Abstract

Star-shaped three-dimensional (3D) twisted configured acceptors are a type of nonfullerene acceptors (NFAs) which are getting considerable attention of chemists and physicists on account of their promising photovoltaic properties and manifestly promoted the rapid progress of organic solar cells (OSCs). This report describes the peripheral substitution of the recently reported highly efficient 3D star-shaped acceptor compound, STIC, containing a 2-(3-oxo-2,3-dihydroinden-1-ylidene)malononitrile (IC) end-capped group and a subphthalocyanine (SubPc) core unit. The 3D star-shaped SubPc-based NFA compound STIC is peripherally substituted with well-known end-capped groups, and six new molecules (S1–S6) are quantum chemically designed and explored using density functional theory (DFT) and time-dependent DFT (TDDFT). Density of states (DOS) analysis, frontier molecular orbital (FMO) analysis, reorganization energies of electrons and holes, open-circuit voltage, transition density matrix (TDM) surface, photophysical characteristics, and charge-transfer analysis of selected molecules (S1–S6) are evaluated with the synthesized reference STIC. The designed molecules are found in the ambience of 2.52–2.27 eV with a reduction in energy gap of up to 0.19 eV compared to R values. The designed molecules S3–S6 showed a red shift in the absorption spectrum in the visible region and broader shift in the range of 605.21–669.38 nm (gas) and 624.34–698.77 (chloroform) than the R phase values of 596.73 nm (gas) and 616.92 nm (chloroform). The open-circuit voltages are found with the values larger than R values in S3–S6 (1.71–1.90 V) and comparable to R in the S1 and S2 molecules. Among all investigated molecules, S5 due to the combination of extended conjugation and electron-withdrawing capability of end-capped acceptor moiety A5 is proven as the best candidate owing to promising photovoltaic properties including the lowest band gap (2.27 eV), smallest λe = 0.00232 eV and λh = 0.00483 eV, highest λmax values of 669.38 nm (in gas) and 698.77 nm (in chloroform), and highest Voc = 1.90 V with respect to HOMOPTB7-Th–LUMOacceptor. Our results suggest that the selected molecules are fine acceptor materials and can be used as electron and/or hole transport materials with excellent photovoltaic properties for OSCs.

Introduction

Organic solar cells (OSCs) are getting remarkable attention and immense advancement since past 5 years because of molecular design, especially for nonfullerene acceptors (NFAs), polymer donors, and interlayer materials.1−3 Acceptor molecules containing end-capped groups fused with ladder-type electron-donating cores with a linear acceptor–donor–acceptor (A–D–A) configuration are considered as a representative type of NFAs.4−6 Indacenodithienothiophene (IDTT) and IDT are the most admired central cores owing to their easy modifications, thermal stabilities, strong electron-donating abilities, and coplanar and rigid structures.7−9 The 2-(3-oxo-2,3-dihydroinden-1-ylidene)malononitrile (IC) end-cap group along with its derivatives is largely utilized among a number of end groups on account of their large electron affinities and planar structures.10 Three-dimensional (3D) star-shaped twisted configured acceptors are another type of NFAs.11,12 In star-shaped molecules (SSMs), a central core is connected by several (three or more) linear chains. Physicists and chemists are getting attracted toward SSMs on account of their distinctly different properties in contrast to their linear analogues. The excessive aggregation in these star-shaped NFAs is prevented by the nonplanar structure of the acceptor which facilitates the isotropic electron transport.13 The construction of a distorted structure containing numerous end-capped electron-withdrawing groups and electron-donating spatial cores is the most successful and effective strategy to design high-performance 3D star-shaped acceptors.14 The electron-donating nature of truxene, 4,4′-spirobi-(cyclopenta(2,1-b;3,4-b′)dithiophene) (SCPDT), and spirobifluorene (SF) contributes to intramolecular charge transfer (CT) among spatial cores and end-capped electron-withdrawing units.15,16 Diketopyrrolopyrroles (DPPs) and perylene diimides (PDIs) are frequently applied end-cap groups in 3D star-shaped acceptors owing to the high electron mobility, strong absorption, and >5% power conversion efficiency (PCE) of either DPP- or PDI-based 3D star-shaped acceptors.15,17 A PCE of above 10% is achieved from star-shaped 3D acceptors containing rhodanine and benzothiadiazole (BT) as electron-withdrawing units.18 Recently, a report on the synthesis of 3D star-shaped acceptor molecules containing IC as the end group and SF as the core is presented by Chang et al., which indicated that derivatives of IC are promising end-capped moieties for expansion of star-shaped 3D acceptors.19

Subphthalocyanine (SubPc) is a boron-central conjugated macrocycle with the intrinsic nonplanar cone-shaped structure and recognized as an exceptional building unit for devolving NFAs because of the high electron mobility, high absorption coefficient in the visible light region, and prevention of excessive intermolecular aggregation in films.20,21 Few recent reports on SubPc-based solution-processed bulk heterojunction (BHJ) OSCs are also available in the literature. A PCE of 2.9% was achieved in single-heterojunction (SHJ) OSCs with tetracene and SubPc demonstrated by Jones et al.22 In the report of Heremans , a PCE of 4.69% has been indicated by the SubPc-based bilayer solar cells. A noticeable PCE of 8.4% was attained in vacuum-deposited planar heterojunction (PHJ) OSCs using SubPc as the electron acceptor, which is a record efficiency for solar cells based on SubPc derivatives.23 Literature study reveals that introduction of peripheral substituents to SubPc molecules tuned the electronic properties, downshifted the LUMOs, and well matched these SubPc-based derivatives with common donor materials. Very recently, Hang et al. synthesized a 3D star-shaped SubPc-based NFA, namely, STIC, with a PCE of 4.69%, which is also among the highest PCE values for SubPc-based solution-processed BHJ OSCs.24 STIC is considered as an excellent OSC candidate, which is better than traditional SubPc-based NFAs because of the high extinction coefficients, narrower band gap, broader and strong absorption band in the visible region, stronger photoresponse, and improved OSC device efficiency. The STIC structure is composed of strong electron-withdrawing 2-(3-oxo-2,3-dihydroinden-1-ylidene)malononitrile (IC) end-capped groups and the SubPc core unit connected to thiophene bridges. The report by Hang et al. describes that peripheral substitution of SubPc is an efficient approach for designing SubPc-based NFAs. Therefore, the 3D star-shaped SubPc-based NFA STIC is peripherally substituted with diverse reported end-capped acceptor groups, and six new molecules (S1–S6) are designed. The density of states (DOS) analysis, frontier molecular orbital (FMO) analysis, reorganization energies of electrons and holes, open-circuit voltage, transition density matrix (TDM) surface, binding energy calculations, photophysical characteristics, and CT analysis of selected molecules (S1–S6) are evaluated with the synthesized reference STIC, and new NFAs with enhanced optoelectronic properties are suggested to exercise in solar cells.

Computational Procedure

The Gaussian 09 program package25 employing density functional theory (DFT) calculations was used for performing complete quantum chemical calculations of the present study. All input files were made using the GaussView 5.026 program. Two basis sets 6-31G(d,p) and 6-311G(d,p) in grouping with six functionals M06-2X,27 LC-BLYP,28 ωB97XD,29 MPW1PW91,30 CAM-B3LYP,31 and B3LYP,32 were exercised without symmetry restrictions in the gas phase for initial geometry optimization of the reference compound (R). Time-dependent DFT (TDDFT) calculations at the M06-2X, LC-BLYP, ωB97XD, MPW1PW91, CAM-B3LYP, and B3LYP levels of theory in conjunction with the 6-31G(d,p) and 6-311G(d,p) basis sets were performed in the gas and solvent phases for simulating the absorption spectrum (λmax) of R.33−45 The choice of the finest existing functional was made by comparing the TDDFT calculation-based λmax results of R with experimental data. From the investigated functionals, MPW1PW91/6-31G(d,p) functional results are found to be in good agreement with experimental reported results, which provide a strong clue to perform further calculations using this functional and basis set combination.38−42,46,47 After geometry optimization of the investigated molecules (R and S1–S6), vibrational analysis at the MPW1PW91/6-31G(d,p) functional was executed, which confirmed the lack of negative eigenvalues and the presence of optimized geometries in potential energy surfaces at the true minimum. The conductor-like polarizable continuum model (CPCM)48 and chloroform solvent at the TDDFT/MPW1PW91/6-31G(d,p) functional were employed to estimate the UV–vis spectra of S1–S6. The Swizard program49 was used for the measurement of the molar absorption coefficient (λmax) in the gaseous and solvent (chloroform) phases. The Origin 8.0 program was used to plot the results attained from Gaussian calculations. Different computations were executed using the same DFT/MPW1PW91/6-31G(d,p) functional for estimation of TDM surfaces, DOS, FMO analysis, open-circuit voltage (Voc), reorganization energies, CT analysis, and band gap of the studied (R and S1–S6) compounds. To check the contribution of each fragment in the absorption of radiation, the DOS of all molecules including the reference was also calculated and expressed using the PyMOlyze 2.050 program. The Multiwfn 3.7 program package51 was used for the TDM analysis that helped to understand the electronic excitation processes. Marcus theory52 played a vital role for CT analysis of each molecule, either intermolecular or intramolecular. For the analysis of electron mobility (λe) with respect to Marcus theory, the following eq 1 can be used for interpretation.

| 1 |

where E–0 is the energy of the neutral molecule calculated from the optimized geometry of the anion, E0 is the energy of the neutral molecule from the neutral optimized molecule, E– is the energy of the anion calculated from the optimized geometry of the anion, and E0– is the energy of the anion from the neutral molecule for all the molecules under consideration. Similarly, hole mobility is also responsible for CT interactions in OSCs, which can be calculated from the following equation

| 2 |

where E+0 is the energy of the neutral molecule calculated from the optimized geometry of the cation, while E0and E+ are the energy of cations calculated from the optimized geometry of the neutral and cation molecules, respectively.53

