completed

questionnaires, telephone interviews, or both Crisis counselling questionnaires (n = 453) Crisis counselling telephone interviews (n = 153) Enhanced service telephone interviews (n = 93) 38% (n = 229) had lost family members or friends in attacks |

11 aspects of service quality and four domains of

effectiveness was assessed for counselling services offered

through Project Liberty19

The effectiveness domains were used to assess pre-attack and level of functioning at time of interview/questionnaire20 Effectiveness domains included Job/school, relationship, daily activities, physical health and community activities. Service quality dimensions included respect for client, willingness to listen, cultural sensitivity, speaking the same language as the client, amount of counselling time, convenience of meeting time and location, information received, whether the service would be used again/recommended to friends or family and overall quality of service |

At least 89% of service recipients rated Project Liberty as

either good or excellent across the 11 service quality

dimensions and the four effectiveness domains The counsellor’s respect for clients and his or her cultural sensitivity were rated particularly favourably19 In the five effectiveness domains, 77%–87% of the sample reported good to excellent functioning in the month before the attacks, 55%– 68% reported returning to at least the same level of daily functioning after the attacks African Americans were two to four times more likely to report a return to good or excellent functioning after the attack in four domains Clients that lost their job were less likely to return to good pre-attack functioning in two domains20 |

|||

| Analysis of project data18 | A three-phase multifaceted, multi-lingual media campaign advertised the availability of counselling services. This study evaluated the association between patterns of spending and the volume of calls received and referred to a counselling programme | N/A | Spending on television, radio, print and other advertising was examined in relation to the corresponding volume of calls to the NetLife hotline seeking referrals to counselling services | From September 2001 to December 2002, $9.38 million was spent on Project Liberty media campaigns. Call volumes increased during months when total monthly expenditures peaked. Temporal patterns show that in periods after an increase in media spending, call volumes increased. This was independent of other significant events such as the 1-year anniversary of the attacks | |||

| Dyregrov23 | Norway | A collective assistance approach consisted of four weekend

gatherings over 18 months. The weekends involved rituals,

plenary activities and small group meetings led by

psychiatrists and psychologists The programme aims to normalise and validate people’s experiences and reactions, mobilise mutual support in families, support self-management and early identification and referral The paper discusses weekends that were run following a Norwegian maritime disaster (1999) in which 16 people died |

Cross-sectional survey | Article describes development and implementation of collective assistance programme in response to Scandinavian disasters | Family members/loved ones bereaved by the disaster It is not known how many or which relatives/loved ones attended the programme |

Assessment of family satisfaction with the programme using

feedback questionnaires Reflections of group leaders on key processes and learning were sought |

96% of participants reported that gatherings were useful and

helped them in their journey. Important experiences were

identified as follows: • The extent and duration of the support must be clear and communicated at the start of the programme. • Group leaders training and preparedness, with written feedback provided to mental health coordinator after each weekend. • Participant feedback used to inform real-time programme development. • Resourcing and readiness to assist in special circumstances (e.g. missing person/bereaved from other cultures) |

| Dyregrov et al.21 | Norway | State funded and co-ordinated programme of support following

terrorist attacks on government buildings in Oslo and the

island of Utoya in Norway in July 2011. The programme

involved the following: • Proactive, structured and continuous support offered to each bereaved person by local municipal services, involving a trained health/social care professional (weekly up to 1 year) • Practical assistance, advice and referral for specialist support Access to four weekend group interventions (see Dyregrov22) |

Longitudinal mixed methods study | To investigate the experience of public service support for bereaved relatives of terror attack victims | 67 parents and 36 siblings of 69 people killed during the

attacks There were no significant differences in age or gender in the biological parents and siblings who participated, compared to the families of the deceased who did not participate (n = 19) |

Paper reports on data collected in self-completed

questionnaires 18 months post-event Questionnaires with open and closed questions were used to 1. Identify the nature of the services which were offered to the bereaved after the terror attacks 2. Assess whether the services offered were proactive and whether they met the needs of the bereaved |

95% (n = 98) of all survey participants

reported to have received support 67% (n = 69) of respondents reported a high or fairly high degree of need for help 76% (n = 51) of parents received support from their GP and family counselling services Roughly two-thirds of siblings and parents received support from psychologist/psychiatrist 42% (n = 15) of siblings received support through school 73% (n = 75) of all respondents were highly or fairly satisfied with the help received from professionals Themes from free text data included as follows: • Stressful experience Lack of competence/rapport/continuity of support • Advice for future support Proactive, empathic and competent support; access to multiple levels of support tailored to individual needs • Barriers to help Recognising need and feeling able to take help; practical and organisational barriers |

| Dyregrov22 | Norway | Following the July 2011 terror attacks in Norway, four

structured weekend gatherings were delivered by the Centre

for Crisis Psychology (CCP), to provide support to bereaved

family members The weekends included group sessions, plenary lectures, workshops and social activities, with a focus on processing and learning about grief Sessions were held 4, 8, 12 and 18 months after the attacks |

