Abstract

Objectives

Community health workers (CHWs) are a critical part of the healthcare workforce and valuable members of healthcare teams. However, little is known about successful strategies for sustaining CHW programs. The aim of this study is to identify institutional and community factors that may contribute to the sustainability of CHW programs to improve maternal health outcomes.

Methods

We conducted focus groups and in-depth interviews with 54 CHWs, CHW program staff, and community partners involved in implementing three Merck for Mothers-funded CHW programs in the United States serving reproductive-age women with chronic health conditions. Additionally, a review of documents submitted by CHW programs during the evaluation process provided context for our findings. Data were analyzed using an inductive qualitative approach.

Results

Three themes emerged in our analysis of factors that may influence the sustainability of CHW programs to improve maternal health: CHW support from supervisors, providers, and peers; relationships with healthcare systems and insurers; and securing adequate, continuous funding. Key findings include the need for CHWs to have strong supervisory structures, participate in regular care team meetings, and interact with peers; advantages of CHWs having access to electronic health records; and importance of full-cost accounting and developing a broad base of financial support for CHW programs.

Conclusion

Research should continue to identify best practices for implementation of such programs, particularly regarding effective supervisory support structures, integration of programs with healthcare systems, and long-term revenue streams.

Keywords: lay health advisors/community health workers, maternal health, chronic disease, healthcare disparity/health disparities, qualitative methods

Introduction

A growing body of literature demonstrates the effectiveness of community health worker (CHW) programs in helping individuals with chronic health conditions achieve and maintain better health.1 Defined by the American Public Health Association as “a frontline public health worker who is a trusted member of and/or has an unusually close understanding of the community served”,2 CHWs often serve as a liaison between the community and the healthcare system, improving community member access to care and identifying and addressing social determinants of health. More specifically, CHWs are non-licensed providers who perform several roles, including cultural mediation (ie, healthcare and social service system navigation); counseling and social support (ie, coaching and support group facilitation); health education (health promotion and chronic disease prevention and management); advocacy (ie, translation and mediation); outreach (referral and follow up); capacity building (ie, individual and community empowerment); and provision of direct services (ie, basic needs and clinical services).3

Yet sustaining CHW programs is challenging in the United States (US), largely due to short-term program funding.4,5 The Affordable Care Act recognizes CHWs as important members of the healthcare work force and, as of January 2014, Medicaid can reimburse for CHW services, if recommended by a physician or other Medicaid-enrolled licensed practitioner.6 However, lack of awareness of and guidance on legislation related to reimbursement of CHW services may hinder organizations’ ability to sustain CHW programs.7 Moreover, new policies and policy changes being pursued by the current US Administration, such as reducing funding for prevention and public health, may decrease incentives for community health programs.8 Evaluating the role CHWs play in producing positive health behavior change and health outcomes can help encourage sustained investment in CHW programs.9-11 However, positive program evaluations do not guarantee sustainability.12

In 2015, Merck for Mothers, Merck’s $500 million global initiative to address maternal mortality,13 funded three organizations in New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania to address growing numbers of pregnant women with chronic conditions such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease, which may contribute to the rise in maternal mortality and morbidity.14,15 Two organizations were community-based organizations and one was a Medicaid accountable care organization. Each CHW program model was developed in collaboration with local stakeholders to ensure it would best meet needs of the women (pregnant and postpartum women or medically and socially complex women of reproductive age, all with chronic health conditions) in the community it intended to serve and healthcare system of which it was a part. Specific services CHWs provided were tailored to each client’s needs. Across program models, CHW roles included helping clients navigate the healthcare system, conducting health education and outreach, providing information and referrals for social services, assisting with scheduling appointments, delivering appointment reminders, and attending appointments with clients. CHWs also worked with clients to develop care management plans and track progress toward their health goals. Many were doulas (trained, nonmedical birth coaches) and supported clients during labor and birth.

