Abstract

BACKGROUND

In older persons, both high and low blood pressure (BP) levels are associated with symptoms of apathy. Population characteristics, such as burden of cerebral small‐vessel disease (CSVD), may underlie these apparently contradictory findings. We aimed to explore, in older persons, whether the burden of CSVD affects the association between BP and apathy.

DESIGN

Cross‐sectional study.

SETTING

Primary care setting, the Netherlands.

PARTICIPANTS

Community‐dwelling older persons (mean age = 80.7 years; SD = 4.1 years) with mild cognitive deficits and using antihypertensive treatment, participating in the baseline measurement of the magnetic resonance imaging substudy (n = 210) of the Discontinuation of Antihypertensive Treatment in the Elderly Study Leiden.

MEASUREMENTS

During home visits, BP was measured in a standardized way and apathy was assessed with the Apathy Scale (range = 0‐42). Stratified linear regression analyses were performed according to the burden of CSVD. A higher burden of CSVD was defined as 2 or more points on a compound CSVD score (range = 0‐3 points), defined as presence of white matter hyperintensities (greater than median), any lacunar infarct, and/or two or more microbleeds.

RESULTS

In the entire population, those with a lower systolic and those with a lower diastolic BP had more symptoms of apathy (β = −.35 [P = .01] and β = −.66 [P = .02], respectively). In older persons with a higher burden of CSVD (n = 50 [24%]), both lower systolic BP (β = −.64, P = .02) and lower diastolic BP (β = −1.6, P = .01) were associated with more symptoms of apathy, whereas no significant association was found between BP and symptoms of apathy in older persons with a lower burden of CSVD (n = 160).

CONCLUSIONS

Particularly in older persons with a higher burden of CSVD, lower BP was associated with more symptoms of apathy. Adequate BP levels for optimal psychological functioning may vary across older populations with a different burden of CSVD. J Am Geriatr Soc 68:1811‐1817, 2020.

Keywords: apathy, blood pressure, cerebral small‐vessel disease, depression

Apathy is defined as a lack of motivation and loss of interest in almost all daily activities and other persons, and is associated with a high caregiver burden.1 Apathy can occur as part of a depressive disorder2 and is particularly prevalent in patients with neurodegenerative diseases; however, apathy also frequently occurs in the older general population.3

Both cerebrovascular and cardiovascular diseases are risk factors for apathy.4, 5 In a longitudinal study among people aged 85 years and older, cardiovascular pathology at baseline was associated with more symptoms of apathy during follow‐up.6 Results from other longitudinal studies suggest a bidirectional relation, demonstrating an association between apathy at baseline and incident vascular disease.7 Although vascular disease in old age is a multifactorial result of accumulating damage, current blood pressure (BP) is a vascular factor that can still be treated. Cross‐sectional studies show that both higher8 and lower BP9 levels are related to more symptoms of apathy.

High BP, especially in middle age, can lead to cerebrovascular damage,10 which, in turn, can lead to apathy.4, 5 On the other hand, lower BP might lead to apathy via reduced cerebral blood flow,11 and older persons may vary in their ability to maintain cerebral blood flow in the presence of low BP.12 Also, in older persons, population characteristics that affect the regulation of BP may influence its association with neuropsychiatric symptoms.

In the Discontinuation of Antihypertensive Treatment in the Elderly (DANTE) Study Leiden, we previously found that the cross‐sectional association between lower BP and apathy was present only in those with worse functional ability; and we hypothesized that worse functional ability might be a proxy for a higher burden of cerebral small‐vessel disease (CSVD).9

In a subpopulation of participants of the DANTE Study Leiden that also underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the present study investigated whether the relationship between BP and apathy differed depending on the burden of CSVD. Our hypothesis was that, in older persons with a higher burden of CSVD, a lower rather than a higher BP would be associated with more symptoms of apathy.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

