Abstract

We report a case of hemodynamic instability due to bradycardia on the basis of severe hyperkalemia. Diabetic ketoacidosis and acute kidney injury together with polypharmacy triggered the acute onset. Potentially life‐threatening hyperkalemia is often induced by drug interactions. ECG features may be crucial for diagnosis, and treatment depends on setting and resources.

Keywords: electrocardiogram, hyperkalemia, ketoacidosis, polypharmacy

We report a case of hemodynamic instability due to bradycardia on the basis of severe hyperkalemia. Diabetic ketoacidosis and acute kidney injury together with polypharmacy triggered the acute onset. Potentially life‐threatening hyperkalemia is often induced by drug interactions. ECG features may be crucial for diagnosis, and treatment depends on setting and resources.

1. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

1.1. Definition and mechanism

Hyperkalemia is defined as a serum potassium concentration exceeding 5.0 mEq/L. The incidence in hospitalized patients ranges from 1% to 10%, and mortality amounts up to 1 per 1000. 1 , 2 The main underlying mechanisms can be summed up as: (a) impaired renal excretion system (caused by reduced glomerular filtration rate/reabsorption in the proximal tubule/secretion in the distal convoluted tubule and collecting duct), (b) impaired or pharmaceutically inhibited renin‐angiotensin system (RAS), triggered by effects of hormones such as aldosterone or vasopressin, (c) reduced cardiac output (due to impaired renal perfusion), (d) insulin deficiency (caused by impaired transportation of potassium from extra‐ to intracellular spaces), and (e) acidosis (through increased shift of potassium to the extracellular space on an ubiquitous cellular level and by decreased secretion and increased reabsorption in the collecting duct). Further reasons of hyperkalemia can include extensive tissue breakdown such as in rhabdomyolysis, burns, or trauma. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6

Daily practice shows that hyperkalemia is a frequent consequence of multi‐drug use, especially in elderly patients and patients with reduced kidney function. 7 While it has been demonstrated that an increased prescription rate of spironolactone has the potential of increasing the rate of hospitalization for hyperkalemia, 8 simultaneous intake of angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB), and anti‐aldosterone medication is not recommended. 9 , 10 However, in the special subgroup of heart failure patients, combined RAS blockage is a treatment cornerstone and is often underused due to emerging situations of hyperkalemia. 11 This discrepancy might be alleviated by new therapeutic recommendations (eg, for sacubitril/valsartan) or the increased concomitant use of potassium binders. 12 Nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAID) cause renal afferent arteriolar vasoconstriction through inhibition of prostacyclin synthesis and may therefore further aggravate interactions. 13 , 14 Apart from “classic” potassium‐increasing medication, hyperkalemia can also be a lesser‐known side effect of other routinely used drugs, for example, heparin. 1 , 15

1.2. Clinical features

Hyperkalemic patients often present with symptoms such as weakness, flaccid paralysis, paresthesia, and depressed tendon reflexes. Furthermore, specific changes in electrocardiogram (ECG) often occur at potassium levels of >6.7 mmol/L and are strongly associated with mortality. 5 Although these findings are typical, studies have frequently shown a delay of the final diagnosis of hyperkalemia. Moreover, a definite diagnosis can be impeded by the degree of acuity of serum potassium changes and the patient's possible adaptation to chronic hyperkalemia. 5 , 16 , 17 Potentially life‐threatening conditions can be recognized through early ECG analysis and interpretation. Under normal conditions, the large gradient between intra‐ and extracellular potassium concentration contributes to cell excitability. In cardiac tissue, cardiotoxic effects of high serum potassium are due to an accelerated repolarization phase and reduced velocity in the specific signal‐generating and conduction system: Mild hyperkalemia causes the resting membrane potential to become less negative and therefore acts in a positive chronotropic fashion (hyperexcitability). When potassium levels increase, the more positive resting membrane potential leads to inactivation of sodium channels. Therefore, a slowing of impulse conduction through the myocardium, a prolongation of membrane depolarization, and a negative chronotropic effect occur. 18 , 19