Results and Discussion

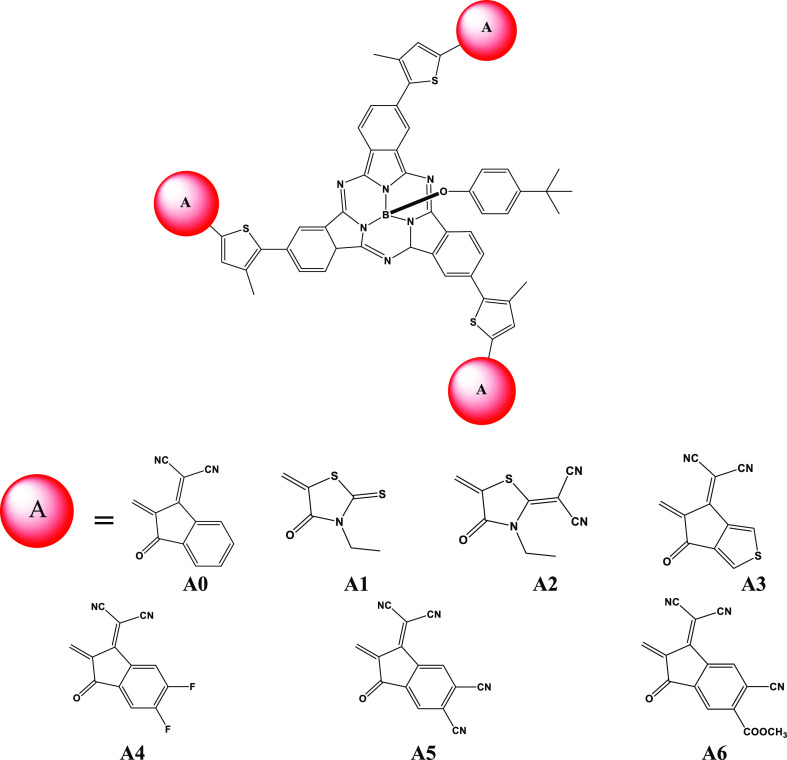

The present study spotlights the attempt to design and explore SubPc-based 3D star-shaped NFAs with enhanced optoelectronic properties for their use in solar cells. For systematic designing, the recently synthesized and reported highly efficient 3D star-shaped acceptor compound STIC24 is used. The structure of STIC is composed of strong electron-withdrawing 2-(3-oxo-2,3-dihydroinden-1-ylidene)malononitrile (IC) end-capped groups and the SubPc core unit connected to thiophene bridges. The report presented by Hang et al.24 describes that peripheral substitution of SubPc is a useful approach for designing SubPc-based acceptors. Thus, by taking the clue from the Hang et al. report, three arms of STIC containing the (Z)-2-(2-ethylidene-3-oxo-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-1-ylidene)malononitrile (A0) acceptor segment are peripherally substituted with six different reported end-capped acceptor moieties, namely, 3-ethyl-5-methylene-2-thioxothiazolidin-4-one (A1), 2-(3-ethyl-5-methylene-4-oxothiazolidin-2-ylidene)malononitrile (A2), 2-(5-methylene-6-oxo-5,6-dihydro-4H-cyclopenta-[c]thiophen-4-ylidene)malononitrile (A3), 2-(5,6-difluoro-2-methylene-3-oxo-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-1-ylidene)malononitrile (A4), 1-(dicyanomethylene)-2-methylene-3-oxo-2,3-dihydro-1H-indene-5,6-dicarbonitrile (A5), and methyl-6-cyano-1-(dicyanomethylene)-2-methylene-3-oxo-2,3-dihydro-1H-indene-5-carboxylate (A6), and six new 3D star-shaped SubPc-based NFA molecules (S1–S6) are designed for their potential photovoltaic and optoelectronic characteristics (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Sketch Map of SubPc-Based 3D NFA Structures.

Considering the computational cost, the selected molecules (S1–S6) were simplified by substituting long alkyl chains with methyl groups. Previous reports indicate that relative trends of the obtained results and essential characteristics of investigated molecules remain unaffected with these simplifications.54 The molecular structures of the SubPc-based selected molecules (R and S1–S6) are presented in Figure S1 (Supporting Information).

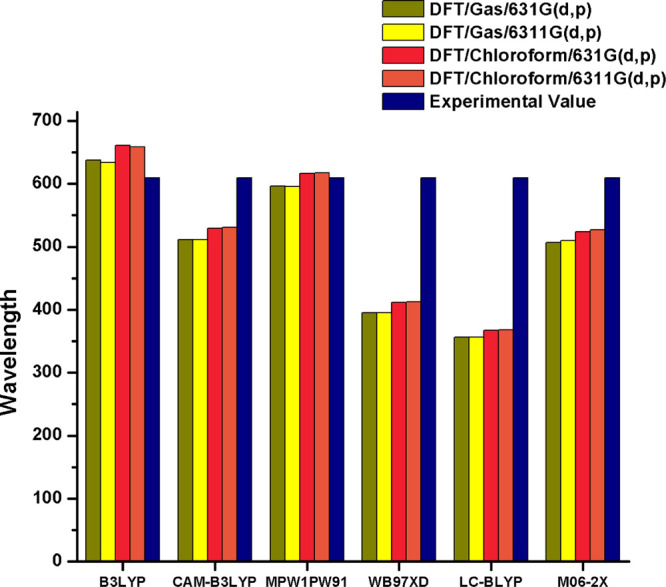

In the present quantum chemical investigation, different functionals M06-2X, LC-BLYP, ωB97XD, MPW1PW91, CAM-B3LYP, and B3LYP in conjunction with the 6-31G(d,p) and 6-311G(d,p) basis sets are tested for finding the best level of theory to estimate the optoelectronic and photovoltaic properties of the investigated molecules. For this, a bar chart is portrayed in Figure 1, in which the λmax values of R (in the gas and the chloroform solvent) obtained from the M06-2X, LC-BLYP, ωB97XD, MPW1PW91, CAM-B3LYP, and B3LYP functionals and the 6-31G(d,p) and 6-311G(d,p) basis sets are compared with the experimental reported λmax results of reference molecule R. The λmax values of R in the gas phase with the M06-2X, LC-BLYP, ωB97XD, MPW1PW91, CAM-B3LYP, and B3LYP functionals are computed as 506, 356, 395, 596, 511, and 637 nm with the 6-31G(d,p) basis set and 509, 356, 395, 595, 511, and 633 nm with the 6-311G(d,p) basis set, respectively. Alternatively, in the chloroform solvent, the λmax values of R are 523, 367, 411, 616, 529, and 660 nm and 527, 368, 412, 617, 530, and 658 nm with the 6-31G(d,p) and 6-311G(d,p) basis sets in combination with the M06-2X, LC-BLYP, ωB97XD, MPW1PW91, CAM-B3LYP, and B3LYP functionals, respectively. From the above data, it is evident that the MPW1PW91/6-31G(d,p) functional shows maximum agreement and minimum difference with the experimental reported value and also provides justification for its further use to perform auxiliary calculations of R and the selected (S1–S6) molecules.

Figure 1.

Simulated bar chart for reference R.

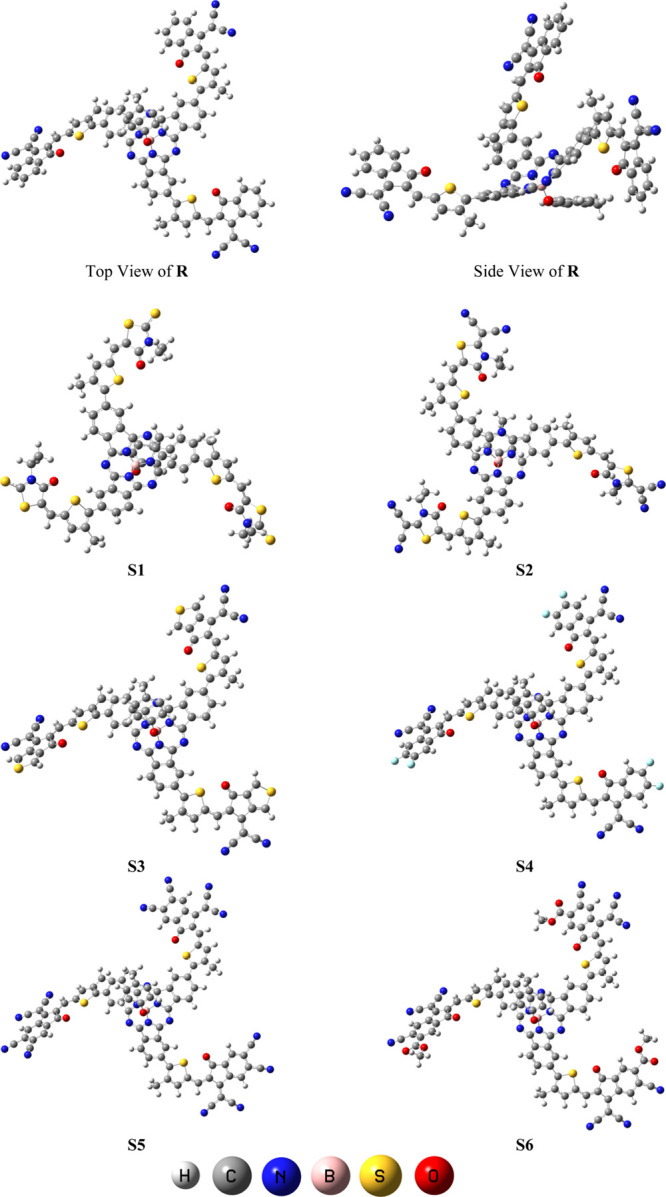

Using the MPW1PW91/6-31G(d,p) level of DFT, optimization analysis of the selected molecules (S1–S6) is performed and their optimized geometries are portrayed in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Optimized molecular geometries of the investigated molecules at the MPW1PW91/6-31G(d,p) functional.

FMO Analysis

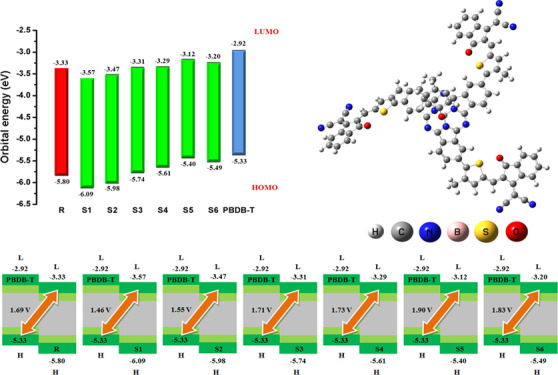

FMO analysis is recognized as a vital tool to evaluate the prospect of ICT characteristics among the investigated molecules.55−60 The FMOs are essential in providing the properties of solar cells having the ability to conduct charges and to facilitate the conduction of electric current.36 The energies for FMOs including the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) (EHOMO), lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) (ELUMO), and energy gap (ELUMO–EHOMO) values of all investigated molecules (R and S1–S6) are calculated at the DFT/MPW1PW91/6-31G(d,p) level of theory, and the results are listed in Table S1 (Supporting Information).