Baseline data from the DANTE Study Leiden were used for this study. The DANTE Study Leiden, a randomized clinical trial, aimed to investigate whether in older persons with mild cognitive deficits, neuropsychological functioning would improve after temporary discontinuation of antihypertensive treatment. Details on the design of the study are described elsewhere.13 In brief, from 2011 to 2013, 430 participants were included from general practices. Participants were included when they had mild cognitive deficits (defined as a Mini‐Mental State Examination [MMSE] score of 21‐27) and used antihypertensive medication. Participants were excluded when they had a history of stroke, major cardiovascular disease including heart failure, a clinical diagnosis of dementia, or a systolic BP of greater than 160 mm Hg. In a subset of the population (n = 220), at baseline, 3‐T MRI scanning of the brain was performed. Participants were excluded from this substudy if they had a contraindication for MRI or were unwilling to participate in the MRI substudy. Due to movement artifacts, one participant was excluded, and nine other patients had missing data (on the outcome measure or on MRI parameters), leaving 210 participants for the present analysis.

All patients gave informed consent to participate in the DANTE Study Leiden, which was approved by the Medical Ethics committee of the Leiden University Medical Center.

Measurement of BP

Using a digital sphygmomanometer (Omron M6 Comfort), BP was measured twice on the right arm in seated position; the average of the two measurements was used for the analyses. Pulse pressure (PP) was calculated as “systolic BP minus diastolic BP,” and mean arterial pressure (MAP) was calculated as “(2/3)*diastolic BP+(1/3)*systolic BP”.

Measurement of Symptoms of Apathy

Symptoms of apathy were measured with the Starkstein Apathy Scale.14 This instrument uses self‐report combined with clinical assessment to evaluate the presence of symptoms of apathy. It contains 14 items, each scored from 0 to 3, yielding a total score of 0 to 42, with higher scores indicating more symptoms of apathy. A cutoff of 14 or greater was used for clinically relevant apathy.14

Brain Imaging

Whole‐brain, 3 dimensional (3D) T1‐weighted (repetition time [TR]/echo time [TE] = 9.7/4.6 millisecond; flip angle [FA] = 8°; voxel size = 1.17 × 1.17 × 1.40 mm) images were acquired on a 3‐T MRI scanner (Philips Medical Systems). Details on imaging acquisition and image processing are described elsewhere.15 For the evaluation of features of CSVD, fluid‐attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) (TR/TE = 11,000/125 FA = 90°), T2*‐weighted (TR/TE = 45/31 milliseconds; FA = 13°), and T2‐weighted images (TR/TE = 4200/80 milliseconds; FA = 90°) were used. White matter hyperintensity (WMH) volume was quantified on FLAIR MRI in a semiautomated manner using the Oxford Centre for Functional MRI of the Brain Software Version 5.0.1. Library (http://www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl).15, 16 A trained single rater (J.F.D.), blinded for clinical data, visually scored cerebral microbleeds and lacunar infarcts. A second rater (J.G.) with more than 15 years of neuroradiological experience supervised the rating. Lacunar infarcts were assessed on FLAIR and T2‐ and 3DT1‐weighted images. Parenchymal defects (signal intensity identical to cerebrospinal fluid on all sequences) of 3 mm in diameter or more, surrounded by a zone of parenchyma with increased signal intensity on T2‐weighted and FLAIR images, were defined as lacunar infarcts. Cerebral microbleeds were defined as punctate hypointense foci (on T2 images), which increased in size on T2*‐weighted images (blooming effect).17 Symmetric hypointensities in the basal ganglia, likely to represent calcifications or nonhemorrhagic iron deposits, were disregarded.

Measurement of Burden of CSVD

As of yet, no universal scale for burden of CSVD is available. Based on previous literature and available MRI features, the burden of CSVD was defined as having two or more of the following features: high WMH volume (dichotomized based on the median volume), presence of any lacunar infarct, and/or the presence of two or more microbleeds.18, 19, 20 The role of cortical atrophy was assessed separately.

Other Measurements

Sociodemographic factors were assessed using a structured clinical interview. Information on medication and medical history was obtained from the general practitionerʼs records. Level of education was dichotomized at 6 years of education. Use of alcohol was dichotomized at 14 units per week. The presence of a chronic disease was defined as one or more of the following: diabetes mellitus, Parkinsonʼs disease, osteoarthritis, or a malignancy. Presence of cardiovascular disease was defined as one or more of the following: peripheral vascular disease, myocardial infarction longer than 3 years ago, or a coronary reperfusion intervention longer than 3 years ago (comprising percutaneous cardiac intervention and/or coronary artery bypass graft). Participants with a recent (<3 years ago) history of myocardial infarction or recent (<3 years ago) coronary reperfusion were excluded from the DANTE Study for safety reasons. Use of psychotropic medication was defined as using one or more of the following: antidepressants, antipsychotics, or benzodiazepines.

