Abstract

Background

Limited data exists regarding the effects of empiric antibiotic use in pediatric oncology patients with febrile neutropenia (FN) on the development of antibiotic resistance. We evaluated the impact of a change in our empiric FN guideline limiting vancomycin exposure on the development of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus in pediatric oncology patients.

Methods

Retrospective, quasi-experimental, single-center study using interrupted timeseries analysis in oncology patients aged ≤18 years with at least 1 admission for FN between 2009 and 2015. Risk strata incorporated diagnosis, chemotherapy phase, Down syndrome, septic shock, and typhlitis. Microbiologic data and inpatient antibiotic use were obtained by chart review. Segmented Poisson regression was used to compare VRE incidence and antibiotic days of therapy (DOT) before and after the intervention.

Results

We identified 285 patients with 697 FN episodes pre-intervention and 309 patients with 691 FN episodes postintervention. The proportion of high-risk episodes was similar in both periods (49% vs 48%). Empiric vancomycin DOT/1000 FN days decreased from 315 pre-intervention to 164 post-intervention (P < .01) in high-risk episodes and from 199 to 115 in standard risk episodes (P < .01). Incidence of VRE/1000 patient-days decreased significantly from 2.53 pre-intervention to 0.90 post-intervention (incidence rate ratio, 0.14; 95% confidence interval, 0.04–0.47; P = .002).

Conclusions

A FN guideline limiting empiric vancomycin exposure was associated with a decreased incidence of VRE among pediatric oncology patients. Antimicrobial stewardship interventions are feasible in immunocompromised patients and can impact antibiotic resistance.

Keywords: VRE, antibiotic stewardship, immunocompromised host, MDRO

Fever during chemotherapy-induced neutropenia, a common complication in oncology patients, is associated with increased hospital length of stay, cost, and mortality [1]. While infections are diagnosed in only 20%–30% of febrile neutropenia (FN) episodes, the high risk of morbidity and mortality necessitates prompt administration of broad-spectrum empiric antibiotics [2]. Antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) play an important role in advocating for judicious and appropriate antibiotic use. Formalized ASPs are effective at reducing antimicrobial prescribing in children [3]. There is ongoing interest in optimization of antimicrobial management in pediatric oncology patients. A survey of antimicrobial stewardship and infectious diseases clinicians and pharmacists identified priorities for ASPs in this population, including reduction in time to antimicrobial deescalation, reduction in redundant coverage, and guideline development [4]. A key area of interest is the impact of antimicrobial stewardship interventions, such as institution-specific clinical practice guidelines, on the development of antibiotic resistance.

Rates of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE) infection and colonization have increased over the past decade and are associated with increased hospital length of stay, hospitalization cost, and increased mortality [5, 6]. A recent metaanalysis in hospitalized pediatric patients reported VRE-colonized patients were almost 9 times more likely to develop a VRE infection compared with noncolonized patients [7]. VRE colonization is an important risk factor for VRE bloodstream infections in both adult and pediatric hematology/oncology and hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients, suggesting that efforts to reduce both colonization and infection are important for this vulnerable population [7, 8].

In 2012, our institution adopted a risk-stratified approach to empiric treatment for FN in which intravenous (IV) vancomycin was included as part of broader coverage in the initial empiric regimen to cover potential antibiotic-resistant pathogens in the patients at highest risk. This was followed by early deescalation in the absence of documented infection, including vancomycin discontinuation prior to neutrophil count recovery. The goal of this protocol change was to ensure appropriate empiric antibiotic coverage for the most likely and virulent pathogens while simultaneously decreasing unnecessary IV vancomycin exposure. We evaluated the impact of the change in our empiric FN guideline on the development of VRE in pediatric oncology patients.

METHODS

Study Design and Population

We performed a retrospective, quasiexperimental study of pediatric oncology patients with at least 1 episode of FN. We used Dana Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI) medical record numbers to identify potentially eligible patients aged ≤18 years admitted to Boston Children’s Hospital between January 2009 and December 2015. Fever was defined as a single oral temperature ≥38.5°C or 2 temperature readings ≥38.0°C separated by ≥1 hour in a 24-hour period. Neutropenia was defined as an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) of <500 cells/mm3 sustained for 24 hours. Patients with at least 1 admission with neutropenia within 24 hours of fever were eligible for inclusion. All admissions in which an antibiotic was administered or at least 1 positive microbiologic culture was obtained were included in our analysis. FN start was defined as neutropenia with fever ± 1 calendar day. FN recovery was defined as an ANC ≥500 regardless of fever resolution or the date of hospital discharge, whichever occurred first. Antivirals, antifungals, and inhaled antimicrobials were not recorded. Patients without an underlying oncologic diagnosis identified by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [9] code, absence of FN within the study period, or stem cell transplantation prior to the first episode of FN were excluded. Data were extracted from the electronic health record and collected using research electronic data capture tools [10].