Cross-sectional survey Qualitative feedback |

To describe a programme of weekend family gatherings to help bereaved families who lost a close family member during the Utoya Island attack | Parents, siblings and close relatives of victims killed in

the attack Participants in the four weekends ranged between

182 and 224. Between 50 and 60 of the participants were

below the age of 18. Feedback was obtained from between 136 and 157 adults after the gatherings |

Participant feedback gathered through questionnaires

completed after each weekend Reflective group session conducted during final weekend Notes sent to weekend organisers |

Over 90% of adult participants found weekends extremely or

very helpful, compared with 80% of siblings under

18 Participants felt safe to share thoughts and feelings with leaders. Participant experiences were validated through connecting with others |

| Hamblen et al.24 | USA | The InCourage programme was a mental health initiative setup

16 months after Hurricane Katrina by the Baton Rouge Crisis

Intervention Centre to support local people experiencing

PTSD symptoms The programme provided ten cognitive behavioural therapy post-disaster sessions delivered by trained therapists to individuals referred to the programme following screening |

Quasi-experimental time-series design | To describe the effects of a cognitive behavioural therapy post-disaster (CBT-PD) intervention to assess cognitive, emotional and behavioural reactions in individuals affected by Hurricane Katrina | 93 participants exposed to Hurricane Katrina completed the

programme 88 provided completed data on four repeated assessments (referral, pre-treatment, intermediate and post-treatment.) 66 participated in 5 month post-treatment follow-up A family member was missing or dead in 35% of cases, a friend was missing or dead in 55% of the cases There was no control group |

Individual change in PTSD across time points assessed using the 12-item short PTSD rating interview-expanded (SPRINT-E) | The CBT-PD reduced symptom distress in individuals

presenting with moderate and severe distress levels at

referral. A very high intervention fidelity was reported

across all sessions. Key results: 1. Reduction of severe distress symptoms from 61% at pre-treatment to 14% at post-treatment 2. Treatment appeared to work equally for participants with severe and moderate levels of stress 3. Reduction in distress was maintained 5-month post-treatment 4. The main mechanism for change related to the components of psycho-education and for breathing retraining and behavioural activation instead of cognitive restructuring as initially hypothesised. |

PTSD: post-traumatic stress disorder; GP: general practitioner; CCP: centre for crisis psychology; CBT-PD: cognitive behavioural therapy post-disaster; SPRINT-E: short PTSD rating interview expanded.

Results

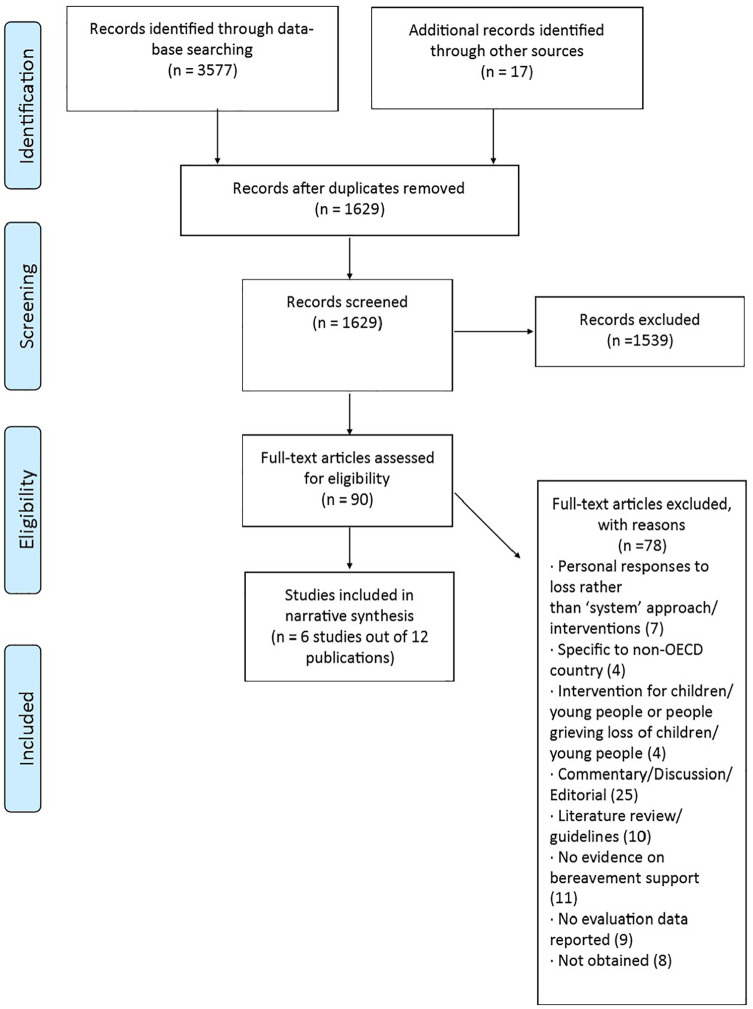

The searches generated 700 citations after removing duplicates and irrelevant records. Figure 1 represents records screened and included at the different stages of the review (Figure 1). Six studies (12 papers) were included.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram.