Depressive symptoms were measured with the Geriatric Depression Scale‐15 (GDS‐15).21 Since three items of the GDS‐15 have a strong overlap with symptoms of apathy,6, 22 only the remaining 12 items (GDS‐12) were used in this analysis (range = 0‐12, with higher scores indicating more symptoms). Functional ability was measured with the Groningen Activity Rating Scale23 (range = 18‐72, with higher scores indicating worse functional ability). Global cognitive function was measured with the MMSE24 (range = 0‐30, with higher scores indicating better cognitive function). A high amount of global cortical atrophy was defined as low gray matter volume,25 dichotomized on the median.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean with SD, median with interquartile range, or number with percentage, where appropriate. The association between BP and symptoms of apathy was tested using linear regression. β values with 95% confidence intervals and P values were calculated per 10‐mm Hg increase in BP as the independent variable and continuous Apathy Scale scores as the outcome variable. Based on previous knowledge of potentially important confounders, all analyses were adjusted for age, sex, level of education, use of alcohol, and the use of psychotropic medication.

Stratified analyses were performed to investigate whether the association between BP and symptoms of apathy differed between older persons with a higher/lower burden of CSVD. The groups were split based on the cutoff of two or more features of CSVD.19 To investigate the presence of statistical interaction, interaction terms (continuous BP parameter × burden of CSVD) were added to the linear regression models and P values were calculated. To investigate the role of global neocortical atrophy in the association between BP and apathy, we separately stratified for the amount of global cortical atrophy. Furthermore, global cortical atrophy was added to the CSVD compound score, and the stratified analysis for higher/lower burden of CSVD was repeated using a cutoff of two or more features. Because the role of microbleeds might differ based on their localization,17 separate analyses were performed for lobar/nonlobar microbleeds. Unless stated otherwise, P values for the continuous associations are presented. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

Table 1 presents details on the population of the DANTE Study Leiden MRI substudy; mean age was 80.7 (4.1) years, and 57.1% was female. Clinically relevant apathy was present in 22.9% of the population and, at baseline, all participants used antihypertensive treatment.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants of the DANTE MRI Substudy (n = 210)

| Characteristic | |

| Demographic | |

| Age, y | 80.7 (4.1) |

| Female | 120 (57.1) |

| >6 y of education | 150 (71.4) |

| Clinical | |

| Current smoking | 16 (7.6) |

| Use of alcohola | 21 (10.0) |

| History of CVDb | 17 (8.1) |

| Presence of chronic diseasec | 131 (61.9) |

| Use of psychotropic medicationd | 35 (16.7) |

| Use of β blockers | 78 (37.1) |

| Psychological and physical functioning | |

| Apathy Scale scoree | 10.7 (4.5) |

| Apathy Scale score ≥14 | 48 (22.9) |

| GDS‐12 scoref | 1 (0‐2) |

| MMSE scoreg | 26 (25‐27) |

| GARS scoreh | 22 (19‐28) |

| Blood pressure parameters, mm Hg | |

| Systolic blood pressure | 145.6 (21.1) |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 80.6 (10.7) |

| Pulse pressure | 65.0 (15.4) |

| Mean arterial pressure | 102.3 (13.2) |

| Features of cerebral small‐vessel disease | |

| WMH volume, mL | 20.9 (8.8‐56.2) |

| High WMH volumei | 103 (49.0) |

| Any lacunar infarct present | 57 (27.1) |

| ≥2 Microbleeds present | 28 (13.3) |

| Higher burdenj | 51 (23.8) |

Note: Data are presented as mean (SD), number (percentage), or median (interquartile range) when appropriate.