Patients were stratified into either high-risk or standard-risk groups. High-risk patients included those with signs and symptoms of septic shock as determined by the treating provider; clinical or radiographic suspicion for neutropenic enterocolitis (typhlitis); acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) in all phases of therapy except the maintenance phase; acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) in all phases of therapy except acute promyelocytic leukemia maintenance therapy; relapsed ALL and relapsed AML in all phases of therapy; Down syndrome with any oncologic diagnosis in any phase of therapy; or advanced-stage non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), recurrent NHL, or recurrent Hodgkin disease treated with intensively myelosuppressive chemotherapy. Adjudication of intensively myelosuppressive chemotherapy was performed by a pediatric hematologist/oncologist (A. E. P.). All other patients were considered to be standard-risk. Patients in the pre-intervention period were retrospectively risk stratified.

Intervention

The risk-stratified empiric FN guideline was implemented in March 2012. The pre-intervention study period was defined as January 2009–December 2011, and the post-intervention study period was defined as January 2013–December 2015. The pre-intervention empiric regimen included ceftazidime or piperacillin-tazobactam and gentamicin in the presence of concerning abdominal symptoms. The post-intervention regimen included cefepime, with addition of metronidazole if there is concern for abdominal symptoms. Meropenem was empirically initiated in high-risk patients with hemodynamic instability with allergies to cephalosporins or anaphylactic reactions to penicillin or in AML patients receiving cefepime prophylaxis prior to development of FN. Standard-risk patients with cephalosporin/penicillin allergy were treated with aztreonam and clindamycin in the absence of suspected typhlitis and per the high-risk protocol if typhlitis was suspected.

In the pre-intervention period, empiric IV vancomycin was initiated based on the following clinical criteria, at the discretion of the treating provider: skin and soft tissue infection, recent high-dose cytarabine use, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) colonization, suspected infection with Bacillus species due to the presence of gram-positive rod in culture or via gram stain, or septic shock. In the post-intervention period, empiric IV vancomycin was initiated in all high-risk patients for 48 hours but was discontinued in the absence of a positive culture or compatible clinical syndrome requiring IV vancomycin.

Antibiotic discontinuation criteria were met in the pre-intervention period when the patient was afebrile and with an ANC ≥500. In the post-intervention period, clinically well-appearing patients who were afebrile for ≥24 hours, with negative blood cultures for ≥48 hours and an ANC >200 cells/mm3 post-nadir from chemotherapy and rising were eligible for empiric antibiotic discontinuation regardless of risk stratification. Additionally, in the post-intervention period, standard-risk patients who were well-appearing, had been afebrile for ≥24 hours with negative blood cultures for ≥48 hours, with an absolute phagocyte count >100 cells/mm3 post-nadir from chemotherapy and rising were eligible for “early” discharge with outpatient antibiotics (ciprofloxacin and amoxicillin/clavulanate) until count recovery. Patients who developed fever and neutropenia during both pre- and post-intervention periods were included in the analysis.

There were no other changes in infection prevention or antimicrobial stewardship protocols concurrent with the implementation of the revised FN guideline.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was VRE incidence, expressed as the number of admissions with any isolation of VRE (including colonization or infection) per 1000 patient (admission)-days. We chose to report VRE rates per 1000 patient-days in order to capture VRE cultures that may occur outside an FN episode. For this calculation, patients with more than 1 positive culture for VRE during the same admission were counted only once. Positive cultures were retrospectively determined to represent infection or colonization. Routine surveillance cultures were obtained for VRE on admission to any intensive care unit (ICU) and weekly thereafter during the ICU stay. We defined VRE using the National Healthcare Safety Network surveillance definition from the Multidrug-Resistant Organism & Clostridiodies difficile module, and vancomycin resistance was determined using standard susceptibility testing methods [11]. Intrinsically vancomycin-resistant organisms, including Enterococcus gallinarum, were also classified as VRE. If multiple isolates were obtained with the same susceptibility patterns from the same source, only the first isolate was recorded. Secondary outcomes included 30-day all-cause mortality.

Antibiotic Utilization

Antibiotic utilization rate was defined as antibiotic days of therapy (DOT) per 1000 FN days. Because the guidelines for vancomycin utilization applied only during FN episodes and differed by risk stratification during FN episodes, we restricted our analysis of vancomycin use to only FN episodes rather than looking at vancomycin use/1000 patient-days. Antibiotic administration data were collected retrospectively by chart review and classified by a pediatric infectious diseases–trained physician (M. V. K.) as empiric, microbiologically directed, or clinically directed therapy. Microbiologically documented antibiotics were defined as those targeted toward a specific pathogen identified by culture. Clinically directed therapy was defined as antibiotic use targeted toward a clinically or radiographically identified source of infection without microbiologic confirmation.