The energy gap (Eg) of R is observed as 2.46 eV, which is noted as a higher value of band gap than S3–S6 molecules and slightly smaller than that of S1 and S2 molecules. The highest value of energy gap of 2.52 eV among all investigated molecules (S1–S6 and R) is found in the S1 designed molecule. This value is comparable to that of reference molecule R, demonstrating the comparable effectiveness of end-capped acceptor A1 to acceptor units A0 present in reference molecule R. In designed molecule S2, the energy gap is shortly reduced to 2.50 eV, indicating the effect of the end-capped acceptor containing two CN groups present on each arm in A2 as compared to A1 with no CN group. The Eg of S3 is calculated to be lesser than that of the R, S1, and S2 molecules but greater than that of reference molecules S4–S6, indicating that the effectiveness of end-capped A3 in lowering the Eg is better than that of R, S1, and S2 but smaller than that of the S3–S6 end-capped acceptors, respectively. The effect of end-capped group modification is observed sharply in the S4 molecule, where the energy gap becomes abridged to 2.31 eV, which is 0.15 eV smaller than that of R. This reduction in Eg value might be due to the joint outcome of electron-withdrawing six F groups and extended conjugation in A4 rather than the efficiencies of the A0, A1, A2, and A3 end-capped acceptors. The energy gap is observed to be more abridged in S5. The lowest energy gap value of 2.27 eV is observed in designed molecule S5 among all studied (R, S1–S6) molecules. The Eg value of S5 is 0.19 eV less than the Eg value of reference molecule R. This reduction in Eg value validates that the combined effect of end-capped acceptor A5 containing two CN groups on each end-capped arm and the extended conjugation present in the S5 molecule successfully lowers the Eg value. The Eg is found to be narrow in S6 as compared to the R and S1–S4 molecules but slightly larger than the S5 value. This indicates that the performance of the two CN and two ester units present in end-capped group A6 is better than that of the A0 and A1–A4 acceptor units of R and S1–S4 but slightly smaller than that of the A5 end-capped acceptor present in the S5 molecule, respectively. Overall, the energy gap is found to be in the following increasing order: S5 < S6 < S4 < S3 < R < S2 < S1. In present studies, all designed molecules (S1–S6) have an energy gap lower and comparable to that of reference molecule R. Preceding discussion concludes that the performance of end-capped acceptor groups and band gap values shows an inverse relation and enlarged in the subsequent array: A5 > A6 >A4 >A3 >A0 > A2 >A1.

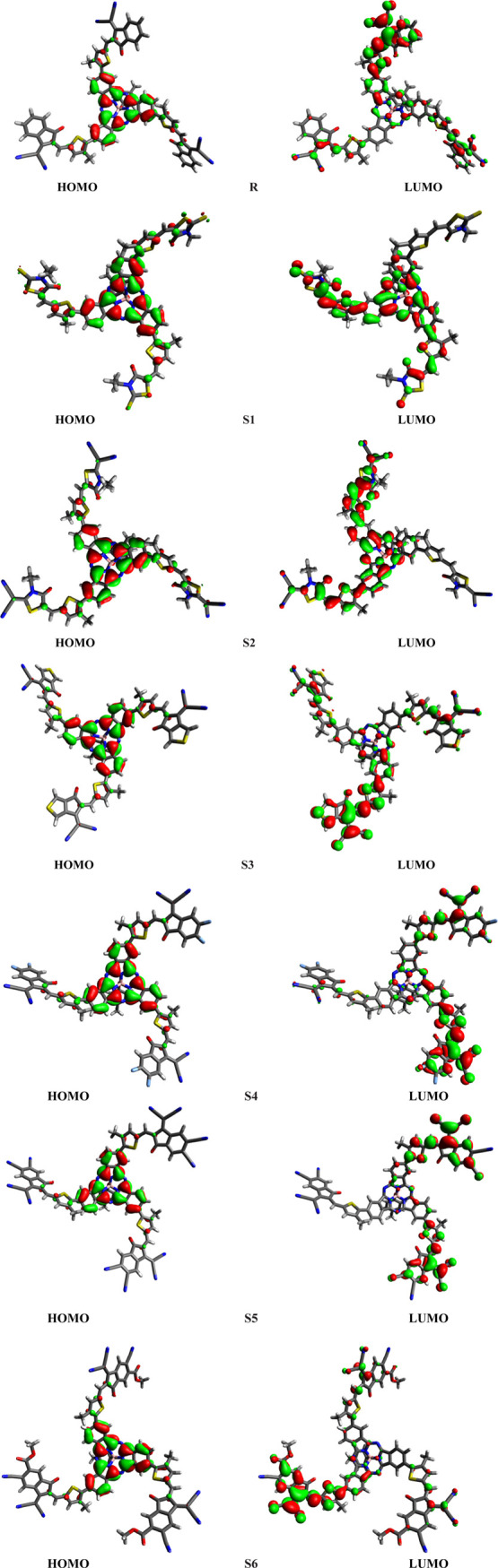

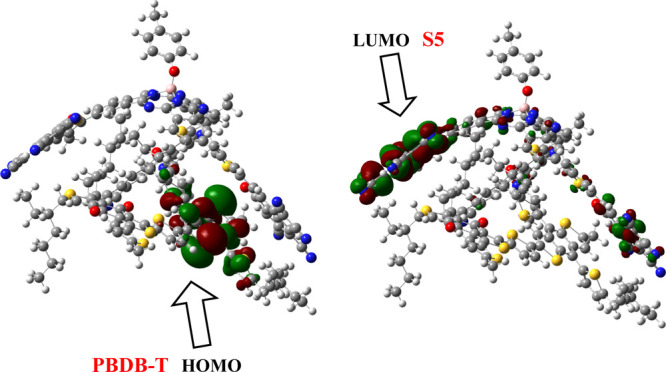

The pictographic display of the HOMO and LUMO of the R and S1–S6 molecules is portrayed in Figure 3. In all studied molecules (R and S1–S6), the HOMO charge density is populated over the SubPc core unit. The LUMO charge density on the other hand in R and S3–S6 is found to be concentrated mainly on end-capped acceptors A0 and A3–A6. However, in the S1 and S2 designed molecules, the LUMO orbital is populated partially on the bridge thiophene unit and mainly on end-capped acceptors A1 and A2, respectively. The LUMO level in all investigated acceptor molecules (R and S1–S6) is found to be lower than that of the well-known standard donor molecule PBDT-T, indicating the better CT and conduction of electric current in the designed molecules. These results combined with the HOMO–LUMO energy gap results point out that all designed molecules, especially S4–S6, facilitate the electron transfer from their HOMOs to LUMOs upon excitation. Thus, the designed molecules (S1–S6) may prove to be better sources for developing higher PCEs and large JSC solar cells. Therefore, these molecules could be considered better than the reference because of their better ability to transfer charge moieties.

Figure 3.

HOMOs and LUMOs of the investigated molecules.

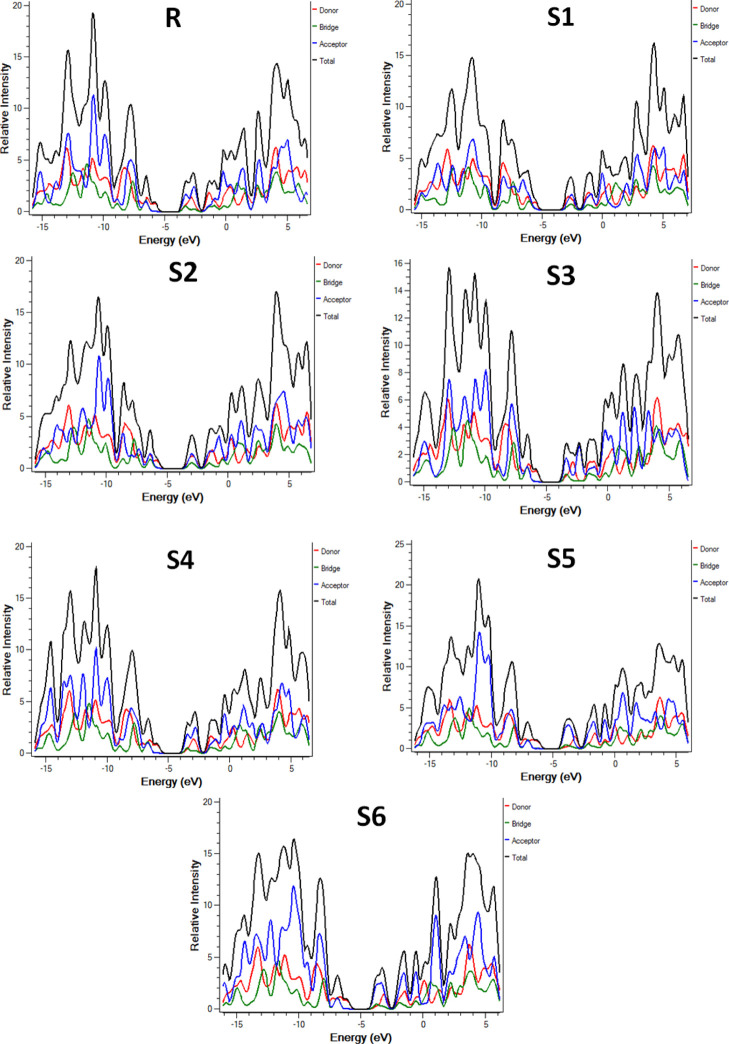

Partial DOS (PDOS) analysis is also performed in the support of FMO analysis. The DOS of the selected molecules R and S1–S6 was performed using the MPW1PW91/6-31G(d,p) functional for contribution analysis of each fragment in the total absorption band and electronic distribution. For this analysis, each selected molecule is divided into three fragments including the central SubPc core unit (D), thiophene bridge (B), and end-capped acceptors (A), as shown in Figure 4. The end-capped acceptors played a significant role in the total population that can be visualized from their contribution in each molecule. The central SubPc core unit (D) participation for delocalization of electrons in each molecule is also evident from Figure 4. These acceptors (A) are connected to the central SubPc core unit (D) through the bridge (B). The bridge unit also takes part in the delocalization of electrons because of the involvement of π-conjugation.