Abbreviations: CVD, cardiovascular disease; DANTE, Discontinuation of Antihypertensive Treatment in the Elderly; GARS, Groningen Activity Rating Scale; GDS‐12, Geriatric Depression Scale‐12; MMSE, Mini‐Mental State Examination; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; WMH, white matter hyperintensity.

Dichotomized at 14 or more units per week.

CVD indicates myocardial infarction, percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass grafting 3 or more years before, and peripheral arterial disease.

Chronic diseases comprise one or more of type 2 diabetes, Parkinsonʼs disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, osteoarthritis, and/or malignancy.

Psychotropic medication comprises one or more of antipsychotic and antidepressant medication and benzodiazepines.

Apathy Scale range is 0 to 42, with higher scores indicating more symptoms of apathy.

GDS‐12 range is 0 to 12, with higher scores indicating more symptoms of depression.

MMSE range is 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating better cognitive function.

GARS range is 18 to 72 points, with higher scores indicating worse functional status.

Dichotomized at the median.

Higher burden of cerebral small‐vessel disease is defined as presence of two or more of high WMH volume, any lacunar infarct, or two or more microbleeds.

Association Between BP and Apathy

In the entire population (n = 210), those with a lower systolic and those with a lower diastolic BP had more symptoms of apathy (β = −.35 [P = .01] and β = −.66 [P = .02], respectively). A lower MAP was also associated with more symptoms of apathy (β = −.59, P = .01) while PP was not significantly associated with symptoms of apathy (β = −.37, P = .07). None of the BP parameters was associated with symptoms of depression (data not shown).

Association Between BP and Apathy in Strata of CSVD

Table 2 shows the association between BP parameters and symptoms of apathy in the strata of higher/lower burden of CSVD. In those with a higher burden of CSVD, lower systolic BP (β = −.64, P = .02), lower diastolic BP (β = −1.6, P = .01), and lower mean arterial pressure (β = −1.1, P = .01) were associated with more symptoms of apathy. In contrast, there was no significant association between any of the BP parameters and symptoms of apathy in those with a lower burden of CSVD. The P value for interaction was .29 for systolic BP and .04 for diastolic BP. No BP parameters were associated with symptoms of depression in any of the groups (data not shown).

Table 2.

Mean Scores of Apathy Scale per BP Level, Stratified by Cerebral Small‐Vessel Disease (n = 210)

| Variable | Higher Burden of Cerebral Small‐Vessel Disease (n = 50) | Lower Burden of Cerebral Small‐Vessel Disease (n = 160) | P Value for Interaction | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SE) | β (95% CI) | P Value | Mean (SE) | β (95% CI) | P Value | |||

| Systolic BP | Systolic BP | |||||||

| Low (n = 14) | 12.8 (1.2) | Low (n = 58) | 11.0 (0.57) | |||||

| Middle (n = 15) | 11.3 (1.2) | Middle (n = 54) | 10.4 (0.58) | |||||

| High (n = 21) | 11.3 (0.96) | High (n = 48) | 9.7 (0.63) | |||||

| Per 10 mm Hg | −.64 (−1.12 to −.12) | .02 | Per 10 mm Hg | −.24 (−.57 to .09) | .15 | .29 | ||

| Diastolic BP | Diastolic BP | |||||||

| Low (n = 16) | 14.4 (1.0) | Low (n = 53) | 11.0 (0.60) | |||||

| Middle (n = 17) | 10.5 (1.0) | Middle (n = 53) | 10.8 (0.59) | |||||

| High (n = 17) | 10.3 (0.98) | High (n = 54) | 9.4 (0.59) | |||||

| Per 10 mm Hg | −1.6 (−2.8 to −.46) | .01 | Per 10 mm Hg | −.38 (−1.0 to .25) | .23 | .04 | ||

| Pulse pressure | Pulse pressure | |||||||

| Low (n = 14) | 12.8 (1.2) | Low (n = 56) | 10.9 (0.57) | |||||

| Middle (n = 14) | 11.3 (1.2) | Middle (n = 54) | 10.6 (0.59) | |||||

| High (n = 22) | 11.3 (0.95) | High (n = 50) | 9.6 (0.62) | |||||

| Per 10 mm Hg | −.71 (−1.5 to .08) | .08 | Per 10 mm Hg | −.27 (−.72 to .19) | .25 | .60 | ||