Protocol Adherence

In high-risk FN admissions, criteria for protocol deviation were met in the following scenarios: continuation of empiric IV vancomycin for ≥3 days or initiation of meropenem in the absence of cefepime prophylaxis or sepsis. In standard-risk admissions, criteria for protocol included initiation of empiric IV vancomycin at FN onset, continuation of empiric IV vancomycin for ≥3 days, or initiation of empiric meropenem at FN onset.

Statistical Analyses

Continuous demographic and clinical variables were compared between periods using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. χ2 tests were used to assess differences in categorical variables between periods. Antimicrobial utilization during FN episodes was reported as cumulative antibiotic days of therapy (DOT) in days per 1000 FN days by intervention period and risk. Within risk strata, total and empiric DOT per 1000 FN days between periods were compared using Poisson regression. Incidence rates of multidrug-resistant positive cultures are summarized as overall incidence rates per 1000 patient-days and infection rates (noncolonization or contaminant) per 1000 patient-days. Poisson regression was used to assess the difference in incidence rates between periods. Incidence rates of VRE are expressed per 1000 patient-days. Interrupted time-series analysis using segmented Poisson regression was used to compare VRE incidence rates pre- and post-intervention, using equal slopes to test for a shift in rate pre vs post. A model including baseline trend slope and the interaction between baseline trend and intervention period was evaluated, but neither term was significant; therefore, the equal slopes model is reported. All tests were performed at an alpha level of 0.05. Analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4; Cary, NC). The Dana Farber Cancer Institute Institutional Review Board. approved the study

RESULTS

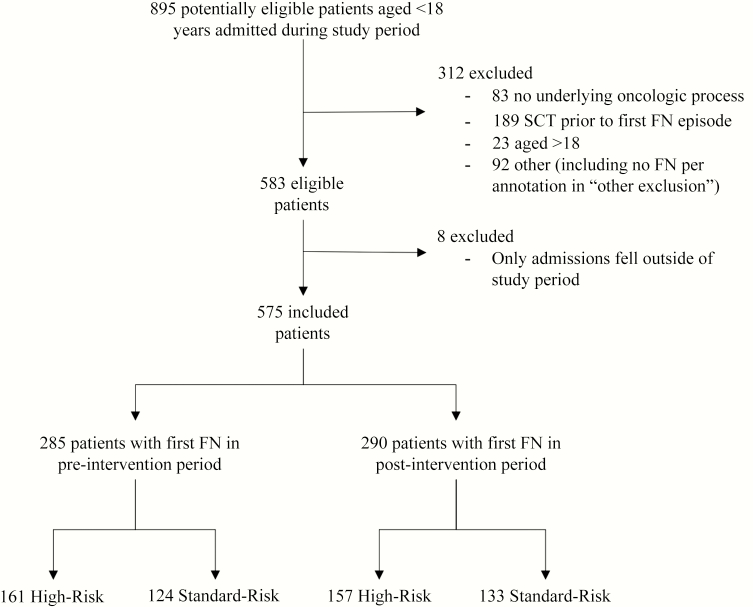

From an initial cohort of 895 potentially eligible patients aged ≤18 years admitted during the study period, 320 were excluded, resulting in a final cohort of 575 unique patients (Figure 1). Nineteen patients had FN episodes in both the pre- and post-intervention periods.

Figure 1.

Cohort assembly.

Baseline characteristics are described in Table 1. There were more patients with AML in the post-intervention period compared with the pre-intervention period, but this difference was not statistically significant. The pre-intervention period included 1410 total admissions, and 1356 were included in the post-intervention period, with no significant difference in median length of stay between study periods. Length of hospital stay during an admission with FN decreased after the intervention from a median of 7 days (interquartile range [IQR], 4, 20) to 6 days (IQR, 3, 17; P = .02).

Table 1.

Patient, Admission, and Febrile Neutropenia (FN) Episode Characteristicsa

| Characteristic | n (%) or Median (Q1, Q3) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Intervention | Post-Intervention | ||

| (2009–2011) | (2013–2015) | P Valueb | |

| Patients | n = 285 | n = 309 | |

| Age at study entry (years) | 6.2 (3.1, 12.1) | 6.4 (3.2, 12.3) | .93 |

| Female gender | 135 (47) | 133 (43) | .29 |

| Race | .59 | ||

| White | 204 (72) | 216 (70) | … |

| Black/African American | 17 (6) | 12 (4) | … |

| Asian | 14 (5) | 22 (7) | … |

| Other | 7 (2) | 9 (3) | … |

| Unknown | 43 (15) | 50 (16) | … |

| Ethnicity | .13 | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 33 (12) | 29 (9) | … |