Types of mass bereavement interventions and support programmes

The six included studies reported interventions and support programmes initiated in response to human-made and natural disasters (Table 2). These included the Project Liberty Counselling services set up following the 11 September 2001 terror attacks in the USA,14–20 a state-led support programme following the July 2011 terror attacks in Norway,21,22 a collective assistance intervention following a Norwegian Maritime disaster in 1999,23 the InCourage mental health programme following Hurricane Katrina in the USA24 and the Ersta support programme for Swedish survivors of the South-East Asia Tsunami of 2004.25 While some of these interventions were exclusively targeted at bereaved family members and loved ones,21–23 others also provided support to non-bereaved victims of the respective disasters, who were experiencing other types of trauma.14–20,24,25 Where interventions addressed survivorship outcomes such as PTSD as well as bereavement, our analysis focused on the bereavement component.

Most of the interventions and programmes involved national or state-level coordination of support by multiple statutory and voluntary organisations, commonly in community settings.15,21,25 Across all programmes, psychologists, psychiatrists, therapists and social workers delivered the support; in the Project Liberty and Ersta programmes, community and faith-based agencies and workers were also involved.15,25 Programmes typically offered a mix of individual and group-based counselling and support sessions.14–17,21,22,25 Some included weekend family gatherings,22–25 specialist mental health provision for high-risk cases,14,16,21,24 open access public education and information provision15,25 and memorials and rituals.25 All incorporated elements of psycho-educational approaches.14,15,22–25

Screening and identification of individuals requiring more intensive, specialist support was a common feature across the services.14,17,21–24 In the Norwegian response to the 2011 terror attacks and Project Liberty counselling services, individuals identified as high risk were referred to local mental health services.17,21 In Project Liberty, bereaved individuals receiving counselling from July 2003 onwards were screened for complicated grief symptoms and, if indicated, provided with enhanced therapy services by specially trained, licenced mental health professionals. Sixteen months following Hurricane Katrina, the InCourage programme advertised free treatment for local people experiencing ‘stress or anxiety’ as a result of Hurricane Katrina. People who contacted the programme were screened for intense distress reactions using the short PTSD rating interview expanded (Sprint-E) tool and those that met the criteria were referred to a local therapist.24

Two of these services provided specialist cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) interventions. The InCourage programme involved ten CBT sessions which focused on identifying grief, coping with bereavement and distress and challenging disaster maladaptive beliefs. There were four core components: psycho-education, breathing retraining, behavioural activation and cognitive restructuring.24 In Project Liberty, the CBT component included techniques for recognising post-disaster distress; developing skills to cope with anxiety, depression and other symptoms; and cognitive reframing. It also provided information about natural grieving processes and traumatic grief symptoms and included strategies for dealing with loss and reengaging in satisfying life activities.14

With the exception of the CBT interventions, which were introduced 16 months24 and 21 months post disaster,14 most interventions were initiated in the immediate aftermath, with support providers continuing to offer support for between 12 and 32 months after the event.16,21,23,25

Study characteristics and methodological quality

Of the 12 study reports published, two described longitudinal outcome evaluations14,24 and one reported qualitative and quantitative results of a national survey of the affected population.21 The remaining nine described retrospective evaluations involving service user questionnaires19,20,22,23 reflective group discussions22,25 and service data and project records.15–18,25 The absence of comparison groups, use of convenience sampling, retrospective study designs and lack of methodological detail limit the quality and strength of the evidence from all studies. Taking into account these limitations, there are nonetheless important lessons regarding responses to mass bereavement with relevance to the COVID-19 context.

Evidence on the impacts of interventions

Only the two studies that reported on specialist interventions for high-risk groups were longitudinal outcome evaluations and neither used longitudinal comparison groups.14,24 In the evaluation of the Project Liberty enhanced service, initial comparisons were made between a subset of enhanced (n = 93) and standard crisis counselling recipients (n = 153), with the enhanced group reporting significantly more symptoms of depression, grief, traumatic stress and interference in five areas of daily functioning. At follow-up (enhanced participants only, n = 76), enhanced service recipients reported significant improvement in three of five functioning domains, significantly fewer symptoms of depression and grief and slightly less traumatic stress.14 In the InCourage CBT post-disaster intervention, a significant reduction in severe distress symptoms was found post-treatment (n = 88). The reduction in distress was maintained at 5 months post-treatment and the treatment worked equally for participants with severe and moderate levels of stress.24

In the remaining studies, participant views were mostly collected through retrospective feedback questionnaires 19,21–23 and reflective group discussion.22,25 Satisfaction with the different services was generally high. In the study of bereaved families of Norwegian terror attack victims, 95% (n = 98) of all survey participants reported to have received support; 73% were highly or fairly satisfied with the help received from professionals, although just under a quarter described aspects of their contact with professionals as a strain.21 User satisfaction with the family support weekends implemented following this attack was high for 90% of adult participants22 (n = 136–157) and for 96% of participants who took part in similar weekends following a Norwegian maritime disaster in 199923 (n value is not mentioned).