| Mean arterial pressure | Mean arterial pressure | |||||||

| Low (n = 16) | 13.7 (1.1) | Low (n = 54) | 11.1 (0.58) | |||||

| Middle (n = 15) | 10.5 (1.1) | Middle (n = 54) | 10.4 (0.58) | |||||

| High (n = 19) | 10.9 (0.97) | High (n = 52) | 9.6 (0.60) | |||||

| Per 10 mm Hg | −1.1 (−2.0 to −.32) | .01 | Per 10 mm Hg | −.38 (−.90 to .14) | .15 | .12 | ||

Note: Unstandardized β values with 95% CIs are calculated for each 10‐mm Hg increase in BP. P value for interaction between BP parameter and burden of cerebral small‐vessel disease. All analyses adjusted for age, sex, level of education, use of alcohol, and use of psychotropic medication. Higher cerebral small‐vessel disease burden is defined as presence of two or more of high white matter hyperintensity volume (dichotomized on the median), any lacunar infarct, and two or more microbleeds.

Tertiles of systolic BP: low, 136.5 mm Hg or lower; middle, 136.5 to 152 mm Hg; high, higher than 152 mm Hg. Tertiles of diastolic BP: low, 76.0 mm Hg or lower; middle, 76.5 to 84.5 mm Hg; high, 85 mm Hg or higher. Tertiles of pulse pressure: low, 58.0 mm Hg or lower; middle, 58.5 to 69.0 mm Hg; high, 69.5 mm Hg or higher. Tertiles of mean arterial pressure: low, 97.0 mm Hg or lower; middle, 97.2 to 107.0 mm Hg; high, 107.5 mm Hg or higher.

Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; CI, confidence interval.

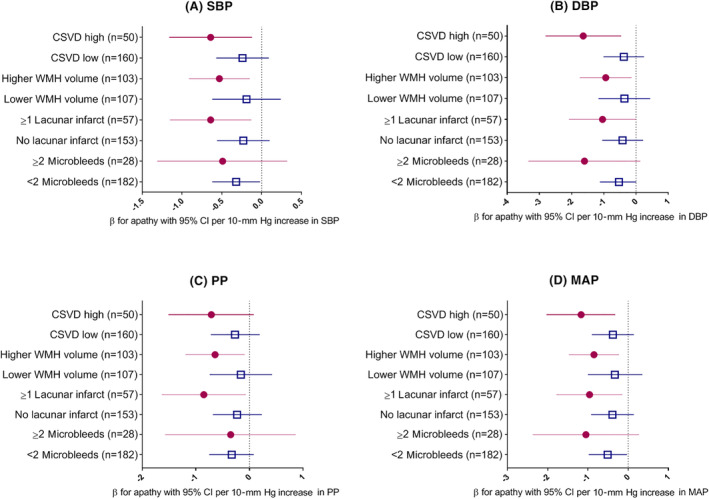

Figure 1 shows a consistent pattern of a stronger association of lower BP and symptoms of apathy in the presence of CSVD, when stratifying on the separate CSVD features.

Figure 1.

Association between blood pressure parameters and symptoms of apathy in strata of different features of cerebral small‐vessel disease (CSVD). All analyses adjusted for age, sex, level of education, use of alcohol, and use of psychotropic medication. Higher CSVD burden is defined as presence of two or more of: high white matter hyperintensity (WMH) volume (dichotomized on the median), any lacunar infarct, or two or more microbleeds. CI indicates confidence interval; DBP, diastolic blood pressure (Panel B); MAP, mean arterial pressure (Panel D); PP, pulse pressure (Panel C); SBP, systolic blood pressure (Panel A).

When stratified for global cortical atrophy, a lower systolic BP was associated with more symptoms of apathy in those with more global cortical atrophy (β = −.54, P = .02), whereas this association was absent in those with less global cortical atrophy (β = −.15, P = .38). Diastolic BP was not associated with symptoms of apathy in either stratum of global cortical atrophy (β = −.79, P = .09 in those with more global cortical atrophy, and β = −.23, P = .50 in those with less global cortical atrophy). When global cortical atrophy was added to the CSVD compound score, the results did not change. The results did not differ between older persons with lobar or nonlobar microbleeds. Additional adjustment for cognitive function (MMSE) or presence of chronic diseases did not change the results (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

This study among community‐dwelling older persons with mild cognitive deficits using antihypertensive medication found that, in those with a higher burden of CSVD, lower BP was associated with more symptoms of apathy. In contrast, in older persons with a lower burden of CSVD, BP was not associated with symptoms with apathy.