Findings from our evaluation of these Merck for Mothers-funded programs16 indicate that CHWs are valuable members of maternal healthcare teams with potential to contribute to advancement of the Triple Aim for maternity care: improved health, improved care, and reduced costs.17 For example, relative to a comparison group, women enrolled in the program implemented in Pennsylvania were more likely to experience improved prenatal and postnatal care engagement and reduced antenatal inpatient admissions, and their infants were more likely to experience shorter neonatal intensive care unit stays.17 Despite such improvements, sustainability remains a concern, with only two of the three programs that were assessed maintaining implementation beyond the initial funding period.

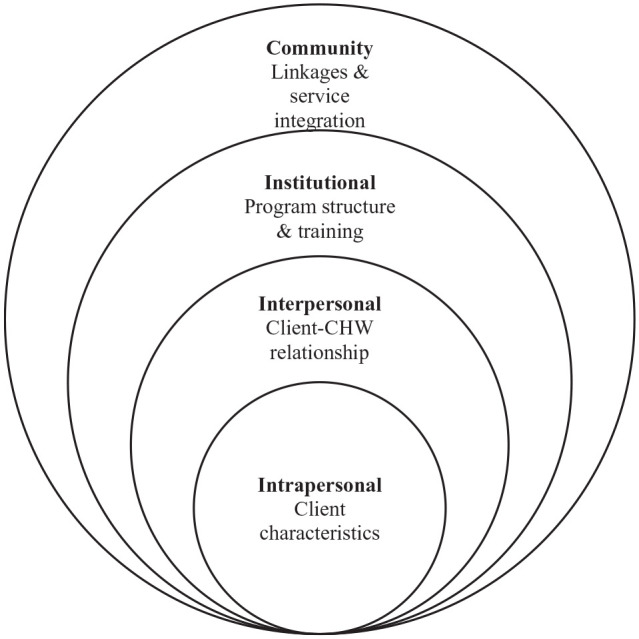

Drawing on a socioecological framework,18 Figure 1 shows the multiple levels of context that may influence the success and long-term viability of CHW programs including intrapersonal (client characteristics), interpersonal (client-CHW relationship), institutional (program structure and training), and community (linkages and service integration) factors. Our evaluation solicited stakeholder perspectives at all levels of the framework on the implementation, impact, and sustainability of each CHW program. The aim of this study is to identify institutional and community factors that may contribute to the sustainability of CHW programs to improve maternal health outcomes.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework for multi-level factors that may influence the sustainability of community health worker (CHW) programs to improve maternal health outcomes.

Methods

This qualitative study is part of a larger evaluation of three Merck for Mothers-funded CHW programs. Clients, CHWs, CHW program staff, and community partners (ie, representatives of health systems partnering with CHW programs and members of other partnering organizations such as behavioral health organizations) participated in the evaluation. This study uses data from participants not including clients. All CHWs and program staff affiliated with the CHW programs were eligible and were invited by evaluation staff to participate. Community partners were invited by CHWs and CHW program staff to participate. Participants had no prior relationship with or knowledge about the evaluation team. Interested CHWs, CHW program staff, and community partners provided written informed consent prior to participation. No participants withdrew from the evaluation.

Focus groups and individual in-person semi-structured interviews were conducted at each program site using focus group/interview guides developed by the evaluation team. Only participants and the evaluation team were present at the focus groups/interviews. Examples of questions in the focus group/interview guides are shown in Table 1. Topics included challenges, successes, and lessons learned regarding implementation, impact, and sustainability of each program. Upon completion of focus groups and interviews, participants were compensated with a $20 gift card, and descriptive field notes were written. Focus groups and interviews were recorded and transcribed by the evaluation team. Transcripts were not returned to participants for comment.

Table 1.

