Abstract

The reaction N2O + C2H2 → oxadiazole has been considered as a prototype for 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions. Here, we report a comprehensive dynamical study of this important reaction on a full-dimensional potential energy surface, which is fitted to about 64 000 high-level ab initio data by a machine learning approach. Comprehensive dynamical simulations are carried out to provide quantitative chemical insight into its reaction dynamics. In addition to confirming the enhancement effect of the N2O bending mode on the reactivity, intricate mode specificity effects of other vibrational modes in reactants are revealed for the first time. The asymmetric stretching mode of N2O and the C–C–H bending mode of C2H2 show no effect. All remaining modes can enhance the reactivity. In particular, the vibrational excitation of the N2O symmetric stretching mode shows similar enhancement effect on the title reaction, compared to its bending mode excitation. Detailed analysis reveals that the concerted mechanism dominates with the reactants propelled sufficiently close to each other to yield product. This study advances our understanding of the chemical dynamics of the title reaction.

1. Introduction

The reaction between nitrous oxide (N2O) and acetylene (C2H2) to form oxadiazole (C2H2N2O) is an important prototype and a proving ground for understanding the 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition,1−5 which is a powerful and efficient tool for introducing heterocycles in organic/material/biology chemistry.6−8 Many 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions have been classified as “click reactions”.9 In contrast to the stepwise mechanism with a diradical intermediate,10 most experimental and theoretical investigations concluded that 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions often take place via a concerted way without an intermediate,1−3,11 although exceptions do exist.12−15 The reactivity, regioselectivity, and substituent effects of these 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions have been studied extensively.2,3,16−21 Recently, Houk and co-workers found that the excitation of the dipolar bending mode (N2O for the title reaction) can promote the reactivity significantly based on direct dynamical calculations.22,23 They concluded that the N2O bending mode must be excited to make the reaction possible.22,23 Their discoveries24,25 suggest that dynamical effects are important in organic reactions.14,26−35

Due to the expensive electronic structure calculations and complicated potential energy surfaces (PESs) with many degrees of freedom, Houk and co-workers generated only a small number of trajectories (64–128) with electronic energies and forces computed at the level of B3LYP/6–31G(d) for the title reaction.22,23 In addition, initial coordinates and momenta were sampled at the transition state (TS) region according to a normal mode sampling with only the zero-point vibrational energy (ZPE) in each normal mode, 0.6 kcal mol–1 in the reaction coordinate, and zero rotational energy.22,23 It has been argued that this sampling does not correspond to realistic situations.23 Further, as it started from TS, the impact parameters cannot be sampled. Nonetheless, these rare dynamical studies of organic reactions provide valuable information about the mechanism and kinetics/dynamics.32 However, quantitative information is still lacking, in particular, due to the challenge in developing a reliable PES, which inhibits our full understanding of its dynamics. Herein, we report a comprehensive investigation of dynamics of the title reaction on an accurate full-dimensional PES, which is fitted by the permutation invariant polynomial-neural network (PIP-NN) method36−38 based on ca. 64 000 points calculated at the explicitly correlated (F12a) version of CCSD(T) with the augmented correlation-corrected valence double zeta (AVDZ) basis set.39,40 Detailed theoretical methods are given in the next section (Section 2), including ab initio calculations, potential energy surface, and QCT calculations. Section 3 presents the results and discussions. Conclusions are given in Section 4.

2. Theory

2.1. Ab Initio Calculations

The title reaction N2O + C2H2 → oxadiazole concerts with a cyclic transition state (TS), as shown in Figure 1. The geometries of all stationary points were first optimized at the levels of CCSD(T)-F12a/AVnZ, n = D, T. CCSD(T)-F12 converges faster with respect to the size of the basis set39,40 than the standard CCSD(T) calculations. Therefore, it can be employed to develop full-dimensional accurate PESs effectively.41 All ab initio calculations were carried out using the MOLPRO 2015.1 program package in the current work.42,43 The inner orbitals of the nonhydrogen atoms (C, N, O) were kept frozen in the CCSD(T) calculations. For each single-point energy calculation with four cores, it takes about 10–30 min using the Intel Xeon CPU E5–2680 v3 @ 2.50 GHz.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the title reaction. The energies (in kcal mol–1) correspond to PIP-NN PES and CCSD(T)-F12a/AVDZ from top to bottom. Geometries (distances in Å and angles in °) of the stationary points are also shown.

2.2. Potential Energy Surface

All dynamically

relevant regions should be well described by the PES. Following our

previous strategy,36,44−48 the ranges of configurations and energies were first

inspected. Then, different grids with appropriate coordinates were

used in different regions to sample dynamically relevant configurations.

Notice that changes in the intramolecular coordinates result in significant

energy changes. Therefore, dense grids should be used for intramolecular

coordinates of N2O and C2H2 (the

reactant region), and all internal coordinates of the TS and product

regions. On the other hand, the intermolecular coordinates between

the two species in the reactant region were sampled with relatively

sparse grids. Further, direct dynamical calculations at a low level

of theory, e.g., B3LYP/6–31+G(d), were performed

to sample additional relevant points if they are not close to the

point that already existed in the data set according to the generalized

Euclidean distance,  defined in terms of the internuclear distances

between two points,

defined in terms of the internuclear distances

between two points,  and

and  . All permutationally equivalent points

(2!2!2! = 8) were included in such screenings. Finally, roughly 15 000

points were selected as the initial set of points.

. All permutationally equivalent points

(2!2!2! = 8) were included in such screenings. Finally, roughly 15 000

points were selected as the initial set of points.