Although there is extensive evidence for the association between BP and cognitive function,12 few studies have investigated the association between BP and symptoms of apathy. The present findings extend our previous results showing that lower BP is cross‐sectionally associated with symptoms of apathy only in those with worse functional ability measured with the Groningen Activity Restriction Scale.9 In contrast to our findings, the Netherlands Study of Depression in Older Persons (NESDO) demonstrated that not a lower but a higher BP was cross‐sectionally associated with more symptoms of apathy in depressed older persons.8 A possible explanation for this discrepancy might be that the NESDO population was substantially younger than the DANTE population and that in NESDO, cerebrovascular damage was not taken into account as a potential effect modifier. However, the NESDO found no association between BP and depression severity,8 which was confirmed in the present study. This supports the notion that apathy and depression in old age have specific risk factors and might be viewed as distinct clinical entities. Our findings of heterogeneity in the association between BP and apathy are in line with studies showing that lower BP is specifically associated with worse cognitive function in older persons with worse functional ability,26 higher biological age,27 and a history of hypertension.28 The relation between apathy and cognitive impairment may be bidirectional,29 since severity of cognitive impairment has been related to more symptoms of apathy,3 while apathy has also been shown to predict worse cognitive function.29 In our study, adjusting our main analyses for cognitive function (MMSE) did not change the results, suggesting that cognitive function does not influence the association between apathy and BP in strata of CSVD.

Although no causal relations can be inferred from the present study due to the cross‐sectional design, we can speculate on potential mechanisms underlying the association between lower BP and apathy in those with a higher burden of CSVD. First, older persons with a higher burden of CSVD may be unable to maintain their cerebral perfusion in the presence of low systemic BP. This hypothesis is supported by the finding of impaired cerebral blood flow in persons with more CSVD.30 If impaired cerebral blood flow occurs in regions involved in the regulation of drive and motivation,31 this might explain why we found an association between lower BP and symptoms of apathy in those with more CSVD. This is further supported by the finding that lower BP was also associated with symptoms of apathy in those older persons with more global cortical brain atrophy, which has also been associated with worse cerebral perfusion.32, 33 However, the DANTE trial demonstrated that a 4‐month elevation of BP does not lead to a reduction in symptoms of apathy.13 An alternative explanation might be that cardiac dysfunction is related to both lower BP and apathy. Although older people with a diagnosis of heart failure were excluded from the DANTE Study Leiden because of safety issues, even subclinical heart failure is linked to a lower BP34 and might also be associated with more neuropsychiatric symptoms, including apathy.35

This study has several strengths. First, the DANTE population is a well‐defined population of community‐dwelling older persons. Apathy was measured with an instrument specifically designed to measure symptoms of apathy, and the interrater variability of this instrument in the DANTE Study Leiden was low.13 Also, being the main determinant in the DANTE Study, BP was measured carefully.

However, several limitations also need to be considered. First, the cross‐sectional design not only hampers causal inference, but also does not rule out the possibility of reversed causality. In this respect, a recent meta‐analysis of longitudinal studies demonstrated that apathy is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease.7 Second, although we adjusted for potential confounders, the possibility of residual confounding cannot be ruled out. Further, some of the subgroups consisted of relatively low numbers. However, our findings are consistent among multiple subgroups (eg, those with high total CSVD load, high WMH volume, and presence of lacunar infarcts) and across the different BP measures. Also, no measurements of (subclinical) heart failure were available in the DANTE Study Leiden, because no blood samples were taken and no echocardiograms/electronic cardiograms were performed. Last, the DANTE population was selected to participate in a clinical trial. This inevitably led to a selection of relatively well‐functioning older persons and, probably, those with the highest levels of apathy were less likely to participate; this limits the generalizability of our results.