Qualitative feedback on the weekend gatherings22,25 and the long-term support groups for tsunami survivor families25 also demonstrated specific benefits of these group-based interventions. These included improved understanding and validation of their experiences, feelings of connectedness and enabling participants to feel hopeful for the future.22,25

Service user satisfaction with Project Liberty counselling services was evaluated with a subgroup of clients (n = 607, 38% of whom were bereaved), at least 89% of whom rated the service as good or excellent in the domains of daily responsibilities, relationships, physical health and community involvement.19

Common features of valued services

Although the nature of the events causing mass bereavement differed across studies, with variations in the bereavement service models described, there were striking consistencies in specific domains of service delivery deemed to be of value. These included a proactive outreach approach to service access, event-specific professional competencies beyond generic bereavement skills, an emphasis on psycho-educational content and centrally organised but locally delivered interventions.

A proactive bereavement support model

A key finding is the need for a proactive service approach in accessing those in need. The Project Liberty response to the New York 9/11 terrorist attack, the Swedish response to the 2004 tsunami, and the Norwegian response to the 2011 Utoya terrorist attack all emphasise the importance of proactive outreach rather than relying on self-referral. Project Liberty used a high profile advertising campaign to encourage service use and local community networks to consolidate early access.15,18 Over 753,000 counselling and education sessions were provided over 2 years with 95% of counselling sessions classed as individual. Those who were bereaved represented a significant proportion of early access users, with bereavement support needs tailing off by the month of five.16 In contrast, those with PTSD had different needs, with later onset of access but for longer duration.16 The evaluation also confirmed the success of accessing users who were representative of the socio-demographic profile of the affected localities across the wider metropolitan region, with high uptake rates among black and minority ethnic groups.14

In Sweden, the post-tsunami Ersta programme described a range of proactive approaches from advertising to word-of-mouth networks – identifying particular unmet need for those in rural areas and successfully contacting families in those communities to offer support.25 Qualitative data from bereaved service users following the Utoya attack in Norway underpinned the rationale for proactive service approaches. When asked to advise professionals on future service delivery, bereaved respondents emphasised both the positive impact of being directly contacted by support providers and the negative impact of not receiving direct approaches:

after a message such as we received, we are destroyed by grief, and time will pass before we realize that we need help21

They also called for multiple offers of support to those who initially decline intervention:

don’t expect that those who are in a completely absurd situation will make contact by themselves.21

Crisis-specific competencies

The skills and competencies of professionals were also considered across intervention models. In addition to generic bereavement competencies, essential staff preparedness included understanding the unique bereavement challenges of the mass event, its impact on usual death rituals and the community and the effects of mass media coverage.19,21–23 These additional competencies (or lack of) had significant impact on the perceived effectiveness of support following the 9/11 and Utoya attacks. Information provided by Project Liberty counsellors about reactions people frequently have after a disaster was rated good or excellent by 95% of survey respondents (n = 524).19 Conversely, qualitative feedback provided by families of victims of the Utoya terror attacks highlighted distress where counsellors were perceived to lack competencies regarding the context.21 The importance of cultural knowledge, sensitivity and multi-lingual support was also highlighted.19,23

The wider impact of mass events on social roles must also be considered, particularly in relation to isolation and job loss. A survey of Project Liberty clients suggested that those who became unemployed as a result of the 9/11 attack were 50% less likely to regain usual levels of functioning in domestic and community activities.20 At least 55% of those seeking support after Hurricane Katrina had lost immediate family or friends, and more than half had lost their jobs.24

Psycho-educational content and peer support

Psycho-educational approaches were central to many of the interventions. These focused on understanding responses to loss, normalising grief, improving family and social connectedness, and promoting individual coping skills. The Project Liberty model of crisis support assumed that for the majority, stress (including bereavement) reactions are normal and likely to be relatively short term. The focus was on supporting clients to identify and understand their response to loss, reviewing their options, addressing their emotional support and connecting them with other individuals and agencies who might assist them.15 Service satisfaction surveys of the subset of Project Liberty users (n = 607) showed 93% rated their crisis support good or excellent in terms of helping them to regain function in daily responsibilities and personal relationships.19 Education strategies for dealing with loss, followed by gradual re-engagement with satisfying life activities, was also core to the enhanced project Liberty intervention for high-risk service users, the benefits of which are reported above.14 The evaluation of the CBT post-disaster intervention after Hurricane Katrina (n = 88) also found that the greatest improvements occurred with psycho-education and coping skills rather than with cognitive restructuring.24