Then, the initial set of points was computed at a selected ab initio level, and a raw PES was obtained by fitting. Starting from various initial conditions, trajectory calculations were carried out on this PES to further explore the configuration space and to generate new points. The above generalized Euclidean distance was used for efficient sampling. Further, if key properties of the system, including geometries, frequencies, and energies of the stationary points, as well as the minimum energy path (MEP) were not reproduced well by the PES, points were added in relevant regions. The procedure was repeated, and the PES was improved gradually until convergence.

These sampled ab initio points were then used to fit the PES according to the permutation invariant polynomial-neural network (PIP-NN) form,36−38

| 1 |

where I denotes the size

of the input layer; J and K stand

for the sizes of the neurons of the two hidden layers, respectively;

for the two hidden layers, the hyperbolic tangent function is used

as the transfer function; ωj,i(l), the weighting

parameter, connects the ith neuron of (l – 1)th layer and the jth neuron of the lth layer; bj is

the bias parameter of the jth neurons of the lth layer; and Efit is the fitted

potential energy. Fitting parameters ω and b were determined by optimal fitting of NN with the root-mean-square

deviation (RMSD) as the performance function:  .

.

In this work, all 456 PIPs49−51 (I = 456) with the maximum order of 3 were used as the input layer of the NN. These PIPs are symmetrized monomials of Morse-like variables of internuclear distances, G = ŜΠi<jNpij, pij = exp(−λrij) (λ = 1.05 Å–1, i, j = 1–7 and i ≠ j). The symmetrization operator, Ŝ, contains all of the permutations among like atoms49−51 and guarantees the rigorous permutation invariance with respect to the exchange of like atoms in the PIP-NN approach. This approach has succeeded in fitting accurate PESs for many polyatomic reactions with up to 7 atoms, for instance, OH + CH452 and F/Cl + CH3OH.44,48

For each NN fitting, the entire data were divided randomly into three data sets, i.e., the training (90%), validation (5%), and test (5%) sets. The learning of each NN was halted when errors of the validating set started to increase. Only fits with similar RMSDs for three sets were adopted. The maximum deviation was also a criterion for choosing the final PIP-NN PES. We tested several NN structures with different numbers of neurons in the two hidden layers. For each structure, 100–200 different NN training calculations were carried out with different initial fitting parameters, and different training, validation, and test sets. The PES can be obtained from the authors upon request.

2.3. Quasi-Classical Trajectory Calculations

The VENUS program53 was used for the

full-dimensional QCT calculations. At the collision energies of 40,

50, and 60 kcal mol–1, the initial vibrational states

of the reactants included the ground state (v = 0),

excitations in the reactant vibrational states, the bending mode (vb(N2O) = 1, 5), the symmetric stretching

mode (vss(N2O) = 1), the asymmetric

stretching mode (vas(N2O) =

1) of N2O, the C–C–H bending mode (vb(C2H2) = 1), and the

H–C–C–H wagging mode (vw(C2H2) = 1, 5) of C2H2. The initial rotational energies of both reactants were zero.

For each initial condition, 1.5–9 × 105 trajectories

were calculated to make the statistical errors all less than 2.7%.

The standard error was estimated by  .

.

The QCT method has been discussed extensively in the literature,54,55 so only a brief outline is given here. The reactive integral cross-section (ICS) of the title reaction was computed by

| 2 |

where the reaction probability Pr(Ec) at the collision energy Ec is given by Pr(Ec) = Nr/Ntotal, with Nr and Ntotal being the number of the reactive or the total trajectories, respectively.

For each trajectory, the impact parameter b was sampled according to b = bmaxζ1/2, where ζ is a random number ranging from 0.0 to 1.0, and the maximal impact parameter (bmax) was determined using small batches (104) of trajectories with trial values. The trajectories were initiated at a separation of 8.0 Å and terminated when reactants were separated by 8.2 Å. These initial and termination criteria are sufficiently long so that the interactions between reactants are negligible.

For cycloaddition reactions, the trajectories were halted when the distances of the two forming bond distances C–N and C–O arrived at 1.6 Å, which were similar to those used in a previous direct dynamical study by Houk and co-workers.23 In addition, the title reaction generally takes place in a solution. The solvent can randomize the energy quickly and thus stabilize the product. Therefore, it is reasonably assumed that the product would not bounce back again to the reactant side. As shown in Figure 2, the potential energies along with the MEP in some solvents, which are treated by the widely used polarizable continuum model (PCM),56 are very close to the one by the CCSD(T)-F12/AVDZ calculation in the gas phase.

Figure 2.

Potential profile of the MEP on the PIP-NN PES as a function of the reaction coordinate s (amu1/2bohr). The symbols represent the ab initio energies at the CCSD(T)-F12a/AVDZ level. For comparison, the potential diagram of this reaction in various solvents at the level of B3LYP/6–31+G(d,p) is plotted in this figure.

Other scattering parameters such as the spatial orientation of the initial reactants and vibrational phases were determined according to the Monte Carlo approach as implemented in VENUS.53 The propagation time step was selected to be 0.05 fs, which is much smaller than that used in the direct dynamic calculations (1 fs).23 The gradient of the PES with respect to atomic coordinates was calculated numerically. The combined fourth-order Runge–Kutta and sixth-order Adams–Moulton algorithms are used for the integration of the trajectories. Almost all trajectories conserve energy within a chosen criterion (10–4 kcal mol–1).