Although these limitations preclude our findings from being directly translated into clinical practice, the study does generate new hypotheses for further research. For example, in studies that also measure cardiac function,36 the hypothesis can be tested that the relation between lower BP and apathy is at least partly explained by suboptimal cardiac function in older persons with CSVD. Furthermore, future trials investigating the effect of lowering of BP or, conversely, the effect of discontinuation of antihypertensive treatment, should take into account that the beneficial effects on apathy may vary between subpopulations of older persons.

In conclusion, in this study among older persons with mild cognitive deficits using antihypertensive medication, particularly in those with a higher burden of CSVD, lower BP was associated with more symptoms of apathy. Adequate BP levels for optimal psychological functioning may vary across older populations with a different burden of CSVD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all the Discontinuation of Antihypertensive Treatment in the Elderly Study Leiden coinvestigators.

Financial Disclosure

This study was supported by a grant from Program Priority Medicines for the Elderly, the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (project 113101003).

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors has a conflict of interest to declare.

Author Contributions

Bertens: acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data and drafting of the manuscript. Foster‐Dingley: acquisition and interpretation of data and revising the work critically for important intellectual content. Van der Grond: substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work, acquisition and interpretation of data, and revising the work critically for important intellectual content. Moonen: acquisition and interpretation of data and revising the work critically for important intellectual content. Van der Mast: substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work, interpretation of data, and revising the work critically for important intellectual content. Rius Ottenheim: substantial contributions to the design of the work, interpretation of data, and revising the work critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved of the final version to be published.

Sponsorʼs Role

The sponsor had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collections, analysis, and preparation of the article.

The results in this article were presented on April 3, 2019, at the annual meeting of the Dutch association of psychiatrists, the Nederlandse Vereniging voor Psychiatrie.