Characteristic electrocardiographic findings include a narrow, peaked T‐wave, a prolonged PR interval, a diminished P‐wave amplitude, QRS widening (eventually merging into a QRST complex and a sine wave pattern), asystole, or ventricular fibrillation. Typically, the heart rate is reduced, and slowing of electrical conduction may lead to a block on various levels (sinu‐atrial, atrioventricular, and fascicular/bundle branch block). 5 , 16 , 17 , 20 , 21 In patients with Wolff‐Parkinson‐White syndrome, the delta wave can be lost due to a block of bypass tracts. This phenomenon appears because of a higher potassium sensitivity of accessory pathway tissue than in the AV node. 22

1.3. Therapeutic options

Evidence‐based treatment options consider both symptoms and the degree and acuity of the increase in serum potassium. Current recommendations pay special attention to (peri‐) arrest situations since hyperkalemia is the most common electrolyte disturbance associated with cardiac arrest. Three crucial strategies are as follows: cardiac protection, shift of potassium to the intracellular compartment, and serum potassium elimination. 5 , 23 Table 1 gives an overview of pharmacologic therapeutic approaches.

TABLE 1.

| Substance and dosage | Onset | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Potassium exchange resins (eg, 15‐30 g of calcium resonium enterally) | >4 h | Potassium elimination |

| Insulin/glucose (eg, 10 IU of fast‐acting insulin in 25 g of glucose intravenously) | 15‐30 min, maximum effect at 30‐60 min | Shift of potassium to intracellular space |

| Beta‐2 mimetics (eg, 10‐20 mg of salbutamol per nebulizer or 0.5 mg of terbutaline subcutaneously/intravenously) | 15‐30 min | Shift of potassium to intracellular space |

| Loop diuretics (eg, 40‐80 mg of furosemide intravenously) | 5‐30 min | Potassium elimination |

| Calcium (eg, 30 mL of 10% calcium gluconate or 10 mL of 10% calcium chloride intravenously) | 1‐2 min | Myocardial membrane stabilization |

Interestingly, potassium elimination is often underrepresented in therapeutic summaries (eg, by the European Resuscitation Council 5 ), and the use of furosemide could even be complemented by other diuretics (such as acetazolamide in nonacidotic patients). 24 Apart from the medication depicted in Table 1, the general use of sodium bicarbonate is controversial in nonacidotic patients, although its value is undisputed in patients with low pH levels. Finally, hemodialysis is the most effective way of potassium elimination but requires substantial clinical effort and resource management. 5 , 17 , 25 , 26 New drug developments with doubtable beneficial features in emergency situations have been introduced in the recent past: Patiromer, a synthetic polymer, exchanges calcium and potassium intestinally, therefore promoting fecal potassium excretion. Its long onset time (7‐48 hours) and effect duration (12‐24 hours) render Patiromer unpracticable for critical care, although it can be seen as an addition to the other options for long‐term potassium decrement. 12 , 27 , 28 Sodium zirconium cyclosilicate (ZS‐9), a nonabsorbable cation exchanger, is highly selective for potassium and ammonium ions and leads to fecal potassium excretion by exchange with sodium and hydrogen. This agent has a shorter onset (1‐6 hours) than Patiromer and an effect duration of 4‐12 hours. 27 , 29

Concerning fluid therapy, isotonic saline should be avoided: Its rapid infusion causes hyperchloremic acidosis due to a reduction of the strong anion gap by an excessive rise in plasma chloride as well as renal bicarbonate elimination. 30 , 31 Since acidosis leads to a shift of potassium from the intra‐ to the extracellular space through K+/H+ exchange, the administration of isotonic saline may aggravate hyperkalemia. 6 , 32

Typical complications in some of the therapeutic interventions include hypoglycemia due to insulin overdose and rebound hyperkalemia after the initial therapeutic effect has worn off; close electrolyte monitoring must be maintained at all times.. 5 , 17 , 25 , 27