It should be noted that the zero-point vibrational energies (ZPEs) of the reactants are included at the reactant asymptote. However, the QCT treatment allows leakage of ZPE during the reaction process. The final product energies are much higher than their ZPEs for this exothermic cycloaddition reaction. Furthermore, the tunneling effect, which might play significant roles at low energies/temperatures, is not considered within the QCT framework. It is thus highly desirable to perform exact quantum dynamic computation, which is, however, very difficult for the current system with seven atoms, namely, fifteen degrees of freedom. Fortunately, QCT computations often yield qualitative and even quantitative results, compared to the quantum dynamical calculated outcome57−59 and available experiments.60 In addition, the simulations were computed at high collision energies, 40, 50, 60 kcal mol–1, in this work. Therefore, the trajectory is very fast, which typically finished within 200 fs. Consequently, for short-time QCTs at high collision energies, it is reasonably assumed that the tunneling effect is irrelevant and the contributions of ZPE-violating trajectories during the evolution process are minimal.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Ab Initio Calculations

As shown in Figure 1 and Table 1, the structural parameters and harmonic frequencies at the CCSD(T)-F12a/AVDZ and CCSD(T)-F12a/AVTZ levels are almost identical. In general, the B3LYP/6–31G(d) calculated geometric parameters by Lan et al.61 are consistent with the current high-level calculations, with deviations being 0.05 and 0.04 Å for the two forming bonds at TS, respectively. The activation energies are 25.1 (26.3, ZPE corrected) and 27.1 (28.1) kcal mol–1 at levels of CCSD(T)-F12a/AVDZ and CCSD(T)-F12a/AVTZ, respectively. The reaction energies are −44.5 (−39.6) and −42.3 (−37.7) kcal mol–1 at AVDZ and AVTZ, respectively. Both are comparable to previous ZPE corrected CBS-QB3 values, 27.9 and −37.1 kcal mol–1.22,61 A 2 kcal mol–1 deviation for the activation energy at the level of CCSD(T)-F12a/AVDZ, compared to that of CCSD(T)-F12a/AVTZ, is neglected compared to the high barrier, 25.1 kcal mol–1, and should have no effect on the dynamics and reactivity. As a compromise between efficiency and calculation cost, CCSD(T)-F12a/AVDZ was selected for developing the PES of the title reaction.

Table 1. Energies (kcal mol–1) and Vibrational Harmonic Frequencies (cm–1) of the Stationary Points Along with the Reaction N2O + C2H2 → Oxadiazole.

| frequencies

(cm–1) |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| species | method | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| N2O + C2H2 (0; 0; 0) | PESa | 582 | 582 | 1291 | 2272 | 572 | 572 | 729 | 729 | 2004 | 3403 | 3498 | ||||

| AVDZb | 584 | 584 | 1295 | 2276 | 552 | 552 | 730 | 730 | 2001 | 3401 | 3493 | |||||

| AVTZc | 600 | 600 | 1301 | 2284 | 616 | 616 | 752 | 752 | 2005 | 3408 | 3501 | |||||

| oxadiazole (−44.54; −44.49; −42.26) | PESa | 584 | 611 | 686 | 781 | 833 | 942 | 967 | 1085 | 1131 | 1147 | 1356 | 1427 | 1547 | 3280 | 3303 |

| AVDZb | 608 | 615 | 679 | 765 | 797 | 938 | 966 | 1091 | 1132 | 1142 | 1356 | 1423 | 1543 | 3279 | 3302 | |

| AVTZc | 595 | 632 | 680 | 733 | 781 | 942 | 972 | 1093 | 1135 | 1143 | 1360 | 1429 | 1548 | 3283 | 3306 | |

| TS (25.00; 25.05; 27.14) | PESa | 585i | 267 | 283 | 486 | 587 | 632 | 704 | 711 | 731 | 820 | 1285 | 1807 | 1890 | 3372 | 3437 |

| AVDZb | 593i | 281 | 298 | 482 | 566 | 593 | 705 | 706 | 730 | 809 | 1289 | 1815 | 1898 | 3367 | 3436 | |

| AVTZc | 606i | 285 | 305 | 495 | 559 | 619 | 717 | 718 | 761 | 824 | 1265 | 1819 | 1912 | 3372 | 3443 | |

This work, fitted PIP-NN PES.

This work, CCSD(T)-F12a/AVDZ.

This work, CCSD(T)-F12a/AVTZ.

3.2. Potential Energy Surface

The PIP-NN fitting approach is employed to fit the PES base on ca. 64 000 points at the level of CCSD(T)-F12a/AVDZ. After several testing, 20 and 80 neurons were selected in the two hidden layers, respectively. The final PES has a total of 10 901 parameters, making the evaluation of the PIP-NN slow. The RMSDs for the training/validation/test/total sets are 0.33/0.59/0.61/0.37 kcal mol–1, respectively. Note these 64 000 points correspond to 512 000 points because of the permutation invariances with respect to the identical atoms, namely, the two carbon/hydrogen/nitrogen (2!2!2!) atoms in the title system. Thanks to the ultraflexible PIP-NN approach with rigorous permutation invariance among like atoms, energies, geometries (Figure 1), and harmonic frequencies (Table 1) of the stationary points are well reproduced. As shown in Figure 2, the potential energy along with the MEP on the PES is also in excellent agreement with the ab initio calculations. Initially, reactant species C2H2 and N2O (both linear) are parallel to each other. Along with the MEP, they approach each other with the bond angles HCC′, H′C′C of C2H2, and the angle NN′O of N2O bent gradually from the linear configuration. As shown in Figure 3a,b, small fitting errors (most less than 0.07 kcal mol–1) are evenly distributed within the entire energy range up to 100 kcal mol–1, which is sufficient for high energy or temperature dynamic studies.

Figure 3.

(a) Fitting errors (Efit – Etarget, in kcal mol–1) for the PIP-NN PES as a function of the ab initio energy up to 100.0 kcal mol–1 and (b) distributions of the unsigned fitting errors for the fitted points.

Figure 4 presents a two-dimensional (2-D) contour plot (with other coordinates relaxed) of the PIP-NN PES as a function of the approaching distance R and the N2O bending angle θ, whose definitions are also shown in the same figure. The reactants, TS, and the product are clearly shown in this figure. The title cycloaddition reaction has a tight and high reaction barrier, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 4.