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 203 (71) | 242 (78) | … |

| Unknown | 49 (17) | 38 (12) | … |

| Underlying oncologic diagnosis | .06 | ||

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 112 (39) | 115 (37) | … |

| Acute myelogenous leukemia | 14 (5) | 26 (8) | … |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 9 (3) | 8 (3) | … |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 15 (5) | 17 (6) | … |

| Acute promyelocytic leukemia | 8 (3) | 0 (0) | … |

| Otherc | 3 (1) | 2 (1) | … |

| Solid tumor | 124 (44) | 141 (46) | .18 |

| Central nervous system tumors | 33 (27) | 31 (22) | … |

| Neuroblastoma | 24 (20) | 31 (22) | … |

| Wilms renal tumor | 8 (7) | 6 (4) | … |

| Osteosarcoma | 16 (13) | 19 (14) | … |

| Ewing sarcoma | 4 (3) | 16 (12) | … |

| Other | 39 (31) | 38 (27) | … |

| Admissions per patient | 4 (2, 7) | 4 (2, 6) | .16 |

| Admissions with any FN episodes per patient | 2 (1, 3) | 2 (1, 3) | .30 |

| FN episodes per patient | 2 (1, 3) | 2 (1, 3) | .42 |

| Admissions | n = 1410 | n = 1356 | |

| Total patient days | 13 447 | 14 440 | … |

| Total central-line days (oncology units) | 30 982 | 36 439 | … |

| Length of stay (days) across all admissions | 4 (2, 8) | 4 (2, 8) | .63 |

| FN episode during admission | 657 (47) | 649 (48) | .51 |

| Length of stay (days) during admission with FN | 7 (4, 20) | 6 (3, 17) | .02 |

| FN episodes | n = 697 | n = 691 | |

| Total FN days | 6226 | 6273 | … |

| Episode length (days) | 6 (4, 9) | 5 (4, 9) | .20 |

| Admitting location | .71 | ||

| Oncology floor | 645 (93) | 643 (93) | … |

| Intensive care unit or Step-down unit | 52 (7) | 48 (7) | … |

Nineteen patients had FN episodes in both the pre- and post-intervention periods.

Abbreviation: FN, febrile neutropenia.

aN = 575 uniqe patients, 2766 admissions, 1388 FN episodes. Nineteen patients had FN episodes in both the pre- and post-intervention periods.

b P value from the χ2 test for categorical variables testing for difference in distribution by period; P value from the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables testing for difference in distribution by period.

cOther includes pre: 1 chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), 1 intermediate/gray zone lymphoma, 1 post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders (PTLD); and post: 1 CML, 1 PTLD.

Characteristics of FN episodes are described in Table 2. There was no difference in the proportion of FN admissions that met criteria for high risk between study periods (pre 49% vs post 48%).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Febrile Neutropenia Episodesa

| Characteristic | N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre- Intervention | Post- Intervention | ||

| (2009–2011) | (2013–2015) | P Valueb | |

| n = 697 FN Episodes | n = 691 FN Episodes | ||

| Risk classification | .91 | ||

| Standard | 357 (51) | 356 (52) | … |

| High | 340 (49) | 335 (48) | … |

| Sepsis, or septic shock | 55 (16) | 42 (13) | … |

| Neutropenic enterocolitis (typhlitis) | 8 (2) | 7 (2) | … |

| ALL in all phases except continuation | 223 (66) | 201 (60) | … |

| AML in all phases except maintenance | 47 (14) | 53 (16) | … |

| Relapsed AML, ALL in any phase of therapy | 45 (13) | 60 (18) | … |

| Down syndrome | 16 (5) | 12 (4) | … |

| Lymphoma: advanced-stage NHL, recurrent NHL, or recurrent Hodgkin disease with intensively myelosuppressive chemotherapy | 37 (11) | 48 (14) | … |

| Infection during episode | .02 | ||

| No infection | 499 (72) | 532 (77) | … |

| Infection | 198 (28) | 159 (23) | … |

| Clinically suspected | 93 (47) | 82 (52) | .58 |

| Microbiologically documented | 92 (46) | 66 (42) | … |

| Both clinically and microbiologically documented | 13 (7) | 11 (7) | … |

| Infection typec | … | ||

| Bacteremia | 63 (32) | 41 (26) | … |

| Skin/soft tissue | 55 (28) | 36 (23) | … |

| Other | 23 (12) | 23 (14) | … |

| Clostridiodies difficile infection | 22 (11) | 29 (18) | … |

| Community-acquired pneumonia | 19 (10) | 16 (10) | … |

| Urinary tract infection | 7 (4) | 3 (2) | … |

| Typhlitis | 5 (3) | 5 (3) | … |

| Pharyngitis | 3 (1) | 2 (1) | … |

| Otitis media | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | … |

| Ventilator-associated pneumonia | 0 (0) | 3 (2) | … |

| Sinusitis | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | … |

| Osteomyelitis | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | … |

| Multiple infections | 74 (37) | 75 (47) | … |

Abbreviations: ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML, acute myelogenous leukemia; FN, febrile, neutropenia; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

aN = 1388 episodes.

b P value from the χ2 test for categorical variables testing for difference in distribution by period.

cNot mutually exclusive.