Figure 4.

DOS around the HOMOs and LUMO of the investigated molecules.

It is evident from the preceding discussion that end-capped group modification is a good strategy to tune the optoelectronic properties by lowering the energy gaps. Thus, all newly designed molecules S1–S6 can exhibit superior optoelectronic properties to reference R.

Optical Properties

The photophysical characteristics of our investigated molecules (R and S1–S6) are estimated from UV–visible analysis by performing TDDFT calculations in both the solvent and gas phases at the MPW1PW91/6-31G(d,p) level of theory. The CPCM model was used for estimation of photophysical characteristics of R and S1–S6 in chloroform. The results of transition energy (E), oscillator strengths (fos), maximum absorption wavelengths (λmax), and assignments representing the transition nature in the investigated compounds (R and S1–S6) calculated in the gas and solvent phases are listed in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Table 1. Computed Transition Energy (E), Maximum Absorption Wavelengths (λmax), Oscillator Strengths (fos), and Transition Nature of R and S1–S6 in eV Calculated at the DFT/MPW1PW91/6-31G (d,p) Level of Theory in the Gas Phase.

| molecules | calculated λmax (nm) | expected λmax (nm) | Ex (eV) | fos | major MO assignmentsa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | 596.73, 490.03 | 610, 490 | 2.07 | 0.69 | H → L + 1 (95%) |

| S1 | 548.55 | 2.26 | 0.84 | H → L + 1 (95%) | |

| S2 | 555.87 | 2.23 | 0.89 | H → L + 1 (95%) | |

| S3 | 605.21 | 2.04 | 0.67 | H → L + 1 (96%) | |

| S4 | 607.70 | 2.04 | 0.64 | H → L + 1 (96%) | |

| S5 | 669.38 | 1.85 | 0.44 | H → L + 1 (95%) | |

| S6 | 637.15 | 1.94 | 0.52 | H → L + 1 (96%) |

H = HOMO, L = LUMO.

Table 2. Computed Transition Energy (E), Maximum Absorption Wavelengths (λmax), Oscillator Strengths (fos), and Transition Nature of R and S1–S6 in eV Calculated at the DFT/MPW1PW91/6-31G (d,p) Level of Theory in the Solvent (Chloroform) Phase.

| molecules | calculated λmax (nm) | expected λmax (nm) | Ex (eV) | fos | major MO assignmentsa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | 616.92, 463.64 | 610, 490 | 2.00 | 0.83 | H → L + 1 (92%) |

| S1 | 565.64 | 2.19 | 0.99 | H → L + 1 (94%) | |

| S2 | 569.77 | 2.17 | 1.03 | H → L + 1 (94%) | |

| S3 | 624.34 | 1.98 | 0.82 | H → L + 1 (94%) | |

| S4 | 627.28 | 1.97 | 0.78 | H → L + 1 (94%) | |

| S5 | 698.77 | 1.77 | 0.50 | H → L + 1 (95%) | |

| S6 | 671.26 | 1.84 | 0.58 | H → L + 1 (93%) |

H = HOMO, L = LUMO.

The results tabulated in Table 2 point out that the main and secondary λmax peaks of reference molecule R are found at 616.92 and 463.64 nm, respectively, which are in good agreement with experimental reported λmax values of 610 and 490 nm. The results of Tables 1 and 2 describe that visible region absorption is shown by all investigated molecules (R and S1–S6). The increasing order of λmax values is observed as follows: S5 > S6 > S4 > S3 > R > S2 > S1 (in the gas phase) and S5 > S6 > S4 > S3 > R > S2 > S1 (in the solvent phase). The lowest λmax value among all investigated molecules (R and S1–S6) in both the solvent and gas phases is observed in the designed S1 molecule. In designed molecule S2, the λmax value slightly increased to 555.87 nm (gas) and 569.77 nm (solvent) as compared to the S1 molecule, indicating the better effect of the end-capped acceptor containing two CN groups present on each arm in A2 as compared to A1 with no CN group. The end-capped group modifications by the A3 acceptor enhance the λmax values of S3 to 605.21 nm (gas) and 624.34 nm (chloroform) from 596.73 nm (gas) and 616.92 nm (chloroform) of reference molecule R. The λmax values of S3 are computed to be larger than those of the R, S1, and S2 molecules but smaller than those of the S4–S6 molecules, indicating that the effectiveness of A3 in red-shifting the absorption maximum is better than that of R, S1, and S2 and smaller than that of S3–S6 end-capped acceptors, respectively. Further enhancement in absorption maximum value is noted in the S4 molecule with gas and solvent phase values of 607.70 and 627.28 nm, respectively. This shifting of the λmax values toward a longer range might be due to the mutual result of electron-withdrawing six F groups and extended conjugation existing in A4 in contrast to the efficiencies of the A0, A1, A2, and A3 end-capped acceptors. A large red shift and the highest λmax values among all investigated molecules (R and S1–S6) are noted in the designed S5 molecule, where the λmax values are found to be 669.38 nm (gas) and 698.77 nm (chloroform), which are 72.65 nm and 81.85 nm larger than the R molecule λmax values in the gas phase and solvent phase, respectively. Red shifting validates that the combined effect of end-capped acceptor A5 containing two CN groups on each end-capped arm and extended conjugation present in the S5 molecule successfully shifts the λmax value to a greater value. The results of the S5 molecule confirmed the better competence of end-capped acceptor moiety A5 owing to the strong pulling character shared with extensive conjugation of A5 as compared to the A0–A4 and A6 end-capped acceptors of the R, S1–S4, and S6 molecules, respectively. The λmax values of S6 in the gas and solvent phases are found to be 637.15 and 671.26 nm, respectively. These λmax values of S6 are larger than those of the R and S1–S4 molecules but slightly smaller than the S5 value. This indicates that the performance of the two CN and two ester units present in end-capped acceptor A6 is better than that of the A0 and A1–A4 acceptor units of R and S1–S4 but slightly smaller than the A5 end-capped acceptor performance present in the S5 molecule, respectively. The performance of the end-capped acceptors is found to be in the order: A5 > A6 > A4 >A3 > A0 > A2 > A1, which exactly matches with the end-capped group performance found in the reduction of energy band gaps. Furthermore, the declining λmax value order (S5 > S6 > S4 > S3 > R > S2 > S1) is found to be in good agreement with the increasing HOMO–LUMO energy gap order: S5 < S6 < S4 < S3 < R < S2 < S1, respectively, which is quite fascinating to design and develop high-performance 3D star-shaped SubPc-based NFA molecules with enhanced optoelectronic properties.

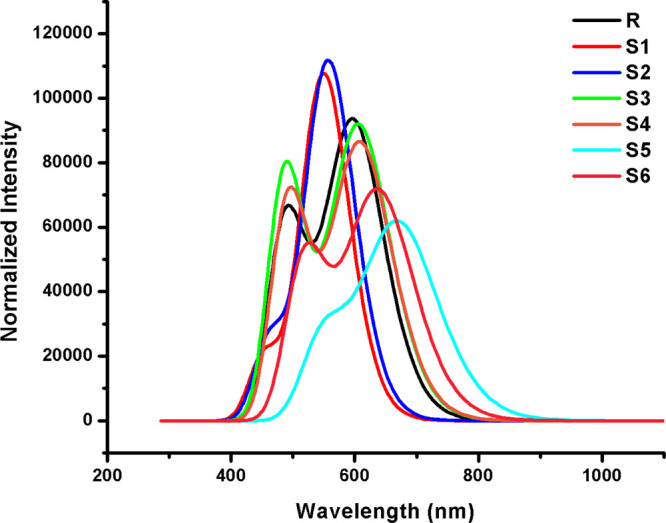

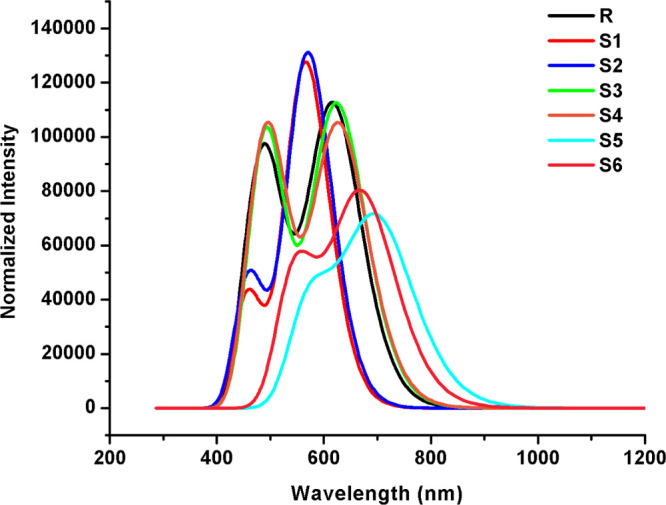

Figures 5 and 6 display two absorption peaks (primary and secondary) in the absorption spectrum of R and S1–S6 calculated in the gas and chloroform solvent phases, respectively. It can be seen from Figures 5 and 6 that end-capped acceptor moieties strongly affected the λmax values by causing a red shift in absorption spectra61,62 with low excitation energies and >92% transition from the HOMO to LUMO + 1 in all studied molecules.

Figure 5.

UV–visible absorption spectra (in the gas phase) of the investigated molecules.

Figure 6.

UV–visible absorption spectra (in the chloroform solvent) of the investigated molecules.

It is evident from the above discussion that end-capped group modification is a good strategy to tune the optoelectronic properties by lowering the transition energy and shifting the λmax values to the near-IR region. Thus, newly designed molecules may illustrate better optoelectronic properties than R, which prove their efficiency as NFA molecules for solar cell applications.

Excitation energy is another factor which enhanced the optoelectronic properties of OSCs. The lower excitation energy results in higher CTs and vice versa. Furthermore, the lower excitation energy leads to a higher PCE in OSCs. The increasing order of excitation energy of all investigated molecules is found to be S5 < S6 < S4 = S3 < R < S2 < S1 (in the gas phase) and S5 < S6 < S4 < S3 < R < S2 < S1 (in chloroform), which is the same as the HOMO–LUMO energy gap increasing order and the reverse of the absorption maximum value order as shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. These are also the characteristics of molecules that are suitable candidates to obtain fine optoelectronic properties.