Three papers22,23,25 highlighted the perceived value of group interventions for psycho-educational support, using structured weekend gatherings22,23,25 and long-term support groups.25 Despite the differences in the nature of the disasters, the weekend gatherings used very similar formats: a combination of formal talks and educational seminars followed by less formal group conversations, in what Dyregrov describes as a ‘collective assistance approach’.23 While the key benefits of these types of group-based support are reported above, particular features that were valued included the use of group rituals to recognise the enormity of the loss, remember loved ones and act as a foundation for reclaiming life.22,25 Participants also described reassurance and a sense of understanding and security in ‘being with others who had experienced the same’, which helped normalise their experiences and recovery when existing social networks were less supportive:21,22,25

It is intense to go so deeply into one’s feelings and experiences related to what happened on July 22, but so good to experience that I am taken seriously and that I can be with others who lost their loved ones in the same manner as me. I really experience that these gatherings help me in my grief process. I feel stronger and better prepared to handle the future (weekend participant).22

Key successful elements for the bereaved in these settings were staff preparedness and a structured and predictable agenda.

Structured, centralised service with local delivery

All programmes described a standardised and centralised approach to the development of interventions and staff training, with local delivery of support by a range of health, social care and community workers/volunteers, from statutory, voluntary and faith-based organisations.14,21,24,25 In Project Liberty, the use of informal community settings for 73% of support encounters, rather than organisations’ buildings, was deemed important for access.15 The importance of enabling a broad spectrum of types of support was indicated in the New York, Swedish and Norway studies. Support which was adaptive to individual needs was highlighted, with younger siblings of the Norwegian terror attacks identifying the need for school support and adapted educational goals.21 In the Ersta programme for Swedish Tsunami survivors, signs of resilience were also identified in survivor families who did not take up professional support but organised their own websites and collective activities, suggesting that interventional programmes should also recognise and encourage informal support and citizen-led coping responses.25

Discussion

Main findings

The global impact of COVID-19 on health and social care systems is unprecedented, with the impact on bereavement and mental health support yet to be quantified. Although there is published evidence on personal grief responses to a pandemic,9 there has not yet been consideration of what constitutes an effective systems’ approach to bereavement service delivery in this context. This paper has synthesised the evidence for service delivery in the wider context of mass bereavement following human-made and natural disasters. Although the nature of those events differ in causation and character to the current pandemic, several important features resonate: sudden and high-volume loss of life, lack of access to loved ones following death and disturbance of usual funeral rituals (e.g. due to missing/delayed return of bodies, local infrastructural factors), job loss and societal disruption and mass media coverage of the events and their aftermath. None of the studies provide robust, high-grade evidence of programmes’ effectiveness in improving health status. However, through service evaluation and qualitative enquiry they do provide evidence of impact on service users, of specific service domains considered of value and of lessons learned. Several common themes emerge across these divergent events and intervention types. Whereas some aspects of these approaches and findings align with public health models of bereavement care, several disaster-specific features are also identified, indicating important considerations for bereavement service responses to COVID-19.

Strengths and weaknesses

The limitations of this review are acknowledged. The included studies relate to natural and human-made disasters rather than epidemic/pandemic events and are few in number. While similarities with these types of bereavement events are noted above, there are also differences to consider. For example, terror-related events may be associated with aspects of bereavement specific to violent death and like the other disasters considered here were discrete, isolated events. By contrast, the ongoing global nature of the COVID-19 pandemic brings continuing and unique sets of risks for the bereaved, with the lingering threat of further loss and limited access to social networks and support. Some of the services reviewed here also addressed a broad range of post-disaster outcomes including PTSD and anxiety/depression among non-bereaved clients, and it was not always possible to distinguish results relating to bereaved groups. Although some studies report quasi-experimental approaches and the use of qualitative data, there was significant use of user satisfaction questionnaires and retrospective study designs. There is therefore potential inherent bias in terms of convenience sampling, before and after designs and retrospective data analysis, as acknowledged within individual studies. Despite these methodological limitations and variation between the different types of bereavement events, consistent themes were evident in terms of key service domains and the types of intervention valued by service users. Many of the event-specific issues of apparent importance to the bereaved appear pertinent also to the COVID-19 context.

What this review adds

Despite the exceptional nature of the bereavements considered in this review, there were some clear similarities in the approaches used and benefits reported for disaster-related and regular bereavement support. The value of psycho-educational approaches which underpin understanding of normal responses to loss, development of coping skills and early reconnection to pre-existing support networks was repeatedly identified.14,15,21–25 Likewise, accessing peer support from those with shared experiences was also found to be helpful, in terms of understanding grief responses21–23,25 and developing supportive relationships.25 This is consistent with the evidence for bereavement support relating to deaths from advanced disease26,27 and Dual Process Models of grief adaptation, which describe a process of oscillation between loss-orientated and restoration-orientated coping.28 It is also consistent with other disaster-specific evidence on the importance of social support and connectedness for the psycho-social recovery and mental health of trauma victims29,30 and international guidelines31 which recommend the promotion of connectedness and self/community efficacy when responding to collective trauma events. The value of specialist disaster-specific CBT combined with psycho-education, introduced between 1 and 2 years post-disaster for high-risk individuals, was also indicated and has been recognised in recent expert consensus on disaster behavioural interventions.32 While lack of comparison groups undermines the strength of this evidence, this is consistent with wider literature indicating the effectiveness of targeted specialist support for high-risk groups.33–35