2. CASE PRESENTATION

2.1. The initial scene

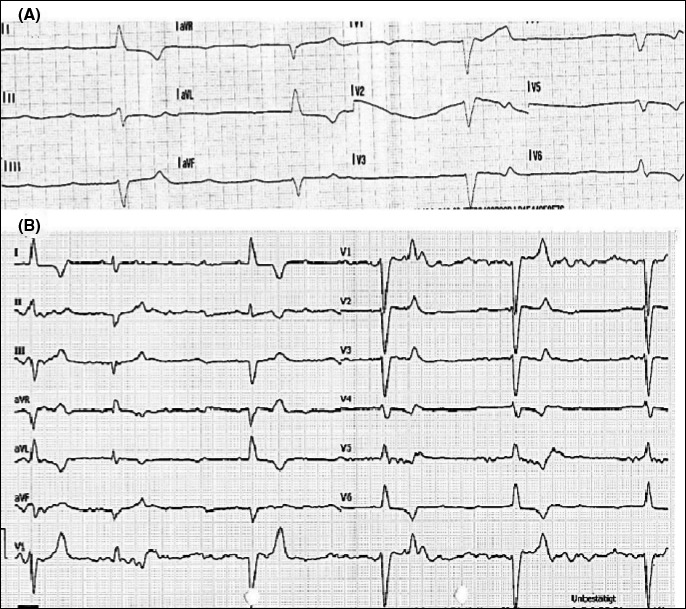

A 69‐year‐old female patient was found in her apartment, lying on the floor barely responsive (unknown when last seen well). Systematic initial evaluation by the arriving ambulance crew revealed the following: (a) airway not obstructed. (b) cyanotic, breathing rate 20/min, peripheral oxygen saturation not measurable, and vesicular breathing sounds bilaterally. (c) pale, hypotensive at 40/20mm Hg, the ECG showing a bradycardic rhythm with a left bundle branch block at a heart rate of 22 bpm (Figure 1). (d) somnolent, pupils isocoric and slowly reactive, blood sugar 330 mg/dL. (e) no injury marks, no edema, and no signs of venous congestion. Recent history: The patient had been discharged from hospital after a double coronary artery bypass graft and mitral valve reconstruction 7 days before. Relevant comorbidities were listed as coronary heart disease with a myocardial infarction 12 months ago, peripheral arterial disease, cerebral arterial disease with an ischemic stroke 4 months ago, arterial hypertension, hyperlipidemia, insulin‐dependent diabetes mellitus type 2, and chronic cholecystolithiasis; the patient was allergic to pineapples.

FIGURE 1.

A, The preclinical ECG (bradycardia, QRS with left bundle branch morphology) B, The ECG at hospital admission (third‐degree heart block)

Initial treatment of the critically ill patient consisted of oxygen at 6 liters/min, administered through a venturi mask, peripheral venous cannulation, and intraosseous cannulation. After administration of 500 mL of isotonic fluid, 0.7 mg of neosynephrine, and a drip of 1 mg of epinephrine diluted in 100 mL of 0.9% natrium chloride, the heart rate improved up to 35 bpm. No further significant clinical improvement could be noted, and the patient was transported to an Emergency Department at a tertiary university hospital.

2.2. Arrival at the Emergency Department

Upon arrival, the patient was somnolent and showed a heart rate of 29 bpm, a breathing rate of 21/min, and SpO2 of 98% at 10l oxygen insufflation; the blood pressure was not measurable. A third‐degree atrioventricular block with a bradycardic escape rhythm was diagnosed from the ECG (Figure 1). The administration of 1 mg of atropine was futile, and 1 mg of epinephrine was fractionally given with an improvement in heart rate up to 32 bpm. The initial venous blood gas showed lactate acidosis (pH 7.019, lactate 14 mEq/L), hyperkalemia (9 mEq/L), hyperglycemia (691 mg/dL), and signs of kidney injury (creatinine 2.01 mg/dL).

2.3. Stabilization and further treatment

Ten milli litre of 10% calcium gluconate was given, followed by 0.5 mg of terbutaline, 200 mL of sodium bicarbonate 8.4%, and 10 IU of short‐acting insulin. Simultaneously, a transient right ventricular pacemaker was placed through the right internal jugular vein. As a result of this treatment approach, a stable sinus rhythm at 92 bpm could be achieved. Hemodialysis was not required as potassium values were regressive.