Reorganization Energy

The Marcus equation63 played an important role in calculating the intramolecular reorganization energy, which in turn was used to estimate the consumption of energy when the geometry of the molecule changes from a neutral species to a charged species or a charged species to a neutral species.

| 3 |

In eq 3, the transfer rate of electrons is represented by kET. The electronic coupling present among different states is indicated by the symbol T. The calculations at the MPW1PW91/6-31G(d,p) functional are performed to estimate the electron λe and hole λh reorganization energy values of R and S1–S6, and the results are listed in Table S2 (Supporting Information).

It is evident from Table S2 that excellent results are presented by λe and λh statics. The λe value of R is observed as 0.00358 Eh, while the selected molecules (S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, and S6) are found to have λe values of 0.00680, 0.00662, 0.00355, 0.00355, 0.00232, and 0.00242, respectively. The declining order for the λe values of R and the structurally modeled S1–S6 molecules is found to be S5 < S6 < S4 < S3 < R < S2 < S1, which is in excellent agreement with the energy gap, transition energy, and absorption maximum value order. The λe values are observed to be smaller in S3–S6 but slightly larger than those of S1–S2 in contrast to reference R, indicating the high electron mobility in S3–S6 and slightly low but comparable electron mobility in S1–S2, respectively. The S5 molecule has the least value of electron reorganization, being the vital molecule for fine CT or mobility of electrons between acceptor and donor moieties.39,40,64−66 On the other hand, the hole reorganization (λh) energy value of R is noted as 0.00502 Eh. However, 0.00500, 0.00503, 0.00501, 0.00501, 0.00483, and 0.00496 Eh are the λh values observed in the designed S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, and S6 molecules, respectively. The decreasing order for λh values of the investigated molecules is found to be S5 < S6 < S1 < S3 = S4 < R < S2. This order implies that the designed molecules except S2 contain a smaller hole reorganization (λh) energy value, which results in better hole mobility as compared to reference molecule R. Overall, selected molecule S5 is computed as the best candidate for hole transport mobility among all investigated molecules (R and S1–S6) owing to its lowest λh value.

Open-Circuit Voltage

Open-circuit voltage (Voc) is another tool which is used to highlight the maximum working ability of OSCs. The OSC performance can be estimated by measuring the Voc values.67Voc is the maximum quantity of current that is taken from any optical equipment.53 Herein, the theoretical Voc values of R and S1–S6 are calculated using the Scharber equation:68

| 4 |

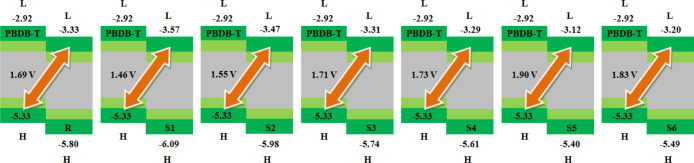

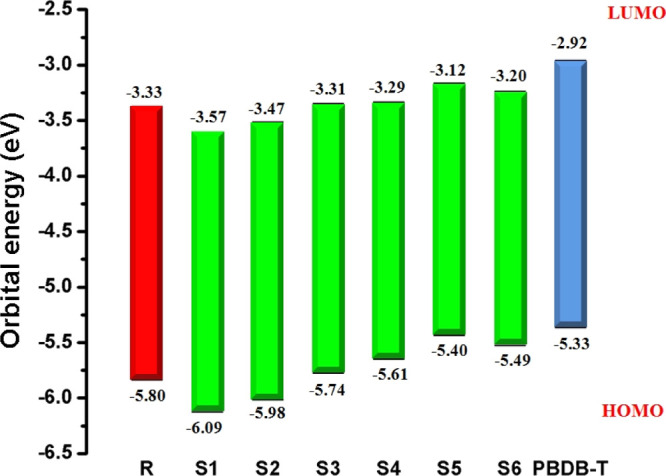

For fulfilling the terms of eq 4, the well-known standard donor polymeric material PBDB-T with HOMO and LUMO values of −5.33 and −2.92 eV, respectively,69 is used in this study and its HOMO level is compared with the LUMO levels of our acceptor molecules (R and S1–S6). The results obtained from eq 4 calculated with respect to the HOMOPBDB-T–LUMOacceptor energy gap are displayed in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Value of open-circuit voltage (Voc) of reference R and designed molecules S1–S6 with respect to the standard donor polymer PBDB-T.

The RVoc value with respect to HOMOPBTB-T–LUMOacceptor is computed to be 1.69 V. The Voc value in designed molecules S1 and S2 is found to be slightly smaller but comparable to that of reference molecule R, with values of 1.46 and 1.55 V, respectively. In S3, the Voc value is marked as 1.71 V, which is 0.2 V larger than that of R. Further increment in Voc value is noted in the S4 molecule with a Voc value of 1.73 V. An augmented Voc value is found in the case of the designed S5 and S6 molecules.

Overall, the highest Voc value of 1.90 V among all studied molecules is observed in S5, which is 0.21 V larger than that of R. The declining order of Voc values for all studied molecules with respect to the HOMOPBTB-T–LUMOacceptor energy gap is found to be S5 > S6 > S4 > S3 > R > S2 > S1, which is found to be in good agreement with the increasing order of the HOMO–LUMO energy gap of S5 < S6 < S4 < S3 < R < S2 < S1, respectively, which is quite fascinating to design and develop high-performance 3D star-shaped SubPc-based NFA molecules with enhanced optoelectronic properties. The Voc value mainly depends upon the level of LUMO of the acceptor and the level of HOMO of the donor as we mentioned above. A low-lying LUMO of the acceptor increases the shifting of electrons from the HOMO of donor molecules, which causes a higher Voc and directly enhances the optoelectronic properties. Therefore, the orbital energy diagram with respect to PBDB-T of all molecules is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Molecular orbital diagram of the investigated molecules with the PBDB-T donor.

It is evident from Figure 8 that the LUMO level of the acceptor investigated molecules (R and S1–S6) is lying below the LUMO level of the donor PBDB-T polymer. This alignment facilitates the easy shifting of charge density from the donor polymer to the designed acceptor molecules, which leads to easy CT and capacity of conduction from the donor to the acceptor unit and hence better optoelectronic properties of the investigated molecules. Overall, the LUMO level of designed molecule S5 exhibits the highest Voc value. This is due to end-capped acceptor group A5 and extended conjugation present in the S5 molecule, which lead to the robust Voc value as compared to other investigated molecules. Thus, M5 once again proved as the best candidate with a fine open-circuit voltage value for utilization in promising solar cell applications.

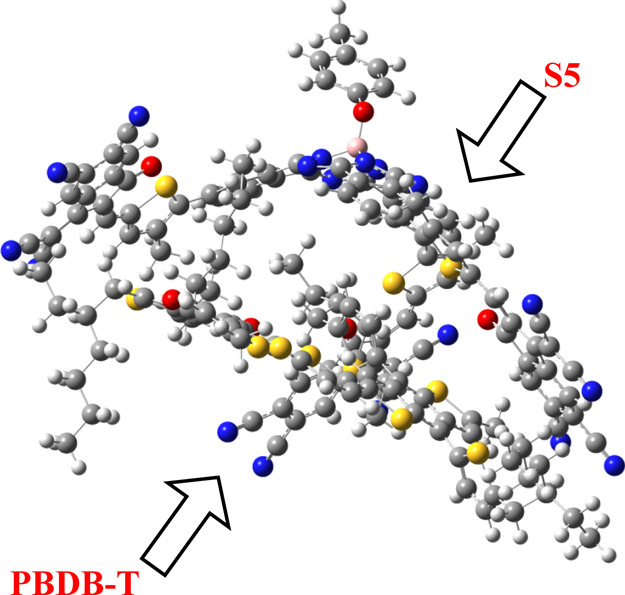

Charge-Transfer Analysis of Acceptor S5 and the Polymer Donor PBDB-T

To further strengthen the finding of better electron transport mobilities in the investigated molecules, CT analysis has been performed. Among all studied molecules (R and S1–S6), acceptor molecule S5 has the lowest energy gap, lowest transition energy, highest absorption maximum, lowest reorganization energy values of electrons and holes, and highest open-circuit voltage and hence has the highest electron-transfer rate. Thus, the S5 acceptor molecule is selected from all investigated molecules (R and S1–S5) in our study to form a complex with the donor polymer PBDB-T. The complex (PBDB-T/S5) is optimized at the MPW1PW91/6-31G(d,p) level of theory, and the optimized molecular geometry of the PBDB-T/S5 complex is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

CT between S5 and the polymer donor PBDB-T.

The optimized geometry of the S5/PBDB-T complex indicates that the orientation of S5 and the polymer PBDB-T is very interesting with respect to electron transfer. The central parts of the PBDB-T polymer and S5 molecule are oriented parallel to each other. To some extent, the terminal arms containing end-capped acceptor groups and alkyl chains of the donor polymer PBDB-T wrap around each other, which assist in excellent CT between the donor and acceptor units. The dipole moment of the complex was calculated, which is pointed out from PC61BM to D5. The direction of the dipole moment has been suggested as a reason for the efficient exciton dissociation at the D5/PC61BM interface.70−72 The presence of the dipole of the complex is due to electrostatic interactions of D5 and the polymer. The literature suggests that the dipole moment in such complexes is primarily directed by the polymer side. The direction of the dipole in our study is found to be in line with this statement.

To figure out the transfer of charge density, FMO analysis of the PBDB-T/S5 complex is executed at the MPW1PW91/6-31G(d,p) functional. The pictographic display of transfer of charge density in the PBDB-T/S5 complex is displayed in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Distribution patterns of the HOMO and LUMO of PBDB-T and S5.

The FMO diagram illustrates that the HOMO is basically present on the PBDB-T donor polymer, while the charge density for the LUMO is populated on the acceptor S5 molecule (Figure 10). Here, CT occurs from the PBDB-T donor to the S5 acceptor compound as shown in Figure 10. The HOMO part covers the central portion of the donor molecule, while the LUMO portion extends to the end-caped acceptor arm of the designed S5 molecule. We receive solid evidence from the density shift from the core unit of the PBDB-T polymer donor to the end-capped acceptor of S5, indicating excellent transfer of charges. The orbital analysis evidently represents that HOMO-to-LUMO excitation is in fact CT from the donor polymer unit to acceptor designed molecule S5. Hence, their combination is well-suited for an efficient solar cell assembly to give the maximum output voltage.

Such a transition in which charge is transferred from the donor to acceptor units provides vital confirmation of CT between different moieties and reveals the superposition of orbitals among molecules. Thus, the investigated molecule S5 stands to be best aspirant for developing high-performance 3D star-shaped SubPc-based NFA molecules with enhanced optoelectronic properties.