Infections During FN Episodes

Infections were identified in 198/679 (28%) of FN episodes in the pre-intervention period and in 159/691 (23%) of FN episodes in the post-intervention period. Characteristics of clinically suspected and microbiologically documented infections are described in Table 2. Bacteremia was the most common infection.

Descriptions of positive Enterococcus cultures obtained across all admissions are given in Table 3. Positive VRE cultures were obtained in 34 unique patients across 47 admissions (pre, 24 patients with 34 admissions; post, 10 patients with 13 admissions). Ten patients had more than 1 admission with a positive VRE culture (8 patients had 2 admissions, 1 patient had 3 admissions, and 1 patient had 4 admissions with positive VRE).

Table 3.

Description of Enterococcus Isolates Across All Admissionsa

| Organism and source | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Pre- Intervention | Post- Intervention | |

| (2009–2011) | (2013–2015) | |

| n = 1410 Admissions | n = 1356 Admissions | |

| Total Enterococcus isolates across admissions | 57 (4) | 38 (3) |

| Total VRE isolates | 42 (3) | 14 (1) |

| Enterococcal isolates | n = 57 | N = 38 |

| Infection | 15 (26) | 4 (11) |

| Colonization | 42 (74) | 34 (89) |

| Species | ||

| Enterococcus avium | 0 (0) | 1 (3) |

| VRE isolates | n/a | 0 (0) |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 6 (11) | 11 (26) |

| VRE isolates | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Enterococcus faecium | 44 (77) | 17 (45) |

| VRE isolates | 41 (93) | 12 (70) |

| Enterococcus gallinarum | 0 (0) | 1 (3) |

| VRE isolates | n/a | 1 (100) |

| Enterococcus not identified | 7 (12) | 8 (21) |

| VRE isolates | 1 (14) | 1 (13) |

| Source | ||

| Blood | 18 (32) | 12 (32) |

| VRE isolates | 9 (50) | 1 (8) |

| Urine | 10 (18) | 8 (21) |

| VRE isolates | 5 (50) | 1 (13) |

| Tissue | 0 (0) | 2 (5) |

| VRE isolates | n/a | 0 (0) |

| Wound | 2 (4) | 0 (0) |

| VRE isolates | 1 (50) | n/a |

| Fluid | 1 (2) | 7 () |

| VRE isolates | 1 (100) | 3 (43) |

| Abscess | 3 (5) | 0 (0) |

| VRE isolates | 3 (100) | n/a |

| Stool | 22 (39) | 9 (24) |

| VRE isolates | 22 (100) | 9 (100) |

| Otherb | 1 (12) | 5 (13) |

| VRE isolates | 1 (100) | n/a |

Abbreviation: VRE, vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus.

aN = 2766 admissions.

bCentral venous line tip.

Incidence of VRE

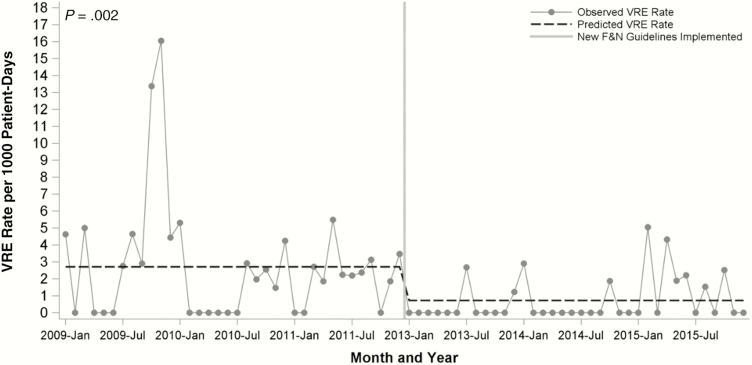

Incidence of VRE is provided in Table 4. After restricting our analysis to 1 VRE isolate per patient per admission, there were 34 admissions with any positive cultures pre-intervention and 13 post-intervention. In an interrupted time-series model using segmented Poisson regression, there was no interaction between time and period, and VRE incidence decreased from 2.53 to 0.90 per 1000 patient-days (incidence rate ratio, 0.14; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.04–0.47; P = .002; Figure 2).

Table 4.

Incidence of Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcusa

| Pre- Intervention | Post-Intervention | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| (2009–2011) | (2013–2015) | ||

| Data Elements | n = 1410 Admissions | n = 1356 Admissions | P Valueb |

| Total patient days | 13 447 | 14 440 | |

| Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus | |||

| Admissions with positive cultures, n | 34 | 13 | |

| Incidencec per 1000 patient-days | 2.53 | 0.90 | .002 |

| Infection, n (%) | 12 (35) | 4 (31) | |

| Infection incidenced per 1000 patient-days | 0.89 | 0.28 | .03 |

aN = 2766 admissions.

b P value from Poisson regression testing for difference in incidence per 1000 patient-days by period.

cIncidence includes both vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE) colonization and infection.

dInfection incidence includes only VRE infection.

Figure 2.

Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus rates by intervention period from interrupted time-series regression model.