Sample Questions on Semi-Structured Focus Group/Interview Guides for Community Health Workers (CHWs), CHW Program Staff, and Community Partners.

| Stakeholder | Topic | Question |

|---|---|---|

| CHW | Training | • What parts of your training have been the most helpful to you in providing care? |

| Client interactions | • Tell me about a time when you felt that your help was useful. | |

| Programmatic support & healthcare institutions | • When you need professional support in your CHW role, how do you get it? • Tell me about how you fit in with other members of the healthcare team. |

|

| Personal & professional life | • Do you see yourself continuing to work as a CHW? • What do you think are the weaknesses/strengths of the CHW program? |

|

| CHW program staff | Training | • Tell me what the training for CHWs looks like? |

| Program implementation | • Tell me about how your organization came to implement this particular CHW model. • What have been some challenges/successes of the CHW program? |

|

| Program sustainability | • What are some lessons you have learned in trying to sustain the program over time? | |

| Community partner | Training | • How do you think CHWs should be trained? |

| Program implementation | • What do you think of the program? What are its strengths? Weaknesses? • Do you have recommendations to improve the program? |

Data for this study came from 18 CHWs, 15 CHW program staff, and 21 community partners who participated in 9 focus groups and 5 in-depth interviews (whichever was convenient to the participant) conducted between May and October, 2017 (Table 2). Duration of focus groups/interviews was 60 min on average. Data also came from a sample of documents (n = 18) submitted by CHW program staff during the evaluation process, including initial reports, progress reports, and grant submissions (Table 2). Evaluation documents provided detailed programmatic data and narratives that supplemented the focus groups and interviews. We used focus group/interview and evaluation document data to increase legitimation of data interpretation through triangulation.19 Furthermore, the relevance of codes in grounded theory research can be established if a code is repeatedly present across data sources.20

Table 2.

Number of Focus Groups/Interviews and Participants and Evaluation Documents Across Community Health Worker (CHW) Programs.

| CHW Program | Focus groups and interviews |

Evaluation documents |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of focus groups (number of participants) | Number of interviews (number of participants) |

Total number of participants | Initial report | Progress reports | Grant submissions | Others | Total number of documents | |

| Program A | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 6 | |||

| CHW | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 4 | |||||

| CHW program staff | 1 (6) | 31 (3)2 | 7 | |||||

| Community partner | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | 7 | |||||

| Program B | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | |||

| CHW | 13 (7) | 0 (0) | 1 | |||||

| CHW program staff | 0 (0) | 6 | ||||||

| Community partner | 2(5) | 5 | ||||||

| Program C | 1 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 9 | |||

| CHWs and doulas4 | 2 (13) | 0 (0) | 13 | |||||

| CHW program staff | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 2 | |||||

| Community partner | 1 (9) | 0 (0) | 9 | |||||

| Total | 9 (51) | 5 (5) | 54 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 18 |

Follow-up interviews.

Two CHW program staff in Program A who participated in the focus group also participated in the follow-up interviews.

The CHW participated in the CHW program staff focus group.

In Program C, doulas (trained, nonmedical birth coaches) were different from CHWs; in other programs, CHWs could provide doula services.

Initially, focus group and interview data were analyzed using a grounded-theory informed inductive coding approach to identify key themes.21 Two authors (RM, LB) trained in qualitative research methods, iteratively single (one person codes a transcript)- and double-coded (two people independently code the same transcript) samples of the focus group and interview transcripts using a preliminary code book based on the structure and content of the focus group/interview guide. Coders met to refine and modify codes, derived from the focus group/interview guide and the data, for clarity and completeness. Consensus was reached through discussion. The same two authors single-coded all transcripts using the final codebook. Data saturation was achieved. Data were coded using Dedoose (version 8.0.35, SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC, Los Angeles, California, 2018). Subsequently, RM reviewed evaluation documents to contextualize excerpts from the focus group/interview data and to provide more detailed excerpts based on codes from the final codebook. We sought feedback from CHW program staff on data interpretation. All study procedures were approved by the Yale University Institutional Review Boards (Human Subjects Committee, reference number 2000020587).