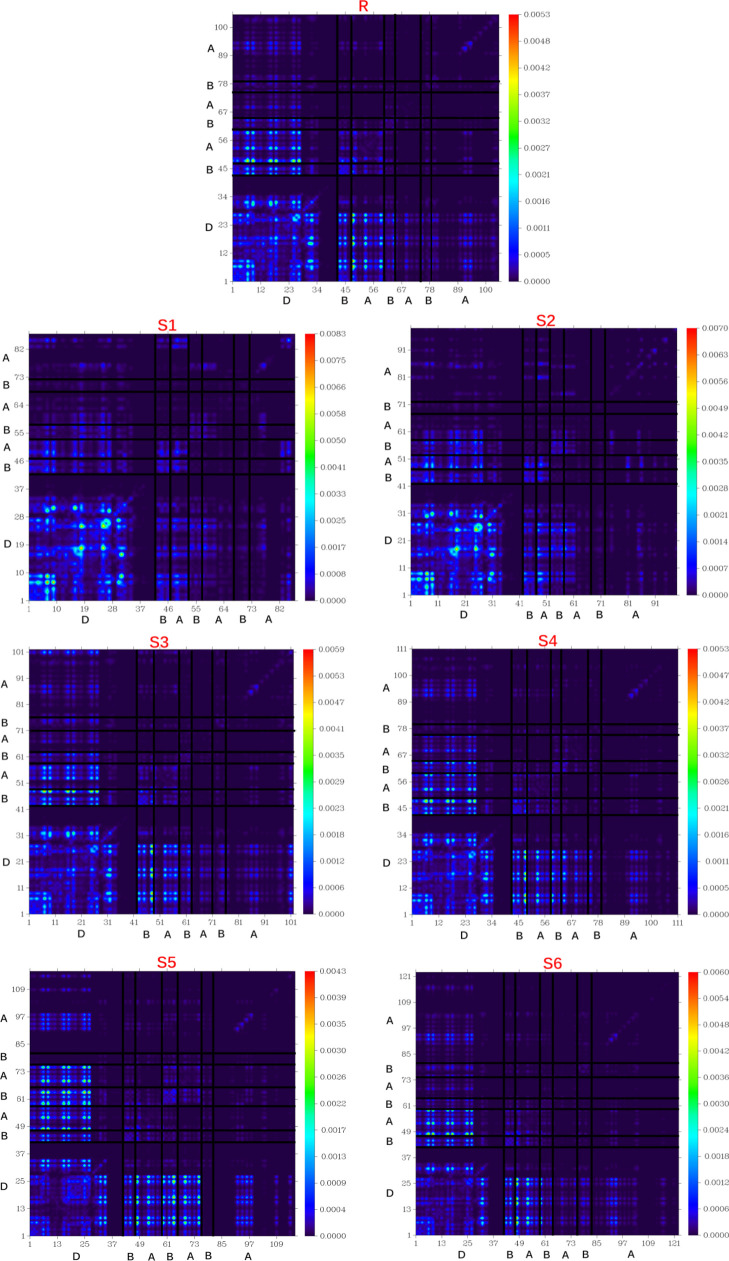

TDMs and Exciton Binding Energy (Eb)

TDM analysis describes the performance of solar cells in a way how electron density moves from the donor to acceptor molecules through π-conjugation within the molecule along with the insights of exciton generation and their utilization. In TDM analysis, the investigated molecules R and S1–S6 were analyzed in S1 and vacuum at the MPW1PW91/6-31G(d,p) level of theory. These molecules were divided according to their number of atoms (at the bottom and left side of Figure 11 and electron density on the right y-axis) including core (D), acceptor (A), and bridge (B) segments. The hydrogen atoms do not have much involvement in their representation, so these are basically ignored and deleted by default. The TDM results for R and S1–S6 are displayed in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

TDM surfaces of the investigated molecules at the S1 state.

According to the TDM diagrams, all molecules show charge coherence. A diagonal transfer of electron coherence is observed in all designed S1–S6 and reference R molecules. The electron coherence behavior of R and S1–S6 confirms that charge coherence successfully shifts from the donor core to the bridge, which transfers the electron density without trapping them toward end-capped acceptors. This implies that the coupling of the electrons of all investigated molecules, especially S5, may be lower with respect to the other investigated molecules, but it could show higher and easier exciton dissociation in the excited state. Figure 11 illustrates the TDM functionality and charge distribution, which is very convenient for solar cell development.

Binding energy is another promising factor for evaluation of optoelectronic properties. A lower binding energy results in a less Coulomb force between the hole and electron, which in the exited state provide enhanced exciton dissociation. Actually, the binding energy is estimated by the difference in the energy gap of HOMO–LUMO (Eg) and the first singlet exciton energy Eopt. These values represent the transfer of the exciton from the S0 (ground) state to the S1 (excited) state to give a pair of hole and electron.73,74 The binding energy (Eb) values can be estimated by eq 5, and the results are listed in Table 3.

| 5 |

Table 3. Calculated HOMO–LUMO Energy Gap EH–L, First Singlet Excitation Energies Eopt, and Exciton Binding Energies (Eb).

| molecules | EH–L (eV) | Eopt (eV) | Eb (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| R | 2.46 | 2.00 | 0.45 |

| S1 | 2.52 | 2.18 | 0.34 |

| S2 | 2.50 | 2.16 | 0.34 |

| S3 | 2.43 | 1.99 | 0.44 |

| S4 | 2.31 | 1.96 | 0.35 |

| S5 | 2.27 | 1.99 | 0.28 |

| S6 | 2.29 | 1.98 | 0.31 |

The binding energy of R is noted as 0.45 eV. The Eb values of S1–S6 are computed as 0.34, 0.34, 0.44, 0.35, 0.28, and 0.31 eV, respectively. It is observed that the binding energy of selected molecules S1–S6 is computed to be lesser than that of R. These calculated values indicate that compound S5 exhibits the lowest Eb value among all investigated molecules. Since reference R is a recently reported acceptor molecule being used is solar cells. Therefore, all designed molecules bearing small Eb values may show greater dissociation, which results in enhancement of overall current charge density. Furthermore, all investigated molecules (R and S1–S6) show a low binding energy, which enhanced exciton dissociation efficiency in the excited state by illustrating the separation of charges more effectively. Hence, because of Eb values less than that of reference R, all designed molecules can be utilized as novel star-shaped SubPc-based NFA molecules in solar cell applications.

It is evident from the preceding discussion that end-capped group modification is a good strategy to tune the optoelectronic properties by lowering the energy gaps. The declining λmax value order (S5 > S6 > S4 > S3 > R > S2 > S1) is found to be in good agreement with the increasing HOMO–LUMO energy gap and the λe value order of S5 < S6 < S4 < S3 < R < S2 < S1, respectively. The increasing order of excitation energy of all investigated molecules is found to be S5 < S6 < S4 = S3 < R < S2 < S1 (in the gas phase) and S5 < S6 < S4 < S3 < R < S2 < S1 (in chloroform), which is same as the HOMO–LUMO energy gap increasing order and the reverse of the absorption maximum value order. Similarly, the declining order of Voc values for all studied molecules with respect to the HOMOPBTB-T–LUMOacceptor energy gap is found to be S5 > S6 > S4 > S3 > R > S2 > S1, which is found to be in good agreement with the increasing order of HOMO–LUMO energy gap: S5 < S6 < S4 < S3 < R < S2 < S1, respectively. These calculated results are quite fascinating to design and develop high-performance 3D star-shaped SubPc-based NFA molecules with enhanced optoelectronic properties.

Conclusions

In summary, 3D star-shaped SubPc-based NFA molecules (S1–S6) are designed and quantum chemically explored to examine the CT behavior, optoelectronic properties, and structure–activity relationship for their potential exercise in solar cells. A reduction in energy band gap of up to 0.19 eV compared to R (2.46 eV) is observed in designed molecules S1–S6 with the band gap values in the ambience of 2.52–2.27 eV. The designed molecules S3–S6 showed a red shift in the absorption spectrum in the visible region and broader shift in the region of 605.21–669.38 nm (gas) and 624.34–698.77 (chloroform) than the R phase values of 596.73 nm (gas) and 616.92 nm (chloroform). The open-circuit voltages with respect to HOMOPBTB-T–LUMOacceptor are found to be larger than the R values in S3–S6 (1.71–1.90 V) and comparable to R in the S1 and S2 molecules. The binding energy of designed molecules S1–S6 is found to be lower than that of reference R, which results in high exciton dissociation in the excited state. The reorganization energies of electrons and holes are found to be less than that of R in S3–S6 and comparable to R in the S1 and S2 molecules. Overall, the decreasing order of open-circuit voltage and λmax values (S5 > S6 > S4 > S3 > R > S2 > S1) is found to be in good agreement with the increasing order of HOMO–LUMO energy gap, excitation energy, and reorganization energies of holes and electron: S5 < S6 < S4 < S3 < R < S2 < S1, respectively, which is quite fascinating to design and develop high-performance 3D star-shaped SubPc-based NFA molecules with enhanced optoelectronic properties. Among all investigated molecules, S5 due to the combination of extended conjugation and electron-withdrawing capability of end-capped acceptor moiety A5 is proven as the best candidate owing to promising photovoltaic properties including the lowest band gap (2.27 eV), smallest λe = 0.00232 eV and λh = 0.00483 eV, highest λmax values of 669.38 nm (in the gas) and 698.77 nm (in chloroform), and highest Voc = 1.90 V with respect to HOMOPTB7-Th–LUMOacceptor. Our results indicate that introducing more end-capped electron-accepting units is a simple and effective alternative strategy for the design of promising NFA molecules. This study proves that the conceptualized 3D star-shaped SubPc-based NFAs, especially S5, are superior and thus recommended for the future construction of high-performance OSC devices.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR), King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, under grant no. D-238-130-1441. The authors therefore gratefully acknowledge DSR technical and financial support.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c02766.

Optimized Cartesian coordinates of our studied compounds (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Notes

The raw data required to reproduce these findings are available. The processed data required to reproduce these findings are available.