Notably, the incidence of VRE colonization/infection in other nononcology hospital units did not change during the study period (0.51/1000 patient-days pre-intervention vs 0.53/1000 patient days post-intervention).

To assess whether patients who developed VRE had greater vancomycin exposure, we evaluated the association between vancomycin DOT and VRE incidence (at an individual patient level). For each 1-day increase in total vancomycin exposure (FN + non-FN), the odds of VRE increased by 1% (infection plus colonization: odds ratio [OR], 1.01; 95% CI, 1.00, 1.02; P = .04; infection only: OR, 1.01; 95% CI, 1.00, 1.02; P = .13). When we limited this analysis to total vancomycin exposure during an FN episode, each 1-day increase in vancomycin exposure increased the odds of VRE infection + colonization by 4% (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.01, 1.06; P = .002) and increased the odds of VRE infection by 3% (OR, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.00, 1.06; P = .03). Similarly, for each 1-day increase in empiric vancomycin exposure during FN episodes, the odds of VRE infection + colonization increased by 4% (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.01, 1.08; P = .004) and the odds of VRE infection also increased by 4% (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.00, 1.08; P = .03).

Thirty-day all-cause mortality was low and did not differ pre- and post-intervention (pre, n = 9 [3%] vs post, n = 8 [4%], P = .68).

FN Guideline Adherence

Among episodes that would have met criteria for standard risk, 84% (301/357) would have been classified as adherent to the protocol in the pre- intervention period compared with 91% adherent (324/356) in the post-intervention period (P = .007). The majority of episodes that deviated from the protocol in the post-intervention period were for empiric IV vancomycin duration longer than 3 days or for initiating empiric IV vancomycin at episode start. Among episodes that would have met criteria for high risk, 64% (217/340) would have been classified as adherent to the protocol in the pre-intervention period compared with 74% adherent (247/335) in the post-period (P = .006). The majority of deviations were due to continuing empiric IV vancomycin longer than 3 days.

Antimicrobial Utilization

Antimicrobial utilization during FN is described in Table 5. Overall antimicrobial DOT/1000 FN episode-days for high-risk patients decreased significantly (pre, 2297 vs post, 1758; P < .001). Overall empiric DOT/1000 FN days for high-risk patients also decreased significantly (pre,1388 vs post, 973; P < .001). There were no significant differences in DOT among standard-risk patients before and after the intervention.

Table 5.

Antimicrobial Utilization During Febrile Neutropenia Admissionsa

| High-Risk (n = 675 FN Admissions) | Standard-Risk (n = 713 FN Admissions) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre- Intervention | Post- Intervention | Pre- Intervention | Post- Intervention | |||

| (2009–2011) | (2013–2015) | (2009–2011) | (2013–2015) | |||

| Antimicrobial data elements | n = 340 | n = 335 | P Valueb,c | n = 357 | n = 356 | P Valueb,c |

| Total FN days | 4251 | 4497 | – | 1975 | 1776 | – |

| Total DOT (all antibiotics) per 1000 FN daysb | 2296.6 | 1758.1 | <.001 | 2940.8 | 2931.9 | .87 |

| Total DOT (all nonprophylaxis) per 1000 FN daysb | 1922.1 | 1424.5 | <.001 | 2176.2 | 2207.2 | .52 |

| Total empiric DOT (all antibiotics) per 1000 FN daysb | 1388.4 | 972.9 | <.001 | 1475.9 | 1554.1 | .05 |

| Intravenous vancomycin | ||||||

| Any use, n (%)c | 178 (52) | 250 (75) | <.001 | 112 (31) | 85 (24) | .03 |

| Total DOT/1000 FN daysb | 435.0 | 295.8 | <.001 | 324.6 | 224.1 | <.001 |

| Empiric use, n (%)c | 139 (41) | 228 (68) | <.001 | 69 (19) | 61 (17) | .45 |

| Empiric DOT/1000 FN daysb | 315.2 | 199.2 | <.001 | 164.6 | 115.4 | <.001 |

| Oral vancomycin | ||||||

| Any use, n (%)c | 5 (1) | 8 (2) | .39 | 9 (3) | 7 (2) | .62 |

| Total DOT/1000 FN daysb | 56.2 | 34.9 | <.001 | 64.8 | 60.8 | .63 |

| Empiric use, n (%)c | 0 (0) | 1 (<1) | .50 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Empiric DOT/1000 FN daysb | 0 | 2 | .99 | 0 | 0 | – |

| Third- and fourth-generation cephalosporinsd | ||||||

| Any use, n (%)c | 268 (79) | 240 (72) | .03 | 288 (81) | 324 (91) | <.001 |

| Total DOT/1000 FN daysb | 699.6 | 516.3 | <.001 | 730.1 | 948.2 | <.001 |

| Empiric use, n (%)c | 256 (75) | 221 (66) | .008 | 280 (78) | 312 (88) | .001 |