Contour plot of the title reaction on the PIP-NN PES (energy in kcal mol–1) as a function of R and θ, where R is the distance from the central N atom to the midpoint of the C–C bond, θ is the bending angle of NN′O. All other coordinates are relaxed. Three trajectories are shown by solid lines. The gray (short dot) line, extracted from ref (22), is a direct dynamical trajectory starting from the TS (adapted in part with permission from John Wiley and Sons).

3.3. Dynamics

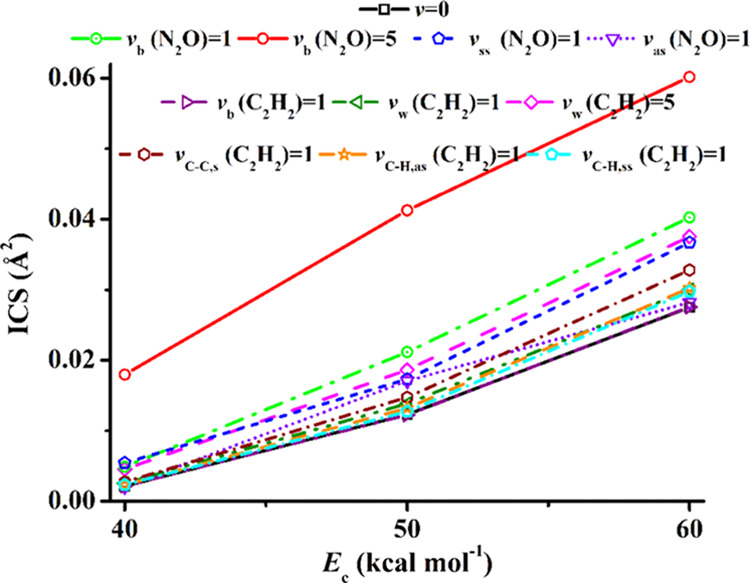

Comprehensive dynamics calculations were carried out at Ec = 40, 50, and 60 kcal mol–1, respectively, without rotational energies in the two reactants. As shown in Figure 5 and Table S1, for ground-state reactants (v = 0), the reactivities of the title reaction are very minimal, with the reactive integral cross-sections (ICSs) being only 0.002, 0.012, and 0.028 Å2, respectively, at Ec = 40, 50, and 60 kcal mol–1, which are much higher than the barrier height (25.0 kcal mol–1). As demonstrated below, the narrow cone of acceptance and the requirement of the concerted formation of the two bonds come in as the steric factor that can be attributed to the entropy in the Arrhenius equation. Statistically, the chance to access the TS is hindered, leading to minimal reactivities. Indeed, the entropic loss upon bond formation is prevailing in cycloaddition reactions.62

Figure 5.

Reactive ICSs of the title reaction as a function of Ec (in kcal mol–1) from different initial conditions.

When the energy is deposited in different reactant vibrational modes, its efficiency in promoting reactions may vary accordingly. This so-called mode specificity is thus defined by the differences in reactivity due to excitations in various reactant vibrational modes and has been extensively investigated in both gaseous reactions57,58,63−65 and reactions at gas–solid interfaces.66,67 For vibrationally excited reactants, N2O or C2H2, the ICS trends all increase along with increasing Ec, consistent with the activation nature of the title reaction. The excitations of different vibrations show different influences on the reactivities. For excitations in the N2O bending mode, vb(N2O) = 1, 5, the ICSs are increased by 50–800% within 40–60 kcal mol–1. This is consistent with the findings from previous direct post transition state dynamics68 by Houk and co-workers,22,23 and the predictions69 by the sudden vector projection (SVP) model, which attributes the enhancement of reactivity to the coupling of a reactant mode with the reaction coordinate at the TS.70 As shown in Figure S1, the reaction coordinate vector at the TS largely involves the N2O bending mode,23 whose normal mode vector is shown in Figure S2.

As seen in Figure 5, the mode specificity is rather complicated for the title reaction, while Houk and co-workers concluded that no other mode (except the N2O bending mode) should have much effect on its reactivity.22 Clearly, the excitations in the N2O asymmetric stretching mode (vas(N2O) = 1) and the C–C–H bending mode (vb(C2H2) = 1) of C2H2 essentially show no effect except for vas(N2O) = 1 at Ec = 50 kcal mol–1. According to the normal mode vectors in Figures S2 and S3, the vas(N2O) mode leads to one elongated and one shortened N–N and N–O distances, and the vb(C2H2) mode results in C2H2 trans-like configuration. This is in contrast to the concerted TS in Figure 2, which requires both N–N′ and N′–O bond distances to elongate simultaneously and both angles HCC′ and H′C′C of C2H2 to bend in the same direction.19

All other vibrational modes of the reactants show promotion effects on the title reaction, albeit different in magnitude. The excitation of the N2O symmetric stretching mode (vss(N2O) = 1) shows a significant boost effect, only slightly smaller than vb(N2O) = 1, as seen in Figure 5. This is because vss(N2O) = 1 leads to elongated N–N and N–O distances simultaneously, consistent with the geometric requirement at the TS. According to the SVP predictions,69 the reactivity can be promoted by excitations of the H–C–C–H wagging mode (vw(C2H2)) or the C–H symmetric stretching mode (vC–H,ss(C2H2)) of C2H2. They are in line with the current QCT results, which show that the ICSs are marginally increased by ca. 10%. As shown in Figure 5, similar effects can be found for the excitations of the C2H2 C–H asymmetric stretching mode (vC–H,as(C2H2) = 1). A remarkable increase of the ICS (40–110%) is found for vw(C2H2) = 5, slightly higher than vss(N2O) = 1, and smaller than vb(N2O) = 1. For the excitation of the C–C stretching mode (vCC–s(C2H2) = 1) of C2H2, its ICS is larger than vw(C2H2) = 1, vC–H,ss = 1, and vC–H,as(C2H2) = 1, and increased by 20–30% compared to v = 0. In addition, if the C2H2 or N2O rotations are sampled according to a Boltzmann distribution at 300/1000 K, the ICSs are not affected, 0.011/0.010 or 0.012/0.012 Å2, at Ec = 50 kcal mol–1 and v = 0. This is consistent with the deduction from direct dynamical results by Houk and co-workers; starting from the TS region, only 0–1% of the available energy was partitioned into the rotations of N2O or C2H2.23