Supplementary Material

References

- Cheng P.; Li G.; Zhan X.; Yang Y. Next-generation organic photovoltaics based on non-fullerene acceptors. Nat. Photonics 2018, 12, 131–142. 10.1038/s41566-018-0104-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kan B.; Feng H.; Wan X.; Liu F.; Ke X.; Wang Y.; Wang Y.; Zhang H.; Li C.; Hou J.; Chen Y. Small-molecule acceptor based on the heptacyclic benzodi (cyclopentadithiophene) unit for highly efficient nonfullerene organic solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 4929–4934. 10.1021/jacs.7b01170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F.; Zhou Z.; Zhang C.; Vergote T.; Fan H.; Liu F.; Zhu X. A thieno [3, 4-b] thiophene-based non-fullerene electron acceptor for high-performance bulk-heterojunction organic solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 15523–15526. 10.1021/jacs.6b08523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S.; Zhan L.; Liu F.; Ren J.; Shi M.; Li C.-Z.; Russell T. P.; Chen H. An Unfused-Core-Based Nonfullerene Acceptor Enables High-Efficiency Organic Solar Cells with Excellent Morphological Stability at High Temperatures. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1705208. 10.1002/adma.201705208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W.; Ye L.; Li S.; Yao H.; Ade H.; Hou J. A High-Efficiency Organic Solar Cell Enabled by the Strong Intramolecular Electron Push–Pull Effect of the Nonfullerene Acceptor. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1707170. 10.1002/adma.201707170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y.; Zhang Z.-G.; Bai H.; Wang J.; Yao Y.; Li Y.; Zhu D.; Zhan X. High-performance fullerene-free polymer solar cells with 6.31% efficiency. Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 610–616. 10.1039/c4ee03424d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y.; Bai H.; Wang Z.; Cheng P.; Zhu S.; Wang Y.; Ma W.; Zhan X. A planar electron acceptor for efficient polymer solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 3215–3221. 10.1039/c5ee02477c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z.; Yu J.; Yin X.; Hu Z.; Jiang Y.; Sun J.; Zhou J.; Zhang F.; Russell T. P.; Liu F.; Tang W. Conformation Locking on Fused-Ring Electron Acceptor for High-Performance Nonfullerene Organic Solar Cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1705095. 10.1002/adfm.201705095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W.; Li S.; Yao H.; Zhang S.; Zhang Y.; Yang B.; Hou J. Molecular optimization enables over 13% efficiency in organic solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 7148–7151. 10.1021/jacs.7b02677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S. j.; Zhou Z.; Liu W.; Zhang Z.; Liu F.; Yan H.; Zhu X. A Twisted Thieno [3, 4-b] thiophene-Based Electron Acceptor Featuring a 14-π-Electron Indenoindene Core for High-Performance Organic Photovoltaics. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1704510. 10.1002/adma.201704510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y.; Wang Y.; Wang J.; Hou J.; Li Y.; Zhu D.; Zhan X. A Star-Shaped Perylene Diimide Electron Acceptor for High-Performance Organic Solar Cells. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 5137–5142. 10.1002/adma.201400525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin K.; Xie B.; Wang Z.; Xie R.; Huang Y.; Duan C.; Huang F.; Cao Y. Star-shaped electron acceptors containing a truxene core for non-fullerene solar cells. Org. Electron. 2018, 52, 42–50. 10.1016/j.orgel.2017.10.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y.; Cheng P.; Li Y.; Zhan X. A 3D star-shaped non-fullerene acceptor for solution-processed organic solar cells with a high open-circuit voltage of 1.18 V. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 4773–4775. 10.1039/c2cc31511d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu N.; Yang X.; Zhang H.; Wan X.; Li C.; Liu F.; Zhang H.; Russell T. P.; Chen Y. Nonfullerene small molecular acceptors with a three-dimensional (3D) structure for organic solar cells. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 6770–6778. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.6b03323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H.; Sun P.; Zhang C.; Yang Y.; Gao X.; Chen F.; Xu Z.; Chen Z.-K.; Huang W. High-performance organic solar cells based on a non-fullerene acceptor with a spiro core. Chem.—Asian J. 2017, 12, 721–725. 10.1002/asia.201601741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S.; Liu W.; Shi M.; Mai J.; Lau T.-K.; Wan J.; Lu X.; Li C.-Z.; Chen H. A spirobifluorene and diketopyrrolopyrrole moieties based non-fullerene acceptor for efficient and thermally stable polymer solar cells with high open-circuit voltage. Energy Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 604–610. 10.1039/c5ee03481g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Li Y.; Huang J.; Hu H.; Zhang G.; Ma T.; Chow P. C. Y.; Ade H.; Pan D.; Yan H. Ring-fusion of perylene diimide acceptor enabling efficient nonfullerene organic solar cells with a small voltage loss. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 16092–16095. 10.1021/jacs.7b09998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W.; Zhang G.; Xu X.; Wang S.; Li Y.; Peng Q. Wide bandgap molecular acceptors with a truxene core for efficient nonfullerene polymer solar cells: linkage position on molecular configuration and photovoltaic properties. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1707493. 10.1002/adfm.201707493. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang M.; Wang Y.; Qiu N.; Yi Y.-Q.-Q.; Wan X.; Li C.; Chen Y. A Three-dimensional Non-fullerene Small Molecule Acceptor for Solution-processed Organic Solar Cells. Chin. J. Chem. 2017, 35, 1687–1692. 10.1002/cjoc.201700399. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morse G. E.; Bender T. P. Boron subphthalocyanines as organic electronic materials. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 4, 5055–5068. 10.1021/am3015197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claessens C. G.; González-Rodríguez D.; Rodríguez-Morgade M. S.; Medina A.; Torres T. Subphthalocyanines, subporphyrazines, and subporphyrins: Singular nonplanar aromatic systems. Chem. Rev. 2013, 114, 2192–2277. 10.1021/cr400088w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaumont N.; Castrucci J. S.; Sullivan P.; Morse G. E.; Paton A. S.; Lu Z.-H.; Bender T. P.; Jones T. S. Acceptor properties of boron subphthalocyanines in fullerene free photovoltaics. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 14813–14823. 10.1021/jp503578g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cnops K.; Rand B. P.; Cheyns D.; Verreet B.; Empl M. A.; Heremans P. 8.4% efficient fullerene-free organic solar cells exploiting long-range exciton energy transfer. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3406. 10.1038/ncomms4406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hang H.; Wu X.; Xu Q.; Chen Y.; Li H.; Wang W.; Tong H.; Wang L. Star-shaped small molecule acceptors with a subphthalocyanine core for solution-processed non-fullerene solar cells. Dyes Pigm. 2019, 160, 243–251. 10.1016/j.dyepig.2018.07.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J.; Trucks G. W.; Schlegel H. B.; Scuseria G.; Robb M. A.; Cheeseman J. R.; Scalmani G.; Barone V.; Mennucci B.; Petersson G.; Nakatsuji H.; Caricato M.; Li X.; Hratchian H. P.; Izmaylov A. F.; Bloino J.; Zheng G.; Sonnenberg J. L.; Hada M.; Ehara M.; Toyota K.; Fukuda R.; Hasegawa J.; Ishida M.; Nakajima T.; Honda Y.; Kitao O.; Nakai H.; Vreven T.; Montgomery J. A.; Peralta J. E.; Ogliaro F.; Bearpark M.; Heyd J. J.; Brothers E.; Kudin K. N.; Staroverov V. N.; Kobayashi R.; Normand J.; Raghavachari K.; Rendell A.; Burant J. C.; Iyengar S. S.; Tomasi J.; Cossi M.; Rega N.; Millam J. M.; Klene M.; Knox J. E.; Cross J. B.; Bakken V.; Adamo C.; Jaramillo J.; Gomperts R.; Stratmann R. E.; Yazyev O.; Austin A. J.; Cammi R.; Pomelli C.; Ochterski J. W.; Martin R. L.; Morokuma K.; Zakrzewski V. J.; Voth G. A.; Salvador P.; Dannenberg J. J.; Dapprich S.; Daniels A. D.; Farkas O.; Foresman J. B.; Ortiz J. V.; Cioslowski J.; Fox D. J.. D. 0109, Revision D. 01; Gaussian. Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2009.

- Dennington R. D.; Keith T. A.; Millam J. M.. GaussView 5.0. 8; Gaussian Inc., 2008.