Description of Authors’ Backgrounds

The authors are females with doctoral degrees who are trained in qualitative research methods, have expertise in maternal health research, and are affiliated with a school of public health. RM (doctoral candidate at the time of the focus groups/interviews) and LB (postdoctoral fellow/associate research scientist) conducted the focus groups/interviews and coded the focus group/interview data. JL was a doctoral candidate/associate research scientist and SC was a research scientist. The authors have extensive experience conducting community-based participatory research in urban, low-income communities of color which may have influenced the interpretation of the data.

Results

Three themes emerged in our analysis of factors that may influence the sustainability of CHW programs to improve maternal health: CHW support from supervisors, providers, and peers; relationships with healthcare system and insurers; and securing adequate, continuous funding.

CHW Support from Supervisors, Providers, and Peers

Healthcare organizations must comprehensively support their CHW workforce. All three CHW programs provided comprehensive initial training and continued training. However, trainings can be logistically difficult to arrange and expensive to provide. One CHW program was able to cost-effectively meet ongoing training needs by virtue of being a Medicaid accountable care organization and utilizing their own physicians and behavioral health specialists (rather than paying external organizations) to provide regular, targeted trainings to CHWs on topics relevant to clients. CHWs reported that shadowing a more experienced CHW was also a valuable part of CHW training.

Many CHWs highlighted the need for program administrators to fully appreciate the demands of the job. In the words of one CHW, “So, to sum it up, we couldn’t do what we really do if it wasn’t for our director that understands the workload that we have.” (CHW 1, Program C). CHW program staff supported CHWs by conducting frequent meetings to address CHW concerns. As shared by CHW program staff, “The director really works hard on providing adequate support to the staff and helping with complicated cases so that no one really feels like they’re on their own in a situation.” (CHW Program Staff 1, Program A). Community partners likewise expressed the importance of providing a strong supervisory structure for CHWs:

CHWs going into the home of a high-risk population. To really provide a structure where there is some type of supervision or support for them. . . having a one supervisor to five caseworkers ratio, some kind of a structured ratio. . . where there’s time for them to really work together on how are you handling and managing your cases. (Community Partner 1, Program C)

CHW participation in routine care team meetings helped to ensure that they had the support they needed from providers and vice versa. As stated in a grant renewal:

[The CHW program] created a new, systematic approach and level of trust between the hospital-based prenatal clinic and obstetrical services, the Medicaid managed care insurer and the community-based service provider. Introducing the [CHW program] in the [clinic] led the prenatal clinic to revive a multi-disciplinary care review meeting to discuss patients’ cases. Each week doctors and the care team review scheduled patients, and a [CHW] provides real-time updates on those enrolled as [CHW program] clients and their progress outside of the clinic. The [CHW] then joins the Nurse Practitioners’ meeting in the clinic in a similar fashion. These weekly meetings have become accepted and anticipated as critical communication channels for [CHW program] staff and the healthcare providers. These interactions are a consistent thread given turnover in providers, as well as an opportunity for the providers to better understand and better serve their patients. (Grant renewal, Program A)

CHWs also described the importance of receiving emotional and informational support from peers. As a CHW, who was trained as a doula, stated, “One thing that I need is an opportunity to share my experience among like-minded doulas. To talk about it, whether it’s good or bad. . . just to share it and discuss it with somebody who will understand because they’ve met [it] in some form or fashion.” (CHW 2, Program C). Another CHW expressed, “I do need. . . everyone needs to know that all the craziness is for a good cause and that there’s a good outcome. . . We wanna know that we can vent, we can say things that we may not be able to say to our departments.” (CHW 3, Program C).