Urine analysis showed ketone bodies (3.2 mmol/L), suspicious for ketoacidosis. As a secondary diagnosis, an erysipelas on the left calf was noted (see Table 2 for initial infection parameters) and treated with an antibiogram‐guided antibiotic regime during the following days. After 2 weeks of hospitalization, the patient was discharged without any further residues.

TABLE 2.

Initial venous blood gas analysis and special laboratory values as described in the case presentation (see text)

| Category | Value | Unit | Category | Value | Unit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 7.019 | WBC | 14.17 | G/L | ||

| pCO2 | 22.9 | mm Hg | Fibrinogen | 471 | mg/dL | |

| pO2 | 455 | mm Hg | CRP | 2.01 | mg/dL | |

| Hb | 9.5 | g/dL | CK | 101 | U/L | |

| K+ | 9.0 | meq/L | ||||

| Na+ | 123 | meq/L | ||||

| Ca++ | 1.12 | meq/L | ||||

| Cl‐ | 102 | meq/L | ||||

| Gluc | 691 | mg/dL | ||||

| Lac | 13.9 | meq/L | ||||

| Crea | 2.01 | mg/dL | ||||

Abbreviations: Ca++, calcium; Cl‐, chloride; Crea, creatinine; dL, deciliters; G, giga; g, grams; Gluc, glucose; Hb, hemoglobin; K+, potassium; L, liter; Lac, lactate; meq, milliequivalents; mm Hg, millimeters mercury; Na+, sodium; PCO2, partial pressure of carbon dioxide; pO2, partial pressure of oxygen; U, units.

2.4. Etiological workup

The following chronic medication list was acquired: bisoprolol, pantoprazole, clopidogrel, atorvastatin, spironolactone, acetylsalicylic acid, trazodone, losartan, ramipril, and insulin. Because of low‐normal potassium levels, potassium capsules had been prescribed. Ramipril was taken off the list after the presented episode.

2.5. Final diagnosis

Hemodynamic instability due to bradycardia in severe hyperkalemia (caused by a combination of acute infection and polypharmacy) was diagnosed. In addition, combined lactate acidosis and diabetic ketoacidosis, acute kidney injury (AKI), and an erysipelas as a trigger for the acute onset of the episode were present.

3. DISCUSSION

The initial diagnosis of the reported patient was delayed by the unavailability of blood gas analysis in the preclinical setting; moreover, a more thorough ECG analysis could have given hints toward hyperkalemia. In the future, preclinical blood gas analysis could lead to faster and more accurate diagnosis of electrolyte disturbances. 33

Once hospitalized, the treatment regime for hyperkalemia was conducted according to current recommendations, 5 apart from the additional early use of sodium bicarbonate. Hemodialysis was not required in the end; potassium levels were sufficiently reacting to the initial treatment regimen. The noted acidosis was most likely multifactorial, since increased potassium levels themselves can decrease proximal tubule ammonia generation and collecting duct ammonia transport, leading to impaired ammonia excretion that causes metabolic acidosis. 34 Even though tissue trauma might have been present due to the unknown time period of the patient lying on the floor unresponsive, initial CK values proved to be in normal ranges. Therefore, AKI probably resulted from hemodynamic depletion in terms of cardiorenal syndrome. 35 Although the most probable cause of hyperkalemia was a combination of acute infection and polypharmacy in this presented case, diabetic ketoacidosis might also have played a role in further aggravating the problem: In situations of low circulating insulin, potassium is released from cells. Moreover, an elevation in plasma osmolality leads to osmotic fluid movement from the intra‐ to the extracellular space, which is paralleled by further potassium release. 36 , 37

Similar cases are known, and drug‐induced hyperkalemia depicts the most common cause of increased potassium levels in everyday practice. Therefore, this potential side effect of a variety of drugs and their interactions must be considered in every patient discharged from hospital care. 1 , 12 , 38 , 39 Even if chronic medication is not changed, side effects may occur due to an additional acute stressor like surgery or an erysipelas in the hereby described case, and the early period after discharge is a most vulnerable phase. Close follow‐ups, for instance with the family physician, should strongly be suggested. 17 , 40 Even more attention should be paid to patient groups which are known to be likely to develop electrolyte disbalances and to have polypharmaceutic permanent medication, such as elderly people. Warnings have been issued about dual or triple inhibition of the RAAS 7 , 9 , 10 , 39 , 41 and an overuse of potassium‐rich dietary supplements. 42