Figure 6 presents the ICSs as a function of the total energy, which provides the energy efficacies between various vibrational excitations and the translational energies. One can see that in the total energy scale, the N2O bending mode excitations (vb(N2O) = 1, 5) are more effective than the translational energy in promoting the title reaction. For other vibrational excitations in the reactants, the translational energy is more effective in promoting the reaction.

Figure 6.

ICSs are plotted as a function of the total energy relative to the ZPE-corrected reactant asymptote on the PES.

The dynamics of the title reaction can be explored further in detail. Figure 7a presents the distribution of the time gap between the two forming bonds, C–N and C–O, in the reactive QCTs at 50 kcal mol–1 and v = 0. Following the criteria used by Xu et al.23 the first bond length is chosen to be 1.6 Å with the second one being 2.0 Å. Clearly, most (66%) of the time gaps fall in the range of 0–2 fs, and the remaining 34% are all within 2–30 fs. The average time gap is 4.7 fs. In the direct dynamics starting from the TS region, the calculated time gaps are all under 30 fs with a larger average 6–12 fs,23 compared to the current calculations. Both time gaps are under the C–N or C–O vibrational period of ca. 30 fs. Therefore, the concerted mechanism is highly dominant for the title reaction, and the stepwise mechanism with a diradical intermediate can be safely ruled out.

Figure 7.

Distribution of the time gap between the two forming bonds (a), impact parameter, b, (b), bond angle NCC′ at initial configurations and TS (c), and the bond angle OC′C at initial configurations and TS (d) in the reactive QCTs at Ec = 50 kcal mol–1 and v = 0.

During the reaction, the first forming bond can be either C–N or C–O bond. At Ec = 50 kcal mol–1 and v = 0, the corresponding ratio is 0.80:1 for CN:CO. As shown in Figures S4–S6 of the Supporting Information (SI), at other initial conditions, the ratios for CN:CO are all around 1:1 (0.80–1.03:1), consistent with the nearly equal amplitudes for both forming bonds (Figure S1 of SI) at the TS.23 The distribution of the reactive impact parameters, as shown in Figure 7b, possesses peaks within 0.4–0.6 Å with a maximum impact parameter of 1.2 Å. The distributions of the forming angles OC′C and NCC′ at initial configurations and TS in the reactive QCTs are displayed in Figure 7c,d, respectively. Clearly, for most reactive QCTs, the initial OC′C and NCC′ bond angles fall in a large range, 50–125°. At the TS, their distributions become much narrower, mainly within 95–105°, which are close to 101.7 and 106.4° of the ab initio TS. Figures S4–S6 show similar statistical analyses at other initial conditions. Besides, the bending angles NN′O of N2O are all nearly 180° at initial configurations and are significantly bent at TS in the reactions, as shown in Figure 8. In other words, the dipole bending mode is excited during the reaction process.

Figure 8.

Distributions of the bending angle NN′O at initial configurations and TS in reactive QCTs from different initial conditions: (a) Ec = 50 kcal mol–1, v = 0; (b) Ec = 50 kcal mol–1, vb(N2O) = 1; (c) Ec = 40 kcal mol–1, v = 0; and (d) Ec = 60 kcal mol–1, v = 0.

In addition to the time gap between the forming bonds, we measured the average asynchronicity as the difference between the two forming bonds at the transition state for Ec = 50 kcal mol–1 and v = 0. The average asynchronicity is 0.071 Å and they are all within 0.0–0.303 Å. These values are shorter than those determined in previous direct dynamical studies,71 confirming the concerted mechanism for the title reaction.

Regarding the microscopic mechanism of the title reaction, three reactive trajectories are plotted in Figure 4, with their trajectory movies provided in the SI. The trajectory in a solid black line corresponds to Ec = 50 kcal mol–1 and v = 0. First, two reactants approach each other, namely, to hit the repulsive wall. Therefore, a large amount of translational energy is required to propel the separate reactants sufficiently close to each other to reach the repulsive wall. Second, the trajectories squeeze out with the NN′O angle bent significantly to form the product through a very narrow region, as discussed above. The overall physical picture is consistent with previous direct dynamical calculations,22 with one such representative trajectory included in Figure 4 for direct visualization and comparison. The reactive trajectory took place mildly on the B3LYP/6–31G(d) surface without hitting the repulsive wall.22 This is because only 0.6 kcal mol–1 was deposited into the reaction coordinate in previous direct dynamics, and the slow velocity allows the reaction to follow the MEP. In addition, they concluded that only those N2O molecules with vibrationally excited bending modes can turn the corner and pass through the TS without hitting the wall.22 This is consistent with Figure 8a, namely, the bending angles NN′O of N2O must be bent at the TS region for reactions, although they are linear at the reactant asymptote. In Figure 4, the red and blue solid lines represent trajectories starting from vb(N2O) = 1 and 5, respectively. One can see that with more and more energy deposited into the N2O bending mode, the trajectories can turn to the corner earlier, even without hitting the repulsive wall. This confirms the important bending excitation of N2O in the reaction dynamics.