Formal Relationship between CHW Program and Healthcare System and Insurers

The two CHW programs that maintained implementation beyond the initial funding period were part of or had a formal relationship with a healthcare system that enabled CHWs to have access to electronic health records (EHR). These programs identified and recruited clients through review of EHR, face-to-face meetings in the clinic, and clinic referrals. Conversely, it was more difficult for the CHW program that did not have a formal relationship with a healthcare system to identify potential clients:

Not being in a clinical setting is a major challenge of the program. Therefore, we have to work very hard to cultivate relationships with clinical providers so that they refer women to our program. Still doctors are not likely to make those referrals. It is the social workers and other patient advocates, and community health workers that often connect women to us. (Initial report, Program C)

Having access to clients’ EHR also facilitated CHWs ability to assist clients in attending appointments. As CHW program staff described, “There’s a lot of value to us having access. And one of the practical applications to that is that we can help our clients get to their appointments because we can see when they are.” (CHW Program Staff 2, Program A).

Through access to clients’ charts, these programs also bridged communication between clients and providers/hospitals. In the words of one CHW program staff member, “Integration with health records and all that, gives us capacity to give [hospitals] timely feedback on their patients. So, our value added is very immediate and visible.” (CHW Program Staff 3, Program A). Other CHW program staff described how CHWs interfaced with providers by providing client narratives to providers/hospitals and implementing provider recommendations with clients:

And I think, the [obstetricians] especially, rotate through their clinic so they are not establishing relationships with people. Sometimes it almost feels helpless a little. . . And we really can provide a narrative to what is going on with this person. And I think that that helps provide context for those providers. And. . . they can give us recommendations for. . . health goals and how to achieve. . . those things. And we can be like alright we are going to take those into the community. . . If we want this person to work on nutrition and diet, we are going to create a plan with this person that is. . . realistic for them. And we are going to continue working and we are going to report back to you. We submit our goal plans into their charts so that the providers can look that up and they can see, alright, how it all fits. And we do charting now into the charts so that when they are looking at someone’s chart, they can see we are connected. (CHW program staff 2, Program A)

One CHW program also benefitted from having a direct relationship with a large Medicaid insurer. CHWs were able to facilitate the provision of important instrumental support such as health information and resources to clients. As stated in a grant renewal:

[The insurer’s] care managers perform outreach over the telephone and struggle to reach their members to provide them with resources such as pregnancy tips, nutrition information, and childbirth classes. However, members change phones or screen calls and are often hesitant to talk to their insurer. Members don’t realize the insurer is offering them resources such as breast pumps and baby items. [CHWs] were able to share this information with clients and encourage them to answer the call or even facilitate a three-way call with their care manager. [CHWs] began holding monthly calls with the care managers, sharing information on clients and their challenges. [CHWs] also have direct phone conversations with care managers as needed. (Grant renewal, Program A)

Securing Adequate, Continuous Funding

CHW programs have the potential to provide a significant return of investment. As CHW program staff expressed:

Look at the full value of what that program could look like. And think about the full cost. It is not an add on. It’s not a person that brings someone to appointments. It’s a part of the care team that makes care better. And. . . that’s bigger (CHW Program Staff 3, Program A).

However, CHW retention relies upon paying a competitive salary for this demanding position:

Other programs and local organizations, including [the Department of Health (DOH)], pay their CHWs $40,000 per annum. [The CHW program] would like to offer a more competitive salary to our CHWs in order to retain them. The two CHWs who left us, did so to work for an organization and the DOH paid them a higher rate to work as a CHW. . . Also, our clients are not easy and our CHWs work tirelessly on their behalf. (Progress report, Program C)

[CHW’s] work is really hard. . . yes, we’re all passionate about this, but that doesn’t pay the bills. . .You can’t pay rent with passion. . . you lose good people because of salaries. (Community Partner 2, Program C)

Moreover, it is essential to do a full cost accounting including expenses associated with comprehensive, ongoing training, adequate supervision, and true integration of CHWs into existing systems, as highlighted by CHW program staff:

One thing. . . both the insurers do not recognize is that this does take a tremendous amount of training and coordination. So, people think, ‘Oh, I’m going to buy a community health worker.’ And that means, I’m going to pay somebody $30,000 and they’re going to take care of all of this. And they are not thinking about all the training, supervision, this massive coordination. . . When you invest in all of those things, it makes a big difference. We can really help the individuals and the providers, and the systems be much more effective and responsive. (CHW Program Staff 4, Program A)

Gaps in funding can lead to issues with staff recruitment and retention and delays in program implementation. For example, one CHW program lost its director and assistant director due to a gap in funding between the planning year and implementation year (Progress report, Program C). Furthermore, as reported by a CHW, identifying and applying for funding sources is time-consuming, reducing capacity for supervising CHWs.