4. CONCLUSION

Hyperkalemia is a potentially life‐threatening condition, often induced by polypharmacy. It can be prevented by sound prescription considering interactions and close attention to any add‐ons. Well‐recognized ECG features—if present—may be crucial for diagnosis. Immediate potentially life‐saving treatment, guided by clinical presentation, depends on the setting and resources.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have nothing to disclose.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTION

SS: collected data and comprised the manuscript. JN, FC, NS, and AOS: critically revised the manuscript and contributed to changes. CS, MH, and HD: critically revised the manuscript and supervised the writing process. All authors approved of the final manuscript version.

CONSENT

Written consent was obtained from the patient. However, all data have been fully anonymized.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

Schnaubelt S, Niederdoeckl J, Schoergenhofer C, et al. Hyperkalemia: A persisting risk. A case report and update on current management. Clin Case Rep. 2020;8:1748–1753. 10.1002/ccr3.2974

REFERENCES

- 1. Ben Salem C, Badreddine A, Fathallah N, et al. Drug‐induced hyperkalemia. Drug Saf. 2014;37(9):677‐692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Betts KA, Woolley JM, Mu F, et al. The prevalence of hyperkalemia in the United States. Curr Med Res Opin. 2018;34(6):971‐978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Muschart X, Boulouffe C, Jamart J, et al. A determination of the current causes of hyperkalaemia and whether they have changed over the past 25 years. Acta Clin Belg. 2014;69(4):280‐284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lee Hamm L, Hering‐Smith KS, Nakhoul NL. Acid‐base and potassium homeostasis. Semin Nephrol. 2013;33(3):257‐264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Truhlář A, Deakin CD, Soar J, et al. European resuscitation council guidelines for resuscitation 2015: section 4. Cardiac arrest in special circumstances. Resuscitation. 2015;95:148‐201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Aronson PS, Giebisch G. Effects of pH on potassium: new explanations for old observations. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(11):1981‐1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wozakowska‐Kapłon B, Janowska‐Molenda I. Iatrogenic hyperkalemia as a serious problem in therapy of cardiovascular diseases in elderly patients. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2009;119(3):141‐147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Juurlink DN, Mamdani MM, Lee DS, et al. Rates of hyperkalemia after publication of the randomized aldactone evaluation study. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(6):543‐551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Motta D, Cesano G, Pignataro A, et al. Severe hyperkalemia in patients referred to an emergency department: the role of antialdosterone drugs and of reninangiotensin system blockers. G Ital Nefrol. 2017;34(1). gin/34.1.11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Esteras R, Perez‐Gomez MV, Rodriguez‐Osorio L, et al. Combination use of medicines from two classes of renin‐angiotensin system blocking agents: risk of hyperkalemia, hypotension, and impaired renal function. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2015;6(4):166‐176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European society of cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the heart failure association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18(8):891‐975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Seferovic PM, Ponikowski P, Anker SD, et al. Clinical practice update on heart failure 2019: pharmacotherapy, procedures, devices and patient management. An expert consensus meeting report of the heart failure association of the European society of cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21(10):1169‐1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bucsa C, Moga DC, Farcas A, et al. An investigation of the concomitant use of angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors, non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs and diuretics. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2015;19(15):2938‐2944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nash DM, Markle‐Reid M, Brimble KS, et al. Nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug use and risk of acute kidney injury and hyperkalemia in older adults: a population‐based study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2019;34(7):1145‐1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Day JRS, Chaudhry AN, Hunt I, et al. Heparin‐induced hyperkalemia after cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74(5):1698‐1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Freeman K, Feldman JA, Mitchell P, et al. Effects of presentation and electrocardiogram on time to treatment of hyperkalemia. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15(3):239‐249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Berkova M, Berka Z, Topinkova E. Arrhythmias and ECG changes in life threatening hyperkalemia in older patients treated by potassium sparing drugs. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2014;158(1):84‐91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Weiss JN, Qu Z, Shivkumar K. The electrophysiology of hypo___ and hyperkalemia. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2017;10(3):e004667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Parham WA, Mehdirad AA, Biermann KM, et al. Hyperkalemia revisited. Tex Heart Inst J. 2006;33(1):40‐47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Petrov DB. Images in clinical medicine. An electrocardiographic sine wave in hyperkalemia. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(19):1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kettritz R. Hyperkalemia ‐ causes, diagnostic evaluation and treatment. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2019;144(3):180‐184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sridharan MR, Flowers NC. Hyperkalemia and Wolff‐Parkinson‐White type preexcitation syndrome. J Electrocardiol. 1986;19(2):183‐187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Soar J, Nolan JP, Böttiger BW, et al. European resuscitation council guidelines for resuscitation 2015: section 3. Adult advanced life support. Resuscitation. 2015;95:100‐147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Weisberg LS. Management of severe hyperkalemia. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(12):3246‐3251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Abuelo JG. Treatment of severe hyperkalemia: confronting 4 fallacies. Kidney Int Rep. 2018;3(1):47‐55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mushiyakh Y, Dangaria H, Qavi S, et al. Treatment and pathogenesis of acute hyperkalemia. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2011;1(4). 10.3402/jchimp.v1i4.7372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Long B, Warix JR, Koyfman A. Controversies in management of hyperkalemia. J Emerg Med. 2018;55(2):192‐205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kim ES, Deeks ED. Patiromer: a review in hyperkalaemia. Clin Drug Investig. 2016;36(8):687‐694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rafique Z, Peacock WF, LoVecchio F, et al. Sodium zirconium cyclosilicate (ZS‐9) for the treatment of hyperkalemia. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2015;16(11):1727‐1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Eisenhut M. Adverse effects of rapid isotonic saline infusion. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91(9):797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Prough DS, Bidani A. Hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis is a predictable consequence of intraoperative infusion of 0.9% saline. Anesthesiology. 1999;90(5):1247‐1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Modi MP, Vora KS, Prarikh GP, Shah VR. A comparative study of impact of infusion of Ringer’s Lactate solution versus normal saline on acid‐base balance and serum electrolytes during live related renal transplantation. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2012;23(1):135‐137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mikkelsen S, Wolsing‐Hansen J, Nybo M, et al. Implementation of the ABL‐90 blood gas analyzer in a ground‐based mobile emergency care unit. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2015;23:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Harris AN, Grimm PR, Lee H‐W, et al. Mechanism of hyperkalemia‐induced metabolic acidosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29(5):1411‐1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Di Lullo L, Bellasi A, Russo D, et al. Cardiorenal acute kidney injury: Epidemiology, presentation, causes, pathophysiology and treatment. Int J Cardiol. 2017;227:143‐150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Milionis HJ, Dimos G, Elisaf MS. Severe hyperkalaemia in association with diabetic ketoacidosis in a patient presenting with severe generalized muscle weakness. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18(1):198‐200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Park SY, Kim TJ, Kim MJ. Acute hyperkalemia induced by hyperglycemia in non‐diabetic patient. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2011;61(2):175‐176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hovland A, Fagerheim AK, Hardersen R, et al. An elderly man with known heart failure admitted with cardiogenic shock. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2010;130(13):1352‐1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Raebel MA. Hyperkalemia associated with use of angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers. Cardiovasc Ther. 2012;30(3):e156‐e166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Saito Y, Yamamoto H, Nakajima H, et al. Incidence of and risk factors for newly diagnosed hyperkalemia after hospital discharge in non‐dialysis‐dependent CKD patients treated with RAS inhibitors. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0184402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Turgutalp K, Bardak S, Helvaci I, et al. Community‐acquired hyperkalemia in elderly patients: risk factors and clinical outcomes. Ren Fail. 2016;38(9):1405‐1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ayach T, Nappo RW, Paugh‐Miller JL, et al. Life‐threatening hyperkalemia in a patient with normal renal function. Clin Kidney J. 2014;7(1):49‐52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]