| Empiric DOT/1000 FN daysb | 623.9 | 437.8 | <.001 | 678 | 1108.7 | <.001 |

| Anaerobic agentse | ||||||

| Any use, n (%)c | 109 (32) | 123 (37) | .20 | 78 (22) | 81 (23) | .77 |

| Total DOT/1000 FN daysb | 304.6 | 401.4 | <.001 | 283.5 | 283.8 | .99 |

| Empiric use, n (%)c | 90 (26) | 101 (30) | .29 | 65 (18) | 58 (16) | .50 |

| Empiric DOT/1000 FN daysb | 196.7 | 263.3 | <.001 | 177.2 | 145.3 | .02 |

Abbreviations: DOT, antibiotic days of therapy; FN, febrile neutropenia

aN = 1388 admissions.

b P value from Poisson regression testing for difference in DOT per 1000 episode-days by period within risk category.

c P value from χ2 test to test for difference in antibiotic use by period within risk category for any use (%) and empiric use (%).

dIncludes ceftriaxone, ceftazidime, and cefepime.

eIncludes metronidazole, piperacillin/tazobactam, and meropenem.

Overall IV vancomycin use in our cohort during both FN and non-FN admissions decreased significantly (pre, 311.1 DOT/1000 patient days; post, 166.6 DOT/1000 patient days; P < .001). Empiric IV vancomycin use also decreased (pre, 217 DOT/1000 patient days; post, 101 DOT /1000 patient days; P < .001).

While more high-risk patients in the post-intervention period received empiric IV vancomycin (250/335, 75%) compared with the pre-intervention period (178/340, 52%), overall median days of IV vancomycin decreased significantly in both high-risk and standard-risk groups. Median empiric IV vancomycin days within an FN episode also decreased significantly in both high-risk and standard-risk groups. There were no significant differences noted in the utilization of anaerobic agents pre- and post-intervention across both high-risk and standard-risk groups.

Levofloxacin prophylaxis was not used in the pre-intervention period and was reported 49 times, representing approximately 4% of all admissions in the post-intervention period.

DISCUSSION

We demonstrated that implementation of an empiric risk-stratified FN guideline aimed at reducing IV vancomycin exposure in pediatric oncology patients resulted in decreased IV vancomycin utilization and was associated with decreased incidence of VRE colonization and infection.

Limited data exist on the role of empiric IV vancomycin initiation for FN in pediatric patients. Two metaanalyses that evaluated the benefits of empiric glycopeptide initiation in adult oncology patients found no significant difference in all-cause or infection-related mortality [12, 13]. However, the authors concluded that there may be a subset of FN patients with specific risk factors who might benefit. Extrapolating from adult literature, current guidelines for FN in pediatric oncology patients recommend limiting empiric glycopeptide initiation to patients who are clinically unstable, in whom a resistant pathogen is suspected, or to centers with high rates of resistant pathogens [2, 14]. In our study, nearly two-thirds of gram-positive organisms and 90% of Bacillus spp. isolates during FN episodes were obtained in patients categorized as high-risk, highlighting that risk stratification may identify a subgroup of patients who might benefit from initial empiric IV vancomycin therapy.

Implementation of our stewardship intervention was associated with a statistically significant decrease in the incidence of VRE infection and colonization. We found that for a 1-day increase in vancomycin DOT, the odds of VRE colonization or infection increased by 3%–4%, suggesting that reduction in VRE after implementation of the revised F&N protocol was driven by the reduction in vancomycin exposure during FN episodes. Preventing the development of antibiotic resistance is a critically important goal of antimicrobial stewardship interventions [15]. To date, few studies have demonstrated a positive impact of antimicrobial stewardship interventions on the development of antibiotic resistance in pediatric patients. In a prospective, single-center study, Di Pentima et al described the impact of an antimicrobial stewardship program on vancomycin use and MRSA and VRE infections over a 3-year period in pediatric patients and noted a reduction in VRE infections from 10 to 2 cases per year, although overall rates of Enterococcus infection remained low [16]. Despite significant heterogeneity between studies, a recent metaanalysis of hospitalized adult patients, including both immunocompromised and nonimmunocompromised populations, found that ASP interventions were associated with decreases in the rates of multidrug-resistant pathogens and C. difficile infection, although the impact on VRE was not significant [17].

Although a larger percentage of patients received empiric IV vancomycin in the post-intervention period, we demonstrated a sustained and significant reduction in total and empiric IV vancomycin DOT as well as duration of empiric therapy in both high- and standard-risk patients after guideline implementation. Exposure to IV vancomycin has been described as a risk factor for the development of VRE colonization and infection [13, 16, 18]. In addition to IV vancomycin, third-generation cephalosporins, carbapenems, and clindamycin have all been shown to be associated with development of VRE [8, 18, 19]. In our study, cephalosporin use decreased significantly in the high-risk population, which also may have impacted our results. Regardless, our revised guideline was associated with significant reductions in overall antimicrobial days of therapy, suggesting that identification of patients in whom therapy can be deescalated sooner is a feasible antimicrobial stewardship strategy for FN.