CHW program sustainability relies on funding from other sources. As CHW program staff shared, “Payers really care about this population [pregnant women]. That’s the next frontier, getting [managed care organizations (MCOs)] to help pay for this work.” (CHW Program Staff 1, Program B). Moreover, insurers and hospitals/clinics can reduce inefficiencies in workflows around first prenatal and postpartum visits, and unnecessary or expensive outpatient and inpatient services, by financially supporting CHW programs. As CHW program staff stated:

And truly I think for sustainability you need to have that payer to have that skin in the game and you also need that hospital really paying in. . . If the bill is going to the hospitals, they are going to be needing programs like ours to bring their costs down, like the stay in the [neonatal intensive care unit], [emergency room] visits, etc. (CHW Program Staff 3, Program A)

However, CHW program staff noted there is still work to be done to increase understanding of the CHW role:

I can’t tell you how many managed care companies are very interested in community health workers to go find the people they can’t find. And I have said to them, ‘Hire a detective agency.’ Because really our value is the relationship that we have with the client. (CHW Program Staff 5, Program A)

Developing partnerships with healthcare insurers can help offset program costs. For example, one CHW program entered a contractual arrangement with a Medicaid MCO for a flat reimbursement per trimester, however, this arrangement did not cover all program costs (Progress report, Program A). Relationship building with MCOs took a number of years and restructuring and leadership changes at MCOs could stall contractual negotiations. The transition from Medicaid managed care contracts to value-based payment contracts is a positive future development (Grant renewal, Program A).

A broader funding agenda that involves federal and state agencies is also necessary. As CHW program staff stated, “On the national level, we have talked about collective impact going together to [Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services]. And I thought that’s going to be really important because if the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare told the states ‘pay attention to this’ then they would be more likely to do it.” (CHW Program Staff 4, Program A).

Discussion

This study adds to the literature by identifying specific themes–CHW support from supervisors, providers, and peers; relationships with healthcare system and insurers; and securing adequate, continuous funding–that require attention when developing sustainable CHW programs aimed at improving maternal health. Our findings highlight the need for CHWs to have strong supervisory structures, participate in regular care team meetings, and interact with peers. They suggest numerous advantages of CHWs having access to EHR including facilitating referrals, CHWs ability to help clients adhere to appointments, and bidirectional communication between CHWs and other care team members. The findings also demonstrate the importance of program budgets to account for all expenses associated with sustained implementation and to develop a broad base of financial support.

Our findings pertaining to CHW support are consistent with previous studies of CHW programs to address chronic diseases and population health,10,22 and nationally recognized essential skills for CHWs, namely being trained and supported in a full range of roles across all levels of the socioecological model, and receiving sufficient and appropriate supervision.23 States are proceeding with CHW certification efforts to standardize the CHW workforce, and training or certification requirements are becoming more important hiring criteria for CHWs and may enhance opportunities for reimbursement.5,24 Certification and training may create barriers for entry into the profession, although allowing experience to substitute for training requirements and offering assistance to offset tuition may reduce these barriers.24,25

Our findings are also consistent with previous recommendations to fund CHW programs to become integrated into healthcare systems.22 For example, Delaware Health and Social Services and Delaware Center for Health Innovation concluded, “An important way to achieve CHW integration in the healthcare system, sustainability, and job security for CHWs is to maximize funding through third-party reimbursement, including Medicaid and other payors. A reimbursement system will require CHWs to be trained and credentialed. In addition to being qualified to have their services reimbursed, trained CHWs may be entrusted to add notes to patient health records, giving clinicians information about the overall environmental factors contributing to the social determinants of their health relative to what is needed in an effective, comprehensive treatment plan.”26