REFERENCES

- 1. Leroi I, Harbishettar V, Andrews M, McDonald K, Byrne EJ, Burns A. Carer burden in apathy and impulse control disorders in Parkinsonʼs disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;27:160‐166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Carlier A, van Exel E, Dols A, et al. The course of apathy in late‐life depression treated with electroconvulsive therapy: a prospective cohort study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;33:1253‐1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Onyike CU, Sheppard JM, Tschanz JT, et al. Epidemiology of apathy in older adults: the Cache County Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15:365‐375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. van Dalen JW, Moll van Charante EP, Nederkoorn PJ, van Gool WA, Richard E. Poststroke apathy. Stroke. 2013;44:851‐860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Grool AM, Geerlings MI, Sigurdsson S, et al. Structural MRI correlates of apathy symptoms in older persons without dementia: AGES‐Reykjavik Study. Neurology. 2014;82:1628‐1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Van der Mast RC, Vinkers DJ, Stek ML, et al. Vascular disease and apathy in old age: the Leiden 85‐Plus Study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23:266‐271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Eurelings LS, van Dalen JW, Ter Riet G, Moll van Charante EP, Richard E, van Gool WA. Apathy and depressive symptoms in older people and incident myocardial infarction, stroke, and mortality: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of individual participant data. Clin Epidemiol. 2018;10:363‐379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moonen JE, de Craen AJ, Comijs HC, Naarding P, de Ruijter W, van der Mast RC. In depressed older persons higher blood pressure is associated with symptoms of apathy: the NESDO study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27:1485‐1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moonen JE, Bertens AS, Foster‐Dingley JC, et al. Lower blood pressure and apathy coincide in older persons with poorer functional ability: the Discontinuation of Antihypertensive Treatment in Elderly People (DANTE) Study Leiden. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:112‐117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Law MR, Morris JK, Wald NJ. Use of blood pressure lowering drugs in the prevention of cardiovascular disease: meta‐analysis of 147 randomised trials in the context of expectations from prospective epidemiological studies. BMJ. 2009;338:b1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Craig AH, Cummings JL, Fairbanks L, et al. Cerebral blood flow correlates of apathy in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 1996;53:1116‐1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Muller M, Smulders YM, de Leeuw PW, Stehouwer CD. Treatment of hypertension in the oldest old: a critical role for frailty? Hypertension. 2013;63:433‐441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moonen JEF, Foster‐Dingley JC, De Ruijter W, et al. Effect of discontinuation of antihypertensive treatment in elderly people on cognitive functioning‐the DANTE Study Leiden: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1622‐1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Starkstein SE, Mayberg HS, Preziosi TJ, Andrezejewski P, Leiguarda R, Robinson RG. Reliability, validity, and clinical correlates of apathy in Parkinsonʼs disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1992;4:134‐139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Foster‐Dingley JC, Moonen JE, van den Berg‐Huijsmans AA, et al. Lower blood pressure and gray matter integrity loss in older persons. J Clin Hypertens. 2015;17:630‐637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Woolrich MW, Jbabdi S, Patenaude B, et al. Bayesian analysis of neuroimaging data in FSL. Neuroimage. 2009;45:S173‐S186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Greenberg SM, Vernooij MW, Cordonnier C, et al. Cerebral microbleeds: a guide to detection and interpretation. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:165‐174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wardlaw JM, Smith C, Dichgans M. Mechanisms of sporadic cerebral small vessel disease: insights from neuroimaging. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:483‐497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. van Sloten TT, Sigurdsson S, van Buchem MA, et al. Cerebral small vessel disease and association with higher incidence of depressive symptoms in a general elderly population: the AGES‐Reykjavik Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172:570‐578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Greenberg SM, Charidimou A. Diagnosis of cerebral amyloid angiopathy: evolution of the Boston criteria. Stroke. 2018;49:491‐497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982;17:37‐49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bertens AS, Moonen JE, de Waal MW, et al. Validity of the three apathy items of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS‐3A) in measuring apathy in older persons. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;32:421‐428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kempen GI, Miedema I, Ormel J, Molenaar W. The assessment of disability with the Groningen Activity Restriction Scale: conceptual framework and psychometric properties. Soc Sci Med. 1996;43:1601‐1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini‐mental state": a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189‐198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Foster‐Dingley JC, van der Grond J, Moonen JE, et al. Lower blood pressure is associated with smaller subcortical brain volumes in older persons. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28:1127‐1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Miller LM, Peralta CA, Fitzpatrick AL, et al. The role of functional status on the relationship between blood pressure and cognitive decline: the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Hypertens. 2019;37:1790‐1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ogliari G, Sabayan B, Mari D, et al. Age‐ and functional status‐dependent association between blood pressure and cognition: the Milan geriatrics 75+ cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:1741‐1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Muller M, Sigurdsson S, Kjartansson O, et al. Joint effect of mid‐ and late‐life blood pressure on the brain: the AGES‐Reykjavik study. Neurology. 2014;82:2187‐2195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lanctôt KL, Agüera‐Ortiz L, Brodaty H, et al. Apathy associated with neurocognitive disorders: recent progress and future directions. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13:84‐100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shi Y, Thrippleton MJ, Makin SD, et al. Cerebral blood flow in small vessel disease: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2016;36:1653‐1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. de la Torre JC. Cardiovascular risk factors promote brain hypoperfusion leading to cognitive decline and dementia. Cardiovasc Psychiatry Neurol. 2012;2012:367516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zonneveld HI, Loehrer EA, Hofman A, et al. The bidirectional association between reduced cerebral blood flow and brain atrophy in the general population. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2015;35:1882‐1887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Alosco ML, Gunstad J, Jerskey BA, et al. The adverse effects of reduced cerebral perfusion on cognition and brain structure in older adults with cardiovascular disease. Brain Behav. 2013;3:626‐636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. van Bemmel T, Holman ER, Gussekloo J, Blauw GJ, Bax JJ, Westendorp RG. Low blood pressure in the very old, a consequence of imminent heart failure: the Leiden 85‐plus Study. J Hum Hypertens. 2009;23:27‐32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Caplan LR. Cardiac encephalopathy and congestive heart failure: a hypothesis about the relationship. Neurology. 2006;66:99‐101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hooghiemstra AM, Bertens AS, Leeuwis AE, et al. The missing link in the pathophysiology of vascular cognitive impairment: design of the Heart‐Brain Study. Cerebrovasc Dis Extra. 2017;7:140‐152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]