4. Summary and Conclusions

The first accurate full-dimensional PES of the N2O + C2H2 → oxadiazole reaction in the gas phase is developed by a machine learning approach. Comprehensive QCT calculations are performed to provide a quantitative and full understanding of the dynamics for this important reaction, which is a model for 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions. It has been found that all excitations in the reactant vibrations can enhance the reactivity, except for the asymmetric stretching mode of N2O and the C–C–H bending mode of C2H2, which essentially show no effect since they lead to configuration conflict with the concerted TS. The title reaction takes place via a concerted mechanism, supported by the short time gaps (the average is 4.7 fs) between the two forming bonds. Detailed statistical analysis on the geometries of the initial and TS in reactive trajectories has also been performed to confirm the concerted nature of the 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of the title reaction. This work undoubtedly helps to shed more light on the full understanding of the reaction dynamics in this important system. It should be noted that in this work, the reaction is studied in the gas phase. Most organic reactions take place in the liquid phase associated with some solvent, in which the reactivity and reaction dynamics can be significantly affected by the solvent–solute complexes, solvent caging, the coupling of the product motions to the solvent bath, thermalization of internally excited reaction products, hydrogen bond, etc.72 The mode specificity effect is thus expected to be minimal, especially when diffusion is the limiting factor. In this situation, the energy deposited into a specific mode is dissipated to the solution environment before it is transformed into the reaction coordinate.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 21973009 and 21573027), and the Chongqing Municipal Natural Science Foundation (Grant no. cstc2019jcyj-msxmX0087). J.L. acknowledges the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation for a Humboldt Fellowship for Experienced Researchers.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c03210.

QCT calculated ICS values (Table S1), the normal mode vectors of the reaction coordinate at the transition state (Figure S1), the normal mode vectors of vibrations in two reactants (Figures S2 and S3), and additional analysis resembling Figure 7 but at other initial conditions (Figures S4–S6) (PDF)