Although grants and other investments are useful to support CHW programs in their early stages, one or more long-term revenue streams are needed to obtain financial sustainability.9 Long-term revenue streams may take multiple forms, including fee-for-service, per-capita payment, or pay-for-performance. However, healthcare payment models are shifting from fee-for-service to value-based reimbursement models and funding models for CHWs should be similar to other health professionals who are integrated into clinical care teams.9,27

Limitations and Strengths

The three Merck for Mothers-funded CHW programs evaluated specifically focus on pregnant, postpartum, and reproductive-age women with chronic conditions in three Northeastern US cities, thus findings may not be transferable to other populations or settings. Strengths of the evaluation include data saturation from the recruitment of numerous stakeholders across multiple levels of the socioecological model and triangulation across stakeholders and data sources (ie, focus groups/interviews and evaluation documents). The recruitment of accessible stakeholders may reduce representativeness,19 although the large number of participants from different sociological levels may have minimized this potential limitation.28 We did not identify new themes emerging from the evaluation documents. Rather, these data were used to contextualize excerpts from the focus group/interview data. Demographic characteristics of the participants were not available. Transcripts were not returned to participants for comment, although we sought feedback from CHW program staff on data interpretation. Nonetheless, our findings advance understanding of the myriad of factors important for long-term CHW program viability.

Conclusions

Rising rates of maternal morbidity and mortality and challenges to existing healthcare legislation make this an important moment to consider how to build and sustain CHW programs aimed at improving maternal health. Our policy recommendations include establishing regular CHW team meetings, facilitating access to EHR, and providing long-term funding to fully support CHW programs and adequately reimburse CHW services. Research should continue to identify best practices for implementation of such programs, particularly regarding effective supervisory support structures, integration of programs with healthcare systems, and long-term revenue streams.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the community health workers (CHWs), CHW program staff, and community partners who participated in this study.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The activities in this publication were supported by funding from Merck, through its Merck for Mothers program. Merck had no role in the design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in writing of the article; or in the decision to submit the article for publication. The content of this publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of Merck. Merck for Mothers is known as MSD for Mothers outside the United States and Canada.

R. Mehra’s work was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (grant number TL1TR001864); Institution for Social and Policy Studies, Yale University; and the Herman Fellowship, Yale School of Public Health. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NIH.

ORCID iD: Renee Mehra  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9794-2971

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9794-2971

References

- 1. Rosenthal EL, Brownstein JN, Rush CH, et al. Community health workers: part of the solution. Health Affair. 2010;29:1338-1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. American Public Health Association. Support for Community Health Workers to Increase Health Access and to Reduce Health Inequities. Policy Statement No. 20091, 2009. https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2014/07/09/14/19/support-for-community-health-workers-to-increase-health-access-and-to-reduce-health-inequities.

- 3. Rosenthal EL, Wiggins N, Brownstein JN, Johnson S, Rael R. The Final Report of the National Community Health Advisor Study: Weaving the Future. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona; 1998. https://crh.arizona.edu/sites/default/files/pdf/publications/CAHsummaryALL.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alvillar M, Quinlan J, Rush CH, Dudley DJ. Recommendations for developing and sustaining community health workers. J Health Care Poor U. 2011;22:745-750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Malcarney M-B, Pittman P, Quigley L, Horton K, Seiler N. The changing roles of community health workers. Health Serv Res. 2017;52(suppl 1):360-382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Update on Preventive Services Initiatives, 2013. https://www.medicaid.gov/Federal-Policy-Guidance/Downloads/CIB-11-27-2013-Prevention.pdf.

- 7. Allen C, Brownstein JN, Mirambeau A, Jayapaul-Philip B. Technical assistance guide for states implementing community health worker strategies. CDC National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention; 2014. https://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/programs/spha/docs/1305_ta_guide_chws.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Artiga S, Hinton E. Beyond Health Care: The Role of Social Determinants in Promoting Health and Health Equity, 2018. https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/beyond-health-care-the-role-of-social-determinants-in-promoting-health-and-health-equity/.