These review findings therefore support resilience frameworks32,36–38 and multi-tiered NICE and public health models of bereavement care.39,40 These models recommend specialist counselling and mental health support for those identified as at high risk of PGD, and counselling and other forms of reflective support for those with moderate needs, including peer support groups. Provision of information on grief and available support services, coupled with support from existing social networks, is recommended for all groups of bereaved people. In line with these approaches and disaster-specific recommendations,31,32 core components of a COVID-19 bereavement response should emphasise psycho-educational approaches, screening for risk of PGD and other mental health disorders (e.g. PTSD) and provision of specialist support for those with high level needs. Where there is clustering of similar experiences (e.g. by care settings or demographic groups), carefully planned and structured group support should also be considered. While the evidence considered in this review was based on forms of in-person support, current COVID-19 infection control requirements means that alternative, remote modes of delivery such as telephone/virtual counselling, virtual groups, online forums or even outdoor activities, are required. Due to the dearth of evidence on these methods in disaster and regular bereavement contexts,26 it is important that rapid evidence is sought on their acceptability, feasibility and effectiveness.

This review has also identified service features specific to disaster-related bereavement support that have relevance to the COVID-19 context. First is the need for a highly co-ordinated, proactive and multi-pronged approach, which reaches out with support for bereaved populations, but also avoids promoting formal intervention for those displaying resilience.32 International guidelines on collective trauma response similarly emphasise the need to provide practical information and advice through multiple relevant channels early on in the crisis, moving to an open, centralised communication channel in the longer-term aftermath.31 Multi-media and social network campaigns appeared effective in facilitating early access for those bereaved, for targeting a socio-demographic user base broadly representative of their localities,15,18 and in reaching those in isolated or rural settings.25 An integrated regional approach to both advertise COVID-19 support services and contact those bereaved should be considered early in the funding and coordination phase of a bereavement response to the current crisis.

Central coordination of intervention development and training, with local delivery by multiple organisations, has been consistently applied across the disaster responses described and also emphasised in recent consensus based recommendations and guidelines.31,32 In the context of broader stress responses to a disaster, bereavement support needs appear to present earlier (than, for example, PTSD);14 ease of access is therefore crucial, preferably in community rather than organisational settings.15,21,25 Those planning and implementing COVID-19 bereavement responses should also consider the crisis-specific competencies of core staff. Above and beyond generic bereavement skillsets, support workers need to understand the potential impact of lack of access to loved ones pre- and post-death, altered funeral rituals41 and the pervasive media coverage of the pandemic on experiences of grief, so that bereaved service users feel services are both competent and accessible. The wider impact of COVID-19 on other life roles such as social functioning and job loss should also be factored into assessments, with pandemic-driven social isolation and unemployment potential risk factors for complicated grief.14,20,24 The importance of culturally sensitive approaches were also identified in this and other reviews and guidelines,31,32 with recommendations that information is sought on the specific needs, barriers to care and concepts of recovery for specific minority groups.42 Given the over-representation of black and minority ethnic groups in COVID-19 death rates in the UK,43 these considerations appear salient.

Implications for further research

This review highlights what is known regarding the provision of post-disaster bereavement services, and reflects an evolution of delivery models in response to earlier evaluations.44 However, we also found limitations in the approaches to evidence gathering. More robust primary studies which map the grief experiences of people bereaved during pandemics, and the ways in which systems and bereavement services respond to meet their needs are urgently needed. There is currently no evidence of this kind relating to Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) economies. Our findings highlight the key role of research and evaluation in further refining intervention delivery and mandate for the integration of evaluative research in the planning of bereavement responses to COVID-19.

Conclusion

The conclusions that can be drawn from this review in relation to COVID-19 are limited by the quantity, quality and applicability of the evidence. There are, however, some consistent messages that can be identified for bereavement support provision during and beyond the pandemic and for system responses to mass bereavement events more broadly. These include

Adoption of a proactive service model to seek out those in need

Central coordination of a consistent offer of support with delivery by local organisations

Crisis-specific core competencies for those delivering counselling interventions

An emphasis on structured psycho-education to enable loss and restoration-focused coping and use of support from existing social networks

The use of group-based support for facilitating connectedness and shared understandings

The need for formal risk assessment leading to specialist mental health provision for individuals at high risk of PGD and other mental health disorders

Integration of prospective evaluation alongside service delivery with real-time feedback used to inform practice.

In parallel, service providers and policy makers should consider

Mechanisms for advertising services widely to ensure access to bereavement support for all who need it

Enhancing the role and capacity of existing providers of bereavement support such as hospices and community palliative care providers, as well as other types of community organisations and networks connected with Compassionate Communities approaches to end of life care and bereavement45

Provision of training in core competencies specific to COVID-19 for those delivering support and the rapid sharing of emergent best practice and learning by leading UK bereavement and palliative care providers

Viable options for delivering group-based and other forms of support in the context of social distancing restrictions

How best to integrate bereavement support in wider population-level support for the social and psychological consequences of COVID-19.