Representative trajectory movies (ZIP)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Huisgen R. Kinetics and Mechanism of 1,3-Dipolar Cycloadditions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1963, 2, 633–645. 10.1002/anie.196306331. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Houk K. N. Regioselectivity and reactivity in the 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions of diazonium betaines (diazoalkanes, azides, and nitrous oxide). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972, 94, 8953–8955. 10.1021/ja00780a077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Houk K. N.; Sims J.; Duke R. E.; Strozier R. W.; George J. K. Frontier molecular orbitals of 1,3 dipoles and dipolarophiles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973, 95, 7287–7301. 10.1021/ja00803a017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huisgen R.1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition Chemistry; Padwa A., Ed.; Wiley: New York, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Gothelf K. V.; Jørgensen K. A. Asymmetric 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition Reactions. Chem. Rev. 1998, 98, 863–910. 10.1021/cr970324e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padwa A.Synthetic Applications of 1,3-Dipolar Cycload-dition Chemistry toward Heterocycles and Natural Products; Pearson W. H., Ed.; Wiley: New York, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Krenske E. H.; Patel A.; Houk K. N. Does Nature Click? Theoretical Prediction of an Enzyme-Catalyzed Transannular 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition in the Biosynthesis of Lycojaponicumins A and B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 17638–17642. 10.1021/ja409928z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto T.; Maruoka K. Recent Advances of Catalytic Asymmetric 1,3-Dipolar Cycloadditions. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 5366–5412. 10.1021/cr5007182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb H. C.; Finn M. G.; Sharpless K. B. Click Chemistry: Diverse Chemical Function from a Few Good Reactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 2004–2021. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firestone R. A. Mechanism of 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions. J. Org. Chem. 1968, 33, 2285–2290. 10.1021/jo01270a023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Houk K. N.; Firestone R. A.; Munchausen L. L.; Mueller P. H.; Arison B. H.; Garcia L. A. Stereospecificity of 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions of p-nitrobenzonitrile oxide to cis- and trans-dideuterioethylene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985, 107, 7227–7228. 10.1021/ja00310a105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huisgen R.; Mloston G.; Langhals E. The first two-step 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions: interception of intermediate. J. Org. Chem. 1986, 51, 4085–4087. 10.1021/jo00371a039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lan Y.; Houk K. N. Mechanism and Stereoselectivity of the Stepwise 1,3-Dipolar Cycloadditions between a Thiocarbonyl Ylide and Electron-Deficient Dipolarophiles: A Computational Investigation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 17921–17927. 10.1021/ja108432b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S.; Yu P.; Houk K. N. Ambimodal Dipolar/Diels–Alder Cycloaddition Transition States Involving Proton Transfers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 18124–18131. 10.1021/jacs.8b11080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y.; Yang Z.; Houk K. N. Molecular dynamics of the intramolecular 1, 3-dipolar ene reaction of a nitrile oxide and an alkene: non-statistical behavior of a reaction involving a diradical intermediate. Mol. Phys. 2019, 117, 1360–1366. 10.1080/00268976.2018.1549338. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sustmann R. A simple model for substituent effects in cycloaddition reactions. I. 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions. Tetrahedron Lett. 1971, 12, 2717–2720. 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)96961-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Houk K. N.; Sims J.; Watts C. R.; Luskus L. J. Origin of reactivity, regioselectivity, and periselectivity in 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973, 95, 7301–7315. 10.1021/ja00803a018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ess D. H.; Houk K. N. Distortion/Interaction Energy Control of 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition Reactivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 10646–10647. 10.1021/ja0734086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ess D. H.; Houk K. N. Theory of 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions: Distortion/interaction and frontier molecular orbital models. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 10187–10198. 10.1021/ja800009z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen L. T.; Proft F. D.; Chandra A. K.; Uchimaru T.; Nguyen M. T.; Geerlings P. Nitrous oxide as a 1,3-dipole: a theoretical study of its cycloaddition mechanism. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 66, 6096–6103. 10.1021/jo015685f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen L. T.; Proft F. D.; Dao V. L.; Nguyen M. T.; Geerlings P. A theoretical approach to the regioselectivity in 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions of diazoalkanes, hydrazoic acid and nitrous oxide to acetylenes, phosphaalkynes and cyanides. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2003, 16, 615–625. 10.1002/poc.653. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L.; Doubleday C. E.; Houk K. N. Dynamics of 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reactions of diazonium betaines to acetylene and ethylene: Bending vibrations facilitate reaction. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 2746–2748. 10.1002/anie.200805906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L.; Doubleday C. E.; Houk K. N. Dynamics of 1,3-Dipolar Cycloadditions: Energy Partitioning of Reactants and Quantitation of Synchronicity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 3029–3037. 10.1021/ja909372f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes G. L.; Hase W. L. Transition State Analysis Bent out of shape. Nat. Chem. 2009, 1, 103–104. 10.1038/nchem.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engels B.; Christl M. What Controls the Reactivity of 1,3-Dipolar Cycloadditions?. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 7968–7970. 10.1002/anie.200902263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter B. K. Nonstatistical Dynamics in Thermal Reactions of Polyatomic Molecules. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2005, 56, 57–89. 10.1146/annurev.physchem.56.092503.141240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyola Y.; Singleton D. A. Dynamics and the Failure of Transition State Theory in Alkene Hydroboration. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 3130–3131. 10.1021/ja807666d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siebert M. R.; Zhang J.; Addepalli S. V.; Tantillo D. J.; Hase W. L. The Need for Enzymatic Steering in Abietic Acid Biosynthesis: Gas-Phase Chemical Dynamics Simulations of Carbocation Rearrangements on a Bifurcating Potential Energy Surface. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 8335–8343. 10.1021/ja201730y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black K.; Liu P.; Xu L.; Doubleday C.; Houk K. N. Dynamics, transition states, and timing of bond formation in Diels-Alder reactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012, 109, 12860–12865. 10.1073/pnas.1209316109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sexton T. M.; Freindorf M.; Kraka E.; Cremer D. A Reaction Valley Investigation of the Cycloaddition of 1,3-Dipoles with the Dipolarophiles Ethene and Acetylene: Solution of a Mechanistic Puzzle. J. Phys. Chem. A 2016, 120, 8400–8418. 10.1021/acs.jpca.6b07975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrascosa E.; Meyer J.; Zhang J.; Stei M.; Michaelsen T.; Hase W. L.; Yang L.; Wester R. Imaging dynamic fingerprints of competing E2 and SN2 reactions. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 25 10.1038/s41467-017-00065-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratihar S.; Ma X.; Homayoon Z.; Barnes G. L.; Hase W. L. Direct Chemical Dynamics Simulations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 3570–3590. 10.1021/jacs.6b12017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stei M.; Carrascosa E.; Dörfler A.; Meyer J.; Olasz B.; Czakó G.; Li A.; Guo H.; Wester R. Stretching vibration is a spectator in nucleophilic substitution. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaas9544 10.1126/sciadv.aas9544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z.; Houk K. N. The Dynamics of Chemical Reactions: Atomistic Visualizations of Organic Reactions, and Homage to van’t Hoff. Chem. – Eur. J. 2018, 24, 3916–3924. 10.1002/chem.201706032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer J.; Carrascosa E.; Michaelsen T.; Bastian B.; Li A.; Guo H.; Wester R. Unexpected Indirect Dynamics in Base-Induced Elimination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 20300–20308. 10.1021/jacs.9b10575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang B.; Li J.; Guo H. Potential energy surfaces from high fidelity fitting of ab initio points: the permutation invariant polynomial - neural network approach. Int. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2016, 35, 479–506. 10.1080/0144235X.2016.1200347. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Jiang B.; Guo H. Permutation invariant polynomial neural network approach to fitting potential energy surfaces. II. Four-atom systems. J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 139, 204103 10.1063/1.4832697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang B.; Guo H. Permutation invariant polynomial neural network approach to fitting potential energy surfaces. J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 139, 054112 10.1063/1.4817187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler T. B.; Knizia G.; Werner H.-J. A simple and efficient CCSD(T)-F12 approximation. J. Chem. Phys. 2007, 127, 221106 10.1063/1.2817618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knizia G.; Adler T. B.; Werner H.-J. Simplified CCSD(T)-F12 methods: Theory and benchmarks. J. Chem. Phys. 2009, 130, 054104 10.1063/1.3054300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czakó G.; Szabó I.; Telekes H. On the choice of the ab initio level of theory for potential energy surface developments. J. Phys. Chem. A 2014, 118, 646–654. 10.1021/jp411652u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner H.-J.; Knowles P. J.; Knizia G.; Manby F. R.; Schütz M. Molpro: a general-purpose quantum chemistry program package. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Comput. Mol. Sci. 2012, 2, 242–253. 10.1002/wcms.82. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Werner H.-J.; Knowles P. J.; Knizia G.; Manby F. R.; Schütz M.. MOLPRO, version 2015.1, a package of ab initio programs. http://www.molpro.net.