Our study has several limitations. Because the data are from a single, large, quaternary, freestanding children’s hospital, the results may not be generalizable to other settings. Although we were able to demonstrate an impact from our intervention on rates of Enterococcus infections, the incidence of other resistant bacteria was too low to draw meaningful conclusions. While rates of 30-day mortality did not vary between the pre- and post-intervention periods, our study was likely underpowered to detect a difference in mortality. Routine surveillance for VRE and MRSA colonization was only conducted in ICUs during both time periods, so colonization in patients not admitted to the ICU may have been missed.

There is growing recognition of the need for antimicrobial stewardship in immunocompromised pediatric patients. Our study adds to the limited published evidence that demonstrates that reduction of IV vancomycin exposure in pediatric oncology patients is associated with decreased incidence of VRE. Antimicrobial stewardship interventions can limit unnecessary antimicrobial exposure in immunocompromised patients and can impact the development of antimicrobial resistance.

Notes

Disclaimer. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Harvard Catalyst, Harvard University and its affiliated academic healthcare centers, or the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Financial support. This work was supported by the NIH (grant T32HD05514 to M. W.); the Program for Patient Safety and Quality at Boston Children’s Hospital (institutional grant to M. V. K.); and by Harvard Catalyst | The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health award UL 1TR002541) as well as financial contributions from Harvard University and its affiliated academic healthcare centers.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Kuderer NM, Dale DC, Crawford J, et al. Mortality, morbidity, and cost associated with febrile neutropenia in adult cancer patients. Cancer 2006; 106:2258–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Freifeld AG, Bow EJ, Sepkowitz KA, et al. ; Infectious Diseases Society of America Clinical practice guideline for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52:e56–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hersh AL, De Lurgio SA, Thurm C, et al. Antimicrobial stewardship programs in freestanding children’s hospitals. Pediatrics 2015; 135:33–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wolf J, Sun Y, Tang L, et al. ; Pediatric Hematology/Oncology Antimicrobial Stewardship Interest Group Antimicrobial stewardship barriers and goals in pediatric oncology and bone marrow transplantation: a survey of antimicrobial stewardship practitioners. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2016; 37:343–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Adams DJ, Eberly MD, Goudie A, Nylund CM. Rising vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus infections in hospitalized children in the United States. Hosp Pediatr 2016; 6:404–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Prematunge C, MacDougall C, Johnstone J, et al. VRE and VSE bacteremia outcomes in the era of effective VRE therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. ICHE 2016; 6:404–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Flokas ME, Karageorgos SA, Detsis M, et al. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci colonisation, risk factors and risk for infection among hospitalised paediatric patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2017; 49:565–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ford CD, Lopansri BK, Haydoura S, et al. Frequency, risk factors, and outcomes of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus colonization and infection in patients with newly diagnosed acute leukemia: different patterns in patients with acute myelogenous and acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2015; 36:47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Icd-9-cm: International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification. Salt Lake City, Utah: Medicode; 1996 Print. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009; 42:377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Multidrug-Resistant Organism & Clostridium difficile Infection (MDRO/CDI) Module 7–8. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/PDFs/pscManual/12pscMDRO_CDADcurrent.pdf. Accessed August 21 2018.

- 12. Paul M, Borok S, Fraser A, et al. Empirical antibiotics against gram-positive infections for febrile neutropenia: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Antimicrob Chemother 2005; 55:436–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vardakas KZ, Samonis G, Chrysanthopoulou SA, et al. Role of glycopeptides as part of initial empirical treatment of febrile neutropenic patients: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet Infect Dis 2005; 5:431–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lehrnbecher T, Phillips R, Alexander S, et al. ; International Pediatric Fever and Neutropenia Guideline Panel Guideline for the management of fever and neutropenia in children with cancer and/or undergoing hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30:4427–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Core Elements of Hospital Antibiotic Stewardship Programs. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2014. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/getsmart/healthcare/ implementation/core-elements.html. Accessed August 21 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Di Pentima MC, Chan S. Impact of antimicrobial stewardship program on vancomycin use in a pediatric teaching hospital. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2010; 29:707–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Baur D, Gladstone BP, Burkert F, et al. Effect of antibiotic stewardship on the incidence of infection and colonisation with antibiotic-resistant bacteria and Clostridium difficile infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2017; 17:990–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fridkin SK, Edwards JR, Courval JM, et al. ; Intensive Care Antimicrobial Resistance Epidemiology Project and the National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System Hospitals The effect of vancomycin and third-generation cephalosporins on prevalence of vancomycin-resistant enterococci in 126 U.S. adult intensive care units. Ann Intern Med 2001; 135:175–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ghanem G, Hachem R, Jiang Y, et al. Outcomes for and risk factors associated with vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium bacteremia in cancer patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2007; 28:1054–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]