For the research community, there is also a clear need for high quality primary studies relating to grief experiences and bereavement support interventions during and after pandemics. Such studies should aim for rapid translation of evidence into practice to ensure service improvement in the current crisis, as well as much-needed evidence to guide future disaster-response efforts.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Medline_search_strategy for What elements of a systems’ approach to bereavement are most effective in times of mass bereavement? A narrative systematic review with lessons for COVID-19 by Emily Harrop, Mala Mann, Lenira Semedo, Davina Chao, Lucy E Selman and Anthony Byrne in Palliative Medicine

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Tomas Allen, Librarian at the World Health Organisation (WHO), who provided information on search terms relating to pandemics.

Footnotes

Author contributions: A.B., E.H. and M.M. conceived the study; A.B., E.H., M.M. and L.S. designed the study protocol. M.M. designed the search strategy (in consultation with other review authors) and performed the database searches. A.B., E.H., L.E.S., M.M., L.S. and D.C. were all involved in study selection. E.H., L.E.S., M.M., L.S. and D.C. extracted data and carried out quality assessment. D.C. was supervised by L.S. All authors contributed to drafting the paper, revised the paper and approved the final version. A.B. is the guarantor for the paper.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: No ethical approvals were required as this is a systematic review.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: A.B., E.H., L.E.S. and M.M. posts are supported by Marie Curie core grant funding (Grant No. MCCC-FCO-11-C). M.M. is also supported by Wales Cancer Research Centre, funded by Health and Care Research Wales (Grant No. WCRC514031). L.S. is funded by a Career Development Fellowship from the National Institute for Health Research.

ORCID iDs: Emily Harrop  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2820-0023

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2820-0023

Mala Mann  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2554-9265

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2554-9265

Lucy E Selman  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5747-2699

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5747-2699

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Koffman J, Gross J, Etkind SN, et al. Clinical uncertainty and Covid-19: embrace the questions and find solutions. Palliat Med 2020; 34(7): 829–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Koffman J, Gross J, Etkind SN, et al. Uncertainty and COVID-19: how are we to respond. J R Soc Med 2020; 113(6): 211–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shear MK, Ghesquiere A, Glickman K. Bereavement and complicated grief. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2013; 15: 406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Selman LE, Chao D, Sowden R, et al. Bereavement support on the frontline of COVID-19: recommendations for hospital clinicians. J Pain Symp Manage. Epub ahead of print 4 May 2020. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kentish-Barnes N, Chaize M, Seegers V, et al. Complicated grief after death of a relative in the intensive care unit. Eur Respir J 2015; 45(5): 1341–1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kun P, Han S, Chen X, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder: a cross-sectional study among survivors of the Wenchuan 2008 earthquake in China. Depr Anxiety 2009; 26(12): 1134–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Morris SE, Moment A, Thomas JD. Caring for bereaved family members during the COVID-19 pandemic: before and after the death of a patient. J Pain Symp Manag. Epub ahead for print 7 May 2020. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wallace CL, Wladkowski SP, Gibson A, et al. Grief during the COVID-19 pandemic: considerations for palliative care providers. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020; 60(1): e70–e76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mayland CR, Harding AJE, Preston N, et al. Supporting adults bereaved through COVID-19: a rapid review of the impact of previous pandemics on grief and bereavement. J Pain Symptom Manage. Epub ahead of print 15 May 2020. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mann M, Woodward A, Nelson A, et al. Palliative care evidence review service (PaCERS): a knowledge transfer partnership. Health Res Policy Syst 2019; 17: 100–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009; 6: e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Specialist Unit for Review Evidence (SURE) 2018, https://www.cardiff.ac.uk/specialist-unit-for-review-evidence/resources/critical-appraisal-checklists (accessed 3 June 2020).