- 9. Singh P, Honoré P, Kangovi S, et al. Closing the gap: applying global lessons toward sustainable community health models in the U.S. The Arnhold Institute for Global Health, Icahn School of Medicine, Office of the UN Secretary-General’s Special Envoy for Health in Agenda 2030 and for Malaria; 2016. http://www.healthenvoy.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Closing-the-Gap-Applying-Global-Lessons-Toward-Sustainable-Community-Health-Models-in-the-U.S..pdf.

- 10. Perry HB, Zulliger R, Rogers MM. Community health workers in low-, middle-, and high-income countries: an overview of their history, recent evolution, and current effectiveness. Annu Rev Publ Health. 2014;35:399-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Trump LJ, Mendenhall TJ. Community health workers in diabetes care: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Fam Syst Health. 2017;35:320-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rosenthal EL. Building Blocks: Community Health Worker Evaluation Case Studies. In: Community Health Worker Evaluation Tool Kit. The University of Arizona Rural Health Office and College of Public Health; 1998. https://www.betterevaluation.org/en/resources/tools/develop_logic_model/chw_evaluation_toolkit [Google Scholar]

- 13. Merck for Mothers. Merck for Mothers website. https://www.merckformothers.com.

- 14. Nelson DB, Moniz MH, Davis MM. Population-level factors associated with maternal mortality in the United States, 1997-2012. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Building US Capacity to Review and Prevent Maternal Deaths. Report from Nine Maternal Mortality Review Committees, 2018. http://reviewtoaction.org/Report_from_Nine_MMRCs.

- 16. Cunningham SD, Riis V, Line L, et al. Safe Start community health worker program: a multisector partnership to improve perinatal outcomes among low-income pregnant women with chronic health conditions. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(6):836-839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Affair. 2008;27:759-769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bronfenbrenner U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge, UK: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Onwuegbuzie AJ, Leech NL. Validity and qualitative research: an oxymoron? Qual Quant. 2007;41:233-249. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Corbin JM, Strauss A. Grounded theory research: procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qual Sociol. 1990;13:3-21. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Corbin A, Strauss J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing a Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brownstein JN, Bone LR, Dennison CR, Hill MN, Kim MT, Levine DM. Community health workers as interventionists in the prevention and control of heart disease and stroke. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29(5 suppl 1):128-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rosenthal EL, Rush CH, Allen CG. Understanding scope and competencies: a contemporary look at the United States community health worker field. Progress Report of the Community Health Worker (CHW) Core Consensus (C3) Project: Building National Concensus on CHW Core Roles, Skills, and Qualities, 2016 https://www.healthreform.ct.gov/ohri/lib/ohri/work_groups/chw/chw_c3_report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Goodwin K, Tobler L. Community health workers: expanding the scope of the healthcare delivery system, 2008. http://www.ncsl.org/print/health/chwbrief.pdf.

- 25. Bovbjerg RB, Ester L, Ormond BA, Anderson T, Richardson R. Opportunities for community health workers in the era of health reform, 2013. http://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/alfresco/publication-pdfs/4130.

- 26. Delaware Health and Social Services Division of Public Health, Delaware Center for Health Innovation. Development and deployment of community health workers in Delaware. Establishing a certification program and reimbursement mechanism. Delaware Health and Social Services, Division of Public Health, Delaware Center for Health Innovation, Health Management Associates; 2017. https://dhss.delaware.gov/dhss/dph/hsm/files/dechwreport.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 27. Alvisurez J, Clopper B, Felix C, Gibson C, Harpe J. Funding community health workers: best practices and the way forward, 2013. http://www.healthreform.ct.gov/ohri/lib/ohri/sim/care_delivery_work_group/funding_chw_best_practices.pdf.

- 28. Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]