- Weichman M. L.; DeVine J. A.; Babin M. C.; Li J.; Guo L.; Ma J.; Guo H.; Neumark D. M. Feshbach resonances in the exit channel of the F + CH3OH -> HF + CH3O reaction observed using transition-state spectroscopy. Nat. Chem. 2017, 9, 950–955. 10.1038/nchem.2804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Xie C.; Guo H. Kinetics and dynamics of the C(P3) + H2O reaction on a full-dimensional accurate triplet state potential energy surface. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 23280–23288. 10.1039/C7CP04578F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai M.; Lu D.; Li J. Quasi-classical trajectory studies on the full-dimensional accurate potential energy surface for the OH + H2O = H2O + OH reaction. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 17718–17725. 10.1039/C7CP02656K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.; Bai M.; Song H.; Xie D.; Li J. Anomalous kinetics of the reaction between OH and HO2 on an accurate triplet state potential energy surface. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 12667–12675. 10.1039/C9CP01553A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu D.; Li J.; Guo H. Comprehensive Dynamical Investigations on the Cl + CH3OH → HCl + CH3O/CH2OH Reaction: Validation of Experiment and Dynamical Insights. CCS Chem. 2020, 2, 882–894. 10.31635/ccschem.020.202000195. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Z.; Bowman J. M. Permutationally invariant polynomial basis for molecular energy surface fitting via monomial symmetrization. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2010, 6, 26–34. 10.1021/ct9004917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman J. M.; Czakó G.; Fu B. High-dimensional ab initio potential energy surfaces for reaction dynamics calculations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 8094–8111. 10.1039/c0cp02722g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu C.; Yu Q.; Bowman J. M. Permutationally Invariant Potential Energy Surfaces. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2018, 69, 151–175. 10.1146/annurev-physchem-050317-021139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Guo H. Communication: An accurate full 15 dimensional permutationally invariant potential energy surface for the OH + CH4 -> H2O + CH3 reaction. J. Chem. Phys. 2015, 143, 221103 10.1063/1.4937570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X.; Hase W. L.; Pirraglia T. Vectorization of the general Monte Carlo classical trajectory program VENUS. J. Comput. Chem. 1991, 12, 1014–1024. 10.1002/jcc.540120814. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Truhlar D. G.; Muckerman J. T.. Reactive scattering cross sections III: quasiclassical and semiclassical methods. In Atom-Molecule Collision Theory; Bernstein R. B., Ed.; Plenum: New York, 1979; pp 505–566. [Google Scholar]

- Hase W. L.Classical Trajectory Simulations: Initial Conditions. In Encyclopedia of Computational Chemistry; Alinger N. L., Ed.; Wiley: New York, 1998; Vol. 1, pp 399–402. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasi J.; Mennucci B.; Cammi R. Quantum Mechanical Continuum Solvation Models. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 2999–3094. 10.1021/cr9904009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Jiang B.; Guo H. Reactant vibrational excitations are more effective than translational energy in promoting an early-barrier reaction F + H2O → HF + OH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 982–985. 10.1021/ja311159j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.; Song H.; Xie D.; Li J.; Guo H. Mode Specificity in the OH + HO2 -> H2O + O2 Reaction: Enhancement of Reactivity by Exciting a Spectator Mode. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 3331–3335. 10.1021/jacs.9b12467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; Li L.; Chen J.; Liu S.; Zhang D. H. Feshbach resonances in the F + H2O → HF + OH reaction. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 223 10.1038/s41467-019-14097-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K. L. K.; Quinn M. S.; Kolmann S. J.; Kable S. H.; Jordan M. J. T. Zero-point energy conservation in classical trajectory simulations: Application to H2CO. J. Chem. Phys. 2018, 148, 194113 10.1063/1.5023508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan Y.; Zou L.; Cao Y.; Houk K. N. Computational Methods To Calculate Accurate Activation and Reaction Energies of 1,3-Dipolar Cycloadditions of 24 1,3-Dipoles. J. Phys. Chem. A 2011, 115, 13906–13920. 10.1021/jp207563h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z.; Jamieson C. S.; Xue X.-S.; Garcia-Borràs M.; Benton T.; Dong X.; Liu F.; Houk K. N. Mechanisms and Dynamics of Reactions Involving Entropic Intermediates. Trends Chem. 2019, 1, 22–34. 10.1016/j.trechm.2019.01.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crim F. F. Vibrational state control of bimolecular reactions: Discovering and directing the chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 1999, 32, 877–884. 10.1021/ar950046a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crim F. F. Bond-selected chemistry: vibrational state control of photodissociation and bimolecular reaction. J. Phys. Chem. A. 1996, 100, 12725–12734. 10.1021/jp9604812. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K. Vibrational Control of Bimolecular Reactions with Methane by Mode, Bond, and Stereo Selectivity. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2016, 67, 91–111. 10.1146/annurev-physchem-040215-112522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juurlink L. B. F.; Killelea D. R.; Utz A. L. State-resolve probes of methane dissociation dynamics. Prog. Surf. Sci. 2009, 84, 69–134. 10.1016/j.progsurf.2009.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick H.; Beck R. D. Quantum State–Resolved Studies of Chemisorption Reactions. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2017, 68, 39–61. 10.1146/annurev-physchem-052516-044910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lourderaj U.; Park K.; Hase W. L. Classical trajectory simulations of post-transition state dynamics. Int. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2008, 27, 361–403. 10.1080/01442350802045446. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li A.; Guo H. Prediction of mode specificity in 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions using the Sudden Vector Projection model. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2015, 624, 102–106. 10.1016/j.cplett.2015.02.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H.; Jiang B. The sudden vector projection model: Mode specificity and bond selectivity made easy. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 3679–3685. 10.1021/ar500350f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L.; Doubleday C. E.; Houk K. N. Dynamics of Carbene Cycloadditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 17848–17854. 10.1021/ja207051b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr-Ewing A. J. Dynamics of Bimolecular Reactions in Solution. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2015, 66, 119–141. 10.1146/annurev-physchem-040214-121654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.