- 13. Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: a product from the ESRC methods programme, 2006, http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.178.3100&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- 14. Donahue SA, Jackson CT, Shear KM, et al. Outcomes of enhanced counseling services provided to adults through project liberty. Psychiatr Serv 2006; 57(9): 1298–1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Donahue SA, Covell NH, Foster MJ, et al. Demographic characteristics of individuals who received Project Liberty crisis counseling services. Psychiatr Serv 2006; 57(9): 1261–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Covell NH, Donahue SA, Allen G, et al. Use of Project Liberty counseling services over time by individuals in various risk categories. Psychiatr Serv 2006; 57(9): 1268–1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Covell NH, Essock SM, Felton CJ, et al. Characteristics of Project Liberty clients that predicted referrals to intensive mental health services. Psychiatr Serv 2006; 57(9): 1313–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Frank RG, Pindyck T, Donahue SA, et al. Impact of a media campaign for disaster mental health counseling in post-September 11 New York. Psychiatr Serv 2006; 57(9): 1304–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jackson CT, Allen G, Essock SM, et al. Clients’ satisfaction with Project Liberty counseling services. Psychiatr Serv 2006; 57(9): 1316–1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jackson CT, Covell NH, Shear KM, et al. The road back: predictors of regaining preattack functioning among Project Liberty clients. Psychiatr Serv 2006; 57: 1283–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dyregrov K, Kristensen P, Johnsen I, et al. The psychosocial follow-up after the terror of July 22nd 2011 as experienced by the bereaved. Scand Psychol 2015; 2, https://psykologisk.no/sp/2015/02/e1/ [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dyregrov A. Weekend gatherings for bereaved family members after the terror killings in Norway in 2011. Bereavement Care 2016; 35: 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dyregrov A, Straume M, Sari S. Long-term collective assistance for the bereaved following a disaster: a Scandinavian approach. Counsel Psychother Res 2009; 9: 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hamblen JL, Norris FH, Pietruszkiewicz S, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for postdisaster distress: a community based treatment program for survivors of Hurricane Katrina. Adm Policy Ment Health 2009; 36(3): 206–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Broms C. The tsunami 26 December 2004: experiences from one place of recovery, Stockholm, Sweden. Prim Health Care Res Dev 2012; 13(4): 308–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Harrop E, Morgan F, Longo M, et al. The impacts and effectiveness of support for people bereaved through advanced illness: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. Palliat Med 2020; 34(7): 871–888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Harrop E, Scott H, Sivell S, et al. Coping and wellbeing in bereavement: two core outcomes for evaluating bereavement support in palliative care. BMC Palliative Care 2020; 19: 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stroebe M, Schut H. The dual process model of coping with bereavement: rationale and description. Death Stud 1999; 23(3): 197–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hobfoll S, Watson P, Bell C, et al. Five essential elements of immediate and mid-term mass trauma intervention: empirical evidence. Psychiatry 2007; 70(4): 283–315; discussion 316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Norris FH, Stevens SP. Community resilience and the principles of mass trauma intervention. Psychiatry 2007; 70: 320–328. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Brady K, Randrianarisoa A, Richardson J. Best practice guidelines: supporting communities before, during and after collective trauma events, 2018, https://www.redcross.org.au/getmedia/03e7abed-2be0-43b7-95d7-0e8f3d5206bd/ARC-CTE-Guidelines.pdf.aspx

- 32. Watson P, Brymer M, Bonanno GA. Postdisaster psychological intervention since 9/11. Am Psychol 2011; 66(6): 482–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wittouck C, Van Autreve S, De Jaegere E, et al. The prevention and treatment of complicated grief: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2011; 31(1): 69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Johannsen M, Damholdt MF, Zachariae R, et al. Psychological interventions for grief in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Affect Disord 2019; 253: 69–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Neimeyer RA, Currier JM. Grief therapy: evidence of efficacy and emerging directions. Curr Direct Psychol Sci 2009; 18: 352–356. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bonanno G, Westphal M, Mancini A. Resilience to loss and potential trauma. Ann Rev Clin Psychol 2010; 7: 511–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Machin L. Exploring a framework for understanding the range of response to loss: a study of clients receiving bereavement counselling. PhD Thesis, University of Keele, Keele, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rumbold B, Aoun S. An assets-based approach to bereavement care. Bereav Care 2015; 34: 99–102. [Google Scholar]

- 39. National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Guidance on cancer services: improving supportive and palliative care for adults with cancer (The manual). London: NICE, 2004, https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/csg4 (accessed 3 June 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 40. Aoun SM, Breen LJ, O’Connor M, et al. A public health approach to bereavement support services in palliative care. Aust N Z J Public Health 2012; 36(1): 14–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Burrell A, Selman LE. How do funeral practices impact bereaved relatives mental health, grief and bereavement? A mixed methods review with implications for COVID-19. Omega. Epub ahead of print 10 July 2020. DOI: 10.1177/0030222820941296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Norris F, Alegria M. Promoting disaster recovery in ethnic-minority individuals and communities. In: Marsella AJ, Johnson JL, Watson P, et al. (eds) Ethnocultural perspectives on disaster and trauma. New York: Springer, 2008, pp. 15–35. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pareek M, Bangash MN, Pareek N, et al. Ethnicity and COVID-19: an urgent public health research priority. Lancet 2020; 395: 1421–1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Donahue SA, Lanzara CB, Felton CJ, et al. Project Liberty: New York’s crisis counseling program created in the aftermath of September 11, 2001. Psychiatr Serv 2006; 57(9): 1253–1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Compassionate Communities UK, https://www.compassionate-communitiesuk.co.uk/ (2020, accessed 8 July 2020).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, Medline_search_strategy for What elements of a systems’ approach to bereavement are most effective in times of mass bereavement? A narrative systematic review with lessons for COVID-19 by Emily Harrop, Mala Mann, Lenira Semedo, Davina Chao, Lucy E Selman and Anthony Byrne in Palliative Medicine