- Zhao Y.; Truhlar D. G. The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2008, 120, 215–241. 10.1007/s00214-007-0310-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iikura H.; Tsuneda T.; Yanai T.; Hirao K. A long-range correction scheme for generalized-gradient-approximation exchange functionals. J. Chem. Phys. 2001, 115, 3540–3544. 10.1063/1.1383587. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chai J.-D.; Head-Gordon M. Long-range corrected hybrid density functionals with damped atom–atom dispersion corrections. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008, 10, 6615–6620. 10.1039/b810189b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamo C.; Barone V. Exchange functionals with improved long-range behavior and adiabatic connection methods without adjustable parameters: The m PW and m PW1PW models. J. Chem. Phys. 1998, 108, 664–675. 10.1063/1.475428. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yanai T.; Tew D. P.; Handy N. C. A new hybrid exchange–correlation functional using the Coulomb-attenuating method (CAM-B3LYP). Chem. Phys. Lett. 2004, 393, 51–57. 10.1016/j.cplett.2004.06.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Civalleri B.; Zicovich-Wilson C. M.; Valenzano L.; Ugliengo P. B3LYP augmented with an empirical dispersion term (B3LYP-D*) as applied to molecular crystals. CrystEngComm 2008, 10, 405–410. 10.1039/b715018k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ans M.; Paramasivam M.; Ayub K.; Ludwig R.; Zahid M.; Xiao X.; Iqbal J. Designing alkoxy-induced based high performance near infrared sensitive small molecule acceptors for organic solar cells. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 305, 112829. 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.112829. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Afzal Z.; Hussain R.; Khan M. U.; Khalid M.; Iqbal J.; Alvi M. U.; Adnan M.; Ahmed M.; Mehboob M. Y.; Hussain M. Designing indenothiophene-based acceptor materials with efficient photovoltaic parameters for fullerene-free organic solar cells. J. Mol. Model. 2020, 26, 137. 10.1007/s00894-020-04386-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain R.; Khan M. U.; Mehboob M. Y.; Khalid M.; Iqbal J.; Ayub K.; Adnan M.; Ahmed M.; Atiq K.; Mahmood K. Enhancement in Photovoltaic Properties of N, N-diethylaniline based Donor Materials by Bridging Core Modifications for Efficient Solar Cells. ChemistrySelect 2020, 5, 5022–5034. 10.1002/slct.202000096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M. U.; Iqbal J.; Khalid M.; Hussain R.; Braga A. A. C.; Hussain M.; Muhammad S. Designing triazatruxene-based donor materials with promising photovoltaic parameters for organic solar cells. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 26402–26418. 10.1039/c9ra03856f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ans M.; Iqbal J.; Eliasson B.; saif M. J.; Ayub K. Opto-electronic properties of non-fullerene fused-undecacyclic electron acceptors for organic solar cells. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2019, 159, 150–159. 10.1016/j.commatsci.2018.12.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ans M.; Ayub K.; Bhatti I. A.; Iqbal J. Designing indacenodithiophene based non-fullerene acceptors with a donor–acceptor combined bridge for organic solar cells. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 3605–3617. 10.1039/c8ra09292c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M. U.; Mehboob M. Y.; Hussain R.; Afzal Z.; Khalid M.; Adnan M. Designing spirobifullerene core based three-dimensional cross shape acceptor materials with promising photovoltaic properties for high-efficiency organic solar cells. Int. J. Quantum Chem 2020, e26377 10.1002/qua.2637. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mehboob M. Y.; Hussain R.; Khan M. U.; Adnan M.; Umar A.; Alvi M. U.; Ahmed M.; Khalid M.; Iqbal J.; Akhtar M. N.; Zafar F.; Shahi M. N. Designing N-phenylaniline-triazol Configured Donor Materials with Promising Optoelectronic Properties for High-Efficiency Solar Cells. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2020, 1186, 112908. 10.1016/j.comptc.2020.112908. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ans M.; Ayub K.; Muhammad S.; Iqbal J. Development of fullerene free acceptors molecules for organic solar cells: A step way forward toward efficient organic solar cells. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2019, 1161, 26–38. 10.1016/j.comptc.2019.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ajmal M.; Ali U.; Javed A.; Tariq A.; Arif Z.; Iqbal J.; Shoaib M.; Ahmed T. Designing indaceno thiophene–based three new molecules containing non-fullerene acceptors as strong electron withdrawing groups with DFT approaches. J. Mol. Model. 2019, 25, 311. 10.1007/s00894-019-4198-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z.; Liu C.; Shao C.; Zeng X.; Cao D. Screening π-conjugated bridges of organic dyes for dye-sensitized solar cells with panchromatic visible light harvesting. Nanotechnology 2016, 27, 265701. 10.1088/0957-4484/27/26/265701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z.; Wang D.; Bai X.; Shao C.; Cao D. Designing triphenylamine derivative dyes for highly effective dye-sensitized solar cells with near-infrared light harvesting up to 1100 nm. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 48750–48757. 10.1039/c4ra09444a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z.; Liu Y.; Liu C.; Lin C.; Shao C. TDDFT screening auxiliary withdrawing group and design the novel DA-π-A organic dyes based on indoline dye for highly efficient dye-sensitized solar cells. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2016, 167, 127–133. 10.1016/j.saa.2016.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ans M.; Iqbal J.; Eliasson B.; Saif M. J.; Javed H. M. A.; Ayub K. Designing of non-fullerene 3D star-shaped acceptors for organic solar cells. J. Mol. Model. 2019, 25, 129. 10.1007/s00894-019-3992-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irfan M.; Eliason B.; Mahr M. S.; Iqbal J. Tuning the optoelectronic properties of naphtho-dithiophene-based A-D-A type small donor molecules for bulk hetero-junction organic solar cells. ChemistrySelect 2018, 3, 2352–2358. 10.1002/slct.201702764. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barone V.; Cossi M. Quantum calculation of molecular energies and energy gradients in solution by a conductor solvent model. J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102, 1995–2001. 10.1021/jp9716997. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gorelsky S.SWizard Program; University of Ottawa: Ottawa, Canada, 2010. There is no corresponding record for this reference.[Google Scholar] 2013.

- O’boyle N. M.; Tenderholt A. L.; Langner K. M. Cclib: a library for package-independent computational chemistry algorithms. J. Comput. Chem. 2008, 29, 839–845. 10.1002/jcc.20823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T.; Chen F. Multiwfn: a multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 580–592. 10.1002/jcc.22885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus R. A. Electron transfer reactions in chemistry. Theory and experiment. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1993, 65, 599. 10.1103/revmodphys.65.599. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang S.; Zhang J. Design of donors with broad absorption regions and suitable frontier molecular orbitals to match typical acceptors via substitution on oligo (thienylenevinylene) toward solar cells. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 1353–1363. 10.1002/jcc.22966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma W.; Jiao Y.; Meng S. Modeling charge recombination in dye-sensitized solar cells using first-principles electron dynamics: effects of structural modification. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 17187–17194. 10.1039/c3cp52458b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M. U.; Khalid M.; Ibrahim M.; Braga A. A. C.; Safdar M.; Al-Saadi A. A.; Janjua M. R. S. A. First Theoretical Framework of Triphenylamine–Dicyanovinylene-Based Nonlinear Optical Dyes: Structural Modification of π-Linkers. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 4009–4018. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b12293. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Janjua M. R. S. A.; Khan M. U.; Bashir B.; Iqbal M. A.; Song Y.; Naqvi S. A. R.; Khan Z. A. Effect of π-conjugation spacer (C C) on the first hyperpolarizabilities of polymeric chain containing polyoxometalate cluster as a side-chain pendant: A DFT study. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2012, 994, 34–40. 10.1016/j.comptc.2012.06.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Janjua M. R. S. A.; Amin M.; Ali M.; Bashir B.; Khan M. U.; Iqbal M. A.; Guan W.; Yan L.; Su Z.-M. A DFT Study on The Two-Dimensional Second-Order Nonlinear Optical (NLO) Response of Terpyridine-Substituted Hexamolybdates: Physical Insight on 2D Inorganic–Organic Hybrid Functional Materials. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 2012, 705–711. 10.1002/ejic.201101092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M. U.; Ibrahim M.; Khalid M.; Qureshi M. S.; Gulzar T.; Zia K. M.; Al-Saadi A. A.; Janjua M. R. S. A. First theoretical probe for efficient enhancement of nonlinear optical properties of quinacridone based compounds through various modifications. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2019, 715, 222–230. 10.1016/j.cplett.2018.11.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M. U.; Ibrahim M.; Khalid M.; Braga A. A. C.; Ahmed S.; Sultan A. Prediction of Second-Order Nonlinear Optical Properties of D–p–A Compounds Containing Novel Fluorene Derivatives: A Promising Route to Giant Hyperpolarizabilities. J. Cluster Sci. 2019, 30, 415–430. 10.1007/s10876-018-01489-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M. U.; Ibrahim M.; Khalid M.; Jamil S.; Al-Saadi A. A.; Janjua M. R. S. A. Quantum Chemical Designing of Indolo [3, 2, 1-jk] carbazole-based Dyes for Highly Efficient Nonlinear Optical Properties. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2019, 719, 59–66. 10.1016/j.cplett.2019.01.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mutailipu M.; Xie Z.; Su X.; Zhang M.; Wang Y.; Yang Z.; Janjua M. R. S. A.; Pan S. Chemical cosubstitution-oriented design of rare-earth borates as potential ultraviolet nonlinear optical materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 18397–18405. 10.1021/jacs.7b11263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janjua M. R. S. A. Quantum mechanical design of efficient second-order nonlinear optical materials based on heteroaromatic imido-substituted hexamolybdates: First theoretical framework of POM-based heterocyclic aromatic rings. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 51, 11306–11314. 10.1021/ic3002652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus R. A. Chemical and electrochemical electron-transfer theory. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 1964, 15, 155–196. 10.1146/annurev.pc.15.100164.001103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shehzad R. A.; Iqbal J.; Khan M. U.; Hussain R.; Javed H. M. A.; Rehman A. U.; Alvi M. U.; Khalid M. Designing of benzothiazole based non-fullerene acceptor (NFA) molecules for highly efficient organic solar cells. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2020, 1181, 112833. 10.1016/j.comptc.2020.112833. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ans M.; Manzoor F.; Ayub K.; Nawaz F.; Iqbal J. Designing dithienothiophene (DTT)-based donor materials with efficient photovoltaic parameters for organic solar cells. J. Mol. Model. 2019, 25, 222. 10.1007/s00894-019-4108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ans M.; Iqbal J.; Bhatti I. A.; Ayub K. Designing dithienonaphthalene based acceptor materials with promising photovoltaic parameters for organic solar cells. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 34496–34505. 10.1039/c9ra06345e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irfan M.; Iqbal J.; Sadaf S.; Eliasson B.; Rana U. A.; Ud-din Khan S.; Ayub K. Design of donor–acceptor–donor (D–A–D) type small molecule donor materials with efficient photovoltaic parameters. Int. J. Quantum Chem 2017, 117, e25363 10.1002/qua.25363. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scharber M. C.; Mühlbacher D.; Koppe M.; Denk P.; Waldauf C.; Heeger A. J.; Brabec C. J. Design rules for donors in bulk-heterojunction solar cells—Towards 10% energy-conversion efficiency. Adv. Mater. 2006, 18, 789–794. 10.1002/adma.200501717. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W.; Qian D.; Zhang S.; Li S.; Inganäs O.; Gao F.; Hou J. Fullerene-free polymer solar cells with over 11% efficiency and excellent thermal stability. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 4734–4739. 10.1002/adma.201600281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arkhipov V. I.; Heremans P.; Bässler H. Why is exciton dissociation so efficient at the interface between a conjugated polymer and an electron acceptor?. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2003, 82, 4605–4607. 10.1063/1.1586456. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marchiori C. F. N.; Koehler M. Dipole assisted exciton dissociation at conjugated polymer/fullerene photovoltaic interfaces: A molecular study using density functional theory calculations. Synth. Met. 2010, 160, 643–650. 10.1016/j.synthmet.2009.12.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koehler M.; Santos M. C.; Da Luz M. G. E. Positional disorder enhancement of exciton dissociation at donor/ acceptor interface. J. Appl. Phys. 2006, 99, 053702. 10.1063/1.2174118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Köse M. E. Evaluation of acceptor strength in thiophene coupled donor–acceptor chromophores for optimal design of organic photovoltaic materials. J. Phys. Chem. A 2012, 116, 12503–12509. 10.1021/jp309950f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dkhissi A. Excitons in organic semiconductors. Synth. Met. 2011, 161, 1441–1443. 10.1016/j.synthmet.2011.04.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.